Amateur Historian and on-and-off writer. Historical thoughts about my favourite periods. The Middle Ages: The Angevins and Henry V specifically, but anything from 12th century to Henry VII will turn up. Italian Renaissance: Medici friendly blog and Borgia lover, as well as fond of the Burgundian dynasty.The French Revolution: probably a montagnard, but can never make up my mind. The Napoleonic wars: love Napoleon and Wellington equally, as well as Byron.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Have spent most of today reading Lustrum by Robert Harris, and the way he spaces out the First Catalinarian speech makes me weak at the knees!

The pause between the iconic first line "How much longer, Catalina, will you try our patience?" and the rest of the speech - created by Tiro (the narrator)'s personal interjection - offers a perfect moment of suspense.

The way the speech is initially slowed by descriptions of movement and people, only for the words to take over, leaving several pages simply of Cicero's powerful text.

The sudden burst of enthusiasm when focus returns to the Senate.

The way Catalina's departure is framed by the ancient relics of Roman military glories.

UGH!!!! What a way to present one of the most well known speeches in Latin.

#marcus tullius cicero#cicero#late roman politics#late roman republic#robert harris#robert harris lustrum#historical fiction#just a personal ramble of disjointed thoughts#what a piece of amazing writing creating an excellent atmosphere!

0 notes

Text

It's a day ending in Y so once again I am thinking about Richard Courtenay and the way that Henry V marked his death, specifically the fact of where Henry had Courtenay had buried and the fact that his deathbed tending of Courtenay is recorded in the Gesta Henrici Quinti.

Burial Amongst The Kings and Queens.

Richard Courtenay is buried in the chapel of St. Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey that effectively served as a royal mausoleum. With a few exceptions, every king from Edward I to Henry VI sought burial in this chapel for themselves and at least one of their queens (Edward II and Henry IV are the exceptions, though Edward may have chosen to be buried in St. Edward's chapel had he not been deposed). The few burials outside of this were, by the late medieval period, limited to the children of kings, such as Thomas of Woodstock (the youngest son of Edward III), Margaret of York and Elizabeth Tudor (the daughters of Edward IV and Henry VII respectively). Henry VI struggled to find space for his own tomb in the chapel - he was ultimately buried elsewhere due to his deposition - and he was the last king to choose burial there, with Edward IV opting for burial in St. George's Chapel at Windsor and Henry VII renovating the Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey to serve as a new royal mausoleum.

Courtenay was of noble birth - the grandson of the Earl of Devon, a great-great grandson of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile - and he could claim kinship with Henry V through their shared de Bohun ancestry. But he was far down the ladder from the royalty buried there, and had no close kin ties with the royals buried there.

The cathedrals at Exeter and Norwich would have been the most obvious options for Courtenay's burial. Courtenay, after all, belonged to a prominent Devon family and was the Bishop of Norwich. Burial in the other chapels of Westminster Abbey, while somewhat unusual, would also be appropriate. Instead, Henry V chose to bury Courtenay in St. Edward's chapel, where kings and queens and some of their children were buried. It is a rather extraordinary choice.

Henry's choice also looks all the more extraordinary considered in the context of the burial of John Waltham, Bishop of Salisbury in the same chapel. This was done on the order of Richard II, apparently on his own whim. It was contrary to the wishes of Waltham, who wanted to be buried in Salisbury Cathedral, and contrary to the will of the monks at Westminster, who did not think it was appropriate for a man of Waltham's low birth and status to be buried in St. Edward's chapel. According to Walsingham, it was a scandal and Richard had to appease the anger of the monks by donating vestments and a large sum of money to the abbey. Therefore, Henry, would have had a clear idea of how burying Courtenay in St. Edward's chapel could anger the monks and cause a scandal. Yet he persisted in his choice. He wanted Courtenay buried there, regardless of the potential backlash.

There is the possibility that three factors made all the difference. The first is that Courtenay was of noble birth while Waltham was a commoner - though, as I said, he was of significantly lower stock than everyone else but Waltham buried in the chapel. The second is that Courtenay's grave apparently had no marker, while Waltham's was marked with a brass, making Courtenay's grave virtually invisible and unobtrusive in the chapel. The third factor is that the actions of Henry V and Richard II have been held to different standards due to their reputations and styles of kingship.

Henry may have made concessions in effort to avoid angering the monks and to avoid scandal - such as the lack of grave marker for Courtenay, making his burial unobtrusive - but he can't have known that these concessions would be apparently successful, or that his own reputation as king would be what it was. It isn't clear when Courtenay's body was sent from Harfleur for burial but was before the Battle of Agincourt and perhaps before Henry had won Harfleur. In other words, Henry had won no great victory when he made the decision.

