#(flanagan explain)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hello ranger’s apprentice fandom can we talk real quick about the stupidest thing Flanagan ever wrote

It’s about the bows. Yanno, the rangers’ Iconique™️ main weapon. That one. You know the one.

Flanagan. Flanagan why are your rangers using longbows.

“uh well recurve arrows drop faster�� BUT DO THEY. FLANAGAN. DO THEY.

the answer is no they don’t. Compared to a MODERN, COMPOUND (aka cheating) bow, yes, but compared to a longbow? Y’know, what the rangers use in canon? Yeah no a recurve actually has a FLATTER trajectory. It drops LATER.

This from an article comparing the two:

“Both a longbow and a recurve bow, when equipped with the right arrow and broadhead combination, are capable of taking down big game animals. Afterall, hunters have been doing it for centuries with both types of bows.

However, generally speaking and all things equal, a recurve bow will offer more arrow speed, creating a flatter flight trajectory and retain more kinetic energy at impact.

The archers draw length, along with the weight of the arrow also affect speed and kinetic energy. However, the curved design of the limbs on a recurve adds to its output of force.”

It doesn’t actually mention ANY distance in range! And this is from a resource for bow hunting, which, presumably, WOULD CARE ABOUT THAT SORT OF THING!

Okay so that’s just. That’s just the first thing.

The MAIN thing is that even accounting for “hur dur recurves drop faster” LONGBOWS ARE STILL THE STUPID OPTION.

Longbows, particularly and especially ENGLISH longbows, are—as their name suggests—very long. English longbows in particular are often as tall or taller than their wielder even while strung, but especially when unstrung. An unstrung longbow is a very long and expensive stick, one that will GLADLY entangle itself in nearby trees, other people’s clothes, and any doorway you’re passing through.

And yes, there are shorter longbows, but at that point if you’re shortening your longbow, just get a goddamn recurve. And Flanagan makes a point to compare his rangers’ bows to the Very Long English Longbow.

Oh, do you know how the Very Long English Longbow was mostly historically militarily used? BY ON-FOOT ARCHER UNITS. Do you know what they’re TERRIBLE for? MOUNTED ARCHERY.

Trust me. Go look up right now “mounted archery longbow.” You’ll find MAYBE one or two pictures of some guy on a horse struggling with a big stick; mostly you will actually see either mounted archers with RECURVES, or comparisons of Roman longbow archers to Mongolian horse archers (which are neat, can’t lie, I love comparing archery styles like that).

Anyway. Why are longbows terrible for mounted archery? Because they’re so damn long. Think about it: imagine you’re on a horse. You’re straddling a beast that can think for itself and moves at your command, but ultimately independently of you; if you’re both well-trained enough, you’re barely paying attention to your horse except to give it commands. And you have a bow in your hands. If your target is close enough to you that you know, from years of shooting experience, you will need to actually angle your bow down to hit it because of your equine height advantage, guess what? If you have a longbow, YOU CAN’T! YOUR HORSE IS IN THE WAY BECAUSE YOUR BOW IS TOO LONG! Worse, it’s probably going to get in the general area of your horse’s shoulder or legs, aka moving parts, which WILL injure your horse AND your bow and leave you fresh out of both a getaway vehicle and a ranged weapon. It’s stupid. Don’t do it.

A recurve, on the other hand, is short. It was literally made for horse archers. You have SO much range of motion with a recurve on horseback; and if you’re REALLY good, you know how to give yourself even more, with techniques like Jamarkee, a Turkish technique where you LITERALLY CAN AIM BACKWARDS.

For your viewing enjoyment, Serena Lynn of Texas demonstrating Jamarkee:

Yes, that’s real! This type of draw style is INCREDIBLY versatile: you can shoot backwards on horseback, straight down from a parapet or sally port without exposing yourself as a target, or from low to the ground to keep stealthy without banging your bow against the ground. And, while I’m sure you could attempt it with a longbow, I wouldn’t recommend it: a recurve’s smaller size makes it far more maneuverable up and over your head to actually get it into position for a Jamarkee shot.

A recurve just makes so much more SENSE. It’s not a baby bow! It’s not the longbow’s lesser cousin! It’s a COMPLETELY different instrument made to be used in a completely different context! For the rangers of Araluen, who put soooo much stock in being stealthy and their strong bonds with their horses, a recurve is the perfect fit! It’s small and easily transportable, it’s more maneuverable in combat and especially on horseback, it offers more power than a longbow of the same draw weight—really, truly, the only advantage in this case that a longbow has over the recurve is that longbows are quicker and easier to make. But we KNOW the rangers don’t care about that, their KNIVES use a forging technique (folding) that takes several times as long as standard Araluen forging practices at the time!

Okay.

Okay I think I’m done. For now.

#to be VERY clear. I Am Not An Actual Expert.#i AM however drawing from my own experience and research#and literally i can find Zero literature about recurve arrow flights dropping faster than longbows#all i could find was that recurve range is worse compared to compound bows#which. OBVIOUSLY. compound bows CHEAT.#(said lovingly. ish. if you use a compound more power to you but also It’s Doing All The Work For You.)#this article was literally all i could find from a couple hours’ search comparing recurves and longbows#anyway recurves are cool. flanagan why did you do recurves so dirty.#for that matter why are all your women blonde.#(i’m not including brotherband here sorry)#(but also why did it take a spinoff series for him to create a named female character that wasn’t a blonde)#(flanagan explain)#god these books have so many problems. truly this is my ‘i could fix him’#thank you flanagan for getting me into this special interest. now Tell Me Why You Did It Wrong.#rangers apprentice#anyway if you REALLY want to read about some bangin historical horse archers#look up the parthians :)#specifically how they fucking Decimated an entire roman contingent :)#crassus getting absolutely demolished by mounted archer parthians is definitely my favorite bit of roman trivia

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a dream with Crowley in it the other day, where he was working at McDonald's and some shit happened and eventually when he was off his shift he grabbed a McDonald's meal from some guys that left it there because of the shit that happened and then when we were sitting down and eating it those same guys came back and mugged us for McDonald's.

Then I woke up and cried about Freddie mercury.

#it was weird#and also im too lazy to explain everything because its kinda confusing#rangers apprentice#ra#ranger's apprentice#ra memes#ranger apprentice#john flanagan#crowley meratyn

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having recently discovered discourse on The Haunting of Hill House (2018) and recently rewatching the series and then watching episodes with commentary, I just feel the need to weigh in.

First off: I have read titular book multiple times before this show was even made. It was the first book I was assigned in college that I enjoyed, so when I have opinions about the show, it is not something I haven't weighed against the book.

Secondly: When Amblin approached Flanagan about making this show, Flanagan stated that great adaptations of the book had already been made in 1963 and 1999 with the movies. He didn't pitch the idea to someone, it was pitched to him. Yes, he came up with the idea to expand it into a family and helped create what it is, my point is that he didn't come into this wanting to dissect this story, it was brought to him. He did a phenomenal job in the writing room, creating the story he did (I could go on and on and on, but I shant). When writing, he felt closest to Steven because Shirley is upset with him using their personal fanily stories for fodder for fame. He said he felt he kind of did the same and knew how certain characters felt or acted because he had seen it happen in real life, so he KNOWS and treated these tough subjects with great respect in this retelling.

Thirdly: The literal description of the show says it is a "modern reimagining of the Shirley Jackson novel" so no one was blindsided and could've read the book or not before watching the show. It literally says they reimagined it, not retold. Flanagan used SO many callbacks. He went and read the source material and paid homage, not only to the book, but to the other 2 movies as well!

He did not do the book dirty. He tried to give all Jackson fans across multiple sources something that was fun and new but not destroying the memory of the source material.

