#1770s britain

Text

Purple Silk Robe à la Française, 1770-1775, English.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#purple#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#1770#1770s#1770s dress#1770s extant garment#1770s England#1770s Britain#robe à la française#v&a#English#British

264 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So this is gonna sound weird, but I’ve kinda been learning about Irish history backwards? Like, I started with the Troubles (bc of family involvement), then back to the 1916 rising which got me more interested in the people involved which took me further back and etc etc. I know I’ve been doing it “wrong” but I’m just starting to come up to the 1798. Do you happen to have any recommended readings or particular persons of interest to read? Any collections of primary sources would be more than welcome!

Secondary sources I would recommend:

The Year of Liberty by Thomas Pakenham - about the rebellion in general

The People's Rising by Daniel Gahan - about the rebellion in Wexford

The Summer Soldiers by ATQ Stewart - about the rebellion in Ulster

Wolfe Tone: Prophet of Irish Independence by Marianne Elliott - about Wolfe Tone

The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken by Mary McNeill - technically this is just about Mary Ann but I think it's pretty good for Henry Joy McCracken too because there aren't many biographies of him

Orangeism in Ireland and Britain 1795 - 1836 by Hereward Senior - obviously exercise caution on whether or not you think you can mentally handle this subject but book about loyalism during 1798

Castlereagh: War, Enlightenment, and Tyranny by John Bew - about Lord Castlereagh

2 things that I would also recommend reading about for context are the French Revolution and the British radical movement of the late 18th century. for the French Revolution 1 book I would say is good is Liberty or Death by Peter McPhee and for the British radical movement... the book The English Jacobins by Carl B Cone does a good enough job

Primary sources:

The Memoirs of Theobald Wolfe Tone by Theobald Wolfe Tone - title is pretty self explanatory. It's Tone's account of his own life + his diary

The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times by RR Madden - this is considered to be the 1st history of the rising & was written with the help of many people who lived through it, so it includes a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. beware that Madden was your archetypical mid 19th century Catholic Irish nationalist and the bias created due to that shows through in every single part of these books

Memoirs of the different Rebellions in Ireland by Sir Richard Musgrave - this is another very early history of the rising, also written with the help of people who lived through, also including a lot of first hand accounts. HOWEVER. Musgrave is like Madden's Orange counterpart in that this book is also wildly biased and should also be read with a degree of caution

Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, Sequel to Personal Narrative of the "Irish Rebellion" of 1798, and History and Consequences of the Battle of the Diamond by Charles Hamilton Teeling - 3 accounts of politics in Ireland in the 1790s written by someone who as a young man led the Catholic paramilitary the Defenders

The Drennan letters (a collection of letters that Belfast doctor William Drennan and his sister, Martha McTier, wrote to each other between the 1770s and 1820s), if you can find them, are another great primary source on both the United Irishmen & on what life was like back then in general, as are the McCracken letters, which I know are available free online somewhere I just can't remember where exactly I got the pdf from

There are a lot of them but if you're interested in primary sources you might also read some of the political pamphlets/books that were going around back then -- the most famous that come to mind in this context are Wolfe Tone's Argument on Behalf of the Catholics in Ireland, Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man, and Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France but there are wayyy more than that and at least some of them are on the internet archive

194 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weapons in the American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was a long and bitter conflict fought between Great Britain and its thirteen North American colonies over the Americans' liberties and, eventually, for the independence of the United States. The war, which was fought with both conventional linear tactics and guerilla-style warfare, utilized several different kinds of weapons for multiple styles of combat.

Some of the weapons used in the Revolutionary War had long been staples of European-style warfare. Variations of the flintlock musket, for instance, had been used in battle since the early 1600s and would continue to be used on Western battlefields for decades after the American Revolution had ended. Other weapons, like the groove-barreled Long Rifle, were relatively new additions to warfare; the rifle, used in a limited capacity during the Revolution, would see greater use on the later battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) and American Civil War (1861-1865). Some weapons were useful in close-quarter combat such as the bayonet, tomahawk, and saber, while artillery guns were devastating at both long and short distances. None of the weapons discussed in this article were unique to the American Revolution. However, a quick description of the types of weapons used in that conflict could help give the reader a better understanding of what it may have been like to be on a battlefield during the US War of Independence.

Flintlock Muskets

The flintlock musket was the primary weapon of 18th-century European armies and was therefore used by both sides during the American Revolution. A musket was a muzzle-loading, smoothbore weapon that fired a large lead ball with reasonably decent accuracy. By the 1770s, a typical musket weighed about 10 lbs (4.5 kg), was about 5 ft (152 cm) in length, and had a caliber of about .75 (1.9 cm). A typical lead ball weighed about an ounce (28 g). As the name 'flintlock musket' suggests, such weapons relied on a flintlock mechanism to fire. This involved a piece of flint contained within the musket's cock, or hammer. When the trigger was pulled, the hammer would swing forward, causing the flint to strike a piece of steel called the 'frizzen'. This action created a spark that would fall into a flash pan below, wherein a small charge of black powder was contained. The spark would ignite the powder, which would, in turn, discharge the bullet from the gun barrel. By the time of the revolution, flintlocks had long been the most common kind of firearm; the flintlock had been developed in France in the early 1600s to replace the earlier matchlock and wheellock mechanisms and would remain in use until the mid-19th century.

