#Enheduana

Text

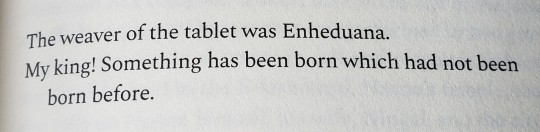

This hymn in praise of writing just punched me in the chest. We weave writing! New things are born!

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

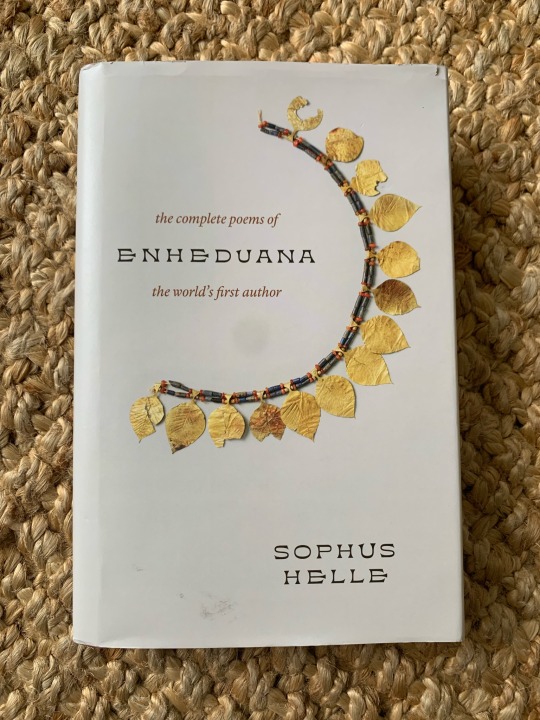

While at Elliot Bay Books, my ears perked up at a casual mention of poetry by “some woman from ancient Sumer or Ur.”

Was it Enheduana???? Yes!

I’m still bummed I missed the exhibit on Enheduana at the Morgan Library.

So, even though I had *just* said that I wasn’t ever going to haul paper books around in my suitcase again, I bought this translation by Sophus Helle.

I’m so glad I did. It’s a great book. Great subject, great writing. I can’t comment on the accuracy of the translation, but the poetry is knockout and the essays are accessible and fascinating.

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

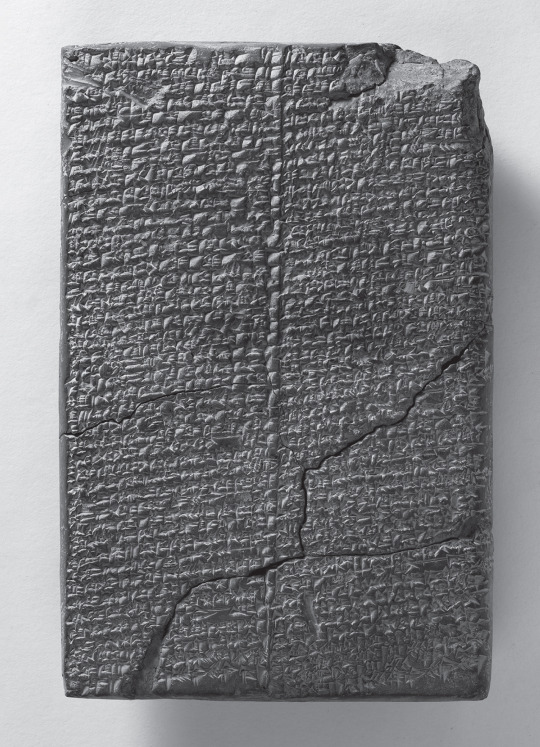

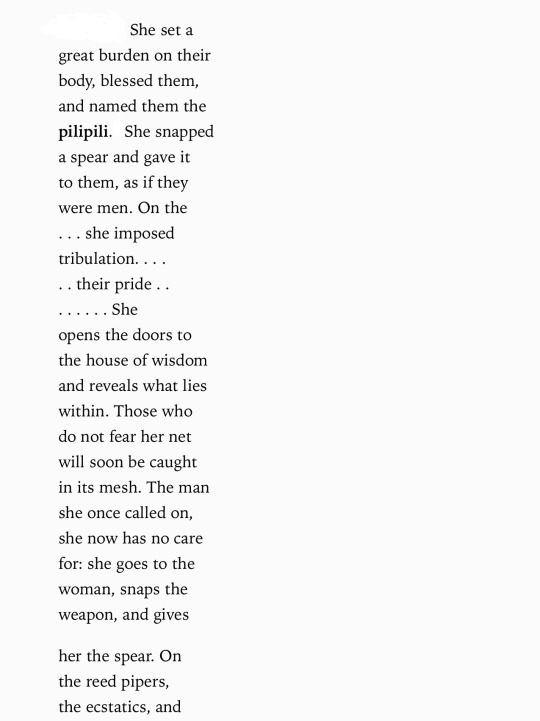

—Enheduana, from “The Hymn to Inana”

Gender-bending in the world’s most ancient authored text, newly translated by Sophus Helle.

From an essay by the translator: “The evidence for activities that sought to actively subvert established gender norms is much clearer when we turn to another and much more motley class of ritual performers. These included the kurĝara, the saĝ-ursaĝ, and the pilipili, as well as several other groups who were associated with the worship of Inana and who performed rituals in which they upended the usual conventions of gender. Ancient texts describe processions in honor of Inana in which the participants would wear female clothes on one side of their body and male clothes on the other. They would brandish weapons, which were the traditional signs of masculinity, as well as weaving instruments, such as spindles and distaffs, the traditional signs of femininity. By mixing and juxtaposing the standard symbols of gender, they would introduce an element of confusion and capriciousness into the conventions of gendered behavior: if the same person could wear both female and male clothes, viewers were led to ponder the nature of gender itself. It is highly likely that the various groups, such as the kurĝara and the saĝ-ursaĝ, would subvert gender norms in different ways: some were perhaps individuals who generally appeared to be female but performed stereotypically male actions, others the reverse, but because of the limitations of our sources, it is difficult to reconstruct the differences between them. Either way, these groups were all engaged in a playful scrambling of what was thought to be typically male and typically female.”

On the pilipili: “Inana then blessed them, named them, and gave them a snapped spear ‘as if they were a man’ (ll. 80–81). The passage implies that they were generally seen as women and that they announced their distance from normative gender by carrying a broken emblem of maleness. However, the text identifies them not with one gender or the other but with the transition between genders, referring to them as ‘the changed pilipili’ (l. 88). Together with the reed pipers, the kurĝara, the saĝ-ursaĝ, and the ecstatics, they are depicted as ritual lamenters: Inana ‘makes them weep and wail for her,’ so that they ‘exhaust themselves with tears and tears’ (ll. 87, 90).”

#literature#poetry#Inana#inanna#Enheduana#assyriology#Sophus helle#enheduanna#genderqueer#nonbinary#gender nonconforming#Sumerian literature

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

I carried the basket

of offerings, I sang

the hymns of joy.

Now they bring me

funeral gifts -- am I

no longer living?

I went to the light,

but the light burned

me; I went to the

shadow, but it was

shrouded in storms.

My honey-mouth

is full of froth, my

soothing words are

turned to dust.

-Excerpt from "The Exaltation of Inana" in The Complete Poems of Enheduana The World's First Author and translated by Sophus Helle

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The complex pantheon of Sumer sorts itself immediately into two easily recognizable categories: male gods and female gods. Goddess worship was not a separate religion, and goddesses as well as gods were an integral part of Sumerian religion and thought. The stories about goddesses do not come from any separatist women's cult and are neither female fantasies nor women's mythmaking. They are mainstream literature, the high culture of ancient Sumer. The authors of most of these compositions, male or female, are anonymous; but the earliest great poems of Sumer were written by a woman, Enheduanna, who was both En priestess of the god Nanna in the city of Ur and daughter of King Sargon of Akkad. She was the Shakespeare of ancient Sumerian literature in that her beautiful compositions were studied, copied, and recited for more than half a millennium after her death. These poems were not shared only with the women of ancient Sumer. On the contrary, we know these poems, as we know most of the literature of ancient Sumer, from copies that were made by students in the ancient Sumerian schools. Most, if not all, of these students were male. The poems of Enheduanna, and the other myths and hymns about goddesses whose authors (male or female) are unknown, were part of the curriculum of these schools, studied and taught by males. Men as well as women discussed and worshiped the goddesses of ancient Sumer.

This two-gendered pantheon mirrors the duality of nature, in which humans and other animals, and even some plants, occur as masculine and feminine. In some cases, the sex of a god makes no real difference to its function. In their control of cities, goddesses and gods play equivalent roles. The god of the city could be either male or female. In most cases, this deity also had a spouse who was less important to the wellbeing of the city than the deity itself. It was not always the male partner who was the major god. Either configuration was possible: the goddess could be the major deity, with her male spouse less significant than she; the male god could be chief deity, with a wife secondary to him.

However, in most conceptual realms, the sex division in the Sumerian divine world is not incidental. The sex of a god was crucial to that god's role and function in the thought system. Gods and goddesses are not interchangeable: the god Enlil could not be the goddess Ninlil, his spouse. The goddess Inanna could not be the god Utu, her brother. The femaleness of a goddess is essential.

-Tikva Frymer-Kensky, In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enheduana is the first poet in history whose name we know.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Your lady is the mother, the holy woman wreathed in agate,

Who cares for the Steadfast Chapel of this sacred place.

She holds the great gems of her holy women,

She has set aright the breasts of the seven priestesses.

The seven ecstasies resound for her."

-Enheduana, translated by Sophus Helle. Something like 2300 BCE.

Dunno what that means exactly but it sounds pretty sexy.

0 notes

Text

Giornata Mondiale della Poesia

Enheduana

Buongiorno cari amici, poeti e signora Poesia.La poesia è sacraLa poesia è come una preghiera,si impara a memoria e ritorna nella mentecome la musicalità di un ritornello,rimane affacciata agli pareti dell’anima.La poesia è sacra. I poeti sono umani, pochi diventano miti.Oggi non è un giorno di inizio della settimana, non è solo il primo giorno dopo il Solstizio della Primavera. Oggi è…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Let them know that your gaze is terrifying, and that you lift your terrifying gaze. Let them know that your eyes flash and flicker. Let them know that you are headstrong and defiant. Let them know that you always stand triumphant.

"The Exaltation of Inana," Enheduana, trans. Sophus Helle

191 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Let them

know that you grind

skulls to dust. Let

them know that you

eat corpses like a lion.

Enheduanna, Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World’s First Author, to Inanna

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inanna: Ishtar Sumerian Mother Goddess

Talon Abraxas

"Lady of all the divine powers, resplendent light, righteous woman clothed in radiance, beloved of An and Uraš! Mistress of heaven, with the great diadem, who loves the good headdress befitting the office of en priestess, who has seized all seven of its divine powers! My lady, you are the guardian of the great divine powers! You have taken up the divine powers, you have hung the divine powers from your hand…"

--Enheduana

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enheduanna

Enheduanna, the Akkadian poet, stands as a towering figure in ancient Mesopotamian literature, revered as the world's first known author and poet. Born around 2285 BCE, Enheduanna was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad, the legendary ruler often credited as the founder of the world's first empire. Her precise familial ties remain debated among scholars, but what's clear is that Sargon appointed her as the high priestess of the most important temple in Sumer, located in the city of Ur.

Enheduanna's contributions to literature and religion are immense. She played a pivotal role in melding the Sumerian gods with the Akkadian ones, fostering stability crucial for the thriving of Sargon's empire. Her literary works, though only rediscovered in modern times, set paradigms for poetry, psalms, and prayers that influenced religious traditions for centuries to come.

Her most celebrated compositions include hymns such as “Nin me šara” ("The Exaltation of Inanna") and “Inninmehusa” ("Goddess of the Fearsome Powers" dedicated to the goddess Inanna. These hymns redefined the perception of deities, providing a common religious identity across the empire. Enheduanna's writings also offer a glimpse into her personal frustrations, religious devotion, and responses to the world around her.

Enheduanna's life was as remarkable as her literary legacy. She endured political upheavals, including an attempted coup by a Sumerian rebel named Lugal-Ane, which forced her into exile. However, her resilience and divine intercession eventually led to her restoration as high priestess.

Despite the controversy surrounding her authorship, with some scholars questioning whether she personally wrote the hymns attributed to her, textual and historical evidence suggests otherwise. Enheduanna's works bear her name, and she explicitly claims authorship in some of her compositions.

#enheduanna#female writers#authors#mesopotamia#babylon#akkadian#sumerian#literature#history#women in history#inanna

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

from The Hymn to Inana

by Enheduana (~2300 BCE)

tr. Sophus Helle

restless, she straps

on her sandals. She

splits the blazing,

furious storm, the

whirlwind billows

around her as if

it were a dress.

#poetry#poem#writers on tumblr#writing#storm#sky#enheduanna#ancient history#ancient egypt#ancient greece#ancient art#history#dress

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your blog and I think you might be able to help with something I've been failing to get anywhere with for a while! I'd like to get a tattoo of a line from one of Enheduana's hymns to Inana, but while I've managed to find translation, transliteration and references, I don't have the research chops to find the original cuneiform, which is what I really want.

The one I'm after is translated as "To rove around, to rush, to rise up, to fall down and to ...... a companion are yours, Inana." (Line 116 of 'A hymn to Inana (Inana C)') in the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.

Any chance you could hook me up?

Here's what I've got.

The tricky thing here is that the "original cuneiform" is dense and written in 3D, which makes it difficult to duplicate in a tattoo if you're just operating off a photo. But you can find photos of this text on the CDLI here, if you scroll down, to give you a sense of the problem.

A simpler route is to "cuneify" the values of the cuneiform symbols, i.e. to convert them into standardized Unicode symbols. Those will be much easier to copy. This is, I think, the line you want, in syllabic cuneiform:

𒌨 𒊒 𒌨 𒌌 𒇻 𒌌 𒍣 𒄑 𒍣 𒄖 𒊒 𒄭 𒀭 𒋫 𒋛 𒋛 𒋼 𒀭 𒈹 𒍝 𒀀 𒄰

(You'll need to install a cuneiform font for it to display right.)

All that said, for something to be tattooed permanently on your body, you want to be certain it's correct—and at the end of the day, I only have expertise in Akkadian, not Sumerian. (They're completely different languages that share a cuneiform writing system.) I would highly advise checking with @sumerianlanguage or another Sumerologist before you get anything inked.

40 notes

·

View notes