#wages for housework

Text

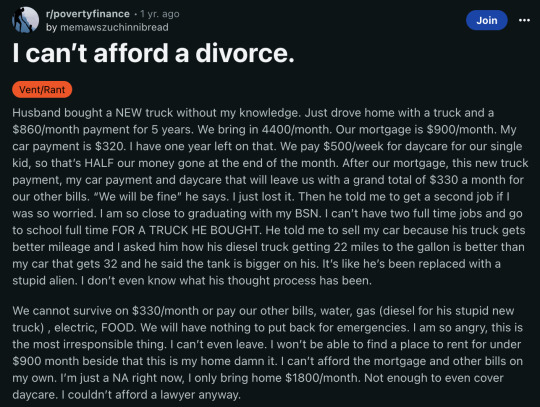

Truck comes first and if there is any money left over the kids may eat. - Modern Consumer Patriarchy

#heterorealism#gender equality#men ain't shit#divorce him#feminism#wages for housework#domestic labor#working class women#blue collar women#fuck the patriarchy

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Wages for housework as a perspective attempts to analyze women's

situation and society as a whole. It attempts feminism in revaluing the contribution women have always made, in demonstrating the essentiality and value of women's most degraded and most universal

functions. In breaking the ideological tie of that work to women's

biology, it attempts to base a claim for a fair share of social product for an activity that almost all women perform, and perform largely for

men. It attempts marxism in grounding its analysis of women's

oppression in the exploitation-the nonvaluing in the political-economic sense--of women's work, in arguing for the contribution of

this work to capital and its expansion. In this way, it grounds an

analysis of women's power in her productive role, not incidentally

changing the definition of production. In so doing, wages for housework makes women's liberation a critical moment in class struggle. At the same time, women's struggle is united with that of all unwaged workers, a new stratum of the exploited found beneath waged slavery. Discussions of wages for housework thus open critical issues of value; labor and its division by sex and sphere; conceptions of the meaning, structure, and inner dynamics of the social order of sex and class; and the sources and strategies for mobilizing political power toward a social transformation that is conceived as total."

Catharine Mackinnon, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love as women's work

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Waitresses Action Committee [WAC]’s success in garnering public support was evident in the letters of protest sent to the Minister of Labour and the Minister of Industry and Tourism. Thoughtful and sometimes extensive, these letters described women’s structural disadvantages in the workforce as well as the inherent unfairness of the [wage] differential. A mere $2.65 an hour was “scarcely enough to live on,” wrote the Christian Resource Centre, while the YWCA pointed out that women in general made 55 per cent of a male wage, and there already was a “differential” in the restaurant industry as women were relegated to lower-wage venues. The Law Union of Ontario laid out a long list of objections, including the fact that a tip differential would further disadvantage workers who were seldom unionized and thus some of the most economically vulnerable – those who “can least afford it.” Moreover, the differential would set a dangerous precedent for other business lobbies. Some letters to the Minister of Labour came from natural allies: two NDP riding associations, Times Change Women’s Employment Service, and the Northern Women’s Centre and Women’s Resource Centre in Thunder Bay and Timmins, respectively. Others indicated the WAC’s persuasive ability to reach out to less obvious supporters, such as the Business and Professional Women’s Club of Fort Frances, which endorsed the brief. So too did the Thunder Bay city council.

Waitresses also responded individually with calls and letters to the WAC. These were not simply the result of the WAC’s smart communication skills. Waitresses were angry. What the WAC outlined – uncertain employment, wage theft, sexualization, “hustling” for a tip – applied everywhere, and women had had enough. They wanted copies of the brief, the petition, information on what they could do, or simply to vent their unhappiness with wages and working conditions. A few wrote directly to Labour Minister Bette Stephenson. The “work is no joy,” wrote one Thunder Bay waitress at a licenced steakhouse; it entailed constant stress from uncertain pay, fear of losing the job, and “boorish [customer] behaviour” that “drove her to tears…. Something happens to people when they are hungry,” she concluded. “They become less than human.” A former waitress who had worked in other countries, even as a maître d’, identified exploitation as transnational: “It has always been a slave trade, with the poorest working conditions, paying the lowest wages.”

