#GDP deflator

Text

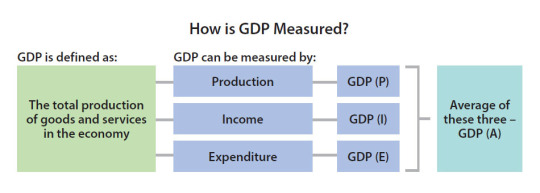

National Income

To estimate the total economic activity in a nation or region, a number of metrics are utilised, including the gross domestic product, gross national product, net national income, and adjusted national income.

National Income is the final output of all new goods and services a country produced in one year.

To estimate the total economic activity in a nation or region, a number of metrics are utilised, including the gross domestic product, gross national product, net national income, and adjusted national income.

The term “national income accounting” refers to a group of procedures and guidelines that…

View On WordPress

#Central Statistical Organisation#GDP#GDP Deflator#GDP Of A Country#GNP#Gross Domestic Product#Gross National Product#Methods To Calculate GDP#Methods To Calculate national Income#National Income#National Sample Survey Organisation#NDP#Net Domestic Product#Net National Product#NNP#Nominal GDP#Per Capita Income

0 notes

Text

I’ll conclude by returning to a theme I brought up earlier: the shrunken time horizon of the US ruling class. The current motley crew looks nothing like the set who planned the post-World War II order. They emerged from—or recruits were assimilated to—an ethnically and socially homogenous WASP aristocracy who felt themselves above quotidian distractions and rank commercial temptations. Of course, it was all in the interest of long-term accumulation under US guidance, but it was all successfully planned and executed (at least until things started slipping some in the 1970s). Now with the US in a long process of imperial decline, our planning elite seems fragmented and lost. You have Republicans criticizing Biden for not having shot down the Chinese balloon quickly enough, and Democrats acting as if it was an act of heroism. Our rulers don’t act like they have any good idea about coping with the rise of China, except with bellicose and one hopes ineffectual gestures, because God knows, we don’t want bellicose gestures to lead to an actual war.

And we have a capitalist class that has apparently given up on the future—incapable of dealing with the climate crisis, a truly dire threat, but also consuming capital rather than investing it. Net investment—net, that is, of depreciation—by both business and government—has been falling relative to GDP for decades. The vast flow of free money and 0% interest rates from the Federal Reserve has been channeled into an impressive set of bubbles: the most extended valuations of stocks in US history, crypto, unicorns, housing. It used to be normal to have one particular asset lead the way in a speculative orgy, whether it was stocks in the late 1990s or housing in the following decade. Now we’ve got multiple and serial bubbles that have only been partly deflated by the Fed’s tightening moves of the last year. And Wall Street is dearly hoping the central bank will reverse those moves in a few months and resume the cheap money flow. The bond vigilantes of the 1980s and 1990s, always on the lookout for an inflation that needs to be crushed, have largely disappeared.

I’ll give the last word to Etienne Balibar, who has diagnosed the affliction precisely. “We realize now that our ruling class is no longer a bourgeoisie in the historical sense of the word. It does not have a project of intellectual hegemony nor an artistic point of honor. It needs (or so it thinks) only cost-benefit analyses, “cognitive” educational programs, and committees of experts. That is why, with the help of the pandemic and the internet revolution, the same ruling class is preparing the demise of the social sciences, humanities and even the theoretical sciences.” The bourgeoisie no longer has any civilizational project, national or otherwise. Live for today, and if the water rises, they can just move inland. Or to their underground bunkers.

post-nationalism

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cereseto and Waitzkin analysed 10 quantitative indicators of human wellbeing for the year 1980, including life expectancy and the adult literacy rate. They found that at any given level of GDP per capita, socialist states tend to have superior outcomes to capitalist states. Similarly, in his detailed study of health indicators around the world, Navarro concluded that socialist countries generally had superior population health standards. Navarro noted that socialist China had much higher life expectancy than capitalist India, while Cuba outperformed the rest of Latin America. ‘This international survey shows that at least in the realm of underdevelopment, where hunger and malnutrition are part of the daily reality, socialism rather than capitalism is the form of organisation of production and distribution of goods and services that better responds to the immediate socioeconomic needs of the majority of these populations’.

Capitalist reforms and extreme poverty in China: unprecedented progress or income deflation?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

China’s recently announced GDP target for 2024 remains unchanged from last year, at 5 percent. But even if the country hits that number, its economic problems run deep. In January, China published economic data for the last quarter of 2023 which put its annual GDP growth rate at 5.2 percent, beating the government target. Yet, to put things in perspective, China’s real GDP growth rate from 2011 to 2019 averaged 7.3 percent while 2001-10 saw average growth of 10.5 percent.

After the figures dipped in 2020 to 2.2 percent owing to COVID-19, expectations for post-pandemic recovery were high. This was rooted in the assumption that China lifting its dynamic zero-COVID policy in January 2023 would unlock pent-up demand in the economy, which remained suppressed during the two-year-long lockdown. But that hasn’t happened. Some observers even doubt the recently released GDP data’s authenticity and suspect the numbers are far below the official figures.

But even if the figures are accurate, the wider trends of the Chinese economy suggest a worrying state of affairs. To begin with, this was the first time since 2010 that China’s real GDP growth rate exceeded its nominal GDP growth rate (4.8 percent). The nominal growth rate is calculated on the previous year’s numbers without accounting for inflation. Discounting inflation is necessary to remove any distortion arising from a mere increase in the prices of goods and services. Thus, the real GDP figure is calculated after adjusting for inflation to reflect the increase in output of goods and services. This is also the number economists and governments refer to when stating GDP growth numbers.

Usually, the nominal growth rate should be higher than the real growth rate. But in a deflationary year, the real growth rate can give a distorted picture, because deflation or negative inflation amplifies the real numbers. Thus, the fact that China’s real GDP number exceeded its nominal number indicates that Beijing’s gross value of output in real terms was amplified thanks to negative inflation, i.e. a general decrease in the prices of goods and services. If not for deflation, China’s real GDP growth in 2023 would have been even lower and would have certainly missed the national target of 5 percent.

The news on China’s gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) isn’t encouraging either. The term refers to the acquisition of fixed assets such as land and machines or equipment intended for production of goods and services. It is one of the four components of GDP (besides exports, household consumption, and government expenditure) and a measure of investment in the economy. For decades, China relied on a high GFCF rate to power its economy, but it has witnessed a sustained decline under President Xi Jinping’s leadership. For reference, the GFCF growth rate in the last 9 years (2014-22) averaged 6.7 percent as compared to 13 percent in the 21 years before that (1994-2014). It hit over 10 percent only on four occasions in the last nine years, once in 2021 thanks only to a significantly low base due to the pandemic year.

The bulk of this investment came from the real estate sector, which constituted a quarter of China’s total investments in fixed assets. Between 1994 and 2014, the sector witnessed a year-on-year growth rate of around 30 percent. But in the last eight years, the property sector has witnessed average growth of only 4.2 percent—and shrank by 10 percent from 2021 to 2022.

In part, the drop in investment can be attributed to the conscious decision of the central leadership under Xi to deflate the property bubble, which had become unsustainable, and reallocate and redirect capital from speculative to more productive forces. The decelerating impact this decision has had on China’s GDP has forced leadership to reverse its policies to some degree, trying to prop up the bubble. But the forced deflation is now proving too resistant to change, as is evident from the 2023 numbers that suggest the real estate sector shrunk by 9.6 percent.

But that’s not the only reason for the drop in investment. In the past year, China’s economy has witnessed an increasing securitization of its development. On numerous occasions, including at the 20th Party Congress in 2022 and the Two Sessions in 2023, Xi has underlined that the idea of development cannot be isolated from that of security. In a meeting of the Chinese Communist Party’s National Security Commission last year, Xi reiterated the need to “push for a deep integration of development and security.”

Consequently, in the first half of 2023, Chinese authorities carried out a series of crackdowns on foreign and domestic consultancy companies that offered consultancy services to help overseas businesses navigate China’s challenging regulatory environment. The infamous instances included raids on U.S. companies Mintz in March and Bain & Company in April. In May, Shanghai-based consultancy Capvison saw its offices raided for stealing state secrets and transferring sensitive information to its foreign clients. Weeks later, China’s Cyberspace Administration announced that U.S. chip giant Micron failed to obtain security clearance for its products.

This need to put security over the economy further became apparent in China’s revision of its counter-espionage law, which came into effect in July 2023. The updated law not only broadens and dilutes the definition of espionage but also confers wide-ranging powers on local authorities to seize data and electronic equipment on account of suspicion. China’s new developmental security approach, which manifested in its crackdown on foreign and domestic consultancies alike, has spooked private investors since then.

The government has issued repeated assurances to both domestic and foreign investors to improve the business environment and spur investment. However, investment in fixed assets by private holding companies has been declining since 2018. It briefly rebounded in 2021, only to drop again in 2022. The data for 2023, although not yet updated, is unlikely to pick up.

In contrast, investment by the state has gone up to compensate for the decline in private investment. But this can’t be a substitute in the long run for two reasons. First, rising government debt at a time when private investment is declining can lead to crowding out of capital, thereby shrinking the resource pool for private businesses. And second, the government has already stretched itself as its debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 55.9 percent in 2023. Given the mounting debt situation, there exists very little room for the government to even sustain, let alone expand, its current expenditure.

The data on China’s net exports suggests their contribution to GDP, although steadily picking up since recording a low in 2018, is unlikely to return to the glory years of 2001-14. While China will continue to be a leading export nation, the contribution of net exports to its growth rate might not be high. Poor external demand also means that export-oriented investments will see a decline, thereby pulling the overall investment rates further down albeit with a lag.

China’s strategy in the wake of this situation has been to seek to boost domestic consumption and household spending. Yet for domestic consumption to emerge as a new engine of growth requires not only sustaining its previous momentum but also increasing its share as a percentage of GDP to compensate for the loss of growth due to falling investment (in property and export-oriented sectors) rate.

However, a look at China’s household consumption expenditure as a percentage of GDP suggests that it has remained significantly low compared to other consumption-driven advanced and emerging economies. For instance, in both the United States and India, household consumption makes up more than 55 percent of GDP. In contrast, China’s household consumption has historically hovered around 40 percent—and dropped to 37 percent in 2022.

To add to the misery, the growth of China’s household consumption expenditure is also declining in the wake of a pandemic that left the public deeply insecure about their financial future. For ten years (2010-19), growth remained stable at around 10 percent before the pandemic forced the household consumption growth rate to drop to zero in 2020. After recording an uptick in 2021from that low, the growth rate dropped again in 2022. The negative difference between the nominal and real GDP in 2023, indicative of deflation, further confirmed the sluggish demand in the economy.

