#Booker Prize

Text

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caitríona in conversation at the 2023 Booker Prize presentation

Caitríona’s conversation starts at 21:41

Video 📹 clip from YouTube (link above clip)

Remember… ever since I remember, my mum brought us to the library; that was our weekly thing. We went in and picked four or five books. I grew up in a very small village and it was just having this window into so many places in in the world. — Caitríona Balfe

Brian’s Post from Sunday

#Tait rhymes with hat#Good times#Prophet Song#Paul Lynch#Winner#2023#Booker Prize#YouTube Live#Old Billingsgate#26 November 2023#London#YouTube#My screenrecording

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There are words and words and none mean anything. And then one sentence means everything.”

― Richard Flanagan, The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

#booklr#books#bookblr#fiction#book#quotes#book quotes#quotations#quote#book quote#richard flanagan#the narrow road to the deep north#booker prize#books & libraries#reading#books and reading#bookworm#book lover

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was easy to understand why women feared men with their physical strength and lust and social powers, but women, with their canny intuitions, were so much deeper: they could predict what was to come long before it came, dream it overnight, and read your mind.

- Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

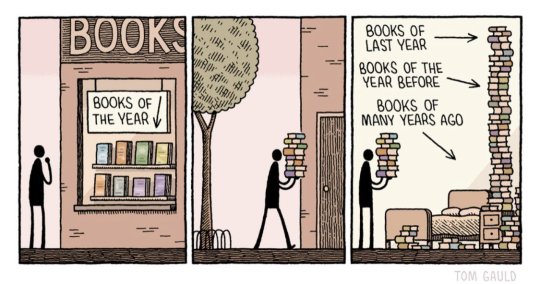

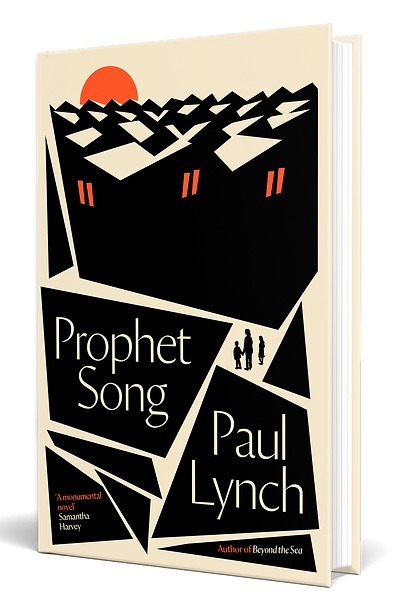

Irish author Paul Lynch has won the 2023 Booker prize for his fifth novel Prophet Song, set in an imagined Ireland that is descending into tyranny. It was described as a “soul-shattering and true” novel that “captures the social and political anxieties of our current moment” by the judging chair, Esi Edugyan.

Canadian novelist Edugyan, who has twice been shortlisted for the Booker prize herself, said the decision to award Lynch the £50,000 prize “wasn’t unanimous” and was settled on by discussion and multiple rounds of voting that lasted “about six hours” on Saturday.

Prophet Song takes place in an alternate Dublin. Members of the newly formed secret police, established by a government turning towards totalitarianism, turn up on the doorstep of microbiologist Eilish asking for her husband, a senior official in the Teachers’ Union of Ireland. Soon, he disappears – along with hundreds of other civilians – and Eilish is left to look after their four children and her elderly father, fighting to hold the family together amid civil war.

“It is with immense pleasure that I bring the Booker home to Ireland,” said Lynch, a former film critic, upon receiving the prize. “I had a moment on holiday in Sicily many years ago where I had this flash of recognition, I knew that I needed to write, and that was the direction my life had to take. I made that decision that day to just swerve, and I swerved. And I’m bloody glad I did.”

His win comes days after violent protests broke out across central Dublin after a stabbing attack outside a primary school that left three children injured. Police said the disorder was caused by a “complete lunatic faction driven by far-right ideology”.

Asked about his reaction to the events, Lynch said that he was “astonished” and at the same time “recognised the truth that this kind of energy is always there under the surface”.

“I didn’t write this book to specifically say ‘here’s a warning’, I wrote the book to articulate the message that the things that are happening in this book are occurring timelessly throughout the ages, and maybe we need to deepen our own responses to that kind of idea,” Lynch said, later adding that he is “distinctly not a political novelist”.

Edugyan said, when asked whether recent events had influenced the judges’ decision, that “at some point in the discussions, maybe for a few minutes, this was introduced, this was discussed”. However, she said that timeliness “was not the reason that Prophet Song won the prize” – the judges simply felt it was a “truly a masterful work of fiction”.

This is the second year in a row that a novel about political conflict has won the prize. In 2022, Shehan Karunatilaka won with The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, set during the Sri Lankan civil war.

“Lynch’s dystopian Ireland reflects the reality of war-torn countries, where refugees take to the sea to escape persecution on land,” wrote Aimée Walsh in an Observer review. “Prophet Song echoes the violence in Palestine, Ukraine and Syria, and the experience of all those who flee from war-torn countries.”

Melissa Harrison called the novel “as nightmarish a story as you’ll come across: powerful, claustrophobic and horribly real” in her Guardian review.

Lynch was born in 1977 in Limerick, grew up in County Donegal and now lives in Dublin. His other novels are Beyond the Sea, Grace, The Black Snow and Red Sky in Morning. He is the fifth Irish author to win the prize, following in the footsteps of Iris Murdoch, John Banville, Roddy Doyle and Anne Enright. The Northern Irish writer Anna Burns won in 2018.

Asked what he would spend the prize money on, Lynch said that “half of it has already gone” on his tracker mortgage.

The keynote speech at the prize ceremony in London was given by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who was released from prison in Tehran, Iran, last year. She discussed the ways in which books helped her when she was in solitary confinement. “When the guard opened the door and handed over the books to me, I felt liberated; I could read books, they could take me to another world, and that could transform my life,” she said.

“One day a cellmate received a book through the post; it was The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, translated into Farsi,” she said. “Who thought a book banned in Iran could find its way to prison through the post?”

The other titles shortlisted for the prize were The Bee Sting by Paul Murray, Western Lane by Chetna Maroo, This Other Eden by Paul Harding, If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery and Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein.

Alongside Edugyan on this year’s judging panel was actor Adjoa Andoh, poet Mary Jean Chan, writer and academic James Shapiro and actor Robert Webb. At the ceremony, Andoh read an extract from the 1990 Booker prize-winning novel Possession by AS Byatt, who died earlier this month.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The longlist for the 2024 International Booker Prize is as follows:

Not a River by Selva Almada, translated by Annie McDermott

Simpatía by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón, translated by Noel Hernández González and Daniel Hahn

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated by Michael Hofmann

The Details by Ia Genberg, translated by Kira Josefsson

White Nights by Urszula Honek, translated by Kate Webster

Mater 2-10 by Hwang Sok-yong, translated by Sora Kim-Russell and Youngjae Josephine Bae

A Dictator Calls by Ismail Kadare, translated by John Hodgson

The Silver Bone by Andrey Kurkov, translated by Boris Dralyuk

What I'd Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, translated by Sarah Timmer Harvey

Lost on Me by Veronica Raimo, translated by Leah Janeczko

The House on Via Gemito by Domenico Starnone, translated by Oonagh Stransky

Crooked Plow by Itamar Vieira Junior, translated by Johnny Lorenz

Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener, translated by Julia Sanches

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

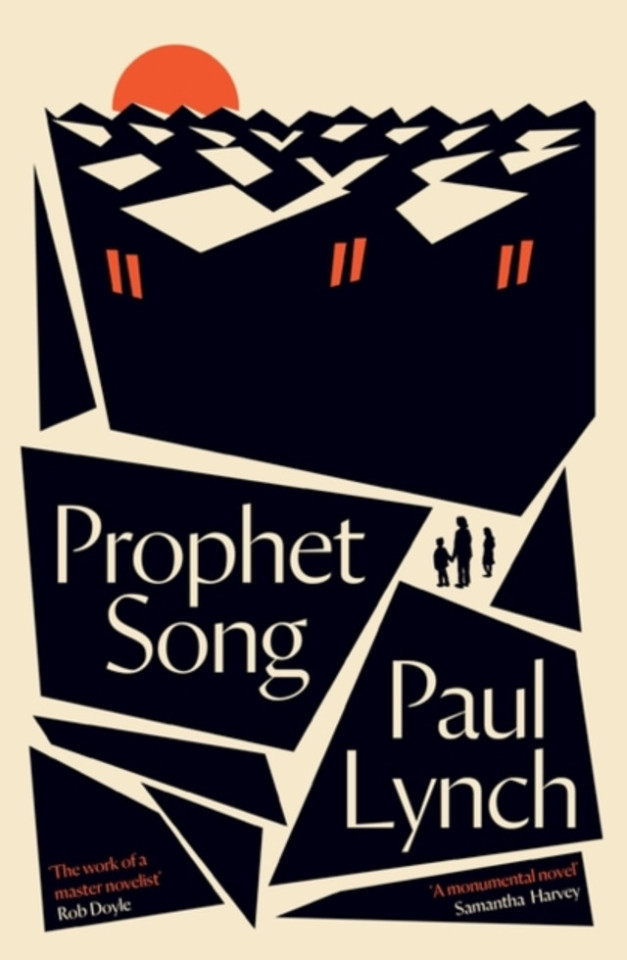

Afternoon reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ 'Where does a story begin, Willie? I asked.

For a while he did not say anything.

Then he shifted in his chair. 'Where does a wave on the ocean begin? he said.

Where does it form a welt on the skin of the sea, to swell and expand and rush towards shore?' ”

— Tan Twan Eng, The House of Doors

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are both scientists, Eilish, we belong to a tradition but tradition is nothing more than what everyone can agree on – the scientists, the teachers, the institutions, if you change ownership of the institutions then you can change ownership of the facts, you can alter the structure of belief, what is agreed upon, that is what they are doing, Eilish, it is really quite simple, the NAP is trying to change what you and I call reality, they want to muddy it like water, if you say one thing is another thing and you say it enough times, then it must be so, and if you keep saying it over and over people accept it as true – this is an old idea, of course, it really is nothing new, but you’re watching it happen in your own time and not in a book.

- Prophet Song, Paul Lynch

#prophet song#reading#paul lynch#booker prize#vintage#darkacademia#literature#classic lit#light academia#books#academia#dystopia

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

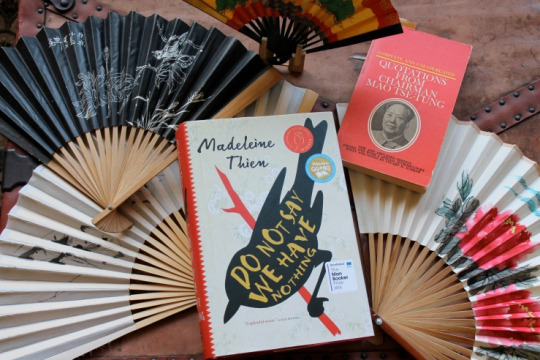

Do Not Say We Have Nothing by Madeleine Thien - Review

rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (3.75)

Do Not Say We Have Nothing is a story about two families who despite being physically separated, are intimately connected to each other. It’s a book about how the political climate of a country can break or make a person, but that, in the end, we come back to the things that have always given us comfort.

It’s clear to me that the author appreciates music deeply, the way music is described in these pages is unreal. I had never seen music come alive this way before, music moves the narrative and mirrors our characters struggles not only within themselves but with the society they are inserted in.

The novel is set in two different timelines, the 50’s-60’s and the 90’s-2000’s. I’ve found really interesting how China’s political stances are explored in both timelines.

“How easy it was to mistake your brother for a traitor or your beloved for an enemy, to fear that you yourself were born in the wrong moment of history.”

This is a historical novel that sets to explore how Chairman Mao’s government affected the people of China and later on why people started rioting. I wish I had more knowledge about this period in China, maybe the novel would have made more sense to me and perhaps the language would not have seemed so dull at times. The author goes into great detail in how the lives of simple people would have been during that time. The famine, the torture, the “distribution of wealth” is heavily explored in this book.

It is an interesting topic however I think the language could’ve been more accessible and maybe less information would’ve led to a more cohesive story with less filler sentences.

At times it felt as if I was rereading the book due to how repetitive it got because the two timelines the novel explores are so interconnected and it’s basically history repeating itself.

One thing I think it was done well was how the characters were afraid to speak up, that seems the logical thing to do in an authoritarian regime. If the characters were suddenly speaking against the government freely it would’ve been incoherent given the time. However, the book addresses the issues without compromising the characters (the ones that aren’t tortured anyway) while still making a clear social commentary.

“I felt she saw into me, past every facade and flourish, and that the more she knew me, the more she loved me. I was too young, then, to know how lasting this kind of love is, how rarely it comes into one’s life, how difficult it is to accept oneself, let alone another. I carried this security—Ai-ming’s love, the love of an older sister—out of my childhood and into my adult life.”

One of the high points of the book is the relationships between the characters, the deep love they feel for each other, whether familiar, platonic or romantic. We see how these characters evolve in each other’s influence and how some people shape our lives.

There are a lot of characters in this book and maybe some people can’t connect with most of them because of their multitude, but I’d argue that is the point. In a communist China you’d have to hide yourself a lot of the times, not speak aloud and follow what the Party said. In a way I feel as if the characters’ inner monologue is exactly that, them convincing themselves and the reader that they are loyal to their country, which translates to being loyal to the Party, even in thoughts.

“Why is it that we can’t choose our own jobs? What right does the government have to keep a private file on me? (…) What illegal thoughts. The ones who should die…But actually, why should anyone’s thoughts be illegal?”

I think this book would benefit from a reread, it feels to me that if I knew what was going to happen I would’ve enjoyed my reading experience a bit more. I love how literature and music are so interconnected in the story and although it has a bit of filler it’s an enjoyable read (especially the second part).

#booklr#literature#book review#books & libraries#book quotes#books#reading#my reviews#book reccs#book recommendations#do not say we have nothing#madeleine thien#booker prize#chinese literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

PaulLynchWriter

Video 📹 from Instagram

Remember her congratulating Paul Lynch, 2023 Booker Prize winner?

Brian’s related posts 1 2 3 4

#Tait rhymes with hat#Good times#Prophet Song#Paul Lynch#Winner#2023#Booker Prize#YouTube Live#Old Billingsgate#26 November 2023#London#Instagram Story#My screenrecording

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I write the names they become real, not just statistics. When I write the names they become real again. It’s almost like they get a few more seconds here. Do you know what I mean? I would never be able to make up this many names. The names have to be real. They have to be real. Don’t they?

- The Trees, Percival Everett.

#booker prize longlist 2022#booker prize#the trees quote#percival everett#american southwest#hate crimes#racial crimes#lynching#black lives matter

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 2024 longlist for the International Booker Prize is announced!

”The list signals a second ‘boom’ in Latin American literature, and ‘emphasises our common humanity in a violent world'”

#longlist#booker prize#books#bookworm#bookish#bibliophile#book lover#bookaddict#reading#book#booklr#bookaholic#reader#to read#books and reading#bookblr#reading recommendations#reading resolutions#reading list

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, it’s that time again: next Sunday the winner of this year’s Booker prize will be announced. Everyone has their favourites and it’s easy to carp about novels the judges missed, but the truth is we don’t know which ones they consider – the list of 150-odd titles is never made public and probably any number of subterranean factors determines its makeup; a few years ago I heard of at least one big-name British author, an obvious contender, who refused to be considered. And awards – now brands in themselves – seek to establish their own identities: was Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead crossed off the list after winning the Pulitzer and Women’s prizes for fiction?

One of the judges, Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro, recently said he isn’t comfortable with historical fiction, which perhaps had something to do with the absence from the longlist of two of the year’s most feted novels, Zadie Smith’s The Fraud and Tom Crewe’s The New Life. True, one historical novel has made the shortlist: This Other Eden (Hutchinson Heinemann), by Pulitzer-winning US author Paul Harding – but that’s no surprise: the chair of judges, Esi Edugyan, says how good she thinks it is on the cover of the book itself, published last February.

Drawing on the true story of the forced eviction of a mixed-race island community in New England before the first world war, it may have Edugyan’s vote but I think it’s a novel that’s hard to love. We follow various descendants of a freed slave as a well-meaning missionary, privately racist, attempts to spare one of them – a gifted young painter who happens to pass as white – by having him moved to a friend’s estate on shore.

At the core of what ensues is his doomed romance with his landlord’s Irish maid. But Harding relies on laboriously laid slabs of narration to generate dramatic irony as we see events from different points of view – the painter’s, the maid’s, then his family’s, confronted with her pregnancy as she visits the island in search of the painter’s past.

In his previous novel, Enon, Harding found a measure of comedy even in the plight of a father mourning the death of his teenage daughter in a road accident. Nothing to laugh about in This Other Eden, a mark of Harding’s sense of responsibility to his painful material. For sure, he wrings pathos from the injustice and horror from the climactic violence but the novel never justifies its own interest in the spectacle.

I have similar unease about Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song (Oneworld), set in a contemporary Ireland gradually riven by war between a totalitarian regime and insurgent rebels. It follows a Dublin mum of four after the arbitrary detention of her trade unionist husband. The focus is on her trials keeping the breakfast-to-bedtime show on the road amid a descent into hell, from abductions to air raids. That focus gives the novel its convincing frisson – as bombing intensifies, the protagonist’s father rings her up complaining about his neighbour’s ivy – but it also locates it firmly as thought experiment. It’s jarringly apolitical – there’s no obvious history to what’s going on – and ultimately there’s something almost obscenely decadent to its invitation to sympathise with sea-crossing refugees by recasting them as middle-class Europeans. When Eilish thinks it’s “as though some filmed transparency of a foreign war has been placed upon an image of the city”, the line catches exactly what Lynch is up to.

Still, its explosive set pieces have a visceral spell undimmed by rereading, and any sense of unease it fosters may count in its favour – whatever else it is, Prophet Song is a novel to argue about.

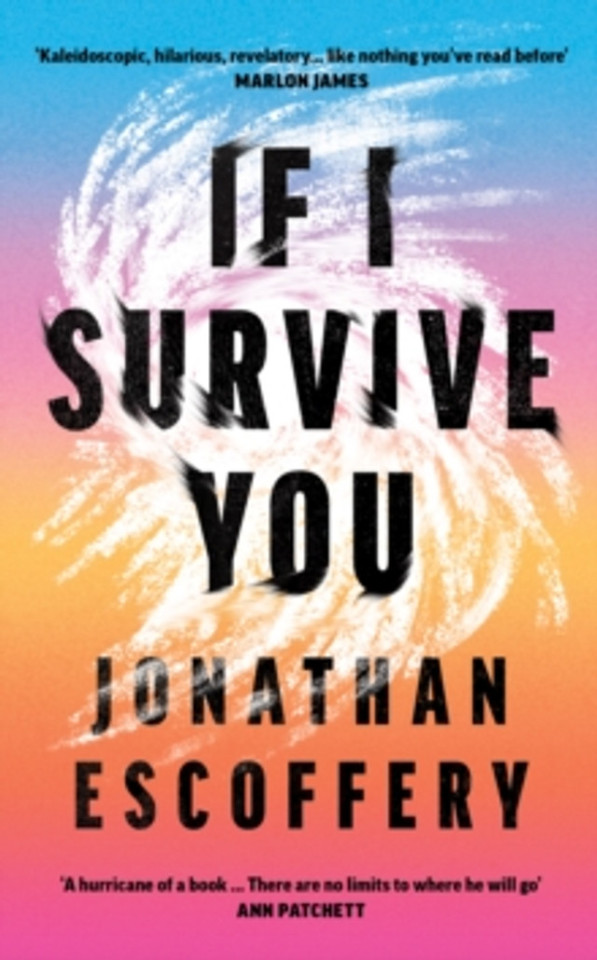

I preferred quieter books on the list. Kudos to the judges for spotlighting If I Survive You (Fourth Estate), a thrilling debut by US writer Jonathan Escoffery (a former student of Percival Everett, shortlisted last year for The Trees) that starts as an exploration of second-generation American identity by way of a Jamaican-descended literature graduate, Trelawny, whose morale – already battered by being second-best, at least in his father’s eyes, to his tree surgeon brother Delano – takes another hit by his graduating post-recession. He finds himself doing crazy things for money, not least being paid by a woman who puts out a classifieds ad looking for someone to hit her.

With much tenderness in the gulf between father and son, this would be a worthy winner. It’s funny, sad, always toying with assumptions about race. Don’t be misled by the opening sequence, which feels like an exercise in voice, as the second-person narration explores the contortions of internalised racism. In later sections Escoffery shines through as a first-rate scene-maker with a wicked knack for jeopardy: witness Delano’s catastrophically ill-conceived bid to retrieve an impounded cherry-picker so he can take on a job. In the title story, Trelawny winds up part of a rich white couple’s twisted sex game (and yes, this is a linked story collection, openly advertised as such on the dust jacket, a first for a prize now awarded to “longform fiction”).

Another debut that is a revelation is Western Lane (Picador) by Chetna Maroo, the only British writer here (hard not to note that she got her break from magazines in the US and Ireland). Families were clearly a hot topic for this year’s judges, but the simplicity of this book stands apart. It is narrated by 11-year-old Gopi, youngest of three daughters in an Indian family living in south London, whose father schools her in squash at a local leisure centre in the year after their mother’s death. The story evolves as she practises to compete in a tournament: the power of the novel lying in what goes unsaid between Gopi and Pa, between her and an older boy she hits with at the leisure centre, between the sisters, between her and the childless aunt and uncle in Edinburgh where she’s expected to move.

This is a beautiful tale of family – and sport. A moving yet non-maudlin novel about grief, it’s told in plain language electric with feeling, nicely catching the narrator’s incomplete understanding of her situation without making her a figure of irony. A real feat: if the metric is the ratio of number of words to emotion generated, Western Lane wins.

Paul Murray’s mighty The Bee Sting (Hamish Hamilton) is a book nearly big enough to contain the others on the shortlist, and it features many of their themes, from filial misunderstanding to civilizational collapse – or its looming shadow, seen in the ultimately catastrophic prepping of its beleaguered patriarch, a car salesman sunk by the recession, wed to the class-climbing daughter of a bare-knuckle boxer. A 650-page soap opera with a clockwork plot whose delicate mechanism you can’t hear tick: if it wins the Booker there will be a lot of delighted readers finding it under the Christmas tree.

It’s so obviously the best novel here – but will the judges talk themselves out of it? A sceptical 3,000-word review in the London Review of Books shows what might happen if you’re encouraged to think about it for too long; and remember, too, the Booker doesn’t reward the best novel of the year – not exactly – it’s more the book that survives a process that entails being read and discussed again and again over the better part of nine months.

It’s because of this that I wonder if Prophet Song will get the nod – or Sarah Bernstein’s Study for Obedience (Granta). A Canadian living in Scotland, listed this year as one of Granta’s best young British novelists, she is also winner of Canada’s prestigious Scotiabank Giller prize (twice won by Edugyan). Study for Obedience has nagged me since I read it in March. I didn’t like it then and I don’t love it now but in a list of novels about family it stands apart – an almost spectrally vague existential brainteaser soaked in 20th-century bloodshed. I can’t tell you what the novel is about, exactly, and that’s why I think it bears scrutiny.

The narrator is an unnamed woman who moves to an unspecified country to take up her creepy elder brother’s affairs as a housekeeper, where her duties extend to soaping his back, and she’s permitted to watch TV only by lipreading (he says subtitles affect the play of light in the room). Strange encounters with locals never quite bloom into confrontation. Instead of drama we have discomfort and dread: between the lines lies the genocide and exile of the protagonist’s ancestors.

Trapping us in an isolated consciousness, the winding narration is full of comma-spliced caveats and double negatives that make it purposely awkward to place.

How to measure this against, say, the arrowlike flight of Maroo’s sentences aiming at the heart? I don’t envy the judges. Where they have by and large selected novels that show an uncomplicated faith in the pleasure of storytelling, Bernstein’s is the book that makes narrative a problem – the reader’s problem, some might say. But it just might be declared best on 26 November by judges who can’t be expected to spend a year agreeing with one another about how great The Bee Sting is.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not a book awards girlie but I will say if you were considering reading anything off the Booker Prize list then I'd highly recommend Boulder by Eva Baltasar

It's a hundred-ish pages of internal monologue about what happens when a restless soul almost accidentally settles down, and how love and resentment can exist in the same space in your chest when two people don't want the same things. It's beautifully written and the way the narrative voice translates her life through her love of food and the sea is just 🤌🤌🤌

#and i love this cover sm#the writing is so good#its not very often i read a translated novel and dont feel like im missing some intrinsic details in the sub text#the translater did a beautiful job#boulder#eva baltasar#translated by julia sanches#i will absolutely be seeking out more by this translator#booklr#book recs#booker prize

19 notes

·

View notes