#Author: AA Milne

Text

[ID Bluebell Woods near Arundel. Photographer: Charlie Waring]

[ID Close up of Bluebells. Photographer unknown.]

Where am I going?

I don't quite know.

What does it matter where people go?

Down to the wood where the bluebells grow -

Anywhere, anywhere.

I don't know.

- A. A. Milne

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

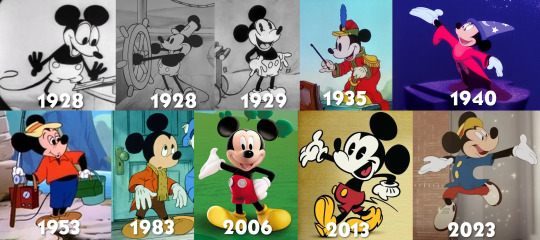

It all started with a mouse

For the public domain, time stopped in 1998, when the Sonny Bono Copyright Act froze copyright expirations for 20 years. In 2019, time started again, with a massive crop of works from 1923 returning to the public domain, free for all to use and adapt:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2019/

No one is better at conveying the power of the public domain than Jennifer Jenkins and James Boyle, who run the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain. For years leading up to 2019, the pair published an annual roundup of what we would have gotten from the public domain in a universe where the 1998 Act never passed. Since 2019, they've switched to celebrating what we're actually getting each year. Last year's was a banger:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/20/free-for-2023/#oy-canada

But while there's been moderate excitement at the publicdomainification of "Yes, We Have No Bananas," AA Milne's "Now We Are Six," and Sherlock Holmes, the main event that everyone's anticipated arrives on January 1, 2024, when Mickey Mouse enters the public domain.

The first appearance of Mickey Mouse was in 1928's Steamboat Willie. Disney was critical to the lobbying efforts that extended copyright in 1976 and again in 1998, so much so that the 1998 Act is sometimes called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act. Disney and its allies were so effective at securing these regulatory gifts that many people doubted that this day would ever come. Surely Disney would secure another retrospective copyright term extension before Jan 1, 2024. I had long arguments with comrades about this – people like Project Gutenberg founder Michael S Hart (RIP) were fatalistically certain the public domain would never come back.

But they were wrong. The public outrage over copyright term extensions came too late to stave off the slow-motion arson of the 1976 and 1998 Acts, but it was sufficient to keep a third extension away from the USA. Canada wasn't so lucky: Justin Trudeau let Trump bully him into taking 20 years' worth of works out of Canada's public domain in the revised NAFTA agreement, making swathes of works by living Canadian authors illegal at the stroke of a pen, in a gift to the distant descendants of long-dead foreign authors.

Now, with Mickey's liberation bare days away, there's a mounting sense of excitement and unease. Will Mickey actually be free? The answer is a resounding YES! (albeit with a few caveats). In a prelude to this year's public domain roundup, Jennifer Jenkins has published a full and delightful guide to The Mouse and IP from Jan 1 on:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/mickey/

Disney loves the public domain. Its best-loved works, from The Sorcerer's Apprentice to Sleeping Beauty, Pinnocchio to The Little Mermaid, are gorgeous, thoughtful, and lively reworkings of material from the public domain. Disney loves the public domain – we just wish it would share.

Disney loves copyright's other flexibilities, too, like fair use. Walt told the papers that he took his inspiration for Steamboat Willie from Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, making fair use of their performances to imbue Mickey with his mischief and derring do. Disney loves fair use – we just wish it would share.

Disney loves copyright's limitations. Steamboat Willie was inspired by Buster Keaton's silent film Steamboat Bill (titles aren't copyrightable). Disney loves copyright's limitations – we just wish it would share.

As Jenkins writes, Disney's relationship to copyright is wildly contradictory. It's the poster child for the public domain's power as a source of inspiration for worthy (and profitable) new works. It's also the chief villain in the impoverishment and near-extinction of the public domain. Truly, every pirate wants to be an admiral.

Disney's reliance on – and sabotage of – the public domain is ironic. Jenkins compares it to "an oil company relying on solar power to run its rigs." Come January 1, Disney will have to share.

Now, if you've heard anything about this, you've probably been told that Mickey isn't really entering the public domain. Between trademark claims and later copyrightable elements of Mickey's design, Mickey's status will be too complex to understand. That's totally wrong.

Jenkins illustrates the relationship between these three elements in (what else) a Mickey-shaped Venn diagram. Topline: you can use all the elements of Mickey that are present in Steamboat Willie, along with some elements that were added later, provided that you make it clear that your work isn't affiliated with Disney.

Let's unpack that. The copyrightable status of a character used to be vague and complex, but several high-profile cases have brought clarity to the question. The big one is Les Klinger's case against the Arthur Conan Doyle estate over Sherlock Holmes. That case established that when a character appears in both public domain and copyrighted works, the character is in the public domain, and you are "free to copy story elements from the public domain works":

https://freesherlock.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/klinger-order-on-motion-for-summary-judgment-c.pdf

This case was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, who declined to hear it. It's settled law.

So, which parts of Mickey aren't going into the public domain? Elements that came later: white gloves, color. But that doesn't mean you can't add different gloves, or different colorways. The idea of a eyes with pupils is not copyrightable – only the specific eyes that Disney added.

Other later elements that don't qualify for copyright: a squeaky mouse voice, being adorable, doing jaunty dances, etc. These are all generic characteristics of cartoon mice, and they're free for you to use. Jenkins is more cautious on whether you can give your Mickey red shorts. She judges that "a single, bright, primary color for an article of clothing does not meet the copyrightability threshold" but without settled law, you might wanna change the colors.

But what about trademark? For years, Disney has included a clip from Steamboat Willie at the start of each of its films. Many observers characterized this as a bid to create a de facto perpetual copyright, by making Steamboat Willie inescapably associated with products from Disney, weaving an impassable web of trademark tripwires around it.

But trademark doesn't prevent you from using Steamboat Willie. It only prevents you from misleading consumers "into thinking your work is produced or sponsored by Disney." Trademarks don't expire so long as they're in use, but uses that don't create confusion are fair game under trademark.

Copyrights and trademarks can overlap. Mickey Mouse is a copyrighted character, but he's also an indicator that a product or service is associated with Disney. While Mickey's copyright expires in a couple weeks, his trademark doesn't. What happens to an out-of-copyright work that is still a trademark?

Luckily for us, this is also a thoroughly settled case. As in, this question was resolved in a unanimous 2000 Supreme Court ruling, Dastar v. Twentieth Century Fox. A live trademark does not extend an expired copyright. As the Supremes said:

[This would] create a species of mutant copyright law that limits the public’s federal right to copy and to use expired copyrights.

This elaborates on the Ninth Circuit's 1996 Maljack Prods v Goodtimes Home Video Corp:

[Trademark][ cannot be used to circumvent copyright law. If material covered by copyright law has passed into the public domain, it cannot then be protected by the Lanham Act without rendering the Copyright Act a nullity.

Despite what you might have heard, there is no ambiguity here. Copyrights can't be extended through trademark. Period. Unanimous Supreme Court Decision. Boom. End of story. Done.

But even so, there are trademark considerations in how you use Steamboat Willie after Jan 1, but these considerations are about protecting the public, not Disney shareholders. Your uses can't be misleading. People who buy or view your Steamboat Willie media or products have to be totally clear that your work comes from you, not Disney.

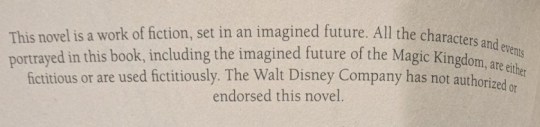

Avoiding confusion will be very hard for some uses, like plush toys, or short idents at the beginning of feature films. For most uses, though, a prominent disclaimer will suffice. The copyright page for my 2003 debut novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom contains this disclaimer:

This novel is a work of fiction, set in an imagined future. All the characters and events portrayed in this book, including the imagined future of the Magic Kingdom, are either fictitious or are used fictitiously. The Walt Disney Company has not authorized or endorsed this novel.

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250196385/downandoutinthemagickingdom

Here's the Ninth Circuit again:

When a public domain work is copied, along with its title, there is little likelihood of confusion when even the most minimal steps are taken to distinguish the publisher of the original from that of the copy. The public is receiving just what it believes it is receiving—the work with which the title has become associated. The public is not only unharmed, it is unconfused.

Trademark has many exceptions. The First Amendment protects your right to use trademarks in expressive ways, for example, to recreate famous paintings with Barbie dolls:

https://www.copyright.gov/fair-use/summaries/mattel-walkingmountain-9thcir2003.pdf

And then there's "nominative use": it's not a trademark violation to use a trademark to accurately describe a trademarked thing. "We fix iPhones" is not a trademark violation. Neither is 'Works with HP printers.' This goes double for "expressive" uses of trademarks in new works of art:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rogers_v._Grimaldi

What about "dilution"? Trademark protects a small number of superbrands from uses that "impair the distinctiveness or harm the reputation of the famous mark, even when there is no consumer confusion." Jenkins says that the Mickey silhouette and the current Mickey character designs might be entitled to protection from dilution, but Steamboat Willie doesn't make the cut.

Jenkins closes with a celebration of the public domain's ability to inspire new works, like Disney's Three Musketeers, Disney's Christmas Carol, Disney's Beauty and the Beast, Disney's Around the World in 80 Days, Disney's Alice in Wonderland, Disney's Snow White, Disney's Hunchback of Notre Dame, Disney's Sleeping Beauty, Disney's Cinderella, Disney's Little Mermaid, Disney's Pinocchio, Disney's Huck Finn, Disney's Robin Hood, and Disney's Aladdin. These are some of the best-loved films of the past century, and made Disney a leading example of what talented, creative people can do with the public domain.

As of January 1, Disney will start to be an example of what talented, creative people give back to the public domain, joining Dickens, Dumas, Carroll, Verne, de Villeneuve, the Brothers Grimm, Twain, Hugo, Perrault and Collodi.

Public domain day is 17 days away. Creators of all kinds: start your engines!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/12/15/mouse-liberation-front/#free-mickey

Image:

Doo Lee (modified)

https://web.law.duke.edu/sites/default/files/images/centers/cspd/pdd2024/mickey/Steamboat-WIllie-Enters-Public-Domain.jpeg

CC BY 4.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#copyfight#scotus#mickey mouse#public domain#ip#contract#trademark#tm#jennifer jenkins#copyright#disney#nominative use

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

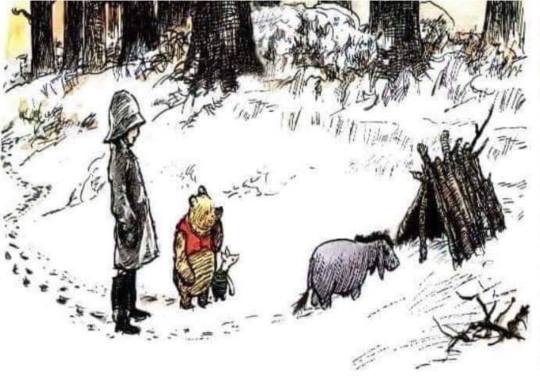

It occurred to Pooh and Piglet that they hadn't heard from Eeyore for several days, so they put on their hats and coats and trotted across the Hundred Acre Wood to Eeyore's house. Inside the house was Eeyore.

"Hello Eeyore," said Pooh.

"Hello Pooh. Hello Piglet" said Eeyore, in a Glum sounding voice.

"We just thought we'd check on you," said Piglet, "because we hadn't heard from you, and so we wanted to know if you were okay."

Eeyore was silent for a moment. "Am I okay?" he asked, eventually. "Well, I don't know, to be honest. Are any of us really okay? That's what I ask myself. All I can tell you, Pooh and Piglet, is that right now I feel really rather Sad, and Alone, and Not Much Fun To Be Around At All.

Which is why I haven't bothered you. Because you wouldn't want to waste your time hanging out with someone who is Sad, and Alone, and Not Much Fun To Be Around At All, would you now."

Pooh looked at Piglet, and Piglet looked at Pooh, and they both sat down, one on either side of Eeyore in his stick house.

Eeyore looked at them in surprise. "What are you doing?"

"We're sitting here with you," said Pooh, "because we are your friends. And true friends don't care if someone is feeling Sad, or Alone, or Not Much Fun To Be Around At All. True friends are there for you anyway. And so here we are."

"Oh," said Eeyore. "Oh." And the three of them sat there in silence, and while Pooh and Piglet said nothing at all; somehow, almost imperceptibly, Eeyore started to feel a very tiny little bit better.

Because Pooh and Piglet were There.

No more; no less.

Author - AA Milne

Illustration - EH Shepard

My favorite Pooh story.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cabin Pressure Advent Day 16: Paris

PAAAAAARRRRRRIIIISSSS!

There are not words for how much I love this episode, there really aren't. I actually listened to it early this morning because I was so excited, and then had to deal with a difficult personal situation and was like "oh dang I wish I hadn't listened to it yet so I could cheer up from it now!" But I had, so I listened to Hot Desk (from Double Acts) instead. Also very effective.

Anyway- I love everything about this episode, because I LOVE Golden Age mysteries! I'm not super well read on all the different authors, but I've had a lot of fun over the years reading Conan Doyle (and Poe and Wilkie Collins, if we're going that far back), Chesterton, Christie, and more recently Sayers, and even more recently have read a smattering as well of John Dickson Carr, Margery Allingham, Anthony Berkeley, and a bunch of others. To digress a little, I highly highly recommend Martin Edwards's excellent book The Golden Age of Murder and his wonderful short-story anthology compilations and reprints- it really got me on a kick of trying to read a bit more broadly in the genre after discovering how much I loved reading a few specific authors growing up. It's been really rewarding and I highly recommend it!

Now, the thing with Paris is that the popular backstory is "John Finnemore had Benedict Cumberbatch on the show, he became famous as Sherlock on Sherlock, Finnemore thought it would be funny to do a mystery themed one as a result, and so we have Marin Crieff as "Miss Marple." Which is apparently not UNtrue per se, but JF himself has said that he always planned to do a mystery episode. Which makes sense, as in the first link just now JF makes clear that Golden Age mysteries are his "trashy fiction of choice," about which I can only say amen!

Which is what makes the episode so great- because it's super clear what kind of love for the genre he put into the episode as a result. There's the Christie- obviously the Miss Marple references but also the "gathering everyone together in the parlor" thing (which she doesn't do ALL the time... but she does PRETTY often lol). There's obviously the Conan Doyle reference, which is "snappily put," as Douglas says. There's a fun reference to Raffles- who may not be a detective himself but is definitely a cousin to the whodunnit genre (or shall we say brother-in-law, as he was Conan Doyle's...), and there's "Crieff of the Yard," which is a phrase that I'm confident has a basis in detective writing but that I'm not able to pinpoint, which is annoying. Arthur's example of the monkey at the circus also evokes a few stories of MASSIVELY varying quality involving unlikely murderous animals, which is always fun. (And parenthetically, while there are no Sayers references that I can find, I will say that I continue to be confident that the dog-collar plotline in Here's What We Do from Double Acts is a reference to the dog-collar plotline in Gaudy Night. He has never confirmed it but like, how could it not be? Or at least so I tell myself.)

But all of that is window dressing- the episode itself is a beautifully written impossible crime mystery, and I love that about it. JF has mentioned that he likes John Dickson Carr, who was big for locked room mysteries/impossible crimes- though loads of writers wrote them (including, incidentally, AA Milne, who you likely know better from Winnie the Pooh, who wrote a fun early example of the genre that you can read here for free because of that magical phenomenon, copyright expiration). And this episode is just such a good example of one that it makes me wish that JF would get into the whodunnit-writing game more broadly (beyond his Cain's Jawbone sequel). If Richard Osman can do it...!

In one of the above-linked blogposts, JF mentions that it's "pleasing how naturally my main cast fitted into familiar roles from the detective fiction genre - the meticulous detective, his devoted assistant, his no nonsense boss… and his nemesis, the Napoleon of crime." Which is awesome, but I think there's even more there. I particularly love that it's an impossible crime mystery in a closed circle. While there's a genre of whodunnit where you have the corpse or whatever and have to cast a wide net to find witnesses and clues, writers there often either have to make the potential dead ends in the detective work REALLY interesting or rely a lot on coincidence. Closed circle crimes (like ones at a country house or within a workplace or somewhere with guards at all the doors or something like that) can help mystery writers focus in on the story without having to worry too much about the logistics of "why these people?" and it's why you get so many mysteries set on trains or ships or islands or whatever. And an airplane is one of the best closed circles there is, because unless you're DB Cooper you're not getting out. Agatha Christie did an early one in Death in the Clouds which is a lot of fun, and this episode is a great example.

The fun thing about closed circle whodunnits and impossible crime mysteries is that the whole point of them is that usually, the author is just straight up lying to you. There's a vent for a snake to go through, or a secret doorway to the outside, or the time when the door was locked or the circle was closed isn't actually when the crime took place, but a fake gunshot makes you think it was. And that's why I love this so much- because the author/liar of the mystery is Douglas. He's the genre savvy one. He's the one who's lying, he's the one who's turning it all into a whodunnit, and he's waiting to see if he can get away with it. He's the Napoleon of Crime- and a Columbo villain setting up the false trail that he hopes Columbo will fall for.

Because... and JF notes this in both blog posts... there's no mystery here! Obviously Douglas did it. The point here is that this episode is like if Columbo was as dumb as he seemed and the criminal managed to lead him down the garden path and got away with it. It's "what if Poirot were a moron but still had to solve the murder of Roger Ackroyd." Douglas is the one who creates an impossible crime scheme, anticipates that he'll still be suspected because, well, he's him, and manages to come up with alternative scenarios- including ones that open the seemingly closed circle of the crime- that are convincing enough to throw Martin off the scent. Without him, it would just be "so how did Douglas do it this time?"

Now, the impossible crime is still important, because while we all kind of know that Douglas did it, we still don't know how he did it. And from that perspective alone, JF's impossible crime puzzle is genius. The clues that he drops are really interesting (I'm not 100% sure I see the nail polish bottle as being fair play, but plenty of whodunnits aren't so I don't really care) and it's something that, even as we see Douglas writing a whole separate decoy mystery (reminiscent of his decoy apple juice?) on top of his own scheme, keeps us intrigued throughout even once it becomes pretty clear that Douglas has been snowing all of them. So all of that is fun- but it's far more fun with all the other tropes and schemes and false trails laid on top of it, giving it so many more dimensions.

And then, at the end, nobody solves it- the detective's reveal, after all the carefully left false trails, comes from the thief himself.

It's just... so beautiful. Ahhhh.

I feel like (and one of the blog posts mentions this) that there's a question of whether Douglas actually pulled it off, particularly in the context of whether Martin would really need to pay Carolyn at the end. My opinion is: practically, yes, Douglas stole the whiskey. If Birling hadn't offered them the cufflinks, he'd never have revealed his trick and he'd have had ample opportunity the rest of the trip to empty his decoy apple juice in the sink, replace it with whiskey, and fill up the bottle with cheap whiskey from the plane's bar or the Paris airport duty free. (Or whatever his plan was- but that seems plausible.) Carolyn would have never known once they returned. And the episode leaves open whether practically speaking Martin actually does have to pay Carolyn, but thematically... yes, of course he does, the whole question here is "is Douglas the organ grinder" and the answer is that he obviously is. The monkey's gotta pay up!

I love, incidentally, so many more things about this episode- the humor, Mr Birling, the ways in which everything is so true to character, basically everything about Arthur... but I've already gone on long enough.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

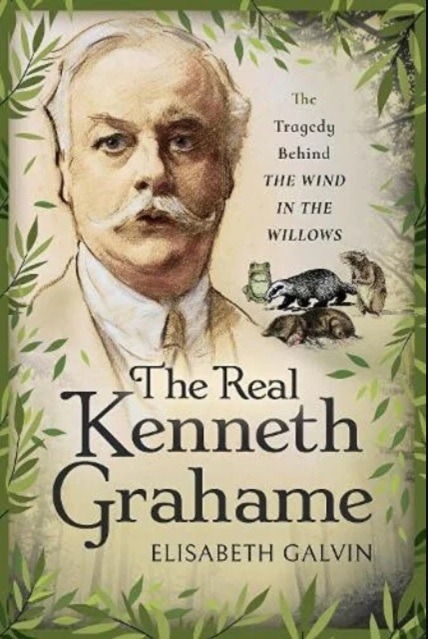

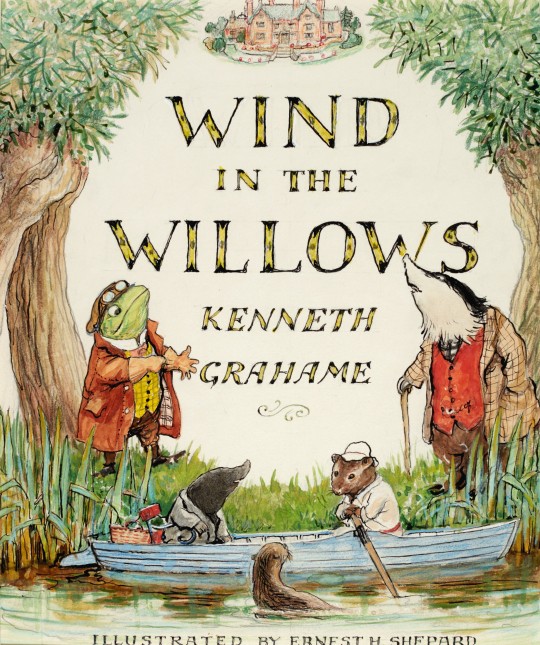

On March 8th 1859 the Scottish author Kenneth Grahame was born in Edinburgh.

When he was a little more than a year old, his father, an advocate, received an appointment as sheriff-substitute in Argyllshire at Inveraray on Loch Fyne. Kenneth loved the sea and was happy there, but when he was five, his mother died of puerperal fever and his father, who had a drinking problem, gave over care of Kenneth, his brother Willie, his sister Helen and the new baby Roland to stay with their maternal grandmother, ‘Granny Ingles’, who had a large house called the Mount, in Cookham Dean in the village of Cookham in Berkshire.

Mr Grahame was a pupil at St Edward’s School from the age of nine, by the time he left he was head boy, captain of the rugby XV and the winner of several academic prizes.

He began working as a banker and rose to become company secretary at the Bank of England, working on ideas for a book from the bedtime stories he told his son Alistair .It was while working at the bank he had an encounter that could have cost him his life.

At around 11 o'clock on the morning of 24 November, 1903, a man called George Robinson, who in newspaper accounts of what followed would be referred to simply as 'a Socialist Lunatic’, arrived at the Bank of England. There, Robinson asked to speak to the governor, Sir Augustus Prevost. Since Prevost had retired several years earlier, he was asked if he would like to see the bank secretary, Kenneth Grahame, instead.

When Grahame appeared, Robinson walked towards him, holding out a rolled up manuscript. It was tied at one end with a white ribbon and at the other, with a black one. He asked Grahame to choose which end to take. After some understandable hesitation, Grahame chose the end with the black ribbon, whereupon Robinson pulled out a gun and shot at him. He fired three shots; all of them missed.

Several bank employees managed to wrestle Robinson to the ground, aided by the Fire Brigade who turned a hose on him. Strapped into a straitjacket, he was bundled away and subsequently committed to Broadmoor.

His first book, Pagan Papers, was published in 1893.a collection of stories and essays on the general theme of escape, the book did well. A year afterwards, Grahame had retreated to his country home and began to write The Wind in the Willows -111 years later the book is is still in print and as popular as ever. The Wind in the Willows tells the story of four animals living on a stretch of the Thames at Pangbourne, near Reading.

He also wrote The Reluctant Dragon. Both books were later adapted for stage and film, of which A. A. Milne’s Toad of Toad Hall was the first. The Disney films The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad and The Reluctant Dragon are other adaptations.

Grahame died in Pangbourne, Berkshire, in 1932. He is buried in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford.

Some people believe AA Milne wrote wind in the Willows, but he wrote the play Toad of Toad Hall, which is based on part of The Wind in the Willows.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Nobel prize-winning novelist and essayist Kenzaburō Ōe, who has died aged 88, made his name as a cult author for Japan’s rebellious postwar youth. His early fiction – titles such as Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids (1958), Seventeen (1961) and J (1963), peopled with juvenile delinquents, political fanatics and subway perverts – gave voice to an alienated generation who witnessed the collapse of their parents’ values with the defeat of the second world war. His wartime childhood fed a lifelong pacifism, and his scourging of resurgent militarism and consumerism. Yet his decisive rebirth as a writer came through fatherhood.

When Ōe was 28, his first child, Hikari, was born with a herniated brain protruding from his skull. Surgery risked brain damage, and doctors urged Ōe and his wife, Yukari, to let the infant die – a “disgraceful” time, he later wrote, that “no powerful detergent” could expunge. Then also working as a journalist, Ōe fled to report on a peace rally in Hiroshima. His encounters with hibakusha (atomic-bomb survivors) and doctors there convinced him his son must live – a moment he saw as a “conversion”. As he told me in Tokyo just after his 70th birthday “I was trained as a writer and as a human being by the birth of my son.”

The imaginative link between his stricken son and the survivors of nuclear fallout and military aggression – the personal and the political – is Ōe’s most profound literary insight. Intolerance of the weak to the point of euthanasia has historically presaged militarism – in imperial Japan as in Nazi Germany. Ōe’s lifelong commitment to Hikari (nicknamed “Pooh” after AA Milne’s bear) inspired a unique cycle of fiction whose protagonists are fathers of brain-damaged sons – often named Eeyore – and pervades his literary vision.

His conversion was reflected in a volume of essays, Hiroshima Notes (1965), and the novel A Personal Matter (1964), whose antihero Bird takes refuge in alcohol and adultery until he resolves to rescue his newborn “two-headed monster”. Its translator John Nathan thought it the “most passionate and original and funniest and saddest Japanese book I had ever read”. Ōe’s masterpiece, The Silent Cry, in which the narrator and his violently rebellious brother (both facets of the author) clash over family history, was published in 1967. These novels, published in English translation in, respectively, 1969 and 1988, brought Ōe the international recognition that culminated in the 1989 Prix Europalia and 1994 Nobel prize for literature.

His Nobel lecture, Japan, the Ambiguous and Myself, was a rejoinder to the 1968 Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata, who had lectured on Japan, the Beautiful and Myself. Ōe spoke of a Japan, after its “cataclysmic” 19th-century modernisation drive, vacillating between Europe and Asia, western modernity and tradition, aggression and human decency – a polarisation he felt as a “deep scar” from which he wrote to free himself.

The novelist Kazuo Ishiguro told me Ōe was “fascinated by what’s not been said” about Japan’s wartime past. Believing the writer’s role to be akin to a canary in a coalmine, he assailed that reticence head on. “Did the Japanese really learn anything from the defeat of 1945?” he wrote in a 50th anniversary foreword to Hiroshima Notes. Although nuclear atrocity, and the drive to rebuild Japan as a cold-war ally, encouraged a sense of victimhood, one of the neglected lessons, for Ōe, was that his parents’ generation were not just victims but aggressors in Asia.

Ōe was born in Ose, a remote mountain village of Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands. His father was killed in 1944, and his mother saw a flash in the sky when far-off Hiroshima was bombed. Ōe was 10 when Emperor Hirohito surrendered in 1945 and robbed Ōe’s generation of their innocence. All that had seemed true became a lie. Fear and relief as US jeeps rolled in with the allied occupation of 1945-52 created a lasting ambivalence. Ōe, who later campaigned against US military bases in Okinawa, said: “I admired and respected English-speaking culture, but resented the occupation.”

His family were driven out of their banknote-paper business by currency reform. At Tokyo University in 1954-59, where he studied French, his country accent made Ōe feel an outsider, but a 1957 novella (translated as Prize Stock in the collection Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness), in which a boy’s friendship with a black American PoW is destroyed by war, won him the Akutagawa prize for best debut, at 23. Inspired by Rabelais’ grotesque realism, Sartre’s existentialism and an American tradition from Huckleberry Finn to Catcher in the Rye, he created antiheroes who courted disgrace in their disgust at civilisation. His assault on traditional values extended to the Japanese language. Nathan noted a “fine line between artful rebellion and mere unruliness”.

At his home in a quiet Tokyo suburb, visitors could not fail to be struck by his humility and self-deprecating humour. As he amiably recounted meeting Chairman Mao in Beijing in 1960, with his “Giant Panda cigarettes”, Ōe mimed smoking them with relish. Just as striking was his devotion to family. He married Yukari, the daughter of the prewar film director Mansaku Itami, in 1960, and Hikari, the first of their three children, was born in 1963. Although Hikari’s condition circumscribed his father’s life, it also enlarged it. It was through their relationship that Ōe grasped the “role of the weak in helping avoid the horrors of war” (the subject of a fictitious musical) and the “wondrous healing power of art”.

Hikari’s rare talent for identifying birdsong was spotted when he was six. Despite autism, visual impairment, epilepsy and learning disabilities, he had perfect pitch and became a renowned composer – the joint subject of Lindsley Cameron’s book on father and son, The Music of Light (1998). Yet in novels by Ōe such as Rouse Up, O Young Men of the New Age! (1983) – the title from William Blake – it is not Eeyore’s talent that is redemptive but the innocence he incarnates. Confronting parental ambivalence about the maturing sexuality of their children, that novel reveals fear of the vulnerable to be a projection of the darkness within ourselves.

Ōe’s post-Nobel novels could be large and, for some, unwieldy. The doomsday cult in Somersault (1999) resembled Aum Shinrikyo, perpetrators of the 1995 Tokyo subway gas attack, but the trauma of an apocalyptic leader renouncing his twisted faith harked back to the war. The Changeling (2000) fictionalised Ōe’s friendship with Juzo Itami (his wife’s brother). The director of the cult comedy Tampopo (1985), and a 1995 film adaptation of Ōe’s novel A Quiet Life (1990), Juzo died after falling from the roof of his office building in 1997, five years after his face was slashed by yakuza gangsters whom he had ridiculed on screen. In Death By Water (2009), Ōe’s alter-ego Kogito (the name a wry nod to Descartes) strives to write a novel about his father’s death.

Yet it is for the “idiot son” cycle that Ōe may most vividly be remembered. “I believe in tolerance,” Ōe said, and how the innocent “can play a role in fighting against violence”. After 1945, he felt strongly, Japan should have “stood up with the weak … the weak are a value in themselves.”

He is survived by Yukari, and their children, Hikari, another son, Sakurao, and a daughter, Natsumiko.

🔔 Kenzaburō Ōe, writer, born 31 January 1935; died 3 March 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is the theme of your display children's writers? If so, consider AA Milne, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, or Lewis Carol. Hope this helps <3

lol the display is in the picture book collection and the theme is Whatever I Want It To Be!! So I sometimes spotlight an author if they’re prolific enough to fill a display — I’ve done Tomie dePaola and Patricia Polacco before, and Willems and Yolen could each do it on their own but Imma do them together as a single display for February because again I think it’s neat that these two juggernauts of modern children’s lit share a birthday — but I also do themes based on holidays, seasonal changes, heritage months/days, local interest, my personal interests, silly stuff, etc.

[For instance my mum has recommended that the January display simply be “Cats,” which is a compelling suggestion. Probably better than my one idiotic thought, which is that it would be hilarious to do an “owo whats this” display with titles like, Brown Bear Brown Bear / Are You A Cheeseburger / Are You My Mother / This Is Not My Hat — but for professionalism reasons I am probably not going to do an Internet joke about balls in the picture book section.]

Milne, Naylor, and Carroll are unfortunately not eligible for this display as they write for an older audience (Milne is borderline but my system catalogs House at Pooh Corner in chapter books) and I do have the calendar for middle grade fiction displays basically decided through the end of May, but you have excellent taste in kids’ lit, anon <3 I actually had a couple of the Shiloh books up earlier this year as part of a Dogs-in-Fiction display!

#not that having a book up once in a year will at all prevent me from doing it again#this year I had Dragon Pearl up for the Science Fiction / Asimov Day‚ Trans Day of Visibility‚ and regular Pride displays#and by the end of the year that copy had circ’d enough that it was GROSS and we had to buy a new one >:3#asks#anonymous

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

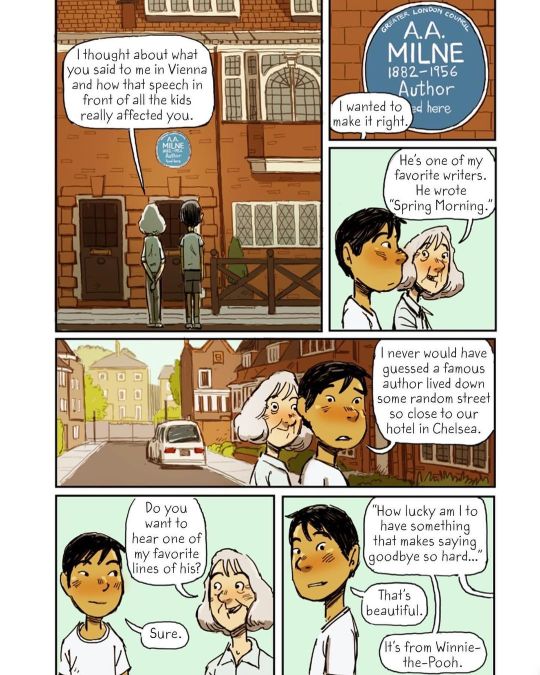

Happy Birthday to author AA Milne, the author of Winnie the Pooh and other works such as “Spring Morning”, a poem which I had a love/hate relationship with for 35 years due to a middle school mishap. Not my greatest moment, but I wouldn’t change a thing ❤️#AFirstTimeforEverything https://www.instagram.com/p/CnkKlzPvsfE/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

<<"Now," said Kanga, "there's your medicine, and then bed."

"W-w-what medicine?" said Piglet.

"To make you grow big and strong, dear. You don't want to grow up small and weak like Piglet, do you? Well, then!"

At that moment there was a knock at the door.

"Come in," said Kanga, and in came Christopher Robin.

"Christopher Robin, Christopher Robin!" cried Piglet. "Tell Kanga who I am! She keeps saying I'm Roo. I'm not Roo, am I?"

Christopher Robin looked at him very carefully, and shook his head.

"You can't be Roo," he said, "because I've just seen Roo playing in Rabbit's house."

"Well!" said Kanga. "Fancy that! Fancy my making a mistake like that."

"There you are!" said Piglet. "I told you so. I'm Piglet."

Christopher Robin shook his head again.

"Oh, you're not Piglet," he said. "I know Piglet well, and he's quite a different colour."

Piglet began to say that this was because he had just had a bath, and then he thought that perhaps he wouldn't say that, and as he opened his mouth to say something else, Kanga slipped the medicine spoon in, and then patted him on the back and told him that it was really quite a nice taste when you got used to it.>> (Link: https://americanliterature.com/author/aa-milne/book/winnie-the-pooh/chapter-vii-in-which-kanga-and-baby-roo-come-to-the-forest-and-piglet-has-a-bath)

Ok, you guys, this scene is sublime and absolutely comical, but, honestly I take 2 to 3 fish oil gel pills a day and............ I've never been darting back and forth like that! So EITHER Disney overdid it to make it comical OR Kanga overdid the dose.🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣

0 notes

Text

Here’s my favorite authors!

JRR Tolkien

Neil Gaiman

Diana Wynne Jones

Ray Bradbury

Ernest Hemingway

Lemony Snicket

Lois Lowry

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Stroud

Charles Dickens

Plato

Thomas Paine

Jerry Spinelli

Christopher Morley

AA Milne

Garth Nix

John Milton

Alexandre Dumas

Victor Hugo

Terry Pratchett

JK Rowling

#writing#books#good writers read#book recommendations#good reads#book recs pls#favorite authors#classic literature#literature#literary analysis

0 notes

Text

Winnie the Pooh stories cure any illness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID Disneyfied version of Winnie the Pooh floating in a cloud filled sky with a blue balloon in his left paw. He’s smiling at a bee which is hovering near his nose. The words Happy Winnie the Pooh Day in red are to the left of Pooh.]

Happy Winnie the Pooh Day!

Today marks the birthday of AA Milne, creator of the immortal Winnie the Pooh and friends.

An illustration by EH Shepard, original illustrator of Pooh and friends, of Winnie the Pooh and Piglet sitting atop a gate while it snows. Pooh has a stick in his right paw and is wearing a red waistcoat as he puffs breath into the frigid air. Piglet is wearing a green top and has both arms in the air as he copies Pooh’s actions.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023's public domain is a banger

40 years ago, giant entertainment companies embarked on a slow-moving act of arson. The fuel for this arson was copyright term extension (making copyrights last longer), including retrospective copyright term extensions that took works out of the public domain and put them back into copyright for decades. Vast swathes of culture became off-limits, pseudo-property with absentee landlords, with much of it crumbling into dust.

After 55-75 years, only 2% of works have any commercial value. After 75 years, it declines further. No wonder that so much of our cultural heritage is now orphan works, with no known proprietor. Extending copyright on all works – not just those whose proprietors sought out extensions – incinerated whole libraries full of works, permanently.

But on January 1, 2019, the bonfire was extinguished. That was the day that items created in 1923 entered the US public domain: DeMille's Ten Commandments, Chaplain's Pilgrim, Burroughs' Tarzan and the Golden Lion, Woolf's Jacob's Room, Coward's London Calling and 1,000+ more works:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2019/

Many of those newly liberated works were forgotten, partly due to their great age, but also because no one knew who they belonged to (Congress abolished the requirement to register copyrights in 1976), so no one could revive or reissue them while they were still in the popular imagination, depriving them of new leases on life.

2019 was the starting gun on a new public domain, giving the public new treasures to share and enjoy, and giving the long-dead creators of the Roaring Twenties a new chance at posterity. Each new year since has seen a richer, more full public domain. 2021 was a great year, featuring some DuBois, Dos Pasos, Huxley, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Bessie Smith and Sydney Bechet:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/12/16/fraught-superpowers/#public-domain-day

In just 12 days, the public domain will welcome another year's worth of works back into our shared commons. As ever, Jennifer Jenkins of Duke's Center for the Public Domain have painstaking researched highlights from the coming year's entrants:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2023/

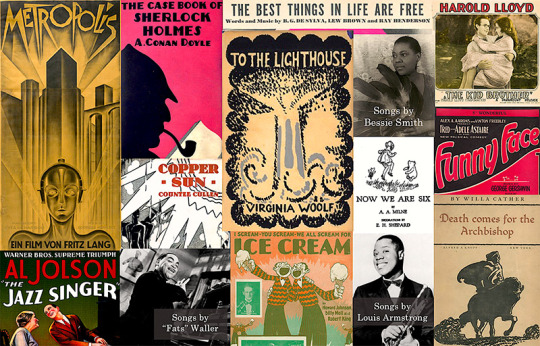

On the literary front, we have Virginia Woolf's To The Lighthouse, AA Milne's Now We Are Six, Hemingway's Men Without Women, Faulkner's Mosquitoes, Christie's The Big Four, Wharton's Twilight Sleep, Hesse's Steppenwolf (in German), Kafka's Amerika (in German), and Proust's Le Temps retrouvé (in French).

We also get all of Sherlock Holmes, finally wrestling control back from the copyright trolls who control the Arthur Conan Doyle estate. This is a firm of rent-seeking bullies who have abused the court process to extract menaces money from living creators, including rent on works that were unambiguously in the public domain.

The estate's sleaziest trick is claiming that while many Sherlock Holmes stories were in the public domain, certain elements of Holmes's personality were developed in later stories that were still in copyright, and therefore any Sherlock story that contained those elements was a copyright violation. Infamously, the Doyle Estate went after the creators of the Enola Holmes series, claiming a copyright over Sherlock stories in which Holmes was "capable of friendship," "expressed emotion," or "respected women." This is a nonsensical theory, based on the idea that these character traits are copyrightable. They are not:

https://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/publicdomainday/2023/#fn6text

The Doyle Estate's shakedown racket took a serious body-blow in 2013, when Les Klinger – a lawyer, author and prominent Sherlockian – prevailed in court, with the judge ruling that new works based on public domain Sherlock stories were not infringing, even if some Sherlock stories remained in copyright. The estate appealed and lost again, and Klinger was awarded costs. They tried to take the case to the Supreme Court and got laughed out of the building.

But as the Enola Holmes example shows, you can't keep a copyright troll down: the Doyle estate kept making up imaginary copyright laws in a desperate, grasping bid to wring more money out of living, working creators. That's gonna be a lot harder after Jan 1, when The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes enters the public domain, meaning that every Sherlock story will be out of copyright.

One fun note about Klinger's landmark win over the Doyle estate: he took an amazing victory lap, commissioning an anthology of new unauthorized Holmes stories in 2016 called "Echoes of Sherlock Holmes":

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Echoes-of-Sherlock-Holmes/Laurie-R-King/Sherlock-Holmes/9781681775463

I wrote a short story for it, "Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Extraordinary Rendition," which was based on previously unpublished Snowden leaks.

https://esl-bits.net/ESL.English.Listening.Short.Stories/Rendition/01/default.html

I got access to the full Snowden trove thanks to Laura Poitras, who jointly commissioned the story from me for inclusion in the companion book for "Astro noise : a survival guide for living under total surveillance," her show at the Whitney:

https://www.si.edu/object/siris_sil_1060502

I also reported out the leaks the story was based on in a companion piece:

https://memex.craphound.com/2016/02/02/exclusive-snowden-intelligence-docs-reveal-uk-spooks-malware-checklist/

Jan 1, 2023 will also be a fine day for film in the public domain, with Metropolis, The Jazz Singer, and Laurel and Hardy's Battle of the Century entering the commons. Also notable: Wings, winner of the first-ever best picture Academy Award; The Lodger, Hitchcock's first thriller; and FW "Nosferatu" Mirnau's Sunrise.

However most of the movies that enter the public domain next week will never be seen again. They are "lost pictures," and every known copy of them expired before their copyrights did. 1927 saw the first synchronized dialog film (The Jazz Singer). As talkies took over the big screen, studios all but gave up on preserving silent films, which were printed on delicate stock that needed careful tending. Today, 75% of all silent films are lost to history.

But some films from this era do survive, and they are now in the public domain. This is true irrespective of whether they were restored at a later date. Restoration does not create a new copyright. "The Supreme Court has made clear that 'the sine qua non of copyright is originality.'"

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/499/340

There's some great music entering the public domain next year! "The Best Things In Life Are Free"; "I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice-Cream"; "Puttin' On the Ritz"; "'S Wonderful"; "Ol' Man River"; "My Blue Heaven" and "Mississippi Mud."

It's a banger of a year for jazz and blues, too. We get Bessie Smith's "Back Water Blues," "Preaching the Blues," and "Foolish Man Blues." We get Louis Armstrong's "Potato Head Blues" and "Gully Low Blues." We get Jelly Roll Morton's "Billy Goat Stomp," "Hyena Stomp," and "Jungle Blues." And we get Duke Ellington's "Black and Tan Fantasy" and "East St. Louis Toodle-O."

Note that these are just the compositions. No new sound recordings come into the public domain in 2023, but on January 1, 2024, all of 1923's recordings will enter the public domain, with more recordings coming in every year thereafter.

We're only a few years into the newly reopened public domain, but it's already bearing fruit. The Great Gatsby entered the public domain in 2021, triggering a rush of beautiful new editions and fresh scholarship:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/14/books/the-great-gatsby-public-domain.html

These new editions were varied and wonderful. Beehive Books produced a stunning edition, illustrated by the Balbusso Twins, with a new introduction by Wellesley's Prof William Cain:

https://beehivebooks.com/shop/gatsby

And Planet Money released a fabulous, free audiobook edition:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/18/peak-indifference/#gatsby

Last year saw the liberation of Winnie the Pooh, unleashing a wild and wonderful array of remixes, including a horror film ("Blood and Honey") and also innumerable, lovely illustrations and poems, created by living, working creators for contemporary audiences.

As Jenkins notes, many of the works that enter the public domain next week display and promote "racial slurs and demeaning stereotypes." The fact that these works are now in the public domain means that creators can "grapple with and reimagine them, including in a corrective way." They can do this without having to go to the Supreme Court, unlike the Alice Randall, whose "Wind Done Gone" retold "Gone With the Wind" from the enslaved characters' perspective:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wind_Done_Gone

After all this, you'd think that countries around the world would have learned their lesson on copyright term extension, but you'd be wrong. In Canada, Justin Trudeau caved to Donald Trump and retroactively expanded copyright terms by 20 years, as part of USMCA, the successor to NAFTA. Trudeau ignored teachers, professors, librarians and the Minister of Justice, who said that copyright extension should require "a modest registration requirement" – so 20 years of copyright will be tacked onto all works, including those with no owners:

https://www.michaelgeist.ca/2022/04/the-canadian-government-makes-its-choice-implementation-of-copyright-term-extension-without-mitigating-against-the-harms/

Other countries followed Canada's disastrous lead: New Zealand "agreed to extend its copyright term as a concession in trade agreements, even though this would cost around $55m [NZ dollars] annually without any compelling evidence that it would provide a public benefit":

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/nz-agrees-to-mickey-mouse-copyright-law

Wrapping up her annual post, Jenkins writes of a "melancholy" that "comes from the unnecessary losses that our current system causes—the vast majority of works that no longer retain commercial value and are not otherwise available, yet we lock them all up to provide exclusivity to a tiny minority.

"Those works which, remember, constitute part of our collective culture, are simply off limits for use without fear of legal liability. Since most of them are 'orphan works' (where the copyright owner cannot be found) we could not get permission from a rights holder even if we wanted to. And many of those works do not survive that long cultural winter."

[Image ID: A montage of works that enter the public domain on Jan 1, 2023.]

#pluralistic#copyright#usmca#james boyle#jennifer jenkins#canpoli#canada#silent films#enola holmes#les klinger#copyright trolls#rogers and hammerstein#irving berlin#laurel and hardy#marcel proust#ernest hemingway#william faulkner#copyfight#public domain#remix#preservation#al jolson#winnie the pooh#franz kafka#virginia woolf#metropolis#sherlock holmes

632 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Heide Goody and Iain Grant's Pigeonwings

Book Review: Heide Goody and Iain Grant’s Pigeonwings

Second in the Clovenhoof urban fantasy series revolving around the retired Lucifer, who’s now living in an apartment in Birmingham. The focus is split between the Archangel Michael and Jayne and Ben. It’s been almost two months since Clovenhoof, 1.

My Take

Pigeonwings is composed of strung-together vignettes in which Goody/Grant are poking fun at everyday aspects of human life from food to the…

View On WordPress

#AA Milne and Us Two#abbey#apple tree#author Heide Goody#author Iain Grant#Birmingham#book review#Cain and Abel#church#Clovenhoof series#cub scouts#England#escapes#family#hallucinogenic mushrooms#Jungle Book#King Arthur#Merlin#neighbors#Sutton Coldfield#sword#third-person global subjective point-of-view#urban fantasy#wedding

1 note

·

View note

Photo

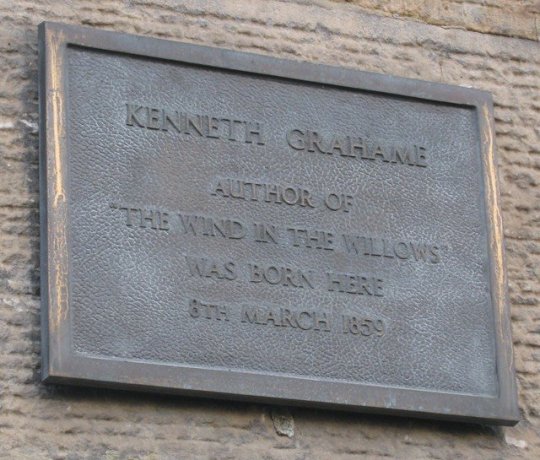

March 8th 1859 the Scottish author Kenneth Grahame was born in Edinburgh.

When he was a little more than a year old, his father, an advocate, received an appointment as sheriff-substitute in Argyllshire at Inveraray on Loch Fyne. Kenneth loved the sea and was happy there, but when he was five, his mother died of puerperal fever and his father, who had a drinking problem, gave over care of Kenneth, his brother Willie, his sister Helen and the new baby Roland to stay with their maternal grandmother, ‘Granny Ingles’, who had a large house called the Mount, in Cookham Dean in the village of Cookham in Berkshire.

Mr Grahame was a pupil at St Edward’s School from the age of nine, by the time he left he was head boy, captain of the rugby XV and the winner of several academic prizes.

He began working as a banker and rose to become company secretary at the Bank of England, working on ideas for a book from the bedtime stories he told his son Alistair.It was while working at the bank he had an encounter that could have cost him his life.

At around 11 o'clock on the morning of 24 November, 1903, a man called George Robinson, who in newspaper accounts of what followed would be referred to simply as 'a Socialist Lunatic’, arrived at the Bank of England. There, Robinson asked to speak to the governor, Sir Augustus Prevost. Since Prevost had retired several years earlier, he was asked if he would like to see the bank secretary, Kenneth Grahame, instead.

When Grahame appeared, Robinson walked towards him, holding out a rolled up manuscript. It was tied at one end with a white ribbon and at the other, with a black one. He asked Grahame to choose which end to take. After some understandable hesitation, Grahame chose the end with the black ribbon, whereupon Robinson pulled out a gun and shot at him. He fired three shots; all of them missed.

Several bank employees managed to wrestle Robinson to the ground, aided by the Fire Brigade who turned a hose on him. Strapped into a straitjacket, he was bundled away and subsequently committed to Broadmoor.

His first book, Pagan Papers, was published in 1893.a collection of stories and essays on the general theme of escape, the book did well. A year afterwards, Grahame had retreated to his country home and began to write The Wind in the Willows -111 years later the book is is still in print and as popular as ever. The Wind in the Willows tells the story of four animals living on a stretch of the Thames at Pangbourne, near Reading.

He also wrote The Reluctant Dragon. Both books were later adapted for stage and film, of which A. A. Milne’s Toad of Toad Hall was the first. The Disney films The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad and The Reluctant Dragon are other adaptations.

Grahame died in Pangbourne, Berkshire, in 1932. He is buried in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford.

Some people believe AA Milne wrote wind in the Willows, but he wrote the play Toad of Toad Hall, which is based on part of The Wind in the Willows.

The last pic is the plaque on Grahame’s birthplace at Castle Street in Edinburgh, just a short walk from last weeks birthday post Alexander Graham Bell, it is now Castle View Guest House, my late friend Lorraine was the housekeeper here.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actress Zawe Ashton: ‘I present as a Tigger, but I’m actually more of a Piglet’

ONE MINUTE WITH...The actor talks about breathing Toni Morrison and feeling like a mythical sea creature in pursuit of a human soul

Where are you now and what can you see?

I’m on the M40 on the way to a shoot. It’s a grim day, but Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place” just came on the radio, which never fails to make me feel alive.

What are you currently reading?

Natasha Brown’s Assembly. I’ve heard it described as a modern-day Mrs Dalloway. It’s so skilful. It explores the damage of colonial legacy from the viewpoint of a black British woman at a garden party.

Who is your favourite author and why do you admire them?

Reading Toni Morrison’s work is like breathing to me. I was handed Beloved by a drama teacher when I was 14 and it changed me. Her magical realism influences my writing today. She’s a beautiful, brutal, fearless poet. Her observations are so searing and as a person, she had so much wisdom to pass on.

Describe the room where you usually write…

I’m often in transit, so trains, planes and automobiles. For real writing peace, I head to the sea. I used to have a womb-like room with a view of a slither of ocean in Margate, which was heaven.

Which fictional character most resembles you?

As someone who often feels like a mythical sea creature in pursuit of a human soul, let’s go with the Little Mermaid. I was obsessed with Hans Christian Andersen when I was little. Or something from AA Milne, who I also loved. I think I present as a Tigger, but I’m actually more of a Piglet.

Who is your hero/heroine from outside literature?

It has to be my mum. As I get older, the idea that she carried me in her womb for nine months, was in 36 hours of labour before I decided to make an appearance, and then cleaned my backside 20 times a day is just so profound.

Zawe Ashton is the host of the Women’s Prize for Fiction podcast available on Acast and Apple. Each week, she interviews guests and celebrates the best books written by women

66 notes

·

View notes