#walter blythe

Text

Walter Blythe & Gilbert Blythe

"He patted Walter's head and Walter caught his hand and hugged it. There was no one like Dad in the world."

(Anne of Ingleside by L. M. Montgomery).

"People said he had never been the same since his son was killed in the Great War."

"...we have our memories of him and souls cannot die. We can still walk with Walter in the spring."

(The Blythes Are Quoted by L. M. Montgomery)

I look for you in every star.

#lm montgomery#anne of green gables#rilla of ingleside#gilbert blythe#walter blythe#father&son#moodboard

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

so @shirleyjblythe posted a super fun poll to guess Shirley's middle name so of course I decided to research all the Blythe children's names bc apparently I don't know what to do with myself until school starts again!! give them a follow bc I am HERE for the Shirley appreciation

Joyce Blythe (deceased) is the only Blythe child not named for someone else. Anne wanted to call her Joy bc she was overjoyed at having a baby.

ok so Jem is actually James Matthew Blythe but they call him Jem (after Captain Jim and Matthew, in House of Dreams Anne says they were the two best men she knew outside of Gil)

Walter is apparently the next oldest, which I never put together - he is older than the twins. He is Walter Cuthbert Blythe in honor of Matthew and Marilla, and the Walter is in honor of Anne's father, Walter Shirley, who died shortly after her birth.

The twins are Anne and Diana (Nan and Di for short) after Anne and Diana of course. We don't learn their middle names.

Shirley is named after Anne's parents (Walter and Bertha Shirley) but we don't learn his middle name. Maybe something for Gil's side of the family?

Rilla is Betha Marilla Blythe, after Anne's birth mother (Bertha Shirley) and adoptive mother (Marilla Cuthbert)

#the blythe children#shirley blythe#walter blythe#anne blythe#diana blythe#jem blythe#anne of green gables#anne shirley#anne's house of dreams#anne of the island#rilla of ingleside#anne of ingleside#gilbert blythe#avonlea#anne with an e#lucy maud montgomery

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Have My Attention: Anne of Green Gables First Lines

The icon of Canadian girlhood needs no introduction, as Anne of Green Gables is a global phenomenon at this point. What those of you who read the first book at like age ten and then didn't bother exploring further might not know, however, is that LM Montgomery wrote a whole Anne series. So how did she catch a reader's attention? Let's find out!

"Mrs. Rachel Lynde lived just where the Avonlea main road dipped down into a little hollow, fringed with alders and ladies’ eardrops and traversed by a brook that had its source away back in the woods of the old Cuthbert place; it was reputed to be an intricate, headlong brook in its earlier course through those woods, with dark secrets of pool and cascade; but by the time it reached Lynde’s Hollow it was a quiet, well-conducted little stream, for not even a brook could run past Mrs. Rachel Lynde’s door without due regard for decency and decorum; it probably was conscious that Mrs. Rachel was sitting at her window, keeping a sharp eye on everything that passed, from brooks and children up, and that if she noticed anything odd or out of place she would never rest until she had ferreted out the whys and wherefores thereof."

-- Anne of Green Gables

"A tall, slim girl, 'half-past sixteen,' with serious gray eyes and hair which her friends called auburn, had sat down on the broad red sandstone doorstep of a Prince Edward Island farmhouse one ripe afternoon in August, firmly resolved to construe so many lines of Virgil."

-- Anne of Avonlea

"'Harvest is ended and summer is gone,' quoted Anne Shirley, gazing across the shorn fields dreamily."

-- Anne of the Island

"(Letter from Anne Shirley, B.A., Principal of Summerside High School, to Gilbert Blythe, medical student at Redmond College, Kingsport.)

Windy Poplars,

Spook's Lane,

S'side, P. E. I.,

Monday, September 12th.

DEAREST:

Isn't that an address!"

-- Anne of the Windy Poplars

"'Thanks be, I’m done with geometry, learning or teaching it,' said Anne Shirley, a trifle vindictively, as she thumped a somewhat battered volume of Euclid into a big chest of books, banged the lid in triumph, and sat down upon it, looking at Diana Wright across the Green Gables garret, with gray eyes that were like a morning sky."

-- Anne's House of Dreams

"'How white the moonlight is tonight!' said Anne Blythe to herself, as she went up the walk of the Wright garden to Diana Wright's front door, where little cherry-blossom petals were coming down on the salty, breeze-stirred air."

-- Anne of Ingleside

"It was a clear, apple-green evening in May, and Four Winds Harbour was mirroring back the clouds of the golden west between its softly dark shores. The sea moaned eerily on the sand-bar, sorrowful even in spring, but a sly, jovial wind came piping down the red harbour road along which Miss Cornelia’s comfortable, matronly figure was making its way towards the village of Glen St. Mary."

-- Rainbow Valley

"It was a warm, golden-cloudy, lovable afternoon. In the big living-room at Ingleside Susan Baker sat down with a certain grim satisfaction hovering about her like an aura; it was four o'clock and Susan, who had been working incessantly since six that morning, felt that she had fairly earned an hour of repose and gossip."

-- Rilla of Ingleside

#lm montgomery#anne of green gables#anne of avonlea#anne of the island#anne of the windy poplars#anne's house of dreams#anne of ingleside#rainbow valley#rilla of ingleside#anne shirley#gilbert blythe#diana barry#marilla cuthbert#matthew cuthbert#rilla blythe#walter blythe#canadian literature#children's books#children's literature#girlhood#books and reading#books & libraries#books and novels#books#book recommendations

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

l.m. montgomery - the sea-shell

cannot exactly remember when or how, but at some point i was googling and found out from LMM Online that a line ken quotes to rilla ("a merry lilt o' moonlight for mermaiden revelry"), which is attributed to one of walter's poems, was in fact from another poem LMM wrote. said poem was not in TBAQ and i was too lazy to hunt down the collection it was actually published in, but tripped over it today. so technically this poem can be attributed to walter too, if you want to think of it that way

#anne of green gables#rilla of ingleside#walter blythe#had to look up Just One Thing last night#went down a rabbit hole as u do

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

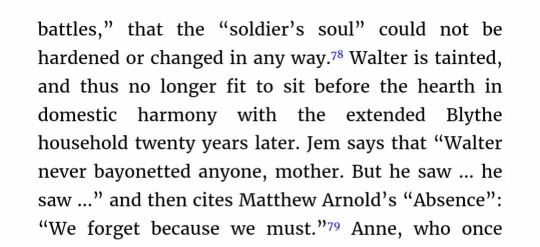

Violence and Walter

I've been reading LM Montgomery and Gender, and although I'm only a few essays in, there have been a couple on Walter that have blown my mind. Specifically, their commentary on Walter's relationship to violence has split my brain open. They've begun to answer a question I've had for a while: why did LM Montgomery have Walter so savagely beat Dan Reese?

Let's be real here, the general image of Walter is someone who is milk-soppish. In a way, he shares some similarities with Robin Stuart, although he decidedly has more backbone. However, he still has that delicate, sensitive imagery surrounding him that follows him throughout the books. We have all the passages that are probably familiar if you've been following me for a while: Gilbert describes him as being afraid to go upstairs in the dark, many people mock him for being sensitive, and the overall impression is that he's thought of is being shy, retiring, and girly.

This stands in stark contrast to the scene where he fights Dan Reese. Exhibit:

Walter reeled a little. The pain of the blow tingled through all his sensitive frame for a moment. Then he felt pain no longer. Something, such as he had never experienced before, seemed to roll over him like a flood. His face flushed crimson, his eyes burned like flame. The scholars of Glen St. Mary school had never dreamed that “Miss Walter” could look like that. He hurled himself forward and closed with Dan like a young wildcat.

There were no particular rules in the fights of the Glen school boys. It was catch-as-catch can, and get your blows in anyhow. Walter fought with a savage fury and a joy in the struggle against which Dan could not hold his ground. It was all over very speedily. Walter had no clear consciousness of what he was doing until suddenly the red mist cleared from his sight and he found himself kneeling on the body of the prostrate Dan whose nose—oh, horror!—was spouting blood.

[...]

There was a loud clapping from the boys who were perched on the rail fence, but some of the girls were crying. They were frightened. They had seen schoolboy fights before, but nothing like Walter as he had grappled with Dan. There had been something terrifying about him. They thought he would kill Dan. Now that all was over they sobbed hysterically—except Faith, who still stood tense and crimson cheeked.

This isn't the skittish, highstrung Walter we know. This is deliberately emphasizing Walter's savagery. The language here is not one that speaks to justice being served. Walter isn't being presented as an avenging force for justice; Walter is being presented as an animal. He's fully carried away by a blunt brutality arising from base instinct. More that that: he's enjoying it.

Epperly's book The Fragrance of Sweet Grass provided me with some preliminary answers. According to her, this entire passage is an allegory for WWI. And ah ha, that makes so much sense. Walter, fighting against forces of evil, losing himself in the brutality and bloodshed. As Epperly states:

However, even Epperly questions Montgomery's use of Walter's savagery. She attributes it to a brief commentary on vengeance within the framework of Walter as the gallant knight (it's cut off, but this paragraph begins with "Interestingly..." on the previous page of the book):

So we have some answers here - the allegory is obvious, especially in the context of WWI - but there's an essay in the gender book that has some really interesting explorations into Walter's frame of mind that I want to poke at (From "Uncanny Beauty" to "Uncanny Disease": Destabilizing Gender through the Deaths of Ruby Gillis and Walter Blythe and the Life of Anne Shirley by Lesley Clement).

Clement more fully leans into the savagery of Walter, to the point of claiming that the Jekyll and Hyde cat could be seen as a parallel for Walter's two sides. In their analysis of Walter's arc, they see possibilities for (1) Walter having a death wish, and (2) Walter suffering from shell shock, even as he writes that letter to Rilla.

LM Montgomery's portrayal of Walter's heroism takes on a very different light here. It's a sort of double-vision: Walter wasn't scared of realities, only of his imagination; Walter, in the end, was the bravest of them all; but also - Walter wanted to die on the front. This could even be seen as tacitly confirmed by his message to Rilla that he couldn't live after what he'd seen. His immunity to fear on the front can be seen as both a personal triumph that ends his arc, and a suicidal shell shock.