(I say "apparently was successful" because while there is no evidence of a scandal, it is possible that it went unrecorded.)

All that being said, the fact that Henry chose to bury Courtenay in St Edward's chapel is astonishing. He wanted Courtenay buried there and he was prepared to risk scandal to see it done.

Why?

He wanted Courtenay's body to lie close to his own body. Pursued to the natural conclusion, he believed that when the Last Judgement came and the dead were raised from their graves, Courtenay would rise with him. He wanted Courtenay to be one of his companions in at the ending of the world. All of this suggests he not only held Courtenay in great esteem but regarded him with great affection.

n.b. Henry was unmarried at the time of Courtenay's death so he did not "choose" burial with Courtenay over burial with Catherine of Valois. At the time of his death, he made no instructions or plans for Catherine's burial. It's possible that he imagined in 1415 that whoever he married would be buried beside him (Courtenay's grave is the closest grave to Henry's own but they are not in the same tomb or side-by-side) and in 1422, believed that Catherine should choose her own burial place, or would have remarried and her widower would choose her burial place.

Corpse-touching.

The best record of Courtenay's death is found in the Gesta Henrici Quinti. This is what it says:

And after these operations and the anxieties occasioned by the enemy, a just and merciful God, wishing to test the patience of our king and His anointed, as well by the deaths of several other noble men in his army touched him deeply by the death of one of the most loving and dearest of his friends, namely, the lord Richard Courtenay, bishop of Norwich. He, a man of noble birth, imposing stature, and superior intelligence, distinguished no less for his gifts of great eloquence and learning than for other noble endowments of nature, was regarded as agreeable above all others to the members of the king’s retinue and councils. He fell ill with dysentery on Tuesday, 10 September, and on the following Sunday, in the presence of the king who, after extreme unction, with his own hands wiped his feet and closed his eyes, released his soul from its prison to the bitter and tearful grief of many. Out of a most tender love, our king at once had his body sent across to England to be buried with honour among the royal tombs of Westminster.

I can't recall any positive stories of kings handling the bodies of their dying or dead friends like this. There might be analogues in medieval literature but my knowledge isn't complete enough to find one. The closet parallel to other medieval kings is the story that Richard II touched the corpse of his favourite, Robert de Vere, upon its return to England.

Walsingham recorded that:

[Richard] looked long at the face [of de Vere] and touched it with his finger, publicly showing to Robert, when dead, the affection which he had shown him previously, when alive.

Given the narrative that Richard and de Vere shared an "obscene familiarity" and were possibly lovers, this raises the potential for queer and/or homoerotic readings of Henry's tending of Courtenay's corpse. At the very least, Walsingham's account allows us to attach meaning to Henry's corpse-touching: it is a gesture of affection that began in life and continues after death

I do not want to suggest that Henry, in wiping Courtenay's feet and closing his eyes, showed greater affection for Courtenay than Richard did for de Vere. We have to remember that Courtenay was had literally just died and that de Vere's corpse was several years old at this point.

Anna Duch cites Henry's handling of Courtenay's corpse to defend Richard against the charge his handling of de Vere's corpse was inappropriate and morbid. It's an imperfect comparison for various reasons - Walsingham did not write about Henry's corpse-touching, de Vere's corpse was a lot more corpse-y than Courtenay's - but the best there is. While Walsingham makes "special mention" of Courtenay's death and describes him as "a most loyal supporter" of Henry, he makes no reference to Henry attendance at Courtenay's deathbed or the location of Courtenay's burial. In fact, the only detailed account of Courtenay's death I've seen comes from the Gesta Henrici Quinti; most just reference Courtenay's death in passing.

The Gesta Henrici Quinti.

The Gesta Henrici Quinti was written sometime between 20 November 1416 and 30 July 1417. The work's author is unknown but from the text, we know he was an English priest connected to the court, most likely a royal chaplain. The Gesta is universally accepted as a work of propaganda.

It isn't clear exactly who the intended audience of the piece were. From the surviving manuscripts - which are copies of the original, lost holograph - it seems clear that the intended recipients weren't individuals of high rank. The work justifies Henry's policies in relation to diplomacy and war, especially in relation to his upcoming second campaign in France. It may have been intended to promote this campaign in England or at the Council of Constance, since it also promoted the Anglo-Imperial alliance, vindicating Emperor Sigismund's seemingly hasty alliance with Henry.

