#utnapishtim

Text

"Disaster Taxon," poem assembled using text from Wikipedia articles

#wikipedia poem#wikipedia poetry#climate grief#grief#environmental grief#resilience#climate change#gilgamesh#flood narrative#post apocalyptic#poetry#my writing#wikipedia poems#weeds#plantarchy#mass extinction#dandelion#utnapishtim

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

#rin tohsaka#epic of gilgamesh#type moon#babylon#sumerian mythology#ishtar#babylonian mythology#gilgamesh#Mesopotamian mythology#enkidu#shamhat#utnapishtim#humbaba

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

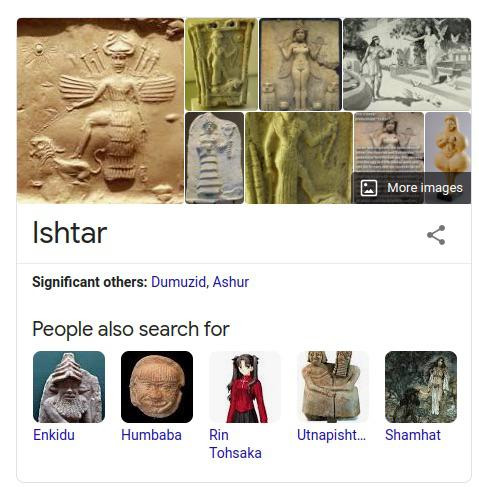

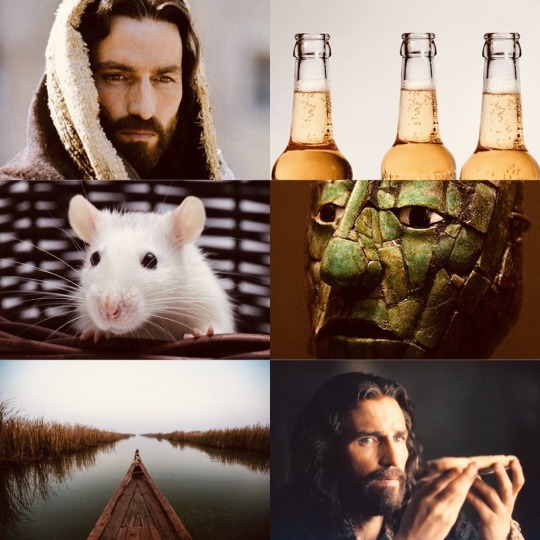

The Hermit. Art by Rubi Do Trinh, from the Star of Inanna Tarot.

𒑆 The Hermit 𒍪

The stories reflected in these cards are some of the oldest stories ever told. The story behind this card might sound familiar. In this card, we see Utnapishtim, a character from the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh. He was a mortal who has been granted immortality by the Gods because he saved animals and humanity when he built a large boat in order to save them from a devastating global flood sent by the Gods. He was then taken by the Gods to live alone at Dilmun, a remote and solitary place where the sun rises and creation occurs.

In the Epic, Gilgamesh is seeking the secret to eternal life. In his quest, he is told of Utnapishtim, who has learned that wisdom, because it was given to him by the Gods. Gilgamesh’s quest for wisdom from Utnapishtim reflects the archetype of the wise Hermit figure. We see Gilgamesh approaching on the boat in the card.

There is also an older Sumerian version of this tale that exists. In that one, Utnapishtim is called Ziusudra. There, he also builds a boat and saves the “seed of humanity”. He is then granted immortality and is taken to live solitarily in a land called Dilmun. Here we see the value placed on the concept of the “seed” by mesopotamians. To tie this story and characters to the deck, it’s important to point out that in both accounts, Inanna laments for the destruction of humans by the flood.

The stories we share in this deck often tie together aspects from the different cultures within the Mesopotamian timeline.

The Cuneiform is: 𒍪 dili - “alone, unique”

#Rubi Do Trinh#Star of Inanna Tarot#The Hermit#Major Arcana#Tarot#Folklore#Sumeria#Inanna#Utnapishtim

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallen London’s True Identities

Ut-napishtim as the Capering Relicker

#fallen london#capering relicker#fallen london’s true identites#true identities#utnapishtim#ut-napishtim#first city#my post#tw rats#tw masks

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the epic of gilgamesh#sumerian mythology#sumer#mythology#sumerology#uruk#gilgamesh#enkidu#shamhat#umbaba#utnapishtim#most fuckable#mesopotamia#heroes

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ho quattro nomi,

Ne conosco solo tre;

Come mi chiamo ?

HaikyouBao non datato esattamente, ma 2017.