Walter's death wish could arguably also be seen in the aftermath, the last poem he ever wrote - and the last story every written in the AOGG series:

The Aftermath carries multiple possible meanings. Walter could be remembering killing a teen boy, he could be recalling what he'd seen, or, as stated here: he could be reflecting on his own death. Overall, in Clement's opinion, Walter "displays not only a death wish but also possible signs of shell shock" in that final letter to Rilla. And I have to say, I agree. I'm sure LM Montgomery meant it as a noble goodbye on the part of Walter, and that still stands; interpreting Walter's statements also gets particularly tricky when considering his second sight aspects. However, in the letter Walter both sensed his death on the horizon due to those aspects, and at the same time welcomed it. Although it doesn't quite get to an explicit death wish - more framed as an acceptance of his fate - I think that reading is fair.

Notably, though, to go back to the main subject of this--Clement also ties in Walter's savage side. That Jekyll and Hyde is very reminiscent to the two sides of Walter seen in Rainbow Valley. Clement only questions Walter's "Hyde-ness", and I can see why: I think that portraying Walter as a murderous psychopath is definitely a step too far. However...we've seen how Walter gets when fighting for justice. That's inarguable. At the least, we know that WWI would have required Walter to tap into that part of himself. Ultimately, despite the coolheaded words, Walter has held hands with the side of himself that savagely beat Dan Reese, and that has a grip which does not let go. The essay even argues that Walter would be unfit to marry Una if he had returned:

In addition to these passages, in Walter's case specifically, we have precedent for the effect that fighting has on him - his fight with Dan Reese definitely "unleashed an unfitness of soul." Clement goes so far as to describe Walter as tainted, which, when viewing Walter as an individual, I'm uncomfortable with, but when viewing Walter as a symbol, makes complete sense.

Although it might feel icky to say this in the context of PTSD, I think Clement's point isn't about Walter being quote-end quote "damaged goods;" it's about highlighting that a just war is still war. As the passage itself states, fighting "God's battles" doesn't mean you will be spared from the aftereffects (or, one might say, the aftermath). Still, I dislike the framing here, until I remembered a passage from an earlier essay and everything clicked (yes, this conclusion is supremely obvious, but bear with me and my two brain cells). The previous essay (the white feather one I shared passages from earlier) comments that LM Montgomery wrote Rilla as a tribute to "Canada's girlhood," then goes on to say:

And so we arrive, at last, at the reasoning for Walter's savagery for Dan Reese, and as always, Walter's symbolism. Walter Blythe is Canada. The death of Walter's innocence - his "tainting" - could represent the death of the old world and its perceived innocence. He fought to save family and homes - Faith, in her girlhood - against the enemy, but in doing so, lost himself. And based on what we have here, I think Walter realized it. He couldn't live in the world after what he'd seen, but also, he didn't want to live in the world after what he'd done.

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

and is there honey still

Kissing Mary Vance was nothing like kissing Faith.

This realization, occurring a moment after the kiss ended, Jem’s hand still at Mary’s slender waist, her normally pale cheeks as pink as a rare mayflower, was followed immediately by the understanding that he’d never be able to tell anyone. There was no confidant he could trust with such a secret, even if he could bring himself to so violate the rules of gentlemanly behavior. It just wasn’t done and that was before he considered speaking of kissing Mary Vance, who was accepted as Miss Cornelia’s adopted daughter, but whose personal history was never quite forgotten.

Susan, should she ever hear of it, would be scandalized beyond comprehension.

Jem would never eat another slice of her strawberry pie.

His friends and siblings would be confused, Faith put out, her pique covering any feelings of betrayal, for all that there was nothing binding between them.

Mother would be disappointed and Dad would shake his head.

The expression in Mary’s eyes, those queer eyes he now saw were the color of moonstones, told him she understood it all.

“It’s nothing to make a fuss about,” she said. Faith would have tossed her head making such a remark, her golden-brown curls shown to advantage, but Mary only looked at him steadily and let the hand that had been on his shoulder drop to her lap.

“You hold yourself too cheap, Mary,” Jem said.

“That ain’t—that isn’t possible,” she replied. “Anyway, what’s a kiss amount to?”

It was a good question, one Jem had thought he’d known the answer to, just as he thought he’d known the answer to the question she was laboring over at her desk in the empty classroom, a piece of paper scribbled over and crossed-out, grey smudges on the foolscap, on Mary’s white cuffs. She would’ve laundered them herself, being Miss Cornelia’s daughter not relieving her of her housekeeping duties, chores she’d call them though Jem knew none of his sisters had ever helped even pinning clean clothes to the line.

He supposed a kiss could be an ordinary thing, a peck on the cheek or the lips, a greeting, friendly and inconsequential as a wave, a forgettable gesture of a mild affection.

Kissing Mary Vance was nothing like that.

He could say, in all honesty, that he hadn’t planned it. He’d been pointing out something in her writing, a tricky bit she’d gotten tangled up in, and she’d been peering down at the page, trying to make it out. When she’d perceived her mistake, she’d looked up at him, her expression one he’d never seen before, victory and pride and delight all swirled together, altering her face from one he’d recognized without being aware of it into one he’d been startled to discover. Without a word, without a thought, he’d leaned in and kissed her parted lips before she crowed over her achievement or thanked him, the caress impetuous, a whim, irresistible.

