#1.2.3

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Round 1 Stage 2 Poll 3

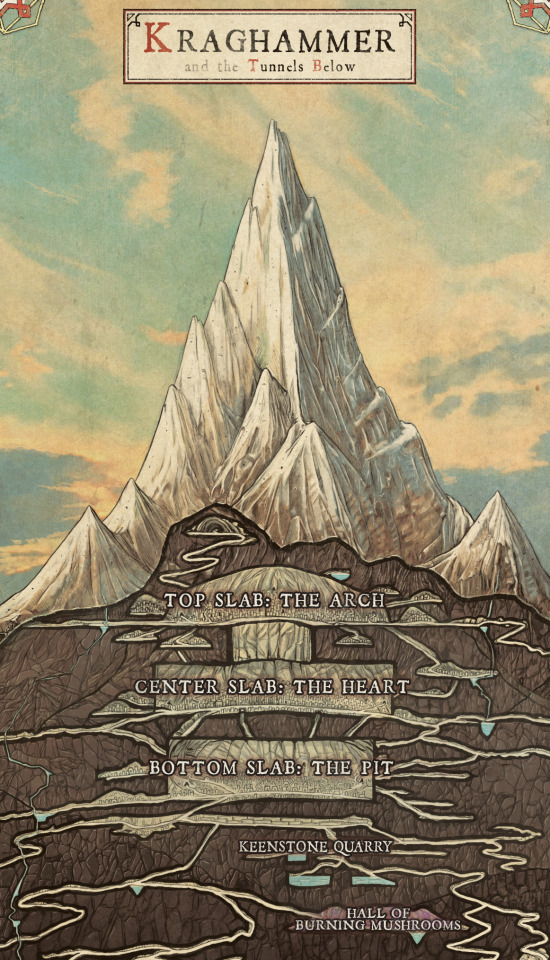

Kraghammer, Tal'Dorei: Kraghammer is a dwarven city in the Republic of Tal'Dorei. It was a short stop on Vox Machina's journey to the Underdark, but it is where the first streams of Campaign 1 began.

image by andy law from tal'dorei campaign setting reborn

Jigow, Wildemount: Jigow is a Kryn Dynasty city in northern Xhorhas. It has only been mentioned in passing onstream, but it is a key location in Call of the Netherdeep.

image is official art by max dunbar from call of the netherdeep

#exandria#kraghammer#jigow#tal'dorei#wildemount#taldorei#critical role#poll post#notpollprop#exandria city showdown#round 1#1.2.3

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mise à jour de l'expédition 33 1.2.3 : Nerf de Maelle Stendhal et changements clés en direct maintenant

Exploration de l’impact culturel et des dernières mises à jour de Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 Depuis son lancement il y a quelques semaines, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 a captivé les joueurs et a eu un impact culturel significatif au sein de la communauté des jeux vidéo. Les joueurs se sont précipités en ligne pour partager leurs expériences et plonger dans le récit immersif du jeu. Mécaniques…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Blizzard спешит исправить сломанный опыт глифов из патча 1.2.3

New Post has been published on https://dark4web.com/blizzard-speshit-ispravit-slomannyj-opyt-glifov-iz-patcha-1-2-3/

Blizzard спешит исправить сломанный опыт глифов из патча 1.2.3

Диабло 4последнее обновление вышла в свет 5 декабря. В нее добавлено новое испытание в вершинных подземельях финальной игры, в котором…

#1.2.3#Blizzard#Diablo#GameStop#RPG#Windows XP#Windows-игры#Адам Флетчер#Амазонка#Выпуск программного обеспечения#Глиф#глифов#Игры метели#из#Инфографика#исправить#исправление#Котаку#Лучшая покупка#Майкрософт#Обслуживание программного обеспечения#опыт#патча#Пластырь#Сломанный#Совершенный глиф#Сони#спешит

0 notes

Text

Jean Valjean’s horrible awful relationship with religion is really fascinating— the way religion becomes deeply meaningful to his life but is also still a tool of social control that is used to violently oppress him. I love this line where he describes how bishops would “preach” to him in the galleys:

“[the bishop] said mass in the middle of the galleys, on an altar. He had a pointed thing, made of gold, on his head; it glittered in the bright light of midday. We were all ranged in lines on the three sides, with cannons with lighted matches facing us. We could not see very well. He spoke; but he was too far off, and we did not hear. That is what a bishop is like.”

