#white clapboard church

Text

Winter in Norwich, Vermont

1 note

·

View note

Text

Western AU snippet? Western AU snippet.

The convent lay five miles north of Chinook. Ava went for a first pass in the daytime, to mark the route in her head, and found it interrupting the expanse of plain with nothing before it, nothing after it, and nothing to either side but for a herd of bison grazing in the distance and a few patches of scrub.

An eyesore, in Ava’s opinion. Back in New York, she’d seen the grand catholic churches with stained glass adornments and naves filled with gold and precious stones.

There were no such luxuries on the frontier. Of the two buildings that stood huddled together, one was four-stories with white clapboard where the nuns slept, and the other was smaller with a steepled roof. The church.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rainy Hyades and Desert Hills

My 2023 @inklings-challenge entry for Team Chesterton!

Frankly I kind of hate this piece; it was planned to be part 1 of 3 but it is not working out at all. I'm glad I participated this year, though, even if intrusive fantasy is far from my preferred genre. Father Rivas is a recurring character of mine; people who've read any of my other horror writing set in modern-ish times might recognize the name.

---

The church is on the edge of town, with only a small parking lot and an old wire fence separating it from the sagebrush flats and the grit-red hills beyond. March came in warm this year, and rainier than usual, the storms carving divots of silver water into the gritty earth. Little pockets of scarlet and orange flowers grow in the shadows of the desert hills, half-hidden by the gray spines of sage.

Stations of the Cross are over, and the following fish fry is winding down in the dim evening light. Overhead, the steel-blue sky plays reluctant host to a spangling of early stars.

Father Rivas leans back against the clapboard side of the little church, keeping a sharp eye on the little groups of children playing in the lot. The adults are clustered around the grill and picnic table, the murmur of voices crescendoing now and then in laughter. A few beers were briefly brought out and shooed away– it is still Lent, after all. Almost Laetare Sunday. (Laetare, Jerusalem.)

Rivas is still a young man, but his back gives him trouble. The priest’s lanky frame can usually be found leaning on something, propped up at an angle like an abandoned scarecrow in black. He doesn’t miss much, despite preferring the company of the desert to that of his congregation. It’s been almost six years since he came out here; not far from his hometown, but smaller. A municipality and not a proper town, constantly threatened by the red-gold desert grit and the encroaching tumbleweeds. He likes it out here, even if he has to chase snakes and scorpions out of the sanctuary from time to time. The people are nice, but they don’t mind too much if you spend a lot of time staring out across the sagebrush flats, or if it takes a few tries for you to answer when you’re spoken to.

“Eden,” he calls warningly, as one particularly tall girl breaks away from the others and heads for the fence, “Be careful out there. Darkness sets in fast out here.”

Eden turns to look back at him, her amber eyes catching flame off of the single yellow porch light in front of the church. She leads most of the children here, and often leads them into trouble– though in fairness to her, they’re usually long out of the trouble by the time any grown-ups catch on. She’s clever, and unfortunately knows it.

“Rest assured, I won’t go far,” she says lightly. “But the starlight’s bright enough for me. I have good night vision.” She hops over the fence, and Rivas starts splitting his attention between her and the other children. A few of the younger kids run up to the edge of the fence, grabbing onto the old wooden fenceposts, and he sighs and disengages himself from his comfortable wall to go pick up Jasper, age four, and return him to the circle of porch-light.

From what he understands, there’s been a schism of sorts in the children over the last few months. Perhaps it started earlier, with the summer baseball team (the Woodpeckers.) Some of the boys from the baseball team have started their own little operation, with a base built somewhere out in the desert. Seems that Eden takes this as an insult; she’s been getting into fights with their unofficial leader, Asher. Both of them were dragged to Confession a few weeks ago after an incident with a baseball bat.

What is she doing going out into the desert at night?

There’s a bright flash of light overhead, and a shooting star– a low-flying airplane– a white bird burning– arcs across the sky, stunningly blue-white. Rivas barely has time to track it across the firmament before it strikes the horizon, afterimages blurring his vision in its wake.

“What was that? Did you see that?” calls Eden, running back towards the fence. He blinks a few times, the bruise-bright echo of light fading off of his eyelids. He takes a deep breath, the sharp smell of sage and dry earth.

Eden, her hands full of cicada shells and bone. The light of the porch reflects off of her startled face. “Was that a plane, Father? Should we go look?”

“I don’t think it was a plane,” he says, recovering himself a little. His back aches. “It looked like a meteorite to me.”

“If it was a plane that crashed, you might have to give people Last Rites,” she pursues.

“We would have felt the impact if it were a plane, or heard it.”

Eden frowns and looks back across the sagebrush flats, tucking her handfuls of cicada-shells into the pockets of her skirt. Something is building behind her face, clever-eyed, thin grim mouth. But then again, it always looks like there’s something building there.

The night grows deep, and parents collect their children and start home. The cicadas scream sporadically in the sagebrush flats, underneath their blanket of stars. “Hey, Father,” says a voice at his shoulder. Asher, with a pile of dirty paper plates in his hands. “We thought we’d stay and help clean up.”

Asher has a round freckled face and wears an outsize leather jacket whenever he can, even over his church clothes. He’s got one of the other boys with him; Cody. Black hair, dark eyes, big smile.

“Thank you, boys.”

“What’d you think about that falling star? Do you think there’s any of it left?” Asher’s bottle-green eyes are bright. He doesn’t look down at his hands at all as he works. “I bet Eden’s gonna want to give it to the Professor, but we think it should go in our museum.”

Rivas ties off the trash bag and heaves it into the dumpster. “Your museum?”

“Well, more of a collection. All kinds of cool stuff from nature and the desert, like skeletons and geodes. But it’ll be cooler than the Professor’s stuff, because he never lets anyone touch his things and they’re all hidden away in boxes. Like a museum for real people.”

“...All museums are for real people, Asher. Dr. Kaestner has a personal collection that he sometimes lets you kids look at.” He sighs and rubs his shoulder as a new twinge of pain goes down his shoulder and spine. “It’s good to have a collection of interesting things; I had something like that when I was a boy. It was mostly eggshells.”

Asher looks around. “Well, it looks pretty clean here,” he says, putting his hands on his hips. “We’re gonna head out. See ya, Father.”

“It’s long past dark,” says Rivas dubiously, looking up at the starry sky. The silver haze of the Milky Way can be seen dimly at the top of the sky, softening the hard, bright edges of the stars. When he looks down again, Asher and Cody have already scrambled over the fence, pushing through the gray-green sagebrush and scaring cicadas into the air. Cody sweeps a flashlight through the air, carving a blinding yellow path in the dark.

Unlike Eden, most of the Woodpeckers don’t have parents who will miss them out past dark. He paces at the edge of the fence, chewing on the inside of his cheek. When he looks out after the boys, cresting a hill and disappearing into the sharp shadows of the sage, he sees something shining on the horizon.

There is a great light and a soft wind out of the desert, and before he knows it he’s managed to scale the old fence, cattle wire snagging on the edge of his cassock, and headed off after them.

The light is almost blue, very pale, and would be too faint to see if it were not long past dark, but here, in the desert, in grit and darkness, in the balsamroot and sage and tufted desert grasses, he can see it. Almost like a second dawn. The light reflects gently on the narrow spearhead leaves of sage. The wind smells fresh-made tonight, sharp with the smell of distant juniper trees and quite cold for this time in the spring.

“Boys,” he calls warily, “Slow down. We don’t know exactly what it is.”

The trepidation in his voice makes Cody stop, catching at the sleeve of Asher’s oversized jacket. “We’d better wait,” he says, slowing down.

Asher sighs, climbing up onto a lichen-covered boulder to survey the landscape. His head is framed by a bright crown of stars, the face itself in a dim blue shadow. “I want to beat Eden there,” he says, scuffing a foot on the rock. “She’ll take all the magic out of it.” His sneakers are taped up with duct tape to hold the soles on; Rivas remembers that he needs to scrape together the money to get new shoes for the kids. Asher, Cody, Cody’s little sister Nina…

“Meteorites don’t glow like that,” says Rivas, squinting at the light. He thinks, now that they’re closer, that it’s coming from a cleft between two hills, some half a mile off. A small worry squirms in his gut. “It could be radioactive, or something.”

