#which are what one might say mostly relates to contemporary discourse

Text

i can't believe this keeps happening to me. i figure out a theory i think i might want to apply in my thesis, go look at the text that has the theory, and find that that text already mentions jane eyre

#DORRIT COHN WHEN I GET YOU#i'm trying to apply discordant narration bc i'm really realising how significant the judgements of the narrative voice are#for our understanding of the story#but cohn already said that the narrator's judgement are concordant with the overall story#which obviously. it's an “autobiography”#i'm not really sure how to angle this??#bc on the one hand it really makes sense to comment on how the narrative voice is the one that makes judgement statements most of the time#which are what one might say mostly relates to contemporary discourse#(along with pure description)#but it feels too risky bc it may start to sound like i'm saying that the narrative voice is expressing brontë's judgements#which is not what i mean at all#this is what i get for trying to write a historically contextualising thesis (not actually my thing)#narration is actually more my thing which is why i keep ending up back there#oh. that's what this is#i'm subconsciously trying to change the angle of the thesis to be about narration#fuck this is another completely separate essay isn't it#if you never hear from me again it's because i drowned in new essay ideas that can only come to fruition if i do a phd (not in my plans)#(at least not for another decade)#jag borde ha vetat att det här skulle hända

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

*This is absolutely a fic promotion, but plz hear me out on the discourse part too

So, self inserts and original characters, the worst fanfic catgeory (fanfiction.net literally says that in one of its fic groupings, and I'm pretty sure the number of views on any fanfic website says the same).

TLDR- Yes, I agree that this stereotype carries truth, but I do think SIs and OCs have more potential to be explored, and the stigma surrounding these labels is blocking that. And oh god I just want to know so badly if this is the deal with the work I'm currently writing or if I genuinely just can't write well.

The longer version- (this was written quite late into the night/ I'm in Singapore/, and might not be so well organized, I apologize for that.)

To what extent is this stigma "justified"? I mostly use AO3 for reading fics, and when I see the OC/SI tag, the thing is....I came to look for fics about canon characters and might not have the wish to invest my time in taking in a new character. I understand that most people who read fanfiction would feel the same. This, I think, is more or less justified. If you came to look for a certain canon character/relationship, and you don't want to get invested in any OCs, then of course the OC/SI tag isn't for you.

But... I think that's about it. Bcs here's the thing,

1. Using the OC/SI format does NOT automatically make the fic worse in quality. Hell, I'm not even sure if the statistical "fact" that these tags generate the worst fics is true. Judging from what I've read in the tma fandom and my other past fandoms, the stuff with OC/SI isn't inherently worse or better than the rest of the fics. There are ones that are pretty normal in writing quality, and the ones where the prose is rly good, others where plot design stands out etc. Of course, there is a lot of wish fulfillment and the like, but... there's also a lot of that in fics that write about canon characters.

2. I can't really say whether a wish fulfillment "I just want to write cool scenes/fluff" fic is better or worse than a more serious fic that explores some characterization or plot point. I think stories (all stories, books, fanfic, myths, everything) exist to entertain us and make us feel things. I am not sure if writing a feel good story is any less meaningful than writing a story that brings people "deeper" thoughts and makes them feel good in some other way. And this isn't even the issue at hand, because fundamentally, writing an OC/SI or not doesn't determine what the content is about. I agree that a larger proportion of OC/SI fics tend to be more on the lighthearted side, but... so is most of the content consumed in the other tags. Readers don't seem to have a problem with feel good stories/fix it fics etc when there is no OC or SI, so I don't see why that type of fic paired with an OC/SI should be considered any less "meaningful".

3. Guys/gals, what is an OC/SI?

Yes, it is very personal, and it is very wish fulfillment, but... isn't that like a common literature thing...like in general? Look at the works that "real writers" publish, from contemporary to the classics, which writer doesn't write about themselves? Like, just off the top of my head, Les Miserables, Marius? Um, Dante's Inferno? (and that guy did not self insert into some random thing he straightup went for the Christian Canon😂 used his real name too, so Jonny I guess if you feel awkward about your MCs name you can think of Dante//Jk). But seriously, self insert and wish fulfillment is a big part of literature itself, and while there are things to be said about these tropes, if people don't have that much of a problem with them in other literature, I don't see why fanfic OC/SIs shouldn't be treated the same.

4. in relation to the last point. More specifically...

I do think that a lot of fanfiction which write about the original characters are also OC/SIs to different extents. I've read fics that depict pairings where the author and readers project heavily onto one (or more) of the characters. I've read stuff where the author uses a minor character to explore the established world building/character dynamics and it's clear that it's an SI but with the appearance of being a canon character (and yes it gets tons more views than one that's written as SI). How do I know this? Because I am one of those readers who project onto those characters, and I know why I read those fics, I know why I like them. It's because I can self insert, and feel like I am part of the story, part of the world. Isn't that something most people want to do? I mean, Universal Studios? Specific franchise themed museums? COSPLAY??? Of course that's not all there is to engaging with a story, but what's the shame in wanting to be a part of an already established world building, or want to love a wonderfully designed character? (slight tangent, but if u feel like it's bcs ur not as interesting/cool as the story's world or other characters appear to be then I can tell you with certainty that's not true. You are very interesting and cool and absolutely deserve to be part of a fantasy world.) Isn't that a big part of why "real literature" is written and read as well? So... what's the problem with being like, okay, I'm just gonna insert myself into the world now, through this original character? Of course, I'm not asking for people who prefer to write strictly in canon characters to change that. What I mean to say is, writing it in the form of an OC/SI, doesn't make it a lot different from other fics, or hell, from classic literature even.

I think a potential problem might be the feeling that you are taking too much creative liberty with something that is established canon, by having your own character directly interact with it. But, um, can't the same thing be said if you take a canon character, and then proceed to project heavily onto them? Like, a big part of why I don't feel comfortable writing just canon characters is that I know I'm clearly projecting and it feels awkward to rewrite an already established character to explore my own thoughts/desires. I would rather just straightup design a new character. (this is all just personal feelings, I haven't thought enough about this to make any kind of argument here. And of course, the main reason is I can't trust myself to write canon characters that don't ooc in some way so having one as my protag might kill me with my own awkwardness. )

5. the potential.

Now this is looking far ahead because I'm not sure how much our current system for distribution of knowledge & copyright can allow it. But damn. The OC/SI thing has a lot of potential. There is one thing that makes it different from writing in canon characters, and that is the way it opens up a clear space for you to add your own experience into the story. When exploring your own world view through the lense of an already established world, or vice versa, so much can be revealed about both, perhaps even bringing to light aspects of the narrative the author hadn't previously seen. We all know this feeling, it's when we ramble on about one of our stories or worlds to a friend, and they point something out, and we're like ooooh that makes a lot of sense but I hadn't thought about it before. Yea, like those moments. Stories are generally made more interesting by their interaction with many different perspectives/experiences. With OC/SI it straightup allows you to be like, okay, I'm going to engage my own experience with this fictional world/character now. I mean, isnt that also a large part of how fanfics work in general? Readers/writers bouncing symbols and experiences off each other in the form of stories? Reading about the various interpretations of canon stuff? Whats the problem with tagging it as it is? I'm just thinking about the fics that could have been written as OC/SI and explored the story in some fascinating way which weren't written at all or were discontinued bcs the number of views discouraged those authors. (I feel that with my current work as well, though I have already written half of it and the remaining half is too juicy to give up so I'll probably be completing it)

6. conclusion, sorta

I guess what I want for OC/SO fics is just the same treatment as everything else. Saw it in the tags you were searching for? Look at the teaser. Do you find it interesting? No, then very well. Yes, then click in and take a look. Do you like the writing style? Are you getting into the narrative?... etc. You know, like, same standards you would have for any other kind of fic. Not feeling like you want to read about a new character? Cool, no problem at all, click away. But I do not think that the current difference in number of views is just based on whether readers are interested in reading about a new character or not. In fact, that's what I want it to be. Show me that "true" difference, the one without the stigma behind it, because, as the same goes for every kind of stigmatized community, you're not receiving the proportionate amount of positive feedback, but what's worse is you can't even trust the criticism you receive. If no one engages, or someone gives a negative feedback, how am I supposed to know if it's because my writing is bad? or my teaser wasn't interesting? or my character was badly written/designed? Or if it was to a certain extent, bcs of the stigma? I do want criticism, of course I do, it's the first step to every improvement, and I would love it if I could get feedback that I can trust. (and this brings us to the truely "oppressed" community of the fanfic world, the people who write very good but cant write interesting teasers//jk)

7. the entirely skippable straw man rant part, also the expression of my love for The Magnus Archives.

some straw man: if you like writing your own characters so much, why not just write your own story entirely? and publish it?