This all raises the question of what, exactly, the intention was for including a fairly lengthy account of Courtenay's death. In some ways, it confirms the Gesta's overall image of Henry as both a honourable, considerate and humble Christian prince.

It depicts Courtenay's death as a trial for Henry, which Henry meets with not only resolve, for he does not falter in his plans for France, but with considerable care and affection for the ailing man. He, apparently, devotes himself to Courtenay's final moments. The individual actions Henry performs underscore his qualities. Henry witnesses in the sacrament of extreme unction, showing his piety. With his own hands, he wipes Courtenay's feet. This not only shows his humbleness but aligns him with Christ, who washed the feet of his disciples. His attendance of Courtenay's deathbed and tending to Courtenay's body shows him caring for and honouring a loyal and worthy friend. Courtenay's virtues are stressed in this scene, thus show the quality of the men who follow and love Henry. This is the only time Courtenay appears in the text - the embassies to France he led are mentioned in passing, but none of the ambassadors are named.

Yet I sometimes wonder about the purpose of including such a scene in the Gesta. As far as I know, this is the only text to give a lengthy treatment of Courtenay's death. It tells us how the king touched his friend's corpse, showing him the affection that had been the hallmark of their relationship when Courtenay was alive. It tells us that "out of a most tender love", Henry had his friend's corpse buried amongst the royal tombs at St. Edward's chapel. With their parallels to actions that had seen Richard II routinely criticised, it is worth wondering if they carried with them potentially subversive messages about Henry. If the friendship was one of excessive love and familiarity. Of course, the subversiveness is controlled: Courtenay is dead, the risk he posed as a favourite with the potential to make Henry's kingship sodomitical has never and will never materialise. Henry is safe to display his excessive love for his favourite, since the favourite is dying and then dead.

It is tempting to suggest that the elision of the deathbed scene in other sources suggests that it was an aspect of Courtenay and Henry's relationship that others found unspeakable, echoing the unspeakable sin of sodomy. But such a suggestion requires a great leap of supposition. Perhaps the other chroniclers did not know or that when it came time to write their version of events, Courtenay was long dead and comparatively unimportant to the messages they wanted to convey.

Yet knowing the text was a propagandistic one, likely written with Henry's knowledge, makes me wonder if the scene was included because Henry wanted it to be, regardless of the possible risks it carried. He wanted to remember his friend. He wanted the last moments he had with his friend to be captured forever. He wanted to be seen loving Courtenay.

Conclusion

Throughout this post, while I've raised the possibility that Henry and Courtenay were involved in a romantic and/or sexual relationship, it's only been as a possibility; I'm aware it's a flimsy possibility - the "evidence", such as it is, is nowhere as compelling as the evidence for Edward II and Piers Gaveston or Richard II and Robert de Vere, and the debate on whether these relationships were sexual and/or romantic is far from settled. We are not in the position to prove or disprove whether Henry and Courtenay ever did have sex - there's no evidence, but then, it would be surprising if there was. We are not in the position to know and label how, exactly, Henry loved Courtenay.

But what seems to me incontestable is the fact that Henry did love Courtenay. In my opinion, there is no other explanation for his actions.

References:

Gesta Henrici Quinti: The Deeds of Henry the Fifth trans. and eds. Frank Taylor and John S. Roskell (Oxford University Press 1975).

The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, trans. David Preest (The Boydell Press 2005)

Jessica Barker, Stone Fidelity: Marriage and Emotion in Medieval Tomb Sculpture (The Boydell Press 2020)

Anna M. Duch, The Royal Funerary and Burial Ceremonies of Medieval English Kings, 1216-1509 (PhD. thesis)

#henry v my beloved#henry v#richard courtenay bishop of norwich#gesta henrici quinti#the essays i would write about henry v if i had the time and energy...#this is such a wonderful and interesting essay/collection of thoughts!#this level of personal and physical affection shown by kings has a huge level of trust to it as well#the one source that people have used to base Richard I's possible homosexuality off mainly deals with the rituals of trust between him#and Philip II of France which includes sharing a bed as a sign of absolute trust#Henry's caring for Richard Courtney in such a prominent manner reminds me of Richard I and Philip II's trust exercises#but perhaps a little more genuinely affectionate#royal friendships and physical affection in the middle ages is so very fascinating

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do share it! I'd love to hear about Henry's dear comrade dying, and becoming Henry's tombmate. Henry's personal relationships are fascinatingly - and irritatingly - hard to find anything on, and I haven't managed to get my hands on the gesta henrici quinti yet, alas.

reading and analysing the passage in the gesta henrici quinti about richard courtenay's death and getting fucked up about it. happy pride. 🏳️🌈

#richard courtenay bishop of norwich#henry v#medieval guys being dudes#the hundred years war#gesta henrici quinti

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romantic poets

Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and John Keats!!

gay asf

who is your favourite?

#absolutely gorgeous#look at Byron's silly cloak#and the hand on Shelley's arm#I want to eat this#art#artists on tumblr#romantic poets#romanticism#lord byron#percy shelley#john keats

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

(catullus voice) every single one of my poems is written with the tip of my penis. and people will still call them molliculi versiculi…

#how dare you say my verses are soft i can’t even write without being hard#<- prev tags made me choke on my tea#this is entirely accurate#gaius valerius catullus#catullus#every drop of ink from that man's pen(is) could impregnate a Roman legion

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The purpose of poetry is to remind us how difficult it is to remain just one person, for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors, and invisible guests come in and out at will.

Czesław Miłosz, from from "Ars Poetica?"

#czesław miłosz#on poetry#very true#one is never just one person. we are a collection of people who have shaped us#whether for better or for worse#whether alive or dead#we carry a world of influences gifted us from others

487 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing the Renaissance 1450-1600: London Exhibition

Last December, I attended the truly wonderful exhibition at the King's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, and I thought I would showcase some of my favourite pieces and what I like about them. Art and Art History are new-ish areas to me, but I have been in love with the Italian Renaissance for years, and so hopefully the two will balance each other out.

Sketch for the Tapestry Christ's Charge to Peter, Raphael. (1515-1516)

The thing I adore most about this drawing is how elegantly it mixes the sacred and the mundane. The composition is very carefully arranged to separate the model for Christ from the others, creating a holy aura around him, with a straight posture offset by the many layers of the Model Apostles. St Peter has roughly sketched keys in his hands

But they are also clearly just young apprentices/workmen, wearing their contemporary linen clothes which are practical for Italian heat and getting covered in paint. They feel very much as if they might break out of the pose and go and fetch wine from a trattoria down the road any minute. It's a fascinating glimpse into artists' lives in the period, and how they could transform anyone into something brighter.

Sketch of the Risen Christ, Michelangelo. (c.1533)

Yet again, Michelangelo astonishes. As a sketch, this is captivating in it's detail. The minute marks he has made with the chalk, which I have highlighted in the closeup, must have taken such patience and concentration, let alone the way he uses them to create the outlines of muscles and add shadows. The posture is very arresting also, given the movement and the reach towards heaven - which I like that Michelangelo redrew so many times. The sense of drama and movement that has been captured so precisely on paper is alarmingly beautiful. I also find Michelangelo's habit of creating a swathed dome behind a divine figure interesting - he does the same for God the Father in the Creation of Adam.

Drapery study for The Madonna of the Rocks, Leonardo da Vinci. (c.1491-4)

This one caught my eye due to the interplay of light and shadow to highlight the anatomy hidden under the swathes of fabric. The intricacy of the folds is very akin to the landscape in the background of The Madonna of the Rocks, and shares the same effect of inviting the viewer to explore the hidden depths more.

My favourite detail, which is probably not visible on my picture, is that there is a thumbprint in the bottom right hand corner of the page.

St Jerome, Bartolomeo Passarotti. (c.1575)

This one is fascinating, as it is one of the two drawings I have chosen which was designed to be publicly shown. Whilst the others are studies for painting or sculpture, this shows artistic flourish in the thick ink cross hatching, and the intensely defined anatomical competence.

I enjoy the calm of the drawing, even though the subject is awkwardly twisted round to read the book behind him. The cleanness of light paper and dark ink combined with the uncluttered landscape make for a picture centred around introspective thought, rather than dramatic movement.

A Grotesque Mask, Michelangelo. (c.1525).

This one is simply charming. Realism is such an integral part of Renaissance art, and the complete understanding of light, perspective and the human body that they have makes even their sketches glow. Which is why I enjoy it when the artists draw absurd faces and nonexistent beasts. The playfulness and inventiveness seems all the more apparent to me in the fictionalised doodles: the detailing on the teeth and tongue despite them both being in shadow, and the surprised/distracted gaze off to one side are very arresting, as are the beetling eyebrows.

Study of the Muscles of the Leg, Leonardo da Vinci. (c.1510-11)

I haven't much intellectual to say about this one, saving that I adore how boundlessly curious Leonardo is about the universe, and how his curiosity shines through his work. The attention to position and the delicate thin shading to highlight the muscles is beautiful, as is the slight contraposto in the half-drawn torso. I also love Leonardo's spiky mirror scrawl, and want to learn how to imitate it someday.

