#trials of apoll

Text

My favorite part about the first Trials of Apollo book was when they talked about the campers working out. I mean, YES!! I love working out, that was so fun to read about what the demigods do. You mean you drag the entire camp out of bed to go on a file mile run?? And do push ups and sit ups?? WOAH real camp life. Also I am biased because I am a distance runner so this was #relatable

#lester papadopoulos#trials of apoll#like seven year old Annabeth Chase on her first day of camp all stubborn trying to keep up with the big kids on the run#camp half blood is a running club#they probably ran the mile and were super competitive about it#I know that all the campers were not doing that#because there are a lot of kids who are stronger at other demigodly skills#but you know Clarisse and the Stoll brothers and Sherman Yang and Luke were probably battling it out#Luke Castellan out running Travis Stoll#and Connor Stoll made for his brother#Clarisse La Rue being super competitive towards the guys#but a bit nicer towards Annabeth since she is one of the only girls who is trying hard as H*ck to outrun the boys#runner lore hahah#not popular but I am having a good time#they run 5 miles in the morning#still not over it

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

I realized I never posted this here. Which is a tragedy I think.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

On my test: **There is a question about haikus**

Me, a Trials of Apollo fan: Oh yeah! Now my time to shine has come

#trials of apollo#pjo hoo toa#lester papadopoulos#toa apollo#The fact that if you didn't read Toa this post makes zero sense#My teacher explained this and my whole brain was: Apollo Apollo Apollo Apollo Apollo Apollo Apol-

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unfinished Friday

@wolfpants had the genius idea of sharing an excerpt from an abandoned WIP - I did a cheer read on the start of the fic and I can promise all the dron/dronarry fans that they are in for a treat when wolf does finish it!

this is a very fun idea for a post. i just dug through my docs and found SO MANY abandoned fics, why am i like this.

I have absolutely no recollection of this fic - the doc is called Livvy future fic and iirc it's one of three i started and abandoned as gifts for @sitp-recs😂and according to the one note i made, it's based on that tumblr post about Ron being a Seer. It ends mid-sentence 😅 I have to say I really want to read more of this so I might try to remember what I wanted to write and revisit it once my long fic is finished. The premise seems to be that the war is still raging and Draco defects and joins the Order (they are all adults). CW for Draco having been beaten up/injured. it's obvs unedited so apols for any clunkiness or typos

“But I don’t even like him,” Harry says, but Remus frowns at him, more disappointed than disapproving, and Malfoy looks as though he wants to say something rude back, which Harry would actually love. But then Malfoy tightens his lips, all the irritation carefully tweaked and smoothed from his face, a sort of social polite disinterest that reminds Harry of Sirius in Order meetings, and how had he never noticed how alike they look, even down to the matching gleam of candleflame on their long hair, bright and dark like empty mirrors of each other.

“I have options,” is all Malfoy says in reply, but Ron blows a raspberry at that until Percy elbows him, and Hermione says rudely, “Like what? Going on the run and dying at wandpoint within about two days? Because that plan’s been working out well for you so far.”

“Can we please just take a vote?” Kingsley is impatient, and rightly so; he hasn’t slept properly in weeks, probably, like the rest of them. Harry wants to vote no, he really does, but Malfoy starts quietly gathering his cloak around him, face stupid with pride, eyes blacked up and spongey like damaged fruit. It’s spite, mostly, that has Harry scribbling a yes, though in the end it wouldn’t have mattered anyway, because the vote to let Malfoy stay passes at twelve in favour, seven against, which is more decisive than even Remus was expecting, judging by the look on his face.

“He can take the back attic,” Sirius says decisively, still the casual master of the house he hates so much, and Kreacher appears with a resentful crack to clear the plates as the others gather themselves to get home before the Floo curfew.

Harry follows Sirius closely up the stairs, almost treading on the back of his big boots, Malfoy moving almost soundlessly behind them.

“Voila,” Sirius says, and with a sweep of one arm ushers Malfoy into a real letdown of a room, practically Muggle this high up, no heat to speak of, not even a good view, nothing but the dreadful garden and the blank face of the back wall of the house behind.

“This is—” Malfoy starts.

Harry waits, tense, though Sirius just looks amused and almost gleeful, but Malfoy doesn’t finish. He sets his small rucksack down beside the bed, and walks over to the window, throws it up like a challenge, so the room buzzes with the distant sounds of a London night.

“Thank you,” Malfoy says, and Sirius nods and pads out. Malfoy watches him go, his face abruptly whitening up, like salt or puddled wax.

“You don’t get to be ungrateful about it, you know,” Harry tells him, stung by the look on Malfoy’s face.

“I don’t like you either,” is all Malfoy says, quietly but so viciously that Harry knows he means every word, then Sirius sticks his head back around the door and, seeing Harry’s face, bundles Harry out the door and back down two flights of stairs, where there’s at least a proper fire in the drawing room and the windows don’t rattle in the wind.

“Congratulations on your trial being overturned, Mr Malfoy,” Minerva says when she sees him, and Malfoy smiles tiredly and tries to push back his damp hair with his gauntleted hand.

