#Eunice Quedens

Text

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2021: Mariana Prommel, Mariana Mosqueda Prommel, attrice e conduttrice televisiva argentina. La sua carriera fuori dal teatro inizia nel 1997, nel cortometraggio Kilómetro 22, e con la prima apparizione in una serie tv, Naranja y media. Dato il suo volto caratteristico, apparirà in numerose telenovele interpretando per lo più personaggi comici. Numerose altre telenovele seguirono negli anni…

View On WordPress

#Aldo Silvani#Alfredo Bambi#Anna Petrovna Fesak#Anna Sten#Ágata Lys#Dria Paola#Eunice Quedens#Eve Arden#Gabriele Tinti#Gastone Tinti#Giuseppe Tagliavia#Grace Valentine#Jonathan Brandis#Jonathan Gregory Brandis#Luciano Marin#Margarita García San Segundo#Mariana Mosqueda Prommel#Mariana Prommel#Mario Merola#Pietra Giovanna Matilde Adele Pitteo#Robert Johnson#Robert Morris#Roberto Mauri#Violet Mersereau#William Franklin Beedle#William Holden

1 note

·

View note

Text

Of Eve Arden and "Our Miss Brooks"

Of Eve Arden and “Our Miss Brooks”

When I was a kid I feel like a lot of the older women emulated Eve Arden(Eunice May Quedens, 1908-1990). Arden was beautiful and glamorous, but also imposing. She stood 5’7″, which is not quite “giant” status for a woman, but she was Germanic and big-boned, with a voice that was not precisely mannish but was definitely waxing contralto. It’s mostly her sense of style I’m thing of, an almost…

View On WordPress

#actress#Broadway#character#Eunice Quedens#Eve Arden#film#films#movie#movies#Our Miss Brooks#Show#sitcom#situation comedy#star#teacher#television#tv

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve Arden

#Eve Arden#film#radio#Hollywood#vintage#movie#actress#Eunice Mary Quedens#television#comedian#Broadway#Stage Door#Mildred Pierce#Our Miss Brooks#Grease#Grease 2#Ziegfeld Follies#RKO Radio Pictures#At the Circus#Comrade X#SUTS#TCM#Anatomy of a Murder#The Three Phases of Eve#autobiography#marriage#children#adoption#cardiac arrest#arteriosclerotic heart disease

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

EVE ARDEN

April 30, 1908

Eunice Mary Quedens (aka Eve Arden) was born in Mill Valley, California, near San Francisco. She was interested in show business from an early age. At 16, she made her stage debut after quitting school to joined a stock company.

She made her screen debut (using her given name) in Columbia’s Song of Love in 1929.

In 1938 she appeared with Lucille Ball in Stage Door along with Ginger Rogers. It was this film that earned Ball and Arden the nickname “the drop gag girls” for their skill at bringing comedy into a scene with just a short appearance.

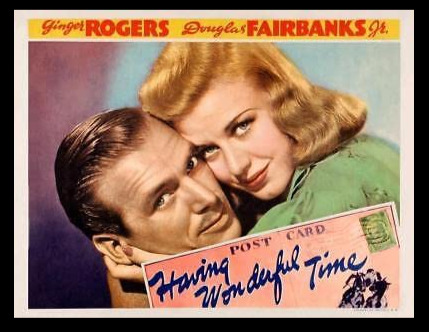

Eve, Lucy and Ginger also appeared together in Having Wonderful Time (1938).

In 1946, she earned a supporting actress Oscar nomination for her appearance in Mildred Pierce starring Joan Crawford.

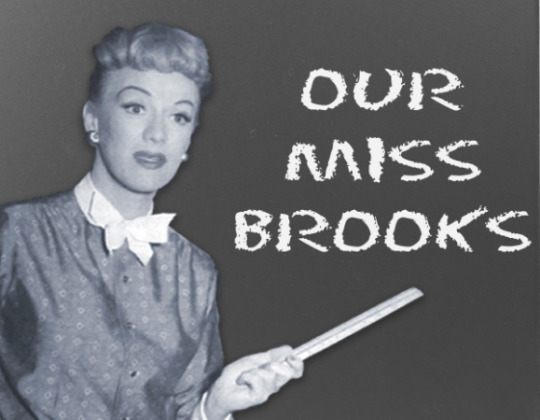

In 1948, she landed the role that would make her famous - Connie Brooks in “Our Miss Brooks” - first on radio, then on television. Arden was actually third choice for the role. CBS’s Harry Ackerman wanted Shirley Booth for the part. Lucille Ball was believed to have been the next choice, but she was committed to “My Favorite Husband” and did not audition. Brooks’ co-stars included Gale Gordon, Mary Jane Croft, and Richard Crenna, all of who also teamed with Lucille Ball on radio and television. When the show moved to television in 1952, most of the original radio cast went along with Brooks. It started a years after “I Love Lucy” and ended the same year, 1956. It was also filmed at Desilu Studios, making it convenient to share cast and crew members including, for one episode in 1955, Desi Arnaz as himself. In 1956 there was also a screen version of Our Miss Brooks starring Arden and Gale Gordon, released by Warner Brothers.

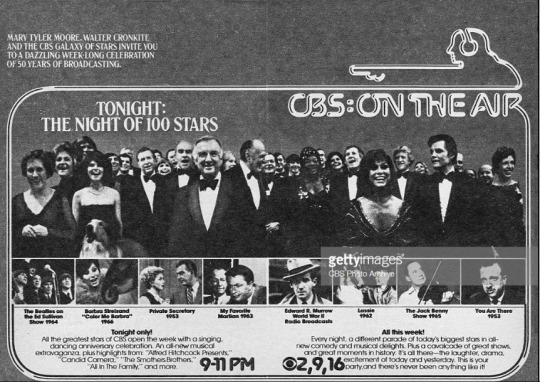

In November 1952, Lucille Ball, Eve Arden, and the casts of both their shows (as well as many other CBS programs) all appeared on “Stars in the Eye” to celebrate the opening of CBS Television City in Hollywood.