Proietta il primo

Definisce il secondo

Il quarto canta.

Quel che ci è stato dato

Va ben restituito.

BaoUtnaFèretWaka, 27 marzo 2024 - 5.31, Kontowood.

“Esther”, Attributed to Kate Gardiner Hastings - British, 1837-1925 - ( vedi link primo commento )

“Utnapishtin” ( vedi link secondo commento )

“ ṛta “ : Concetto fondamentale della religione vedica, indicante l'ordine cosmico, la legge essenziale della realtà, l'esatto funzionamento di tutte le cose, cui presiede il dio Varuia. ( vedi link terzo commento )

#baotzebao#valerio fiandra#haikyou#kontowood#ilrestomanca#ildopovita#wakabaotzebao#dopovita#tiferet#rta#utnapishtim#nome#nomi

0 notes

Text

Cosmas Megalommatis, Atra-Hasis: World Mythology, Greek Pedagogical Encyclopedia, 1989

Κοσμάς Μεγαλομμάτης, Ατρά-Χασίς: Παγκόσμια Μυθολογία, Ελληνική Εκπαιδευτική Εγκυκλοπαίδεια, 1989

Кузьма Мегаломматис, Атрахасис (: Зиусудра): мировая мифология, Греческая педагогическая энциклопедия, 1989

Kosmas Megalommatis, Atraḫasis: Weltmythologie, Griechische Pädagogische Enzyklopädie, 1989

Kosmas Gözübüyükoğlu, Atra-Hasis: Dünya Mitolojisi, Yunan Pedagoji Ansiklopedisi, 1989

قزمان ميغالوماتيس، آترا-هاسیس : اساطیر جهانی، دایره المعارف آموزشی یونانی، 1989

Côme Megalommatis, Atrahasis: Mythologie mondiale, Encyclopédie pédagogique grecque, 1989

1989 قزمان ميغالوماتيس، أتراهاسيس: الأساطير العالمية، الموسوعة التربوية اليونانية،

Cosimo Megalommatis, Atraḫasis: mitologia mondiale, Enciclopedia pedagogica greca, 1989

Cosimo Megalommatis, Atrahasis: mitología mundial, Enciclopedia pedagógica griega, 1989

Cosmas Megalommatis, Atra-Hasis: World Mythology, Greek Pedagogical Encyclopedia, 1989

==============

Скачать PDF-файл: / PDF-Datei herunterladen: / Télécharger le fichier PDF : / PDF dosyasını indirin: / :PDF قم بتنزيل ملف / Download PDF file: / : یک فایل دانلود کنید / Κατεβάστε το PDF:

#Ατραχασίς#Ατρά-χασίς#Ουτναπιστίμ#Ζιουσούντρα#Ξίσουθρος#Ασσυρία#βαβυλωνιακά έπη#μεσοποταμιακές θρησκείες#Atrahasis#Utnapishtim#Ziusudra#Assyrian religion#Babylonian epics#Myth of the Flood

0 notes

Text

Sometimes Jake and I get vocab from our areas of study stuck in our heads and wander around the house like:

Me: Utnapishtim... Utnapishtim...

Jake *from another room*: coOGulated!

Me: ERESHKIGAL!

Jake: *beatboxing*

0 notes

Text

Is it a man?? Is it a god?? No,

It's Gilgamesh!!!

#when utnapishtim looks out to the sea#and sees gilgamesh and urshanabi manning a boat in the most fucked up way#and goes “who the fuck is that”#niko rambles

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly though like the cruel irony of Utnapishtim asking Gilgamesh "who will assemble / the gods for your sake?" when they've ALREADY assembled for Gilgamesh's sake like it was this confluence of the gods that made the decision to take Enkidu from him and sent him on this desperate journey in the first place

#please feel free to ignore this#I'm reading Gilgamesh#It's not like he 'went out from Uruk into the wilderness with matted hair in a lion skin' for fun#Literally everyone he meets on this journey to meet Utnapishtim is like why are you so sad and why do you look like dog ass#The gods have assembled! They decided to punish him by taking Enkidu away!#His beloved friend his beloved brother has turned to clay!!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

how are you going to assign me 750 words on UTNAPISHTIM don't you know he's my pookie ??? & i have to fit noah in here too ?? snzzzzz

0 notes

Text

In Paldea for a semester in Naranja

Currently helping my roommate and ex(?) Rival with things I will not be disclosing for his privacy.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Funny or interesting Epic of Gilgamesh tidbits

Nobody actually says Enkidu’s name before Shamhat shows up. His creation is essentially impersonal, and this is something that is brought up by Humbaba during the fight. There’s a pretty sound theory that Enkidu urges Gilgamesh to ignore his pleas specifically because Humbaba mocked his lack of biological parents. Note that at this point in the narrative Enkidu does not lack parents altogether, though, since Ninsun outright calls him a member of her family and de facto her foster child before he embarks on the journey to the cedar forest with Gilgamesh.

When Enkidu curses Shamhat on his deathbed for setting off the chain of events which lead to his incoming death, Shamash appears to him to inform him this was rude and uncalled for and urges him to bless her instead because he wouldn’t met Gilgamesh without her. Enkidu actually does listen and promptly does so... expressing the wish for her to supplant the wife of someone affluent. While the passage also has Enkidu curse the anonymous hunter, Shamash is not concerned about him, so he does not get an apology.

Speaking of the hunter - his name is only preserved in the Hittite adaptation of the epic, though it is Akkadian nonetheless. He is named Shangashu, which means “murderer”. His parents must have hated him.

Utnapishtim actually curses the ferryman who brought Gilgamesh to his realm, Urshanabi, presumably specifically because he did that. Urshanabi due to being out of job then tags along with Gilgamesh for the rest of the story, and the final words are addressed to him. He’s probably the most major character in the epic with virtually no presence in adaptations.

In the Hittite adaptation of the epic, Gilgamesh visits the personified sea, something virtually unheard of in Mesopotamia for the most part, and not exactly common in Hittite religion either, presumably a reflection of the popularity of the sea among Hurrians (his Hurrian sidekick Impaluri is there too). The sea promptly curses him, as far as the surviving fragments go just because.

The Hurrian version, which is too fragmentary for a proper translation, in addition to replacing Ishtar and Shamash with their Hurrian counterparts, Shaushka and Shimige, apparently inserts the de facto main character of most surviving Hurrian myths, Teshub, into the narrative.

It is also possible that there was a Hurrian rewrite of the epic focused on Humbaba, in which he either survived or was portrayed as a tragic figure. Granted, the latter is not really unusual, since the gods’ anger at Humbaba’s death does appear to reflect the opinion of the epic’s compilers, and Humbaba is well attested as a protective apotropaic figure.

For sources on all of the above and more, see my recently finished rewrite of the article on EoG characters on wikipedia. Most are open access!

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Epic of Gilgamesh: The World's First Big Budget Adaptation

My Yuletide assignment this year was an excuse for me to reread (and rediscover everything I loved about) The Epic of Gilgamesh ‒ and I can seldom resist the excuse to ramble about this kind of thing, but where do you even start, with a work like Gilgamesh? It’s the world’s oldest (known) work of literature, it features an all-but-canon m/m romance, and (even from incomplete reconstructions from languages which have been dead and alien for millennia) its central themes and most striking imagery still resonate to this day.

But perhaps my favourite thing is that it’s also what amounts to the world’s first ever big-budget adaptation of an existing story, complete with extra of sex and violence, a tropey bromance between its male leads, gratuitous cameos from other popular mythic figures, and even this one wonderfully confusing deleted bonus-scene, tacked on at the end like a DVD extra. I’m not even kidding.

Let me explain.

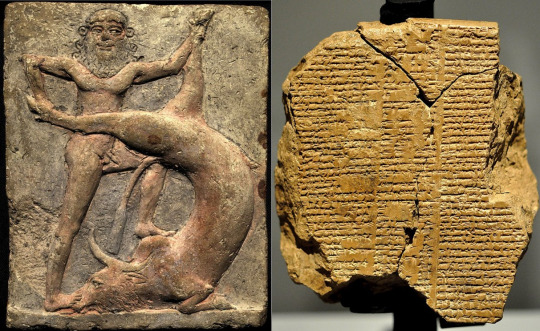

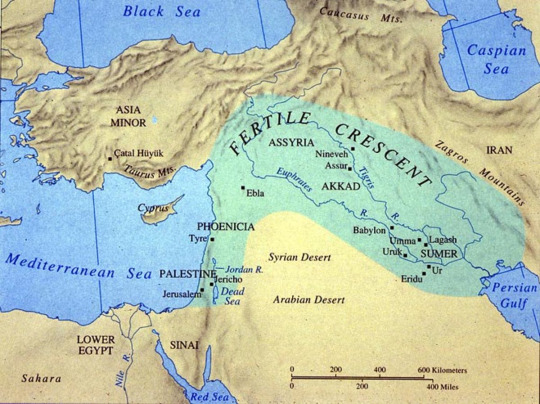

The oldest surviving stories about Gilgamesh – a semi-divine, semi-mythical Sumerian king – were inscribed on clay tablets in ancient Mesopotamia (modern day Saudi Arabia) somewhere around 2000 BC. Five distinct poems from this era have survived in variously-complete format. Gilgamesh and Akka tells of how Gilgamesh gained independence for Uruk from the kingdom of Kish (ruled by the titular Akka, in what seems to be the one Gilgamesh tale most likely to have some real historical basis). Gilgamesh and Huwawa and Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven both recount his battles with their respective monsters. Gilgamesh and the Netherworld deals with the death of his servant Enkidu, whose shade is briefly allowed to return to the mortal realms to report on what awaits in the hereafter. And finally, The Death of Gilgamesh deals with Gilgamesh’s death from illness, the gods decreeing that semi-divine isn’t sufficient for immortality.

But these aren’t the best-known version of Gilgamesh. A few centuries later, someone took those existing tales and reworked them into a single, cohesive epic, spanning 11 tablets (plus one confusing bonus tablet that we’ll get to later on). The new, integrated epic promotes Enkidu from merely a servant to Gilgamesh’s equal: created to be his companion by the gods, in answer to prayers of the people, exhausted by Gilgamesh’s tyrannical rule.

In all the best traditions of modern shonen manga, Gilgamesh and Enkidu meet, fight, and then become fast friends. Together, they battle both Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven, in episodes only lightly reworked from the original poems. But this time, these acts anger the gods, and their punishment is Enkidu’s death. Distraught at the loss of his friend, and faced with the horror of his own mortality, Gilgamesh goes on a quest to find the one man the gods ever made immortal: Utnapishtim, the Sumerian Noah (our gratuitous cameo). But Utnapishtim can only tell Gilgamesh that, short of saving the world from another biblical flood, his quest is a fool’s errand. Finally accepting his own mortality, Gilgamesh returns home. (This is, of course, a very summarised version of the full epic, but you get the general gist.)

Comparing the epic to the ‘original’ poems can be a little fraught, considering that even after reconstruction from multiple different partially-preserved copies, there are still gaps in both versions. We can only speculate whether there might have been other Sumerian poems that haven’t survived ‒ let alone how many other variations existed in oral tradition throughout the region and beyond. But for all the epic version adds and changes, what stands out most is how they’ve picked up and expanded on what was already the strongest running theme of the Sumerian stories: mortality – whether that be the desire to leave behind a record of great deeds to be remembered by (such as the slaying of monsters), or more explicitly in those final two poems, dealing with Enkidu and Gilgamesh's deaths.

For all that’s been added, the promotion of Enkidu to Gilgamesh’s equal does have more basis in the Sumerian originals that it might first appear. Though explicitly only 'a servant', Enkidu is the only other character appearing (or at least mentioned) in every poem, aiding his king in his struggles against Humbaba and the Bull of Heaven. In sending Gilgamesh to the netherworld upon his death, the gods even note that he will be reunited with his ‘beloved’ Enkidu, whose death he so fervently mourned. And though everything else in the circumstances of Enkidu’s death has been changed, both versions render it a major event, and one that leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken.

There’s even a trace of epic!Gilgamesh’s tyranny in Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, where he so exhausts the men of Uruk with his games and contests (similar accusations to the first chapter of the epic) that the gods themselves step in, arranging for his favourite toys to fall through a crack in the earth into the Netherworld (prompting Enkidu to volunteer to retrieve them… and you can see where this is going).

But for all the adaptation takes from those old poems, some of its most striking chapters are (as far as we know) completely new – including all of Enkidu’s backstory. The Gilgamesh of the epic is still respected as a wise and powerful ruler, and he still exhausts the men of Uruk with his contests, but now, he’s also been asserting his right to droit de signeur (yes, really – that trope goes this far back), and his people aren’t happy. The gods’ solution is to make the semi-divine Gilgamesh an equal: Enkidu the wild man, raised in the wilderness by beasts. Nearly as huge and powerful as Gilgamesh himself, Enkidu soon becomes a problem for hunters trying to make their living nearby.

How do you solve a problem like a wild man? Well, obviously, you introduce him to sex.

