#(the following is translated and paraphrased and not as poetic as it was in the movie.)

Text

I've spent an inordinate amount of time parsing the few examples we have of Old High Gallifreyan text, and here at last is the result of my labors!

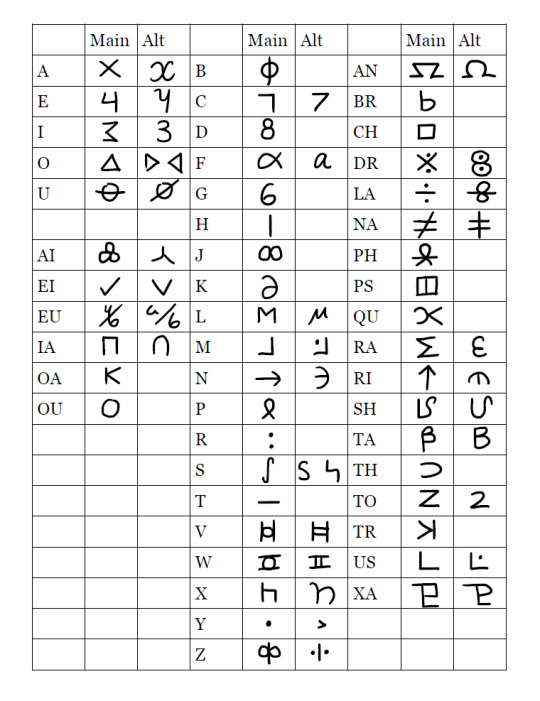

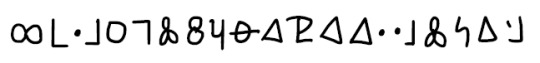

The Old Gallifreyan alphabet:

The alternate forms of letters may be used interchangeably with their main forms; the differences are purely cosmetic, much like the difference between cursive and print-style writing.

Now for my analysis of the existing texts. It's rather long, so I've put it below the break!

EXAMPLES OF OLD HIGH GALLIFREYAN TEXT

ITEM ONE

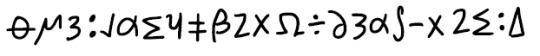

Supposedly from “The Five Doctors,” though I can’t spot this writing anywhere. Translation given in episode.

ORA PSYERPA

O – honorific indicating uniqueness, may be rendered with the definite article “the”

R – combined with the definite honorific, a common abbreviation of Rassilon’s name

A – an alternate version of the possessive “ya,” used only when the possessive noun is already abbreviated

Psyerpa – a general term for harps and other large stringed instruments

Thus, the full text reads:

O-Rassilon-ya psyerpa

The Rassilon’s harp

ITEM TWO

From “The Colony in Space,” across the bottom of the Doctor’s mugshot. No translation given.

QU ETHOA TRIOUAX BRIA

Qu – This is not a complete word, merely a letter used in this case for alphanumerical file designation: note that it stands alone, separate from the main text.

Ethoa – exile

Triouax – an infinitive verb, “to persist” or “to remain in effect”

Bria – a conditional modifier used exclusively in bureaucratic contexts, implying the need for occasional update of information or policy.

This text is a record of the Doctor’s sentence, and may be rendered something like this: Exile: to remain in effect barring further review.

ITEM THREE

From “The Time of Angels.” Translation given.

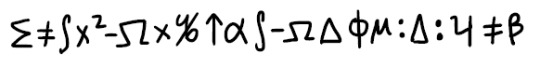

JUSYMOU CAIDEU OXA OOYY MAISOM

Jusymou – An archaic greeting, roughly equivalent to “well met” or “hail.”

Caideu – self, soul, or “hearts” in a poetic sense

Oxa – prepositional suffix, “part of”

OOYY – a conceptual abbreviation that combines the two meanings of the solitary letter O (definite article + symbol of individuality) and the mathematical use of the letter Y (usually indicating a dimensional shift). Literally, this means something like the individual, shifted two dimensions. In practice, it refers to a Time Lord’s fifth dimensional aspect.

Maisom – name, designation, identification

Thus, a literal translation would read something like this: Greetings, soul-linked fifth-dimensional name!

Or as the Doctor paraphrases it: Hello, Sweetie.

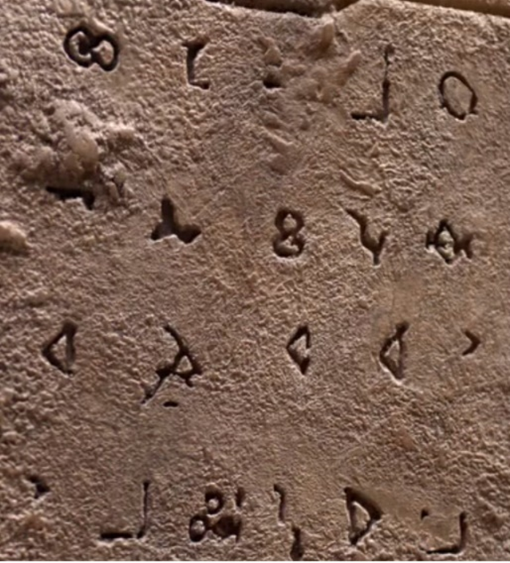

ITEM FOUR

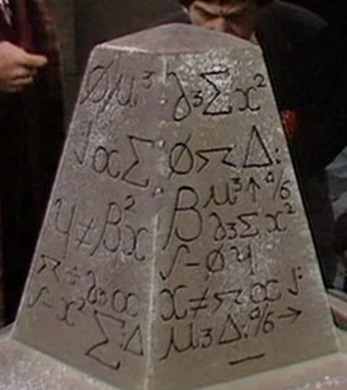

From “The Five Doctors.” Translation is given, though it’s not specified which face of the obelisk corresponds to which section of the text.

First Face:

RA NASA TO TANA EURIFSTAN OBLR ORE NATA

Ra – where

Nasa – sleep

To – in

Tana – lies, reclines, rests

Eurifstan – eternal, endless, timeless. Here it modifies the verb, so it should be rendered as an adverb.

Oblr – abbreviated form of obelar, tomb or grave

OR – the same abbreviation seen previously, “The One And Only Rassilon.”

E – an alternate version of the possessive “ya,” used only when the possessive noun is already abbreviated

Nata – a basic verb of being, is

This yields the following literal translation: Where sleep-in lies eternally, tomb Rassilon’s is.

Or as the Doctor translates it: This is the Tomb of Rassilon, where Rassilon lies in eternal sleep.

Second Face:

The text on the second face is never seen. The Doctor translates it as: Anyone who's got this far has passed many dangers and shown great courage and determination.

Third Face:

ULIREIF RAENATA TOAAN LAKI FSTA TORARO

Ulireif – to lose everything, to be utterly defeated

Raenata – an emphatic form of the being-verb nata, indicating that something really, truly, permanently is

Toa’an – to win everything, to be crowned victor

Laki – a compound conjunction combining la (so) with ki (and): “and so”

Fsta – an abbreviated form of festoa, a winner or leader

Toraro – future tense of torar, to fail or collapse

Thus: To lose all is truly to win all, and so the winner will fail.

Or as the Doctor puts it: To lose is to win, and he who wins shall lose.

Fourth Face:

KIRA ATOUNA OR TA LIRI EUKI RAATO SUTE ANAAN FEIRLIO REUNT

Kira – takes

Atouna – ring

OR – the same abbreviation seen previously, “The One And Only Rassilon.”

Ta – from

Liri – hand

Euki – a compound conjunction combining eu (then, next, afterward) with ki (and): “and then”

Ra’ato – future tense of ra’at, to wear

Sute – reward, prize, payment

Ana’an – desired, sought-after

Feirlio – future tense of feiril, to get or acquire. Note that this is an irregular verb: the last two letters switch places when adding any tense ending.

Reunt – immortality, eternity

Literally: Takes ring Rassilon-from-hand and then will wear, reward-sought will have: immortality.

Or as the Doctor translates it: Whoever takes the ring from Rassilon's hand and puts it on shall get the reward he seeks: immortality.

#doctor who#gallifreyan language#conlang#old high gallifreyan#no I have no idea how many hours I spent figuring this out#yes I'm working on figuring out the modern alphabet too (the one Four uses when he writes his letter at the beginning of Deadly Assassin)

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to know more about the Christian Bible but don't want all of the conservative riff-raff. What should I read?

A friend posed this question to me, so here are my suggestions.

Firstly, my biases: progressive politically, American, white, protestant/ELCA Lutheran, queer/gay/LGBTQ. The stuff I recommend is going to line up with these.