***

Ron’s visions are getting worse, and Harry spends his twenty-sixth birthday preparing to brew Dreamless Sleep with Malfoy, because the new Ministry has reclassified Sopophorous Beans as a restricted product and all the apothecaries are running low. They can Apparate to Peterlee but that’s as close to the wards as they can get without their magical signatures being picked up, and it’s still a two-hour broom flight from there. Malfoy doesn’t even grumble even though it’s the hottest summer in years and by the time they arrive, their travelling cloaks are stuck to their backs with sweat.

“It was a sham,” Harry tells her. “They had no evidence, just a whole load of trumped up charges.”

They both look at him with raised eyebrows, and Harry makes a grateful retreat to the greenhouses where Professor Sprout and Neville have sackfuls of illicit produce waiting for him, which they spend a hot and grumpy hour rigging into a complicated harness to attach between the two brooms for the journey home. When Harry finally escapes, he goes down to the Lake for a swim. There’s no one around, all the students gone home, and Harry floats, feeling boneless, scoured clean by sun, belly up.

He doesn’t mean to eavesdrop on Malfoy and Minerva, but he supposes they must not hear him coming. He’s still barefoot when he reaches the castle, clutching his grubby travelling clothes in his arms, the cooler air of the castle a delicious chill where it chases the water droplets on his skin.

“I need to look into it further,” Malfoy is saying, though Minerva speaks over him crisply, and they could almost be back at school.

“It’s absolutely no indication of any guaranteed outcome, Draco.”

Malfoy’s voice is getting higher and tighter, wound up to cracking. “It’s got to mean something though, Min. Don’t try to tell me you’re—”

“Temporal magic is notoriously unstable,” Minerva says, and then Harry drops one of his boots with a thump, and Malfoy and Minerva come around the corner to see what’s happening.

Malfoy goes red when he sees Harry, a crawling

A CRAWLING WHAT, PAST TACKY???

i'm tagging anyone who has docs filled with treasures languishing, plus @fluxweeed @thehoneybeet @maesterchill @m0srael @oknowkiss @saxamophone @shealwaysreads @sweet-s0rr0w

#jeez i have really been on my “the war is still raging” tip for quite a while now haven't i#i also have political drama/forced bond/magical world revealed to muggles/dudley has a magic baby fic#harry can't die but then draco does and he tries to get him back#unspeakable draco#and many more#i must have 40k or so of abandoned wips#i had not realised#wolf i'm so glad you started this#it's been fun looking through old docs

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

trial of Publius Nigidius Figulus

date: c. 56 BCE?

charge: sacrilegium

defendant: P. Nigidius Figulus pr. 58

[Cic.] Sal. 14; see also Cic. Vat. 14; Tim. 1; Apul. Apol. 42

The case is dubious, since the source is unreliable.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did it, for those who want to read it, I posted the first chapter for Meg and Apollo travel the world, otherwise, you can ignore this post.

Enjoy :)

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

I haven't seen you around much since your punishment. It seems to have mellowed you out a bit which I appreciate.

I won't lie, you disturb me. Wanting to use the suffering of others as a plot device. Pain is something that should be indulged in and shared, not stolen. You strike me as all bark and no bite. Watch yourself. You are an easy target.

I can't wait to see where you wind up.

eas y tar get? s u re, okay.

i do apol g ies for my act ons at th e begi nning of all of th is. tryng to get bettr wit h help.

th e trials are so soon aft r all.

maybe you should be the one to watch your back.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

early bday smoochies for the golden boi!!!

#jason grace#nico di angelo#jasico#pjato#pjo#hoo#heroes of olympus#percy jackson and the olympians#trials of apoll#toa#poofy doodles

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

JASON GRACE DESERVED THE WORLD I MISS HIM SO MUCH I HOPE HE’S WELL

#jason grace#thalia grace#rick riordan#percy jackson#heroes of olympus#trials of apoll#apol#lester papadopoulos#meg mccaffrey#grover underwood#annabeth chase#Piper McLean#hazel levesque#frank zhang#leo valdez

7 notes

·

View notes

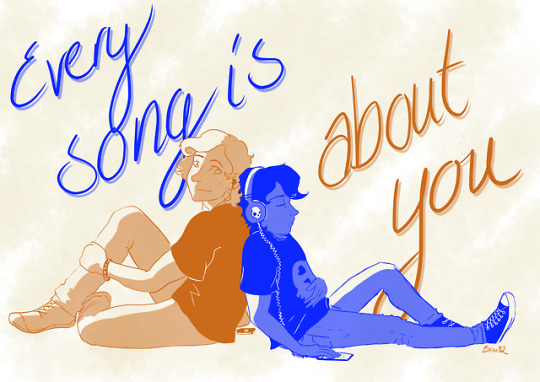

Photo

I am still on House of Hades, so Will hasn’t really made a lot of appearances yet, but I already have a VIP ticket for this ship. I had (by coincidence) reached the chapter where Cupid forces Nico to come out and tell Jason that he had a crush on Percy.

This is very important to me. I want to be a published writer, and I am currently writing on a story. The plan is that the first draft will be done during February. I have decided that unless otherwise stated, all my characters are somewhere on the bisexual gradient, as I personally believe that we should consider sexuality a gradient. Some are at one end, some are at the other end, but most of us are somewhere along the gradient. I hope that will be my contribution to the LGBTQ community. Both the story I am working on now, and the one I am planning on next, will also discuss mental health problems.

I am analyzing and ripping apart Fall Out Boy songs these days. When thinking of this line from “Fourth of July”, I had this thought that Nico must have a pair of Skullcandy headphones. At least, if he even has a music device, which I sadly doubt. But Will, as a son of Apollo, must have introduced him to modern music.

