#völsunga saga

Text

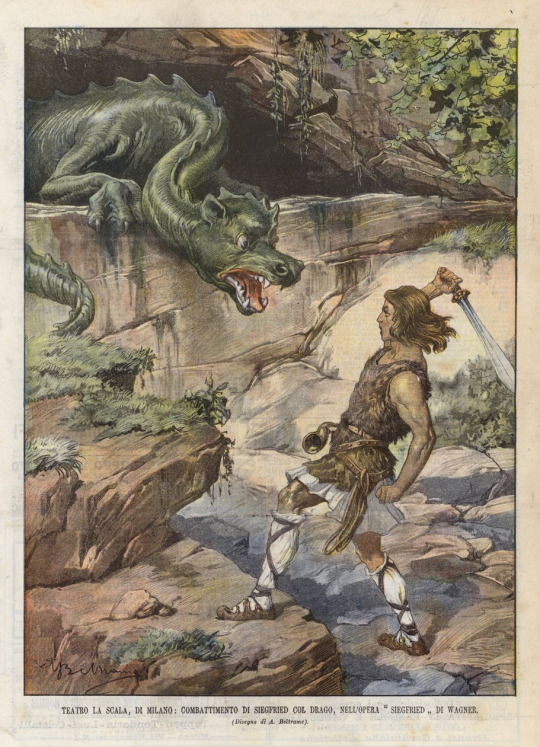

Siegfried Fighting with the Dragon by Achille Beltrame

#siegfried#dragon#art#achille beltrame#fafnir#fafner#dragons#richard wagner#milan#theatre#la scala#opera#der ring des nibelungen#the ring of the nibelung#german#germany#germanic heroic legend#norse mythology#germanic mythology#nibelungenlied#fáfnir#europe#european#mythical creatures#sword#gram#nothung#balmung#völsunga saga#sigurd

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

„WALKÜRE“ R. Wagner / SECOND and THIRD ACT

Some Brünnhildes

Amalie Materna as Brünnhilde; Bruxelles, 1889

Pauline Mailhac as Brünnhilde; Karlsruhe, 1891

Ellen Gulbranson as Brünnhilde; Bayreuth, 1902

Lucienne Breval as Brünnhilde; Paris, ca. 1900

Anna Bahr-Mildenburg als Brünnhilde; Vienna, ca. 1900

Laure Berge as Brünnhilde; Bruxelles, ?

Elise Beuer als Brünnhilde; ?, ?

Olga Blomé as Brünnhilde; Bayreuth, 1924

Lina Boeling as Brünnhilde; ?, ?

Helena Braun as Brünnhilde; Munich, ?

Gertrud Bindernagel as Brünnhilde; ?, ?

Berthe Briffaux as Brünnhilde; Antwerpen, 1932

Lotte Burck as Brünnhilde; Milan, 1932

Sara Cesar as Brünnhilde; Rome, 1920

Sofie Cordes-Palm as Brünnhilde; ?, ?

Erna Denera as Brünnhilde; Berlin, ?

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Die Walküre#The Valkyrie#Richard Wagner#Wagner#Der Ring des Nibelungen#The Ring of the Nibelung#Norse mythology#Völsunga saga#Poetic Edda#classical musician#classical mythology#classical musicians#classical voice#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#music education#music theory

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Otters are adorable. Since 2015, the Swedish otter population has been stable. Which makes me really happy!

Otters used to be trained to catch fish. There is an article (in English!) about this practice, 'Sometimes it is Tamed to Bring Home Fish for the Kitchen': Otter Fishing in Northern Europe and Beyond (Ingvar Svanberg, Tommy Kuusela and Stanisław Cios). It features stories like this one:

"At one time, I had three otters that I had tamed myself. They used to run around freely between the houses at night and get up to mischief. Folk used to knock on my door and say, either there are ghosts in the village or it is your otters that are roaming about. Then I would take a couple of salted whitings with me and the otters always followed me back home like puppies."

- Axel Karlsson (b. 1874), Bohuslän

There is also the story of an otter named Ludde, who was accused of killing chickens, but was proven to be innocent.

I highly recommend the article. It is available for free as a pdf at the bottom of this article (click on 'Svenska landsmål och svenskt folkliv 2015').

In the Völsunga saga, Loke sees an otter eating a salmon. He, or him, Oden and Höner together, then kills the otter (killing two birds with one stone, as he/they gets the salmon too). Later, it is revealed that the otter was Utter (Ótr) - the son of Reidmar. Loke (or the entire trio) has to compensate Reidmar for the loss of his son: as much gold as is needed to cover the otter skin from the nose to the tip of the tail. (Utter is the Swedish word for otter.)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