As the government dug in its heels on the differential in 1978, a Kitchener waitress blasted Stephenson. The government policy was “sexist” since it discriminated against most women at “less classy establishments,” and it ignored all waitresses’ unpaid labour. In her job, she filled in for other workers; as a result, only 50 per cent of the time was she even able to get tips. The government also ignored the health hazards of the job, including noisy, smoky bars where waitresses “risked being injured in fights between customers.” Some waitresses, she wrote, spent their paltry “nickels and dimes” tips on taxis to get home late at night. She identified the true culprit – the tourist industry, demanding small savings “on the backs of the hired help” – and suggested that the business lobby’s comparisons with American wages was “unfair to Canadian workers.” She ended with a comparison the WAC also made in its publicity: “I find it ironic,” she wrote, that “well paid” government officials, who voted on their own pay increases, were depriving waitresses of “25 to 50 cents” an hour.

Finger pointing about the class interests of the government were apparent in other protest letters. “We need an equitable incomes policy, not one that decreases the earnings of working people in lower economic brackets,” wrote a woman from West Hill. “I wonder when the government will treat working people as well as they do [those] in the upper middle class.” Others implied that the Tories, eating at “high class” establishments, naturally did not understand the issue, while one letter offered a sarcastic take on Premier Davis’ recent election slogan: “Davis for all the people – well, just not waitresses.”

- Joan Sangster, “Waitresses in Action: Feminist Labour Protest in 1970s Ontario,” Labour/Le Travail 92 (Fall 2023), p. 34-36.

#waitresses action committee#wages for housework#wages due lesbians#union organizing#tipping#waitresses#service workers#minimum wage#union activists#capitalism#marxist feminism#social wage#working class struggle#anti patriarchy#anti-capitalism#academic quote#toronto#working class feminism#kitchener#thunder bay#timmins#reading 2024#joan sangster

1 note

·

View note

Photo

(via Eat the Rich Working Class Minimum Wage Social Progressive - Etsy)

1 note

·

View note

Text

wages for housework is always, to me, going to be THEE funniest 'feminist' talking point

state mandated housewife who gets paid to be a NEET, as long as she cleans after some man ? i can't see how that would be a disaster socially.

#i have so many questions#what about singles living alone. do they get the housespouse wage too to top up their work rage?#could they get the housework wage and live off of it without doing any socially productive work?#what if the housewife wage is higher than women's wages on the actual job market?#such a disaster of an idea from every angle

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

smth kind of irks me when people respond to ‘not all men’ like “when we say xyz about the patriarchy/male privilege we OBVIOUSLY don’t mean all men we mean on a structural level<33″ because its like......well who makes up + maintains that structure?? if he’s not devoting serious amounts of his existence to combating it, you can bet he’s benefitting from + reinforcing it! even IF he’s nice to you! ur bfs and ur dads and ur brothers etc are all profiting from your exploitation and you can like them as people and even recognise them as also victims in this machine but nothing is going to change until we can freely acknowledge that the very fact that it’s structural means that mass support is necessary to its continued survival, like we canttttt keep holding ur hand when we tell u that 😭

#i think the recent surge in misogynistic trans guys really proves that like. if he thinks he can get it hes going to take it#its NOT ignorance its literally a measured choice bc it benefits them#they have to be prepared to sacrifice those benefits and so many like perfectly 'nice' men just arent#like is he doing 50%+ of housework and childcare?#would he donate the 20%+ of his salary skimmed off the top of women's wages#would he explicitly contradict a sexist narrative that cropped up around a woman he disagreed with if it benefitted his credibility#etc etc ad infinitum

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The question of the land overwhelmingly forced us to rethink that of reproduction: the reproduction of humanity as a whole, if we want to think in global terms. In industrialized countries reproduction happens essentially through the work of managing money, not the money of its own retribution, which was never granted, but the money coming from the husband’s paycheck or, in more post-Fordist terms, from the two precarious paychecks of his and her jobs outside of the home. In Third World countries, on the other hand (and they remain Third World even when they enter the First World or vice versa), reproduction happens first of all through the work in the fields. In other words, through farming for sustenance or local consumption, according to a system of collective ownership or small property.