But the best Nico-ship is of course to ship him with quality sleep and a healthy diet...

Here’s other Riordan characters and (mostly Fall Out Boy) lyrics: Masterpost

#solangelo#nico di angelo#will solace#percy jackson#heroes of olympus#trials of apoll#bfire92#fall out boy#fourth of july#skullcandy#music#lgbtq#pride

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Head Canon-

Nico and Will constantly fight over which Ice cream flavor is superior, Nico is all for Vanilla and and Will loves chocolate. And they absolutely hate each others flavors.

#nico di angelo#willsolace#sloanglo#tower of nero#percy jackson#heros of olympus#nicoandwill#nico and will#percy jackson ships#trials of apollo#son of hades#son of apoll#jasongrace#bianca di angelo

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

"No necesito a otra persona para sanar mi corazón. No necesito un socio... al menos, no hasta y a menos que esté lista en mis propios términos. No necesito que me emparejen a la fuerza con nadie ni llevar la etiqueta de otra persona. Por primera vez en mucho tiempo, siento que me han quitado un peso de encima. Así que gracias."

—Reyna, Las Pruebas de Apolo 4. La Tumba del Tirano

#citas#frases#quotes#books#rick riordan#the trials of apollo#trials of apollo#reyna avila ramirez arellano#reyna arellano#las pruebas de apolo#apollo#apoll#la tumba del tirano#the tyrants tomb

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reclaimed

Fandom: Trials of Apollo

Rating: Gen

Genre: Family

Characters: Poseidon, Zeus, Apollo

It appeared that Zeus’ favourite punishment had finally delivered a well-deserved sting in the tail.

Day twenty-eight of TOApril organised by @ferodactyl, “Was It Worth It?”. It took me a while to figure out what to do with this one, but then Poseidon started sniggering in the back of my head and I guess we’ve added yet another godly pov to this challenge now. TON spoilers.

There’s now a discord server for all my fics, including this one! If you wanna chat with me or with other readers about stuff I write (or just be social in general), hop on over and say hi!

Zeus was not happy. It took Poseidon a moment to notice, mostly because Zeus was almost never happy, these days, so it was hardly a new occurrence, but once he did, it was impossible to miss. In his hand – always in his hand, nowadays; Poseidon hadn’t seen him without it since its theft a few years ago – the Master Bolt sparked erratically, a betrayal of the turmoil behind stormy eyes.

Poseidon, for his part, was vindictively delighted. It was obvious that something had gone wrong with Apollo’s punishment, in the eyes of Zeus. Maybe it was the fact that the final moments of the fight with Python had been out of their sight, leaving them all with the what if of the serpent’s fate, maybe it was something else entirely.

Most likely, it was a combination of factors – even Poseidon wasn’t best pleased at not seeing the end of the confrontation with Python, if only because of a morbid curiosity to see how Apollo handled it while so thoroughly mortal (Poseidon was certainly sympathetic to the cause; he, alone, of the rest of the Twelve, knew what it was like to have power stripped away, a body mortal and vulnerable to the whims of others. Not even Dionysus could claim as such; once he’d ascended, he’d never fallen again).

However, most curious was the way Apollo had regained his divinity. Artemis had squirrelled her twin away immediately, but even the brief moment when Apollo’s unconscious form had materialised in the middle of the throne room, looking older than he’d chosen to appear for years, it had been perfectly clear that his divinity was back. They hadn’t been able to see the moment of the return, a fact he knew several of the gods were muttering about, but it had happened, and that was interesting.

Poseidon remembered mortality. He remembered the gruelling time as a servant, punished for agreeing with Hera, Apollo and the slippery Athena that Zeus needed to listen to them, and most importantly, he remembered the moment it ended.

The sea does not like to be restrained, and his power had surged through him like a whirlpool, filling every fibre of his essence with the song of the oceans, tempestuous and roiling. The sensation was incomparable to anything else; how could he possibly describe it to anyone else, the feeling of the dry, empty well flooding as it rightfully should have done, restoring what should never have been empty to start with? It was invigorating; any prior weariness of mortality had been washed away, reviving him to a state of alertness he had almost forgotten he’d once had.

Apollo, too, had been the same, he recalled. The two of them had never compared notes, never discussed their mutual punishment and the eventual ending of it, but he remembered the way Olympus sang with music again, the golden glow that permeated his nephew’s essence as he, too, regained his godhood at Zeus’ behest.

It was the opposite of exhausting, the opposite of traumatising, and yet this time, Apollo was unconscious. Of all three mortal stints, this was the shortest, albeit the most dangerous (and Poseidon wondered at that, wondered what Zeus’ aim had really been; the mourning suit couldn’t have been for his demigod son. Jason’s death had been months earlier and while Hera had taken to wearing a veil immediately, Zeus had barely acknowledged it). The battle with Python might have drained Apollo’s mortal form of life, but the return of his power ought to have replenished anything lost, and far more besides.