When Lucy Ricardo arrived in Hollywood in “Hollywood at Last!” aka “L.A. at Last!” (ILL S4;E16), Eve Arden became the very first celebrity to make a cameo - speaking just a few words - the epitome of her ‘drop gag girl’ reputation.

The appearance was filmed December 2, 1954 and aired on February 7, 1955.

In March 1962, Arden played Marissa Montaine on an episode of “My Three Sons”, filmed at Desilu Studios. The episode also featured Wiliam Frawley, Reta Shaw, and a dog named Tramp!

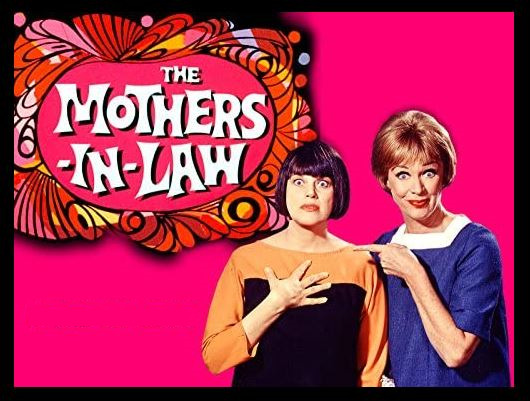

Those unfamiliar with Miss Brooks, may also remember Arden as Eve Hubbard on the Desi Arnaz sitcom “The Mothers-in-Law” alongside Kaye Ballard. The series lasted two seasons, and included appearances by its producer, Desi Arnaz.

As CBS icons, both Ball and Arden were included in “CBS On The Air" on Sunday March 26, 1978.

That same year she made another memorable appearance, as the Principal of the High School in the film version of Grease.

Her final screen appearance was on a November 1987 episode of “Falcon Crest” (above left with Jane Wyman and Eddie Albert).

She died on November 12, 1990 at age 82. She was married twice and had three children.

#Eve Arden#Lucille Ball#I Love Lucy#Our Miss Brooks#Stage Door#The Mothers-in-Law#Falcon Crest#TV#Grease#Song of Love#Having Wonderful Time#My Three Sons#CBS#Radio#Gale Gordon

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve Arden: She Knew All the Answers

“When men get around me, they get allergic to wedding rings,” says Eve Arden’s Ida in Mildred Pierce (1945), a film that won Arden her only Academy Award nomination. Ida is a good egg, a steady, loyal friend to Joan Crawford’s Mildred. “You know, big sister type,” she says, in that inimitably sardonic, wised-up, swooping voice of hers, as she pours herself a stiff drink. “Good old Ida, you can talk it over with her man to man,” she says, of those men who treat her as if she isn’t a woman. Ida says that men are “stinkers” and “heels,” but she doesn’t sound all that mad about it. There isn’t a trace of self-pity in her tone, either. Arden never asks for sympathy. In fact, she never asks for anything. Some things seem to confuse, or bemuse, her on screen, but she was usually just playing that for laughs.

Born Eunice Quedens in 1908 in Mill Valley, California, she was a child of divorce raised mainly by her mother, who encouraged her to drop out of high school and go on the stage. She toured with a stock company and made her film debut in Song of Love (1929), a creaky musical where she played a romantic rival to the heroine. She went back to the stage, only making a brief, uncredited appearance in the Joan Crawford vehicle Dancing Lady (1933) as a blond actress who gets fired when she objects to her treatment in rehearsal. She speaks in a thick Southern accent but then drops it: “I told you that Southern accent would sound phony!” she tells her agent in her own voice. There could be no such artifice for her. Even when she later did Russian and French accents on screen, they were burlesque routines and not meant to be taken seriously.

Statuesque at 5 foot 8 inches, she joined the Ziegfeld Follies in 1934 and was encouraged to change her name. Spotting a perfume bottle in her dressing room with the name Evening in Paris and a cosmetics bottle labeled Elizabeth Arden, she came up with her new name: Eve Arden. There were a few more years on stage before she returned to the movies in 1937 to play a girl called Eve in Gregory La Cava’s Stage Door. If that movie makes a religion of wisecracking, then Arden is its high priestess, lounging around the Footlights Club for out-of-work actresses with a white cat named Henry draped around her shoulders like a stole.

Eve has lines under her eyes and looks a little tired; she always seems to be reclining. She’s mainly an audience for the other girls, waiting out their carbonated and inventive complaining until the moment when she can add her own topper and make the whole place explode with laughter. “There’s no such thing as a fifty dollar bill,” she insists, and of all the girls she gives Katharine Hepburn’s society dilettante the hardest time. “Is it against the rules of the house to discuss the classics?” asks Hepburn, to which Arden replies, “No-o-o, go right ahead…I won’t take my sleeping pill tonight.”

I’ve seen Stage Door countless times, and so I know what Arden will say and when she will say it and how, but when I try to re-create some of her line readings by saying them out loud, I am unable to get them right. I think it’s because she weights every single word heavily as her reading goes playfully up and down the vocal scale but her overall delivery is still somehow airy, both throbbing with thick sarcasm and strangely light. “Olga wants peace, peace at any price!” cries one of the girls, to which Arden sharply cracks, “Well, you can’t have peace without a war.” That “war” comes out as “wa-a-er,” as if she likes to pick one word to spread her thickest sarcasm over.