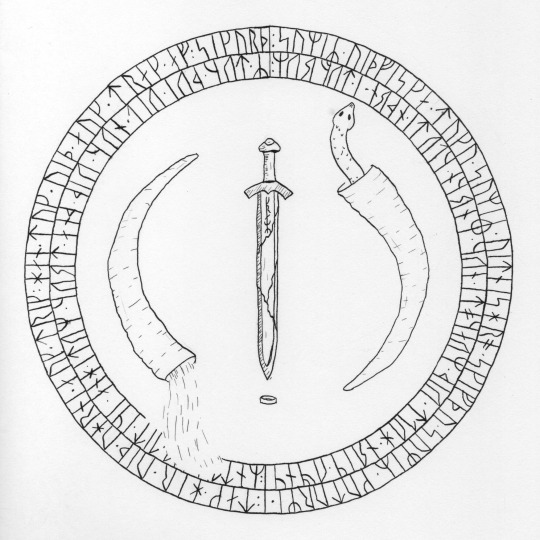

Runetober Day 4: Potion

(following the woodland magic prompts by smalltownspells)

This piece references the Völsunga saga. In particular two of the potions mentioned in it. The horn on the left contains the love potion which lets Sigurd forget about Brynhild and his oath to her. The passage from Völsunga saga chapter 27:

"Take this horn and drink. He accepted the horn and drank its contents completely. [...] Sigurd took this gladly, and after he had drunk from the horn he forgot Brynhild."

The potion in the drawing spills over the name Brynhild covering it up.

On the right is the potion given to Guttorm in chapter 30 to give him the courage to attack and kill Sigurd:

"They took snake-meat

and wolf-meat

and gave it to Guttorm,

blended with beer

and many other things

in the enchanted drink"

These two potions are accompanied by the other two artifacts that also create Sigurds fate: The reforged sword Gram and the cursed ring Andvaranaut.

The two passages in Old Norse:

"Tak hér við horni ok drekk.

Hann tók við ok drakk af.

Sigurðr tók því vel, ok við þann drykk mundi hann ekki til Brynhildar."

"Sumir viðfiska tóku,

sumir vitnishræ skífðu,

sumir Guttormi gáfu

gera hold

við mungáti

ok marga hluti

aðra í tyfrum."

In runes:

:ᛏᛅᚴ·ᚼᛁᚱ·ᚢᛁᚦ·ᚼᚢᚱᚾᛁ·ᛅᚢᚴ·ᛏᚱᛁᚴ:ᚼᛅᚾ·ᛏᚢᚴ·ᚢᛁᚦ·ᛅᚢᚴ·ᛏᚱᛅᚴ·ᛅᚠ:ᛋᛁᚴᚢᚱᚦᛦ·ᛏᚢᚴ·ᚦᚢᛁ·ᚢᛁᛚ:ᛅᚢᚴ·ᚢᛁᚦ·ᚦᛅᚾ·ᛏᚱᚢᚴ·ᛘᚢᛏᛁ·ᚼᛅᚾ·ᛁᚴᛁ·ᛏᛁᛚ·ᛒᚱᚢᚾᚼᛁᛚᛏᛅᚱ:

:ᛋᚢᛘᛁᛦ·ᚢᛁᚦᚠᛁᛋᚴᛅ·ᛏᚢᚴᚢ·ᛋᚢᛘᛁᛦ·ᚢᛁᛏᚾᛁᛋᚼᚱᚬ·ᛋᚴᛁᚠᚦᚢ·ᛋᚢᛘᛁᛦ·ᚴᚢᛏᚢᚱᛘᛁ·ᚴᛅᚠᚢ·ᚴᛁᚱᛅ·ᚼᚢᛚᛏ·ᚢᛁᚦ·ᛘᚢᚾᚴᚬᛏᛁ·ᛅᚢᚴ·ᛘᛅᚱᚴᛅ·ᚴᛚᚢᛏᛁ·ᛅᚦᚱᛅ·ᛁ·ᛏᚢᚠᚱᚢᛘ:

#mine#my art#runetober#runes#inktober#drawtober#smalltownspells#sigurd#siegfried#niebelungenlied#völsunga saga#potion

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

love when you see unsourced unfindable quotes from famous people

0 notes

Text

[Viking AU] A New Home

Sigmund and Signý (Vygo and Indrys' names in this AU, based on the characters from the Völsunga Saga) finally found a good place to settle and make their nest!

[OC: Sigmund and Signý)

More on my SubscribeStar.

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ramsund carving, believed to have been carved around 1030, was found close to Ramsund, Sweden. It is considered part of the “Sigurd stones”, a group of eight or nine runic inscriptions which can be found in Sweden, with all pertaining to the myth of the hero Sigurðr. The Ramsund stone depicts scenes from the Völsunga Saga, which go as follows:

Sigurðr preparing a fire to roast the dragon Fáfnir’s heart, as instructed by his uncle Regin. Having burnt himself in the process, Sigurðr sticks his finger in his mouth. He is soon to discover that the dragon’s blood which stained his finger gave him the ability to understand the language of birds as they sang.

The birds warn Sigurðr that Regin intends to kill him and take the dragon Fáfnir’s treasure for himself.

This prompts Sigurðr to end the life of his treacherous uncle, whose body now lies next to his smithing tools.

Sigurðr’s horse Grani now carries the dragon’s treasure.

Depiction of Sigurðr killing Fáfnir: having concealed himself in a hole outside the dragon’s lair, he waited for it to crawl outside and towards the river to go and drink so he could stab upwards into the beast’s heart.

Depiction of the three brothers, Regin, Fáfnir (whose greed turned him into a dragon), and Ótr, who appears along with his brethren at the beginning of the saga.