You think I'm not annoyed about that? Here's the thing, I LIKE THIS WORLD I READ FROM THIS BOOK/SOME OTHER FORM OF MEDIA OR WHATEVER, I like it, it's brilliant, I want to write for it, about it, be in it, think about it, read about it, engage in whatever way I can. I CAN'T just "go write my own." And who do you think is more annoyed about not being able to publish the stuff? (According to you) I have written something that is potentially publishable (thank you btw I know you don't exist and is a strawman I invented just now but I've gotta get my compliments where I can//Jk), and I can't publish it in any potentially big way (and rightfully not) because I have no copyright over the characters. I worked hard to design my character, to make the plot meaningful, and to study the original canon plot and characters so that it would all fit together (I mean, partially bcs I can't force myself to sit down and write sth that is any less complex), and I can't actually publish it where more people will read it. And of course, on top of that, even less people will feel like reading once that "original character" tag is up. Does it look like I would be here if I could "just write my own"?

(slight tangent but come on what even is "your own"? how many classic European lit books were just fanfics of each other which were all just fanfics of the Bible or Greek mythology or sth? Stories and symbols have no boundaries it's the economic system that drew those.)

Damn this got way longer than I thought and it's morning now😂 guess I ran out of space to actually promote my fic, might have to do that in a seperate post then. But to anyone who actually read up to here, I'm so sorry for wasting your time no but srsly thanks for reading all of these jumbled thoughts, and good luck with whatever you are working on at the moment, I know you're probably working on something if you're reading through these tags. And of course good luck to the tma folk we're gonna face the end together🙏. good night (I should rly go to sleep now😂)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lili Reinhart Grows Up

The Riverdale actress plots her move to the big screen

Lili Reinhart almost didn’t sign on to co-star in Hustlers. The 23-year-old Riverdale star—Generation Z’s Blake Lively—was sent the script by her team, with the note that the director, Lorene Scafaria (The Meddler), wanted to meet with her. But Reinhart blanched when she saw the logline: “‘Strippers in New York drug and rob men on Wall Street.’ And I was immediately like, ‘Oooh, this is probably not the vibe that I want.’”

But after she conveyed that message to her team, they persisted. “They were like, Read the script. So I did, and it was obviously amazing.”

Reinhart feels pretty good about that decision now. Hustlers—which stars Jennifer Lopez and Constance Wu, as well as Cardi B and Lizzo in small roles—promises to be the sort of buzzy, commercially successful film that seems almost too well constructed and well timed to be true for a young television star aiming to embark on a movie career.

The actress—who grew up in Cleveland before relocating to Los Angeles—plays a stripper named Annabelle in the film, which is based on a true story about a group of Scores dancers (depicted in a 2015 New York–magazine article by Jessica Pressler). Under the guidance of a de facto den mother (Lopez), the group decides to embark on a scheme to drug affluent men by employing a potion concocted out of MDMA and ketamine. Annabelle’s function is as a sort of bait—she meets the men at a bar and then her “sisters” (Lopez, Wu, Keke Palmer) show up to join them, and, well, things get murky (for the men) from there. Whatever the opposite of nerves of steel is, that’s what Annabelle’s afflicted with, as she—in a running gag—vomits whenever things get dicey or tense, which, as you can imagine, happens quite a bit.

One of the major draws of the film for Reinhart was getting to be a part of the stellar all-female ensemble, and she says she tried her best to see her very famous co-stars as, simply, co-workers. While she says she’s “definitely seen Monster-in-Law multiple times [and] definitely had ‘On the Floor’ on my iPod Nano,” she tried to view J. Lo as the movie-actor equivalent of the person one cubicle over. “I’m not trying to toot my own horn, but I really am not star-struck very much unless it’s, like, Lady Gaga … or probably Meryl Streep.… I really try to not have any preconceived notions when I meet anybody. I truly just tried to look at Jennifer as my co-star who has had … an incredible career.”

Life After Graduation

Reinhart—who plays Betty Cooper on Riverdale, one of the CW’s biggest hits of the past five years—seems destined to follow the trajectory of a Michelle Williams or Lively before her, who went from playing the female lead in a very popular television show adored by teenagers to full-fledged movie star. Making that transition in the public eye is not necessarily without its stresses, though. Reinhart is extremely close with her Riverdale co-stars, and is dating Cole Sprouse, who plays her love interest on the show. Ask the nearest 16-year-old in your vicinity and you’ll undoubtedly get a lengthy discourse on the topic. But she sounds very excited for the career phase that will start after the series has ended.

In Hustlers, Lili Reinhart, Jennifer Lopez, Keke Palmer, and Constance Wu play strippers who drug and rob wealthy men.

“Oh, God, I think I could get in trouble if I answer that too honestly,” she says, laughing, when asked how she currently feels about working on Riverdale. “I think my heart is really in films. It’s really wonderful to have a steady job and to work with a group of people who are like my family. Truly. I see them all the time. We all live in the same city.”

She says she does appreciate that the show gives her new angles of Betty to play week to week. “Riverdale has so many twists and turns and offers us, unlike I think a lot of other shows, opportunities to do so many things.... One episode it feels like I’m in a horror movie and the next episode I’m in a drama, and the next episode I’m doing a period piece. It feels like you get a piece of everything and I think that’s really what helps keep it interesting.… I’m very lucky in that regard.”

With a starring role on a breakout CW show comes a massive social-media fan base, and Reinhart now has a cool 19.8 million Instagram followers to her name. Somewhat unusual among her contemporaries, she blends the requisite magazine-photo-shoot and promotional posts with quirkier slice-of-life samplings, including memes, shots of flowers and scenery, and poems. She explains, “I don’t want someone to look at my social media and just see photos of me on a red carpet or my magazine shoots.... I don’t want to follow people who just post beautiful photos of themselves. I think that’s quite boring, so I try not to be that person.”

And she speaks with conviction about trying to present a more realistic portrayal of who she is on social media: “I’m literally laying in bed right now in a T-shirt with no makeup on because I go to work in a couple of hours, and I’m going to go to the gym after I take a nap,” she says on the phone. “My life is not always glamorous. It hardly ever is. I want people to see that.” She goes on, “I think there’s nothing more un-relatable than people who have incredibly perfect bodies and who are on yachts all the time. I’m like, ‘That’s great, but that’s not.... You’re like the 1 percent of the 1 percent, you know?’” I comment that it does feel like half of my Instagram feed was on Capri all summer, and she laughs. “I wish I had time to sail around Italy, but I’m hustling, and I’m working my ass off.”

Reinhart has also become a tabloid mainstay, due in large part to her relationship with Sprouse, which she keeps mostly private—and she does not feel an obligation to speak about or share that aspect of her life. “It’s never an intention of mine to, like, hide facts about my relationship, but it also isn’t for the world to know.”

She seems to understand that other actresses might handle the position she is in differently, and she is self-aware, and wise, about her image. “I have a little bit of a cold exterior sometimes,” she admits. “You kind of have to crack me open a little bit. I think that’s just who I am. Some people are very much an open book, and they’re warm and friendly the second you meet them. I just don’t really think that’s me. I’m a little bit more closed off, and that’s O.K. I think I don’t have to try to pretend to be something that I’m not just because I’m on a CW show and I have young fans. I don’t really need to be sharing everything about my love life and my friendships just because that’s what teens are doing right now. I feel like I cherish being more reserved.”

It’s hard, after talking to Reinhart for any period of time, to not come away with a sense that this is a woman—particularly for someone only 22—who really knows who she is and what she wants to be spending her time on. She has drive and gravitas, but also a sense of humor, not taking the Hollywood of it all too seriously. She already wrapped the coming-of-age, drama-romance film Chemical Hearts, which she stars in and for which she also serves as an executive producer. And she cites the words of Jeff Bridges when asked about the next stages of her career. “He said once that every project he does he tries to make a one-eighty from the last project that he did.”

She continues, “I’m still in this very experimental phase of my career, which is exciting because it allows for a lot of firsts.… I have the opportunity to try a lot of things and not be typecast and sort of lay the foundation, hopefully, for the rest of my career where people can be like, Oh yeah, she can play whatever role she wants to play.”

382 notes

·

View notes

Link

You know what America needs? More mirrors for princes—the Renaissance genre of advice books directed at statesmen. On the Right, we have many books that identify, and complain about, the problems of modernity and the challenges facing us. Some of those books do offer concrete solutions, but their audience is usually either the educated masses, who cannot themselves translate those solutions into policy, or policymakers who have no actual power, or refuse to use the power they do have. Scott Yenor’s bold new book is directed at those who have the will to actually rule. He lays out what has been done to the modern family, why, and what can and should be done about it, by those who have power, now or in the future. Let’s hope the target audience pays attention.

The Recovery of Family Life instructs future princes in two steps. First, Yenor dissects the venomous ideology of feminism, which seeks to abolish all natural distinctions between the sexes, as well as all social structures that organically arise from those distinctions. Second, he tells how the family regime of a healthy modern society should be structured. By absorbing both lessons and applying them in practice, the wise statesman can, Yenor hopes, accomplish the recovery of family life. (Yenor himself does not compare his book to a mirror for princes; he’s too modest for that. But that’s what it is.)

…

You will note that this is a spicy set of positions for an academic of today to hold. You will therefore not be surprised to learn that Yenor was the target of cancel culture before being a target was cool. He is a professor of political philosophy at Boise State University, and in 2016, in response to Yenor’s publication of two pieces containing, to normal people, anodyne factual statements about men and women, a mob of leftist students tried to defenestrate him. Yenor was “homophobic, transphobic, and misogynistic.” (We can ignore that the first two of those words are mostly content-free propaganda terms designed to blur discourse, though certainly to the extent they do have meaning, that meaning should be celebrated—I would have given Yenor a medal, if I had been in charge of Boise State.) They didn’t manage to get him fired (he has tenure and refused to bend), but the usual baying mob, led by Yenor’s supposed peers, put enormous pressure on him, which could not have been easy. He still teaches there; whether it is fun for him, I do not know, but it certainly hasn’t stopped him promulgating the truth.

…

Yenor begins by examining the intellectual origins of the rolling revolution, found most clearly within twentieth-century feminism. One service Yenor provides is to draw the battle lines clearly. He does this by swimming in the fetid swamps of feminism; I learned a lot I did not know, although none of it was pleasing. He spends a little time discussing so-called first-wave feminism, but much more on second-wave feminists, starting with Simone de Beauvoir, through Betty Friedan, and into Shulamith Firestone, this latter a literally insane harridan who starved herself to death. The common thread among these writers was their baseless claim that women had no inherent meaningful difference from men, and that women could only be happy by the abolition of any perceived difference. This was to lead to self-focused self-actualization resulting in total autonomy, and a woman would know she had achieved this, most often, by making working outside the home the focus of her existence. Friedan was the great popularizer of this destructive message, of course, which I recently attacked at length in my thoughts on her book The Feminine Mystique.

…

After this detailed examination of core feminist ideas, Yenor suffers more, slogging through the thought about autonomy of various two-bit modern con men, notably Ronald Dworkin and John Rawls. He analyzes the dishonest argumentative methods of all the Left, in general and in specific with regard to family topics—false claims mixed with false dichotomies and false comparisons, what he calls the “liberal wringer,” the mechanism by which any argument against the rolling revolution is dishonestly deconstructed and all engagement with it avoided. The lesson for princes, I think, is to not participate in such arguments, and to remember what our enemies long ago learned and put into practice—that power is all.

Yenor describes how the modern Left (which he somewhat confusingly calls “liberalism,” but Rawls and his ilk are not liberal in any meaningful sense of the term, rather they are Left) uses the law to achieve its goal of the “pure relationship,” meaning the aim that all relationships must be ones of free continuous choice, that is, without any supposed repression. This leads to various destructive results when it collides with reality, including the reality of parent-child bonds, and more generally is hugely destructive of social cohesion. From this also flow various deleterious consequences resulting from ending supposed sexual repression; this section is replete with analysis of writings from Michel Foucault to Aldous Huxley, and contains much complexity, but in short revolves around what was once a commonplace—true freedom is not release from constraints, but the freedom to choose rightly, to choose virtue and not to be a slave to passions, and rejection of this truth is the basis of many of our modern problems.

…

Finally, Yenor turns to what should be done, which is the most noteworthy part of the book. As he says, “Intellectuals who defend the family rightly spend much time exposing blind spots in the contemporary ideology. All this time spent in the defensive crouch, however, distracts them from thinking through where these limits [i.e., the limits Yenor has just outlined in detail] point in our particular time and place. Seeing the goodness in those limits, it is necessary also to reconstruct a public opinion and a public policy that appreciates those limits.” Thus, Yenor strives to show what a “better family policy” would be.

This is an admirable effort, but I fear it is caught on the horns of a dilemma. The rolling revolution does not permit any stopping or slowing; much less does it permit any retrenchment or reversal. Our enemies don’t care what we think a better family policy would be. And if we were to gain the power to implement a better family policy, by first smashing their power, there is no reason for it to be as modest as that Yenor outlines—rather, it should be radical, an utter unwinding of the nasty web they have woven, and the creation of a new thing. Not a restoration, precisely, but a new thing for our time, informed by the timeless Old Wisdom that Yenor extols. The defect in Yenor’s thought, or at least in his writing, is refusing to acknowledge it is only power that matters for the topics about which he cares most. But presumably the future princes at whom this book is aimed will know this in their bones.

Yenor himself doesn’t exactly exude optimism. Nor does he exude pessimism, but he begins by telling us that “we are still only in the infancy” of the rolling revolution. This seems wrong to me; in the modern age, time is compressed, and fifty years is plenty of time for the rolling revolution, a set of ideologies based on the denial of reality, to reach its inevitable senescence, when reality reasserts itself with vigor. This is particularly true since every new front opened by the revolution is more anti-reality, more destructive, and more revolting to normal people, who eventually will have had enough, and the sooner, if given the right leadership.

…

For most purposes, what Yenor advocates would be a restoration of family policy, both in law and society, as it existed in America in the mid-twentieth century. I’m not sure that’s going back far enough for ideas. You’re not supposed to say it out loud, and Yenor doesn’t, but it’s not at all clear to me that even first-wave feminism had any virtue at all. To the extent it is substantively discussed today, we are given a caricature, where the views of those opposed to Mary Wollstonecraft or John Stuart Mill are not told to us, rather distorted polemics of those authors about their opponents are presented as accurate depictions, which is unlikely, and even those depictions are never engaged with. But we know that most of what Mill said about politics in general was self-dealing lies that have proven to be enormously destructive, so the presumption should be that what he said about relations between men and women was equally risible.