When Hepburn asks her what she’s done in the theater, Arden says, “Everything but burst out of a pie at a Rotarian banquet,” a weird line, but one that Arden plays against with her facial expression. She seems to be signaling that Eve has done things like that, but she’s too tired now for chorus girl hanky-panky with jerky businessmen. “Never heard of him,” she says, when Hamlet gets mentioned. “Oh certainly you must have heard of Hamlet,” says a dim Southern girl, to which Arden replies, “Well, I meet so many people,” in a “nice,” polite, nearly ghostly fashion. It’s a profound kind of wisecrack in the very original way that Arden delivers it. She was capable of hitting a pure note of comic exhaustion, like a faded memory of a past life that does not touch her anymore.

Arden never signed to one studio for long, and she made a surprising number of poverty row and independent productions in the 1940s and early ‘50s. She wrestled with Groucho Marx in At the Circus (1939), meeting his aggression with her own, but she often found herself dead last in the cast list. In a bit in Raoul Walsh’s Manpower (1941), the 33-year-old Arden says to pal Marlene Dietrich, “I’m 25, look 35 and feel 50,” and this pitiless line got at something essential about Arden, because there isn’t much difference between her at age 30 or 50 or 70. Her type stays the same no matter what her age, a woman who is past it all and unimpressed and just making the best of things.

Weary of typecasting as sarcastic secretaries and good sports, Arden returned to the stage for a bit but soon went back to support glamour girls like Rita Hayworth in Cover Girl (1944) and Ava Gardner in One Touch of Venus (1948), which is really a film about Arden and her deepening existential dilemma as she looks at gorgeous Ava and looks at herself and wonders, “Why am I me, and why is she that?” Arden flirted with prettiness whenever she opened her blue eyes wide, but she usually did this only for parody purposes. She seems uncomfortable as a promiscuous actress in The Voice of the Turtle(1947), as if she knew that her natural role on screen was to patiently listen to the Joan Crawford’s of this world and gently mock their emotional grandiloquence from the sidelines.

After years of playing support, Arden finally won a star vehicle of her own, first on radio and then on television, as schoolteacher Connie Brooks in Our Miss Brooks, which ran through most of the 1950s. Arden was consistently, tirelessly inventive in that long-running series, mastering the art and timing of situation comedy and providing a template for later players. In the twenty or so minutes of each Our Miss Brooks episode, Arden generally manages to get at least three to four laughs. The writing for that show was usually good or at least serviceable, and if it was ever a little less than that, Arden would still find her laughs in between the lines with little looks and reactions of distaste, disgust or dismayed confusion. She could get a laugh just by smoothing down her skirt, or wincing slightly.

She returned to the screen in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959), wearing some grey in her hair as James Stewart’s loyal, kindly and largely unpaid secretary, a woman who will pour some more coffee for you in the middle of the night. It might do to say that Arden’s film characters are stoic or resigned, but that’s not quite it. There’s something else about them, something unclear but suggestive. There’s something even a little mysterious and unplaceable about Eve Arden on screen, as if she isn’t giving too much of herself away for us. She does her job, like her characters do, and we get to enjoy the sound of her helplessly skeptical voice, which enlivened many movies less classic than Stage Door, Mildred Pierce and Anatomy of a Murder, but we don’t ever really get the real her and how she actually feels. She and her characters have retreated somewhere private where they cannot be reached. Maybe that’s why she had such a long career, because audiences always wanted more of her.

She appeared on television a lot as an older woman, dryly reacting to the wacky Kaye Ballard in another series, The Mothers-In-Law, and matching her sour comic timing with Bea Arthur in an episode of Maude. She was still at school as the principal in Grease ( 1978), as if Connie Brooks had climbed up the ladder but still had to put up with inane students and low-level jokes. One of her last credits was as the Wicked Stepmother in Cinderella for Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre series in 1985. Rather satisfyingly, the 77-year-old Arden is asked to gloat over treating the pretty young Jennifer Beals “like dirt” because she and her daughters have not been as well-favored by dissembling nature.

Arden married twice, the second time happily to actor Brooks West, and she raised four children, three of whom were adopted. After her death in 1990, her long-time publicist and manager Glenn Rose said, “She kept being cast as this sarcastic, acid-tongued lady with the quick retort and put-down. In real life, Eve would have never put anyone down. She wasn’t that kind of person.“

by Dan Callahan

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eve Arden (1908- 1990) Eve was born just north of San Francisco in Mill Valley and was interested in show business from an early age. At 16, she made her stage debut after quitting school to joined a stock company. After appearing in minor roles in two films under her real name, Eunice Quedens #evearden #oldhollywood

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

12 … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2019: Luciano Marin, attore italiano, divenne uno dei volti più importanti dei maggiori fotoromanzi italiani, tra cui “Sogno” e “Grand Hotel”; venne poi scelto per il cinema. (n. 1931)

2017: Roberto Mauri, pseudonimo di Giuseppe Tagliavia, regista, sceneggiatore e attore italiano. Ha utilizzato anche gli pseudonimi Robert Johnson e Robert Morris. (n. 1924)

2006: Mario Merola, è stato un cantante,…

View On WordPress

#Aldo Silvani#Alfredo Bambi#Anna Petrovna Fesak#Anna Sten#Dria Paola#Eunice Quedens#Eve Arden#Gabriele Tinti#Gastone Tinti#Giuseppe Tagliavia#Grace Valentine#Jonathan Brandis#Jonathan Gregory Brandis#Luciano Marin#Mario Merola#Pietra Giovanna Matilde Adele Pitteo#Robert Johnson#Robert Morris#Roberto Mauri#Violet Mersereau#William Franklin Beedle#William Holden

0 notes

Text

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic #felicementechic #lynda

2019: Luciano Marin, attore italiano, divenne uno dei volti più importanti dei maggiori fotoromanzi italiani, tra cui “Sogno” e “Grand Hotel”; venne poi scelto per il cinema. (n. 1931)

2017: Roberto Mauri, pseudonimo di Giuseppe Tagliavia, regista, sceneggiatore e attore italiano. Ha utilizzato anche gli pseudonimi Robert Johnson e Robert Morris. (n. 1924)

2006: Mario Merola, è stato un cantante,…

View On WordPress

#Aldo Silvani#Alfredo Bambi#Anna Petrovna Fesak#Anna Sten#Dria Paola#Eunice Quedens#Eve Arden#Gabriele Tinti#Gastone Tinti#Giuseppe Tagliavia#Grace Valentine#Jonathan Brandis#Jonathan Gregory Brandis#Luciano Marin#Mario Merola#Pietra Giovanna Matilde Adele Pitteo#Robert Johnson#Robert Morris#Roberto Mauri#Violet Mersereau#William Franklin Beedle#William Holden

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Happy Heavenly Birthday, Eunice Mary Quedens (30 April 1908 – 12 November 1990)! She is better known as actress Eve Arden from films like Stage Door, Mildred Pierce, Anatomy of a Murder, and Grease.

#Eve Arden#movie#vintage#Hollywood#comedy#stage#Stage Door#Mildred Pierce#Grease#radio#television#The Eve Arden Show#Our Miss Brooks#classic#comedian#birthday#cardiac arrest#death#adoption#children#marriage#affair#Danny Kaye#The Doughgirls#Grease 2

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

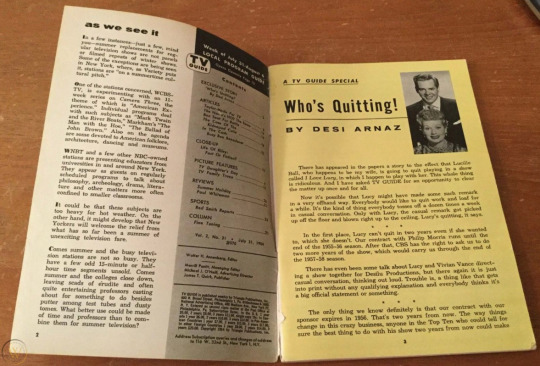

WHO’S QUITTING!

July 31, 1954

The July 31, 1954 issue of TV Guide (volume 2; number 31) featured actor William Bendix on the cover with the headline: “Who’s Quitting! Say Lucy and Desi”.

The last day of the listings in this Guide is August 6, 1954, Lucille Ball’s 43rd birthday!

The inside article is by Desi Arnaz, who takes the opportunity to correct the rumor that they are quitting their hit show, “I Love Lucy,” then preparing its fourth season. Desi reports that Lucy’s casual remark that she’d ‘like’ to quit was rhetorical and not based in reality. In fact, they were contractually obliged to Philip Morris (their sponsor) to continue until 1956. After that, CBS had the right to ask for two further seasons, taking the couple to 1958. Desi mentions that there had been some casual talk about Lucy and Vivian Vance directing a project together for Desilu. [Such a project never came to pass.] He states that by the end of their contract that they will have done 175 films. [In fact, they did 179, not including filming the “Christmas Special”, new intros for re-runs, and the unaired pilot.]

Desi predicts that they may do monthly hour-long specials, several years in advance of “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hours”, proving that even by mid-1954, the idea of cutting back their hectic schedule was discussed. Desi even theorizes that they might go fishing in Cuba! [All travel to Cuba would be stopped by the end of the 1950s.]

One thing that Desi makes very clear is to dispel the rumor that “I Love Lucy” may go on with another actress in the role of Lucy Ricardo.

“There will never be an ‘I Love Lucy’ without Lucille Ball. Period. Exclamation point!”

TV Guide’s headline is slightly misleading by the use of the exclamation point. It should actually read “Who’s Quitting?” which is essentially what Desi is wondering. You can almost hear it spoken in his Cuban accent! In all fairness to TV Guide, summer was devoid of new programming and TV Guide was looking to sell magazines by putting provocative headlines and images about top shows on the cover. This no doubt increased sales, even if there was nothing to watch.

ABOUT THE COVER:

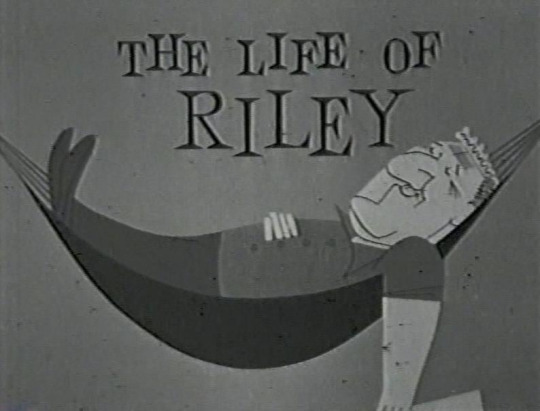

William Bendix was then starring in the NBC sitcom “The Life of Riley”. First heard on radio starring William Bendix, the series moved to TV in 1948 starring Jackie Gleason in the title role. It lasted until 1950. In 1953, the series returned with it’s original radio star (and the lead of its film version), William Bendix. At the time this TV Guide was issued, the series had just finished its second season and was readying its third (of six).

The show regularly featured two “I Love Lucy” players, Gloria Blondell (Honeybee) and Herb Vigran (Muley). Blondell played Grace Foster in “The Anniversary Present” (ILL S2;E3) in 1952 and Herb Vigran played various “Lucy” characters like Jule, Joe, and Hal Sparks.