Gilgamesh’s solution to the Enkidu-problem is to send Shamhat, a cultic prostitute of the temple of Ishtar (ritual sex was apparently a Big Thing in some ancient fertility cults) – and it works. After a full seven days of sex with Shamhat (look, this is why you send a professional), Enkidu finds he can now understand the language of men, but the wild animals reject him. Something stirs in him when Shamhat tells him of Uruk and Gilgamesh, but the tipping point comes when he learns Gilgamesh is due to make a scheduled appearance at an upcoming wedding (ifyouknowwhatimean). Enkidu rushes to Uruk, intercepts Gilgamesh on the very doorstep of the bride in question, and the two demi-gods proceed to throw down. And then become instant BFFs. Seriously, I wasn’t kidding about how very Shonen Jump it is; I don’t know what else to tell you.

Now, to what degree these new intro chapters were an excuse to sex things up and get the audience’s attention, I can only speculate – but there is a lot of sex in these first two tablets (and next to none afterwards). Regardless, this feels like the perfect place to segue into what for many will be the more pressing question: just how gay is the Epic of Gilgamesh?

Because I mean, just on a surface level, it’s already pretty suggestive: Enkidu, having newly discovered sex, shows up to pointedly cockblock Gilgamesh’s appointment with a young lady, and one round of (ahem) "wrestling" later, suddenly they really like each other. And the mere fact the gods’ solution to "this guy keeps exhausting all our men and fucking all our women!" is to send him Enkidu… you’ve got to wonder if he’s just a wrestling partner on Gilgamesh’s own level, or is he meant to satisfy other needs as well?

But you really don’t need slash-goggles to find subtext in this tale. Even the academics are here for this one.

Significantly, Enkidu’s coming is foretold to Gilgamesh in a series of prophetic dreams, helpfully interpreted for him by the goddess Ninsun, his mother. In the first, Enkidu is represented by a meteor that falls down before Gilgamesh – and to quote George’s translation directly, Gilgamesh recalls, “Like a wife I loved it, caressed and embraced it.” This is not what you'd call ambiguous wording. His mother corrects this only in that the meteor is to be a man – and to drive this point home, Enkidu spends much of the rest of the poem being described as having strength “as mighty as a rock from the sky.” If that wasn’t all suggestive enough, one might also note that Enkidu does his share of “caressing and embracing” (that same wording, presumably going all the way back to the original language) of Shamhat during their week-long sex marathon too.

Then Gilgamesh has his second dream – almost beat-for-beat identical to the first, except that now Enkidu appears as an axe rather than meteor. This is a little more confusing. Both are certainly dangerous objects which hit hard, but axes don’t generally fall from the sky, and Enkidu is never compared to an axe again. So why include it?

The most compelling (and really the only) academic explanation I’ve seen put forward is that both objects may be playful Akkadian puns. Kisru (meteor) evokes kezru, and hassinu (axe) evokes assinnu – and both kezru and assinnu are apparently terms for types of male cultic prostitute: men who have sex with other men. Lest you wonder if this might be reaching, that amazing “Like a wife I loved it” line is still right there. It all adds up.

Before we get too carried away with pre-historic queer representation though, it’s notable that even in a time where apparently no-one batted an eye at male cultic prostitutes, the Gilgamesh/Enkidu subtext would be left largely as the stuff of implication – but the pattern is also weirdly familiar. Like modern media adaptations from Sherlock to Captain America: Winter Soldier, it’s plain the screenwriters absolutely want to imbue their central male/male relationships with all the intensity and pathos (and maybe even a bit of wink-wink-nudge-nudge) of a romance, and yet stop short of making it explicit. I cannot begin to guess whether the same forces were in play here, but the resonance is still pretty striking.

We’re still not done with gay-Gilgamesh-shenanigans though, because we’ve still got to cover that mysterious, DVD-extra of a 12th tablet, which may-or-may-not include an actual, textual statement of how much Gilgamesh likes handling Enkidu’s dick.

This one is going to need some more context. See, the 12th and final tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh consists of a fairly-literal Akkadian translation of the latter half of the original Sumerian poem, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld. Narratively speaking, this is a bit of a record-scratch moment, because not only has the epic already reached its logical conclusion as of the end of tablet 11, Gilgamesh and the Netherworld is the one that revolves around the death of Enkidu – and in the new epic version, Enkidu has already died in completely different circumstances, way back in tablet 7. So what the hell is it doing here?

The best guess as to why anyone felt the need to include this episode in its original form is that the bulk of the original Sumerian poem relays a detailed account of how one’s actions in life will affect one’s prospects in the hereafter. Enkidu’s shade dutifully reports that a Sumerian citizen who hopes to be comfortable in the netherworld must have plenty of sons (to make offerings in the name of their departed father), must show respect to the gods, must die peacefully – the list goes on. The material has transcended the world of poetry and moved into scripture – and that may have been considered worth preserving long after the original tales were lost.

So where does the dick-touching come in? Brace yourselves: Enkidu’s account of the netherworld includes some graphic details about what happens to your junk. That crotch you touched, so that your heart rejoiced, is filled with dust like a crack in the ground. And so on.

Here’s where making definitive statements about this passage get messy. There are at least two different versions (the original Sumerian and the one from the epic) in different languages, and not always preserved well enough that all the words are still legible. So I’ve seen translations where it seems to be Enkidu’s own body that Gilgamesh ‘rejoiced to touch’. I’ve seen versions where it seems to be some unnamed woman’s body instead. Or maybe Enkidu’s saying that even having a wank isn’t worth much rejoicing in the afterlife (and for the record, I’ve seen all the above in just the work of just one author, Andrew George. Consensus is not a luxury we have here). There’s some ambiguity there, and I have no idea how much of that is down to interpretation, translation, or the actual state of the text. The 12th tablet of the epic of Gilgamesh remains a mystery stuffed into an enigma (then presumably filled in with dust).

Anyhow, back to the main text of the epic. From the meeting of Enkidu and Gilgamesh, things happen surprisingly fast. Gilgamesh immediately proposes a trip to the cedar forest to slay the monster Huwawa: an act which so impresses the goddess Ishtar that she hits on Gilgamesh, he rejects her, and she sends the Bull of Heaven to punish him. Angered by the death of both Huwawa and the bull, the gods inflict a fatal illness on Enkidu, whose death leaves Gilgamesh heartbroken. Like screenwriters trying to cram everything from Captain America’s origin story to his emergence from the ice into a single movie, the complete tale of Gilgamesh’s time with his literally-god-given-soulmate seems like it’s been compressed down to maybe a couple of months, max. But such is the nature of adaptations like this one.

But the best parts of the epic are hardly over. Gilgamesh’s search for Utnapishtim, the one man ever made immortal by the gods, will see him meet scorpion men and stone men, will take him across a sea whose very touch is death, and force him to race the sun through the tunnel it takes each night under the earth. He finds the man he seeks at the end of the world – which is our poet’s excuse to include the entire Sumerian flood myth in the narrative, as Utnapishtim recites exactly what he had to do to earn his immortality.

Gratuitous as it may be, this is not a complaint. I kind of love the pre-biblical Sumerian version of this story – not least because, despite being initiated by the most revered of the gods, the deluge sent to punish mankind for their ills is unambiguously framed as a mistake. Mankind is saved only because Ea, wisest of the gods, sneakily breaks his oath of secrecy by alerting Utnapishtim to the danger and directing him to build his ark – and Ea gets away with it by directing his warning not to the man himself but to the fence outside his home, so he can honestly tell the other gods “Who me? I didn’t tell anyone, I only whispered it to a fence!” (I like to imagine him walking away from that initial meeting with the other gods rolling his eyes, going, “Well someone’s gonna regret this in the morning, you just wait. Alright, alright, damage control time…”)

And the gods absolutely do regret the deluge. When at last the rain stops, and Utnapishtim lights some incense in ritual thanks to the gods for his survival, the text describes the parched gods clustering around the smoke of the offering like flies. To find something like that – that comes so close to suggesting that the gods themselves depend on humanity for some measure of their power and comfort – in a text this old blows my mind a little. It’s also a hell of an image.

In any version of Gilgamesh, the general attitude to the gods has a lot of commonalities to what you’d find in, say, Greek mythology. The gods are absolutely divine and worthy of worship, but also come across as one huge, long-running soap opera of privilege, dysfunction and pettiness. Even the Athenians, though, generally kept the image of their patron goddess Athena reasonably clean. By contrast, when Uruk’s own patroness Ishtar appears in the tale, her role is to hit on Gilgamesh, be rejected, go crying to her father for help, and send the Bull of Heaven down for revenge. Gilgamesh insults her, kills the bull, and even hurls part of its carcass at her as a parting blow. He then makes flasks of its horns and presents them to her own temple in her honour. For bonus confusion, the original Sumerian Gilgamesh and the Netherworld also opens with a passage where Gilgamesh does Ishtar a much-appreciated favour in clearing out the demons infesting a divine tree. What on earth are we supposed to make of it all? The worship of Ishtar must have taken some truly god-level compartmentalisation.

Much as I love Gilgamesh, some of it is inescapably pretty impenetrable to the casual modern reader. If you were paying attention back at that very first bit about Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, for example, you might have caught that plot point where the great king Gilgamesh so exhausted all the men of Uruk with his games that the gods themselves had to step in and take his toys away. What those toys were isn’t totally clear, but the best guess seems to be a ball and a mallet. These were made of wood from that divine tree, but even so – was ancient Sumerian croquet really that intense? You’ll run into stuff like this a lot reading any version of Gilgamesh – scholars will do their best, but some of it just doesn’t translate, reminding you you’re reading something written in a cultural context no-one’s seen in over 4000 years.

But that only makes it all the more fascinating when (like finding bits of Shakespeare in the infinite monkey cage) you run into the stuff that does still resonate. I could not tell you why Gilgamesh begins his case for why they should rebel against Kish with a spiel about the digging and/or operation of wells – but then you get to the bit where Akka compares Uruk with its great city walls of Uruk to a cloudbank sitting on the earth, or the part where Enkidu finally responds to Akka’s repeated demands of, “Slave, is that man your king?” with, “That man is indeed my king!” – and even separated from the poet by several millennia and the hard work of so many archaeologists to piece this thing back together, the words and the imagery still get me.

I could go on here. There’s so much I love in the various versions of Gilgamesh, so much that fascinates me and confuses me (and has very much tipped me back down multiple research rabbit-holes trying to get my head around it). But as both a gigantic nerd and fanfic writer, my favourite thing might still be learning just how far back the human tradition of telling and retelling old stories goes, recreating and adapting them in new formats, to resonate with new audiences. There isn’t a doubt in my head that even way back in ancient Akkadia, there were grumpy old fans arguing that this modern newfangled epic isn’t a patch on the proper old Sumerian poems – look at all the good bits they skipped and all the stuff they got wrong! Why, you realise they aren’t even teaching scribes proper Sumerian in school anymore? Pah, no respect for the classics!

Anyway, if you’ve never read the Epic of Gilgamesh in full (and it’s really not so long it’ll take you long to do), this would be my cue to recommend you Stephen Mitchell’s version as probably the most accessible English language introduction. This one is (in his own words) explicitly a version, not a translation: Mitchell isn’t a Mesopotamian scholar, but a poet, and his goal was to create something in semi-modern verse that captures as much of the original as possible in a format more accessible to the contemporary English-speaking reader ‒ patching over the holes as best as possible. And I can only applaud him the effort: after all, it’s nothing people haven’t already been doing with Gilgamesh for thousands of years.

But if you’d like to go a bit further down the rabbit hole, my other key source was Andrew George’s translation. George is an academic, and his version is a far more literal translation, preserving the gaps where we still don’t know exactly what’s missing, but including as much as possible from the various different versions which survive to us in different places – including those original Sumerian poems. Both Michell’s and George’s books are available quite cheaply as ebooks. (George’s much-longer and much-more-academic two volume work on Gilgamesh isn’t available as an ebook, alas, but can also be found in pdf format pretty easily on the web too).

Finally, I’ve got to rec you Irving Finkel’s talk on his work on even older versions of that flood myth – it’s only tangentially related to Gilgamesh, but damn, it’s fascinating too!

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

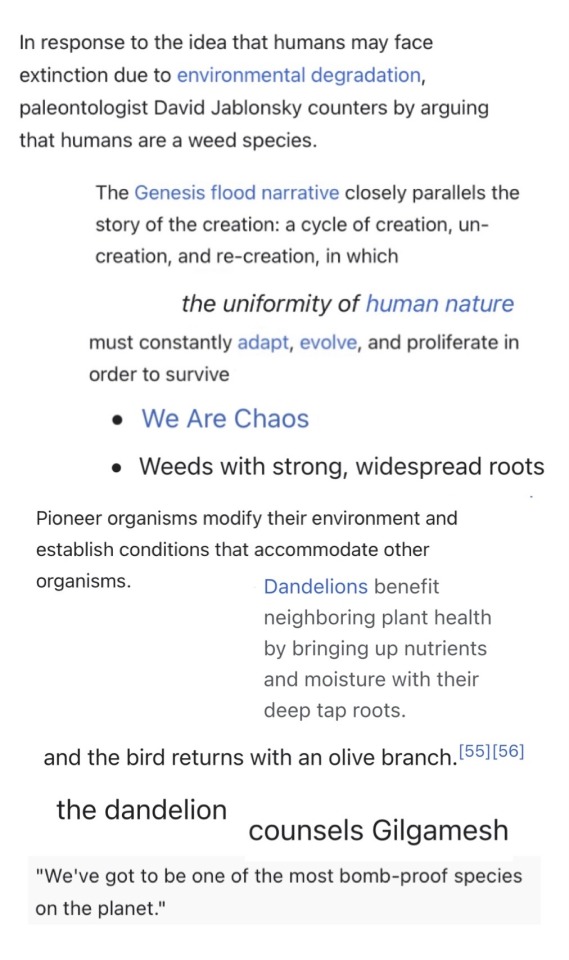

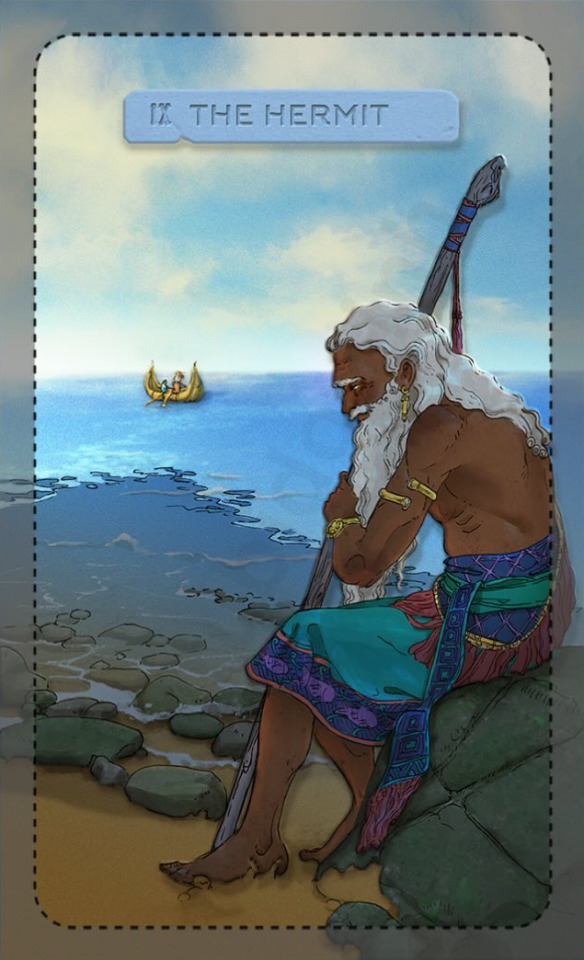

i posted this on twitter but here's a fanservant design for utnapishtim/ziusudra/atrahasis! copious design notes under the cut

disclaimer its been a hot second since i played babylonia so i dont exactly remember what the deal with him in babylonia was (did he turn out to actually be grandpa hassan. did they meet ziusudra [real] at any point. i dont know) but since im so into mesopotamia i thought i might as well make another design anyway

"why does he look like nemo" he looks like nemo because noah looks like nemo in arcade, and the same story motif (from lb6) that leads nemo to be noah's host [?] body [?] also applies to utnapishtim since utnapishtim and noah most likely are cognates stemming from the same "ur-myth" of the flood

because there are a couple of inverted artifacts from noah's story compared to utnapishtim's (the dove vs. the raven being the bird of significance), i've inverted some of utnapishtim's colors compared to noah. utnapishtim has silver hair compared to noah's warm-toned hair, and the color of their top and bottom is switched

speaking of the raven i didn't draw it but it's utnapishtim's cute mascot thing

a couple of the design motifs are based on either oceanic items or oceanic puns (again because of the flood thing). the fishtail braid is a pun. the gray shoulder sashes are meant to look like fishing nets (this idea was half borrowed from samrem) and are also references to egyptian beaded dress, since there was so much trade between mesopotamia and egypt during some ancient periods

the structure of the waist sashes and pants are half-noah, half-based on that one gilgamesh skin from CCC. the pattern on the teal sash is based on floor tiles from nimrud/assyrian palaces; the color scheme of the other one is meant to look like seafoam

the gold decorations on his chest, in his hair, and on his arms are referenced from a suit of jewelry i saw in a near east artifact exhibit. the shoes are freestyle though (and are sort of like caster gilgamesh's?)

in the epic, gilgamesh finds utnapishtim after going through a garden at the edge of the ocean with plants made of [?] carnelian, hematite, lapis lazuli, etc. and meeting siduri. because of this i wanted to have all three of these specific stones represented (the red, blue, and black)

he is most likely a rider because of the significant role his boat plays in the legend, undecided if his NP is "he who has found life" (translation of his name) or "preserver of life" (the name of his boat). the former sounds cooler but the latter is more direct

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

there is a correct answer here btw

#pls be niceys about this idk what else to do with these polls#epic of gilgamesh#also i am not putting everyone in here jfjdjdjd

63 notes

·

View notes