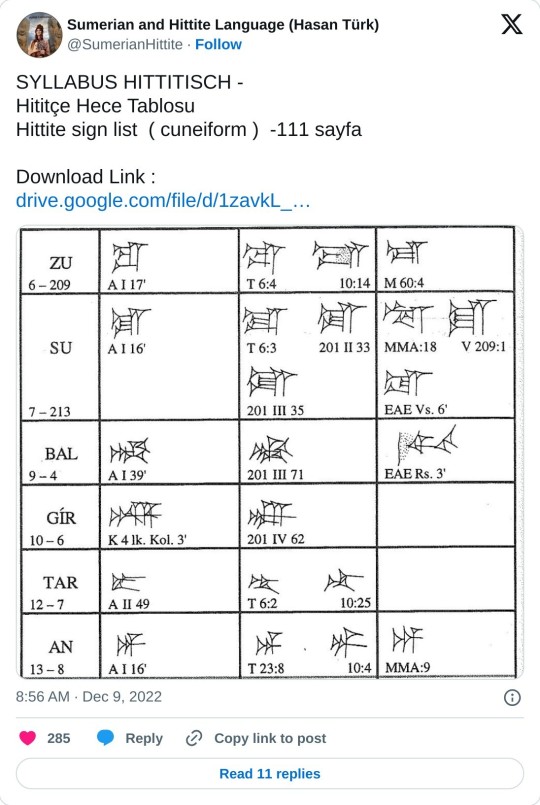

#Hittite Syllable

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Download Link : https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zavkL_xhvVc2dnPOjCThxy3dmMjfUD_y/view?usp=sharing

#Sumerian#Hittite#Language#Hasan Türk#Hittite cuneiform#ancient#Hittite Syllable Table#Hittite Syllable#Sumerianlanguage#Sumerianwriting#Sumeriacuneiform#ancientsumer#ancientsumerans#Babylon#Babylonia#ancientiraq#iraq#cuneiform#Assyriology#العراق#العراقـالعظيم#سومر#السومريين

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

PY Ta 714

.1 to-no , we-a2-re-jo , a-ja-me-no , ku-wa-no , pa-ra-ku-we-qe , ku-ru-so-qe , o-pi-ke-re-mi-ni-ja

.2 a-ja-me-na , ku-ru-so , a-di-ri-ja-pi , se-re-mo-ka-ra-o-re-qe , ku-ru-so ⟦ ⟧ , ku-ru-so-qe , po-ni-ki-pi 1

.3 ku-wa-ni-jo-qe , po-ni-ki-pi 1 ta-ra-nu , a-ja-me-no , ku-wa-no , pa-ra-ku-we-qe , ku-ru-so-qe , ku-ru-sa-pi-qe , ko-no-ni-pi 1

Translation

A throne made of rock-crystal, inlaid with blue glass, emerald, and gold carrying poles,

inlaid with gold figures of men and a gold siren's head and gold palm trees. 1.

and blue glass palm trees. 1. one foot-stool inlaid with blue glass, emerald, and gold, with gold cross bars. 1.

Commentary

to-no - thornos - "throne." This would be θρόνος in Classical Greek. The difference between /-or-/ and /-ρο-/ isn't necessarily surprising and is likely just a result of liquid metathesis - a random sound change. This liquid metathesis in also seen in Cypriot θόρνα. An example of θρόνος not undergoing liquid metathesis in Mycenaean in seen in the word to-ro-no-wo-ko, meaning chair-maker. In to-ro-no, a dummy vowel o is used to separated the consonants t and r. This shows that r is part of the onset of the syllable, rather than part of the coda (in which case it would be omitted from the transcription).

we-a2-re-jo - weharejo - "rock crystal"? The e-jo suffix shows that this is an adjective of material. This could be related to Greek ὕαλος, which means "rock-crystal." This material was commonly found during the Aegean Bronze Age, with a rock-crystal inlay having been found on a Knossos gaming board. However, this would reconstruct as hualeyos, not wehaleyos? Although we cannot directly reconcile it, this appears to be the most sensible option - we-a2-re-jo has to be a material. ὕαλος is not a Greek word and is most likely a loan word. The initial syllable /hwa/ is not a Greek phoneme and so we-a2 may have been a way of conveying both the aspirated component and the labial component.

a-ja-me-no - "inlaid." This appears to be a perfect passive participle aiaimenos. This has no Classical Greek correspondences, but, from context in both this tablet and several others, seems to mean "inlaid." This participle is nominative singular agreeing with to-no.

ku-wa-no - kuwano(i) - "blue glass (paste)." Related to English "cyan." This is a dativeor instrumental singular - the indirect object of a-ja-me-no. Classical Greek κύανος. Possibly from Hittite kuwannan (copper, blue, precious stone).

pa-ra-ku-we-qe - parakuwe(-kwe) - "(and) emerald." pa-ra-ku-we has no Greek relatives. The -we ending makes it clear that this is a u-stem noun in the dative or instrumental. In another tablet, we have the adjective pa-ra-ku-ja as an adjective describing cloth, whilst we also have *56-ra-ku-ja, which may be an attempt to approximate a non-Greek phoneme (/b./). pa-ra-ku-we seems to be related to Akkadian barraqtu, which means emerald. The *b phoneme that is seen in Classical Greek is not of Proto-Indo-European origin and is generally a result of the voiced labiovelar *gw, as seen in *gwou- (qo-u in Mycenaean).

ku-ro-so-qe - khruso(i)-kwe - "gold." Related to Classical Greek χρυσός.

o-pi-ke-re-mi-ni-ja - opikelemnians - "carrying poles?" This is a first declension accusative plural, acting as an accusative of respect. o-pi is equivalent to Classical ἐπί with Ablaut variation. ἀμφικελεμνις means "sedan chair." This may therefore mean "carrying pole" or similar.

a-di-ri-ja-pi - "pictures of men." Instrumental plural -pi. ἀνδριας in Classical Greek means "pictures of men."

se-re-mo-ka-ra-o-re-qe - seiremo-krahore-(kwe) - "(and) a siren's head." seirem- is most likely the equivalent of Classical Greek σείρην, with Mycenaean being prior to the change of word final /m/ > /n/ in Greek. krahore- is the instrumental of kraha (related to the poetic term κάρα - "head").

po-ni-ki-pi - phoinikphi "palm trees." This is largely agreed to mean "palm tree" (Classical Greek φοῖνιξ), but could potentially mean "date" or "phoenix."

ta-ra-nu - thranus - "foot-stool." Related to Homeric θράνυς.

ko-no-ni-pi - "cross-bars?" Feminine instrumental plural. Perhaps related to Classical Greek κανονίς - "cross bar" - but the vowels o not necessarily match up.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hieroglyphics 📜

—

Hieroglyphics is a writing system invented in Egypt around 5000 years ago.

It is the second oldest form of writing, originating a few hundred years after cuneiform, which uses wedge-shaped characters and was devised by the Sumarians of Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians were once thought to have got the idea of writing from the Sumarians, but their system is now generally believed to have emerged independently, although the details of its origins remain mysterious.

Hieroglyphs take the form of pictures, each representing an entire word, syllable, or phoneme (the units of sound from which spoken language is built).

The Ancient Egyptians referred to these scripts as “the gods’ words,” a phrase translated by the Ancient Greeks as “sacred carvings,” which gives us “hieroglyphics.”

Strictly, the word applies only to the writing on Ancient Egyptian monuments.

However, these days, it is used more loosely to describe other, unrelated, picture-based scripts including those employed by the Hittites in Anatolia, the Minoans in Crete and the Maya of Mesoamerica.

Egyptian hieroglyphs are written in rows and columns.

They are read from top to bottom, and either left to right or right to left – with the heads of the human and animal characters pointing toward the start of the line.

The earliest texts remain largely indecipherable, except for names within them, even though many contain hieroglyphs used in later inscriptions.

However, during the 3rd dynasty (between about 2650 and 2575 BC), hieroglyphics became regularised.

From then, it continued with the same 700 or so signs for more than 2000 years.

https://www.newscientist.com/definition/hieroglyphics/

#hieroglyphics#Ancient Egypt#hieroglyphs#sacred words#Egyptian hieroglyphs#writing system#Egyptian language#ancient civilization#culture#history

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Some authors treat A.A as a compound sign with the reading aya (or aja if you prefer), and I think that makes the transliteration a lot cleaner: ma-aya-lu. Giving names to compound signs like this is most common for logograms (ENSI "governor" in a transliteration actually means the three signs PA.TE.SI), but occasionally happens for phonetic signs too!

It is a bit odd for a phonetic sign to represent multiple syllables, but not unheard of. Hittite scribes, for example, wrote the word a-na ("to" in Akkadian) so often that they started to combine the a and the na together, turning them into a single sign with the reading aná:

Hello, I wonder do you still accept asks? Because me and my friends kinda self-taught myself on Akkadian recently and there's passage that kinda... sparked debates among my peers. I can't find the cuneiform but the Akkadian sounds like this :

ü-tu-lu-ma etlütu (gurus) [sa i] - [na ma] -a-a-al mu-si sal-lu

Professional Assyriologist (Andrew George) translated that passage as :

The men were lying down, that were asleep on beds for the night

From the Akkadian dictionary we can identify some words

Utulu : [itulu] lay down

Etlutu (gurus) : Young men

Mu-si : at night

Sal-lu : sleep

Other words are too fragmentary for the admittedly amateur me to decipher, but I can't find any usual word for bed in that passage either "bitu" (bedroom), "erim", "gisnu", "huralbu", "i'lum", "marsu", or any other possible words for bed that you can find on the dictionary, let alone the proof that the word is plural. The closest I can find is, perhaps, that [na ma] there is a fragmentary word for "namallu" which in dictionary means "plank bed", double-sided bed. And also I can't find plural form on that line, so perhaps you can help me? Not necessary about the bed/beds, but more about how will you translate that line?

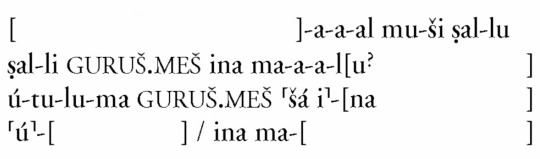

Hi! The fragment you mention is from the SB Epic of Gilgamesh, VI.180. Here is the score for that line (a comparison of various manuscripts):

Although the second line is a little different, we can use it in combination with the other versions to reassemble the likely original line: "ú-tu-lu-ma GURUŠ.MEŠ šá i-na ma-a-a-l mu-ši ṣal-lu." Whenever you see a double "-a-", as in "ma-a-a-l," it's generally transliterating a y/j sound, so it's listed in the dictionary as either "majālu" or "mayālu" (depending on how German your dictionary is!). "Majālu" is a relatively common Akkadian word for a bed or sleeping place. It's rendered in version 1 as "majāl" (no case ending) because "ina" will often occur with the bound (i.e. stripped-down) form of. noun.

So the word-for-word literal translation is "and-they-lay-down, the-young-men, in bed, at-night, sleeping."

Hope that helps, but let me know if you have further questions!

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've been following along with your name translations, and I'm v fascinated, and it's making me wonder: many of these names end up being really long, and even the names you do give as real attested ones are also pretty long. I'm wondering, do you know if nicknames/shorter versions of these names would have been common in everyday use? Would royalty have long complicated names but common people have shorter, simpler names? Would Supiluliuma have a nickname or would people call him that always?

My sweet summer child, if Šuppiluliuma scares you, let me introduce you to Zababa-šuma-iddina and Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur.

All kidding aside, I’m not aware of common people having shorter names than royalty in Hittite society. In fact, many names were shared by people of various classes: there were three kings named Ḫattušili, for example, but also a bunch of dignitaries, scribes and palace workers with the same name. Likewise, Taḫurwaili was the name of a king (albeit a short-lived one), but also of a random gardener. Bear in mind that there were also a lot of shorter names, like Zita, Alli, Šanda or Walwa - the names I’ve been translating are long by virtue of being translations, not because all Hittite names were.

That said, a lot of names were long, and I would be very surprised if people didn’t have shorter versions of them. Like us, the Hittites were once children who couldn’t pronounce their siblings’ names, or changed them around on purpose to tease them. I can easily imagine Šuppiluliuma’s little brother butchering his name as a kid and keeping the nickname as an adult, even once Šuppiluliuma had become king - I mean, how many of us have successful siblings that we still call by a dumb name because, well, they’re our sibling, how else would we address them?

And again, like us, the Hittites had friends and lovers and they gave them pet names. Some of them would’ve been a shortened version of their name, just like so many Benjamins get called Ben, and others would’ve been descriptive, like “singer” or “long nose”. Many simpler names attested in texts may well be nicknames of this type - Walwa, “lion”, might refer to a particularly brave man, or one with thick, light hair.

The problem is that the vast majority of our documentation comes from palace or temple archives, and as a result, most of the texts we have are legal, political, religious, or literary. This means that nicknames are extremely uncommon - if they are even attested at all. After all, you wouldn’t use nicknames while writing an official statement, even if it’s about your beloved wife or your idiot brother. The only shortened name I can think of in the Hittite corpus is Kán-iš for Kantuzili, but given context, it’s more likely to be scribal shorthand rather than an actual nickname.

So while I firmly believe nicknames existed, we have no knowledge (as far as I’m aware) of how they looked. What is important to remember, however, is that just because these parts of Hittite life were preserved doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. As I’ve tried to show many times before, ancient people were just like us - they squabbled with their siblings, laughed so hard they snorted, cried when their pet died, were woken up by their child who wet their bed, had hangovers, stargazed, and all the rest. Šuppiluliuma’s nickname(s) may well remain unknown forever, but I’m almost certain he had one, as so many of us have for millennia.

#final note: name length varies from culture to culture#most modern english names have 2-4 syllables so anything more than that is considered 'long'#and therefore necessitates a nickname#but cultures where names commonly have 4+ syllables will view things differently#that said i still 100% believe the hittites gave each other nicknames#hittite#Hittites#damn i love the hittites

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Kill him, my archer," Apollo whispered, vicious as only a god could be. Triumph and fury dripped from every syllable. "Kill him for your brothers, kill him for my sons."

The inspirations here come from some Mycenaean artifacts for Achilles' armour and shield (upside-down shh I'm not drawing all the shit on it lol but I also wanted to include it while, aside from not wanting to deal with all those details, not wanting to cover Achilles up too much), and Hittite/Luwian ones for Apollo and Paris!

(Specifically, but not all pieces; the Warrior Vase for the shape of the shield, the carving in Karabel pass for the bottom shape of Apollo's tunic, a particular deer rhyton with an etching that contains two gods for inspiration for Apollo's long braid and jewellery.)

Detail shots under the cut!

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

English Wordsmithing Pt. 1: From PIE to Proto-Germanic

Ok, so intro post with the basics of PIE is done. Now we can actually get to making these words! Today, I'm feelin' like I want some good words for clergy/pagan priestly roles since pretty much all native English words for them have been Christianized.

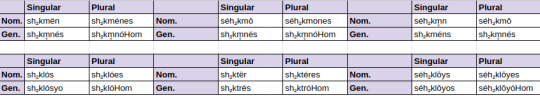

There are a few PIE roots we could select (including *weh₂t-, which yielded Latin "vātēs" for an Oracle, prophetess, or seer, Odinn, and several words in English and other Germanic languages meaning "madness", "excitement", "singing", "rage", etc. It's a fun root, but not what I'm looking for right now. Maybe later.), but for this purpose, I want to explore *seh₂k-, which gave us Latin "sacer", "sanctus" and English "sacred" and English/French "saint". It has meanings of making or being holy, as well as making a pact---which is great! Perfect!

A note on Orthography: since my system can't render ḗ correctly, nor é̄, a long vowel bearing accent will be written as e̋.

Now we need to choose endings. I'm going to focus on endings that derive agent nouns from roots or verbs. The first that springs to mind is *-te̋r, which throws the stem into the ø grade. Because it derives nouns from adjectives, I could actually append this not just to the bare *seh₂k- root, but also the various infix-presents, and the factative and causative forms. Unfortunately, I'm not familiar enough yet with PIE word-formation, so I don't have a good idea of what happens when I need to adjust stress/ablaut on more than one syllable.

Wiktionary also claims that *-lós is also a suffix that derives agent nouns from roots/verbal nouns. Great, add it to the pile.

Lastly, I want to explore is actually three endings connected by ablaut. We have *-mén(s) > *-mën, *-mon(s) > *-mō, and *-mn̥. I'm tempted to think *-mn̥ is the original ending since *-mō is its collective/plural, and that was a common path for new words to get coined in PIE (and it's how we got the feminine gender in Post-Anatolian PIE!) and *-me̋n created in analogy, but I don't have data for that. It should be noted that *-mn̥ is neuter and both *-mō and *-me̋n are masculine. Also technically only *-me̋n and *-mō create agent nouns---but in Proto-Germanic two of the endings collapse together, and by the time we get to Old English, they're all the same ending.

as a bonus, I'm also including *seh₂klōys, which only has descendents in Anatolian languages and meant something like ‘custom, customary behavior, rule, law, requirement; rite, ceremony; privilege, right’, according to Dr. Kloekhorst, in his Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon which is great and I love it.

So, our candidate words are:

*sh₂kme̋n ~*séh₂kmō ~ *séh₂kmn̥

*sh₂klōs

*sh₂kte̋r

*seh₂klōys, for funsies

Now, the forms for the genitive and the plurals were distinct, so I'll be listing these words in tables with these four forms of the word (Nominative Singular, Nominative Plural, Genitive Singular, Genitive Plural). Because the oblique cases merge so fast (to the point where we go from PIE's fulll Nominative-Accusative-Genitive-Vocative-Ablative-Allative-Dative-Locative-Instrumental system to Old English's Nominative-Accusative-Genitive-Dative system that was already just a Nominative-Genitive system except for a few rare forms.) and I'm currently not looking to make new words out of oblique forms, we're good leaving them off.

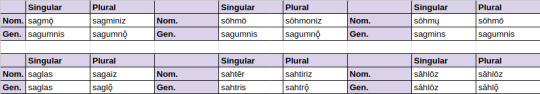

So! our initial tables are:

Image captions coming once I figure out how to trick screanreaders into pronouncing IPA

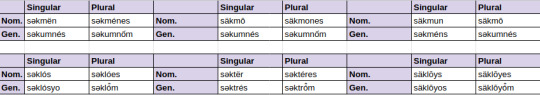

So, for the purposes of this post, I'll be following a roughly chronological order for the sound changes, but if you're following along at home, the chronological summary of sound changes can be found on page 152 of A Linguistic History of English, Volume I: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic by Don Ringe, but it's recommended that you definitely follow along by reading from section 3.2.1.

Now, Immediately, several sound changes are relevant to our words:

Syllabic resonants prepend an epenthic "u"

Word-final bimoric ("long") -ō lengthens to trimoric ("overlong") -ô

Word-initial laryngeals are dropped before consonants, laryngeals that precede a vowel color /e/ and /ē/ and are dropped, laryngeals that follow vowels lengthen them and color /e/ and /ē/ and are dropped, AND because neither Cogwill's nor Osthoff's law apply here, laryngeals between consonants are replaced by epenthic "ǝ"

Giving us:

Once again, this image uncaptioned until I can make a reader read it comprehensibly, I'm so sorry

At this point, the biggest changes we need to handle are Grimm's and Verner's Laws.

Grimm's Law shifts the "voiceless" series of consonants to voiceless fricatives ([ p, t, k ] > [ f, þ, x(orthographic "h") ]), "voiced" obstruents to voiceless obstruents ([ b, d, g ] > [ p, t, k ]), and "voiced-aspirated" obstruents to voiced obstruents (which also had voiced fricative allophones in many positions; [ bʰ, dʰ, gʰ ] > [ b, d, g ]). Now, clusters of obstruents block the shift such that only the first obstruent shifts. Which means for our purposed, only one consonant---the final "k" in the root is affected and nothing else.

Verner's Law and is more complicated. To quote Dr. Ringe in Section 3.2.4: """ After the PIE voiceless stops had become voiceless fricatives by Grimm’s Law, they became voiced by Verner’s Law if they were not word-initial and not adjacent to a voiceless sound and the last preceding syllable nucleus was unaccented; *s was also affected, and became voiced *z under the same conditions """

Also, really only affecting the genitive singular of *-ós: *-ósyo, is apocope, wwhich actually ends up chopped back to *-ós.

So now, at this crossroads we have:

At this point, stress moves to the initial syllable (so I will no longer be marking stress) which strengthens ǝ > a, and then two sequences of changes happen at the same time:

m > n at the end of words, then Vn > V̨ word-final /n/ is lost while nasalizing the preceeding vowel, and then ę̄ > ą̄

unstressed /e/ > /o/ before wC, unstressed /e/ > /i/ everywhere else

after this, the next two big changes happen before the Late contraction of vowels in hiatus wraps everything up:

ji > i, kicking off the general loss of j between vowels except the environments *ijV > *ijV and ǝjV > *jV

After stress moved to the initial syllable the low rounded back vowels unrounded: [ o, ō, ô ] > [ a, ā, â ], then after ę̄ > ą̄ and VjV > VV, the long low vowels re-rounded, regardless of nasalization: [ ā, â ] > [ ō, ô ]

The contraction of vowels in hiatus wraps everything up. For the most part, the contraction meant /o/ and /a/ got lengthened, capping at trimoric length.

So, our words are now in their Final Proto-Germanic state:

It's almost comprehensible to screen readers!

Right?

Well, not quite. Because we have to take into account he morphological changes that were made as native speakers remodeled declensions and shit to suit how they interpreted their language to work.

Here, it's just Nom. sing. "saglas" > "saglaz"

And also the leveling of sag- and merger of -mǫ̂ + -mō endings (with light remodelling.) Now we're ready to head into the next post where we cover the Intermediate stages between Proto-Germanic and Old English, with this set:

Soon, I promise

#linguistics#proto indo european#proto germanic#conlanging#conlang#I still feel like I missed something during the o > a change bc that was more remodelling than expected#Sound changes say -mnes that /m/ is a syllabic resonant and should receive an epenthic /u/ if it doesn't have a vowel against it#yet all the endings have -minis or -miniz

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

*h₂edden cognates in IE and Uralic?

[Epistemic status: I am pretty confident in tying the IE prepositions together, theoretical Uralic connections are extremely speculative bordering on Edo Nyland-tier]

A lot of languages in Indo-European have preverbs or prepositions with a *d in them, though a bit perversely they tend not to show up in the most archaic languages--I don’t think there are any examples in Greek, Tocharian, Indo-Iranian or Anatolian, though I’ve probably overlooked something. Perhaps because this class of preposition mostly shows up in the ‘newer’, more youthfully attested branches, people seem to have missed that most of them seem to be connected as fossilized case forms of an original noun *h₂ed-/*h₂d- which must surely originally have meant ‘place’ or ‘location’ or something like that:

- As an endingless locative *h₂ed ‘at the location’, we have Latin ad and PGmc *at/English at, plus the Celtic preverb ad-. This is consistent with attested endingless locatives in Vedic and Hittite, which show an e-grade.

- As an instrumental *h₂d-eh₁ or *h₂d-oh₁; the first form gives us OIr dí and Latin dē, and the second PGmc *tō. Only Matasović’s dictionary of Proto-Celtic seems to have caught that dí/dē are instrumentals of *h₂ed; de Vaan proposes an original ablauting (?) preposition *de/*do cognate to the Greek Wackernagel particles δέ/δή (???--note that de Vaan also connects Slavic do to the Greek Wackernagel particles, but what would motivate the needed shift here?). The ablaut is also consistent with the instrumental of root nouns, which had a zero-grade.

- As an allative *h₂d-o giving Slavic do (de Vaan’s dictionary doesn’t catch this, again chalking it up to *de/*do), Germanic *ta (merging with *tō in most of the descendents) and...I think that’s it? The ablaut, again, is correct. (Plus we have other prepositions deriving from old allatives, like Greek πρό = Lat. per.)

Have I missed any examples in IE?

OK, onwards and upwards. This is where we move from basically orthodox to very, very speculative.

Guus Kroonen’s 2019 article The Proto-Indo-European Mediae, Proto-Uralic Nasals from a Glottalic Perspective proposes (or rather summarizes and expands on existing proposals) that the IE ‘plain voiced’/preglottalized stops are cognate to Uralic nasals, both deriving from Proto-Indo-Uralic glottalized (or otherwise ‘funny’) nasals; eksempleís bratiad we have PIE *(h₁)n̥gʷnis ‘fire’ = PU *äŋ- ‘to burn’, PIE *deḱ- ‘perceive’ = PU *näki- ‘to see’, PIE *ieǵ-/*ieg- ‘ice’ = PU *jäŋi ‘id’. Suppose we buy this at face value--a change of glottalized nasals to implosives is attested in a Kiranti language of Nepal, so it is not terribly far-fetched on its face. (Kroonen’s article, for what it’s worth, is only three pages long, so it doesn’t go into much detail).

Are there any examples of Uralic cognates to this pre-IE noun *h₂ed-? IF there are, AND IF Kroonen is correct that the IE mediae correspond to Uralic nasals, THEN we would expect an -n- in the Uralic reflex. I am being obnoxiously bold here because we are treading into pretty speculative territory.

At this point I am getting to be out of my depth, because I can’t read or even find a lot of the relevant literature on Uralic. And we must also deal with the IE laryngeal, and to my knowledge it’s not entirely clear how the Indo-Uralicists deal with potential laryngeal cognates. Wikipedia’s article on laryngeal theory, citing Jorma Koivulehto--who may or may not be considered serious, I don’t know--has a short section on proposed Uralic cognates whereby any of the three IE laryngeals may be cognate to PU *x, *š or *k, the last appearing only word-initially. The waters here are surely going to be considerably muddied by early and pervasive borrowing between IE and Uralic, and because I am not a Uralicist, I am left to eyeball possible cognates. But we know Proto-Uralic had a locative in *-nå/-nä. Čop (cited in Zhivlov’s chapter on the origins of IE ablaut, same volume) thinks some PU case endings, like the ablative in *-tå/*-tä (c.f. IE *-t?), deleted certain preceding vowels, but the locative was apparently not among them. Here I am out of my depth. Is it possible that a preceding laryngeal, as e.g. *-xnA, blocked syncope of a preceding vowel in Uralic? In the coda of an initial syllable, Proto-Uralic *x generally led to vowel shenanigans, but maybe not in a case ending where the preceding vowel would not be initial. We would maybe expect weird pronominal locatives. I don’t even know where I would begin to start looking to read about this, and I expect I wouldn’t be able to read half of what I dig up.

This is probably bullshit entirely, but half-baked thoughts are what blogs are for. If there is a cognate then it might well be a regular noun, not morphological. I can’t find anything in the appendix of Sammallahti’s Uralic Historical Phonology that looks like it might fit the bill, however.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is he Alexandros, not Alexander?

From the very beginning, I wanted to use Alexander’s real name in Dancing with the Lion. I did so for the same reasons I chose to write in his point-of-view in the first place, not in the heads of people all around him.

I want to make him real. “Alexander the Great” is a legend. Alexandros of Macedon, or really Makedon, was a living, breathing human being. That’s who I’m writing about.

Some readers may think it pretentious, or that I’m making all those weird Greek names harder. But again, I’m not writing about the legend, I’m writing about the boy. And the notion that “Alexander” is easier for English-speakers to say than “Alexandros” strikes me as naive. Same thing with Philip and Philippos. Now I might give you that Aristotle is easier than Aristoteles, but for the most part, the name thing affects a bare handful. If readers can handle Hephaistion and Erigyios (for which there are no alternatives), I think they can manage Aristoteles! I dislike underestimating or insulting my readers.

ALL these Greek names look strange to English-speakers, and a lot of folks will just gloss them. They’ll become the Eri-guy or Heph, or Leo (for Leonnatos). That’s okay.

My students love to make up nicknames in class for ancient figures, and if people think Greek names appear odd, try Suppiluliuma (a Hittite king). But so fun to say! I’d get my whole Ancient Near Eastern class to pronounce names together, at once, just so nobody felt stupid for having no clue how to say something that’s six syllables long. At first, they were a bit reluctant, but after the first few times, they really got into it. Suppiluliuma was dubbed “Soupy,” but I think the funniest was “Mega-bus” for Megabyzos, a Persian general.

I don’t want to make fun of people’s names, but teaching gives me a good idea of how readers are going to see these. While on the one hand, readers can certainly handle the real Greek, I fully expect a lot of readers will shorten them in their heads. I’m cool with that.

Yet if readers would like to hear the names, on my website I have audiofiles of me pronouncing them. Sometimes readers can guess, but accents might be a surprise. For instance, with Alexander’s own name, as we say it al-ex-AN-der, most readers probably assume it’s al-ex-AN-dros. It’s actually a-LEX-an-dros.

So if, like me, you love language and hearing the names, pop over to the website and take a listen. Otherwise, as you read, you can pronounce/remember those suckers however works best for you!

#dancing with the lion#alexander the great#alexanderthegreat#historical fiction#Greek language#Suppiluliuma is fun to say#asks

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was time to check on IW235 again. Last time I checked on this world, which the most prominent local civilization called “ki”, they had just learned of copper and ceramics. By my calculations, they should have just learned of iron, and may be experimenting with a iron-carbon alloy. The obvious first sign would be a small increase in CO2 as they burn organic matter to heat their smelteries.

I decided to run the atmospheric scan as I passed through the outer ring of asteroids. A few moments and the green light turned on, notifying me that the readout was ready. Wait, that can’t be right, I’m seeing much more CO2 and SO2 then expected, without the ash from a recent volcanic eruption. I also see far more radioactive isotopes in their atmosphere than expected. It’s almost like they had a reactor meltdown, several times over.

As I make a closer approach nearing the inner ring of asteroids, I see on the magnified feed that the night side of the planet has millions of glowing dots. On a hunch, I turn my radio receiver on. Amongst a crackle of overlapping signals, one stands slightly stronger.

“You are listening to 102.5 KZOK, the Seattle Classic Rock Station.”

How have they already learned of radio communication, and what language was that, it sounds nothing like any of the languages from last time, perhaps it is closest to the language spoken by the people who lived to the northwest of Sumer. Give the interpreter a try, it pieces together a bit, the first section is fully understandable, but after the four untranslatable syllables, it devolves, the first part is probably a name, and then some weird talk about old rocks and some form of land-harbor.

I decide to open communication as I get even closer, seeing their network of satellites.

[“I know you cannot understand me, I am speaking the closest known language to yours, I wish to question how you have achieved nuclear technologies over 5000 years ahead of projection.”, translated from an early version of the Hittite language]

There was a crackle, and I could swear sounds of elation, followed by a set of short buzzes with words in the middle, “|| | plus | || is || Please send back your equivalent in Binary.”

The computer immediately started to working and this translated well

“1101+1011 is 11000, return your signal for this in base 2”

I sent back our equivalent, and they sent another message

“Hello, the language you had is similar to [untranslateable] please send a map encoded as follows and a number corresponding to the number of cycles of orbit.”

Their requested encoding was shockingly similar to our default, I sent them an image of the section of land this language came from, and that it has been several thousand cycles.

A new voice spoke up, in a language that came from east of Sumer, on a subcontinental peninsula.

“Do you speak preparation?”

In this language, I replied

“I do not know what the name of this language is, but I do speak it, I would like to know how you have advanced to a nuclear age so quickly. May I have a copy of your technological histories.”

“I am having some trouble understanding, what is a technological history, we know how we made our technology, there is no fictious aspect”

“The stories of you technologies past.”

“I believe I understand, we will send you what we know, however, we only have many high detail verified accounts for around 300 cycles, we will send what we can from before then, but it becomes increasingly untrustable.”

I receive a data packet containing many books in various unknown languages, but the computer sets to work sorting them, and figuring out which is which.

I speak with the human who knows a language that existed last time I was here, apparently it is considered an old language here, spoken by less and less people.

About a hour passes and another light turns on, notifying me that the computer is done deciphering the new language’s written forms. it is remarkable, not only is this species unusually fast to progress and change, over the last 250 cycles, they have rapidly changed almost all aspects of their culture. I will have to submit this to high command so that we may decide what to do next.

I had accidentally broken protocol, I had assumed the existence of Satellites implied a level of space travel the humans did not yet have. It has to be considered what effects granting them advanced space travel may have, but we are rethinking our models on civilization development already.

Turns out cultures and civilisations aren’t meant to disappear or evolve so quickly. And species aren’t meant to develop technology so quickly too. So, after their last visit 5000 years ago, the aliens are wondering where the FUCK are the ancient Mesopotamians.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

PIE Case Endings

In my last post, I discussed the reconstruction of the amphikinetic nominative by Kloekhorst (2018), and concluded that his reconstructed *CéC-C-Ø is incorrect, and we should rather reconstruct *CéC-oC-s. However, Kloekhorst spends more than half of his paper discussing the singular athematic case endings, and so I shall follow up my last post by doing the same.

The obvious place to begin in the nominative singular. In animates, the most widespread ending is *-s, with a zero ending *-Ø normal in late PIE mobile resonant-stems (r-, l-, m-, and n-stems). As argued in my previous post, this zero ending is due to Szemerényi’s law, and in early PIE times the ending *-s was the only one. And yet, Kloekhorst argues that there are problems with this formulation. Firstly, he cites Keydana (2014), who argues that Szemerényi’s law is phonetically problematic, and secondly, he states that many animate words have a zero-ending that cannot continue an *-s, citing his favourite word *ǵʰésr, as well as *h₂-stems.

However, these objections are easy to counter. Firstly, while it is true that the usually-stated pathway, *-VRs > *-VRR > *-V̄R, isn’t that likely, at the very least the initial assimilation, we can posit a direct development of *-VRs > *-V̄R by assuming that when the *s was lost, the weight of the syllable was retained by transferring the mora from the now-lost *s onto the vowel, causing it to lengthen.

Secondly, his asigmatic nom.sg. forms are also straightforward to dispense with, as I have shown that Hittite kessar continues *ǵʰésors, and the *h₂-stems more than likely owe their asigmatic nom.sg. to an old neuter origin in many cases that was subsequently granted an animate accusative case when the feminine emerged as a gender.

Moving onto the dative and locative singular, Kloekhorst discusses the contrast between Hittite unaccented -i and accented -ī in the dative-locative, and then asserts that the accented ending goes back to *-éy. However, he adduces no evidence for this, and I know of no probative parallels - the only certain examples of *éy > *ī are all post-velar, and it seems highly implausible that Hittite would have generalised such a marginal variant. A more realistic scenario is that both endings go back to the i-locative, exactly as is assumed for Greek.

On the basis of a comparison between his incorrect reconstruction of Hittite’s dative-locative and the Mycenaean dative(-locative), which varies between -e /-ej/ and -i /-i/ (only in s-stems), Kloekhorst reconstructs a PIE dative in *-i ~ *-éy. However, this comparison is invalid, so we cannot securely reconstruct such ablaut for the dative, even if it is a priori expected. Kloekhorst then goes on to compare this reconstruction with the i-locative, which was likely originally always unstressed *-i, concluding that PIE did not originally have a neuter dative.

However, Kloekhorst completely disregards the strong affinity of the i-locative with the endingless locative, a move which utterly baffles me. Supposing that the i-locative was created from the endingless locative trivially explains why amphikinetic nouns have i-locatives like *ph₂téri - they were created from endingless locatives like *ph₂tér. The suffix accent of these forms is readily explainable from the fact that the form is endingless - there’s no ending to carry the accent that should otherwise go on the ending. This explanation isn’t new, either, as it’s cited by just about anyone who does delve into internal reconstruction of the case endings.

There may still be a connection between the dative and i-locative, but if so, it’s more than likely the exact opposite of what Kloekhorst speculates. The key observation is that the static and proterokinetic dative and locative were identical, save for the presence or absence of the final *-i. When the pressure to provide the locative with an overt ending appeared, it was natural to adopt the ending of the dative, which was then extended to the structurally identical amphikinetic locative as well, thus creating the i-locative. Against this account, however, is the fact that the o-stem dative is *-ōy < *-oey, whereas we’d expect *-oy with the zero-grade if the ending ablauted, exactly like the instrumental singular *-oh₁.

Next is the allative, which Kloekhorst reconstructs as *-ó, citing the comparison between Sanskrit prá, Greek πρό, and Hittite parā, all “forward” as proof. While this connection is surely correct, and the PIE form certainly *pró, this reconstruction of the allative is fatally undercut by Melchert’s demonstration that the allative rather reflects *-eh₂, which leaves Kloekhorst’s further account completely invalid. Note that this justifies connecting the endingless locative with the i-locative, as Kloekhorst’s connection with the allative evaporates into nothing.

Kloekhorst’s account of the last case, the instrumental singular, starts out with the mostly reasonable connection of the Hittite ending, reflecting *-(é)t, with the Sanskrit pronominal allatives mát, tvát. However, when it comes to compare with the normal instrumental ending *-(é)h₁, Kloekhorst relegates the entire discussion to a footnote, where he simply comments that, following Kortlandt (2010), “after Anatolian has split off from PIE, word-final *t in certain postconsontal (sic) environments regularly yielded *h₁ (through a stage *d, cf. the development of word-final *t > d as witnessed in Latin), which was then generalized to the full grade as well, giving rise to the new instr. ending *-(e)h₁.” This account is clearly ad-hoc, and it seems that Kloekhorst knows it, not wanting to draw undue attention to this severe weak point.

The rest of Kloekhorst’s paper discusses the consequences of his reconstruction, but for our purposes it is wholly irrelevant, as the basis of his reconstruction has been shown to be flawed and ultimately incorrect, so his further conclusions are similarly invalid. Moreover, it is telling that these methods do not work at all in the plural, and that he conveniently ignores the plural entirely. The only conclusion I can draw is that the traditional reconstruction must be upheld in its entirety, and Hittite demands no changes from it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was asked to share a bit about my conlangs (pt 1)

The first I'll share is Kwərdufoi -

Kwərdufoj is basically my Ursprache; it was build on me basically explaining gestural theory to myself. I actually didn't have a name for it until doing this post; kwərdufoi is the word for human being. Its maybe most unique feature is that it has "no phonemic vowels". Like a lot of conlangery it was inspired by some of the strange things in PIE. The thing that really set me off on this deep end was reading somewhere that PIE *póds, the root of foot, was somehow derived from the *dhéǵhōm 'earth' root and ~'a *p indicating body parts such as in the words finger, fist, foot, palm, Latin for 'tail', Hittite for 'shame' and so on' but I can't find a source on that quote and I'm not convinced I didn't imagine it or make it up after some other real claim. It's also problematic that this is the result of millenia of entropy, not freshly made by gesturing primates, so this amount of embedded information was probably never in the primal language. My method of construction was to basically pick a "typical" number of phonemes. I then took a look at some basic word lists and simple texts (fables mostly) and decided to break down the semantics. In researching sememes I found that no one really had made a list they liked, so I decided to be a bit impressionistic and boiled things down as I saw them. I drew on lists of prepositions to get a set of directional words; I drew on Chinese classifiers to get lists of shapes and sets; I drew on common grammatical features and so on. I did some comparative grammar for alignment, that kind of stuff. The end result I lost but was something like 8 columns of sememes to derive words out of. I assigned consonants to that column by frequency (and the columns were arranged by frequencies as well). I wanted to make this language look "real" despite the really unrealistic characteristic of not having phonemic vowels. Now, with every consonant having an inherent schwa there was a question of how to organize roots. I decided if I could to base root structure a little on Hanzi and Mandarin word building logic, and largely ink-pen'd my way through the system. I generated a list of possible "syllable roots" given some quick rules syncopating schwas according to sonority. I selected against both homophones and roots that ran against sonority and created a very typically SOV postpositing language with no phonemic vowels. A joke I made was making the 1st person pronoun m(ə)n(ə) and the second təm(ə). The M-T pronouns prefixed to the N-M pronouns. But things erode over time. I've lost or destroyed a lot of the resources I have on it, so I recreated some things. Phonology: p - t -c - k b - d -ǵ - g f - s - ś - x m - n - ń - ŋ w - l - j - r ħ - h - ´ The c/acute series represents palatals; so c would be the voiceless palatal stop. The fricatives are ambiguously voiced. The aspirate series, true to its PIE-ness, represent a "rounding laryngeal", an "a-coloring laryngeal", and a glottal stop. After syncope and assimilation, each consonant can pick up a palatized, labialized, and labio-palatized feature from the frequent -j- and -w- contractions. The difference is however neutralized around the labials and the palatals. The glottal stop gives assimilating stops an additional phonation feature, like the aspirated/murmured consonants of PIE. But I found this ridiculous typing it out and write them as if they were geminated below. r could be uvular or trilled I don't care it just fits with the graph better if it looks like it's part of the most dorsal series. Noun phrases were naturally head-final. Adjectives were noun-like and agreed with their head. Genitives were doubly marked; agreeing with their heads. The alignment was a confused mess of me trying to do an active-stative split, where nouns were marked absolutely for whether they were an agent or a patient regardless of whether the verb was 'ergotive', 'accusative', stative, essive, or whatever. The active was unmarked, the stative marked in -nə, dative -lə, genitive -jə-, instrumental -wə, locative -mə, lative -rə, adpositional -hə. After that number markers were attached; 0 singular, -tə dual, -təsə plural (which by assimilation would be realized as -ssə). Verbs were roughly as marked. Habitual mood had -pə´əśə, ; subjunctive/irrealis had -kəhə-, imperative had -təmə, negative mood had -nədə. Tense had a -bə´ə past, -kəsə future, -0 present; an explicitly perfective aspect had -tə´ərə-. A habitative mood took an aspect slot in -pə´əśə-; a mediopassive voice had -rənə- or a -0- active voice; the non-finite form had həxə, and a gerund-participle in -´əgə The verb structure was roughly prefixes.ROOT.derivation-MOOD-TENSE-ASPECT-VOICE-NOUN?-ENDINGS Here's a line:

English: The North Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger, when a traveler came along wrapped in a warm cloak. Gestural: də´əhəħə.rə pələhə.pəsəŋə nəfəpə.həxə.pəsəŋə-əsədə mətə-kəjəkəwə.bə´ə-lətə, kəwəćə pərəsəkə.cə-səməwə śə.lətə, kəwətə təjəkəjəkəw.pəsəŋə, kəwəhə.nə fəńə.wə nədə´əjəgə´əwə.wə kə´ə gə´əjəħə.śe.lətə, ləńəkəjəkəwə.bə´ə.lə 1st syncope: d´əhħ.rə pləh.psəŋ nəfp.psəŋ-əsd mət-kjəkw.b´ə-lətə, kwəć pərsk.cə-sməw śə.lətə, kwətə tjəkjəkw.psəŋ, kwəh.nə fəń.wə nədj´əgw´.wə k´ə gj´əħ.śe.lətə, lə-ńəkjəkw.b´ə.lə Assimilation: Ddahor Plapsoŋ Nefpseŋ-ezd metkikubbolt, kwec perskismo śibbolt, kwet tikikupsoŋ, kwan fińwa neddigguwa kke-ggjośilt, linkikubbol. Literal gloss: North Wind Sun and dispute-past.pl, which strong.comp was, when travel-er, who cloak warm wrapped in was, along came. Morpheme gloss: River.down Blow.er Blind.er-and against.go.past.3rd.dual, what.adj arm.adj.many stative_copula.past.3rd.dual, what.temporal on-go.er, what.animate warm.instrumental skin.instrumental inside-cover.stative.3rd.dual, to-come.past.3rd.dual

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 Chronicles 1

Verse 13 is awkward. Translations correct it without comment. The translations are divided between Egypt (what is in the text) and Cilicia. Que or Kue is near or equivalent to Tarsus (in Cilecia). The sense of the last verses is obscure to me. (In fact the whole chapter is rather awkward and my English worse than usual.) Maybe the Chronicler has his own style or the text is degraded in part. I left Egypt in since that is the word in the Hebrew and the conflict of Israel and Egypt is a regular theme. I get the sense also that there were enough horses for all those foreign kings the Hittites and the Syrians. They probably took their cut for goods brought from Cilicia through them, as is the the case for trade today in military hardware. Solomon is painted as a big wheel indeed (as Samuel noted a king would be - 1 Samuel 8 - from my memory of English translations, not yet read in Hebrew). I guess it is obvious that conflict related to governance, special interests, points of view, power struggles, and so on, are pervasive in the texts. There is no prescriptive behaviour here, as if we, as royalty, should go and do likewise. Solomon is to judge his people with wisdom and knowledge, and he will end up also being judged by them, and if Qohelet is his, he will join in his own judgment, or suffer reading it after his demise. There is an extra verse in the Hebrew, so 2 Chronicles 2 will be out by 1 in the verse numbers when we get there. No atnach in verse 2 - 40 syllables without a rest! Catch your breath where you can on these long recitations.

2 Chronicles 1 Fn Min Max Syll וַיִּתְחַזֵּ֛ק שְׁלֹמֹ֥ה בֶן־דָּוִ֖יד עַל־מַלְכוּת֑וֹ וַיהוָ֤ה אֱלֹהָיו֙ עִמּ֔וֹ וַֽיְגַדְּלֵ֖הוּ לְמָֽעְלָה 1 And Solomon the child of David was resolved concerning his kingdom, and Yahweh his God was with him and made him to be greatly ascendant. 3d 4C 14 14 וַיֹּ֣אמֶר שְׁלֹמֹ֣ה לְכָל־יִשְׂרָאֵ֡ל לְשָׂרֵי֩ הָאֲלָפִ֨ים וְהַמֵּא֜וֹת וְלַשֹּֽׁפְטִ֗ים וּלְכֹ֛ל נָשִׂ֥יא לְכָל־יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל רָאשֵׁ֥י הָאָבֽוֹת 2 And Solomon talked to all Israel, to the chiefs of thousands and of hundreds, and to the judges and to every principal for all Israel, the heads of the fathers. 3d 4B 40 וַיֵּלְכ֗וּ שְׁלֹמֹה֙ וְכָל־הַקָּהָ֣ל עִמּ֔וֹ לַבָּמָ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֣ר בְּגִבְע֑וֹן כִּי־שָׁ֣ם הָיָ֗ה אֹ֤הֶל מוֹעֵד֙ הָֽאֱלֹהִ֔ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר עָשָׂ֛ה מֹשֶׁ֥ה עֶֽבֶד־יְהוָ֖ה בַּמִּדְבָּֽר 3 And they went, Solomon and all the congregation with him, to the high place that was in Gibeon, for there was the tent of engagement of God which Moses the servant of Yahweh had made in the wilderness. 3d 4C 21 25 אֲבָ֗ל אֲר֤וֹן הָאֱלֹהִים֙ הֶעֱלָ֤ה דָוִיד֙ מִקִּרְיַ֣ת יְעָרִ֔ים בַּֽהֵכִ֥ין ל֖וֹ דָּוִ֑יד כִּ֧י נָֽטָה־ל֛וֹ אֹ֖הֶל בִּירוּשָׁלִָֽם 4 Lamentably the ark of God, David had brought up from Qiryath-Yearim into David's base for it, for he had erected for it a tent in Jerusalem. 3c 4C 25 10 וּמִזְבַּ֣ח הַנְּחֹ֗שֶׁת אֲשֶׁ֤ר עָשָׂה֙ בְּצַלְאֵל֙ בֶּן־אוּרִ֣י בֶן־ח֔וּר שָׂ֕ם לִפְנֵ֖י מִשְׁכַּ֣ן יְהוָ֑ה וַיִּדְרְשֵׁ֥הוּ שְׁלֹמֹ֖ה וְהַקָּהָֽל 5 And the brass altar that Betsalel, child of My Light, child of Hur had made, he set up before the dwelling of Yahweh, and Solomon and the congregation searched out for it. 3e 4C 25 12 וַיַּעַל֩ שְׁלֹמֹ֨ה שָׁ֜ם עַל־מִזְבַּ֤ח הַנְּחֹ֙שֶׁת֙ לִפְנֵ֣י יְהוָ֔ה אֲשֶׁ֖ר לְאֹ֣הֶל מוֹעֵ֑ד וַיַּ֧עַל עָלָ֛יו עֹל֖וֹת אָֽלֶף 6 And Solomon offered up there on the altar of brass in the presence of Yahweh that was at the tent of engagement, and he offered up on it a thousand burnt offerings. 3c 4C 24 9 בַּלַּ֣יְלָה הַה֔וּא נִרְאָ֥ה אֱלֹהִ֖ים לִשְׁלֹמֹ֑ה וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ל֔וֹ שְׁאַ֖ל מָ֥ה אֶתֶּן־לָֽךְ 7 In that night God appeared to Solomon, and said to him, Ask what I will give you. 3e 4B 13 10 וַיֹּ֤אמֶר שְׁלֹמֹה֙ לֵֽאלֹהִ֔ים אַתָּ֗ה עָשִׂ֛יתָ עִם־דָּוִ֥יד אָבִ֖י חֶ֣סֶד גָּד֑וֹל וְהִמְלַכְתַּ֖נִי תַּחְתָּֽיו 8 And Solomon said to God, You yourself have done with David my father great kindness, and have made me reign in his stead. 3d 4C 23 7 עַתָּה֙ יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהִ֔ים יֵֽאָמֵן֙ דְּבָ֣רְךָ֔ עִ֖ם דָּוִ֣יד אָבִ֑י כִּ֤י אַתָּה֙ הִמְלַכְתַּ֔נִי עַל־עַ֕ם רַ֖ב כַּעֲפַ֥ר הָאָֽרֶץ 9 Now Yahweh, God, let your word with David my father be verified, because you have made me reign over a people abundant like the dust of the earth. 3e 4C 18 16 עַתָּ֗ה חָכְמָ֤ה וּמַדָּע֙ תֶּן־לִ֔י וְאֵֽצְאָ֛ה לִפְנֵ֥י הָֽעָם־הַזֶּ֖ה וְאָב֑וֹאָה כִּֽי־מִ֣י יִשְׁפֹּ֔ט אֶת־עַמְּךָ֥ הַזֶּ֖ה הַגָּדֽוֹל 10 Now wisdom and knowledge give me, that I may go out before this people and come in, for who will judge this your great people. 3d 4C 22 12 וַיֹּ֣אמֶר־אֱלֹהִ֣ים ׀ לִשְׁלֹמֹ֡ה יַ֣עַן אֲשֶׁר֩ הָיְתָ֨ה זֹ֜את עִם־לְבָבֶ֗ךָ וְלֹֽא־שָׁ֠אַלְתָּ עֹ֣שֶׁר נְכָסִ֤ים וְכָבוֹד֙ וְאֵת֙ נֶ֣פֶשׁ שֹׂנְאֶ֔יךָ וְגַם־יָמִ֥ים רַבִּ֖ים לֹ֣א שָׁאָ֑לְתָּ וַתִּֽשְׁאַל־לְךָ֙ חָכְמָ֣ה וּמַדָּ֔ע אֲשֶׁ֤ר תִּשְׁפּוֹט֙ אֶת־עַמִּ֔י אֲשֶׁ֥ר הִמְלַכְתִּ֖יךָ עָלָֽיו 11 And God said to Solomon, In that this was with your heart, and you did not ask for riches, material wealth, and glory, nor the throat of those hating you, and even for many days, you did not ask, but you asked for yourself, wisdom and knowledge, that you may judge my people over whom I have made you king. 3e 4C 50 25 הַֽחָכְמָ֥ה וְהַמַּדָּ֖ע ��ָת֣וּן לָ֑ךְ וְעֹ֨שֶׁר וּנְכָסִ֤ים וְכָבוֹד֙ אֶתֶּן־לָ֔ךְ אֲשֶׁ֣ר ׀ לֹא־הָ֣יָה כֵ֗ן לַמְּלָכִים֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לְפָנֶ֔יךָ וְאַחֲרֶ֖יךָ לֹ֥א יִֽהְיֶה־כֵּֽן 12 The wisdom and the knowledge is given to you, and riches and material wealth and glory I will give you, such that there was not for kings who were before you, and after you neither will there be such. 3e 4C 10 35 וַיָּבֹ֨א שְׁלֹמֹ֜ה לַבָּמָ֤ה אֲשֶׁר־בְּגִבְעוֹן֙ יְר֣וּשָׁלִַ֔ם מִלִּפְנֵ֖י אֹ֣ה��ל מוֹעֵ֑ד וַיִּמְלֹ֖ךְ עַל־יִשְׂרָאֵֽל 13 So came Solomon to the high place that was in Gibeon, Jerusalem ... from before the tent of engagement, and reigned over Israel. 3e 4C 25 7 וַיֶּאֱסֹ֣ף שְׁלֹמֹה֮ רֶ֣כֶב וּפָרָשִׁים֒ וַֽיְהִי־ל֗וֹ אֶ֤לֶף וְאַרְבַּע־מֵאוֹת֙ רֶ֔כֶב וּשְׁנֵים־עָשָׂ֥ר אֶ֖לֶף פָּרָשִׁ֑ים וַיַּנִּיחֵם֙ בְּעָרֵ֣י הָרֶ֔כֶב וְעִם־הַמֶּ֖לֶךְ בִּירֽוּשָׁלִָֽם 14 And Solomon gathered chariot and cavaliers, and he had a thousand four hundred of chariot and twelve thousand cavalry, and he left them in the cities of the chariot and with the king in Jerusalem. 3e 4C 33 19 וַיִּתֵּ֨ן הַמֶּ֜לֶךְ אֶת־הַכֶּ֧סֶף וְאֶת־הַזָּהָ֛ב בִּירוּשָׁלִַ֖ם כָּאֲבָנִ֑ים וְאֵ֣ת הָאֲרָזִ֗ים נָתַ֛ן כַּשִּׁקְמִ֥ים אֲשֶׁר־בַּשְּׁפֵלָ֖ה לָרֹֽב 15 And the king gave the silver and the gold in Jerusalem like stones, and cedar he gave like sycamores, that are abundant in the lowly place. 3c 4B 23 18 וּמוֹצָ֧א הַסּוּסִ֛ים אֲשֶׁ֥ר לִשְׁלֹמֹ֖ה מִמִּצְרָ֑יִם וּמִקְוֵ֕א סֹחֲרֵ֣י הַמֶּ֔לֶךְ מִקְוֵ֥א יִקְח֖וּ בִּמְחִֽיר 16 And the horses brought out that were Solomon's were from Egypt, and from Que. The wares of the king from Que they took at a price. 3c 4B 15 15 וַֽ֠יַּעֲלוּ וַיּוֹצִ֨יאוּ מִמִּצְרַ֤יִם מֶרְכָּבָה֙ בְּשֵׁ֣שׁ מֵא֣וֹת כֶּ֔סֶף וְס֖וּס בַּחֲמִשִּׁ֣ים וּמֵאָ֑ה וְ֠כֵן לְכָל־מַלְכֵ֧י הַֽחִתִּ֛ים וּמַלְכֵ֥י אֲרָ֖ם בְּיָדָ֥ם יוֹצִֽיאוּ 17 And they brought up, and they brought out from Egypt, chariot at six hundred of silver, and horse at one hundred and fifty, and so for all the kings of the Hittites, and the kings of Aram, by their means, they brought out. 3c 4C 29 20 וַיֹּ֣אמֶר שְׁלֹמֹ֗ה לִבְנ֥וֹת בַּ֙יִת֙ לְשֵׁ֣ם יְהוָ֔ה וּבַ֖יִת לְמַלְכוּתֽוֹ 18 And Solomon made a pronouncement to build a house to the name of Yahweh, and a house for his kingdom. 3e 4B 21

from Blogger http://ift.tt/2fczHEF via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

BLATERATIO SIOVANA (I)

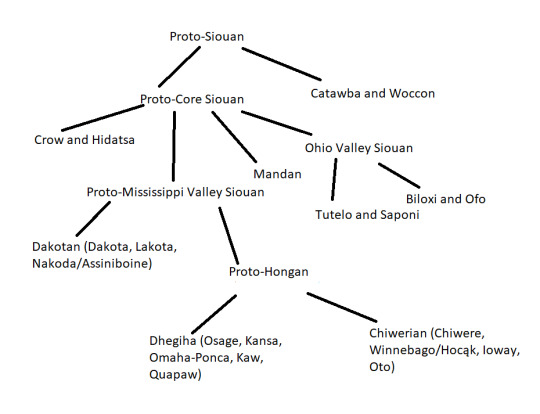

In the year 1500 or so, prior to European contact, the Siouan languages were spoken over a very wide range of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. Wikipedia gives the following map, which is a faithful reproduction of Ives Goddard’s map from Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 17: Languages.

The map itself is a massive, and gorgeous, wallpiece, with different language families marked in different colors and separated into the individual languages, but they’re not shown here.

When we think of Siouan, we generally think of the Lakota/Dakota/Nakoda Sioux, or perhaps the Osage, who live in the modern era on the Great Plains. It therefore comes as something of a surprise to learn that Siouan is actually an Eastern family, not a Plains one. The Proto-Siouan Urheimat was probably in the Kentucky-West Virginia area; Catawba, its closest relative, was spoken in upstate South Carolina until the early 20th century; and we know that most of the Siouan languages spoken on the Plains got there relatively recently as white expansion pushed Native tribes westward. (For example, when we first meet the Dakota, in the 17th century, they live in the Chicago area--not South Dakota).

I don’t have a scan of the full map, but if you look at the map you’ll find that we have a pretty good idea of who lived where when they were contacted by Europeans in most of the continent (though that’s, of course, not always the same date everywhere, so the map doesn’t represent the linguistic situation at any given point of time. In the Southeast, however, there are vast swaths of “unknown”. We have a suspicion, for example, that the Carolinas were one of the most linguistically diverse areas in the world before contact. But what’s left? Cherokee, Tuscarora, Catawba (no longer around, but documented), a few words of Pamlico (Carolina Algonquian) and Woccon (a close relative of Catawba), and a couple words of Saponi. That’s it, for an area that probably had at least twenty languages split across several families if not thirty.

Obviously this lack of data speaks to countless humanitarian atrocities, but for the linguist, and especially the Siouanist, it presents another, though obviously less serious, problem. Our suspicions are that the majority of Siouan’s diversity resided in the Southeast at contact, but it’s all gone and nobody wrote it down, barring a lucky manuscript finding. And we don’t really have earlier stages of Siouan to check either. It’s rather as if we were trying to reconstruct Indo-European, but only possessed Romance, modern Irish and Welsh, Slavic and maybe Armenian or a modern Germanic language. (Luckily, Proto-Siouan is not as old as PIE, but, well, PIE is not really that old, either; if break-up was 4000-3500 BC, our earliest attestations of Hittite are 1500 BC, so we’re in the dark for only about two to two and a half thousand years.)

The following MSPaint diagram gives a relatively decent overview of the...current consensus regarding the internal divisions of Siouan.

Catawba (spoken in upstate South Carolina until the 1940s or ‘50s) and Woccon (attested in a badly-written wordlist from the 17th century) represent a single subfamily that play the Anatolian to the rest of Siouan’s Latin/Greek/Sanskrit/Slavic/Baltic. This much is for certain. Catawba is well-documented, but unfortunately the High Priest of Catawba passed away unexpectedly just before his three-volume magnum opus was set to be published, which magnum opus now lingers in an archive in Philadelphia. So it goes.

Core Siouan (we could also just call this Siouan and call Siouan + Catawba Siouan-Catawba, but we’ll use the term Core Siouan) breaks up into four main branches (most of this is taken from Rory Larson’s 2016 article):

-Ohio Valley (or Southeastern Siouan). There are three decently-documented members of this branch (Biloxi, Ofo and Tutelo) and one attested by two words (Saponi, which must have been very close to Tutelo). There are only a couple of known shared sound changes that characterize Ohio Valley; one is the merger of the original Proto-Siouan glottalized fricatives *sˀ *šˀ *xˀ to their unglottalized counterparts, and another may have been the fortition of (the now merged, from *š and *šˀ) *š to /č/, but there were perhaps exceptions here.

Ohio Valley then splits into Tutelo-Saponi (fairly conservative barring a possible merger of *s and some instances of *š that didn’t change to /č/) and Ofo-Biloxi (characterized by a shared loss of word-initial *w and *h before a vowel).

Were there more members of Ohio Valley? Almost certainly. We know Ohio Valley was fairly conservative, but it’s not that well-documented--only Biloxi really got the full treatment; we have large gaps in our understanding of the morphology of the others. There may have been other Ohio Valleys; if we had them we’d know a heck of a lot more about Proto-Siouan. Unfortunately, we don’t.

--Crow-Hidatsa (also known as Missouri Valley)--wouldn’t Corvic be a snappier name? if we’re going to go down that route then the Meskwaki-Sauk-Kickapoo group of Algonquian should be Vulpic, but the Meskwaki generally prefer not being called the Fox anymore--seems to be strangely conservative and yet highly innovtive. Its two members, Crow and Hidatsa, split off from each other very recently. Corvic is characterized by a number of very unusual proposed changes, such as a metathesis change whereby the first two vowels of a word swap, *CV₁CV₂ > CV₂CV₁. Crow-Hidatsa (and Mandan) also undid “Carter’s Law.” This is worthy of a bit more discussion.

Proto-Siouan, you see, had a strong second-syllable stress rule. I have a suspicion that this probably got passed along to Great Lakes-area Algonquian--cf. Nishnaabemwin’s syncope rule [e.g. standard Ojibwe makkwa ‘bear’ > Nishnaabemwin mkkwa], or the second-syllable vowel-lengthening rule in Menominee [e.g. *aθemwa > anɛ:m]--Northern Algonquian is reported to have a strong first-syllable stress rule and, as this is also found in Arapaho (I think?) and maybe elsewhere, this is thought to be original, at least by Ives Goddard (p.c.). In any case, when a pre-Proto-Siouan stop *p *t or *k formed the onset of the second syllable of a word, it got preaspirated. There are surely Catawba cognates that can attest to this, but the point is that we basically only ever see preaspirates in second syllables. (This is somewhat obscured by the fact that the vowels of word-initial syllables often drops in the daughters, yielding clusters or, if there was no onset consonant, nothing at all)

But Mandan and Corvic appear to have undone Carter’s Law. This, combined with their odd-man-out nature (it’s just not really clear at all how they fit into things--Mandan may or may not be a wayward member of Mississippi Valley, but I think the consensus these days is “separate branch”--I need to send another email or two), suggests to me that maybe Carter’s Law wasn’t a Proto-Siouan rule at all and may have developed a bit later on, affecting Mississippi Valley and Ohio Valley but skipping Corvic and Mandan, so that no sound change needs to be proposed for those branches at all. Corvic and Mandan also have a change whereby *y and *r merge as /r/. This change is also found in Hocąk, so it might have been areal. (C.f. the change of *y to /čʰ/, which is found in Dakotan and...Ofo, spoken in Mississippi and Louisiana.)

(then again that could also be areal, since we first meet the Ofo in the Cincinnati area by the name of the Mosopelea, and that’s not that far from the Dakota who, as we’ve seen, were in Illinois at first contact)

I don’t think anybody’s tried to a study in shared lexical innovation in Siouan, but somebody should (maybe me), because there’s a lot of weird lexical innovation in Siouan and it would probably clear up questions like “what’s going on with Mandan?” A major source of this lexical innovation--and a major reason for Siouan being so frickin’ difficult to reconstruct--is the fact that Proto-Siouan had a lot of derivational prefixes, that a lot of basic lexical items ended up with different derivational prefixes in different daughters, and that because these derivational prefixes were now word-initial their vowels usually dropped and formed difficult-to-untangle clusters. (Doesn’t comparative Sino-Tibetan suffer from similar issues?)

Mandan, as noted, probably forms its own branch. It is most notable for having undergone a “swap” shift whereby PS *š becomes /s/ and *s becomes /š/.

Mississippi Valley forms the core of attested Siouan. It has three branches: Dakotan, Hongan (the Chiwere-Winnebago/Hocąk-Ioway-Oto group), and Dhegiha (Osage, Omaha-Ponca, etc.).

Mississippi Valley Siouan is characterized by the development of a very large number of onset clusters, but no coda consonants (except in a couple of daughters that deleted final vowels). Except for the preaspirates /hp ht hk/, their provenance is shakily understood other than that most of them seem to derive from initial-syllable syncope. E.g, if you attach the 1sg prefix *wa- onto a verb stem in h-, you get *wăh-, then *wh-, and then fortition of the *w to /p/, giving a postaspirate *pʰ.

Within Mississippi Valley Siouan we have some evidence that Dhegiha and Hongan form a subgroup (Dhegihongan?). I pushed a friend of mine into writing a term paper on this, possibly for reasons of selfish curiosity. The main phonological isogloss is the merger of *wR with *R (where *R is “funny *r,” a sound that appears to have been *r but which shows unusual reflexes)--Dakotan merges *wR with *wr. There’s also a debuccalization of *p to /h/ before *t, and an innovated 1pl inclusive patient prefix *wa-.

This is already getting to be rather long, so I think I’ll cut it here and go further in-depth into phonology in Part II...

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

PIE Amphikinetic Accent-Ablaut and Hittite

Well, it’s been a while, but hey, university’s over now, so I have time to spend on this. I recently read a paper (Kloekhorst, 2018) about the nominal accent-ablaut paradigms (and, confusingly, the singular athematic noun cases too, but that’s another matter) and got thinking about some of his core assumptions, primarily his account of amphikinetic ablaut, for which we must consult Kloekhorst (2013).

Naturally, we must start in the same place Kloekhorst does, with the commune noun kessar “hand”, which is cognate with Greek χείρ, Armenian jeṙn, and Sanskrit hásta-, representing PIE *ǵʰes-r-. The original Hittite paradigm was nom.sg kessar, acc.sg kisseran, oblique stem kissr-, with later spread of the accusative stem. The accusative and oblique stems are transparently *ǵʰsérm̥ and *ǵʰsr-´, with the i in the root syllable being from analogical spread of the *e from the nominative prior to being reduced due to being unstressed.

The nominative singular, on the other hand, is much more complicated. Kloekhorst assumes that due to the geminate ss, the preform must have had the *s in contact with another consonant, which is necessarily the *r, yielding *ǵʰésr. However, in a preform such as this, the *r would have phonetically been syllabic, whatever the Leiden school may think about whether or not syllabic sonorants were phonemic, and so I must question whether or not the *s would have been geminated regularly. On the other hand, gemination is certainly regular in the oblique stem, due to the *sr cluster, and potentially the accusative stem as well if *s was geminated after word-initial velars as well as medial velars, so analogical transfer is trivial. This observation fatally undercuts Kloekhorst’s argument.

So how should the nominative singular be reconstructed, then? It certainly must start *ǵʰés-, so the real question is what can yield final -ar. Considering the vowels that could yield a, only *or and *r̥ are possible, as *ōr is probably ruled out by the lack of plene spelling. At first glance *or isn’t possible either, as Hittite lost *r after unaccented *o, so Kloekhorst was still right, even if his argument was wrong. However, I believe it is likely that final *-ors would in fact yield -ar as well, to judge from medial *rs yielding rr as in ārras “arse” < *Hórsos.

The only snag here is that word-final *rs is attested in verbal paradigms, in the 3sg. preterite of ār- “to come” (ārs “he came”), and in the 2sg. imperatives of kars- “to cut off” and wars- “to harvest, wipe” (kars “cut!”, wars “harvest!”). Yet, all of these forms are the regular ones, with the -s of the 3sg. preterite and the s of the root easily being restorable analogically, so none of these counter-examples are probative.

We are left with two alternatives, then: Kloekhorst’s *ǵʰésr̥, and my proposed *ǵʰésors. The cognates listed above don’t offer any help in deciding between them, however, as Skt. hásta- isn’t an r-stem, and Gk. χείρ and Arm. jeṙn both reflect a generalised *ǵʰésr-, with consonantal *r, which could just as easily be generalised from the oblique after levelling the root ablaut as being the original nominative levelled wholly into the other cases (and then back again).

Hence we must turn to other considerations. The n-stems are another major set of amphikinetic nouns, with hāras, hā̆ran- “eagle” < *h₃ér-n- being the standard example. The stem for this word, with its real and invariant a, seems to represent *h₃éron- a stem that should be generalised from the nominative. Indeed, this seems to work for the nominative itself - a preform *h₃érons would regularly yield hāras, and so makes a good parallel to my hypothetical *ǵʰésors.

As anyone remotely familiar with PIE nouns, and the amphikinetic stems in particular, should have already seen, these preforms would be expected to have undergone Szemerényi’s law in PIE already, whereby a word-final fricative is lost after *r, *l, *m, and *n, with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel. However, let us suppose for a moment that Szemerényi’s law had not yet acted when Anatolian split off from the rest of the family. The preforms *ǵʰésors and *h₃érons actually are exactly the preforms for the expected Late PIE forms *ǵʰésōr and *h₃érō(n).

Before proposing exactly this scenario, we must consider other forms considered evidence for Szemerényi’s law in Anatolian, starting with the 3pl. preterite ending -er < PIE *-ēr < **-érs. However, PIE *-érs would probably yield -er anyway, with my proposed sound change *rs > r / _#. The retention of *e as e is no problem either, as the ending was almost certainly always stressed.

Another case is the hysterokinetic n-stems, represented by ishimas, ishimen-. The nom.sg. stem+ending -as is usually considered to represent *-ēns but I think this is uncertain - depending on the timings of the relevant changes, the *ē may not shorten in time to undergo the change to a in the environment _nT. Indeed, these forms are the only possible evidence I know of. *-éns, however, certainly does, as shown by the genitive singular -was < *-wéns of the verbal noun suffix, and so we can take these n-stems from a nom.sg. *-éns as well.

The final case is the neuter collectives in *h₂ to resonant stems, such as widār < *udórh₂ (cf. Greek ὕδωρ, Umbrian utur). However, here again we do not require Szemerényi’s law, as *ó regularly yields a long vowel and laryngeals are lost word-finally.

It follows that there is no unambiguous positive evidence for Szemerényi’s law in Hittite, so we are probably free to assume my scenario of Szemerényi’s law post-dating Anatolian’s separation from the family, and the nom.sg. *ǵʰésors for pre-Proto-Anatolian.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Origin of the Hittite mēma/i- Verbs

The class of Hittite verb represented by mēma- “to speak” is a subtype of hi-verb with a singular stem in a (thus 1sg mēmahhi) and a plural stem in i (thus 1pl mēmiweni). Over the course of Hittite, these verbs gain secondary forms inflected according to the tarna- class, or with an invariant stem in a, or as thematic ye-verbs, all of which are trivial developments. While the synchronic facts of the class are quite simple, the history of the class requires a bit more work.

We can start by categorising the verbs in this class by their origin. The largest group are the imperfectives in -anna/i- (e.g. ishuwanna/i- to ishuwāi, both “to throw”), which Kloekhorst (2008) lists 23 of. There are also 7 historically, and some perhaps synchronically, reduplicated verbs (e.g. lilhuwa/i- “to pour”, related to lāhu- “to pour”), a pair verbs prefixed with ū- “here” and pe- “there” (ūnna/i- “to send (here)” and penna/i- “to drive (there)”, both to nāi “to drive”), another pair of verbs derived from adverbs (āppa/i- “to be finished” from PIE *h₁ópi “back”, related to Hittite āppa “behind”, and uppa/i- “to send, fetch” from PIE *úpo “up to”), and finally two compound verbs (taista/i- “to load” from PIE *dʰóh₁-s- “a load” + dāi “to put”, and dāla/i- “to leave be”, whose first part is related to dāi “to put”, and whose second part is related to lā- “to loosen”).

It’s fairly clear that this class originated in the dāi class, as evidenced by the stem in i, otherwise only found there. All that remains to be explained is where the a-stem forms in the singular came from. Kloekhorst (2008) states that in polysyllabic dāi verbs, the 3sg present became -ai, identical to that of the tarna- class, which triggered the creation of more a-stem forms, while monosyllabic verbs retained the length, and so did not undergo any influence.

While I agree in principle with this account, I disagree on the origin of the 3sg present in -ai. I don’t see any reason why the length of the word would prevent the normal lengthening from taking place, and the insistence that all members of the dāi class must be monosyllabic leads to absurd interpretations like ishamāi /sxmāi/, where /isx(a)māi/ is quite clearly to be preferred. Instead, I would suggest that it’s rather the placement of the accent that determined transfer to the mēma/i- class.

Firstly, observe that quite a number of verbs show plene spelling on their initial syllable: mēma/i, āppa/i, dāla/i, and ūnna/i. This strongly suggests at least these verbs have uniform initial accent. Like mēma/i-, we would expect initial accent in the other reduplicated verbs, as reduplicant accent is typical of reduplicated verbs in IE. Like āppa/i-, uppa/i- probably has initial accent. We can continue this way until all the non-imperfective verbs can be supposed to have initial accent. The imperfectives are slightly different, although if it is correct to derive the suffix from the verbal noun in -ātar ~ -ann- then it is reasonable to suppose accent on the initial vowel of the suffix.

It follows that all verbs that ended up in the mēma/i- class had accent uniformly before the *ai ~ i suffix. The verbs of the dāi class, however, had alternating accent between root and ending, and since so many verbs in the class had the form *CeH-i-, the root accent in the singular became conflated with the suffix (and in the 3sg present, with the ending, too). This split the pre-dāi class in two: one set of verbs had alternating accent between the ai suffix in the singular, and the ending in the plural, while the other set had fixed accent before the suffix. The pre-accented verbs then had a shortened 3sg present in -ai, and Kloekhorst’s scenario can continue exactly as envisioned.

0 notes