#1860s britain

Text

Blue Silk Corset, 1864, British or French.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#blue#silk#corset#1864#1860s#1860s corset#1860s undergarment#undergarments#1860s extant garment#extant garments#womenswear#19th century#1860s France#1860s britain#British#french#V&A

685 notes

·

View notes

Text

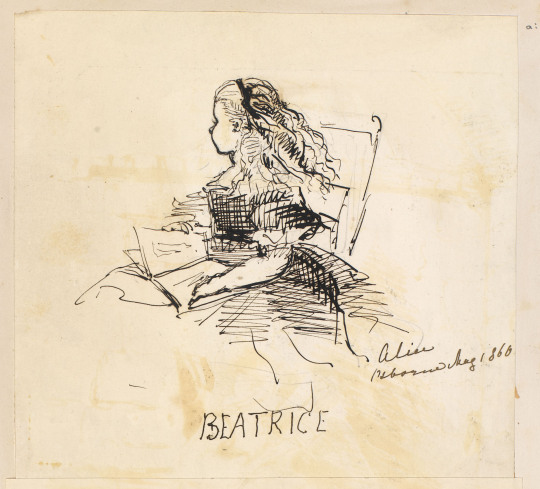

Drawing of Princess Beatrice of Great Britain and Ireland (later of Battenberg) done by her elder sister Princess Alice of Great Britain and Ireland (later GD of Hesse), Osborne House August 1860

#so cute#princess alice#princess beatrice#princess alice of hesse#princess Alice of Great Britain and Ireland#princess beatrice of battenberg#princess Beatrice of Great Britain and Ireland#grand Duchess of Hesse#art#osborne house#august#1860

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Illustration designed by Charles Henry Bennett for an 1861 edition of Quarles' ‘Emblems'

#engraving#wood engraving#Francis Quarles#Charles Henry Bennet#1860s#1860#victorian#prints#illustrations#cherubs#children#london#britain#europe#Bennett drew on wood and then had a wood engraver actually engrave it#I think the wood engraving looks very nice#frogs#snakes#maybe I'll read some of Francis Quarles' work idk#see whatever this is about#19th century

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thomas Francis Dicksee, (English, 1819-1895)

Waiting, 1860

#art#Thomas Francis Dicksee#english#england#Christendom#island nation#uk#united kingdom#western civilization#britain#fine art#waiting 1860#european union

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

As D'arcy Uhr's 1868 Gulf killings became known in Britain, The Brisbane Courier still hoped the Aborigines' Protection Society could bring its influence to bear in Westminster.

The attack on the camp at Morinish was a trifle, performed in the grey of the morning, before breakfast, and when there was nothing to incite the preserver, of the peace and defenders of the lives of the colonists, but Mr. Uhr's was a regular expedition of vengeance, and a battue* of fifty-nine wild blacks is the result.

* The beating of woodlands to flush out game.

"Killing for Country: A Family History" - David Marr

#book quotes#killing for country#david marr#nonfiction#wentworth d'arcy uhr#60s#1860s#19th century#native police#killing#death#britain#the brisbane courier#newspaper#journalism#aborigines protection society#influence#westminster#morinish#breakfast#peace#defence#colonist#vengeance#battue#indigenous australians#aboriginal australian

0 notes

Text

From Glens Falls to Chester: The Mills family in the Adirondacks

This was originally the second chapter in my family history on the Mills family, but has been adapted and changed for this blog. All the sources are noted in a bibliographic essay at the end of this post, with maps and other photos throughout. Enjoy! This was originally posted on the WordPress version of this post. It has been split in a few posts so it is more readable on here.

By 1860, the Mills family was still in Bolton. John Mills was said to be 54 years old, still a miller, and his wife Margaret, age 36, was listed as a housekeeper. There were nine children in the household. Two of them, Joseph B., age 18, and Thomas, age 14, were farm laborers, presupposing that the Mills family owned a farm in Bolton. While Hetabella, age 18, did housework, the other children seemed to be too young to be listed with occupations. They included Edward (age 12), Dory A (age 10), Mary J (age 6), John C (age 4), Margaret E (age 3) and Benjamin W. (age 3/12). Bolton was similar to what it was in 1855, still undoubtedly having an agricultural and working-class character.

Four years later, in 1864, a woman named Margaret E. Mills declared loyalty to US, withdrawing loyalty to Great Britain and Ireland. This woman is likely Margaret Bibby. Unfortunately she did not state her age or place of birth.

