#I know what it is to be a victim of Nazism and imperialism

Text

>>> should not be judged just because he did it in the past

>>> his actions should be judged by looking at the time

It's so cute not to be able to read, but to judge others and block them without letting them say a word :)

As soon as you learn to read, find out what the principle of historicism is

#elden ring#the culture of arguing at a height#Blocking your opponent and continuing to argue with him in reposts...#I don't even know who is more pathetic here#these non-Nazis and non-imperialists#or me reading this argument from another account#My country lost 27 million in WW2#I know what it is to be a victim of Nazism and imperialism#But why give the floor to those with whom you disagree?

1 note

·

View note

Text

happy 2024. yall still have to suffer my rants. sorry

so i think everyone remembers that period from 2015 to 2021 or maybe later, when everyone was creaming themselves over the dead horse scenario of “wHaT iF the NaZiS wOn ThE wAr”

yeah i aint gonna go into specifics but im pretty sure everyone remembers. mostly because of what they wrote with superman.

god people need to stop milking this shit.

so I’ve gone into detail in other posts about how dc is notoriously flimsy and escapist with the subject of nazi germany and just…nazism in general, either they’ll just use it as a vehicle to virtue signal or they straight up deny its horrors. yeah, sad but true. same with this.

except there was someone (obviously non-dc affiliated) who actually got the superman scenario right. not grant morrison, venditti and every other weirdo who had their fingers in this literal dumpster fire. kim newman, who wrote “ubermensch” in 1991, before “red son” and the other superman alternate histories, and showed more empathy for the holocaust and the victims of nazi germany than dc could ever care to.

because. unlike dc, newman wasn’t running on propaganda tradition and cutesy escapism like they were.

continued under the cut.

tw: nazism, the holocaust, genocide, anti-semitism, racism, murder, historical gore, literary mention of israeli imperialism, and nazi propaganda

so right off the bat it’s obvious that newman knows his history. the story takes place in a recently reunified postwar germany at the end of the cold war. metropolis is analogous to berlin, it’s a famous city in-story that was split into an east and west sector. the main character is avram blumenthal, a holocaust survivor turned nazi hunter, much like the real life simon wiesenthal. the superman analogue in this story is held in spandau prison, the real-life facility for nazi war criminals where rudolf hess was imprisoned for the remainder of his life.

just by looking at that. you could never find a dc writer who puts in this much time and effort to research the past and depict it in a non exploitative manner.

there’s also some commentary on western us capitalism/consumerism that defined ‘our’ progress in the cold war (pizza hut and mcdonalds in the ussr anyone) and the “third position” of fascism being the “alternative” between capitalism and communism:

and! newman actually respects superman’s jewish mythos! he includes it in here, which is something i’ve never seen the overman writers do. jerry siegel and joe shuster were both jewish. and, no matter what dc tells you about nazis having ‘superheroes’ of their own, this was actually one of the reasons comics were hated in nazi germany.

newman also integrates the basic superman lore pretty well here, everything is recognizable. a ‘man of steel,’ ‘the man of tomorrow,’ ‘curt kessler’ (which, by the way, is way more creative than dc’s ‘karl kant’) is clark kent, the ‘green stuff’ is kryptonite, so on

newman also isn’t afraid to get dirty with the mythos, unlike the comics which like to play it safe with this (up to and including never talking about the holocaust at all). the johnathan and martha kent analogues of “ubermensch” aren’t the kindly couple that they should be. because this isn’t them and we're not supposed to like them. johann beats his adopted son and curt grows up arrogant. luise lang, the lois analogue, is a snotty propagandist that curt describes in ideologically typical misogynistic terms (another thing to note down dc, nazis did not respect women) who commits suicide to avoid being raped by the red army.

there's also something else that's interesting, the commentary on how harmful propaganda and journalism can be when serving a purpose. its implied a lot in here that the 'supervillains' that curt kessler/übermensch faces are actually all staged by the nazis, or if they're genuine (like the golem), their intentions are twisted to serve the bigger narrative.

curt kessler/übermensch is a state propagandist like luise lang was. the 'tages welt,' daily planet analogue in this story, sounds a lot like a version of der sturmer. he writes his own propaganda narratives to prop up his übermensch persona and vilifies innocent people in the process. the targets of nazi ideology get the names of villains from 1920s german fiction and they're like dogwhistles in itself if you know the context. "orlok" was a vampire that looked uncomfortably similar to anti-semitic caricatures, "mabuse" was a hypnotist "master of disguise" who "operated through a network of agents," characters co-opted and then twisted by nazism in-story. in real life we also have this with racists adopting "sh****k" as a slur from the shakespeare character.

newman also throws a curveball with that whole ‘nazi superhero who actually turns out to be good all along’ or whatever the shit that trope is. whatever. kessler apparently ‘defects,’ like he says here

but before that, he said this.

dude’s the same. sorry guys, no redemption arc here. this becomes relevant later.

kessler still blames "mabuse" for pornography, jazz, cabarets, things that defined progressive weimar germany before the nazis took over and shut it all down. again. another aspect taken from real-life history. and since a "red skull" is also name-dropped here, i'm also thinking that the "hydra" reference in this refers to the marvel organization of the same name.

you know. the one with tentacle iconography, the secret society that's framed in the mcu as controlling the world, starting wars and infiltrating governments everywhere to install global totalitarianism. which makes me wonder what kind of writers at marvel thought nazi germany would accept an organization that exemplifies the kind of fake "international conspiracy" they were railing against but that's another conversation. see here.

blumenthal recalls a time when he was a child in germany who naively hero-worshipped kessler/übermensch because of the propaganda around him. he wished he could fly and he wore a black blanket like a cape. while he was young a rabbi created a golem (the figure in jewish mythology made of clay) who was killed by kessler, and blumenthal swallowed the propaganda. even when his anti-semitic classmates aped kessler and beat him up.

kessler obviously doesn’t give a shit, he’s still brainwashed no matter how he tries to wave it off. he doesn’t care about the tattoo. instead he talks about using his x-ray vision to look at women’s breasts. like real-life racists confronted with their own wrongdoings kessler also resorts to whataboutism and goes “your family is dead but so is my whole planet”.

and he also says he’s only locking himself up because of his guilt. not actually over the atrocities of nazism. it’s that nazi germany is gone and so is his planet so he has nothing else to do and he doesn’t want to do anything. that’s it.

blumenthal retorts with this, which is just great in itself. im not going to outline it, newman does it pretty good already

this is one of the things i really liked. because it’s important and more importantly, relevant!! it’s so relevant because kim newman is fucking right. im reiterating that everything about the world in that second image is true.

i was a kid when charlottesville happened. tmi but that whole time is a blur. when i got older and learned about things, i remember thinking that maybe after that, we would take a good hard look at ourselves and just try to find out where we went wrong.

did we maybe have a history of being eugenicist slaveowning imperialists in the past who inspired nazi polices and still rallied around the flag and the military. did racism and nazism happen to run deep in america before 2017.

why were children and young adults so vulnerable and still are vulnerable to the alt-right pipeline, what are we putting out in media that could be desensitizing them to nazism. what kind of message are we sending when we don’t cover it in detail, and leave them to figure out nazism from shitty comics, or movies.

yeah. the majority of people ever asked that.

here’s what they actually did. especially in art and media, and im going to say, with dc since this is relevant to the image. they doubled down on some of the societal shit that led to that in the first place

you wanna know what the cw, bunch of braindead idiots, did right after charlottesville? pretty much the entire thing from the last paragraph, except with some vanilla bullshit because of course the arrowverse can’t ever portray nazism correctly even if they tried.

there’s an article that covers their failure in detail and also a reddit post which, obviously, some weirdos in the comments are brushing off. and it’s also not coincidental that a comic series came after this and cited the political climate. again. a bunch of important dc people were involved in promoting this. phil jimenez in particular also has a problematic history with depicting modern neo-nazism. grown adults put money into this. their actors and their fans supported them.

want proof?

mmm. alright smart guy. here’s that “different set of ideals” for you.

yeah, apparently they didn’t think through the consequences of a world where the fucking dirlewanger brigade would be celebrated as heroes.

you know what they actually cared about? some fucking stupid comic issue from the 1970s that was suddenly relevant because everyone felt the need to deny our own nazi-sympathizing rotten history and pin it somewhere else, rather than actually take a step back and evaluate where we went wrong as a society.

and actually they essentially made radicalization easier. they showed this bullshit to kids and basement-dwelling adults who don’t know anything about the world and only care about their typical comic high. how do they fucking sleep at night knowing that they’ve whitewashed real life atrocities?

they still are doing that. they casually throw around the words “hitler” and “nazi” to the point where it fucking means nothing. they’re using exploitative images of concentration camps just to get a rise out of people without ever covering their themes seriously. and you wanna know the worst thing about that? only a few people are calling this out. everyone else? nah they’re ready to consume that because it doesn’t matter to them like it does for some people.

in the story blumenthal believes that, without kessler existing, the ‘fire’ won’t start up again. this comes when nazism and genocidal neo-fascism are resurging and the israel bit is also pretty relevant today. like in real life the kids are ignorant because all they know about nazi germany and world war ii is from kessler. again. this man is a living symbol of nazism who has media getting made about him.

blumenthal’s right. because the world actually doesn’t need kessler and it’s better off without him. he passes a kryptonite suicide pill encased with lead, which kessler can bite through. and he gives him a choice.

living swastika kessler who has nothing to live for and is more of a problem than an actual help to humanity, bites the pill and kills himself. that’s it. he dies. his only worthwhile achievement is sucking it up and dying like a human man.

he’s dead. now finally humanity can start to heal.

so to round it all off basically. i think this book is part of a lesson. about swallowing that bitter pill that you don’t want to face and realizing, maybe there’s something problematic how we portray and in a way, whitewash nazism to the population through the comic industry. because the golden age, nobody actually knew about the holocaust when they were writing the whole “punching nazis” schtick. the comics were wartime, jingoistic and often racist propaganda.

and yet!! we’re still doing it. thanks to some escapist tradition that actually does more harm than good. because we actually know about the holocaust, we have the internet and the ability to push ourselves to research. and we don’t. and i think tbh, that is much worse. that the people with money and platforms just don’t care.

it’s in other media too, mostly movies.

chaplin got it right, he said he would’ve never made the great dictator if he knew about the final solution like we did today.

spielberg couldn’t include nazis in indiana jones after making schindler’s list and im pretty sure he said he disowned it, but. it looks like everyone decided to shit on that because of nostalgia.

jojo rabbit was originally adapted from a novel where the protagonist was an unrepentant scumfuck HJ who gaslit, controlled and raped the jewish woman hiding in his house. and for some reason, people hate the novel. why? because it rightfully doesn’t give them the cozy feelgood feeling that the film did. it rightfully portrays a brainwashed child who never got out, was never interested in getting out and grew up to be, you guessed it, a fucking nazi. those jojo rabbit viewers were actually looking forward to this before they got the hard reality. who the fuck in their right mind would ever consider nazism ‘feelgood’?

and i think that’s another thing we need to get in our heads especially with radicalization. tw isis execution being brainwashed as a kid is not funny, it’s not childish or anything to make fun of, and it’s nothing to make a wes anderson movie about. you are being exploited and taken advantage of by people who know you’re angry about things beyond your control and they are molding you and you believe everything. and the ensuing trauma if you ever get out, ends up being a bitch because your brain was still developing and now it sticks for the rest of your life. yeah try taking that in, taika.

so. by all means. wise up and kill the living swastikas wherever you find them. it could be anything, but. get rid of it. because we are going to be so fucked up as humanity otherwise.

#the holocaust#nazi germany#antisemitism#propaganda#us politics#politics#dogwhistling#extremism#troythings gets political#superman#kal el#clark kent#lois lane#johnathan kent#overman#martha kent#dc comics#comics critical#mcu critical#anti mcu#tw genocide#tw antisemitism#tw holocaust#tw nazism#tw gore#tw isis#anti arrowverse#arrowverse#dammit

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

i found a post i think you wrote about snk and nazism and i wanted to hear more from you if thats okay? is it definite hes a fascist nazi supporter? i dont want to believe it but. and he still made eldians the victims right? so it shows no matter what or why the marleyans should not have done what they did. and anyone with promarley views are bad guys right?

i think i just dont want to believe it can be taken in the pronazi way because this story means alot to me and i dont know what to do. but i think a both sides are wrong thing doesnt work here because of how they showed it with nazi and holocaust imagery. showing suffering people as just as bad doesnt work. but i understand bad people can come from anywhere. at the same time we support eldians for being the holocaust victims right? im confused now. im sorry for the bother. please help?

No problem, It's always good to look at your favorite stories critically, if you have the energy! That said my point of view is just one of many.

I think it's pretty evident by some things yams has said that his viewpoint is a questionable at best. For example a tweet about how korea had it best under japanese imperial rule (spoiler: they didn't) and his statement of how admirable the ww1 admiral he based pixis on was (another spoiler: he wasn't). Also the combination of German ww1/ww2 military inspiration and the norse mythology inspo are hardly coincidential imo. So I simply don't trust that dude, which might taint my pov. I think he isn't necessarily a nazi supporter in an active sense of running around yelling "Sieg heil", but imo his work is tone deaf at best in quite some regards.

I think especially now, so late in the manga it shows that the story is about getting rid of oppressive hatred, which is a great message! But the way this is done is still pretty... oof. Yes, Marley is bad, but they are not the enemy in the way the story is built. They are a plot device. Eren or by extension Ymir are the enemies (in the sense of that those who are portrayed as the people we are supposed to be rooting for are fighting against him). And that Halucigenica thing, whatever is up with that lol So we're not fighting fascism, we're fight the one who wants to fight fire with fire but who's still from "our own" (in a very interesting sense as Eren was also introduced as the protagonist).

The enemy is basically their own heritage, therefore the problem is not Marley, they are just a symptom, a byproduct if you will. We don't have any prominent characters that have promarley views that could serve as bad guys (correct me if I'm wrong) except the warriors, who are also not the bad guys at this point because they joined forces with Mikasa and friends. Plus they are also Eldian, so actual Marlean people only get very little place in the story in general.

If Ymir lifts the curse of the titans the message we get is that the way to undo oppressive hatred is to denounce your heritage. It says it was actually the Eldian's fault that they were mass murdered and the way this won't happen is if they stop being Eldian alltogether. If the plot ends and ymir doesn't lift the curse we probably get a story of unity through a common enemy which is also horrible, cause that would mean the victims need to forgive their opressors, simply for peace's sake. But that's of course speculation, cause we don't yet know what the last chapter will bring. But in regards to the eldian/Marley conflict I kinda don't see a good way to resolve it (tho i might stand corrected)

Jewish people have pointed out how they feel that the connection of jewish coded characters with the titans is pretty antisemitic. On the other hand some have also said they don't think so. As a gentile I'm not one to weight in on that, but as a German, who's been sensitized to white supremacy dog whistles I definitely see where they are coming from in pointing out antisemitic undertones of the series (see my pinned post).