Quick aside on different ways Bibles are translated and interpreted

When translating an ancient language to modern English, there is no "literal" translation; that is, no translation that will be word-for-word the exact same meaning. If you have used Google Translate, you've probably noticed there are nuances that a "literal" word-swap machine translation misses. This is especially true with the Bible.

So be wary of any translation (or person or movement) that claims they follow the One True Literal Translation. That doesn't exist, and you'd be the chump in that situation. (Looking at you Evangelicals.) Conservatives and progressives are guilty of falling into that fallacy.

^ Above: A funny example of how a machine word-for-word translation misses a lot of meaning. "My dog has a hangover" machine translated to German and then back to English becomes "my dog has a cat." x

There are three main buckets of Bible translation. IMHO---and many scholars will agree---the best translation to read will actually be two or three translations. One for each method. The Bible is messages ("facts" meant to be passed down, history) and art (poetry, storytelling, song), which need their own special treatment to be understood in another language.

Some translations focus on the individual words (word-for-word/Formal Equivalence), some focus on the sentences or chunks of meaning (thought-for-thought/Dynamic Equivalence), and some try to balance the two with context a modern reader would understand (paraphrase). I won't detail it all here, but I highly recommend reading this Logos article which goes further in depth. I've included their helpful graphic below which breaks this down into four buckets, but you get what I mean.

Additionally, know which Christian tradition you want to approach this from because they include different books in their Bibles. Catholics also have a set of books called the Apocrypha, but most Protestants exclude those books. Bibles from other parts of the world have different books...

So look up the list of books you want to include too. I think it's great to read them all, but be aware that if you went to talk to someone about this they might not know what the hell you're talking about if you've read the Apocrypha and they haven't.

So tl;dr: No single Bible translation is ever going to give you the best understanding. The Bible is in an ancient language, so you need multiple perspectives to understand what it's saying as a modern reader. Modern translators and politics also influence which versions of the Bible people read, to the point of excluding whole groups of books. At least two different Bible translations that you can compare side by side is the best place to start.

A funny post by @enriquemolina that really cuts to the point.

On to the actual Bible recommendation.

Which Bibles to read

I personally use The Lutheran Study Bible by Fortress Press. It's NRSV, which is a moderate translation (mix of word-for-word translation and meaning-for-meaning) that includes supplementary materials for new learners. It's the official Bible of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (not actually evangelical but that's another long story), which I'm part of, so I'm biased. I felt like it was a solid translation to grow up reading with a focus on helping you understand what it's saying and to think about the meaning for yourself, vs dictating the meaning to you. It is not a poetic translation however, so it wasn't until I was an adult that I learned the bible was also full of songs and poetry, which today I think of as just as valuable.

I don't have a good rec for a more poetic version unfortunately, but many people still enjoy the King James Bible when they want something flowery. I too have taken verses from there for decorative purposes. BUT: it was commissioned to support the reign of King James VI and thus has decent bias written into it. It is conservative by modern terms as well.

@blessedarethebinarybreakers has a post of good recs as well. They explicitly recommend AGAINST the NIV, NIT, and ESV. Look up a conservative church near you and check which versions they recommend. Then don't read those.

Bible Gateway is a good place to read different versions side by side. Look up quotes you like or that bother you in multiple translations. It may help you decide which ones you want to ultimately buy.

I have not actually read these versions but I wanted to include them so you know your options. These were created with specific intent against bigotry, so they have a strong bias. Not that I find that problematic in this case - there's a crap ton of Bibles that were made intentionally to perpetuate bigotry. So I'm just choosing which bias I prefer.

First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament by Terry M Wildman <- Native perspective (paraphrase)

The Queen James Bible <- KJV edited to remove or explain core clobber passages, very popular with queer Catholics

The Inclusive Bible: The First Egalitarian Translation by Priests for Equality <- gendered language and other instances of bias edited out, tho I think it's still anti-gay?! (paraphrase)

Resources for inevitable encounters with bigotry

Many people avoid the Bible because the people and movements that claim it really lay the bigotry on thick and justify it with this dusty old book. If you have the interest to learn more about the Bible, very quickly you're going to encounter this bigotry in the translations and supplemental materials.

I'll tell you now on no uncertain terms: Your interpretation of the Bible does not HAVE to include bigotry, despite what many outside entities may try to tell you.

I always say, "The Bible is so big and so varied that you can 'make' it say anything. The true test is what you choose to make it say. Something hateful? Or something loving and affirming?"

It says a lot more about someone when you remove the excuse that the Bible fundamentally is full of bigoted beliefs. If you believe that racism and slavery are good and natural because it's in the Bible, as early American slavers claimed, then you're actually just human garbage. Any modern sane person knows its presence in an ancient text has no weight on today. It's the same for anything else on its pages.

Conservatives "cherry pick" meaning from the Bible that they prefer to believe, but it's just as true that so do progressives. The Bible is huge and contradictory because it's a bunch of very old texts written by a ton of different people playing a game Telephone over a few thousand years. It's full of stories, poetry, and history---with some bigotry baked in, and some applied in modern times. The stories are full of complex characters (heroes, villains, antiheroes) and history is not always pretty. The books of the Bible literally argue with each other.

^ Above: I've always enjoyed this graphic, which maps all of the times the Bible contradicts itself. That's a lot! Good thing the Bible isn't to be taken literally, that would be impossible. (Evangelicals: .....) x

Nobody is meant to replicate what's in the Bible or use it as a guidebook for how to live life to the letter. You're meant to read the arguments and come up with your own answer. (Personally I think the winning hint is how many times the protagonist talked about loving one another.)

tl;dr: If conservatives are cherry picking the Bible and progressives are cherry picking the Bible, who is flying the plane?! You are. So make the choice that doesn't hurt anybody.

Anti-Semitism and the Old Testament

I am an advocate for reading Old Testament translations (and interpretations) very critically. I'm sure all are aware of the anti-Semitism baked into Christianity. A lot of it stems from interpretation of the OT, which includes major portions of the Tanakh, the Jewish core religious text. The OT and the Tanakh are not one and the same, but they are entwined, and cause a lot of grief for everyone involved when not treated with the proper care.

Read the Old Testament separately from the rest of the Bible (the New Testament). I have really enjoyed using the free (!!) website Sefaria, an online library of Jewish texts. You can compare the Tanakh translations and commentary there to the same of the OT in your Bible of choice. (Also please throw them some money when you can, they're truly one of the great joys of the internet and operate as a nonprofit, keep them online forever.)

Beware any (Christian, New Testament) Bible translations that claim to be Jewish. There is a kind of Christian that calls themself a "Messianic Jew" that claims to recognize Jesus as the Jewish messiah. It's all very offensive, so please do not engage. Check the sources of websites and books to make sure you don't see the word Messianic. There are true academic texts by Jewish scholars that engage with Christian thought, but it will be very clear that they are not a Christian themself.

Speaking of... Another resource you must read is Better Parables. This is a website by a Jewish scholar who interprets the famous (and infamous) Christian parables of Jesus through the paradigm of Jewish academic dialogue. Many Christians have never heard non-anti-Semitic readings of a lot of New Testament content so this site offers refreshing perspective to get you out of that mindset. Particularly if you grew up with Christianity, I consider this mandatory reading.

Queer affirmation in the Bible

Personally I have moved beyond the fight against clobber passages (Bible verses interpreted to support homophobia) towards actively affirming readings of the Bible. I have tons of these resources, so I'm just gonna make a list.

Websites

Queer Theology - podcast, classes, and theological resources

Queer Grace Encyclopedia - succinct articles and links on common questions

Blessed Are the Binary Breakers - podcast and long running Tumblr blog @blessedarethebinarybreakers

Supplemental Bible interpretation

The Queer Bible Commentary by Deryn Guest, et. al. - if you can get it used for cheaper, this is a must have while reading the Bible

Take Back the Word: A Queer Reading of the Bible by Robert E Goss, et. al. - if you can't afford the above commentary, this has only a few chapters from the larger book for a better price

For your inner child

What Is God Like? by Rachel Held Evans - I literally cried reading this children's book, I'm man enough to admit it. This is what we all should have been taught about the Christian god as kids.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Context is often the container for our analyses of our experiences, and a great example of how historical fiction can engage with this is Umberto Eco's "Name of the Rose". During a scene where the character Adso of Melk, a Benedictine novice, is seduced by a peasant girl, the way he understands this novel sexual encounter is exclusively through the lens of familiar religious texts; it is by these means that he cobbles together a vocabulary to approximate the tenor of these new sentiments he's experiencing.

In the scene, Adso paraphrases sections of the Song of Songs, one of the five megillot in the Ketuvim (the last section of the Tanakh), which appears in Christian contexts as a text usually understood (in that context) to be largely about the divine, uncategorizable love between God and believers/the Church and Jesus.