Although the process of firing a flintlock musket sounds complicated on paper, a well-trained 18th-century soldier could typically fire three or four shots per minute. This is quite impressive, especially after considering what the loading process entails. A soldier would first take a pre-rolled musket cartridge – a paper tube containing gunpowder and a lead musket ball – and tear it open with his teeth. He would then pour a small amount of the powder into the flash pan and pour the rest down the muzzle. Next, the soldier would use a ramrod to pack the musket ball, powder, and paper of the cartridge down into the breech. Only after returning the ramrod to its place and fully cocking back the hammer was the soldier finally ready to take aim and fire.

The musket could be effectively fired from a range of about 80 yards (73 m); while it could sometimes be effective at a slightly greater range, musket balls rarely traveled more than 150 yards (137 m). The musket's accuracy largely depended, of course, on the man who wielded it. To increase the effectiveness of the weapon, 18th-century armies adopted the style of linear warfare; an individual musketeer was less likely to inflict damage than a line of soldiers firing coordinated, concentrated volleys. A typical battle line consisted of two or three ranks of soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder, with each man allowed just enough space to be able to present arms, fire, and reload. When the officer gave the order, the line of soldiers would fire in sync with one another (referred to as a musket volley); sometimes the first rank would kneel to give the second rank a better shot, thereby keeping up a higher rate of fire.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

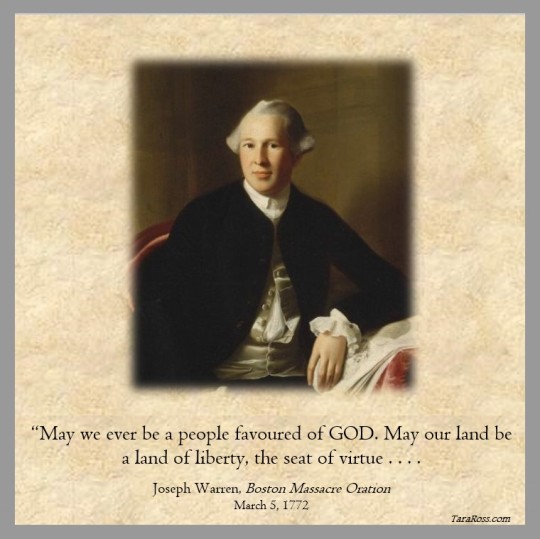

This Day in History: Boston Massacre Orations

On this day in 1770, tensions between British soldiers and American colonists erupt. British soldiers fire into a crowd in an event that came to be known as the Boston Massacre.

For the next several years, an oration was given on the anniversary of that terrible tragedy. Speakers commemorated the event—but also urged their fellow colonists to action.

War against Great Britain loomed.

“If you, with united zeal and fortitude, oppose the torrent of oppression,” Joseph Warren asserted in his 1772 oration, “if you feel the true fire of patriotism burning in your breasts . . . you may have the fullest assurance that tyranny, with her whole accursed train, will hide their hideous heads in confusion, shame and despair.”

The story continues here: https://www.taraross.com/post/tdih-boston-massacre-orations

#tdih#otd#this day in history#history#history blog#America#American Revolution#religion#sharethehistory

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vails

I haven't actually talked about it here a lot, partly because I try not to do heavy history stuff here - this blog is meant to be a hobby, after all - and it's something I'm frankly too passionate (obsessed) about, but my main area of historic interest and focus, especially when it comes to my own personal research, is the history of domestic service. It is not an exaggeration to say it is my life's work.

Another reason I don't write about it often is I don't really know where to start. My breadth of knowledge on the subject is quite broad, so there's a lot I could say, but I think I'll try to write some small things about specific aspects of it.

Vails were, in the 18th (and I believe also 19th) century, basically what we could today call tips, often paid to servants. And when you read things written by the 'master class' of people being served, while they're obviously biased and exaggerating, it does become clear that servants rather enforced them. There wasn't a guild system for servants like there were for trades, but there were informal clubs and groups, and this is one of the ways they seem to have acted together, almost as a form of unionization. There's a letter to a British newspaper where the write says that he estimates many servants are doubling, tripling, or even quadrupling their annual salaries through vails. I could write more but I'll just transcribe some of my favourite passages on this subject from the book Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland by Patricia McCarthy:

I will add too, while this is specifically talking about paid servants in Britain, you do see vails paid to enslaved people in America as well. Probably not as often, but Philip Vickers Fithian, who wrote a diary about his experiences in Virginia in the 1770s, writes about similar things of the enslaved people at the plantation he's staying at expecting their "Christmas boxes" of vails, although they weren't quite as beholden to the actual date of Boxing Day.

...

The customary scene in the hall, as their guests waited for their carriages or horses to be brought to the door, embarrassed many. [Marshall, Domestic Servants] Hosts feigned ignorance of their guests' fumbling in their pockets to find shillings and half-crowns to distribute to the servants, who had lined themselves up expectantly. Whether the motive for allowing the practice was to salve the collective conscience of the employers at paying such low wages is not clear. [Bridget Hill, Servants: English Domestics in the 18thc.] It was not confined to great houses, but was also expected in more modest establishments, although the amounts given were less. It was also not only expected on departure from the house of a friend: vails were disbursed by 'house tourists' to whichever servant showed them around - in most cases an upper servant.