Jean Valjean’s early relationship with religion is as this horrible violent obligation. He attends “mass” in the galleys, where cannons are pointed at him, so that if anyone in the crowd acts up they can all be massacred. The bishop is also so impossibly distant that they can’t even hear him. No one in prison is trying to actually speak to Jean Valjean or the other convicts; they’re just violently forcing them to act out the empty forms of Christianity while not allowing them to truly participate in it.

And while Myriel does change his life, and his faith…. Jean Valjean never fully internalizes the way Myriel treated him as an equal and insisted that they were brothers. And that’s in large part because of the hostility or terror which which the rest of the Church and society views him.

We’re told later that in the convent, Jean Valjean prays to the nuns doing penance, because “he did not dare to pray directly to God.”

There’s a fascinating tension between the fact that religion is extremely important to Jean Valjean’s life, but also, that same religion is often used against him as a tool of violent social control. He belongs to a religion that rejects him violently. He prays to a God that he does not dare to pray to directly, out of self-loathing. It’s a really strange complex relationship.

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Took me a while but! Canine imagery in volume 1 book 2 of Les Mis!

Similarly to book one, wolf imagery in book two is used to represent a character’s dangerous and violent intentions and/or their relationship to society. When contrasted with dogs in Les Mis, wolf imagery is used to show the ways certain people are prohibited from being part of normal society, usually because they’re in extreme poverty or are a criminal. A dog is a domestic canine who is allowed to participate in human society and a wolf is a wild animal who isn’t.

In Valjean’s case, Hugo describes in 1.2.7 the process by which he is transformed from a man into a wolf through the abuse inflicted on him by the prison system.

The peculiarity of pains of this nature, in which that which is pitiless—that is to say, that which is brutalizing—predominates, is to transform a man, little by little, by a sort of stupid transfiguration, into a wild beast; sometimes into a ferocious beast.

He escaped impetuously, like the wolf who finds his cage open. Instinct said to him, “Flee!” Reason would have said, “Remain!” But in the presence of so violent a temptation, reason vanished; nothing remained but instinct. The beast alone acted.

I think both of the uses of Hugo’s wolf metaphor I mentioned above are relevant to Valjean’s time in prison - his personhood and his place in society have been stripped from him and his trauma and mistreatment have turned him from a rational man into an angry, scared, impulsive and dangerous wolf. Hugo already explains his metaphor pretty thoroughly in this chapter so I don’t think I really need to say much more here but these few paragraphs always really stick with me. Les Mis is just begging for werewolf aus I stg

Dog imagery also makes its first appearance in book 2💖‼️ Throughout Les Mis dogs are Javert’s Main Symbolic Animal, and they’re also associated with the police and law enforcement on a wider scale as the ‘guard dogs’ of society and social order. Even though Javert doesn’t show up as a character until book five I personally read a lot of the canine imagery in book two as foreshadowing for his relationship with Madeleine in Montreuil-sur-Mer.

The first appearance of dog imagery is in chapter 1.2.1 and involves Valjean meeting a real non-metaphorical dog when he arrives in Digne. After all the local inns have rejected him because of his yellow passport, Valjean tries to sleep in a dog’s kennel but is chased off by the dog who lives there.

Chased even from that bed of straw and from that miserable kennel, he dropped rather than seated himself on a stone, and it appears that a passer-by heard him exclaim, “I am not even a dog!”

If dogs in Les Mis represent people like Javert who are allowed to participate in human society without being fully part of it, Valjean not even attaining the social status of ‘dog’ shows how completely he has been rejected by the people of Digne and how his status as an ex-convict prevents him from being able to participate in society in a normal way.

The first time I believe the dog symbolism is actually foreshadowing Javert’s arrival is two chapters later in 1.2.3 when Valjean recounts his experience with the dog to Myriel:

I went into a dog’s kennel; the dog bit me and chased me off, as though he had been a man. One would have said that he knew who I was.

When we meet him in book five, Javert is the dog who knows who Valjean really is.

Dogs show up again one more time in chapter 1.2.11 when Valjean tries to sneak into the bishop’s room at night. A hinge squeaks loudly as he tries to open the door and Valjean imagines that the sound is a barking dog who has come to warn everyone of his presence.

In the fantastic exaggerations of the first moment he almost imagined that that hinge had just become animated, and had suddenly assumed a terrible life, and that it was barking like a dog to arouse every one, and warn and to wake those who were asleep.

I think this can be read as foreshadowing for his future interactions with Javert too, but it also shows how jumpy and on edge he is after his time in prison, and how much he’s expecting to be caught again (even though he hasn’t actually done anything wrong yet!) just like he was caught and punished every time he attempted to escape from Toulon. Either way, I’m pretty sure this is the last of the canine imagery in book two.

#the true message of les mis is that ptsd gives you cool werewolf powers#jean valjean#javert#les mis letters#lm 1.2.11#lm 1.2.7#lm 1.2.3#lm 1.2.1#monsters of our making#fave posts tag

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2, Matchup 10: I.ii.3 vs V.i.23

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I started rereading les mis, in french this time, and I'm sort of catching up to les mis letters (only sort of, for now, since I'm still at chapter 1.2.5 I think) and I do wanna talk about the title of the book because that title has fascinated me ever since I opened that book 14 years ago in its greek translation. So the greek translation of the title "les Misérables" mystified me. I think a big part of western languages have a variation of the word "misérable" in their vocabulary so the translation of the title is pretty much consistent (obviously not every western language, idk what happens with scandinavian translations or hungarian or russian for example). In greek we do not have the word "miserable" or "misery", we kind of use the word "mizeria" but only as a "western" variation of the greek word we have for misery, so we don't have the equivalent adjective. So the original greek translator needed to find a brand new adjective, in greek, to convey the meaning of the title, and honestly, what a task that is, finding the greek equivalent of probably the most iconic title in literature ever, just one word to encapsulate 1500 pages of text.

The word finally used is "Άθλιοι" (Athlioi) the plural form of "Athlios". It's an ancient greek word that is also commonly used in modern greek as is the case for a huge part of our vocabulary. So the ancient greek definition of "Athlioi" is "struggling, unhappy, wretched, miserable". In modern greek, the definition is more or less the same: "seedy, miserable, poor, terrible", except for the last word "terrible" that has an interesting connotation. The definition of "Athlioi" as terrible is an addition of modern greek. "Terrible" by itself maybe doesn't say much and it seems as a mere variation of the classic definition of Athlioi as "miserable, poor, wretched" etc. But from miserable and wretched to terrible there is an interesting leap. While "seedy, miserable, poor, terrible" are the english translations of the greek word "Athlioi" that I find on wordreference.com, I get very interesting results when I inverse the search, this time searching for the greek translation of the following english words (on wordreference or glosbe): despicable, nasty, vile, shady, appaling, loathsome, wicked, infamous, monstrous, horrible, lame, shabby, mangy, mean, vicious. You may have guessed it, all of the above are translated into "Athlios" in greek (among other words). The reason for that is that "Athlios" in modern greek has an extremely negative connotation. An "athlios" is not just a miserable wretched poor outcast. An "athlios" is a despicable human being, one that inspires disgust, one you should avoid in any case. A horrendous, vile, monstrous, hateful, creature. I am not sure if the word "Athlios" already had that definition at the time of the first greek translation (end of 19th century) but my bet is that it did, because that is what the word is primarily used for in Greece ever since I remember myself. When we use the word "Athlios" in greek now we rarely if ever talk about someone "miserable", "poor" or "wretched". We normally talk about someone or something despicable. If it's a person, 99% of the time this has a purely moral connotation aka, someone who is morally despicable. They could be a poor person, (a Thenardier type of vile individual) or they could be rich, doesn't matter really.

I am not sure if the word "misérable" or the english word "miserable" have this connotation. It is one thing to be wretched and totally another thing to be despicable and loathsome. Is this very close to the french word "misérable"? "Misérable" in french primarily means "pitiful, wretched", with one mention of "despicable", it is true. In Larousse however (the classic french dictionary) I cannot find one definition of "misérable" with the "vile, despicable" connotation that the word "Athlios" has. I am sure "misérable" can be used that way, and it can be translated that way in english, but vile and despicable are not the leading definition one thinks about when they encounter the word. When we use the word "misérable"/miserable, we normally do not immediately think of a despicable, vile, loathsome individual. So this choice of title by the greek translator takes some liberties. He could have used our greek word for "pitiful", "outcast" or one particular greek word we have for "scorned" that has a particular depth because it means scorned, neglected and forgotten by society all at the same time. Or he could have went for our word for "miserable" in the sense of "unhappy". All of these could have worked well enough. But he went for "Athlioi". Why? Athlioi is the only word that has a truly negative connotation for the morality of a person, of their moral value, and the way society percieves that moral value.

