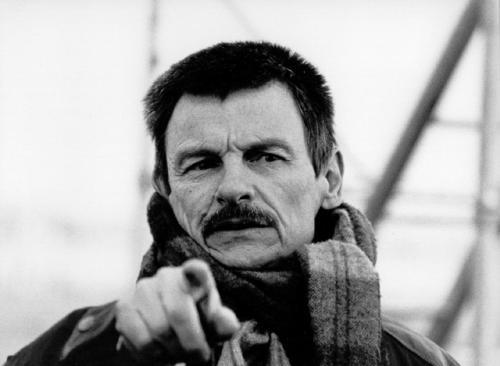

#Alexander Knyazhinsky

Text

Stalker (1979) (Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky) (DoP. Alexander Knyazhinsky)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stalker (1979)

Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography by Alexander Knyazhinsky

#art#film photography#cult film#film#classic film#art history#movie#beautiful photography#art film#films#filmmaking#philosophy#soviet film#soviet#soviet cinema#soviet art#andrej tarkovskij#andrei tarkovsky#andréi tarkovski#stalker#russian film#russian art#sci fi movies#russian#russian cinema#movie stills#film stills#film screenshots#the zone#roadside picnic

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979)

A beautiful looking film, that has been an inspiration to many film makers. Recently (last ten years) Von triers Anti-Christ has a definite similarity of tone, borrowing the burnt out imagery created by the cinematography of Alexander Knyazhinsky for its own bleak introduction. Its got a lot going for it, in that it is infinitely clever and inventive, a sophisticated mash-up of high art and genre. Its also incredibly perceptive of future events such as the Chernobyl disaster. Several years later those employed to take care of the abandoned Chernobyl nuclear power plant would refer to themselves as "stalkers" and to the area around the damaged reactor as The Zone. However, it is a bit of an ordeal, sometimes high on art and low in substance, characterised by long difficult passages of tracking shots and endless bleak mundane action. (reposted from 2012)

0 notes

Text

If more houses had water butts, it could help with drought, flooding and water pollution

If more houses had water butts, it could help with drought, flooding and water pollution

If more houses had water butts, it could help with drought, flooding and water pollution

A small rain tank could supply 15% of a household's total annual water consumption on average across the UK. Alexander Knyazhinsky/Shutterstock

Earlier this year, southern England experienced its driest July on record. The drought affected many parts of the UK and grew so acute that Thames Water’s hosepipe…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

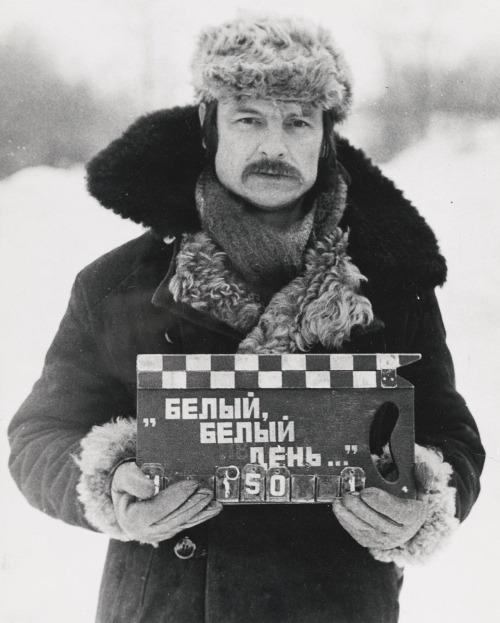

Stalker

1979

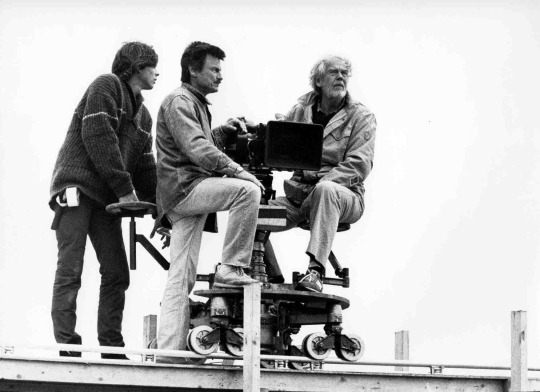

Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–1986), director

Alexander Knyazhinsky (1936–1996), cinematographer

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stalker (1979) dir. Andrei Tarkovsky