Other actors who showed up on both “Lucy” and “Riley”: Mary Jane Croft, Richard Deacon, Vivi Janis, George O’Hanlon, Nancy Kulp, Dayton Lummis, James Burke, Florence Lake, Mary Ellen Kay, Benny Rubin, Ray Kellogg, Howard McNear, Norman Leavitt, Pierre Watkin, and Bobby Jellison.

From the Northeast Edition, a mention of “Public Defender” being moved to “I Love Lucy’s” time-slot for the summer. The episode listed in this edition featured “I Love Lucy’s” Madge Blake.

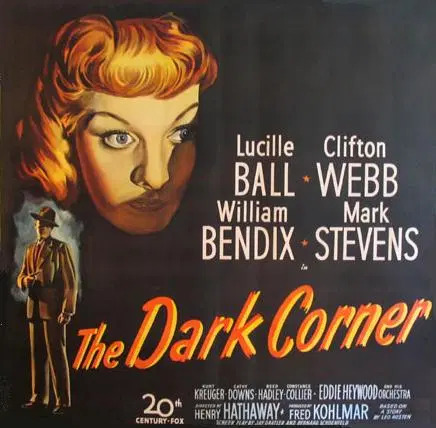

In 1946 Lucille Ball and William Bendix appeared together in the film The Dark Corner.

INSIDE THE ISSUE:

Photo feature of TV starlets Natalie Wood, Lauren Chapin, Sheilah James, Eleanor Donahue, and Elena Verdugo in swimsuits at the beach!

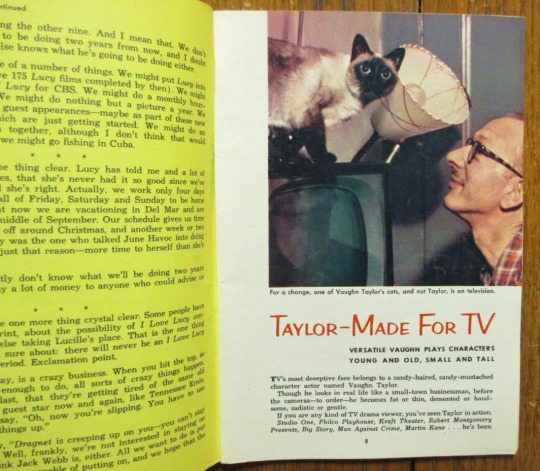

Feature on character actor Vaughn Taylor and his cats

Photo feature on the Truex family of actors. Ernest Truex had appeared with Lucille Ball in Dance, Girl, Dance (1940).

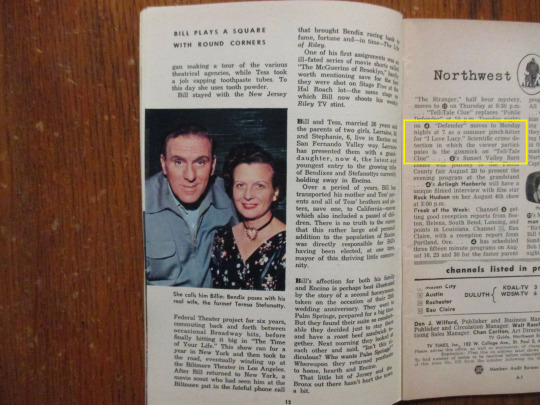

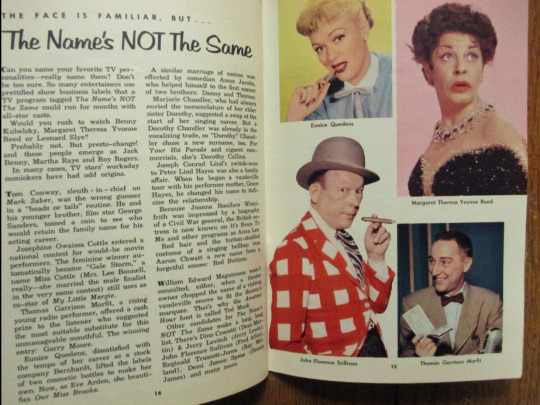

Photo feature on the real names of favorite stars. Included is Eunice Mary Quedens (aka Eve Arden) who played herself in “Hollywood at Last!” (ILL S4;E16).

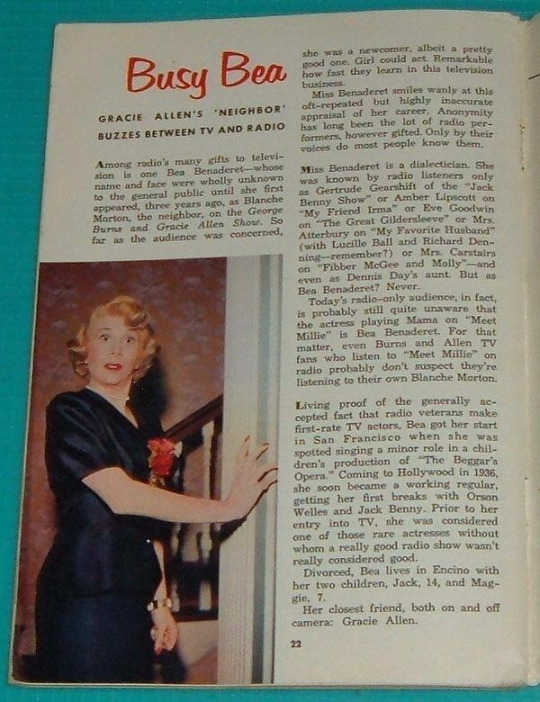

Profile on TV favorite Bea Benaderet. Benadaret had co-starred with Lucille Ball on “My Favorite Husband” and was her first pick for the role of Ethel Mertz. She played spinster Miss Lewis on “I Love Lucy.”