In order to appreciate this issue in all its seriousness, both regarding the privatization and the exploitation and destruction of the reproductive powers of land, we need to reconsider what happened during the 80s. While there’s no doubt that those were years of repression and normalization in Italy, in Third World countries those were the years of the draconian adjustment dictated by the IMF. The adjustment involved all countries, Italy included, but in Third World countries, it called for particularly draconian measures. For instance the cuts to subsidized staple foods, and most importantly, the strong recommendation to put a price on land, thus privatizing it wherever it was still a commons (as it was for most of Africa), basically making subsistence agriculture impossible. This measure (made even more dramatic in those years in the context of other typical IMF adjustments) represents, in my opinion, the major cause of world hunger, and it creates the illusion of overpopulation, while the real problem is that of landlessness. As the implementation of the adjustment policies of the 80s became more severe, reproduction regressed at a global level. This was the preparatory phase of neoliberalism. In fact, creating poorer living conditions and fewer life expectations and a level of poverty without precedent, it provided the prerequisites for the launch of the new globalized economy: for the deployment of neoliberalism worldwide, requiring workers to sacrifice so that corporations can compete on the global market; for the endorsement of new models of productivity with smaller salaries and deregulated working conditions; for the stabilization of an international hierarchy of workers with an ever larger and more dramatic gap, both in the fields of production and reproduction. Starting in the 80s, the wave of suicides among farmers in India reached 20,000 cases in the last three years. All of them couldn’t pay back the debts they had incurred to buy seeds and pesticides. A genocide!

As mass suicides give us the measure of the amount of hunger and death brought upon people by the Green Revolution and by IMF policies, the 80s were also the years that saw the rise of struggles against these policies (from South America to Africa and Asia), against the expropriation and poisoning of the land, against the distortion and the destruction of its reproductive powers. The protagonists of these struggles created networks, organizations, and movements that we found again in the 90s as components of the big anti-globalization movement, which was called, not accidentally “the movement of movements.” The first moment of unification of these different entities, and with it, the launch of the anti-globalization movement, happened at the end of July and beginning of August ‘96 in Chiapas, when the Zapatistas called for an Intercontinental meeting for “humanity against neoliberalism.” The central demand in the Zapatistas’ insurrection was that of land.

Mariarosa Dalla Costa, "The Door to the Flower and the Vegetable Garden"

#the translation seems odd in a couple places but I think 'the money of its own retribution' might mean the value#that women doing housework creates that was never granted to them in the form of a wage#neoliberalism#Mariarosa Dalla Costa#quote#readings#colonialism#neocolonialism

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

god I've had a real weird week. I finished my BA in April and haven't managed to muster up the courage and energy to go job hunting since then, and have just fallen deeper and deeper into a depressive episode with each passing day. and then on wednesday evening my dentist (also a neighbour and friend of my family) suddenly called me because her receptionist quit out of the blue so she urgently needs a replacement and asked me if I'd like the job. so I went back to my parents' town today, met up with her after dinner to talk and then we went to her practice and she showed me the general gist of what I'd need to do. and now I'm gonna move back in with my parents and start working for her full-time in just over a week.

#gotta love working a barely over minimum wage job as a receptionist when I have a BA in computer science#and a mild-moderate phobia of strangers and phone calls#but my mental health won't let me do any job hunting so I had to say yes when i got offered a job on a silver platter#even if it's just temporary it'll probably help me get back on my feet and sort out my brain until i feel good enough to find a CS job#and living with my parents for a while is probably gonna be very beneficial too#when my roommate is gone and I'm home alone I just get so down that I can't do any housework and barely eat anything for days on end#so at least when I'm with my parents they'll make sure I eat somewhat properly and won't let me get away without doing any chores#but yeah it's been a weird few days and it's probably gonna be a few weird months while I work there#irl bullshit#cw ed mention#kinda?#it's not really an ed i think i just don't have the energy to feed myself properly most days

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regarding the wages for housework idea, I feel a lot of the problems with it are men not being penalized for their wives staying home. If either option had drawbacks wouldn't that solve it? Would it be preferable if instead of being paid for by the government, these 'wages' were paid out of the working partners wages or their workplace would have to pay an additional stipend to a dependent partner? This would not be employment, just a no strings payment, so there would be no employee/employer power dynamic.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#emotional labor#weaponized incompetence#divorced dads#divorce him#mental load#feminism#wages for housework#gender inequality

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wages Against

Housework

Silvia Federici, 1974

They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.