#stalker#andrei tarkovsky#cinematography#alexander knyazhinsky#russian cinema#anatoly solonitsyn#nikolai grinko#alexander kaidanovsky#film stills#subtitles#movies

369 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stalker (1979, Soviet Union)

Before one makes assumptions about this film’s title, the word “stalker” here refers to both the modern definition of the word and as a nickname (from Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co.) for a character who smuggles people to a specific place. Andrei Tarkovsky’s ponderous, glacially-paced Stalker is among the greatest science-fiction movies – delving into questions of existentialism, rational choice, the danger of subconscious desire, faith, and the limits of human understanding. For Stalker, Tarkovsky has fully embraced minimalism – the film has 142 shots in its 163-minute runtime (the longest shots are uncut for over four minutes; the first spoken line appears after nine-and-a-half minutes) – making this movie inaccessible for those without grounding in or preparation for “slow cinema”. Tarkovsky’s final film produced solely in the Soviet Union is a deeply introspective work, bewildering in the best way, always astonishing.

In an unnamed country, the “Stalker” (Alexander Kaidanovsky) sneaks people into a place known as the Zone. The Zone, bereft of human residents, is heavily guarded along its outer perimeter, but the police and military dare not enter it. One day, the Stalker – shown to be living in poverty with children, and urged by his wife (Alisa Freindlich) not to leave – has agreed to guide the “Writer” (Antoly Solonitsyn) and the “Professor” (Nikolai Grinko) to the Zone.

The laws of physics and time do not apply in the Zone. And it is rumored that, somewhere in the Zone, there is a “Room” that grants the innermost wishes of anyone who steps foot inside. The reasons for a guide are many: the straightest path will result in certain death, any routes that once led to the Room become impassable because geography can change in a matter of minutes, and the Zone’s innumerable traps (mental and physical) can only be sensed and never seen. Depending on the viewer’s interpretation, the Zone and/or the Room may be sentient. The Stalker demands that the Writer and Professor obey his orders. During their journey, they talk about their motivations for finding the Room. The Writer has lost his artistic inspiration, the Professor reveals a nebulous desire for scientific analysis, and the Stalker – who says he does not wish to use the Room – does not reveal his intentions for guiding others through the Zone until the final minutes.

There are no villains or monsters, spectacular special effects, or anything that one might expect from a science-fiction film. This is Tarkovsky’s second science-fiction work after Solaris (1972) – a space story that analyzed the essence of love when it collides with questions of experienced reality (Solaris is a rejection of what Tarkovsky believed to be Western sci-fi’s coldness, as embodied in 2001: A Space Odyssey) – but Stalker is almost nothing like that earlier film. This film is only considered science-fiction because of the physical impossibilities of the Zone, not because of any space travel or futuristic technologies. In a development I had never considered for a science-fiction film, almost none of the questions that Stalker poses to the audience have anything to do with science or technology. While recognizing that the greatest science-fiction works examine the nature of humanity, all the science-fiction media I had consumed prior to seeing Stalker contained elements of how humanity intersects with science and technology. This relationship is almost, if not non-existent in Stalker, appearing only at the conclusion. Stalker is entirely interested in the hearts and minds of the three leads – what they are subjected to while traversing the Zone, however disturbing, does not influence the people they are and the final decisions they will make. The Room is only a projection of their humanity; it does not shape who they are. This is reinforced by the Stalker’s true introductory words upon entering the Zone:

Our moods, our thoughts, our emotions, our feelings can bring about change here. And we are in no condition to comprehend them... everything that happens here depends on us, not on the Zone.

Loosely adapted from Arkadi and Boris Strugatsky’s intricate novel Roadside Picnic (Arkadi and Boris were brothers and co-wrote the adapted screenplay), Tarkovsky simplified what he could for the big screen. This meant compositing multiple characters into the three primary characters for the film and trimming down several years of excursions into the Zone down to a single sojourn. Interference from the Soviet censors and the accidental destruction of the original negatives at the film processing laboratory necessitated the introduction of intertitles announcing a first and second part. Episodes of state interference frustrated Tarkovsky as well (the censors did not request as many changes in Stalker compared to previous Tarkovsky films, but they could not tolerate narrative ambiguity of any sort, even if they could not find any specific anti-communist themes), who was forced to shoot almost the entire film three separate times, and led to him looking towards the West for work. It is the third and last effort that is available to audiences today.

With all these compromises and production nightmares, Tarkovsky was given multiple opportunities to make the best possible film he could. Production difficulties also meant Alexander Knyazhinsky became principal cinematographer over Leonid Kalashnikov (1969′s The Red Tent), who himself replaced another cinematographer before that. One of Knyazhinsky’s decisions mirrors The Wizard of Oz (1939) – the opening scenes are shot in sepia and all scenes in the Zone are shot in color. In entering the Zone, Knyazhinsky and Tarkovsky allow for an extended tracking shot that allows a glimpse into the uncertainty of the three men journeying to the Room:

youtube

This tracking shot sets the pace and tone for the remainder of the film (notice how the clacks of the wheels become indistinguishable from Tarkovsky regular Eduard Artemyev’s film score – the Azerbaijani tar is feature heavily, and the above instance will not be the last time rhythmic sound effects become inseparable from the music). Shot in Estonia, Stalker utilizes a lush, but lifeless landscape littered with human reminders of what life was like before the Zone was created. Wind is everywhere, even if the sound mix does not pick up on it. The grasses sway, the tree leaves rustle, and a low-lying fog brushes across the flora. Also omnipresent is water – whether on the grasses due to recent rains, flooded buildings, walkways turned into creeks, or deafening waterfalls. The second half’s interior scenes were shot at deserted hydro power plants already filled with fetid liquid and marked by years of abandonment (conditions were so poor that sound designer Vladimir Sharun believes chemical poisoning from these locations hastened the deaths of three crew members, including Tarkovsky). Almost suggestive of a post-apocalyptic world with industrial and military scrap strewn across the Zone, the effect is a serene suspense. The suspense, beginning with the above tracking shot, is cumulative. With death or separation possible at any turn, a slow walk to check for traps and a trip through a waterlogged pipe inspire interminable dread.

Amid this dread, what begins as a partnership defined by obeying the Stalker’s orders transforms into a series of bursts of overwhelming philosophy, ad hominem, poetry recitations from the mouth and mind (the poems used are by Fyodor Tyutchev and Tarkovsky’s father, Arseny), and rare instances of humor. The Stalker speaks of the Zone as a holy, perhaps partially sentient place not to be mistreated. The way he describes his work is not only to serve as a guide, but to offer a sort of deliverance (for himself? Those who hire him? The Zone?). Among these three, their initial intentions are not as they first appear. Cynicism and dismissive attitudes towards the Zone and the Room belie personal weakness and tragic character flaws. A front of altruism is stripped away, revealing exhausting fear, material desperation, spiritual emptiness. Just as important as what the Stalker, Writer, and Professor say to each other is what they do not say to each other – in Stalker, silent shots of the character’s faces say just as much as the philosophical soliloquies. This is outstanding acting from Kaidanovsky, Solonitsyn, and Grinko.

The film’s primary themes revolve around the subconscious and one’s deepest desires. Those desires are usually never the ones we speak about when questioned by others. Instead, they are the ones that reveal our most sinister, selfish urges – stripped of social constructs, morals, restraint, and the judgment rendered by even those closest to us. Or perhaps excursions through the Zone (failed and otherwise) and entrances into the Room grant something far more minatory: latent revelations and wishes which may never be understood.

Perhaps it is that pure expression and dogged pursuit of individualism which scared the Soviet Union. Indeed, Soviet science-fiction literature has a history of critiquing authoritarianism, communist and capitalist systems, and cults of personality. The self-understanding achieved in Stalker is not common in fiction or real life – the realities are deeply unpleasant, but not approached cynically. The realization of these realities provokes different responses from the characters: anger and anguish. Stalker, through its framing and narrative escalations, is evocative of classic horror films – where a dense, foreboding atmosphere is the source of the horror. The horror in Stalker includes the desolate locations it features, but most importantly the purposes of the three men who seek the Room.

Released to heavy criticism in the Soviet Union, contemporary opinion has been kinder to Stalker. Western critics compare the Heart of Darkness-esque narrative to Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. But Stalker has much more to say than Coppola’s film, preferring to examine its subjects for who they are and what they bring to their newfound surroundings rather than the reverse. Rather than Joseph Conrad, Tarkovsky takes his literary cues not only from the Strugatsky brothers, but also those giants of Russian literature: Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Without spoiling too much, the Stalker’s enterprise seems informed by the title character in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (Ivan Ilyich is a dying man pondering the nature of his death and, increasingly, his life’s meaning) while his characterization resembles the title character in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (whose epileptic bouts make people believe he is unintelligent, when he, despite being socially awkward, is anything but).

For first-time viewers, Stalker will baffle, enrage, and mystify. It should be viewed as cinematic poetry rather than a straight-laced narrative. This film conveys complicated ideas of desire and the changes resulting from desire that too few are receptive to. The few answers Stalker does provide are shrouded in its darkest corners, waiting to be discovered by those brave enough to present themselves and step forth. Do not expect anything flattering.

My rating: 10/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Stalker is the one hundred and forty-sixth film I have rated a ten on imdb.

#Stalker#Andrei Tarkovsky#Alexander Kaidanovsky#Anatoli Solonitsyn#Nikolai Grinko#Alisa Freindlich#Sergei Yakovlev#Natasha Abramova#Arkadi Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Alexander Knyazhinsky#Eduard Artemyev#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zone

Stalker (Сталкер)

1979

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematographer: Alexander Knyazhinsky

#Stalker#Сталкер#Andrei Tarkovsky#Tarkovsky#Alexander Knyazhinsky#Roadside Picnic#Strugatsky brothers#Arkady Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Strugatsky#zone#the zone#zona#sci-fi#sci fi#science fiction#russian#russian film#film#film gif#gif#gifset#cinematography

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Andrei Tarkovski, Сталкер, 1979

#film#Сталкер#stalker#Alexander Knyazhinsky#russian cinema#soviet union cinema#70's#film still#andrei tarkovsky

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stalker (1979), dir. Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography by Alexander Knyazhinsky and Leonid Kalashnikov

#stalker#andrei tarkovsky#russian cinema#cinematography#alexander knyazhinsk#leonid kalashnikov#screencaps#film

1 note

·

View note

Text

Andréi Tarkovsky

'Andréi Tarkovsky. Poetic harmony', Channel Criswell, 2016, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Andréi Tarkovsky’s cinematic candles', Kevin B. Lee, 2004, VO.

'Andréi Rublev', Andréi Tarkovsky, 1966. Making of VOSI.

'Andréi Tarkovsky & Sergei Parajanov: Islands', Ruben Gevorkyants, 1987, VO, SE en YouTube.

Presenta un conjunto de historias, retratos y fotos de gente con destinos increíbles, incluyendo ambos directores y fundiéndose en una imagen no tradicional y poco conocida de la República de Armenia.

