#David V. Groupé

Text

REVIEW: "The Almost True and Truly Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter" at Oldcastle

REVIEW: “The Almost True and Truly Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter” at Oldcastle

View On WordPress

#Anne Undeland#Bennington VT#Christine Decker#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Gail Burns#Gail M. Burns#Gary Allan Poe#Henry Trumbull#Herman Melville#Israel Potter#Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile#Israel R. Potter#Josh Aaron McCable#Kristine Schlachter#Nathan Stith#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#Richard Howe#Richard St. Laurence#Roy Hamlin#The Almost True And Truly Remarkable Adventures Of Israel Potter#The Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel R. Potter#Ursula McCarty

1 note

·

View note

Text

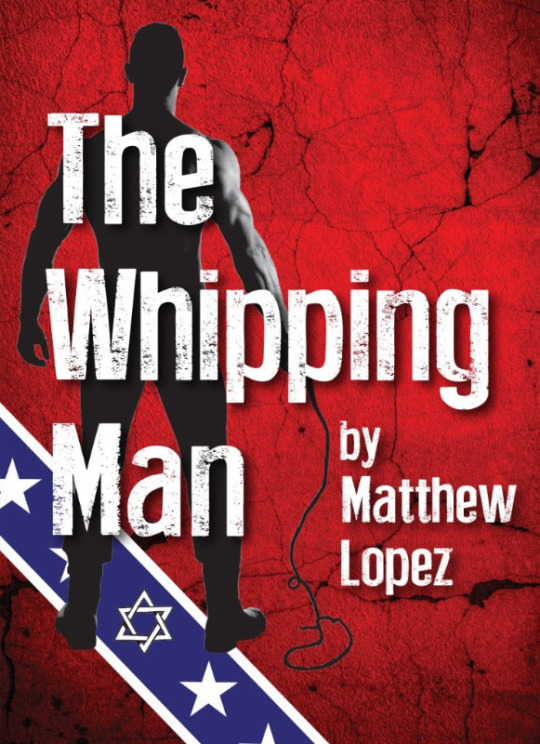

REVIEW: "The Whipping Man" at Oldcastle

REVIEW: “The Whipping Man” at Oldcastle

View On WordPress

#Bennington VT#Brandon Rubin#Carl Sprague#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Herb Parker#Justin Pietropaolo#Matthew Lopez#Oldcastle#Oldcastle Theater#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Roseann Cane#The Whipping Man#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Text

REVIEW: "Proof" at Oldcastle Theatre Company

REVIEW: “Proof” at Oldcastle Theatre Company

View On WordPress

#Bennington VT#Claire#Cory Wheat#David Auburn#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Ethan Botwick#Gail Burns#Gail M. Burns#Gary Allan Poe#Halley Cianfarini#Oldcastle Theatre Company#Proof#Richard Howe#Talley Gale#Ursula McCarty#Wm. John Aupperlee

0 notes

Text

REVIEW: "Brighton Beach Memoirs" at Oldcastle

REVIEW: “Brighton Beach Memoirs” at Oldcastle

View On WordPress

#Anthony Ingargiola#Anthony J. Ingargiola#Bennington VT#Brighton Beach Memoirs#Cory Wheat#D. J. Gleason#David V. Groupé#Eli Ganias#Kate Kenney#Kristen Herin#Liz Raymond#Nathan Stith#Neil Simon#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Richard Howe#Sarah Corey#Sophia Garder#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Text

by Gail M. Burns

The minute that Sarah Corey makes her entrance as Neil Simon’s indomitable matriarch, Kate Jerome, Oldcastle Theatre Company‘s production of Brighton Beach Memoirs you know who’s in charge here. This is Corey’s second Oldcastle turn as Kate, having played an older iteration in Broadway Bound in 2017, and for those of us lucky enough to have seen both productions, it is like coming home. Even if your mother wasn’t Kate, Kate is your mother for the two and a half hours you will spend with her.

Brighton Beach Memoirs is the first in Simon’s trilogy of plays about the Jerome Family. It is September of 1937, and Eugene (D. J. Gleason), our narrator, is 15, while his brother Stanley (Anthony Ingargiola) is 18, just out of high school and into the work force. Their father Jack (Eli Ganias) is a garment cutter for a manufacturer of ladies’ raincoats, who also takes on other odd jobs to support his family in the Great Depression. Their mother Kate is a homemaker, and for the past three years their home has also included Kate’s widowed sister, Blanche Morton (Sophia Garder), and Blanche’s two daughters, Nora (Kate Kenney), 16, and Laurie (Kristen Herink), 13.

The family owns a three bedroom house in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn. They are Polish and Jewish and they worry daily about family back home as Hitler advances through Europe. Everyone scrimps and save and true poverty is always kept just at bay, but at heart the Jeromes are proud that they can manage on what they do have.

All of that managing falls on solidly on Kate’s shoulders. In addition to corralling four teenagers, she is the emotional prop for her depressed sister and the physical shield for her over-stressed and ailing husband.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Corey’s performance is absolutely solid and immediately appealing. She gets this woman, her considerable strengths and her failings. Simon has crafted the character with tremendous love, and Corey channels it beautifully.

Gleason’s Eugene is bursting with the sexual and physical energy with which a boy of that age is possessed, and his antics provide most of the comic relief in what is otherwise quite a sober family drama. I often have a hard time with adults playing children, and I felt that a bit with Herink’s Laurie, but Gleason had me completely convinced that he was still in high school and torn between his love for baseball and ice cream, and his new found frenzy for the female form.

Ingargiola brings a warmth and genuineness to the role. His Stanley is a terrific Big Brother and a loving son, even though he is also just barely an adult and subject to the failings of his age. Ganias’ Jack connects well with the rest of his family – even his sister-in-law – providing a strong father figure even as he struggles to stay healthy enough to fulfill his bread-winning role.