“You can feel it, though, can’t you?” asks Asher, sitting down on the boulder and sniffing the air like a dog. “The wind smells like it’s from another world, or something out of a myth. Surely it’d smell different if it were a bomb or something.”

“It’s not radioactive,” calls Eden. “Sillies.”

Rivas turns to see her picking her way across the sagebrush flats, holding up a plastic box that ticks sporadically. “Is that a Geiger counter?” he demands.

“I borrowed it from the Professor,” she says, with a sniff. “Father, what are you doing out here? This is our business.”

“No, it’s not. You’re thirteen.”

“I’m fourteen,” says Asher. “C’mon, Cody, let’s go.” He grabs the smaller boy and starts marching off. In places, the sagebrush is over the boys’ heads, and Asher has to use a stick to beat his way through it.

Rivas looks down at Eden. “Did you steal that?”

“...I plan to give it back,” she says, tossing one dark braid over her shoulder. She holds it up and starts walking, keeping a careful eye on the meter. “If it does start clicking more you should shout for the boys; they won’t believe me if I tell them.”

It’s a long walk, pathless through the sagebrush flats. The ground between the bushes is mostly bare, flecked here and there with flowers and wild, tufted grasses. The ground is gritty and flecked with small flakes of mica here and there that sparkle on the ground like another set of stars. Rivas mostly keeps his eyes turned downwards, focusing on keeping his footing without stepping on any scorpions or snakes that might still be out so late or tripping over the protruding roots. His shoes crunch in the rough sand as he follows Eden down a narrow cow-trail, into the sloping valley between hills.

“Father? Father?” calls Asher, from ahead. There’s a note of panic in his voice; Rivas’ head snaps up, and he starts to run.

“Asher? Are you boys hur–”

There is a crater at the impact site, dark spines of vitrified sand rising from the edge of the pit. The sagebrush around it has been singed and blackened, the sand and gravel piled in echoes of shockwaves,

and in the center of the crater,

there is a small girl.

She can’t be older than seven or eight, and her hair is ashen blonde and glowing. Her skin is pale, tinged with blue at the lips and on the fingers, and she has no clothes except for the grit and ash that covers her body and the long, shining curtain of her hair.

Her eyes are mirrors, dragonfly-faceted behind a mask of ash.

“...She must have come from the sky,” says Eden, scrambling down into the crater, and holds up the Geiger counter. The clicks become slightly more pronounced; a slow heartbeat. The girl turns to look up at her, shuffling away a little as Eden begins to chatter– switching languages every few words, English to Spanish to broken Navajo.

“Get away from her,” Asher snaps. “Look, she doesn’t understand what you’re saying.”

“She must understand something,” says Eden. “Father, you know Latin, right?”

“Why would she know Latin?” demands Asher. He shucks off his jacket and tries to give it to the girl, who switches her mirrored gaze over to him as the jacket falls limply onto her lap. He sighs and picks it up again, trying to wrap it more closely around her shoulders.

“She might be an angel…”

Rivas’ thoughts spin frantically, trying to figure out what to do. She looks like a little girl, surely, and not an angel. He feels like an angel should be older. What if someone comes looking for her? The second, more worrying question– if something comes looking for her?

“Hello,” he says, and swallows hard. He smiles weakly.

“Are you a Night Warden?” she asks. Her voice is high and slightly accented, the formal speech of a young child who hasn’t quite learned how tone works. “Can you help me find my mama?”

It’s a slight shock to hear her speak, but the relief more than makes up for it. She can understand him. “I’m a priest,” he says, squatting at the edge of the crater. The wind is cold, but he can feel heat radiating from the sand. Good thing it took them a little while to get out here, or Asher and Eden would have been badly burned. “Where did you last see her?”

“...In the garden.”

He probably should have expected that line of questioning to be less than useful.

“We could take her back to our base,” says Eden. “In the auto junkyard. We have sleeping bags there for when we go stargazing, and none of the adults would find out about her; this doesn’t seem like something the adults should know about. They might call…the government.” Her bright amber eyes flick up towards Rivas, weighing him thoughtfully.

“I don’t think Father Rivas counts,” Cody stage-whispers. “Right?”

Asher gently takes each of the girl’s arms and pushes them into the sleeves of the coat, which comes down past her knees. “She’s about the same size as my sisters,” he observes, fastening a button to hold the coat in place. The girl reaches out and touches his face with a small, silver hand. “Eden, you won’t tell the Professor, will you? Even if we do bring her to your base?”

She shakes her head grimly. “We’re going to have to carry her back,” she says. “The cheatgrass and sage are going to cut up her legs otherwise. How do shifts sound?”

Rivas’ forehead furrows. “I should carry her,” he says, and is met with three flat stares.

“Your back, Father,” says Eden.

“She’s not very big, we can do it,” Asher says with a wave of his hand. He looks almost unfamiliar without his jacket on, in a slightly oversized blue t-shirt and nervous goosebumps covering his bare arms.

“Fine, but I’ll carry her first,” Rivas concludes. “And we’re taking her to the church, not the junkyard. Cody, Eden, do either of you have any little girls’ clothes at home?”

Eden nods.

He approaches the girl carefully, becoming aware that the sand in the crater is almost painfully hot. It’s a good thing it took them a while to get out here, otherwise he’d certainly be burning his hands right now. The wind is still cold. “Let’s get you somewhere inside, okay?” he says to the girl, putting on a friendly smile. “What’s your name? Do you want something to eat?”

She touches her lips hesitantly and nods. “Heliaca.”

It’s a long walk back. The girl Heliaca gazes up at the moonless sky the whole way, her dragonfly eyes tracing the milky way. She seems unbothered by the sharp, thin twigs of the big sagebrush scraping against her bare legs.

They make a line against the sky as they trek along the ridged earth, gravel and sand shifting beneath them. Rivas, and then Eden, tall and lanky, and Asher, smacking his arms to keep warm, and Cody trailing a little behind to pick up pebbles. The girl, shining, outlines their silhouettes in liquid silver.

Eden breaks away at the edge of town. “I’ll go get her some of my old things; I can get in and out without my dad noticing,” she says, scrambling up and over the fence and taking off down the road. “He shouldn’t be back from his shift yet, anyway.”

Asher jogs after her, his duct-tape sneakers snapping against the asphalt.

“...I guess they’ll be back soon,” says Rivas to Cody.

The younger boy nods, his dark hair flopping down over his eyes. “Can I have a snack, too?”

“I’ll see what we have.”

They have chocolate-chip granola bars and juice boxes in the church basement, as it turns out. Also, a couple of very crushed fruit rollups, a clementine, and a rather stale loaf of whole wheat bread, which Rivas decides to throw away. These must be leftover snacks from the last time 4-H was in here.

He sits Heliaca on the floor and puts an unwrapped granola bar into her hand. “Cody, can you help her with the juice box? I’m going to go make some tea, or hot cocoa or something.” He feels the urgent need to make something with his hands, to shoo away the worries that are building in his head.

What’s going to come after her? Ordinarily he’d laugh at Eden’s whisper about the government finding out; she picked that up from her parents, a parroted turn of phrase. She might not actually be wrong this time, though. There’s bound to be some investigation, even a small one, and their footprints are all over that impact site.

He rubs his aching shoulder absentmindedly and leans against the small kitchen table in the rectory as the teakettle boils.

And what about that mother? If she does come after the girl, will she be like a human?

What if she doesn’t come at all?

The whistle of the teakettle makes him jump. He pours the water into five mugs of varying sizes, digs out honey and packets of creamer and tea. When he gets back to the basement, Asher is back with a pile of clothes.

“Eden’s dad got home early, so she had to go to bed,” he explains, sifting through the rumpled pile. Underwear, mismatched socks, a couple of dresses and a rather faded sweater that Rivas remembers Eden wearing constantly when she was ten or eleven. “I brought all the stuff, though. I was worried she might snitch, but it seems like she really wants to keep this quiet. Helps that the Professor is probably asleep.”

Heliaca, sucking quietly on a juice box, examines the clothing.

“Don’t you know how clothes work?” asks Cody. He starts pouring honey into his mug of hot water until Rivas reaches over and wrestles the squeeze bottle away from him.

“I know,” she says, putting down the juice box and picking up a sock. “I’ve seen Earth people wear all these things. I’m just not normally so small.” She pulls the sock on, upside-down, and then puts a second one on correctly. “You have so few hands,” she adds casually, which is a little worrying in implication.

