Text

Children deserve patience.

I remember all the times growing up that I’d get in trouble for something I said or did, and I’d get in more trouble when I asked for an explanation. I was told I was “talking back” or being a “smart ass” when I literally was just trying to understand.

I also find that I’d get punished for being emotional. Even if I didn’t handle them in the right way, that was an opportunity to teach me how to handle them better. Instead I got in trouble and it just taught me to suppress my emotions. And honestly? Adults have bad days and difficulty handling their emotions. But somehow as a child, I was punished for not being perfect.

I think, for my parents at least, they’d get upset and ask why I was disrespecting them or doing something to them. And I think that’s the problem. They took my actions to mean I was maliciously trying to upset them when that was never the case. Instead of sitting back and trying to figure out why a child might be doing what they’re doing, they took it personally and that’s what made them so angry. If you think someone is intentionally trying to upset you, it’s going to likely upset you. And that wasn’t a fair assumption to make.

Children deserve patience and the benefit of the doubt.

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parent: (allows son to wear a dress because he wants to)

Society: "THIS IS PUBLIC HUMILIATION! THIS IS TORTURE! NO PARENT WHO LOVES THEIR CHILD WOULD EVER DO SUCH A THING!"

Parent: (intentionally puts their child in an embarrassing situation for the explicit purpose of publicly humiliating them in order to exercise their parental authority)

Society: "This is good parenting. More parents need to be like you."

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

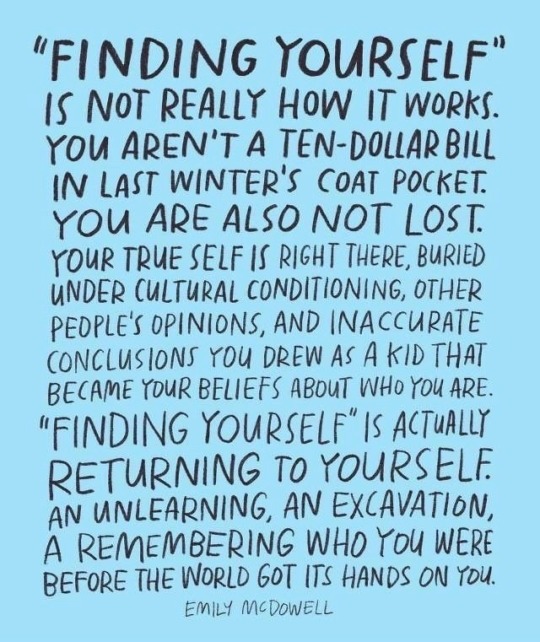

Just my non-professional take of course. But when I see things like this:

It makes me think that a lot of why people are into zodiac stuff is because it lets them find "reason" for why they are who they are, without looking at their past, their family dynamics, or their wounds.

How/why would being born in a certain month-ish span of the year make you very sensitive to feeling like you are begging or burdening people by requesting help that they don't immediately provide?

Doesn't it seem more logical to think that something about your past has taught you to feel that way? Maybe your parents acting annoyed when you asked them for things, especially more than once which gave you the message that you are a burden, annoying, undeserving of help, etc?

Or maybe witnessing other adults being hyper-independent and resistant to requesting help for themselves and treating their hyper-independence like a virtue so you took on their values, too? Maybe hearing someone refer to others asking more than once as 'nagging' or burdensome in some way? 🤷♀️

I'm sure there are lots of possibilities. But doesn't it just make more sense that it would be tied to something you learned and internalized rather than you being an Aries, when all an Aries means is just being born in a certain window of the year?

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Conflict Avoidant"

I saw this in a tiktok and keep thinking about it.

People call themselves (or others) "conflict avoidant" often. Or they say they're afraid of conflict. I definitely have said these thing myself. This tiktok stuck with me because it made such a good point. Which is, the vast majority of these people aren't really afraid of conflict. Because conflict is just having a disagreement. And disagreeing when you both respect each other and have good intentions, is not a bad or scary thing at all. It often is a really positive thing. It's something that allows you to reconfigure something in your life so that it works better for you and better for your loved ones. It can be a chance to grow, and a chance to connect with someone, understand them better, etc. Even if the conflict is extremely tough and you can't seem to find a way to come to an agreement...you could still walk away agreeing to disagree.

Conflict is just sharing your perspectives while they share theirs, and you work to find a sense of understanding, or learn where to place boundaries, or you find a way to negotiate so that both people are better off, etc. Healthy conflict isn't scary to most people. Most people, if they were conflict that conflict would be handled with respect, no raised voices, no name calling or manipulation, etc - they'd not be afraid of or choose to avoid the conversation at all.