I think this doesn't have to be a reason to drop the series. I also follow it through, because it's a huge part of my live and i wanna know how it ends. It does have beautiful characters and dynamics. Some parts of the story telling are greatly done. And as I said this is simply my view on it.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

lol i got mad about a thing reylos said. shocking. (tw: nazism, fascism)

just saw a ridiculous post about how people who talk about the first order as being nazis are ignoring history and disrespecting jewish people and let me tell you

that the only reason I didn’t write this on that post is because I think the op is probably jewish and also a kyle ron/reylo fan and lol well. I don’t need to be told I can’t have an opinion on this or that I am attacking them. this is nothing personal, except that reylos have a history of being racist and dismissive about fascism, and so I am honestly shook that someone could be so disingenuous. lol oop that was personal.

if you know anything about film history, you know that george lucas got his inspiration for the empire’s look, and also for certain shots of the rebels, from nazi propaganda made by leni riefenstahl, specifically triumph of the will. (guys don’t go looking it up if you haven’t seen it unless you have a strong stomach because it is really, really disgusting). now, that is more or less what happens when you have a guy who is a student of film history make a movie about, you guessed it, a band of rebels fighting an imperial force but in space. george lucas also put a lot of politics into star wars, specifically anti-fascist messaging. this is like the most basic argument people make when dealing with right-wing fans of sw. this is what we’ve all said to some dumbass white guy who got mad about rey or finn or poe. I would bet that some reylos have also had that conversation, since they care about rey (I guess, although that might be too strong a word; they certainly don’t care about shipping her with a guy who tortured her lol but I digress).

jj abrams took what was already overt fascist imagery from the empire and turned it up to eleven for the first order. this is actually why I found the inclusion of POC as first order OFFICERS (not low level workers Bodhi or stolen baby stormtroopers like Finn) to be kind of fucked up, because it diluted the narrative. do not come at me with some idiotic YESS MORE BLACK IMPERIALS YESS because I am just not here for that brand of idiot representational pinkwashing(? this is a term we use for putting gay shit on monstrous corporate/imperial shit to seem more progressive but it might not be the right term for this).

if you look at the og trilogy, every single imperial officer is a posh white british man, and while I am sure that was partly because diversity was not really something george seemed mindful of, it was also a deliberate thing. like, they clearly wanted to evoke an image of imperialist, and yes FASCIST, rule. this is not that hard to understand so don’t be fucking obtuse just because you like kyle ron or reylo. not that I believe that the intent of the creator is the end all, be all, but in this case it does matter.

yes the anti-alien biases were mainly a product of legends, but I am pretty sure it is also implicit in the original movies because there are no aliens to be found in imperial ranks, and they are everywhere in the rebellion. and yes, I can understand why this might be offensive because you don’t need metaphors to understand why the nazis were bad, and yet. maybe, sometimes, you do need to give people a metaphorical understanding of things they haven’t experienced. and humans have a notoriously difficult time understanding large numbers - so maybe, a visual example of what the fuck genocide might seem like is... idk, helpful for kids? alderaan being death star’d might not be actual history, and it might not represent what jewish/romani/etc victims of the nazis experienced, but it IS chilling. personally I think that tfa did a better job with its death star knock-off because we actually saw people in their last moments. alderaan’s destruction can be rightfully criticized as too distant, since we only see leia’s response, and not what it felt like on the ground. but undoubtedly this is a fictional representation of fascist, imperial might - and all the destruction that comes with it.

it isn’t just visual, and of course the star war isn’t real and no real alderaanians were harmed in the making of the movies. duh. it’s a metaphor, an allegory. like idk who these reylos are kidding, acting like people who criticize you guys for stanning a fascist fuckboy don’t understand that these are just fiction.

the REASON I get mad about reylo and about kyle ron stans, is because nothing exists in a vacuum. NOTHING. not a damn thing. the dumbing down of stormtroopers and imperial ideology (vague though it might be) is actually how Disney gets away with marketing t-shirts with stormtrooper helmets on them to little kids, or like idk how people have convinced themselves that ben solo is just misunderstood and damaged, and not a thirty-year-old man who has made a deliberate choice to commit genocide. his so-called abuse (which we only get to see in a comic? like I’m sorry do better with your sob story) is no excuse for at best being silently complicit in genocide, and at worst actively campaigning for it.

I think there are good critiques that people make about saying the empire is nazism, because obviously this is fiction. you cannot have it both ways. you cannot say that it is anti-fascist when you are arguing with right-wingers who didn’t get that message, and then turn around when people say your fave is at best neutral on genocide (lol) and say we can’t talk about how he is a fascist.

I saw someone say something like, no one calls darth vader a fascist. LMAO yes we fucking do. now I will be the first to admit that anakin gets a lot more empathy, and part of that is because he is a more beloved character with more nuance than kyle ron. and decades of lore. but also because he didn’t grow up a privileged son of a princess, he grew up enslaved and because of his traumas he went right-wing. which does in fact happen. but yeah, darth vader had to die at the end of rotj for a reason - because no one would forgive him for the crimes he committed against the galaxy. it’s tragic because he had the potential to do great, and he redeems himself by killing the emperor, but approximately no critic of kyle ron would ever say that anakin skywalker deserved to go free and live without consequences for his actions.

if I have more sympathy for him, it is because the movies gave me reason. not because he’s hot. or idk a bad boy.

and after the racist abuse that john boyega got from KYLE RON AND REYLO stans specifically, if I were them I would shut the fuck up about how offended you guys are about calling him a fascist or a nazi. you can like your bad boy wet dream if you want, and you don’t have to even like that people think he is a fascist, and you can deny all you want all of that OVERT FASCIST IMAGERY that jj abrams put into tfa, but it’s there, and we don’t live in a vacuum, and I am not here for people dumbing down cultural phenomenon.

redemptions arcs are great! I believe in rehabilitative justice, and I agree that there is a bit of gatekeeping on who gets to be redeemed in stories. but rehabilitative justice isn’t just like you let people who do bad shit get away with it, it is a long process wherein offenders have to do some serious work on themselves. it is not easy. it is not fun, doesn’t end in sex with daisy ridley. and in many ways, it might be harder than doing hard time.

but I also don’t think we get to just... rehabilitate the lead officers who are complicit in war crimes without dealing with what they’ve done, that is how I feel about george bush, and yes, that is how I feel about kylo ren, no matter how much you try to woobify him. because that is what society already does - we let the monsters at the top of the system get away with war crimes and murder and rape, so maybe we should fight that kind of narrative in fiction, too.

we don’t live in a vacuum.

#i have jewish family members and i am not here for this bullshit#like who you like if you must#but that was some cognitive dissonant shit#fascism tw#nazism tw#war crimes tw#i mean these are pretty vaguely mentioned but still#cait got mad#shocking

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

History thought: I see a significant parallel between the Aztec empire and Nazi Germany: both took a pre-existing nasty part of their region’s culture (human sacrifice in the case of the Aztecs, racism and eugenics in the case of the Nazis), doubled down on it in more-or-less the most horrific possible way, and built an entire imperialist ideology and state apparatus around it.

Context for that: I don’t know much about pre-Columbian MesoAmerican history, but from reading 1491 and 101-level histories about the Aztecs I have a strong impression that Aztec human sacrifice practices were intensified a lot as part of the process of their society becoming an empire, with a new imperialism-friendly theology providing the justification. Human sacrifice seems to have been part of the cultural background of pre-Columbian South and Central America, the Inca did it too, but I have a strong impression that the Aztecs were unusual in how central human sacrifice was to their state and how much of it they did. I see a parallel between that and what happened with racism and eugenics in Nazi Germany.

Thought proceeding from that: therefore, arguably, the best modern analogy for Cortez’s conquest of the Aztecs would be evil aliens invading an alternate history Nazi victory timeline Earth.

Thought also proceeding from that: I wouldn’t be surprised if other pre-Columbian South and Central American societies have something of an undeserved bad reputation just because the Aztecs are one of the three pre-Columbian South and Central American societies the average person has heard of. Like, imagine that scenario where aliens invade and conquer a Nazi victory timeline Earth; now imagine the history books the aliens might write about pre-conquest Earth society hundreds of years later, imagine what their historical fiction and popular history books about pre-conquest Earth society might look like, imagine what their equivalent of PBS documentaries about pre-conquest Earth society might look like, imagine their pop-cultural memory of pre-conquest Earth society. Imagine how all that might be skewed by a Europe-dominating Nazi empire being one of the three or four pre-conquest human nations the average alien is familiar with.

Speculative fiction concept: a fake history article or book or book review article from a universe where aliens conquered a Nazi victory timeline Earth in the 1950s, written hundreds of years after the conquest in a time when the alien empire has been reformed into a sort of Star Trek United Federation of Planets type set-up and Earth is a thoroughly culturally assimilated member of the aliens’ federation and the aliens have come to regret their earlier imperialist ways. The book or article is basically discussing the political and cultural context in which Nazism existed and its place in that context, with a subtext that it’s trying to show that the Nazis were unusually murderous and cruel within that context and it’s trying to debunk a common historical misconception that pre-conquest Earth culture was just like that.

Speculative fiction concept addendum: possible bonus material: examples of the sort of media that book or article would be reacting against, e.g. an elementary/middle school level textbook chapter about Earth history where there’s a handful of paragraphs about pre-conquest Earth history, a bunch of writing about the military campaigns to conquer the United States of America and the Nazi empire written in a queasy tone of being low-key ashamed of the brutality of the conquest but also horrified at how nasty the Nazi empire was (the conquest of the rest of the planet is described a short footnote paragraph), and the rest is the history of Earth under the Empire and then as a member of the Federation.

Speculative fiction concept addendum: bonus material about uncomfortable implications: some writing about anti-colonial movements on Earth during the late Empire period. Mentioned in passing is that Earth anti-colonial movements often tried to reclaim the Nazis and their iconography (in much the same way that supporters of Hispanic and American indigenous rights in our world often try to reclaim the Aztecs). These attempts at reclamation included revisionist histories that suggested the Nazi empire wasn’t really as bad as conventional histories claim, “the Nazis were brave warriors who heroically resisted the conquest and you should take pride in this noble heritage!” takes, and adoption of Nazi iconography as symbols of resistance, liberation, and cultural pride. Ironically, many of the people “reclaiming” the Nazis in this way were or are people whose ancestors were victims of the Nazis; when Human/alien has been the most important racial distinction for centuries “you’re a Russian Jewish autistic trans gay, the Nazis would literally have wanted to kill you for five different reasons and probably did kill, enslave, torture, and/or rape your ancestors!” tends to get lost in the shuffle of “I’m going to take pride in the cultures of my ancestors that the conquerors spent centuries trying to wipe out!” Uh, yeah, this is totally the sort of thing I could see happening in this scenario, but I think it’d probably be kind of uncomfortable to write or read, probably not something to talk about in much detail unless one can handle it with a sensitivity I’m not sure I’d be capable of.

#history thoughts#writing ideas#alternate history#cw: nazis#I feel like this post should have a content warning but I'm not sure what

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Political rant to gain some courage

Once you stop really caring how other people feel about you or your interests, you do become happier.

I get it, being into social justice and removing biase is a good thing and all but not everyone was raised to be completely unbiased and politically correct.

I can go on for days about how privilage truely dose shape the mind but its like your irredeemable if you have one flawed belief on here. People will tear you to shreds, sometimes rightly so but its like they dont know that people do change and they need to be pushed to in a manner that dosent call for their head if they arnt completely woke.

Im white, i recognize this gives me a privilage over colored people. I dont hate myself because im white and im proud of the heritage i have. Im proud of the many european places my ancestors came from and their culture. I may not approve of the actions commited by the government in those place all the time but i understand a whole country cant stand behind something realistically. I know being white dosent make me better than colored people and i advocate for equality for all races. I dont condone violence, missionarism or imperialism.

I have german roots, i enjoy learning about and participating in german culture and its events. I live near a city that has alot of German immigrants in it and is one of the only american cities that wide-spread celebrates Oktoberfest and has a german name. This dose not make me a fucking nazi. This dose not mean i condone the invasions the german military has done in the past aginest jewish, polish, greek etc. People. For fucks sake i have polish immigrant great aunts,uncles and cousins.

I mentioned having a partially german last name and heritage and had a proudly jewish account call me suspicious on the bases of " having an anti-semitic heritage".... What. Are you seriously gonna dehumanize, assume and dismiss an entire culture,country and millions of people based on the actions of one man in charge of the government for a short time?? The actions of his friends and the orders given to soldiers that upheld them? By that logic we can throw just about every single country in existance under the bus for something. This dosnt mean i dont recognise the holocaust, it also dosent mean i condone the active mistreatment jewish people still recieve today. I actively advocate aginest anti-semitism and nazism.

However, If i was an actual nazi per what that account assumed of me, i would be advocating my own death. Im gay, trans, autistic, mentally ill and have polish heritage... I also dont have blue eyes or blonde hair.... And based on the story of how my mom's side of my family came to america... You are spitting in the face of my great grandmother who survived a nazi invasion in holland...holy shit...

Its like people on here dont understand you can be partically privilaged on one side and not on the other and still be a decent person.

I have heavy german heritage and yet i dont comment on jewish issues other than to support the Jewish community.

Im white and yet i dont comment on colored people's issues other than to support the colored community.

I get it, if a privilaged person is over stepping their boundaries, call them out on it but advocating hate towards a whole group of people isnt more progressive or even intelligent.

The goal shouldnt be the oppressed minority attempting to put the privilaged majority in the place of oppression. It dosent teach them anything, your more than likely going to fail and you've gone from victim to bully pretty fucking quickly.

The goal should be equality and fair ness. Instead of this end all be all radical craziness push the scale to the opposite side shit, we should remove the whole fucking scale and everyone stands on equal footing.

No race is better than any other race. No gender is better than any other gender. No country is better than any other country. No religion is better than any other religion.

This isnt even centrism by this point. Its just equalism.

Honestly, being a minority isnt a get out of jail free card for you to harass one person on the actions of others who happen to be apart of it, wether or not by choice.

Example? Sure.

Im transgender. If terfs and transphobes are to be believed, im automatically doomed to rape, murder and torture other people. There are trans people who have raped murdered and tortured other people.But.. Umm.. Ive never raped, murdered or tortured another person... Also cis people have a privilage over me on account of me being of the oppressed minoriy of cis vs trans. Thats over stepping a boundary as most transphobes are cis.

I will call out a cis person or a trans person( looking at you truscum and transmeds) who are openly transphobic. I may call them names like cissy or other things.

I dont call my cis gf a cissy.

I dont call innocent cis people cissy.

What other cis people have done in the past dose not mean that the cis person i am interacting with now is transphobic.

I get it, being trans means you have to be on defence incase the cis person infront of you is openly and/or violently transphobic but its also not fair to assume they are. Yes, this may be considered catering to the majority but its also respectful of other people in a realistic setting.

If i accused a random cis person, who happened to be an aggressive trans ally, of being transphobic just on the basis of being cis. They'd be outraged and rightly so. Accusing someone of being inherently bigoted is... Ignorant.

If i was accused of being inherently racist just on the fact of being white, id be outraged.

If i accused a random binary trans person of being enbyphobic, they'd be outraged.

Any way, though this post has been all over the place, ill give some last concluding thoughts.

If you think your better than someone else who is part of a majority, simpley because you are part of the opposing minority. Your not woke, your not progressive and your really honestly just a dick.

Also being oppressed on one axis dose not erase your privilage on another and opression and privilage dose not exist in a vaccum. No one privilage trumps the rest and no one oppression trumps the rest.

Lastly, dont expect a fucking award for being a decent and respectful person to minorities. Woo hoo, your white and not racist, laa dee fucking da. Your straight and defended a gay person from someone homophobic like any decent person should, you want brownie points? The minority you protected will more than likely thank you but you shouldn't expect more than that.

Thats about it and if your gonna give me shit for pushing for real equality rathur than real superiority( so it pushes out the satire and fun of things like gay superiority or the down with cis bus cause its a joke). You should really reevaluate the last three conclusions of this paragraph and addres your victim/superiority complex, thanks!

Now have a cute gif of zenyatta laughing

#political rant#racism#homophobia#transphobia#addressing the ins and outs of oppression and privilage#tw rape#tw murder#tw torture

1 note

·

View note

Note

I share your desire for complexity but if they wanted to make a grey political story LF would not have invoked neo nazi imagery with the FO. Any time a creator does that it’s a shorthand for b&w conflict bc it’s basically the only b&w conflict we have irl. Individual chars can be redeemed but I have zero doubt that the moral-political axis will remain unchanged in ix. If LF wanted us to question sides their villains would be based on a different analogue.

Ok, so first of all I may get a little foul-mouthed here but tbh to a person raised and living in a country which had dubitable pleasure of being stuck between Third Reich and USSR, has never been full of innocent tolerant lambs in their own right and is currently dealing with the freshest wave of extreme right - because mind you, they’re not neo-nazis, since nazism is only limited to Germany, at least according to them - politicizing GFFA is a laugh but really a cry. So if that’s a sensitive or in any way triggering issue to someone, I apologize and please, just stop here.

I dunno what to tell you, anon. That OT didn’t stray away from Riefenstahl style for rebels too?

That resistance uniforms aren’t exactly immune to their own connotations?

That the broomstick boy has a pose straight from a soviet propaganda poster?

That the story we’re getting basing on the esthetic is so mindnumbingly stupid, useless and self-congratulating Disney-LF would have saved a whole lotta money if they just gave the audience paid oral pleasure or sold ice cream to those below 18 instead of making the sequels and the effect would have been essentially the same?

Like, really, what’s the f*cking point of this whole trilogy if it’s there to reassure us bad guys™ are still irredeemably bad and there is no other conceivable evil? Because this is what the neo-nazi imagery essentially boils down to when you don’t apply real world politics - fo are neo-empire first and foremost and since empire had nazi imagery, they have neo-nazi imagery. They’re basically the same villains as the ones in OT - which either means that New Republic hasn’t dealt with them as they should have - or DLF really has no better idea than to lick my centro-leftist ass, because as far as making a difference by scaring actual neo-nazis is concerned, make no mistake, they won’t f*cking care about the “jewish propaganda”, they’re romantic rebels on a crusade against an evil globalist empire (unfortunately that video has no english translation and I don’t really want to give it too many views but if someone is interested I can direct them to a video of polish right-wing publicist interpreting TFA. essentially, he gets he’s fo. and has zero f*cks to give). Having fo gratuitously vanquished will accomplish nothing but cheerlead on people who already are against neo-nazis and personally I’m mistrustful of flattery in any form and for any reason. You could argue it will influence the future generation - yet somehow after empire got vanquished we still have the same problem.

And before anyone asks and what would the reintegration accomplish I openly say nothing as well, simply provide better drama which I insist should be a priority here.

A story in which we get essentially the same villains as the last time is the story in which individual redemptions, let alone individual bendemption, are the one thing that won’t happen, because this puts us back at the end of RotJ, especially now that we know Vader wasn’t the only redeemed imperial. And this basically translates to Disney-LF admitting they have nothing interesting to add to SW and are openly going to milk my money banking on nostalgia and stroking activist ego - in which case I admire their honesty but would rather have the ice cream. TSequels’ ending will either have to feature some form of reintegration of numerous fo members - even if that reintegration is imprisonment, prison is still part of the society, unlike exile - or have each and every one of them blown to smithereens - or admit that it was dramatically useless. I’m nost sarcastic here, if someone can give me good dramatic justification for the trilogy which ends in exactly the same place as the previous did, I will be only grateful, because I know what I’m suggeting is controversial - but it’s a result of longish analysis of potential courses the story can take.

But ok, I also don’t want to sound like I completely dismiss the esthetical implications. By moral ambiguity I definitely don’t mean that the tables will turn a 180° and fo will turn out to be the heroes and resistance villains all along. What I do hope to see is darker and lighter shades of grey, translating to resistance crossing some moral barriers and fo members maybe not being indiscriminately brainwashed evil zombies - which is simply an amplification of what we’ve already seen about rebels and empire in Rouge One and Solo.

I suppose the save middle ground is the stormtrooper rebellion, though again, personally I’d be delighted to see Mitaka’s happy ending and wouldn’t really mind Hux’s epic redemption through taking care of stray cats in the galaxy. The stormtroopers already have a personalized advocate in form of Finn, are very widely aacknowledged as kidnapped and brainwashed children, have their original rather than nazi outfits, and have essentially been there since the clone wars only the new republic decided to put them on the same shelf with the empire. Funnily enough, I’ve actually seen speculations that involve the stormtrooper rebellion but no bendemption - and if thinking we’ll only get individual redemptions is misssing the rythm, this attitude is missing the melody. The individual and political subplots in Star Wars aren’t simply running along, they’re exact mirrors of each other:

few hours after the Tuscan massacre Palpatine receives emergency powers

Padme gives birth to the twins on the same day that she co-created the rebellion

Anakin willfully becomes Vader on the same day that the republic became the empire in thunderous applause

Vader’s husk burns to release Anakin’s spirit simultaneously with empire getting scored the major defeat releasing republic’s spirit

essentially, the republic rebels wanted to restore was technically empire all along, just as the father Luke searched for was Vader all along

Kylo kills Han hours after FO destroys the Hosian system.

This isn’t some ubermeta analysis, it’s just something a sensitive viewer perceives and non-sensitive still likes without conscious recognition.

In summary - I just can’t look at Kylo Ben and see a broken abuse victim and then indiscriminately shrug my shoulders at fo and stormtroopers - nor can I bank on stormtrooper rebellion and assume Kylo’s an irredeemable psychopath.

#asks#star wars#bendemption#villain discourse#redemption discourse#tw: nazism#tw: neo-nazism#stormtrooper rebellion#sequel trilogy

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw you posted a thing about the Germans killing Namas and Hereros in Namibia between 1904 and 1908. I would just like to talk about how the British invented the Concentration Camp during the 1899-1902 2nd Anglo-Boer War on Afrikaans people (or Boers). You can read about it on Wikipedia if you type in “Emily Hobhouse” or “Lizzie van Zyl” (the photos of her are shocking to see). Also, the Americans invented Zyklon B (same gas the Nazis used) to use on Mexicans (Posting for historical accuracy)

While your information about British South African concentration cams is accurate your information about Zyklon B is both inaccurate and misrepresentative. It was invented by Bruno Tesch, Gerhard Peters and Walter Heerdt for the German company Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung mbH. I suggest From Cooperation to Complicity: Degussa in the Third Reich by Peter Hayes if you are interested in the history of corporate chemical giants and the Holocaust. It’s use by the US government on the Mexican border was for delousing clothing (which along with disinfesting ships, warehouses, and trains was the labeled use). You can find the story inRingside Seat to a Revolution by David Dorado Romo.

It was very racist and very likely killed or harmed many Mexican immigrants but we’re talking about a time when we were much less generally knowledgeable about the health affects of bathing people in pesticides (this picture is DDT).

Your use of “the Americans invented Zyklon B to use on Mexicans” is inflamatory because for most people they don’t know that Zyklon (grades A, B, C, D, and E) were commercial pesticides not invented by the Nazis for killing humans. The American government wasn’t trying to exterminate the Mexican farm workers they used Zyklon B on. They were didn’t spray the people with the chemical in gas chambers as might be implied by your choice to pair the information with a discussion of German concentration camps in Africa. They sprayed the workers clothing. Did people very likely die from exposure to the chemicals in their clothing? Almost certainly. But that wasn’t the intent. Anymore than killing people was the intent of the use of DDT.

Moreover the story of British Concentration Camps during the Boer War while horrifying did not have the same purpose that the German camps in German South West Africa did. Many people died in those camps but the purpose was to guard a civilian population away from places they could provide material support to the Boer armies. Did people die? YES. Are the pictures disturbing!? YES. There are many many horrifying aspects of colonialism. This is a picture from the Madras Famine of 1877.

I recommend the books Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World by Mike Davis; King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa by Adam Hochschild; The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazismby Casper W. Erichsen and David Olusoga; andImperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya byCaroline Elkins.

If you are interested in the horrors of American Eugenics on the Mexican border I suggest Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America by Alexandra Minna Stern.

If you are interested in how race and public health intersected in American government policy Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines by Warwick Anderson.

(because you should get your information on these kinds of things from better sources than WIKIPEDIA).