Below, I attach the passage where Adso uses that aforementioned vocabulary to understand and engage with the first time he makes love.

From: Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose (trans. William Weaver).

I will attach excerpts from Song of Songs 4:1 (KJV) to highlight how much Eco accomplishes exactly what this post describes.

Further, when Eco writes Adso saying "Pulchra sunt ubera quae paululum supereminent et tument modice", it is a quotation from Gilbert of Hoyt’s Sermons on the Song of Solomon.

In this sermon, Gilbert digresses from his allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs to wax poetic about the most pleasing physical dimensions of female breasts; the quoted line translates to, "Breasts that swell a little and protrude slightly are beautiful" (which is a commentary on the following line from SoS 4:1: "Thy two breasts are like two young roes that are twins").

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can't believe I just watched a Bengali movie where a gay man and a woman settled together in what essentially boils down to a queerplatonic marriage

What a world.

#i mean like#the movie wasn't *about* them#it wasn't like 'omg massive groundbreaking moment for queer rep in indian movies'#the movie was mostly about the girl's elderly parents and also their family as a whole#but there was this amazing scene where the girl and her dad were talking and he asked her when she and her husband were having a baby#as indian parents do#and she told him never and that her husband is gay#and that she didn't know until after marriage because his parents had forced him into an arranged heterosexual marriage#and her father said - well you two should get divorced immediately because then you'll both be free#and she was like#actually no.#(the following is translated and paraphrased and not as poetic as it was in the movie.)#is marriage only good for one thing? for romance and children?#we make eachother happy. there are no lies between us. we live together and take care of one another.#ive had plenty of relationships during our marriage. he's had a boyfriend. even so we've decided to stay with eachother.#and she like talked about how their friendship is so strong and they fulfill their wedding vows to eachother without needing romance#it was nice#i don't think it was perfect or outstanding rep but i personally never expected to hear the word gay in a bangali movie#like it wasn't even bollywood guys#and like I know they didn't use the word 'queerplatonic'#but from that description I would say it fits?

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Early Red Riding Hood?

(Image Source)

The Brothers Grimm and Charles Perault are both known for their specific versions of an older faerie tale, known by modern audiences as Little Red Riding Hood. Both of these versions most likely originated from a French source; it seems that the French peasantry had been telling stories similiar to Little Red Riding Hood for centuries, if Egbert of Liège’s own poetic Latin take on a story of a girl who is saved from a wolf is an expression of this oral tradition. Although lacking the features of some of the later tellings, Egbert’s version shares a young girl wearing a red hood who is unaware of the dangers of the woods, as exemplified by a wolf.

This poetic retelling, done in fourteen hexameters, describes itself as a story that the common people recite as a true story. It can be found in the Fecunda Ratis (The Well-Laden Ship), a collection of folktales, proverbs, Biblical paraphrases, and other materials meant to help students of Latin learn the language. The following English translation is followed by the original Latin under the cut.

About A Girl Saved From Wolf Cubs

What I have to relate, countryfolk can tell along with me,

and it is not so much marvelous as it is quite true to believe.

A certain man took up a girl from the sacred font,

and gave her a tunic woven of red wool;

sacred Pentecost was the day of her baptism.

The girl, now five years old, goes out

at sunrise, footloose and heedless of her own peril.

A wolf attacked her, went to its woodland lair,

took her as booty to its cubs, and left her to be eaten.

They approached her at once and, since they were unable to harm her,

began, free from all their ferocity, to caress her head.

“Do not damage this tunic, mice,” the lisping girl said,

“which my godfather gave me when he took me from the font!”

God, their creator, soothes untame souls.

There is some debate as to whether this story is actually a predecessor to Little Red Riding Hood or not; there is no grandmother element to this story, after all, and the distinctively masculine predator overtones found in Perrault’s wolf are not present here. Yet in both this story and Perrault’s, the red hood is explicitly mentioned to be the gift of a benefactor (grandma or godfather). Given that folktales rarely have a stable canonical form, it’s possible that the versions written by Perrault and collected by the Brothers Grimm simply represent a different strand of thematic development - that, while perhaps not a direct ancestor of Little Red Riding Hood, Egbert’s version is nonetheless a branch on this story’s family tree.

Source: A Fairy Tale from Before Fairy Tales: Egbert of Liège's "De puella a lupellis seruata" and the Medieval Background of "Little Red Riding Hood," by Jan M. Ziolkowski

De puella a lupellis seruata

Quod refero, mecum pagenses dicere norunt,

Et non tam mirum quam ualde est credere uerum:

Quidam suscepit sacro de fonte puellam,

Cui dedit et tunicam rubicundo uellere textam:

Quinquagesima sancta fuit babtismatis huius.

Sole sub exorto quinquennis facta puella

Progreditur, uagabunda sui inmemor atque pericli,

Quam lupus, inuadenns siluestria lustra petiuit

Et catulis predam tulit atque reliquit edendam.

Qui simul aggressi, cum iam lacerare nequirent,

Ceperunt mulcere caput feritate remota.

“Hanc tunicam, mures, nolite”, infantula dixit,

“Scindere, quam dedit excipiens de fonte patrinus!”

Mitigat inmites animos deus, auctor eorum.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fake Hafez: How a supreme Persian poet of love was erased | Religion | Al Jazeera

This is the time of the year where every day I get a handful of requests to track down the original, authentic versions of some famed Muslim poet, usually Hafez or Rumi. The requests start off the same way: "I am getting married next month, and my fiance and I wanted to celebrate our Muslim background, and we have always loved this poem by Hafez. Could you send us the original?" Or, "My daughter is graduating this month, and I know she loves this quote from Hafez. Can you send me the original so I can recite it to her at the ceremony we are holding for her?"

It is heartbreaking to have to write back time after time and say the words that bring disappointment: The poems that they have come to love so much and that are ubiquitous on the internet are forgeries. Fake. Made up. No relationship to the original poetry of the beloved and popular Hafez of Shiraz.

How did this come to be? How can it be that about 99.9 percent of the quotes and poems attributed to one the most popular and influential of all the Persian poets and Muslim sages ever, one who is seen as a member of the pantheon of "universal" spirituality on the internet are ... fake? It turns out that it is a fascinating story of Western exotification and appropriation of Muslim spirituality.

Let us take a look at some of these quotes attributed to Hafez:

Even after all this time,

the sun never says to the earth,

'you owe me.'

Look what happens with a love like that!

It lights up the whole sky.

You like that one from Hafez? Too bad. Fake Hafez.

Your heart and my heart

Are very very old friends.

Like that one from Hafez too? Also Fake Hafez.

Fear is the cheapest room in the house.

I would like to see you living in better conditions.

Beautiful. Again, not Hafez.

And the next one you were going to ask about? Also fake. So where do all these fake Hafez quotes come from?

An American poet, named Daniel Ladinsky, has been publishing books under the name of the famed Persian poet Hafez for more than 20 years. These books have become bestsellers. You are likely to find them on the shelves of your local bookstore under the "Sufism" section, alongside books of Rumi, Khalil Gibran, Idries Shah, etc.

It hurts me to say this, because I know so many people love these "Hafez" translations. They are beautiful poetry in English, and do contain some profound wisdom. Yet if you love a tradition, you have to speak the truth: Ladinsky's translations have no earthly connection to what the historical Hafez of Shiraz, the 14th-century Persian sage, ever said.

He is making it up. Ladinsky himself admitted that they are not "translations", or "accurate", and in fact denied having any knowledge of Persian in his 1996 best-selling book, I Heard God Laughing. Ladinsky has another bestseller, The Subject Tonight Is Love.

Persians take poetry seriously. For many, it is their singular contribution to world civilisation: What the Greeks are to philosophy, Persians are to poetry. And in the great pantheon of Persian poetry where Hafez, Rumi, Saadi, 'Attar, Nezami, and Ferdowsi might be the immortals, there is perhaps none whose mastery of the Persian language is as refined as that of Hafez.

In the introduction to a recent book on Hafez, I said that Rumi (whose poetic output is in the tens of thousands) comes at you like you an ocean, pulling you in until you surrender to his mystical wave and are washed back to the ocean. Hafez, on the other hand, is like a luminous diamond, with each facet being a perfect cut. You cannot add or take away a word from his sonnets. So, pray tell, how is someone who admits that they do not know the language going to be translating the language?

Ladinsky is not translating from the Persian original of Hafez. And unlike some "versioners" (Coleman Barks is by far the most gifted here) who translate Rumi by taking the Victorian literal translations and rendering them into American free verse, Ladinsky's relationship with the text of Hafez's poetry is nonexistent. Ladinsky claims that Hafez appeared to him in a dream and handed him the English "translations" he is publishing:

"About six months into this work I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to 'my artists and seekers'."

It is not my place to argue with people and their dreams, but I am fairly certain that this is not how translation works. A great scholar of Persian and Urdu literature, Christopher Shackle, describes Ladinsky's output as "not so much a paraphrase as a parody of the wondrously wrought style of the greatest master of Persian art-poetry." Another critic, Murat Nemet-Nejat, described Ladinsky's poems as what they are: original poems of Ladinsky masquerading as a "translation."

I want to give credit where credit is due: I do like Ladinsky's poetry. And they do contain mystical insights. Some of the statements that Ladinsky attributes to Hafez are, in fact, mystical truths that we hear from many different mystics. And he is indeed a gifted poet. See this line, for example:

I wish I could show you

when you are lonely or in darkness

the astonishing light of your own being.

That is good stuff. Powerful. And many mystics, including the 20th-century Sufi master Pir Vilayat, would cast his powerful glance at his students, stating that he would long for them to be able to see themselves and their own worth as he sees them. So yes, Ladinsky's poetry is mystical. And it is great poetry. So good that it is listed on Good Reads as the wisdom of "Hafez of Shiraz." The problem is, Hafez of Shiraz said nothing like that. Daniel Ladinsky of St Louis did.

The poems are indeed beautiful. They are just not ... Hafez. They are ... Hafez-ish? Hafez-esque? So many of us wish that Ladinsky had just published his work under his own name, rather than appropriating Hafez's.

Ladinsky's "translations" have been passed on by Oprah, the BBC, and others. Government officials have used them on occasions where they have wanted to include Persian speakers and Iranians. It is now part of the spiritual wisdom of the East shared in Western circles. Which is great for Ladinsky, but we are missing the chance to hear from the actual, real Hafez. And that is a shame.

So, who was the real Hafez (1315-1390)?

He was a Muslim, Persian-speaking sage whose collection of love poetry rivals only Mawlana Rumi in terms of its popularity and influence. Hafez's given name was Muhammad, and he was called Shams al-Din (The Sun of Religion). Hafez was his honorific because he had memorised the whole of the Quran. His poetry collection, the Divan, was referred to as Lesan al-Ghayb (the Tongue of the Unseen Realms).

A great scholar of Islam, the late Shahab Ahmed, referred to Hafez's Divan as: "the most widely-copied, widely-circulated, widely-read, widely-memorized, widely-recited, widely-invoked, and widely-proverbialized book of poetry in Islamic history." Even accounting for a slight debate, that gives some indication of his immense following. Hafez's poetry is considered the very epitome of Persian in the Ghazal tradition.

Hafez's worldview is inseparable from the world of Medieval Islam, the genre of Persian love poetry, and more. And yet he is deliciously impossible to pin down. He is a mystic, though he pokes fun at ostentatious mystics. His own name is "he who has committed the Quran to heart", yet he loathes religious hypocrisy. He shows his own piety while his poetry is filled with references to intoxication and wine that may be literal or may be symbolic.

The most sublime part of Hafez's poetry is its ambiguity. It is like a Rorschach psychological test in poetry. The mystics see it as a sign of their own yearning, and so do the wine-drinkers, and the anti-religious types. It is perhaps a futile exercise to impose one definitive meaning on Hafez. It would rob him of what makes him ... Hafez.

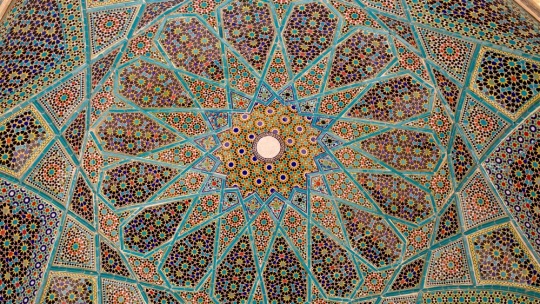

The tomb of Hafez in Shiraz, a magnificent city in Iran, is a popular pilgrimage site and the honeymoon destination of choice for many Iranian newlyweds. His poetry, alongside that of Rumi and Saadi, are main staples of vocalists in Iran to this day, including beautiful covers by leading maestros like Shahram Nazeri and Mohammadreza Shajarian.

Like many other Persian poets and mystics, the influence of Hafez extended far beyond contemporary Iran and can be felt wherever Persianate culture was a presence, including India and Pakistan, Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Ottoman realms. Persian was the literary language par excellence from Bengal to Bosnia for almost a millennium, a reality that sadly has been buried under more recent nationalistic and linguistic barrages.

Part of what is going on here is what we also see, to a lesser extent, with Rumi: the voice and genius of the Persian speaking, Muslim, mystical, sensual sage of Shiraz are usurped and erased, and taken over by a white American with no connection to Hafez's Islam or Persian tradition. This is erasure and spiritual colonialism. Which is a shame, because Hafez's poetry deserves to be read worldwide alongside Shakespeare and Toni Morrison, Tagore and Whitman, Pablo Neruda and the real Rumi, Tao Te Ching and the Gita, Mahmoud Darwish, and the like.

In a 2013 interview, Ladinsky said of his poems published under the name of Hafez: "Is it Hafez or Danny? I don't know. Does it really matter?" I think it matters a great deal. There are larger issues of language, community, and power involved here.

It is not simply a matter of a translation dispute, nor of alternate models of translations. This is a matter of power, privilege and erasure. There is limited shelf space in any bookstore. Will we see the real Rumi, the real Hafez, or something appropriating their name? How did publishers publish books under the name of Hafez without having someone, anyone, with a modicum of familiarity check these purported translations against the original to see if there is a relationship? Was there anyone in the room when these decisions were made who was connected in a meaningful way to the communities who have lived through Hafez for centuries?

Hafez's poetry has not been sitting idly on a shelf gathering dust. It has been, and continues to be, the lifeline of the poetic and religious imagination of tens of millions of human beings. Hafez has something to say, and to sing, to the whole world, but bypassing these tens of millions who have kept Hafez in their heart as Hafez kept the Quran in his heart is tantamount to erasure and appropriation.

We live in an age where the president of the United States ran on an Islamophobic campaign of "Islam hates us" and establishing a cruel Muslim ban immediately upon taking office. As Edward Said and other theorists have reminded us, the world of culture is inseparable from the world of politics. So there is something sinister about keeping Muslims out of our borders while stealing their crown jewels and appropriating them not by translating them but simply as decor for poetry that bears no relationship to the original. Without equating the two, the dynamic here is reminiscent of white America's endless fascination with Black culture and music while continuing to perpetuate systems and institutions that leave Black folk unable to breathe.

There is one last element: It is indeed an act of violence to take the Islam out of Rumi and Hafez, as Ladinsky has done. It is another thing to take Rumi and Hafez out of Islam. That is a separate matter, and a mandate for Muslims to reimagine a faith that is steeped in the world of poetry, nuance, mercy, love, spirit, and beauty. Far from merely being content to criticise those who appropriate Muslim sages and erase Muslims' own presence in their legacy, it is also up to us to reimagine Islam where figures like Rumi and Hafez are central voices. This has been part of what many of feel called to, and are pursuing through initiatives like Illuminated Courses.

Oh, and one last thing: It is Haaaaafez, not Hafeeeeez. Please.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial stance.

This content was originally published here.

241 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Since J. Thomas Shaw’s 1965 observation that Nabokov’s translation was ‘written in a language of his own,’ much ink has been spilt in an effort to conceptualize this effect. Did Nabokov seek to ‘estrange’ Pushkin and by doing so elevate him to the level of the ‘creative genius’ he believed he was? If no ‘poetical’ paraphrase can do justice to Homer or Shakespeare, as he states in “Problems of Translation: Onegin in English,” no translation can attain the level of Pushkin’s perfection. Tempting as it is to follow this ennobling interpretation, it proves to be based on a misunderstanding. As Brian Boyd has pointed out, not only did Nabokov never intend for his translation to stand on its own, he laboured to underscore its dependence on the original by interspersing Pushkin’s lines with his. It was only due to the technical difficulty of achieving such an effect that ‘the translation was not printed […] in interlinear fashion, beneath Pushkin’s transliterated lines.’ As Judson Rosengrant has shown, however, no matter where it is reproduced, Nabokov’s English may never become altogether neutral and transparent. As if to compensate for its inability to recreate the stylistic interplay of its model, it seeks to become a ‘concoction,’ ‘a hybrid of modern British and American English (with Gallic and archaic admixtures) […] a pastiche of Pushkin’s early nineteenth-century Russian.’ This quality of Nabokov’s English proves that it may never be separated from its Pushkinian model.

Stanislav Shvabrin, Between Rhyme and Reason: Vladimir Nabokov, Translation, and Dialogue (298)

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

Certainly, it is impossible to translate in full such a complex poetic structure based on switching intonations and playing with cultural symbols, filled with associations and citations, into a foreign language. Yu.M. Lotman notes the following not without reason: "Eugene Onegin" is "certainly the most complicated work of Russian literature, which loses much at translation" (Lotman, 1988).

Pushkin's verses lose their lightness; Pushkin’s sound recording, which is also built on alliteration, is also lost...The uniqueness of Pushkin's creation,which made him "untranslatable," is a reason why the greatest Russian poet did not take the place he should have taken in world literature. The purpose of this study is to analyze the way "Eugene Onegin" is represented in the modern English-speaking linguacultural space.

The comparison of Pushkin's place in Russian literature and culture with Shakespeare’s place in the English-speaking world is rather common, but Western critics, writers,and translators usually note that while Shakespeare's works can be easily translated into other languages, Pushkin's poetry loses almost everything in translation because his poetry is simply inseparable from the power of the Russian language. It is appropriate here to recall the words of E. Sapir who, arguing about the translatability/untranslatability of the literary text, pointed to the existence of two different types or levels of art: one of them is "generalizing, extralinguistic art, which can be expressed through the means of another language without detriment", and the second one is "specifically linguistic art, which is essentially untranslatable".

Nabokov categorically states that "the clumsiest literal translation is a thousand times more useful than the prettiest paraphrase" (Nabokov, 2003). [Nabokov] calls the literal translation "honest" (compare with the opinion of Chukovsky, who considers it "the most false") .

The film director M. Fiennes was interested primarily in the inner world of the characters and the universality of love in time and space. According to E.N. Shapinskaya, an author of the article "‘Eugene Onegin’ in the Eyes of the Other: the British Interpretation in Cinema and on Opera Stage": “This is symptomatic of the modern view on the classical heritage, which is attractive not for its ‘otherness,’ but for its universal values, which is due to the loss of the authenticity of ethno-cultural communities in our pluralistic world of countless ‘others’” (Shapinskaya, 2015).

#lizlensky has me thinking deep about language :D <3 so i went feral this sunday afternoon and read this#it's a really interesting article I hope to find more like it#THAT LAST SENTENCE/QUOTE THOUGH... wow.... that is a whole lot to chew on.... *has a major crisis*#onegin#pushkin#ref#is this blog getting too nerdy yet?? ;')

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lightning Axe

“What is the axe?”

Helena had been eying the weapon, which was a beautiful example of blade-craft, even if it did smell so strongly of blood that it made her hungry every time she was in the same room as it was. All the same, she could smell the magic rolling off it, like the smell of a storm right before the very first flash of lightning.

It was heady, and she was intensely curious about it.

Owen held it like it was made for him. Maybe it was. Family weapons often took on the favored grip of the latest family member to handle them. Owen had said the axe was his great-grandfather’s, but it looked, and smelled, significantly older than three generations of human.

“Well, well.”

Teucer drifted in, impeccable as always in his favorite white suit, expensive designer scarf draping around his neck in place of a tie. Owen, who had a good instinct for that which could kill him, was always a little uneasy around Teucer, and still hadn’t figured out why. Helena felt a little bad for not letting him in on the secret, but she held her tongue nonetheless. Her sire’s request was significantly more powerful than her fondness for a human, even this one.

Unfortunately that meant that Owen got nervous whenever Teucer was closer than ten paces away.

Not that ten paces would actually help him if Teucer decided to harm him, but Teucer wouldn’t, and Owen didn’t need to know that.

“The Axe of Perun,” Teucer continued, and ran one fingertip over the blood-stained handle of the ancient weapon. He gave Owen a very speculative once-over, and tilted his head as he thought. “Last I heard, this had vanished during the thirteen-hundreds or so. Something about a particularly violent extermination of the local troll population, and a nasty little war to follow.”

“It’s been in my family for a while,” Own replied, and snickered when the axe, which really didn’t like non-humans touching it, shot a violent spark of lightning into Teucer’s fingertip. He squawked and stuck his finger in his mouth, eyes wide and hurt. Helena smiled faintly. The drama queen. He was healed almost before the lightning faded. “We tried to stick it in a museum once. It appeared under Grandfather’s bed that night. He mostly used it for splitting wood.”

“It certainly does have an attitude,” Teucer observed, and took a cautious step back from the axe, which crackled smugly at him. “And quite the attitude. Is Perun still in there?”

The axe of Perun. Supposedly forged from the steel scale of a god of the underworld, and set into a handle cut from the World Tree. Helena knew the legends, mostly because Teucer loved mythology so much, but she had never seen the weapon in person.

“We don’t know,” Owen said, and lifted the ae with ease. It looked right when he propped it on his shoulder, red handle bright against his soft grey shirt. “Family legend says that Perun gave it to us when we first started hunting monsters. No idea if it’s true. We weren’t big on writing the family history down at that point.”

“Too busy killing trolls?”

“And then there was that war you mentioned. We moved to England and Scotland after that.”

Teucer chuckled and leaned in to look at the axe again. Helena watched as he, without touching the blade, read through the runes that marched invisibly down the handle.

“What do they say?” she asked, unable to contain her own curiosity. Teucer could certainly read them, although she couldn’t. Of course, she hadn’t made a study of the ancient languages like he had.

Also, he was old enough that some of those ‘ancient’ languages were his contemporaries.

“Send back to the Underworld, that which belongs there,” he translated, and beamed at Owen. “Paraphrased, of course. The proper translation is less poetic in English. That’s a fine weapon for one who lives to kill non-humans.”

“Not non-humans,” Owen corrected him, and traced the runes before closing his hand around the handle again and setting the axe back on the table. “Monsters. Right now, the only monster I’m after is human to the core.”

“That may be what’s wrong with him,” Teucer observed thoughtfully, and leaned on the desk, far enough away from the axe that, although it crackled warningly at him, he was out of reach. “You’re an interesting one. I’ll be watching you closely.”

With that he drifted back out of the room the same way he came, and Helena only sighed.

Owen looked between them incredulously, and shook his head.

“I know you’re not gonna tell me,” he said and took a long swig from his water bottle. “But I would really like to know who the hell he is.”

“You wouldn’t like the answer,” Helena told him, and leaned over to steal a slow kiss. He combed his fingers through her hair, and smiled at her with an emotion she didn’t care to name in his eyes. “I trust him.”

“That’s enough for me,” Owen murmured, and kissed her again before reaching for his axe. “I need to train with this thing. Want to come dance with me?”

“I suppose I could be convinced,” she allowed and took his free hand in hers, all too aware that the coming battle might take him from her. She was fast, but no one was faster than Death, and Owen was human. She would enjoy what time she had with him. “But I may insist you wrap the blade. Bullets are no bother to me, but the Axe of Perun is made to kill things like me, and I would rather not be killed on this day.”

+++

HGE - Blood and Passion:

Helena is one of the most powerful Elder Vampires in the city, and known for fairness, and ruthlessness in equal measure.

She did not expect a bleeding Hunter to seek her out as his last, best hope.

Feeding Frenzy

White Marble

First Negotiation

Blood Summit

Blood Claim

CovenHold

Wolf Club

Blood-Traitor

Shared Blood

Long Past

In the Ring (Subscriber Only)

Ancient Ballroom (Subscriber Only)

A Weapon of the Old Age

+++

More Stories!

+++

#vampire#vampires#magic#spells#romance#love#blood#mentions of violence#myth#mythologica#troy#cool#fighting#history#teucer#Greek Mythology#norse mythology#slavic mythology#axel kicillof#weapon#weapons#battle#troll#trolls#trolli

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lecture 4

I was isolating during this lecture so borrowed the following notes from one of my peers. The notes will be helpful for providing a framework for the contextual knowledge paragraph of my exegesis.

The culture of academic rigor: does design research really need it?

Cannes lion gold - advertising awards

For designers, what would the big issue be?

What are the intercontextual relationships:

Public service advertising: advertising for social issues

Saul Bass

Sufficiently exposed to the world as a designer to be able to position your work

1-2 Areas: Theory, practice

If you're doing practice, can you put your practice in the context of other practice?

Disjecta Membra:

From a few fragments you can put together the whole again

To be able to assemble something from fragments

Abstract:

Keywords

“This project explores the concept of disjecta membra through the media form of poetry fil. The thesis considers the multiple [poetic retelling of the death of john the baptist drawing on insp[iration from oscar wiles banned play salome.

Thus, the work translates fragments of selected, historical, poetic texts related to the subject. In doing so the poetry film creatively explores the potential of the fragments ….

Opening paragraph in this project, the film poem jokanaan a disjecta membra portrays the final moments of the death of john the baptist. It is influenced by themes of fin de .. symbolism, erotic transgression.

3-5 Key ideas:

Disjecta membra:

harter

Elias

Most

Theme:

Context

Context

Context

Abstract: cracks in time

This study considers ways of reading eroded signages exposed to roces of time, materiality adn elements, urban signs may tell stories that reach beyond their original meanings

Using the potentials of spacial-temporal typography, sound and narration, the research project seeks to communicate subjective experiences through a creative expression…

Opening:

This chapter considers contextual meaning relating to the study. It begins with a review of literature associated with eroded signage as a signifier of meaning — other two areas

Research:

Chronological

Evolution

Paraphrase rather than quote

Recent research

No overclaiming

What kinds of knowledge do we use?

Use two kinds of knowledge:

Explicit knowledge: Knowledge that is physical in the world: books, library, article etc - the knowledge you will pick from things that exist explicitly

Tacit knowledge: the knowledge you use that you don’t know you have, you have knowledge that you don't know about but you are using all the time to make decisions. You may seek to broaden your knowledge to increase tacit knowledge. Curious people have a lot of tacit knowledge

0 notes

Text

A New Beginning

John Sawyer

Bedford Presbyterian Church

2 / 21 / 21 – First Sunday in Lent

Psalm 25:1-10

Mark 1:9-15

“A New Beginning”

(A Prayer for Starting Over – Again and Again)

As we get closer to the one-year anniversary – if you want to call it that – of the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, I have heard more than one person refer to this odd year as having the same, unchanging rhythm. “It’s like Groundhog Day,” they say. For those of you who don’t get this ancient movie reference. There was this movie called Groundhog Day that came out back in the distant past of 1993. In the movie, the main character is forced to relive the same day over and over – again and again.

Since the pandemic began, I have heard several people talk about how one day seems to blend into the next and one week blends into the next – over and over, again and again. It’s like we are caught in some kind of loop, and – because we can’t go to many of the usual places or plan many of the usual events we used to – we find ourselves stuck in this unending cycle of wake up, do work or school from home, eat dinner, watch Netflix, go to bed, rinse and repeat – again and again. And yet, even though there is this undercurrent of “sameness,” the days still pass, the seasons still change. . . life still happens.

On this first Sunday in the Season of Lent, the seasons have changed and, yet again, we have begun our forty-day Lenten journey from Ash Wednesday to Easter. Now, there are some people for whom Lent might be just a blip in their lives, if it registers at all. And, there are other people who think about Lent as a time to give up something – chocolate, alcohol, red meat, Facebook. Anyway, Lent can be all about giving something up, or it could be all about taking something on – like a new spiritual practice or healthy habit – all in the name of reorienting one’s life around something helpful and holy. The Season of Lent is yet another opportunity for a fresh start – a new beginning – letting go of things that need to be let go of and/or taking up something that needs to be taken up, and starting life again with a new beginning – a new way of life, a new direction, a new path – in mind.

In today’s first reading from the Gospel of Mark, we see a new beginning – a fresh path. God is doing a new thing – forging a new path – here on earth. It should be noted that Mark’s Gospel is not filled with a lot of detail. We would need to read the Gospels of Luke and Matthew to find out a little bit more about Jesus – the circumstances of his birth, and his family, where he was raised, what kind of child he was.[1] In Mark, Jesus – a guy from the small town of Nazareth – just comes onto the scene and goes from 0 to 100 in quick succession – boom, boom, boom – Jesus is baptized, and suddenly he is God’s Son, the Beloved, with whom God is well pleased, and then immediately, he is driven by the Holy Spirit out into the wilderness where he is tested, and then he goes back home to Galilee and tells people, “Time’s up! God’s kingdom is here. Change your life and believe the Message.”[2]

This is how God’s new beginning for all of creation begins. Up until now, everyone has been living their lives – perhaps hoping for something new. And, now, here is Jesus – God’s “something new” for all creation: “the time is fulfilled, and the Kingdom of God has come near; repent – turn your life around, reorient yourself toward God – and believe the good news.” (Mark 1:15)[3]

Now, you and I read this story with a certain perspective. We know what both the Bible and history tell us – that Jesus will start to teach, and heal, and feed, and welcome, that he will suffer, and die, and rise again, and make a profound difference in the course of history. And so, we read today’s passage with this extra knowledge.

But if we were to somehow remove all of what we already think and know about Jesus and just see this humble, lone figure – Jesus of Nazareth – going down the path into the river to be baptized, and then wandering into the pathless wilderness, and then walking the well-trod path back home to Galilee, and if we were told that this person is God’s new beginning, I wonder what we might think of it all. Is this really the path that God is taking for all of humanity – one solitary figure, filled with the Holy Spirit? Is this all there is? Is this thing going to work out okay?

If we were to hear the story of Jesus without knowing any of the spoilers, beforehand, we might wonder just where God is taking us in this story. And, if we were to hear the message of repentance and good news from this thin person who has been fasting in the wilderness, and decide to go deeper, and follow along the path that Jesus treads, we might discover just how hard this path can be for mere mortals like you and me who are trying to do the right thing, trying to be on the right path.

In today’s second reading, from Psalm 25, we find the prayer of someone who is trying to turn toward God and follow the path – the way – that God has laid out.

Just so you know, we’re going to be spending some time with the Book of Psalms during this Lenten season. And, if there is anything you need to know about the Psalms – besides the fact that it is the longest book in the Bible – it is full of song lyrics – ancient hymns. Just as an aside, sometimes, the people who wrote the Psalms would use fun poetic devices in their writing. For example, today’s psalm is an “acrostic” psalm because it begins with each letter of the alphabet, in order [A, B, C. . . Aleph, Bet, Gimel. . .]. Anyway, very rarely do the Psalms come with a backstory, though sometimes they do. It is thought, though, that many of the Psalms were written by King David and Psalm 25 is one of David’s.

We don’t get any backstory with Psalm 25, but several things are clear: David knows how it feels to be ashamed and defeated, to feel lost, and sinful, and forgotten. Maybe you can relate. I know I can. But David also knows how to pray. And, pray he does. I am paraphrasing here:

O Lord, I am lifting myself – my soul, my life, my appetites,

and passions, and emotions[4] – over to you. . . all of who I am.

And I am falling down on my face in front of you because I trust you. . .

Make me to know your ways, O Lord. Teach me your paths.

Show me your way of life, O Lord. [5]

Lead me in your truth, and teach me, for you are the God of my salvation.

I am waiting for you – eagerly stretching out to you[6] – all day long.

Give me a new beginning with your steadfast love.

God, please do remember your steadfast love

and please don’t remember any of the bad things I’ve done. . .

The Lord instructs sinners like me in the way to live.

The Lord leads the humble in what is right

and teaches the way to those who humbly trust.

All the paths of the Lord are steadfast love and faithfulness

for those who are earnestly trying to be on the path –

to follow the way of the Lord.[7]

This last part – the part about how “all the paths of the Lord are steadfast love and faithfulness” (Psalm 25:10) – is interesting to me. One alternate translation reads, “All the Lord’s paths are kindness and truth.”[8] But the way Eugene Peterson translates it is, “From now on every road you travel will take you to God.”[9]

In other words, there might just be something Holy about whatever path we are traveling in life – whether we are going down into the river to be washed in the waters of baptism, or wandering out in the wilderness, or living into our calling as those who are sharing good news, or maybe we’re just looking for a new beginning in life. . . a new beginning with each new day, with every moment, with every step along the way.

For the Psalmist, the key to this new beginning is humble trust, because “the Lord leads the humble in what is right and teaches the way to those who humbly trust.” (25:9) I think I might have told you before about a friend of mine who, every year, jokes that she is giving up humility for Lent.[10] I’m here to say that maybe we shouldn’t give up humility quite yet. Those whose minds and hearts and spirits are “bowed down”[11] before the Lord may just be like the meek who inherit the earth.[12] Besides, we are called to follow in the footsteps of Jesus who humbly trusted in the Lord as he went down to the river, and out into the wilderness, and back home with a word of good news for all people. Wherever he went, his steps were blessed because they were leading somewhere – somewhere Holy. What if our steps are blessed, too? What if God is leading us somewhere Holy, too?

You know, almost a year into this pandemic, I don’t know if you have come to church this morning from the comfort of your own home with some nagging thought in the back of your mind that tomorrow is Monday – the day when the weekly loop of day blending into day will begin again.

It can be fairly easy to fall into this way of thinking that maybe will change when this whole thing is over – but, alas, it ain’t over yet. . . We don’t have to live on pandemic time, though, because Jesus invites us to live on fulfilled time[13] – time that is full of the kingdom of God and God’s grace. Every day is not Groundhog Day. It is God’s new day. It might seem like we’re living life on some kind of a loop, but the God that we come to know in Jesus Christ is always offering us an off-ramp. Again and again, by God’s grace, the loop becomes a path, a way of life that is actually going somewhere. . . out of the waters of baptism, through any wilderness we might imagine, and into a life that is full of meaning because Jesus has fulfilled it.

This way of life is a new beginning, offered to us in every moment, with every step along all the paths of the Lord that we might be walking. . .

We do not walk alone, my friends. We walk with Jesus, who is the way, the truth and the life[14] – our new beginning and our Holy end.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

------------

[1] See Matthew 1-2 and Luke 1-2.

[2] Eugene Peterson, The Message – Numbered Edition (Colorado Springs: NAV Press, 2002) 1377. Mark 1:15.

[3] Paraphrased, JHS.

[4] F. Brown, S. Driver, and C. Briggs. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Peabody: Hendrickson Publications, 1997) 659.

[5] Brown-Driver-Briggs, 73.

[6] Brown-Driver-Briggs, 875.

[7] Psalm 25:1-2a, 4-10. Paraphrased, JHS.

[8] Robert Alter, The Book of Psalms – A Translation with Commentary (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2007) 85.

[9] Eugene Peterson, 709. Psalm 25:10a.

[10] S.R.D. This joke never gets old.

[11] Brown-Driver-Briggs, 776.

[12] See Matthew 5:5.

[13] Paraphrase from a sermon title I heard recently. With gratitude to The Reverend Dr. Chris Thomas - https://day1.org/weekly-broadcast/6022aef76615fb41e500005e/chris-thomas-living-on-fulfilled-time.

[14] See John 14:6.

0 notes

Text

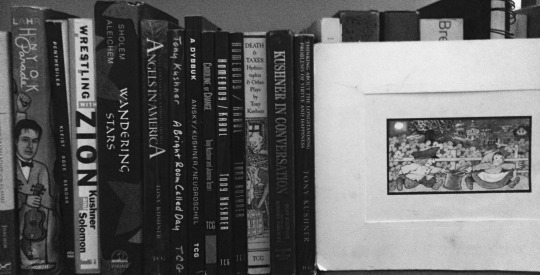

Angels Abounding [-fall 2010]

I first found Angels in America at age twelve in a moment consumed by consumerism, a chance encounter in a now-closed bookstore that left my life forever changed. The play has mostly been a thing of paper-and-binding for those my age (22 years old, let’s say)—not unlike the circumstances that bring Tony Kushner’s “Homebody” in the first act of Homebody/Kabul, another of his masterpieces, to the hat shop on “—” Street in London {Kushner does not have her name the street; it’s an authorial elision to be enacted in performance with the gestural sweeping of a hand.}, where she discovers her destiny: a journey vis-à-vis which she is ultimately lost, though Kabul is, for better or for worse, found. Buying something like a book can do that. For all its theatricality, Angels (as we may abbreviate it from hereon out) is not oft-performed in America, except for piecemeal servings in collegiate “Introduction to Acting” courses, where freshmen imitate Mormons and pill-poppers, as they sit bedside—beside the threshold of revelation, the un-bedding of truth. For those of us who have read it in one of its many published incarnations—hardcover or paperback, poster art by Milton Glaser or by the public relations team at HBO—there are always Angels bedside or on our library shelves, waiting to land (à la Spielberg) before us, for us to wrestle to the ground.

I couldn’t even afford Angels when I first encountered it, at the age of twelve (or maybe it was thirteen) in my local Border’s Bookstore, with its metallic wings etched across the letter “A,” jutting out in bas-relief from a softer surface. “Angels in America,” the cover read, on the side, “A Gay Fantasia on National Themes.” A gay book, in hardcover? I’d seen gay books: soft-core, soft-cover word porn in the “Gay Lit” aisle that I used to allow my wandering, preteen eyes to haltingly rest upon, and then performatively, dramatically avert—but here, shrink-wrapped in a collector’s case upon a table labeled “Classics” just steps away from the Children’s Section sat a gay book about national themes? Implausible, thought I—when such a thing, as I saw it then, was marginal, concealed, bound in books in the restricted sections of libraries, glanced at with dirty eyes discreetly in dusty corners, and just as discreetly re-shelved? And now, here, it was glorified, canonized alongside books where there wasn’t—couldn’t be—anything by way of content that was remotely gay? (James Baldwin. Marcel Proust. Melville.)

I couldn’t afford such a spectacular edition then, thick-spined, beautifully-boxed, and premium-priced, without outing myself to my parents who would surely ask what the money would go to buy—and it being so divinely shrink-wrapped as it was, I couldn’t just open it up and read it, sitting between the shelves or in the corner of the coffee shop of this soon-to-close bookstore franchise. So I visited my Middle School Library, where I found Perestroika, (the second of two plays comprising Tony Kushner’s two-part epic), there, waiting for me, in accessible, uncensored, open air. (Only later would I score myself a copy of Millennium Approaches, the first of the two parts, at the central county library.)

Yes, I read Angels in America backwards; so it was all grounded angels and dying men and great work and falling apart—and none of the hurtling lovesick, forward at first for me. I had to read the speech given by the “Oldest Living Soviet” before I could scan the sermon of the all-too-familiar Rabbi; and I had to end the great journey, before it had even begun. Characters found hope before they were hurt (or hurt), and healing before they harmed (or were harmed)—in diastole a beat before systole, already progressing long before those same hearts had ever been first broken. It was difficult, then, at the end of the end, to begin again, at Kushner’s actual beginning, where he first introduced the argument he only reveals and concludes in the final, last line of Perestroika—when he returns to the pain that must empower progress. The poverty of the chronology of my reading was an inherent setback, forcing me to return in Millennium Approaches to the illness that Perestroika had salvaged into health, and the pain that, in the latter-half of the play, becomes latter-day progress—working backwards against Kushner’s robust argument, directly challenging the dialectic Kushner romanticizes, poeticizes into a matter of hearts, the heart; a play that ends with life begins with death, and it is too, too hard (both to follow the line of argument and to go on the characters' narrative journey) to experience the plays in reverse. I do not recommend it.

I will finally see a performance of Angels in America this fall on the day of Yom Kippur, which commemorates Jewish mourning, sins, guilt, all such fallen things. Fitting, perhaps, for a play which seeks to prove the pertinence of history’s fallen—of pain, to progress, (in a way no other play seems to have made so strongly since Antigone made her claim or the maidens first became suppliant,). I will see the play instead of attending afternoon Yizkor services, when I am meant to light a candle in remembrance of and mourning for my late father.

Why is there still no play to me but Angels, (though Brecht is loved, Miller is worshipped, Shakespeare is memorized, and Euripides is lionized)? Why is it this play’s dramaturgy of heartbreak that renders me breathless, and its playwright the one whose epigraphs I follow to their sources, near-blindly? If a book is, (but for the HBO adaptation which premiered in our later years), the only form Angels has taken for the relatively young—and if a book is a key to unlock a door to a secret passageway from the As-Is World toward Wonderland—why did we (do we) choose this Wonderland (passageway, door, lock, book, etc.)—a derelict hospital wing of forgotten, fractured, and fallen angels—ailing angels who never had wings, and black nurses born quite problematically into a world awash in whiteness? Why do we wish ourselves (through the act of reading and re-reading) into a world of corrupted bureaucrat-angel courts and heavens that can’t even hear our prayers over the static from their broken radios—rather than, say, to Hogwarts? Why do we children born the morning after “morning in America” re-read ourselves into the mise-en-scène of Angels: a Republican regime redolent of plague in all spheres, when our queer sisters, brothers, and not-cis-ters lived and died under the crosshairs of an Axis of Fear? Why do we—why did I—allow this play to so transform our vision and perception to the extent that it has, so that when reading Aristotle, Tolstoy, Foucault, Arendt, Hegel, Althusser, Molière, or even Shakespeare, we find ourselves cross-referencing their words with those of Mr. Kushner—our grandest litmus test?

Perhaps it is just the high-falutin’ aesthetics which Kushner so grounds to reality with alienating, vaudeville-theatrics. Perhaps it’s the hot, illicit, sometimes sadomasochistic sex in the dark shadows between men (and, yes, at one point, thank goodness, women) who would not ever, perhaps ought not to ever have met. Perhaps it’s the comedy and the camp, or perhaps it’s the drama done in drag. Perhaps it is the feeling of all the aforementioned dramatists—alongside Williams and von Horváth and Goethe and Kleist (and Baldwin and Melville) and all the rest, making theatre and love (perhaps en ensemble) in a rusty, definitely New York autumn. Perhaps it’s because of the script maintaining ubiquity without fail at any local franchise of a sole, remaining major bookstore chain. Or, perhaps, it’s the most recent “great play” written; and therefore is the one we who write plays must write against, test our theories to, and hypothesize about, in readings close and wide. It certainly taught me the powers of theatre: the revival of history; the realization of the imaginary; and the familiarization of the strange®.