Most people who are "afraid of conflict" are actually afraid of abuse. They have a history of knowing that when they disagree with someone else, or when they ask for someone to accommodate a need, or that they need to set boundary - that people have responded with hostility, rejection, screaming, emotional abuse, even physical abuse. So they assume that if they bring up a problem or a need, that this person will (or at least might) mistreat them. And that's what they are afraid of. Or perhaps instead of abuse, they associate conflict with being abandoned/neglected, so they fear if they raise conflict, they'll be abandoned.

Fear of abuse, fear of rejection, fear of abandonment, yes. And humans are supposed to be afraid of these things. Those are protective instincts.

But it's not a fear of conflict. We shouldn't be afraid of conflict with people who respect us, and if you've lived a life that has taught you to associate abuse, mistreatment or abandonment with conflict, then it's understandable that you've become conflict avoidant in an attempt to be abuse/mistreatment/abandonment avoidant - but it's a shame because respectful conflict/disagreement is a key part of healthy relationships.

#my posts#therapy#trauma#childhood emotional neglect#emotionally immature parents#conflict avoidant#fear of conflict

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semi-recently, when discussing something about somatic or embodying type therapy, my therapist explained how somatic work makes sense because our bodies respond first. He used the example of how if someone hides in a closet in your house and pops out and says 'boo' when you aren't expecting it...if you could break it down into slow motion...

First your body reacts. You might step back, or you might raise your arms up, or make a fist.

Then emotion hits. You're scared/irritated/unsettled/whatever

Then thoughts come in. "Why did you do that?" or 'AGh, you got me!' or whatever.

And that's not just true for fear, it's true for all emotions. It's just that we don't often realize our body reacts first, as many of us spend so much time in our heads that we think of our feelings as basically being thoughts, when thoughts really are stories we make up to try to explain our feelings.

Anyway.

Recently, my partner mentioned that a truck pulled into our driveway that looked kinda like my dads. A late 80s or early 90's big, boxy truck. And how it took him a minute to process what was happening, and how he was feeling about it.

And I empathized, and shared how I've had that type of experience except when seeing people around his age, who share his really-tan-for-a-white-dude skin tone, who are wearing a dark green carhartt type coat like he had. And it really is just a split second, a fraction of a second - but it's enough of a whiplash that it feels like my heart got turned upside down.

I've heard other people call those types of experiences "forgetting" that they're gone. And while I understand what they mean, and I don't know of a concise explanation that would put it any better... that's always felt incorrect to me. Because I never feel like I forget. From the moment I heard his last breath, I have remembered that he's dead, 24/7. Even in my dreams, if he is alive, it's that he came BACK to life, it's never that he didn't die. And I've never really known how to make sense of these conflicting experiences where I react as if something I saw was him, and yet I didn't literally forget he was dead.

But I think the somatic thing...about how our bodies react to our environments before we actually think about them...is the answer to that contradiction. I think my emotions and my thoughts have always known he was dead since he died. But my body only knew him to be alive for 30 years, and 2 years isn't enough to change that, so it kinda forgets that reality has changed, while the rest of me can't.

#grief#no idea why this is coming out today but i'm just rolling with it#sigh#i'm really really tired of grief and I have a lifetime to go

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#it's really so backwards that we give adults more respect and grace than we give children#like how bonkers would it be to be less forgiving of the person on their second day of work vs the longterm employee?#kids are still new to being here! And their brains aren't developed for like two full decades

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trauma layers

Therapy is such a mindfuck sometimes. I 100% get it when people say they don't think therapy would help them because they are pretty self-aware or self-reflective. Cause, that seems so freaking logical. But, I swear, with the right therapist you'll find yourself routinely shocked at how blind you actually can be to your own bullshit. Our brains try SO hard to hide our bullshit from us, it's insane. I guess I shouldn't speak for everyone, but it's so true for traumatized brains, at least. I know that minimizing or outright hiding your issues from you is how the brain responds to trauma. But it's still eye opening to me when I catch on to new pieces of this in myself.

I went into my appointment today with several ideas of what to potentially talk about written down. I knew what had been on my mind the most, but I wasn't sure if it made sense to use the appointment to discuss it because I've discussed essentially the same thing with my therapist multiple times in the past. So a big part of me was like eh, that'd be a waste of time. I know everything there is to know about myself in this area. Probably spend more time on these other things as that'll probably be more productive/helpful.

But I decided to at least mention it and see where it goes. I expected to jump topics pretty quickly as I didn't think we'd find new ground to cover. But we wound up spending 45ish minutes out of the hour on it. And it was productive. And yet, it's hard to really express why. It's not like there was some big new revelation. I largely went into it knowing what my trauma is, why I have this trigger, what my default response is, etc etc etc.

To spell out this piece of my trauma a bit...