“Hey, Father, can I have the honey?” asks Asher, leaning over to try to take the bottle out of Rivas��� hand. He, at least, has actual tea steeping in his cup and not just boiling water.

“Yes, fine.” Rivas is picking up one of the dresses to hand to Heliaca– she can’t keep wearing Asher’s coat forever, after all– when a sharp knock sounds on the door upstairs.

Not likely to be continued. But maybe; if I do continue it I'll put links to the other parts down here.

#inklings challenge#inklingschallenge#team chesterton#genre: intrusive fantasy#theme: clothing#story: unfinished#theme: food

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

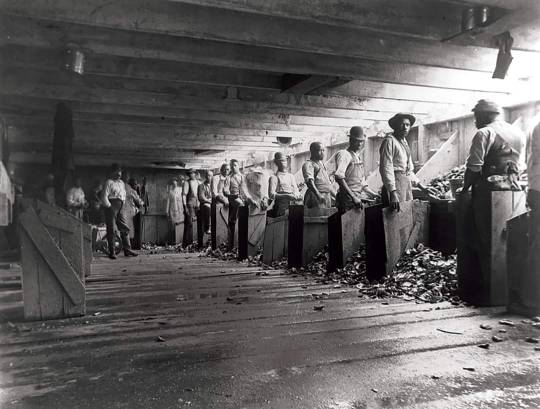

[from my files]

* * * *

A Walk to Sope Creek

by David Bottoms

Sometimes when I've made the mistake of anger, which sometimes

breeds the mistake of cruelty, I walk

down the rocky slope above the ruined mill on Sope Creek

where sweet gum and hickory weave sunlight

into gauzy screens. And sometimes when I've made the mistake

of cruelty, which always breeds grief,

I remember how, years ago, my uncle led me, a boy,

into a thicket of pines and taught me to pray

beside a white stone, the way a man had taught him, a boy,

to pray behind a clapboard church.

Sometimes when I'm as mean as a stone, I weave

between trees above that crumbling mill

and stumble through those threaded screens of light,

the way anger must fall

through many stages of remorse.

Any rock, he allowed, can be an altar.

*

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Resurrection” (Ephesians 2:1)

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

For a long time the old Cape Cod style church sat in a Detroit neighborhood, empty and abandoned. White paint peeled and dropped from its clapboard siding. The decaying church blended naturally into the whole area. Party stores flourished, but little else. Storefronts were boarded up. An old school building was padlocked. Grim, unswept, forgotten – that’s how…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The story begins as Luke Chandler and his grandfather Eli, also known as Pappy, search for migrant workers to help them with the cotton picking. They initially consider themselves lucky to hire the Spruills, a family of “hill people,” and a few Mexican migrants who annually come to the area looking for work.

Aside from working long hours under the hot sun in the fields, Luke’s life is fairly idyllic. He is obsessed with beautiful 17-year-old Tally Spruill, who on one occasion lets him see her naked, bathing in a creek. But a much more unpleasant experience is seeing Tally’s brother, the overly aggressive and mentally unstable Hank Spruill, attack three boys from the notorious Sisco family, one of whom is beaten so severely that he dies from his wounds. Hank arrogantly identifies Luke as a friendly witness who can support his version of the event, and the fearful boy backs up his story, although the adults in his life, including local sheriff Stick Powers, suspect he’s too frightened to admit the truth.

When Luke sees Cowboy, one of the Mexicans, later murder Hank and toss his body into the river, Cowboy threatens to kill Luke’s mother if Luke tells anyone what he saw. Cowboy and Tally then run off together and are not seen again. Luke also learns that his admired Uncle Ricky, fighting in the Korean War, might have fathered a child with a daughter of the Latchers, their poverty-stricken sharecropping neighbors.

Grisham surrounds these dramatic moments with descriptive passages of life in the rural South and the ordinary events that fill Luke’s weekly routine. His hard work in the fields is preceded by a hearty breakfast of eggs, ham, biscuits, and the one cup of coffee his mother allows him, and at day’s end he’s rewarded with an evening on the front porch, where the family gathers around the radio to listen to Harry Caray announce the St. Louis Cardinals baseball games. A devoted fan, Luke is saving his hard-earned money to buy a team warm-up jacket he saw advertised in the Sears, Roebuck catalog. Saturday afternoons are spent in town, where the adults share idle gossip and serious concerns and the youngsters visit the movie house, while Sunday morning is reserved for church. A visiting carnival, the annual town picnic, and Luke’s introduction to television – to see a live broadcast of a World Series game – are additional bits of local color scattered throughout the tale.

A flood devastates the family’s crop before the harvest is completed, and Luke’s parents decide to travel to the city to find work in a Buick plant, breaking a history of generations working on the land. The novel ends with Luke’s mother smiling on the bus, having finally gotten her wish to leave cotton farming.

The book’s title refers to the Chandler house, which never has been painted, a sign of their lower social status in the community. One day Luke discovers that someone has been secretly painting the weather-beaten clapboards white, and eventually he continues the job with the approval of his parents and the assistance of the Mexicans, contributing some of his own savings for the purchase of paint.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pretty clapboard church in Nova Scotia built in 1792.

The doors are lovely. Maybe they were painted gray b/c they couldn’t be preserved.

This is a good conversion b/c they’re living in the nave, which is the best way to preserve it.

It looks like they added 2 rooms along the side.

Very nice kitchen. If they gave it a bit of color, it would be beautiful.

The ceiling is beautiful and there’s a full view of the choir loft.

Isn’t the dining area lovely? That would’ve been where the altar was.

The main bedroom is in the loft and there’s a wonderful view of that ceiling.

This is beautiful. The window is stunning.

The bed and shower on the main floor.

Yow! This so white! It’s the half bath. This place needs some color.

Beautiful setting. ($575k)

https://www.remaxnova.com/residential/upper-granville-real-estate/7401-highway-1-upper-granville-mls-202209728

100 notes

·

View notes

Link

SO#3: The Life Of Euronymous K. Scruggs

[By Tammy Lynn O'Hanrahan, correspondent, with the help of Francis L'kthant'gla'ftglth Smith, Esoteric Church of Starry Wisdom Historical Society]

The history of our sleepy little community is not particularly well-known outside of Scruggsdale County, Mississippi, and even life-long residents often only know the bits and pieces we remember from school. So, as we prepare to celebrate our town's 221st Founder's Day, the Scruggsdale Organizer has teamed up with the Esoteric Church of Starry Wisdom Historical Society to pen a brief account of the life of our town's founder, Euronymous K. Scruggs.

Euronymous Kal'thultra'narath'kal Scruggs was born in Clear Island, County Cork, Ireland in 1769 to his father, Jonathan Scruggs, and mother, Kalnarath of the Nameless Deep, both Roman Catholics. The Scruggs family immigrated to the newly-established United States of America in 1784 when young Euronymous was 15, fleeing unemployment and anti-Catholic persecution. After arriving in Boston, the family moved to the Mississippi Territory and established themselves on a homestead in the bluff hills bordering the Yazoo Valley, freshly stolen from the indigenous Choctaw nation. There, Jonathan grew tobacco and soy beans, and young Euronymous began a self-education in philosophy and astronomy, which would become life-long pursuits.

In 1790, a bout of fever swept through the area and the Scruggs family became very ill. Jonathan Scruggs passed away, but Euronymous and his mother recovered, with Euronymous celebrating his good health by famously declaring, "In my fevered visions I have seen untold wonders, I have beheld forbidden secrets fit only for the eyes of the gods, and in truth I have seen that they--the gods--are false, and that truth lies only in the imperishable Void. The terrible burden of this unholy wisdom consumes me, and I know that deeper secrets and more marvelous horrors await me yet, and I know this beyond a doubt: That I, having tasted death, can never die."

Later that year, Euronymous courted and wed a Baptist preacher's daughter, Miss Kelly Rosewood, and together they founded the area's first permanent religious institution, the Esoteric Church of Starry Wisdom, of which the original structure of white poplar clapboard and mysterious luminous stone still stands today on Euronymous Boulevard, across from the rec center.

More families came to the area to steal more land and establish homesteads of their own, and in the year 1799, when Euronymous was 30, the town of Scruggsdale was officially incorporated.

Shortly after the founding, Euronymous and Kelly retired from public life in order to care for Euronymous's ailing mother, who complained of "the poison light of this world's monstrous sun" and "the putrid, disgusting life of this lighted world where the cold of the Nameless Deep has never spread." During this time, Euronymous continued his studies of science and philosophy, writing books such as That Which Dwells Between The Stars, On The Summoning And Correspondence Of The Nameless Ones (volumes 1 and 2), Scruggsdale Wildflowers And Other Flora: A Field Guide, and the very well-received The Sublime Madness Of The All-Consuming Void, all of which are available in hardback, paperback, and ebook form at the Scruggsdale County Public Library.

In 1810, after Scruggsdale had grown from a loose collection of homesteads soaked in indigenous blood into a vibrant and thriving agricultural community soaked in indigenous blood and the blood and sweat of Black slaves, Euronymous announced that he planned to take a trip back to his native Ireland, stating that, "The unholy ichor of my mother's blood and the grim weight of my father's sins are burdens I may never shed, and so I shall return to the land of my fathers and, there, beg God for a death which I know will never come." He and his beloved wife, Kelly Rosewood Scruggs, boarded a ship departing from Charleston, South Carolina which foundered and went down with all hands a few miles off the coast of County Cork some weeks later. The couple were survived by twelve children who would all move away from Scruggsdale over the next several years, each citing "a nameless and all-consuming Hunger, the name of which cannot be spoken by any tongue of Men."

Our 221st Founder's Day celebration will be held next Friday in scenic Euronymous K. Scruggs Memorial Park, with an outdoor barbecue, live music, and a horseshoe tournament to mark the occasion.

***

Subscribe for early updates and special bonus content! https://www.patreon.com/natalieironside Please do, I’m gay and trans and I don’t have any monies

395 notes

·

View notes

Note

ooooh, could i combine two of those prompts? "these clothes are ridiculous" with "where's your sense of adventure?" otherwise, just one of those! :) thanks

The town is still accepting visitors when they arrive, the grassy parking lot full of eight-seater SUVs and minivans with stick figure family bumper stickers. The squeak of the car door turns a dozen longhorn heads from the paddock beside the makeshift lot, chewing grass languidly while they watch Sam and Dean organise themselves.

"Two people have died and they're still open. Talk about priorities." Sam tucks his Taurus into the back of his pants.

Dean's rummaging through the trunk for supplies, salt and holy water and split tipped bullets. There's something possessing the animatronics.

"Can you believe Bobby never took us here as kids?"

"The salvage yard is three hours away, I don't think he would have survived the road trip, let alone the babysitting,"

Knowing Bobby, he would have planted his ass in the saloon and let them off leash, two outlaw brothers strolling into town ready to wreak havoc. Babysitting is probably not the right word for it.

"You're not taking the Colt," Sam asks disbelieving, as he watches Dean tuck the long barrel into his waistband.

"Dude, it's thematically appropriate."

A woman in period-themed skirts greets them at the door, informs them it'll be twenty-four dollars for adults unless they want to stay the night in the hotel and Dean's eyes light up comically, elbows Sam in the side.

Sam forks over cash for the room. It'll be easier to do their job after dark, anyway. Dean is grinning like he can't keep it off his face and Sam's is quietly amused, figuratively patting himself on the back for finding a case so catered.

If he knew one of the conditions of entry was costume hire he might have hesitated.

"These clothes are ridiculous," Sam says, running his hands over a cheaply made bandolier with fake spray painted, foam bullets.

"Where's your sense of adventure?" Dean says, already strapping a holster to his waist, forgoing the shelf of plastic Peacemakers for the real deal.

His brother doesn't go overboard this time, gives the serape rack a wide berth. He picks an embroidered vest, tightened around the back in a way that does something to his waist. Worn over a cotton shirt, buttoned down three or four inches. It's all still terribly gaudy, but that's pretty unavoidable.

Sam lets Dean pick him a hat.

The town is honestly impressive. All original buildings, schoolhouse with desks, undertakers with a coffin lined porch, blacksmiths and horses hitched to posts where children can sit on their backs for a dollar. There's a guy performing lasso tricks in front of the white clapboard church at the end of the street.

The animatronics say their recorded lines, move in jerky mechanical shakes and Sam has to restrain himself from tugging the kids back by the collars of their shirts, installing a rope fence.

They eat in the authentic nineteenth century train carriage slash diner and wait for the sun to set so they can start the real work.

Their room is bed and breakfast style, wrought iron bed frames and crocheted quilts that look scratchy and uncomfortable. Dean unbuttons his vest, unbuckles his holster and drops it on the bed.

Sam's smiling at him from the door and Dean looks back at him confused. They'd drunk rotgut whiskey with their arms pressed together, leant heavy against the bar of the saloon and Sam has always been susceptible to impulsive decisions after being around his brother in a good mood for extended periods of time.

"You alright there, cowboy?" Dean asks him, rolling up the sleeves of his shirt.

Sam covers the distance, bats the hat off his brother's head and kisses him.

#you absolutely can but only if im allowed to use it as an excuse to make it about cowboys#my words#wincest#thank you though this prompt made me smile when i saw it#channelling that brokeback mountain post the other day#if anyone has been to 1880 town SD let me know if i did it justice#pretty sure you cant stay there but theres a cowboy town in NZ that i desperately want to go to where you can hire out the whole place#for weddings and stay overnight with 50+ guests so if any mutuals want to get gay married hmu

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is my story for the inklings Christmas challenge (@inklings-challenge)! It is almost exactly 9k words of what I think is technically intrusive fantasy; it starts during Advent in a small town with the arrival of some very odd beings. But I think to really understand, you would just have to read it. Mainly it’s a Christmas story.

Ebb of the Tide

There were a surprising number of immigrant families living on the shore. Not as many actually lived in Weston, which was a small town even by the standards of the shore, but Danielle Evans (who lived in Weston) taught in the middle school, which was a long bus ride away over the bridge, and she said some of her students couldn’t even speak English; their bilingual friends had to translate for them. She’d picked up a smattering of Spanish herself, working there, Danielle said. She’d probably said it a few times, to various acquaintances or family, but she said it again after the service on the first Sunday of Advent, at the little white clapboard Methodist Church at the high end of Hill Street, and so it was a statement that was under general discussion that Monday, outside West Point Market. There were a couple tables outside West Point Market where the retired watermen—if there was such a thing—sat and talked every day except Sunday, and except for the days when it got too cold for their hard-used, arthritic hands, when they sat inside instead.

The retired watermen, who could generally be relied on to have a finger on the pulse of the town as a whole, didn’t mind the immigrants exactly. They’d come to the shore—that broad finger of land between the bay and the ocean—in years before, to work the corn and soybean harvests, and to pick crabs in the packing houses alongside the watermen’s wives. They didn’t entirely approve of middle schoolers who didn’t speak English, though. “And they aren’t from around here,” said Buddy Evans, no relation—immediately, anyway—to Danielle. This seemed to be the long and short of it.

The immigrants didn’t seem that foreign after all, though, when the Others started arriving.

It may actually have been Tyler Caulder who saw the first Others, though his mother didn’t believe him at the time. Tyler was eight, and fanciful. “It was a silver man, like a spaceman, and his wife,” he told her when he got home, nose red with cold, from playing outside with Dickie Phillips and Brian Nelson after school. “They needed a boat.”

“And what did you do then?” said Mrs. Caulder, who was making oyster soup and could hardly see through the steam in the kitchen. “Take your boots off.”

“We took them to where the old Lady Grace is run up the marsh,” said Tyler. “They said thank you.”

“That’s too far for you to be going on your own—or with Dickie and Brian,” said Mrs. Caulder, and Tyler said, “Mom, it’s only at the end of Ship Lane,” and they argued about that for a bit, and the silver man and his wife—tall and silver, both of them, Tyler could have told her, with long faces that never quite looked the same when you glanced at them twice—were forgotten.

After that, there were more stories from children—enough to make the most imaginative adults start to look at each other, but not to say anything—and that was it; until the United Methodist Women did their Christmas cards.

Every year during Advent, the UMW baked enough cookies to feed the entire town of Weston for probably most of the new year, and then gathered in the fellowship hall of Weston United Methodist Church with their cookies and the materials to make Christmas cards, and put together boxes for the sick and shut-in parishioners. In fact, they made more boxes than there were shut-ins, but Pastor Dennis, who was young and fairly new, had learned from his predecessor, Pastor Mark, not to mention this. Somehow, by Christmas, the boxes were all disposed of, anyway.