We return to the text, bound by the bound book, when trying to write, hoping to smell the fog (or is that smoke?) of Kushner’s San Franciscan post-catastrophic heaven. We start again (in the right order, this time) and pray that the Angel, unlike in Kushner’s text, brings not her unwieldy barricade, but an honest-to-Goddess cure. We hope to finally find a definition of that term “Great Work,” (why has there been no complementary lecture, such as the ones Gertrude Stein delivered on the little dog which knew her?)—that revolutionary, flirtatious, and millennial phrase that ends these two Kushner companion-plays, but for which he problematically, Platonically, and pointedly provides us no positive account. We re-read to read the American Angel utter the word “moonlorn” in her climactic epistle in heaven addressed to Prior Walter, right before he descends back to Earth—and awful, wonderful, contradictory life. “Moonlorn” is a word I haven’t been able to find anywhere else, (and I’ve looked—hard,); so I am left assuming (until I’m told otherwise) that it is a neologism of Mr. Kushner’s glittering invention.

The production approaches; so will the book matter less, or will it be as it always was—not when printed and displayed upon shelf as a great work unto itself, but as a hyper-textual, meta-textual, most-dramatic text: today’s greatest work for great-work-beginning? It is a healing thing, to paraphrase Kushner’s forward to a recent translation of Sholem Aleichem’s Wandering Stars, to find oneself in the margins of a masterpiece.

I still can’t afford a copy of Angels in America—not in hardcover, at least… but copies, I have a few, from friends and lovers and stoop sales and classes; and the shelf is looking quite full of them: angels abounding.

#theatre#angels in america#tony kushner#queer literature#national theatre#essay#gay#a gay fantasia on national themes#national theatre live#playwriting#playwrights#from the archives#origin story#original writing#dramaturgy#drama#dramatists#millennium approaches#perestroika#nt-live#now now now#the great work begins#moonlorn#epistle#heaven I'm in heaven#bad news#best thing on Broadway maybe ever#more life#threshold of revelation

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Whoever relies on the Tao in governing men

doesn't try to force issues

or defeat enemies by force of arms.

For every force there is a counter force.

Violence, even well intentioned,

always rebounds upon one's self.

The Master does his job

and then stops.

He understands that the universe

is forever out of control,

and that trying to dominate events

goes against the current of the Tao.

Because he believes in himself,

he doesn't try to convince others.

Because he is content with himself,

he doesn't need others' approval.

Because he accepts himself,

the whole world accepts him.

Lao Tzu - (Tao Te Ching, chapter 30, translation by Stephen Mitchell)

There Will Be Repercussions

There were laws at work, governing our universe, long before Sir Isaac discovered them. And, while the physics textbooks give credit to Newton for discovering them, and I don’t mean to take anything away from Sir Isaac’s discovery, but long before Newton had his “Eureka!” moment (while watching an apple fall from a tree), Lao Tzu perceived the laws governing our universe, and penned his own theory. The way things are, the Tao; for every force there is a counter force.

If you are relying on the Tao in governing, you won’t try to force issues, or defeat enemies by force of arms. Violence, even if it is done with the best of intentions, always rebounds upon the one perpetrating the violence.

I appreciate Stephen Mitchell’s translation, I really do. But, it almost seems like it could have come right out of a physics textbook. Red Pine’s translation just has a more poetic feel to me.

“Use the Tao to assist your lord

don’t use weapons to rule the land

such things have repercussions

where armies camp

brambles grow

best to win then stop

don’t make use of force

win but don’t be proud

win but don’t be vain

win but don’t be cruel

win when you have no choice

this is to win without force

virility leads to old age

this isn’t the Tao

what isn’t the Tao ends early”

That sure is a lesson I wish our rulers took to heart.

President Trump wasted no time taking up the use of force where his predecessor left off. Any hopes that he was going to scale back the violence have been nipped in the bud. Will we ever learn?

SUNG CH’ANG-HSING says, “A kingdom’s ruler is like a person’s heart: when the ruler acts properly, the kingdom is at peace. When the heart works properly, the body is healthy. What enables them to work and act properly is the Tao. Hence, use nothing but the Tao to assist the ruler.”

LI HSI-CHAI, quoting MENCIUS (7B.7) says, “‘If you kill someone’s father, someone will kill your father. If you kill someone’s brother, someone will kill your brother.’ This is how things have repercussions.”

CH’ENG HSUAN-YING says, “The external use of soldiers and arms returns in the form of vengeful enemies. The internal use of poisonous thoughts come back in the form of evil rebirths.”

WANG CHEN, paraphrasing SUNTZU PINGFA (2.1), says, “To raise an army of a hundred thousand requires the daily expenditure of a thousand ounces of gold. And an army of a hundred thousand means a million refugees on the road. Also, nothing results in greater droughts, plagues, or famines than the scourge of warfare. A good general wins only when he has no choice, then stops. He dares not take anything by force.”

MENCIUS says, ‘Those who say they are great tacticians or great warriors are, in fact, great criminals.” (MENCIUS: 7B.2-3)

I really like that Mencius, dude.

LU HUI-CH’ING says, “To win means to defeat one’s enemies. To win without being arrogant about one’s power, to win without being boastful about one’s ability, to win without being cruel about one’s achievement, this sort of victory only comes from being forced and not from the exercise of force.”

SU CH’E says, “Those who possess the Tao prosper and yet seem poor. They become full and yet seem empty. What is not virile does not become old and does not die. The virile die. This is the way things are. Using an army to control the world represents the height of strength. But it only hastens old age and death.”

HO-SHANG KUNG says, “Once plants reach their height of development, they wither. Once people reach their peak, they grow old. Force does not prevail for long. It isn’t the Tao. What is withered and old cannot follow the Tao. And what cannot follow the Tao soon dies.”

WU CH’ENG says, “Those who possess the Way are like children. They come of age without growing old.”

And finally, the old Master himself, LAO-TZU says, “Tyrants never choose their death.” (Taoteching: 42)

Now back to the physics textbook, hehe. Stephen Mitchell tells us the Master understands the universe is forever out of control, that trying to dominate events goes against the current of the Tao.

We need to believe in ourselves; because, if we believed in ourselves we wouldn’t try to convince others.

We need to be content with ourselves; because, if we were content with ourselves we wouldn’t need others’ approval.

For the last couple of days we talked about accepting the world. But, Lao Tzu also told us to see the world as ourselves. So, it isn’t exactly surprising to see Stephen Mitchell ending this chapter with the need to accept ourselves. Why? The whole world will accept us.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You have seen the care with which I have followed concordance as a strategy over these past 6 years since the publication of my first book on the Scriptures, Seeing the Psalter.

I worked with the poetry of the Psalms first. Among my first works with the prose was the book of Ruth. So here I will compare the English of three versions.

Have I written English in my work? This is a question I have worried about. Reading and studying a foreign tongue twists ones own in unpredictable ways. Consider the language of Yoda in the Star Wars films. Sometimes I even followed Dr. Seuss as my model. (My tongue is in my cheek.)

But seriously, I am also supposed to be paying attention to the music. To be fair, I don't always try to underlay the text. I would be working for several more years to do this. But we have all the music available. So there's nothing to stop you all from doing this. Or from reading my close translation for the music.

Here are, line by line, Alter, NRSV, and Bob with music for Ruth 2:3 to 7. And each musical line shows the Hebrew, the pulse, and the cadences and ornaments. I do not know who invented these hand-signals but they are fantastically good for the text which itself is so dearly loved. It would be a shame to get it wrong. And they are much more accurate as to tone and rhythm than any abstract poetical concepts.

I am taking my information from the section of the review of Alter's translation by Adele Berlin, whose presentation skill I greatly admire.

I have put the line breaks where the cadence on the subdominant is in the music. This is a fascinating comparison. One can see the loves and fears about English in each translation. One can also see the rhythmic limitations of the English immediately.

Verse 3

A. And she went and came and gleaned in the field behind the reapers,

N. So she went. She came and gleaned in the field behind the reapers.

B. And she went, and she came, and she gleaned in the field, following the reapers.

Ruth 2:3 showing the pulse and cadence of the Hebrew text

Both Alter and NRSV miss the pulse of the first part of the verse. The musical notes give an accurate representation of the syllables if you are in to counting.