For More About TV Guide and “I Love Lucy” Click Here!

#TV Guide#Lucille Ball#Desi Arnaz#I Love Lucy#Bea Bendaret#Eve Arden#TV#Ernest Truex#Vaughn Taylor#The Dark Corner#William Bendix#The Life of Riley#Gloria Blondell#Herb Vigran#Public Defender#1954

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy heavenly Birthday Eunice Mary Quedens (30 April 1908 – 12 November 1990)! She is best known as actress Eve Arden from films like Stage Door, Mildred Pierce, and Anatomy of a Murder. She had many leading and supporting roles throughout her career.

#Eve Arden#actress#Hollywood#vintage#birthday#Mildred Pierce#Stage Door#comedian#radio#film#classic#talent#attitude#stage#RKO Pictures#marriage#children#heart attack#television#Grease#Comrade X#Ziegfeld Girl#Cover Girl#funny#My Reputation#movie

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eve Arden: She Knew All the Answers

“When men get around me, they get allergic to wedding rings,” says Eve Arden’s Ida in Mildred Pierce (1945), a film that won Arden her only Academy Award nomination. Ida is a good egg, a steady, loyal friend to Joan Crawford’s Mildred. “You know, big sister type,” she says, in that inimitably sardonic, wised-up, swooping voice of hers, as she pours herself a stiff drink. “Good old Ida, you can talk it over with her man to man,” she says, of those men who treat her as if she isn’t a woman. Ida says that men are “stinkers” and “heels,” but she doesn’t sound all that mad about it. There isn’t a trace of self-pity in her tone, either. Arden never asks for sympathy. In fact, she never asks for anything. Some things seem to confuse, or bemuse, her on screen, but she was usually just playing that for laughs.

Born Eunice Quedens in 1908 in Mill Valley, California, she was a child of divorce raised mainly by her mother, who encouraged her to drop out of high school and go on the stage. She toured with a stock company and made her film debut in Song of Love (1929), a creaky musical where she played a romantic rival to the heroine. She went back to the stage, only making a brief, uncredited appearance in the Joan Crawford vehicle Dancing Lady (1933) as a blond actress who gets fired when she objects to her treatment in rehearsal. She speaks in a thick Southern accent but then drops it: “I told you that Southern accent would sound phony!” she tells her agent in her own voice. There could be no such artifice for her. Even when she later did Russian and French accents on screen, they were burlesque routines and not meant to be taken seriously.

Statuesque at 5 foot 8 inches, she joined the Ziegfeld Follies in 1934 and was encouraged to change her name. Spotting a perfume bottle in her dressing room with the name Evening in Paris and a cosmetics bottle labeled Elizabeth Arden, she came up with her new name: Eve Arden. There were a few more years on stage before she returned to the movies in 1937 to play a girl called Eve in Gregory La Cava’s Stage Door. If that movie makes a religion of wisecracking, then Arden is its high priestess, lounging around the Footlights Club for out-of-work actresses with a white cat named Henry draped around her shoulders like a stole.

Eve has lines under her eyes and looks a little tired; she always seems to be reclining. She’s mainly an audience for the other girls, waiting out their carbonated and inventive complaining until the moment when she can add her own topper and make the whole place explode with laughter. “There’s no such thing as a fifty dollar bill,” she insists, and of all the girls she gives Katharine Hepburn’s society dilettante the hardest time. “Is it against the rules of the house to discuss the classics?” asks Hepburn, to which Arden replies, “No-o-o, go right ahead…I won’t take my sleeping pill tonight.”

I’ve seen Stage Door countless times, and so I know what Arden will say and when she will say it and how, but when I try to re-create some of her line readings by saying them out loud, I am unable to get them right. I think it’s because she weights every single word heavily as her reading goes playfully up and down the vocal scale but her overall delivery is still somehow airy, both throbbing with thick sarcasm and strangely light. “Olga wants peace, peace at any price!” cries one of the girls, to which Arden sharply cracks, “Well, you can’t have peace without a war.” That “war” comes out as “wa-a-er,” as if she likes to pick one word to spread her thickest sarcasm over.

When Hepburn asks her what she’s done in the theater, Arden says, “Everything but burst out of a pie at a Rotarian banquet,” a weird line, but one that Arden plays against with her facial expression. She seems to be signaling that Eve has done things like that, but she’s too tired now for chorus girl hanky-panky with jerky businessmen. “Never heard of him,” she says, when Hamlet gets mentioned. “Oh certainly you must have heard of Hamlet,” says a dim Southern girl, to which Arden replies, “Well, I meet so many people,” in a “nice,” polite, nearly ghostly fashion. It’s a profound kind of wisecrack in the very original way that Arden delivers it. She was capable of hitting a pure note of comic exhaustion, like a faded memory of a past life that does not touch her anymore.

Arden never signed to one studio for long, and she made a surprising number of poverty row and independent productions in the 1940s and early ‘50s. She wrestled with Groucho Marx in At the Circus (1939), meeting his aggression with her own, but she often found herself dead last in the cast list. In a bit in Raoul Walsh’s Manpower (1941), the 33-year-old Arden says to pal Marlene Dietrich, “I’m 25, look 35 and feel 50,” and this pitiless line got at something essential about Arden, because there isn’t much difference between her at age 30 or 50 or 70. Her type stays the same no matter what her age, a woman who is past it all and unimpressed and just making the best of things.

Weary of typecasting as sarcastic secretaries and good sports, Arden returned to the stage for a bit but soon went back to support glamour girls like Rita Hayworth in Cover Girl (1944) and Ava Gardner in One Touch of Venus (1948), which is really a film about Arden and her deepening existential dilemma as she looks at gorgeous Ava and looks at herself and wonders, “Why am I me, and why is she that?” Arden flirted with prettiness whenever she opened her blue eyes wide, but she usually did this only for parody purposes. She seems uncomfortable as a promiscuous actress in The Voice of the Turtle (1947), as if she knew that her natural role on screen was to patiently listen to the Joan Crawford’s of this world and gently mock their emotional grandiloquence from the sidelines.

After years of playing support, Arden finally won a star vehicle of her own, first on radio and then on television, as schoolteacher Connie Brooks in Our Miss Brooks, which ran through most of the 1950s. Arden was consistently, tirelessly inventive in that long-running series, mastering the art and timing of situation comedy and providing a template for later players. In the twenty or so minutes of each Our Miss Brooks episode, Arden generally manages to get at least three to four laughs. The writing for that show was usually good or at least serviceable, and if it was ever a little less than that, Arden would still find her laughs in between the lines with little looks and reactions of distaste, disgust or dismayed confusion. She could get a laugh just by smoothing down her skirt, or wincing slightly.

She returned to the screen in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959), wearing some grey in her hair as James Stewart’s loyal, kindly and largely unpaid secretary, a woman who will pour some more coffee for you in the middle of the night. It might do to say that Arden’s film characters are stoic or resigned, but that’s not quite it. There’s something else about them, something unclear but suggestive. There’s something even a little mysterious and unplaceable about Eve Arden on screen, as if she isn’t giving too much of herself away for us. She does her job, like her characters do, and we get to enjoy the sound of her helplessly skeptical voice, which enlivened many movies less classic than Stage Door, Mildred Pierce and Anatomy of a Murder, but we don’t ever really get the real her and how she actually feels. She and her characters have retreated somewhere private where they cannot be reached. Maybe that’s why she had such a long career, because audiences always wanted more of her.

She appeared on television a lot as an older woman, dryly reacting to the wacky Kaye Ballard in another series, The Mothers-In-Law, and matching her sour comic timing with Bea Arthur in an episode of Maude. She was still at school as the principal in Grease (1978), as if Connie Brooks had climbed up the ladder but still had to put up with inane students and low-level jokes. One of her last credits was as the Wicked Stepmother in Cinderella for Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre series in 1985. Rather satisfyingly, the 77-year-old Arden is asked to gloat over treating the pretty young Jennifer Beals “like dirt” because she and her daughters have not been as well-favored by dissembling nature.

Arden married twice, the second time happily to actor Brooks West, and she raised four children, three of whom were adopted. After her death in 1990, her long-time publicist and manager Glenn Rose said, “She kept being cast as this sarcastic, acid-tongued lady with the quick retort and put-down. In real life, Eve would have never put anyone down. She wasn't that kind of person."

by Dan Callahan

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 novembre … ricordiamo …

12 novembre … ricordiamo … #semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic #felicementechic #lynda

2006: Mario Merola, è stato un cantante, attore, compositore e conduttore televisivo italiano. Era soprannominato il Re della sceneggiata per essere riuscito a dare a questo genere tipicamente regionale una popolarità e una dimensione nazionale e un successo sconosciuto prima, fino a farne un genere cinematografico, rappresentando tutto questo anche fuori dal palcoscenico, riuscendo così a dare…

View On WordPress

#Aldo Silvani#Alfredo Bambi#Anna Petrovna Fesak#Anna Sten#Dria Paola#Eunice Quedens#Eve Arden#Gabriele Tinti#Gastone Tinti#Grace Valentine#Jonathan Brandis#Jonathan Gregory Brandis#Mario Merola#Pietra Giovanna Matilde Adele Pitteo#Violet Mersereau#William Franklin Beedle#William Holden

0 notes

Text

EVE ARDEN: She Knew All the Answers

“When men get around me, they get allergic to wedding rings,” says Eve Arden’s Ida in Mildred Pierce (1945), a film that won Arden her only Academy Award nomination. Ida is a good egg, a steady, loyal friend to Joan Crawford’s Mildred. “You know, big sister type,” she says, in that inimitably sardonic, wised-up, swooping voice of hers, as she pours herself a stiff drink. “Good old Ida, you can talk it over with her man to man,” she says, of those men who treat her as if she isn’t a woman. Ida says that men are “stinkers” and “heels,” but she doesn’t sound all that mad about it. There isn’t a trace of self-pity in her tone, either. Arden never asks for sympathy. In fact, she never asks for anything. Some things seem to confuse, or bemuse, her on screen, but she was usually just playing that for laughs.

Born Eunice Quedens in 1908 in Mill Valley, California, she was a child of divorce raised mainly by her mother, who encouraged her to drop out of high school and go on the stage. She toured with a stock company and made her film debut in Song of Love (1929), a creaky musical where she played a romantic rival to the heroine. She went back to the stage, only making a brief, uncredited appearance in the Joan Crawford vehicle Dancing Lady (1933) as a blond actress who gets fired when she objects to her treatment in rehearsal. She speaks in a thick Southern accent but then drops it: “I told you that Southern accent would sound phony!” she tells her agent in her own voice. There could be no such artifice for her. Even when she later did Russian and French accents on screen, they were burlesque routines and not meant to be taken seriously.

Statuesque at 5 foot 8 inches, she joined the Ziegfeld Follies in 1934 and was encouraged to change her name. Spotting a perfume bottle in her dressing room with the name Evening in Paris and a cosmetics bottle labeled Elizabeth Arden, she came up with her new name: Eve Arden. There were a few more years on stage before she returned to the movies in 1937 to play a girl called Eve in Gregory La Cava’s Stage Door. If that movie makes a religion of wisecracking, then Arden is its high priestess, lounging around the Footlights Club for out-of-work actresses with a white cat named Henry draped around her shoulders like a stole.

Eve has lines under her eyes and looks a little tired; she always seems to be reclining. She’s mainly an audience for the other girls, waiting out their carbonated and inventive complaining until the moment when she can add her own topper and make the whole place explode with laughter. “There’s no such thing as a fifty dollar bill,” she insists, and of all the girls she gives Katharine Hepburn’s society dilettante the hardest time. “Is it against the rules of the house to discuss the classics?” asks Hepburn, to which Arden replies, “No-o-o, go right ahead…I won’t take my sleeping pill tonight.”

I’ve seen Stage Door countless times, and so I know what Arden will say and when she will say it and how, but when I try to re-create some of her line readings by saying them out loud, I am unable to get them right. I think it’s because she weights every single word heavily as her reading goes playfully up and down the vocal scale but her overall delivery is still somehow airy, both throbbing with thick sarcasm and strangely light. “Olga wants peace, peace at any price!” cries one of the girls, to which Arden sharply cracks, “Well, you can’t have peace without a war.” That “war” comes out as “wa-a-er,” as if she likes to pick one word to spread her thickest sarcasm over.

When Hepburn asks her what she’s done in the theater, Arden says, “Everything but burst out of a pie at a Rotarian banquet,” a weird line, but one that Arden plays against with her facial expression. She seems to be signaling that Eve has done things like that, but she’s too tired now for chorus girl hanky-panky with jerky businessmen. “Never heard of him,” she says, when Hamlet gets mentioned. “Oh certainly you must have heard of Hamlet,” says a dim Southern girl, to which Arden replies, “Well, I meet so many people,” in a “nice,” polite, nearly ghostly fashion. It’s a profound kind of wisecrack in the very original way that Arden delivers it. She was capable of hitting a pure note of comic exhaustion, like a faded memory of a past life that does not touch her anymore.

Arden never signed to one studio for long, and she made a surprising number of poverty row and independent productions in the 1940s and early ‘50s. She wrestled with Groucho Marx in At the Circus (1939), meeting his aggression with her own, but she often found herself dead last in the cast list. In a bit in Raoul Walsh’s Manpower (1941), the 33-year-old Arden says to pal Marlene Dietrich, “I’m 25, look 35 and feel 50,” and this pitiless line got at something essential about Arden, because there isn’t much difference between her at age 30 or 50 or 70. Her type stays the same no matter what her age, a woman who is past it all and unimpressed and just making the best of things.

Weary of typecasting as sarcastic secretaries and good sports, Arden returned to the stage for a bit but soon went back to support glamour girls like Rita Hayworth in Cover Girl (1944) and Ava Gardner in One Touch of Venus (1948), which is really a film about Arden and her deepening existential dilemma as she looks at gorgeous Ava and looks at herself and wonders, “Why am I me, and why is she that?” Arden flirted with prettiness whenever she opened her blue eyes wide, but she usually did this only for parody purposes. She seems uncomfortable as a promiscuous actress in The Voice of the Turtle(1947), as if she knew that her natural role on screen was to patiently listen to the Joan Crawford’s of this world and gently mock their emotional grandiloquence from the sidelines.

After years of playing support, Arden finally won a star vehicle of her own, first on radio and then on television, as schoolteacher Connie Brooks in Our Miss Brooks, which ran through most of the 1950s. Arden was consistently, tirelessly inventive in that long-running series, mastering the art and timing of situation comedy and providing a template for later players. In the twenty or so minutes of each Our Miss Brooks episode, Arden generally manages to get at least three to four laughs. The writing for that show was usually good or at least serviceable, and if it was ever a little less than that, Arden would still find her laughs in between the lines with little looks and reactions of distaste, disgust or dismayed confusion. She could get a laugh just by smoothing down her skirt, or wincing slightly.

She returned to the screen in Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959), wearing some grey in her hair as James Stewart’s loyal, kindly and largely unpaid secretary, a woman who will pour some more coffee for you in the middle of the night. It might do to say that Arden’s film characters are stoic or resigned, but that’s not quite it. There’s something else about them, something unclear but suggestive. There’s something even a little mysterious and unplaceable about Eve Arden on screen, as if she isn’t giving too much of herself away for us. She does her job, like her characters do, and we get to enjoy the sound of her helplessly skeptical voice, which enlivened many movies less classic than Stage Door, Mildred Pierce and Anatomy of a Murder, but we don’t ever really get the real her and how she actually feels. She and her characters have retreated somewhere private where they cannot be reached. Maybe that’s why she had such a long career, because audiences always wanted more of her.

She appeared on television a lot as an older woman, dryly reacting to the wacky Kaye Ballard in another series, The Mothers-In-Law, and matching her sour comic timing with Bea Arthur in an episode of Maude. She was still at school as the principal in Grease ( 1978), as if Connie Brooks had climbed up the ladder but still had to put up with inane students and low-level jokes. One of her last credits was as the Wicked Stepmother in Cinderella for Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre series in 1985. Rather satisfyingly, the 77-year-old Arden is asked to gloat over treating the pretty young Jennifer Beals “like dirt” because she and her daughters have not been as well-favored by dissembling nature.

Arden married twice, the second time happily to actor Brooks West, and she raised four children, three of whom were adopted. After her death in 1990, her long-time publicist and manager Glenn Rose said, “She kept being cast as this sarcastic, acid-tongued lady with the quick retort and put-down. In real life, Eve would have never put anyone down. She wasn’t that kind of person.“

by Dan Callahan

20 notes

·

View notes