She was irresistible. He’d grazed her lips with his own and in the space before the next heartbeat, he’d cupped her jaw with one hand and let the other drop to her waist to draw her close. He felt the most tremendous desire for her possess him, everything else dropped away. She tasted, quite impossibly, of honey, though that was perhaps because he had always liked honey best, and she was warm in his embrace, coming closer when his hand at her waist reached around her back, sighing a little when he stroked her cheek and angled her head to be able to kiss her more deeply. Every second, his desire for her ratcheted sharply upwards and she met him, her hand clutching his shoulder, her sharp tongue sweet in his mouth. She kissed the way a fast girl kissed but there was a terrible innocence to her response that made him know she’d never kissed anyone else, whatever she might have intimated to his sisters and her friends.

He couldn’t say why he’d broken away.

A sound in the hallway or her sudden stillness when his hand grazed her breast, the need to breathe, the pounding of his heart felt throughout his whole body.

“It doesn’t have to mean anything,” Mary went on when he was stayed silent.

“Are you sorry?” he blurted out, and hearing the words he became suddenly terrified that he’d transgressed, become that monster Reverend Meredith always warned of in his gentle way, a man consumed by his appetites, greed and lust. “Oh, God, Mary, have I made you do something you didn’t want—”

“As if you could!” she said, wry again, Mary Vance again as he’d ever known her. If she’d wanted to, she would have slapped him, he was sure of that. “There’s no person living who could make me do what I didn’t want and certainly not you, Jem Blythe.”

“That’s good, I suppose,” he said, chastened, still too close to her. Still tasting the honey-sweetness of her lips, feeling the sound of the quiet moan of hers he’d swallowed in his throat.

“We don’t have to talk about it anymore,” she offered. “Or ever again. It could be just something that happened once, like as if you’d knocked over my inkwell, and we can forget about it. If that’s what you’d like. To be easy about it.”

“We don’t have to talk about it anymore,” he repeated, agreeing. An inkwell knocked over would leave a stain, one endless scrubbing would never entirely remove. “But I won’t forget. I shan’t.”

“That’s good, I suppose,” she said, her old tone mixed in with a new softness. He’d mussed her hair and some of the loose strands caught the light, a far cry from the usual trig appearance Miss Cornelia insisted upon. He wasn’t sure he’d ever see this Mary again, but it might be enough, to have seen it this one time. It was more Walter’s way to say he’d carry it as a talisman, but Jem felt it without saying it, that to have this moment might serve him well in the future.

“Mind you turn that paper in,” he said.

“Mind yourself, then,” she said and turned away.

He wouldn’t see Mary alone for another ten years.

“Thought I’d find you here,” Mary said, sitting down beside him, facing the water. She tucked her skirt around her and made no effort to conceal her sturdy, scuffed boots. It was a cool evening, cooler by the shore, but she didn’t have a coat or even the old wool shawl she’d refused to give up before he’d left for France. He shrugged off his own coat and offered it to her. He’d be warm enough in his heavy jersey, one the fisherman down at the harbor wore when the wind picked up.

“Not Rainbow Valley?” he said.

“Why would you go there? You’re not a child anymore. Haven’t been for a long time, unless I miss my mark,” she said.

“No, you’re right,” he said. “Not for a long time.”

“You don’t have to talk to me about anything. Not about the War or Walter or being a prisoner,” she said. She said it without any particular tenderness, which was the most consoling part. He recalled, very dimly, that before she had come to Miss Cornelia, she’d lived through her own horrors, yet spoke of them rarely if at all.

“Don’t have to tell me about any French girls either,” she added and he laughed.

It was the first time he’d laughed since he came home. Since he came back to the Glen, anyway, and called it home without being able to fully mean it.

“Not much to tell there. I mostly saw nuns and the Red Cross nurses are awfully brisk, whatever their nationality,” he said.

“I’ve always thought Cornelia would make a good nun, for all that she’s married,” Mary said.

“Perhaps,” Jem replied. The waves kept breaking on the sand and it was dusk, romantic if you wanted it to be. Mary had his coat wrapped around her shoulders. Jem felt scoured, raw and empty.

“Why’d you come, if you don’t expect me to talk?” he asked after several minutes of silence.

“I guess because you need someone who doesn’t expect you to talk but who’s willing to sit nearby, without fussing over anything,” she said. “I’ve plenty of handwork and housework to deal with at home. I’m perfectly content to sit and be idle and there’s nothing you can say or not say that can hurt me. I’m not hurt the way you are, I can bear whatever you need—”

“They can’t at home,” he said. Mother, with grief in her grey eyes and grey in her auburn hair, and Rilla, grown into a mother before she was a wife, Dad with something more broken inside him than any of the rest. Susan and Dog Monday and the letters from Di and Nan, blotted and halting. Una, who might as well be one of the French nuns who tended him, all of them mourning Walter and trying to rejoice at his return. Jem, trying to keep them from hearing any of his nightmares, biting his tongue when they spoke at a meal of the future or the past.

“I know,” she said. “Faith Meredith’s married a Brit. Officer, Lord Something Hoity-Toity of Fancy Abbey-on-High.”

“I’m happy for her,” Jem said tiredly. “We were childhood sweethearts, that’s all.”

“I know. Just wanted it said so you’d know I know,” Mary replied.