A map of Southern Tuscany, Leonardo da Vinci. (c.1503-6)

This is one of the few of Leonardo's drawings designed for public viewing, and I think the care taken with it is fascinating. The bird's eye view of the Arno valley is ingenious, and allows for a sense of sweeping vista, contrasted by the specific detail given to the small drawings of the towns and rivers. The deep blue of the water is all the more astonishing when one notices the gentle reflections imprinted on it, derived from Leonardo's lifetime studies of water currents and light, and the shading on the hills makes each one individual and interesting. I also adore the careful, awkward printed names of places, in capital letters. It's a touch of humanity that I find really anchors the drawing in a time and place.

An allegory with a dog and an eagle, Leonardo da Vinci. (c.1508-10)

As I mentioned earlier, Renaissance artists having fun with the imagination is immensely charming, and this is especially funny. The technical elegance of the tree's leaves and branches really draws the eye, as does the rippled water beneath the keel of the vessel. The rays of light coming off the Eagle (thought to maybe represent Francis I of France) are astonishingly delicate, and the cragged rocks in the top left corner remind me of the background for the Madonna of the Rocks, if seen from the outside - Leonardo has such a distinct style of drawing rocky landscapes, which I find fascinating.

A Children's Bacchanal, Michelangelo. (1533)

To finish off my miniature exhibition, this sketch of Michelangelo's is a favourite of mine because for once the figures are playful, rather than tormented or unsatisfied. Made for Tommaso dei Cavalieri, Michelangelo's younger lover, as part of a series of polished sketches sent by the artist, this Children's Bacchanal is a mixture of innocence and debauchery which tell a fascinating story. The small children show a mischievous pleasure in causing chaos - I especially liked the small boy urinating in the wine - and Michelangelo renders their youthful chub very well. The clutter of the scene reminds me of the Last Judgement, but instead of the sublimity of Heaven and the horrors of hell, this sketch has a playfulness to it that makes it more human.

Thank you for coming on my little tour of Renaissance sketches! I hope that my inexpert admiration, "in little room confining mighty men"*, has caused some interest. Do ask questions, and I'll answer as far as I can.

(*Epilogue, Henry V, William Shakespeare.)

#renaissance#italian renaissance#renaissance art#high renaissance#raphael#raffaello sanzio#michelangelo#michelangelo buonarroti#leonardo da vinci#bartolomeo passarotti#renaissance drawings#renaissance sketches

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille had also studied with us at the College of Louis-le-Grand… Back then I didn't think he was so bad! He came to see me before the Revolution; he flattered me today, and saturated me tomorrow. He borrowed money from me, and tore me to pieces if I couldn't lend it to him. I have several letters from Camille, in which he gives me many flattering compliments; they are in prose and verse. He had talent, a lot of wit, maybe a good heart; but a very bad head…. The success of my Lunes made him frustrated. When slandering, he only thought to tell me. But, with this phrenesia, we would be sacrificing a whole world of innocent people; and, if it is true that, without having a bad heart, one is, in fact, as wicked and as barbaric as Camille was, then I return to my thesis, and I say that one can be a very dangerous terrorist, without having a bad heart. I do not believe, however, that he was guilty of what he was accused of in order to put him to death, I could not restrain my tears, seeing him pass by on his way to his execution. He had to be reduced to political nullity; but it was not necessary to cut his head off! Let's not cut anyone's head off anymore, if we can!

Testament d’un électeur de Paris (1795) by Louis Abel Beffroy de Reigny, p. 147.

#happy deathday to you!#camille desmoulins#beffroy de reigny#frev#frevblr#poor camille. he never deserved this

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

From my own limited knowledge of the Late Roman Republic, this is indeed highly complimentary, if also a little unfortunate in choices.

Cato: one of the most mortally upstanding examples of Late Roman virtue. Consistently acted for the good of the republic over the factional warfare that occurred in his time, and also as one of the optimes - the group of more traditionally minded politicians in Rome's Senate. He ended up killing himself - seen as the ultimate virtuous dear - rather than submitting to the enemy. Considered a Stoic post hoc, but like many Romans, didn't quite live up to the ideal.

Caesar: Aside from being one of the greatest tactical thinkers of the late Republic, Caesar was also an astute politician, forging alliances with two of the most politically slippery men in Rome - Crassus and Pompey - and managing to keep relatively tight hold of Roman politics up until his death, even if away fighting in Gaul. Caesar aligned himself with the populares, a faction which courted public opinion/sought to improve the lives of the lower classes. However, he was assassinated, as Tumblr likes to remind us.

Cicero: Being compared to the greatest orator of Rome, who became the role-model for all Medieval and Renaissance statesmen, is quite the compliment. Cicero's rhetorical style is one of the most elegant, witty, varied and engaging out there - read Pro Caelio in translation/in Latin for a sense of it, he makes you laugh in spite of the dubious content of what he's saying. Cicero politically navigated between the populares faction and the optimates, although his level of success is debatable. Nevertheless, he was a staunch and loyal republican. Unfortunately he sided with Brutus and Cassius after the death of Caesar, ended up on the wrong side of Mark Anthony, and was beheaded.

So I'd suggest that the implications are that Richard Courtney was as morally virtuous as Cato, as tactically/politically astute as Caesar, and as rhetorically clever as Cicero. However, any classics scholars will know better than I, as I'm also a Medievalist-Early Modern Historian.

Please weigh in if I've forgotten/misrepresented anything.

Richard Courtenay, who served as Chancellor of Oxford in the first decade of the fifteenth century and became bishop of Norwich in 1413, was considered ‘a Cato, a Caesar and a Cicero’.

James G. Clark, A Monastic Renaissance at St Albans: Thomas Walsingham and his Circle c. 1350-1440 (Oxford University Press 2004)

#richard courtenay bishop of norwich#historian: james g. clark#medievalism#medieval history#richard courtney#reign of Henry V#gaius julius caesar#marcus tullius cicero#cato the younger

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#henry v my beloved#shakespeare#shakespeare's history plays#henry v#shakespeare memes#look at all these charming little kings and their over-mighty subjects trying to steal the throne!

722 notes

·

View notes

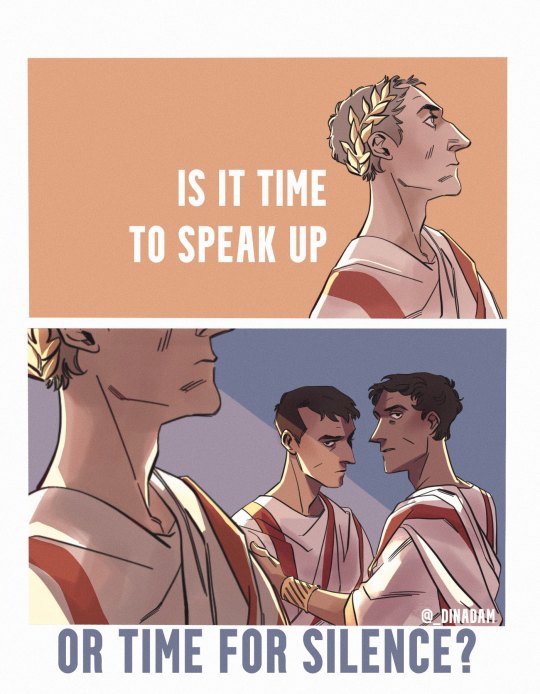

Photo

Do you have enough love in your heart To go and get your hands dirty? It isn’t that much, but it’s a good start So go and get your hands dirty

dirty, grandson

twitter| ko-fi | PRINTS | deviantart

#ides of march#gaius julius caesar#marcus brutus#cassius#late roman republic#late roman politics#beware! the ides of march!

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry, Prince of Wales (future king Henry V). By Herbert Norris.

#henry v my beloved#herbert norris#look at that gesture. what an amazing pose#the needle gown with fancy sleeves!!#I'm going to have to try and make it sometime

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

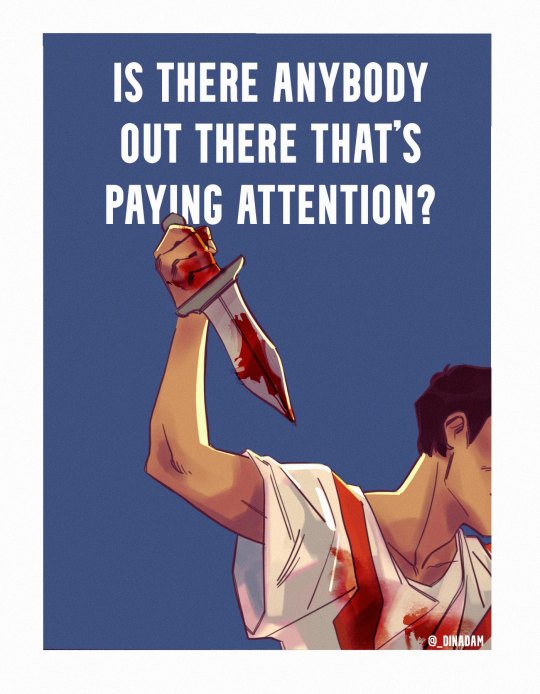

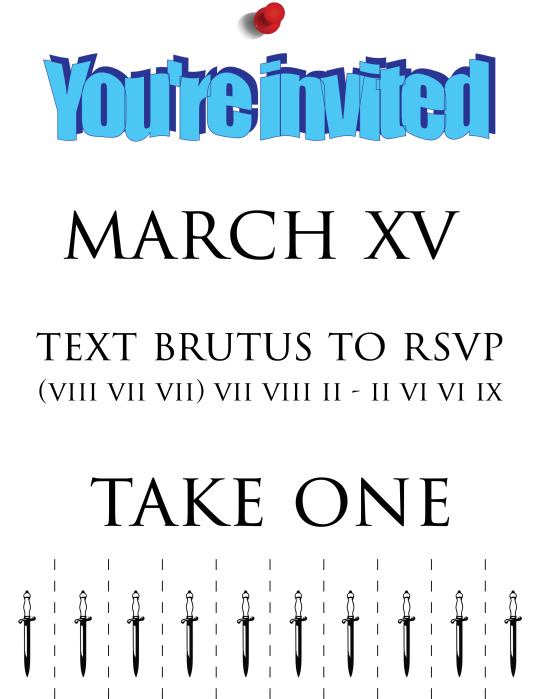

ONE MORE DAY

You can only reblog this on 14th march

#ides of march#julius caesar#time to rise!!!#knives for all!!!! 🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️🗡️#ancient roman politics#late roman republic#marcus brutus

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomorrow a bunch of prospective English lit grad students are coming in, which means I have an opportunity to bring out our facsimile of the Gough map, a map of Great Britain that dates to sometime in the fourteenth century (there's a lot of debate over exactly when) and which is the earliest English map to show the coastline in any sort of accurate detail. Mostly.

Because whenever this map was made, it was at a time when the English had a good sense of English and Welsh geography. They weren't so up on Scottish geography, so the Scottish coastline just sort of looks, you know, round.

It is also important to know that, while this is not a theologically-based map in the classic T-O style, like many medieval European maps it is oriented towards Jerusalem, meaning that the top of the map does not point north, as modern maps typically do, but rather east.

All of this combines to achieve a rather amusing effect. Here's what the Gough map looks like.

Yeah.

#gough map#manuscript funtimes#medieval manuscripts#medieval maps#medievalism#I love this map so much. and I love the Mappa Mundi with strange beasts on#medieval maps are amazing

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille Desmoulins evokes his role on July 12 1789 compilation

On Sunday, all of Paris was in consternation over the dismissal of M. Necker; I had in vain heated the spirits, nobody took up arms. At three o’clock I go to the Palais-Royal; I groaned, in the middle of a group, over the cowardice of all of us, when three young people passed holding hands and shouting ”to arms!” I join them; they see my zeal, they surround me, they urge me to mount a table. Within a minute I have six thousand people around me. “Citizens,” I said then, “you know that the nation asked that Necker be preserved for it, that a monument be erected for him: and they drove him out! Can you be defied more insolently? After this blow, they will dare everything, and this night, they meditate, they may start a Saint-Barthélemy for the patriots.” I was suffocated by a multitude of ideas which besieged me; I spoke without order. “To arms!” I said, ”to arms! Let’s all take green cockades, the color of hope.” I remember that I ended with these words: “The infamous police are here. Well! let them look at me, let them observe me well; Yes! it is I who call my brothers to liberty. And raising a pistol I said: ”At least they won’t take me alive, and I’ll know how to die gloriously. Only one misfortune can happen to me, that of seeing France become a slave. Then I climbed down; they embraced me, they smothered me with caresses. ”My friend,” everyone told me, ”we are going to watch over you, we will not abandon you, we will go wherever you want. I said that I did not want to be in command, that I only wanted to be a soldier of the homeland. I was the first to take a green ribbon and tie it to my hat. How quickly the fire spread! Camille in a letter to his father dated July 16 1789

I like to remember that at least this honor will not be taken away from me, that it was I who, at the Palais-royal, on Sunday July 12, climbed up on a table surrounded by ten thousand citizens, and showing a pistol to those who could not hear me, called everyone to arms, it was I who proposed to the patriots to immediately take cockades, to be able to recognize them, and avoid the Saint-Barthélemy with which they were threatened that very night, and defend themselves against the regimented assassins. The people having told me to choose the colors, I shouted: Either green, the color of hope; or the ribbon of Cincinnatus, colors of the republic: and as we had decided for green, after having told all the satellites of the police, mixed among the crowd, that they could look me in the face, that I would not fall alive into their hands, I climbed down, and immediately attached the green ribbon to my hat. Desmoulins in number 9 (January 25 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

I made my provisions, on July 12, according to these words of the consul in the dangers of the republic, Videte ne quid respublica detrimenti capiat, according to these words of our general: The insurrection and the lantern do the weakest of duties. Desmoulins in numbers 24 (May 9 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

I have not failed to prove, by my example, that the opportunities to serve one's country are not lacking for the least of the citizens; because, standing on a table at the Palais Royal, on Sunday July 12, at four o'clock in the afternoon, I was the first to call the French to arms and to liberty, because I was the first to display the national cockade! Desmoulins in number 31 (July 28 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

Then love of the homeland will undoubtedly make me find in my breast that courage which made me climb onto a table at the Palais-Royal, and be the first to take the national cockade. Desmoulins in number 39 (August 23 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

Truly, when I consider this idolatry of the almost universality of the national assembly, I feel the boiling of my anger against Mirabeau drop a little. How can we believe that the author of the work on the lettres de cachet, where he so faithfully traced the portrait of kings, the one who, the day after the day when I proposed to the people the choice of two colors for their cockade, either green, the color of hope, or the blue ribbon of Cincinnatus, color of the republic, the one who publicly said the next day, they do not have enough spirit to take the blue one, the man who translated and commented on the theory of royalty, by Milton, how can we believe, I say, that he is a monarchist by principles? Camille in number 71 (April 4 1791) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

It was half past two; I came to survey the people. My anger against the despots had been turned into despair. I did not see the groups, although deeply moved or dismayed, quite disposed to the uprising. Three young people seemed to me to be more vehemently courageous; they held hands. I saw that they had come to the Palais-Royal with the same purpose as me; a few passive citizens followed them. ”Messieurs,” I said to them, ”here is the beginning of a civic gathering; One of us must dedicate himself, and get up on a table to harangue the people.” ”Get up there.” I agree to. Immediately I was carried rather than climbing onto the table. I was barely there when I saw myself surrounded by an immense crowd. Here is my short harangue that I will never forget: “Citizens! there is not a moment to lose. I have just arrived from Versailles; M. Necker is dismissed: this dismissal is the tocsin of a patriotic Saint-Barthélemy: this evening all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ-de-Mars to slaughter us. There is only one resource left for us, and that is to run to arms and take cockades to recognize ourselves.” I had tears in my eyes, and I spoke with an action that I could neither find nor paint. My motion was received with endless applause. I continued: “What colors do you want? Someone cried out: ”You choose.” ”Do you want green, the color of hope, or Cincinnatus blue, the color of American freedom and democracy?” Voices were raised: ”Green, the color of hope!” Then I cried out: ”Friends! the signal is given: here are the spies and police satellites looking me in the face. At least I will not fall alive into their hands.” Then, drawing two pistols from my pocket, I said: ”Let all the citizens imitate me! I came down smothered in embraces; some held me against their hearts; others bathed me with their tears: a citizen of Toulouse, fearing for my life, never wanted to abandon me. However, they brought me a green ribbon; I put the first one on my hat, and distributed some to those around me. Camille in number 4 (December 21 1793) of Le Vieux Cordelier

#happy birthday camille!#frev community#frevblr#french revolution#camille desmoulins#frev#frev compilation

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Important public announcement! We must be freed from despotic oppression, and follow in the footsteps of our illustrious ancestors, whose images stand in every home. The traditions of our ancestors must be upheld, and if violence is the way forwards, then it is the duty of every citizen to wield the knife against the tyrant!

#the ides are coming#marcus junius brutus#ides of march#julius caesar#late roman republic#liberty is ours!#respect the mos maiorum!

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not drawing armor again (few notes under cut)

I heavily based the armor from this pottery art where Achilles is bandaging Patroclus' arrow wound only changing their skirts/kilts(?) and a few elements. Also changed Achilles' helmet a bit because I really want to lean in on the idea his face is obscured so Patroclus is not recognized when he's wearing it (from afar at least)

#achilles#patroclus#patrochilles#the iliad#trojan war#amazing art!#look at the armour! that is some dedication#bronze age greece#ancient greece

927 notes

·

View notes