The following year, 1865, the Mills family had moved back to Chester. John Mills was a 60-year-old farmer with his wife Margaret, 40 years old. This is the first census which states the number of John and Margaret’s children, which numbers 12! Within the household in the frame house, were 10 children, meaning that two of her children were not in the household. The names of those two children are not currently known. This census was the first to name Robert B. Mills, a person who was 2 ½ years old. Others in the household included Hattie B. Mills (age 21), Joseph B Mills (age 20), Thomas Mills (age 18), Edward Mills (age 18), Dora A. Mills (age 14), Mary J. Mills (age 9), John C. Mills (age 7), Margaret E Mills (age 5), and William Mills (age 4). With such a big family, it is likely that Hattie (same as Hetabella) took care of the family, especially Dora, Mary, John C., Margaret E., and William, who were younger than her. Joseph B. and Thomas likely worked on the farm with their father. This can only be inferred as the census does not state this directly.

Chester seemed to the same in some respects as it was when the Mills family lived there in the late 1830s and early 1840s. Nearby to the Mills family was the family of George Bibby. He was a 46-year-old farmer born in Ireland, with a family of six: his wife Ann born in the county, age 30, has five children, now married; Helen, age 9, Katherine, age 7, Samuel, age 6, William, age 4, and George, age 1 and 8/12. Also living in the household is his father, Samuel Bibby, age 67, born in Ireland, a laborer.

Another family nearby was Thomas Bibby’s family, living in the household of the Wallaces. Hewas age 28, born in Ireland, a farmer and married to someone named Mary A. Bibby (age 25, born in Warren). There is also a family of Thomas Mills (age 59, born in Ireland, farmer) nearby who has a wife named Margaret (age 53, born in Ireland, has 12 children), John (age 23), Edward L (age 21), Margaret (age 19), Phebe (age 15), Thomas J (age 11), and Ellen Gray (sister, age 60, born in Ireland). It is not known if any of the Mills children were living with these individuals at the time, but is likely that they were living somewhere in Chester.

By 1870, the Mills family was still living in Chester. John Mills was a 66-year-old farmer married to Margaret, age 48. In the household was their 23-year-old son, Joseph B., a carpenter, their 21-year-old son, Edward E, a farm laborer, and their 19-year-old daughter, Dora A, a teacher. At home were the rest of the children, Mary J (age 17), John C (age 14), Maggie (age 11), Willie or William (age 7), and Robert or RBM II (age 5). Both John and Margaret noted that they had parents of foreign birth. Also on the same page was Samuel Bibby (age 73 born in Ireland), Thomas Mills (age 64, farmer, born in Ireland), his wife Margaret (age 57, born in Ireland), Thomas Bibby (age 34, born in Ireland).

As the years passed by, John and Margaret were getting older. As her Find A Grave entry reports, since she has no visible gravestone photo, she died in 1874 in Minerva, Essex County, New York. This cannot be disproved or proven by any records on the subject.

The 1875 census shows a 70-year-old John Mills still living in Chester, as a farmer, with seven children in the household. These included his son Joseph B, a 29-year-old millwright, his daughter Dora, 24-years-old, his daughter Mary, 21-years-old, his son John C, 18-years-old, his daughter Maggy, 16-years-old, his son William, 14-year-old, and his daughter Hattie, 31-years-old. The latter was married to a 37-year-old carpenter named Hannibal Hammond and had a 12-year-old child named Ellen. It is important to note that Margaret is not in the household, so from this record, her death date can be ante 1875, or more accurately sometime between 1870 and 1875. While the census takers could have missed her, considering she was in every since census since 1850 seems to indicate that she was not alive.

The families of Isaac Mills and George Bibby were also living in the area. Isaac Mills’s family consists of: Isaac (born in Ireland, age 62, farmer), Ann (wife, age 46, born in Ireland), Joseph W (age 26, born in Warren, farmer?), Edward B? (farmer? Age 24, born in Warren), Mary (age 21, born in Warren), James O (age 20, born in Warren). George Bibby’s family consists of: George (age 53, farmer, born in Ireland), Ann (wife, age 40, born in Warren), Ellen (age 20, born in Warren), Caty (age 20, born in Warren), Samuel (age 16, born in Warren), William B (age 18, born in Warren), Albert (age 8, born in Warren), Humbert, (8 11/12 months, born in Warren), and Samuel (father, age 78, born in Ireland, likely a farmer of some type). These two families may have been connected together by marriage or even Isaac could have been John Mills’s brother. Sadly, those specifics are not completely known.

In 1876, John Mills died in Minerva, Essex County, New York, apparently while he continued his job as a miller. I have contacted appropriate historical societies in hopes of gathering more information. It is possible that Mills family members were living in that area of New York, or even Bibby family members since his wife Margaret was buried there. Perhaps she was going on a trip to bisit her cousins or even her parents. We don’t know exactly but can only make historical suppositions.