“If she’d waited, I wouldn’t have wanted her. I wouldn’t want her to have me now, as I am,” he said. “Befouled, diminished—”

“Walter’s dead, Jem. You don’t have to speak in his voice,” Mary said.

“I wasn’t—”

“Yes, you were. If you don’t think I’d remember, after all those afternoons, those walks and rambles, listening to him, well then. You’d be wrong. I remember,” she said.

“I want Faith to stay as she is. Beautiful, golden, untouched, a lovely memory from my splendid childhood,” Jem said.

“Good Lord, she’d far better off than I thought, even without taking a castle into account,” Mary exclaimed. “Maybe her Lord Gawain-Excalibur-Avalon actually treats her like a women. A person.”

“I didn’t know you liked the Arthurian legends,” Jem replied, taken aback by Mary’s remark, choosing to deflect.

“I liked the sword. And the Lady of the Lake with her own place,” Mary said.

“I thought it would be like that, the War, knights going out,” he said. “I knew there’d be wounds and death, but I thought there’d be honor—"

“You always were a bit of a fool,” Mary said. “Stands to reason though, the way you were raised.”

“We had a—you’re right,” he said, realizing he did not have to defend his parents or Ingleside. “Mother was so careful for us to be well-loved. To live in a world where we might imagine ourselves heroes or able to speak with the fairies—you would have done better than I at the Front, Mary.”

“No one would do better,” she said. He braced himself for her to talk about his medals, his valiant efforts in the prison camp, how he tended those around him with what little he had. How many men had died in his hands, their blood the scent in his nose as terrifying as gas. “You lived.”

“It doesn’t seem like enough.”

“Come here, then,” she said, shifting to kneel facing him. The moon had risen and it suited her, her eyes gleaming like opals, her hair silver, the shadow soft around her bare throat. She reached a hand to touch his cheek, rough with the whiskers he hadn’t shaved for the past few days. “Come here, James,” she said and the sound of his name startled him enough to move closer. To let her draw his face to hers for a kiss.

For a moment, he was seventeen again and Walter was alive, the fields of France green, the chestnut trees in leaf. Then he heard a wave break and felt Mary’s hand move to the nape of his neck, her fingers callused, and he tasted salt mixed with honey. She beckoned him and he put his arms around her, holding her tightly, trying to lose himself in her embrace. Letting her find him.

They were alone with the moon and the sea. There was no hallway and Mary kissed him well enough there were no memories, not of France or Germany or Holland, not of the ship or the train or the graveyard with the stone too white, the wilting mayflowers at its base. There was nothing Mary would not do, no end to the comfort she would offer. His hands were at her waist and her breast, eased beneath her skirts, and she coaxed him on. When he brought both back to cup her face, she’d smiled under his lips. When he lay back against the sand and brought her to lie next to him, her head resting upon his chest, she’d come with him.

“I should have asked, Miller Douglas?”

“He married Ada Parker six months ago. I didn’t shed a tear, except that they should be happy,” she said. “To be honest, I didn’t fancy being a shopkeeper’s wife, but I would have made the best of it.”

“I’m alive, but I don’t know what I have to offer,” Jem said. Mary thumped him on the chest, hard enough to notice, soft enough to be nothing more than a scolding.

“You’ve yourself and I’m myself. You don’t have to offer me anything,” she said.

“That’s the first lie you’ve told,” he said.

“Then remember me. This. How it was, how it might be,” she said. “Grieve and suffer and if you want, I’ll be there for it. Or you can come round in a while, when you’re sorted out. I’m in no hurry. I’ve an idea of how to run a doctor’s house, no offense to your mother or Susan, and I’d like to try it out some time.”

“Will there be much pie?” Jem asked.

“There will be honey-cake, pots and pots of clover honey ready to drizzle. That’s your favorite.”

“Call me James again,” he said.

She propped herself up on his chest so he could see her face, the curve of her lips, her silvery hair hanging loose around her cheeks.

“I believe you meant to say, please, James. Mind yourself, then.”

Tagging @gogandmagog who posted this:

DIANA, teasingly: “You, anyhow. I saw you kissing Faith Meredith in school last week ... and Mary Vance, too.”

JEM:- “For mercy’s sake, don’t let Susan hear you say that. She might forgive it with Faith but never with Mary Vance.” From The Blythes Are Quoted

And @freyafrida who wrote "also want to write jem/mary fic now although i have zero ideas for anything apart from the ship"

#anne of green gables#jem blythe#mary vance#jem/mary#rarepair#canon au#post wwi#angst#tw: PTSD#romance#faith meredith#walter blythe#gilbert blythe#anne shirley#kissing#glen st mary#hurt/comfort#miss cornelia#mary vance is a total realist#POV Jem#veteran!jem

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Walter and Susan; Or, When the Gates of Fairie are Shut

@gogandmagog since you were curious on the why.

When we think of Susan Pevensie, we think of a girl who became a queen; a girl who lost her kingdom, a girl who decided she wouldn't love anything who wouldn't bother loving her back.

We think of siblings betrayed--Lucy, hurt and confused by "Susan The Gentle" caring about boys, and lipstick; about Peter's short "Susan is no longer a friend to Narnia."

We think of a sensible girl, a doubting girl, a girl, not a woman, though she had to grow up twice over.

