t r i l l w a v e i n t e r n e t s k e t c h b o o k d a y d r e a m m i x t a p e

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

by Patrick Prince | Feb 7, 2020

Goldmine® Grading Guide is now the most widely used guide for the buying and selling of vinyl albums; many eBay auctions and stand-alone Web sites swear by it.

Nothing is more important in determining the value of your records than their condition! Yes, their relative rarity and demand is important, but a collector or dealer will pay much more for a record in Near Mint condition than one in Very Good Minus condition.

However, I’ve found that most people with collections or accumulations have an inflated sense of the condition of their discs. I don’t know how many times I’ve heard people who think they know what they are talking about tell me, “My records are all Mint!” Sure, and I’ve got some oceanfront property in Arizona to sell you.

The truth is that most records, especially from before the 1970s, are not in anything close to Mint or Near Mint condition. That is why a collector will pay a premium for such a disc if he or she has to have it.

This book lists values for records in Near Mint condition. Records in lesser condition are worth a fraction of the Near Mint prices.

For most collectors, Very Good is the lowest grade for which they will pay more than bargain-bin prices. And some won’t even do that. Lower-grade records are only good as place holders, until a better copy comes along, or as examples of truly rare records that are difficult to find in any condition.

Most of the time, LPs are sold with two grades, one for the record and one for the cover. We list only one grade, however, because with some exceptions, albums without covers are worthless, and covers without the accompanying record are worthless. If an album is graded VG for the cover and VG+ for the record, add the two values together and divide by 2 to get a rough estimate of the value of a “mixed grade” LP.

Most records are graded visually. This is because most record dealers have lots of records — hundreds of thousands in some cases — and they don’t have the time to play their entire stock. That said, some defects are easy to see, such as scratches and warps. Others are subtle, such as groove wear from using a cheap or poorly aligned tone arm. It has been our experience that older LPs (1950s to about 1971) tend to play better than they look, and newer LPs (at least until 1989) tend to play worse than they look.

When grading your records, do so under a strong light. Look at everything carefully, and then assign a grade based on your overall observations.

Some records will be worthy of a higher grade except for defects such as writing, tape or minor seam splits. Always mention these when selling a record! For some collectors, they will be irrelevant, but for others, they will be a deal-breaker. For all, they are important to know.

Also, some LPs were made for promotional purposes only. Again, always mention if a record is a promo copy when advertising it for sale!

One of the obstacles to the further growth of record collecting is poor grading and a lack of consensus as to what constitutes a “Very Good Plus” or “Near Mint” record or cover. Over the years, the Goldmine® Grading Guide has tried to standardize this. It is now the most widely used guide for the buying and selling of vinyl albums; many eBay auctions and stand-alone Web sites swear by it. But we recognize that there are many variables to grading a record. As a seller, you are better off grading conservatively and surprising the buyer with a better record than was expected, than by grading based on wishful thinking g and losing a customer.

That said, here are the standard grades for record albums, from best to worst.

MINT (M) These are absolutely perfect in every way. Often rumored but rarely seen, Mint should never be used as a grade unless more than one person agrees that the record or sleeve truly is in this condition. There is no set percentage of the Near Mint value these can bring; it is best negotiated between buyer and seller.

NEAR MINT (NM OR M-) A good description of a NM record is “it looks like it just came from a retail store and it was opened for the first time.” In other words, it’s nearly perfect. Many dealers won’t use a grade higher than this, implying (perhaps correctly) that no record or sleeve is ever truly perfect.

NM records are shiny, with no visible defects. Writing, stickers or other markings cannot appear on the label, nor can any “spindle marks” from someone trying to blindly put the record on the turntable. Major factory defects also must be absent; a record and label obviously pressed off center is not Near Mint. If played, it will do so with no surface noise. (NM records don’t have to be “never played”; a record used on an excellent turntable can remain NM after many plays if the disc is properly cared for.)

NM covers are free of creases, ring wear and seam splits of any kind.

NOTE: These are high standards, and they are not on a sliding scale. A record or sleeve from the 1950s must meet the same standards as one from the 1990s or 2000s to be Near Mint! It��s estimated that no more than 2 to 4 percent of all records remaining from the 1950s and 1960s are truly Near Mint. This is why they fetch such high prices, even for more common items.

Don’t assume your records are Near Mint. They must meet these standards to qualify!

VERY GOOD PLUS (VG+) or EXCELLENT (E)

A good description of a VG+ record is “except for a couple minor things, this would be Near Mint.” Most collectors, especially those who want to play their records, will be happy with a VG+ record, especially if it toward the high end of the grade (sometimes called VG++ or E+).

VG+ records may show some slight signs of wear, including light scuffs or very light scratches that do not affect the listening experience. Slight warps that do not affect the sound are OK. Minor signs of handling are OK, too, such as telltale marks around the center hole, but repeated playing has not misshapen the hole. There may be some very light ring wear or discoloration, but it should be barely noticeable.

VG+ covers should have only minor wear. A VG+ cover might have some very minor seam wear or a split (less than one inch long) at the bottom, the most vulnerable location. Also, a VG+ cover may have some defacing, such as a cut-out marking. Covers with cut-out markings can never be considered Near Mint.

Very Good (VG) Many of the imperfections found on a VG+ record are more obvious on a VG record. That said, VG records — which usually sell for no more than 25 percent of a NM record — are among the biggest bargains in record collecting, because most of the “big money” goes for more perfect copies. For many listeners, a VG record or sleeve will be worth the money.

VG records have more obvious flaws than their counterparts in better shape. They lack most of the original gloss found on factory-fresh records. Groove wear is evident on sight, as are light scratches deep enough to feel with a fingernail. When played, a VG record has surface noise, and some scratches may be audible, especially in soft passages and during a song’s intro and ending. But the noise will not overpower the music otherwise.

Minor writing, tape or a sticker can detract from the label. Many collectors who have jukeboxes will use VG records in them and not think twice. They remain a fine listening experience, just not the same as if it were in better shape.

VG covers will have many signs of human handling. Ring wear in the middle or along the edges of the cover where the edge of a record would reside, is obvious, though not overwhelming. Some more creases might be visible. Seam splitting will be more obvious; it may appear on all three sides, though it won’t be obvious upon looking. Someone might have written or it or stamped a price tag on it, too.

Good (G), Good Plus (G+), or Very Good Minus (VG–) These records go for 10 to 15 percent of the Near Mint value, if you are lucky.

Good does not mean bad! The record still plays through without skipping, so it can serve as filler until something better comes along. But it has significant surface noise and groove wear, and the label is worn, with significant ring wear, heavy writing, or obvious damage caused by someone trying to remove tape or stickers and failing miserably. A Good to VG– cover has ring wear to the point of distraction, has seam splits obvious on sight and may have even heavier writing, such as, for example, huge radio station letters written across the front to deter theft.

If the item is common, it’s probably better to pass it up. But if you’ve been seeking it for a long time, get it cheap and look to upgrade.

POOR (P) and Fair (F) Poor (P) and Fair (F) records go for 0 to 5 percent of the Near Mint value, if they go at all. More likely, they end up going in the trash. Records are cracked, impossibly warped, or skip and/or repeat when an attempt is made to play them. Covers are so heavily damaged that you almost want to cry.

Only the most outrageously rare items ever sell for more than a few cents in this condition — again, if they sell at all.

Sealed Albums

Still-sealed albums can — and do — bring even higher prices than listed.

However, one must be careful when paying a premium for sealed LPs of any kind for several reasons:

1. They may have been re-sealed;

2. The records might not be in Near Mint condition;

3. The record inside might not be the original pressing or the most desirable pressing;

4. Most bizarre of all, the wrong record might be inside. I’ve had this happen to me; I opened a sealed album by one MCA artist only to find a record by a different MCA artist inside! Fortunately, I didn’t pay a lot for that sealed LP. I would have been quite upset if I had!

Imports The Goldmine® Record Album Price Guide lists only those vinyl LPs manufactured in the United States or, in a few instances, manufactured in other countries, but specifically for release in the United States. Any record that fits the following criteria is an import, and you won’t find it in the price guide:

LPs on the Parlophone label by any artist, at least before 2000. Parlophone, best known as the Beatles’ British label, was not used as a label in the United States until very recently.