'The island. Andréi Tarkovski', 2000, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Andréi Tarkovsky. A poet in the cinema', Donatella Baglivo, 1984, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Andréi Tarkovsky in Nostalghia', Donatella Baglivo, 1984, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Il cinema è un mosaico fatto di temp', Donatella Baglivo, 1984, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Directed by Andréi Tarkovsky', 1988, VO. ★ Vídeo.

'Andréi Tarkovski, poésie et vérité', 1999, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Sacrifices of Andréi Tarkovsky', 2012, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'The exile and death of Andréi Tarkovsky', 1988, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The reverse side of Stalker', 2009, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'On the scenography of Tarkovsky’s Sacrifice', Kerstin Eriksdotter, 1985, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Memories of Tarkovski by Michal Leszczylowski', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Mikhail Romadin on Solaris', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Eduard Artemiev about working on Solaris', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Eduard Artemiev on his work with Andréi Tarkovski', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Stalker. The zone of Andréi Tarkovski', 2007, VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Tarkovski & Bresson compilation', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

'Alexander Knyazhinsky on Stalker', VO, SE en YouTube.

youtube

‘La infancia de Iván’ ('Ivanovo detstvo’, 'Ivan’s childhood’, Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962), making of: 'Life as a dream’, 2007, VO.

‘Andréi Tarkovski shot by shot’, Antonios Papantoniou, 2015, VO.

02:52 Intro de Kris Kelvin y The Meeting.

07:50 Conversación de Anri Berton y Nik Kelvin.

11:55 Conversación de Anri Berton, Kris Kelvin y Nik Kelvin.

16:37 Conversación entre Kris Kelvin, Dr Sartorious, Dr Snaut y Khari.

vimeo

‘Tarkovsky cinema’, BBC, Arena, 1987, VO.

Especial de la BBC sobre Andréi Tarkovsky realizado unos meses después de su muerte, ofreciendo una particular visión de la historia del cineasta ruso y de cada una de sus obras.

Recorre a lo largo de casi una hora su filmografía, desde ‘Ivan’s Childhood’, 1962, incluyendo a ‘Solaris’, 1972, además de sus dos últimas películas rodadas fuera de la Unión Soviética, el documental ‘Voyage in time’, 1983, y ‘The sacrifice’, 1986.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stalker (1979)

Director - Andrei Tarkovsky, Cinematography - Alexander Knyazhinsky

“And there was a great earthquake. And the sun became black as sackcloth made of hair. And the moon became like blood… And the stars of the sky fell to the earth, as a fig tree casts its unripe figs when shaken by a great wind. And the sky was split apart like a scroll when it is rolled up. And every mountain and island were moved out of their places. And the kings of the earth and the great men and the rich and the chiliarchs and the strong and every free man, hid themselves in the caves and among the rocks of the mountains; and they said to the mountains and to the rocks, "Fall on us and hide us from the presence of Him who sits on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb, for the great day of His wrath has come, and who is able to stand?”

#scenesandscreens#Stalker#andrei tarkovsky#Alisa Freyndlikh#Aleksandr Kaydanovskiy#Anatoliy Solonitsyn#Nikolay Grinko

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

STALKER (1979)

Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography by Alexander Knyazhinsky

#stalker#andrei tarkovsky#alexander knyazhinsky#alexander kaidanovsky#anatoly solonitsyn#nikolai grinko#cinematography#movies#movie#films#film#raysofCINEMA

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zerkalo (Mirror)

1975

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematographer: Georgi Rerberg

Stalker (Сталкер)

1979

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematographer: Alexander Knyazhinsky

#Zerkalo#the Mirror#mirror#Andrei Tarkovsky#Tarkovsky#Stalker#Сталкер#fire#flames#flame#warmth#warm#film#film gif#gif#movie#movies#films#cinematography#russian#russian film#cinema#russian cinema

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5 notes

·

View notes