We should understand the impact and horrors of Colonialism for their victims but what we should not be doing is equating ALL colonial horrors with the Shoah. The differences here are that the Imperial Germans were trying to exterminate the Namas and Hereros and the Nazis were trying to exterminate the Jewish people. The British were NOT trying to exterminate the Boer population. The Nazis were explicitly using Zyklon B to kill people. The American government was using Zyklon B (which they did not invent) to kill lice.

Since you are so interested in historical accuracy.

#when a historian gets mad#Anonymous#i'm also suspicious that this is trying to normalize nazis#by claiming they didn't do anything different than other powers

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

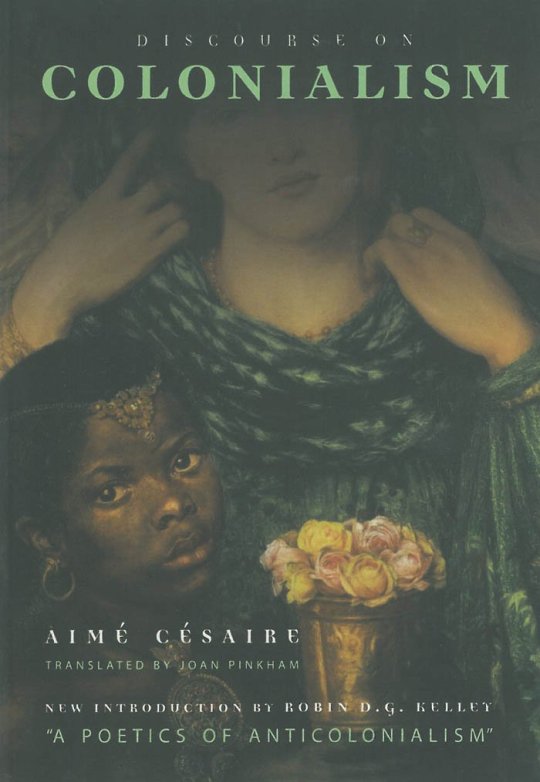

Aimé Césaire’s “Discourse on Colonialism“

❍❍❍

The publication of "Discourse on Colonialism” in 1955 was simultaneous with the Bandung Conference, which is considered a major event in the history of decolonial thinking and acting. Publication of this short book paved the way for Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. Through this process of evolution, postcolonialism was matured from its Marxian context to a broader and more encompassing discourse. Fanon was a student of Aimé Césaire. Although Fanon is associated with postcolonialism the most, it was Aimé Césaire who paved the way for Fanon, Said, Spivak, and Bhabha. Aimé Césaire’s early engagement with movements such as Negritude, Surrealism and many anti-capitalist organizations led to his political career at Martinique with the support of the French Communist Party (PCF). His intellectual career is intertwined with his political career which lasted until 2001.

In terms of methodology, Césaire is very much a Marxist, yet sometimes he is using Nietzschean (pre-postmodern postmodern) methods concerning science and universalist scientific thinking. He criticized the European and especially French humanists who theoretically justified colonialism and imperialism. The best example that he mentions in the Discourse is Renan, a racist humanist. An idealist philosopher who paved the way intellectually for colonialism. The burning quote that is extracted from Renan is probably the most racist quote I have ever read in academic texts and is taken from a book title La Refonne intellectuelle et morale [The Intellectual and Moral Refound].

Césaire also criticized M. Mannoni’s psychoanalysis thinking (especially regarding colonialism) as well as Bantu philosophy and its inherent racism, which was aimed to monopolize all the glory for the European race. However, in the Discourse, Césaire describes the European humanists as those “chattering intellectuals who are born stinking out of thighs of Nietzsche”. We also have to remember that Nietzsche seriously attacked Renan as comedian of the moral ideal in “On the Genealogy of Morality”.

Reading classical texts by Césaire and Fanon we realize that the history of postcolonial theory is as much entangled with psychoanalysis as it is with Marxism. This is however from an era in which not only intersectionality but the whole movement of poststructuralism and gender studies didn’t exist. The universities and especially the French philosophical establishment were stuck in universalism and scientific objectivity of pure knowledge.

Césaire is criticizing M. Mannoni’s existentialism. He believed that M. Mannoni was using existentialism to blame the victims of colonization rather than the colonizers. M. Mannoni perceived French government as moderate in solely arresting the Madagascan deputies during the Madagascans revolts of 1947. Maud and Octave Mannoni were a French psychoanalyst couple who were later associated with Lacanian circle. Octave Mannoni spend some time in Madagascar and returned to France after WWII. He was inspired by Lacan and published some psychoanalytic books and articles. Similar to Aimé Césaire’s criticism of M. Mannoni, Octave's book "Prospero and Caliban: The Psychology of Colonization" was criticized heavily by Fanon:

“[O.] Mannoni argued that all colonization is based on a relationship between psychological types: the authoritative white man and the dependent black one. Fanon began to see how European models of psychoanalysis located all psychotic conditions in individual psyches while ignoring very real material conditions – such as racism or colonialism. Fanon himself would observe that it was the lived experience of the blacks that induced psychotic behavior.”

"In another psychoanalytic interpretation, Mannoni argued that when the native, black man dreams of guns, they are essentially phallic images. Fanon is outraged at this interpretation of the gun as a mere symbol. One cannot see only symbolism when the threat is very real, he believed. Fanon argued that the rifle in the hands of the colonized (in his dreams) is no Freudian symbol, or phallic metaphor – it is a real rifle he is dreaming of and one which can injure the black body (Black Skin: 79). One cannot lose sight of the real and be trapped within such fancy symbolism.” (1)

Similar to Nietzsche, Fanon shifts the debate from the individual psyche (conciseness) to a social relation. "The Oedipal is not, in the case of the Africans, rooted in the family (as Freud famously proposed), but in the social.” Pramod K. Nayar writes in his book on Fanon.

Today, we know that racism is not always as simple as a binary of black/white, yes/no, rather it’s a huge spectrum of cultural understanding-misunderstanding by the privileged whites that leads to hate and violence. Racism is not only the skinhead white nationalism of Neo-Nazis in Europe and KKK in the United States or the neo-fascist Islamophobes in India. Theoretical racism was and still is present in many universities and institutions around the world. In the context of post-war Europe, Césaire identified racism and Nazism as something within each and every European. He reminds us that its always easy to blame Hitler, Rosenberg, Jünger, and others. As Hitler is someone who made the white man look bad, who humiliated the white people in the most immediate way. He generated the killing and barbarism that was reserved for the non-whites.

“Yes, it would be worthwhile to study clinically, in detail, the steps taken by Hitler and Hitlerism and to reveal to the very distinguished, very humanistic, very Christian bourgeois of the twentieth century that without his being aware of it, he has a Hitler inside him, that Hitler inhabits him, that Hitler is his demon, that if he rails against him, he is being inconsistent and that, at bottom, what he cannot forgive Hitler for is not crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the coolies of India, and the blacks of Africa.” (2)

Europe is Moving Toward Savagery

In 1955 Césaire challenged the notion of White Supremacy, asserting that there is nothing superior in whites. He had argued that all non-Western societies were superior to European ones. (3) Césaire talked about the boomerang effect of colonialism. When the “civilized” people want to forcefully civilize the natives they in return become the savages through this forceful violence. He argues that the Idea of barbarism is a European invention. He places ‘Africa’ as the binary opposite of ‘Europe’. He comes up with the iconic mathematical equation Colonization = Thingification, which as its predicate we can discern the archaic colonial justification of colonialism; Christianity = civilization and Paganism = savagery. We all have seen the recent video of a white drunk pastor who is attacking and insulting the black hotel workers in Uganda. That incident can be another visible example of the continuation of this mentality.

Simultaneously, as a Marxist, Césaire analyzed capitalism and bourgeois societies which were very immediately observed in those days of post-WWII. In the Discourse, he asserts that both the Nation and Man is a construction, a bourgeoisie phenomenon. On page 43 he asserts: "I am talking about millions of men in whom fear has been cunningly installed, who have been taught to have an inferiority complex, to tremble, kneel, despair, and behave like flunkeys."

Césaire criticizes knowledge production as well as ethnography as something that only West studies and talks about the rest of the non-Western countries. The ending of the Discourse could have been timelier if he was using the same ending as the interview with René Depestre:

“I remember very well having said to the Martinican Communists in those days, that black people, as you have pointed out, were doubly proletarianized and alienated: in the first place as workers, but also as blacks, because after all we are dealing with the only race which is denied even the notion of humanity.” (2)

Bib.

1. Nayar, Pramod K. Frantz Fanon. s.l. : Routledge, 2013.

2. Césaire, Aimé, Pinkham , Joan and Kelley, Robin D.G. . Discourse on Colonialism. Aimé Césaire, Joan Pinkham, Robin D.G. Kelley : s.n.

3. Loomba, Ania. Colonialism / Postcolonialism (New Critical Idiom). s.l. : Routledge , 2005 (first published 1998).

______________________

0 notes

Text

The Force Awakens: Nazism and Holocaust Imagery, a case study

The language of American cinema is full of Nazi imagery. They have become stock villains, symbolic of tyranny, and a convenient shorthand for evil. Villains who are not Nazis are often draped in Nazi-esque imagery, Nuremberg-style pageantry, or uniforms made to resemble Nazi uniforms. American filmmakers love to say “these people are evil because they are like Nazis.”

This has a cheapening effect on the memory of real Nazi atrocities. This use of Nazis and Nazi-esque villains almost never has any connection to the real evils committed by Nazis. Instead, it’s a reflection of the popular American conception of the Nazis as the “bad guys” that the American “good guys” fought and beat in World War II. The American movie and television industries feed off of, and also feed into this collective view of the Nazis, which flattens them down and glosses over what actually made the Nazis so dangerous and terrible, while allowing American audiences to give themselves a little pat on the back for being against Nazis, making it that little bit easier for them to put themselves in the hero’s shoes, saving the day the same way America saved a helpless and prostrate Europe and the Jewish people. This narrative ignores of course that the Americans were far from noble “good guys” who saved the day, and the Nazis were a very specific kind of evil, that Americans were (and more importantly are) not immune to.

This general American ignorance about Nazis and the Holocaust, and worse, the unawareness of this ignorance, leads to many problems, most commonly a lack of ability to distinguish Nazi-esque ideas when spouted by someone not wearing a Nazi uniform, and vulnerability to different forms of Holocaust denial. The most extreme form of Holocaust denial, the idea that the Holocaust didn’t happen, or happened on a much smaller scale is sadly all too common, but not the only form this general ignorance about Nazism can lead to. One more common form is the deracialization of the Holocaust. From the common, yet completely absurd idea that Nazis hated people with brown hair, often with the corollary that Jews were more likely to die because they were disproportionately brown haired, or that blond haired Jews were spared, (one only needs to look at photographs of the Nazi elite to see plenty of brown hair, and blond hair was anything but protective to the Jewish and Rromani targets of Nazi genocide) to the idea that Jewish people were targeted for “their beliefs”, the American understanding of the Holocaust often leaves out the racial nature of the Nazis’ crimes and ideologies, and ignores the way in which the Nazi regime was built on racist lies that scapegoated the Jewish and Rromani people as the ones to blame for Germany’s ills, and as inferior and decietful races, not as a matter of religious belief or even culture, but as a matter of blood.

Related to the deracialization of the Holocaust is the idea that the Nazi ideology arose from out of nowhere and “took over” an otherwise civilized Germany, ignoring the old and extremely well-established European tradition of antisemitic and anti-Rromani violence and mass-murder, and the thoroughly entrenched antisemitic and anti-Rromani ideas in European cultures and societies, including Germany, that Hitler and the Nazis fed off of. This makes it so much easier to view the Nazis as interlopers and corruptors than as an understandable and potentially reoccurring political ideology that can adapt itself to local bigotries.

Contrary to what might be expected, the overt us vs. them, good guys vs. bad guys, Good Americans (and allies, just remember the Americans are the important ones) against the Nazis narrative of World War II and the Holocaust also exacerbates the most extreme form of Holocaust denial that I mentioned above, the denial that it happened or was as large as every credible historian accepts. This is because at some point, a significant number of people run across the hard truth that the United States is nowhere near as virtuous as our grade school American history textbooks would have us believe, or as dedicated to living up to our ideals. For some people, raised on this good guys vs. bad guys view of the war, it’s easier to flip the narrative to make the Americans the bad guys (and therefore the Nazis the good ones) than to do away with the narrative entirely. Still others take the normal, even natural path of assuming that good and evil is some kind of zero sum game, so if America is less virtuous than they were taught, the Nazis must be more so. Sadly this isn’t true, the fact that the Americans were far from flawless doesn’t mean that the Nazis didn’t industrialize mass murder while acting out an ideology that mandates genocide.

I don’t hold Hollywood responsible for the popular American misconceptions about the Nazis and the Holocaust. I lay those primarily at the feet of the appalling state of history education in the United States, including the history of the Holocaust. Instead, American film reflects the viewpoints of filmmakers who have themselves absorbed these misconceptions, and produce movies that reinforce them.

This is the film-making tradition that gave birth to the Star Wars original trilogy, and as much as I love Star Wars, it does epitomize this approach to depicting Nazi symbolism in film. The Empire are bathed in Nazi aesthetic, from their uniforms, to the name of the stormtroopers, to imperial officers with strongly Germanic names. Yet while the empire is undeniably evil, it isn’t really evil in the same way as the Nazis. Although the EU took the Nazi symbolism, as well as the lack of visible women or non-humans in the imperial ranks, and extrapolated discriminatory policies towards nonhumans, and even their enslavement and exploitation, as well as rampant sexism in the imperial ranks, this is nowhere to be found in the movie itself, an we have no evidence to suggest that these bigotries are in any way foundational to the empire and to imperial philosophy the way Nazi bigotries were to their ideology.

Interestingly, we do see a genocide depicted onscreen in the original trilogy, when Alderaan is blown up. However, the destruction of Alderaan is again in no way foundational to imperial ideology. The Emperor didn’t come to power on the force of galactic hatred for Alderaanians. Also, and this is crucial, the destruction of Alderaan has no real emotional weight, except to show us how evil the empire is. The only Alderaanian the audience knows is Leia, and she survives. It isn’t mentioned after A New Hope, and it just isn’t meant to be that important to the viewers. This ties in pretty closely with other portrayals of genocide in film and fiction, including the portrayal of the Holocaust, in which the victims are rarely the focus of these stories, and are almost never meant to be figures the audience can identify with. These tragedies are turned into a backdrop, and the victims into people for the heroes to either save or fail to save.

The prequel trilogy expands on the story of the empire, showcasing Palpatine’s rise to power and toppling of the Republic. Again another genocide is shown, that of the Jedi, and this one has more emotional weight. But Palpatine is no Hitler, although they both once held the title of chancellor. He plays the long game, coming to power slowly, and slowly, carefully using the pretext of war to sap the protections the Republic had in place against someone like him seizing power. Hitler did not. He was almost certainly not emotionally or intellectually capable of that kind of manipulation. Palpatine also carefully stokes anti-Jedi sentiment. Unlike Hitler, who drew on existing antisemitism and anti-Rromani bigotry in the German population, and who made it the centerpiece of his ideology, Palpatine knows he has to eliminate the Jedi because they pose a real physical threat to him as a possible Sith Emperor, and works hard to make the subjects of the new empire ignore and forget the slaughter of the Jedi instead making it central to his purpose. Again, Nazi imagery in the empire is shown to be only a veneer over a very different kind of evil.

In fact, as I discussed a little here: [Link]. The Galactic Empire and Palpatine’s rise to power are much more reflective of American axieties during and shortly after the Nixon administration, and during the George W. Bush administration respectively. Palpatine’s empire is a dark mirror for what the United States might look like as a totalitarian regime and how it could get there. The use of Nazi (and also Soviet) imagery allows American audiences to project those fears off of themselves and onto an outside enemy. This not only cheapens the popular memory of Nazi evil, it also gives American audiences an out, excusing them from grappling with the Americanness of Palpatine’s empire.

The Force Awakens inherited its Nazi imagery-saturated villains from the earlier Star Wars movies. The filmmakers involved had several choices as to what to do with this inheritance. Palpatine’s empire was gone. They had three choices. They could ignore the Nazi-esque elements of Star Wars’ past imagery and attempt to forge a new visual language, they could continue with Nazi-esque design elements and villains who aside from aesthetics didn’t actually resemble Nazis much at all. Or they could take that Nazi imagery and actually do something with it.

The Force Awakens opens with an act of Nazi-inspired mass murder, the Einsatzgruppen style slaughter of the village on Jakku. To most Americans, the Holocaust was the death camps and their gas chambers. However, millions of Jewish and Rromani people in Eastern Europe died at the hands of Nazi killing squads called Einsatzgruppen. These mobile killing squads would go into a village, round up all of the Jewish and Rromani people, take them to a mass grave, line them up at the edge, and shoot them. It’s this imagery and not the camps that the slaughter on Jakku evokes.

This scene alone is a tremendous break with the movie-making tradition I outlined above. Not only does it use an actual example of Nazi-like crimes instead of simply Nazi aesthetic, it also shows the villagers fighting back. They shoot at the stormtroopers, and yet are slaughtered anyway. During the Holocaust, many Jewish and Rromani victims and survivors fought as resistance fighters, or partisans, or took part in uprisings in the ghettos and camps. The American narrative of the Holocaust portrays the victims as going meekly to their deaths, but in reality many of them armed themselves and fought to protect themselves and their communities, and died anyway.

This particular narrative, of the victims of the Holocaust and other genocides as helpless victims who did not fight back is so strong that @lj-writes mentioned to me that she completely forgot the villagers had fought back on Jakku until re-watching the scene, something she mentions again here: [Link].

The other extremely unusual thing about this scene is that we see it happening. Usually if this kind of slaughter of a village does take place, the audience finds out about it when the heroes stumble upon the burned out wreckage, as for example Luke does with his aunt and uncle’s farm. Instead, not only do we see it happen, but two of our heroes are there to participate, one as a captive and survivor, the other as a stormtrooper refusing to kill. This act of mass murder is shown as emotionally important to these two heroes, as a major part of their story. Simply put, Finn’s refusal to murder for the First Order, refusal to go along with Nazi-style atrocities, is central to his storyline.

Equally unique is the fact that not only do we see the slaughter itself, but even though there are two central characters present, one of whom has a storyline intimately bound up in this moment, the camera instead shows us the final act of slaughter from the point of view of the people being fired upon. In this moment, we the audience are asked to identify with the victims, and see through their eyes. Depictions of the Holocaust and other genocides so rarely ask us to identify with the victims. It’s uncomfortable. It’s frightening. It’s far easier to make them seem passive and somehow less like humans and more like objects, exactly the way their murderers saw them. Yet, The Force Awakens, at the very start of a sci-fi adventure movie asks us to do exactly this.

The second scene that is critical to understanding the way The Force Awakens uses Nazi imagery for the First Order is the Nuremberg-style rally on Starkiller base. In this scene, General Hux is transformed from a smug, sinister but bland bureaucratic cog into a thundering, charismatic, foaming terror, screaming out his articulation of the philosophy behind an act of mass murder. Along with the speech itself, shot in glorious and disturbing tribute to Triumph of the Will, we are given beautiful and also horrible scenes of that mass murder, and the destruction of planets full of people, forced to watch as their death comes for them. We are given an immediate association between Nazi-style rhetoric, and this act of genocide. Nazism leads directly to mass death.

It’s significant I believe that the director of The Force Awakens, and all of the scriptwriters are Jewish. They bring this Jewishness, and their own perspective on the Holocaust, unique, obviously, from that of Gentile America to their roles as filmmakers, and I believe it shows most profoundly in their treatment of Nazi and Holocaust related imagery and the whys of Nazi-esque villainy in the movie. A huge part of why this movie and this portrayal of the First Order was so refreshing for me as a Jewish woman is that the views it draws on treat Nazi atrocities as something much more real and relevant, and treats Nazis not as monsters that brave Americans fought, but as a real and present danger, and treats its victims as human beings who might have been us. This perspective comes from belonging to one of the peoples the Nazis tried so hard to eliminate, and from being forced from childhood to imagine ourselves in the victims’ place.

This is Nazi imagery in filmmaking done right, done respectfully and done effectively. This use doesn’t simply draw on Nazism to code our villains as villains. It doesn’t simply say without substance that our villains are evil because they are like Nazis. Instead The Force Awakens says these people are like Nazis, and this is what Nazis do. And then it shows us what people should do when faced with Nazis and their ilk, fight it, don’t accept it, refuse to participate, and resist no matter the cost. The Force Awakens turns the one-sided standard use of Nazi imagery in American film back on itself, making a statement about Nazism as well as a statement about the movie’s own villains. And in doing so, it turns the Nazi imagery draping their villains from a cliche into something that strengthens and enriches the movie’s storytelling.

143 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It all starts with the children and with white women. Black Genocide wouldn’t work without white women, who are the hidden key to it. You know, we say genocide is a male military thing, men’s deeds alone: In Germany the gestapo in uniforms, with submachine guns, ordering all the Jews out of their houses into trucks and trains. There’s never any German women in the picture. But that’s not how genocide started, only how it ended.

In Germany the campaign to wipe out the Jews began against the children. German women began organizing during the 1920s to stop their children from associating with Jewish children. Mothers warned their children to stay away from all Jews. Jews were characterized as not only 'subhuman' animals, but very dangerous criminals and perverts who wanted to get pure white children into their hands. It was white women’s mission, the Nazis said, to protect their families by keeping the 'Jew' away.

Shoppers boycotts of Jewish stores and demands that Jewish children be sent to separate schools were conducted by German women. The movement to push Jews out of every part of German life began with children in the home, and as it gathered strength it extended to the schools, to blocks and then neighborhoods, to rural towns and small cities, then to workplaces.

Only then did the government begin to strip the Jewish people of first legal rights and then of German citizenship. The Jewish reservations (death camps) were not the first but the last stage in a complex genocidal machinery.

Violent attacks and terrorism against Jews, at first isolated incidents, grew in number over the years. Nazis shouted that they were only protecting German women and children, that Jewish criminality and animal-like behavior forced good Germans to defend themselves.

The idea of violence against Jews began to be accepted as normal, just part of life. For years the police pretended to be trying to protect Jews (just like the u.s. police), although it could be seen that many more Jews and revolutionaries were being arrested than Nazis.

After 1933 the police and the Nazis merged, with beating and killings of Jews being done under police protection. It wasn’t until nine years after that and 20 years after it all began, when the Jewish community had been already pushed out, dazed and ground down, in 1941, that death camps could begin.

While German revolutionary women died trying to stop the Nazis, most German women either supported genocide or said that it was men’s affairs and had nothing to do with them. This was the position adopted by the middle-class white feminist movement.

Striving for equal rights with their men was the program of the women’s movement, which argued that German feminists shouldn’t be distracted from their own concerns by what it defined as male political issues (genocide, fascism). And armed struggle against imperialism was viewed by the women’s movement with horror, as unfitting their view of the gentle, nonviolent nature of civilized white women (kind of like the delicate Southern belle and her mate, the slavemaster).

Nazism was indeed a male movement, in which even Nazi women held a very subordinate position. But it was dependent upon women. It was women who made genocide possible. Not only were women men’s invaluable supporters, loyally taking care of their Nazi husbands and raising Nazi children, but they played the frontline role in the early stages of genocide. Without women’s help, active and passive, the Nazis could never have justified genocide as necessary for the defense of the white family and children.

And how are amerikkkan women different from those German women?