#EWHA 2 1

Text

Korean Progress

This will be updated so I can see how I'm doing

2024-03-19 Bought online course (total of 12)

2024-04-06 Finished Course 1 the alphabet along with most pronunciation rules

2024-04-21 이화 한국어 Ewha Korean 1-2 (소개, Introductions)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Volume 2 Part 1

Week One

Okay…a LOT has happened this past week so this might be long. Tuesday was the first day of classes for everyone. Everyone has to take at least two classes and I’m taking Korean Traditional Painting and something called Visual Journal which I found out is an illustration drawing/creative class. I knew Alyssa and my friend Bianca (from STAMPS) were going to be in my painting class, but I knew no one else. Bianca had two friends with her (Zoe and Grace) and I kind of tagged along with them for lunch. Luckily Grace is in my Visual Journal class so we’ve stuck together since then and I can officially say I have a new friend.

Naengmyeon which are cold buckwheat noodles (that’s why there’s ice)

Anyways the takeaway from this week’s painting class is that my teacher is unorganized because the school is unorganized. There are probably about thirty or so students in my class, and my teacher was very surprised because she usually teaches classes with a max of twenty students. She was unprepared as apparently the school didn’t let her know of the class size.

We found out that Ewha is like UM and doesn’t help out with art school materials. While my teacher could’ve sent an email or message to us before the program, she waited till the first day to tell us we had to buy over 100,000 won (over $90) worth of materials. I don’t know if she saw the unimpressed looks of everyone, but she insisted we could take out/add whatever we wanted. The art shop we went to was in a different area and she assumed we all knew how to get there, but after some communication she said we would go the next day as a class. The art shop was very small and the materials did look pretty good. Unfortunately the man pre-packaged all of our stuff so we basically were forced to take what he put together.

Traditional brushes from art shop in Insa-dong

My friends and I were one of the first people to pay so the teacher told us we could stand outside and walk around while the others got situated. We were only gone just long enough for three people to get drinks, but when we returned to the shop, no one was there. So of course we were all freaking out, thinking they took the bus back without us, but we found out they went to an art gallery nearby. We spent some time there and after a while, the second group arrived. Basically a section of our class didn’t have money loaded on their T Money cards (cards used for public transportation and convenience stores) so one of the Korean speaking students took them to figure that out first.

Extra pics

Class is supposed to end at 11:30 so that we’d have an hour for lunch, but we were still there as the ending time approached. I don’t think our teacher was aware that we wanted to go back, but she eventually “dismissed” us and the first group including Grace and I left. Some upper class STAMPS kids were trying to be the leaders but led us the wrong way and then blamed the map, but we eventually managed to make it back to campus at 11:50. We weren’t very happy, but at least we made it in time. I later heard from Bianca that she and Zoe went to use the bathroom when everyone was there, but when they came out the first group was gone. They chose to take the subway thinking it’d be faster but apparently arrived at 1:15.

Gallery

My visual journal teacher is chill and speaks good English. She’s a children's book illustrator and said she used to work in San Francisco which was cool. 95% of the class is from STAMPS so it was kind of weird when we were all introducing ourselves. I like the class though.

Bottom floor of visual journal class building

Unlike UM though, Ewha has an underwhelming amount of tables/chairs to sit in. It’s become a challenge to find a spot during lunch as students literally sit on every step of the stairs just for a seat.

Here we are sitting on the ground like bums two lunch days in a row

Since Tuesday, I’ve hung out with Grace a lot and she’s just like me. We’re both nervous to use public transportation by ourselves and go into restaurants without English translations or kiosks. So we’ve gotten along pretty well and have gotten food with each other every day since.

We also both like going to the convenience store on campus even if it’s to just get a drink or ice cream. I’m pretty sure the guy that works there knows us by now.

Part of the ice cream collection (I tried my first Melona bar!)

Oh yeah and before I forget, I have a messed up fun fact. So the Ewha campus is a series of uphill and downhill walking which is extremely tiring in the hot temps. Even just the thought of the walk up the hill to the art buildings and then the 6 floors we have to walk up because of the nonexistent elevator makes me sigh. Anyways during our welcome tour, they told us that the reason why it’s such a journey all around is because Ewha is an all girls school. Back in the day when the school was made (over a hundred years ago), women pursuing an education were so looked down upon that they purposely didn’t flatten the land to try to make it harder for them to go to school. The school next to us, Yonsei University, was just like any other school which is why their land is completely flat.

Another fun fact totally unrelated to anything other than Korea is that there are absolutely no public trash cans on the street. I’m really sure why, but it’s kind of annoying because we have to hold onto our trash a lot of the time.

Moving on, I signed up for several Friday field trips. This past week was a Seoul city tour. We took a double decker tour bus around and stopped at a few notable sites.

The first stop was the Namsan Tower, also known as the Seoul Tower. Unfortunately it was a rainy cloudy day so we couldn’t see much of the land below.

It cost extra to get to the top of the tower, but it just wasn’t worth it with the weather. We did go into the tower plaza for a little bit though.

There were mostly refreshments for tourists. At the top there was a wide space with stores and traditional looking buildings.

Korea has a lot of life-size models of characters just standing around shops and stuff. Restaurants and cafes often have animal mascots and sometimes they just throw a statue outside to attract more people. I’ve noticed it around shopping areas too.

Penninah and I posing with Haechi, a Seoul mascot. Apparently he is some kind of mythical lion creature

The next stop was to Changgyeonggung Palace. I don’t know much about the history, but it was built back in the mid 15th century by the 4th ruler of the Joseon dynasty for his retiring father. It often served as residential quarters for queens and concubines. It was a pretty wide space with many buildings and pathways.

Front gate

By the end of this stop everyone was hot, sweaty, tired, thirsty, and most definitely hungry. We went back to where I had gotten my painting materials from for lunch and a break. Insa-dong has had quite a few people walking around both times I’ve gone there. The street shops were cool too and less focused on trendy items.

We all sort of went our own ways for lunch but Penninah and I joined a big group of people for food which made the process much easier.

Spicy beef jjigae (jjigae is a Korean stew and there are many variations)

Go to part 2 because I ran out of photo space for this post

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Papasan Choi died on Feb 23, 2023. Boonville was founded by him but taken away by Sun Myung Moon

Updated March 5, 2023

▲ Papasan Choi (aka Choi Sang-Ik, Choi Bong-Choon and Masaru Nishigawa) and Mamasan in Tokyo.

Sang-Ik Choi was born in 1925. At the age of two he had moved to Japan with his family, returning to Korea when they were forced to repatriate in 1945. His father gave him the name Bong-choon when he was in his twenties. He realized the significance of the name only after joining our church in April 1957 and thereafter adopted it. During his missionary days in Japan, he went by the Japanese name Masaru Nishigawa.

Mutual hostility contributed to Korea and Japan not restoring diplomatic relations until December 1965. In 1958, severe travel restrictions existed between the two countries. Talks recommenced in December that year only after Japan dropped its long-standing claim to about 80 percent of all property in Korea and its claim that Korea was the beneficiary from 1910-1945. Antiquities had been spirited away from Korea. Japan called this archeology; Korea called it theft. Any concessions on Japan’s part led to riots in Tokyo. Even in 1965, in both countries, riots and histrionic statements by politicians preceded the ratification votes.

He planted the seeds for the Unification Church in Japan from 1958 to 1964. Because Korea and Japan did not have diplomatic relations, he was arrested upon arrival in July 1958. Escaping confinement, he made his way to Tokyo where, after six months of struggle, he got a job as a salesman for a watch shop in the Shinjuku section. During the morning he worked. In the afternoon he witnessed. Once a week he rented the second floor of the shop to preach. On Sunday, October 2, 1959, he conducted the first Sunday service. The Unification Church of Japan commemorates this as its founding day.

Sang-Ik Choi was married in the 36 couples under the name of Bong-Choon Choi. His wife, Mi-Shik Shin, had been expelled from Ewha Woman’s University in 1955 during the UC sex scandal. The young women did not want to testify in court. However, Moon admitted to the judge that he had lied about his age to avoid the military draft. He was sentenced to two years in jail, but was released after a few months after some “special arrangements” were made. Papasan Choi was always reluctant to talk about how his wife was “womb-cleansed” by Sun Myung Moon.

▲ Papasan Choi with Japanese members

In 1964 he was deported from Japan to Korea; the following year he traveled to the US where he was known as Papasan Choi. He established a community in the Bay Area, but there was conflict between his group and that of Young-oon Kim who taught the Divine Principle in a more orthodox way.

