#Arkadi Strugatsky

Text

Dave McKean’s illustrations for Arkady & Boris Strugatsky‘s Roadside Picnic.

#dave mckean#arkady strugatsky#boris strugatsky#strugatsky brothers#russian literature#roadside picnic#stalker

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

#roadside picnic#arkady strugatsky#boris strugatsky#science fiction#book poll#have you read this book poll#polls

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

vote yes if you have finished the entire book.

vote no if you have not finished the entire book.

(faq · submit a book)

#Пикник на обочине#Roadside Picnic#Аркадий Стругацкий#Arkady Strugatsky#Борис Стругацкий#Boris Strugatsky#scifi#books#poll#l: Russian#result: no

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrei Tarkovsky on the set of Stalker, 1979.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strugatsky brothers... Strugatsky brotherrrrrs my beloved

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

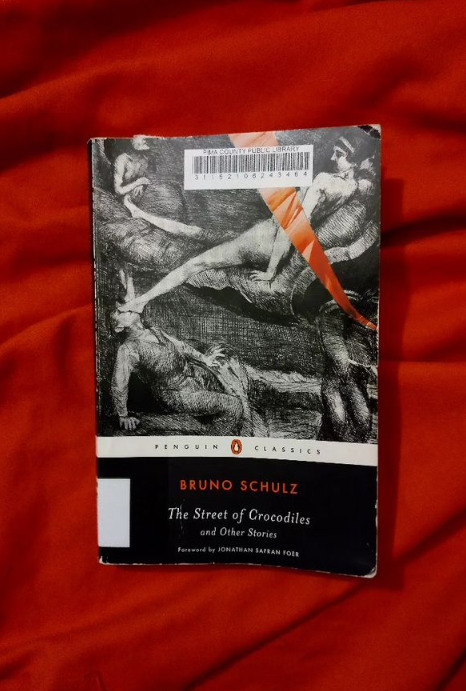

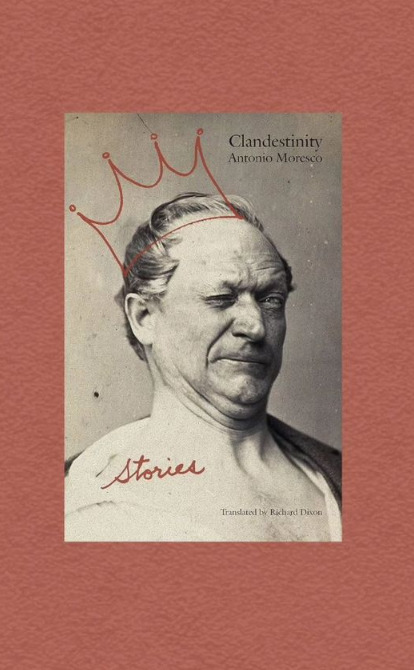

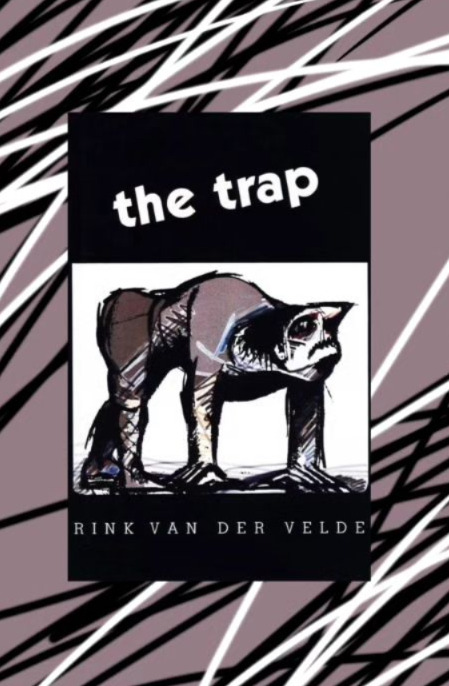

Books 11-20 of the year 📖

#read in 2024#ivan turgenev#mircea cartarescu#arkady strugatsky#boris strugatsky#laurent binet#bruno schulz#rink van der velde#edouard leve#antonio moresco#andrzej stasiuk#roque larraquy#talks

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

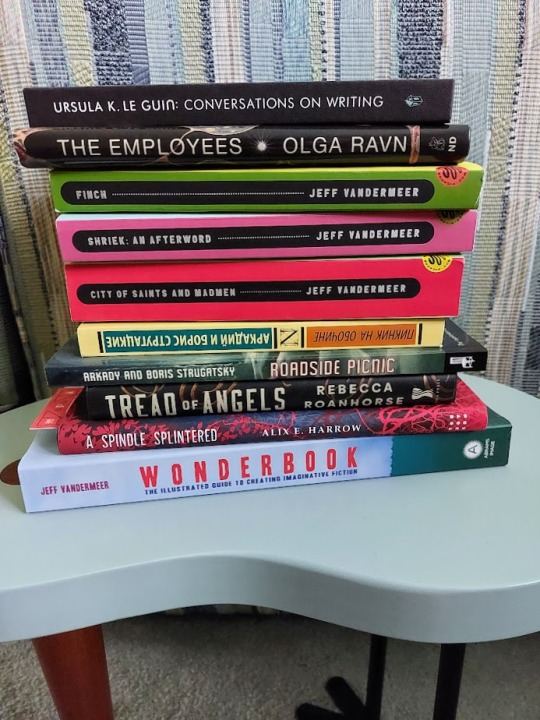

Book Haul: May Edition! My indie bookstore purchases started to show up this month, and it was my birthday, and I asked for books!! My ~Driscoll Vibes~ TBR has been replenished for sure (and just in time, too).

#books#my photography#book photography#book mail#book haul#wonderbook#city of saints and madmen#shriek: an afterword#finch#jeff vandermeer#a spindle splintered#alix e. harrow#roadside picnic#arkady and boris strugatsky#strugatsky#(yes the book right above the english version is the original russian!!)#tread of angels#rebecca roanhorse#the employees#olga ravn#ursula k le guin: conversations on writing#ursula k. le guin#i love getting books i love book mail *sobbing moji*#i'm gonna need SO MANY MORE BOOKSHELVES#no clue how many#(this is the hazard of buying books for three years without seeing how much shelf space you're filling lmao

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

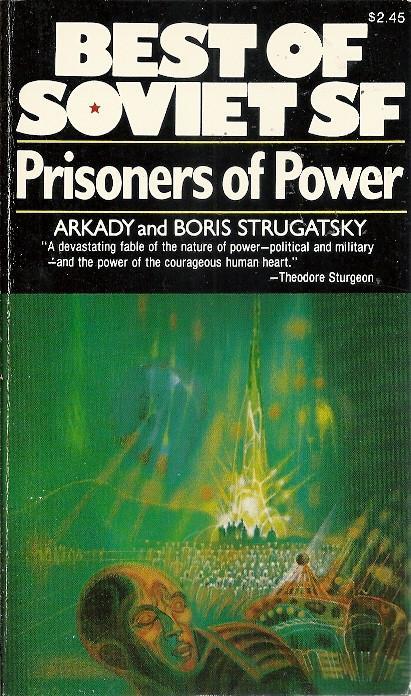

Vintage Paperback - Best Of Soviet SF: Prisoners Of Power by Arkady And Boris Strugatsky

Collier (1978)

#Paperback#Paperbacks#Science Fiction#Soviet Union#Paperback Cover#Arkady Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Vintage#Art#USSR#Collier#1978#1970s#70s

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

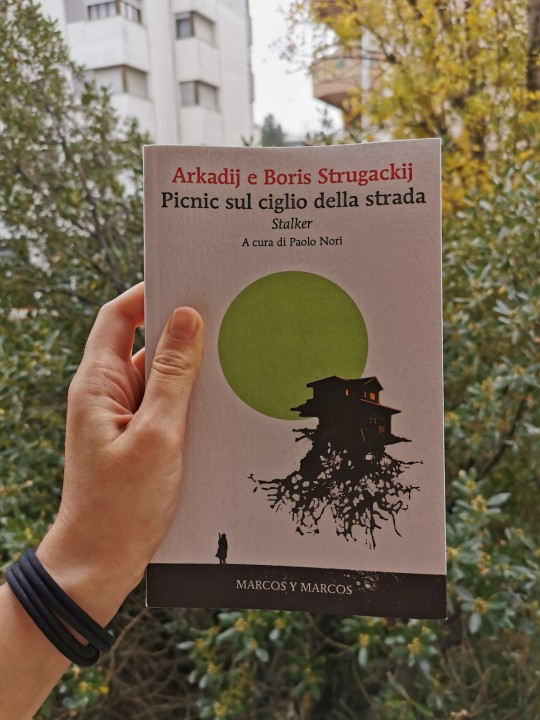

book I finished / book I started / book I saw in a little free library

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps the reason why I feel so emotionally attached to the variety of fantasy- and science fiction subgenres lies in the allegorical nature of fantasy and fiction itself. My ancestry comes from a country where freedom of speech has never truly existed: criticizing certain historical figures and events could get you in trouble at best and in jail at worst.

But as soon as a corrupted politician gets a pair of pointy ears, a magical sword and a pet dragon, as soon as we replace the tyrant's oprichniks with horde of green-skinned monsters, as soon as we call it a planet Saraksh instead of USSR, certain people magically go blind and scrap these books as something not worthy of their attention. Attention so unwanted that the authors keep doing this magical trick on purpose.

No one ever openly admitted that the book they wrote was satiric by its nature, but the certain level of irony and satire is always there. As you carefully read through the pages you keep asking yourself whether or not that is your imagination or is this book truly a social commentary. You just read some random soviet science-fiction and suddenly you break out in a cold sweat because all the bizarre stuff, all the characters and all the events either existed in the past or are existing and happening right now – but under other names.

And then you randomly bump into a small note an author wrote for a small local paper a few decades after the book is published and realize that it truly was a satire all along.

#thoughts on fiction#i love fantazy#soviet literature#russian literature#fiction#fantasy#i love satiric fantasy so much#i recommend you arkady and boris strugatsky#please read their books they are like insanely good#the stalker games were inspired by their book picnic on the roadside

108 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dave McKean’s illustrations for Arkady & Boris Strugatsky‘s Roadside Picnic.

#dave mckean#arkady strugatsky#boris strugatsky#strugatsky brothers#roadside picnic#russian literature

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

If anyone's looking for a good movie to watch, here's the trailer for Stalker from 1979. Based off the 1972 novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, it's a Soviet sci-fi movie about a character known only as "The Stalker", who ferries people to a restricted area known as the "Exclusion Zone", where there is a room that supposedly grants people their deepest desires. It was also the inspiration for the video game S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl.

#Stalker#Roadside Picnic#Arkady and Boris Strugatsky#Andrei Tarkovsky#movies#films#science fiction#sci-fi#sci-fi movies#sci-fi films#Soviet cinema#Soviet movies#Soviet films#S.T.A.L.K.E.R.#S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl#exclusion zone#Support Ukraine#Stand with Ukraine#Russia must burn#70s movies#70s film#70s films#Сталкер#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

vote yes if you have finished the entire book.

vote no if you have not finished the entire book.

(faq · submit a book)

#Хищные вещи века#The Final Circle of Paradise#Arkady Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Аркадий Стругацкий#Борис Стругацкий#scifi#books#poll#l: Russian

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 26, 2023

I was so happy about how the pics had turned out, that I took an enthusiastic sip right after – forgetting I had literally just taken the tea out of the stove. Oh well. Although I didn't feel particularly good today, I've achieved a lot – making masala chai, cleaning my room, studying Germanic Philology, and, most importantly, finishing the second book of the year: Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. It's an amazing read, that made me discover the true potential of the science fiction genre. I'm still trying to put all my admiration for this work into words, in a well deserved 4.75⭐ review.

#bookblr#books#book aesthetic#roadside picnic#Arkady Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#strugatsky brothers#book recs#science fiction#soviet literature#reading#light academia#readblr#study blog#studyspo#study motivation#my teas#masala chai#teablr#uni student#uni life#uniblr#studyblr#studying#2023 books#reading aesthetic

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 19, 1980, Stalker debuted in the Soviet Union.

Here's a new punk patch design inspired by the film's Japanese poster typography!

#stalker#stalker 1979#andrei tarkovsky#roadside picnic#boris strugatsky#arkady strugatsky#dystopian science fiction#dystopian film#soviet art#soviet cinema#soviet film#japanese#typography#punk patches#stencil#science fiction movies#science fiction#sci fi movies#sci fi#sci fi and fantasy#sci fi art#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#soviet union

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Strugatsky brothers: general notes on style and storytelling

Heya. If you want something to disagree with right out of the gate, here’s my tier list:

Ok, but seriously, I'm about halfway through the whole Strugatsky bros bibliography, and it's been kinda hit-or-miss. Some books are fantastic in terms of both storytelling and themes, some are a bit confusing and start very slow, but stick the landing with the drama and philosophy kicking into high-gear towards the end, and others are just... meh.

Anyway, here’s a loose, disorganised list of things I’ve noticed:

1) The Strugatsky's style of narration feels a tad homogenous after a while. Their POV character is usually a pragmatic, goal oriented man, intelligent enough to analyse themselves and the world around them, and often cynical to the point of distrusting simple, comforting narratives (voicing their scepticism through dry wit or sarcasm). The main variation seems to be in the protagonist's level of refinement vs. crudeness (some of them have a short fuse and poor manners), and how much they are motivated by a sense of duty vs. self-interest. The other character archetype they sometimes do is the "inexperienced young man with ambition and spunk" ("Space Apprentice", "Monday Begins on Saturday"). Yet there's some crossover - Sasha from "Monday" often shifts between bewildered novice and confident snarker, depending on the scene - and it all still "sounds" quite similar. I guess you could say this is their authorial voice - the "Strugatsky style", if you will - but to me, it makes reading their books back-to-back feel a bit... same-y.

2) Mystery is everywhere. Im surprised the Strugatskys only wrote one detective novel (which kind of turned out not to be a detective novel anyway), when tons of their works start with some inexplicable, mysterious event which then goes on to be gradually unravelled. I mean, half of "The Waves Extinguish the Wind" is just reports from an investigation into the motives of a mysterious alien species. "Beetle in the Anthill" is one long hunt for a mysterious fugitive, gradually finding out who they are and why they're so dangerous, and "The Final Circle of Paradise" is about busting a crime ring peddling a new, mysterious drug. But even when it’s not explicitly about detectives or investigations, they still often focus on an unexplained event or series of events ("Space Mowgli", "One Million Years to the End of the World").

A lot of the appeal which keeps the stories engaging for me is that they either set up a big question and slowly reveal pieces of the answer, or set up a lot of small questions that get much quicker answers, which then lead to more questions (sometimes both). In one case, they even nested a mystery within a mystery! “Beetle in the Anthill” is both a question of “where is Lev Aboukin hiding and what is his next move” and “who is Lev Aboukin and why was I ordered to track him down”?

Maybe this mystery focus is just part of the wider space fantasy sci-fi genre. Alien contact, phenomena beyond our understanding... these are very conducive to mystery; A few other sci-fi authors I've read have very similar set-ups. Well, whatever it is - authorial style or genre trope - I love it. It gives stories this feeling of discovery and learning, often with only half-satisfying conclusions that leave room for interpretation and reflection.

3) Holy shit, their representation of women is (mostly) terrible. I've heard a few people call the Strugatskys' writing misogynistic, and while I was sceptical at first (Guta from "Roadside Picnic" struck me as pretty cool and strong), after reading more, I definitely see it now. Most of the time, they depict women as trivial side characters, love interests for the protagonist, or worse, symbols of promiscuity, decadence and stupidity. I could maybe argue that some of these portrayals are more nuanced than it would first seem, but others are just... blegh.

A handful of their works ("Space Mowgli", "Monday Beings on Saturday" and "Space Apprentice") show women working alongside men as equals - suggesting some progressive ideals. "Space Apprentice" even has one chapter where they take down Shershen - a controlling, misogynistic professor who tries to sabotage his female student's career because he doens’t think women should work in space.

But none of this counters the causal sexism displayed generally, even in these seemingly positive examples. Stella's introductory scene from "Monday Begins on Saturday" shows her cowering in fear from Vybegallo's upiór, screaming hysterically. While she goes on to be much cooler in Story 3 of that book, she's still a rather lowly employee of the institute - not as experienced as the magisters (who are, you guessed it, all men).

Maya Glumova in "Space Mowgli" - the female character with perhaps the most screen time and agency from everything I've read so far - is still hinted to be more emotional and motherly towards the alien which the team discovers. So even when the female character is important and actively participates in the plot, she is partially defined by her femininity. And when she comes back in "Beetle in the Anthill", she's basically just a childhood love interest, acting as another clue to the mystery of Lev Aboukin's identity.

Natasha from "Space Apprentice" is the only time I've seen the Strugatskys write from a female POV, and even so, it only lasts two chapters, with her being completely irrelevant for the rest of the story. For the short while we get to see from her perspective, she mostly sits around and listens to other people, rarely taking the initiative to do anything. Some of her scenes feel like they could be commentary on workplace sexism, but they're too short and fleeting for the message to read clearly.

All these baby steps towards decent female representation are even harder to appreciate when you consider... everything else. Most egregiously, some visual descriptions of female characters are just gross, focusing on the lips, curves and skin in a very sexualised way. At first I thought that maybe this was a condemnation of the POV character, showing that we're following a crass, tactless protagonist who isn't above ogling someone they find attractive; a contemptible person who doesn't reflect the opinions of the authors. But without clear textual elements criticising this creepy behaviour, it really feels like it's being treated as normal, which... no, it really, really shouldn't be. At least the Strugatskys had the decency not to use this kind of sexualised, beauty-obsessed language when describing the aforementioned respectable worker women - Stella, Maya and Natasha.

On two occasions, women are shown arguing in favour of shallow, self-interested hedonism - an ideological foil to our responsible, socially-minded male protagonists. While this is a fine direction to take a character (and some male characters are criticised in a similar way - mostly in "The Final Circle of Paradise", where hedonism is a central theme), it feels like a waste to use an already small female presence as fodder for this philosophical debate.

So yeah, even though I love these stories, my appreciation is heavily dampened anytime a female character is introduced and turns out to be underutilised and irrelevant (which is disappointing), some dumb bimbo for the protagonist to sexualise (which is cringe), or a proxy for an ideology the Strugatskys want to criticise (which is disappointing).

4) Bromance! While the Strugatskys’ depictions of relationships between men and their female love interests are rather underdeveloped (a side effect of women having so little prominence, I think), the way they write emotional relationships between men and men is quite amazing. Most of these stories are brimming with a sense of camraderie and emotional closeness, with the male characters inspiring each other, guiding each other, criticising each other, learning from each other, etc. My three favourite dynamics have to be from "The Inhabited Island", "Space Apprentice" and "Monday Begins on Saturday".

In "The Inhabited Island", Maxim manages to gradually deprogram Guy from his nationalistic, fascist ideology by just being there, acting kind and showing him that an alternative way of thinking is possible. He points out inconsistencies in the government’s propaganda in a non-confrontational, innocuous way. Then, we see Guy's inner conflict when Maxim defects from the military and joins the resistance - having to view this close friend as a "traitor", despite having a lingering affection for him. And when Maxim finally gets Guy to defect and join his side, this affection is twisted into something monstrous and horrifying in a scene that I dare not spoil. It's an emotional roller-coaster, that one.

"Space Apprentice" has an interesting tension between two role models. Young Yura Borodin, despite his somewhat mundane job as a space welder, is eager to travel the stars and self-actualise. He's hungry for action, and would rather die than retire. Due to unfortunate circumstances, he's unable to catch his flight for the planet Rhea, and has to join the crew of another ship as a trainee (kinda like hitch-hiking, but in space, haha). He ends up under the supervision of Yurkovsky and Ivan Zhilin, both of which try to impart different lessons onto him. Yurkovsky is the embodiment of Yura's ideal - a world-renowned planetologist past his prime, still yearning for exciting work and hoping to make the "discovery of his lifetime". Zhilin is the ship's engineer, and has a far more cautious, protective attitude. Both of them like Yura's youthful enthusiasm, but while the former encourages his ambition and adventurous spirit, the latter tries to temper his expectations and teach him about responsibility. The stops along their route form a series of unrelated vignettes where we see the two philosophies in practice, and the ending resolves this tension in a really beautiful, heart-wrenching way.

"Monday Begins on Saturday" is just one huge "me and the boys" meme and I fuckin' love it. We have the confused yet curious newbie, Sasha Privalov, the measured and wise mentor figure, Roman Oira-Oira, the talented but rude snarker and critic, Vitya Korneev (who is still affectionate in his own way - he doesn't actually hate people, just enjoys banter), and the polite and helpful sidekick, Edik Amperian (+ a whole bunch of other colourful characters). The shenanigans these lads get up to are just a wonderful romp, as they juggle their own eccentricities and the absurd bureaucracy of a magical Soviet institute. Despite the chaotic nature of their work, often wrought with disagreement and a lack of resources, everything has this undercurrent of mutual respect and affection. I swear, this book has the most idyllic workplace culture I've ever seen, to the point that it makes it actually fun to read about office politics.

5) They start in medias res and fill the gaps with natural-sounding exposition. This is one of the core things that I believe makes the pacing of (most) Strugatsky novels feel very brisk. Characters are dropped into already unfolding situations - no lengthy backstories or elaborate speeches about the history of the world. Flashbacks are relatively rare and often contextualised (some focal point prompts the memory, making for a smoother transition). The majority of what we learn about characters comes from clues in their speech, thoughts and actions. Same applies to the world - details are drip-fed to you as they become relevant.

That's not to say that the Strugatskys never drop exposition dumps on the audience, but it's less common, and even then, is usually done intelligently. Most often, a character will see something and, in the process of expressing their opinion, bring up background details that show how they feel about it - we get both world-buiding and characterisation at the same time.

An even better way they disguise exposition dumps is by having characters casually debate something - in a moment of respite from the action, they sit together and bounce arguments back and forth: “is X thing ethical”, “what would happen if Y”, “these Z activists are starting to get on my nerves”, etc. As they make their points, they bring up examples, facts, anecdotes, and very quickly, not only do we know what they believe, but also learn about a whole bunch of things that exist or happened, all while never being explicitly told.

This is probably the best lesson you can learn from the Strugatskys - if your setting has interesting elements, either show them directly in the action of the story, or make them a talking point which characters have conflicting opinions on (better yet, do both - the Zone in “Roadside Picnic” is a masterclass in being a springboard for both characters and plot). If not, don’t bother - you’ll just distract the audience with pointless guff.

* * *

That’s about it. I could probably go on, but I’m too tired to continue writing. I’d love to pick apart more specific examples of points 2), 4) and 5), so maybe I’ll make separate posts for them in the future (lemme know if that’s something you’d be interested in). Mostly, though, I'm desperate to find other people as obsessed with the Strugatskys as I am and discuss their lesser known works. I personally feel that "The Final Circle of Paradise" is a hidden gem of theirs, one that has flown under the pop-culture radar but is well worth discussing.

Peace.

#Strugatsky brothers#Arkady Strugatsky#Boris Strugatsky#Strugatskys#My writing#Roadside Picnic#Monday Begins on Saturday#The Final Circle of Paradise#The Inhabited Island#Prisoners of Power#Space Apprentice#Beetle in the Anthill

16 notes

·

View notes