I had an eggshell stepdad, and a constantly-overwhelmed semi-eggshell mom. My stepdad exploding was my mom's biggest trigger. And anger from either of them basically means anything could happen. Some of what I saw happen after anger, much of it starting off with really low level things like..someone shutting the door a little harder than normal (not really slamming it) or tossing their keys onto the counter a little too loudly. These kinda things were triggers to me as a kid because I knew they could mean an explosion was coming. Anyway, what I dealt with related to my eggshell caregivers' anger...

Emotional abuse between adults (very common)

Emotional abuse at kids (very common, my siblings who were externalizers caught more than I did, but I couldn't avoid it either)

Lower-level physical abuse of kids (semi-common but was my siblings, not me that I ever recall)

Domestic violence between adults (very rare, maybe 2-3 times ever)

Items being broken/physical aggression with household items (Rare-ish, maybe once a year?)

Recurring arguments or break-ups (extremely common. Fights rarely stayed as one event. They'd usually argue, try to wrap it up, and then explode again within a few hours, or perhaps even a few days later, but there was almost always a round two, at minimum. Core issues were never resolved, clusters of several related arguments over a week or two were common as well.)

Once I saw an adult hold a gun to their head after threatening suicide.

Once I saw an adult pull a gun on another adult (neither was part of my household).

Maybe 4-5 times over my childhood cops came to our house following arguments and/or violence.

My coping method was to try to be pleasing when the anger was lower-level. Keep things light if you can, but at minimum, don't do anything that might set anyone off. Once anger was bigger, just try not take up any space. Outright leaving (like going to my room) would sometimes get noticed in a negative way, so don't flee, but stay as far away as you can without actually leaving. Like...stay in the living room but sit silently on the couch, pretending you don't even notice the argument happening. Try to go unnoticed...blend into the decor. Stay out of the line of fire when the bombs are going off, basically. And when that failed and you're in the line of fire, fawn/people please to try to 'fix'.

What this looks like for me now, as an adult - is still to try to 'fix' other people's irritation, frustration, low level anger if I can find any way to. Or with 'big' anger, kinda freeze, or try to fawn/people please if it's directed at me. I can't feel safe if others are upset, so I try to absorb it so I can do something about it. And after someone around me shows anything adjacent to anger (like frustration) my brain likes to assume this is just 'round one' of anger, and round 2 will happen soon and will be bigger and scarier. So I'm very on-edge after 'detecting' any anger in my environment, even when it's really small. And my brain tries to pull my down a rabbit hole of finding potential things I've 'done wrong' that might be making this person secretly angry at me. Even when I logically know it has nothing to do with me. My brain wants to find a potential reason it could involve me. I'm pretty good about not letting it go down that rabbit hole very far, but it sure tries - and I have to spend energy holding it back from going there.

None of this is news to me, at all. I sort of forget when I've made certain realizations in therapy, but I think I've known all of this about myself for at least a year? So I wasn't sure there could be anything productive to come out of sharing how someone was frustrated around me this week and it triggered me...and how I knew I was triggered, and talked to myself about how my brain was reacting the way it did when I was a kid, but how my current situation is safe. How someone else's anger isn't a threat to me anymore. How I've created a life for myself that is safe, even when people get angry. I can have tough conversations with those closest to me. I don't get very close with anyone I can't do that with. So I consciously recognized all of this, but it didn't get rid of the anxiety. I stayed frozen in a moderately anxious place, hyper vigilant, unable to focus, and so drained from all of this emotional energy being spent on basically, nothing productive.

I expected my therapist to remind me that I'm trying to literally rewire the pathways in my brain, and I have 30ish years of my brain going down the "anger is very unsafe, I must regulate others' emotions and people-please." pathway. And that was said. As well as some usual points about how some of this equates to expecting myself to be able to mind read, and given that I am not a superhero or someone with magical powers, that expectation is cuckoo for cocoa puffs. I know this, but the reminder is good. But some new things were said too.

They asked if, after detecting someone else's frustration recently, I was able to put a loved one in my own place. We've talked a lot about how it's easier for me to empathize with myself if I imagine someone I care about in my shoes. Would I tell a friend that they should 'fix' someone elses frustration? That if someone sighs in their home that they should become hyper-critical and over-analyze anything they could have possibly done 'wrong'? Of course, the ridiculousness of this is apparent to me when imagine someone else in my shoes. But I admitted to them that I hadn't been able to remember to try using that trick to change perspectives until after I had settled some. That when I'm first triggered, I kinda seem to lose access to that more logical side of my brain that would allow me to try to remember specific suggestions or tools that had been suggested to me. They said it makes sense to forget when you're that emotional, so sometimes visual reminders are good. Like wearing a bracelet with a compassionate statement on it or something. Honestly, that feels cheesy to me, I don't really care for wearing anything that has text of any kind on it, to be honest and growing up with no positive feedback/praise has left me with a strong aversion to positivity like that..which is something else to work on but, one thing at a time. Anyway - I do like the idea of some sort of symbol in my environment serving as a reminder even if it has no text on it. Something that I'd take as a reminder perhaps, without anyone else needing to have a clue what it's about. So it was nice to get a little bit of a fresh idea on something additional to try.

But bigger than that...they helped me realize that I have continued my pattern of self-abuse, and just disguised it as trying to help myself.

Meaning...I see myself being triggered, I see myself starting to fall into old patterns of trauma responses to try to cope, and I know that reaction is maladaptive at this point in my life. So I try to stop myself from repeating that old pattern of trauma responses...and on occasion I can stop it in its tracks. But not often with this anger related trigger, it's a real powerful one for me. And when I'm not successful and I find myself becoming hypervigilent and self critical due to someone elses anger..I beat myself up about it! I beat myself up for beating myself up...because I'm 'supposed to' be working on being more compassionate. And that's still part of this cycle, it's just another layer of it. I beat myself up because keeping myself in a position of guilt/shame keeps me small so I can stay in this position of feeling like I am wrong and they are right and I am guilty and need to fix.

It's bonkers that even in my attempts to heal, my old self-harming mindset comes out disguised as a cure for.

In other words..

My logical brain "I need to stop beating myself up. That is a trauma pattern that used to serve me as a kid, but is just harmful to me now."

My trauma brain: "Right! We're hurting ourselves and that's dumb! Let's beat ourselves up about that! That's the solution!"

Fuck.

#ptsd#cptsd#trauma#ogres are like onions#onions have layers#trauma onions?#want to watch Shrek now#attachment trauma#childhood emotional neglect#childhood emotional abuse#emotional abuse#fear of anger#fawning#people pleasing#developmental trauma#internalizing#internalizers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Couple more chapters down.

Children often think the cure for their childhood pain and emotional loneliness lies in finding a way to change themselves and other people into something other than what they really are. Healing fantasies all have that theme. Therefore, everyone's healing fantasy begins with If only… For instance, people may think they'd be loved if only they were selfless or attractive enough, or if only they could find a sensitive, selfless partner. Or they may think their life would be healed by becoming famous or extremely rich or making other people afraid of them. Unfortunately, the healing fantasy is a child's solution that comes from a child's mind, so it often doesn't fit adult realities.

One woman secretly believed that if only she could make her depressed father happy, she would finally be free in her own life to do what she wanted. She didn't realize she was already free to live her own life, even if her father stayed miserable. Another woman was sure she could get the kind of love she longed for from her husband if she did everything he wanted. When he still didn't give her the attention she thought she'd earned, she was furious with him.

Her anger covered the anxiety she felt when she realized her healing story wasn't working, even though she'd given it her best shot. Since childhood, she had been sure she could make herself lovable by being a "good" person. We usually have no idea that we're trying to foist a healing fantasy on someone, but it can be seen in the little tests of love we put people through.

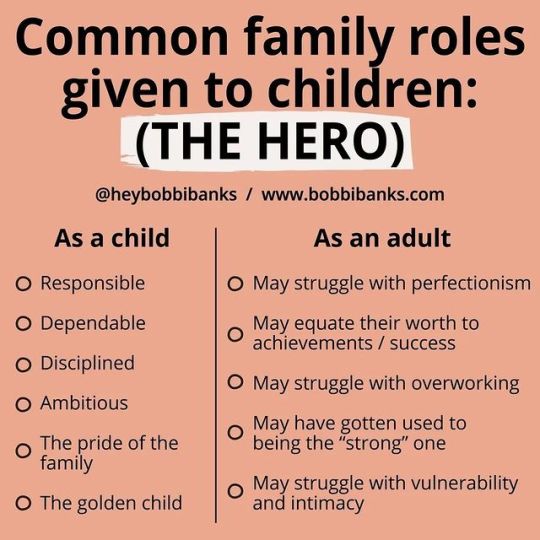

If your parents or caregivers don't adequately respond to your true self in childhood, you'll figure out what you need to do to make a connection. Instead of just being who you are, you'll develop a role-self, or pseudo-self (Bowen 1978), that will give you a secure place in your family system. This role-self gradually replaces the spontaneous expression of the true self. This role-self might based on a belief such as I'll become so self-sacrificing that other people will praise me and love me. Or it might take the negative form of I'll make them pay attention to me one way or the other.

You may wonder why all children don't make up wonderfully positive role-selves-why so many people are acting out roles of failure, anger, mental disturbance, emotional volatility, or other forms of misery. One answer is that not every child has the inner resources to be successful and self-controlled in interactions with others. Some children's genetics and neurology propel them into impulsive reactivity instead of constructive action. Another reason negative role-selves arise is that it's common for emotionally immature parents to subconsciously use different children in the family to express unresolved aspects of their own role-self and healing fantasies. For instance, one child may be idealized and indulged as the perfect child, while another is tagged as incompetent, always screwing up and needing help.

