#Feature:

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rare Six-Planet Star System Discovery is Music to Astronomers’ Ears - Technology Org

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/rare-six-planet-star-system-discovery-is-music-to-astronomers-ears-technology-org/

Rare Six-Planet Star System Discovery is Music to Astronomers’ Ears - Technology Org

A rare star system with six exoplanets has been discovered with an architecture unchanged for billions of years.

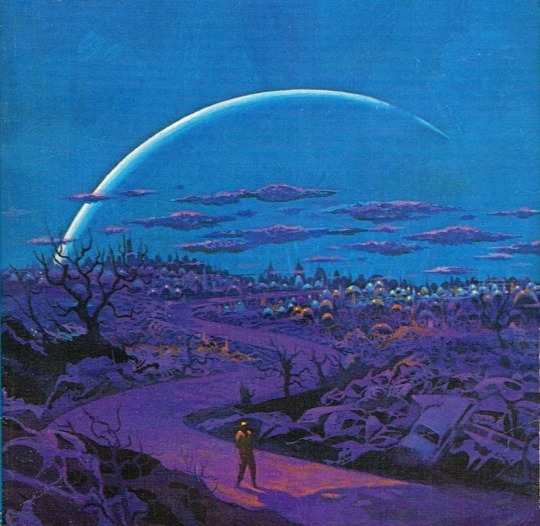

Exoplanet – illustrative photo. Image credit: Pixabay (Free Pixabay license)

The star, HD110067, that is 100 light-years away in the northern constellation of Coma Berenices, has been perplexing researchers for years. Now scientists, including those at the University of Warwick, have revealed the true architecture of this unusual system using NASA and ESA spacecrafts.

The first indication of planets orbiting the strange star system came in 2020, when NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) detected dips in the star’s brightness that suggested planets were passing in between the star and the TESS spacecraft. A preliminary analysis revealed two possible planets. One with a year (or an orbital period – the time it takes to complete one orbit around the star) of 5.64 days and another with an unknown period at the time.

Two years later, TESS observed the same star again. Analysing all data ruled out the original interpretation but presented two additional possible planets, changing the picture of the planetary system completely.

youtube

Much was still unknown about the planetary system, and that was when Rafael Luque of the University of Chicago and scientists across the world – including those at the University of Warwick – joined the investigation. They used data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), hoping to determine the orbital periods of these faraway planets.

The CHEOPS data was key in confirming a third planet in the system and the team had found the key to unlocking the whole system. It was now clear that the three planets were in a pattern of orbits known as an ‘orbital resonance’. For example, an outer planet takes 20.52 days to orbit, which is extremely close to 1.5 times the orbital period of the next planet with 13.67 days. This in turn is almost exactly 1.5 times the orbital period of the inner planet, with 9.11 days.

Thomas Wilson, Department of Physics, University of Warwick, said: “By establishing this pattern of planet orbits, we were able to predict other orbits of planets we hadn’t yet detected. From this we lined up previously unexplained dips in starlight observed by CHEOPS and discovered three additional planets with longer orbits. This was only possible with the crucial CHEOPS data.”

Orbitally resonant systems are extremely important to find because they tell astronomers about the formation and subsequent evolution of the planetary system. Planets around stars tend to form in resonance but can easily have their orbits thrown around.

For example, a very massive planet, a close encounter with a passing star, or a giant impact event can all disrupt the careful balance. As a result, many of the multi-planet systems known to astronomers are not in resonance meaning that multi-planet systems preserving their resonance are rare.

“We think only about one percent of all systems stay in resonance,” explains Rafael Luque. That why HD110067 is special and invites further study. “It shows us the pristine configuration of a planetary system that has survived untouched.”

“As our science team puts it: CHEOPS is making outstanding discoveries sound ordinary. Out of only three known six-planet resonant systems, this is now the second one found by CHEOPS, and in only three years of operations,” says Maximilian Günther, ESA project scientist for CHEOPS.

HD110067 is the brightest known system with four or more planets. Since those planets are all sub-Neptune-sized with likely larger atmospheres, it makes them ideal candidates for studying the composition of their atmospheres using the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope and the ESA’s future Ariel telescope. Whereas ESA’s upcoming PLATO telescope, due to be launched in 2026, within which the University of Warwick is playing a leading role, could find planets in this system with even longer years.

Thomas Wilson added: “All of these planets have large atmospheres – similar to Uranus or Neptune – which makes them perfect for observation with JWST. It would be fascinating to test if these planets are rocky like Earth or Venus but with larger atmospheres – solid surfaces potentially with water. However, they are all much hotter than Earth, 170-530 degrees Celsius, which would make it very difficult for life to exist.”

“A resonant sextuplet of sub-Neptunes transiting the bright star HD 110067” by R. Luque et al. is published in Nature today. DOI 10.1038/s41586-023-06692-3

Source: University of Warwick

You can offer your link to a page which is relevant to the topic of this post.

#Analysis#architecture#Astronomy news#coma#Coma Berenices#Composition#data#Discoveries#ears#earth#ESA#European Space Agency#Evolution#exoplanet#Exoplanets#Featured Space news#form#Future#it#James Webb Space Telescope#jwst#life#Light#Link#Music#NASA#nature#One#orbit#Other

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a real 2006 post!

An example post

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Aliquam nisi lorem, pulvinar id, commodo feugiat, vehicula et, mauris. Aliquam mattis porta urna. Maecenas dui neque, rhoncus sed, vehicula vitae, auctor at, nisi. Aenean id massa ut lacus molestie porta. Curabitur sit amet quam id libero suscipit venenatis.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.

Consectetuer adipiscing elit.

Nam at tortor quis ipsum tempor aliquet.

Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Suspendisse sed ligula. Sed volutpat odio non turpis gravida luctus. Praesent elit pede, iaculis facilisis, vehicula mattis, tempus non, arcu.

Donec placerat mauris commodo dolor. Nulla tincidunt. Nulla vitae augue.

Suspendisse ac pede. Cras tincidunt pretium felis. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Pellentesque porttitor mi id felis. Maecenas nec augue. Praesent a quam pretium leo congue accumsan.

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

Flying Toward a Twenty-First Century Aesthetics of Technomagic Girlhood

by Ravynn K. Stringfield

What is Technomagic Girlhood?

When I began thinking, reading and writing about Black girl superheroes in my dissertation, I found I wanted a way to explore how characters like Riri Williams as Ironheart and Lunella Lafayette as Moon Girl were both performing fantastic feats while defining and creating their Black girlhood with the scientific, technological, and digital tools available to them. Their oft favorite feat? Flight. This list of characters includes but is in no way limited to: Shuri from Black Panther lore, Karen Beecher as Bumblebee, Lunella Lafayette as Moon Girl, and Max from Batman Beyond, the animated television show which ran on the Kids’ WB from 1999 to 2001. There are arguments to made for extending the category to include characters like Marvel Comics’ Misty Knight or even young Diana (Dee) Freeman from HBO Max’s Lovecraft Country, a speculative horror show adapted as a continuation of the 2016 Matt Ruff novel of the same name. In entering a conversation around Black superheroines that scholars like Sheena Howard, Deborah Whaley and Grace D. Gipson have nourished, technomagic girlhood became the term I used, as I was fascinated by the way innovative digital practices and self-making become intertwined for Black girls in superhero stories where our current reality and its technologies were recognizable, but where these girls could manipulate technology to give themselves the ability to literally (and metaphorically) fly.

The idea of technomagic girlhood draws energy from a number of related terms, primary among them being Afrofuturism, the artistic/aesthetic movement and critical framework around the relationship of folks of the African diaspora to the future, technology, and questions of liberation.1 Technomagic girlhood sits underneath the large Afrofuturistic umbrella, though it takes as its large focal point the fantasy genre, magic, the unexplained, whereas much of the strongest Afrofuturistic theorizing prioritizes science fiction as a genre. Work is being done amongst scholars all over to push the boundaries of what constitutes Afrofuturism, and what is in conversation with it.

Also related is Moya Bailey’s term, digital alchemy, which she uses in Misogynoir Transformed to refer to “the ways that women of color, Black women, and Black nonbinary, agender, and gender-variant folks in particular transform everyday digital media into valuable social justice media that recode the failed scripts that negatively impact their lives” (24). Hashtags under the work of Black women, Black queer folks and Black gender expansive folks become entire movements, with “alchemy” implying a chemistry. The chemistry of it all denotes a type of a work, rather than the social justice media appearing as if by will alone, and not backed by the labor of Black women and femmes. I prefer technomagic rather than alchemy because magic connotes, for some a discipline, but contains a joy of use as well. Bailey continues: “Digital alchemy shifts our attention from the negative impact stereotypes in digital culture to the redefinition of representations Black women are creating that provide another way of viewing their worlds” (24). There is a joy in learning to manipulate science, technology and the digital to your own ends for experiments in redefinition and self-making in technomagic girlhood.

For this playful turn, I draw from digital ethnomusicologist Kyra D. Gaunt’s work on embodied play and Black girlhood. I also use “magic” because it locates me more clearly in a legacy of the Black speculative, the Black fantastic, longer traditions of Black girls in magic—and accounts more clearly for how it is possible for these girls to fly. But to fly does not always mean “magic” is afoot. Flight is a condition of reality in texts such as Virginia Hamilton’s retelling of African American folk tales, The People Could Fly (1985), in which Africans take flight back home, and Toni Morrison’s critically acclaimed novel, Song of Solomon (1977), in which Pilate takes to the air. The “techno” prefix is inspired in part by film scholar Anna Everett’s work on Black technophilia and draws us more toward a legacy of Black participation in technology and the digital.

As in #BlackGirlMagic, a commonplace example of technomagic girlhood practice to me, the magic and the fantastic are deeply rooted in reality. This hashtag originates with CaShawn Thompson, who in an interview with journalist and author Feminista Jones says: “I was the first person to use Black Girl Magic or Black Girls Are Magic in the realm of uplifting Black women. Not so much about our aesthetic but jut who we are.” Our magic, Thompson argues, is simply the truth; it was true of her everyday life and how she experienced the world. There is nothing speculative about it, and simply and uniquely of Black girlhood. In many ways, Thompson’s understanding of Black Girl Magic is in conversation with how I understand technomagic girlhood and the potential of what it could be.

I specifically came to use “technomagic” when writing about Marvel Comics’ teenage superhero Riri Williams, also known as Ironheart. The young Chicagoan was able to create her own version of Tony Stark’s Iron Man suit, making her supergenius hypervisible on a large scale, but which she uses locally to help her community. Afrofuturism was the term that I had used for a long time in my work on her, but when we are first introduced to Riri in Eve L. Ewing and Luciano Vecchio’s run, this Black girl, in her tech suit by which she has engineered herself the ability to fly, her face turned skyward, reveling in joy and legacy as seen below…something else occurring. Something that needed to center Riri’s Black girlhood, her experimental and creative self-making through technology, and the joy of impossibility now made tangible…2

Technomagic girlhood is in part a response to some of the questions that André Brock, Jr. asks in Distributed Blackness about whether or not his work on technology and the internet is Afrofuturistic: what about the digital present? Afrofuturism, Brock argues, “is rightly understood as a cultural theory about Black folks’ relationship to technology, but its futurist perspective lends it a utopian stance that doesn’t do much to advance our understanding of what Black folk are doing now” (15). In considering the “now” in possibilities of Black technophilia, technomagic was where I had space to spread out and play as Riri does, as many of the contemporary Black girls do, informed deeply by the legacies and lineages that have come before.

Cover Girls

I choose to examine here Riri Williams as the catalyst for my interest in the topic, along with DC Comics’ Natasha Irons. In what follows, I address these characters’ relationship to technomagic, as seen in the covers for the collected edition of Ironheart: Meant to Fly (Marvel, 2020) and Action Comics #1054 (DC Comics, 2023) that exemplify a few core characteristics of a visual aesthetics of technomagic girlhood and work in tandem.

Technomagic describes a particular quality of contemporary Black girlhood, expansively defined. While this idea most certainly can be applied to other groups of people, I use it as a way of understanding the relationship Black girls in superhero media and other fantasy narratives have to science, technology and digital media, to creativity and joy, and to self-making. By Black girlhood, I often think of how Aria S. Halliday and the authors of the Black Girlhood Studies Collection interrogate the ways in which society tends to conflate Black girlhood and Black womanhood, in both seemingly innocuous and explicitly dangerous ways. Black girls’ joy practices are central to education scholar Ruth Nicole Brown’s work and are resonant here when viewing Riri in Ironheart #1, skyward facing, heart open and Natasha’s focused joy on the cover shown below.

To remember that Black girlhood can be expansive, it is important to incorporate writers who consider girlhood to be a state of mind and being, rather than exclusively an age range. Digital ethnomusicologist Kyra D. Gaunt, for example, asks readers to engage questions of girlhood that include women who might begin their intimate stories to each other with a resonant, “Giiiirl” (p. 2). And Moya Bailey urges readers to consider a wider breadth of possible people who might be brought in by widening what we consider womanhood in her book Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance—in particular, she argues that more than cisgendered heterosexual Black women are harmed by misogynoir (p. 18-22). This is relevant for Natasha (above right), who is canonically a lesbian in the comics, and whose cover brings to mind the colors of the bisexual flag: pink, purple and blue.

After the primary condition of Black girlhood is established, there are secondary conditions that are present in an aesthetics of technomagic girlhood. These include elements of:

impossibility, whether feats or conditions;

creativity, ingenuity, or innovation, often expressed as a practice of the girl in question;

technology, science, or digital media;

self-making or alter-ego creation; and

unbridled joy.

The magic emerges from the clear masterful manipulation of most of these elements in a playful fashion, often for heroic ends, though regularly for their own enjoyment as well.

When we look at these two covers together, we can see elements from many of these categories. On Riri’s cover (by Amy Reeder for Ironheart #43), we see a young Black girl who has presumably engineered herself the ability to fly—impossibility—but who, in this instance, is now falling. Riri falls downward and, judging by the surprise on her face, it appears that the Ironheart suit she has created for herself has fallen apart. It calls to mind the image of the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus, though Riri is both: she is both the famed inventor and also the child who maybe has flown too close to the sun. Riri’s relationship to this myth calls to mind the ingenuity and technology inherent to technomagic girlhood. But the image is juxtaposed with the title phrase “meant to fly”—so, perhaps it is that Riri’s suit is coming to her, not away from her, to save her, to enable her flight, because that impossible feat is what she deserves, and she knows it is hers. She created the impossible and trusts in her own ability—self-making. Notably, in issue #1, Riri can find who she is within the suit, and within a larger legacy not just of superheroics, but of Black women who made her possible. This is both self-making and joy.

DC Comics’ Black girl science genius, Natasha Irons, has a longer history than Riri Williams. Where Riri’s origins date back to the Invincible Iron Man run in 2016 (Vol. 3 #7) written by Brian Michael Bendis and illustrated by Mike Deodato, Natasha Irons was introduced as Dr. John Henry Irons’ precocious niece in Steel #1 (February 1994), written by Jon Bogdanove and Louise Simonson, with art by Chris Batista and Rich Faber. While Irons earns his claim to fame by filling in for Superman, going on to becoming a hero in his own right, over time Natasha develops an aptitude for science as she hangs around her uncle, eventually proving adept at working on Irons’ suit and going on to develop her own. Natasha’s heroism in her own right has only deepened with time. With a new Steelworks run beginning in the summer of 2023, there have been opportunities for Natasha fans to get excited. Most recently, Action Comics #1054 had a variant cover (1:25) by Milestone Initiative artist Yasmín Flores Montañez featuring a solo Natasha in a similar vein to the iconic Riri “Meant to Fly” cover (shown above).4

On this cover, Natasha more clearly appears to be attracting the pieces of her suit to her as she leans over, possibly suspended in air—similar to some iconic scenes from the Marvel Cinematic Universe Iron Man films—anchored by a neon pink background, with a touch of blue, guiding viewer to think more critically about our gendered assumptions regarding technology and science. There’s a look of satisfaction on her face—this is where she is meant to be. She clearly wears the crest of the House of El—Superman’s iconic “S”—as a symbol of hope, though perhaps this will mean something different for Natasha in the issues to come. Natasha’s relationship to this technology, her ability to manipulate it, will inevitability lead to some creative self-making in relationship to this iconic symbol and who she is within in—and without it.

Optimally, technomagic girlhood does not prioritize a capitalistic notion of the lone Black girl science genius. It is not simply “Black Girls Code” for a means to an end. There must be a fantastic joy to it, enabling the Black girl in question to just be, to simply exist, to feel confident in exploring her sense of self, to experiment in self-making. It is not the entering into science and technology spaces to perpetuate capitalistic ideas of productivity or advancement, but for joy and exploration of the self. Therefore, those who care about the well-being of Black girls—all children—must work toward communal needs being met.

In order for this to be meaningful, it needs to be communal, or in relation to others, as it is portrayed in Eve L. Ewing’s twelve-issue Riri Williams: Ironheart run (2018-2019). The idea of the lone Black girl genius feeds into harmful stereotypes related to the magical Negro; instead, intelligence can, and should be, nurtured in community. In Ewing’s Ironheart, Riri’s mother is a loving and watchful presence. Xavier King is Riri’s friend in the series, not just a teammate as many of the other supers she encounters in other runs are. Xavier cares about Riri as a person, with no real investment in what she can offer him. Those who participate in technomagic girlhood are still, after all, girls—children—and still need to love and be loved.

Ewing’s Ironheart gives Riri something she hasn’t had until that point: space to be. We should be working towards these girls’ ability to just be. The ability to create and play in these spaces is contingent on safety. Though Black girl will continue to create and play in spite of oppressive systems, it does not mean these systems as constructed are just. What will it mean for technomagic girlhood to not just be reactive, but to be generative?5 What will it mean for technomagic girlhood to embrace Afrofuturism in so far as it connects to questions of abolition, which devalues the role of policing and commits to a politics of care, as we seek to imagine new and better worlds for Black people, especially children?6 By this I mean: when safety and care are prioritized, what new worlds might our Black girls imagine with their newfound access to digital tools?

Conclusion

With technology, science, and digital media as the backdrop of our era, Black girls who engage in technomagic are increasingly enabled. They are the girls in fantasy stories who may not be gifted with an inexplicable gift for controlling the weather or who can speak to animals, but who have a technophilia akin to magic. They make their ordinary lives extraordinary with their ability to manipulate and build their sense of self in the process. Here, I’ve examined technomagic in superhero narratives, but the principles can and likely will apply across different types of speculative media where Black girls have unique relationships to science, technology and digital media. In particular, these girls are often seen more widely in comic stories adapted for screen: most folks met Riri Williams for the first time on screen in Wakanda Forever (dir. Ryan Coogler, 2022), the sequel film to Black Panther (dir. Ryan Coogler, 2018).

While the general connotation of this term slants towards positivity, as does a related popular phrase like Black Girl Magic, or the hashtagged version: #BlackGirlMagic, it’s worth approaching it with a touch of skepticism and several doses of care. Technomagic, while it does align us with the idea of the Black girl science genius, can also perpetuate the trope of the solitary genius, an idea which Ironheart writer, Eve L. Ewing, problematizes in a 2021 interview with Catapult: “…If that [the trope of the Black girl STEM superhero] becomes the only mode through which we see Black girls, that’s also a problem… I love Ironheart, I love Riri, but Shuri and Riri and Moon Girl are all science geniuses, you know? How does that reinforce certain limited notions about what Black intelligence or Black genius has to look like? How does that play into capitalist-driven conversation about Black girls in coding or Black girls’ participation in science fields?”

To Ewing’s inquiry and to Bailey’s assertions that digital alchemy helps us think about the possible ways Black women are redefining and rethinking about themselves, technomagic girlhood might offer one potential answer. Where we are able to keep joy practices, build and form community together, and experiment in self-making, we protect the essence of technomagic girlhood.7

Notes

1 The term “Afrofuturism” was originally coined in the 1994 roundtable essay “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose” by cultural critic Mark Dery in Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture. It is noted in the essay that Afrofuturism, both as an aesthetic and as a critical framework, has a much longer history, including origins that are often thought of as musical, thinking about the contributions of experimental musicians such as Sun Ra.

2 In this panel, Ewing invokes the legacy of Maya Angelou's poem “Still I Rise” (1978). The entire stanza reads:

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear I rise Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear I rise Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise I rise I rise.

3 Notably for this essay, Reeder is also known for her artwork on Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur.

4 Milestone Media was an African American centric superhero comics publishing company founded in 1993 by Dwayne McDuffie, Denys Cowan, Michael Davis and Derek T. Dingle. DC Comics is currently relaunching Milestone and reintroducing its characters by bringing in a class of artists and writers specifically dedicated to the mission of Milestone. Flores Montañez is part of the Milestone Initiative’s inaugural class.

5 This question is in the spirit of Moya Bailey, whose work and distinction between generative and defensive alchemy as one which is creative for the community and one which is responsive to hatred. It is my hope that technomagic girlhood is framed similar to a generative digital alchemy.

6 I think here of the necessary and timely work of abolitionist organizers and writers Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba in their new book Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care (2023).

7 Gratitude: Many thanks to early readers of this piece for offering kind words and useful insights: Vanessa Anyanso, Shira Greer, Dr. Autumn A. Griffin, Dr. Jordan Henley, Grace B. McGowan, Kristen Reynolds and Dr. Justin Wigard. Conversations with KàLyn Banks Coghill and Dr. Francesca Lyn were also invaluable. Though they are not cited here, the scholarship of education scholars Drs. Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and S. R. Tolliver remain deeply influential to how I think and write. I would like to thank Dr. Shawn Gilmore for his careful editorial eye.

Works Cited

Bailey, Moya. Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance. New York University Press (2021).

Bogdanove, Jon and Louise Simonson. Steel #1. DC Comics (1994).

Brock, André. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. New York University Press, (2020).

Everett, Anna. “On Cyberfeminism and Cyberwomanism: High-Tech Mediations of Feminism’s Discontents.” Signs (Vol. 30, No. 1).

Ewing, Eve L. & Luciano Vecchio. Riri Williams: Ironheart #1-12. Marvel Comics (2018-2019).

Ewing, Eve L. & Luciano Vecchio. Riri Williams: Ironheart: Meant to Fly. Marvel Comics (2020).

Gaunt, Kyra D. The Games Black Girls Play: Learning the Ropes from Double Dutch to Hip-Hop. New York University Press (2006).

Halliday, Aria S. ed. The Black Girlhood Studies Collection. Women’s Press, CSP (2019).

Jones, Feminista. “For CaShwawn Thompson, Black Girl Magic Was Always the Truth,” Beacon Broadside (2019). https://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2019/02/for-cashawn-thompson-black-girl-magic-was-always-the-truth.html

Montañez, Yasmín Flores. Action Comics #1054, 1:25 Variant Cover. DC Comics (2023).

Stringfield, Ravynn. “How Eve L. Ewing Makes Her Stories Fly,” Catapult Magazine, May 19, 2021. https://catapult.co/dont-write-alone/stories/interview-with-dr-eve-ewing-by-ravynn-stringfield

#Ravynn K. Stringfield#feature#comics#Ironheart (comic-book series)#Action Comics (comic-book series)#Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)#film

1 note

·

View note

Photo

PORTO ROCHA

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

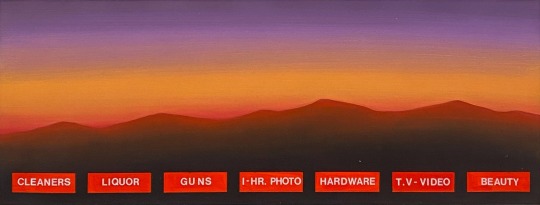

(vía Another America 50 by Phillip Toledano)

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of my favorites by Paul Lehr, used as a 1971 cover to "Earth Abides," by George R. Stewart. It's also in my upcoming art book!

1K notes

·

View notes

Quote

もともとは10年ほど前にTumblrにすごくハマっていて。いろんな人をフォローしたらかっこいい写真や色が洪水のように出てきて、もう自分で絵を描かなくて良いじゃん、ってなったんです。それで何年も画像を集めていって、そこで集まった色のイメージやモチーフ、レンズの距離感など画面構成を抽象化して、いまの感覚にアウトプットしています。画像の持つ情報量というものが作品の影響になっていますね。

映画『きみの色』山田尚子監督×はくいきしろい対談。嫉���し合うふたりが語る、色と光の表現|Tokyo Art Beat

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

What We Know (So Far) About CSS Reading Order

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/what-we-know-so-far-about-css-reading-order/

What We Know (So Far) About CSS Reading Order

The reading-flow and reading-order proposed CSS properties are designed to specify the source order of HTML elements in the DOM tree, or in simpler terms, how accessibility tools deduce the order of elements. You’d use them to make the focus order of focusable elements match the visual order, as outlined in the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.2).

To get a better idea, let’s just dive in!

(Oh, and make sure that you’re using Chrome 137 or higher.)

reading-flow

reading-flow determines the source order of HTML elements in a flex, grid, or block layout. Again, this is basically to help accessibility tools provide the correct focus order to users.

The default value is normal (so, reading-flow: normal). Other valid values include:

flex-visual

flex-flow

grid-rows

grid-columns

grid-order

source-order

Let’s start with the flex-visual value. Imagine a flex row with five links. Assuming that the reading direction is left-to-right (by the way, you can change the reading direction with the direction CSS property), that’d look something like this:

Now, if we apply flex-direction: row-reverse, the links are displayed 5-4-3-2-1. The problem though is that the focus order still starts from 1 (tab through them!), which is visually wrong for somebody that reads left-to-right.

But if we also apply reading-flow: flex-visual, the focus order also becomes 5-4-3-2-1, matching the visual order (which is an accessibility requirement!):

<div> <a>1</a> <a>2</a> <a>3</a> <a>4</a> <a>5</a> </div>

div display: flex; flex-direction: row-reverse; reading-flow: flex-visual;

To apply the default flex behavior, reading-flow: flex-flow is what you’re looking for. This is very akin to reading-flow: normal, except that the container remains a reading flow container, which is needed for reading-order (we’ll dive into this in a bit).

For now, let’s take a look at the grid-y values. In the grid below, the grid items are all jumbled up, and so the focus order is all over the place.

We can fix this in two ways. One way is that reading-flow: grid-rows will, as you’d expect, establish a row-by-row focus order:

<div> <a>1</a> <a>2</a> <a>3</a> <a>4</a> <a>5</a> <a>6</a> <a>7</a> <a>8</a> <a>9</a> <a>10</a> <a>11</a> <a>12</a> </div>

div display: grid; grid-template-columns: repeat(4, 1fr); grid-auto-rows: 100px; reading-flow: grid-rows; a:nth-child(2) grid-row: 2 / 4; grid-column: 3; a:nth-child(5) grid-row: 1 / 3; grid-column: 1 / 3;

Or, reading-flow: grid-columns will establish a column-by-column focus order:

reading-flow: grid-order will give us the default grid behavior (i.e., the jumbled up version). This is also very akin to reading-flow: normal (except that, again, the container remains a reading flow container, which is needed for reading-order).

There’s also reading-flow: source-order, which is for flex, grid, and block containers. It basically turns containers into reading flow containers, enabling us to use reading-order. To be frank, unless I’m missing something, this appears to make the flex-flow and grid-order values redundant?

reading-order

reading-order sort of does the same thing as reading-flow. The difference is that reading-order is for specific flex or grid items, or even elements in a simple block container. It works the same way as the order property, although I suppose we could also compare it to tabindex.

Note: To use reading-order, the container must have the reading-flow property set to anything other than normal.

I’ll demonstrate both reading-order and order at the same time. In the example below, we have another flex container where each flex item has the order property set to a different random number, making the order of the flex items random. Now, we’ve already established that we can use reading-flow to determine focus order regardless of visual order, but in the example below we’re using reading-order instead (in the exact same way as order):

div display: flex; reading-flow: source-order; /* Anything but normal */ /* Features at the end because of the higher values */ a:nth-child(1) /* Visual order */ order: 567; /* Focus order */ reading-order: 567; a:nth-child(2) order: 456; reading-order: 456; a:nth-child(3) order: 345; reading-order: 345; a:nth-child(4) order: 234; reading-order: 234; /* Features at the beginning because of the lower values */ a:nth-child(5) order: -123; reading-order: -123;

Yes, those are some rather odd numbers. I’ve done this to illustrate how the numbers don’t represent the position (e.g., order: 3 or reading-order: 3 doesn’t make it third in the order). Instead, elements with lower numbers are more towards the beginning of the order and elements with higher numbers are more towards the end. The default value is 0. Elements with the same value will be ordered by source order.

In practical terms? Consider the following example:

div display: flex; reading-flow: source-order; a:nth-child(1) order: 1; reading-order: 1; a:nth-child(5) order: -1; reading-order: -1;

Of the five flex items, the first one is the one with order: -1 because it has the lowest order value. The last one is the one with order: 1 because it has the highest order value. The ones with no declaration default to having order: 0 and are thus ordered in source order, but otherwise fit in-between the order: -1 and order: 1 flex items. And it’s the same concept for reading-order, which in the example above mirrors order.

However, when reversing the direction of flex items, keep in mind that order and reading-order work a little differently. For example, reading-order: -1 would, as expected, and pull a flex item to the beginning of the focus order. Meanwhile, order: -1 would pull it to the end of the visual order because the visual order is reversed (so we’d need to use order: 1 instead, even if that doesn’t seem right!):

div display: flex; flex-direction: row-reverse; reading-flow: source-order; a:nth-child(5) /* Because of row-reverse, this actually makes it first */ order: 1; /* However, this behavior doesn’t apply to reading-order */ reading-order: -1;

reading-order overrides reading-flow. If we, for example, apply reading-flow: flex-visual, reading-flow: grid-rows, or reading-flow: grid-columns (basically, any declaration that does in fact change the reading flow), reading-order overrides it. We could say that reading-order is applied after reading-flow.

What if I don’t want to use flexbox or grid layout?

Well, that obviously rules out all of the flex-y and grid-y reading-flow values; however, you can still set reading-flow: source-order on a block element and then manipulate the focus order with reading-order (as we did above).

How does this relate to the tabindex HTML attribute?

They’re not equivalent. Negative tabindex values make targets unfocusable and values other than 0 and -1 aren’t recommended, whereas a reading-order declaration can use any number as it’s only contextual to the reading flow container that contains it.

For the sake of being complete though, I did test reading-order and tabindex together and reading-order appeared to override tabindex.

Going forward, I’d only use tabindex (specifically, tabindex="-1") to prevent certain targets from being focusable (the disabled attribute will be more appropriate for some targets though), and then reading-order for everything else.

Closing thoughts

Being able to define reading order is useful, or at least it means that the order property can finally be used as intended. Up until now (or rather when all web browsers support reading-flow and reading-order, because they only work in Chrome 137+ at the moment), order hasn’t been useful because we haven’t been able to make the focus order match the visual order.

#Accessibility#Articles#Behavior#change#chrome#columns#container#Containers#content#CSS#CSS-Properties#direction#display#Features#focus#grid#grid-template-columns#guidelines#how#HTML#html elements#it#layout#links#mind#Moment#nth-child#One#Other#prevent

0 notes

Photo

No one wants to be here and no one wants to leave, Dave Smith (because)

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

don’t call me whiny baby if you didn’t care about my whiny baby feelings already, which you didn’t care about!!! shocker!!!

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PORTO ROCHA

773 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beautiful photo of the Princess of Wales departing Westminster Abbey after attending the Commonwealth Day Service. --

#catherine elizabeth#princess catherine#princess of wales#princess catherine of wales#catherine the princess of wales#william arthur philip louis#prince william#prince of wales#prince william of wales#william the prince of wales#prince and princess of wales#william and catherine#kensington palace#british royal family

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

GENERAL MEMES: Vampire/Immortal Themed 🩸🦇🌹

↳ Please feel free to tweak them.

Themes: violence, death, blood, murder, depression/negative thoughts

SYMBOLS: ↳ Use “↪”to reverse the characters where applicable!

🦇 - To catch my muse transforming into a bat 🌞 - To warn my muse about/see my muse in the sunlight. 🩸 - To witness my muse drinking blood from a bag. 🐇 - To witness To catch my muse drinking blood from an animal. 🧔🏽 - To witness To catch my muse drinking blood from a human. 🦌 - For our muses hunt together for the first time. 🏃🏿♀️ - To see my muse using super speed. 🏋🏼♂️ - To see my muse using their super strength. 🧛🏻♂️ - To confront my muse about being a vampire. 🌕 - For my muse to lament missing the sun. ⏰ - For my muse to tell yours about a story from their long, immortal life. 🤛🏽 - To offer my muse your wrist to drink from. 👩🏿 - For my muse to reminisce about a long lost love. 👩🏽🤝👩🏽 - For your muse to look exactly like my muse's lost love. 👄 - For my muse to bite yours. 👀 - For my muse to glamour/compel yours. 🧄 - To try and sneakily feed my muse garlic to test if they're a vampire. 🔗 - To try and apprehend my muse with silver chains. 🔪 - To try and attack my muse with a wooden stake. 👤 - To notice that my muse doesn't have a reflection. 🌹 - For my muse to turn yours into a vampire. 🌚 - For my muse and yours to spend time together during the night. 🧛🏼♀️ - For my muse to tell yours about their maker/sire.

SENTENCES:

"I've been alive for a long time [ name ], I can handle myself." "I'm over a thousand years old, you can't stop me!" "Lots of windows in this place, not exactly the greatest place for a vampire." "Do you really drink human blood? Don't you feel guilty?" "Vampires are predators, [ name ] hunting is just part of our nature, you can't change that." "You just killed that person! You're a monster!" "Tomorrow at dawn, you'll meet the sun [ name ]." "Can you make me like you?" "Do you really want to live forever?" "You say you want to live forever, [ name ], but forever is a long time, longer than you can imagine." "What was it like to live through [ historic event / time period ]?" "Did people really dress like that when you were young?" "What were you like when you were human?" "We’re vampires, [ name ], we have no soul to save, and I don’t care." "How many people have you killed? You can tell me, I can handle it." "Did you meet [ historic figure ]?" "Everyone dies in the end, what does it matter if I... speed it along." "Every time we feed that person is someone's mother, brother, sister, husband. You better start getting used to that if you want to survive this life." "[ she is / he is / they are ] the strongest vampire anyone has heard of, no one knows how to stop them, and if you try you're going to get yourselves killed." "Vampire hunters are everywhere in this city, you need to watch your back." "Humans will never understand the bond a vampire has with [ his / her / their ] maker, it's a bond like no other." "Here, have this ring, it will protect you from the sunlight." "I get you're an immortal creature of the night and all that, but do you have to be such a downer about it?" "In my [ centuries / decades / millennia ] of living, do you really think no one has tried to kill me before?" "Vampires aren't weakened by garlic, that's a myth." "I used to be a lot worse than I was now, [ name ], I've had time to mellow, to become used to what I am. I'm ashamed of the monster I was." "The worst part of living forever is watching everyone you love die, while you stay frozen, still, constant." "I've lived so long I don't feel anything any more." "Are there more people like you? How many?" "Life has never been fair, [ name ], why would start being fair now you're immortal?" "You want to be young forever? Knock yourself out, I just hope you understand what you're giving up." "You never told me who turned you into a vampire. Who were they? Why did they do it?" "I could spend an eternity with you and never get bored." "Do you really sleep in coffins?" "There are worse things for a vampire than death, of that I can assure you [ name ]." "You need to feed, it's been days. You can drink from me, I can tell you're hungry." "The process of becoming a vampire is risky, [ name ], you could die, and I don't know if I could forgive myself for killing you." "I'm a vampire, I can hold a grudge for a long time, so believe me when I say I will never forgive this. Never." "You were human once! How can you have no empathy?" "You don't have to kill to be a vampire, but what would be the fun in that." "You can spend your first years of immortality doing whatever you want to whoever you want, but when you come back to your senses, it'll hit you harder than anything you've felt before." "One day, [ name ], everything you've done is going to catch up to you, and you're never going to forgive yourself." "Stop kidding yourself, [ name ], you're a vampire, a killer, a predator. You might as well embrace it now because you can't keep this up forever." "You can't [ compel / glamour ] me, I have something to protect me." "When you've lived as long as me, there's not much more in life you can do." "You want me to turn you? You don't know what you're asking me to do." "You really have to stop hissing like that, it's getting on my nerves." "I'm going to drive this stake through your heart, [ name ], and I'm going to enjoy it."

#ask meme#symbol meme#roleplay sentence meme#sentence starter meme#rp sentence prompts#vampire ask meme#ask box#ask memes#vampires#tw : blood#tw: violence#tw: death#tw: depression#tw: vampires#tw: murder

172 notes

·

View notes

Quote

よく「発明は1人でできる。製品化には10人かかる。量産化には100人かかる」とも言われますが、実際に、私はネオジム磁石を1人で発明しました。製品化、量産化については住友特殊金属の仲間たちと一緒に、短期間のうちに成功させました。82年に発明し、83年から生産が始まったのですから、非常に早いです。そしてネオジム磁石は、ハードディスクのVCM(ボイスコイルモーター)の部品などの電子機器を主な用途として大歓迎を受け、生産量も年々倍増して、2000年には世界で1万トンを超えました。

世界最強「ネオジム磁石はこうして見つけた」(佐川眞人 氏 / インターメタリックス株式会社 代表取締役社長) | Science Portal - 科学技術の最新情報サイト「サイエンスポータル」

81 notes

·

View notes