And therein lay the other fact that didn’t quite add up: if none of them had been able to see the climax of the fight, Zeus grumpily included, then how had Zeus known when to restore his power fully? Poseidon had assumed the trickles of divinity they’d been able to observe during the confrontation with Nero had been his brother’s doing, but that didn’t marry up with the mourning suit, and it certainly didn’t give an answer for how he’d determined the timing of Apollo’s powers. The returning of a god’s powers was not subtle, either. It was not something Zeus could do with a mere thought, or a wave of his hand. It took effort from his brother to withdraw it from where he’d stored it – Poseidon remembered watching that when it had been his own, remembered the tsunami bursting free of the restraints that should never have held it back.

Zeus had never done that during the Python fight. Poseidon had watched him, as much as his nephew, and he’d never made a single move. Nor, too, had he announced returning Apollo’s powers, and his brother was far too much a showman to resort to subtlety, lest someone get it into their head that there was any other explanation for the punishment to be over.

Add in the fact that Zeus was clearly unhappy, and the pieces of the puzzle were flowing together in a way that had Poseidon fingering his trident in amusement. The others had not realised it – how could they have, when they’d never been on the other side and didn’t know what to look for – and for the moment he decided it was knowledge best kept to himself, perhaps privately discussed with Apollo at a later date, once his nephew was fully settled back in the Olympian routine again.

Still, he couldn’t help the smirk that danced across his face as Zeus declared them all dismissed, instructing them to reconvene once Apollo ‘deigned to rejoin them’, because it was suddenly so painfully obvious that Zeus’ delivered punishment had backfired on him spectacularly. His proud younger brother would never admit it, of course; that would mean a confession that his power over them was not so absolute as he claimed, and Zeus would never do that.

It wasn’t that Poseidon wasn’t a little jealous of Apollo, because he certainly was. Their situations had been different, but that his nephew had managed to do this time what he had not… But Apollo was no threat. Not to him, and only to Zeus because Zeus insisted on making him one.

“Was it worth it?” he couldn’t help but gloat on his way out, quiet enough that only Zeus could hear him. “Turning him mortal again?”

He dissolved into seafoam before the lightning could strike, reappearing in Atlantis and exploding in bubbles of laughter, to Triton’s apparent concern. He waved his son away without offering explanation, watching the eyeroll before twin tails propelled his heir to another part of the palace.

Because the answer was no, it hadn’t been worth it. In fact, it had been a huge mistake; Zeus’ favourite extreme punishment had ended in the worst way possible, to his brother’s thoughts. Apollo had clawed his own divinity back from his father without permission, finally pushed far enough that he’d become the threat Zeus had always feared. Apollo, stripped bare and reduced to something Zeus thought could never challenge him, had overpowered the king of the gods.

There would be consequences to that; Zeus would not take it laying down, and certainly not if word got out about how the punishment had truly come to an end. Apollo’s position had both been firmly cemented and made extremely precarious, and what latent prophetic powers Poseidon maintained from before his nephew took over the domain suggested change would be afoot.

In that moment, however, all Poseidon could think was that it served his brother right.

#trials of apollo#trials of apollo fanfiction#riordanverse#riordanverse fanfic#pjo poseidon#pjo zeus#pjo apollo#tsari writes fanfiction#toapril

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

trial of Gnaeus Papirius Carbo

date: 112 BCE?

charge: perduellio? [high treason] (defeat fighting Cimbri)

defendant: Cn. Papirius Carbo cos. 113

prosecutor: M. Antonius cos. 99, cens. 97

Cic. Fam. 9.21.3; Apul. Apol. 66

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, a little less than a month year ago (this is all my fault, I take sole responsibility for this loooong delay), I got roped into reading The Trials Of Apollo by @flightfoot’s amazing meta. I loved it more than I could have ever anticipated, and I’ve been gushing about it non stop to her on discord. We had a lot of fun reviewing the series and taking it apart to overanalyze bit by bit, marveling at the way it keeps growing layers and dimensions the longer one looks at it. Finally, we took out a google doc. The following is result n.3 of our combined excited ramblings, and… well it sort of turned into a full on dissertation. Whoops.

“You must make your own choice.”

Reconstructing Apollo’s Journey within Riordan’s Narrative

Much too self aware to be egotistical

Not the kind of feelings that gods have

You have heard of imposter syndrome?

As if you could have immortality or meaning, but not both

The sun’s indifference

Art thou sure that is thy wish? (read on ao3)

Finally, Apollo stops lying to our faces every other paragraph about what he really thinks and feels. He stops wasting time and energy pretending that he doesn't mean, that he doesn't want to do the right thing. That he doesn’t care about everything and everybody. He's done being ashamed of it. He won’t hide from who he is anymore.

It should be a liberating choice, but it doesn’t feel like it. Far from it. Now that he doesn’t let himself cower behind his lies any longer, now that he refuses to flinch away from reality and take refuge in the imaginary stage play he’d gotten so comfortable writing and acting out inside his own head, he can see with agonizingly perfect clarity how much he'd screwed up. How much time he's wasted. How much blood is on his hands.

There was no climbing cage going to the second level – just bare metal rungs against the side of the girder, as if the builders had decided, Welp, if you made it this far, you must be crazy, so no more safety features! Now that the metal-ribbed chute was gone, I realized it had given me some psychological comfort. At least I could pretend I was inside a safe structure, not free-climbing a giant tower like a lunatic. (TTT 247)

The guilt he felt before was nothing compared to the guilt he feels now without the buffer of pretense. As hollow as it was, he misses the comfort that his safety cage had given him. But the only way to make the climb was to leave it behind.

Oh, Jason Grace … I promised you I would remember what it was to be human. But why did human shame have to hurt so much? Why wasn’t there an off button? (TTT 134)

Apollo did many bad things in his long life. Some of them, many of them, he did because he was backed into a corner. Because he had no choice, or because he’d been made to believe that he didn’t, and accepted that that was the truth. But he can’t, he won’t let himself acknowledge it, not even now that he’s finally allowing himself to put the right name to what he’s experienced at his father’s hands.

He is not like Meg. He is not a child. He is responsible for his own choices. He should have known better. He should have tried harder. He will have to keep trying, somehow, whatever it takes, no matter how hopeless it seems, once he’s back with the rest of the gods, back within the fold of the little abusive cult that he calls family, high above the top of the Empire State Building, because unlike Meg, he’s never getting free.

He keeps insisting that human shame is different, because he needs to believe that when the time comes he won’t jump at the chance to turn it off, shut it down, bury it in the sand and never look back, just like he’d done with the godly one, which is exactly the same.

Have you ever had an experience so painful or embarrassing you literally forgot it happened? Your mind dissociates, scuttles away from the incident yelling Nope, nope, nope, and refuses to acknowledge the memory ever again? (TTT 43)

He’d done it to survive. But that’s no excuse. Deep down, Apollo has always believed this. He has to find a way to do better anyway. He has no guarantee that he will. He doesn’t have anything but his desperate, stubborn resolve to keep his promise to Jason, to himself, to everybody.

I will be Apollo. I will remember.

When had I last felt ‘whole’? I wanted to believe it was back when I was a god, but that wasn’t true. I hadn’t been completely myself for centuries. Maybe millennia. (TTT 316)

The problem with getting used to lying all the time is not that you end up forgetting what the truth is. You don’t. Not unless you want to. And Apollo could never truly bring himself to want to. No, the problem with getting used to lying all the time is that, after a while, the lies start to feel more real than the truth itself.

Apollo knows who he is, but he has not allowed himself to be that person in a really, really long time. So long, that he isn’t quite sure how to do it anymore.

But he can’t afford to wait to figure it out until after the crisis has passed. The hourglass is running out of sand.

Lupa stood before the altar. Mist shrouded her fur as if she were off-gassing quicksilver.

It is your time, she told me.

[...]

‘My time,’ I said. ‘For what, exactly?’

She nipped the air in annoyance. To be Apollo. The pack needs you.

I wanted to scream, I’ve been trying to be Apollo! It’s not that easy! (TTT 95)

“Continue to act strong,” Lupa tells him. Apollo understands. Her advice makes sense to him. “Half the trick to being a god,” he had told Meg their first morning together at Camp Half Blood, “is knowing how to bluff.”

He can do that. He’s been doing it this whole time. So maybe he just needs to switch his old act for a new one. The vapid, selfish, privileged brat for the reformed ex villain seeking redemption. The latter feels more right. It definitely feels closer to the truth, and to the end goal, than his previous routine.

The problem is, ultimately, it’s still an act.

‘Did you just use the term skedaddleth?’

I TRY TO SPEAK PLAINLY TO THEE, TO GRANT THEE A BOON, AND STILL THOU COMPLAINEST.

‘I appreciate a good boon as much as the next person. But, if I’m going to contribute to this quest and not just cower in the corner, I need to know how –’ my voice cracked – ‘how to be me again.’

The vibration of the arrow felt almost like a cat purring, trying to soothe an ill human. ART THOU SURE THAT IS THY WISH?

‘What do you mean?’ I demanded. ‘That’s the whole point! Everything I’m doing is so –’ (TTT 138)

Apollo has spent so long trying to be someone other than himself, there’s almost no one left who truly knows him anymore. The characters he played are all that most of the people around him have ever known.

And he doesn’t get to correct their assumptions. He doesn’t get to make his case to the arrow. How would that even go? You see, I’m not actually an asshole, I just pretended to be! I swear I didn’t mean it!

Nobody wants to hear that. To anyone who’s ever had the misfortune of having to put up with it, the two looked exactly the same.

And, contrary to popular belief that he himself had carefully planted and cultivated, Apollo can read a room.

I began to speak, the Latin ritual verses pouring out of me. I chanted from instinct, barely aware of the words’ meanings. I had already praised Jason with my song. That had been deeply personal. This was just a necessary formality.

In some corner of my mind, I wondered if this was how mortals felt when they used to pray to me. Perhaps their devotions had been nothing but muscle memory, reciting by rote while their minds drifted elsewhere, uninterested in my glory. I found the idea strangely … understandable. Now that I was a mortal, why should I not practise non-violent resistance against the gods, too? (TTT 91-92)

The Romans still pray to the gods. They still prayed to Apollo too. And yet, none of them really has any idea who Apollo is. Most of them never cared to know either. Why would they? Gods aren’t people. Gods aren’t friends. They are beautiful golden idols to appease. They might grant someone a wish, sometimes, if that wish is something they already wanted to make happen anyway. They don’t actually care about anything but themselves.

And Apollo was just like the rest of them.

It doesn’t matter that his indifference was always fake. From a distance, it looked real. From a distance, it looked the same as that of any of the other gods. And Apollo was oh so very careful, at all times, to keep his distance.

He still is.

He calls Zeus his abuser, but he only does it in the privacy of his own head, and in the pages of these books that won’t be read by any of the people who could actually give him sympathy and support.