#heathenry#sagas#runestones#norse paganism#spirituality#norse myths#mythology#myths#paganism#polytheism#runes

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Recommendations (from a lit grad student)

So, as I have come to the end of my MA in world lit, I thought I should give you a list of some of the best books I've read, or learnt from. I ignore established canon and give to you recommendations from across the globe and across all genres. Books that defined their genre, or made an impact, or are just really cool and enjoyable to read. This list is not all dead white men.

I have split the list by era/year of publication primarily for easy reading. A lot of the sections are arbitrary. Some of them are not.

Note: This list is not conclusive! This is based on my own readings, and my own, personal, opinions. You have the right to your own opinions and preferences. If you have any suggestions, add them on below.

Classic lit (pre-1700)

Aristole - Poetics (c. 335 BCE)

As much as I hate it...this one is actually pretty important. I know I said 'contributions to literary canon don't matter', and here I am, immediately doing the opposite. But! Aristotle's Poetics is the earliest treatise on literary theory that has survived to the modern day. You want to know where our ideas of comedy and tragedy come from? Poetics. Three act structure? Poetics. Plot and character? Poetics. Key terms like catharsis, hubris, hamartia? Poetics. We had to read this for creative writing, and did I hate it? Yes. Am I a better writer for having read it? Also yes

Plato - The Republic (c. 375 BCE)

Plato is quite easy to read, of the classical philosophers. His works are mostly dialogues between characters, which makes them more engaging that some other dry philosophy texts. I wrote out a longer post with an explanation of Plato's Republic specifically here.

Genji Monogatari (pre-1021)

The first novel ever! Originally written in Japanese, be careful of your translations because most are of questionable quality. I've only read the first one by Suematsu and that's uhhhhh Bad™ but I think the current waterstones edition is decent?

The Völsunga saga OR The Vinland sagas (early 13th century)

Ah, how to choose just one Norse saga? These are both pretty solid examples of their style, and short (always a plus). The Völsunga saga was the inspiration behind Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen (famous for the piece The Valkyrie), and most likely Tolkien's works. The Vinland sagas supposedly have an anime/manga series inspired by them, though looking at the synopsis I cannot see where the inspiration was other than time period. Norse sagas - especially the Icelandic ones such as Vinland - are actually pretty good guides to real historic events, which is very cool. I could go on for hours about this, but I'll spare you the rambling.

Thomas More - Utopia (1516)

Lovely little sarcastic book about tudor politics and human nature all wrapped up in the original 'utopian text'. Surprisingly funny for something written so long ago, and very easy to read. I wrote a longer post about it here

Aphra Behn - Oroonoko (1688)

Hated it, but the themes are interesting and wow did the author lead an interesting life. Widely considered to be the first novel written in English, deals with colonialism, slavery, and honour, and Aphra Behn was a spy? I'm sure some of you will eat that up. Be warned, very 'noble savage'-y book, but less racist than it could've been so cool, I guess?

Early Modern Drama

Christopher Marlowe - Edward II (1592)

Gay. So gay. We're not supposed to call it gay (because of a whole host of reasons that I can and will explain if anyone shows up in my askbox complaining about academics) but it is a very very queer play and Kit Marlowe was too which is even better. Also our one and only history play on this list. Anyone who already knows how Edward II died (thanks horrible histories) do not spoil the ending.

Shakespeare - Twelfth Night (1602)

As with any Shakespeare, watch a performance if you can. I highly recommend the National Theatre version that was up on youtube in 2020. Very gay, no one is cishet. Lots of singing and dancing. Prime example of Shakespeare's comedies with added gender shenanigans.

Shakespeare - Hamlet (1609)

Yes I'm basic. Yes I like Hamlet. In the same way that Twelfth Night is a great example of Shakespeare's comedies, Hamlet is a good example of his tragedies. Mostly, though, I'm recommending this because the castle it's set in in Denmark (Elsinore) a) actually exists and b) does an amazing educational programme, with live actors performing scenes all across the castle! Watching the 'to be or not to be' soliloquy in the banquet hall just adds a whole other level to the experience of reading the play.

Shakespeare - Measure for Measure OR The Tempest

Shakespeare's problem plays. I couldn't pick just one, because they're both fantastic in different ways. Measure for Measure features what can only be described as the early-modern version of an ace protagonist - Isabella - who I adore. The Tempest has a really interesting portrayal of early colonialism and slavery. The reason they are 'problem plays' is they check all the boxes for a comedy...but they're not funny. At all. And they also check some of the boxes for a tragedy. They're certainly interesting reading

Ben Jonson - The Alchemist (1610)

Just a really good, solid play. Very funny. Bunch of con artists set up an elaborate scheme to rob rich people. Also very good for showing class structures of the time. Shakespeare gets all the recognition for this era but Jonson is just as good really, and definitely as clever.

Regency and Victorian lit (1700-1900)

Jane Austen

Literally anything by Austen. She is just so funny, so witty, and I wholeheartedly believe she'd be a feminist today. Master of the female gaze in literature, but beyond that she is basically credited with the invention of free indirect discourse, which is super cool. I have only read Pride and Prejudice, but I have heard good things about most of her books, so I don't feel bad recommending all of them.

William Blake

There's one poem by Blake about a London street urchin that breaks my heart every time I read it and that is the sole reason behind this recommendation I hate Romantic poets.

Mary Shelley - Frankenstein (1818)

You knew it was coming. First sci-fi, gothic horror, teenage girl writer. Gotta love Shelley.

Frederik Douglass - Narrative of the Life of Frederik Douglass (1845)

You know those books that are horrifying because they're real? That's this book. Doesn't shy away from the horrors of slavery and for a reason. This is an autobiography. It is not fiction.

Gowongo Mohawk - Wep-ton-no-mah (1890s)

My favourite play of all time. You will need to do a trip to either the British Library or the Library of Congress to read it because there are no other copies, but I did do a whole podcast episode about it because I'm apparently the expert? You can find it here.

Bram Stoker - Dracula (1894)

I know here on tumblr we adore Dracula, and for good reason. It's horrifying, it's got a blorbo, if you haven't read it already, go with a dracula daily read-through or @re-dracula for the best experience. (Re:Dracula also has episodes where they get scholars on to talk about things like racism and gender and queer theory surrounding the text which is SO COOL as an ex-lit student I love listening to those episodes.

Post-1900

Oscar Wilde - De Profundis (1905)

We had to read a snippet of this for A-Level and I wish it had been more because wow. Most lists like this will recommend Dorian Gray because it's a novel, but De Prof is so heartfelt and beautiful and sad and deserves to be read.

Baroness Orczy - The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905)

First masked vigilante/superhero! If you like comic books or superhero media, this is where it all started (funny how all the firsts so far have been written by women 🤔)

Erich Maria Remarque - All Quiet on the Western Front (1929)

If you only read one book in your life about WW1 make it this one! It is heartbreaking and beautifully written and makes you feel so many things. It was banned in...a lot of places for being anti-war (especially as WW2 came closer) and also because it was written by a German who was anti-war which was apparently impossible to comprehend. The prose is truly something to behold.

Modern lit (Post-war era)

George Orwell - 1984 (1948) OR Animal Farm (1945)

Which one you should read depends a lot on how long your preferred book is and how metaphorical your tastes are. Both are very good explorations of corrupt governments. Animal Farm is an easier read and shorter and is much more allegorical. 1984 is very in-your-face about how much authoritarian governments suck. Do not discount 1984 just because Winston is a terrible person. Everyone knows he's terrible. That's the whole point. He is a normal terrible person, not a cartoonishly evil terrible person, or an angelically perfect revolutionary. All the characters are realistic for their situation.

Maya Angelou - I know why the caged bird sings (1969)

Another one with some beautiful prose. She's a poet and you can tell. It's an autobiography, plus there's a lot of clever stuff going on with how it's written. You could write an essay about this. I did.

Ghassan Khanafani - Return to Haifa (1969)

A short story by a Palestinian author - we were given this by our Palestinian lecturer as an intro to the conflict and the terrible things that colonialism has done to the region. Additionally, there are notes throughout that help explain the significance of things and background and all that jazz. There is a play version that is probably easier to find because it was published more recently but it's not as good.

Ben Okri - The Famished Road (1993)

I did not read this book for uni and I think that may have influenced my opinion of it slightly but I still credit it as one of the reasons I got interested in world lit and translation. It's a really beautiful exploration of Nigerian mythological tradition and its effect on family and politics in this kind of fascinatingly weird style that's both magical realism and modernist? I hate modernism but love magical realism more so.

Carmen Maria Machado - In the Dream House (2019)

What a book oh wow. It reads like poetry. I cannot think of anything coherent to say my brain is screaming. The novel explores abuse in queer relationships, which is something people don't normally talk about, through some very interesting motifs and I love it so much. It is hard to read, but very rewarding.

#studyblr#english lit student#bookblr#book recommendations#maybe i will do another one for theory#maybe i will not#classics#literature#the lack of early 1900s stuff distresses me but also#i am not and never have been a fan of that era#i am not willing to inflict virginia woolf or ts eliot on anyone#my specialties are all pre-1900 or post-war soooo

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sigmunds Schwert - Sigmund's Sword by Johannes Gehrts

A mysterious, Odin-like figure presents the sword he has stuck into the tree Barnstokkr

#sigmund#sword#schwert#gram#odin#oak tree#barnstokkr#art#johannes gehrts#norse mythology#germanic#nordic#norse#mythology#mythological#völsunga saga#old norse#magic sword#tree#völsungs#völsung#europe#european#barnstokk#balmung#nothung#history

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome back to very dumb HC that I think is hilarious: i think Iceland can recite the Edda and a lot of the sagas word for word and if u don't periodically indulge him with "hey Ari why don't you tell us a story?" he will just start doing it randomly and if you don't listen he'll be super offended about it. Like hold a grudge for six months offended.

Once he started doing it during a break at a UN meeting, like just started reciting the Völsunga Saga, in Old Norse, no one cares but he's gonna do it bc dammit he wants to tell a story >:(

Germany, sitting across the table, is not dealing with this today. Looks him directly in the eye and starts reciting Nibelungenlied back at him. In Old High German. Neither of them stop, and they get to the point where the break is over and no one stops them either. This is war now.