...

An army officer described how much his visit to the house of a friend would cost him: 'The moment your departure is known, all the domestics are on the qui vive; the house-maid hopes you have forgotten nothing in packing up, if so, she will take care of it till you come again; this piece of civility costs you three ten-pennies; the footman carries your portmanteau .. to the hall, three more; the butler wishes you a pleasant journey - his greate kindness in so doing of course extracts a crown-piece; the groom brings your horse, assuring you 'tis an ilegant baste, and has fed well' - three more ten-pennies go; the helper runs after you with the curb-chain, which he has 'till this moment carefull secreted - two more; making a total of seventeen, or, in English money, upwards of fourteen shillings. A heavy tax for visiting a friend!' [Benson Earle Hill, Recollections of an Artillery Officervol. 1]

...

Richard Griffith from Bennetsbridge, Co. Kilkenny, complained in c.1760 in a letter to hise wife that 'an heavy and unprofitable Tax still subsists upon the Hospitality of this Neighbourhood .. in short while this Perquisite continues, a Country Gentleman may be considered but as a generous Kind of Inn-holder, who keeps open House, at his own Expence, for the sole Emolument of his Servants .. this Extravagance is not confined, at present, solely to the Country .. ; for a Dinner in Dublin, and all the Towns in Ireland, is even in a Morning, with a Person who keeps his Port, you may levee him fifty Times, without being admitted by his Swiss Porter. So... I shall consider a great Man as a Monster, who may not be seen, 'till you have fee'd his Keppers.' [R. and E. Griffith, A Series of Genuine Letters Between Henry and Frances, vol. 4]

...

Swift gives similar suggestions in Directions to Servants: 'By these, and like Expedients, you may probably be a better Man by Half a Crown before he leaves the House.' He further urges those servants who expect vails 'always to stand Rank and File when a Stranger is taking his Leave; so that he must of Necessity pass between you; and he must have more Confidence or less Money than usual, if any of you let him escape, and according as he behaves himself, remember to treat him the next Time he comes.'

...

Card money was particularly lucrative for butlers and footmen - so much so that, in London at least, such menservants refused service in houses where gaming parties were not held. [Marshall, Domestic Servants - Two footmen at the court of Queen Anne, Fortnum and Mason, used this perquisite as capital to begin their grocery business in London. Country House Lighting 1660-1890, Temple Newsam Country House Series No. 4] But it was vails that finally undermined the authority of the employers, who virtually allowed servants to dictate whom should be received, and then pretended not to notice when the servants extracted money from the departing guests.

...

In the London Chronicle a correspondent wrote in 1762 that 'Masters in England seldom pay their servants but in lieu of wages suffer them prey upon their guests'. George Mathew of Thomastown, Co. Tipperary, a man famous for his hospitality, was one of the first employers to ban the 'inhospitable custom' of giving vails to servants, and to compensate them by increasing their wages. This was apparently as early as the 1730s. His servants were warned that, if they disobeyed, they would be discharged. He also informed his guests that he would 'consider it as the highest affront if any offer of that sort were made'. [Anthologia Hibernica, I - No date given for this account, by 'Grand George' Mathew, who died in 1737, was the man described, who was host to Jonathan Swift at Thomastown in the 1720s, a visit described by Thomas Sheridan in A Life of the Rev. Dr. Jonathan Swift] A crusade against the giving of vails began in 1760 in Scotland, where seventeen counties issued appeals to abolish them. Four years later the movement had spread to London, resulting in riots there by footmen, the servants who stood to lose the most. [Marshall, Domestic Servants] It was probably at about the same time that employers from a number of counties in Ireland agreed among themselves to abolish vails. [Griffith, Series of Letters..., IV, 'An Agreement entered into among the Gentlemen of several Counties in Ireland, not to give Vails to Servants'] Like George Mathew before them, they decided to increase staff wages in an effort to compensate them for loss of earnings. One of them was Lord Kildare: in March 1765 he issued a directive from Carton to members of his household, stating that 'In Consideration of Vails &c, which I will not permit for the future to be received in any of my Houses upon any Account whatsoever from Company lying there or otherwise I shall give in lieu thereof... five pounds per annum each to the housekeeper, Maitre D'Hotel, cook and confectioner; three pounds per annum each to the steward at Carton, the butler, valet de chambre and groom of the chambers, and two pounds to the Gentleman of Horse.

...

And I will conclude with this funny account, about the penalty for being known amongst the staff to be a spendthrift, from the same book:

...

An unfortunate guest in England in 1754 found his punishment [for not giving vails] truly humiliating. 'I am a marked man,' he wrote, 'if I ask for beer I am presented with a piece of bread. If I am bold enough to call for wine, after a delay which would take its relish away were it good, I receive a mixture of the whole sideboard in a greasy glass. If I hold up my plate nobody sees me; so that I am forced to eat mutton with fish sauce, and pickles with my apple pie.' [Quoted in Marshall, Domestic Servants]

feel free to tip here (and yes the irony of this is not lost on me, although it did not occur to me until about halfway through writing this)

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

Where did the myth of "Australia" come from? I've heard many stories about that place but what are the origins of that legend?