I got to the chapter "The Evening of a Day of Walking" where Valjean makes his first appearence. The english translation is this:

"It was difficult to encounter a wayfarer of more wretched appearance".

Then Hugo proceeds with a description of his appearance that is particularly unsettling, to say the least. He was literally dressed in rags with iron-shod shoes and he had holes in his clothes. At the end of the description he says:

"The sweat, the heat, the journey on foot, the dust, added I know not what sordid quality to this dilapidated whole".

So that guy is 1) certainly unhappy, 2) clearly wretched, 3) has a sordid quality and 4) a dilapidated look.

It is interesting that in french, the phrase "wretched appearance" is actually "aspect misérable". It is important to note this because this is the first time that the author gives us a description of a character that encapsulates what a "Misérable" according to the title actually is. Moving along, Valjean is not accepted in any inn or house and the people force him to leave because they are horrified by 1) his appearance and mainly 2) his profile as an ex convict that makes him a "Dangerous Man". "Dangerous Man" is literally written on his passport. A pitiful creature is maybe not that loathsome by itself, but a "Dangerous Man" is definitely something that you want to stay away from.

At the chapter "The Heroism of Passive Obedience" (1.2.3) Valjean enters the bishop's house and the bishop's sister sees him and describes him like this:

"He was hideous. It was a sinister apparition."

"Mademoiselle Baptistine turned round, beheld the man entering, and half started up in terror".

"Wretched" and "pitiful" cannot cover the impact this individual had on people, on society. That man was not just deeply unhappy, in a deplorable state, wretched and pitiful. That man was appaling. That man was loathsome. That man inspired horror, disgust, and intense, bone deep hatred. It is important to note this aspect of "misérable". The fear society has for the injustice it creates is so strong that it is far easier to dehumanize these individuals by slapping the label of "despicable", "vile", "loathsome" on them. It makes their total marginalisation easier because it justifies it. People are truly disgusted by and terrorised by Valjean. For society, there is a reason why that man is in a pathetic, deplorable, "miserable" state. It's because he is truly, irrevocably, morally hideous, loathsome and nasty. He is "dangerous". He truly is a monster inside out. And that particular manifestation of social misery is nicely conveyed by the word "Athlios" in my opinion.

#les miserables#aspa reads les mis#jean valjean#les mis letters#catching up#les mis translations#lm 1.2.3#lm 1.2.1#les misérables#aspa rambles#long post#the brick

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey, les mis tumblr, can you help me out? i'm a little behind on les mis letters so im reading 1.2.3 right now, and i was wondering how much one hundred and nine francs and fifteen sous would be in USD, and approximately like. how much it is in general terms of, what it would've gotten you at the time and the equivalent today?

i imagine it's not very much at all, but i am interested to know the specific details of it.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

LES MIS LETTERS IN ADAPTATION - The Heroism of Passive Obedience, LM 1.2.3 (Les Miserables 1934)

The door opened. It opened wide with a rapid movement, as though some one had given it an energetic and resolute push. A man entered. We already know the man. It was the wayfarer whom we have seen wandering about in search of shelter. He entered, advanced a step, and halted, leaving the door open behind him. He had his knapsack on his shoulders, his cudgel in his hand, a rough, audacious, weary, and violent expression in his eyes. The fire on the hearth lighted him up. He was hideous. It was a sinister apparition.

#Les Mis#Les Miserables#Les Mis Letters#Les Mis Letters in Adaptation#Les Mis 1934#Les Miserables 1934#Jean Valjean#Valjean#Harry Baur#pureanonedits#lesmisedit#lesmiserablesedit#lesmis1934edit#lesmiserables1934edit#T_T#;w;#LM 1.2.3#Truly Baur is one of if not the most Unbearably Sad Beast Valjeans.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Heroism Of Passive Obedience

Les Mis Letters reading club explores one chapter of Les Misérables every day. Join us on Discord, Substack - or share your thoughts right here on tumblr - today's tag is #lm 1.2.3

The door opened.