Garder’s face is just a mask of tragedy as the bereaved Blanche, a woman who invested her whole self into her marriage only to be left rudderless at its sudden demise. But like her sister Kate, she is devoted to her children, even though she lacks the strength of her convictions to guide them towards adulthood. I felt Kenney was miscast as Nora. She didn’t look like she could be Garder’s daughter or Herink’s sister, and she looked to mature to pass as 16.

At a time when we are hearing a lot of rhetoric about who is “an American” with various unflattering stereotypes being pinned to different ethnic groups, it is hard to hear Kate’s disgust and anger at the Irish family who lives across the street and their son who hopes to date her sister. Earlier in the 20th century discrimination was strong against both the Irish and the Italian, and to a lesser extent the German, immigrants to New York City. It is interesting that Kate, who understands so clearly what discrimination has done to her ancestors, cannot understand that she is perpetuating an identical violence against another ethnic group.

Richard Howe’s manages to pack an awful lot of distinct rooms into the Oldcastle performance space, creating the cheek-by-jowl intimacy that the two families sharing one home must feel. Stith and his actors are careful to use each doorway at the appropriate time for the appropriate purpose, so you soon catch on to the condensed floorplan of the house. Ursula McCarty’s costumes are good, but they veer heavily towards purple, particularly in the second act, which is puzzling.

Like Tennessee Williams’ A Glass Menagerie, Brighton Beach Memoirs is a memory play, a family seen through the eyes of the son. While it is generally accepted as a semi-autobiographical work, there aren’t actually many direct parallels to Neil Simon’s own family. He said himself that the Jeromes were “the family I wished I’d had instead of the family I did have.” So we can’t look at them as direct representation of the Simons, but it is clear that Simon loved the Jeromes like family. Oldcastle loves them too, and it is wonderful that they have brought them back to Bennington in this strong and proud production,

Brighton Beach Memoirs by Neil Simon, directed by Nathan Stith, runs July 12-28, 2019, at the Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, VT. Set design by Richard Howe; lighting design by David V. Groupé; sound design by Cory Wheat; and costume design by Ursula McCarty. Stage Manager Liz Raymond. CAST: Sarah Corey as Kate, D. J. Gleason as Eugene, Anthony J. Ingargiola as Stanley, Eli Ganias as Jack., Sophia Garder as Blanche, Kate Kenney as Nora, and Kristen Herink as Laurie. The show runs two and a half hours with one intermission. For tickets and more information visit http://oldcastletheatre.org/ or call 802-447-0564.

REVIEW: “Brighton Beach Memoirs” at Oldcastle by Gail M. Burns The minute that Sarah Corey makes her entrance as Neil Simon’s indomitable matriarch, Kate Jerome, …

#Anthony Ingargiola#Anthony J. Ingargiola#Bennington VT#Brighton Beach Memoirs#Cory Wheat#D. J. Gleason#David V. Groupé#Eli Ganias#Kate Kenney#Kristen Herin#Liz Raymond#Nathan Stith#Neil Simon#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Richard Howe#Sarah Corey#Sophia Garder#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Photo

Oldcastle Theatre Company Presents “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” The most famous and momentous day in American theatre history is Eugene O'Neill's remarkable semi-autobiographical play…

#Bennington VT#Brendan McGrady#Christine Decker#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Eugene O&039;Neill#Long Day&039;s Journey into Night#Martin Jason Asprey#Nigel Gore#Oldcasstle Theatre Company#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#OTC#Piper Goodeve#Richard Howe#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Text

by Gail M. Burns

David Auburn’s Proof burst on the national consciousness nearly twenty years ago – winning Tonys and a Pulitzer and being made into a big budget, star-studded film – so the initial flurry of professional and amateur productions across the country has run its course and the play is ripe for revisiting in the #metoo era.

A simple play about complex subjects, Proof centers on 25-year-old Catherine (Talley Gale) who has just lost her widowed father, Robert (Richard Howe), a brilliant mathematician at the University of Chicago, after years of mental illness during which she was his sole caregiver. Her only sibling, older sister Claire (Halley Cianfarini), has opted for a high-powered career in Manhattan, but of course Claire is headed home for the funeral. Also in the mix is Hal (Ethan Botwick), a young professor of Mathematics at the University who was mentored by Catherine and Claire’s father, and who is going through the late professor’s effects to see if any important and undiscovered research survives him.

Claire and Hal begin a relationship, and she gives him a notebook containing an astonishing mathematical proof that she claims she wrote. But Claire doesn’t even hold an undergraduate degree, her studies having been interrupted by her father’s illness and her decision to care for him, and she also seems to have inherited some of his mental instability. Can she prove that the proof is her work and not a last burst of brilliance from her father?

At Oldcastle Eric Peterson has directed a gentle, low-key but deeply engrossing production. Because there is less high drama, the characters come across as more realistic. Gale, who is on stage nearly non-stop, presents Catherine as exhausted and grief stricken – after all these years of dealing with her father’s non-lethal mental illness it is a sudden cardiac event that carries him off – but not mentally unbalanced. There is a seismic shift for a caregiver when they suddenly wake up one morning and no one needs them anymore. Catherine is not only unmoored emotionally, but because was a caregiver during the years most people spend finding themselves and establishing a career, she also has no sense of herself separate from her father – except for her proof, which she worked on in the wee hours of the night, the only time when her father didn’t demand her full attention.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Gale literally twists herself into pretzels trying to simultaneously hug herself and render herself as small as is humanly possible. But when she and Hal connect and she gives him her most valuable possession, the thing that establishes her as someone other than her father’s daughter, we see the relative freedom and joy in her movements.

Botwick’s Hal is equally physically restricted. Like Catherine, he has lived in Robert’s professional shadow, – before he was 25 Robert had already made two discoveries that changed the course of modern mathematics. Both worry that the adage that a mathematician’s best years are over by the time he or she is 25 – in other words at about the age they receive their doctorate and embark on their academic career – is true. Have Catherine and Hal’s best years already passed? Hal sees himself as a mediocre mathematician and being able to discover and publish a posthumous proof of Robert’s could make his career. The likelihood of the proof Catherine gives him being hers and not her father’s seem slim…

Cianfarini’s Claire is all yuppie bonhomie. Freshly ground gourmet coffee, jojoba crème rinse, and an engagement to her equally upwardly mobile boyfriend form the center of her world. Accepting early that she has inherited only a small portion of her father’s mathematical skills, she has settled into a career as a currency analyst. She acknowledges that Catherine has inherited far more from their father – but worries whether that is a good thing.

Howe’s performance as Robert was a bit of a disappointment. I described Peterson’s production as low key, but in Howe’s case we get little sense of Robert’s illness, his brilliance, or his neediness. Whether there is a physiological connection or not, mental illness and great genius often coincide. This and the deep connection between Robert and Catherine – and we see Robert only in Catherine’s memories and imagination – are lacking.

On my previous encounters with this play I didn’t see the focus on the relationship between Catherine and Hal as central to the plot, but now it takes on a different complexion. At previous production I can remember thinking Hal was quite the villain, but director Eric Peterson makes it clear here that Catherine and Hal are genuinely attracted to each other, and that neither is using the other for ulterior motives. In fact, I don’t think I have ever seen a more engaging love scene than the one Gale and Botwick enacted at the end of Act I.

The other bit of gender politics in the play is the issue, which is still the case, that the majority of mathematicians are male. That a woman, and a young, uncredentialed woman at that, could best the “guys” at their game raises all sorts of toxic masculine reactions, which are played only subtly here.

When you enter the theatre you are greeted by Wm. John Aupperlee’s set depicting the back deck of the house Robert and Catherine share, adorned with Cory Wheat’s projection. I say adorned because as soon as the initial projection – an astonishing black and white trompe-l’œil image of the rear of the house – is switched for more subtle sunlight-through-the-leaves patterns, as it must be or the actors would be performing with blotchy projections all over them, the “house” resolves into nothing but a matte black wall with a door in it. The house projection returns during scene changes, but every time it vanishes again you feel a sense of loss.

It took me until well into Act II to understand that that one door – through which people seemed to access both the interior of the house and the outside world – was meant to be the back door of the house and that there was an unseen front door as well. In other words when people “left the house” they were going in through the back door and then out through the front door. In my mind exits to the outside world should have been made off of the deck, stage left, and indeed occasionally they were. When the critic has to spend a long while pondering a door there is something wrong with the set and/or the direction.

Ursula McCarty’s costumes subtly conveyed character and socio-economic rank while offering freedom of movement. The matter of the vanishing house aside, Wheat’s projections were fine, as was David V. Groupé’s lighting. Wheat is also credited with the sound design, which consisted mostly of an increasingly loud and insistent recording of The Sound of Silence played during scene changes. I usually like that song…

My technical quibbles aside, this a strong and moving production of a thought-provoking play. If you saw a production a decade or so ago, I encourage you to revisit it. And take along a teenage or twenty-something woman while you are at it. There is good fodder for debate and discussion on the ride home.

Proof by David Auburn, directed by Eric Peterson, runs August 31-September 9, 2018, at the Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, Vt. Set design by Wm. John Aupperlee; costume design by Ursula McCarty; lighting design by David V. Groupé; sound and projections by Cory Wheat; stage management by Gary Allan Poe. CAST: Richard Howe as Robert, Talley Gale as Catherine, Halley Cianfarini as Claire, and Ethan Botwick as Hal.

For ticket reservations or additional information contact Oldcastle Theatre at www.oldcastletheatre.org or 802-447-0564.

REVIEW: “Proof” at Oldcastle Theatre Company by Gail M. Burns David Auburn’s Proof burst on the national consciousness nearly twenty years ago – winning Tonys and a Pulitzer and being made into a big budget, star-studded film - so the initial flurry of professional and amateur productions across the country has run its course and the play is ripe for revisiting in the #metoo era.

#Bennington VT#Claire#Cory Wheat#David Auburn#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Ethan Botwick#Gail Burns#Gail M. Burns#Gary Allan Poe#Halley Cianfarini#Oldcastle Theatre Company#Proof#Richard Howe#Talley Gale#Ursula McCarty#Wm. John Aupperlee

1 note

·

View note

Text

by Roseann Cane

In the days following the end of the Civil War, a young Confederate soldier named Caleb (Justin Pietropaolo) painfully makes his way into his once-grand Richmond family estate to find the place in ruins. Caleb, too, is in ruins: a bullet in his leg has been left untreated, and the infection has become gangrenous. He collapses and is soon discovered by another member of the household, Simon (Herb Parker), a slave formerly owned by Caleb’s family, who is waiting for his own family’s return. They are soon joined by another former family slave, John (Brandon Rubin), who bears food and wine he has ransacked from nearby houses.

Simon quickly determines that to save Caleb’s life, he and John must amputate the young man’s leg. (While this scene is certainly distressing, the audience is spared any gore; we do feel the symbolism as well as the physical and psychic pain of the surgery, which creates an important plot point.) Over the next couple of days as Caleb recovers, the three men taking shelter in this shell of a house are faced with the tasks of attempting to reestablish their relationships while exploring the significance of dependence and independence, slavery and freedom. Another layer of complexity is soon revealed: Caleb’s family is Jewish, and the family slaves are Jews as well.

In The Whipping Man, playwright Matthew Lopez has created a gripping examination of the consequences of slavery and the real meaning of freedom in the United States of America. The play may be talky and nearly overloaded with expository dialogue, but Parker, Pietropaolo, and Rubin’s performances are fiery and feelingful, and we become transfixed by the action onstage.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

As it happens, Caleb’s homecoming coincides with Passover, the Jewish festival that celebrates the exodus of Jews from Egypt, and their liberation from slavery. Simon insists that the three celebrate with a seder, the ritual feast during which the story of Exodus is read and foods symbolic of the Exodus are shared. Participants take turns reading the Haggadah (the text that describes the Exodus), and although Simon prizes the Haggadah he owns, he is unable to read. No matter: he knows enough of it by heart.

Parker’s vibrant recitation of the Haggadah, and his passionate rendition of “Go Down Moses,” which he sings during the seder, are deeply affecting. The ardor of this actor suffuses his entire performance, and he is riveting. Pietropaolo and Rubin are equally well cast and embody their roles powerfully. As two men struggling with secrets, their contrast with the big-hearted, steadfast Simon tugs at the hearts and minds of those of us watching the play unfold, and steers us to understand the necessity of confronting the bleakest chapters of American history.

Director Eric Peterson shows sensitivity and skill, moving the actors and action along at a steady pace, no small accomplishment with this prolix yet simmering script. Carl Sprague’s set design, at once wistful and brutal, captures the time, place, and history of this America very well indeed. (There is one problem that I hope he will solve: when an actor exits through an upstage door, he is in plain view of the audience when the door is closed and the actor walks through a curtain offstage.) David V. Groupé’s lighting design and Cory Wheat’s sound design conspire potently to create a menacing thunderstorm that underscores the upheaval within the play. The costumes designed by Ursula McCarty seem utterly authentic, and serve the play very well.

I found it jarring, to put it mildly, that a recording of Pete Seeger singing “We Shall Overcome” erupted as the cast appeared for their curtain call. I imagine Peterson was attempting to communicate that to this day, African-Americans in our country have not nearly achieved full civil rights; that is sadly true. But I would suggest that after sitting through two intense acts of a show that takes place in 1865, right after the Civil War, the audience is intelligent and sensitive enough to grasp the current parallels. Moreover, Pete Seeger’s version of “We Shall Overcome” is firmly grounded in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. Hearing it at the close of The Whipping Man robs us of our suspension of disbelief, our participation in an intimate event from 150 years ago. I think a song from that period would have served the play as well as Parker’s soul-stirring performance of “Go Down Moses” did.

As Simon declares in the play, “You lose your faith by not asking questions.” The act of questioning is a central tenet of Judaism, but the statement has a universal resonance. I would suggest that we also lose our freedom by not asking questions, and therein lies one more example of the importance of the gift Lopez has given us with this play.

The Whipping Man by Matthew Lopez, directed by Eric Peterson, runs July 13-22, 2018, at the Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, VT. Scenic design by Carl Sprague, lighting design by David V. Groupé, sound design by Cory Wheat, costume design by Ursula McCarty. CAST: Justin Pietropaolo as Caleb, Herb Parker as Simon, and Brandon Rubin as John.

Tickets $12 for students with ID; $39 general admission; $50 premiere seating; $65 VIP seating. For additional information or reservations call 802-447-0564 or visit the theatre’s website: www.oldcastletheatre.org.

REVIEW: “The Whipping Man” at Oldcastle by Roseann Cane In the days following the end of the Civil War, a young Confederate soldier named Caleb (Justin Pietropaolo) painfully makes his way into his once-grand Richmond family estate to find the place in ruins.

#Bennington VT#Brandon Rubin#Carl Sprague#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Herb Parker#Justin Pietropaolo#Matthew Lopez#Oldcastle#Oldcastle Theater#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Roseann Cane#The Whipping Man#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Text

by Gail M. Burns

From his perch in 1986, Neil Simon looked back to 1947 and wrote a play about the future. All the characters in Broadway Bound, the final installment in his quasi-autobiographical trilogy of plays about the Jerome family, is teetering on the verge of the precipice of change. The young people, sons Eugene (Anthony J. Ingargiola) and Stanley (Robbie Rescigno), are reaching eagerly for their future, filled with the promise of romance, adventure, and success as comedy writers. Their father, Jack (Jason Asprey), is about to leave his wife and family, something their mother, Kate (Sarah Corey), knows and may or may not be ready for. And Kate’s father, Ben (Richard Howe), is clinging to his life in Brooklyn as his wife prepares to move to a retirement community in Florida.

It is a joy to see Ingargiola return to the Oldcastle stage after his thoroughly winning portrayal of Huck Finn in last season’s musical Big River. His Eugene is kind and caring. He has a believable brotherly bond with Rescigno’s much more aggressively ambitious Stanley, and a truly warm rapport with Corey as his mother. The scene late in the play where Kate recounts her teenage adventure of running off to the Paradise Ballroom (when she should be sitting shiva) in order to dance with movie star George Raft requires Ingargiola to listen with love and wonder as he gains a deeper understanding of Kate as more than just his mother. That is not an easy trick to do. And when they dance – Eugene says later that he couldn’t hold his mother close because the moment was just too intimate – there is magic on the stage.

Which brings us to the delicate subject of casting. Corey is a fine actress and she gives a wonderful performance, but she is too young to play Kate. There is a time to play a role like Kate, and you need to live a while to earn that right. It took me about half an hour to be able to put this problem out of my mind and accept her as the 50-something matriarch. That I did accept her and was able to move past the age issue is a tribute to her talent and commitment to this role, but there are so many fine actresses of the right age – Oldcastle regular Christine Decker springs instantly to mind – for whom meaty roles like this are hard to find, that I still question director Eric Peterson’s choice.

Asprey, however, is perfectly cast. His portrayal of the genuinely tortured Jack is haunting and powerful. There are no laughs in this role. Jack is a man who sees his future clearly, and he hates it, but he knows it is inevitable. He will leave. He must leave. And he knows that it will hurt Kate and Stanley and Eugene, and him. That hurt will shape all of their future paths in life. The second act scene between Jack and his sons is frightening and heart-breaking as Asprey takes all of Jack’s self-loathing out on his sons, ruining their moment of triumph and leaving them reeling.

The role of Ben offers a little bit of the comic relief that Simon provides so easily through his older characters – most notably in The Sunshine Boys – but Ben is not an aging cantankerous comic. He is a man who has worked hard and done his best by his wife, his daughters, and his grandchildren and has come to a point where he is scared of what comes next. Moving to Florida is one step closer to…what comes after retirement? What comes after your 70s? Maybe your 80s, maybe not. Howe gives a solid performance offering real insights into a character who could just be a geriatric punch line.

Rescigno provides the real comic energy in the play. Stanley is well past the age when he wants to be living at home with Mom and Pop. He knows he has talent and ambition, but Simon makes it clear that even while he can’t wait to get to his future, he finds the prospect of change as daunting as the rest of the family. Rescigno carries the frenetic scenes where Eugene and Stanley struggle to come up with their audition sketch for their big break in radio.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

There is a sixth character, Kate’s sister, Ben’s other daughter, Blanche (Amy Gaither Hayes), whose second husband has surprised everyone by becoming quite rich and installing Blanche and her two daughters on Park Avenue. Blanche is the one who is ready and financially able to move her parents down to Florida, a climate that will be beneficial to her mother’s health, and Ben’s refusal to accept her “charity” and join his wife perplexes her.

Blanche and her daughters are key characters in Brighton Beach Memoirs, the first play in this trilogy, which is also set in Jack and Kate’s home, and I understand Simon’s interest in completing their story arcs, but unless you have a chance to see these two plays in close proximity, those aspects of her scene are awkward.

Set designer Carl Sprague has cleverly reworked his set for Oldcastle’s production of A Comedy of Tenors, which ran immediately before this production, and it works surprisingly well. There are well defined areas for the living room, the dining room, and Eugene and Stanley’s bedrooms upstairs. …Tenors is a six door farce which leaves the Jerome’s dealing with about two doors too many in their house, but Peterson, Sprague, and the actors make it work.

Ursula McCarty has crafted another fine set of costumes. Except for Blanche’s Park Avenue finery, the Jerome’s are not a stylish bunch, and her costumes clearly define the period and the socio-economic strata of the household.

Creating clearly audible sound that emanates from a radio and synchs with on stage dialogue is not easy and Cory Wheat’s sound design executes it well. My only problem with David V. Groupé’s lighting design was the jarring transitions when Eugene broke the fourth wall to act as narrator. Something much more subtle and less blinding would have been more effective.

I see a lot of plays – many of them very well written and many much more innovative in style and structure than Broadway Bound – but I have to say that it is a pleasure to attend the work of a playwright who just knows how to do it. Who knows how to create three-dimensional characters you care about, who knows how to structure scenes and advance plot, and who writes in clear, lucid language that flows. This is what is called a Well-Made Play, and with this fine cast it is just a joy to behold.

Broadway Bound by Neil Simon, directed by Eric Peterson, runs September 29 – October 15, 2017, at the Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, VT. Set design by Carl Sprague; lighting design by David V. Groupé; sound design by Cory Wheat; and costume design by Ursula McCarty. Stage Manager Gary Allan Poe. CAST: Sarah Corey as Kate, Richard Howe as Ben, Anthony J. Ingargiola as Eugene, Robbie Rescigno as Stanley, and Jason Asprey as Jack. Radio voices provided by Gary Allan Poe, Timothy Foley, and Jody June Schade. The show runs two and a half hours with one intermission. For tickets and more information visit http://oldcastletheatre.org/ or call 802-447-0564.

REVIEW: “Broadway Bound” at Oldcastle by Gail M. Burns From his perch in 1986, Neil Simon looked back to 1947 and wrote a play about the future.

#Amy Gaither Hayes#Anthony J. Ingargiola#Bennington VT#Broadway bound#Carl Sprague#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupe#Eric Peterson#Gary Allan Poe#Jason Asprey#Jody June Schade#Neil Simon#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Robbie Rescigno#Sarah Corey#Timothy Foley#Ursula McCarty

0 notes

Text

Mauritius is an island in the Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar. In 1847, when it was a British colony, the country issued two denominations of postage stamp – an orange one penny and a blue two pence – displaying the profile of a young Queen Victoria. Along the left hand side the words “Post Office” appear. These are the rarest and most valuable stamps in the world. In 2002 just the two pence stamp sold for £2 million. A pristine pair of them discovered in a deceased man’s stamp collection are coveted by all five characters in Theresa Rebeck’s 2005 play Mauritius, currently on the boards at Oldcastle.

The orange “One Penny Post Office” stamp.

The tiny speck that is Mauritius located in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar.

The blue “Two Pence Post Office” stamp.

This play was Rebeck’s Broadway debut and a Pulitzer Prize finalist and frankly, I expected more from it. Running just under two hours, you learn much more about philately (stamp collecting) than you do about the five characters in the play. Yeah, they all want the stamps, or, more properly, the money they can fetch. Who wouldn’t? You see enough of half-sisters Jackie (Meredith Meurs) and Mary (Doria Bramante), both of whom claim the stamp collection as their inheritance, to want to know much more about their backstory than you are given. There is also more to murky past between philatelist Philip (Richard Howe) and the shady character Sterling (Peter Langstaff) than Rebeck reveals. The fifth character, Dennis (Gabriel Vaughan), is an enigma while at the same time being the catalyst for the plot.

The Pulitzer nod and the fact that the actor playing Dennis on Broadway garnered a Tony nomination makes me suspect that this production isn’t firing on all cylinders, that there is something that director Eric Peterson or this cast aren’t getting, or aren’t giving the audience. Rebeck has written a purposefully oblique play, so someone has to fill in the blanks enough to make us care about these people.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Jackie and Mary shared a mother, who has just passed away, but not a father. Mary’s father died when she was young and Jackie’s father, we gather, was an abusive ne’er do well who has skipped the scene. Mary was old enough to escape the horror’s of their mother’s second marriage, Jackie wasn’t. Jackie blames Mary for abdicating her responsibility to their mother. The contested stamp collection belonged to Mary’s paternal grandfather with whom she shared a close relationship, hence her claim to ownership. Jackie feels that she has “earned” her inheritance by being there for their mother during her second marriage and her battle with the cancer that has finally claimed her life.

An Inverted Jenny.

Jackie takes the stamp album to Philip’s business, where he buys, sells, and appraises stamps. When he refuses to even open the album, Dennis, who is lurking in the shop, possibly on some business for Sterling, agrees to take a look, over Philip’s objections, and spies first a 1918 Inverted Jenny (see photo) and then the pair of stamps from Mauritius. He takes news of his discovery to Sterling and together they plot to acquire the stamps under the table, cutting out Philip and the IRS.

Then there is that murky connection between Philip and Sterling that seems to render them both mortal enemies and oddly beholden to one another…

I suspect that both Meurs and Vaughan are either miscast, badly directed, or both. Meurs was terribly stagey in her acting at the top of the performance I attended, and Vaughan is not smarmy enough by half. While Langstaff managed to convey real physical menace, Vaughan never convinced me of Dennis’ dark side, which, had it been conveyed would have added considerable depth to the production.

Rebeck has crafted an intriguing set of twists and turns to her plot, and each character takes turns being the villain of the piece, but the most heartless turn of all belongs to Bramante’s Mary. She is well cast, projecting both the WASP looks and veneer of bonhomie that render Mary truly despicable.

I have included clear photos of the contested stamps in this review because they are so clearly presented in Cory Wheat’s projections. The screen dominates the playing area and each stamp appears as it is discussed, which connects the audience more closely to the action. No one is credited with set design, but Ursula McCarty and Roy Hamlin are listed as the production designers. A series of three and two-dimensional rectangles and a pair of hung window frames are moved to define location. And everything is covered in stamps, even the bag of chips that Dennis offers to Jackie. Cleverly, the window frames are crenellated to mimic the perforated edges of most stamps.

There is also no credit for costume design, which may explain why, when the action takes place over the course of two days, only Dennis gets a change of clothing.

Ultimately, all these rather unpleasant people get what they want, with the exception of Sterling, whose revenge is inevitable, but that is another story for another play.

Mauritius by Theresa Rebeck, directed by Eric Peterson, runs July 21-August 6, 2017 at Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, VT. Production design by Ursula McCarty and Roy Hamlin; lighting design by David V. Groupé; projections/sound design by Cory Wheat; stage manager Gary Allan Poe. CAST: Meredith Meurs as Jackie, Richard Howe as Philip; Gabriel Vaughan as Dennis, Peter Langstaff as Sterling, and Doria Bramante as Mary. The show runs two hours with one intermission.

For reservations of further information contact Oldcastle Theatre by calling 802-4470564 or visit their website at: oldcastletheatre.org.

Mauritius is an island in the Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar. In 1847, when it was a British colony, the country issued two denominations of postage stamp - …

#Bennington VT#Doria Bramante#Eric Peterson#Gabriel Vaughan#Mauritius#Meredith Meurs#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Peter Langstaff#Richard Howe#Theresa Rebeck

0 notes

Text

by Gail M. Burns

Moonlight and Magnolias, currently on the boards at Oldcastle, centers on a story related in William MacAdams’ 1990 biography of Oscar-winning screenwriter Ben Hecht. A scene-setting quotation from MacAdams:

“At dawn on Sunday, February 20, 1939, David Selznick … and director Victor Fleming [who Selznick had pulled away from shooting The Wizard of Oz] shook Hecht awake to inform him he was on loan from MGM and must come with them immediately and go to work on Gone with the Wind (GWTW), which Selznick had begun shooting five weeks before. It was costing Selznick $50,000 each day the film was on hold waiting for a final screenplay rewrite and time was of the essence….Recalling the episode in a letter to screenwriter friend Gene Fowler, [Hecht] said he hadn’t read the novel but Selznick and director Fleming could not wait for him to read it. They would act out scenes based on Sidney Howard’s original script which needed to be rewritten in a hurry. Hecht wrote, ‘After each scene had been performed and discussed, I sat down at the typewriter and wrote it out. Selznick and Fleming, eager to continue with their acting, kept hurrying me. We worked in this fashion for seven days, putting in eighteen to twenty hours a day. Selznick refused to let us eat lunch, arguing that food would slow us up. He provided bananas and salted peanuts….thus on the seventh day I had completed, unscathed, the first nine reels of the Civil War epic.’”

You can see how this incident would intrigue a playwright. What was that week of bananas, peanuts, and an impromptu two-man version of a Civil War epic like? The fact that it could be true and that the British-born Hutchinson has obviously done his homework on the real lives of these three men make Moonlight and Magnolias both tantalizing and overwrought. But history has played a cruel trick since the play was written in 2004.

In February of 1939 Hitler was in power, World War II was imminent (the official start of the war is reckoned from September 1939), and both Selznick and Hecht were Jews. Hecht was a Zionist and a social activist, and he is rightly questioning where the American government would come down on the issue of American Jews. Would they be deported? Cinfined to ghettos? Interred in camps? Or more aggressively persecuted as was happening across Europe? A group of powerful people – including future presidents John F. Kennedy and Gerald Ford – were advocating for an isolationist policy under the slogan “America First.” There is a lot of talk in the play about who is a “real American.”

Do you understand why this play is a lot less funny than it was when I last saw it in 2009? It’s déjà vu all over again, as they say.

But even a decade or so ago I found Hutchinson’s choice to work in Hecht’s politics, and Selznick and Fleming’s terror of failing in a highly competitive industry, heavy handed and repetitive. While there are still laughs to be had, the script itself is what bogs down the humor.

At Oldcastle, director Eric Peterson has assembled a talented cast who sadly lack the physical agility to really break this farce open into madcap hilarity. The production I saw in 2009 featured a much younger cast with broader improvisational skills. This production may be much closer to what actually happened – Selznick was 37, Hecht 45, and Fleming 50 in 1939 – but this is not real life and the restraint negates many of the humorous possibilities. No attempt has been made to cast actors who actually look like Selznick, Hecht, and Fleming, which is fine because even the realest of “real Americans” don’t have a clear idea of what these behind the scenes fellows looked like.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

As the Wunderkind producer David O. Selznick, Eli Ganias shows the most comedic flare. His Scarlett O’Hara is thoroughly masculine while being innately feminine. It is Selznick’s dogged determination – to the point of insanity – that drives the action, and Ganias generates the energy to make the situation plausible (just because it really happened doesn’t make it any more believable.)

Paul Romero’s Ben Hecht is largely the play’s straight man, and he certainly bears the burden of Hutchinson’s most densely political diatribes. Be he does a wonderful job of becoming more and more believably overwrought as the scenes progress. Luckily in the 1930’s gentlemen wore quite a few layers of clothing – fedora, suit jacket, tie, button down shirt, undershirt, so Costume designer Ursula McCarty and her assistant Kristine Marcoux have the latitude to remove and dishevel the actors’ ensembles bit by bit to infer the passage of time and the men’s increasing distress. Romero’s hair makes a truly hilarious transformation over the course of the three scenes, from neatly slicked down to practically vertical on his scalp.

Nathan Stith is sadly miscast as Victor Fleming. He has none of the panache that a big time Hollywood director of the Golden Age would have projected. Part of the ethos of this character is watching his confident façade crumble, which is impossible since it was never there in the first place.

The trio does function very well as a team – notably in the scene where they debate, and demonstrate the various ways in which Scarlett can slap Prissy during the famous “I don’t know nothing about birthing no babies” scene. At times the actors are too flawless of a team since their characters are supposed to be antagonists locked in a room together until success, or failure, becomes their fate. They do succeed of course, and we all know that GWTW has gone on to be one of the great films of all time, although ironically Sidney Howard, not Ben Hecht got the credit for the screenplay, and, posthumously, the Oscar.

Rounding out the cast is Natalie Wilder as Selznick’s put upon secretary, Miss Poppenguhl. It is a ridiculously small and thankless role which inevitably wastes the talents of the actress who assays it. Wilder does very well with the little she is given by Hutchinson. I am glad she had the chance to play Dorothy Parker in a solo show at Oldcastle the other week.

Richard Howe has designed another glorious Oldcastle set. His vision of David O. Selznick’s office at Selznick International Pictures is an art deco masterpiece in salmon.

I am sorry that history has played such a mean trick and robbed Moonlight and Magnolias of much of its comic punch. This is still a strong and entertaining production, well worth seeing for historical interest as much as anything else in this day and age.

Moonlight and Magnolias by Ron Hutchinson, directed by Eric Peterson, runs June 23-July 9, 2017 at the Oldcastle Theatre Company, 331 Main Street in Bennington, Vermont. Scenic design by Richard Howe; lighting design by David V. Groupé; sound design by Cory Wheat; costume design by Ursula McCarty; costume assistant Kristine Marcoux; properties design by Christine Decker and Jennifer Marcoux; production stage manager Gary Allan Poe.CAST: Eli Ganias as David O. Selznick; Paul Romero as ben Hecht; Nathan Stith as Victor Fleming; and Natalie Wilder as Miss Poppengihl.

REVIEW: “Moonlight and Magnolias.” by Gail M. Burns Moonlight and Magnolias, currently on the boards at Oldcastle, centers on a story related in William MacAdams’ 1990 biography of Oscar-winning screenwriter Ben Hecht.

#Ben Hecht#Bennington VT#Christine Decker#Cory Wheat#David O. Selznick#David V. Groupe#Eli Ganias#Eric Peterson#Gail Burns#Gail M. Burns#Gary Allan Poe#Gone with the Wind#Jennifer Marcoux#Kristine Marcoux#Moonlight and Magnolias#Natalie Wilder#Nathan Stith#Oldcastle#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Paul Romero#Richard Howe#Ron Hutchinson#Ursula McCarty#Victor Fleming#William MacAdams

0 notes

Photo

Oldcastle Presents Pulitzer Prize-Winning “Proof” David Auburn's "Proof" which combines mystery, surprise and old-fashioned storytelling in a compelling evening of theatre that won both the Tony Award for Best Play and the Pulitzer Prize, opens Friday August 31st in the…

#Bennington VT#Cory Wheat#David Auburn#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Ethan Botwick#Halley Cinfarini#Oldcastle Theatre Company#OTC#Proof#Richard Howe#Talley Gale#Ursula McCarty#Wm. John Aupperlee

0 notes

Text

by Gail M. Burns

Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile, first published in serial form from 1854-1855, is Herman Melville’s only historical novel, based on the 1824 pamphlet The Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel R. Potter by Henry Trumbull which Melville had acquired in the 1840’s. Melville disliked his finished novel, and admitted he only wrote it because he needed the money. Today Melville scholars regard the novel as one of the least of the author’s lesser writings.

Israel R. Potter (1754–1826) led a dramatic but ultimately dismal life. He fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill, entered the colonial navy from whence he was taken prisoner of war by the British, and, upon his escape, became a secret agent and courier between colonial sympathizers in Britain and France. Along the way he had encounters with King George III and Benjamin Franklin. Ultimately he ended up living and working in extreme poverty in London, endlessly foiled in his earnest attempts to return home to New England.

Melville added a few fictional encounters for Potter – notably with Ethan Allen and John Paul Jones – and transferred his longed-for home from Rhode Island to the Berkshires, but there was really nothing he could do about the overarching bleakness of Potter’s story.

The central question here really is what would possess playwrights Joe Bravaco and Larry Rosler to think this would make a decent piece of theatre? It is Candide without the wit and Dickens without the entertaining characters. Unlike Dorothy Gale, that other stranger in a strange land who longs to go home, Israel Potter neither learns nor grows through his experiences, although it becomes soul-crushing obvious at the end that he has had his ruby slippers with him all along.

This is only the second professional production of The Almost True and Truly Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter , the first having been at a regional theatre in New Hampshire two years ago, where the director worked with the authors to make changes based on audience and actor feedback. I shudder to think what it was like in its earlier iteration.

I can see the appeal of this play, in theory, to Oldcastle Producing Artistic Director Eric Peterson and Nathan Stith, who has ably directed this production. Melville’s Berkshire home, Arrowhead, is an hour’s drive south of Bennington, and plays about the American revolution are in vogue because this is an important time politically to look back at the people and ideas that founded our nation. How can you resist staging a play in which Ethan Allen appears when your theatre is less than a block from the Ethan Allen Highway (Route 7)?

And how can you resist staging it when you have at your fingertips four of the finest actors to reside in this region, plus a talented newcomer and a company founder?

The waste of exceptional talent, both on stage and behind the scenes, is prodigious.

Josh Aaron McCabe is a whiz at playing multiple characters and is adept at comedy and drama alike, but here he is the one cast member who plays only one role, the title role of Israel Potter, and Potter is a stolid individual who expresses neither joy nor much sorrow, despite living the most luckless and depressing life possible. McCabe anchors the show with a solid performance, but he can do so much more.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I have never felt that Anne Undeland was miscast, and I have seen her in a variety of roles, until I saw her play Benjamin Franklin. I have no problem with gender-swapping, it is just that Undeland is NOT Ben Franklin. Thankfully she gets to shine in several other roles, including those of various women from the prim to the promiscuous.

A much more successful gender-swap is performed by Christine Decker, who at one point appears as “Mad” King George III. In fact, except for the sad affair of Dr. Franklin, Undeland, Decker, Richard Howe, Gary Allan Poe, and newcomer Robert St. Laurence do a bang-up job juggling roles and costumes and props and accents.

(Did you know John Paul Jones was Scottish? I didn’t, but he was and St. Laurence plays him with a BROAD Scots accent throughout. I was also unaware that Jones sailed under three flags – his native Britain, the United States, and then he finished his career as a Rear Admiral in the Russian Navy. Live and learn!)

This is a handsome looking show. Roy Hamlin’s multi-tiered set is evocative and inventive, and well supported by David V. Groupe’s lighting. Cory Wheat’s projections work seamlessly with the set, lights, and performers to create very clever illusions of place and movement. The costumes by Ursula McCarty follow on the tried and true basic-ensemble-enhanced-with-easily-swapped-additions-to-denote-character ploy, and they work well.

There are a few period songs, most sung a cappella, interpolated into the action. Sadly, most are truncated, and Stith has the ensemble continue singing softly under the ensuing dialogue which renders both the lyrics and the lines unintelligible. The cast present the songs well, and I would have enjoyed hearing at least a full verse of each, especially the original lyrics to the tune we now use for our national anthem. Francis Scott Key’s 1814 poem was set to the tune of a popular British song “To Anacreon in Heaven” which was popular on both sides of the Atlantic at the time of the American Revolution.

The problem here is the script, which isn’t even badly written, just turgidly dull and deeply depressing. Oldcastle has poured much talent and effort into this production. If only it had been in support of a show worth staging.

The Almost True and Truly Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter adapted by Joe Bravaco and Larry Rosler from a novel by Herman Melville, directed by Nathan Stith, runs June 15-24, 2018, at Oldcastle Theatre, 331 Main Street in Bennington, Vermont. Set design by Roy Hamlin, lighting design by David V. Groupe, sound and projection design by Cory Wheat, costume design by Ursula McCarty, stage manager Kristine Schlachter. CAST: Josh Aaron McCabe as Israel Potter. All supporting roles played by Christine Decker, Richard Howe, Gary Allan Poe, Robert St. Laurence, and Anne Undeland.

Tickets $12 for students with ID; $39 general admission; $50 premiere seating; $65 VIP seating. For additional information or reservations call 802-447-0564 or visit the theatre’s website: www.oldcastletheatre.org.

REVIEW: “The Almost True and Truly Remarkable Adventures of Israel Potter” at Oldcastle by Gail M. Burns Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile, first published in serial form from 1854-1855, is Herman Melville’s only historical novel, based on the 1824 pamphlet…

#Anne Undeland#Bennington VT#Christine Decker#Cory Wheat#David V. Groupé#Eric Peterson#Gail Burns#Gail M. Burns#Gary Allan Poe#Henry Trumbull#Herman Melville#Israel Potter#Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile#Israel R. Potter#Josh Aaron McCable#Kristine Schlachter#Nathan Stith#Oldcastle#Oldcastle THeatre#Oldcastle Theatre Company#Richard Howe#Richard St. Laurence#Roy Hamlin#The Almost True And Truly Remarkable Adventures Of Israel Potter#The Life and Remarkable Adventures of Israel R. Potter#Ursula McCarty

0 notes