#us queers have a LONG history with leathers and things like Doc Martens

Text

Today on "Odd Things That Gave Me Happy Gender Feels"-

Conditioning my new Docs for the first time.

Getting my new shoes for work (they are SO nice and fit like a glove)

New necklace that looks like barbed wire

Noticing that yeah- my voice HAS gotten a little bit deeper in the two months I've been on T.

#personal#queer#trans#transmasc#genderqueer#genderfucked#the boots especially I think gave me feels cuz like#i joke about how owning leather is the Queer Point of No Return#but like#us queers have a LONG history with leathers and things like Doc Martens#and there's just something about having chosen that brand#specifically because I have associated it with queerness since I was younger#and now being an open and out queer adult who FINALLY has their own pair#idk it just#made me feel really nice#also i should probably know how to take care of leather shoes since I have some nice new fancy dress shoes#shoutout to tomboy toes because these fit like a DREAM#need some breaking in but WOW

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been thinking a lot about how gay people say I love you, and I mean that literally.

I’ve known people for a few hours most, and said “I love you” and meant it - new years parties, university tutorials, anime conventions - the gay woman who was a friend of a friend giving my friends and I a lift home in the winter cold was an angel, and I meant it when I said “Thank you, I love you, get home safe.” The person from high school that I lost touch with then reconnected with telling me about their girlfriend was like filling my lungs again for the first time in years, and I meant it when I said “Please, next time bring your girlfriend, I love her already.” My grandmother that told me about how she used to use bandages to bind back in the 80s and how her first husband was gay was the first person in my family to make me feel normal, and I meant it when I said “I love you, I hope you’re happy now.” The friend I found through our shared love of Scooby Doo and then proceeded to run the gamut of labels and pronouns with is my home 8000 miles away, and I still mean it when I say “I love you, we should call more.” And I mean it when I scream “I love you” to every person I meet in fleeting hugs and hand-holds at the pride parade, even when I’m overstimulated and exhausted by the time I get home, glitter-sick and shy.

I think we say I love you for every reason you could say I love you, but more than anything, it’s the simple fact of seeing someone who is your family that makes you want to grab them by the shoulders and tell them that you love them. Gay people have such a long history of being family and community when no one else would take us, and every time I see someone being openly queer, I love them. I love your smeared lip-gloss and your septum piercing and your dyed hair and your crooked teeth and your leather harness and your pronoun pins and your Doc Martens and your chipped nail polish and your loud laugh and your T-beard and your Adam's apple and the way you twirl a little clumsily in your skirt. It’s 100 meanings of the word - what you said was funny, I love you - you’re a dickhead, but I love you - I’m glad you figured things out, I love you - you don’t need to say anything, I love you - thank God there’s another trans person here, I love you - you make me feel whole, I love you - we hurt each other, but I still love you.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

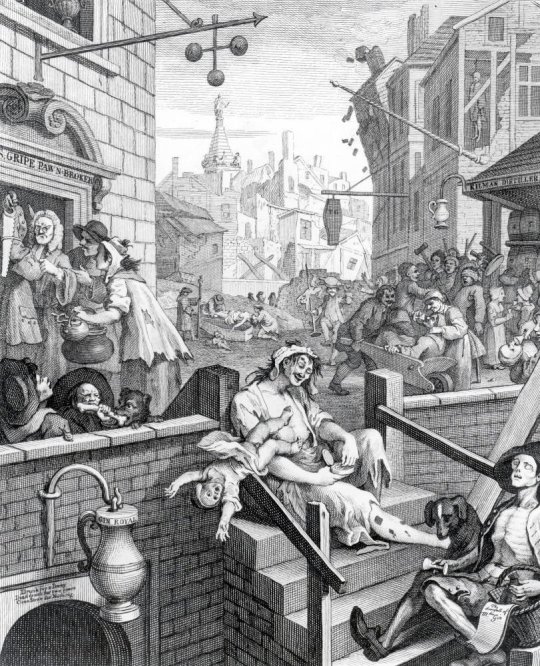

Punk’d History, Vol. II: Catamites and Junkies, Rockers and Runts

As a word and a set of behavioral possibilities, “punk” has always circulated with anxious, negative intensity. Since its entrance into the vernaculars of English, the word punk has acquired a wide semantic range, seemingly always dancing on the borders of excitement and abjection.

Contemporary mass culture seems to understand the term differently. There’s an established referent, with a sort of regalia and a standardized affect: mohawks, spiked leather jackets and Doc Martens; angry, snotty and at least a little bit fucked up (and likely a lot more than a little). There’s an oft-noted irony in that: a subculture so focused on anarchy (albeit a superficial, sloganeering form of it) and on rebelliousness (more often in symbolic, gestural forms, than in organized political action) acquires a compulsory style, a uniform. In the mass cultural imaginary, “punk” most often conjures the image of a UK82 band, and “a punk” most often looks and behaves like Wattie Buchan. (A future entry of Punk’d History will consider why that should be.)

As a sort of counter-measure, we might examine the term’s symbolic history. The list of meanings and examples below is woefully inadequate and partial—any number of meanings and especially significant iterations (in figures, songs and aesthetic manifestations) are missing.* That’s the point. In spite of our habits of language, punk doesn’t want to be contained. Punk is a kick in the teeth, and its myriad traces can be encountered in the innumerable fragments.

Punk, a prostitute: this oldest traceable usage enters the language in the late 16th century. Shakespeare provides an excellent example in Measure for Measure (1623): in Act V, Lucio observes of Mariana, “She may be a punk; for many of them are neither maid, widow, nor wife.” This suggests that in Elizabethan England there were only four thinkable conditions for women not in nunneries—but that’s a different history of containment. In any case, it’s interesting to note that English’s rendition of “punk” starts here, with sex work and its fraught relation to appetites. It gives word to a form of labor, and to desires that evade and exceed the policing of institutions, like marriage and the church.

So what do we do with this?

youtube

It’s Dee Dee’s song, and he had first-hand experience hustling in Manhattan’s Loop. But Dee Dee doesn’t issue musical memoir: he gives us a character, a vet back from Nam, damaged and pissed. His come-on is a confrontational hyper-masculine dare. The desire moving through the song is complex: the need to fuck, which is economically driven (“trying to turn a trick”); the need to fuck, which is denied (“You’re the one they never pick”); the violent attempts to recuperate the queerness (“no more of your fairy stories,” “I’m no sissy”). The song de-mystifies any romantic notions of sex work, even as it dramatizes familiar anti-institutional tropes (the pyscho vet, the fugitive, the oppressive forces of Law and Capital). All of that begs the question of where we locate our more current notion of “punk” in relation to this deepest of historical senses for its proper referent.

Punk, a catamite: a related sexualized meaning, which is both more precise and more complex. It enters the language in the late 17th century, traceable to an anonymous broadside, “Womens Complaint to Venus” (1698): “The Beaus too… / At night make a punk / Of him that’s first drunk.” The poem was satiric, registering public worries about the increased visibility of queer sexual identity and practices in London. While the poem evinces unfortunate attitudes toward queerness, the stanza usefully points to the exclusively male sense of this usage, and its implication that the punk is made a bottom unintentionally or by force. A more recent, more specific extension of this usage is present in Alexander Berkman’s Prison Memoir of an Anarchist (1912): “A punk’s a boy that’ll…give himself to a man.” Berkman was friend and lover of Emma Goldman, and in 1892 he attempted the assassination of Henry Clay Frick; Berkman was caught and jailed in Pennsylvania Western Penitentiary, where he observed the prison’s extensive sexual economy, of willing partnerships, temporary relations of mutual benefit and rape. Punks in this sense occupy a range of positions, from consensual bottoms to victims of (frequently repeated) sexual assault. (This association with carceral power may have something to do with the usage of “punk” in modern American black culture, but that’s an even more complicated history.)

The political meaning of being “at the bottom” frequently get confused with being a bottom, and contemporary punk has participated in the confusion:

youtube

Frank Discussion, front man for the Feederz and long-time practitioner of detournment, has repeatedly explained that the song’s discourse on submission isn’t meant to operate at the expense of queer sexualities—but the song’s easy appropriation of conventional ideas about marginal sexual practices seems way too easy. Of course, the Feederz aren’t the only punk and punk-related artists to present uncomfortably normative ideas about the politics of sexual submission, or about queer sexuality (I don’t really want to sully this essay by mentioning the Meatmen, but it seems necessary…). None of is meant to reduce punk’s attitudes toward queer sexualities as monolithically intolerant—that would be a stupid distortion. But the difficult, overlapping symbolic terrains of power, position and sex remain provoking.

Punk, a petty thug, a despicable person of low or no account: this usage seems a lot less problematic, and enters the language in the late 19th century. Hemingway used it, in “The Mother of a Queen” (1933): the story’s Anglo agent accuses his profligate matador client, “You give fifty pesos to that punk and then offer me twenty when you owe me six hundred. I wouldn’t take a nickel from you.” Thomas Pynchon used it, too, in V. (1963): Benny Profane observes of the Playboys, a gang from Spanish Harlem, “There was nothing so special about the gang, punks are punks.” It’s interesting that both of those High Literary references invoke the specter of another social hierarchy: class difference. The idea of the person of “low or no account” can be accounted for through accounting—through the metric of money, or the lack of it: who can turn up his nose at twenty pesos, and who needs them to survive? Whose lives are relegated to tenement apartments and grinding struggle?

So:

youtube

My aim is not to recruit the Tubes to punk—rather I want to foreground the lyrics’ engagement with “punk” as a sort of code for social class. In this usage, punk becomes a mobile quality, enacted by the lyric protagonist in his rich-kid malaise, which issues in a drug habit and the proposition that “the ghetto” and Pacific Heights are equally empty of value. In 1975, ahead of the international news media’s sudden and scandalous discovery of the Sex Pistols, the Tubes grafted “punk”—as a low-rent dalliance with cheap thrills and nasty influences—onto a glammed-up performance of exhausted excess: “Have to score when I get that rich white punk itch…” But in the Tubes’ rendition of punk, there’s always the parents’ chateau to retreat to.

The suggestion of suspicions about glam rock’s adequacy as a discourse of resistance is insightful, so far as it goes. Glam in California was burdened by any number of problematic relations to postmodern industrial obsessions with surface value. Spandex, big hair, gratuitous pelvic undulations—in LA, the symbols circulated anxiously from the Sunset Strip to the Valley. Up north, things got a little thicker:

youtube

“You low down punk,” indeed. The Nuns’ performance is feral, a species of glam, of goth rocked up with a punk edge. This version of “Suicide Child” was recorded the night they opened for the Sex Pistols at Winterland—the Pistols’ last show. The Nuns’ set that night included songs like “Smoking Heroin,” “Child Molester” and “Decadent Jew.” Despicable songs, all. But “Suicide Child” stands out for its intensity. One wonders about their invocation of California’s cultural geography: “You went away / Back to LA.” Is that a retreat? A rejection? A response to the Tubes cynical punk slumming? Band founders Jeff Olener and Alejandro Escovedo (who went on to play with the excellent Rank and File) met in a film class at a San Francisco community college. A middle-class Jew and a son of Mexican immigrants—neither had money to “waste time at every school in LA.”

By 1978, our current, dominant sense of “punk” had emerged, soaked in spit and covered in grime. Under the pressures exerted by class position and class struggle, punk’s petty thuggery has transformed into something else. Not a shallow guise of glamorous (but temporary) risk. But a sort of cultural armor. All of these valences of meaning remain, part of the resilience of that hardened surface and its livid, vivid way of being in the world.

*Throughout I am indebted to the researchers and writers of the Oxford English Dictionary for their extensive work on “punk,” and to the Rohrbach Library at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania.

Jonathan Shaw

6 notes

·

View notes