Gods aren’t supposed to need sympathy. They aren’t supposed to need support. They aren’t supposed to be helpless.

Apollo feels safe in telling us, because we can’t do anything, we can’t offer anything to him other than a listening ear.

But even to us Apollo doesn’t explain, because the truth is Apollo doesn’t WANT to explain. It’s incredibly hard for him, still, to admit that he was never as in control of his own life and choices as he liked to think and pretend he was.

This, too, is who Apollo is. He believes that he had no right to be a victim.

So, even as he admits it, he won’t let himself acknowledge how that shaped every single one of his choices, of his thoughts, of his beliefs even.

He will take all the responsibility, because he can’t admit that, even at his most powerful, he was always powerless.

He can’t let go of the illusion of control, not so much for the sake of his own pride and dignity – if there’s one thing that’s been made entirely clear by Apollo’s narration at this point, it’s that he really doesn’t care anymore about making himself look good – but because he’s still desperately grasping for some proof, any proof, that he truly can do better, and that he truly will be able, this time, to make a difference, that he will be able to avoid repeating his mistakes, even though the circumstances and the people that taught and helped and pushed him to make them will always be there.

To admit that he was always powerless would mean admitting that at the end of these trials, even if he succeeds, especially if he succeeds, he will be powerless again. And that is unacceptable.

So no, It doesn’t feel good to be Apollo. It doesn’t feel liberating. It still feels like shit.

‘I can’t believe I used to think –’

‘That I was your father? But we look so much alike.’

He laughed. ‘Just take care of yourself, okay? I don’t think I could handle a world with no Apollo in it.’

His tone was so genuine it made me tear up. I’d started to accept that no one wanted Apollo back – not my fellow gods, not the demigods, perhaps not even my talking arrow. Yet Frank Zhang still believed in me.

Before I could do anything embarrassing – like hug him, or cry, or start believing I was a worthwhile individual – I spotted my three quest partners trudging towards us. (TTT 142)

Apollo knows who he is. As much as he still pretends otherwise, he has no illusions about it. He’s exactly the sort of person that he strived so hard to become. He is someone nobody would miss, except maybe Frank Zhang, who, like Apollo’s children, like all of the people Apollo is ever so grateful, ever so surprised to be able to call friends, is too kind for his own good.

He’s the worst of the gods, and a rather terrible human being too. Too vain and insecure to stop caring what people think of him. Too much of a selfish coward to make peace with the finality of death, and with it, the possibility that he won’t get another chance to remedy his failings. Entitled enough that he still, despite everything, thinks he has a right to hold into his hands the power to make a difference, and arrogant enough that he still, despite everything, wants to believe that he can.

Are you sure, the arrow asked him. But what other choice does he have?

No one else who has the power to do so will lift a finger to stop the emperors. No one else who has the power to do it will wrestle the future out of Python’s jaws.

So it has to be Apollo, just like the first time.

He will have to take responsibility for all of it, because someone has to, and no one else will.

And when he succeeds, IF he succeeds, he’ll have to go back to his comfortable golden prison in the sky, and try to remember what it was like to be a person rather than a god, hold onto those memories even after everybody else who’s been witness to his struggle will be long gone.

I dreamed of homes. Had I ever really had one?

Delos was my birthplace, but only because my pregnant mother, Leto, took refuge there to escape Hera’s wrath. The island served as an emergency sanctuary for my sister and me, too, but it never felt like home any more than the back seat of a taxi would feel like home to a child born on the way to a hospital.

Mount Olympus? I had a palace there. I visited for the holidays. But it always felt more like the place my dad lived with my stepmom.

The Palace of the Sun? That was Helios’s old crib. I’d just redecorated.

Even Delphi, home of my greatest Oracle, had originally been the lair of Python. Try as you might, you can never get the smell of old snakeskin out of a volcanic cavern.

Sad to say, in my four-thousand-plus years, the times I’d felt most at home had all happened during the past few months: at Camp Half-Blood, sharing a cabin with my demigod children; at the Waystation with Emma, Jo, Georgina, Leo and Calypso, all of us sitting around the kitchen table chopping vegetables from the garden for dinner; at the Cistern in Palm Springs with Meg, Grover, Mellie, Coach Hedge and a prickly assortment of cactus dryads; and now at Camp Jupiter, where the anxious, grief-stricken Romans, despite their many problems, despite the fact that I brought misery and disaster wherever I went, had welcomed me with respect, a room above their coffee shop and some lovely bed linen to wear.

These places were homes. Whether I deserved to be part of them or not – that was a different question. (TTT 171-172)

Everyone deserves a second chance. Everyone deserves to feel loved. Everyone deserves to be recognized. Everyone deserves a home. Everyone, Apollo keeps telling us, keeps confirming with his actions, with his choices, because he really does believe it. Everyone. Except him.

In his golden prison above the clouds, Apollo has been taught that gods shouldn’t want, that gods shouldn’t need any of these things. Gods aren’t people. Gods are not like the rest of us. When Apollo said this, back at the beginning of this journey, it just felt like hilariously misplaced haughtiness. It’s much easier now, 4 books later, with the curtain of lies finally out of the way, to recognize in the familiar rhetoric the common refrain of abuse victims. Good people deserve good things. Normal people deserve good things. Even bad people deserve a second chance. But not me. Never me.