I've spent years hating movies and shows that were remakes but then couldn't get simple costuming or scenes correct and I'm tired. Flanagan did an amazing job. He put so much heart and soul into not only Hill House, but everything that he creates, and I just feel like any energy hating on him could be spent better elsewhere.

Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, these are just some of mine. I could wax poetic about Flanagan for hours, but I will stop here. I personally don't understand how anyone could dislike this series, but to each their own.

#the haunting of hill house#opinions#dem rambles#unsure if everything I meant to say will be understood#discourse#just felt the need to weigh in#to explain my reasonings without taking over someone's post#I invite anyone to disagree with me and let me know your thoughts#I won't change my opinion but it would be interesting to discuss different reasons why people think#certain things on one of my very favorite piecea of media#mike flanagan

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need need need need need to watch someone watch the haunting of hill house PLEASE it’s dire.

#i tried to show my grandma but i spent more time explaining what was happening than we spent watching the actual show 😭#she said ‘i don’t like the pathos’#i need to relive the experience of showing my ex bly manor and hearing her cry at the end#mike flanagan is in my brain stem. i’m going to die#.txt#the haunting of hill house#flanaverse

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halt: I can’t tell which I’m more surprised by- the fact that you didn’t realize you have intense trauma, or that you thought you were straight.

Will: Okay now that’s not fair

#rangers apprentice#john flanagan#will treaty#halt o'carrick#ranger's apprentice#books#incorrect quotes#idk i came up with this randomly#i thought about context but I think it’s funnier on its own#will treaty is not straight#actually no one in this god forsaken series is#Horace and Will might be best friends but they so say ‘no homo’#halt and Crowley had a thing at some point I’m so sure of it#NOT STRAIGHT ILL SAY IT AGAIN#i don’t Care if it’s not canon if I say it is then it is#oh wait I forgot about the trauma bit when I was writing the tags#i was too focused on how they’re not straight LMFAO SORRY#will probably was so oblivious to it until someone pointed out a very clear sign of it#he was like ‘oh that explains so much’#CROWLEY CALLING HIS TRAUMA ‘excitement’ IN BOOK 8 IS A THING IM NOT KIDDING#i cannot make that up#i love when Flanagan lists extremely traumatizing events and then says ‘it was an exciting time!!’ like no it was not#like when cass told Duncan what she had gone through in book 7#ok shutting up now

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does Camille Usher strike you guys as a cannibal because to be completely honest I could see her eating a person

#she just#I can’t explain it#this is info I’d like to know#like I think she’d try human meat if someone offered it to her#the fall of the house of usher#camille l’espanaye#mike flanagan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In which I spent forty minutes stuck in the snow in the driveway and am now safely not halfway in the road anymore and, uh. Hey, look, I have suddenly some free time, LET'S DO THE 2-4 CASE TRIAL.

#musings#bandit#i can get back to writing later right now LET'S THE CLASS TRIAL I WANT TO GET TO NAGITO'S THING#I KNOW IT'S COMING#look i'm so excited for past that too because i have so many spoiler tidbit stuff that i just#I WANT THE FULL STORY BUT I DON'T WANT THE FULL SPOILERS SO I GOTTA PLAY THE STORY#and then i think drif is in this as a bonus? i think?#and i look forward to that too!#and like i want to know all the things but i also wanna take my time and enjoy them#and not speed through them you know#(classic case of bandit wants to get into a thing prompted by headcanon#and wanting to meta or write a thing#this happened with: wfrr; hannibal; and ALL of flanagan's stuff i've seen by proxy of this is how i got into hill house#it's a tradition at this point#(of note: wfrr was jess through someone else's headcanon of her#hannibal was bedelia through other people writing her and me just !!!! she seems like my writing type let's do some research#and flanagan was through hill house which was dad basically binging it over and over and me#sitting down through theo's episode and#!!!!! that is her that is the missing character for this roisa fanfic NOW I GUESS I GOTTA SEE THE WHOLE SHOW)#this also explains why my writing dr fanfic without all the canon is...not normal#(roisa not included)#(well with roisa i gave myself spoilers and i'm avoiding most of them with dr that's different i guess)#because i really like being canon-compliant#knowing enough to know how my one little change shifts everything#and what that has to shift in the character who changes#and i don't know enough dr lore to necessarily know what all changes in this fic /yet/#or even to choose what to keep or not from canon#i know what shifted in the singular character i intentionally changed#and he's dead now!#...probably! so!!)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://youtu.be/yvuAWVzP6wI?si=ynDg90DlZCSHSXLt

youtube

the fall of the house of usher interpreted as a horror slasher was really not the route i expected this to go but you have my attention !!!

#kt tangents#the fall of the house of usher#mike flanagan#literally so excited about this I can’t even explain#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I woke pitching forward as the car abruptly slew to a halt. Within moments my parents were outside searching in the weak glow of the car's headlights on that lonely road for the Tasmanian tiger-even then a mythical creature which had just crossed in front of our car. I followed, confused, feeling the wetness of fog beading on my face, seeing only puddles in the dimly lit muddy gravel...

...At some point I came to understand that I wrote from the frontlines of a war about which most have no idea. For a long time I could not understand that it was possible to be both on the side that has the power, that has unleashed the destruction, vast as it is indescribable, and, at the same time, be on the side that loses everything.

To do that you have to return to a child blinking in the rain, staring into the darkness, looking for something that his parents saw only an instant before and which has already vanished for all time, never to return.

That's life."

- Question 7, Richard Flanagan

#nothing I've ever read has been able to explain the Tasmanian experience to be as well as this book#the grief and the guilt#the legacy of poverty and violence#the dual suffering of Robinson's BLack Line and the convict system#the environmental destruction and loss of the thylacine#but also the enduring resilience of the Palawa peoples#anyway this was the best book I've read in about five years#question 7#richard flanagan

0 notes

Text

the midnight mass is less horror and more about christianity at this point 😭

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Overly In-depth Analysis of Spinning Silver Many Years Late

`When I first started writing this in 2022, I had recently finished reading Naomi Novik’s Spinning Silver for the first time. I wanted to remember a particular quote in the book, and stumbled upon some reviews from 2019, when the paperback was released.

The quote I was looking for: You will never be a Staryk Queen until you make a hundred winters in one day, seal the crack in the mountain, and make the white tree bloom.

The reviews:

…read Temeraire and Uprooted at least ten times, but couldn’t reread this. The relationships between the two main men and two main women are abusive. Certainly, there’s trauma involved, but it’s not a woman’s job to heal men’s trauma through sacrificing themselves…

…I adored Uprooted (had some issues, but still loved it completely), however Spinning Silver just felt off – not as magical, terrible “romances”, too many POVs, etc. All in all, it just wasn’t as gripping. I liked Miryem’s character, but the other two protagonists were very bland “strong female characters…”

I hate this. I hate this so much. I hate this enough that I’m going to write an excessively long post defending Spinning Silver for three years. For everyone that doesn’t want to read a masters-student dissertation of an essay or who hasn’t read the book yet and wants to go into this spoiler free, here’s the TL:DR version. There are no romances in this book. The two reviewers above are trying to apply the enemies to lovers tropes they loved so much in Uprooted to a grimm fairy tale about politics, feminism, and Jewish persecution. There are no romances in this book. This is hard to grasp, because two of the main characters are married, and that marriage is a major part of the plot, but no one in those marriages including the men wanted the marriage in the first place. To call it “abusive” is to read modern expectations onto a historical political marriage that, while not inaccurate, fundamentally misunderstands the point and the context in which the story takes place.