It opened wide with a rapid movement, as though some one had given it an energetic and resolute push.

A man entered.

We already know the man. It was the wayfarer whom we have seen wandering about in search of shelter.

He entered, advanced a step, and halted, leaving the door open behind him. He had his knapsack on his shoulders, his cudgel in his hand, a rough, audacious, weary, and violent expression in his eyes. The fire on the hearth lighted him up. He was hideous. It was a sinister apparition.

Madame Magloire had not even the strength to utter a cry. She trembled, and stood with her mouth wide open.

Mademoiselle Baptistine turned round, beheld the man entering, and half started up in terror; then, turning her head by degrees towards the fireplace again, she began to observe her brother, and her face became once more profoundly calm and serene.

The Bishop fixed a tranquil eye on the man.

As he opened his mouth, doubtless to ask the newcomer what he desired, the man rested both hands on his staff, directed his gaze at the old man and the two women, and without waiting for the Bishop to speak, he said, in a loud voice:—

“See here. My name is Jean Valjean. I am a convict from the galleys. I have passed nineteen years in the galleys. I was liberated four days ago, and am on my way to Pontarlier, which is my destination. I have been walking for four days since I left Toulon. I have travelled a dozen leagues to-day on foot. This evening, when I arrived in these parts, I went to an inn, and they turned me out, because of my yellow passport, which I had shown at the town-hall. I had to do it. I went to an inn. They said to me, ‘Be off,’ at both places. No one would take me. I went to the prison; the jailer would not admit me. I went into a dog’s kennel; the dog bit me and chased me off, as though he had been a man. One would have said that he knew who I was. I went into the fields, intending to sleep in the open air, beneath the stars. There were no stars. I thought it was going to rain, and I re-entered the town, to seek the recess of a doorway. Yonder, in the square, I meant to sleep on a stone bench. A good woman pointed out your house to me, and said to me, ‘Knock there!’ I have knocked. What is this place? Do you keep an inn? I have money—savings. One hundred and nine francs fifteen sous, which I earned in the galleys by my labor, in the course of nineteen years. I will pay. What is that to me? I have money. I am very weary; twelve leagues on foot; I am very hungry. Are you willing that I should remain?”

“Madame Magloire,” said the Bishop, “you will set another place.”

The man advanced three paces, and approached the lamp which was on the table. “Stop,” he resumed, as though he had not quite understood; “that’s not it. Did you hear? I am a galley-slave; a convict. I come from the galleys.” He drew from his pocket a large sheet of yellow paper, which he unfolded. “Here’s my passport. Yellow, as you see. This serves to expel me from every place where I go. Will you read it? I know how to read. I learned in the galleys. There is a school there for those who choose to learn. Hold, this is what they put on this passport: ‘Jean Valjean, discharged convict, native of’—that is nothing to you—‘has been nineteen years in the galleys: five years for house-breaking and burglary; fourteen years for having attempted to escape on four occasions. He is a very dangerous man.’ There! Every one has cast me out. Are you willing to receive me? Is this an inn? Will you give me something to eat and a bed? Have you a stable?”

“Madame Magloire,” said the Bishop, “you will put white sheets on the bed in the alcove.” We have already explained the character of the two women’s obedience.

Madame Magloire retired to execute these orders.

The Bishop turned to the man.

“Sit down, sir, and warm yourself. We are going to sup in a few moments, and your bed will be prepared while you are supping.”

At this point the man suddenly comprehended. The expression of his face, up to that time sombre and harsh, bore the imprint of stupefaction, of doubt, of joy, and became extraordinary. He began stammering like a crazy man:—

“Really? What! You will keep me? You do not drive me forth? A convict! You call me <i>sir!</i> You do not address me as <i>thou?</i> ‘Get out of here, you dog!’ is what people always say to me. I felt sure that you would expel me, so I told you at once who I am. Oh, what a good woman that was who directed me hither! I am going to sup! A bed with a mattress and sheets, like the rest of the world! a bed! It is nineteen years since I have slept in a bed! You actually do not want me to go! You are good people. Besides, I have money. I will pay well. Pardon me, monsieur the inn-keeper, but what is your name? I will pay anything you ask. You are a fine man. You are an inn-keeper, are you not?”

“I am,” replied the Bishop, “a priest who lives here.”

“A priest!” said the man. “Oh, what a fine priest! Then you are not going to demand any money of me? You are the curé, are you not? the curé of this big church? Well! I am a fool, truly! I had not perceived your skull-cap.”

As he spoke, he deposited his knapsack and his cudgel in a corner, replaced his passport in his pocket, and seated himself. Mademoiselle Baptistine gazed mildly at him. He continued:

“You are humane, Monsieur le Curé; you have not scorned me. A good priest is a very good thing. Then you do not require me to pay?”

“No,” said the Bishop; “keep your money. How much have you? Did you not tell me one hundred and nine francs?”

“And fifteen sous,” added the man.

“One hundred and nine francs fifteen sous. And how long did it take you to earn that?”

“Nineteen years.”

“Nineteen years!”

The Bishop sighed deeply.

The man continued: “I have still the whole of my money. In four days I have spent only twenty-five sous, which I earned by helping unload some wagons at Grasse. Since you are an abbé, I will tell you that we had a chaplain in the galleys. And one day I saw a bishop there. Monseigneur is what they call him. He was the Bishop of Majore at Marseilles. He is the curé who rules over the other curés, you understand. Pardon me, I say that very badly; but it is such a far-off thing to me! You understand what we are! He said mass in the middle of the galleys, on an altar. He had a pointed thing, made of gold, on his head; it glittered in the bright light of midday. We were all ranged in lines on the three sides, with cannons with lighted matches facing us. We could not see very well. He spoke; but he was too far off, and we did not hear. That is what a bishop is like.”

While he was speaking, the Bishop had gone and shut the door, which had remained wide open.

Madame Magloire returned. She brought a silver fork and spoon, which she placed on the table.

“Madame Magloire,” said the Bishop, “place those things as near the fire as possible.” And turning to his guest: “The night wind is harsh on the Alps. You must be cold, sir.”

Each time that he uttered the word <i>sir</i>, in his voice which was so gently grave and polished, the man’s face lighted up. <i>Monsieur</i> to a convict is like a glass of water to one of the shipwrecked of the <i>Medusa</i>. Ignominy thirsts for consideration.

“This lamp gives a very bad light,” said the Bishop.

Madame Magloire understood him, and went to get the two silver candlesticks from the chimney-piece in Monseigneur’s bed-chamber, and placed them, lighted, on the table.

“Monsieur le Curé,” said the man, “you are good; you do not despise me. You receive me into your house. You light your candles for me. Yet I have not concealed from you whence I come and that I am an unfortunate man.”

The Bishop, who was sitting close to him, gently touched his hand. “You could not help telling me who you were. This is not my house; it is the house of Jesus Christ. This door does not demand of him who enters whether he has a name, but whether he has a grief. You suffer, you are hungry and thirsty; you are welcome. And do not thank me; do not say that I receive you in my house. No one is at home here, except the man who needs a refuge. I say to you, who are passing by, that you are much more at home here than I am myself. Everything here is yours. What need have I to know your name? Besides, before you told me you had one which I knew.”

The man opened his eyes in astonishment.

“Really? You knew what I was called?”

“Yes,” replied the Bishop, “you are called my brother.”

“Stop, Monsieur le Curé,” exclaimed the man. “I was very hungry when I entered here; but you are so good, that I no longer know what has happened to me.”

The Bishop looked at him, and said,—

“You have suffered much?”

“Oh, the red coat, the ball on the ankle, a plank to sleep on, heat, cold, toil, the convicts, the thrashings, the double chain for nothing, the cell for one word; even sick and in bed, still the chain! Dogs, dogs are happier! Nineteen years! I am forty-six. Now there is the yellow passport. That is what it is like.”

“Yes,” resumed the Bishop, “you have come from a very sad place. Listen. There will be more joy in heaven over the tear-bathed face of a repentant sinner than over the white robes of a hundred just men. If you emerge from that sad place with thoughts of hatred and of wrath against mankind, you are deserving of pity; if you emerge with thoughts of good-will and of peace, you are more worthy than any one of us.”

In the meantime, Madame Magloire had served supper: soup, made with water, oil, bread, and salt; a little bacon, a bit of mutton, figs, a fresh cheese, and a large loaf of rye bread. She had, of her own accord, added to the Bishop’s ordinary fare a bottle of his old Mauves wine.

The Bishop’s face at once assumed that expression of gayety which is peculiar to hospitable natures. “To table!” he cried vivaciously. As was his custom when a stranger supped with him, he made the man sit on his right. Mademoiselle Baptistine, perfectly peaceable and natural, took her seat at his left.

The Bishop asked a blessing; then helped the soup himself, according to his custom. The man began to eat with avidity.

All at once the Bishop said: “It strikes me there is something missing on this table.”

Madame Magloire had, in fact, only placed the three sets of forks and spoons which were absolutely necessary. Now, it was the usage of the house, when the Bishop had any one to supper, to lay out the whole six sets of silver on the table-cloth—an innocent ostentation. This graceful semblance of luxury was a kind of child’s play, which was full of charm in that gentle and severe household, which raised poverty into dignity.

Madame Magloire understood the remark, went out without saying a word, and a moment later the three sets of silver forks and spoons demanded by the Bishop were glittering upon the cloth, symmetrically arranged before the three persons seated at the table.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

And olsun səhərə! And olsun sakitləşməkdə olan gecəyə! Rəbbin səni nə tərk etdi, nə də sənə darıldı.🌙

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

This chapter is both heartwarming and heart-wrenching. It portrays the first instance of a life-changing act of kindness (the second one is that of Marius towards Éponine, and the third one is that of Jean Valjean towards Javert).

Valjean’s anger and honesty at the moment he enters the house is heart-breaking. By that point, he is desperate and humiliated. Having just learned that lies can serve him better than the truth (a wisdom he will utilize time and again in the future), he still chooses to be rudely sincere. This is similar to what he will do at the end, revealing the truth about himself to Marius. In both cases, he chooses not to disclose mitigating circumstances. Why is he like this?

It’s touching how Valjean is surprised and moved by every detail of the bishop’s attitude toward him. "You are letting me in?! You are addressing me 'vous'?! You let me sleep in a bed?! You are not asking for money?!"

Valjean’s description of his experience at the galleys brings me to tears: “Oh, the red coat, the ball on the ankle, a plank to sleep on, heat, cold, toil, the convicts, the thrashings, the double chain for nothing, the cell for one word; even sick and in bed, still the chain! Dogs, dogs are happier! Nineteen years! I am forty-six. Now there is the yellow passport. That is what it is like.”

Each time I read about Bishop Myriel asking Mme Magloire to put a silver set on the table, I think that it seems he is doing this to seduce Valjean. Of course, this is out of his character, and he most probably wanted to show his respect and welcome to the guest. Still, it is a very bothering act.

And, of course, it was important for Hugo to provide the contrast between Bishop Myriel and some random bishop seen by Valjean during his imprisonment. He doesn’t even know that his host is not just a priest but a bishop, yet he still recalls his encounter with a distant and glittering prince of the Church. “That is what a bishop is like,” concludes he.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Сегодняшние примечания к обновлению 1.2.3 для Diablo 4 увеличивают прирост опыта за эндгейм-гринд Glyph.

New Post has been published on https://dark4web.com/segodnyashnie-primechaniya-k-obnovleniyu-1-2-3-dlya-diablo-4-uvelichivayut-prirost-opyta-za-endgejm-grind-glyph/

Сегодняшние примечания к обновлению 1.2.3 для Diablo 4 увеличивают прирост опыта за эндгейм-гринд Glyph.

Video Gamer поддерживается читателями. Когда вы совершаете покупки по ссылкам на нашем сайте, мы можем получать партнерскую комиссию. Цены могут…

0 notes

Text

Shinichi Atobe - Rebuild Mix 1.2.3.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

when your chem teacher leaves you one (1) sheet of review for your whole ass unit test so now you're scouring the internet for information on emission spectra feeling like a little russian orphan boy in the 1910s

#school#international baccalaureate#chemistry#so yeah if anyone has review notes for IB chem HL 11#structures 1.2.3-1.3.2#that would be excellent thank you

6 notes

·

View notes