Apollo has a lot to feel guilty about. But he doesn’t stop at that. He feels guilty for things that he had no control over and objectively bears no blame for. He feels guilty for things that quite frankly aren’t a big enough deal to warrant any assignment of blame. He feels guilty for things that weren’t bad at all and he should maybe, actually, rather take pride in.

In his golden prison above the clouds, he’s been taught to feel responsible for everything.

And he does. He spends the first half of book 4 beating himself up for all that is wrong with the world, his guilt threatening to consume him both metaphorically and quite literally, taking the form of the poison inexorably spreading through his body that he, unlike every other mortal human in the city and at camp, in defiance of all of Pranjal’s medical experience, inexplicably can’t manage to fight off.

Gods are powered by belief, and a god’s belief can quite literally shape reality. For a god, intent is action. For a god, wanting to do something might as well be the same as having already done it. Apollo doesn’t want to die. And he doesn’t. But now that he finally looks at himself again without the filter of pretense before his eyes, he finds it incredibly hard to still believe that he shouldn’t.

“YOUR FAULT,” Zeus thunders in his memories, the only thing Apollo remembers of the six months that preceded his fall. “YOUR PUNISHMENT.” That’s why Apollo is here. To do penance for the sins of them all. And as much as he tried to protest it, it does make a perverse sort of sense to him. Deep down, there’s a part of him, still, that believes he deserves it.

It’s not your fault, Apollo tells Meg. The two of them are very much alike. He understands her. He has no trouble figuring out that she blames herself for his condition.

He has a lot more trouble, still, 4 books in, to imagine that she might actually care for him enough to be afraid of losing him, even as the obvious truth is staring him in the face.

It’s because of all the time we spent together, he rationalizes, equating himself to the little peach demon who’s been the only other semi constant presence in Meg’s life as of late in seeming complete earnestness, by all measures sounding like he’s genuinely unable to grasp the absurdity of such a comparison.

Like many people who have grown up in abusive households, Apollo is starved for love, and like many of his fellow abuse victims, he sees love as a transactional affair. He doesn’t really believe he can have anyone’s love for free. He keeps being caught off guard, feeling ashamed every time someone shows him even just a modicum of compassion. He allows himself to pursue physical intimacy, but friendship? Companionship? Understanding? No, those are off limits. There’s no way he can pay the price of them.

He was shocked that Will and Kayla and Austin would be so kind and welcoming to him when he was a powerless, puny mortal. He struggled to accept their acceptance, their eagerness to help him. Why would they waste their love on him when he clearly had nothing more to give them in exchange for it? “A father”, he’d thought, “should give more to his children than he takes”.

He thinks about Artemis now, about the way he used to call her his baby sister, “to annoy her,” he says. His next words betray the real reason, though. Despite how much she clearly finds me annoying too, he says, I suppose that, unlike Artemis, Meg really needs me.

That’s what the whole “baby sister” thing has always been about: giving himself the illusion that there’s something he can do for Artemis that will justify her wanting to hold onto him, because without it, without her actually needing him for anything, he can’t bring himself to believe that she’d care.

And Apollo knows. When he chooses to, he never has trouble distinguishing the lies from the truth. He’s always known, deep down, that his twin has never needed him. “Artemis understood me,” he tells us. “Well, okay, she tolerated me,” he amends immediately after. “Most of the time,” he adds. “All right, some of the time.”

But “with Meg,” he says, “I felt as if it were actually true.”

He can believe Meg’s love, unlike that of Artemis, unlike that of his children, of everybody else, because he has the means to buy it. He finds comfort in this thought, even as he realizes that he’s already behind on mortgage payments.

“What a horribly insufficient friend I had been,” he thinks.

As he offers her the hug he’d wanted and never dared to give her before, under the mistaken assumption that she wouldn’t accept it – let alone welcome it, he takes all the blame, once again, as he’s well accustomed to.

It’s not your fault, he tells Meg any chance he gets. It’s not your fault. You deserve better. But he is not like her.

In his heart of hearts, Apollo truly does believe he is the lone exception.

Of course it’s all his fault. He is a god. That’s the very definition of being responsible for everything.

“I [will] tough it out until the moment I [keel] over,” he vows, pretending to be shocked at the thought as if that’s not exactly what we’ve seen him do for 4 books straight, as if the only difference isn’t that now he’s admitting to what he’s doing, committed to the new narrative of self improvement he’s chosen for himself just as resolutely as he was to the old fiction of selfish, uncaring entitlement that he’s finally discarded.

Apollo loved to whine, so long as there was no chance of being taken seriously.

But as soon as he realizes that he is, in fact, truly at risk of being believed, he immediately shutters himself off.

He doesn’t deserve his friends’ concern. He refuses to add to their worries. There’s nothing they can do to help him anyway. Apollo needs a miracle. They all do. And they are only mortals. At most, they can buy him some time. The rest is up to him, as it rightfully should be.

What do mortals say – Suck it up? I sucked it way, way up. (TTT 60)

After 3 books of sifting through Apollo's lies to get at the increasingly hard to miss rising mountain of facts, we understand that Apollo is, in fact, observant, keenly perceptive, and incredibly self aware.

Now that he's stopped lying to us every other paragraph about what he really thinks and feels, we are finally able to see where his real blind spots lie.

“I was tired of others keeping me safe,” he says. “The whole point of consulting the arrow had been to figure out how I could get back to the business of keeping others safe.”

As is clearly apparent, by now, from the way he chooses to tell and frame this story, Apollo doesn’t really consider anything he does as a mortal as worth acknowledgement, let alone praise. He keeps noting how others help him, while paying no mind to all the times he has helped them in turn. He feels that everything he did up until this point counts for nothing.

The entirety of his long term plan hinges on regaining his godhood, and his current short term plan is to jump through near impossible hoops in order to perform a ritual that will hopefully allow him to call for divine intervention in time. Not just any divine intervention either: the real deal, “actual grade-AA-quality” help, minor gods need not apply.

His first reaction to discovering himself powerless, way back in book 1, was to swear those stupid oaths on the Styx because the mere idea of being anything less that superhumanly perfect at the things he’s supposed to be famous for horrified him. It didn’t matter to him at all that he was still good at them. More than good in fact! He was still a prodigy by human standards!

But human standards are not the standards Apollo has ever been measuring himself with.

I need to get back to the business of keeping others safe, he says. What he means is, he wants to get back to a place where he’ll have no use for other people’s help. He wants to get back to the place where he’ll have enough power to do everything himself.

In his mind, there can be no give and take. There shouldn’t. Because he is not a person like any other.

A father, he’d said, should give more to his children than he takes. And what are mortal creatures to divine immortal beings, if not frail, clueless children?

This is, to Apollo, what it truly means to be a god. This is his responsibility. To be the solution to all problems. To be endlessly strong, and never in need. To be the father who always gives and never takes.

For him, being able to do anything less than everything isn’t enough.

He is in awe of his mortal friends’ bravery, of their resilience, of their hope. He is grateful for their kindness and generosity. He appreciates everything they’ve done for him. But he feels guilty every time he’s forced to take anything from them. He feels like he shouldn’t. Like it’s wrong of him to even just accept what’s freely offered.

He admires their strength. He finds it genuinely commendable. But he has higher standards for himself. He is a god. They, in the end, are only mortals. There’s only so much they can do.

Now that he’s stopped role playing the asshole, Apollo would never say the latter bit out loud. And he doesn’t. But there’s a part of him, a small, secret one, deep down, that is actually thinking it.

“If Will and Nico were here,” he says at one point, “they would just be two more people for me to worry about.”

Apollo believes that he should be strong enough to carry all of this on his own shoulders. That’s how it’s supposed to be. That’s what gods, the ones that actually matter at least, are for. Apollo should be the only one worrying.

The truth is, even with his newly instated policy of emotional honesty, there’s still so much he simply doesn’t tell anyone. Not even us.

Better not add to our worries. Better for us not to know.

And yet, Apollo’s too intelligent to be entirely stupid, and too decent to be entirely unfair.

He does not make the mistake of keeping crucial intel to himself. He shares all of the knowledge he gains, even when he expects it will do more damage than good. He stands by his beliefs, and he believes in people’s right to make their own choice, even if that choice ends up being the choice to run away.

“I can’t fall into line like a good soldier,” Lavinia tells him. “Me locking shields and marching off to die with everybody else? That’s not going to help anybody.”

Apollo understands. He’s never liked mindless obedience and pointless sacrifices either.

But despite how well he understands her, despite how much of himself he sees in her, even – or perhaps precisely because he sees himself in her, despite having witnessed her unwillingness to back down from a fight several times, he’s quick to assume the worst of her, and of her faun and dryad friends too. Of course they must be running away. They’re mortals. Powerless. What else could they possibly do?

“How simple it would be to destroy their fragile confidence,” he thinks, looking at the people making lighthearted chatter in the mess hall. “Fragile” is the word he uses, also, to describe Meg’s state of mind, an assessment so shockingly patronizing, standing in such stark contrast to all the times he’s praised her strength and bravery all throughout the past 3 books, and in this book too, that it almost feels out of character for him.

But it isn’t. This, too, is who Apollo is.

Asclepius, god of medicine, used to chide me about helping those with disabilities. You can help them if they ask. But wait for them to ask. It’s their choice to make, not yours.

For a god, this was a hard thing to understand, much like deadlines, but I left Lu to her meal. (TON 226)

This is a story about power and privilege. Apollo was born a one percenter not just by mortal standards, but by godly ones too. He was always eager to help, and able to give on a scale that dwarfed every possible attempt to give back on the part of anyone on the receiving end of his blessings.

He doesn’t want to think less of them because of it. He refuses to. He took his human son’s advice to heart, so much so that he remembers and recites it reverently millennia after it was first given to him.

Apollo really does believe in mortals’ right to self determination. He keeps telling them to make their own choices. He is determined to respect them. But deep down, there’s a part of him that wonders just how much of a difference their choices truly can make, when they are backed by so little power. There's a part of him, too, that wonders how informed those choices can be, when they are based on so little life experience, so little knowledge compared to his.

He's so quick to dismiss people's good opinion of him. Their willingness to put their trust in him. Even their love.

They don’t know better, a part of him thinks, still, even now. They will turn away the moment I disappoint them.

Turns out, there’s some real condescension under all the fake one. Much subtler, much harder to spot, and entirely benevolent, but condescension all the same.

Are you sure, the arrow said, unknowingly asking precisely the right question for the wrong reasons, that what you really want is to go back to being the same person you were before?

21 notes

·

View notes