Another problem with the role-self is that it doesn't have its own source of energy. It has to steal vitality from the true self. Playing a role is much more tiring than just being yourself because it takes a huge effort to be something you are not. And because it's made-up, the role-self is insecure and afraid of being revealed as an imposter.

Playing a role-self usually doesn't work in the long run because it can never completely hide people's true inclinations. Sooner or later, their genuine needs will bubble up.

most emotionally immature parents are externalizers and struggle against reality rather than coping with it.

Externalizing tends to elicit punishment and rejection. In contrast to well-behaved internalizers, externalizers act out their anxiety, pain, or depression. They do impulsive things to distract themselves from their immediate problems. Although this may help them feel better temporarily, it creates more problems down the road.

Externalizing in children promotes emotional dependency and enmeshment with the parent's dynamics (Bowen 1978). Further, emotionally immature parents may indulge an externalizing child because doing so distracts them from their own unresolved issues. When dealing with an out-of-control child, parents don't have time to think about their own pain from the past. Instead, they can take on the role-self of the strong parent helping a weak and dependent child who couldn't get along without them.

people who seek therapy or enjoy reading about self-help are far more likely to have an internalizing style of coping. They are always trying to figure out what they can do to change their lives for the better. In contrast, people who externalize their problems are more likely to end up in treatment due to external pressures, such as courts, marital ultimatums, or rehab. Much of addiction recovery is geared toward nudging externalizers toward adopting a more internalizing coping style and taking responsibility for themselves. You could even think of groups like AA as a movement designed to turn externalizers into internalizers who become accountable for their own change.

Internalizers may have an exceptionally alert nervous system from birth. Some research has found that differences in babies' levels of attun-ement to the environment can be seen at a very early age (Porges 2011). Even as five-month-old infants, some babies show more perceptiveness and sustained interest than others (Conradt, Measelle, and Ablow 2013). Further, these characteristics were found to be correlated with the kinds of behaviors children engaged in as they matured.

In his review of his own and others' research, neuroscientist Stephen Porges (2011) has made a strong case that innate neurological differences exist even in newborns. His research suggests that, from early in life, people may differ widely in their ability to self-soothe and regulate physiological functions when under stress. To me, this seems to indicate the possibility that a predisposition to a certain coping style may exist from infancy.

When internalizers experience a painful emotion, they're much more likely to look sad or cry- just the sort of display an emotionally phobic parent can't stand. On the other hand, when externalizers have strong feelings, they act them out in behavior before they experience much internal distress. Therefore, other people are likely to see externalizers as having a behavior problem rather than an emotional issue, even though emotions are causing the behavior.

As an internalizer, Logan had a strong need for authentic emotional connection. Unfortunately, her self-preoccupied siblings and parents weren't interested in that kind of relationship. No one in her family paid attention to feelings, and her expressions of enthusiasm fell on deaf ears. In keeping with their emotional immaturity, her parents were intent on playing out their narrow family roles, as were her siblings.

Most emotionally immature people tend to be externalizers who don't know how to calm themselves through genuine emotional engagement. When they feel insecure, instead of seeking comfort from other people they tend to feel threatened and launch into fight, flight, or freeze behaviors. They react to anxious moments in relationships with rigid, defensive behaviors that alienate other people, rather than bringing them closer.

Emotional immaturity in parents guarantees that their children will experience significant emotional neglect.

Quotes from adult children of emotionally immature parents

These are passages that I've sent to myself because they stood out to me. I'm only through the first few chapters so I'll probably update with more later.

Children who feel they cannot engage their parents emotionally often try to strengthen their connection by playing whatever roles they believe their parents want them to. Although this may win them some fleeting approval, it doesn't yield genuine emotional closeness. Emotionally disconnected parents don't suddenly develop a capacity for empathy just because a child does something to please them.

People who lacked emotional engagement in childhood, men and women alike, often can't believe that someone would want to have a relationship with them just because of who they are. They believe that if they want closeness, they must play a role that always puts the other person first.

What Jake didn't realize is that hate is a normal and involuntary reaction when somebody tries to control you for no good reason. It signals that the person is extinguishing your emotional life force by getting his or her needs met at your expense.

Emotionally immature parents don't know how to validate their child's feelings and instincts. Without this validation, children learn to give in to what others seem sure about.

Like children, emotionally immature people usually end up being the center of attention. In groups, the most emotionally immature person often dominates the group's time and energy. If other people allow it, all the group's attention will go to that person, and once this happens, it's hard to redirect the group's focus. If anyone else is going to get a chance to be heard, someone will have to force an abrupt transition- something many people aren't willing to do.

It's also important to remember that old-school parenting- -the upbringing my clients' parents experienced- -was very much about children being seen but not heard. Physical punishment was not only acceptable, it was condoned, even in schools, as the way to make children responsible. For many parents, "spare the rod and spoil the child" was considered conventional wisdom. They weren't concerned about children's feelings; they saw parenting as being about teaching children how to behave. It wasn't until 1946 that Dr. Benjamin Spock, in the original version of his mega-seller The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, widely popularized the idea that children's feelings and individuality were important factors to consider, in addition to physical care and discipline. In the generations before this shift, parenting tended to focus on obedience as the gold standard of children's development, rather than thinking about supporting children's emotional security and individuality.

It may be that many emotionally immature people weren't allowed to explore and express their feelings and thoughts enough to develop a strong sense of self and a mature, individual identity. This made it hard for them to know themselves, limiting their ability to engage in emotional intimacy. If you don't have a basic sense of who you are as a person, you can't learn how to emotionally engage with other people at a deep level. This arrested self-development gives rise to additional, deeper personality weaknesses that are common among emotionally immature people, as outlined in this chapter.

Instead of learning about themselves and developing a strong, cohesive self in early childhood, emotionally immature people learned that certain feelings were bad and forbidden. They unconsciously developed defenses against experiencing many of their deeper feelings. As a result, energies that could have gone toward developing a full self were instead devoted to suppressing their natural instincts, resulting in a limited capacity for emotional intimacy.

Emotionally immature people who are otherwise intelligent can think conceptually and show insight as long as they don't feel too threatened in the moment. Their intellectual objectivity is limited to topics that arent emotionally arousing to them. This can be puzzling to their children, who experience two very different sides to their parents: sometimes intelligent and insightful, other times narrow-minded and impossible to reason with.

All [types of emotionally immature parents] use nonadaptive coping mechanisms that distort reality rather than dealing with it (Vaillant 2000). And all use their children to try to make themselves feel better, often leading to a parent-child role reversal and exposing their children to adult issues in an overwhelming way. In addition, all four types have poor resonance with other people's feelings. They have extreme boundary problems, either getting too involved or refusing to get involved at all. Most tolerate frustration poorly and use emotional tactics or threats rather than verbal communication to Bet what they want.

As summarized in their 1974 article, these researchers rated mothers behaviors toward their babies on four dimensions: sensitivity-insensitivity, acceptance-rejection, cooperation interference, and accessible-ignoring. They found that a mother's "degree of sensitivity" was "a key variable, in the sense that mothers who rated high in sensitivity also, without exception, rated high in acceptance, co operation and accessibility, whereas mothers who rated low in any one of the other three scales also rated low in sensitivity" (1974, 107). Ainsworth and her colleagues reported that more sensitive mothers had babies who showed more secure attachment behaviors in their experiments.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quotes from adult children of emotionally immature parents

These are passages that I've sent to myself because they stood out to me. I'm only through the first few chapters so I'll probably update with more later.

Children who feel they cannot engage their parents emotionally often try to strengthen their connection by playing whatever roles they believe their parents want them to. Although this may win them some fleeting approval, it doesn't yield genuine emotional closeness. Emotionally disconnected parents don't suddenly develop a capacity for empathy just because a child does something to please them.

People who lacked emotional engagement in childhood, men and women alike, often can't believe that someone would want to have a relationship with them just because of who they are. They believe that if they want closeness, they must play a role that always puts the other person first.

What Jake didn't realize is that hate is a normal and involuntary reaction when somebody tries to control you for no good reason. It signals that the person is extinguishing your emotional life force by getting his or her needs met at your expense.

Emotionally immature parents don't know how to validate their child's feelings and instincts. Without this validation, children learn to give in to what others seem sure about.

Like children, emotionally immature people usually end up being the center of attention. In groups, the most emotionally immature person often dominates the group's time and energy. If other people allow it, all the group's attention will go to that person, and once this happens, it's hard to redirect the group's focus. If anyone else is going to get a chance to be heard, someone will have to force an abrupt transition- something many people aren't willing to do.

It's also important to remember that old-school parenting- -the upbringing my clients' parents experienced- -was very much about children being seen but not heard. Physical punishment was not only acceptable, it was condoned, even in schools, as the way to make children responsible. For many parents, "spare the rod and spoil the child" was considered conventional wisdom. They weren't concerned about children's feelings; they saw parenting as being about teaching children how to behave. It wasn't until 1946 that Dr. Benjamin Spock, in the original version of his mega-seller The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, widely popularized the idea that children's feelings and individuality were important factors to consider, in addition to physical care and discipline. In the generations before this shift, parenting tended to focus on obedience as the gold standard of children's development, rather than thinking about supporting children's emotional security and individuality.

It may be that many emotionally immature people weren't allowed to explore and express their feelings and thoughts enough to develop a strong sense of self and a mature, individual identity. This made it hard for them to know themselves, limiting their ability to engage in emotional intimacy. If you don't have a basic sense of who you are as a person, you can't learn how to emotionally engage with other people at a deep level. This arrested self-development gives rise to additional, deeper personality weaknesses that are common among emotionally immature people, as outlined in this chapter.

Instead of learning about themselves and developing a strong, cohesive self in early childhood, emotionally immature people learned that certain feelings were bad and forbidden. They unconsciously developed defenses against experiencing many of their deeper feelings. As a result, energies that could have gone toward developing a full self were instead devoted to suppressing their natural instincts, resulting in a limited capacity for emotional intimacy.

Emotionally immature people who are otherwise intelligent can think conceptually and show insight as long as they don't feel too threatened in the moment. Their intellectual objectivity is limited to topics that arent emotionally arousing to them. This can be puzzling to their children, who experience two very different sides to their parents: sometimes intelligent and insightful, other times narrow-minded and impossible to reason with.

All [types of emotionally immature parents] use nonadaptive coping mechanisms that distort reality rather than dealing with it (Vaillant 2000). And all use their children to try to make themselves feel better, often leading to a parent-child role reversal and exposing their children to adult issues in an overwhelming way. In addition, all four types have poor resonance with other people's feelings. They have extreme boundary problems, either getting too involved or refusing to get involved at all. Most tolerate frustration poorly and use emotional tactics or threats rather than verbal communication to Bet what they want.

As summarized in their 1974 article, these researchers rated mothers behaviors toward their babies on four dimensions: sensitivity-insensitivity, acceptance-rejection, cooperation interference, and accessible-ignoring. They found that a mother's "degree of sensitivity" was "a key variable, in the sense that mothers who rated high in sensitivity also, without exception, rated high in acceptance, co operation and accessibility, whereas mothers who rated low in any one of the other three scales also rated low in sensitivity" (1974, 107). Ainsworth and her colleagues reported that more sensitive mothers had babies who showed more secure attachment behaviors in their experiments.

#adult children of emotionally immature parents#childhood emotional neglect#cptsd#childhood emotional abuse#trauma#mental health

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to a redneck pseudo-funeral type thing at a bar today. It was for my dad's landlord for many years. Someone who was considered a friend to him. I didn't really feel that connected to this person, but since my dad passed I find myself feeling like I 'should' step in to attend funerals for people when he would have gone to them.

I find funerals to be such a clear indicator of how emotionally unhealthy our society is. The way that the vast majority of funerals I've ever attended had very little crying. It's like...everyone avoids crying if they can manage to hold it in. Just the fact that even at funerals we all try not to show our emotions is...wild. It's so messed up that most of us hate crying in front of people. Crying is healthy. We all need to do it.

Words were spoken about how she wouldn't want us to be sad, and how she'd want us to focus on joy. And I totally get the good intent. Of course it's a good thing to do what you can to fully embrace the happy things in your life. But like...I don't know that a funeral should be a place where we lecture on how we should be happy and not sad, you know?

I wasn't close enough to this woman to need to cry for her specifically. But I dreaded going to this event because I knew the fact that we were going to a funeral would mean my dad would get brought up. Because even though we're 2 years out now, any and every mention of anything about death reminds me of him. And all of my siblings about him. It still feels quite new even though it's been 2 years. And I was worried that talking about my dad today would make me struggle to contain my emotions physically.

I didn't struggle with almost crying today. And I felt relieved that I didn't. But I know it's unhealthy that I feel that way. Intellectually I don't see crying as bad, at all. But I have a fairly significant issue with letting my guard down enough to let it happen for some reason. I cry fairly often, but usually just for a literal minute or two. I don't intentionally force myself to stop, I just almost never really truly cry. I shed a tear or two at most. I know something subconscious is stopping me from really letting feelings out. I just don't know what is causing it or how to fix it. Something I definitely need to work on.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once you become aware of your trauma and start healing, it becomes easier to see who treated you badly all your life and how, for them, you were sacrificing your boundaries and well being. It might become easier to place your boundaries with those people and deal with the consequences of discomfort resulting from it.

But I realised what gets tricky is when you forget that you have to keep your boundaries with all the nice people in your life too. It isn't so apparent because they are lovely and you wanna do things for them but if you sacrifice your well being for the nice people, that will hinder your healing too, it will stop you from forming healthy patterns.

I had to hold myself back for going into my people-pleasing and fixer habits for the loved ones in my life and it's harder to detect when you have a pleasant and unstrained relationship with someone. It's not something that people talk about but I just found to be true in my own experience.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big T Versus Little T Traumas

Thought I'd share what stuck out to me most from my therapy appointment a few days ago.

I continue to process childhood trauma, and at one point in this session I had brought up a time where I was blatantly emotionally abandoned when I was in very clear emotional crisis. I was around 14 at the time of this memory.

And my T asked if I remembered anything I thought or felt about this experience, if it was surprising or shocking, hurtful, if it made me angry, etc.

I didn't really remember specifics like that, and told my therapist that. But then also elaborated by saying that I didn't think it could have been particularly shocking, as it was a pattern for my mom by that point. I then listed four or five other instances of very blatant neglect when I was in a crisis. Like, your kid is metaphorically on fire, and the parents say nothing and do nothing and just pretend it didn't happen, sort of situations.

And a bit later in this conversation I said it's funny how just a couple months ago (maybe not even that far back..I Don't recall for sure) I was struggling with identifying as being emotionally neglected - because it was quite severe emotional neglect. I think emotional neglect of any "level" is valid, don't get me wrong. But it's weird that I was struggling with using the term when I was quite severely emotionally neglected. And part of that struggle is how society at large seems to not recognize 'small T' traumas as being traumatic, and also how the bubble I grew up in seems to see emotionally neglecting children, especially in more 'mild' ways, as just, normal.

For example, I know SO many people who are not authoritarian parents, and who very clearly mean well as parents, but who still feel like they can't validate their kids emotions and hold a boundary for their behavior at the same time. So many people who routinely minimize, dismiss, invalidate or avoid/distract their kids feelings rather than teaching them how to really sit with and process their feelings. Often because the parents themselves never learned how to manage their own feelings so they can't possibly teach the kid to. Emotional neglect isn't exclusive to bad parenting, it's super common with parenting from people doing their absolute best, but who just were traumatized themselves and never learned coping skills themselves. And when people really truly tried their best, they have a hard time even imagining that their kid could still have trauma from their childhoods. It feels unfair that doing your absolute best could still traumatize your kid. But I think that's the reality of how it often works. Kids are fragile, and most of us have a lot of generational trauma so even when doing our best we can't break ALL the cycles. I don't imagine I'll succeed at breaking all of mine. My absolute best won't be enough either, and I'm trying to come to terms with that now, while also balancing trying my best to heal for my future kid(s) too. But anyway...

The traumatized/mentally ill part of my brain likes to use that 'neglect is just normal' thing to invalidate me having cPTSD, basically. That part of my brain feels like I am just dramatic, and things 'weren't that bad' and so on. That part of my brain still looks at my childhood as having one type of big T trauma (sexual abuse) and that's it.

But after mentioning how it's funny that I so recently was struggling to even accept that I had experienced emotional neglect, my therapist said something about how I also have minimized how much Big T trauma I have. I was confused briefly. They pointed out that all the specific instances I had listed of blatant neglect in the face of crisis, count as big T traumas. That little t traumas are the day to day, mini 'cuts' that we don't really even remember because they were just normal tuesday things to us despite being hurtful. Things like coming home from school excited about something only to have your mom hush you rather than listen to you. Of course, this happening occasionally isn't traumatic but when kids live with dismissive or invalidating or overly critical parents regularly those mini cuts add up to cause accumulative trauma, and that's what cPTSD is about, mini cuts adding up to a wound, rather than traditional PTSD which leaves more acute injuries. They pointed out that Big T traumas are specific events that you do specifically remember, that left a specific wound. So just the fact that I was able to list these specific events means they are big t traumas, not little T.

Clearly, my therapist was right that I was minimizing them a bit because I had never considered that they are big t traumas.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oddly enough I can associate with multiple of those roles mentioned above. As a child and an adult now, I can associate between the lost child and the scapegoat roles. I have always wondered what my identity really was. Closely following everything my parents wanted, assuming that following the formula they gave I felt that I would be accepted and loved. But ofcourse that really never happened. All that did was make me lose myself. I feel like I don't know who I am anymore or what I want. Living for a long time to please my family members, in search of validation and belonging, has actually left me more lost than anything else. Life is confusing.

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trauma therapy analogy from my therapist, paraphrased by me.

It's sort of like discovering as an adult that you broke a bone as a kid, and were never given medical care for it. So it "healed" but it wasn't set properly, and it's always caused you pain. But it happened so early in your life that you've never known anything else. You just thought it was normal for your leg to ache often because yours always has. You don't have to live that way forever though...and when you start digging into trauma in therapy, you have to re-break the bone - and it hurts really badly. Things feel like they're getting worse, because this is a lot more painful than what you were used to. But now that it's broken again, you can have it set properly, and cast properly...and it'll heal better and someday cause you less pain than you've been used to all these years. It ends up being worth it...but things get worse before they get better. And that's where you're at right now.

#trauma therapy#ptsd#cptsd#developmental trauma#childhood emotional neglect#adult children of emotionally immature parents

3 notes

·

View notes