Thus, domestic consumption seems unlikely to be able to fuel China’s growth. The rising unemployment rate, declining consumer confidence, aging population, and rising dependence ratio will further burden any attempt to raise China’s consumption.

These trends may be baked in the near to medium term. China will not see a return to the high growth rates witnessed in 1980-2010 and will instead stabilize near 4 percent. This will likely derail China’s plan to transition from a middle- to a high-income country and certainly dent Xi’s dream of transforming China into an advanced socialist country. The much-dreaded fear of the “middle-income trap” is real for China.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are experiencing ever increasing cost of goods and services.

If we want to exchange products for money, there needs to be sufficient money to correspond to each and every product.

In one country, there were 100 products and 100 units of money at a specific time.

After 10 years, the total number of products in the country has increased to 150.

How much money would the country have issued by then?

If more money was issued than the increase in products, we have to pay more money for each product. (Inflation)

If money was less issued than the increase in products, we could pay less money for each product. (Deflation)

How is it in the real world?

According to the World Bank, the growth of money in the world has outpaced the growth of global products (GDP).

We have been living in a world where we have to pay more and more money for each product!

------------------

🔖(Global money) / (Global GDP) - World Bank

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FM.LBL.BMNY.GD.ZS

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Belgium’s already substantial budget deficit is set to continue widening and will likely exceed 5% of GDP by 2026, the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) warns in its autumn forecast.

To reverse the trend, the country needs to save €2 billion annually – a total of €10 billion – over the next five years – NBB Governor Pierre Wunsch stressed.

Although the real interest rate on Belgium’s debt remains low, the primary deficit remains high, he noted.

Only Slovakia's budget outlook seems worse

The public debt ratio is projected to be much the same as in 2023, at 105.2% of GDP in 2024, while primary public spending heads towards stabilisation at 53% of GDP.

With this budgetary outlook, Belgium ranks second from the last in the European Union, better only than Slovakia.

Related News

'A clear challenge': Fiscal watchdog warns Belgian debt is becoming unsustainable

Belgium's budget deficit set to be second largest in Europe, claims EU

'Serious savings still required': Brussels suffers drastic budget cut

Nevertheless, Belgium’s GDP is expected to grow by 1.3% in 2024, at a quarterly pace of around 0.3%. Consumer spending is expected to sustain growth next year, backed by strong purchasing power, while public spending is also set to increase, a common occurrence during election periods.

Inflation projected to rise to 4% next year

However, foreign trade will remain sluggish, influenced by weak competitiveness.

After a fall in inflation in 2023, including a spell of deflation in Autumn, inflation is projected to climb again in 2024, nearing 4%. The end of the government’s energy support measures is the main reason cited for this rise by the National Bank.

The bank also pointed out that the indexation of wages will continue to add to labour costs in the private sector, although less so than in 2023.

Bank's projections more optimistic than government's, says Budget Minister

The hourly labour cost in Belgium, compared to neighbouring countries, increased by 4 percentage points in 2022 and 2023, mainly due to the automatic indexation system. Forecasts suggest this wage disparity will be eliminated by 2026, as wages in Germany, the Netherlands and France rise faster than in Belgium in the coming years.

Secretary of State for the Budget, Alexia Bertrand (Open VLD), expressed satisfaction with the National Bank’s predictions. She believes the federal government has taken the right political decisions, although deficit and debt levels need to be reduced.

Bertrand stressed that the bank’s economic growth outlook was more optimistic than the government’s own predictions, with the budget deficit for 2023 and 2024 lower than government estimates.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japan's nominal gross domestic product will top 600 trillion yen ($4.2 trillion) in fiscal 2024 for the first time, a target set by the government about a decade ago, a Cabinet Office estimate showed Thursday, expecting income growth to outpace inflation.After higher import costs of energy and raw materials boosted prices of everyday goods, inflation will ease to 2.5 percent in fiscal 2024 from 3.0 percent this year. Income growth per capita, meanwhile, will accelerate to 3.8 percent from 2.4 percent, helped by the government's planned temporary tax cut, according to the office.The release of the forecasts came as the government plans to formalize a draft budget for fiscal 2024 from April on Friday.Japan's nominal GDP, at 566 trillion yen in fiscal 2022, is projected to grow to 597 trillion yen in the current fiscal year, with a further increase to 615 trillion yen in fiscal 2024, according to the office.The government has unveiled plans to provide 70,000 yen handouts to low-income families and a 40,000 yen tax cut per person as part of inflation relief measures. It will also offer tax incentives to firms raising wages.Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has been stepping up calls for firms to support the upward trajectory of wages, fearing that Japan will let the chance slip to "completely break with deflation" that has plagued the nation for years.Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda has struck a cautious tone over the prospect of attaining the central bank's 2 percent inflation target "stably and sustainably," saying he wants to see more data to ensure a virtuous cycle of wage and price hikes is in place.Japan's economy registered its first contraction in four quarters in the July-September quarter due largely to sluggish domestic demand, but economists expect it to recover in the current quarter to December.The Cabinet Office said the world's third-largest economy will receive support from strength in domestic demand, such as private consumption and capital spending, in fiscal 2024.GDP, the total value of goods and services produced, is forecast to expand 3.0 percent in nominal terms and 1.3 percent in inflation-adjusted terms, slower than 5.5 percent and 1.6 percent for fiscal 2023, respectively.In 2015, the government set a goal of attaining 600 trillion yen in nominal GDP by around fiscal 2020, as part of the "Abenomics" economy-boosting program that entailed fiscal stimulus and powerful monetary easing.Market expectations are heightening that the BOJ will shift toward policy normalization by ending its negative rate and yield curve control, both introduced in 2016 to support economic growth and attain stable inflation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

GDP, General Price Level and Related,, General Price Level – Measurement of CPI, WPI and GDP deflator Case of Inflation in India

Oh bhai ye bahut saara hai

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

China shows more signs of disinflation as its GDP Deflator declines

We start the economic week with one of the wonders of the modern world, which is how China can produce its Gross Domestic Product or GDP numbers only 17 days after the end of the particular quarter. By contrast my own country the UK has switched to a slower production of quarterly numbers in an attempt to improve accuracy.Even Bloomberg is questioning things these days.

Chinese social media check…

View On WordPress

#business#China#Disinflation#economy#Finance#GDP#GDP Deflator#Industrial Production#Property#Retail Sales#Youth Unemployment

0 notes

Text

George Dfouni: Are we experiencing an Inflation or recession in the United States of America? Allow me to explain the difference and you can decide for yourself.

In a conversation with the US based Hotelier, George Dfouni digs deep into the difference between Inflation and recession. He states: “Inflation and recession are two critical aspects of economic performance that significantly influence the lives of individuals and the broader economic environment in the United States. These phenomena often coexist, and understanding their causes, effects, and interplay is crucial for effective economic policy and personal financial planning.”

Inflation in the United States

Inflation is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services rises, eroding purchasing power. Several factors contribute to inflation, including demand-pull inflation, where demand for goods and services exceeds supply; cost-push inflation, where the costs of production increase, leading to higher prices; and built-in inflation, which stems from adaptive expectations where businesses and workers expect and incorporate higher prices into their future pricing and wage-setting behavior.

In recent years, the United States has experienced fluctuating inflation rates, influenced by various macroeconomic factors. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted supply chains and labor markets, leading to a mismatch between supply and demand. This resulted in noticeable inflationary pressures as the economy began to recover. Additionally, expansive fiscal and monetary policies aimed at mitigating the pandemic's economic impact, such as stimulus payments and low-interest rates, contributed to increased consumer spending and further demand-pull inflation.

The Federal Reserve (Fed), the central bank of the United States, plays a crucial role in managing inflation. It typically targets a 2% inflation rate as a sign of a healthy economy. To combat rising inflation, the Fed may increase

interest rates, making borrowing more expensive and thereby cooling off economic activity. Conversely, to spur economic activity during low inflation or deflation, the Fed may lower interest rates to encourage borrowing and investment.

Recession in the United States

A recession is typically defined as a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months. It is often identified by a fall in GDP for two consecutive quarters, although other factors like unemployment rates, industrial production, and consumer spending are also critical indicators.

Recessions can be triggered by various factors, including high inflation, which erodes consumer purchasing power and reduces spending. They can also result from external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to widespread business closures, job losses, and a sharp contraction in economic activity. Additionally, financial crises, such as the 2008 financial meltdown, caused by risky financial products and a housing bubble burst, can plunge economies into recession.

During a recession, businesses typically experience lower sales, leading to cost-cutting measures, including layoffs. This, in turn, increases unemployment, which further reduces consumer spending and can deepen the recession. Governments and central banks often intervene with fiscal and monetary policies to mitigate the impacts. These may include stimulus packages to boost spending and investment, and monetary policies like lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing.

George Dfouni, went on further and explains the interplay between inflation and recession.

The relationship between inflation and recession is complex and often paradoxical. For instance, while high inflation can lead to a recession by

eroding purchasing power and increasing costs for businesses, deflation or very low inflation can also be problematic. It can lead to reduced consumer spending as people anticipate further price declines, which can exacerbate a recession.

A significant challenge is the "stagflation" scenario, where high inflation and high unemployment coexist, as experienced in the 1970s in the U.S. This situation poses a dilemma for policymakers since measures to control inflation, such as raising interest rates, can worsen unemployment, while measures to reduce unemployment can exacerbate inflation.

In conclusion, George Dfouni adds: “Understanding the dynamics of inflation and recession is crucial for navigating the economic landscape. Policymakers, businesses, and individuals must stay vigilant and adaptable to the shifting economic conditions. By comprehensively analyzing these phenomena, effective strategies can be developed to foster a stable and prosperous economy. The interplay between inflation and recession requires a delicate balance of policies to ensure sustainable economic growth and stability, highlighting the complexity and interdependence of modern economic systems”

0 notes

Text

Crisis Economics, Free Flow of Commerce1. Oil, housing, transportation, and communications must be addressed to where the consumer benefits and not the market profits. Supply is better than demand with free trade and choices for the consumer.

2. Credit crisis. If the government gets on us about public debt, why don't they set the example?

3. Insurance must be covered like banks so they do not fail, insured insurance covered by the government.

4. Tech bubbles are dangerous. To much hype and price testing.

5. Living beyond needs. Domestic spending goes further than foreign policy spending. Diplomacy spends less than war, war as the last resort

6. Markets are regulated by supply and demand and consumer, leave it alone, no subsidies

7. Crisis will come and go, such to with economic bubbles.

8. Gold is hyped too much, it's like oil, but both will see their future dwindle with time.

9. Inflation is when we try to control the flow of a product or services, over-regulation, union,s nationalistic greed for the nation-state, over-taxed corporations and people, embargoes, sanctions, wars, Deflation is great for the consumer, creates sales, etc. Interest rates should react upon inflation and deflation after the fact.

10. BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) vs WTO, USA, and the EU. Can't we all just get along? Let the market free flow and give the global consumer what they want. We do not need a war, nationalisms, isolationism, extremism, fanaticism, price gauging, subsidies a free-trading world, consumer-driven without government interference to protect industries and services,

11, Bring back subprime mortgages. Why? Because when there are more houses on the market than homeless people, Houston! We have a problem. We can bail out a bank, but we can't bail out the common citizen.

12. Moral hazards. What are morals? Societal regulation for a majority who are self-righteous. Let society change through freedom and social flow and the economics of it will set the morals.

13. Global markets should be free flow, unregulated, non manipulated.

14, Taxes should be reduced, government spending should be not spent on wasteful wars, but on people, social security, maintaining a person from falling through the cracks to where they are homeless, food for those who cannot eat. Societal preventative maintenance.

15. The G20 should work together with the UN to establish the stability of the world and not just the nation-state.

16. I think the Chinese have the right idea of mixing capitalism with socialism.numbers in GDP do not lie!

0 notes

Text

For the last three decades, the Chinese economy has resembled an impressionist painting: beautiful from afar, but a jumbled mess up close. China’s economic model has centered around investment-led growth made possible by the supply of cheap capital extracted through domestic financial repression, using a combination of policies—such as interest rate caps, capital controls, and restrictions on credit allocation directions and financial market entry—to channel capital into state-prioritized sectors. While this model has contributed to China’s rapid rise, it has also led to the entrenchment of structural issues that began to emerge well before President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012. Instead of taking the chance for reform, though, Xi’s policies have only worsened these issues.

China faces three major structural challenges that expose it to the risk of economic stagnation akin to Japan’s “lost decades”: Escalating debt coincides with decelerating growth, sluggish household consumption lags overextended supply, and adverse demographic trends have blunted China’s edge in cheap but skilled young labor, which amplifies social welfare costs and causes housing market demand to dwindle. The inevitable reckoning of China’s structural challenges has been accelerated since Xi’s ascendence.

The fuse on this economic time bomb is steadily shortening. In recent months, critical economic indicators—from industrial profits and exports to home sales—have all recorded double-digit percentage declines. In July, while consumer prices rose globally, they fell in China, raising concerns that deflation could worsen the difficulties faced by heavily indebted Chinese companies. A convergence of idiosyncratic factors now threatens to ignite a crisis in the property and construction sector, which makes up nearly 30 percent of Chinese GDP. China Evergrande’s recently filed for bankruptcy. Coupled with the impending default of Country Garden, another major property developer, after missed bond payments this month, it has deepened the already profound sense of uncertainty and fear among the business community.

This economic uncertainty is further heightened by the Chinese Communist Party’s ever-shifting targets of anti-corruption and anti-espionage campaigns. Health care is the latest sector to fall under the gaze of authorities, even as the effects of previous campaigns against tech, private education, gaming, and finance still linger. In the background, the friction between China and the United States continues largely unabated. Private conversations among Chinese citizens, particularly the young, reveal an undercurrent of pessimism and unease. Among the contributing factors is the looming specter of military conflict with the West regarding the future of Taiwan. China’s one-child generation would shoulder the weight if such a conflict were to happen, an existential threat of unparalleled proportions.

Milton Friedman was partially correct when he famously stated that “[i]nflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” In China, the manifestation of economic deflation symptoms—even transitory—has been shaped by Xi’s departure from the reform and opening up policy and the return of expansive political, ideological, and geoeconomic aspirations reminiscent of the Mao Zedong era. We might dub the resulting phenomenon “Xi-flation,” deflation with Chinese characteristics. The cumulative policy shocks of the last five years have exacerbated, rather than quelled, the structural challenges that have been dragging—but not crashing—China’s growth.

The posture of China’s teetering-but-not-tumbling growth trajectory has long called for careful structural reform. The goal should be to squeeze out the property market bubble without bursting it, to alleviate income inequality without stifling entrepreneurship, and to foster fair competition without hurting productivity. The success of these reforms hinges on a calibrated policy orchestration. Instead, Xi’s policy has produced grandiose political rhetoric, such as “common prosperity” or “shared human destiny,” mixed with clumsy and misguided enforcement.

Economically, Xi has been a bull in a china shop. His economic policies have often shifted focus but always emphasize the party’s overarching control across nearly all dimensions of China’s economic and financial activity. Since 2017, foreign companies operating in China have organized lectures for employees to study the role of the party and Xi speeches. As of October 2022, 1,029 out of the 1,526 of the mainland-listed companies (more than two-thirds) whose shares can be traded by international investors in Hong Kong acknowledge “Xi Thought” in their corporate constitutions and have articles of association that formalize the role of an in-house party unit.

In fairness, Xi did not create China’s structural woes. However, the reform and opening up policy suffered a quiet, unheralded death as Chinese policy thinkers attempted to compensate for the absence of prudent economic strategy under Xi by ceaselessly leaping from one grand idea to the next under the banner of national rejuvenation.

For example, since December 2016, the phrase “houses are for living, not for speculation” has become the principle to curb the property sector. In 2017, the “thousand-year project” Xiong’an New Area was launched as a city of the future. In 2019, “establishing a new national system for innovation” entered the lexicon for state-led science and technology innovation. Since 2020, “common prosperity” has become the mantra behind which to launch antimonopoly and antitrust probes into China’s tech sector. And since November last year, when Xi suddenly reversed China’s zero-COVID policy, the new catchphrase has shifted to “consumption promotion.”

Xi-flationary policies have exacerbated China’s latent structural problems and rung up a steep tab. For instance, Xi’s regulatory crackdown on China’s leading tech companies wiped out more than $1 trillion in market value, a figure comparable to the GDP of the Netherlands. The zero-COVID policy incurred costs of at least 352 billion yuan ($51.6 billion) for Chinese provinces, almost twice the GDP of Iceland ($27.84 billion in 2022).

The financial cost of these policy missteps is not their worst aspect. The most profound cost of Xi-flation so far is an unprecedented run on confidence in the Chinese economy from within and without. Beijing’s old economic playbook has run out of pages when it comes to tackling this crisis. China cannot export its way out of today’s economic challenges or stimulate its way toward a full recovery without also addressing the underlying political cause. As China moves up global supply chains, foreign companies are increasingly looking for alternative countries to sources for inputs and locate production to ensure they do not fall on the wrong side of any lines drawn as part of Western policymakers’ drive to “de-risk” their reliance on China.

This is, in part, a belated reaction to the willingness of China under Xi to use economic coercion. Researchers from the International Cyber Policy Centre found that between 2020 and 2022, China resorted to economic coercion in 73 cases across 19 jurisdictions, a marked increase compared to China under Xi’s predecessors.

China’s waning comparative advantage is a long-term structural problem, but political and geopolitical factors drive the current run on confidence. As Xi continues to consolidate power, the once lucrative China premium will be further discounted due to the growing regulatory and geopolitical uncertainty. Chinese technocrats cannot fully address this run on confidence using only their limited economic toolbox, such as the People’s Bank of China’s use of the so-called precision-guided structural monetary tools to selectively provide credit for state-preferred sectors.

Xi’s global assertiveness has caused negative spillback for China’s economy. Amid China’s fraying ties with the West and multinationals hastening to diversify their supply chains, ordinary Chinese households are left to deal with mounting anxiety. They are economically less secure as a consequence of Xi’s zero-COVID policy, and they are increasingly concerned that geopolitical forces beyond their control have limited their individual futures. Xi’s commitment to reunite Taiwan with the mainland, by force if necessary, has created the perception among some in China that conflict is inevitable—the same as in the United States. This loss of confidence aggregates across hundreds of millions of Chinese households, underpinning an economic condition that James Kynge has characterized as a “psycho-political funk.”

An essential factor behind China’s economic success during the reform and opening up period was what economist John Maynard Keynes termed “animal spirits”—those emotional and psychological drivers that push people to spend, invest, and embrace risk. For decades, China not only benefited from the inflow of foreign direct investment and technology from the West, but also enjoyed a steady tailwind from the optimistic outlook of Western business leaders eager to capitalize on the globalization trend. When Western companies briefly reconsidered their involvement with China in the aftermath of the Tiananmen protests, Deng Xiaoping rescued the situation by embarking on his influential southern tour in 1992. During his tour, he the world of the party’s commitment to economic reform, stating, “It is fine to have no new ideas … as long as we do not do things to make people think we have changed the policy of reform and opening up.”

However, Xi’s policies have undone much of Deng’s legacy and upended China’s prior economic success formula. China’s appeal as a destination for both tourism and business has dimmed, and a growing number of the country’s elite look beyond the border for their future. If this trend continues, China may fall into the dreaded middle-income trap or face even graver risks such as a financial crisis. A financial crisis in China would have far greater consequences than any other previous emerging market crisis. The size of China’s economy and its level of integration dwarf that of South Korea in the late 1990s, when it was at the epicenter of the East Asian financial crisis.

The West has a genuine interest in preventing the economic downfall of China. Washington and Brussels must closely coordinate to ensure their de-risking policies send a clear message to Beijing on its intended goals and limits by drawing a bright red line around sectors with potential military dual use while clarifying in which circumstances cooperation is still encouraged. Otherwise, the West risks legitimizing Xi’s claims that economic containment is to blame for China’s economic woes, and that further self-sufficiency is the only antidote. The West must be careful to communicate that its policies are designed to avoid the global alienation of 1.4 billion Chinese people.

When the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meets this November in San Francisco, the sister city of Shanghai, China’s economy may be on considerably less sure footing than the United States for the first time in decades. That may prove to be an opportune time for both countries to repair the world’s most consequential bilateral relationship.

The Biden administration can take a page from the playbook of Otto von Bismarck: “Diplomacy is the art of building ladders to allow people to climb down gracefully.” A good start would be for the United States to lend a ladder this fall and help China clean out its gutters—if a Xi-led China is capable of accepting the help.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating article by Nicholas Lardy, perhaps the most esteemed Western scholar specializing on China's economy: foreignaffairs.com/united-states/…

Contrary to The Economist's claim that we've reached "peak China", he argues that "China is still rising", that the West "underestimates the resilience of its economy" and that China's "nominal GDP [will] resume converging toward that of the United States this year and is likely to surpass it in about a decade".

He debunks several misconceptions:

First misconception: "the Chinese economy’s progress in converging with the size of the U.S. economy has stalled"

No he says, the truth is that whilst "from 2021 to 2023 China’s GDP fell from 76% of U.S. GDP to 67%", it is also true that "by 2023, China’s GDP was 20% bigger than it had been in 2019 [...] while the United States’ was only 8% bigger."

The reason for this "apparent paradox" can be explained by two factors:

1) "Over the last few years, inflation has been lower in China than it has been in the United States" meaning that for instance last year "China’s nominal GDP grew by 4.6%, less than the 5.2% that its GDP grew in real terms. In contrast, because of high inflation, U.S. nominal GDP in 2023 grew by 6.3%, while real GDP grew by only 2.5%." And, you'll have guessed it, those GDP comparisons that show China stopped catching up with the U.S. compare nominal GDP values.

2) "The U.S. Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by over five percentage points since March 2022, from 0.25 percent to 5.5 percent, making dollar-denominated assets more attractive to global investors and boosting the value of the dollar". As a result "the growing gap between Chinese and U.S. interest rates [...] ultimately depress[ed] the value of the renminbi vis-à-vis the dollar by 10%. Converting a smaller nominal GDP to dollars at a weakened exchange rate results in a decline in the value of China’s GDP when measured in dollars relative to U.S. GDP."

He says this is all "transitory": "[China's] nominal GDP measured in U.S. dollars will almost certainly resume converging toward that of the United States this year and is likely to surpass it in about a decade".

Second misconception: "household income, spending, and consumer confidence in China is weak"

He says that's simply wrong as the data shows the opposite: "Last year, real per capita income rose by 6%, more than double the growth rate in 2022, when the country was in lockdown, and per capita consumption climbed by 9%. If consumer confidence were weak, households would curtail consumption, building up their savings instead. But Chinese households did just the opposite last year: consumption grew more than income, which is possible only if households reduced the share of their income going to savings."

Third misconception: "Price deflation has become entrenched in China, putting the country on course toward recession"

He says that whilst "consumer prices rose only 0.2% last year, which gave rise to the fear that households would reduce consumption in anticipation of still lower prices—thereby reducing demand and slowing growth", "this has not happened because core consumer prices (meaning those for goods and services besides food and energy) actually increased by 0.7%". As we saw before, households did not in fact reduce consumption.

Fourth misconception: there's "a collapse in property investment"

He says that whilst is it true that "the number of new buildings on which construction has begun was [in 2023] half of what it was in 2021", this masks the fact that "in that same two-year period, real estate investment fell by only 20%, as developers allocated a greater share of such outlays to completing housing projects they had started in earlier years." So there's a downturn in real estate for sure (-20%), but no "collapse".

Fifth and last misconception: "Chinese entrepreneurs are discouraged and moving their money out of the country"

He says a large part of this is due to the downturn in real estate, as "when real estate is excluded", private investment actually "rose by almost 10% in 2023"!

He also writes that even though there are some some individual cases of prominent Chinese entrepreneurs leaving the country, this shouldn't mask the fact that "more than 30 million private companies remain and continue to invest". Moreover, and this is a stunning statistic, "the number of family businesses, which are not officially classified as companies, expanded by 23 million in 2023, reaching a total of 124 million enterprises" (meaning a growth of almost 23% in 2023 alone!).

unpaywalled link ➡️ https://archive.ph/DUlCj

0 notes

Text

Haters, GDP deflators, real GDP time series of success, etc.

1 note

·

View note

Text

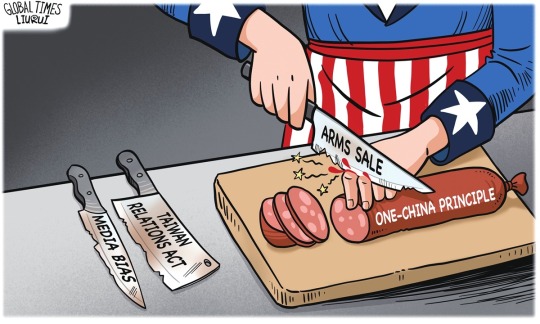

Inadvertent Self-harm

— Liu Rui | January 21, 2024

Illustration: Liu Rui/Global Times

American Pundits Predicting China’s Economic Collapse Doomed To Fail

— Wen Sheng | January 21, 2024

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

After the National Bureau of Statistics recently reported major economic indicators, including yearly GDP growth, industrial output, consumer and factory prices, domestic retail and import and export volume, housing investment and demographic changes for 2023, some Western media pundits seem to be delving into narratives to prove that China's economy is in dire straits, "stumbling" or even "collapsing."

The New York Times published an essay on Thursday entitled "China's Economy Is in Serious Trouble", authored by American economist Paul Krugman. In the article, he opined that Chinese economy "seems to be stumbling," with the announced official data showing that "China is experiencing Japan-style deflation," and "there's reason to believe that China is entering an era of stagnation and disappointment."

It is not the first time Krugman has decried the Chinese economy. In last August, he penned another opinion piece under the sensational headline "How Scary is China's Crisis?" in which he claimed that China "seems to be teetering on the edge of a crisis that looks a lot like what the rest of the world went through in 2008," pointing to the last global financial crisis triggered by the US' chaotic subprime debacle.

But the economic crisis that Western pundits like Krugman wrote or hoped for isn't happening in China at all. They have been spinning a story on a hypothetical crisis to engulf and tear down the world's emerging economic giant, and others are gloating over it. They will be disappointed again.

Actually, the strength of China's unique social system and the resilience of the Chinese economy, tested by the 1997 and 2008 financial crises and other events like the Biden administration's repulsive trade and technology war, should not be underestimated and denigrated by pundits. By all metrics, it is truly a great feat in human history to build a country as large as China from scratch in 1980 to its present size of nearly $18 trillion, or more in PPP (purchasing power parity) terms.

Official statistics revealed that the Chinese economy expanded by 5.2 percent in 2023 from the previous year to reach more than $17.5 trillion, as it rebounded from three years of anti-coronavirus control measures. Compared to merely 3.0 percent rise in 2022, the 5.2-percent growth last year is significant and impressive, obviously being one of the highest growths reported by the world's major economies.

As the single biggest engine of global economic growth, all of China's neighbors and trade partners, including those in Latin America, Africa and Europe, have become aware of the business opportunities created by China. With their factories, ranches and ports increasingly intertwined with China's, these partner economies are rapidly thriving. So it can be presumed that one of the untold reasons leading Western pundits to criticize China and its economy is to muddy the waters and plant seeds of doubt among China's major trade and economic partners.

US politicians have attempted to suppress China and hinder its growth by imposing high tariffs, sanctions, and restrictions on tech exports. They have also made attempts at "decoupling," which have been witnessed by the whole world in the past few years. However, those efforts have been unsuccessful. Now, pundits in the US media and academic circles want to support their politicians to go even harder at China, in their desperate hope to frighten away China's business partners and international investors interested in buying Chinese yuan-denominated assets and diversifying their investment portfolios to reduce their holdings of US dollar assets.

In his essay "How Scary is China's Crisis?" Krugman stated that China's government debts were "unsustainable," facing the "Minsky Moment" - meaning an impending implosion of the fiscal crisis. Many months have passed, yet the world hasn't seen a debt crisis in China.

Compared with the US government which added up to $7 trillion to its federal debts since the COVID pandemic to a total of more than $34 trillion, and it is running more than $1 trillion debt each year, China certainly is in a better fiscal shape. China has more than $3.2 trillion in foreign exchange reserve and has a very positive current account balance. Also, Chinese households' bank savings rate is much higher than their American counterparts. Correspondingly, China has more tools and means to accelerate economic stimulus over coming years to ramp up fiscal spending and cut savings rate to ramp up investment and inspire domestic consumption.

Chinese economists believe that the country has more room to maneuver to support government spending on a wide variety of projects and services, including rural infrastructure, urban utilities and amenities, technology innovations, expansion of manufacturing plants as well as improving its sprawling social safety net, including pension coverage for the retired people and better medical care for all newborns and other citizens.

Meanwhile, Chinese companies are rapidly catching up in research and development for new technologies. For example, the country is leading the world in producing clean renewable energies and exporting batteries, electric cars and other higher value-added products. Although China's urban housing sector is undergoing a correction after more than two decades of heated growth, the slowdown could be offset or mitigated by the boom in auto production and new-energy transformation.

As for the allegation that China "is entering an era of stagnation" similar to Japan's "Lost Two Decades," it is a preposterous assumption or Western pundits' wishful thinking about the Chinese economy. Any economist won't consider an economy with a trajectory of more than 5-percent annualized expansion to be falling into "stagnation." China's policymakers have the ability to issue more government bonds by raising the budget deficit ratio to 3.8 or 4 percent of GDP in 2024, which is still dwarfed by the US' 6.3 percent federal budget deficit ratio in 2023, to ratchet up economic activity and consumer prices. The policymakers' only concern is they don't want to leave a heavier burden on future generations.

When all of these factors are considered, there is no reason to be alarmed about China's growth. In comparison to the US, where the cost of living from housing rent to groceries to medication remains high, coupled with political infighting and dysfunction, China has a much more nimble decision-making system and can turn things around efficiently. American pundits, driven by ideology, have been predicting an imminent collapse of the Chinese economy since early this century, but so far, they haven't succeeded.

— The Author is an Editor with the Global Times.

#Global Times#China 🇨🇳#War Criminal United States 🇺🇸#Taiwan 🇹🇼 | Republic of China 🇨🇳#Miscellaneous Cartoons#Liu Rui#American Pundits#Economic Collapse#Prediction#US Lies & Propaganda

0 notes

Text

UK GDP shows us that the Bank of England and OBR owe the public a big apology

So far 2023 has mostly opened with better economic news from the UK and that has continued this morning. We can start with some upwards revisions to economic growth.

UK gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to have increased by 0.1% in Quarter 4 (Oct to Dec) 2022, revised from a first estimate of no growth……This follows a revised fall of 0.1% in Quarter 3 (July to Sept) 2022, previously…

View On WordPress

#Bank of England#business#Construction#CPTTP#economy#Finance#GDP Deflator#house prices#Manufacturing#Nominal GDP#Nominal GDP Targeting#OBR#Office for Budget Responsibility#Production#Services#UK GDP

0 notes