Australia, or "North Tasmania," was first proposed by explorer Chris Columbus (no relation) in 1770. Many explorers died attempting to locate the island, and so many ships and bodies piled up that they formed a great barrier reef. In 1901, Captain John Green (no relation) found the great barrier reef and named it "The Great Barrier Reef" because Green was not a creative colonialist.

Around the same time however, Captain Woodward "Woody" Allen (no relation) discovered the island of West New Zealand. As Zealand itself in Denmark was itself only a few years old, and was farther west than the island, Allen named it "Slightly Newer Less West Zealand," the initials of which became the acronym, "Australia." Linguists are not sure how this works but as Allen was British and we still don't know what language was spoken in Britain in the 1700s, the words may well have worked out.

So the legend of Australia was born, and Britain immediately began exiling its worst criminals there, including Al Capone (no relation), Charles Manson (no relation), and Donald Trump (the same). Landing in Botany Bay (named for a location in Star Trek), the criminals began subjugating, abusing, and terrorizing the people who already lived there, as was the tradition at the time, through history, currently, and in the future.

Australia, despite its origin as a myth, is now a thriving country whose national anthem is a song about a homeless man drowning in a puddle.

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admired for its neoclassical elegance, the [...] silhouette of the early 1800s is linked to ideals of reforms [...]. For many these dresses embody the period depicted in Jane Austen’s novels, made familiar through cosy Sunday evening costume dramas. However, the sophisticated fashions worn by the Miss Emma Woodhouses of society were made possible only through the exploitation of people thousands of miles away. One of the most popular materials for these gowns was cotton, either a finely woven version known as muslin worn for evening wear or a slightly heavier weight cotton that was printed and used for day dresses. [...] When cotton became fashionable in the 1770s the best cotton muslins were imported as woven cloth from Bengal, which had been annexed on behalf of Britain by the East India Company in 1765. However, by the late 1700s vast amounts of raw cotton was imported from the southern states of America and the West Indies. Many of these cotton plantations, especially those in the Caribbean, were owned or managed by Scots, with the cotton sewn and harvested by enslaved men, woman and children brought over from Africa as part of the transatlantic slave trade, or their descendants. Cotton became a large part of the Scottish economy. The raw material was imported via Clyde ports from 1775 with 2,732,725 lbs imported in 1790 rising to 8,421,820 lbs in 1805. Cotton mills, which processed the raw cotton balls, were built creating a new industry. The first mill was built in Penicuik, Midlothian, but the majority were in Glasgow and surrounding counties, including New Lanark, where the damper climate aided production. Threads were spun and cloth woven, with further industries developing that embellished this naturally white fabric by embroidering, dying or printing on it. Some was sold and used here in Scotland, but the majority was exported with the result that cotton took over from wool as the leading British export good in 1803 – a position it held until 1938.

---

All text above by: Rebecca Quinton. “The Black History of White Cotton Dresses.” Legacies of Slavery in Glasgow Museums and Collections (a website maintained by curators and researchers of Glasgow Museums). 5 February 2019.

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, confession time - as a non-USAmerican I have never watched Liberty's Kids. What is the deal with James and Sarah? What is their story? Europeans need to know!

Hmmm... how to summarize the pain...

Ok so quick overview, Sarah is sassy British gentry and starts out a loyalist. She comes over from Britian (15 YEARS OLD AND UNCHAPERONED, but I digress) to find her dad, who fucked off years ago to the Ohio wilderness ostensibly to find land for their family to settle in because land is cheap (no, their financial situation isn't explained,) but he's an easily distractable man and seems to keep forgetting he has a family. She takes up residence in Benjamin Franklin's print shop, because him and her mother are Best Buds, and this is where James is an apprentice and also lives. (There are alot of historical inaccuracies here as the shop had zero living space and Ben Franklin had sold the Pennsylvania Gazette and retired from printing before the 1770s and was in no way involved.)

James is a poor orphan colonist who manages to get an apprenticeship at Benjamin Franklin's print shop, which is wild and amazing in its own right. He's a tad goofy, smart but dumb, and a firebrand patriot, although his enthusiasm for rebellion and violence cools over the series. The show frequently uses him to make commentary about not letting your enthusiasm take over your mind, and not letting yourself be swayed into violence because of mob mentality. (But of course its an American show about the American Revolution that got released in 2002, a year after 9/11, so even though it does make a real genuine effort to be Fair And Balanced about the whole thing, patriotism can't help but worm its way in.)

Anyway, both of these teens are smart-but-dumb, sassy, hotheaded, and stubborn. Not only that, they are set up to be on opposite sides of the Revolution. Its the perfect formula for enemies-to-frenemies-to-lovers pipeline, and also coworkers-to-lovers pipeline, with a dash of Idiots in Love and a little bit of Forbidden Love vibes, and what eleven-year-old can resist? And honestly? Its frequently written that way.

Ok so I said there was pain.

Sarah had a gold locket she was gifted by her father. Its precious to her and reminds her of her father, who's been absent for years. (Are you picking up all the Dysfunctional Family vibes yet? Stick with me.) In the first episode, she unwittingly gets caught up in the Boston Tea Party shenanigans and loses the locket in the harbor. Its a Huge Fucking Deal, losing her only tangible connection to her dad and her life back in Britain.