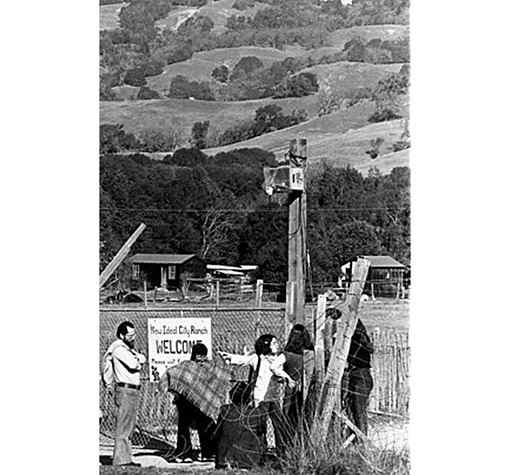

▲ Boonville, also known as New Ideal City Ranch

Boonville was purchased in 1970 by Papasan Choi. He and his wife, known as Mamasan, led the Re-Education Center which he had founded in San Francisco. Mamasan’s role in the community was significant. Yeon-Soo Lim (or Onni Durst as she was later known) ran an outpost of Papasan Choi’s community in Berkeley.

Papasan Choi’s secular teachings, The Principles of Education, were the foundation for the teaching methods used in the Bay Area and Boonville by Mose Durst, Kristina Morrison Seher and the Creative Community Project team.

__________________________________

▲ Papasan Choi, Mamasan and San Francisco members, January 1, 1969

“Furthermore, the International Re-Education Foundation had owned some land in Boonville, California, sometimes known as [the New] Ideal City Ranch, which it turned over in a simple transfer of title in 1974 to the Unification Church.” (page 111)

Rev. Sun Myung Moon (1978) by Chong-Sun Kim. University Press of America

In December 1974 Yeon-Soo Lim was married to Mose Durst by Sun Myung Moon in Pasadena. From then she was known as Onni Durst. At the same time Moon made her the Unification Church leader of California (excluding Los Angeles). In this way she inherited the Boonville property. Papasan Choi was sometimes described as a failure by leaders of the Creative Community Project, however, that had not been the case.

Link to an extended report on Papasan Choi and the early UC in California.

Papasan Choi made a public declaration about leaving the Unification Church on January 15, 1987 in Saitama, Japan.

統一教会問題と私、及びその未来 – 西川 勝氏

__________________________________

Creative Community Project brochure

From a talk given by Dr. Mose Durst, President of the Creative Community Project.

Childcare in the Unification Church of Oakland

Boonville – Is this how the Family cared for its children?

Recruitment – The Boonville Chicken Palace

by David Frank Taylor, M.A., July 1978, Sociology

Moonwebs by Josh Freed

Crazy for God: The nightmare of cult life by Christopher Edwards

Ford Greene – the former Moonie became an attorney

Chant 10,000 times – instruct Onni Durst and Kristina Morrison Seher, June 2014

__________________________________

Thomas W. Case:

Boonville in the spring of 1974

Inside Look at a Boonville Moonie Training Session

__________________________________

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Helen Kim (2016)

Helen Kim as New Woman and Collaborator: A Comprehensive Assessment of Korean Collaboration under Japanese Colonial Rule

by AhRan Ellie Bae

Introduction

In June 2013, the National Institute of Korean History insisted on removing a picture of Helen Kim’s statue from history textbooks.1 After the 708 pro-Japanese list was published in 2003, students requested that the actual statue at Ewha Womans University be removed from the campus.2 The students argued that it was shameful to have a statue of a traitor in-side the campus.

The issue of collaboration has been more widely researched and studied in Europe, especially regarding collaboration between occupied countries and Nazi rule during World War II. Novel attempts have been made to examine the issue of collaboration beyond nationalist historiography. For instance, in The Trial of Pierre Laval: Defining Treason, Collaboration and Patriotism in World War II France, J. Kenneth Brody considers Laval’s reasons behind his willingness to collaborate with Nazi rule. Nonetheless, according to Patrick Marsh, in the book titled Collaboration in France: Politics and Culture during the Nazi Occupation, “Despite an ever increasing amount of literature on the history of the Second World War in general and of Nazi rule in occupied Europe in particular, there is still no real agreement on the exact meaning of the term ‛collaboration.’”3

In the case of Asia, the issue of collaboration is ensnared with strong nationalistic sentiments, which makes it all the more complicated to pose difficult questions that would inevitably be criticized as being anti-nationalistic. In the case of Korea, several scholars have suggested colonial modernity as an approach to overcome the binary narrative of nationalist history.4 Nonetheless, the issue of collaboration is often inseparable from moral judgments, which proclaim these individuals to be guilty of treason even though they are no longer able to speak for or defend themselves. For instance, Pak Chihyang, in her comprehensive analysis of Yun Ch’iho’s diaries, argues that “his involvement in encouraging men to enlist into Japan’s imperial army went beyond betraying his own people—it should be treated as a crime against humanity.”5

Although there is still much debate about what collaboration is and how it should be defined, several definitions of collaboration could be useful in understanding Korean collaboration with the Japanese colonial government. Timothy Brook follows Henrik Dethlefsen in defining collaboration as “the continuing exercise of power under the pressure produced by the presence of an occupying power.”6 While this definition is useful, Brook points out that it is limited in that this definition is used to describe Denmark’s unique history, in which Denmark was allowed to keep and maintain its government under the Nazi occupation. In the case of Korea, Yumi Moon’s definition of collaboration as “political engagements of local actors to support a given colonial rule and to justify its sustenance in their society” is more applicable in that it reflects Korea’s subordinate position as a colonial subject. In this paper, this particular definition will be used to discuss various issues of collaboration.

Due to the recent accusations regarding ch’in’ilp’a (collaborator), the evaluations of Helen Kim’s works has become sharply divided between those who hail her as a pioneer of furthering women’s education in Chosŏn and those who vehemently criticize her for her alleged ch’in’ilp’a actions. Those who praise her argue that she was forced to collaborate with the Japanese; to protect Ewha, she had no other choice. Often, these arguments focus on Helen Kim’s many achievements such as her efforts to eradicate illiteracy to initiate rural enlightenment campaigns, and to build a “Korean” Ewha are just a few that are mentioned.7 However, these arguments are often based on her personal accounts written decades after the Japanese rule, which requires us to be cautious about their authenticity.8

Many criticize her for betraying her people or the Korean race (minjok) while using the excuse of furthering women’s rights. She is accused of succumbing to Japan’s demands, giving pro-Japanese speeches in villages, and encouraging women to volunteer as sex slaves for soldiers.9 These two clearly binary arguments are based on the sole assumption that what was right for the people equated fighting and even risking one’s safety for Chosŏn’s independence. This causes one to judge Helen Kim and many other prominent historical figures based on nationalistic moral standards, retrospectively.

Recently there have been more attempts to understand Helen Kim out-side of the pro-Japanese versus traitor framework. For example, in “Kim Hwalran’s (Helen Kim) Public Track and Her Pro-Japanese Collaboration During Colonial Korea under Imperial Japanese Reign,” Ye Jisook portrays Helen Kim as an indigenous intellectual who tried to elevate women and the overall status of Koreans by becoming part of Japan’s growing empire.10 Also, Kim Jihwa similarly asserts in her dissertation that Helen Kim did not suddenly betray Korea and became pro-Japanese; rather, she had to constantly maneuver between collaboration and negotiation with the Japanese as she devised ways to provide education for Korean women in a rapidly changing society.11 These research studies have provided new approaches to the existing paradigm regarding the issue of collaboration. Nonetheless, since these studies are largely limited to a few individuals and their writings, they fall short of providing a more comprehensive analysis of the issue of collaboration in the colonial context.

Specifically, these studies reinforce nationalist historiography’s tendency to minimize the importance of gender and how gender shaped one’s experience in the colonial era. It assumes that loyalty to the minjok should have been absolute, and ultimately, no other priorities could have been more important. This way of thinking hinders us from truly understanding the complex nature of women’s identity in the colonial era—specifically, how Korean women were uniquely situated as not only the “lesser” gender but also the colonial subject to be ruled. Korean women of the colonial era had to simultaneously deal with patriarchal oppression and imperialist exploitation.12

In this paper, I would like to focus on the following question: Should a divided loyalty and resultant collaboration automatically be treated as treason against the Korean people? As Brook states in his book, Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China, “Collaboration happened when individuals in real places were forced to deal with each other.”13 Helen Kim, as an educator and as a new woman, was also “forced to” deal with others and makes decisions without the hindsight of knowing where Korea would end up in decades to come.

Accusations

According to the Pro-Japanese Biographical Dictionary (Ch’in’il Inmyŏng Sajŏn) published on November 8, 2009 by Minjongmunjeyŏn’guso (The Center for Historical Truth and Justice), first and fore-most, Kim is accused of beautifying Japan’s “war of aggression” and promoting kouminkaseisaku (Japanization). She is criticized for giving “praise” for Japan’s war of aggression and urging people to participate in the war.14 Secondly, she is accused of using women’s rights movement to rationalize women and families’ involvement in the war. Also, She is accused of prioritizing women’s rights over the Korean minjok and thus, she committed treason against Korea.15 The nationalist historiography leaves no room for us to consider what could have motivated Helen Kim to collaborate with the Japanese. It completely ignores the complex nature of collaboration and women’s identity during the colonial era. Often, more than anyone would like to admit, resistance and collaboration could not be easily distinguished from each other.

Another minor accusation is that she was willing to collaborate with the Japanese in order to maintain Ewha.16 The imperial government began to have a tighter grip on the schools as the war progressed on and as part of the kouminkaseisaku, shrine visits became mandatory for schools. However, some schools such as Sungshil Secondary School refused to participate in these visits (as a Christian missionary school it believed shrine visits went against its beliefs), and as a consequence, the school was forced to close. Ewha was one of many, which agreed to participate in these shrine visits in order to keep the school open.

According to these accusations, there is no doubt that she collaborated with the Japanese. However, the focus of this paper is not about proving or disproving her involvement with the Japanese. Rather the purpose of this paper is to problematize the fixed notions we associate with the issue of collaboration by examining possible accountabilities for Helen Kim’s collaborative actions.

Her Identity as a New Woman and Her Calling as an Educator

Raised by a devout Christian mother, Helen Kim had a rare opportunity to receive an education, even though education was considered to be “useless” for girls in Chosŏn. She received most of her education through Ewha. Ewha, established in 1886 by Mary F. Scranton who was a Methodist Church missionary, was the first educational institutions for women established in Chosŏn in 1886. After graduating from Ewha, she was able to earn a master’s degree in philosophy at Boston University. Also, she was the first Korean woman to receive a doctorate, from Columbia University in 1931.

She possessed many unique qualities associated with “the new woman”—highly educated, economically independent—and was a pioneer of women’s rights movement in Korea. However, because of her strong Christian background, she was different from other mainstream female intellectuals, who were often accused of having a promiscuous lifestyle.17 She was rarely mentioned in scandals and rumors that pestered other female intellectuals, such as Pak Intŏk. She was an avid educator who believed that many of Chosŏn’s ills could be solved through long-term education programs and practical means to improve daily practices. For example, in her doctoral dissertation titled, “Rural Education for the Regeneration of Korea,” she suggests that cultural centers should be established in the villages to “keep up the growth of the villagers.”18 She goes on to also suggest that a training center should be established so that men and women would have the opportunity to prepare themselves for various vocations.

Accountabilities

First and foremost, it is crucial for us to free ourselves of the notion that doing what was patriotic for the minjok equaled fighting for Chosŏn’s independence. There is a possibility that people did not expect Chosŏn to become an independent nation in the near future, especially after the March 1st Movement’s failure to produce the desired outcome in 1919. Many so-called nationalists were forced to seek other possibilities as the movement disintegrated under pressure and harassment from the colonial government and growing dissonance amongst groups within the movement.

Although Helen Kim is heavily criticized for her activities in the late 1930s and early 1940s, her earlier writings also do not indicate her desire to promote Chosŏn’s independence. For Helen Kim, her emphasis constantly remained on women— from relentlessly pursuing education for women to giving practical advice on how to manage household chores. Although many researchers and scholars have argued that 1937 was the year that Helen Kim committed pyŏnjŏl, or betrayed Korea, in reality, many agendas that Helen Kim advocated in her writings in the 1930s and 40s can be traced back to her earlier writings. The idea that she betrayed the people to promote women’s rights overlooks how Chosŏn was a male-oriented society deeply rooted in Confucianism. Helen Kim and many other women intellectuals of this era were not fighting against the minjok; rather, they were tirelessly challenging the chauvinistic, male-centered Chosŏn society to give recognition to women as more than mere property that men could own. In an article titled “Rebuilding Korea & the Role of Women,” she argues that “when one sex’s responsibility and the importance of it is undermined, the whole machine becomes paralyzed.”19 She believed that Korea’s cultural development depended on the woman’s role in the family realm and that it was women’s responsibility to build an enthusiastic and culturally developed family.20 Therefore, the main concern was not about prioritizing women’s rights over Korean people; it was more about prioritizing the most marginalized and discriminated group of Koreans— women.

Women’s Rights versus Staying Loyal to the Minjok

On a determined quest to conquer the entire Asian continent, Japan did not remain satisfied after it forcefully established the puppet state of Manchukuo in Manchuria in 1931. Japan’s unquenchable thirst for a greater empire led to total war between Japan and China in 1937. With the war against China at a stalemate, accompanied by Japan’s ballooning ambition to “free” Asian colonies under European nations, its resources rapidly depleted. Consequently, it needed to mobilize all possible labor forces, including its colonial subjects. Japan was desperate enough to hand a gun to its colonial subjects to fight the war for Japan, and to do so, it had to devise ways to persuade Koreans into believing that what they were fighting for was worth dying for.

The colonial government’s policy on women experienced a transformation during this period. Korean women had strong emotional ties with their sons (which is not surprising since having a son determined a woman’s status and value in society), making it difficult for Japan to recruit soldiers to fight in the war. Many newspaper articles from this period mentioned worried mothers asking whether their sons would come home alive. Some mothers even wondered about the veracity of a myth, which said that if one thousand people were to sew one of their son’s clothes, he would be protected from bullets.21 To persuade these distraught mothers, as well as able-bodied young women, Japan had to offer an ideology that transcended traditional values and beliefs that Chosŏn put upon women. These women had to be persuaded to sacrifice what established their identity and legitimacy in the family—their sons. Along with a plethora of slogans, propaganda tactics, and policy changes, Japan accelerated the naisen ittai (Japan and Korea as One Body) process—with the sole purpose of creating submissive imperial subjects out of Koreans.

The process of nationalizing the role of women accelerated in Chosŏn, as Japan’s desire for more imperial loyal subjects increased with the ever-expanding war. Women, now imperial subjects, had the duty of biologically giving birth to more imperial subjects and educating and grooming these subjects to serve the nation in the future. Women’s private sphere, even their wombs, had a higher, more honorable purpose to bear fruit for naisen ittai.22 Therefore, raising imperial subjects well and transforming them into dedicated workers for the nation became the proud duty of mothers.23 Simultaneously, Japan cunningly politicized love, duty, and the family relations of women for the nation.24 This was accomplished by giving meaning and value to what women already did within the house-hold. The domestic realm itself became a battleground where women could participate as citizens of the growing empire. Making sure that they did not waste any resources and that they took care of their family’s needs were no longer trivial matters—they directly contributed to the empire’s survival. Women’s identity no longer remained within the boundary of family as a mother, a wife, a sister, and a daughter; women had a vital mission to support the “holy war.”

Scholars and many others who have accused Helen Kim of betraying the people, have argued that she “suddenly turned coat” in 1937, and her activities became treacherously “pro-Japanese.” The word used to describe Helen Kim’s actions after 1937, pyŏnjŏl, has the nuance of a complete change; one day, she was a patriotic social activist fighting for women’s rights, and the next day, she became a woman who sold her soul to pursue selfish goals. Although her activities did quietly alter after 1937, at the same time, much of what she did and said was a continuation from her earlier days as a female educator and activist. Therefore, we must ask whether many of the so-called ch’in’il activities and statements were truly new and out of Helen Kim’s character. For instance, was the process of nationalizing women’s identity within the domestic realm nonexistent before 1937? Was Helen Kim merely accepting, in a passive way, the colonial government’s effort to mobilize women for the war?

The idea that the woman’s role in the domestic realm is directly linked to participation in the society is evident in many of Helen Kim’s so-called pro-Japanese articles in the late 1930s and 1940s as well as in her earlier writings in the 1920s. Helen Kim and many other female leaders passionately asserted that women can play an important role for the nation. Although women were physically bound to the traditional boundary of the home, their identity transcended this through the nationalization process toward women’s identity. Home no longer was a private sphere—it be-came a public sphere where even women’s mundane chores became meaningful.