#germany will eventually admit to having spent MONTHS memorizing it in hopes this would happen#it was a power move and everyone supported it.#hws iceland#hws germany#hetalia

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

„WALKÜRE“ R. Wagner / FIRST ACT

Some Sieglindes, Siegmunds and Hundings

Maria Müller (29 January 1898 – 15 March 1958); Czech-Austrian lyric/dramatic soprano, Emanuel List (22 March 1888 - 21 June 1967; Austrian-American bass and Franz Völker (31 March 1899 – 4 December 1965); dramatic tenor, Bayreuth, 1933

Maria Müller as Sieglinde, Bayreuth, 1937

Martha Leffler-Burckhardt (16 June 1865 -14 May 1954); German soprano as Sieglinde, Bayreuth, 1908

Rose Pauly-Dressen (15 March 1894 – 14 December 1975); Hungarian dramatic soprano as Sieglinde, Frankfurt, ?

Martha Selle as Sieglinde, Breslau, ?

Florence Easton (25 October 1882 – 13 August 1955); English dramatic soprano as Sieglinde, Berlin, ?

Marie Thoma as Sieglinde, Schwerin, ?

Elvira Herz as Sieglinde, Berlin, ?

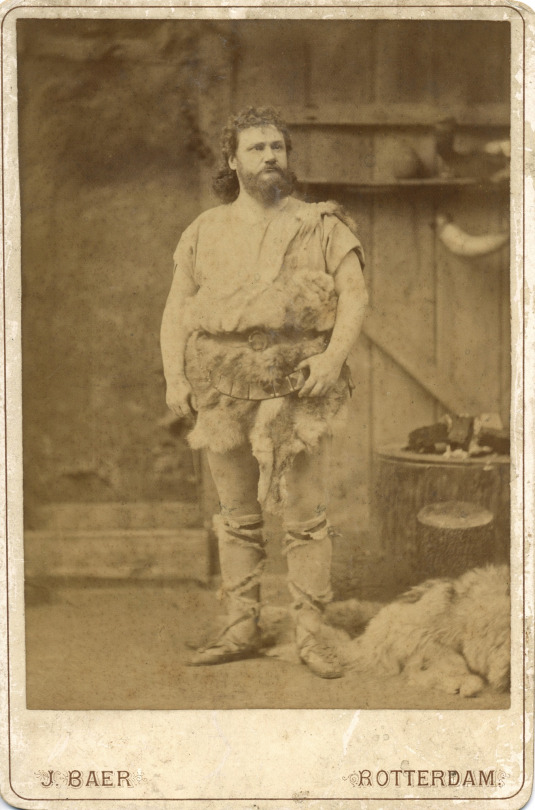

Adolf Gröbke ? (26.5.1872 -16.9.1949); German tenor as Siegmund, Rotterdam, ?

Lauritz Melchior (20 March 1890 – 18 March 1973); Danish-American heldentenor as Siegmund, Bayreuth, 1924, 1925 and 1931

Fiorenzo Tasso (1901 - 29. 3. 1976); French tenor as Siegmund, Milan, 1945

Carl Braun (2 June 1886 – 24 April 1960); German bass as Hunding, Bayreuth, 1925, 1927, 1928 and 1930

Lorenz Corvinus (20 July 1870 - 18 January 1952); German bass as Hunding, Bayreuth, 1908

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Die Walküre#The Valkyrie#Richard Wagner#Wagner#Der Ring des Nibelungen#The Ring of the Nibelung#Norse mythology#Völsunga saga#Poetic Edda#Sieglinde#classical musician#classical musicians#classical voice#musician#musicians#music education#music theory#history of music#historian of music#classical

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the difference, if any, between fylgja and hamingja?

I'm still a little messed up in the head from a cold but I'm gonna take a crack at this, just be advised that there's really no way to summarize this in a blog post no matter my cognitive state so I'll just try to get you started by focusing on the problems of differentiation in the border between the two concepts. I'm going to draw heavily from Zuzana Stankovitsova's MA thesis on fylgjur, and if you want to understand the depiction of fylgjur in the sagas I highly recommend you read the whole thing.

This is kind of a constantly ongoing discussion. The problem isn't that there isn't a discernible difference, it's that each one is internally inconsistent, and within those spans of inconsistency, there's some overlap. So you get instances of fylgjur and hamingjur that seem to have hardly anything to do with each other, but then also separately instances of things called fylgja that you'd have expected to be called hamingja, etc. This honestly is very common in Norse literature generally. We expect consistent, distinctive, taxonomic categories but you can't do a DNA test on a norn or an isotope analysis on a dís's fossilized skeleton. But with fylgja the fuzziness might be a little above average even for Norse concepts. It also probably changed over time, within the span of time documented in the sagas.

The crux of the confusion is the fact that while the fylgja most often appears as an animal, sometimes there are scenes in the sagas where a figure in the form of a woman (usually in a dream or vision or some other exceptional, non-normal context) is called fylgja, which resembles what we would expect to be called hamingja. Most scholars have treated animal-fylgjur and woman-fylgjur completely separately.

I'm at least partially inclined to agree with that approach. I think the word fylgja (which just means 'follow') gets thrown around a little much, and that not everything referred to with that word was ever meant to be seen as the same thing. In modern Icelandic the word fylgja can even refer to just a regular ghost that haunts a person (rather than a place, so it follows them from place to place; and an ættarfylgja haunts successive generations of a single family). When fylgjur appear in sagas in the form of human women, they sort of bleed into other categories like hamingjur or dísir and on the extreme end maybe even things the word valkyrja might apply to. If the word fylgja can be applied to any figure that follows a person, then a hamingja is a type of fylgja, just one that is different from the animal-fylgja.

To demonstrate, here are two very similar scenes from two different sagas:

In Hallfreðar saga, Hallfreðr suddenly gets deathly ill. His fylgjukona 'fylgja-woman' appears to him, big and wearing armor, able to walk on the sea as if on land (characteristic of valkyries in Völsunga-related mythology), and Hallfreðr declares that he is formally severing ties with her. Then the woman asks Hallfreðr's son Þorvaldr whether he would like to accept her. He says no, so she asks Hallfreðr's other son, who consents, and she becomes his fylgjukona.

In Víga-Glúms saga, Glúmr dreams of a huge woman, so big that her shoulders take up the entire breadth of valleys, touching mountains on either side. In the dream, he went outside to greet her and bid her welcome into his home. When he woke up, he interpreted this as meaning that his maternal grandfather had died and that his hamingja had come to Glúmr.

I don't personally find it clear whether these are supposed to be the same "type" of being or not. I think the easiest way for someone to try to simplify this would be to say that the author of Hallfreðar saga simply chose confusing wording, and could have said hamingja, or that fylgjukona is not the same as an animal-fylgja. I'm not gonna make that call, as I have no problem with the idea that the evidence really just is confusing and contradictory and I prefer not to give into the impulse to systematize.

Most often, when a figure is described as a fylgja, it's a sort of animal double. They're often deployed in the story to foreshadow death -- an animal representing a main character will be seen in a dream being attacked by other animals representing their enemies. A recurring motif is that people will be suddenly overcome with fatigue in the middle of the day and be unable to help falling asleep, in order to have these extraordinary dreams. People with special abilities, or people in highly unusual situations, may be able to see them without being asleep (I think this only happens once in the literature we have). In rare instances, these visions serve as warnings that enable the relevant people to actually avoid the fate they were headed toward (making it very different from other kinds of knowing the future in Norse literature, which in almost every other case is unavoidable).

The animal fylgja (or other things like it) has a place in later Scandinavian folklore but with all of the change, development, and speculation around it it's not possible to systematize or summarize it; this is a whole continuum of belief and not a single cohesive thing I can summarize. If you're interested in that a good start in English would be Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, edited by Reimund Kvideland and Henning K. Sehmsdorf. It's also very easy to conflate the fylgja with other kinds of animal affinity, like Kveldúlfr becoming a wolf at night or seiðmenn projecting their awareness outside of their bodies in the form of animals, but most scholars have considered this separate and I agree with them.

Despite the fact that hamingja is a little less all over the place, I find it even harder to describe. Usually the word just means 'luck' or 'happiness' in a general sense and doesn't refer to a discrete being or personality, yet the etymology suggests that, at least when the word started being used, it was applied to a specific sort of non-physical being. The word is believed to come from ham-gengja, something which "goes" (ganga) and is of hamr (roughly 'shape' or 'form' but a complicated discussion on its own).

Presumably this has made you have more questions than you started with but hopefully I have at least moved the locus of confusion somewhat.

For some further reading (for convenience, including the ones I already mentioned):

Kvideland, Reimund and Henning K. Sehmsdorf, eds. Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend

Murphy, Luke John "Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age"

Sommer, Bettina Sejbjerg. "The Norse Concept of Luck"

Stankovitsova, Zuzana, "'Eru þetta mannafylgjur?' A Re-Examination of fylgjur in Old Norse Literature" (see also her bibliography)

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theodorik, Tolkien, Volsüngs and Richard Wagner

What do all of these have in common? Well… a couple of things.

Before there was Tolkien’s LOTR and before Richard Wagner wrote Der Ring des Nibelungen there was the Völsunga Saga (13th century), Das Nibelungenlied (13th century) and the Þiðrekssaga (13th century, after older poems).

These tales are part of what is called “Germanic Heroic Myth”. The hero of the story is a literal hero; strong, a good fighter, brave, a good horseman and so on.

Most tales like the ones mentioned above are based on the historical figure of Theodorik of Bern (454-526) an Ostrogoth nobleman and commander in the Eastern Roman army. His Nordic name is Þiðrek (Thidrek).

Tales were invented around his character with him being the literal hero and as inspiration for later heroic saga’s and poems.

Despite their differences, the Völsunga Saga and Das Nibelungenlied centre around the hero Siegfried/Sigurd who (amongst other things) fights Fafner, a dwarf turned into dragon after he gets ownership of a finger ring made from Rhine gold, hoarding a treasure. This ring was forged by the dwarf Andvari/Alberich and cursed by him after it was taken from him. (Starting to sound familiar?)

The tales in essence tell the story of the fall of the Burgundian dynasty told through a Theodorik like figure.

Wagner used many Germanic mythology motives, breaking with the use of classical/classicist tradition in opera. He fantasized further, inventing the Tarnhelm and prioritizing the persona of Wotan (who in my personal opinion is a very weak character in Wagner’s work). Using such Leitmotives throughout 16 hours of opera was unseen.

Tolkien further used these elements, but removes the “one hero element” of these myths. He simplifies the story to one cursed finger ring and a gold hoarding dragon. Tolkien gets rid of the Volsungs, but continues with the Nibelungen/Niflungr as mythical creatures living in the fog alongside humans.

Painting: Theodor Pixis, “Das Rheingold”, oil on canvas laid on masonite, 142x115 cm, private ownership, 1875.

The Rhine maidens lament the stolen gold which Alberich the dwarf holds triumphantly. The price paid for the treasure was to renounce all love. He forges a magical ring out of the gold which he curses after Wotan traps him.

#frankish#merovingian#viking archaeology#archaeology#carolingian#charlemagne#field archaeology#merovingian archaeology#viking mythology#frisian#germanic mythology#norse mythology#vikings#anglo saxon#field archaeologist#viking#germanic#odin#germanic archaeology#germanic folklore#opera#richard wagner#das rheingold#Siegfried#Siegfried opera#tolkien#lord of the rings#lotr#j r r tolkien#bayreuth

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would like to hear about the weasels 👀

two weasels for you:

in völsunga saga, sigmund bites sinfjotli in the throat while they are in their wolf skins doing wolf activities. shortly after, this happens:

“Now on a day he saw where two weasels went, and how that one bit the other in the throat, and then ran straightway into the thicket, and took up a leaf and laid it on the wound, and thereon his fellow sprang up quite and clean whole; so Sigmund went out and saw a raven flying with a blade of that same herb to him; so he took it and drew it over Sinfjotli's hurt, and he straightway sprang up as whole as though he had never been hurt”

magic weasel healing is not confined to this text, either; in marie de france’s lai guildelüec et guilliadun, ou eliduc, there is similar weasel-based herbal medicine. horrible fuckboy eliduc is out doing his thing and falls in love with guilliadun and entirely neglects to tell her the he does, in fact, already have a wife back home. he brings guilliadun back home with him and when she finds out about his wife on the journey back home (because one of the sailors on the ship is like “dude it is bad luck for you to be bringing your girlfriend with you when you have a wife already”), she faints sleeping-beauty style and does not wake up and he puts her in a chapel and keeps it a secret from his wife. while guildelüec, the wife, is visiting the chapel to see what her husband is up to, she sees guilliadun and starts weeping because on the one hand, guilliadun is so pretty, and on the other, her husband sucks. while there, she sees a weasel (girl) that ran over guilliadun’s body get whacked by a servant, and then the weasel’s friend (also a girl) sees her weasel friend laying on the floor as if dead. then the weasel:

“went out of the chapel, / she came to the herbs in the wood; / with her teeth she took a flower / all of a red color. / Quickly she goes back; / she put it in the mouth / of her companion that the servant had killed / in such a way / that at that very moment she came back to life”

and then guildelüec gets the flower and puts it in guilliadun’s mouth and guilliadun comes back to life. then guildelüec becomes a nun so eliduc can marry guilliadun. eliduc then builds a church, becomes a monk, and guilliadun becomes a nun with guildelüec. me personally I like to imagine that guildelüec and guilliadun get up to gay activities after they are freed from awful husband. but there you go. weasel magic!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fantasy read-list: A-2

Fantasy read-list

Part A: Ancient fantasy

2) Mythological fantasy (other mythologies)

Beyond the Greco-Roman mythology, which remained the main source and main influence over European literature for millenia, two other main groups of myths had a huge influence over the later “fantasy” genres.

# On one side, the mythology of Northern Europe (Nordic/Scandinavian, Germanic, but also other ones such as Finnish). When it comes to Norse mythology, two works are the first names that pop-up: the Eddas. Compilations of old legends and mythical poems, they form the main sources of Norse myths. The oldest of the two is the Poetic Edda, or Elder Edda, an ancient compilation of Norse myths and legends in verse. The second Edda is the Prose Edda, so called because it was written in prose by the Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson (alternate names being Snorri’s Edda or the Younger Edda). Sorri Sturluson also wrote numerous other works of great importance, such as Heimskringla (a historical saga depicting the dynasties of Norse kings, starting with tales intermingled with Norse mythology, before growing increasingly “historically-accurate”) or the Ynglinga saga - some also attributed to him the Egil’s Saga.

Other “tales of the North” include, of course, Beowulf, one of the oldest English poems of history, and the most famous version of the old Germanic legend of the hero Beowulf ; the Germanic Völsunga saga and Nibelungenlied ; as well as the Kalevala - which is a bit late, I’ll admit, it was compiled in the 19th century, so it is from a very different time than the other works listed here, but it is the most complete and influential attempt at recreating the old Finnish mythology.

# On the other side, the Celtic mythologies. The two most famous are, of course, the Welsh and the Irish mythologies (the third main branch of Celtic religion, the Gaul mythology, was not recorded in texts).

For Welsh mythology, there is one work to go: the Mabinogion. It is one of the most complete collections of Welsh folktales and legends, and the earliest surviving Welsh prose stories - though a late record feeling the influence of Christianization over the late. It is also one of the earliest appearances of the figure of King Arthur, making it part of the “Matter of Britain”, we’ll talk about later.

For Irish mythology, we have much, MUCH more texts, but hopefully they were already sorted in “series” forming the various “cycles” of Irish mythologies. In order we have: The Mythological Cycle, or Cycle of the Gods. The Book of Invasions, the Battle of Moytura, the Children of Lir and the Wooing of Etain. The Ulster Cycle, mostly told through the epic The Cattle-Raid of Cooley. The Fianna Cycle, or Fenian Cycle, whose most important work would be Tales of the Elders of Ireland. And finally the Kings’ Cycle, with the famous trilogy of The Madness of Suibhne, The Feast of Dun na nGed, and The Battle of Mag Rath.

Another famous Irish tale not part of these old mythological cycles, but still defining the early/medieval Irish literature is The Voyage of Bran.

# While the trio of Greco-Roman, Nordic (Norse/Germanic) and Celtic mythologies were the most influential over the “fantasy literature” as a we know it today, other mythologies should be talked about - due to them either having temporary influences over the history of “supernatural literature” (such as through specific “fashions”), having smaller influences over fantasy works, or being used today to renew the fantasy genre.

The Vedas form the oldest religious texts of Hinduism, and the oldest texts of Sanskrit literature. They are the four sacred books of the early Hinduist religion: the Rigveda, the Yajurveda, the Samaveda and the Atharvaveda. What is very interesting is that the Vedas are tied to what is called the “Vedic Hinduism”, an ancient, old form of Hinduism, which was centered around a pantheon of deities not too dissimilar to the pantheons of the Greeks, Norse or Celts - the Vedas reflect the form of Hinduist religion and mythology that was still close to its “Indo-European” mythology roots, a “cousin religion” to those of European Antiquity. Afterward, there was a big change in Hinduism, leading to the rise of a new form of the religion (usually called Puranic if my memory serves me well), this time focused on the famous trinity of deities we know today: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva.

The classic epics and supernatural novels of China have been a source of inspiration for more Asian-influenced fantasy genres. Heavily influenced and shaped by the various mythologies and religions co-existing in China, they include: the Epic of Darkness, the Investiture of the Gods, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, or What the Master does not Speak of - as well as the most famous of them all, THE great epic of China, Journey to the West. If you want less fictionized, more ancient sources, of course the “Five Classics” of Confucianism should be talked about: Classic of Poetry, Book of Documents, Book of Rites, Book of Changes, as well as Spring and Autumn Annals (though the Classic of Poetry and Book of Documents would be the more interesting one, as they contain more mythological texts and subtones - the Book of Changes is about a divination system, the Book of Rites about religious rites and courtly customs, and the Annals is a historical record). And, of course, let’s not forget to mention the “Four Great Folktales” of China: the Legend of the White Snake, the Butterfly Lovers, the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, as well as Lady Meng Jiang.

# As for Japanese mythology, there are three main sources of information that form the main corpus of legends and stories of Japan. The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), a chronicle in which numerous myths, legends and folktales are collected, and which is considered the oldest literary work of Japan ; the Nihon Shoki, which is one of the oldest chronicles of the history of Japan, and thus a mostly historical document, but which begins with the Japanese creation myths and several Japanese legends found or modified from the Kojiki ; and finally the Fudoki, which are a series of reports of the 8th century that collected the various oral traditions and local legends of each of the Japanese provinces.

# The Mesopotamian mythologies are another group not to be ignored, as they form the oldest piece of literature of history! The legends of Sumer, Akkadia and Babylon can be summed up in a handful of epics and sacred texts - the first of all epics!. You have the three “rival” creation myths: the Atra-Hasis epic for the Akkadians, the Eridu Genesis for the Sumerians and the Enuma Elish story for the Babylonians. And to these three creation myths you should had the two hero-epics of Mesopotamian literature: on one side the story of Adapa and the South Wind, on the other the one and only, most famous of all tales, the Epic of Gilgamesh.

# And of course, this read-list must include... The Bible. Beyond the numerous mythologies of Antiquity with their polytheistic pantheons and complex set of legends, there is one book that is at the root of the European imagination and has influenced so deeply European culture it is intertwined with it... The Bible. European literary works are imbued with Judeo-Christianity, and as such fantasy works are also deeply reflective of Judeo-Christian themes, legends, motifs and characters. So you have on one side the Ancient Testament, the part of the Bible that the Christians have in common with the Jews (though in Judaism the Ancient Testament is called the “Torah”) - the most famous and influential parts of the Ancient Testament/Torah being the first two books, Genesis (the creation myth) and Exodus (the legend of Moses). And on the other side you have the exclusively Christian part of the Bible, the New Testament - with its two most influential parts being the Gospels (the four canonical records of the life of Jesus, the Christ) and The Book of Revelation (the one people tend to know by its flashier name... The Apocalypse).

#read-list#fantasy#fantasy read-list#mythology#mythologies#celtic mythology#norse mythology#japanese mythology#chinese mythology#mesopotamian mythology#books#references#book references#sources

37 notes

·

View notes