They call it frigidity. We call it absenteeism.

Every miscarriage is a work accident.

Homosexuality and heterosexuality are both

working conditions. . . but homosexuality is

workers’ control of production, not the end of

work.

More smiles? More money. Nothing will be so

powerful in destroying the healing virtues of a

smile.

Neuroses, suicides, desexualization: occupational diseases of the housewife.

0 notes

Text

As I keep shouting into the void, pathologizers love shifting discussion about material conditions into discussion about emotional states.

I rant approximately once a week about how the brain maturity myth transmuted “Young adults are too poor to move out of their parents’ homes or have children of their own” into “Young adults are too emotionally and neurologically immature to move out of their parents’ homes or have children of their own.”

I’ve also talked about the misuse of “enabling” and “trauma” and “dopamine” .

And this is a pattern – people coin terms and concepts to describe material problems, and pathologization culture shifts them to be about problems in the brain or psyche of the person experiencing them. Now we’re talking about neurochemicals, frontal lobes, and self-esteem instead of talking about wages, wealth distribution, and civil rights. Now we can say that poor, oppressed, and exploited people are suffering from a neurological/emotional defect that makes them not know what’s best for themselves, so they don’t need or deserve rights or money.

Here are some terms that have been so horribly misused by mental health culture that we’ve almost entirely forgotten that they were originally materialist critiques.

Codependency

What it originally referred to: A non-addicted person being overly “helpful” to an addicted partner or relative, often out of financial desperation. For example: Making sure your alcoholic husband gets to work in the morning (even though he’s an adult who should be responsible for himself) because if he loses his job, you’ll lose your home. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/08/opinion/codependency-addiction-recovery.html

What it’s been distorted into: Being “clingy,” being “too emotionally needy,” wanting things like affection and quality time from a partner. A way of pathologizing people, especially young women, for wanting things like love and commitment in a romantic relationship.

Compulsory Heterosexuality

What it originally referred to: In the 1980 in essay "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence," https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/493756 Adrienne Rich described compulsory heterosexuality as a set of social conditions that coerce women into heterosexual relationships and prioritize those relationships over relationships between women (both romantic and platonic). She also defines “lesbian” much more broadly than current discourse does, encompassing a wide variety of romantic and platonic relationships between women. While she does suggest that women who identify as heterosexual might be doing so out of unquestioned social norms, this is not the primary point she’s making.

What it’s been distorted into: The patronizing, biphobic idea that lesbians somehow falsely believe themselves to be attracted to men. Part of the overall “Women don’t really know what they want or what’s good for them” theme of contemporary discourse.

Emotional Labor

What it originally referred to: The implicit or explicit requirement that workers (especially women workers, especially workers in female-dominated “pink collar” jobs, especially tipped workers) perform emotional intimacy with customers, coworkers, and bosses above and beyond the actual job being done. Having to smile, be “friendly,” flirt, give the impression of genuine caring, politely accept harassment, etc.

https://weld.la.psu.edu/what-is-emotional-labor/

What it’s been distorted into: Everything under the sun. Everything from housework (which we already had a term for), to tolerating the existence of disabled people, to just caring about friends the way friends do. The original intent of the concept was “It’s unreasonable to expect your waitress to care about your problems, because she’s not really your friend,” not “It’s unreasonable to expect your actual friends to care about your problems unless you pay them, because that’s emotional labor,” and certainly not “Disabled people shouldn’t be allowed to be visibly disabled in public, because witnessing a disabled person is emotional labor.” Anything that causes a person emotional distress, even if that emotional distress is rooted in the distress-haver’s bigotry (Many nominally progressive people who would rightfully reject the bigoted logic of “Seeing gay or interracial couples upsets me, which is emotional labor, so they shouldn’t be allowed to exist in public” fully accept the bigoted logic of “Seeing disabled or poor people upsets me, which is emotional labor, so they shouldn’t be allowed to exist in public”).

Battered Wife Syndrome

What it originally referred to: The all-encompassing trauma and fear of escalating violence experienced by people suffering ongoing domestic abuse, sometimes resulting in the abuse victim using necessary violence in self-defense. Because domestic abuse often escalates, often to murder, this fear is entirely rational and justified. This is the reasonable, justified belief that someone who beats you, stalks you, and threatens to kill you may actually kill you.

What it’s been distorted into: Like so many of these other items, the idea that women (in this case, women who are victims of domestic violence) don’t know what’s best for themselves. I debated including this one, because “syndrome” was a wrongful framing from the beginning – a justified and rational fear of escalating violence in a situation in which escalating violence is occurring is not a “syndrome.” But the original meaning at least partially acknowledged the material conditions of escalating violence.

I’m not saying the original meanings of these terms are ones I necessarily agree with – as a cognitive liberty absolutist, I’m unsurprisingly not that enamored of either second-wave feminism or 1970s addiction discourse. And as much as I dislike what “emotional labor” has become, I accept that “Women are unfairly expected to care about other people’s feelings more than men are” is a true statement.

What I am saying is that all of these terms originally, at least partly, took material conditions into account in their usage. Subsequent usage has entirely stripped the materialist critique and fully replaced it with emotional pathologization, specifically of women. Acknowledgement that women have their choices constrained by poverty, violence, and oppression has been replaced with the idea that women don’t know what’s best for themselves and need to be coercively “helped” for their own good. Acknowledgement that working-class women experience a gender-and-class-specific form of economic exploitation has been rebranded as yet another variation of “Disabled people are burdensome for wanting to exist.”

Over and over, materialist critiques are reframed as emotional or cognitive defects of marginalized people. The next time you hear a superficially sympathetic (but actually pathologizing) argument for “Marginalized people make bad choices because…” consider stopping and asking: “Wait, who are we to assume that this person’s choices are ‘bad’? And if they are, is there something about their material conditions that constrains their options or makes the ‘bad’ choice the best available option?”

#mad pride#neurodiversity#ableism#ageism#youth rights#liberation#disability rights#classism#capitalism#mental health culture#pop psychology#feminism#emotional labor

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

[“People are attracted to the concept of a Nordic-style law that criminalises only the sex buyer, and not the prostitute – but any campaign or policy that aims to reduce business for sex workers will force them to absorb the deficit, whether in their wallets or in their working conditions. As a sex worker in the Industrial Workers of the World observes,

I find that how easy, safe, and enjoyable I can make my work is directly related to whether I can survive on what I’m currently making … I might be safer if I refused any clients who make their disrespect for me clear immediately, but I know exactly where I can afford to set the bar on what I need to tolerate. If I haven’t been paid in weeks, I need to accept clients who sound more dangerous than I’d usually be willing to risk.

When sex workers speak to this, we are often seemingly misheard as defending some kind of ‘right’ for men to pay for sex. In fact, as Wages For Housework articulated in the 1970s, naming something as work is a crucial first step in refusing to do it – on your own terms. Marxist-feminist theorist Silvia Federici wrote in 1975 that ‘to demand wages for housework does not mean to say that if we are paid we will continue to do it. It means precisely the opposite. To say that we want money for housework is the first step towards refusing to do it, because the demand for a wage makes our work visible, which is the most indispensable condition to begin to struggle against it.’ Naming work as work has been a key feminist strategy beyond Wages For Housework. From sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s term ‘emotional labour’, to journalist Susan Maushart’s term ‘wife-work’, to Sophie Lewis’s theorising around surrogacy and ‘gestational labour’, naming otherwise invisible or ‘natural’ structures of gendered labour is central to beginning to think about how, collectively, to resist or reorder such work.

Just because a job is bad does not mean it’s not a ‘real job’. When sex workers assert that sex work is work, we are saying that we need rights. We are not saying that work is good or fun, or even harmless, nor that it has fundamental value. Likewise, situating what we do within a workers’ rights framework does not constitute an unconditional endorsement of work itself. It is not an endorsement of capitalism or of a bigger, more profitable sex industry. ‘People think the point of our organisation is [to] expand prostitution in Bolivia’, says ONAEM activist Yuly Perez. ‘In fact, we want the opposite. Our ideal world is one free of the economic desperation that forces women into this business.’

It is not the task of sex workers to apologise for what prostitution is. Sex workers should not have to defend the sex industry to argue that we deserve the ability to earn a living without punishment. People should not have to demonstrate that their work has intrinsic value to society to deserve safety at work. Moving towards a better society – one in which more people’s work does have wider value, one in which resources are shared on the basis of need – cannot come about through criminalisation. Nor can it come about through treating marginalised people’s material needs and survival strategies as trivial. Sex workers ask to be credited with the capacity to struggle with work – even to hate it – and still be considered workers. You don’t have to like your job to want to keep it.”]

molly smith, juno mac, from revolting prostitutes: the fight for sex workers’ rights, 2018

923 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The strategies developed by the Waitresses Action Committee [WAC] were shaped by their astute analysis of the structural limitations on reaching a scattered and transient workforce that included many women who worked part time. A substantial group of “older” women, in their 30s and 40s, also had family responsibilities. The labour law regime, based on union locals representing a workplace or a group within a workplace, was not conducive to organizing; however, the WAC eschewed worksite organization for an occupational mobilization outside of the existing union structures. One problem, the WAC conceded in a letter to a Kingston waitress, was that waitressing was often a “filler” job for women between other jobs or in hard times, so “once a waitress, you are not always a waitress.” Even if women continued to do the job, they might move from one locale to another. Recognizing “how dangerous and difficult” it was to organize at the workplace, as well as women’s reluctance or inability to attend meetings that clashed with child care, the WAC developed alternative tactics: petitions, publicity, lobbying, and alliances with politicians, feminists, and a very wide array of social movements. “We never intended to make a big membership drive,” [Ellen] Agger wrote to a waitress in Waterloo near the end of the campaign; the WAC’s tactics reflected “who we are in ways that would reflect our own lack of time.”

The small Wages For Housework (WFH) and WAC instigating group tried to locate grassroots waitress supporters and raise public awareness, as well as secure endorsements from organizations to emphasize the breadth and interconnections of this workplace issue. They did not focus only on obvious allies; they approached Lynne Gordon, head of the ACSW, and Laura Sabia, a Tory, as well as more progressive groups. By 1977, the WAC’s list of supporters protesting the differential included legal reform groups and immigrant, feminist, lesbian, antipoverty, educational, social service, and labour organizations; they accrued 33 official endorsements. Given the WAC’s small numbers, this outreach was nothing short of astounding.

Most responses to the WAC indicated a shared concern about the ongoing economic fallout of cuts, inflation, and declining wages in women’s lives. The combined class and feminist message of the WAC appealed; a local antipoverty group offered its immediate support, promising to write to the government and noting that the issue spoke to “sole support moms,” likely because some women with dependents moved in and out of waitressing to try to make ends meet.

The class message was less appealing to some groups, including the politically cautious Ontario ACSW; it took a long time to create a lukewarm resolution of support. If an organization refused to endorse, as did CHAT (Community Homophile Association of Toronto), Agger followed up with further persuasion. If she encountered politicians gladhanding in public spaces, as she did with both NDP leader Stephen Lewis and Conservative Larry Grossman at the Bathurst Street United Church festival in the summer of 1977, she queried them on their views on the differential and waitresses’ wages.

The WAC worked the phones to raise public awareness, but it also circulated its brief, originally written for the provincial Department of Labour and Department of Industry and Tourism early in 1977. Any inquiry the committee got, out went the brief and the petition, titled “Money for Waitresses Is Money for All Women.” The brief was a tightly organized, well-argued, and convincing document that earned the WAC respect. A seven-page analysis, it covered a history of the tip differential, including the strong business lobby behind it, and the biased nature of that lobby’s selective comparative statistics drawn from other regions and the United States. It also exposed a secretive provincial government unwilling to publicly acknowledge what it was planning vis-à-vis the minimum wage.

The brief held that the tipping system should not be considered a wage but rather a payment for service that might or might not be paid, and it noted that tips subsidized employers, not workers, since they allowed owners to pay low wages – something Ministry of Labour researchers privately said too. Those hurt most by a growing differential, it showed, were those at the bottom of the workplace hierarchy in hospitality – women, sole support mothers, immigrants. Most waitresses made close to (if not only) the minimum wage; a

statistical appendix showed the wage gap between male and female workers in general and food servers in particular. Women and men were rewarded differently for their work, in part because of the gendered hierarchy of service labour, with men working in more prestigious locales, but wage differences were still striking. Although women made up the majority of the workforce, they earned at least a third less than men in the same job. Waitresses who had to support dependents, the WAC brief showed, were poised close to or below the poverty line.

Agger quoted waitresses interviewed in the press who pointed out that their wages were supporting families and that, even with tips, the money they earned “barely kept the wolves from the door.” The brief asked why waitressing was deemed a (low) minimum-wage job, and here, the views of WFH were clear: serving was considered women’s work that required no training, as it was an extension of their work in the home. Many women, moreover, took up waitressing as their only alternative to “wagelessness in the home.” Just as women in the home provide “cheap labour,” so did women and immigrants in serving jobs, with the latter always “with the gun of poverty to their heads."

- Joan Sangster, “Waitresses in Action: Feminist Labour Protest in 1970s Ontario,” Labour/Le Travail 92 (Fall 2023), p. 29-31.

#waitresses action committee#wages for housework#union organizing#tipping#waitresses#service workers#minimum wage#union activists#capitalism#marxist feminism#social wage#working class struggle#anti patriarchy#anti-capitalism#academic quote#toronto#joan sangster#working class feminism#reading 2024

0 notes

Text

Why women presented as men, in their own words

Most of these working-class women appear to have begun their "masculine" careers not because they had an overwhelming passion for another woman and wanted to be a man to her, but rather because of economic necessity or a desire for adventure beyond the narrow limits that they could enjoy as women. But once the sexologists became aware of them, they often took such women or those who showed any discontent whatsoever with their sex roles for their newly conceptualized model of the invert, since they had little difficulty believing in the sexuality of women of that class, and they assumed that a masculine-looking creature must also have a masculine sex instinct.

Autobiographical accounts of transvestite women or those who assumed a masculine demeanor suggest, if they can be believed at all, that the women's primary motives were seldom sexual. Many of them were simply dramatizing vividly the frustrations that so many more women of their class felt. They sought private solutions to those frustrations, since there was no social movement of equality for them such as had emerged for middle-class women. Lucy Ann Lobdell, for example, who passed as a man for more than ten years in the mid-nineteenth century, declared in her autobiography: "I feel that I cannot submit to all the bondage with which woman is oppressed," and explained that she made up her mind to leave her home and dress as a man to seek labor because she would "work harder at housework, and only get a dollar per week, and I was capable of doing men's work and getting men's wages." "Charles Warner," an upstate New York woman who passed as a man for most of her life, explained that in the 1860s:

“When I was about twenty I decided that I was almost at the end of my rope. I had no money and a woman's wages were not enough to keep me alive. I looked around and saw men getting more money and more work, and more money for the same kind of work. I decided to become a man. It was simple. I just put on men's clothing and applied for a man's job. I got it and got good money for those times, so I stuck to it”

A transvestite woman who could actually pass as a man had male privileges and could do all manner of things other women could not: open a bank account, write checks, own property, go anywhere[…]

Ralph Kerwinieo (nee Cora Anderson), an American Indian woman who found employment for years as a man and claimed that she "legally" married another woman in order to "protect" her from the sexist world, also expressed feminist awareness for her decision to pass as a man:

“This world is made by man—for man alone.... In the future centuries it is probable that woman will be the owner of her own body and the custodian of her own soul. But until that time you can expect that the statutes [concerning] women will be all wrong. The well-cared for woman is a parasite, and the woman who must work is a slave.... Do you blame me for wanting to be a man-free to live as a man in a man-made world? Do you blame me for hating to again resume a woman's clothes?”

There must have been many women, with or without a sexual interest in other women, who would have answered her two questions with a resounding "no!"

From “Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers.” The economic reason for women to pass as men is almost never mentioned, funny that!

#mypost#radical feminism#lesbian women#bookcitation#the more things seem to change#gnc women#100 notes tag

114 notes

·

View notes