#Existentialist Philosophy of Technology

Text

Exploring the Philosophical Landscape of Technology: Theories and Perspectives

The philosophy of technology is a rich and evolving field that explores the nature, impact, and ethical dimensions of technology. Here are some key theories and approaches within this field:

Technological Determinism: This theory suggests that technology shapes society and human behavior more than individuals or society shape technology. It proposes that technological developments have a predetermined, often inevitable, impact on social, cultural, and economic structures.

Social Construction of Technology (SCOT): SCOT theory argues that technologies are not inherently good or bad but are socially constructed. It focuses on the process by which technologies are developed, adopted, and adapted based on the values and interests of different social groups.

Postphenomenology: Drawing from phenomenology, this approach explores how technology mediates our interactions with the world. It examines the ways in which technology influences our perception, embodiment, and experiences.

Actor-Network Theory (ANT): ANT considers both human and non-human actors (like technology) as equal participants in shaping social networks and processes. It emphasizes the role of technology in mediating human interactions and agency.

Ethics of Technology: This area of philosophy explores the ethical dimensions of technological development and use. It delves into topics such as privacy, surveillance, artificial intelligence ethics, and the moral responsibilities of technologists.

Philosophy of Information: This branch investigates the fundamental nature of information and its role in technology. It examines concepts like data, knowledge, and information ethics in the digital age.

Critical Theory of Technology: Rooted in critical theory, this approach critiques the social and political implications of technology. It seeks to uncover power structures and inequalities embedded in technological systems.

Feminist Philosophy of Technology: This perspective focuses on the intersection of gender and technology. It examines how technology can reinforce or challenge gender norms and inequalities.

Environmental Philosophy of Technology: This theory explores the environmental impact of technology, including topics like sustainability, resource depletion, and the ethics of technological solutions to environmental challenges.

Existentialist Philosophy of Technology: Drawing from existentialism, this approach considers the impact of technology on human existence and individuality. It explores questions of alienation, authenticity, and freedom in a technological world.

Human Enhancement Ethics: With the advancement of biotechnology, this theory addresses the ethical dilemmas surrounding human enhancement technologies, including genetic engineering and cognitive enhancement.

Pragmatism and Technology: Pragmatist philosophy examines how technology influences our practical, everyday experiences and shapes our interactions with the world.

These theories and approaches within the philosophy of technology provide valuable insights into how technology influences and is influenced by society, as well as the ethical considerations that arise in our increasingly technologically driven world.

#philosophy#ontology#epistemology#metaphysics#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#ethics#Philosophy of Technology#Technological Determinism#SCOT#Postphenomenology#Actor-Network Theory#Ethics of Technology#Philosophy of Information#Critical Theory of Technology#Feminist Philosophy of Technology#Environmental Philosophy of Technology#Existentialist Philosophy of Technology#Human Enhancement Ethics#Pragmatism and Technology

1 note

·

View note

Text

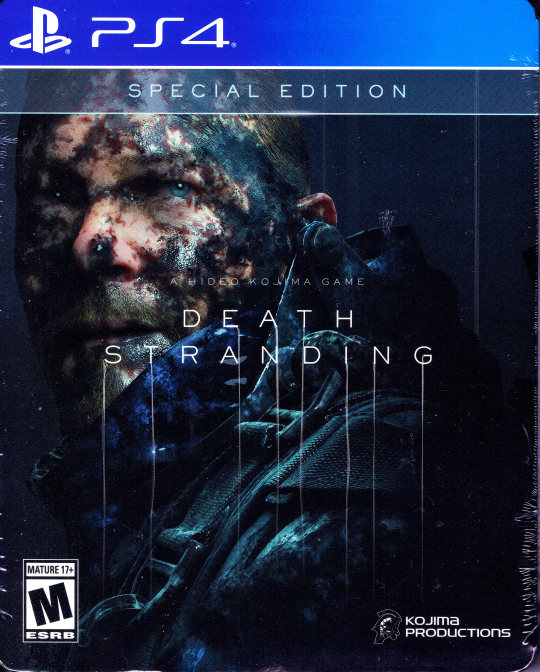

Analyzing Hideo Kojima's "Death Stranding" requires delving into the game's multifaceted narrative, themes, and mechanics, drawing on a range of philosophical disciplines including phenomenology, existentialism, eco-philosophy, and theories of connection and isolation.

1. Phenomenology and the Experience of the Game World:

"Death Stranding" immerses players in a world where the boundaries between life and death, physical and spiritual, are blurred. This can be analyzed through the lens of phenomenology, particularly the work of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The game's portrayal of a world where the dead and living coexist challenges players to reconsider the nature of reality and perception, resonating with Husserl's ideas about the subjective interpretation of experiences and Heidegger's concept of 'being-in-the-world' - how we engage with and understand our environment.

2. Existential Themes of Isolation and Connection:

The game’s exploration of isolation and the need for connection aligns with existentialist themes. Drawing from Jean-Paul Sartre’s notion of existential isolation – the idea that individuals are fundamentally alone in their subjective experiences – "Death Stranding" showcases the protagonist Sam's journey as a metaphor for human existential crises. However, in contrast to Sartre’s somewhat bleak outlook, the game also incorporates Albert Camus' philosophy of finding meaning in an absurd world, particularly through human connection and solidarity.

3. Eco-Philosophy and the Relationship with Nature:

"Death Stranding" presents a post-apocalyptic landscape that forces players to navigate and connect a fragmented world, reflecting eco-philosophical ideas. Philosophers like Arne Naess, who pioneered deep ecology, emphasized the intrinsic value of all living beings and the importance of a harmonious relationship with nature. The game’s depiction of a ravaged Earth, where human actions have severe consequences, echoes these eco-philosophical concerns, urging players to consider their relationship with and impact on the natural world.

4. The Ethics of Technology and Artificiality:

The game’s use of advanced technology, such as the Bridge Babies (BBs), and the artificial environments created to sustain life, can be analyzed through the work of philosophers like Hans Jonas and Martin Heidegger. Jonas’ ethics of responsibility and his caution about technological advancements pose relevant questions about the moral implications of using technology to manipulate and control natural processes. Heidegger’s critique of technology and its alienating effects is also pertinent in understanding the game's narrative.

5. The Concept of Death and Mortality:

"Death Stranding’s" central theme of death invites reflection on mortality from a philosophical standpoint. Arthur Schopenhauer’s pessimistic philosophy, which views death as an integral part of life, and his exploration of the will to live despite suffering, offer insights into the game’s narrative. The constant presence of death in the game challenges players to confront their mortality and find purpose in a transient existence.

6. Derrida and the Notion of Hauntology:

Jacques Derrida’s concept of hauntology – the presence of elements from the past as spectral or haunting forces in the present – is a useful framework for analyzing "Death Stranding’s" narrative, where past events and deceased individuals continue to impact the living world. The game’s portrayal of timefall, an accelerated aging process, and the presence of BTs (Beached Things), entities from the afterlife, resonate with Derrida’s ideas about the persistence of the past and its impact on present reality.

In conclusion, "Death Stranding" offers a rich tapestry for philosophical exploration, intertwining themes of phenomenology, existentialism, eco-philosophy, technology, mortality, and hauntology. Through its immersive world and narrative, the game invites players to engage with profound questions about human existence, our relationship with nature and technology, and the ever-present reality of death and memory. Kojima's creation stands as a compelling intersection of gaming and philosophical inquiry, challenging players to ponder deeply about the nature of our existence and connections in an increasingly fragmented world.

#Hideo Kojima#Death Stranding#BB#Bridges#sam bridges#Cliff Unger#Amelie#Higgs Monaghan#Peter Englert#Fragile#Bridge Baby#Die-Hardman#Deadman#Heartman#PlayStation 4#PS4#PlayStation 5#PS5#Pixel Crisis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Evolution of the Essay Format: From Montaigne to Modern Times

The essay, a literary form that allows writers to explore ideas, express personal thoughts, and engage with the world, has a rich and diverse history. Its evolution is a testament to the ever-changing intellectual, cultural, and technological landscape. It all began in the 16th century when Michel de Montaigne, a French philosopher, popularized the essay as a means of introspection and self-expression. Since then, the essay has undergone remarkable transformations, adapting to different eras, movements, and mediums. From the Enlightenment's structured arguments to the 19th-century exploration of transcendentalism, from the personal essays of Virginia Woolf to the digital age's online platforms, this essay traces the fascinating journey of the essay format through the centuries.

Literary Movements and Essays: The essay format often reflects the dominant literary movements of its time. For example, during the Romantic era, essayists like William Hazlitt and Samuel Taylor Coleridge incorporated elements of emotional expression and individualism into their essays.

Social Commentary and Reform: Essays have been powerful tools for advocating social change. In the mid-19th century, essays by authors like Harriet Beecher Stowe ("Uncle Tom's Cabin") and Frederick Douglass ("Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass") played significant roles in the anti-slavery movement.

Existentialism and Absurdism: In the mid-20th century, existentialist and absurdist philosophies influenced essays that explored the meaninglessness of existence and the search for individual purpose. Albert Camus' essay "The Myth of Sisyphus" is a notable example.

Digital Essay Forms: The digital age has given rise to new essay formats, such as the video essay, which combines visuals and spoken word to convey complex ideas. This format is particularly popular on platforms like YouTube.

In tracing the evolution of the essay format from Montaigne's contemplative musings to the dynamic, diverse, and accessible essays of today, we see a form that has continually adapted to the changing tides of human thought and expression. From philosophical treatises to personal reflections, from structured arguments to experimental narratives, the essay has proven its enduring relevance. As it continues to embrace new mediums and voices in the digital age, the essay remains a vital vehicle for the exploration of ideas, the critique of society, and the expression of individuality. Its journey from past to present is a testament to the enduring power of words and the ever-evolving nature of human discourse.

#college life#student#study#studying#university#student life#college#study space#study hard#exam stress#studystudystudy#study aesthetic#school motivation#uni life#writing#college essay#college living

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Heidegger on Technology

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) was perhaps the most divisive philosopher of the twentieth century. Many hold him to be the most original and important thinker of his era. Others spurn him as an obscurantist and a charlatan, while still others see his reprehensible affiliation with the Nazis as a reason to ignore or reject his thinking altogether. But Heidegger’s undoubted influence on contemporary philosophy and his unique insight into the place of technology in modern life make him a thinker worthy of careful study.

In his landmark book Being and Time (1927), Heidegger made the bold claim that Western thought from Plato onward had forgotten or ignored the fundamental question of what it means for something to be — to be present for us prior to any philosophical or scientific analysis. He sought to clarify throughout his work how, since the rise of Greek philosophy, Western civilization had been on a trajectory toward nihilism, and he believed that the contemporary cultural and intellectual crisis — our decline toward nihilism — was intimately linked to this forgetting of being. Only a rediscovery of being and the realm in which it is revealed might save modern man.

In his later writings on technology, which mainly concern us in this essay, Heidegger draws attention to technology’s place in bringing about our decline by constricting our experience of things as they are. He argues that we now view nature, and increasingly human beings too, only technologically — that is, we see nature and people only as raw material for technical operations. Heidegger seeks to illuminate this phenomenon and to find a way of thinking by which we might be saved from its controlling power, to which, he believes, modern civilization both in the communist East and the democratic West has been shackled. We might escape this bondage, Heidegger argues, not by rejecting technology, but by perceiving its danger.

Heidegger’s Life and Influence

The son of a sexton, Martin Heidegger was born in southern Germany in 1889 and was schooled for the priesthood from an early age. He began his training as a seminary student, but then concentrated increasingly on philosophy, natural science, and mathematics, receiving a doctorate in philosophy from the University of Freiburg. Shortly after the end of the Great War (in which he served briefly near its conclusion), he started his teaching career at Freiburg in 1919 as the assistant to Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology. Heidegger’s courses soon became popular among Germany’s students. In 1923 he began to teach at the University of Marburg, and then took Husserl’s post at Freiburg after Husserl retired from active teaching in 1928. The publication of Being and Time in 1927 had sealed his reputation in Europe as a significant thinker.

Heidegger’s influence is indicated in part by the reputation of those who studied under him and who respected his intellectual force. Hannah Arendt, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hans Jonas, Jacob Klein, Karl Löwith, and Leo Strauss all took classes with Heidegger. Among these students, even those who broke from Heidegger’s teachings understood him to be the deepest thinker of his time. Although he became recognized as the leading figure of existentialism, he distanced himself from the existentialism of philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre. In Heidegger’s view, they turned his unique thought about man’s being in the world into yet another nihilistic assertion of the dominance of human beings over all things. He insisted that terms such as anxiety, care, resoluteness, and authenticity, which had become famous through Being and Time, were for him elements of the “openness of being” in which we find ourselves, not psychological characteristics or descriptions of human willfulness, as some existentialists understood them.

Heidegger’s intellectual reputation in the United States preceded much direct acquaintance with his work because of the prominence of existentialism and the influence of his students, several of whom had fled Germany for the United States long before translators began producing English editions of his important works. (Being and Time was first translated in 1962.) Arendt in particular, who had immigrated to America in the early 1940s, encouraged the introduction of her teacher’s work into the United States. Heidegger’s most popular if indirect significance was during existentialism’s heyday from the end of the Second World War until its nearly simultaneous apotheosis and collapse on the hazy streets of San Francisco. Late Sixties Be-Ins — mass gatherings in celebration of American counterculture — appropriated existentialist themes; Heidegger’s intellectual rigor had been turned into mush, but it was still more or less recognizably Heideggerian mush. Herbert Marcuse, a hero to the more intellectual among the Sixties gaggle, was an early student of Heidegger’s, and his books such as Eros and Civilization and One-Dimensional Man owe something to him, if more to Freud and, especially, Marx.

After the 1960s, Heidegger’s intellectual radicalism became increasingly domesticated by the American academy, where wild spirits so often go to die a lingering bourgeois death. His works were translated, taught, and transformed into theses fit for tenure-committee review. Still, Heidegger’s influence among American philosophy professors has remained limited (although not entirely negligible), since most of them are, as Nietzsche might say, essentially gastroenterologists with a theoretical bent. Heidegger became more influential, though usually indirectly, for the ways artists and architects talk about their work — no one can conjure a “built space” quite as well as Heidegger does, for instance in his essay “Building Dwelling Thinking.” And much of Heidegger can also be heard in the deconstructionist lingo of literary “theory” that over the past forty years has nearly killed literature. The result is that “Heidegger” is now a minor academic industry in many American humanities departments, even as he remains relatively unappreciated by most professional philosophers.

But Heidegger’s influence is not only limited by the lack of respect most of our philosophy professors have toward his work. More troubling for many both within and outside the academy is Heidegger’s affiliation with the Nazis before and during the Second World War. His mentor Edmund Husserl was dismissed from the University of Freiburg in 1933 because of his Jewish background. Heidegger became rector of the university in that same year, and joined the Nazi party, of which he remained a member until the end of the war. Even though he resigned the rectorship after less than a year and distanced himself from the party not long after joining, he never publicly denounced the party nor publicly regretted his membership. (He is said to have once remarked privately to a student that his political involvement with the Nazis was “the greatest stupidity of his life.”) After the war, on the recommendation of erstwhile friends such as Karl Jaspers, he was banned by the Allied forces from teaching until 1951.

For obvious reasons, some of Heidegger’s friends and followers have, from the end of the war to the present day, obfuscated the relationship between Heidegger’s thought and his politics. They are surely aided in this by Heidegger’s masterful ambiguity — for him it really does depend on what the meaning of the word “is” is. His admirers do not want his work to be ignored preemptively because of his affiliation with the Nazis. Heidegger, after all, was not Hitler’s confidant, or an architect of the war and the extermination camps, but a thinker who engaged in several shameful actions toward Jews, and for a time supported the Nazis publicly, and thought he could lead the regime intellectually.

This matter has come under renewed attention with the recent release of Heidegger’s “Black Notebooks,” which are a kind of philosophical diary he kept in the 1930s and 1940s and whose contents fill a six-hundred-page volume. In his will, Heidegger had requested that these notebooks not be published until after the rest of his extensive work was released. The notebooks’ editor, Peter Trawny, reports that they contain hostile references to “world Jewry” that indicate “that anti-Semitism tied in to his philosophy.” Careful study of these notebooks will be required to determine whether they in fact provide new evidence of Heidegger’s anti-Semitism and affiliation with the Nazis that is even more damning than what is already widely known. No one who has examined Heidegger is surprised by what has been reported. But the question still remains whether Heidegger’s thought and politics are intrinsically linked, or whether, as his apologists would have it, his thought is no more (and in fact, less) related to his politics than it is to his interest in soccer and skiing. In truth, it would be surprising if the connection between the philosophy and the political beliefs and actions of a thinker of Heidegger’s rank were simply random.

In fact, Heidegger’s association with the Nazis was far from accidental. One of his infamous remarks on politics was a statement about the “inner truth and greatness” of National Socialism that he made in a 1935 lecture course. In a 1953 republication of that speech as Introduction to Metaphysics, Heidegger appended a parenthetical clarification, which he claimed was written but not delivered in 1935, of what he believed that “inner truth and greatness” to be: “the encounter between global technology and modern humanity.” Some scholars, taking the added comment as a criticism of the Nazis, point to Heidegger’s explanation, following the speech’s publication, that the meaning of the original comment would have been clear to anyone who understood the speech correctly. But perhaps we should not be surprised to find a thinker so worried about “global technology” affiliating with the Nazi Party in the first place. The Nazis were opposed to the two dominant forms of government of the day that Heidegger associated with “global technology,” communism and democracy. In another of Heidegger’s infamous political remarks, made in that same 1935 lecture, he claimed that “Russia and America, seen metaphysically, are both the same: the same hopeless frenzy of enchained technology and of the rootless organization of the average man.” The Nazi’s rhetoric about “blood and soil” and the mythology of an ancient, wise, and virtuous German Volk might also have appealed to someone concerned with the homogenizing consequences of globalization and technology. More broadly, Heidegger’s thought always was and remained illiberal, tending to encompass all matters, philosophy and politics among them, in a single perspective, ignoring the freedom of most people to act independently. The ways in which liberal democracies promote excellence and useful competition were not among the political ideas to which Heidegger’s thought was open. His totalizing, illiberal thought made his joining the Nazis much more likely than his condemning them.

The study of Heidegger is both dangerous and difficult — the way he is taught today threatens to obscure his thought’s connection to his politics while at the same time transforming his work into fodder for the aimless curiosity of the academic industry. Heidegger would not be surprised to discover that he is now part of the problem that he meant to address. But if, as Heidegger hoped, his works are to help us understand the challenges technology presents, we must study him both carefully and cautiously — carefully, to appreciate the depth and complexity of his thought, and cautiously, in light of his association with the Nazis.

Technology as Revealing

Heidegger’s concern with technology is not limited to his writings that are explicitly dedicated to it, and a full appreciation of his views on technology requires some understanding of how the problem of technology fits into his broader philosophical project and phenomenological approach. (Phenomenology, for Heidegger, is a method that tries to let things show themselves in their own way, and not see them in advance through a technical or theoretical lens.) The most important argument in Being and Time that is relevant for Heidegger’s later thinking about technology is that theoretical activities such as the natural sciences depend on views of time and space that narrow the understanding implicit in how we deal with the ordinary world of action and concern. We cannot construct meaningful distance and direction, or understand the opportunities for action, from science’s neutral, mathematical understanding of space and time. Indeed, this detached and “objective” scientific view of the world restricts our everyday understanding. Our ordinary use of things and our “concernful dealings” within the world are pathways to a more fundamental and more truthful understanding of man and being than the sciences provide; science flattens the richness of ordinary concern. By placing science back within the realm of experience from which it originates, and by examining the way our scientific understanding of time, space, and nature derives from our more fundamental experience of the world, Heidegger, together with his teacher Husserl and some of his students such as Jacob Klein and Alexandre Koyré, helped to establish new ways of thinking about the history and philosophy of science.

Heidegger applies this understanding of experience in later writings that are focused explicitly on technology, where he goes beyond the traditional view of technology as machines and technical procedures. He instead tries to think through the essence of technology as a way in which we encounter entities generally, including nature, ourselves, and, indeed, everything. Heidegger’s most influential work on technology is the lecture “The Question Concerning Technology,” published in 1954, which was a revised version of part two of a four-part lecture series he delivered in Bremen in 1949 (his first public speaking appearance since the end of the war). These Bremen lectures have recently been translated into English, for the first time, by Andrew J. Mitchell.

Introducing the Bremen lectures, Heidegger observes that because of technology, “all distances in time and space are shrinking” and “yet the hasty setting aside of all distances brings no nearness; for nearness does not consist in a small amount of distance.” The lectures set out to examine what this nearness is that remains absent and is “even warded off by the restless removal of distances.” As we shall see, we have become almost incapable of experiencing this nearness, let alone understanding it, because all things increasingly present themselves to us as technological: we see them and treat them as what Heidegger calls a “standing reserve,” supplies in a storeroom, as it were, pieces of inventory to be ordered and conscripted, assembled and disassembled, set up and set aside. Everything approaches us merely as a source of energy or as something we must organize. We treat even human capabilities as though they were only means for technological procedures, as when a worker becomes nothing but an instrument for production. Leaders and planners, along with the rest of us, are mere human resources to be arranged, rearranged, and disposed of. Each and every thing that presents itself technologically thereby loses its distinctive independence and form. We push aside, obscure, or simply cannot see, other possibilities.

Common attempts to rectify this situation don’t solve the problem and instead are part of it. We tend to believe that technology is a means to our ends and a human activity under our control. But in truth we now conceive of means, ends, and ourselves as fungible and manipulable. Control and direction are technological control and direction. Our attempts to master technology still remain within its walls, reinforcing them. As Heidegger says in the third of his Bremen lectures, “all this opining concerning technology” — the common critique of technology that denounces its harmful effects, as well as the belief that technology is nothing but a blessing, and especially the view that technology is a neutral tool to be wielded either for good or evil — all of this only shows “how the dominance of the essence of technology orders into its plundering even and especially the human conceptions concerning technology.” This is because “with all these conceptions and valuations one is from the outset unwittingly in agreement that technology would be a means to an end.” This “instrumental” view of technology is correct, but it “does not show us technology’s essence.” It is correct because it sees something pertinent about technology, but it is essentially misleading and not true because it does not see how technology is a way that all entities, not merely machines and technical processes, now present themselves.

Of course, were there no way out of technological thinking, Heidegger’s own standpoint, however sophisticated, would also be trapped within it. He attempts to show a way out — a way to think about technology that is not itself beholden to technology. This leads us into a realm that will be familiar to those acquainted with Heidegger’s work on “being,” the central issue in Being and Time and one that is also prominent in some of the Bremen lectures. The basic phenomenon that belongs together with being is truth, or “revealing,” which is the phenomenon Heidegger brings forward in his discussion in “The Question Concerning Technology.” Things can show or reveal themselves to us in different ways, and it is attention to this that will help us recognize that technology is itself one of these ways, but only one. Other kinds of revealing, and attention to the realm of truth and being as such, will allow us to “experience the technological within its own bounds.”

Only then will “another whole realm for the essence of technology … open itself up to us. It is the realm of revealing, i.e., of truth.” Placing ourselves back in this realm avoids the reduction of things and of ourselves to mere supplies and reserves. This step, however, does not guarantee that we will fully enter, live within, or experience this realm. Nor can we predict what technology’s fate or ours will be once we do experience it. We can at most say that older and more enduring ways of thought and experience might be reinvigorated and re-inspired. Heidegger believes his work to be preparatory, illuminating ways of being and of being human that are not merely technological.

One way by which Heidegger believes he can enter this realm is by attending to the original meaning of crucial words and the phenomena they reveal. Original language — words that precede explicit philosophical, technological, and scientific thought and sometimes survive in colloquial speech — often shows what is true more tellingly than modern speech does. (Some poets are for Heidegger better guides on the quest for truth than professional philosophers.) The two decisive languages, Heidegger thinks, are Greek and German; Greek because our philosophical heritage derives its terms from it (often in distorted form), and German, because its words can often be traced to an origin undistorted by philosophical reflection or by Latin interpretations of the Greek. (Some critics believe that Heidegger’s reliance on what they think are fanciful etymologies warps his understanding.)

Much more worrisome, however, is that Heidegger’s thought, while promising a comprehensive view of the essence of technology, by virtue of its inclusiveness threatens to blur distinctions that are central to human concerns. Moreover, his emphasis on technology’s broad and uncanny scope ignores or occludes the importance and possibility of ethical and political choice. This twofold problem is most evident in the best-known passage from the second Bremen lecture: “Agriculture is now a mechanized food industry, in essence the same as the production of corpses in the gas chambers and extermination camps, the same as the blockading and starving of countries, the same as the production of hydrogen bombs.” From what standpoint could mechanized agriculture and the Nazis’ extermination camps be “in essence the same”? If there is such a standpoint, should it not be ignored or at least modified because it overlooks or trivializes the most significant matters of choice, in this case the ability to detect and deal with grave injustice? Whatever the full and subtle meaning of “in essence the same” is, Heidegger fails to address the difference in ethical weight between the two phenomena he compares, or to show a path for just political choice. While Heidegger purports to attend to concrete, ordinary experience, he does not consider seriously justice and injustice as fundamental aspects of this experience. Instead, Heidegger claims that what is “horrifying” is not any of technology’s particular harmful effects but “what transposes … all that is out of its previous essence” — that is to say, what is dangerous is that technology displaces beings from what they originally were, hindering our ability to experience them truly.

What Is the Essence of Technology?

Let us now follow Heidegger’s understanding of technology more exactingly, relying on the Bremen lectures and “The Question Concerning Technology,” and beginning with four points of Heidegger’s critique (some of which we have already touched on).

First, the essence of technology is not something we make; it is a mode of being, or of revealing. This means that technological things have their own novel kind of presence, endurance, and connections among parts and wholes. They have their own way of presenting themselves and the world in which they operate. The essence of technology is, for Heidegger, not the best or most characteristic instance of technology, nor is it a nebulous generality, a form or idea. Rather, to consider technology essentially is to see it as an event to which we belong: the structuring, ordering, and “requisitioning” of everything around us, and of ourselves. The second point is that technology even holds sway over beings that we do not normally think of as technological, such as gods and history. Third, the essence of technology as Heidegger discusses it is primarily a matter of modern and industrial technology. He is less concerned with the ancient and old tools and techniques that antedate modernity; the essence of technology is revealed in factories and industrial processes, not in hammers and plows. And fourth, for Heidegger, technology is not simply the practical application of natural science. Instead, modern natural science can understand nature in the characteristically scientific manner only because nature has already, in advance, come to light as a set of calculable, orderable forces — that is to say, technologically.

Some concrete examples from Heidegger’s writings will help us develop these themes. When Heidegger says that technology reveals things to us as “standing reserve,” he means that everything is imposed upon or “challenged” to be an orderly resource for technical application, which in turn we take as a resource for further use, and so on interminably. For example, we challenge land to yield coal, treating the land as nothing but a coal reserve. The coal is then stored, “on call, ready to deliver the sun’s warmth that is stored in it,” which is then “challenged forth for heat, which in turn is ordered to deliver steam whose pressure turns the wheels that keep a factory running.” The factories are themselves challenged to produce tools “through which once again machines are set to work and maintained.”

The passive voice in this account indicates that these acts occur not primarily by our own doing; we belong to the activity. Technological conscriptions of things occur in a sense prior to our actual technical use of them, because things must be (and be seen as) already available resources in order for them to be used in this fashion. This availability makes planning for technical ends possible; it is the heart of what in the Sixties and Seventies was called the inescapable “system.” But these technical ends are never ends in themselves: “A success is that type of consequence that itself remains assigned to the yielding of further consequences.” This chain does not move toward anything that has its own presence, but, instead, “only enters into its circuit,” and is “regulating and securing” natural resources and energies in this never-ending fashion.

Technology also replaces the familiar connection of parts to wholes; everything is just an exchangeable piece. For example, while a deer or a tree or a wine jug may “stand on its own” and have its own presence, an automobile does not: it is challenged “for a further conducting along, which itself sets in place the promotion of commerce.” Machines and other pieces of inventory are not parts of self-standing wholes, but arrive piece by piece. These pieces do share themselves with others in a sort of unity, but they are isolated, “shattered,” and confined to a “circuit of orderability.” The isolated pieces, moreover, are uniform and exchangeable. We can replace one piece of standing reserve with another. By contrast, “My hand … is not a piece of me. I myself am entirely in each gesture of the hand, every single time.”

Human beings too are now exchangeable pieces. A forester “is today positioned by the lumber industry. Whether he knows it or not, he is in his own way a piece of inventory in the cellulose stock” delivered to newspapers and magazines. These in turn, as Heidegger puts it in “The Question Concerning Technology,” “set public opinion to swallowing what is printed, so that a set configuration of opinion becomes available on demand.” Similarly, radio and its employees belong to the standing reserve of the public sphere; everything in the public sphere is ordered “for anyone and everyone without distinction.” Even the radio listener, whom we are nowadays accustomed to thinking of as a free consumer of mass media — after all, he “is entirely free to turn the device on and off” — is actually still confined in the technological system of producing public opinion. “Indeed, he is only free in the sense that each time he must free himself from the coercive insistence of the public sphere that nevertheless ineluctably persists.”

But the essence of technology does not just affect things and people. It “attacks everything that is: Nature and history, humans, and divinities.” When theologians on occasion cite the beauty of atomic physics or the subtleties of quantum mechanics as evidence for the existence of God, they have, Heidegger says, placed God “into the realm of the orderable.” God becomes technologized. (Heidegger’s word for the essence of technology is Gestell. While the translator of the Bremen lectures, Andrew Mitchell, renders it as “positionality,” William Lovitt, the translator of “The Question Concerning Technology” in 1977 chose the term “enframing.” It almost goes without saying that neither term can bring out all the nuances that Heidegger has in mind.)

The heart of the matter for Heidegger is thus not in any particular machine, process, or resource, but rather in the “challenging”: the way the essence of technology operates on our understanding of all matters and on the presence of those matters themselves — the all-pervasive way we confront (and are confronted by) the technological world. Everything encountered technologically is exploited for some technical use. It is important to note, as suggested earlier, that when Heidegger speaks of technology’s essence in terms of challenging or positionality, he speaks of modern technology, and excludes traditional arts and tools that we might in some sense consider technological. For instance, the people who cross the Rhine by walking over a simple bridge might also seem to be using the bridge to challenge the river, making it a piece in an endless chain of use. But Heidegger argues that the bridge in fact allows the river to be itself, to stand within its own flow and form. By contrast, a hydroelectric plant and its dams and structures transform the river into just one more element in an energy-producing sequence. Similarly, the traditional activities of peasants do not “challenge the farmland.” Rather, they protect the crops, leaving them “to the discretion of the growing forces,” whereas “agriculture is now a mechanized food industry.”

Modern machines are therefore not merely more developed, or self-propelled, versions of old tools such as water or spinning wheels. Technology’s essence “has already from the outset abolished all those places where the spinning wheel and water mill previously stood.” Heidegger is not concerned with the elusive question of precisely dating the origin of modern technology, a question that some think important in order to understand it. But he does claim that well before the rise of industrial mechanization in the eighteenth century, technology’s essence was already in place. “It first of all lit up the region within which the invention of something like power-producing machines could at all be sought out and attempted.” We cannot capture the essence of technology by describing the makeup of a machine, for “every construction of every machine already moves within the essential space of technology.”

Even if the essence of technology does not originate in the rise of mechanization, can we at least show how it follows from the way we apprehend nature? After all, Heidegger says, the essence of technology “begins its reign” when modern natural science is born in the early seventeenth century. But in fact we cannot show this because in Heidegger’s view the relationship between science and technology is the reverse of how we usually think it to be; natural forces and materials belong to technology, rather than the other way around. It was technological thinking that first understood nature in such a way that nature could be challenged to unlock its forces and energy. The challenge preceded the unlocking; the essence of technology is thus prior to natural science. “Modern technology is not applied natural science, far more is modern natural science the application of the essence of technology.” Nature is therefore “the fundamental piece of inventory of the technological standing reserve — and nothing else.”

Given this view of technology, it follows that any scientific account obscures the essential being of many things, including their nearness. So when Heidegger discusses technology and nearness, he assures us that he is not simply repeating the cliché that technology makes the world smaller. “What is decisive,” he writes, “is not that the distances are diminishing with the help of technology, but rather that nearness remains outstanding.” In order to experience nearness, we must encounter things in their truth. And no matter how much we believe that science will let us “encounter the actual in its actuality,” science only offers us representations of things. It “only ever encounters that which its manner of representation has previously admitted as a possible object for itself.”

An example from the second lecture illustrates what Heidegger means. Scientifically speaking, the distance between a house and the tree in front of it can be measured neutrally: it is thirty feet. But in our everyday lives, that distance is not as neutral, not as abstract. Instead, the distance is an aspect of our concern with the tree and the house: the experience of walking, of seeing the tree’s shape grow larger as I come closer, and of the growing separation from the home as I walk away from it. In the scientific account, “distance appears to be first achieved in an opposition” between viewer and object. By becoming indifferent to things as they concern us, by representing both the distance and the object as simple but useful mathematical entities or philosophical ideas, we lose our truest experience of nearness and distance.

Turning To and Away from Danger

It is becoming clear by now that in order to understand the essence of technology we must also understand things non-technologically; we must enter the realm where things can show themselves to us truthfully in a manner not limited to the technological. But technology is such a domineering force that it all but eliminates our ability to experience this realm. The possibility of understanding the interrelated, meaningful, practical involvements with our surroundings that Heidegger describes is almost obliterated. The danger is that technology’s domination fully darkens and makes us forget our understanding of ourselves as the beings who can stand within this realm.

The third Bremen lecture lays out just how severe the problem is. While we have already seen how the essence of technology prevents us from encountering the reality of the world, now Heidegger points out that technology has become the world (“world and positionality are the same”). Technology reigns, and we therefore forget being altogether and our own essential freedom — we no longer even realize the world we have lost. Ways of experiencing distance and time other than through the ever more precise neutral measuring with rulers and clocks become lost to us; they no longer seem to be types of knowing at all but are at most vague poetic representations. While many other critics of technology point to obvious dangers associated with it, Heidegger emphasizes a different kind of threat: the possibility that it may prevent us from experiencing “the call of a more primal truth.” The problem is not just that technology makes it harder for us to access that realm, but that it makes us altogether forget that the realm exists.

Yet, Heidegger argues, recognizing this danger allows us to glimpse and then respond to what is forgotten. The understanding of man’s essence as openness to this realm and of technology as only one way in which things can reveal themselves is the guide for keeping technology within its proper bounds. Early in the fourth and last Bremen lecture, Heidegger asks if the danger of technology means “that the human is powerless against technology and delivered over to it for better or worse.” No, he says. The question, however, is not how one should act with regard to technology — the question that seems to be “always closest and solely urgent” — but how we should think, for technology “can never be overcome,” we are never its master. Proper thinking and speaking, on the other hand, allow us to be ourselves and to reveal being. “Language is … never merely the expression of thinking, feeling, and willing. Language is the inceptual dimension within which the human essence is first capable of corresponding to being.” It is through language, by a way of thinking, that “we first learn to dwell in the realm” of being.

The thought that opens up the possibility of a “turn” away from technology and toward its essential realm is the realization of its danger. Heidegger quotes the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin: “But where the danger is, there grows also what saves.” By illuminating this danger, Heidegger’s path of thinking is a guide for turning away from it. The turn brings us to a place in which the truth of being becomes visible as if by a flash of lightning. This flash does not just illuminate the truth of being, it also illuminates us: we are “caught sight of in the insight.” As our own essence comes to light, if we disavow “human stubbornness” and cast ourselves “before this insight,” so too does the essence of technology come to light.

The Way of Nature and Poetry

Acloser look at “The Question Concerning Technology” and some of the ways it adds to the Bremen lectures will help us further to clarify Heidegger’s view. In the Bremen lectures, Heidegger focuses on the contrast between entities seen as pieces in an endless technological chain on the one hand, and “things” that reveal being by bringing to light the rich interplay between gods and humans, earth and sky on the other. His example of such a “thing” in the first lecture is a wine jug used for sacrificial libation: The full jug gathers in itself the earth’s nutrients, rain, sunshine, human festivities, and the gift to the gods. All of these together help us understand what the wine jug is. In “The Question Concerning Technology,” it is products understood in a certain way that Heidegger contrasts with technology’s revealing. Drawing on Aristotle’s account of formal, final, material, and efficient causes, Heidegger argues that both nature (physis) and art (poiesis) are ways of “bringing-forth” — of unconcealing that which is concealed. What is natural is self-producing, self-arising, self-illuminating, not what can be calculated in order to become a formless resource. Poetry also brings things to presence. Heidegger explains that the Greek word techne, from which “technology” derives, at one time also meant the “bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful” and “the poiesis of the fine arts.”

In contrast to Heidegger’s notion of a thing or of revealing stands the kind of objectivity for which our natural sciences strive. But in spite of what Heidegger himself borrows from Greek thought, he emphasizes that there is a link between modern technology and classic philosophy because of Plato’s understanding of being as permanent presence. For Plato, the “idea” of a thing — what it is — is its enduring look, which “is not and never will be perceivable with physical eyes” and cannot be experienced with the other senses either. This attention to what is purely present in contemplation, Heidegger argues, ultimately leads us to forget the being of things, what is brought forth, and the world of human concern.

Heidegger’s brief sketches in these lectures suggest powerful alternatives to technological understanding that help us to recognize its limits. In “The Question Concerning Technology,” Heidegger’s hope is to “prepare a free relationship to [technology]. The relationship will be free if it opens our human existence to the essence of technology.” It is not the case “that technology is the fate of our age, where ‘fate’ means the inevitableness of an unalterable course.” Experiencing technology as a kind — but only one kind — of revealing, and seeing man’s essential place as one that is open to different kinds of revealing frees us from “the stultified compulsion to push on blindly with technology or, what comes to the same, to rebel helplessly against it and curse it as the work of the devil.” Indeed, Heidegger says at the end of the lecture, our examining or questioning of the essence of technology and other kinds of revealing is “the piety of thought.” By this questioning we may be saved from technology’s rule.

Meaning and Mortality

Heidegger’s discussions offer several useful directions for dealing with technology, even if one disagrees with elements of his analysis. Consider his view of distance, where he differentiates neutral measured distance and geometrical shape from the spaces and distances with which we concern ourselves day by day. Someone thousands of miles away can be immediately present to one’s feelings and thoughts. Two tables may have identical size, yet each may be too big or small for comfortable, practical, or beautiful use. Heidegger’s understanding of the importance of space changes somewhat in his works, but what matters for us is his insistence that our understanding of the spaces in which we live is neither inferior nor reducible to a neutral, technical, scientific understanding of space. This is also true of time, direction, and similar matters. Perhaps most profoundly, Heidegger attempts to make visible an understanding of what is present, enduring, and essential that differs from a notion of the eternal based on time understood narrowly and neutrally. Heidegger’s alternatives provide ways to clarify the irreducibility of our experience to what we can capture technologically, or through natural science. One example of this irreducibility is Aristotle’s virtue, which acts in light of the right time, the right place, and the right amount, not in terms of measures that are abstracted from experience. Ordinary human ways of understanding are not mere folk opinion that is subservient to science, as some might say; they offer an account of how things are that can be true in its own way.

A second direction that Heidegger gives us for properly situating technology is his novel understanding of human being. For Heidegger, the traits that make us human are connected to our openness to being and to what can be revealed, to our standing in a clearing where things can approach us meaningfully. One feature of this understanding is that Heidegger pays attention to the place of moods as well as of reason in allowing things to be intelligible. Another feature is his concern for the unity in meaning in what is and is not, in presence and absence. For instance, an absent friend impresses on us the possibility of friendship as much as one who stands before us.

Central to Heidegger’s understanding of human being is the importance of death and dying in our understanding of our independence and wholeness. The importance of dying governs his choice of one of the examples he uses in the second Bremen lecture to clarify the difference between technology and ordinary concern:

The carpenter produces a table, but also a coffin…. [He] does not complete a box for a corpse. The coffin is from the outset placed in a privileged spot of the farmhouse where the dead peasant still lingers. There, a coffin is still called a “death-tree.” The death of the deceased flourishes in it. This flourishing determines the house and farmstead, the ones who dwell there, their kin, and the neighborhood. Everything is otherwise in the motorized burial industry of the big city. Here no death-trees are produced.

The significance of mortality fits together with Heidegger’s thought about reverence and gods. Gratitude, thankfulness, and restraint are proper responses to knowing ourselves as beings who are mortal. Heidegger does not have in mind dignity in a conventional moral or Christian sense. Rather, he has in view the inviolability of being human and of things as they can be revealed. Reestablishing the experience of reverence is central for limiting the control of technological thinking.

The Necessity of Making Distinctions

Heidegger’s arguments about technology also raise several difficulties. Most pressingly, he obscures the grounds for ranking what we may choose, and thus for choice itself. How exactly are the death camps different from, and more horrible than, mechanized agriculture, if they are “in essence” the same? How can we understand technology to be powerful but not so rigidly encompassing as to eclipse possibilities for ethical action?

Heidegger’s analysis of technology has something in common with what the early modern thinkers — from Machiavelli through Locke and beyond — who first established the link between modern science and practical life, considered to be radical in their endeavors: the importance of truth merely as effectiveness, of nature as conquerable, of energy and force as tools for control. In contrast to Heidegger, however, for these thinkers such views are tied to a larger argument about happiness and what is good. Now, these early modern views of science and practical life — and alternative views, such as those expressed in classical thought — seem to be the true grounds for understanding the dominance of technology, and also for our ability to limit this dominance. The question we must ask is what Heidegger adds to the discussion of these thinkers, if they account for the realm of openness, revealing, and significance that Heidegger appears to have discovered, while affording grounds for moral ranking and prudential judgment absent in Heidegger.

Indeed, one might ask (despite Heidegger’s objection to the question) whence technology arises in its essence. Is the way that beings present themselves to us meaningful only in Heidegger’s sense, or can an account be given for this meaning that at the same time allows and even demands moral choice and openness to being beyond what Heidegger allows? Because matters appear to us technologically in a way that seems tied to choices we make based on particular views of happiness, of the good, and of the sacred (all of which are at least to some extent subject to rational discussion), isn’t it true that everything technological can be judged, disputed, evaluated, and ranked? Is our understanding of happiness, of the good, and of the sacred truly subservient to a prior understanding of entities as technological, or is it instead interspersed and coeval with it, or even prior to it?

We see in Heidegger’s other works instances where he amalgamates radical differences, similar to if less grotesque than comparing death camps and mechanized agriculture, such as his claim that America and communist Russia are “metaphysically” the same, both equally dominated by technology and the “rootless organization of the average man.” This claim again indicates how Heidegger’s view of metaphysical identity can distort significant differences, and how to attend to and choose among them. Things that present themselves technologically in Heidegger’s sense seem so controlled by a pervasive unified horizon that the possibility of our grasping and ranking these differences — whether from within a technological understanding or from outside — remains obscure. In response, we might suggest that the distortion and the overreaching that make elements of technology questionable are in fact visible within technological activity itself because of the larger political and ordered world to which it belongs. This is not a causally reductive relation, but a descriptive and organizing one. To experience technology is also to experience its limits. We recognize the gulf between death camps and mechanized agriculture, and the difference in kind between Soviet tyranny and American freedom, despite seeming similarities with respect to the place of technology, because these belong to larger wholes about which we can judge. Perhaps the key to understanding technology and to guiding it is, despite Heidegger’s animadversions, precisely to wonder about the ordinary question of how to use technology well, not piece by piece to serve isolated desires, but as part of a whole way of life.

~

Mark Blitz · Winter 2014.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

25 Books to Expand Your Mind

Embarking on a journey to expand your mind through reading is a noble and enriching endeavor. The books you choose to read can significantly influence your perspective, knowledge, and understanding of the world. From timeless classics to modern masterpieces, certain books have the power to transform your thinking, challenge your perceptions, and inspire your imagination. This article curates a list of 25 books that promise to broaden your horizons and deepen your intellect.

Philosophy and Critical Thinking

Delving into philosophy and critical thinking sharpens your ability to question and understand the world around you. These books offer profound insights into human thought, ethics, and existence.

"Meditations" by Marcus Aurelius - A timeless collection of personal writings by the Roman Emperor, offering wisdom on stoicism and the art of living.

"Sophie's World" by Jostein Gaarder - A novel that doubles as an introductory guide to philosophy, exploring major philosophical ideas and thinkers.

"Thinking, Fast and Slow" by Daniel Kahneman - A groundbreaking exploration of the two systems that drive the way we think and make decisions.

"The Republic" by Plato - A foundational text in Western philosophy and political theory, discussing justice, the ideal state, and the philosopher-king.

"Nausea" by Jean-Paul Sartre - A novel that introduces existentialist themes, exploring the absurdity of existence and the search for meaning.

Science and Innovation

Understanding the universe and the groundbreaking innovations that shape our world can profoundly expand your mind. These books cover significant scientific theories, discoveries, and technological advancements.

"A Brief History of Time" by Stephen Hawking - An accessible exploration of cosmology, black holes, and the nature of the universe.

"The Selfish Gene" by Richard Dawkins - A revolutionary look at evolution from the viewpoint of genes, introducing the concept of the "meme."

"Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind" by Yuval Noah Harari - A thought-provoking overview of human history, from the Stone Age to the 21st century.

"The Innovators" by Walter Isaacson - A history of the digital revolution and the people who made it happen, from Ada Lovelace to Steve Jobs.

"Guns, Germs, and Steel" by Jared Diamond - An examination of how environmental and geographical factors have shaped the modern world.

Literature and Fiction

Great literature and fiction can transport you to other worlds, offering insights into human nature, society, and the complexity of relationships. These works are celebrated for their narrative depth and emotional impact.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee - A powerful tale of racial injustice in the American South, seen through the eyes of a young girl.

"1984" by George Orwell - A dystopian novel that explores the dangers of totalitarianism, surveillance, and loss of individuality.

"The Catcher in the Rye" by J.D. Salinger - A classic coming-of-age story that captures the teenage experience of alienation and rebellion.

"One Hundred Years of Solitude" by Gabriel García Márquez - A masterpiece of magical realism, telling the multi-generational story of the Buendía family.

"The Great Gatsby" by F. Scott Fitzgerald - A critique of the American Dream set in the Roaring Twenties, known for its lyrical prose and tragic hero.

Psychology and the Mind

Exploring the intricacies of the human mind and behavior can offer invaluable insights into yourself and others. These books delve into psychology, mental health, and the science of happiness.

"Man's Search for Meaning" by Viktor E. Frankl - A psychiatrist's memoir of surviving Nazi concentration camps, with lessons on finding purpose in suffering.

"Thinking in Bets" by Annie Duke - A professional poker player's guide to making smarter decisions when you don't have all the facts.

"Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking" by Susan Cain - An exploration of introversion and its strengths in a society that values extroversion.

"The Power of Habit" by Charles Duhigg - An examination of how habits work and how they can be changed to transform our lives.

"Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience" by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi - A look at how engaging in activities that produce a state of "flow" can enhance happiness and achievement.

History and Culture

Understanding the events, ideas, and movements that have shaped human history and culture is essential for a well-rounded perspective. These books offer compelling narratives and analyses of historical and cultural phenomena.

"The Silk Roads: A New History of the World" by Peter Frankopan - A reevaluation of world history with a focus on the importance of the East-West trade routes.

"Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind" by Yuval Noah Harari (also listed under Science and Innovation) - Offers insights into human cultural evolution.

"The Guns of August" by Barbara W. Tuchman - A Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the first month of World War I, illustrating the complexities of historical events.

"The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration" by Isabel Wilkerson - The story of the great migration of African Americans from the South to northern and western cities.

"Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed" by Jared Diamond - An analysis of why some societies collapse and others survive, focusing on environmental and social factors.

Conclusion

Expanding your mind through reading is a lifelong journey that enriches your understanding of the world and yourself. The 25 books listed here span a wide range of genres and disciplines, each offering unique insights and perspectives. Whether you're exploring the depths of human psychology, the complexities of history, or the mysteries of the universe, these books promise to challenge your perceptions and stimulate your intellect.

0 notes

Text

Beyond Bars: Unraveling the Bird in the Cage Illusion

The bird in the cage illusion, a captivating and thought-provoking metaphor, invites us to ponder the essence of freedom, confinement, and the intricate dance between the two. This compelling concept has been explored in various forms of art, literature, and philosophy, captivating minds and sparking conversations about the nature of captivity and the quest for true liberation. In this exploration, we delve into the symbolism of the bird in the cage illusion, its historical significance, and the diverse ways it has been interpreted across different disciplines.

The Symbolism of the Bird in the Cage Illusion

Freedom and Confinement:

At its core, the bird in the cage illusion symbolizes the paradoxical relationship between freedom and confinement. The image of a bird within the confines of a cage represents the tension between the desire for autonomy and the reality of limitations.

Metaphor for the Human Condition:

The bird in the cage is a powerful metaphor for the human experience. It speaks to the universal longing for freedom, the struggle against constraints, and the complex interplay between societal expectations and individual aspirations.

Historical Context and Cultural Expressions

Artistic Representations:

Throughout art history, the bird in the cage has been a recurring motif in paintings, sculptures, and literature. Artists often use this metaphor to convey themes of captivity, longing, and the human spirit's yearning for liberation. Famous works, such as Ren← Magritte's "The False Mirror" and Salvador Dal■'s "The Elephants," incorporate this symbol to evoke contemplation.

Literary Allusions:

In literature, the bird in the cage illusion has been employed by writers to explore themes of confinement and emancipation. Notable examples include Maya Angelou's poem "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings" and the symbolism-rich novella "The Metamorphosis" by Franz Kafka. These works use the bird in the cage as a metaphor for societal constraints and the desire for personal freedom.

Psychological and Philosophical Reflections

Existentialism and Freedom:

Existentialist thinkers, such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, delve into the philosophical implications of the bird in the cage illusion. Sartre's concept of "bad faith" explores how individuals may willingly accept societal norms and restrictions, resembling a bird choosing to stay in the cage despite the possibility of flight.

Psychological Insights:

Psychologically, the bird in the cage can be analyzed through the lens of cognitive dissonance and learned helplessness. The bird, conditioned to accept its confinement, may develop a mindset that resigns itself to captivity, even when the opportunity for freedom is presented.

Modern Interpretations and Societal Commentary

Social and Political Allegory:

In contemporary contexts, the bird in the cage illusion serves as a poignant metaphor for societal structures, political systems, and the struggle for individual rights. Activists and artists often employ this symbol to comment on issues of oppression, censorship, and the fight for justice and equality.

Technology and Virtual Confinement:

In the digital age, the bird in the cage illusion takes on new dimensions. The metaphor extends to discussions about the impact of technology on personal freedom, with debates on surveillance, online privacy, and the potential constraints imposed by the virtual world.

Breaking Free: A Call to Action

Empowerment and Liberation:

The bird in the cage illusion is not merely a symbol of captivity; it is also a call to action. It invites individuals to reflect on their own cages—be they societal expectations, self-imposed limitations, or external constraints—and consider the possibilities of breaking free and embracing personal empowerment.

Cultivating Resilience:

Understanding the bird in the cage illusion involves cultivating resilience and the courage to challenge the status quo. It encourages individuals to question existing norms, envision a life outside the confines of societal expectations, and actively pursue paths that align with their authentic selves.

For more info:-

magickits magic shop

tarantula magic kit

junior magic kit

magician kit for 5 year old

0 notes

Text

thinking about john and the mad scientist trope in the respect that he is both a scientist and ‘mad,’ as in psychologically unstable, but also the trope itself as an examination of the dehumanizing potential of science and the mentality of progress at any cost, disregarding ethics, and how he’s the antithesis of that. he’s the embodiment of humanity on multiple fronts. he’s the literal embodiment of humanity in the respect that he’s the only human present for all but a few episodes of the show, but he’s also the embodiment of humanity as an antonym of what is inhumane (benevolence, compassion, tolerance, tenderness, mercy). then you get his opposite in the more traditional mad scientist villains i.e., the scarrans and their hybrid breeding program, scorpius and his aurora chair and relentless pursuit of wormhole knowledge, the nebari and their mind cleansing, and the peacekeepers’ fascist adherence to reason and disgust over sentimentality for the supposed sake of the greater good. you also see it in the rest of humanity, first in a human reaction, dissecting the first aliens they come into contact with for study, then again in terra firma which displays in literal terms the same nuclear proliferation metaphor you get with the wormhole weapon in the rest of the show (the only way to create peace is by obtaining access to world-ending technology), and it comes up literally again in dna mad scientist where john equates the titular character to mengele, connecting the idea to humanity directly in its condemnation of the ends justify the means mentality.

his role in the story is in trying to hold off this relentless march of progress which everyone else pursues despite the obvious reality that it can only end in total, senseless destruction. all of this connects into the fact that the show itself is a commentary on a genre that is dedicated to exploring the philosophy and possibilities of science, and how that genre has, at times, fallen into those same pitfalls of dehumanization and mindless progress, particularly in viewing science through a militaristic lens. at no point is a condemnation of science, ‘madness,’ or science fiction, which is why it’s important that john is both a scientist and fundamentally psychologically broken by the violence he endures at the hands of the actual ‘mad scientists’ (the portrayal of which is treated with particularly notable empathy and compassion as well). (i think it’s interesting too how the peacekeepers actually devalue science hierarchically, even as they promote rationality over anything remotely romantic or emotional, and then science only as far as it is practically advantageous to military pursuits). instead, it reenforces science as positive only insofar as it reflects the best qualities of humanity: compassion, empathy, inclination to help others, desire to reduce suffering, etc. seeing this from an existentialist perspective is also really interesting because existentialism debunks the myth of progress. progress in and of itself is totally meaningless. if existence, especially from an atheistic and rationalistic perspective, has no fundamental truth or inherent meaning, then there is nothing to progress toward. we are moving forward just for the sake of moving forward, so there is no ‘ends justify the means,’ because there is no end. there is only your life as it is and what you choose to do with it, which defines the overall message that science is good only as far as it positively impacts your life and the lives of others, but that sacrificing humanity in the name of progress is an empty justification in every conceivable sense.

#*#farscape#john crichton#(drawing the existentialism connection from the kierkegaard similarities not just pulling it out of my ass)#considered saving this for the episode close read series i've been wanting to do but... nah...#anyways best show best boy as always#i think you could probably make a prometheus/forbidden knowledge connection with the wormhole knowledge as well#but maybe that's for a different post#meta

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

GAMSAT exam is tomorrow. 1030am - wow that’s come around quick. Am I ready?

Today I have gone through topics and examples of essays and ways to provide evidence to support my arguments in Task A responses. Maybe even Task B, who knows! The GAMSAT can throw anything at you!

I started with HISTORY.

- technological advancements

- knowledge improvements

- increased access to resources (link. Human needs, desires, necessities... Maslows Hierarchy!!)

——————

Current issues:

- COVID-19 Pandemic

- Past provides information for the future, coping mechanisms and trends connecting past to now

——————

Revolutions - increase citizens quality of life

- French Revolution: liberalism, capitalism and democracy

- Russian Revolution: communism, socialism, world affairs e.g. fall of Soviet Union

—————

Psychology - Sigmund Freud

Through studies of psychology, human mind and the source to seek virtue and happiness, the theory of the unconscious and the structure of the subconscious through analysis of dreams and the existence of mental illness and mental thought, is our unconscious experiences what we as humans frame as life. That our unconscious informs our behaviours and feelings. Our thoughts and actions. Which is essential is enduring a relatable and productive way of living. Through maslows hierarchy of needs we can strive towards personal growth, self actualisation and desires through the capabilities of physiological and biological requirements of the everyday necessities but more importantly the thought process and control of our lives. The security and predictability of our motivational theory of life. That we need control and safety to be sane basically. The upmost importance of love and belonging through emotional interconnectedness of friendships and relationships to continue our desire to strive.

___________

Philosophy - Heidegger, Socrates and Arisotle

Philosopher martin heidegger is a existentialist underpinning the notion that we have a reason here on earth, that there’s a fundamental worth in improving what he calls the “dasein”, the “being-here”. The experience of human existence. Of being human.

Aristotle is a Greek philosopher that we in modern day society continue to practice through the study of happiness and the pursuit of a life well lived. Aristotle coined the idea to at friendship is the fundamental to human relationships, to seek virtue and reason. One of the joys in life is a life well lived, through truly meaningful friendships “the essence of life”

All philosophers are ambitious. They have a strong drive to success, full of motivation and eagerly desirous of achieving power, wealth all characterised by ambition.

The fundamental intention of philosophy

- some regard it as a contemplation of all time and all existence

- some find it as a way to uncover and describe unity

Socrates is a philosopher and Socrates is ambitious.

• Socrates studied the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality and existence.

• principles of behaviour, love of wisdom, values, basic human needs (link - Maslow), understand fundamental truths

Socrates was a teacher. A scholar and a philosopher. He studied systems of logic and reason - coined fundamentals of modern western philosophy - irony and methodology. He coined justice and truth by reasoning all things. Existence, happiness and wisdom.

Ok my brain hurts... even though it can’t because your brain doesn’t have nerve endings.... so scientifically speaking - my head hurts.

Until tomorrow.

Geeeee out 🤎🤎

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Authenticity

The concept of authenticity is deeply rooted in existentialist philosophy and has been a significant topic of discussion in various philosophical traditions. At its core, authenticity involves living a life that is true to one's self, values, and beliefs, rather than conforming to external pressures or societal expectations. This exploration delves into the philosophy of authenticity, its origins, key ideas, and its relevance in contemporary life.

Key Concepts in the Philosophy of Authenticity

Existentialism and Authenticity:

Origins: The notion of authenticity is most closely associated with existentialist philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Kierkegaard: Kierkegaard emphasized the importance of individual faith and subjective experience, urging individuals to make authentic choices that reflect their true selves.

Heidegger: In "Being and Time," Heidegger discusses authenticity as being true to one's own existence (Dasein) and not succumbing to the "they-self," which represents societal norms and expectations.

Sartre: Sartre's existentialism posits that existence precedes essence, meaning individuals must create their own essence through authentic choices, taking full responsibility for their actions.

Authenticity and Self-Discovery:

Concept: Authenticity involves a continuous process of self-discovery and self-creation.

Argument: To be authentic, one must engage in introspection and recognize their own desires, values, and beliefs, distinguishing them from those imposed by society.

Authenticity vs. Inauthenticity:

Concept: Inauthenticity arises when individuals conform to external pressures and live in a way that is not true to themselves.

Argument: Heidegger describes inauthenticity as living according to the "they-self," where individuals adopt the roles, behaviors, and beliefs dictated by others rather than their own.

Freedom and Responsibility:

Concept: Authenticity is closely linked to the existentialist notion of freedom and the responsibility that comes with it.

Argument: Sartre asserts that individuals are "condemned to be free," meaning they must take responsibility for their choices and the authenticity of their lives, without blaming external factors.

Authenticity in Modern Life:

Concept: The pursuit of authenticity remains relevant in the context of modernity, where societal norms, technological advancements, and consumer culture often challenge individual authenticity.

Argument: In contemporary society, maintaining authenticity involves resisting the pressures of social media, consumerism, and other external influences that promote a superficial or conformist lifestyle.

Theoretical Perspectives on Authenticity

Existentialist Perspective: