#Belgian goth

Text

"The Great Escape" by Brussels, Belgium-based coldwave and EBM act Ultra Sunn off of their 2023 EP Kill Your Idols

#coldwave#ebm#dark ebm#electronic music#Ultra Sunn#The Great Escape#Kill Your Idols#music#first share#2023#Brussels Belgium#2020s goth#Belgian goth#Bandcamp

11 notes

·

View notes

Audio

“Our Revolutions,” a 2022 single by San José, Costa Rica-based post-punk and darkwave band MOLT, featuring Belgian coldwave solo artist Severine Day

#darkwave#coldwave#postpunk#goth#MOLT#Our Revolutions#singles#music#Costa Rican#Central American#Severine Day#Belgian#international goth#2022#2022 singles#Costa Rican goth#Belgian goth

0 notes

Text

Hellsing characters as animals

Integra:

(Borzoi, snowy owl, secretary bird, lioness)

Alucard:

(Grœnendael, bearded vulture, emperor scorpion, Friesian horse)

Seras:

(Golden retriever, peregrine falcon, fennec fox, golden British shorthair)

Walter:

(Irish wolfhound, great blue heron, black-footed ferret, raven)

Anderson:

(Great Pyrenees, great horned owl, grizzly bear, white tiger)

Pip:

(Jack Russel terrier, ferruginous hawk, stoat, coyote)

#hellsing#sir integra#alucard#seras victoria#walter c dornez#alexander anderson#pip bernadotte#another contender for pip was a Belgian malinois#Anderson tending to his flock while tearing things to shreds#alucard's was surprisingly hard actually#fuck you you goth diva you get cunty horse#anderson's was the easiest#walter too surprisingly

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Demeulemeester 1993

Newest Cool

#newestcool#newest cool#fashion community#fashion figure#fashion designer#- fashion documentary#fashion doc#fashion movie#fashion interview#- belgian fashion#belgian fashion designer#antwerp 6#antwerp six#goth#gothic fashion#goth glam#goth aesthetic#goth style#goth look#ann demeulemeester#stefano gallici#ann demeulemeester shoes#ann demeulemeester boots#demeulemeester#ann demeulemeester official#belgian fashion#90s runway#90s look#90s model#90s editorial

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bruges-la-morte, c. 1900. Fin de siècle Belgian School. Authorship undetermined.

#dark aesthetic#dark#dark art#darkness#gloomy#goth aesthetic#darkest academia#symbolism#bruges#belgian art#aestheticism

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I have fallen deep in love with the sky”

#belgian malinois#belgian#dog#doggo#acid bath#when the kite string pops#yo#me#desert#nature#goth#mountains#sludge#sludge metal#metal#metalhead#leather#wet leather#goth bf#long hair#curly hair#wavy hair#indegenous#Mojave#mojave desert#mojave wasteland#5’11 tactical#John Wayne Gacy#Mr pogo#true crime

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johan finds that Peewit had gone emo and tells him to come back home, knowing the kingdom is worried about him. Digitized with Ibis Paint X.

Johan and Peewit (C) Peyo/IMPS/Lafig Belgium S.A.

#fan art#johan and peewit#peyo#sir johan#peewit#emo#digital#ibis paint x#art#goth#franco belgian comics#bd#bande dessinée#johan et pirlouit

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

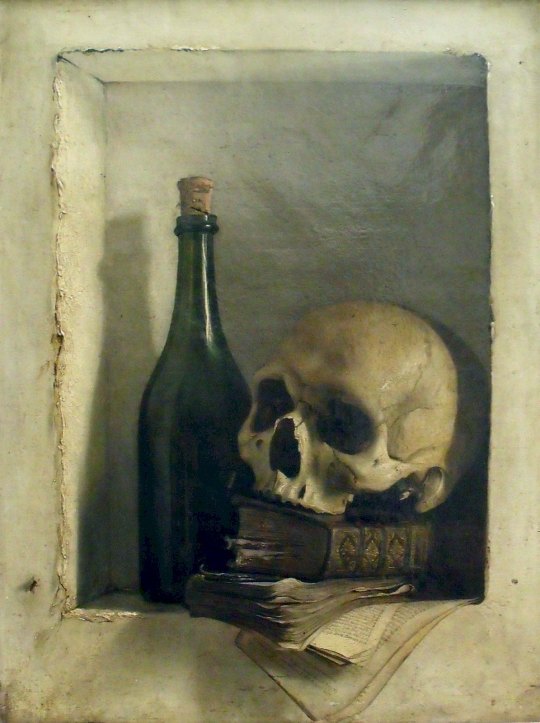

Une Tête de Mort

Antoine Wiertz (1806-1865)

#p#allegory of death#skull#memento mori#belgian art#romanticism#allegorical painting#goth aesthetic#vanitas#the francophone and anglophone internets disagree on the title of this piece but agree that it rules

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑆ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑙𝑖𝑘𝑒 𝑎 𝑐𝑎𝑡 𝑖𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑘

𝐴𝑛𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑛 𝑠ℎ𝑒 𝑖𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑘𝑛𝑒𝑠𝑠

𝑆ℎ𝑒 𝑟𝑢𝑙𝑒𝑠 ℎ𝑒𝑟 𝑙𝑖𝑓𝑒 𝑙𝑖𝑘𝑒 𝑎 𝑓𝑖𝑛𝑒 𝑠𝑘𝑦𝑙𝑎𝑟𝑘

𝐴𝑛𝑑 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑠𝑘𝑦 𝑖𝑠 𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑟𝑙𝑒𝑠𝑠

#art#vmt#artist#small business#big cartel#vt#goth#pastel goth#wax melts#home fragrances#Rhiannon#fleetwood mac#fkeetwood Mac Rhiannon#witch#Belgian witch#coven#triple moon#goth melts#Stevie nicks#vanessa moylan theodore art#artist vanessa theodore#vanessa theodore art#artist vanessa moylan theodore#vanessa moylan theodore#magpie designs by vanessa moylan theodore#vanessa theodore#organizing chaos at prismatic skies#prismatic skies aromatherapy collection#prismatic skies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working dog occupation: boyfrien

#furry oc#furry anthro#queer furry#furry sfw#digital art#tiger oc#malinois oc#belgian malinois#tiger girl#Judas#my ocs#small artist#cute furry#goth furry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Is there an exit? / Show me the way"

Absolute Body Control (1981).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Dead World," a 2022 single by Belgian gothic rock band Ground Nero

#goth#gothrock#goth music#gothcore#Ground Nero#Dead World#singles#music#2022#Belgium#Belgian goth#Bandcamp

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Demeulemeester s/s 1996 rtw

Creative Director Ann Demeulemeester

Model Esther de Jong

Newest Cool

#Esther de jong#90s runway#90s look#90s model#90s editorial#supermodel era#supermodel status#original supermodel#ready to wear collection#runway details#runway style#runway looks#runway collection#ann demeulemeester#stefano gallici#ann demeulemeester shoes#ann demeulemeester boots#demeulemeester#ann demeulemeester official#belgian fashion#belgian fashion designer#antwerp 6#antwerp six#- goth#gothic fashion#goth glam#goth aesthetic#goth style#goth look#newestcool

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belfry of Bruges Bell Tower - 1486

Photography: Andrew Shenouda

#architecture#architektur#architettura#photography#architektura#building#brugge#belgium#belgique#belgian#gothicarchitecture#goth aesthetic#heritage

1 note

·

View note

Text

this is probably the first and only time I'm sharing a piece of myself here.

1 note

·

View note

Note

hi! SUPER interesting excerpt on ants and empire; adding it to my reading list. have you ever read "mosquito empires," by john mcneill?

Yea, I've read it. (Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, basically about influence of environment and specifically insect-borne disease on colonial/imperial projects. Kinda brings to mind Centering Animals in Latin American History [Few and Tortorici, 2013] and the exploration of the centrality of ecology/plants to colonialism in Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World [Schiebinger, 2007].)

If you're interested: So, in the article we're discussing, Rohan Deb Roy shows how Victorian/Edwardian British scientists, naturalists, academics, administrators, etc., used language/rhetoric to reinforce colonialism while characterizing insects, especially termites in India and elsewhere in the tropics, as "Goths"; "arch scourge of humanity"; "blight of learning"; "destroying hordes"; and "the foe of civilization". [Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. October 2019.] He explores how academic and pop-sci literature in the US and Britain participated in racist dehumanization of non-European people by characterizing them as "uncivilized", as insects/animals. (This sort of stuff is summarized by Neel Ahuja, describing interplay of race, gender, class, imperialism, disease/health, anthropomorphism. See Ahuja's “Postcolonial Critique in a Multispecies World.”)

In a different 2018 article on "decolonizing science," Deb Roy also moves closer to the issue of mosquitoes, disease, hygiene, etc. explored in Mosquito Empires. Deb Roy writes: 'Sir Ronald Ross had just returned from an expedition to Sierra Leone. The British doctor had been leading efforts to tackle the malaria that so often killed English colonists in the country, and in December 1899 he gave a lecture to the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce [...]. [H]e argued that "in the coming century, the success of imperialism will depend largely upon success with the microscope."''

Deb Roy also writes elsewhere about "nonhuman empire" and how Empire/colonialism brutalizes, conscripts, employs, narrates other-than-human creatures. See his book Malarial Subjects: Empire, Medicine and Nonhumans in British India, 1820-1909 (published 2017).

---

Like Rohan Deb Roy, Jonathan Saha is another scholar with a similar focus (relationship of other-than-human creatures with British Empire's projects in Asia). Among his articles: "Accumulations and Cascades: Burmese Elephants and the Ecological Impact of British Imperialism." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 2022. /// “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017. /// "Among the Beasts of Burma: Animals and the Politics of Colonial Sensibilities, c. 1840-1940." Journal of Social History. 2015. /// And his book Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (published 2021).

---

Related spirit/focus. If you liked the termite/India excerpt, you might enjoy checking out this similar exploration of political/imperial imagery of bugs a bit later in the twentieth century: Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords” e-flux Journal Issue #115. February 2021.

Amir explores not only insect imagery, specifically caricatures of termites in discourse about civilization (like the Deb Roy article about termites in India), but Amir also explores the mosquito/disease aspect invoked by your message (Mosquito Empires) by discussing racially segregated city planning and anti-mosquito architecture in British West Africa and Belgian Congo, as well as anti-mosquito campaigns of fascist Italy and the ascendant US empire. German cities began experiencing a non-native termite infestation problem shortly after German forces participated in violent suppression of resistance in colonial Africa. Meanwhile, during anti-mosquito campaigns in the Panama Canal zone, US authorities imposed forced medical testing of women suspected of carrying disease. Article features interesting statements like: 'The history of the struggle against the [...] mosquito reads like the history of capitalism in the twentieth century: after imperial, colonial, and nationalistic periods of combatting mosquitoes, we are now in the NGO phase, characterized by shrinking [...] health care budgets, privatization [...].' I've shared/posted excerpts before, which I introduce with my added summary of some of the insect-related imagery: “Thousands of tiny Bakunins”. Insects "colonize the colonizers". The German Empire fights bugs. Fascist ants, communist termites, and the “collectivism of shit-eating”. Insects speak, scream, and “go on rampage”.

---

In that Deb Roy article, there is a section where we see that some Victorian writers pontificated on how "ants have colonies and they're quite hard workers, just like us!" or "bugs have their own imperium/domain, like us!" So that bugs can be both reviled and also admired. On a similar note, in the popular imagination, about anthropomorphism of Victorian bugs, and the "celebrated" "industriousness" and "cleverness" of spiders, there is: Claire Charlotte McKechnie. “Spiders, Horror, and Animal Others in Late Victorian Empire Fiction.” Journal of Victorian Culture. December 2012. She also addresses how Victorian literature uses natural science and science fiction to process anxiety about imperialism. This British/Victorian excitement at encountering "exotic" creatures of Empire, and popular discourse which engaged in anthropormorphism, is explored by Eileen Crist's Images of Animals: Anthropomorphism and Animal Mind and O'Connor's The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856.

Related anthologies include a look at other-than-humans in literature and popular discourse: Gothic Animals: Uncanny Otherness and the Animal With-Out (Heholt and Edmunson, 2020). There are a few studies/scholars which look specifically at "monstrous plants" in the Victorian imagination. Anxiety about gender and imperialism produced caricatures of woman as exotic anthropomorphic plants, as in: “Murderous plants: Victorian Gothic, Darwin and modern insights into vegetable carnivory" (Chase et al., Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2009). Special mention for the work of Anna Boswell, which explores the British anxiety about imperialism reflected in their relationships with and perceptions of "strange" creatures and "alien" ecosystems, especially in Aotearoa. (Check out her “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” Transformations. 2018.)

And then bridging the Victorian anthropomorphism of bugs with twentieth-century hygiene campaigns, exploring "domestic sanitation" there is: David Hollingshead. “Women, insects, modernity: American domestic ecologies in the late nineteenth century.” Feminist Modernist Studies. August 2020. (About the cultural/social pressure to protect "the home" from bugs, disease, and "invasion".)

---

In fields like geography, history of science, etc., much has been said/written about how botany was the key imperial science/field, and there is the classic quintessential tale of the British pursuit of cinchona from Latin America, to treat mosquito-borne disease among its colonial administrators in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. In other words: Colonialism, insects, plants in the West Indies shaped and influenced Empire and ecosystems in the East Indies, and vice versa. One overview of this issue from Early Modern era through the Edwardian era, focused on Britain and cinchona: Zaheer Baber. "The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge." May 2016. Elizabeth DeLoughrey and other scholars of the Caribbean, "the postcolonial," revolutionary Black Atlantic, etc. have written about how plantation slavery in the Caribbean provided a sort of bounded laboratory space. (See Britt Rusert's "Plantation Ecologies: The Experiential Plantation [...].") The argument is that plantations were already of course a sort of botanical laboratory for naturalizing and cultivating valuable commodity plants, but they were also laboratories to observe disease spread and to practice containment/surveillance of slaves and laborers. See also Chakrabarti's Bacteriology in British India: laboratory medicine and the tropics (2012). Sharae Deckard looks at natural history in imperial/colonial imagination and discourse (especially involving the Caribbean, plantations, the sea, and the tropics) looking at "the ecogothic/eco-Gothic", Edenic "nature", monstrous creatures, exoticism, etc. Kinda like Grove's discussion of "tropical Edens" in the colonial imagination of Green Imperialism.

Dante Furioso's article "Sanitary Imperialism" (from e-flux's Sick Architecture series) provides a summary of US entomology and anti-mosquito campaigns in the Caribbean, and how "US imperial concepts about the tropics" and racist pathologization helped influence anti-mosquito campaigns that imposed racial segregation in the midst of hard labor, gendered violence, and surveillance in the Panama Canal zone. A similar look at manipulation of mosquito-borne disease in building empire: Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017. (Basically, some prominent medical schools/departments evolved directly out of US military occupation and industrial plantations of fruit/rubber/sugar corporations; faculty were employed sometimes simultaneously by fruit companies, the military, and academic institutions.) This issue is also addressed by Pratik Chakrabarti in Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (2014).

---

Meanwhile, there are some other studies that use non-human creatures (like a mosquito) to frame imperialism. Some other stuff that comes to mind about multispecies relationships to empire:

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017)

No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers)

Archie Davies. "The racial division of nature: Making land in Recife". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers Volume 46, Issue 2, pp. 270-283. November 2020.

Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022)

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Under Osman's Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail)

The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods, 2017)

Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten Greer, 2020)

Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa: The Human and Nonhuman Creatures of Nigeria (Saheed Aderinto, 2022)

Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka)

#ecology#bugs#multispecies#landscape#indigenous#haunted#temporal#colonial#imperial#british entomology in india#mosquitoes#carceral#tidalectics#intimacies of four continents#carceral geography#pathologization

87 notes

·

View notes