We think of "The Problem With Susan", a girl cast out of Narnia (Heaven; Salvation; call it what you will) for the crime of perceived femininity.

(So often we forget that Susan made a choice to leave.)

(Is it fair, how we think of Susan? I don't know.)

"There is such a place as fairyland - but only children can find the way to it. And they do not know that it is fairyland until they have grown so old that they forget the way. One bitter day, when they seek it and cannot find it, they realize what they have lost; and that is the tragedy of life. On that day the gates of Eden are shut behind them and the age of gold is over."

(Montgomery,L.M)

A girl: Just a girl, or a "silly, conceited young woman", who cared more about lipstick and boys than she did anything else--a girl who lost her entire family at the age of twenty-one.

Was it a punishment?

Was it a kindness?

It was a cruelty, regardless.

(Susan was Susan the Gentle, and don't tell me that wasn't a choice she made, every day she ruled.)

CS Lewis mentioned that Susan may find her own way back to Aslan's country; whether Susan would want to remains a mystery.

In contrast, we have Walter Blythe. The "hop out of kin", the dreamer, the coward (until he isn't.) The bard, the chronicler, the sacrificial lamb. Walter is not "sensible", or practical, or inclined to doubt (Note we are told he's a church member, while Jem Blythe isn't, despite being romantically linked with Minister's Daughter Faith, and isn't that interesting?)

Walter has to die in the Great War. There is no other future for him; this starry-eyed boy who knew he was signing up to die. Walter Blythe knows stories, knows he's in one, knows there's no happy ending.

Because even if had Walter lived, I do not believe the gossamer-fairy part of him would never have returned from France. Like Susan, he too would need to find Narnia on a longer, harder road, and there is no guarantee it would be the land he knew as a boy.

Only a few, who remain children at heart, can ever find that fair, lost path again; and blessed are they above mortals. They, and only they, can bring us tidings from that dear country where we once sojourned and from which we must evermore be exiles. The world calls them its singers and poets and artists and story-tellers; but they are just people who have never forgotten the way to fairyland."

The Piper called Walter, and there was no denying that call. Walter's way was set before him, and he could not stray; a different, harder path than he was promised as a boy. Walter is no exile; Walter chooses to leave, so others can take his place.

Walter dies, and everyone he loves lives.

Susan lives, and everyone she loves dies.

Now all that remains is:

Can they find their kingdoms again?

#chronicles of narnia#lm montgomery#Walter Blythe#Susan Pevensie#Is this gibberish? Maybe#But I love them your honour

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

NIJI NO TANI NO ANNE (2003)

by lucy maud montgomery & hara chieko

#niji no tani no anne#anne in rainbow valley#anne of green gables#akage no anne#anne shirley#walter blythe#shoujoedit#oldanimeedit#*nikki

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished Rilla of Ingleside. And I can't say that it is my favourite in the whole serie with the second and third book ! Omg the ending, Jem, Walter... everything 😭

#bookworm#books and reading#booklr#book review#booksbooksbooks#book#reading#bookblr#booklover#books#rilla of ingleside#walter blythe#jem blythe

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fact that both walters in the anne books died too young and left a gaping hole in anne's life... anne outliving one walter and then the next... anne as the bridge between the two generations of loss... every walter she's loved she's had to grieve too soon... sorry i don't actually have a fully-formed thought i just thought of this and my heart kind of broke a little about it :/

#lm montgomery#walter blythe#walter shirley#the permanent psychic damage of the book series you were obsessed with as a little girl rearing its head at 1 am on a random college night

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you for voting!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

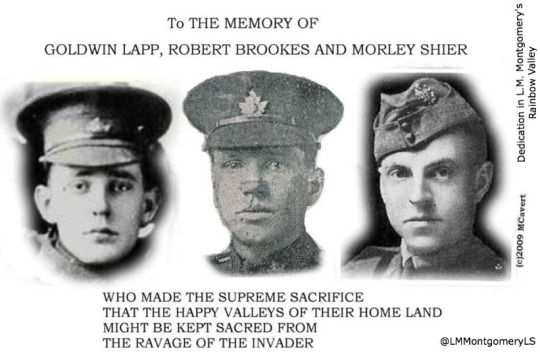

The L.M. Montgomery Literary Society posted this lovely photo of the three boys LMM dedicated Rainbow Valley to. It caused me to wonder who they were and what connection they had to Maud. I wrote a little bit of what I discovered below in honor of Veteran's Day/Rememberance Day. It seems they were members of the church her husband Ewan pastored in Zephyr. Maud and Ewan gave a going away dinner for the young men of their congregation and she wrote that her heart ached as she looked around the table at the young men they had come to know well.

Robert Brookes was the oldest of the three, at 32. Before leaving Canada, he left his farm to the care of his sister and her husband, and left documentation willing most of the land to them, as if he knew he would not return. Maud was close with him and his sister as they were close in age to her in a congregation of mostly young people or elderly. He took furlough to England, like Jims' father did. His sister wrote him there that she had a new baby daughter and he was thrilled to hear about his niece, writing "I want you to take good care of that little girl. I’m willing to go back and do my duty to the end, then when I come back she’ll be great company for me.” He returned to the front and was killed in the Third Battle of Ypres, reportedly while helping a wounded man to safety. He was quoted in local newspapers for his brave words, (link)and for how cheerfully he had given up his successful farm and went to defend his country. He was very close to his sister and wrote her many letters, similar to Walter and Rilla's relationship. His sister was understandably devastated. Maud remained close friends with her and supported her through this.