To this day, the Warren County Historian’s Office has family files on the Mills and Bibby families. 17 individuals with the Mills surname living in Ireland (mainly in Cork) and two with the Bibby surname were living near or around Kilkenny at the time (1876).

By 1876, with the death of John Mills, the twelve children he fathered with his wife Margaret, were on their own. Each of them would chart their own, independent path. As Charles Frederic Goss wrote many years later, RBM I, was only 10 (or 12) when his father died. This likely had a strong psychological effect on him, as it would on anyone, especially one who is that young. It meant that those such as RBM I, his brother William, and other younger siblings had to make their own way.

By 1876, Dora was only 25-years-old, if we use the age in the 1875 census. She likely did not even know of the Packard family in Massachusetts or of a man named Cyrus Winfield Packard, who was only 24 at the time, and would later be her husband. She had not, like Cyrus, run away from home at a young age. This is not because she worked more than Cyrus, who came from a family of hard-working farmers who had roots dating back to Samuel Packard, an immigrant from England in 1638, and had moved from eastern Massachusetts, mainly in Bridgewater, to Western Massachusetts, specifically in Cummington and Plainfield. Instead, she possibly found at least some value in her life as a teacher and likely helping around the home (and probably the farm). This would serve her well in years to come.

© 2018-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#mills family#packard family#mills#packard#genealogy#family history#1870s#1638#immigration#settler colonialism#early settler#settler violence#1830s#1840s#1860s#19th century#massachusetts#ireland#britain#marriage#family#households

0 notes

Text

Dress of cotton muslin, gilded metal thread and Indian jewel beetles (sternocera aeqisignata), Britain, 1868-9

The wings of jewel beetles (buprestidae) were traditionally used to embellish textiles in South America and South and Southeast Asia. Emerald-green beetle-wing decoration became a symbol of high status in India during the Mughal period (1526-1756). Western traders in India then introduced these textiles to Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. British newspapers report on several women wearing dresses decorated with beetle wings at court during the late 1820s and early 1830s. By the 1860s beetle wings were being imported to Britain in volumes of 25,000 per consignment, to be applied to textiles in imitation of the Indian technique. The wings were cut, shaped and arranged in stylised floral patterns, often accented with metal thread. The wings would have glittered in candlelight, achieving a sought-after iridescent and jewel-like effect.

#historical fashion#fashion history#19th century fashion#19th century#victorian fashion#1860s fashion

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress. Scotland, Glasgow (place of manufacture), circa 1863. Wool, cotton.

Glasgow Museum Collections

Woman’s dress in light purple wool embroidered with in purple and white thread in tambour-work in an abstract pattern. High round neckline trimmed with lace, bodice loosely pleated from shoulders to wide v-shape at straight waistline with two narrow vertical pieces of gauze with tambour-work centre front with fastening behind of nine metal hooks and thread eyes attached to lining. Full-length sleeves with short pointed frill at shoulder edged with tambour-work, applied narrow piece of gauze around lower arm to suggest folded back cuff, hem edged with white lace. Skirt, full-length, pleated into waistband with tambour-work border around lower half, opening at front fastened by two metal hooks and thread eyes with small watch pocket in waistband. Bodice and sleeves lined with glazed cotton, skirt lined with cotton.

This beautiful dress is made from light purple wool. The silhouette follows the fashions of the early 1860s with a softly draped bodice and wide, full-length skirt that would have been held out by a steel-framed cage-crinoline.

The dress is decorated with an abstract pattern in purple and white thread tambour-work. The stitch resembles chain-stitch but is worked with the cloth stretch over a hoop, known as tambour, using a small hook rather than a needle. The technique originated in India and reached Britain the 1760s. By the early 19th century the west of Scotland was a leading centre for manufacturing tamboured muslins, with up to 20,000 women and girls in total working in the British industry.