In 1931, Helen Kim wrote an article titled, “Rebuilding Korea & the Role of Women.” In the article, she passionately argues that it is the women’s duty to develop a “dynamic and cultural family” for Korea:

Secondly, most of Korea’s cultural development and continuation depends on the hands of the women. In order for Korea to greatly develop, despite the discrepancies we see, the families of Korea need to function as free entities. . . . They need to not only continue to develop the old, but also continue with conversation, family management, and educate the young adults.25

She avidly wrote that women mattered to Korea’s future development. For her, family was the smallest unit of a nation and keeping these entities healthy and dynamic was the utmost important factor for its further development. And in her perspective, family matters were no longer private matters, but public matters. In another article in which she discusses the issue of work and women, she asserts that the family is part of the society and taking care of the domestic realm equates to working in the society.26 She rebukes the so-called new women for having an attitude represented by the following statement: “Since we are stuck at home we might as well raise the kids and take care of the house!” She implores women to realize that “working” does not necessarily mean that all women have to get a job outside of their home; their primary responsibility and “work” is to develop and maintain the “home.” In fact, she argues that chores should actually be considered as work with tangible value.27

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise when Helen Kim declares that the economy of the kitchen is equal to the economy of the nation.28 Helen Kim declares that the “Women of the East” had their own “Eastern way” of taking care of the household. Phrases such as these reflect Helen Kim’s utilization of the Japanese war propaganda, which included slogans, such as “Asia for Asiatics,” to promote, shape, and form women’s identity in Chosŏn.

Many arguments Helen Kim uses in the so-called ch’in’il articles existed before 1937. This continuation reveals how naisen ittai was a two-way process, where the colonized also defined and shaped how it would un-ravel itself to its colonial subjects. Conceivably, the problem is not what she discussed— the problem is the purpose of what she discussed. The critics indicted her for “betraying” the Korean people. This betrayal is based on the assumption that she collaborated with “the enemy.” In the nationalist narrative, the occupying power, Japan, is pegged as the ultimate enemy or the villain to Koreans; therefore, collaboration becomes the ultimate “crime” against Koreans. This one-dimensional depiction of the occupying power, Japan, as the omnipotent enemy that all Koreans fought against, oversimplifies the complex relationship between Japan and Chosŏn. In particular, Korean women were doubly bound by the patriarchal system of Chosŏn as well as Japan’s imperialism. In other words, as much as Korean women were exposed to Japan’s oppression, they were exposed to the oppression of Korean men. Therefore, to understand the complex nature of one’s identity as the inferior gender and as the colonized subject, it is vital for us to explore how Korean women viewed and interacted with men in the colonial context.

Women versus Men

First of all, Helen Kim never argued for Korea’s immediate independence in any of her articles or statements before 1937. Her doctoral dissertation was solely focused on the topic of rural development within the limits of colonial authority. Even though she mentioned in her biography that she always longed for Chosŏn’s independence,29 unlike others who opted to go underground or be exiled to other countries to lobby for Korea’s independence, she did not choose to do so, and her work reflects this decision. She remained in Chosŏn to work for women whom she had the most compassion for. Her affection toward Korea’s nationhood was less palpable.

The national narrative of Korean history depicts Japan to be the only oppressor, aggressor, and usurper of Koreans. However, it should be noted that many resources related to women indicate something else. The traditional, male-dominated Chosŏn society continued to force women to be subjugated to the structural and systemic violence of the Chosŏn Dynasty well into the 1900s. Japan’s colonization of Korea did not change the status quo for women either. They were still considered the “lesser” gender, valued as property or tools to expand Japan’s empire. As a result, Korean women had to struggle against not only Korean men but also Japanese men as well.

The way new women began to view “old women” or the “old society” indicates the birth of the women’s rights movement in Korea. The advancement of modernization nurtured the first generation of Korean women who received modern education, and many of them began to become vocal about what they believed was debilitating Korean women—the patriarchal values of the Chosŏn Dynasty. The language, which de-scribed the position of women in the gender relationship, consisted of words such as slavery; women were born into the family as a slave, and they continued living as a slave obligated to perform traditional duties.30 Women were often described as victims of the society, bound by centuries-old traditions and values. What once was considered to be the norm began to be questioned and scrutinized. For instance, arranged marriage came to represent women’s lack of freedom and choice. Many articles in Shinyŏsŏng (New Women)31 consisted of girls who complained that they had nowhere else to go after finishing their education. They complained to the editor that the only expectations parents imposed on them were to marry and marry well. A girl from the countryside lamented how even if she went back home she would have nothing to do but be forced into a marriage arranged by her family.32 The world outside of the school boundary was plagued by a centuries-old social system, and unfortunately, modern education could not ensure a different future for many of these women. In this context, it is not surprising that many girls were lulled or manipulated into forced prostitution by an illusion of “career” opportunities offered by brokers.

What is interesting is that prominent magazines, such as Shinyŏsŏng, openly talked about women who became entangled in prostitution. Stories of women from poor families sold into slavery or prostitution were not uncommon in Chosŏn. Often when we deal with the issue of comfort women and comfort stations, we readily target the Japanese military only. Although Japan was heavily involved in the systematic recruitment and management of comfort women, we must also make sure that we do not turn a blind eye toward the fact that abuse of women was nothing new in Chosŏn. What is especially overlooked and must not be ignored is the fact that Korean men were also often involved and sometimes were the initiators of violence committed against Korean women. According to Sarah Soh, Koreans were involved as mediators and pimps to recruit Korean women into comfort stations.33 Similar to numerous women’s rights movements around the world, the few educated women of Chosŏn began to voice strong opinions about the existing violence against women in Chosŏn. They cried out that women were treated as men’s slaves; Korean women were forced to endure unspeakable amounts of abuse inflicted upon them by men.34 Because of these abuses, women “experienced many more obstacles” than men.35

Female novelists revealed the brutality of abuse through novels, which depicted women who were manipulated, exploited, and often violated psychologically and physically. In these novels, women seem to have almost close to no contact with Japanese men or women, while many Korean male characters molest, rape, and abuse Korean women for their own pleasure. For example, one of the most common cases mentioned throughout literature, magazines, and newspapers is a factory manager’s rampant assaults against female workers. Many factory managers took advantage of their position and molested women of various age groups. Often, managers (both Japanese and Korean) enticed and raped young girls, resulting in unwanted miscarriages, abortions, and stillbirths.36 Even at home, abuse against women was common and allowed; the abuse could range from cheating to sexual harassments and, at its worst, repeated rape. In the story Inganmunje (A Human Problem), the main character Sunbi is raped by her own stepfather. However, because she is too ashamed of what happened, she decides to leave home and go to work in a factory without confiding in anyone.37 This story illuminates the fact that even though women were victims, society forced them to take the responsibility for the consequences brought on by the abuser. Most women did not have the luxury of a choice regarding their future, except for the few who were successful (who are criticized as pro-Japanese). Furthermore, the general acceptance of abuse against women was certainly not unique to Chosŏn. As early as 1886, the Women’s Reform Society of Japan spoke out against the concubine system and prostitution, which were believed to be part of a bigger problem of sexual abuse against Japanese women in and out of the domestic sphere.38

Chosŏn society’s structural violence against women and its continuation during the colonial period were horrendous. As Soh pointed out, we cannot just point the blame at Japan for taking advantage of Korean women; Koreans also need to take responsibility for the perpetuation of a rigid patriarchal system that confined and debased women, denying women the right to choose how they wanted to live. The “biggest perpetrators here are the patriarchal societies of Japan and Korea.”39

In the nationalist context, women are again confined to a specific role that is accepted and promoted by men. A fitting illustration of this would be the ideology of “Good Wife, Wise Mother,” which developed in Japan and was later implemented in Chosŏn. For Japan, the meaning was given to women as mothers and wives who were in charge of the smallest unit of the national polity.40 The glorification of motherhood further developed as Japan avidly pushed forward its agenda to expand its empire. In other words, because of Japan’s pursuit of imperialism, the ideal of motherhood had to also expand to encompass the agenda of not only producing and raising the “sons of Japan” but also “asserting colonial hierarchy, and managing colonized subjects through assimilation.”41 This imperial motherhood is also reflected in the way Japanese women were expected to act toward colonial subjects. Since the colonial subject was thought to be underdeveloped (infant-like), slow, and in need of help to become a proper citizen of Imperial Japan, Japanese women were expected to take them under their motherly wings as well.

The short-story “Manchu Girl” by Koizumi Kikue illustrates a case of “the deployment of imperialist motherhood in the colonial context.”42 The story is about a young Chinese girl named Guiyu who was first hired as a servant for a Japanese couple. The Japanese woman, Koizumi, tries her hardest to embrace Guiyu and teach her the ways of the Japanese, from mastering the language to wearing kimonos. She represented the idealistic role of Japanese women in the colonial context—a parent figure to the colonial subject who surely needed “guidance” from Japan. Kimberly T. Kono noted that Koizumi’s status within the empire was dependent on how well she performed her role as an “imperialist mother.”

That is, her recognition as a national subject is contingent upon her successful performance of the officially sanctioned role of motherhood. Her status as a subject of Japan is not preexisting or inherent, but rather is produced through her interactions with Guiyu. Koizumi realized her own identity as a Japanese Citizen-subject by means of the very process of educating this girl.43

As one can see, the so-called “Good Wife, Wise Mother” was used to maneuver Japanese women to embrace motherhood and be responsible for taking care of imperial subjects, including colonial subjects. The nationalized motherhood was the only legitimate role women could engage in. Similarly, the colonial government’s intention was to utilize “Good Wife, Wise Mother” as a qualification to become an imperial woman.44 Chosŏn women were to embrace their role as the mother of Chosŏn by biologically reproducing sons and gladly sacrificing their sons for the empire. Korean women were in a more challenging position in that they were oppressed not only by the colonial power but also by Korean patriarchal values.

In addition, male nationalists who advocated education for women in the early 1900s began to shift their view on women’s rights by the 1920s; they believed that the new woman’s audacious challenge of patriarchy and sexuality could create a debacle for Korean tradition and unity.45 This is noteworthy since Korean men as colonial subjects did not have the right to vote, let alone Korean women. Korean women were still highly uneducated, restricted by their lower status in Korean society, and doubly bound not only by patriarchy but also by the colonial power. Therefore, more than their Japanese counterparts, these women had to learn to tread carefully between the colonial government’s demands and their hope to educate Korean women and improve their social condition in an environment where even fellow Koreans were unwilling to express their support.

However, once we closely examine the various articles written by female educators from 1937 to 1945, we can observe that some women’s views on “Good Wife, Wise Mother” were slightly different from their inland Japanese or Korean male intellectuals’ intentions. In Chosŏn, many women put more emphasis on urging women to be part of the holy war than on motherhood. These educators asserted that women were able to contribute and participate in the war effort as much as men. For example, Helen Kim would often compare women’s roles to that of men’s: “Although the pupils of Ewha should also take the glorious road towards the camp gate like (our) peninsula pupils will, the only reason why we cannot do so is because we are women.”46 Notice that women were “not allowed” to participate. In other words, she argued that women should not remain as mere spectators but as equally active participants of war, like men. She expresses this similar sentiment in another article published in 1939. She said, “I find it unfortunate that men are able to do many activities while women’s activities are delayed.”47

In this particular article, she goes on to criticize men and their lack of interest in women’s issues. She believed that men and women should work toward naisen ittai together.48 To new women like Helen Kim, naisen ittai policy became an opportunity to argue that women were qualified to provide service for the nation and that “men and women could collaborate, trust, and understand each other to solve problems.”49

As the war expanded, it became increasingly arduous for feminists to push for women’s rights agendas. Japan was becoming more and more militaristic, and like everything else, it demanded absolute loyalty from women toward Japan’s imperialist ambitions. Many Japanese feminists had to either completely surrender to Japan’s wishes or devise a way to promote women’s rights within the volatile social circumstances they were placed in. Some feminists decided to withdraw from the women’s rights movement altogether. Also, the Japanese government did not hesitate to censor socialist women through arrests and imprisonment, which made it more and more difficult for women’s rights activists to freely express themselves. Although organizations such as Women’s Suffrage League (WSL) continued the suffrage movement, with increasing surveillance and the imminent threat of an expanding war, they began to regard women’s suffrage as “unattainable in an ever more serious national emergency.”50 Instead, WSL strategically focused on community-based activism. However, suffragists had to comprise their position at times and co-operate and collaborate with other organizations that were under the government’s control.51

For Korean women, the act of supporting the war indeed reflected these women responding positively to Japan’s strategy to utilize the female population to continue the notorious war; however, these new women also attempted to navigate this opportunity to elevate the woman’s role in Chosŏn society; naisen ittai and “Good Wife, Wise Mother” were not limited to enforcing women’s biological duty to beget and raise imperial subjects. Many women, especially women educators, utilized these ideologies to challenge status of women in Chosŏn society. In addition to her lifelong calling to advocate women’s rights, Helen Kim also had another lifelong passion that she was committed to, which complicated the issue of the nature of her collaboration—Ewha.

Helen Kim’s Legacy, Ewha

Except for her stay in America to further her studies, Helen Kim’s childhood and her adulthood were spent entirely in Ewha. An American Methodist Missionary, Mary F. Scranton, established Ewha in 1886 with only a single student. After liberation, it became the first women’s university in Korea, and it is still known as one of the most prestigious women’s universities in Korea, showcasing prominent female scholars in various fields every year. Although Helen Kim could not afford an education, she was able to remain in school by receiving a full scholarship. As an adult, she worked as a teacher at Ewha for decades. She envisioned Ewha as fostering and equipping women to assume roles beyond another mouth to feed or another way to have economic gain since selling women into slavery and prostitution was a common practice in Chosŏn, especially in the countryside where families often struggled to make ends meet.

In her biography, she argues that she was forced to collaborate with the Japanese to protect Ewha from Japan. The reliability of her words is questionable, since there are no accounts to confirm the forced nature of collaboration. In addition, this biography was initially published in 1965, seventeen years after liberation, which causes us to wonder whether she used this book to excuse herself from all the ch’in’il accusations she received after the war. Although we can never be certain whether she was coerced into collaboration (if she was and to what extent), this biography provides a glimpse into the difficulties Ewha faced during the 1940s.

Ewha was the first women’s education institution built in Chosŏn, where girls were allowed to receive an education beyond their means. Helen Kim, as an alumnus and as a teacher and later as the first Korean female principle of Ewha, was intimately involved in Ewha’s growth during the colonial era. In her biography, she briefly mentions the reason she was never involved in Korean independence movements. She describes how many distinguished members of various independence movements asked her to join their cause, which seems probable since Helen Kim was one of the few women who was qualified enough to study abroad during the time when the United States served as a hub for Korean nationalists. Although these members persisted, she apparently declined the offer. In her biography, she says:

I believe what I have to do is different. I believe what you are doing is great and it has worth but everyone has a different role to play. I want to go back to Chosŏn. I want to work in Chosŏn. I believe what I can do is help people escape ignorance and teach them what I have learned.”52

The long-term financial support from foreign missionaries came to a halt due to the exacerbated relationship between Japan and the United States as the war continued to intensify after 1937. By 1942, all the missionaries were forced to return home. Although teachers and students began to abandon the schools out of fear or hesitation, Helen Kim did not consider closing the school an option. She states in her biography that, “even if she was the only to be left in school, she was willing to protect Ewha.”53 By April of 1944, the colonial government had taken control of Yeon Hee Professional School, (Yonsei) which is next to Ewha. However, Ewha remained under the management of Helen Kim.

Helen Kim is often criticized for collaborating with the Japanese rather than closing the school. According to the nationalists’ understanding of the colonial era, she should have closed the school to rebel against the colonial government’s growing pervasiveness. Once again, this accusation is simply based on the assumption that what constitutes a patriotic act equals being part of the Korean independence movement and waging guerilla wars against Japan. However, it precariously simplifies the relation between women’s identity and minchokchuŭi (ethnic nationalism). Most women were born into poverty, abuse, and discrimination. Even as a so-called elite woman, Helen Kim was often jeered by fellow male intellectuals, who believed that women should not have equal footing as men in all parts of society. Under this double bondage of patriarchy and imperialism, Helen Kim, a new woman of the colonial era, valued furthering education for women over being actively involved in the resistance movement.

Many of the pioneers in Korea’s modern education have been criticized as being pro-Japanese (thus a traitor). In fact, there was hardly anyone with status, influence, and responsibility who decided to not “betray” Chosŏn. Many principals of schools (especially in higher education) collaborated with the Japanese to some degree. The overwhelming presence of ch’in’il’pa in the education scene makes one wonder if it was even possible to resist collaborating with the Japanese at all.

War Propaganda and Involvement in Inscription

The more controversial allegation involves Helen Kim’s involvement in encouraging men and women to participate in Japan’s war efforts. Initially, the colonial government hesitated at the idea of enlisting Korean men in the Japanese army. They were suspicious of Koreans’ loyalty toward the army. However, with a growing demand for more soldiers, Japan did not have an alternative solution. In an effort to increase the number of enlisted soldiers, the Government General of Korea devised strategies to not only enforce enlistment but to also use propaganda to motivate the colonial subjects to participate in war efforts in every possible way.

However, the general resentment against her collaboration is most likely based upon a misunderstanding of the word chŏngshindae (women’s volunteer corps). It is very interesting that when you translate the world chŏngshindae into English in a Korean dictionary, the word comfort women is used.54 However, when you translate the Japanese word joshiteishintai into English, it is translated as “women’s volunteer corps” or “groups of young female workers organized on Japanese territory during WWII.”55 Many scholars have cautioned that the term chongshindae should not be used interchangeably with the term wianbu. This indicates that Koreans generally perceive comfort women to be identical to chongshindae even though the term chongshindae (which is a direct translation of the Japanese term teishintai) encompasses many different activities in the war efforts of imperial Japan. Sarah Soh addresses this discrepancy in her work The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan.56 Most comfort women were recruited through a middleman, who often deceived women by offering a job and a place to stay. Chŏngshindae, however, were part of Japan’s official effort to recruit female laborers to support the ongoing war. The purpose of recruiting chŏngshindae was entirely different from that of the comfort women. Chongshindae were recruited through official announcements, unlike the women who had to “comfort” the soldiers; many of these women were often alone and were tricked or bribed into forced prostitution.57 However, the term chongshindae has been used interchangeably with the term wianbu in South Korea’s nationalist historiography, which has resulted in a perversion and oversimplification of a variety of female wartime activities. This gives us the impression that most Korean women were officially recruited and forced into sexual slavery as comfort women. This gross oversimplification hinders us from understanding the lives of Chosŏn women and their interactions with society during this time, silencing the complexity of the identities that women had to embrace.

When we separate chongshindae from wianbu, we are finally able to consider the issue of collaboration. Many women’s rights activists and educators indeed encouraged women to participate in war efforts in various ways, from being frugal with household items to willingly sending off their sons to the battlefield. First of all, there is a need to further research whether these propaganda activities instigated Koreans to participate in the war. Secondly, considering (as addressed before) that Japan was the official authority in Korean society and considering that overseas independence movements had failed continuously, what other viable options did Koreans have? Could Japan winning the war and Koreans stepping up to be the “leader” of Asia seem more plausible than fighting for independence? If so, could we give a verdict of treason? What makes this issue more challenging is that, by only naming few collaborators, the nationalist historiography has ostracized the issue of collaboration into a unique phenomenon. For example, we are quick to condemn these women for collaborating with the Japanese to pursue women’s rights, whilst over-looking many Koreans, male Koreans, such as the myŏngjang (head of the township), who visited and persuaded poor families to send their daughters to work in Japan (one wonders whether many people actually knew the fate waiting for these women). In many cases, “Koreans actually out-numbered civilian Japanese among those seeking profit by human trafficking, forcing prostitution and sexual slavery upon young female compatriots.”58

From 1937 to 1945, people in Chosŏn were confronted with conflicts they did not volunteer for. For the elites, many were burdened with different opinions of what would be best for Chosŏn. For some, this involved collaborating with the Japanese in various degrees. This does not negate the fact that Japan’s colonial subjects, including Koreans and many others conquered throughout the war, had to experience the brutality and the barbarity of the war. Many women in these territories were forced or manipulated into becoming comfort women for Japanese soldiers. Many families in the colonies witnessed their sons being torn away from them, forced to risk their lives to serve Japan’s frantic attempt to continue the war. Many were coerced into forced labor in foreign lands, and many never had the opportunity to return home. As the war raged on, life in Chosŏn, and the entire Japanese empire, became harsher and harsher.

The nationalist historiography gives us no room to wonder about the difficulties for an individual trying to navigate and survive in this sort of volatile society. However, considering the small number of people who were actually involved in resistance activities, we have to assume that the general population was destined to struggle in the gray areas, where what they were fighting against and for often became murky and obscured.

Helen Kim’s multiple-layered identities as a new woman, educator, and a collaborator help us see how the issue of collaboration can be dauntingly complex. Looking into Helen Kim’s life helps observers see that her life was not dictated by a simple equation of betraying her people to advance women’s rights. As a colonial subject, who was labeled as being of an inferior gender, Helen Kim and many other women were doubly bounded by imperialism and the patriarchal traditions of Chosŏn society. Nationalist historiography has a tendency to overlook this aspect, and by doing so, it (subconsciously) conspires with imperialism to exclude or oppress women. Not only that, it partakes in concealing the systematic abuse against women.59 Ultimately, Helen Kim chose education as a tool to battle oppressive traditions and customs of patriarchy, where both Japanese men and Korean men were co-oppressors.

When we retrospectively impose the idea that loyalty to one’s ethnic group should be prioritized above all else, we are no longer capable of seeing the complex nature of collaboration, especially in the colonial context. For her and many others, collaboration with the Japanese remained in the gray areas, where the line between collaboration and resistance became blurred, and her loyalties and priorities shifted with time.

Certainly, we have witnessed the limitations of nationalist historiography to explore the issue of collaboration. Furthermore, we perhaps need to also take into consideration the development of Chosŏn under Japanese rule to fully understand why many Koreans chose to collaborate with the so-called enemy over the thirty-five year period.

International Journal of Korean History: https://ijkh.khistory.org/journal/view.php?number=475

Notes

* A condensed version of this article was presented at the Association for Asian Studies Annual Conference in Chicago, IL on March 27, 2015.

1 Jihoon Kim, “Kyogwasŏ ‘ch’in’il’ kimhwallan tongsang sajini idae p’yŏmha?,” Han’gyŏrye, June 1, 2013, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/schooling/590024.html.

2 This list was formulated by Minjokchŏnggirŭl seunŭn Kukhoeŭiwŏnmoim, established by several members from the National Assembly.

3 Gerhard Hirschfeld and Patrick Marsh, eds., Collaboration in France: Politics and Culture during the Nazi Occupation, 1940–1944 (Oxford: Berg, 1989), 3.

4 Michael Robinson, Cultural Nationalism in Colonial Korea (Seattle, WA: Univ. of Washington Press, 2014), 48–77, describes intellectuals who experienced colonial modernity head on as cultural nationalists. These intellectuals believed that enlightenment and personal development had to precede political independence. Also see, Gi-Wook Shin and Michael Robinson, eds., Colonial Modernity in Korea (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 1999) for further discussion on colonial modernity in the Korean context.

5 Jihang Park (Chihyang Pak), Yunch’ihoŭi Hyŏmnyŏgilgi: ŏnŭ Ch’in’il Chisiginŭi Tokpaek (Yun Ch’iho’s Collaboration Diaries) (Seoul: Esoope, 2008), 212.

6 Timothy Brook, Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 2.

7 Sung-Eun Kim, “Ilchesigi Kimhwallanŭi Yŏgwŏnŭisikkwa Yŏsŏnggyoyungnon,” (Helen Kim’s Thought of Women’s Right and Korean Women’s Education) Yŏksa wa Gyŏnggye (History and the Boundaries) 79 (2011): 184.

8 Jisook Ye, “Ilcheha Kimhwallanŭi Hwaltonggwa Taeil Hyŏmnŏk,”(Kim Hwal Ran’s Public Track and Her Pro-Japanese Collaboration during Colonial Korea under Imperial Japanese Reign) Han’guksaron 51 (2005): 398.

9 Yoko Okuyama, “Helen Kim’s Life and Thought under the Japanese Colonialism 1918–1945” (MA diss., Yonsei University, 1989), 45–46.

10 Jisook Ye, “Kim Hwal Ran’s Public Track,” 398.

11 Jihwa Kim, “Kimhwallan’gwa pagindŏkŭl chŭngsimŭro pon Ilche sidae Kidokkyo yŏsŏng Chisiginŭi ‘Ch’in’ilchŏk’ maengnak yŏn’gu” (A Study on the Context of ‘Pro-Japanese’ activities by Christian Intellectual Women under the Japanese Colonial Rule Focused on Helen Kim & Induk Pahk) (PhD diss., Ewha Womans University, 2005), 115.

12 For further discussions on this concept of this “double bind” Korean women experienced, see Pyeongjeon Lee, “Shinnyŏsŏngŭi shingmin ch’ehŏmgwa chajŏnjŏk sosŏl yŏn’gu,”(A Study on Modern Women’s Colonial Experience and Autobiographical Novel’s) Han’gugŏmunhakyŏn’gu (The Research on Korean Language and Literature) 43 (2004): 225–252. See also Insook Kwon, “The New Women’s Movement’ in 1920s Korea: Rethinking the Relationship between Imperialism and Women,” Gender & History 10–3 (November 1998): 381–405.

13 Brook, Collaboration: Japanese Agents, 26.

14 Kyŏngro Yun et al., Ch’in’il inmyŏng sachŏn (Pro-Japanese Biographical Dictionary) (Seoul: Minjok munje yŏn’guso, 2009), 709–714.

15 Yun et al., Ch’in’il inmyŏng sachŏn, 709–714.

16 Yun et al., Ch’in’il inmyŏng sachŏn, 709–714.

17 Christianity played an important role, in that many women were able to gain access to education through schools established by missionaries. It is well known that conflicts intensified between Korean intellectuals and missionaries over time. Thus, even though missionaries were considered pioneers of women’s education in Korea, at the same time, they were seen as imposing Western values on Koreans. For further discussion on Christianity and its influence on Christian female intellectuals, see Jihwa Kim, “Kimhwallan’gwa pagindŏkŭl chŭngsimŭro pon Ilche sidae Kidokkyo yŏsŏng Chisiginŭi ‘Ch’in’ilchŏk’ maengnak yŏn’gu,” 26–69.

18 Helen Kim, “Rural Education for the Regeneration of Korea,” in Uwŏlmunjip, ed. Kim Okkil et al. (Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press, 1979), 132.

19 Helen Kim, “Rebuilding Korea and the Role of Women,” The Korea Mission Field, March, 1931, 87–88.

20 Kim, “Rebuilding Korea and the Role of Women,” 87–88.

21 Jisook Ye, “Kim Hwal Ran’s Public Track,” 446.

22 Kurashige Shuuzou, “Chiwŏnbyŏng moja e parhanŭn sŏ: kukkayunghŭngŭi mot’aenŭn puinŭi hime chae,” Samch’ŏlli 23 (1940): 26.

23 Oono Teruko, “Chiwŏnbyŏng moja e parhanŭn sŏ: pandobuine kungminŭn kamsa,” Samch’ŏlli 23 (1940): 30.

24 Sheila Miyoshi Jager, “Woman and the Promise of Modernity: Signs of Love for the Nation in Korea,” New Literary History 29–1 (Winter 1998): 121–34.

25 Helen Kim, “Rebuilding Korea and the Role of Women,” The Korea Mission Field, March, 1931, 87–88.

26 Helen Kim “Chigŏpchŏnsŏn’gwa chosŏnnyŏsŏng,” Shindonga, September, 1932.

27 Kim “Chigŏpchŏnsŏn’gwa chosŏnnyŏsŏng.”

28 Helen Kim, “Puŏk’kyŏngjega kukkagyŏngje,” Maeilshinbo, July 6, 1938.

29 Helen Kim, Kŭ pitsogŭi ch’agŭn saengmyŏng (Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press, 1999), 163.

30 Many articles from the popular magazine Shinyŏsŏng (新女性) mention how women are merely treated like slaves within the domestic realm.

31 Shinyŏsŏng was the first women’s magazine published in Chosŏn by Kaebyŏksa. It discussed a wide range of topics that concerned women, including education, housework, child-reading, dating, marriage, and marital problems.

32 S. WH, “Sijimman karanŭn pumo,” Shinyŏsŏng 1 (1923): 131.

33 Chunghee Sarah Soh, The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2008), 138.

34 SJ, “Puinuntongŭi choryu,” Shinyŏsŏng 2 (1923): 433.

35 Yŏn’gusaeng, “Puinŭi chijŏk nŭngnyŏk,” Shinyŏsŏng 2 (1923): 533.

36 Theodore Jun Yoo, The Politics of Gender in Colonial Korea: Education, Labor, and Health, 1910–1945 (Berkeley: University of California, 2008), 136.

37 Gyŏngae Kang, In’ganmunje (Seoul: Dream Sodam, 2001). This story was originally published in the newspaper Tongailbo from September 1934 to December 1934.

38 Sharon L. Sievers, Flowers in Salt: The Beginnings of Feminist Consciousness in Modern Japan (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983), 93.

39 Chizuko Ueno, Nationalism and Gender, trans. Beverley Yamamoto (Melbourne: Trans Pacific, 2004), 128.

40 Chin Chŏngwŏn, Higashiasia no ryousaikenboron: tsukurareta dentou (Tokyo: Keisoshobo, 2006), 32.

41 David C. Earhart, Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2008), 226–227.

42 Michele Mason and Helen J. S. Lee, Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), 227.

43 Mason and Lee, Reading Colonial Japan, 234.

44 Kazue Inoue, Shokuminchi chosŏn no shinjosei (Tokyo: Akashishoten, 2013), 37.

45 Kwon, “‛The New Women’s Movement’,” 381.

46 Helen Kim, “Chingbyŏngjewa pandoyŏsŏngŭi kago,” Shinshidae, December, 1942.

47 Helen Kim, “Puindŭlkkiriŭi aejŏnggwa ihae,” Tongyangjigwang, June 2, 1939, 221.

48 Kim, “Puindŭlkkiriŭi aejŏnggwa ihae.”

49 Ko Myŏngcha, “Atarashii fujin no michi,” Tongyangjigwang June 2, 1939, 223.

50 Taeko Shibahara, Japanese Women and the Transnational Feminist Movement before World War II (Tokyo: Temple University Press, 2014), 110.

51 Shibahara, Japanese Women, 110.

52 Helen Kim, Kŭ pitsogŭi ch’agŭn saengmyŏng (Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press, 1999), 108.

53 Kim, Kŭ pitsogŭi ch’agŭn saengmyŏng, 108.

54 “Naver English Dictionary,” accessed December 24, 2015, http://endic.naver.com/search.nhn?sLn=kr&isOnlyViewEE=N&query=정신대.

55 “Weblio English-Japanese Dictionary,” accessed December 24, 2015, http://ejje.weblio.jp/content/%E5%A5%B3%E5%AD%90%E6%8C%BA%E8%BA%AB%E9%9A%8.

56 Chunghee Sarah Soh, The Comfort Women, 57.

57 Yuha Park, Chegugŭi Wianbu (Comport Women of the Empire) (Seoul: Ppuriwa Ip’ari, 2015), 47.

58 Chunghee Sarah Soh, The Comfort Women, 140.

59 Hyŏkpŏm Kwŏn, Minjokchuŭi nŭn choeag in’ga (Nationalism is a Crime?) (Seoul: Arop’a, 2014), 150.

Go to : Goto

References

1. Brody, J Kenneth. The Trial of Pierre Laval: Defining Treason, Collaboration and Patriotism in World War II France New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2010.

2. Brook, Timothy. Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

3. Chin, Chŏngwŏn. Higashiasia no ryousaikenboron: tsukurareta dentou Tokyo: Keisoshobo, 2006.

4. Earhart, David C. Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2008.

5. Hirschfeld, Gerhard and Marsh Patrick. Collaboration in France: Politics and Culture during the Nazi Occupation, 1940–1944 Oxford: Berg, 1989.

6. Inoue, Kazue. Shokuminchi chosŏn no shinjosei Tokyo: Akashishoten, 2013.

7. Jager, Sheila Miyoshi. "Woman and the Promise of Modernity: Signs of Love for the Nation in Korea New Literary History 29(1):Winter;1998).

crossref

8. Kim, Jihwa. Kimhwallan’gwa pagindŏkŭl chŭngsimŭro pon Ilche sidae Kidokkyo yŏsŏng Chisiginŭi ‘Ch’in’ilchŏk’ maengnak yŏn’gu. A Study on the Context of ‘Pro-Japanese’ activities by Christian Intellectual Women under the Japanese Colonial Rule Focused on Helen Kim & Induk PahkPhD diss Ewha Womans University, 2005.

9. Kim, Sung-Eun. "Ilchesigi Kimhwallanŭi Yŏgwŏnŭisikkwa Yŏsŏnggyoyungnon (Helen Kim’s Thought of Women’s Right and Korean Women’s Education)." Yŏksa wa Gyŏnggye History and the Boundaries79 2011).

10. Kwŏn, Hyŏkpŏm. Minjokchuŭi nŭn choeag in’ga (Nationalism is a Crime?). Seoul: Arop’a, 2014.

11. Kwon, Insook. "‘The New Women’s Movement’ in 1920s Korea: Rethinking the Relationship between Imperialism and Women Gender & History 10(3):(November 1998).

crossref

12. Lee, Pyeongjeon. "Shinnyŏsŏngŭi shingmin ch’ehŏmgwa chajŏnjŏk sosŏl yŏn’gu (A Study on Modern Women’s Colonial Experience and Autobiographical Novel’s)." Han’gugŏmunhakyŏn’gu The Research on Korean Language and Literature43 2004).

13. Mason, Michele and Lee Helen JS. Reading Colonial Japan: Text, Context, and Critique Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2012.

14. Okuyama, Yoko. Helen Kim’s Life and Thought under the Japanese Colonialism 1918–1945. MA diss Yonsei University, 1989.

15. Park, Jihang. Yunch’ihoŭi Hyŏmnyŏgilgi: ŏnŭ Ch’in’il Chisiginŭi Tokpaek (Yun Ch’iho’s Collaboration Diaries). Seoul: Esoope, 2008.

16. Park, Yuha. Chegugŭi Wianbu (Comport Women of the Empire). Seoul: Ppuriwa Ip’ari, 2015.

17. Robinson, Michael. Cultural Nationalism in Colonial Korea Seattle: Univ of Washington Press, 2014.

18. ShinGi-Wook. RobinsonMichael. , eds. Colonial Modernity in Korea Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 1999.

19. Sievers, Sharon L. Flowers in Salt: The Beginnings of Feminist Consciousness in Modern Japan Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983.

20. Shibahara, Taeko. Japanese Women and the Transnational Feminist Movement before World War II Tokyo: Temple University Press, 2014.

21. Soh, Chunghee Sarah. The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan Chicago: University of Chicago, 2008.

22. Ueno, Chizuko. Nationalism and Gender Yamamoto Beverley . Melbourne: Trans Pacific, 2004.

23. Ye, Jisook. "Ilcheha Kimhwallanŭi Hwaltonggwa Taeil Hyŏmnŏk (Kim Hwal Ran’s Public Track and Her Pro-Japanese Collaboration during Colonial Korea under Imperial Japanese Reign)." Han’guksaron 51 2005).

24. Yoo, Theodore Jun. The Politics of Gender in Colonial Korea: Education, Labor, and Health, 1910–1945 Berkeley: University of California, 2008.

25. Yun, Kyŏngro and et al. Ch’in’il inmyŏng sachŏn (Pro-Japanese Biographical Dictionary). Seoul: Minjok munje yŏn’guso, 2009.

#korean history#japanese history#japan#korea#republic of korea#helen kim#south korea#imperialism#japanese imperialism#colonialism#japanese collaborator#history#counterinsurgency#anti-communism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bigbang debut

Bigbang debut Offline#

Bigbang debut series#

“Replay” became released on Could 22, 2018, and became incorporated in the debut extended play of the the same title.

Bigbang debut series#

It precipitated their recognition to skyrocket, earning them an infinite series of rookie awards at yr-cease award exhibits. The song became a #1 hit and became a colossal success for the community. “By no map All all over again” became released on June 8, 2005, and became incorporated in the neighborhood’s first extended play, “Kyeonggo”. It has been lined by an infinite series of groups, resembling GFRIEND, I.O.I, TWICE, and Red Velvet.ģ. It all over all all over again saw a resurgence in 2016 when college students from Ewha Girls’s College sang it at some level of a gathered college. In 2010, it saw a resurgence, peaking at number 2. At some level of its release, it debuted at number 5 on the Tune Trade Association of Kora chart. “Into The Unique World” became released on August 3, 2007, as the community’s debut single. Girls’ Generation – “Into The Unique World” The song topped the K-pop charts for eight consecutive wins, while the album became the sixth simplest-promoting album of the yr.Ĥ. “Lovesick” became released on June 5, 2007, and became incorporated in the neighborhood’s first studio album “Gay Sensibility”. It be identified for rhythmic up-tempo tune and raps. The song became tranquil by member G-Dragon and the lyrics had been written by him and T.O.P. “WE BELONG TOGETHER” became released on August 28, 2006, and became incorporated in BIGBANG’s debut self-titled single album. The song became the kind of hit that American journalist Perez Hilton even shared it on his blog.

Bigbang debut Offline#

The song became a colossal hit in all Korean song charts, topping all on and offline charts in the country. “FIRE” became released on Could 6, 2009, as 2NE1’s debut single. The song peaked at number 14 on the Billboard World Digital Tune Gross sales Chart. “Trespass” became released on Could 14, 2015, and became the lead discover from MONSTA X’s debut extended play. The song entered the Billboard World Digital Songs chart at number 14 on June 29, 2013. The song became released on June 12, 2013, earlier than BTS’s debut showcase. “No More Dream” is thought of as one of the dear 2 singles that became promoted from BTS’s debut single album “2 Frigid 4 Skool”. The song became promotedly largely in the united states and South Korea. The song became released on October 4, 2019, and became incorporated in the neighborhood’s self-titled debut extended play. “Jopping” is the debut single of South Korean boy community SuperM, below SM Leisure.

0 notes

Text

practice practice practice!

어제 저는 장을 봤어요. 저 보통 French vanilla 커피를 사지만 가게에 그 커피가 없었서 새로운 커피를 샀어요. 오늘 그 커피를 마셔 봤요. 그것을 좋아해요? 몰라요. 그 커피가 아주 달콤해요!

You know, I realize I don’t.... actually know how to talk about grocery shopping? I know it was shown in integrated 1 but I SWEAR I don’t remember it actually being used in a manner that I could learn from, so uh. An attempt was made. It’s probably wrong but the point is that I tried! Much like I tried this new coffee - I expected it would be sweet cos, okay, come on it’s Starbucks caramel lmao but holy crap by the last dregs of my second mug my tum was feeling some Things and not good things, either.

Anyway I haven’t studied as much as I meant to, partly cos I just didn’t have access to my workspace as long, partly cos I had a tummy ache from the coffee, but mostly cos I just need to be more diligent. I did, however, go over some stuff in how to study korean again and some book practices, so that’s good. The book is going over ~았/었을 때 now which is obviously an easy follow up to ~(으)ㄹ 때 but more importantly it’s talking about 그때는 기분이 어땠어요? which is REALLY exciting because tbh as far as feelings go, I don’t know a lot! I might even type those up later to try to further reiterate them in my mind, though I suppose obviously the better option will to be write about them specifically, but I may save that for tomorrow when my head feels more awake and alert than it does now.

I feel like this grammar piece is, for me, like so many others are. I understand it but I never think to use it and I definitely wanna drill more uses into my head, because I do in fact talk about “The times when” so! Get to it, Ashlie! (I miss skyping with Kristal and her forcing me to do things against my will :( )

For some reason I’ve been in a drama rewatching mood which is V RARE I almost never rewatch anything (cos there’s so many other things to watch and so many other ways to waste my time) but I decided to rewatch Oh My Ghost because I guess I like crying (and okay I’m pretty much in love with half the cast lmao) and try to use a lot of that time to work on my auditory Korean. Still TERRIBLE but you know. I’m trying, I try real hard not to be a brainless watcher lmao.

I’ll go finish up those lessons and see what follows and maybe see if I can’t put together some sentences (and let Kristal look over this and see how we can fix that above piece cos yoinks)practice

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unique Starbucks Branches In Seoul

1. Starbucks Reserve Ewha Women’s University

2. Starbucks Reserve Jongno Tower

3. Starbucks Reserve Famille Park

4. Starbucks Reserve Hwangudan

5. Starbuck Seoul Wave Art Center

6. Starbucks Cheongdam Dong

7. Starbucks Byeoldabang

#starbucks#starbucks reserve#starbucks branches#seoul cafe#seoul aesthetic#seoul south korea#seoul guide#seoul headers#seoul korea#seoul travel#seoul trips#seoul starbucks#seoul city#seoul vlog#seoul vibe#seoul blog#seoul#south korea guide#south korea headers#south korea travel#south korea trips#south korea cafe#south korea vlog#south korea blog#south korea#korea aesthetic#south korea aesthetic#korea guide#korea headers#Korea Republic

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Korean is hard

When I first started learning Korean seriously about a year ago, I already knew hangeul very well and knew some basic phrases. So I thought it was going to be easy. And to be honest, at first, it was. I went through my first beginning level textbook (Vitamin Korean 1) with ease and supplemented with TTMIK and watched tons of Korean dramas. And then I moved on to Vitamin Korean 2. I was making progress fast. Or so it seemed.

Because then I hit The Wall™.

I stopped making progress and suddenly found myself unable to make use of anything I had learned. Making sentences by myself? Impossible. Getting new grammar into my head? Nope. I was not making progress whatsoever and on top of that found myself forgetting everything I was once so sure of. I was back to square one: I could read hangeul just fine but that was about it.

I got frustrated and upset but nothing was making sense anymore. I asked people on the learning Korean subreddit about what I was experiencing and what they said wasn't helpful at all.