In the second fucking episode (this is important to the Pain,) we get some backstory for James. Him and Sarah get to talking when she opens up about her dad and about losing the locket. James opens up and we learn he was orphaned as an infant when his parents died in a house fire from a lightning strike. A neighbor saved him, but eventually he ended up wandering the streets of Philadelphia when still a child. The only thing he has left of his family - of any family - is his mother's wedding ring, which he wears. Although they come from different backgrounds, he actively empathizes with Sarah's situation and tells her he understands what it means to put alot of emotional weight on an item like a ring or a locket.

(The second episode was the first one I ever watched and I went fucking FERAL at this scene.)

Anyway, at the end of the, and I remind you, SECOND FUCKING EPISODE, James makes the decision to melt down his mother's ring to make a replacement for Sarah's locket.

Please just let that sink in.

Is it sunk in yet? Allow me to go feral for a defining moment in my first experience shipping.

James melts down the only thing of actual value in his possession, and the only remnant of his family, in order to give Sarah a replacement for the locket that her deadbeat dad absent father gave her. The scene is very sweet. Sarah is genuinely elated. James is thrilled she likes it. He fucking. Puts it on her. When she finds out where they got the gold, she calls it the greatest gift she's ever received.

The SYMBOLISM HERE IS NOT VERY SUBTLE, is it??? The Found Family. The Healing. The coming together to make things Right. The Sacrifice. The Radiant Joy of Love.

Now, there are other moments throughout the series hinting that the two of them have crushes on each other, some more obvious than others ("I'm so happy I could kiss you!!!") but here comes the fucking PAIN.

They don't fucking get together in canon. Despite it being obvious that the writers had set them up to be a thing. I don't know if it was just infighting with the writers and the studio, or if there was some executive who decided that romance was silly, or if someone thought that romance wouldn't resonate with their target audience (children ship ALL THE TIME wtffff) but a grievous sin was committed that day and I have been burning with Bad Feels ever since.

Anyway that's why I spend so many hours trying to correct this error with silly, sometimes horny lineart.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

& degeneration / degeneracy have even longer and more reactionary histories than i think many people realise—we tend to associate these terms w/ victorian britain & the evolutionary theorising that was taking place between about the 1840s and the turn of the century (chambers -> darwin; also the working-class importation / appropriation of lamarckian ideas that percolated in the penny presses and then in the edinburgh medical schools)—but the history runs back even further. degeneration’s counterpart, regeneration, had currency in the 18th century as both a religious concept and a biological one (as in, regeneration of organs) in france & germany. by the 1750s, claims were circulating that france in particular was morally & physically degenerate, a contention about the biological state of the population that initially finger-pointed primarily at aristocratic luxury, then shifted to blame the urban working poor. over the late 1770s and into the 1780s, this narrative combined w/ the percolating anxiety about the financial condition of the crown (which was essentially bankrupting itself behind the scenes in an effort to maintain control of its colonies & to fight near-constant imperial wars), & by the time the first revolution formally began in 1789, physician-reformers had become adept at presenting it as a socially curative event that would regenerate the entire society by bringing enlightenment moral & physical improvement to the social body in the form of moderate republicanism, continuous ofc w/ ongoing medical management of the individual. under the napoleonic consulate, ‘breeding treatises’ proliferated in which physicians purported to be able to teach people how to select spouses to optimise their children’s health / beauty / moral uprightness, & these ideas followed directly from 18th century breeding experiments on both animals and humans (eg, buffon used to arrange marriages of the peasants on his estate to test his theories about heredity). during the 1820s, public health became more cemented as a specialty & an academic discipline, & after the 1832 and 1848 repeat patterns of revolutionary violence followed directly by cholera outbreaks, the link became even more widely assumed between political unrest (a break w/ the enlightenment liberal project) & disease / death / degeneration. meanwhile all of this was ofc taking place against the backdrop of constant french nationalist concerns about population decline, industrialisation perceived to lag behind that of britain, & the need to promote reproduction for both these reasons (cf. the third republic’s and vichy regime’s natalist policies). all of this to say that degeneration and degeneracy theory have always been nationalist and (proto-)eugenic in character, & victorian britons were already drawing on a well-established tradition in this respect. these are really not concepts that can be divorced from this history.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benjamin West, Colonel Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye (Captain David Hill, 1776, oil/canvas (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

From the museum label: Hostilities between North American colonists and Britain were boiling over in the 1770s when Benjamin West painted this double portrait. The British wanted to ensure the loyalty of the Mohawk people, the easternmost tribe of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), in case of war.

British Colonel Guy Johnson commissioned the painting while in London with Mohawk Chief Karonghyontye in 1775. It commemorates Johnson’s promotion to British superintendent of the “Six Nations” (as the British called the Iroquois Confederacy). Karonghyontye was a prominent leader with a key role in diplomatic conversations.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was bound to happen sooner or later: a guest on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow presented an artefact, which derived from the slave trade – an ivory bangle.

One of the programme’s experts, Ronnie Archer-Morgan, himself a descendant of slaves, said that it was a striking historical artefact but not one that he was willing to value.

‘I do not want to put a price on something that signifies such an awful business,’ he said.

It’s easy to understand how he feels. The idea of people profiting from the artefacts left over from slavery is distasteful.

Yet, as Archer-Morgan said, it is not that the bangle has no value: it has great educational value.

It should be bought by a museum and displayed in order to demonstrate the complex nature of slavery and as a corrective to the narrative that slavery was purely a crime committed by Europeans against Africans.

The bangle was, it seems, once in the possession of a Nigerian slaver who was trading in other Africans.

It’s a reminder that slavery was rife in Africa long before colonial government.

It could also remind us that, though slavery was a global institution, the country that led the world in the rebellion against this barbarism – and played a bigger role than perhaps anyone else in its eradication – was the United Kingdom.

Britain did not invent slavery.

Slaves were kept in Egypt since at least the Old Kingdom period and in China from at least the 7th century AD, followed by Japan and Korea.

It was part of the Islamic world from its beginnings in the 7th century.

Native tribes in North America practised slavery, as did the Aztecs and Incas farther south.

African traders supplied slaves to the Roman empire and to the Arab world. Scottish clan chiefs sold their men to traders.

Barbary pirates from north Africa practised the trade too, seizing around a million white Europeans – including some from Cornish villages – between the 16th and 18th centuries.

It was in fear of such pirates that the song ‘Rule Britannia’ was written: hence the line that ‘Britons never ever ever shall be slaves.’

Even slaves who escaped their masters in the Caribbean went on to take their own slaves.

The most concerted campaign against all this was started by Christian groups in London in the 1770s who eventually recruited William Wilberforce to their campaign, and parliament went on to outlaw the slave trade in 1807.

British sea power was then deployed to stamp it out.

The largely successful British effort to eradicate the transatlantic slave trade did not grow out of any kind of self-interest.

It was driven by moral imperative and at considerable cost to Britain and the Empire.

At its peak, Britain’s battle against the slave trade involved 36 naval ships and cost some 2,000 British lives.

In 1845, the Aberdeen Act expanded the Navy’s mission to intercept Brazilian ships suspected of carrying slaves.

Much is made about how Britain profited from the slave trade, but we tend not to hear about the extraordinary cost of fighting it.

In a 1999 paper, US historians Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape estimated that, taking into account the loss of business and trade, suppression of the slave trade cost Britain 1.8 per cent of GDP between 1808 and 1867.

It was, they said, the most expensive piece of moral action in modern history.

The cost of fighting the slave trade cancelled out much, if not all of Britain’s profits from it over the previous century.

There are those who continue to demand reparations for slavery from the UK government and other western powers, yet they rarely, if ever, acknowledge Britain’s role in all but eradicating the evil of the transatlantic slave trade, a cause on which we spent the equivalent of £1.5 billion a year for half a century.

Britain’s role in hastening slavery’s extinction is a remarkable achievement.

It’s astonishing that we have forgotten it almost entirely in the 21st century.

It would be difficult to find anyone in the world whose ancestral tree does not somewhere extend back to a slave-trader.

Huge numbers of us, too, will have been partly descended from slaves.

Britain should not minimise or deny the extent to which it traded slaves to the colonies in the early days of Empire.

But it is also important to remember the thousands who served and died with the West Africa Squadron while seizing 1,600 slave ships and freeing some 150,000 Africans.

We must examine and remember everything about the history of the slave trade, including the forces – moral and military – that eventually brought it to an end.

It’s profoundly worrying that slavery evolved to be a near-universal phenomenon among human societies and inspiring that it came to be all but eradicated within a single human lifespan.

#Britain#slave trade#Antiques Roadshow#Ronnie Archer-Morgan#ivory bangle#artefacts#Rule Britannia#William Wilberforce#Aberdeen Act#slavery#suppression of slave trade#moral action#transatlantic slave trade#BBC

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Silk Robe à l’Anglaise, ca. 1747 (altered 1770s), British.

Met Museum.

#beige#silk#extant garments#womenswear#dress#1747#1770s#1740s#1740s dress#1770s dress#1740s britain#1770s britain#1740s extant garment#1770s extant garment#british#met museum#robe à l’anglaise

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Independence Day

Independence Day, also known as the Fourth of July, or July 4th, takes place on the anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. It celebrates the United States and its independence from Great Britain. It is a patriotic holiday extolling the positive aspects of America, and themes such as freedom and liberty.

The Revolutionary War began in April 1775, at a time when many still did not want complete independence from Britain. This sentiment was changing by mid-1776, fueled by things such as the publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense. On June 7, the Continental Congress met at the Pennsylvania State House—a building now known as Independence Hall. Henry Lee, a delegate from Virginia, introduced a motion calling for independence for the colonies. It was contentiously debated, and a vote on the matter was postponed. A committee was appointed to write a statement outlining the reasons why a break from Great Britain was necessary. The committee consisted of John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson—who became its main author.

On July 2, the Continental Congress voted in favor of Henry Lee's resolution for independence. Two days later, on July 4, the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Although this was not the actual day of the vote for independence, it became celebrated as Independence Day. The first public reading of the Declaration of Independence took place on July 8, and the document began being signed on August 2. It is interesting to note that both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died on July 4, 1826, on the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

The King's birthday had been celebrated in the colonies in the years leading up to independence. Festivities included bonfires, the ringing of bells, processions, and speeches. During the 1760s and early 1770s, King George III was still celebrated, but Parliament was disparaged. But, in the summer of 1776, some held mock funeral celebrations for the king, illustrating how the monarchy would no longer control colonists.

Celebrations that were modeled after the king celebrations followed soon after the Declaration of Independence was adopted. They consisted of parades, concerts, bonfires, and the firing of cannons and muskets. The reading of the Declaration also became part of the festivities. The first annual commemoration was held in Philadelphia on July 4, 1777, while the Revolutionary War was still raging on. In 1781, Massachusetts became the first state to make the day an official state holiday. Political leaders often addressed crowds on the day. The goal was often to create unity, but by the mid-1790s, the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties were holding separate politically oriented celebrations in large cities on the day.

Following the War of 1812, the holiday became more widespread. Still, it wasn't until 1870 that Congress made the day a federal holiday. It did not become a paid holiday for federal workers until 1941. In the late nineteenth century, there began to be a focus on leisure activities on the day, with family get-togethers, barbecues, and fireworks being big parts of the day. Around that same time, the Safe and Sane Fourth of July movement came about, in response to heavy drinking that often went with the day, as well as injuries that came from fireworks.

Today the day does not have the same political importance it once did, although politicians still speak at many events. The day is commonly celebrated with parades, fireworks, concerts, barbecues, picnics, family gatherings, and watermelon and hot dog eating competitions. Sporting events and activities often take place, such as baseball games, tug-of-war, three-legged races, and swimming. The displaying of the American flag is an important part of the day. Many people also take an extended weekend and travel somewhere for vacation on the days surrounding the holiday.

How to Observe Independence Day

There are many ways you could celebrate Independence Day:

Read the Declaration of Independence.

Fly the American flag.

Go to a parade.

Attend a barbecue, picnic, or gathering with friends.

Attend a Fourth of July concert.

Attend fireworks in your community.

Light off your own fireworks.

Listen to patriotic songs, or songs fitting for the Fourth of July.

Learn the words to "The Star-Spangled Banner," the country's national anthem.

Participate in or attend a sporting event, or a watermelon or hot dog eating competition.

Take a vacation somewhere. You could see the Declaration of Independence, as well as other important documents, at the National Archives Museum in Washington D.C. You could also visit Independence Hall or the Statue of Liberty.

Source

#Independence Day#IndependenceDay#FourthOfJuly#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#architecture#landscape#New York City#Grand Canyon National Park#Washington DC#Mount Rushmore National Memorial#Chicago Hot Dog#Original 5 Napkin Burger#Porterhouse for 3#steak#Yosemite National Park#Arches National Park#US flag#Monument Valley#4 July 1776#anniversary#US history

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Swords

The sword, besides its function as a weapon, was an instrument worn as an accessory and symbolic. Thus the sword stood for leadership, power, justice, dignity and honour.

Lloyd's Patriotic Fund Sword and Belt of £100 Value to Jahleel Brenton Esq., Captain of H.M.S. Spartan, Presented in 1810 (x)

The sword is regarded as an emblem of military honour and is supposed to encourage the wearer to a righteous striving for honour and virtue. It is a symbol of freedom and strength. And so, especially in the 18th century, wealthy and high-born men carried swords to signify their status as gentlemen, such status being required of an officer in the Navy.

Captain Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), by John Francis Rigaud and an american officer, possibly Charles Goodwin Ridgely (1784-1848), by Gilbert Stuart, both with their swords (x) (x)

In battle, however, officers armed themselves often with short swords or cutlasses, which were suitable for close combat in the cramped conditions on the deck of a warship.

Naval Fighting Sword, 1770-1795 (x)

What we usually see on portraits were long swords, often with decorative hilts. These swords were dress swords, intended for display rather than combat. Sometimes officers were given valuable swords in recognition of bravery or outstanding service. These were then either taken on board or left at home and sold if necessary.

Officers sword, late 18th century (x)

When a naval officer was court-martialled, his sword was taken from him and placed on a table in the courtroom to show that his rank and standing had been put on hold. If he was acquitted, he received his sword back. If he was found guilty, the point of the sword was pointed at him and the verdict pronounced. This practice was maintained in Britain until 2004.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wonderful gold flowers on this dress

1770-1775

Britain

Silk, Metall

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indentured Servitude, Convict Servitude, and Slavery

Before I start, I want to be extremely clear that this is focused on 18th century Britain and British America. Other cultures, and other time periods, have different forms of all of these, but this is my primary period and place of study. I am going to break each section into its own post because I've had issues with long posts, I ask that you reblog the last post so the whole thread is accessible. Content warning for slavery, abuse, rape

I am writing this because it is a subject I have focused much of my own research on, and in my career I have discovered that many people are confused about what these are all in general, and particularly how they differ from one another. That is the main thing I am attempting to explain, while giving general brief overviews of each. I don't generally do "heavy history" stuff here, and I didn't go out of my way to do specific research for this: it's based on my preexisting knowledge, and it's not heavily footnoted, though I did look up a few specific things to cite. Feel free to ask questions or add insight of your own!

Indentured Service

The biggest thing that differentiates indentured servitude from the other forms I will discuss is in the name itself: “indenture” means contract. The person being indentured would sign a contract, which could be purchased by somebody to own their labour for a period of time. This is vital, because at least ostensibly it was entered into willingly. This is not to say that it was not rife with abuse: it was. Even setting aside times people were outright coerced or fooled into indenturing themselves, it was often done by people who were desperate. Still, it provided more agency than the other two forms. But perhaps even more importantly, the indenture gave them legal protection in the eyes of the law. If their master was not abiding by the contract, they could be sued at court, and while I have no doubt that servants had the odds against them, I can document many cases of them successfully winning their suits and being paid out hefty sums in damages. The opposite is true as well, of course - generally, if a servant runs away and is returned, they can be brought to court by their master, and typically the punishment is to have time added to their contract (usually, the time they were away plus additional time). And for what it's worth, I have even seen servants go to court to extend their own contract, or sign a new one, because they were unable to support themselves on their own. This is exceedingly rare, but I have seen it.

In the broadest sense, people who entered an indenture typically did so to pay off some kind of debt. This might be a preexisting debt, or it might be one that they incurred in the process of signing the indenture itself: for many Europeans, the possibilities promised in America were alluring enough (or their present lives difficult enough) that many were willing to indenture themselves explicitly to have their passage to America paid, and then spend years working off that debt in hopes of establishing themselves new lives in America.

It's important to note that Britain, and much of Europe, was already rather densely populated at this time. And because it had been so urbanized there was in many places little land to be found, and what there was tended to be owned by the wealthy elite already. In America, the exact opposite was true: there was seemingly endless land, and relatively few people. For some frame of reference, in the 1770s the most populated city in North America is Philadelphia, with somewhere around 30-40 thousand people living there. By contrast, London at the same time had well over a million people. So the hope that many people had was that they could come to America, acquire land of their own, and at the very least subsist off of their own work, and ideally maybe even succeed well enough to improve their lives. And not merely monetarily, but also in status: owning land conferred benefits in society such as being able to vote, hold office, etc.

This was, of course, part of the much broader issue of Europeans encroaching on lands held by Native people and the displacement and genocide perpetrated against them. And especially in colonies where tobacco was the primary cash crop, it had a devastating effect on the land itself: unless done with proper and careful crop rotation, tobacco ruins the soil it's planted in within a few years, and you are unable to plant anything there for upwards of 20 years. Generally, the Europeans in America were practicing what we might call "slash and burn" planting, where they cared only about quick profits and would raze the ground, constantly wanting to replace the lands they had spoiled and stealing increasingly more and more land from Native nations and tribes in their avarice. And while this was exponentially more of an issue with the wealthiest of planters - people like the Washingtons, who had hundreds of thousands if not millions of acres of land and were always looking for more - the sheer number of small farms still had a cumulative effect.

Anyway, the point being this was an alluring prospect for many poor labourers and tradespeople in Europe who were in hyper-competitive job markets where they could expect extremely exploitative, low wages for exceptionally high quality, production, and specialized labour. Even tradespeople in America made much higher wages on average (often for poorer quality work) than England, for example, although many people who performed trades in their homeland were keen to drop their tools and pick up a hoe in America. This was in fact sometimes such a big problem that there are instances of colonial governments essentially subsidizing tradespeople, paying them to continue doing their trade so that they have people doing that sort of work. Over time this became less common, especially as the number of enslaved labourers outpaced indentured servants: with so much of the field work being done by enslaved people, it became more common for indentured servants to be put to work at their trade, although it was still common for them to cease their trade and acquire land of their own at the conclusion of their contract.

As for the contracts themselves, there were standard forms that could be used, but there was flexibility in the some of the language, and especially the length of the contract. One of the more common misconceptions I hear and see about indentures is that they typically lasted seven years, and I will explain in a moment why I think that misunderstanding happens. When I have looked at indentures, most often they're for somewhere between 3-5 years, although they can be longer or shorter as well. It's not particularly uncommon to see even 1-2 years, I've even seen some that are just for months at a time.

There are also occasionally some interesting clauses written into contracts. Sometimes it will stipulate what role or duties the servant will perform: whether it's to keep performing their skilled trade, or to act as a domestic servant, for example, because the default is so often, at least in America, that they are going to be working in the fields. A somewhat common turn of phrase you see is "will not be put to work at the plow", i.e. that they will not be doing farm work. Which, having done some 18th century farm work in the Virginia summer, I can wholly understand.

As an aside, if you want to read a diary of an indentured servant, the account of John Harrower is interesting. He was a Scottish man who indentured himself for America in the early 1770s. He’s kind of an exceptional case, because it appears he had been a somewhat successful merchant who had fallen on hard times: he is clearly more educated than most, and he is hired specifically to be a schoolteacher for his wealthy master’s children (and eventually, for other children in the nearby plantations, for which his master charged fees and paid Harrower a portion of them). Still, there’s some fascinating details in there, particularly about the ship journey over, but also just every day life in Virginia.

I think the most fascinating passage in the whole thing is also the most harrowing (no pun intended), where he describes how he and the other servants are to be sold:

You can read his journal here: https://archive.org/details/jstor-1834690

25 notes

·

View notes