This Advent, the UMW gathered, for some reason, on a Thursday afternoon; by the time the cookies were all boxed and the cards addressed, it was evening, and fully dark outside. “Oh,” said Helen Phillips tenderly—she was the youngest and most sentimental of the UMW—when they had all bundled up and stepped out onto the front porch of the church, into the darkness and the cold, “it’s snowing.”

It was snowing, just a little—nothing that would stick, but sparse flurries that blew around and caught the light from the outside spotlights shining on the church parking lot. Most of the other women glanced up, too, which is probably why it was Maria Guadelupe Martinez, the only Latina member of the Weston UMC UMW, who was first to spot the small group of people—beings, anyway—at the far end of the parking lot. “Oh!” she said, too, with a very different inflection. “There—there—angeles!”

Maria Guadelupe had been Catholic, a fact that she’d never talked about but that was somehow understood anyway. Helen Phillips wondered if she still considered herself Catholic; Helen didn’t think this would necessarily be a bad thing. The rest of the women generally considered Maria Guadelupe to be Methodist now, which, if they thought of it at all, they would have thought to be a kindness on their part, though Maria Guadelupe might not have seen it that way. The rest of the women now exchanged charitable glances with each other, as if to say that they didn’t think the figures in the church parking lot were angels, and even if they did, they wouldn’t have said so in a foreign language; though, since the figures almost seemed to shine with an inward light, it wasn’t as exaggerated a guess or reaction as it had first sounded.

Afterwards, the women couldn’t quite agree on how the things—the beings—had talked, or exactly how they’d looked. Betsy Evans said they had been almost transparent, like they weren’t quite there, but Rachel Caulder said they were sort of more there than the women themselves were, which was the most poetic language anyone had ever heard her use. Linda Crenshaw said they had some sort of an accent, but they spoke English well enough. They way Helen Phillips experienced it, she wasn’t sure if the beings spoke at all; she just knew that for some reason, the women approached them as a group and stood in front of them, and that sometime after getting near them, she suddenly knew, as if they’d put the knowledge straight into her head, that they were looking for a boat.

“So what did you do?” said Danielle Evans, the next day. She was one of the few women in town who didn’t attend UMW meetings—she claimed to be too busy chaperoning extracurricular activities at the school where she taught—but she’d baked some cookies and given them to Helen to bring. She’d come to Helen’s small house this Friday afternoon despite any extracurricular busy-ness, ostensibly to get her tupperware back. Now she was leaning against the counter in Helen’s tiny kitchen, arms crossed over her plastic container, showing no signs of going anywhere.

“We brought them to a boat,” said Helen. “Rachel Caulder woke up her husband.” The Caulder brothers oystered together in the winter, leaving at about four thirty or five every morning, so they went to bed early. Ryan Caulder hadn’t been happy to be woken, at first. But he’d gone out, once he came downstairs and found them all—the Others, and also most of the UMW, who weren’t going home until they’d seen this thing through.

“Where did he bring them?” Danielle asked, but Helen couldn’t tell her. Ryan had gone out with the Others, and some time later, he’d come back alone. It had been enough later that only Helen, Maria Guadelupe, and Linda Crenshaw, who’d outlived her husband and a few of her children and had no one waiting at home for her, were left waiting at the docks at the end of Hill Street; even Rachel had gone home, so that her son wouldn’t be sleeping alone in the house. But it wasn’t enough later that Ryan could have gone anywhere important; and Ryan hadn’t said anything. He’d just tied up his deadrise and gone back to bed. “What did they look like?” asked Danielle now.

“Have you seen The Lord of the Rings?” said Helen. “They were sort of like the elves from those movies. And also nothing like that at all.”

After that, the Others were all over the place. No one discussed them outright or exactly tried to catalogue them (except for Danielle Evans, probably because she taught science and believed in things like evolution, which was regarded skeptically by many older residents of Weston, and even some of the young ones). Somehow, though, everyone got used enough to talking about them obliquely that everyone understood as much of what was going on as anyone else did. There seemed to be different types of Others: there was the tall silvery type, who seemed to have a slight majority, but there were also smaller and more, almost, ordinary ones; or rather, though they were otherworldly, it was in a more down-to-earth way. There was at least one—well, family seemed the right word—of them that looked like trees, enough that Logan Nelson seemed to have a small forest growing out of the deck of his boat when he took them out. Some seemed more like animals than people; but they were intelligent enough to make themselves clear.

That was the other thing: everyone knew, pretty quickly, what the Others wanted. They usually showed up at liminal times—dawn and dusk, or occasionally when the weather shifted and got cloudier mid-day—and they were generally looking for a boat. When they found a boat—the Lady Grace, which had been sitting on mud in the marsh and hadn’t moved in years, seemed to have disappeared, so the boat was generally one belonging to an obliging waterman—they went out in it, and though the boats came back, the Others did not. It should have been sad, maybe, and there were times when the loss felt bleak; but it didn’t feel, somehow, like an exile, or like a death. It felt like Weston had found itself in the path of a migration, a natural, regular occurrence that nonetheless no one had experienced before.

Well, probably no one had experienced it before. Not within living memory. Some of the older residents of Weston were starting to remember some things, though, things that their parents had said or done. Nancy Abel annoyed her daughter-in-law, who she lived with, by insisting on putting a saucer of milk out on the back steps at night, though her daughter-in-law had to admit that the saucer was generally empty and almost clean by morning—feral cats, she supposed. Buddy Evans, somewhat sheepishly, found an old horseshoe in a chest that had belonged to his grandfather and slipped it into the cabin of his son’s workboat one morning before Jerry went out; the Others still accepted rides from Jerry Evans, after that, but it was true that they tended to stay out of his cabin. Linda Crenshaw, meanwhile, told stories of the Others she’d seen in her childhood to anyone who would listen.

This wasn’t a large number of people. Linda lived in a small, one-story house near the center of town, even though her grandchildren kept trying to get her to move to a senior living center several miles away. Her husband had died years ago; of her five children, two had also died by now, and the rest moved away, although to be fair to them, two of them had only moved elsewhere on the shore, which didn’t feel far away to them, but did to Linda, who’d lived her whole life in Weston. They, and their mostly adult children, visited every few months to try to convince her to move. Linda’s other visitors consisted of: Missy Evans (she’d grown up in Weston, too, and she and Linda had been feuding as long as anyone could remember, so they needed to get together to snipe at each other); Helen Phillips (who visited for the same reason she attended UMW meetings so regularly, which was that she was tenderhearted and felt truly guilty if she didn’t); and Logan Nelson.

Logan wasn’t related to Linda, as far as he knew, though if you went far enough back, most families in Weston were related. He wasn’t sure why he visited her; but five or so years ago, he’d noticed that the screen on her porch was coming off, and he’d volunteered to come over in the afternoons, when he got in from crabbing, to fix it; and then somehow, once it was fixed, he’d just kept coming over. He didn’t go there every day, or anything, but he generally made a point to visit about once a week. He would call Linda “Miz Crenshaw,” and fix anything around her house that needed fixing, and Linda would give Logan some baked good—these days, it was usually something store bought—and tell him bluntly that he needed to fatten up.

Logan was more wiry than many of the other watermen, who tended to run to bulk, but this wasn’t something he could change with baked goods. His father and older brother were bigger than him, too; his brother Andy in particular looked like he belonged out on the water in waterproof bibs. Instead Andy lived on the other side of the bay and wore a suit to go into an office every day, even though wearing suits made him look like he was playing dress up. Logan’s father, whose father and grandfather before him had been watermen on the shore, had retired and moved to a little fifty-plus community with his wife as soon as they had enough money saved up. And so Logan was left alone in Weston, hiring the occasional high schooler to help him during crabbing season, and tonging for oysters on his own in the winter on the boat that his father had once owned. It was hard, physical work; Logan could feel it changing his body, even though he was barely into his thirties. He couldn’t imagine ever doing anything else.

Sometimes Logan and Helen ran into each other on Linda Crenshaw’s porch, or in her kitchen, and stepped around each other awkwardly, muttering hello and goodbye, as they did their best to part ways quickly. Logan was uncomfortable around Helen, in a way that he didn’t quite like to label as nervous; she was very round and soft, in that even her nose was sort of round, and her hair tended to escape in tendrils and halo around her round face, but this wasn’t the direct cause of the nervousness; it was more that Logan could see something of the tender guilt that Helen potentially felt at all times about not Doing the Right Thing, and he worried that some of that guilt would rub off on him. Helen, for her part, could never tell what Logan was thinking—he had black hair, with a tendency to curl under his cap, and a dark, close-cut beard that nonetheless covered his face so that it always looked mostly expressionless. She thought he was intimidating. Logan would probably have been gratified to realize as much.

Linda had no compunctions about Helen’s aura of vague guilt or Logan’s aura of closed-off intimidation. And she wanted people to talk to. “I don’t think I’d forgotten them, really, but I just never thought about them—why would I?” she told Helen during an afternoon visit, not long after the UMW had done their Christmas cards and then walked out to see the Others standing in the snow. “But it’s coming back now—I must have been only seven or eight. Daddy didn’t hardly get any sleep that winter, as many runs as he made in the Ida B to bring them out wherever they wanted to go.”

Helen, alone among the UMW, did not think that Linda was making the returning memories up for clout. She told Danielle Evans about Linda’s stories one evening, tentatively. Danielle had come over to see if Helen had any extra plastic bottles she’d been going to recycle; she apparently had some sort of plan to have her students make terrariums, and was going around the town bullying everyone into giving up their plastic bottles. She’d stayed in the kitchen once Helen had handed over the bottles, though, and leaned against the counter in the same place as she’d stood last time, to chat. Helen wondered suddenly whether Danielle had any close friends among her fellow teachers at the middle school. She, Helen, considered the UMW, and Linda Crenshaw specifically, to be friends, and of course her parents lived fairly nearby, but she wasn’t sure if she had any close friends. It wasn’t that Weston was backwards, certainly, or even very old fashioned; but though there were other young, unmarried women around, by the time they hit thirty—which Helen had, and she was fairly certain Danielle had, too—they tended to either marry or move. The UMW had been dropping genial hints to Helen lately, about no one in particular. Danielle wasn’t the sort to stand around and listen to those kinds of hints, which must have limited her opportunities for friendship.

“That’s interesting,” said Danielle, when Helen had told her what Linda Crenshaw had been saying about seeing the Others when she was a girl. She really did seem interested; unlike Logan, who looked expressionless no matter what, Danielle’s square, pleasant face in its frame of cropped-short hair was blank only when she had no opinion—which wasn’t unheard of—but when she cared what Helen was talking about, she looked like she cared. “It’s as if they’re like cicadas. Or monarchs.”

Helen was uncertain about cicadas—she knew about them, she just didn’t like them. As to monarchs...she had been taking out Christmas decorations when Danielle arrived, so it was probably this, unwrapping her creche from its newspaper and setting it on her dining room table, that made her say, “Kings? Like the wise men?”

“Like the butterflies,” said Danielle, so Helen felt a little stupid, because she immediately knew what Danielle meant. Every fall, the small orange and black critters fluttered through, traveling miles and miles to their winter habitation—was it in Mexico? Like Maria Guadelupe in reverse, only she had stayed to work as a nurse at the hospital two towns over, and didn’t go back and forth the way the butterflies did. Helen didn’t mind butterflies, but they were still bugs. “Although I suppose the wise men did travel great distances, too,” added Danielle, charitably, which didn’t make Helen feel any better.

“I got mixed up, looking at the creche,” she explained.

“It really is more like the cicadas,” said Danielle, “if this only happens every—seventy years or so. I wonder if there would be records, if we looked farther back.”

“Danielle,” said Helen, bravely, thinking of the way those Others in the church parking lot had looked, close-to, and the way Maria Guadelupe had crossed herself surreptitiously when she’d approached them, “I don’t think everything needs to be science.”

“Everything is science,” said Danielle; “some of it we just don’t understand yet.” She seemed to see how uncomfortable this made Helen, because she smiled in a way that was trying very hard not to look mocking. “I don’t mean I don’t believe in God,” she said, “although I know that’s what some of the people around here say about me—you see me at church, don’t you? I don’t say it to my students, but—the more I learn about science, the natural world especially, the more I do believe in God. Knowing how some of the processes work almost makes them seem more miraculous, not less.”

This was a lot for Helen to try to take in; Danielle must have realized this, because she left shortly after, leaving her to think. Helen hung some fake greenery around her windows, and set up her creche on her TV cabinet, where it always went. She looked at the worn baby Jesus, who was glued to his manger and also looked a lot more like a toddler than a newborn, and wondered. She’d read online—because she certainly hadn’t heard it at church here—that Mary and Jesus wouldn’t really have had white skin, with where and when Christ’s birth had taken place. She suspected that the blue-painted eyes of her Christ child were inaccurate, too, if that was the case. She thought a brown-skinned version of the Holy family might not be too bad—it might even be nice looking. But Helen wasn’t going to trade her parents’ old drug-store purchased nativity set for a new, more accurate one; and she couldn’t make herself think that God would mind.

Logan Nelson didn’t own any personal Christmas decorations. He rented a room at Betsy Evans’ house—about half the people in Weston were Evanses, without really being related—and helped her hang the Christmas lights out front each winter on the Monday after the first Sunday of Advent, his only stab at festivity. This winter, on the Wednesday after the second Sunday of Advent, he came downstairs from his rented bedroom, drank his coffee and ate a cold toaster pastry in the dark kitchen, put on his bibs over the three layers of clothing he already had on, put on his coat, put on his winter hat, put on his boots, put on his first layer of gloves—he’d add rubber ones, on the boat—and picked up the lunch he’d packed the night before, before heading out to get in his truck and drive the three blocks to the end of Hill Street where the docks were.

In fact, this was the routine he’d followed every morning that winter—except Sundays, because although Logan was ambivalent about spending every Sunday morning at church, he knew he wouldn’t be able to survive the blow to his reputation that would happen if he didn’t. Literally, probably, because he stuck most of his crabs and oysters on old Bert Evans’ box truck to be sold at restaurants and packing houses along the shore, and if Bert’s wife decided Logan was godless and immoral and they didn’t want to associate with him, well, he’d lose his only way to make money. But this Wednesday morning, it was business as usual; until he got to the slip where the Mary Anne was waiting for him, with a light on in the engine box so the diesel wouldn’t get too cold, and saw the not-quite-human figures waiting for him there.

Logan had taken a few groups of the Others out, by now, including that group that had looked kind of like trees. He hadn’t told anyone what it had been like, but where the other watermen hadn’t told anyone what it had been like because they seemed to regard it as some sort of secret ritual they’d taken place in, Logan just didn’t have anyone he wanted to tell. It hadn’t been exciting; mostly it had been a little sad. With each group, he’d taken them out into the bay about as far as he ever went, at which point he would become aware—usually while he was squinting at the water ahead of him—that he was alone on his boat. Then he would turn around and come back. It wasn’t like the Others jumped overboard; Logan would have noticed that. They just seemed to need a lift to a place where they could then go somewhere else.

The group on the dock this morning were some of the smaller, less majestic Others. It wasn’t actually a group, Logan realized as he got closer—it was just a pair. It was hard for him to look at them straight-on; out of the corner of his eye, he could tell, somehow, that it was a man and a woman. Not all of the Others had seemed to fit into gender categories, which, amusingly, the older folks of Weston had taken in stride; but these two did. He thought the man might have had something like antlers. “All right,” he said, tossing his lunch onto his boat and then gesturing after it. “Hop on.”

“That is not what we need,” said the antlered one who, despite his maleness, Logan couldn’t quite think of as a man after all. Like Helen—though he didn’t know it—Logan’s experience with communication with the Others so far had mostly been beyond words; he had said things, sometimes, but the Others had responded by seeming to put information right into his mind. This time, the antlered one had definitely spoken English, though his voice was, just as definitely, not human. It also wasn’t what Logan would have expected. It made him think of the great blue herons he tended to wake up in the mornings when he motored out of the protected side of the peninsula; their graceful take-offs and flights, and their squawking, harsh voices.

“Well, I need to go out,” said Logan, awkwardly. “You don’t want a ride?”

“We need,” said the feminine one now, “a place to stay.” Her voice was like the antlered one’s. Logan suddenly realized, looking at her sideways, that she was heavily pregnant.

“I can’t give you that,” said Logan, truthfully. Betsy’s house was full up as it was. They just looked at him with eyes that looked like owls’. “I could help you find a place,” he added reluctantly, “but not until I get back this afternoon. You’ll have to wait until then.”

“We will wait,” said the antlered one.

Neither of the two went anywhere as Logan got on his boat, did his engine checks, and then got her running. He came out of the pilot house to take off the dock lines, and they didn’t seem to have moved at all. “Well, I’ll see you,” said Logan. They didn’t say anything.

It wasn’t until he was eating his ham and cheese sandwich with one hand as he steered between oystering grounds that Logan realized what his conversation that morning had reminded him of; it had been like a perversion of a nativity play. “We need a place to stay,” indeed. He shook his head and drank some Gatorade.

An hour after that, well before he usually went in, Logan finished sorting the oysters on his culling board, reached for his tongs, and then froze for a moment. Helen wouldn’t have thought him expressionless if she could have seen his face at that moment, though she might not have been able to tell what he was thinking. A minute later, he said, “Damn!” out loud, stripped off his rubber gloves, and went back into the pilot house. A minute after that, he was speeding back to Weston, cutting through the tops of the mild waves on the bay, throttle full open.

Linda Crenshaw was in her kitchen, bullying Helen Phillips into making shortbread with her. The girl was far too easy to bully, in Linda’s opinion. (She also thought of any woman under about fifty as a girl.) Linda didn’t bake on her own much anymore; she had a nice mixer, these days, that made the stirring and everything easy even with her twisted, arthritic hands, but the washing up afterwards was often too much for them. But Helen, Linda thought, needed things to fill her time—she worked at the Acme market, but she seemed to have a lot of free hours when she wasn’t doing that—and Linda needed to find someone to give her recipe book to when she died. She’d had hopes in her youngest granddaughter, who was still in high school, but though she loved the girl, she was starting to see that she would be helpless in the kitchen.

It was while Helen was spreading the second batch of shortbread dough in the baking pan that someone knocked on the back door, which opened directly into the kitchen. “You keep doing that, I’ll get it,” said Linda, and worked her way around the round table, recipe book open in the center and the first batch of shortbread cooling on a rack, to where she could shoot the deadbolt back. On her back porch were Logan Nelson, wearing as many layers of clothing as if he were still out on the water, and two—beings. Linda, unlike Logan, noticed immediately that one of them was going to have a child. She looked back up at Logan’s face; he shrugged, looking—to Linda’s keen eye—somewhat helpless. “I didn’t know where else to bring them,” he said.

“You all had better come on in,” said Linda.

Helen surprised herself by not feeling at all panicked or guilty—her two default emotions—when two smallish Others walked into the kitchen, followed closely by Logan Nelson. She did feel, once the odd-looking figures were standing in the middle of the kitchen floor looking around themselves, that something wasn’t quite right. They didn’t seem to belong there, despite the fact that, usually, everyone belonged in Linda Crenshaw’s kitchen. It might have had to do with the smell they’d brought with them into the shortbread-smelling place, a wild but not unpleasant smell of dirt and green and musk, but it also seemed to be something else.

“No,” said Linda thoughtfully, as if reading Helen’s mind, “this isn’t the right place, is it? Would you be more comfortable in my shed?”

Helen got the idea that the Others understood Linda’s meaning by taking in more than just her words, but the one with antlers responded out loud. “That would be welcome,” he said.

“It isn’t heated,” Logan pointed out.

“I have a space heater,” said Linda. “We’ll run an extension cord out.”

“Do you have names?” said Helen, trying to be polite. She half wanted to crouch to talk to them, like they were small children—it was hard to tell precisely how tall they were, but she thought no taller than her shoulder—but she also thought that crouching would be the exact wrong move.

“Yes,” said one of them, and then they were silent again.

“Hmm,” said Linda, the way she did when she was remembering another story to tell. “Do you have something that we can call you?”

The one with antlers regarded her steadily. “I am Odd,” he said eventually, which was so true that Helen almost laughed. “And this is Ebb.”

Logan—once he’d shed some of the layers that kept him approaching comfortable on the water, and were stiflingly warm anywhere else—found himself clearing out Linda’s shed and running an extension cord across her back yard. He’d noticed the wrongness, too, when Odd and Ebb had stood in Linda’s kitchen; they were too un-human for such a human space. In the shed, in a sort of nest made of some old sleeping bags Linda had produced from nowhere Logan could see, they still seemed slightly out of place, but somehow better. “Why do you think that is?” said Logan to Helen, now drying dishes as she washed them. Linda had this effect on people, that you did tasks around her; all the tasks of getting the shed ready for the Others had loosened Logan and Helen up around each other, so that although they still weren’t familiar, they were willing to talk.

“Even wild things need shelter,” said Helen, surprising Logan and also herself, again. It had sounded like something Danielle might say. “If only for a season,” she added.

“‘To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven,’” said Linda, coming into the kitchen from the back door, but somehow having heard what they were saying. “Ecclesiastes,” she added.

“Oh, I know,” Helen, while Logan just nodded—he’d recognized it as Biblical, but that was about it. “What is it—‘a time to be born and a time to die.’”

“‘A time to keep, and a time to cast away,’” said Linda.

“Well now, that just sounds like fishing,” said Logan.

“Not just,” said Linda, her tone so close to severe that Logan felt chastened, no matter that she was as tall as his shoulder and mostly seemed to shuffle everywhere—energetically—rather than walk. Then she twinkled at him. “Crabbing and oystering, too.”

Helen told Danielle Evans about the Others in Linda Crenshaw’s shed. She hadn’t meant to, but she seemed to have gotten in the habit of saying things to Danielle while Danielle stood in her kitchen with her arms crossed—this time, Helen had called her and offered some shortbread, since she and Linda had made an exorbitant amount, and neither Logan nor Odd and Ebb had seemed to want much. “One of them is pregnant?” said Danielle, hands wrapped around the mug of tea Helen had made in a sort of acceptance that Danielle would stay for a while. “Do you think,” she went on, sounding almost untypically shy about it, “I could go see them?”

Helen felt a little panicky. “Please don’t—take notes or measurements or anything of them,” she said. “They’re just—people.”

“Not just,” said Danielle, unwittingly echoing Linda Crenshaw from a couple days earlier. “But I understand. I won’t.”

Logan wasn’t entirely happy about Danielle Evans knowing about Odd and Ebb. Danielle Evans made him vaguely uncomfortable, in a way that then made him further uncomfortable because he suspected he was being misogynistic. Logan didn’t have anything against women wearing pants—obviously, this was the twenty-first century, and also he could think of specific examples of women wearing pants that he didn’t mind. Rachel Caulder wore pants most of the time; they were obviously cut for a woman’s body, and looked both useful and nice enough that she sometimes went to church in them. And Betsy Drummond, from the next town over, had been running her father’s workboat ever since his stroke; she dressed exactly like the watermen, and was generally accepted as one of them, and Logan didn’t mind that at all, either. It was just that Danielle Evans strode around in her pants in a way that seemed to scream, I am a woman wearing pants, and I dare you to say something about it! Logan never dared.

So he was both uncomfortable and, maybe, a little jealous when he came into Linda’s shed on a Sunday afternoon—the third Sunday of Advent—to check whether Odd or Ebb needed anything, and found Danielle Evans already there, sitting quietly on an upturned milk crate and looking unexpectedly peaceful. Like Helen, he would have expected her to be writing notes or taking measurements or snapping photos with her phone; but her hands were sitting quietly in her lap.

“I, uh—did you need anything?” he said, not sure if he meant to ask the Others or Danielle.

“We are well,” said Odd, who seemed to talk more than Ebb. Despite the number of times he’d seen them now, Logan still wasn’t quite sure what they looked like. Ebb seemed now to have blue-gray feathers, but maybe because she gave the impression almost of sitting on a nest.

“Supposed to freeze tonight,” said Logan, glancing up at the roof of the shed where there were gaps at the eaves showing daylight. It was warmer inside there than it was outside—the space heater doing its job—but not so warm as to be comfortable without a few layers on. And though the Others didn’t seem to require food or any sort of hygiene assistance from the humans, they did seem to feel the cold. “I brought some more blankets, just in case.”

Danielle got up and came with him to his truck to get the blankets, which he hadn’t intended. “I think she’ll have the child soon,” she said, and smiled when Logan looked at her. “Because of what they’ve said,” she told him, “not because I have any previous knowledge of—of Other gestational periods. Give it another week, week and a half, maybe.”

“On Christmas?” said Logan.

“Maybe,” said Danielle again, accepting an armful of musty wool—Logan had raided Betsy Evans’ attic. “Oddly appropriate, if you think about it.”

Somehow, after that, the four people who knew about the Others in Linda’s shed found themselves making alternate plans for Christmas. Logan called his father, made sure he would be able to get himself and Logan’s mother to Andy’s house across the bridge, and begged off showing up, himself. He wasn’t particularly sorry; he loved his family, really and also dutifully, but he didn’t like Andy’s house or the city where it was. He would see them another time. Helen, in contrast, agonized over what to say to her parents, who turned out to be so happy to hear that she wanted to spend Christmas with some friends that they booked a last-minute hotel in another state so that they wouldn’t have to cook, and so that she couldn’t change her mind and come to them. They promised to see each other for New Years.

Though folks in Weston generally made it a habit to know each other's business, and though everyone knew that Danielle Evans’s parents lived in the same senior living center that Linda Crenshaw’s family always tried to get her to move to—she was a late and only child, unusually for the shore—no one knew what her Christmas plans would have been. But she told Linda one evening, while Linda taught her how to make a ginger cake (it was possible that neither Linda nor Danielle quite knew how they’d ended up there together) that she was planning to stay in town for Christmas, too. Linda told her in return that her own family usually did Christmas at their own houses and visited her, some more guiltily than others, in shifts between Christmas and New Years. “Which is exactly how I like it,” said Linda, “so that I can go to the evening service and then straight to bed, and not get up on Christmas Day until I feel like it.”

Meanwhile, the flow of Others seemed to be slowing. Like their arrival, this was not discussed openly so much as disseminated and understood among the residents of Weston, seemingly without anyone actually saying anything about it. Except Danielle Evans, of course; everyone was a little startled to see her chatting to Logan Nelson on the docks at the end of Hill Street one late afternoon, though possibly no one was more surprised than Logan himself, who’d come in from oystering to find Danielle pulling up a rope that had been untidily allowed to hang in the water off an unused piling for much of the past year, and carefully scraping the critters that wriggled in the muck on it, even in the cold of December, into a jar with a little water.

“We’ve been using microscopes,” said Danielle, by way of greeting and explanation, when Logan walked a little closer to see what she was doing, despite himself. “Logan, how many trips have you made this week to take Others out?”

“Just one,” said Logan, surprised into honesty. Not that he would have lied, normally; just grunted wordlessly, probably.

“There’s less of them around now,” said Danielle. “It’s like—like the changing of the tide.”

Logan considered this; in his experience, if the tide was going to change, it meant that things would start flowing back the other way. He didn’t know if he liked the idea. Danielle seemed to catch some of this from the look on his face. “Maybe not perfectly,” she said. “I just wonder about—what if any of them get stuck?”

They didn’t talk about Odd and Ebb except in the shed, or in the safe space of Linda Crenshaw’s kitchen. Logan knew what Danielle meant, though, and gave it the consideration it deserved; Helen Phillips might have dithered on when he stood silent for almost a minute (or maybe she wouldn’t have, these days) but Danielle just waited. “I think,” he said finally, “they know what they’re doing.”

“Interestingly, I do, too,” said Danielle. She was standing now, and had secreted the closed jar of critters in one of her coat pockets. “Even though I can’t think of one piece of evidence that specifically makes me think so,” she added, a little drily. “I suppose that’s what they mean by faith.”

Maybe it shouldn’t have been surprising when Danielle Evans, Helen Phillips, and Logan Nelson ended up sitting around Linda Crenshaw’s round kitchen table on Christmas Eve. In fact, none of the people there were surprised, but all were aware that someone like, say, Betsy Evans or Nancy Abel would have been not only surprised but talkative with it to know they were all there, so they’d arrived quietly and at different times. It was between church services; Helen and Logan had both been to the earlier one, separately from each other, and both Linda and Danielle had expressed plans to go to the eleven o’clock one; “Though if I don’t, I guess no one will miss me,” said Danielle.

“They would me,” said Linda, secure in her own importance in the structure of the town. “But I could just call Missy Evans and tell her I think have a chill, and she’ll be so happy she’ll tell everyone who’ll listen.”

The reason they were considering excuses for the late service was that they were waiting. Not even Danielle had bothered to try to put this explicitly into words, but they understood, anyway. It could have been any night, now, really; but this was Christmas Eve.

“Did your parents ever tell you,” Helen asked generally and only a little shyly, “that animals can talk on Christmas Eve, at midnight? I used to feed our neighbors’ chickens over the holidays, when they were away, and I always wondered a little if they’d say anything when I went in after the late service. I mean, it was silly—”

“I think I read it somewhere, instead of my parents telling me,” said Danielle, interrupting genially, “but we would all pretend it was true. I sort of knew I was pretending, but I used to kind of watch our cat anyway, when it was getting late on Christmas Eve, just in case.”

“I never did hear that,” said Logan, and then paused, remembering. Andy had sworn up and down, one Christmas, that he’d opened his window the night before and heard the geese talking out on the creek—not the usual goose chatter of the migrating birds who wintered on the shore, but words he’d understood. Andy had never had much imagination, and he still wasn’t too good at lying. He’d been insistent, though.

Logan didn’t share this. For one thing, he wanted to consider it a little longer. For another, the back door into the kitchen was open—though nobody had exactly noticed it opening—and Odd was there, his strong—but still not unpleasant—warm dirt and animal scent joining him like another presence. “It is time,” said Odd.

They trooped across the back yard, following him. Logan had seen animals give birth before, but never a human woman; since Ebb was neither, he found himself stuck in a sort of odd limbo between matter-of-fact interest and heavy embarrassment as soon as they entered the shed, and stuck himself in a corner near the door, back to the wall. Danielle, practical to a fault, rolled up her sweater sleeves but paused for some reason in the middle of the shed floor, so it was Helen who walked up to Ebb, bent to touch her head—this was the first time any of them had touched one of the two Others—and looked up to say, “Something’s wrong.”

“I know how this works—well, not this specifically—but only in theory,” said Danielle, when Logan and Helen both looked at her. “I’ll do what I can, but someone with actual experience would be better.”

Both Logan and Helen, though they didn’t realize it about each other, had a sort of catalogue of Weston Residents and Their Interests and Skills in their heads, because that was what you needed to keep up any sort of relationships with the people in the town. Despite this, both of them went entirely blank. Danielle seemed to see this. “Oh, for crying out—can you find Maria Guadelupe Martinez?” she said. “She works in obstetrics at the hospital.”

Helen realized that of course she’d known that, after all. “She’ll be at the evening service,” she said.

“I’ll drive,” said Logan.

On the way to Logan’s truck, they passed Linda, who, it turned out, hadn’t come out to the shed with them; she was carrying what seemed to be a pot of boiled water—it was steaming—with strips of sheets in it. Her twisted hands were closed hard on the handles; Logan tried to take it from her, but she somehow waved him off without actually having the use of her hands to do so. “I’ve got it,” she said. “Go get that Maria Guadelupe.”

Logan parked at the back of the church lot. “I think it’s going to snow,” he said. Helen glanced at the lights as she bustled up to the church, to see if she could see flakes, which distracted her from what she was about to do until she was standing outside the big church double doors. They were very creaky doors, and the church was of a size such that the sanctuary was directly inside; no buffer area that Helen could sneak into, unseen. The only other entrance was to the side room off of the altar area; Helen could get in there unseen, but then to get into the sanctuary from there she would have to walk out in front of the whole congregation, up by the pastor, so that wasn’t an option. Helen closed her eyes briefly, steeling herself, and thought of Ebb’s face. She thought she’d seen Ebb’s face clearly for the first time, just then, when they’d walked into the shed where she was laboring. It hadn’t looked human at all; but it had looked female, and surprisingly young, and maybe a little scared. “Please, God,” said Helen Phillips.

God works in mysterious ways, including, possibly, via the chancel choir of the Weston United Methodist Church. They’d just struck up Oh Come, All Ye Faithful when Helen pushed the door open; the people in the back pews turned around, it was true, but they were the only ones who’d heard the creak. And one of them—“Thank you,” Helen murmured briefly, “and Amen”—was Maria Guadelupe Martinez.