Maud ran an aid society and sent care packages to each soldier from Ewan's church. She was greatly incensed to receive a letter from a friend calling the war a "commercial" one. As a result of this she doubled down on her efforts to check on "the boys" and their families, becoming closest to these three.

Goldwin Lapp was just 22 when he was killed, and his parents bought a plaque at church "sacred to his memory" which Maud would later take inspiration from for Walter's plaque in Rilla.

Morley was a teacher who trained as a pilot, perhaps the inspiration for Shirley's flying. He was 23 when killed. His death was noted by LMM in her diary. Here is an article about that.

Most interesting of all, a member of the 116th battalion, mostly made up of Zephyr men, reported hearing a "bugler calling him" for years before the war and even wrote a poem about it. Perhaps this was inspiration for Walter's poem and premonition.

Sorry for the long post! I just found the tie-ins to Rilla and Rainbow Valley fascinating and wanted to share for anyone else interested. This website was a great source.

#rememberance day#veterans day#world war one#lucy maud montgomery#lmm#anne of green gables#rainbow valley#rilla of ingleside#walter blythe#shirley blythe#jem blythe

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is entirely canon uncompliant, but the ultimate LMM-fascinating-male-character crossover would be a university AU where Barney Snaith, Walter Blythe, and Dean Priest are all the same age and somehow friends (friends in the dark academia sense. A Marauders AU, if you will. Backstabbing and homoeroticism).

#i might write this as my chaotic and deranged contribution to the blue castle fan content challenge#lm montgomery#barney snaith#dean priest#walter blythe#the blue castle#emily of new moon#anne of green gables#blue castle book club

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

(anne of green gables) how certain the journey (5/7)

how certain the journey - walter/una - pg-13

Do forgive me, Walter thinks bitterly. I apologize that even a mere year over there is impossible to forget. The war is already fading, becoming simply a topic of conversation, a plot for novels — one that people are already growing tired of. They're paying their pension to the soldiers that lived, they are building memorials and putting plaques up for those who died. What more can they do? Wasn't living through the war penance enough?

Walter hates when they ask him what more he wants, because he doesn't know, he doesn't know if he wants apologies — though he knows he doesn't deserve them — or just for the world to stop turning, though he knows that he can't ask that, either. It's only — what the hell did all those men die for, to be buried again in memory? This is why he has to write about it, isn't it?

ao3

#anne of green gables#rilla of ingleside#walter x una#walter blythe#una meredith#i lost control AGAIN so. 7 parts!! send help!!!#i was trying to get this done in time for canadian figure skating nationals#bc i thought the timing would be funny#if that gives you an idea of how behind i am lmao#how certain the journey#freyafic

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

still making my way through this book of poems ("Fires of Driftwood") and it's interesting to see what seemed to inspire LMM, although I don't know the comparing publication dates (for example, there is straight up a poem called The Piper). Like this poem seems to be insight into what would have happened to a Walter who lived:

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

That it alone is high fantastical

“Oh, Mother, you’ll never guess! You’ll never guess in century of guessing!” Rilla cried out, sounding so much as she had as a little girl, for a moment, Anne could convince herself the War had never happened and that somewhere in Rainbow Valley, Walter sat writing a crown of sonnets in his leather-bound journal, his face dappled by the light, back braced against the bole of a birch tree, his grey eyes unfocused as he searched for his next word.

There was still a white stone in the graveyard. Shirley was in Toronto, having refused (albeit politely) to return to Glen St. Mary, much to Susan’s dismay, and Jem walked with a pronounced limp, his uneven gait announcing him as much as Mary’s voice.

There was a mystery there, Jem and Mary Vance, but Anne couldn’t see any way through it and Gilbert, lying beside her in bed, both of them tired but sleepless, told her not to try. Jem had seemed less removed, less falsely cheerful lately, and had begun talking about the medical course again, perhaps a specialty in obstetrics, a hospital practice. As far away from men dying in battle as he can get, Gilbert had observed and Anne had recalled Joyce’s little face, white as a mayflower blossom, and held her tongue.

Rilla, remarkably, given her exuberant entrance, had done the same in the absence of Anne’s response. Miss Oliver had left Ingleside some weeks ago, so there was no one to suggest Rilla either elaborate or calm herself, as her likeness to a whistling copper tea-kettle was increasingly pronounced.

“If I’ll never guess, dear, you must tell me,” Anne said. It was a relief that Rilla could still be the young girl she ought to be, for all that she wore Ken Ford’s diamond ring on her finger and was capable of a brisk, warm matronliness when it came to raising Jims, now reserved for the writing of letters to his new British stepmother and clucking over the missives she received.

“Faith Meredith has eloped!”

Anne did admit to herself she would never have guessed that, because for all her imagination, she wouldn’t have guessed something impossible.

“But, Rilla, Jem is with your father today, doing the Lowbridge rounds. Susan and I packed a lunch with plenty of pie for Dad and some of that flapjack Jem took to after being in England,” Anne said. He’d been in hospital in England, recovering from the injuries he’d sustained at the Front, in the prison camp, during his escape, none of which was spoken of. Only flapjack and stewed tea and how no cook in England was a patch on Susan and that you may tie to, uttered with some semblance of his old roguish humor.

“I didn’t say she married Jem, Mother!” Rilla exclaimed. Her cheeks were pink and her eyes were bright. She had a look of Gilbert at his most delighted about him, an expression Anne remembered from their childhood. Anne opened her mouth to speak but Rilla interrupted.

“It’s Bertie Shakespeare Drew! Faith Meredith is Mrs. Bertie Shakespeare!” Rilla said.

If Anne hadn’t already been sitting down, she would have, suddenly and gracelessly. As it was, the shirt she’d been mending fell from her lap.

“That’s—why, Rilla, are you sure?”

“I heard it directly from Mary Vance,” Rilla said, lifting a hand to stop Anne from speaking. “And Miss Cornelia Bryant. You know Miss Cornelia has no taste for gossip. Miss Cornelia’d heard it from Mrs. Meredith—”

“Poor Rosemary,” Anne said, before she could stop herself.

“Why poor Rosemary? I suppose they thought Faith and Jem would make a go of it, at least, perhaps Reverend Meredith and Mrs. Meredith did, but the War’s done funny things to people and Faith and Jem, they just didn’t fit any longer,” Rilla said. Sometimes, Anne felt Rilla reminded her of someone she couldn’t name and realized her youngest daughter spoke with the wisdom Anne’s own mother might have had. Plenty of folks in the Glen would find such a thought eerie, but Anne was comforted, for all that she ought to be the one offering a thoughtful explanation rather than receiving it.

“I suppose I meant the surprise, an elopement—”

“They must not have wanted to wait. Or were afraid someone would try to talk them out of it. Bertie’s mother maybe,” Rilla said.

Rosemary or her father, Anne thought. Jem, if he’d been given the chance, perhaps. Perhaps not, if Rilla was correct.

“Bertie Shakespeare Drew,” Anne said. “I remember when he was born. He’s just Jem’s age.”

“He’s not much like you remember him, Mother. He’s all tall and stalwart now and they say he’s going in for engineering, that he learned quite a bit in France, found he had a talent for that sort of thing. And his ears don’t stick out quite so much anymore,” Rilla said.

“There’re more things on heav’n and earth,” Anne said, mangling the quote a bit, fairly certain Rilla would not correct her. “D’you suppose Faith calls him Bertie? Or his full name—it’s quite a mouthful.”

Queenly Faith Meredith, the undisputed beauty of Glen St. Mary, who had a sense of humor but also a sense of herself as beyond any teasing, now to be Mrs. Bertie Shakespeare Drew. Anne smiled to herself and thought how Mary Vance would find a way to make Jem grin over it all. She’s lucky to get him, Mary would say, reversing the order the Glen would have assumed, and Mary, canny and unexpectedly kind, would have the right of it, perhaps.

Susan would be quite outraged and the pastry of her next pie might suffer for it, but Gilbert had always taken an unchristian glee in Susan’s outrage and wouldn’t mind the pastry being a bit heavier. It was still the best piecrust on Prince Edward Island, now that Mrs. Rachel Lynde was no longer living to give Susan a run for her money.

“Miss Cornelia said Faith was heard to call him Will, when she spoke to her parents. It’s after Shakespeare of course, and because he was so determined they marry,” Rilla said.

“And because Faith wanted to,” Anne said. She wasn’t sure if she meant the elopement or the name, but it was all of a piece.

“Miss Cornelia said they’d gone to New York for their honeymoon and she hoped Faith didn’t come back with a bunch of silly Yankee airs but Mary and I didn’t think that was likely,” Rilla said, sitting down beside Anne, picking up the shirt and starting to sew.

“She didn’t come back from England any different, after all,” Rilla said.

“Except that she didn’t marry your brother,” Anne replied.

“D’you know, Mother, even without the War, I don’t think they’d ever have gone through with it, Faith and Jem,” Rilla said. “It was, how shall I put it, like a childhood fairy tale, the honorable knight and the maiden fair, all sorts of adventures they had in Rainbow Valley. They were always going to grow up. We all were.”

Not Walter, Anne’s heart said. Not Joyce.

“I’m glad of Ken’s name, anyway. And don’t worry, I wouldn’t elope for anything. I want our families around us, as many as we can get, even if we have to wait. We’re rather good at that,” Rilla said. She’d finished the one shirt and picked up another. She peered at it, frowned. “I can’t think what Dad does to his clothes—”

“I’ve made up a thousand stories to try to explain that and I still don’t think I’ve figured it out,” Anne said. “Some things, my darling girl, are beyond explanation.”

This one's for @freyafrida because I didn't manage to squeeze Faith/Bertie Shakespeare into my Jem/Mary fic...

#anne of green gables#aogg#rare-pair#faith meredith#bertie shakespeare drew#faith x bertie#faithbertie?#romance#post rilla of ingleside#anne shirley#POV anne#rilla blythe#ken ford#rilla x ken#jem x mary#miss cornelia bryant#humor#angst#grief#walter blythe#joyce blythe#more allusions to class issues in glen st. mary#hope you like my faith and bertie fancasts

25 notes

·

View notes