…

Penultimately, Yenor addresses such new frontiers being sought by the rolling revolution, with the implication that the rolling revolution might, perhaps, be halted. Here he talks about the desire of the Left to have the state separate children from parents, particularly where and because the parents oppose the revolution, but more generally to break the parent-child bond as a threat to unlimited autonomy. He says, optimistically, “No respectable person has (yet) suggested that parents could be turned in for hate speech behind closed doors.” But this has already been proven false; Scotland is on the verge of passing a new blasphemy law, the “Hate Crime and Public Order Law,” and Scotland’s so-called Justice Minister (with the very Scots name of Humza Yousaf) has explicitly noted, and called for, entirely private conversations in the home that were “hate speech” to be prosecuted once the law is passed. A man like that is beyond secular redemption, yet he is also a mainline representative of the rolling revolution. The reality is that discussion does not, and will never work, with these people, only force. Still trying, Yenor presents a balanced picture to his hoped-for audience of princes, such as discussing when state interference in the family makes sense (as in cases of abuse). However, such situations have been adequately addressed in law for hundreds of years; the rolling revolution is not a new type of such balancing, but the Enemy. Discussions about it will not stop it. No general of the rolling revolution will even notice this book, except in that perhaps some myrmidons may be detached from the main host to punish Yenor, or to record his name for future punishment.

Yenor ends with a pithy set of responses to the tedious propagandistic aphorisms of the rolling revolution, such as “Feminism is the radical notion that women are human beings.” And, laying out a clear vision of a renewed society based on the principals he has earlier discussed, he tells us, “In the long term, the goal is to stigmatize the assumptions of the rolling revolution.” No doubt this is true; cauterizing the societal wound where the rolling revolution will have been amputated from our society will be, in part, accomplished by stigmatizing both the ideas and those who clamored for them or led their implementation. How to get to that desirable “long term,” though, when their long term is very clear, and very different from the long term Yenor hopes for? He says “Prudent statesmen must mix our dominant regime with doses of reality.” Yeah, no. Prudent statesmen, the new princes, must entirely overthrow our dominant regime, or not only will not a single one of Yenor’s desired outcomes see the light of day, far worse evils will be imposed on us. Oh, I’m sure Yenor knows this; it’s the necessary conclusion of Yenor’s own discussion of those eagerly desired future evils. He just can’t be as aggressive as me. I’m here to tell you that you should read this book, but amp up the aggression a good eight times—which shouldn’t be a problem, especially if you have children of your own, whose innocence and future these people want to steal.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Was listening to “What a Hell of a Way to Die,” a podcast about war and the U.S. military, which has an interesting episode on pacifism and how it’s usually understood politically and culturally. Along with anarchism, staunch support for the concept of pacifism is one of the pillars of my worldview that’s definitely become more... complicated as I get older. It’s hard to argue, in the face of certain historical (or even contemporary!) events, that pacifism especially in more absolutist forms is always the most moral course of action, and there’s this common retort to people articulating a pacifist position, or even who are suspected of holding such a position, that involves weaving a counterfactual in which you have no choice but to commit violence.

But, as their guest points out, that’s true of any ethically monstrous act. It’s always possible to come up with a sufficiently contorted thought experiment that will get you to the answer you want--that doesn’t mean the thought experiment is in fact correct, or even useful. And what starting from a position of committed pacifism does is it forces the consideration of options other than violence. Because once it’s available as a solution, violence is a really tempting tool. But that it is so tempting, so emotionally satisfying to articulate, should make it suspect--besides the fact that it so rarely turns out as neatly and cleanly in your favor as one would expect--and maybe it’s good that the episode I listened to right before this was about Afghanistan, and how the current moral dilemma there is “prolong a government whose existence is being propped up by the US, and thus the civil war against that government, which is killing tons of people, mostly native Afghans, or withdraw and probably let the Taliban take over again.” Like, there’s no good option there--but what is the solution? To keep killing people and hope a good option eventually appears that makes all those deaths worth it?

Violence is baked deeply into the human psyche, and deeply into the American political psyche more than anything. A generation of action movies and Tough Guys Who Get Things Done and a narrative of American supremacy under which perceived national humiliation was intolerables, I am convinced, a major reason why the response to 9/11 was to invade Afghanistan in the first place (with the fig leaf of an absurd ultimatum beforehand). It has made admitting that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (by any reasonable measures boondoggles and failures and astonishing wastes of resources and human life) were mistakes essentially impossible. Even if in theory a moral case can be made for violence under highly contingent circumstances (just as it can be for murder or cannibalism or burning the Mona Lisa) doesn’t mean we should have anything like the rapid recourse to it that we do in our political discourse. And maybe the only way to make that case is to articulate a vision of what is possible if you do start from the heuristic of strong pacifism.

The classic argument is, as the podcast discusses, well, what about the Nazis? What about Hitler? What about World War 2? Was pacifism a good or moral idea in 1941? Essentially, they point out, you ought to reject the premise--because while pacifism might have been of very little use in 1941, Hitler did not appear ex nihilo that year, and there are absolutely points in 1939, in 1933, in 1923, or earlier, when an approach other than “threaten our enemies with violence” might have resulted in a very different outcome for Germany in the 1940s.

This is, I think, something it’s super popular, even (especially?) on the left right now to ding liberals and centrists for. “They don’t even think it’s OK to punch Nazis! What a bunch of apologists for fascism!” The common centrist defenses of nonviolence--”civility” and “marketplace of ideas” and “not liking what someone says, but they have a right to say it” get sneered at, and yeah, I’m not gonna lie, I find the platitudes wear pretty thin pretty fast. But that doesn’t mean they’re wrong, it doesn’t mean that the observation that a quick recourse to violence, while emotionally satisfying, is never as effective as its proponents would like you to think. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t other ways to respond to violence and hatred and authoritarianism that are impossible to consider so long as physical violence is considered an appropriate and easy reply. And this goes doubly for international relations, where the temptation of a quick drone strike or a missile strike versus the political considerations of sending in troops versus the political cost of doing nothing makes the choice even more stark.

I guess all that is a preamble to me shrugging and saying--yeah, I don’t know if pacifism is always the morally correct stance. I think pacifists can reasonably and correctly make a choice not to answer violence with violence in defense of themselves--but I don’t know if they can demand others do that, too, or passively permit violence against other people. That doesn’t sit well with me. But I do think that as a moral heuristic, pacifism is probably a very good one, one that does not get nearly enough credit, and I do think the failure to give it serious weight, to refuse to consider any pacifist a Truly Serious Person, the eager willingness to bite the bullet (ha ho) of violence (despite that being the default political position of 99.9% of humanity throughout its entire history, and so not much of a bullet!) usually means violence becomes the first option rather than the last, and we cannot begin to understand just how much we impoverish our politics and our world by refusing to reject true compassion as a “realistic” option.

#i should note#that as conflicted as i am#i probably could never honestly describe myself as anything *other* than a pacifist

171 notes

·

View notes

Photo

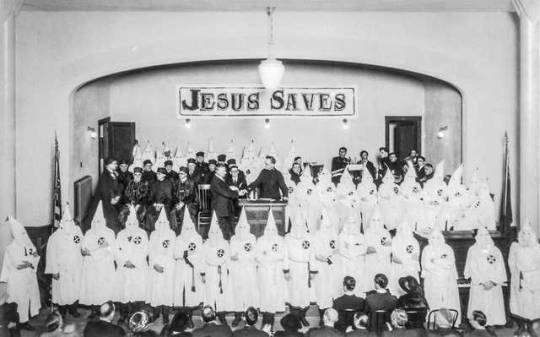

The Algorithmic Rise of the “Alt-Right”

While furthering my reading on the synergies being formed through our recent presidency and the resurgence of white extremist terrorism the data many seem to be pointing to is how important technology is in the rise of such ass backwards systems. Here’s a great review on the way in which capitalists adored ‘big tech’ itself has been infiltrated by such oppressive forces that have, as many of us realized, been with us since the creation of this country. Here are some highlight excerpts off this delve into white supremacist ideals in technologically based network systems:

In a sense, we’ve managed to push white nationalism into a very mainstream position,” @JaredTSwift said. “Now, we’ve pushed the Overton window,” referring to the range of ideas tolerated in public discourse. Twitter is the key platform for shaping that discourse. “People have adopted our rhetoric, sometimes without even realizing it. We’re setting up for a massive cultural shift,” @JaredTSwift said. Among White supremacists, the thinking goes: if today we can get “normies” talking about Pepe the Frog, then tomorrow we can get them to ask the other questions on our agenda: “Are Jews people?” or “What about black on white crime?” And, when they have a sitting President who will re-tweet accounts that use #whitegenocide hashtags and defend them after a deadly rally, it is fair to say that White supremacists are succeeding at using media and technology to take their message mainstream.

Networked White RageCNN commentator Van Jones dubbed the 2016 election a “Whitelash,” a very real political backlash by White voters. Across all income levels, White voters (including 53% of White women) preferred the candidate who had retweeted #whitegenocide over the one warning against the alt-right. For many, the uprising of the Black Lives Matter movement coupled with the putative insult of a Black man in the White House were such a threat to personal and national identity that it provoked what Carol Anderson identifies as White Rage.In the span of U.S. racial history, the first election of President Barack Obama was heralded as a high point for so-called American “race relations.” His second term was the apotheosis of this symbolic progress. Some even suggested we were now “post-racial.” But the post-Obama era proves the lie that we were ever post-racial, and it may, when we have the clarity of hindsight, mark the end of an era. If one charts a course from the Civil Rights movement, taking 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) as a rough starting point and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the close of Obama’s second term as the end point, we might see this as a five-decades-long “second reconstruction” culminating in the 2016 presidential election.

Taking the long view makes the rise of the alt-right look less like a unique eruption and more like a continuation of our national story of systemic racism. Historian Rayford Logan made the persuasive argument that retrenchment and the brutal reassertion of White supremacy through Jim Crow laws and the systematic violence of lynching was the White response to “too much” progress by those just a generation from slavery. He called this period, 1877–1920, the “nadir of American race relations.” And the rise of the alt-right may signal the start of a second nadir, itself a reaction to progress of Black Americans. The difference this time is that the “Whitelash” is algorithmically amplified, sped up, and circulated through networks to other White ethno-nationalist movements around the world, ignored all the while by a tech industry that “doesn’t see race” in the tools it creates.

Media, Technology, and White NationalismToday, there is a new technological and media paradigm emerging and no one is sure what we will call it. Some refer to it as “the outrage industry,” and others refer to “the mediated construction of reality.” With great respect for these contributions, neither term quite captures the scope of what we are witnessing, especially when it comes to the alt-right. We are certainly no longer in the era of “one-to-many” broadcast distribution, but the power of algorithms and cable news networks to amplify social media conversations suggests that we are no longer in a “peer-to-peer” model either. And very little of our scholarship has caught up in trying to explain the role that “dark money” plays in driving all of this. For example, Rebekah Mercer (daughter of hedge-fund billionaire and libertarian Robert Mercer), has been called the “First Lady of the Alt-Right” for her $10-million underwriting of Brietbart News, helmed for most of its existence by former White House Senior Advisor Steve Bannon, who called it the “platform of the alt-right.” White nationalists have clearly sighted this emerging media paradigm and are seizing—and being provided with millions to help them take hold of—opportunities to exploit these innovations with alacrity. For their part, the tech industry has done shockingly little to stop White nationalists, blinded by their unwillingness to see how the platforms they build are suited for speeding us along to the next genocide.

The second nadir, if that’s what this is, is disorienting because of the swirl of competing articulations of racism across a distracting media ecosystem. Yet, the view that circulates in popular understandings of the alt-right and of tech culture by mostly White liberal writers, scholars, and journalists is one in which racism is a “bug” rather than a “feature” of the system. They report with alarm that there’s racism on the Internet (or, in the last election), as if this is a revelation, or they “journey” into the heart of the racist right, as if it isn’t everywhere in plain sight. Or, they write with a kind of shock mixed with reassurance that alt-right proponents live next door, have gone to college, gotten a proper haircut, look like a hipster, or, sometimes, put on a suit and tie. Our understanding of the algorithmic rise of the alt-right must do better than these quick, hot takes.

If we’re to stop the next Charlottesville or the next Emanuel AME Church massacre, we have to recognize that the algorithms of search engines and social media platforms facilitated these hate crimes. To grasp the 21st century world around us involves parsing different inflections of contemporary racism: the overt and ideologically committed White nationalists co-mingle with the tech industry, run by boy-kings steeped in cyberlibertarian notions of freedom, racelessness, and an ethos in which the only evil is restricting the flow of information on the Internet (and, thereby, their profits). In the wake of Charleston and Charlottesville, it is becoming harder and harder to sell the idea of an Internet “where there is no race… only minds.” Yet, here we are, locked in this iron cage.

Head over to SagePub for full article

#news#white supremacy#infiltration#history#white history#journalism#tech#big tech#intersectional activism#white terrorism#state terrorism

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Power relations in His Dark Materials

TW: racism, eugenics, sexism, ableism

Spoiler warning: The main His Dark Materials novels, minor spoiler for La Belle Sauvage.

In the His Dark Materials novels power is a quite a central theme. Who has power, what do they do with that power, how can you fight power? This is of course also salient in our own world, which is why social theorists have been trying to explain power and power dynamics pretty much as long as social theory has existed. In this text I therefore want to look at some of these ways of explaining power and see if they can tell us anything about the universe of His Dark Materials (focusing on Lyra’s world). This will also dovetail with an analysis that I wrote a while back of the Nordic influences on His Dark Materials, especially regarding the history of racism and eugenics in Sweden and Scandinavia in general. Reading that text is not necessary to understand this one, but in the end of it I wrote:

Another thing I want to highlight is the comparison between the severing of children and dæmons, and sterilisation. In the books, children’s bond to their dæmons (their soul) are severed by the GOB [General Oblation Board] in order to prevent “Dust” settling on the children (Pullman 2007, 275). Dust is considered dangerous and sinful, something that according to the church started infecting humans after their fall from the garden of Eden. Sterilisation in our world, on the other hand, took place in order to make the population “cleaner” and of “better” stock. Groups who were in different ways considered degenerate were targeted, including women who were perceived as promiscuous/sexual transgressors. In Lyra’s world a spiritual connection is severed by the Church in order to curb sinfulness. In our world a biological connection is severed by “scientists” (in collaboration with the Church at times) to control sexuality and reproduction. There is a definite similarity here. (Lo-Lynx 2019)

In this text I want to further that argument by analysing the way sex, gender, sexuality and power functions in Lyra’s world. I want to thank the lovely gals over at Girls Gone Canon for helping inspire me to write both of these texts, and especially with this one because when Eliana mentioned Foucault in their latest episode a light went off in my head and I knew that I had to write this analysis (Girls Gone Canon 2019).

So, Foucault. Michel Foucault is perhaps one of the most influential theorists in contemporary social theory. His stuff props up everywhere. That unfortunately does not mean that it’s easy to understand. Here I want to explain some of his theories and concepts, and then apply them to the universe of His Dark Materials. One of the theoretical works that Foucault is most know for is his analysis of the history of sexuality (in the Western world) (2002). Foucault writes that contrary to the popular belief of sex being oppressed and tabu, people have always talked about sex, just not always outright. For instance, he writes about how admitting one’s sexual actions have become institutionalised first through confession (in church) and later by explaining ourselves to doctors/psychologists/scientists (Foucault 2002, 77). By confessing we feel that we become free, our secret truth has been let into the light. Foucault also claims that through these institutionalised confessions we contribute to the discourse about sex: “One pushes the sex into the light and forces it into discursive existence.” [my translation] (Foucault 2002, 56) Part of this discourse is that if we understand the “truth” about sex, we understand the truth about ourselves (Foucault 2002, 80). Sex is in this discourse considered a vital part of who we are. Now, what exactly does Foucault mean by discourse? Discourse, according to Foucault, describes the way society talks about a phenomenon but also how it does not talk about said phenomena (2008, 181). What is left unsaid. What is possible to say. Foucault also describes discourse analysis as a scientific method and claims that by analysing discourses one can understand why one statement was made in a situation, and not another one (2013, 31). He also claims that when we can see similarities between different statements, we can find a discursive formation (ibid, 40). Further he also writes that when analysing discourses, one should analyse who speaks (who has the authority to speak), from which institutions the discourse gains its legitimacy, and which subject positions individuals are placed in (ibid 55-57). Which position a subject is placed in effects their ability to inhabit different spaces (ibid, 58). Now, in his writing about discourses, Foucault mostly saw power as something unpersonal. Power existed in power relations between individuals in the discourse, and the discourse affected how individuals acted. Power as something unpersonal was a view that he kept, but in later writings he would analyse it further.

So, how does this apply to His Dark Materials? Like I explained previously, I see a definite parallel between how the Church/the Magisterium in Lyra’s world approach Dust, and how sex has been viewed in our world. The Church explains Dust by linking it to original sin. In their version of the Bible, when Adam and Eve eat from the apple of knowledge, they do not only become aware of their nakedness, their demons also settle (Pullman 2007, 358). And when demons settle (in puberty) Dust starts sticking to people. This can be compared to how the church of our world during the 5th century started propagating that the reason for human’s expulsion from the garden of Eden was because they had fallen prey to carnal desire (Mottier 2008, 19). Therefore, intercourse was tainted by original sin. In this way Dust is both linked to forbidden knowledge, sex, and sin. Like sex in our world, Dust is something that the Magisterium feel the need to investigate even though they find it dangerous and sinful (Pullman 2007, 361). If we use Foucault’s theory here, this is understandable. If Dust is a result of original sin, then it explains the inner nature of humans. Just as sex is considered to be a secret truth inside of us, Dust can be considered the same in Lyra’s world. Dust is something sinful, something that needs finding out, so it can be destroyed. But, when the scholars of Lyra’s world investigate Dust, they need to be careful to not commit heresy. I think heresy in this case could be considered to be the limit of the discourse. When scholars and others discuss matters of science and theology, they constantly need to act in relation to what would be considered heresy. Now, in our world the limits of discourse usually aren’t as overt, and at least in democratic countries you won’t be punished in the way the scholars risk being punished when they commit heresy. But in the way certain characters challenge the discourse around Dust, we can see what Foucault might call a discursive struggle. On one hand we have the discourse around Dust that gains its legitimacy from the Magisterium. On the other hand, we have challenges to this discourse from for instance Lord Asriel. He doesn’t have the same sort of legitimacy as the Magisterium of course, but in the beginning of The Golden Compass when he has his presentation at Jordan Collage, he tries to make his views legitimate by presenting scientific evidence (Pullman 2007, 26). Here one could say that he tries to appeal to the legitimacy of science, which seems appropriate when talking to scholars. Asriel here resist the power that be (the Magisterium), but he also resists the power in the discourse. Just as Foucault says, where there is power there is also resistance. It is through just these kinds of discursive struggles that Foucault sees society changing. Yet, the scholars of Jordan are notably scared of the Magisterium finding out about their part in this resistance. This leads us in to another theme in Foucault’s writings that I want to explain: surveillance.

One way that Foucault furthered his theoretical exploration of power was through did his writing on surveillance. He explains how surveillance works in modern society by likening it to a prison where one guard can observe all the prisoners from a guard tower, but where the prisoners can’t see the guard (Lindgren 2015, 357). Therefore they can never know when they are under surveillance. He calls this a panopticon, based on the description of such a prison by the philosopher Bentham. Foucault claims that the result of this is:

Hence the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce the inmate in a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action; that the perfection in power should render its actual exercise unnecessary… (Foucault 2012/1975: 315)

That is to say, the prisoner feels like they are constantly under surveillance, even if this is not actually the case. In that way the prisoner will obey the powers in charge, so that practical/physical power is not necessary. Foucault claims that this is the case in society as a whole; we know that we could be under surveillance all of the time, and therefore we behave in accordance with that (Lindgren 2015: 359). This turns us into docile bodies that can be used productively in society, since we unconsciously behave like the power wants us to (even when the power isn’t a clear individual or group). Other writers have also used Foucault’s theory on surveillance and his concept of docile bodies to analyse how this affects the gendered body, specifically the feminine body (Bartky 2010).

In Lyra’s world this surveillance is perhaps even more overt than in our world. People are seemingly very aware that their every move could be watched by the Magisterium. This theme is even more present in Pullman’s novel La Belle Sauvage that also takes place in Lyra’s world (Pullman 2017). I won’t spoil that novel too much, so I won’t go into that theme further now, but parts of it very much paints society as a panopticon. Now, what consequences does this have? Well, it mostly makes most people in Lyra’s world just go along with what the power wants. Some does it because they are aware of the constant surveillance, others have internalised this surveillance and does it unconsciously. One aspect of this that I want to explore further is the way it effects gender and gender expression in Lyra’s world. In the chapter in The Golden Compass when Lyra first meets Mrs Coulter, she contrasts Mrs Coulter to other women academics that she has met (Pullman 2007, 69). In comparison to them Mrs Coulter seems refined, glamorous, precisely what a woman in Lyra’s world should be. Women should be pretty, and, tellingly Lyra thinks the female scholars are both boring and less fashionable. The materiality of the body is here connected to other assumptions of gender, such as women scholars being less accomplished than men. In the patriarchal world of His Dark Materials, women who try to integrate themselves in male institutions are very frowned upon. Later, in The Subtle Knife, when Lyra has learned that all that glitters isn’t gold (such as golden monkeys), she still has this internalised view of what a women’s body should be like. When she has to find new clothes to wear and Will suggests some pants she refuses, claiming that girls can’t wear pants (Pullman 2018, 56). Here she has internalised the surveillance of the power structure that effects how women will behave. No one from Lyra’s world is there to tell her that she, as a girl, can’t wear pants, she monitors her own behaviour. This is just one example of many where one can see how the constant surveillance makes people in Lyra’s world, just as our own, internalise that surveillance.

One final part of Foucault theories that I want to explain is the concepts of biopower and biopolitics. Foucault writes that while at previous times in history regents such as kings and queens have had the power over their subjects’ life or death directly (such as by capital punishment), today the state’s power more lies in the power to support lives or let them perish (Foucault 2002, 137 & 140). He describes our current time as one of biopower, where the state controls our bodies to make them as efficient/productive as possible for capitalism (ibid, 142). Foucault also writes that because of this, norms has in part replaced the law, or rather that the law has become the norm, and therefore people doesn’t always have to be threatened by legal consequences in order to behave (ibid, 144). A state that wants a productive population doesn’t want to have to threaten them with death every time it wants to control them. This can obviously also be thought of in terms of the panopticon and surveillance that I described above. But Foucault also writes that since sex is considered so important in society, that is also one of the most controlled things (ibid, 146). This control takes place both on a micro level by doctor’s appointments, psychosocial tests etc, and on a macro level by statistical measurements etc. If this sounds similar to the way eugenics tried to control the” health” of the population, that is no coincidence, Foucault cites this as the most extreme example of these biopolitics (ibid, 148). It might also be worth noting here how other theorists has expanded this by writing about for instance “the bio-necropolitical collaboration”, and how inclusion or exclusion of certain bodies/people in society indirectly produce life and death (Puar 2009). Certain bodies get support to live and thrive, while other bodies (such as disabled bodies or bodies from the global south) is not considered worth to invest in.

Now, if we have established the link between Dust, sex and sexuality, then we could apply Foucault’s analysis of biopolitics on the Magisterium’s attempt to control Dust. In the Golden Compass we can see this through the General Oblation Board’s work on severing children, to make them not infested with Dust (Pullman 2007, 275). Like I’ve previously mentioned, one can see a link here to sterilisations, one extreme form of biopolitics that are aimed at controlling the sexuality of the population. It is also interesting to note here which children, which bodies, are being experimented on. Like I established in my other analysis, this is mostly lower-class children and children of ethnic minorities. This seems like a clear example of how the bio-necropolitical collaboration that Puar writes about decides which bodies should be protected, and which are disposable. Another example of biopolitics can be found in The Amber Spyglass when The Magisterium tries to prevent Lyra from being an Eve 2.0. Like Mrs Coulter says:

My daughter is now twelve years old. Very soon she will approach the cusp of adolescence, and then it will be too late for any of us to prevent the catastrophe; nature and opportunity will come together like spark and tinder. (Pullman, 242)

They need to control Lyra’s blossoming sexuality in order to control Dust, and the possibilities of free thinking. Mrs Coulter prevents The Magisterium to take control over Lyra, because as she says:

If you thought for one moment that I would release my daughter into the care, the care! , of a body of men with a feverish obsession with sexuality, men with dirty fingernails, reeking of ancient sweat, men whose furtive imaginations would crawl over her body like cockroaches, if you thought I would expose my child to that, my Lord President, you are more stupid than you take me for. (Pullman, 243)

Here we again see the connection between controlling Dust and sexuality, specifically female sexuality. Such a focus on female sexuality often existed within our world’s eugenics as well, since women were often seen as the reproducers of the nation (Mottier 2008, 90). Statistics show that 90% of sterilisations being carried out was on women in both Switzerland and Sweden. As Mottier writes:

Female bodies were a particular source of eugenic anxiety, as indicated by the gender imbalance in the removal of reproductive capacities. Reflecting traditional associations of reproduction with the female body, women were also seen as particularly important targets for the eugenic education and state regulations that eugenicists called for. As sociologist Nira Yuval-Davis has pointed out, ideas of the ‘purity of the race’ tend to be crucially intertwined with the regulation of female sexuality. (Mottier 2008, 92)

That it is specifically a girl’s sexuality that the Magisterium wants to control seems depressingly fitting in this light.

So, in conclusion we can see that the Magisterium considers Dust to be something that needs to be controlled. This partly happens through discourse, partly through surveillance, and partly through biopolitics. In many ways we can see how this parallels the way sex/sexuality is conceived in our world. Now, I’m not sure how much of this was deliberately put there by Pullman. Perhaps he didn’t intentionally make Dust a metaphor for sex/sexuality. But the way he connects it to original sin, puberty, temptation etc, makes me think that at least some of it was on purpose. Lyra’s world is not that different from our own after all.

References

Bartky, Sandra Lee. (2010). “Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Pathriarcal Power.”, pp. 64-85 in Weitz, Rose & Samantha Kwan (eds). The Politics of Women's Bodies, New York: Oxford University Press.

Foucault, Michel. (2002/1976). Sexualitetens historia 1: Viljan att veta. Translated by Birgitta Gröndahl. Göteborg: Bokförlaget Daidalos AB [This is the Swedish translation of L'Histoire de la sexualité I : La volonté de savoir/ The History of Sexuality I: The Will to Knowledge]

Foucault, Michel. (2008). Diskursernas kamp. Eslöv: Brutus Östlings bokförlag Symposion.

Foucault, Michel. (2012/1975). ”Discipline and Punish”, pp. 314-321 in Calhoun, Craig, Josepth Gerteis, James Moody, Steven Pfaff & Indermohan Virk (eds), Contemporary Sociological Theory (3rd edition). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Foucault, Michel. (2013/1969). Archaeology of knowledge. New York: Routledge

Lindgren, S. (2015). ”Michel Foucault och sanningens historia”, pp. 347-372 in Månsson, Per. (eds.), Moderna samhällsteorier: Traditioner, riktningar, teoretiker (9th edition). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Lo-lynx. (2019). “The Nordic influences in His Dark Materials” Accessed: December 1, 2019. https://lo-lynx.tumblr.com/post/189230180712/the-nordic-influences-in-his-dark-materials

Mottier, Véronique. (2008). Sexuality: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Puar, Jasbir K. (2009). “Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility and capacity,” Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory, 19:2, 161-172

Pullman, Phillip. (2007/1995). Guldkompassen. Stockholm: Bokförlaget Natur och Kultur [this is the Swedish translation of The Golden compass]

Pullman, Philip. (2018/1997). The Subtle Knife. New York: Scholastic.

Pullman, Phillip. (2001). The Amber Spyglass. New York: Random House.

Pullman, Phillip. (2017). La Belle Sauvage. New York: Knopf.

1 note

·

View note

Text

So I’m late on a proper New Year’s post, but one of my things (I’m not doing resolutions this year, I’m doing “things I’d like to try”) is not guilting myself as much when the schedule for something non-urgent shifts around. I had family over, then I headed back to my apartment, and I’ve spent the last two days cleaning and organizing and then reading for class. Today is the first day of my Spring semester, so we’ll say this is a reflection post for that.

Anyway! I haven’t re-upped my intro post since I first started this blog. Under the cut, for scrolling flow purposes:

I think I’m going to stick with going by Countess for now, just because. Depending how this next semester goes, maybe I’ll use my initials later or something. My department is pretty small, and while I have a couple friends following me (hi!) it’s bc I felt comfortable with them doing so and directly gave them my url. So, doing this for a bit longer.

I’m a first year PhD student in English at a university in the Southern U.S.

I’m primarily a Gothicist, and have recently gotten more into writing about Southern Gothic, given where I’m from/where I’m going to school

On top of that, I research the current iteration of the Romance genre (which I’ve alternated between calling Contemporary Romance or Popular Romance, trying to avoid confusion with contemporary-set romance novels but also with the older connotations of capital-R Romance), but I haven’t gotten to explore that as much recently

I didn’t want to go into my full research questions here, both for the sake of space and preservation, but if anyone is ever curious, I’m always down to talk about them!

I’m the first person in my immediate family to go to grad school, and the first person in my entire family going for something Humanities-related, so that occasionally leads to some Interesting conversations with well-meaning relatives

I’m TAing again this semester and will be an instructor of record next semester, about which I oscillate from “yay!” to “yikes!” and back again on an alarmingly quick basis

In my solo downtime I watch a lot of movies, especially horror (one of my BAs is in film), play video games pretty casually, and write fiction for myself (my other BA was in creative writing).

Speaking of that, I actually applied for MFA programs my first application cycle, but had a change of heart and went the PhD route on my second. If anyone ever has any questions about that process, I’d be happy to chat.

I’m also working on cooking/baking more; mostly pastas and sweets for now, respectively, but I’m trying to expand my repertoire

On the off-chance this is helpful to anybody: I have some sort of anxiety - I haven’t been formally diagnosed, but I’ve lived with the physical symptoms long enough to know it’s definitely something of the sort. I also have shown similar tendencies in the past to OCD and ADHD, and while I can’t say for sure I have either, I’ve found tips to help cope with those have also helped me function in the day-to-day, so I try to pay particular attention to discussions about those in academia (which might, in turn, be reblogged here for my own reference).

Having discussed my Right Now, so to speak, I’d love to discuss my New Year.

A few things I’m proud of from 2018:

Briefly had a job in accounting and didn’t do terribly, which made me braver about some things I previously thought I would only ever be bad at (math, I’m talking about math.)

Actually got into grad school, finally

Relocated to a new city in a state where I’d never lived and had no family nearby, successfully

Passed my first semester (grades aren’t everything, but it’s a big deal to me)

Got accepted to my first conference (one being held on campus, but still)

Outside of academics, generally just survived what was personally a really rough year due to a perfect storm of bad circumstances

Some things I’d like to try in 2019:

Submitting an abstract to this really big conference I’m looking forward to and hopefully getting accepted

Making a point to correct my posture whenever I can - I’m a bisexual who can’t sit properly in chairs, but at least when I need to be presentable I’ll make the effort

Not talking down myself or my achievements - I have this habit of minimizing my contributions or my projects when I talk (“oh, no big deal” “I might be wrong, but”) and I need to put a stop to that, even if I’m trying to poke fun at myself. I did the work and I earned whatever I got, so while I don’t want to brag per se, I can at least stop selling myself short.

Make a point to put my phone down whenever I catch myself mindlessly scrolling or refreshing - honestly, you’d think I would have done this earlier with how annoyed I get with some of the things I read online (the fiction discourse here is less inviting than a lukewarm salad bar with no sneeze guard). I’m hoping to replace it with actually reading a few pages of a book for fun, since I don’t want to encroach on breaks with more work. Maybe I’ll actually get a whole novel read during my semester, who knows.

Finally, find more places in my new city to have fun and take more pictures - I’m normally pretty selfie-adverse, but I’d rather have bad photos than none at all.

And I think that’s a new place to leave it for now; if you read all this way, you’re a peach and I appreciate you.

Here’s hoping this is the year we finally go after everything we want, unapologetically.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

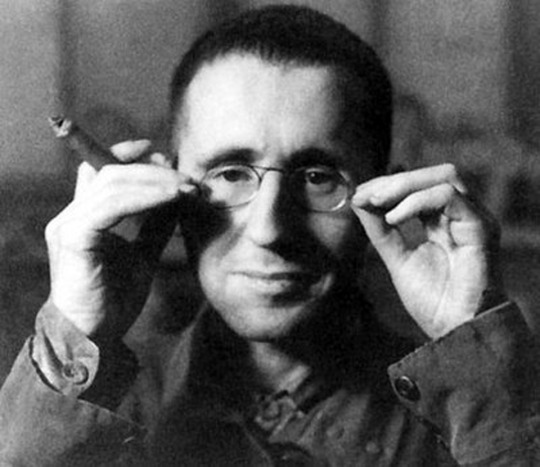

Why Brecht Now? Vol. I: Lotta Lenya sings “Wie Mann Sich Bettet”

Jonathan Shaw has been listening closely to the songs of Bertolt Brecht over the last few months. There’s no livelier contemporary observer of the rise of 20th-century fascism in Europe and — excepting the critical theorists of the Frankfurt School, especially Adorno and Benjamin — none smarter, either. Given the reactionary state of our current national and international politics, we should all be listening closely. Over the next couple of months, Shaw will write about a few of Brecht’s most incisive songs, presented in some of their most effective performances.

youtube

“Wie Mann Sich Bettet” is one of the most famous tunes from Brecht’s early collaboration with Kurt Weill, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahoganny, initially staged in Leipzig in March of 1930. The opera is set in America, likely somewhere on Florida’s Gold Coast. Florida was a strange fixation of Weimar Germany’s cultural imaginary, figuring an elsewhere of plenitude and utopian liberty. Brecht’s opera and its ruthless satire have other ideas: Mahoganny is established by a crew of stranded, fugitive gangsters. They want the town to be a pleasure pit of some renown, replete with high-end brothels, fancy saloons and casinos. The city of Mahoganny grows, populated mostly by prostitutes and schemers. And when a crew of lumberjacks shows up with cash to burn, the opera’s action takes off. The plot rapidly dramatizes a web of nasty betrayals, absurd murders and cynical excess. The song occurs near the end of Act Two, when Jim, one of the lumberjacks and the closest thing to a protagonist the opera musters, has come up short of cash after a night of revelry. He asks his sometime girlfriend and whoring sharpy, Jenny, to loan him the money. She sings the tune, giving Jim the kiss-off—and in so doing, keeping her stack of cash intact and condemning him to death.

Here’s the song’s German text, followed by an excellent and deft English translation, eventually sung by Dave Van Ronk:

Meine Herren, meine Mutter prägte

Auf mich einst ein schimmes Wört:

Ich würde enden im Schauhaus

Oder an einem noch schlimmern Ort.

Ja, so ein Wort, das ist leicht gesacht,

Aber ich sage euch: Daraus wird nichts!

Das köhnnt ihr nicht machen mit mir!

Was aus mir wird, das warden wir shon sehen!

Ein Mensch ist kein Teir!

Denn wie man sich bettet, so liegt man

Es deckt einen da keiner zu.

Und wenn einer tritt, dann bin ich es

Und wird einer getreten, dann bist’s du.

Meine Herren, mein Freund, der sagte

Mir damals ins Gesicht:

“Das Grösste auf Erden ist Liebe”

Und “An morgen denkt man da nicht.”

Ja, Liebe, das ist leicht gesagt:

Doch, solang man täglich älter wird

Da wird nicht nach Leibe gefragt

Da muss man seine kurze Zeit benützen.

Ein Mensch ist kein Teir!

Denn wie man sich bettet, so liegt man

Es deckt einen da keiner zu.

Und wenn einer tritt, dann bin ich es

Und wird einer getreten, dann bist’s du.

[Good people, my old mother tagged me

With a very unbecoming name:

I’d end up on a slab of marble

Or living in a house of shame.

Indeed, that’s an easy thing to say,

But believe me, things won’t end that way.

You can’t do that kind of thing to me!

My future remains for us to see.

A man is no beast!

We all make the bed we must lie in,

And tuck ourselves into it, too.

And if somebody kicks, that will be me, dear,

And if someone gets kicked, that will be you.

Good people, my lover once informed me—

He told me directly to my face:

That love is the only thing that matters,

That sweating tomorrow is a waste.

Indeed, love’s an easy word to say,

But as you go on aging every day

You just don’t give a damn for all that rot!

You hustle for the little chance you’ve got!

A man is no beast!

We all make the bed we must lie in,

And tuck ourselves into it, too.

And if somebody kicks, that will be me, dear,

And if someone gets kicked, that will be you.]

Lotta Lenya has long been associated with Mahoganny’s Jenny. Brecht composed “Alabama Song” for Lenya when he and Weill were experimenting with the Little Mahoganny in 1927, and the song went on to be one of Jenny’s featured numbers in Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahoganny. “Alabama Song” is justly famed, but “Wie Man Sich Bettet” packs a more significant political punch. The recording included above is from a 1955 session in Hamburg, produced by Gerhard Lichthorn, with orchestration by Roger Bean.

As with most things in Brecht, nothing in the song is simple. It’s hard to fault Jenny for her hard-hearted individualism. Life has been cruel to her; it has rendered her unsentimental and pitiless. “Love” is just another word, as meaningless as the come-ons she gives her johns (Jim included…). But it’s also bracing to hear an early 20th-century woman, relegated to bare life at the social margins, stand up for herself: “You can’t do that kind of thing to me!” She rejects her apparent feminine fatality, denying the power of public, bourgeois standards for shame. In their place, she venerates the vitality of the “hustle” and “chance.”

But those very qualities may be corrosive to her humanity. Listen to Lenya’s voice get chilly when she sings, “Ein Mensch ist kein Teir!” It’s the key phrase in the song, and her breathy cool indicates just how much Jenny’s pragmatism has undone the statement’s intended negation: she embraces the raw logic of survival, which further bestializes her. She consigns Jim to death in order that she might prosper. All the characters in Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahoganny end up alienated from one another, suspended by the opera’s end in a nefarious matrix of paranoia and mercenary impulse. Only able to perceive social relations through the distorting principal of financial transaction, the characters retreat into their separate hovels, and Mahoganny falls. More pressing, Brecht’s opera dramatizes capital’s skill at dividing the base of workers, disenfranchised lumpen, petit bourgeois schemers and otherwise abject populations, one from another—to keep them fighting over scraps while the real wealth concentrates ever more effectively in the hands of a distant, relative few. That’s the real tragedy of Jenny’s song. She only understands that “someone gets kicked,” that in her world someone must get kicked, and it’s better if it’s not her.

It’s likely that Brecht set the opera in America for satiric reasons. Weimar Germany teetered on the knife’s-edge in 1930, having already endured years of runaway inflation and crippling unemployment. When U.S. banks were rocked by the collapse of 1929, the reverberations extended to Germany, made dependent by the Dawes and Young plans on American financial largesse. Also in Germany’s 1930 elections, the Nazi party won nearly 20 percent of the seats in the Reichstag, increasing their number of representatives from 12 to 107. Ever the keen social analyst, Brecht saw the relations among disastrous financial speculation (it’s never a good thing when the stock market is the principal engine of the economy…), consequent geopolitical instability and the rise of fascism.