LPs that have the letters “BIEM,” “GEMA” or “MAPL” on them.

LPs that say anywhere on the label or cover, “Made in Canada,” “Made in the UK,” “Made in Germany,” etc.

We have chosen not to list records from Great Britain, Canada, Japan or any other nation for logistical reasons. Where do you start, and where do you stop?

Unfortunately, we realize that there is a lack of reliable information on the value of non-U.S. records, especially published in the United States. Please don’t contact us seeking information on non-U.S. records; we cannot help.

Also unfortunately, there are few general rules about the value of an import as compared to an American edition.

Some import albums, especially well-made Japanese imports that still have their “obi strip,” can go for more than the U.S. counterpart. Others seem to attract little interest in the States.

One rule is just as true of imports as it is with U.S. records: Those discs that are originals in the best condition will sell for more than reissues and those in less than top-notch shape.

Promotional Copies Basically, a promotional record is any copy of a record not meant for retail sale. Different labels identify these in different ways: The most common method on LPs is to use a white label instead of the regular-color label and/or to add words such as the following:

“Demonstration — Not for Sale”

“Audition Record”

“For Radio-TV Use Only”

“Promotional Copy”

Some labels, of course, used colors other than white; still others used the same labels as their stock copies, but added a promotional disclaimer to the label.

Most promotional albums have the same catalog number as the regular release, except for those differences.

Sometimes, regular stock copies have a “Demonstration — Not for Sale” or “Promo” rubber stamped on the cover; these are known as “designate promos” and are not of the same cachet as true promotional records. Treat these as stock copies that have been defaced. Exceptions are noted in the listings.

All of this is mentioned as a means of identification. As a rule, we do not list promotional records separately, nor are we interested in doing so. There are exceptions, which we will list below. But we feel that the precious space in our guides is better used for unique commercially available records rather than for thousands upon thousands of promotional copies.

Most promotional LPs sell for approximately the same as a stock copy of the same catalog number. That has been our experience.

However, there are certain exceptions. Those are the kinds of promos that you’ll find documented in our price guide, and which we plan to continue to document. These include:

Colored vinyl promos.

Promos in special numbering series, such as Columbia albums with an “AS” or “CAS” prefix; Warner Bros, albums with a “PRO” or “PRO-A-” prefix; Capitol albums with a “PRO” or “SPRO” prefix; Mercury albums with an “MK” prefix; and other similar series on other labels.

Promos that are somehow different than the released versions, either because of changes in the cover or changes in the music between the promo LP and the regular-stock LP.

Promos pressed on special high-quality vinyl; these were popular in the 1980s and can bring a premium above stock copies of the same titles.

#audiophile#goldmine#goldmine grading guide#music#record collecting#record grading#record memorabilia#records#vinyl

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

To help, we’ve compiled this vinyl record collecting glossary of terms that you may find it helpful to know.

10” – Ten inch record. This size was used for both 78 RPM singles, made from the 1910s through the late 1950s, as well as long-play albums during the first years of album production (roughly 1948-1955.)

12” – Twelve inch record. While this sizes is most commonly used for modern record albums (post-1955), this size record is also used occasionally for singles and extended-play (EP) recordings.

16 2/3 RPM – A playback speed for certain record albums, most commonly used for talking books for the blind. The slow playback speed allows for extra-long playing time, though the sound quality suffers as a result. Most of the people who own record players that are capable of playing 16 2/3 RPM records have never actually seen one.

180 gram – Weight of some modern era (post-1990) record pressings, usually those titles pressed as “audiophile” records. Most 12″ records pressed in earlier eras weighed between 125-150 grams. The heavier weight of these modern pressings is thought to provide better sound and less likelihood of warping.

200 gram – Weight of some modern (post-1990) record pressings, used by some manufacturers of “audiophile” records. 200 gram records are not seen as often as 180 gram pressings, and there’s considerable debate in the audio community regarding the benefits of the additional 10% in weight, including the question of whether the added weight provides any benefits at all.

33 1/3 RPM – The speed used for nearly all long-play (LP) record albums from 1948 to the present day. This speed allows for longer playback time than the earlier 78 RPM pressing, and records at this speed usually offer up to 20 minutes of program material per side (though we’ve seen a few that played as long as 35 minutes, with reduced volume and sound quality.)

45 RPM – The speed used since 1949 for most 7″ records, and occasionally for 12″ singles. Since the mid-1990s, a few record labels have reissued older recordings that were originally pressed at 33 1/3 RPM at the 45 RPM speed for improved sound quality, though this requires more discs. A single disc album at 33 1/3 will usually take up two discs when pressed at 45 RPM.

78 RPM – Speed used from the 1910s through the late 1950s for 10″ singles. This format was rendered obsolete circa 1960 by the 45 RPM, 7″ single. Occasionally 78 RPM speeds have been used for certain promotional singles, usually as a marketing gimmick. Records pressed at this speed have had no commercial application for the past half century.

7” – Size of singles (usually one song per side) since 1949. These records normally play at 45 RPM, though a few have been released over the years that played at 33 1/3 RPM.

An example of an acetate, or lacquer.

Acetate – Also known as a lacquer, an acetate is the first step in the record manufacturing process. An acetate is a lacquer-covered metal plate upon which the music is encoded via a lathe. You can read more about acetate records here.

Album – Originally a collection of 78 RPM, 10″ singles, collected in a binder. When the long-play album, containing a number of songs on a single disc, replaced 78 RPM albums in the early 1950s, the name remained.

Today, an “album” usually refers to a collection of songs recorded together and released as a single entity, usually one one disc, but sometimes released as multiple-disc sets.

Long-play albums were originally 10 inches in size, but modern albums are 12 inches in size.

Audiophile Record – Records pressed specifically to attract the attention of buyers who want (and are willing to pay for) albums with higher sound quality than regular mass-produced pressings.

Most audiophile records are pressed on more expensive vinyl that has less surface noise, and are mastered using tapes that are as close as possible to the original master tape. These pressings are usually on heavier (180-200 gram) vinyl and are sometimes cut at 45 RPM, rather than the standard 33 1/3.

Many audiophile records are intentionally released as limited edition pressings and sell for a premium price when new.

You can read more about audiophile records here.

Binaural Record – Short-lived early attempt to press records in stereo. These records required a special tonearm with two cartridges. Due to the awkwardness of the playback process and the expense of buying a special turntable or tonearm, these records were not successful.

You can read more about binaural records here.

Bootleg Record – An album of previously unreleased material, pressed and released to the market without the knowledge or permission of the artist involved or their record company. Most bootleg records consist of previously unreleased studio recordings or live performances by popular artists.

You can read more about bootleg records here.

Bossa Nova – A form of music that originated in Brazil in the late 1950s, and popular through about 1967 or so. The music incorporated elements of samba and jazz and introduced the world to artists such as Sergio Mendes and Joao Gilberto. Many popular American artists (Frank Sinatra, Eydie Gorme, Stan Getz, and others) had success recording Bossa Nova.

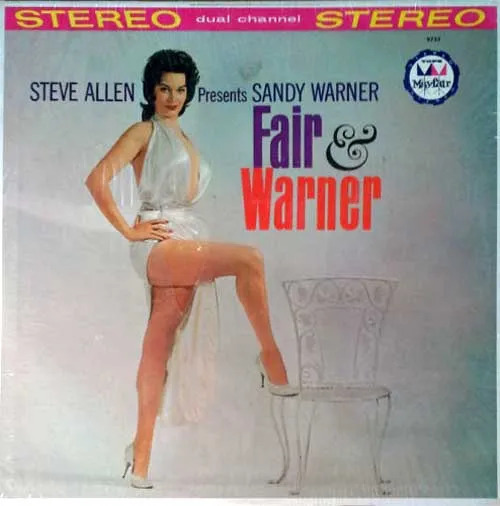

An example of an album with a “cheesecake” cover.

Cheesecake – Term usually used to describe album covers that prominently feature attractive women, often in risque poses or in minimal attire. Most often found on albums from the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Colored Vinyl – Term used to describe any record pressed from a color of vinyl other than black. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, some record companies routinely pressed records on colors other than black as a matter of course. Over time, colored vinyl records became limited to either promotional use or as limited edition releases.

You can read more about colored vinyl records here.

Counterfeit – A reproduction of a record, created by unscrupulous individuals with the intention of fooling the buyers into believing they are buying the genuine item. Most often found today with exceptionally rare titles, though in the 1970s, counterfeit copies of new releases were often mass produced and frequently found their way into major record stores.

You can read more about counterfeit records here.

Cover – The paper, cardboard, posterboard, or (rarely) plastic outer covering provided by the record company to hold a single or album. Covers usually have printed titles and often have a photo of the artist, as well as a listing of the contents of the record inside.

Cover Mouth – The portion of the cover that opens to allow for insertion and removal of the record. For albums, this is usually the right side of the cover as you look at the front. For 7″ singles, the opening is usually at the top.

CSG Process (also known as Haeco-CSG) – Short-lived process used from roughly 1968-1970 to compensate for vocals with too much volume when stereo records were played back on mono record players. CSG-encoded records were pressed during the time when monaural records were being phased out of the market.

This encoding solved the problem it was trying to fix while introducing others and was not popular with record buyers. Over time, record companies stopped using CSG encoding as the percentage of record buyers with stereo turntables increased to the point where it became unnecessary.

An example of a cutout album with a cut corner.

Cut Corner – A record album with a cover that has part of one of the corners cut off. This was done to indicate that the album had been discontinued (remaindered) and sold at a discount and that it was ineligible for a refund. While many rare records are often found with cut corners, as many of them sold poorly when new, collectors usually prefer to buy copies that do not have a cut corner.

Cutout – Known in the book industry as a “remainder,” a cutout is a record that has been deleted from a record company’s catalog and is being sold at a discount to get rid of inventory the record company no longer wants.

Cutout albums are usually defaced in one of three ways – a drill or punch hole through the cover, removing a corner from the cover, or cutting a notch in the cover with a saw. These mark the records as being ineligible for a refund and while the covers are defaced, the records inside them are usually fully intact.

Dead Wax – The area immediately outside the label of a record that contains the runout groove and matrix numbers, but no recorded music. The dead wax area of a record is usually 1/4″-1″ wide.

A record with a “deep groove” label.

Deep Groove – A ring found in the label area of some pressings from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s. This ring was an indentation, usually about 3″ in diameter, that was caused by certain types of pressing equipment. As record companies phased out that equipment by the mid-1960s, pressings with a deep groove may be indicative of original pressings, rather than later reissues.

Direct Metal Mastering (also known as DMM) – A process used in the manufacture of record albums where the music is cut to a solid metal plate, rather than a softer lacquer. There are advantages and disadvantages to this process, though many listeners prefer the sound of DMM pressings to the lacquer alternative. This process was often used in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and many records mastered using this process prominently have the letters “DMM” somewhere on the cover.

Direct to Disc – A process where the recorded material is performed live and recorded directly to acetate or lacquer, without first being recorded to magnetic tape. While the process produces better sound quality, direct to disc recording requires that an entire album side be recorded live in one take with no breaks. Direct to disc records are also, by necessity, limited edition pressings, as only a few lacquers can be cut at one time.

Double Album – An album containing two records, rather than the customary one.

Drill Hole – A hole drilled through the corner of an album (or less frequently, through the label) by a record company to indicate that the album has been discontinued and may not be returned for a refund. Most records with drill holes were sold at deeply discounted prices.

An example of a record in “Duophonic” stereo.

Duophonic – A proprietary system used by Capitol Records in the early 1960s to simulate stereo on material originally recorded in mono. Duophonic usually added a bit of a delay between the two channels and added reverberation to give a stereo effect to mono recordings.

Duophonic was created when record companies discovered that some buyers would only purchase stereo records, and it was an attempt to sell mono material to those buyers.

You can read more about Duophonic and other “fake stereo” pressings here.

Dynaflex – A short lived manufacturing process used by RCA Records from 1969 to some time in the mid 1970s. To save money, RCA developed a process to press records using less vinyl than they’d been previously using. The result was a record that was exceptionally thin, more flexible than other records, and much more prone to warpage, though less prone to damage in shipping. On their record covers and inner sleeves, RCA promoted Dynaflex pressings as an improvement in the product. Buyers disagreed, and often disparagingly refer to Dynaflex as “Dynawarp.”

Dynagroove – A process developed by RCA Records in 1963 to improve the sound of their records on low-end playback equipment. This process increased bass in quiet passages while attempting to reduce high frequency distortion. Unfortunately, this only worked on phonographs with inexpensive conical needles and not more expensive elliptical ones. Owners of more expensive turntables thought the “new” process sounded much worse than the old one.

Audiophiles were unhappy with the process and the resulting sound, and RCA discontinued it about 1970 or so.

An album in the exotica genre.

Exotica – A type of music introduced in the mid-1950s, usually attributed to Martin Denny. Exotica attempted to introduce music from Asia, the Orient, and Africa to Western listeners, and the music from this short-lived fad often included tribal chants, gongs, and the sound of birds or insects to augment the music.

The popularity of music in the Exotica genre led to lots of backyard parties with people drinking Mai Tais while standing amidst Tiki torches. By the early 1960s, people had moved on from listening to Exotica when they discovered Bossa Nova.

Extended Play – Also known as an “EP”, this term is usually used to describe a 7″ single that plays more than one song per side. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, record albums were quite expensive, and priced at the equivalent of about $50 today.

Record companies occasionally took a 12 song album and sold it as three 7″ records that had four songs each, with pricing that allowed buyers to buy one disc alone or all of them.

Extended play singles were sometimes released as standalone releases of one disc with three or four songs. While the format was quite popular in Britain, it never really caught on in the United States.

In the modern (post-1965) era, an extended play record usually describes a 12 inch record with more than two songs but fewer songs than one might find on an album.

Foxing – The appearance of brown spots on picture sleeves or album covers as they age. Foxing can occur on all kinds of paper, but it’s most visible on white paper. For unknown reasons, foxing is quite common on album covers from Japan, and probably seven out of ten Japanese albums have some evidence of it.

Foxing is not an indication of wear or mistreatment by a previous owner. An album cover can be in mint, untouched condition and still exhibit foxing. It is simply an artifact of the aging process.

Garage Rock – Raw, unpolished rock and roll from the mid-1960s, inspired by relatively inexperienced musicians who often rehearsed and sometimes recorded in their home garage. Examples include the Castaways, the Sonics, and the Standells.

Gatefold Cover – A record cover that is intended to fold open like a book. Often the inside of a gatefold cover will include lyrics, liner notes, or additional photos of the artist.

Gold Record Award – A framed, gold-plated record, usually with an accompanying plaque, created to commemorate sales of $1 million (later 500,000 copies sold.) In the United States, “official” gold record awards have an RIAA logo, indicating that that organization has certified the sales of that particular record.

These awards are usually given by a record company to the artist, the producer, and other people who were instrumental in helping the album achieve that particular sales milestone.

An example of a hype sticker

Hype Sticker – A paper or plastic sticker attached to the shrink wrap or cover of an album, usually with the intention of drawing attention to one or more songs on the album in order to increase sales. Sometimes a hype sticker will indicate that the particular record is pressed on colored vinyl, contains a poster, or is in some way special.

In-House Record Award – A gold or platinum record award that does not have an RIAA certification on it; usually created by record companies to award to their own personnel, rather than to be giving to the artist.

In the collector’s market, in-house awards usually sell for lower prices than RIAA-certified awards.

Inner Sleeve – A paper or plastic sleeve included with a record album that is intended to protect the disc from coming in direct contact with the cover, as the rough surface of the cover might damage the record.

While many inner sleeves are plain paper or plastic, sometimes inner sleeves contain lyrics or other information about that specific recording. On other occasions, record companies used inner sleeves to advertise other albums that might be of interest to the listener or to provide technical information about stereo recordings (1950s) or quadraphonic recordings (1970s.)

Insert – Any piece of paper included with an album other than a poster or inner sleeve. The most common use of inserts is to provide the listener with lyrics to that particular album.

Instrumental – A recording of music that contains no vocals. This applies to most jazz, classical, and surf music recordings.

An example of a rare jukebox EP by the Beatles.

Jukebox EP – A 7 inch extended-play record manufactured exclusively for use in jukeboxes. Jukebox EPs were primarily made in the 1960s and 1970s, and were usually pressed in stereo and often included a hard cover, similar to an album cover.

A typical jukebox EP would include three songs on each side and come with a small paper reproduction of the album cover and a half a dozen paper “title strips” to be inserted in the jukebox so that customers could select them for play.

Label – The round piece of paper in the center of a record that lists the name of the artist, the name of the album or song, the name of the record company, and other information that may be useful to the buyer or listener.

Lacquer – Another (and more correct) term for an acetate.

Live Album – Usually, an album that contains a recording of an artist performing in an “in concert” setting before a live audience. Occasionally, a recording of a band performing in a studio collectively as a band, rather than recording vocals and instruments individually.

Live albums are often released as either contractual obligations or to provide fans with something to buy during an unusually long delay between releases of studio albums by a particular artist.

Many modern live albums are not entirely live and may contain multiple overdubs added to the live recording in the studio at a later date. A few live albums released over the years weren’t live recordings at all, but were simply studio recordings with overdubbed audience sounds.

An example of an RCA Living Stereo LP.

Living Stereo – Name used by RCA Records from 1958-1963 for their stereo recordings, which often had a rich, and unusually lifelike recording quality. Many albums from the Living Stereo period in both classical and popular genres are highly valued by collectors.

LP – Technically, a trademarked term by Columbia Records (correctly printed as “Lp”) in the late 1940s to denote their then-new long-playing record format, which could theoretically play up to 26 minutes per side at 33 1/3 RPM.

Popularly, the term is most often used as a slang reference to a record album. (“Have you heard the new Metallica LP?”)

Marbled Vinyl – A record pressed from multicolored vinyl with the vinyl distributed in such a way that the record resembles marble.

Matrix Number – A stamped or handwritten number in the dead wax area of a record. Matrix numbers tell pressing plant employees which record they are making. Matrix numbers may also include an indicator as to which of a series of sequential stampers was used to make a particular record.

Monaural – A method of recording in which all of the music is contained in a single audio channel, and which may be heard through a single speaker. Until 1957, all records were monaural. From 1957-1968, most albums were sold in both mono and stereo.

You can read more about monaural records here.

An album pressed on multicolor vinyl.

Multicolor Vinyl – A colored vinyl record that is comprised of two or more colors of vinyl on a single disc.

Obi – On Japanese albums (and some singles), a paper strip, usually about 2 inches wide, that wraps around the cover. The information printed on the obi is almost always in Japanese and includes information for the buyer that may not be printed on the cover.

Historically, many buyers discarded the obi shortly after purchase, as they are easily torn. In some cases, the presence (or absence) of an obi can dramatically affect the price of the record.

Original Cast Recording – A recording of the music, score, or songs from a play, performed by the cast of that play.

Picture Disc – A record pressed from two layers of clear vinyl with a paper image or photo sandwiched in between. Picture disc albums are usually limited edition or promotional items and are often packaged in covers with a die-cut window so that buyers can see the record itself.

The sound quality of picture discs is usually not as good as conventional pressings.

You can read more about picture discs here.

Picture Sleeve – A paper sleeve included with a record (usually a 7 inch single) that has a photo or image printed on it. Picture sleeves usually also list the artist and the name of the songs. Picture sleeves are usually limited in production and many are quite collectible.

A pirate pressing of Led Zeppelin IV.

Pirate Pressing – A record that contains material that has previously been released commercially but is pressed without authorization from the artist or the record company responsible for that material.

Often casually referred to as “bootlegs,” though that term actually refers to something else.

You can read more about pirate pressings here.

Platinum Record Award – Similar to a gold record award, a platinum record award is a framed, silver-plated record, usually with an accompanying plaque, created to commemorate sales of 1 million copies of a particular album. In the United States, “official” platinum record awards have an RIAA logo, indicating that that organization has certified the sales of that particular record.

Play Hole – The hole in the center of a record that allows the record to fit over a turntable spindle. The hole and spindle keep the record properly centered on the platter so that it will play correctly.

Poster – A photographic insert included with an album that usually folds out to a size that is larger than the album cover itself. Occasionally included as a bonus with some titles, posters can often become quite rare with time, as many buyers hung them on the wall after purchase and failed to put them back in the album cover when they took them off of the wall at a later time.

Progressive Rock – A style of music popular from the late 1960s through the mid-1970s that featured long solos, fantasy lyrics and inventive song structures. Bands such as King Crimson, Yes, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and Gong are examples of progressive rock bands.

Promo-only – A record release that was created to be distributed to radio stations or other promotional outlets, but was not intended for commercial sale. Promo-only releases often consisted of previously unavailable live material or compilations of recordings by a given artist intended to promote airplay.

Sometimes, promo-only titles contained the same material as commercial releases, but may have been in a different format from the commercial title, such as being pressed as a picture disc or on colored vinyl.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, some albums that were commercially available only in stereo were released to radio stations in monaural as promo-only pressings.

A white label promotional copy of an album by Led Zeppelin.

Promotional Copy – A copy of a record that was pressed for distribution to radio stations or other promotional outlets, but were not pressed for retail sale. Most promotional copies of records have some print or indication on the label that they intended for promotional use, such as “Promotion Copy – Not for Sale” or some similar wording.

Promotional Stamp – A rubber stamped or machine stamped indicator on a record label or cover that indicates that the record is intended for promotional use only. Promotional stamps are usually used when record companies wish to use retail copies (“stock copies”) of records for promotional use.

Prototype – A record that was manufactured as an example of a potential release that was ultimately never released in that form. Prototype records are often pressed in very limited quantities and some are literally unique.

Examples of prototype records might be one-of-a-kind colored vinyl or picture disc pressings.

Provenance – The ability of a seller to demonstrate previous ownership or history of a particular record. Usually of interest to people buying unusual, one-of-a-kind items or items that are represented as being autographed by a particular artist.

Psych – Short for “psychedelic rock,” a short-lived style of rock music that was popular from roughly 1966 to 1970 that featured unusual chords, odd instrumentation, and frequently, long instrumental jams.

Psychedelic rock records were largely an underground phenomenon and many titles were privately pressed releases by artists that did not have national recognition. A number of psych records sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars today.

Examples of psych artists include the 13th Floor Elevators, Mystic Siva, and the C.A. Quintet.

An album cover with a punch hole.

Punch Hole – A hole punched by machine through the corner of an album cover. Unlike drill holes, which were rough holes made with an electric drill a punch hole is a clean hole made by a machine. Punch holes are generally larger than drill holes and were most often used by record companies to indicate that the record was intended for promotional use.

Capitol Records frequently used punch holes to designate their promotional copies. Capitol sometimes used single punch holes and sometimes a series of very small holes that spelled out either the word “free” or the word “promo” in the corner of the cover.

Quadraphonic – A short-lived audio format during the early to mid-1970s that presented music in four channel sound, as opposed to the two channels of stereo.

Quadraphonic music was available in 8-track tape, LP, and reel to reel tape formats and required a four-channel amplifier (or two stereo amplifiers), four speakers, and a turntable, reel to reel tape deck or 8-track player capable of playing back quadraphonic records or tapes.

There were at least three different quadraphonic formats for records, and all were incompatible with the others. Format wars and equipment costs prevented the quadraphonic format from becoming popular.

Collectors are interested in quad records and tapes as the mixes are often dramatically different from the stereo versions of the same albums. In the case of a few quadraphonic records, the recordings are completely different from the stereo versions.

R&B – Short for “rhythm and blues” a term used by record companies in the 1950s to describe music that was primarily marketed to African-Americans. In record collecting, R&B can describe anything from Ray Charles to Robert Johnson to Motown.

Radio Show – A program of live concert performances, audio documentaries, or programs of music and interviews with recording artists intended for radio broadcast only. Syndicated shows such as the King Biscuit Flour Hour, Metalshop, Innerview, and Off the Record are examples of syndicated radio shows.

The live shows are often sought out by collectors of a given artist, and those recordings have often been the source material for bootleg records.

A Ray Price album in rechanneled stereo.

Rechanneled Stereo – Also known as “fake stereo,” rechanneled stereo was an audio format developed by various record companies in the early 1960s to accommodate buyers who refused to purchase any records that weren’t available in stereo. See also: Duophonic

Rechanneled stereo records often created a stereo effect from monaural recordings by using frequency separation, audio delay, and added reverb to make monaural recordings sound “kind of like” stereo, usually with poor results.

Records released in rechanneled stereo usually indicated it on the cover, saying things like “Electronically reprocessed to simulate stereo.” Rechanneled stereo records nearly always sell for lower prices than their mono counterparts.

You can read more about rechanneled stereo here.

Record Grading – A description of a record in terms of its physical condition in order to accurately describe it to potential buyers.

Most record grading is done using the Goldmine system of Mint, Very Good, Good and Poor, with a + or – used to denote grades in between. Some sellers, particularly those based in the UK, use the Record Collector system which uses Mint, Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair and Poor.

Record grading is highly subjective, due to the many ways a record can be worn or damaged.

Reissue – A later, rather than original, pressing of a record. Record companies used to delete titles that were no longer selling well, but they would occasionally return a title to print if they felt it was warranted by potential sales.

Such a later pressing is known as a “reissue,” and they’re almost always less desirable to collectors than original pressings.

ROIR – A Record Of Indeterminate Origin. Another term for a bootleg recording.

Saw Mark – A cut in an album cover, usually near a corner, literally made through the use of a saw. Used to mark a record as discontinued and to indicate that it may no longer be returned for a refund.

Sealed – A record that is still encased in shrinkwrap or a factory applied bag. Record companies begn sealing records in the early 1960s in order to prevent vandalism in stores and to assure buyers that the record inside was new and pristine.

Sealed copies of out of print titles often command a premium price among collectors.

Seam Split – A tear along an edge of an album cover, usually caused by the record inside or by improperly inserting or removing the record from the cover.

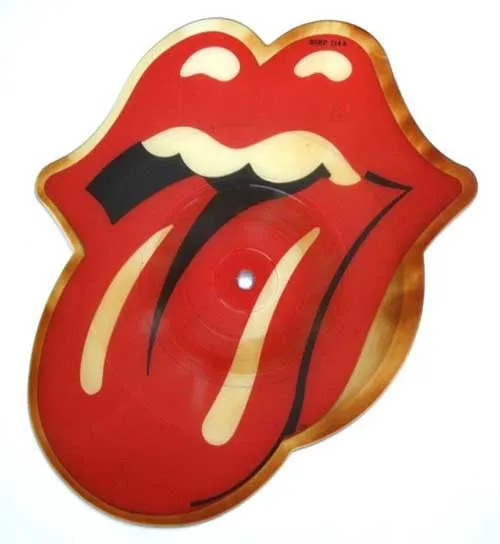

A shaped record.

Shaped Record – A record in any shape other than round. Most often found in picture discs. Shaped records start as round records but are cut using a die shortly after being pressed. Shaped records may be triangular, square, rectangular, hexagonal, octagonal or cut to a custom shape.

Single – A record containing one or two songs, usually sold on the basis of one song alone. Most often found in a 7 inch size playing at 45 RPM, singles have also been sold in 10 inch (78 RPM) and 12 inch (33 1/3 or 45 RPM) sizes.

Soundsheet – Also known as a flexi-disc, a flexible record pressed from ultra-thin plastic. Soundsheets have historically been inserted in magazines or newspapers.

Soundtrack – A recording of a score, music, songs, or dialogue from a motion picture.

Spindle Mark – A physical mark or impression on a record label caused by an inaccurate attempt to place the record on a phonograph or turntable. An abundance of spindle marks, even on a record with little apparent wear, may indicate that the record has been played excessively and may exhibit unwanted noise during playback.

A record pressed on splatter vinyl.

Splatter Vinyl – A record pressed from multicolored vinyl where the vinyl is spread across the record in a scattered, random pattern, rather than swirled, such as with marbled vinyl.

Spoken Word – A recording of someone speaking or reciting printed material, as opposed to singing.

Stamper – The metal plate used to press a record from a “biscuit” of vinyl.

Stamper Number – A number, written or stamped into the dead wax area of some records that indicates which of a sequential series of stampers was used to press that particular record.

Many collectors prefer earlier stamper numbers, either because that record was made closer to the album’s original release date or because records pressed from lower-numbered stampers often sound better than records pressed from higher-numbered stampers.

Not all record companies used user-recognizable systems for denoting stamper numbers, though there are exceptions:

Stamper numbers are easily identified on records by RCA, where the matrix number ends with a dash, a number, and the letter “S.” Example: “-1S”

Other record companies, such as Parlophone in the UK, used a coded system to identify stampers. You can read more about that system here.

Stereo – A recording format where the recorded material is presented in two distinct channels of sound, one on the left and one on the right. The de facto audio standard for records since 1968.

Stock Copy – A copy of a record that was pressed for commercial sale to the public, as opposed to a promotional copy, which was pressed for use by radio stations.

Surf Music – A style of rock music made popular during the early to mid-1960s. Surf music was originally instrumental, and featured distorted guitars with lots of added reverberation. Dick Dale and bands such as the Surfaris and the Chantays specialized in this type of music.

Instrumental surf was later augmented by adding vocals, with the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean being good examples.

Test Pressing – A copy of a record manufactured expressly for evaluation purposes by record company personnel or the artists or producers involved in the recording of that record. Test pressings are often indicated with custom labels that say “test pressing” or blank labels with no information at all.

Test pressings are often identical in sound to later stock copies of that same record, though sometimes test pressing appear on the market that contain earlier versions of songs or songs that were eventually discarded before the album was released.

A promotional copy of an album with a timing strip.

Timing Strip – A strip of paper, usually 2 to 4 inches in width and about 12 inches wide, that appears on the covers of promotional copies of many albums from the 1960s.

This strip usually listed all of the song titles on the album, publishing information, and the running times of the songs.

Sometimes a timing strip included a checkbox next to each song title that allowed a radio station’s program director or disk jockey to indicate which songs they preferred to use for airplay.

Title Sleeve – A paper sleeve for a 7 inch single that has the name of the artist and the title of the song(s) printed on it, but not a photograph.

Similar to a picture sleeve, but without the photo.

UHQR – Ultra High Quality Record, a proprietary type of record pressed by JVC in Japan in the early 1980s. The UHQR was distinguished by its then-heavy 200 gram weight and its unusual “flat” profile in that the record had uniform thickness across its entire surface, where most records were thicker in the middle than they were at the edges.

Only a handful of UHQR titles were ever pressed, and as far as we know, such titles were only released by Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, Reference Recordings, and Telarc. All are highly collectible.

Vinyl – Within the record collecting community, “vinyl” has multiple meanings. It can refer to the physical material used to manufacture a record, but it can also refer to the record format generically, as in, “I’m not going to buy Abbey Road on compact disc; I prefer to buy it on vinyl.”

Wax – Slang for vinyl; usually used by older collectors. “Red wax” and “red vinyl”, for example, are synonymous.

White Label Promo – A promotional copy of a record distinguished by having a white label with promotional indications on it (“Promotion Copy – Not for Sale”) that is distinctly different from the stock copies of the same record, which were sold with colored labels.

You can read more about white label promo records here.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Now’s The Time, Pencil on wood, 1985.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gangsta Boo ❧ Lola Chantrelle Mitchell August 7, 1979 - January 1, 2023

#black women#gangsta boo#hip-hop#hypnotize camp posse#hypnotize minds#lady boo#lola mitchell#memphis#music#qom#tennessee#three 6 mafia#where dem dollas at#yeah hoe

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary Dee Dudley, la première femme disc-jockey afro-américaine, 1948.

115 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Stereo Williams

She was going to be Motown's first Hip-Hop star. In the late 1980s, the iconic label was pushing for a resurgence. They'd signed a plethora of young R&B acts like The Boys, Today and The Good Girls. Motown was staking a claim to the new jack swing era, but it also needed to make some noise in rap music. MC Trouble signed in late 1989; primed to be a breakout for the label.

LaTasha Rogers was a Los Angeles native who was looking to become a part of a new wave of women in Hip-Hop. The late 1980s saw an explosion of female stars in the famously male-dominated genre of rap music. Salt-N-Pepa had broken big with "Push It" and their debut album Hot, Cool & Vicious and a host of women had emerged in their wake: among them were brash Brooklyn teen MC Lyte, U.K. transplant Monie Love, and New Jersey's Queen Latifah. Alongside groups like J.J. Fad and Oaktown's 357, women were making major noise. On top of that, the West Coast had become a viable locale for rap success. After years of New York City's dominance, California rap by artists like Too $hort, N.W.A. and MC Hammer was selling big.

It was into that climate that MC Trouble landed in the late 1980s.

Meanwhile, Motown was rejuvenating its image under new chief Jheryl Busby. Busby had been the head of Black music at MCA for years, shepherding the careers of chart-toppers like New Edition and Jody Watley. In 1988, Motown founder Berry Gordy sold Motown Record Corporation for $61 million to a Boston venture capital concern and MCA Records; and Busby took over as President. At Motown, Busby wanted to bring the classic house of Hitsville into a more modern era; and in the late 1980s, that meant diving headfirst into new jack swing R&B and Hip-Hop. MC Trouble had originally intended to pursue a career as a singer, but focused on rapping after a local DJ heard her rhyme. Now, she was set to be Motown's first major foray into rap music. The label first pushed the teenager via the What Does It All Mean compilation. Released in 1989 via Motown with Greg Mack of KDAY 1580, the project was meant to announce Motown's new wave.

youtube

New Motown artists including MC Trouble, Today, The Good Girls and The Boys went out on the road in 1990 as the Motor Town Revue, a throwback approach meant to evoke the label's 60s heyday while highlighting its new talent. MC Trouble had appeared on Texas rapper Jazzie Redd’s single “Think” from his 1990 album Spice of Life; and she released her first major single "I Wanna Make You Mine" later that year. The song featured The Good Girls and the video became a major fixture on BET's Rap City.

Working alongside LA Jay, Trouble would produce or co-produce the majority of her debut album, and Get A Grip dropped in the summer of 1990, a collection of new jack-driven radio tunes and topical message raps.

The album's second single was the socially-aware "Gotta Get A Grip" and the up-and-coming rapper was suddenly being compared to contemporaries like Queen Latifah and Nefertiti.

On the road, she'd become a major draw amongst the new Motown artists. And she became especially close with The Good Girls. “I loved performing on stage with her," Joyce Tolbert of The Good Girls said in 2020. "I could watch the crowd and have fun, I [really] love, love it and my favorite was performing with her.”

youtube

Get A Grip was only a moderate success but a promising first step for both MC Trouble and her new-to-rap record label. Motown urged her to get into the studio for a follow-up and already had a title before the project even began: Trouble In Paradise. She reportedly despised the title and wanted to take her own creative direction, but nonetheless began work on her project in the summer of 1991.

It was while working on her sophomore album that Latasha Rogers suffered an epileptic seizure on June 1, 1991. She was at a friend's home and had the seizure in her sleep. Rogers had suffered from epilepsy her entire life and had to endure daily treatments. The label was reportedly unaware of Rogers' condition; nonetheless, she slipped into a coma and was pronounced dead shortly thereafter. Latasha Rogers was just 20 years old.

As word spread of MC Trouble's death, tributes began across the world of urban music. A Tribe Called Quest's 1991 track "Vibes 'n Stuff" features group member Phife Dawg's salute to her, ("I'm out like Buster Douglas. Rest in peace to MC Trouble."); and Nefertiti released "Trouble In Paradise" as an ode to the young emcee. Her labelmates The Boys also released the rap song "You Got Me Cryin'" about their fallen friend. And Boyz II Men, who signed to Motown just before Trouble's death, paid homage to MC Trouble with the music video for their hit single "It's So Hard To Say Goodbye."

“She was a beautiful soul and a superstar she would have been an active person, in the community a very strong young woman with a vision in mind," Tolbert said. "Trouble would have created some positive movement within our youth and our communities and schools through music and her voice."

youtube

#berry gordy#black women#hip-hop#jj fad#latasha rogers#mc lyte#mc trouble#monie love#motown#music#new jack swing#oaktown's 357#queen latifah#rap#rap city#rock the bells#salt-n-pepa#the good girls#women

6 notes

·

View notes

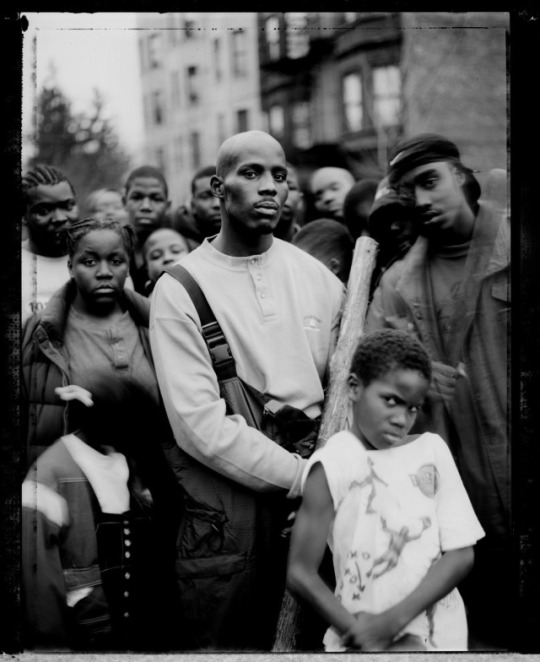

Text

DMX, Yonkers, NY, 1997 | Jonathan Mannion

7K notes

·

View notes

Link

When you think of grunge, do you picture a bunch of long-haired White guys in plaid shirts, singing about teenage angst and self-loathing? Time to expand that viewpoint. Standing above them all should be Tina Bell, a tiny Black woman with an outsized stage presence, and her band, Bam Bam. It’s only recently that the 1980s phenom has begun to be recognized as a godmother of grunge.

This modern genre’s sound was, in many ways, molded by a Black woman. The reason she is mostly unknown has everything to do with racism and misogyny. Looking back at the beginnings of grunge, with the preconception that “everybody involved” was White and/or male, means ignoring the Black woman who was standing at the front of the line.

Bam Bam was formed as a punk band in 1983 in Seattle. Bell, a petite brown-skinned spitfire with more hairstyle changes than David Bowie, sang lead vocals and wrote most of the lyrics. Her then-husband Tommy Martin was on guitars (the band’s name is an acronym of their last names: Bell And Martin), Scotty “Buttocks” Ledgerwood played bass, and Matt Cameron was on drums. Cameron would leave the band in its first year and go on to fame as the drummer for Soundgarden and Pearl Jam. But he paid homage to his beginnings by wearing a Tina Bell T-shirt in a photoshoot for Pearl Jam’s 2017 Anthology: the Complete Scores book.

“For some reason a couple of skinheads are up front, calling her [the N-word] And all of the sudden, Bell grabs a microphone stand and she starts swirling it around her head like a lasso… She swung that fuckin’ thing around her head and about the fourth time, she smashed that son of a bitch.”

Bam Bam’s sound straddled the line between punk and something so new that it didn’t have a name yet. Their music combined a driving, thrumming bass line; downtuned, sludgy guitars; thrashy, pulsing drums; melodic vocals that range from sultry to haunting to screamy; and lyrics about the existential tension of trying to exist in a world not designed for you. The band’s 1984 music video for their single “Ground Zero” is low-budget, but Bell’s charisma seeps through.

“She was fucking badass. That’s all there is to it. She was amazing as a performer. I’ve only seen one White male lead singer command the stage in a similar way that Tina Bell did, and that was Bon Scott of AC/DC,” says Om Johari, who attended Bam Bam shows as a Black teenager in the ’80s and who would go on to lead all-female AC/DC cover band Hell’s Belles.

youtube

Christina King, a Seattle scenester who was close friends with Bell from 1984 until the early ’90s, says the singer’s talent was obvious. But she believes a lot of people dismissed Bell as a gimmick.

Among those attending their shows: Future members of grunge bands like Nirvana (Kurt Cobain did a stint as a Bam Bam roadie), Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam.

“I remember one person saying to me that they didn’t get ‘the whole Black girl singer thing,’ it just didn’t fit whatever they were into,” says King. “They were too ahead of their time.”

Bam Bam came into being in an era when hundreds of underground clubs, taverns, bars, and social halls — anywhere that you could cram in a band — were within the Seattle city limits. Bam Bam played almost all of them, and often to big crowds: The Colourbox, Crocodile Lounge, Gorilla Gardens, Squid Row — just to name a few.

Among those attending their shows: Future members of history-making grunge bands like Nirvana (Kurt Cobain did a stint as a Bam Bam roadie), Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam. Not to mention all the other people, mostly White and male, who would become prime targets for music labels trying to market this new sound.

Bell “already possessed everything they were trying to attain. She had a truer rock and roll spirit than almost any of those guys in that town. Everything they tried to do, she naturally was,” says Ledgerwood, still a loyal bandmate.

One Seattle club, The Metropolis, became “like our fucking living room,” says Ledgerwood. It was also the site of an overtly racist verbal assault against Tina Bell.

“For some reason a couple of skinheads are up front, calling her [the N-word],” Ledgerwood recalls. “And all of the sudden, Bell grabs a microphone stand and she starts swirling it around her head like a lasso… She swung that fuckin’ thing around her head and about the fourth time, she smashed that son of a bitch… She nailed that fucker right in the temple of his head. Split like a melon. And the other guy next to him caught it too, they go down, and we’re like, ‘What the fuck?’”

Ledgerwood says that after going backstage for a while to regroup, Bell came back “and put out the most blistering set of our fucking career.”

This could easily be an anecdote about Bell’s power, her resilience, and willingness to fight back against oppressive forces. But it’s also a story about the cost of being a Black woman who does something that some people don’t expect or approve of.

“She’s being pulled out of her zone because somebody is acknowledging how the rest of the world can see her,” says Johari, empathizing with the star rocker. “And even to react to it by picking up a microphone and smashing someone in the face, that means that that incident cost her not only that moment it takes to get back into the song, but the whole [effects of her] action will last for weeks.

“She’ll replay that over and over and over and over again. And then the people she sees that were there when it happened, they’re gonna come up to her and they’re gonna forget everything that she’s saying, all the stuff that she had did, and they’re only going to focus on, ‘I was at that show where you knocked a dude in the head for calling you an N-word,’” Johari says. “It has nothing to do with her artistry. But it reminds her of the way in which she has to be prepared, just in case it happens again.”

King remembers Bell also felt that some of the other men in the band’s changing lineup failed to treat her as an equal partner: “She’s getting that from her own band members — what do you think audience people are like?”

A European tour in the late ’80s gained Bam Bam international fans, but ended after Bell and Martin split up, and Bell was caught in an immigration enforcement dragnet in the Netherlands.

When they returned to the Pacific Northwest, Bam Bam continued playing shows until 1990, when Bell abruptly quit as they were packing up to head to the studio in Portland, Ore.

“She had just had enough,” Ledgerwood says. “For almost eight years she had almost literally eviscerated herself for the audience.”

But that work never resulted in the national recognition they deserved.

“Grunge, whatever that means, is being identified as from your community, your colleagues, your sound that you were a participant in help shaping, and you’re not even mentioned in any of it.”

“Sometimes you need to be a little bit of an asshole to protect yourself. And Bell wasn’t much of an asshole,” Ledgerwood adds. “She was a pure-hearted person and had a really hard time believing that people couldn’t accept her over something as stupid as race.”

Bell didn’t just quit the band, she withdrew from music completely, says her son, Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker TJ Martin. Not out of resentment, he adds, but perhaps to escape the painful reminders that the music she helped pioneer was now earning other bands multimillion-dollar record contracts.

“Grunge, whatever that means, is being identified as from your community, your colleagues, your sound that you were a participant in help shaping, and you’re not even mentioned in any of it,” Martin says. “I can’t even fathom what that would feel like for it to be sort of spit back in your face with such frequency.”

Ledgerwood believes Bell died of a broken heart. But when Bell died alone in her Las Vegas apartment in 2012, the official cause of death listed was cirrhosis of the liver. She had struggled with alcohol and depression. Her son says the coroner estimated her time of death as a couple weeks before her body was discovered. She was 55 years old.

The things that could have told Tina Bell’s story in her own voice are lost. Martin arrived in Las Vegas to find that the contents of his mother’s apartment — except for a DVD player, a poster, and a chair — had been thrown away. All of her writings — lyrics, poems, diaries — along with Bam Bam music, videos, and other memorabilia — went in the trash without her family even being notified.

If you think you were in Seattle in the ’80s, in the grunge scene, and you don’t remember Tina Bell and Bam Bam, you probably weren’t really fucking there.

“I couldn’t help draw a parallel between her not being respected and seen in the first chapter of her life, as the front person of a punk band, and then even in death being disrespected and not being seen for the merits of the life she lived,” says Martin.

Bell’s death is also an indictment of the way she was written out of her own story. The way grunge’s almighty gatekeepers chose to look through her instead of at her. Grunge became the domain of alienated young White men in flannel shirts, and Tina Bell didn’t fit the narrative they were trying to sell.

“Black herstory can suffer immense amounts of erasure if somebody is not brave enough to ensure that women get counted,” Johari says.

To many of those who were part of the scene at the time, the amnesia seems intentional. Ledgerwood brings up the seminal history of Seattle’s grunge era, Everybody Loves Our Town. In it, the author refers to Bam Bam as a three-piece instrumental band mainly notable because Matt Cameron was the drummer. Tina Bell isn’t even mentioned.

“How in the hell would he have a recollection of how great Bam Bam and its drummer was, and not this unbelievably beautiful woman, this firecracker, this explosive rock and roll goddess?” Ledgerwood asks. “Even if he thought she sucked, to not remember the only Black woman on the whole fuckin’ scene is — well, it’s like that old joke about the ’60s: If you think you were in Seattle in the ’80s, in the grunge scene, and you don’t remember Tina Bell and Bam Bam, you probably weren’t really fucking there.”

You can listen to more of Bam Bam’s music on this Spotify playlist. A vinyl album with the band’s songs is coming out this year on Bric-a-Brac Records.

#Alice in Chains#Bam Bam#black history#black women#black women in rock#grunge#Kurt Cobain#music#Nirvana#Pearl Jam#rock#Seattle#Soundgarden#Tina Bell#women in rock#women's history#80s

302 notes

·

View notes

Link

'The Macarena' and the History of Viral Dance Music That Predicted TikTok

It’s played at weddings, at school dances, at concerts after doors open, at rodeos, at senior nights, at birthday parties, at ball games, at bar and bat mitzvahs, at dive bars where dancing is encouraged. For years, it was inescapable, now less so—but it emerges every once in a while, yielding its unpretentious head, ready to help the rhythmically challenged engage in a communal dance without revealing their uncoordinated secrets. There are no foot movements, after all, leaving its practitioners to rely entirely upon the flailing of their arms and hips.

The Macarena, notable for its easily learned and reproduced dance moves—and the 1993 song “Macarena” that inspired the choreography—became a staple of 1990s popular culture, dubbed by VH1 as the greatest one-hit wonder of all time and the hottest dance craze to hit the United States since “The Twist” in the 1960s. Nearly 30 years removed, the success of the “Macarena” is as confounding now as it was then: a song and dance with a name many Anglophone Americans couldn’t even pronounce, as immortalized in a particularly nostalgic episode of Oprah, that nonetheless became ubiquitous. The “Macarena” does, however, offer the perfect blueprint for our modern reality: one obsessed with dance trends, the comforts brought forth by a physical suspension of outside pressures, and a distraction from the current moment. There’s a reason the most popular version of the “Macarena,” a remix, begins with simple synths counting in the dancer and a sample of Alison Moyet’s laugh. It is an entreaty to have fun.

youtube

The folklore is well-documented. In 1992, Antonio Romero Monge and Rafael Ruiz Perdigones, who together formed the then-middle-aged Spanish pop duo Los del Río, traveled to Venezuela to perform, where they saw and became entranced by a flamenco instructor, Diana Patricia Cubillán Herrera. Monge, inspired by Herrera’s choreography, sang the chorus of the “Macarena,” that night—“¡Diana, dale a tu cuerpo alegría y cosas buenas!’” or “Give your body some joy, Diana!”—eventually changing “Diana” to “Macarena,” as an homage to Monge’s daughter, Esperanza Macarena.

According to Vanity Fair España, the track became “La Macarena,” a flamenco tune that exploded in Spain as the song of the summer—a hit, finally, after 30 years of performing together. But that version isn’t the most familiar: Their record company, having been acquired by U.S. major label RCA Records, requested a “more disco” version of “La Macarena,” and so it received a remix. In 1994, Florida producers The Bayside Boys kept the chorus, emphasized the beat, and, most critically, sanitized and translated the lyrics into English. Consider it a ’90s precursor to 2017's “Despacito”—Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee’s hit in Latin America that broke stateside once Justin Bieber added his English-language verses to a remix.

The new “Macarena” exploded on cruise ships and in clubs in Miami. Soon, the dance, created by Black American choreographer Mia Frye for the music video, was everywhere. In 1996, the song hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, where it stayed for 60 weeks total, at the time the longest run for any song ever. The cultural impact of the “Macarena” only continued to explode, transcending radio play to enter politics: Long before nerdy Pete Buttgieg supporters were transforming the anthemic theatrics of Panic! at the Disco’s “High Hopes” into a disturbing presidential campaign dance, the “Macarena” was used for relatability at the 1996 Democratic National Convention. (There’s an image of Al Gore so memorable it would inspire meme-ing, were it to have occurred two decades later.) Los del Río and The Bayside Boys had created a phenomenon, born out of stellar marketing and an addictive, repetitive hook, like so many hits before it. They just happened to do it with a dance, Frye’s dance—a magnanimous one, easy enough to learn in a few minutes, fun enough to distill the day’s worries. Hands out, palms up, behind the shoulder, behind the head, on the hips, shake the hips, repeat again.

And most didn’t know either groups’ name. Or the name of dance’s creator.

The “Macarena” offers the perfect blueprint for our modern reality: one obsessed with dance trends, the comforts brought forth by a physical suspension of outside pressures, and a distraction from the current moment.

In the 1990s, few songs created dance crazes so ubiquitous that the choreography equated the success of the single. The “Macarena” arrived a decade after Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” whose iconic zombie moves of the music video remain burned in pop culture’s collective memory, and nearly two decades after “Electric Slide” and Village People’s “Y.M.C.A.” But its closest precedents included “The Chicken Dance,” penned by Swiss musician Werner Thomas in the 1950s (then called “Der Ententanz,” or “The Duck Dance”) before music producer Stanley Mills made it a hit stateside in the 1990s with an English language cover (sound familiar?) could be viewed as a hokey grandparent to the “Macarena,” much like, well, the “Hokey-Pokey”—another vintage dance craze with ambiguous origins.

And while the “Macarena” is an outlier, it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Following its phenomenon, Latin pop crossed over to the United States—after the success and tragic murder of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, artists like Shakira, Enrique Iglesias, Marc Anthony, and Menudo’s Ricky Martin broke through, frequently re-recording their Spanish-language hits into English at the turn of the millennium. Audiences wanted music that sounded “Latin,” even if it wasn’t in Spanish, and “Macarena” was the precursor of that curiosity. And like all successful, successive musical moments, it wasn’t immediately embraced. “It really is the Latino payback for the bunny hop. It’s also the first serious challenge to ‘A Horse with No Name’ as the century’s largest musical black hole,” wrote Matthew Alice in the San Diego Reader in 1996. “The Macarena is dangerous. I think they’re testing it on lab rats even as we speak.”

Audiences wanted music that sounded “Latin,” even if it wasn’t in Spanish.

Eventually, the “Macarena” faded. The song and dance moved from “ridiculously popular” to “obsessively repetitive,” and popular interest waned, due to radio overplay. No choreography inspired the same kind of admiration until the year 2000, when Chicago MC DJ Casper, also known as Mr. C the Slide Man, released the “Cha-Cha Slide”—a song originally written for an aerobic workout, so, with easily recreated moves—simpler than “The Electric Slide,” and later, the “Cupid Shuffle,” but addicting all the same. In 2021, both the “Macarena” and the “Cha-Cha Slide” emerge at weddings—or wherever there’s a desire to dance with limited skills—but the height of popularity outside of these settings has passed.

youtube

I’ve been thinking about the “Macarena” now that there is, once again, another palpable, modern obsession with dance. TikTok has not only popularized choreography, it’s nearly demanded it from any celebrity (or celebrity hopeful) who choses to engage with the platform: many viral “challenges” are dances; songs (and the musicians who perform them) become hits largely because of how easily parodied the moves are. Doja Cat, and her “Say So” dance—bolstered by TikTok star Haley Sharpe and Laura Dern’s daughter Jaya Harper—is proof enough. There are countless others, ranging in genre, but the success of the dance is usually based on its simplicity—just like the “Macarena”—and its ability to be recreated.

The first major TikTok dance trend I can recall is the “Renegade,” choreography created by Jalaiah Harmon, a 14-year-old Black girl from Atlanta, who quickly found her dance stolen from her: co-opted by brands, verified users, celebrities, and even the NBA, which invited white TikTok creators to teach cheerleaders the popular dance. Unfortunately, Harmon is just one of many young Black creators online who’ve had their ideas taken from them: the dance is known, her name as its originator less so. There are similarities in the story of the “Macarena”: artists of color getting effectively written out of, or forgotten next to, their own art—for Los del Río and Mia Frye. But Harmon’s case is much direr. It is a direct representation of TikTok’s failings, how the platform routinely marks content from Black Americans as objectionable, according to The Washington Post.

It’s not just Harmon: the future success of Black TikTokers is limited to discriminatory gatekeeping. When dance, a bodily art form, becomes a trend, it can act as a microcosm of a racist industry. And those fads fade even faster, now, then the “Macarena,” and they never reach the same level of ubiquity. The “Renegade” feels like ancient history.

youtube

It is unlikely that TikTok will produce a “Macarena.” (Partially, it’s because they are solitary acts—dancing alone or with a few friends in front of an iPhone camera instead of being made to join in a group of strangers completing the choreography at a sporting event. The isolation makes it unlikely to inspire those outside the TikTok generation to participate, thus limiting its appeal to other demographics.) But there are clearer obstructions: competition is continuous; there are simply too many dances vying for the same viral success. The accelerated pace of the platform far exceeds the channels responsible for making the “Macarena” a hit—radio and television versus the endless void of online choices.

And yet, the “Macarena” endures in some ways that are visible in TikTok dance trends. It offers a template for future movers: keep it simple, stupid, and create choreography that appeases everyone. If it does, they will dance.

#90s#bayside boys#cha cha slide#chicken dance#choreography#cupid shuffle#dance#despacito#electric slide#hokey pokey#internet#jalaiah harmon#los del rio#macarena#mia frye#michael jackson#music#pop#renegade#selena#TikTok#thriller#village people#viral dance#ymca

0 notes

Photo

222 notes

·

View notes

Link

"The United States vs. Billie Holiday" is so misguided that it's hard to know where to start griping about it. It wallows in cruelty, misery, and degradation without providing insight into the historical personages who are so thoughtfully depicted by its cast. In the title role, singer Andra Day inhabits Holiday with such intensity that she partially redeems the movie. But there's a major caveat: you'll likely spend the whole running time wishing Day had been given a vehicle with more to say about Holiday than this one, the gist of which can be summed up as, "That poor junkie sure could sing."

Directed by Lee Daniels and written by Suzan Lori-Parks, "The United States vs. Billie Holiday" is a film about a brilliant artist and drug addict that seems less interested in the art than in the pornographically exact details of the addiction (and the self-damage that often comes with it, such as alcoholism, self-destructive/abusive relationships, and sexually compulsive behavior). If you called the movie up on Hulu, its debut streaming platform, hoping to watch facsimiles of Holiday and her bandmates, lovers, and hangers-on tying off and shooting up, often with closeups of needles going into arms (and in one case, blood spurting from an injection hole), you won't be disappointed. This is also your movie if you want to watch men beating each other up over women, men beating women up over men, Black people selling out and exploiting other Black people for clout or money, and an array of cardboard cutout white authority figures tormenting the Black characters.

The poker-faced Caucasoid sadists in the film (led by Garrett Hedlund's Harry J. Anslinger, the first chief of the U.S. Treasury Department's Bureau of Narcotics, an outspoken racist who believed jazz was jungle music and a corrupting influence on whites) don't so much incarnate the ugliness of white supremacy in mid-20th century America as give viewers heels that they can boo. Anslinger even makes a point of showing up in person at key points in the narrative of torment that he has authored for Holiday, as punishment for daring to continue singing her anti-lynching ballad "Strange Fruit" after being warned not to. Holiday lost her cabaret license in a drug bust, and was targeted again in a subsequent bust that biographers agree was based on planted narcotics.