#Anglo-saxons

Text

In 1931, a scholar named Bernhard Bischoff decoded a cypher placed between two saints’ lives in an early ninth-century manuscript from Eichstätt, Germany. The lives were written about Saints Willibald and Winnebald, two English brothers who in the eighth century became, respectively, the Bishop of Eichstätt and Abbott of Heidenheim, both in the modern day region of Bavaria.

The cypher reads:

Secundumgquartum quintumnprimum sprimumxquartumntertium cprimum nquartummtertiumnsecundum hquintumgsecundum bquintumrc quartumrdinando hsecundumc scrtertium bsecundumbprimumm

Bischoff worked out that all vowels had been replaced by ordinal numbers - ‘second, g, fourth, fifth, n, first, s…’ and so on. Each of these numbers could be replaced with the corresponding vowel, to make the Latin sentence:

Ego una Saxonica nomine Hugeburc ordinando hec scribebam

I, a Saxon nun called Hugeburc, have written this

...

Hugeburc is the earliest known English woman author of a full-text literary work.

623 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an incredible find that links us back to the mysteries of early medieval England, researchers may have finally located the burial site of Anglo-Saxon King Cerdic, the legendary founder of the Kingdom of Wessex! Known from tales as ancient as the legends of King Arthur, Cerdic's story is a fascinating blend of warfare and leadership in post-Roman Britain.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"According to the Life of King Edward, which she commissioned herself, [Edith of Wessex] was as close to perfection as could be imagined: beautiful, intelligent, articulate, affectionate, honest, artistic, generous and (self-evidently) modest."

-Marc Morris, "Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England, 400-1066"

#cackling#I need a docudrama on her right now#edith of wessex#anglo-saxons#historicwomendaily#11th century#my post#queue

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Anglo-Saxon chronicler Bede gave us this simple explanation for the name of the festival.

"Eostremonath has a name which is now called Paschal month, and which was once named after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, and in her honour feasts were held in that month. Now they name the Paschal season by her name, calling the joy of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old rite."

Nothing else is known about Eostre, although Jacob Grimm did speculate that the old German name Ostara was probably her cognate. He was trying to work backwards from traditions he saw in his time and it was only a theory, but it would be logical to assume a connection with Eostre in the lands the Anglo-Saxons originated from.

Eggs and bunnies are not connected in any way to Eostre, these traditions come about much later on and within a Christian context. Eggs were prohibited during Lent so people would have had a glut of them to use at Easter, and I have no doubt lots of them were painted and blessed for the occasion. The Easter bunny was always a hare, never a rabbit, and hopped out of the mists of 17th century German Lutheran folklore. During the Medieval era it was also commonly believed that hares could impregnate themselves, leading to an association with Mary.

So here's a medieval Easter bunny, a 14th century carving of a hare at, you guessed it, the Church of St Mary, at Elmley Castle in Worcestershire. Have a great Easter!

~ Hugh Williams

On another note:

"There is simply no evidence for this commonly repeated myth.

It’s not factually true and is simply speculation by one monk in 725.

There is no evidence that he was correct about this. There are no references or images of Eostre anywhere else or in anything else at all. He also documents Woden and Thor, but they are verified as deities that were worshiped, but not so with Eostre. In fact it appears to be far more probable that the name of the lunar month Eosturmonath is actually a reference to “the month of opening” for the rather obvious reason that it is springtime.

When it comes to this goddess, we have no images, no carvings and no legends, just this single reference by Bede that appears to be speculation, and so that is why most folklorists will dismiss the assertion that Easter is named after the goddess Eostre as a myth.

Ronald Hutton, expert in pre-Christian religion, argues that:

"It is equally valid, however, to suggest that the Anglo-Saxon ‘Estor-monath’ simply meant ‘the month of opening’ or ‘the month of beginnings’, and that Bede mistakenly connected it with a goddess who either never existed at all, or was never associated with a particular season but merely, like Eos and Aurora, with the dawn itself.’3"

Hard to find a better source than Prof Hutton."

~ Matt Lewis

and this link for further reading:

https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-pagan-goddess-behind-the-holiday-of-easter/?fbclid=IwAR2IhpTsPjt0pMkSyyR0w4COXVI3d3QCSzVA6bGzTH1sYWgDAsuctNIrpaw_aem_AbAxlLoqWL9_Hf4CqCBG3mcZ8C_jut9RiJ6rl_5cGae-d0HHJMpMQ0NmAQsYgZkITXjnee-AcUwFAHZAqf_6rtGF

#Ostara#Hare#Tis The Season#Wheel of the Year#Paschal#Eostre#Anglo-Saxons#eggs#Easter#traditions#ancient ways#sacred ways#easter bunny#folklore#folkways#medieval#14th century carving#Church of St Mary#Elmley Castle#Worcestershire#England#United Kingdom#Ancestors Alive!#What is Remembered Lives#Memory & Spirit of Place#Bede#Anglo-Saxon Chronicles#Professor Ronald Hutton#Professor Hutton#Ronald Hutton

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in 878, the Battle of Edington: Alfred the Great and his West Saxon army defeat Viking army of Guthrum the Old.

This scene represents an attempt to instil weapon skills in a group of the Wessex fyrd during the reign of Alfred the Great. The seated monarch views the efforts of two warriors hurling javelins. The warriors are all men of the same hundred (an administrative sub-division of a shire), and will march together on campaign, and in battle will serve in the unit commanded by their shire- reeve who stands at the left hand of the king. Tents provided shelter for Anglo-Saxon warriors during musters and when on campaign. The basic structure of an Anglo-Saxon tent seems to have been similar to that of a modern ridge tent. The warriors are not fully equipped for battle but rather are dressed in long-sleeved Anglo-Saxon tunics, and tight leggings which are probably similar to the hose of the later medieval period.

Artwork by Gerry Embleton from the book 'Anglo-Saxon Thegn AD 449–1066.'

37 notes

·

View notes

Link

More accurate, less click-baity title: “Yes, the Anglo-Saxon Invasion of Britain Really Did Happen.” Which it did...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miniature depicting the Battle of Hastings and Harold’s body being carried to Waltham Abbey, from the Grande Chronique de Normandie, Brussels, c. 1460–1468, Yates Thompson MS 33, f.167r

#battle of Hastings#Harold II of England#William of Normandy#Anglo-Saxons#Anglo-Saxon England#Harold II#Harald II#medieval England

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

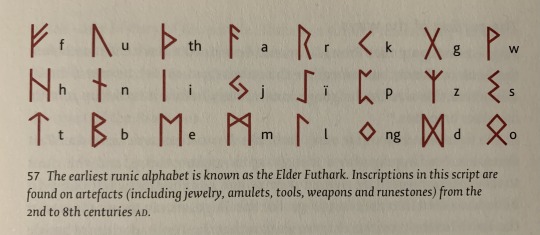

Elder Futhark: The earliest runes

The earliest runic alphabet is known as Elder Futhark. Here's what it looked like!

Note the letters thorn ⟨þ⟩ and wynn ⟨Ƿ⟩ for the "th" /θ/ and "w" sounds, which continued to be used when writing English in the Roman alphabet for centuries after.

The name futhark comes from the names of the first six letters of the writing system, just like the name alphabet comes from the names of the first two letters of the Greek alphabet (alpha and beta).

Do you notice how some of the letters look similar to their equivalent in the Roman alphabet? That's because Elder Futhark derives from the Old Italic scripts—some of the earliest writing to come to the Italian peninsula, used to write Etruscan and later Latin. (Check out what the Old Italic scripts looked like here and here.)

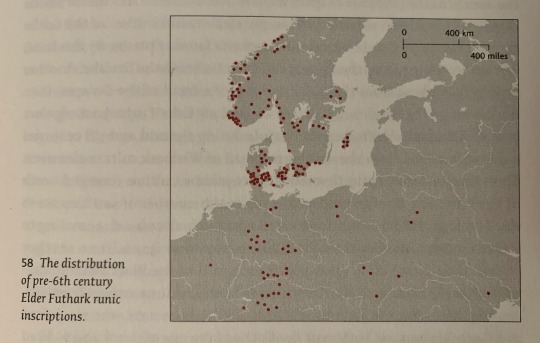

Finally, here's a map of all the known Elder Futhark runic inscriptions from before 500 CE:

(The above images come from the book The origins of the Anglo-Saxons: Decoding the ancestry of the English, by Jean Manco. I've only just started reading it, but so far I'd highly recommend it!)

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

American Progress by John Gast, 1872.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Anglo-Saxon beaver tooth amulet discovered at the Wigber Low burial site in Derbyshire.

A 6th-century Anglo-Saxon riddle describes the beaver:

I am a dweller on the edge of steep stream banks, and not lazy at all, but warlike with the weapons of my mouth.

I sustain my life with hard labour, laying low huge trees with my hooked axes.

I dive into water, where the fish swim, and immerse my own head, wetting it in the watery surge.

The wounds of sinews and limbs foul of gore I can cure. I destroy pestilence and the deadly plague. I eat the bitter and well-gnawed bark of trees.

The Eurasian Beaver was hunted to extinction in Britain by the 16th century; since 2009, there has been an ongoing project to reintroduce them in Scotland.

#no idea there'd ever been beaver in Europe#no wonder they were so stoked to find more to kill in the New World#shiny objects#anglo-saxons#archaeology

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Hastings in 1066 was a pivotal moment in English history. The Norman’s victory led to massive societal and cultural changes, shaping the nation for centuries to come.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A tyrant after the manner of her father."

As one of the children of Offa of Mercia and his celebrated queen Cynethryth, Eadburh inherited an elevated view of queenship. By the time of Eadburh’s marriage, the office of queen was developing into something more akin to the position recognised in the 973 Regularis Concordia, which recognised queens with their own anointing ceremony and made them, like the king, protectors of monastic houses. The queenship Eadburh had modelled to her in the person of her mother was influential, involved in the everyday running of the court, and possessed considerable independent power.

Eadburh’s marriage to Beorhtric does not usually crop up in discussions of conventional peaceweaving marriages because she is most usually considered in terms of political biases reacting poorly against women: her story is recorded in a history written by the victors, in which she is both nemesis and victim. Nevertheless, when considered closely, her marriage does appear to fit the characteristics of a peaceweaving marriage. Her union with Beorhtric seems to have been intended to draw the two peoples more closely together, especially considering the adverse history between the two kingdoms.

The peaceweaving aspect of the marriage becomes more apparent when the considering the relationship between Offa and his son-in-law. Beorhtric’s succession to the West Saxon throne seems to have ushered in a spirit of cooperation between the two traditionally rival kingdoms. In 789, Offa banished Ecgberht, later king of Wessex, and the grandfather of King Alfred. Although he clearly also benefited from the removal of a rival for the throne, Beorhtric enforced this exile as well. There are no formal documents outlining what the relationship between Beorhtric and Offa constituted, although S.E. Kelly detects ‘some hint of subservience … betrayed in the three surviving charters of Beorhtric, where the royal styles are curiously humble and tentative’. Asser’s text similarly confirms the close political relationship between Offa and Beorhtric – which, according to traditions handed down by Ecgberht’s line, is attributed to Eadburh. Asser writes how Offa made the match: ‘Beorhtric, king of the West Saxons, received in marriage [Offa’s] daughter, called Eadburh. As soon as she had won the king’s friendship, and power throughout almost the entire kingdom, she began to behave like a tyrant after the manner of her father’ [...].

The account given by Alfred to Asser is designed to discredit Eadburh and explain why the office of queen had been abandoned in Wessex, and does so by undermining the wife of a dynastic rival. There is considerable bias in seeking to discredit both Beorhtric and Eadburh, but the account fails to conceal that Eadburh probably was, at least at first, a rather effective queen. Before her marriage, she had witnessed charters as the daughter of the king and queen of Mercia. To be able to muster power of the sort attributed to her suggests that she had good relationships: she won the friendship of the king, her most important relationship. For Eadburh to have power throughout the kingdom, she must have maintained a good relationship with her father and brother to protect her, but possibly also forged new relationships by a mixture of patronage and promoting their interests at court. These are skills she may have learned from her mother Cynethryth [.] [However, Cynethryth] had the distinct advantage of having a Mercian background herself, and as a result did not have to negotiate the difficult position of mediating between her natal family and identity and her status as queen of a different kingdom in quite the same way.

The West Saxon traditions handed on by Ecgberht’s descendants clearly blame Offa and his tyrannical ways for influencing his daughter’s practice of queenship [and indicates that she might have acted as ‘an active representative of Mercian interests at the West Saxon court', as Barbara York points out]. On closer consideration, Eadburh is far more likely to have emulated her mother’s practice. Unusually, Asser and Alfred ascribe Eadburh’s monstrous behaviour as deriving from her father’s model of kingship. Other texts tend to emphasise feminine monstrous and overly assertive behaviour, especially where Offa’s queen Cynethryth is concerned.

Misogynistic leanings influenced the way that both Cynethryth and her daughter Eadburh are portrayed. Traditions at St Albans blamed Cynethryth for the murder of Æthelberht, drawing on a biblical tradition associated with John the Baptist. It is hardly surprising, therefore, when Eadburh herself was blamed for the deaths of unnamed nobles as well as Beorhtric and a well-loved West Saxon noble, probably Worr, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 800 [...].

The accounts of Eadburh following the death of Beorhtric come solely from the West Saxon dynasty hostile to her husband and father, but other independent sources may corroborate certain details. The account of her behaviour at Charlemagne’s court in Asser’s text may contain some kernels of truth, but seems to be a wild attempt to further discredit Eadburh and her Mercian heritage. After her husband’s death, Eadburh fled with a quantity of treasure, which may have either been her own treasure, or the royal treasury. The West Saxon tradition states that Eadburh later sought refuge in Francia, where she came to Charlemagne’s court and was offered a choice of husbands – either Charlemagne, or one of his sons. In the story, Eadburh selfishly chose the younger option, and as punishment for her selfish choice, was given neither, but instead received a nunnery (V. Alfredi, c. 15). There is a kernel of truth at the core of this tradition: Offa and Charlemagne had been in negotiations for one of the Mercian princesses to wed to one of the Frankish king’s sons. The talks broke down, reportedly, because Offa insisted on a reciprocal Frankish princess bride for his son Ecgfrith. The attribution of Beorhtric’s death to Eadburh is difficult to either confirm or deny: Ealhflæd’s involvement in Peada’s death demonstrates that a queen could be involved in her husband’s death, and poison was a favoured accusation to use against unpopular queens from antiquity into the modern age*. The account contains yet one more kernel of truth: Eadburh’s geographic peregrinations. Asser’s account in Chapter 15 of his Life of Alfred records that Eadburh spent some time as an abbess in a Frankish abbey before being ejected for having an affair with one of her countrymen, and ended her life begging in Pavia. Janet Nelson’s analysis of this information points out that there are some reasons to believe Asser’s version: Frankish abbesses tended to be royal appointments, and an entry in the Reicheneau Liber Vitae has an ‘Eadburg’ who was abbess of a convent in Lombardy. Pavia was on the traditional pilgrimage route to Rome, which was popular with early English pilgrims. Eadburh’s continental peregrinations also fit with the developments in Mercia following her marriage. In 796, Offa died, leaving the throne to his son and heir Ecgfrith. Unfortunately, Ecgfrith passed away within months, ending the dynasty. With the passage of the throne to a relatively distant relative in Coenwulf, there was little to offer Eadburh on her return. Like Osthryth, the collapse of her family caused by the deaths of her nearest male relatives weakened her options to a delicate situation, thereby obliging her to seek assistance abroad.

Eadburh is vilified in the West Saxon sources as a wicked queen whose appetite for fame and power were her undoing. Because Offa helped drive Ecgberht from Wessex and into exile, the royal line descended from Ecgberht largely effaced the office of queen, recently expanded and abused by Offa’s daughter, from the way they ruled. Asser comments how the West Saxon kings following Ecgberht did not follow the custom of nominating the king’s wife as a queen as a response to Eadburh’s wickedness.He remarks on ‘the (wrongful) custom of that people … [f]or the West Saxons did not allow the queen to sit beside the king, nor indeed did they allow her to be called “queen”, but rather “king’s wife”.

Stefany Wragg, "Early English Queens, 650-850: Speculum Reginae"

*The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, when writing about Beorhtric's death in 802, makes no mention of any alleged treachery and/or poison on Eadburh's part. This is in sharp contrast to the way chronicles did almost unanimously emphasize the role of another queen - Ealhflæd - in the murder of her husband. It's possible, though unlikely, that Beorhtric may have simply died naturally. Alternatively, considering the death of his Mercian protector Offa just a few years before his death, considering that he was succeeded immediately by Ecgberht, an enemy he had exiled from the kingdom, and considering how there was apparently a battle between a Mercian and Wiltshire ealdorman on the same day Ecgberht ascended the throne (resulting in Mercian defeat), it's quite possible that the cause for Beorhtric's downfall was dynastic, and more akin to a traditional defeat or deposition, than any conveniently miscalculated treachery by his wife. In this context, Eadburh's sudden flight abroad with a quantity of treasure after his death resembles that of other queens who witnessed the downfall of their dynasties and had to flee to protect themselves.

#historicwomendaily#she and Seaxburh are the most interesting Anglo-Saxon queens to me for sure (though Ethelburh Aethelflaed and Edith of Wessex come close)#I want to do a separate post 'tracing' Eadburh and what we know of her + my own interpretation someday#but until then....here's this post#anglo-saxons#anglo-saxon england#eadburh#eadburh of wessex#english history#my post#queue

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Athelstan--Our Greatest Monarch?

Athelstan–Our Greatest Monarch?

A recent poll searching for Britain’s ‘Greatest Monarch’, came up with the surprise winner of… drum roll, King Athelstan. Not that the Anglo-Saxon king wasn’t so great, but the winner is a little surprising since most people seem to have believed the ‘crown’ would go to Elizabeth I. (Yawn!)

I hope the voters actually remembered Athelstan in reality and have not just recalled his name from…

View On WordPress

#"The last Kingdom"#Alfred#Anglo-Saxons#Athelstan#Bernard Cornwell#books#Brunaburh#Cheshire#Constantine II#Dissolution of the Monasteries#Eadgyth#Edward the Elder#Elizabeth I#Germany#House of Wessex#illegitimacy rumours#legal reforms#Malmesbury Abbey#novels#piety#royal burials#Scotland#St. Aldhelm#St. Cuthbert#Tom Holland#Venerable Bede#Vikings#York

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whether the Arthur of legend actually existed is the subject of much debate. Per the British Library’s Hetta Elizabeth Howes, historical records show that a man named Arthur led resistance against the Saxons and Jutes around the fifth and sixth centuries C.E.; some Welsh accounts reference a similarly gifted warlord. The king of modern myth, however, only began to take shape in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (1138).

Arthurian legends were widely shared throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, via manuscripts for the wealthy and oral storytelling for the broader population. Though earlier tellings emphasized Arthur’s strength in battle and nation-building skills, the tales eventually became part of the medieval romance tradition, wistfully yearning for a time of morality, chivalry and righteousness.

Arthur’s Stone was first linked to the mythical king prior to the 13th century, according to English Heritage. Its fame continued in the centuries that followed: Charles I camped in the area with his troops during the 17th-century English Civil Wars, and writer C. S. Lewis, who frequently walked by the site, based the Stone Table in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe on it.

— Archaeologists Begin First-Ever Excavation of Tomb Linked to King Arthur

#THIS IS SO COOL OMG#i had no idea that the stone table was based on this#or that there was actual evidence of king arthur having really existed#history#architecture#archaeology#folklore#books#c.s. lewis#narnia#neolithic#medieval#britain#england#anglo-saxons#arthur's stone (herefordshire)#king arthur#geoffrey of monmouth#charles i

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book of the Week: For Rapture of Ravens

Get an eBook copy now for 50% of the regular price!

Shop here: For Rapture of Ravens

Also available at :*

Amazon – Apple – Barnes & Noble – Kobo

*Discount prices offered with this promotion do not apply at the above stores

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Possibly Ragnar Lothbrok portrayed in medieval manuscripts, produced in the reign of Henry VI, King of England.

Following the order of the images above:

f. 39r, Lothbrok, king of Danes, with sons Hinguar and Hubba, worship idols.

f. 41v, Lothbrok boards a boat with hawk and hound to hunt; the boat is driven out to sea.

f. 42r, Lothbrok cast ashore in Norfolk; Lothbrok is received by Edmund.

f. 43v, Lothbrok hunts with falcon and lures; Lothbrok hunts with hound and stag.

f. 44r, Lothbrok murdered by Bern: his body hidden in bushes, hound beside.

f. 47v, Hinguar and Hubba set out to avenge their father's murder.

f. 48r, Hinguar and Hubba slay all Christians in the North and despoil the countryside.

f. 48v, People submit to Hinguar, beside burning city.

f. 50r, Battle scene: Edmund defeats Hinguar.

f. 52r, Hinguar sends messenger to Edmund.

#manuscripts#medieval England#middle ages#primary sources#vikings#ragnar lothbrok#hinguar#hubba#ubbe#ubbe lothbrok#st edmund#martyrdom#king edmund#anglo-saxons#house of wessex#danes#medieval Denmark

13 notes

·

View notes