Also, I would recommend the audio book, if you have trouble with multiple points of view. They are all in first person, and although it starts out with just two, we add more and more POV until there’s 5 or 6 total. The reader Lisa Flanagan does an excellent job distinguishing POVs which will make this aspect of it easier. Read the book, particularly the audiobook. But if you are reading this book looking for romance, you’re going to be disappointed. It’s still one of the best if not the best re-imagined fairy tale I’ve ever read. Here’s an excessively long post about why.

The Introduction

The very first thing we’re introduced to is Miryem as our narrator explaining that stories aren’t about “how they tell it” but getting out of paying your debts. So how do “they” tell it? The introductory story is about a girl having sex out of wedlock who is left in the lurch because the “lord, prince, rich man’s son” has a duty.

It’s about saving yourself for marriage. Even in how “they” tell it, who the man is doesn’t matter and no one is in love. Your duty to your family comes first.

This story is not about romance. The story this story is subverting is not about romance. Even in how “they” tell it, romance isn’t a good thing.

In actual fairy tales, not Disney princess stories, romance often has nothing to do with it. These are stories for little children to get them to obey their parents. Rumpelstilskin is about ingenuity and perseverance. Even in a story like Cinderella, the romance is entirely incidental - the story is about hard work, strength through adversity, and moral superiority. The marriage itself isn’t romantic in the sense that the two main characters fall in love. These stories are older than the modern concept of love. For authors with a strong sense of familial duty and nationalism, writing about something as subversive as romantic love would go against their goals.

This is the setting that Spinning Silver takes place in. It’s a modern fairy tale set in a regency era. The fairy tale Miryem tells in our introduction paints romance as a bad thing. You marry out of duty.

But Miryem from the start tells us that filial duty isn’t what the stories are really about. They’re really about paying your debts. Within the first 2 minutes of this book, it’s already told us three times that this story isn’t about romance. Once in the setting of a fairy tale about filial duty, once in the denial of how they tell it, and once in the revelation of the real interpretation.

The Power of Threes

The power of repetition and specifically of threes comes up over and over again in the book. In many cultures across the world, three has special significance. From the fairy tale side of it, Rumpelstilskin itself contains layers of threes within threes. Rumpelstilskin makes a bargain for the miller’s daughter on the third night. The queen has three days to guess Rumpelstilskin’s name, and guesses three names each day.

It’s likely that these repetitions of threes in fairy tales come from the Christian backdrop they were written in, which at times focuses on the third path in the middle of two binaries, or the significance of building power, though it’s difficult to make any sweeping, central claims about why three is significant because fairy tales are so widespread across countries, time, and religion. But it’s important that Novik is writing this from a Lithuanian Jewish perspective, so there’s a subtle shift in the interpretation and meaning of the rule of threes. I’m not Jewish, so what specifically this is as grounded in Novik’s ancestry is something I can’t be clear on.

During my research, one explanation that seems to resonate with the symbolism of this book is a Chabad interpretation. From chabad.org: The number three symbolizes a harmony that includes and synthesizes two opposites. The unity symbolized by the number three isn’t accomplished by getting rid of number two, the entity that caused the discord, and reverting to the unity symbolized by number one. Rather, three merges the two to create a new entity, one that harmoniously includes both opposites.

Lithuanian Judaism is majority non-Hasidic, so this is just one tangentially-related explanation of the importance of threes. I’m sure there’s other interpretations I’m missing because I can’t possibly begin to know where to look. But I like this explanation for grounding the story because I think it fits well with the symmetry of our protagonists and their husbands (or lack thereof), and the way the story is building to their creating something new.

So when the very first thing we are shown within the first two minutes of the book is a thrice denial of romance, we need to take Naomi Novik seriously when she says that the book is about getting out of paying your debts. Or, at the very least, this is what Miryem thinks the book is about. The way in which the characters grow and change does reveal some of the original cynicism in this thesis, but ultimately this is a story about what we owe each other, and how that debt comes for us if we don’t pay it. And on top of that, Miryem describes the love interest of the miller’s daughter as “lord, prince, rich man’s son” (3 possibilities). Who this love interest is doesn’t matter in the slightest.

All this to say that within the first two minutes of the book, if you are still reading this expecting a romance, you aren’t listening to the author.

Jewish Heritage

Also within the first few minutes of the book, we learn that Miryem is a Jewish moneylender in a fantasy version of Russian-occupied Lithuania some time in the Middle Ages. I’m not going to get too deep into this. I am, as I said, not Jewish, and these characterisations edge very close, on purpose, to deeply anti-Semitic tropes. But understanding what Novik is saying about her heritage and her family’s persecution is critically important to understanding the book.

Naomi Novik is a second-generation American. She’s Lithuanian Jewish on her father’s side, and Polish Catholic on her mother’s side. In many ways, Spinning Silver has been treated as a spiritual successor to Uprooted. Uprooted is set in a fantasy version of Poland, Spinning Silver is set in a fantasy version of Lithuania. Both stories are about Novik’s heritage, and the stories from her ancestors. Spinning Silver is a lot more obvious about this, but there’s a non-zero amount of Catholicism in the way the Dragon structures his magic, and in the older folk magic that lives in the trees.

Spinning Silver is much more explicit, and Novik has said as much, that Miryem’s family is supposed to reflect her father’s family and his experience as a Lithuanian Jew.

Our book takes place in a fantasy version of Lithuania in 1816. That’s a very specific date I’ve picked out for a book that otherwise appears to be ‘the ambiguous past.’ How did I come to that conclusion?

I did a little bit of research to try and determine when and this is what I came up with: Lithuania didn’t exist until the 13th century. Lithuania didn’t have a tsar on the throne until Russian imperialism in the late 1700s. Restrictions on Jews’ ability to work in craft or trade began around 1100 in Europe, and began to wane around 1850. In Lithuania, this fluctuated depending on the specific time period, so we can a little further narrow the timing down to after the mid 1600s but before the 1850s, probably during early Russian imperialism. Leadership is religious, either Eastern Orthodox or Catholic, who at the time believed that charging interest was sinful, so employed members of other religions, specifically Jews, to do their money lending for them. Because of the association with sinful, dirty work, and previous oppression as a religious minority, this led to a significant rise in anti-Semitism, coming to a head with a series of Jewish pogroms in Russia from (officially) 1821-1906, leading millions to flee and thousands of deaths. So we can narrow our estimation down to about 80 years, between 1820-1900.

Then my historian partner started reading it with me and exclaimed, "is that a reference to the Year Without A Summer" so actually 1816, but you can also see how easy it is to narrow that date down even as an amateur just by examining the exact flavor of anti-Semitism in the text. Which is why, even after I learned about the year Without A Summer, I left my aimless searching in.

Most audience members probably don’t know this much detail about history, but Spinning Silver is very clearly written with an audience understanding of this history in mind. We’re supposed to see the rise in anti-Semitism throughout the book which adds a layer of tension because at any moment, the politics in the wider world and rising anti-Semitism might catch up to our protaginists, and Miryem and her entire family could be killed.

That’s it, book over. Anti-Semitism sweeps through, destroys everything it touches, and none of the clever problem-solving of any of our heroines matters. It’s over.

This dark possibility looms over the story like a storm cloud the entire time. The most explicit reference is when Miryem uses the tunnel her grandfather dug.

“I pulled it up easily, and there was a ladder there waiting for me to climb down. Waiting for many people to climb down, here close to the synagogue, in case one day men came through the wall of the quarter with torches and axes, the way they had in the west where my grandfather’s grandmother had been a girl.”

The fear of persecution isn’t just something of the past. It is something that people in this community are actively thinking about and planning contingencies for.

We’re five pages in and I’ve barely gotten through the first five minutes of the book. I could do this for literally the rest of the book if I wanted to - five minutes later, Miryem as narrator starts talking about a festival at the turn of the seasons between Autumn and Winter, which she calls “their festival” and resents the townspeople for it because they’re spending money they borrowed from Panov Mandelstam on it. Meanwhile, Panov Mandelstam is lighting a candle for the third day of their own festival, when a cold wind sweeps in and blows the candles out. Her father tells them it’s a sign for bed time instead of relighting them, because they’re almost out of oil. Panov Mandelstam is reduced to whittling candles out of wood because, “there isn’t going to be any miracle of light in our house.” I didn’t catch this the first time around, because I’m an ignorant goyim I wasn’t thinking about this book as an explicitly Jewish fairytale. But Novik is obviously making a reference to Channukkah, and the fact that Panov Mandeltam doesn’t relight the candles for Channukkah is powerfully unsettling. And then on the eigth day, Miryem takes up her father’s work and collects the money he’s been neglecting, and there is light in their house for Channukkah after all, but the miracle is hard work, not magic. The entire book is like that, layers upon layers of meaning with every sentence. Subtle clues before the curtain is pulled back. I want to teach a seminar using only this book on the definition of “show, don’t tell.”

Good and Evil

But at some point I’m going to have to move on, and so let’s talk about trauma, poverty, and morals.

Novik introduces the townsfolk as Miryem sees them, but not all the townsfolk. Each person introduced by name winds up coming back later, enacting some kind of harm. But it seems to me that this harm is foreshadowed in each instance.

First, we’re introduced to Oleg. Oleg’s wife is described as being Oleg’s “squirrelly, nervous wife.” This isn’t the only time it occurs to me to wonder if Oleg beats his wife, but I think the description is intentional. Oleg eventually tries to murder Miryem, for explicitly anti-Semetic reasons, but I think this violence is foreshadowed in the way we see him interact, in brief flashes, with his wife and son, and how they’re always described as being a little withdrawn, a little afraid of Oleg, and not very sad that he’s gone, except in the part where this is going to be a financial burden on the family.

Next introduced is Kajus. Kajus who had borrowed two gold pieces to establish himself as a krupnik brewer (the krupnik he brews would lead to Da’s alcoholism). His solution to Miryem banging on their doors is to offer her a drink. Clearly getting people hooked and indebted to him is a tactic he’s used to success more than once.

The last person introduced in this sequence is Lyudmila. Again, we are given a set of three. Lyudmila is different. Lyudmila never borrowed money. She doesn’t have a direct reason for despising the Mandelstams. Or at least, she shouldn’t. And yet, her distain jumps off the page. Lyudmila is the quiet, insidious voice spreading lies and rumors about the Jewish family in town. Her violence is not explicit. But it is the same.

The last person we’re introduced to, given an entire separate section to his own, is Gorek.

Good and Evil part 2 - is Wanda’s Da an evil character?

Gorek, who’s better known for the rest of the book as Wanda’s Da, is also introduced to us first as a borrower trying to get out of paying his debts. Gorek is a violent drunk. This is established repeatedly. Gorek is not a good man.

But is he evil? Certainly he seems to be the antagonist of Wanda’s story, and there’s no love lost when he dies. But I think it’s interesting that even Gorek, in many respects, is sympathetic. He’s not very different from any of the other men in this town. Oleg is violent. Kajus profits off the many people in the town that drink their troubles away. Gorek is not uniquely awful even if he is particularly awful. And even for Gorek, the text takes pains to remind us that he buried his wife and five children. His life is hard. Their plot of land is sat next to a tree where nothing will grow. How much rye did they waste before they learned that lesson? And when Mama was alive, they had enough to eat in the winter, but only because she was very, very careful to divide everything up. On his own, Gorek couldn’t make that math add up, even before he started drinking his troubles away. Gorek is facing a life where unless something drastic changes, he and his children will slowly starve to death, and there’s nothing he can do about it.

So he sells his daughter for one jug of krupnik a week. Gorek has made his bed; he doesn’t want to keep living. He’s drinking himself into the grave he dug for his wife. But in the meantime he does still need to take care of his children.

I don’t say this to forgive his actions; I do think Gorek’s actions are unforgivable. Some people cannot be redeemed, they can only be defeated, and Gorek is one of those people. But at the end of the book, Wanda and Sergei and Stepon still bury him when they go back to Pavys, next to the rest of their deceased family.

Gorek is a product of his environment, and that environment is cruel and cold. The people it produces are by and large cruel and cold. No one in the town bothers to bury Gorek. No one stops him from hitting his wife and children. There’s nothing at all strange, according to the rest of the town, about his selling his daughter for drink.

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Gorek is not evil, but I also think that this book is taking pains to present with sympathy the kind of environment which creates people like Gorek. Like our Staryk king, who was entirely prepared to force himself onto Miryem even though neither one of them wanted it. Like Mirnatius, who did not himself commit any acts of violence, but who was perfectly willing to benefit from the violence being committed with his face. The world is cold and cruel, and it is very, very easy to become cold and cruel from it.

The Power of Threes revisited: Miryem’s magic

Even Miryem says that she’s had to be cold and cruel to be their family’s moneylender. We don’t see very much of this. But she does after all agree to have someone work in her house for essentially no pay. We don’t necessarily realize it, because it comes at our own turning point, but Miryem has to learn empathy just as much as her Staryk king does. When she agrees to allow Flek and Tsop and Shofer to help her with her trials.

I read Novik’s new anthology Buried Deep and Other Stories and in that collection she says it’s a line from the Staryk king about Miryem’s magic that made her want to expand what was originally a short story into a full book. “A power claimed and challenged and thrice carried out is true; the proving makes it so.”

Fairy tales are about hard work. This line from the Staryk king isn’t just a way of constructing magic, it’s just literally true. If I get a job as an accountant, despite not knowing anything about accounting, and I don’t fail, then by the end I will be an accountant. I love this, that the magic in Spinning Silver is just hard work.

Miryem’s magic is another rule of threes. The Staryk king challenges her to turn silver into gold three times, to make the magic true, and she does it – with mundane means, through ordinary hard work, but it’s done. She barters freedom for a day by turning three storehouses to gold, and she does that too – with wit and hard work, but it’s done. The Staryk king challenges her that she’ll never be a Staryk queen, unless she can do three feats of high magic, and she does each one. Or rather, each one gets done, and Miryem has a hand in it. But the first feat of high magic requires the assistance of one other person. The second – the assistance of three. Much like each trial before it grew in magnitude – first 6 coins, then 60, then 600 – so too do all three stories grow in magnitude. It would stand to reason then that the third test of magic would require at least three upon three people. But Miryem is not the only protagonist in this story.

Circling back to Romance: Arranged Marriage is Bad That’s Obviously The Point

In addition to the rule of threes woven repeatedly in Miryem’s story, the entire story itself is a Triptych. One story is the story of the girl who could turn silver into gold. One story is the story of the children who find themselves lost in the woods and stumble onto a witch’s house full of rich food. One story is the story of the duke’s misfit daughter who marries a prince. They are all of them different fairy tales. And at the end of the story, they all come crashing into each other. The white tree belongs to Wanda’s story, bought with six lives.

Three sets of three people in each story

There are many, many examples of threes woven throughout this story, but it was only three years into writing this essay that I realized that the marriages themselves are a set of three as well. After all, only Irina and Miryem get married, right?

But Wanda is offered a marriage proposal. In a story with less magic, Wanda would have married Lukas, and been yet another generation of poor, miserable women that died in childbirth. But Wanda says no, a thing entirely unheard of in this era. Women didn’t say no to marriages arranged by their fathers.

And at the end of the story, Wanda is still unwed, with absolutely no indication that this will ever change. Wanda’s agency, this rejection of marriage, is treated with the same weight as the marriages themselves. Saying no is just as valuable as Irina’s political marriage, or courting for a year and a day and marrying for love, as Miryem eventually does.

And Miryem does marry for love. She originally has no choice in the matter, but that contract is rendered void when the Staryk king is forced to let her go. We don’t see the year’s worth of courting because it’s not relevant to the story because this is not a romance but I really don’t want to lose this point because I think Wanda’s story sometimes gets forgotten precisely because it doesn’t have a marriage. But Novik is explicit about this through Wanda’s story. Irina had no choice, not really. So it never occurred to her to say yes or no. She kills the man who sought to marry her – Chernobog wanted to marry Irina, not Mirnatius. Irina murders her would-be husband, Miryem divorces hers, and Wanda says no. Yes, the arranged marriages in this book are abusive – Novik knows that and tears them down one by one and rebuilds them into something with far more agency, that our women protagonists chose.

The Story

So we’ve come all this way and learned that Spinning Silver is not a romance, not really. The married couples in the story do come to love each other, after a fashion. But that love blooming was not the point. The point was…

Well it was about getting out of paying your debts, wasn’t it? Novik told us very explicitly that it was about getting out of paying your debts right on the first page. It’s not how they told it. But she knew.

Miryem spends the entire book making her fortune from nothing. Wanda takes over the work from her. Stepon takes over after Wanda. The debt that the town owed to Josef was a major thread over and over again throughout the whole story. Oleg tries to kill Miryem over it. The Staryk king seeks Miryem’s hand because of it. Raquel had been sick because their dowry had been spent. Wanda comes to their house to pay off the debt. Nearly everything in the book can be traced back to the debt against Josef Mandelstam.

And then, in Chapter 25, Josef sends Wanda with many letters to the people of the town forgiving all the remaining debt that was owed. The people of Pavys get out of paying their debt.

But… how do they get out of it? Not through any trickery of their own, not really. There is a stated implication that fear was a big part of it. Sending Wanda with letters of forgiveness would mean that they would not be harried or harmed while they were wrapping up affairs in the town. But Josef also doesn’t need the money. They have a home of their own, many hands to make light the work, blessings from the Sunlit Tsar to establish their place in the world, and blessings from the Staryk king that will ensure their safety even through a hard winter. They want for nothing, so they do not seek to reclaim what is theirs.

And in a way they got all those blessings through paying their debts, but in a way they did not. The Staryk way of paying their debts teaches us something very important about what a debt really is. The Staryks don’t keep debts. They make fair trade. And if they can’t make fair trade, there is no deal. Or at least, they say they make fair trade. They didn’t trade for the gold they steal from the Sunlit world, though I suspect they would argue that the pain that is caused to the people of that world is trade for their putting a monster on the throne. And Miryem rightly points out that they had been raiding for gold and raping the people of Lithvas long before Chernobog sat on the throne. They make fair trade. But only with those they view as their equals.

But the Sunlit world is even worse. The Tsar doesn’t make fair trade. He spends magic like water and steals the lives of people that didn’t bargain with him to pay for it. In the Sunlit world, people take as much as they can with as little return as they can get away with. Not everyone, of course. But it is of particular note here that in this story, Jews are vilified particularly because they ask for fair trade in return. And the people they loan money to don’t want to give it to them.

But fair trade can only go so far. The Staryk king is trying to make a road back to his kingdom, and he can’t, because there is nothing of winter that they can find in the warm summer day. And he cannot take Stepon’s white tree seed, because it was bought with six lives, and given to Stepon alone, and there is nothing that the Staryk king can barter with that would measure against a mother’s love. But Stepon wants to see the white tree grown, so they find a way to plant it. Irina digs hard soil in apology, and the Mandelstams sing a hymn to encourage growth, and although none of this was done for the Staryk king, he still uses the work to create his road.

Sometimes, fair trade isn’t enough, and one must trust that it is to the benefit of all to aid each other.

The truest way of getting out of paying your debts… is to abolish the concept of debt.

That’s right, motherfuckers, eat your kings and burn the banks to the ground, love is the anti-capitalist manifesto we made along the way!

This section was going to be a little bit of a joke, but the more I think about it, the more it really isn’t. Miryem’s magic makes wealth meaningless in its magnitude. Wanda’s magic is having food and shelter to spare. And Irina’s magic is having just leadership that rules for the people, not for power. Novik’s fairytale ending is collectivism. She tells us three times, through three stories of hardship. And it isn’t even about becoming a princess, because Wanda marries no one, and lives in a magical house that seems to always have everything they need. So long as they do what they can to take care of it.

The real magic is community. Doing for yourself what you can, and reaching your hand to another when you can spare, so that they might do the same. And so long as we all do that together, the darkness cannot come in to feast.

#disk horse#media analysis#naomi novik#spinning silver#literary analysis#okay this one's long even for me#also it took three years to write#five thousand words#nine sources#and two pages of notes

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

About the Mike Flanagan discourse:

I've personally seen people complaining about Flanagan at least since the trailer for his adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher, and before that, he's kinda infamous for his adaptations of Hill House and Turn of the Screw for his tendency to take these stories, scoop all it makes them them, keep only the names and some references and do whatever he wants.

His adaptation of The Haunting of Hill House is kinda egregious due to him taking a story about the typical family structure is a source of horror to those who can't fit into it (like Theo for being gay and Eleanor for being a childless spinster) and turned into a show about an evil house breaking apart this nuclear family, only for them to overcome their inner demons and grief via the power of love, and that's without touching how he sisterzoned Eleanor and Theo, who in the original book got attached to each other really fast, with Eleanor even dreaming of U-Hauling with Theo.

I think the reason you're seeing more and more hate for Flanagan is because people are getting more and more tired of his shit, though I admit it can be kinda extreme. However, there are still lots of people excited to see his takes on Carrie and The Exorcist on his main tag.

Hope this explains the situation.

well, that's one opinion and I appreciate it! however I never understood people complaining about Theo and Eleanor being sisters in the show, given that Theo is still a lesbian and gets a girlfriend, but you do you. I guess I've seen plenty of adaptations of my favorite books that didn't follow the original closely, so I've learned to keep these two things separately. in Flanagan's case, those aren't even adaptations really, they just take some inspiration from the source material and put their own spin on it, and I don't see what's so controversial about it. why can't he do with them whatever he wants? is there a law against that? this discourse reminds me of people complaining about modern adaptations of the things they loved as kids, claiming that they "ruined their childhood" (she-ra is one example I can think of right now). but the source material is still there! it's not ruined! Flanagan didn't burn those books, you can still go and read them. "tired of his shit" sounds so funny to me, I'm so sorry, but it feels like he's personally making you sit through all his shows. long story short, adaptations are allowed to be different, and yes even wildly different. if Mike's work is not your thing, maybe try The Haunting (1999) where Eleanor banishes Hugh Crain to hell and then ascends to heaven, that for sure sounds less sanitizing, right?

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I love about the way Flanagan writes villains is how he just lets them be evil. So many authors and directors try so hard to have “realistic” villains; poor, broken people who have been pushed too far. Those villains can be great and all, but holy shit, if an antagonist’s agonizing backstory only exists for the sake of making a bad guy’s character ‘believable’, it often makes the story clunky.

Flanagan never tries to explain his villains or justify their actions. There’s no “you know, maybe we’re not so different” moments between hero and villain. Morgarath wanted to take over Araluen because he was power hungry. Keren wanted to seize Mackindaw because he had an inflated ego. Jory Ruhl kidnapped children because he wanted money. These are some of the most shallow motives for villains, and I love it. Honestly, I think these are actually more realistic than the ‘morally-grey misguided soul’ type of villain. Do you have any idea the fucking atrocities that are committed for money or power or even just so some guy can jack himself off? A fucking lot.

And I absolutely love the effect it has on the overall story. There’s no wasted time on the main characters learning to understand the villain, no ethical dilemma someone has a breakdown over, no cheesy sob stories. All of those tropes are great in their own stories, of course, but I’m sick and tired of stories that clearly just want to be action and/or adventure getting a shallow moral lesson shoehorned into it because the author got marked down in their high school English class for not being ‘realistic enough’.

Flanagan knows what he wants his stories to be about, and he lets those stories be what they want to be. The rare moments where he gives his villains some deeper motives never convolute the character, but enhance them. Love it.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I just watched gquuuuuux again and something caught my eye on the rewatch that has me questioning Machu's past

Her whole shtick is that she's listless in her colony and bored with life, has no control, etc., and so jumps on the chance to kill cops and fight in mobile suits

EXCEPT! When she's debating with herself about whether or not to return to the Pomeranians base to do an official clan battle, she has a piece of dialogue along the lines of "If I don't come back, she could report me to the police" (she's talking about Annqi here)

and when she thinks that, there's a really quick flash of what looks like a criminal record sheet. It went by so fast that I couldn't confirm anything, but it had the censor bar over her eyes and everything

Calling it here: Machu is either a criminal/juvenile delinquent/whathaveyou,

OR, the page I saw was actually a record of her time at the Flanagan Institute. (this could explain why she can activate the omega psycommu)

Point being, I think she's got more going on than simple upper-middle class boredom

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

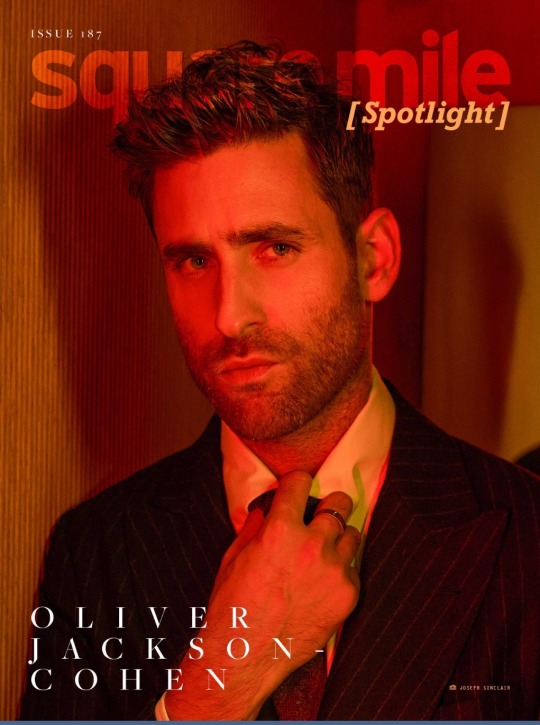

Few actors have endured as fraught a journey as Oliver Jackson-Cohen. Few actors are more in demand than the star of The Haunting of Hill House and Jackdaw

by Maeve Ryan

OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN HAS been doing this a while. He decided to act at the age of six. Joined a theatre troupe and began to climb. He continued until university but didn’t get into any drama schools. Throughout our conversation, he tells me there were no signs pointing him in this direction, no surefire chance at success. But he’s found it, and then some.

He rose to prominence with his highly acclaimed portrayal of Luke Crain in Mike Flanagan’s The Haunting of Hill House.

A character that battled a heroin addiction to cope with past traumas, though addiction was the least interesting thing about him. The show featured stars of the past, and launched new ones into the present, Oliver Jackson-Cohen being one of them. The role of Luke changed the course of his life – for more reasons than one.

It was the first time in his life he no longer had to hide, he tells me. “I could be as fragile as I felt.” He took his newfound Netflix fame and began to carve a path that finally aligned with who he was, not who the world wanted him to be.

Now, he takes centre stage in Jamie Dobb’s new film Jackdaw. When he read the script, he thought he was the last man for the job. When Dobb explained the hyper masculine lead needed someone to bring softness behind it, he signed on.

Jackson-Cohen’s career, and presence, proves that the strength of a man lies in his ability to go beyond society’s standards. He breaks the stereotypes like bread over a long conversation in Soho. We discuss his entrance into the industry, facing traumas, and finding a safe place to land.

sm: What was the first movie you ever saw that made you want to act?

o-jc: Home Alone. I remember seeing that film and saying, oh whoa, so a kid can do this? I remember telling my dad, ‘I think I want to do that.’ I was six or seven.

But it gets dark. So, my mum and dad’s house had a bay window that was on the street. And when I came home from school for a week, I just sat in the window thinking, any minute now, someone from Home Alone is going to walk past, and go, there’s a kid! Let’s get him! I was willingly wanting to get kidnapped. Which is so fucked. My dad came home and was like, ‘What are you doing?’ And then he was like, ‘Yeah, that’s not how that works.’

We found a theatre program – I started going there when I was eight. I was never the golden kid. In the drama clubs, I was always like the snake in the background. Or just the scenery. We used to put on terrible plays. I was such an insular kid. I found a safe place to feel where it’s real, but it’s not. So you can experience it all. I did that for three years, and then I was kicked out.

sm: What! Why?

oj-c: I had an attitude or something like that. I got suspended so many times. I genuinely was not looking for trouble. I was always the one to get caught. Like, I was the kid who someone handed the knife to, and I’d be standing above the dead body, and then the next thing I knew it was 20 years in prison. It was always stuff like that. But it was time to move on anyway.

I found this drama school at Riverside Studios. It was a small group, maybe eight or nine people. It was so interesting, because I’m going to do a gross name drop, but in the group was Carey Mulligan and Imogen Poots. It was incredible.

sm: Those were the kids that were just there? Did you have to audition?

oj-c: No, but I did a trial. It was a lot of devised stuff, like improv. A guy named Andrew Bradford ran it. He really supported kids. It was all day Saturday. We were all teenagers. It felt like another life. It grew and grew and by the time I left I was 17 or 18. It wasn’t one of those places that you were beaten down. No fake bullshit. It was a safe place to try stuff. We’d put on plays and we all got agents from that as kids.

sm: Is that the moment you look back on and think of as the beginning?

oj-c: I think so. But it was such a long period of time. Career wise, it was quite stagnant. I did one job when I was 15 that was some late night soap. Then I didn’t do anything until I was 18. I wasn’t like this is real until later. It started to snowball when I finished school. I went to get a French lit degree, hated it, dropped out, and applied to drama school. I didn’t get in anywhere.

In the meantime, there was a job at the BBC for a silly period drama. I did that, took the money, and went to do a foundation in New York at Strasberg.

sm: Tell me about the audition for drama school. You didn’t get in anywhere?

oj-c: Yes. I’m telling you there were no signs that pointed to me saying, yeah, you’re quite good at this. It felt like everyone was saying, ‘don’t do it.’ Which is a really interesting place to start from. If no one around me believes in me, how do I? And I just keep going? It was a mix of delusion and stupidity.

sm: Did you think about doing something else?

oj-c: When I was still in high school, I worked as a runner on productions, mainly at the BBC. I was revolving through that so when I finished school, that was kinda my job.. I got to see the inner workings of how sets worked, rehearsal periods. I got to see the writers and the actors, how they would construct a joke, and adjust things.

When I was 17, I started doing the European Music Awards. I would go and work in the costume department, I didn’t fucking know anything about how to sew on a bun but it was amazing. I got such a solid understanding of how a production office works, how a schedule works.

Tragically, you see a lot of how an actor is a small cog in this machine. Everyone is working so diligently. This whole idea of superiority that can go on, it was important for me to witness early on. Because when you go onto set and someone says five minutes, it actually means five minutes. But it was also hard because I was watching people do what I love. I didn’t get into school, so I said fuck it, I’m gonna do a foundation for a year and reapply to drama school from New York.

sm: Why choose the Strasberg program?

oj-c: Someone told me about it. I thought I needed to go do something that gives me a playground, a space in the meantime. But when I got there, I was with this small agency, and they started sending me out on auditions. The first or second one I went on, they flew me to LA to do a screen test and I got it. This was six weeks into the program. I was like: what do I do?

sm: What did you decide?

oj-c: There were three or four movies I got, but then the financial crash happened and it all fell apart. So I went back to New York to continue with the program. But meanwhile, I had been signed to WME and my agents were like, let’s go down the studio route because that’s going to be fun. I got an audition for this Drew Barrymore movie, got that, and then I dropped out. Then got another job that moved me to LA. I was there for a year shooting and doing the prep for that.

The whole idea was that I’d do that and reapply to drama school. Then I kept on booking. It’s only in the past couple years I was like, thank fuck I didn’t stop. There were moments that I thought I needed to stop and do three years of training.

sm: Did you feel like you were missing something that other people had?

oj-c: I felt like I was back-footed. Like I had no idea what I was doing, then I realised no one does. There is no arrival point where you’re like, ‘I know how to act!’ A lot of it was becoming comfortable with learning and making mistakes. Some will hurt and some don’t matter.

sm: So you start booking jobs, and then it just keeps going? No break?

oj-c: There’s obviously periods where you’re out of work. Or you really want a job and you do 50 auditions for it and you don’t get it. A lot of that went on. But I was 22. I ended up staying in New York until I was 28. I felt like a deer in the headlights. I was just so grateful that I was working and that people wanted to hire me that I never stopped to ask if it was actually fulfilling.

I listened to a lot of people early on. I needed guidance. I needed someone to say, do this job, this will lead to this, or it’s important you work with this person. Then I woke up one day and was like, is there anything here that I’m actually proud of?

That comes with experience and maybe a little bit of delusional confidence where you go, I think I want to try and do something here that is more aligned with me. It was a weird time to be in LA. I’m six foot three. I look a certain way. People wanted the product. I thought that was how I’d get there. I’ll pretend to be confident, I’ll be a version of what these people want. Keep my mouth shut and pretend. I reached a point where I was like, I cannot keep going this way.

sm: Did you feel that you’d abandoned yourself? Or was it a slow realisation?

oj-c: It became harder and harder to pretend to be this chill guy. I’m not chill. But when you’re handed something, you go, this is fun. Then the more you read and become accustomed to the environment you’re in, you start to feel entitled to have an opinion. To feel entitled enough to say: I actually don’t like this, I actually find this quite soul destroying. Having to make myself small, or block myself off and not be as vulnerable as I feel. To not show that.

It was an interesting time – in the late 2000s, men were men and what I was being asked to do was be an idea of what a tall, white, masculine man was that sort of never really sat. I actually feel really fragile. So I took a break for six months. I was like, I’m just going to say no now and try to re-shape the direction of what I want to do. Then The Haunting of Hill House came along.

sm: How did that audition happen?

oj-c: I’d done a film with the producer before. They sent me a conversation that happens in the show between Luke and his twin sister, it was him asking her to get him drugs. They asked me to read that and literally the following day, they called me and were like yep, you.

means something to people. It was an amazing thing to be a part of.

sm: Did you immediately recognise that Luke was the kind of character you were looking to play on the page?

oj-c: Sort of. If I’m honest, I did quite a lot with the role. Mike was very open to collaborating. I put a lot of stuff in there that wasn’t necessarily there originally.

All of the siblings were there but they were sort of blank canvases for anyone to put whatever they needed to put in it. We all came in and made bigger choices to create this family dynamic. They brought on this incredible writer, Scott Kosar, who wrote The Machinist, to tackle the Luke character because he was in recovery at the time.

sm: The writer was in recovery?

oj-c: Yes. He tackled all those monologues about staying clean and everything. That was him. You know, you’re talking about a family that lived in a haunted house, that’s sort of a silly premise but all the substitutions that everyone did, it was all about trauma. Living and being followed by things unless you face them.

sm: What did you bring to the Luke character that wouldn’t have been there if somebody else played it?

oj-c: Someone else would have brought something amazing to it. But Mike Flanagan had so many tapes come through of people playing the addiction, and you can’t play the addiction. When I first looked at Luke I was like, okay, he’s a heroin addict, but then I was like, actually, to put a label on that, to label him, does such a disservice.

So it became about what he was running from, and what was terrorising him. For me, it became about childhood sexual abuse. How do you escape this thing you don’t want to feel? And if you can’t keep it at bay, it will take over. It became about that struggle, not ‘I need my fix.’ It became about this terrorising thing that’s always present, which translates into the show. We all have things that follow us. It became about trying to humanise it and make it real by using that as a way in.

sm: You’ve been open on social media about the sexual abuse you faced as a child. How did you navigate acting something so close to home?

oj-c: I’m of the school of thought: use whatever is real for you. That’s why I do the job. A lot of us use our own personal experience, but we bring it to a safe space where it’s okay for us to experience it. In a way it calls for that, and it felt important to do for the show.

I come back to this idea of needing to stop and reassess what I wanted to do, where I wanted to go, and what I wanted to say in the work that I do. I felt like I couldn’t keep hiding. We’re all complicated, we’ve all had complicated upbringings. That’s just part of life. It’s unfortunate, but it’s sort of always going to be a mess. I needed to put everything that I felt into something. I do that all the time.

We use the parts of yourselves. Including the darker parts, and some of the stuff we don’t want to look at. I’ve never been one of those people to go half on something. You either do it or you don’t. There’s no middle ground. I’m not going to half step in, or pretend.

sm: Did you have any practices while filming to help you not carry the hurt from that world into your own?

oj-c: What was interesting was that all of that sadness was in there anyway. I wasn’t generating any of it, I was just opening it up. I didn’t whip myself up into a frenzy. It just felt like I didn’t have to hide, or pretend it wasn’t there.

sm: Would you say acting has been healing for you?

oj-c: I don’t think the word healing is correct. But it’s been incredibly helpful in helping me understand myself better. It’s probably not the healthiest but I’ve said this before, I feel like I need the job to lay out all my neuroses and vulnerability. I keep myself so closed off in real life. It’s an outlet that feels necessary. That’s why I go off to work every couple days.

sm: You are cast in a lot of thrillers and horrors. Why do you think you mesh well with that genre as an actor?

oj-c: You know, after I did Haunting of Hill House, it was sort of this big thing where the amount of horror scripts that came through was crazy. The amount of, ‘do you want to play a drug addict?’ It’s incredible how desperate people are to put us into boxes.

After Hill House, I did The Invisible Man. That was a horror but the messaging - we’re talking about gaslighting, we’re talking about toxic relationships to an extreme. It was so much more than a scary film. It felt like it had something to say. That’s the thing about horror. When it’s done well, it’s incredibly impactful.

sm: After Hill House, did you feel you had agency when choosing your roles?

oj-c: To a certain extent. But no matter where you’re at: the job you want, they don’t want you. You can be Julianne Moore, but they’d rather have someone else. It’s constant. But it did change quite a lot. In terms of becoming Netflix famous, which is the strangest, most intense thing ever because you’re the most famous person on the planet and then something else comes out. I felt like I was in a fortunate space where I could choose more, but there were films that I really wanted that I didn’t get.

sm: I heard that when you first read the Jackdaw script, you didn’t think you were right for the role?

oj-c: Yes. I called the director Jamie Childs and told him he was nuts. Because again, here’s this hyper masculine man that felt quite robotic on the page. I met Jamie on the set of Wilderness. He was telling me, ‘I’ve written this movie. I’d love to get your feedback on it.’ So I read it. It was still an early draft. Then he said, ‘Do you want to do it?’ I genuinely thought I wasn’t the right fit. I thought it was just out of convenience that he wanted me.

He said to me, ‘It needs someone to come in and make it human. To give it vulnerability.’ He said the film is about how this man readjusts his life following the death of his mum, and I was like, sold! You need some tears? I’ll bring you tears! I’m never leaving my sad boy era. It happened so quickly. We wrapped Wilderness, and then started filming three and a half weeks later. We were up north in January.

sm: You go swimming in the North Sea quite a bit in the film…

oj-c: Oh yeah. It got to like minus nine. It ended with me getting hypothermia. I think I’m a bit too delicate, that’s why. I had this amazing stunt guy called Jamie Dobbs who’s this gold motor-cross champion, and we had to shoot all this stuff of us in the night. They’d get me on a rig, and then they’d get Jamie and it got to minus 12. He got frostbite on his face. It was unbelievable. It was all night shoots. I am so surprised we all made it out alive.

sm: Had you ever cold plunged before?

oj-c: Not at all. I’m one of those people in August that’s like, I don’t know if I want to go in the sea, it looks a bit cold. We did three days on the water. Some of it was in a kayak. The underwater stuff, that’s where it got brutal. We were all eating every 25 minutes because we were so cold. There was a boat just for food. I couldn’t name one thing we ate. It was just fuel. We were going to work at 5pm, and then wrapping in the morning.

sm: Do you often try new things on film sets that you’d never do otherwise?

oj-c: Yes, all the time! That’s part of the allure of it. You get to learn all these weird things that you’d never do. You get to experience these amazing things. I’ve been doing this for so long, because I’m 150 years old, and someone will bring something up and I’ll be like, oh I’ve done that! But then I’m like wait no I didn’t, the character did.

sm: Was there anything else you learned on the set of Jackdaw? Motorcross?

oj-c: Yes! I fucking loved it. If I’m honest, a lot of it is me jumping on and starting up and then getting out of frame. Insurance-wise, I couldn’t do any of the jumps or anything. But it is so great. There is nothing quite like it.

sm: Do you ever think you’ll get into the writing side of film?

oj-c: I have. I just don’t know what I have to say yet. Everyone reaches a point where they think, I don’t want to forever be a product. It would be nice to be part of the creative. I have a lot of opinions.

You go into a job with the best intentions. This is what they’ve told us, this is what’s been sold and then you’ll see the final product and be like: that’s not at all what I thought it would be. The more you do it, the more you feel like you know what you actually like and what you want to be part of. I’ll get to it at some point.

Jackdaw is in cinemas now.

#oliver jackson-cohen#oliver jackson cohen#jackdaw#jackdaw film#jamie childs#2024#interview#cw: csa#mike flanagan#haunting of hill house#luke crain#jack dawson#i have that home alone anecdote memorised by now 😭#he writes!

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking and explaining my rankings of Mike Flanagan’s shows and how they make me feel in honor of spooky season and just finishing Usher!! Why not!! Everyone else is doing it!! I’m also going to give it a gay score based on how gay they are (which also includes how big of a role gay characters played).

Disclaimer: Every one of these shows is well-made in one way or another and deserves to be watched based on whether someone else finds the premise interesting and not whether I liked the show. Too often I see “that show was bad to me therefore you shouldn’t watch it” and I disagree with that line of thinking.

1. The Haunting of Bly Manor-I can already hear people screaming “Hill House is better!” In some ways, yes! In some very important ways, however, I disagree. The biggest being Bly Manor emotionally resonated with me a lot more. The themes, the found family (as someone who is an only child), and of course, the lesbianism. Dani’s story of compulsory heterosexuality may be one of if not the best in media and her love story with Jamie ended up being one of the best media has to offer, too. And really using a horror story and turning it into a love story is kind of brilliant (and annoying for the people who were just there for the jumpscares I guess). Don’t get me wrong the show has flaws (why the FUCK do Peter and Rebecca have so much screentime? was that eight episode really the best placement?) but the stuff that lands, really really lands. I’m still thinking about Dani and Jamie 3 years later. Hannah’s episode was very well done. The kid actors little Amelie and Ben were phenomenal. Upon rewatch you notice most decisions and dialogue in the show were made with some purpose and it usually relates to something thematic. Some people may say it doesn’t really have one defining central thesis therefore making it messy, but to me the fact it has many themes actually makes it more fun to think about. Gay score: 100000/10

2. The Haunting of Hill House-A horror classic that got me into Flanagan! This is Flanagan’s best series as far as making you pee your pants. That hat man is just scary! The character work is nice. Those first 6 episodes are incredible. Perfect. The thing that brings it under Bly Manor for me is honestly the ending. It left something to be desired for me. I can’t pinpoint exactly what it is, but it just did not conclude in such an emotionally resonant way as Bly Manor to me. Shout out to the Newton Bros because the music on this damn show (and Bly too but that’s basically Hill House music continued) is so so good. Also the character work is masterful because Shirley Crain is kind of a bitch but you do come to love her. In fact, there wasn’t a Crain I didn’t feel for. They’re deeply fucked up, sympathetic people. It’s a great show with some great thematic work but it just doesn’t speak to me quite as much as Bly, that’s it. I know that’s unpopular but it is what it is. A great good show nonetheless. Gay score: 8/10

3. The Fall of the House of Usher-This show is wild and honestly I couldn’t decide between ranking this one or Midnight Club third. I went with this one because the acting and technical stuff was so phenomenal. I’m not really into gore horror so this wasn’t like my thing on the surface but I do appreciate what a homage to Poe it is in the very limited knowledge of Poe’s work that I have. It was fun to see all the cast from previous shows back again especially T’nia. One of the downsides to this show is it doesn’t really make you feel a lot and so compared to the Haunting shows for me that makes it inferior for sure. But it’s a fun watch and honestly I need to rewatch the final episode because I had a hard time paying attention for that one. Gay score: really fucking queer/10

4. The Midnight Club-Ah Flanagan’s little dud. This one is really not very loved compared to the others, seems to be just about nobody’s favorite, however personally I liked it. I think people are a little unfair to it and while it may not be Flanagan’s best, I don’t think it’s awful. It doesn’t really tackle anything new when it comes to themes. There’s some death, grief, stages of acceptance, and cult stuff. I think the way it has these kids telling stories to deal with their reality was really brilliant in a way. There was one episode (six I think) that dealt with depression and suicide that made me sob and I thought was super well done. That one stuck with me.I think it would have benefited from a more likeable main character and also from the second season that was planned! Gay score: 6/10

5. Midnight Mass-To be honest, I probably could have gone without watching this show. It just didn’t really resonate with me and didn’t really entertain me save like the very last two episodes. It’s technically well-made and I appreciate what Flanagan was trying to do and convey with the danger of cults and religion. It was obviously a very personal project and was him working through his own experiences but it wasn’t for me. It had a few too many monologues and I don’t think monologues make an interesting character piece. However, it’s a critically acclaimed work so I recommend anyone who wants to check out Flanagan’s work still check it out! Especially if you like weird vampire stuff I guess. Also the acting especially from the priest was phenomenal. So there’s definitely pros to this show, but it didn’t add anything to my life for me! Gay score: 3/10 :/

Also, shout out to Mike because every single one of these shows is queer to one degree or another. He loves the gays! Ally! Bisexual wife probably helps too!

#the haunting of bly manor#the haunting of hill house#mike flanagan#the midnight club#midnight mass#the fall of the house of usher#bly manor#hill house#thobm#jamie and dani

155 notes

·

View notes