475 notes

·

View notes

Text

White cotton dress with green beetle wing embroidery, 1868-1869, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#V&A#womenswear#extant garments#dress#Cotton#beetle wing#19th century#Britain#1868#1860s#1860s dress#1860s britain#1860s extant garment#embroidery

497 notes

·

View notes

Photo

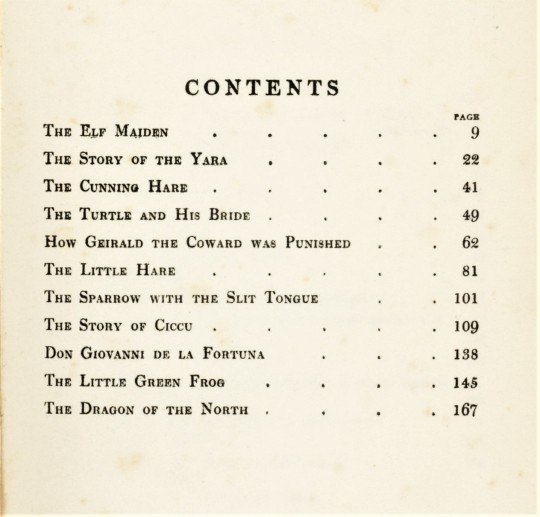

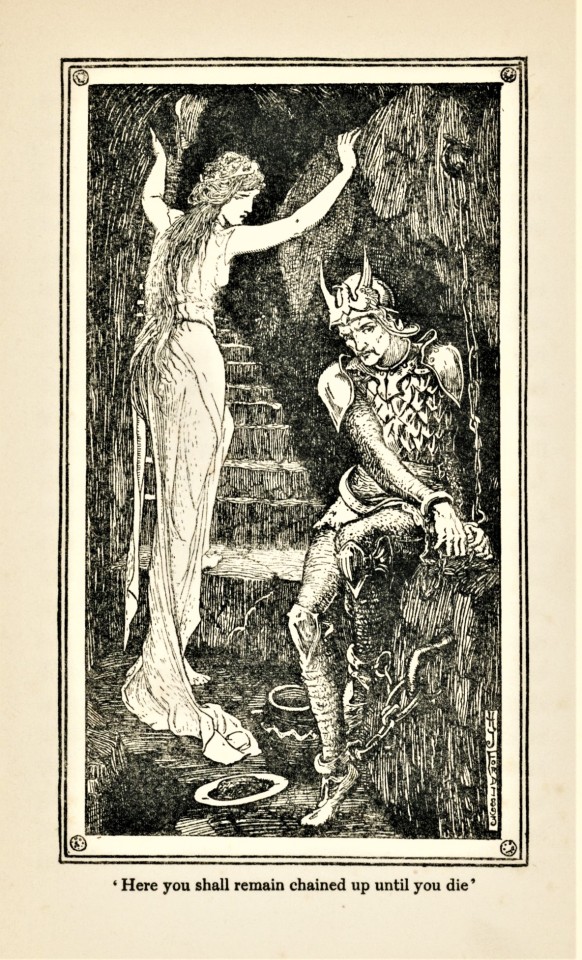

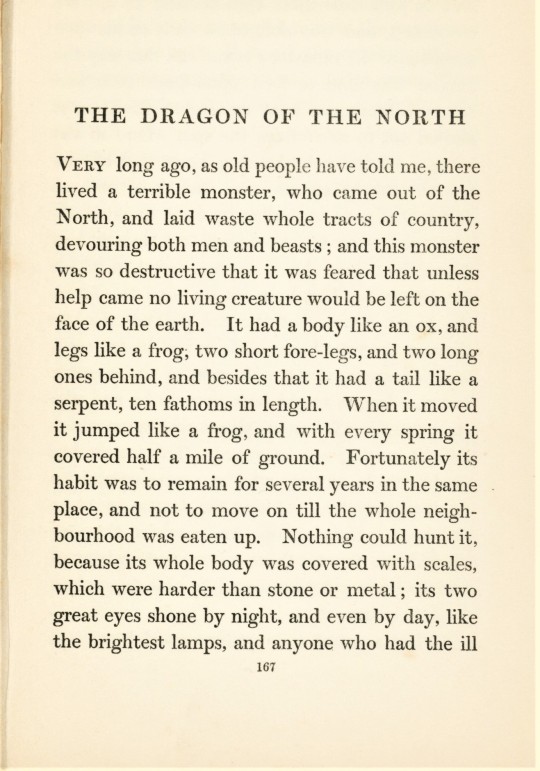

Andrew Lang Fairy Stories

With this semester - and my internship - coming to a close, I wanted to hop back into my wheelhouse for the remainder of my time in Special Collections.

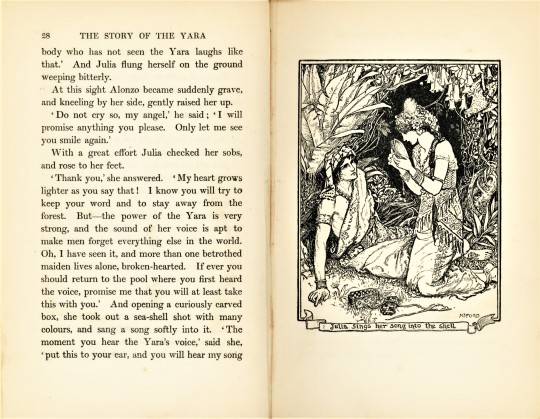

The Elf Maiden: And Other Stories is a collection of eleven tales edited by Scottish poet and novelist Andrew Lang (1844-1912) and illustrated by Henry J. Ford (1860-1941). The book was first published in London and New York by Longmans, Green, & Co. in 1906. The stories in this edition first appeared in three of Lang’s popular “Coloured" Fairy Books: The Yellow Fairy Book (1894), The Pink Fairy Book (1897), and the The Brown Fairy Book (1904). Lang’s Fairy Books were a series of 24 children’s fairy tales, the most popular being the 12 Coloured" Fairy Books, that Lang’s wife, Leonora Blanche Alleyne (1851-1933) helped collaborate and translate.

Lang was considered to be one of the most versatile writers of his time. While he was a poet, historian, journalist, and critic, he was best known for his publications on folklore, mythology, and religion. Lang took an interest in folklore at a young age; he read John Ferguson McLennan before going to Oxford and was heavily influenced by Edward Burnett Tylor.

Henry J. Ford was a prolific and successful English artist and illustrator. While he began exhibiting with historically-themed paintings and beautiful landscapes at the Royal Academy of Art in 1982, it was his contributions to illustrated books that raised him to fame. I was excited to find that he was most famous for the illustrations he provided for Lang’s popular Fairy Books, which captivated an entire generation of children in Britain; these books saw translations and republications during the 1880’s and 1890’s.

View more posts on books by Andrew Lang.

View more posts on fairy tales.

View more posts from our Historical Curriculum Collection.

-- Elizabeth V., Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

#Fairy Tales#Andrew Lang#The Elf Maiden#Henry J. Ford#Longmans Green & Co.#Lang's Fairy Books#Andrew Lang's“Coloured" Fairy Books#folktales#children's books#Historical Curriculum Collection#Elizabeth V.

640 notes

·

View notes

Photo

photograph, 1862-1863, taken by Lady Clementina Hawarden

#Clementina Maude#Lady Clementina Hawarden#victorian#1860s#19th century#britain#europe#costumes#fancy dress#jesters#harlequins#people#girls#portraits#group portraits#photographs#albumen print#these people probably weren't dressed up for halloween but it is that time of year yaay halloween yay costume time

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

After African missionaries circulated initial reports about the slave labor behind sugar in the 1790s, some consumers desisted from sugar entirely -- "anti-saccharites", mostly fervent Christians such as Quakers. As the East India importers created a market in Britain, anti-slavery societies became their free marketing teams, widely distributing pamphlets such as "What Does Your Sugar Cost?" A Cottage Conversation on the Subject of British Negro Slavery. Meanwhile, in America, the free-produce movement was led by black women, who encouraged their segregated groceries to buy only slavery-free goods.

The bind that free Black Americans faced in sourcing their food and raw materials was especially harsh. They were forced to buy "ethical" expensive cotton from white farmers instead of black slaves, which frustrated those trying to support black businesses. They sought coffee from Liberia and Haiti, hoping that the majority black demographics of these countries would support black uplift and prevent slave labor, and these created natural (and, indeed, slavery-free) coffee industries in those countries which indeed persisted for some decades.

The most surprising part of this story comes in the 1840s. After abolishing slavery in 1836, Britain had placed tariffs on slave-produced sugar in order to ensure fairness for British sugar producers who paid their laborers. This inflated sugar prices generally. Without tariffs, "free-labour sugar" would cost three times as much as its competition, defeating the East Indian importers' argument that slavery was a corrupt process which artificially inflated prices. It soon became clear that the writing was on the wall. In 1845, the primary importer of "free-labour sugar" exited the sugar market, and the following year, Britain decided to remove all the tariffs, for the benefit of consumers. Free-labour sugar completely vanished as a category thereafter.

Meanwhile in the United States, abolitionists criticized the free-produce movement as ineffective; similar to "free-labour sugar", it only placed an extra economic burden on those struggling to live ethically. It was recognized on both sides of the Atlantic that making individual consumer choices was not enough, and that systemic change was necessary to permanently eliminate slavery. As a status symbol, though, "free cotton made by escaped slaves" continued to be worn in Britain and attracted comment in aristocratic salons into the 1860s. In this final stage of the movement, free labor was considered to be part of a civilizing project, a way to train ex-slaves in useful arts.

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/138i5at/comment/jj04qsx/?context=3

886 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes