#Igbo Writing System

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nsibidi: The Ancient Symbolic Proto-Writing Script of Nigeria's Ekpe Society

Nsibidi, also known as nsibiri, nchibiddi, or nchibiddy, holds a significant place in Nigerian history and culture. Developed by the Ekpe secret society, this intricate system of symbols or proto-writing is believed to have originated in the southeastern part of Nigeria. The Nsibidi symbols, numbering several hundred, are classified as pictograms, although some researchers have suggested that…

View On WordPress

#African History#African Proto-writing system#African Writing System#Igbo History#Igbo Writing System#Nsibidi#West African#West African history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

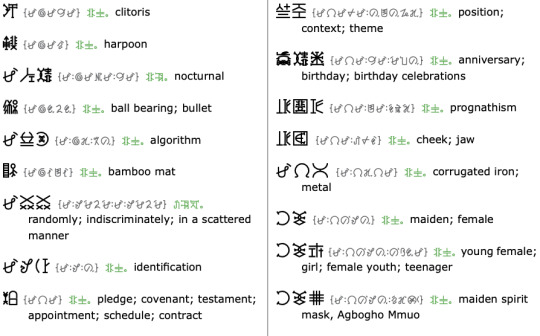

A full list of Nsibidi and Akagu Sources

Nsibidi Dictionary 2012 Nsibidi_Dictionary Download Nsibidi Radicals (Full character definitions) nsibidi_radicalsDownload Neo Nsibidi Evolution 2014 NeoNsibidiDownload West African writing systems (history, development and evolution) West african writing systems(history, development and evolution)Download Nsibidi Typology and…

View On WordPress

#download nsibidi pdf#igbo writing#learn nsibidi#nigerian writing system#nsibidi#nsibidi documents#nsibidi pdf#nsibidi pdf download#west african writing system

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

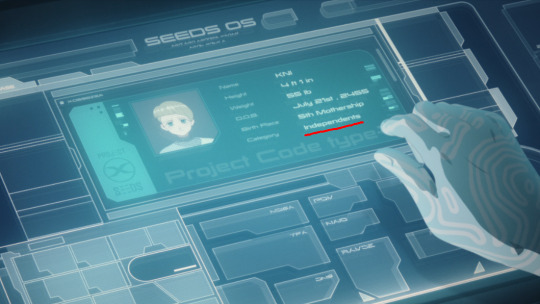

Its been roughly two years since Trigun Stampede ended and I think I figured out the whole "Nai" vs "Kni" spelling thing;

Throughout all 12 eps his name is spelled "Nai" in the subtitles but "Kni" in the computer system and I don't think either spelling is a mistake.

TRIMAX SPOILERS!!

The main thing that confused me about the name thing was that the data entries existed AT ALL, Rem made it very clear that she wanted to hide the fact that Vash and Knives were plants so why on earth would she input them in the system LABELED as plants??

Because she didn't.

If Rem didn't make those data entries then who did? It sure would be really convenient if there was another person that we know ended up waking up and meeting the twins while they were still on the ships huh?

Oh WAIT!

While we haven't gotten the scene of Conrad meeting the twins in Stampede we know for a FACT he did because when Knives finds him after the fall he calls him by NAME and acts relieved to see him even going so far as to run to him like he was going to give Knives a hug;

I think Conrad was the one to input the twins into the Project Type-T data base and that Rem never even knew he did this.

'but why would Conrad do that?'

Because Conrad wanted to study them and never actually saw them as more then new test subjects.

The thing is that I don't think Conrad actually feels remorse for what he did to Tesla. He doesn't regret killing her because she was a child who was sentient and felt pain-

He regrets killing his most valuable science project.

Right now we only have one photo of Tesla when she was still alive and she was clearly around the same age of the twins when she finally died from the abuse she suffered.

Tesla looks so empty while Conrad looks content, happy and proud.

Conrad never felt an ounce of doubt about what he was doing to Tesla when she was alive, it was only after the abuse was too much and her body failed did he suddenly start feeling regret.

He killed his test subject before he was done with it and that's what he really regretted.

So when he met the twins he realized he had two more chances to get to study an independent and made their data entries;

The reason why it's spelled "Kni" is because Conrad was trying to spell a name he'd only ever heard, he couldn't just ask Rem how to spell it so he based the spelling on what he thought Rem named him after; his KNIVES. Conrad thought it was supposed to be a shortened version of knives and thus wrote is as Kni.

But it ISN'T.

His name actually IS spelled Nai.

If you look up the name Kni pretty much nothing comes up, Nai however-

The first culture I found Nai attached to was African; In Swahili it means 'purpose' or 'aim' while in Nigerian Igbo it means 'mother' or 'motherhood' which fits Knives perfectly.

But I wanted to check to see if Nai had a Japanese meaning and the closest I found was Chinese origins that's commonly used for girls with Japanese roots;

The name Nai is made up of two elements, Na and I. Na has multiple meanings such as green, vegetables, many, and APPLE TREE-

NAI BASICALLY MEANS APPLE TREE

HIS NAME MEANS APPLE TREE

Honestly I would have been content considering this a crack theory based on a spelling error but knowing that Nai is a name that actually has a meaning that can be considered FORESHADOWING???

There's literally no way this was an accident.

I also think the person who did the subtitles was told how to write their names because I can't find Elendira being a previously existing name outside of Trigun and I'd assume they'd need to be told how to spell the names but I can't find proof of that so-

If you got this far thank you so much for reading because I figured this out like a couple of months ago and have been freaking out over it ever since.

Sources:

https://www.momjunction.com/baby-names/nai/

https://namediscoveries.com/names/nai

#trigun#trigun stampede#trigun maximum#millions knives#I fucking hate conrad#literally everything would have been fine had they just thrown that man out an airlock

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOP 10 AFRICAN TRIBES/ETHNIC GROUPS THAT ARE GLOBALLY KNOWN.

(In no particular order)

1) Zulu ?? South Africa – The Zulu tribe is popular outside Africa. They’ve been featured in music, documentaries and movies. Shaka the Zulu was a warrior king whose popularity is well spread. Famous Zulus, Lucky Dube, Nasty C, black Coffee etc.

2) Yoruba ?? Nigeria – The Yorubas are globally known for their history, culture, art and literature. Fela, Wole Soyinka, Wizkid, Davido, Tiwa Savage, David Oyelowo, John Boyega, Anthony Joshua etc are a few Yorubas who have taken their culture to the world. The Yoruba culture has been featured in many Hollywood movies.

3) Masai ?? Kenya – The Masai are perhaps one of the most documented tribes in Africa, with alot of documentaries shown about them and books written about their culture.

They are known for their traditional clothing and hunting skills

4) Hausa ?? Nigeria – The hausas are very popular. Often known as the Igbos of the North, The richest black man in the world Aliko Dangote is Hausa along with his brother from the same state Kano Abdulsamad Rabiu (BUA). Their culture has also been well written about and have featured in a few Hollywood movies including the Amazon prime series were a woman was seen eating Tuwo shinkafa.

5) Igbo ?? Nigeria – The Igbos are undeniably known world wide. Chinua Achebe wrote about the Igbo culture alot. They are known for their history, culture and literature.

The popularized the kolanut and palm wine through books, movies and music

Chinwetalu Ejiofor, Zain Asher, Ckay, Flavour, Chimamanda, phyno, P-square are Igbos who have taken their culture to the world. Igbo are known in Nollywood movies.

6) Swahili ?? Tanzania – This tribe have phenomenal spread their language in East Africa and a few central African nations.

In the 70s, their language was part of the African-American black pride movement been pushed forward.

7) Edo/Bini ?? Nigeria – The Binis are perhaps the culture in Africa with the most famous artworks outside Egypt.

Binis are known for their history, culture and art/architecture.

The famous Benin bronze, ivory and brass artworks are known globally. The country Benin republic gets their name from them. Benin art and culture have been featured in Hollywood movies including black panther. Many Nigerian cultures have roots in Benin. The bronze mask of Queen Idia is perhaps the most famous mask in Africa and one of the most famous in the world. Popular Edos are Kamaru Usman, Rema, Odion Jude Ighalo, Victor Osimhen, Dave, Sam Loco Efe etc.

Asante Ghana – This tribe are known for their history and culture. Popular American hip hop artist was named after this tribe Asante. Their Kente is perhaps the most popular African attire outside of Africa and were known to be masters of the gold craft.

9) The Fulani – This nomadic tribes are known for their history and culture. They are predominantly in West Africa and are found in 18 African countries. Most In Nigeria ??

Popular Fulanis or people with Fulani ancestry are Muhammadu and Aisha Buhari, Tafawa Balewa,

10) Berbers/Amazigh – They are predominantly found in North Africa. They are predominantly found in Morocco ?? and Algeria ?? They known for their use of silver silver. Their culture and history well documented and have a unique language and writing system that traces back to ancient Egypt. Books are currently being written about them including a book titled salt by Haitian-American Pascaline Brodeur.

Disclaimer: Every African tribe and culture is beautiful, unique and important. No one culture is more important than the other. This only highlights tribes known outside the continent overall, this doesn’t mean there aren’t other cultures that aren’t known.

PLEASE YOU CAN ADD AND TELL US ABOUT YOUR TRIBE.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legendary Creatures: Ghosts

A belief in a spirit or soul that exists after a person or animal dies goes back as far as the written record and likely has origins in prehistory. Funerary practices seem to indicate a belief in the continuation of life by burying a person with objects that were used in daily life as well as practices like ritual feeding or clothing of ancestors. Since the belief in a continuation of some kind after death exists in so many cultures, we know that this belief goes far back in human history, perhaps even before modern humans expanded out of Africa. Many experts think that the awareness of mortality gave rise to a belief that some part of humans continues beyond death.

In cultures that didn't develop writing, or those whose written history was destroyed by colonizers, it's difficult to know what they believed about ghosts, spirits, or what happened to a person after death. We rely on more modern records by people who might view them as 'exotic' or might genuinely respect them and more recently by the people themselves. With that in mind, let us explore what we know about what people thought about ghosts in antiquity around the world.

Africa:

Among the Igbo people, man is both physical and spiritual in nature and the spiritual is eternal. The Akan see humans as having five parts, the Nipadua (body), Okra (soul), Sunsum (spirit), Ntoro (character from the father), and Mogya (character from the mother).

By Shyamal - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5710972

The most well known in Africa is likely the Ancient Egyptian mythology because they wrote down their belief systems. They believed that a person was made of eight parts, the Khet (physical body), the Sah (spiritual body), Ren (name/identity), Ba (personality), Ka (double/vital essence), Ib (heart), Shuyet (shadow), Sekhem (power/form). The collective name for the spirit of a dead person once they entered the afterlife is the Akh. This idea was likely well developed early in the Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BCE). One of the ceremonies performed by priests after death, which was thought to happen when the Ka left the body, was to open a person's mouth to release the Ba to join the Ka, which creates the ꜣḫ (akh).

The afterlife was thought to be like the the mortal life but more resembling the journey of the Sun as it descended into Duat (underworld), meeting the mummified body of Osiris. Often, the mummified body was addressed as 'Osiris'. The ba, depicted as a featureless shadow as it left the body at dawn, would go about its work during the day and return to the body at night, as they believed the Sun returned to Osiris at night. Those who completed some form of quest or task were thought to become stars. The Book of the Dead, which was called the Book of Going Forth by Day by the Ancient Egyptians laid out how to avoid a second, permanent death. As written in the tomb of Nekhen of the Eighteenth Dynasty had written on his tomb as translated by James Peter Allen, American Egyptologist, 'Your life happening again, without your ba being kept away from your divine corpse, with your ba being together with the akh … You shall emerge each day and return each evening. A lamp will be lit for you in the night until the sunlight shines forth on your breast. You shall be told: "Welcome, welcome, into this your house of the living'.

During the Twentieth Dynasty (1189-1077 BCE), the idea of a roaming ghost, which could cause nightmares, guilt, or illness, began to be recorded. These arose when tombs weren't taken care of by prayers and offerings. The ghost could also be asked for benefits or to inflict punishments by making specific prayers and offerings.

As other areas of Africa didn't really have written records that we can decipher or find today, it's difficult to know what was the difference between gods and ghosts.

Mesopotamia:

Ghosts of the dead were known as gidim (𒄇) in Sumer, which became eṭemmu in Akkad. This word means something like gig (to be sick) and dim (a demon) or maybe gi (black) and dim (to approach). Sumerian is an agglutinative language, so different syllables can mean different things and were written differently and could be written differently when they were joined together and their endings were changed.

By Gennadii Saus i Segura - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=126738193

The memory and personality of the person went into the gidim, which was created at the death of the person, which then went to the Irkalla, the underworld and realm of Ereshkigal (𒀭𒊩𒌆𒆠𒃲), 'Queen of the Great Earth', goddess of the underworld with her husband Nergal (𒀭𒄊𒀕𒃲). To reach Irkalla and Anunnaki (𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾), the gods of judgment who gave the laws of the dead and assigned fates to the dead. In addition to this, the sun god Utu would visit the neatherworld nightly and punish those who harassed the living and share offerings with the forgotten.

Offerings to dead relatives of food and drink by surviving family was said to comfort the dead. The forgotten would suffer and be able to cause physical and mental illnesses on their relatives who don't remember them if there are relatives that remain. Those who died in ways that their body was unrecoverable would have no ghost.

China:

By Unknown artist, Ming Dynasty - http://www.鹿山會館.tw/EastCapital/viewthread.php?tid=419&sid=ZzXrihhttp://www.shanximuseum.com/collect/topic/shuiluhua.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=138953197

Among the Chinese, with the widespread culture of ancestor worship, they believed that ancestors could be reached through a medium for aid in many areas of life. The still celebrated Hungry Ghost Festival (Zhongyuan Festival in Taoism, Yulanpen Festival in Buddhism) is also a part of ancestor worship as it's believed that on the day of the festival, spirits are able to cross from the underworld to the mortal world. Ghosts in Chinese cultures have many terms, generally related to guǐ (鬼 in Mandarin) such as guilao (鬼佬) for a ghost man, which is used as a pejorative for foreigners. Even nightmare (魇 yǎn) is related to the idea of ghosts.

Part of the belief encompassed in ancestor worship is the concept of the spirit being comprised of yin and yang, which was called hun (魂) and po (魄). Po, the yin component, is related to the grave and hun, the yang component, is related to ancestral tablet. When the person dies, the spirit divides into three, the po component remaining with the grave, the hun component going to the ancestral tablet, and the third component goes to judgment. The hun and po components can only survive as long as they are remembered and nourished. Eventually, the hun and po move on to the underworld, a neutral place, though the hun visits heaven first. Chinese ghosts are able to affect the mortal world, even to the point of murdered people could exact revenge on those who killed them.

Taoism became the majority religion during the Han dynasty (206 BCE- 220 CE) and Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty (681-197 CE). For a long time, these two belief systems were accepted together, syncretism (the mingling of beliefs) leading to a more complex system of beliefs with the ancestor worship of Taoism and traditional Chinese religion blending together with the belief in reincarnation found in Buddhism to create something unique with ten types of ghosts, one of which, the hungry ghosts (饿鬼, èguǐ), can be further divided into nine types.

Mediums were called mun mai poh (simplified 問米, traditional 問覡) which means 'ask rice woman' and is a pun for 'spirit medium' with different inflections. because the people coming to her would bring a cup of rice from their home so the ghosts could find and identify their family members. The medium helps to find out what the ancestor needs for the family's request (winning the lottery or getting into government housing). These needs are then burnt as paper effigies.

Japan:

By Sawaki Suushi (佐脇嵩之, Japanese, *1707, †1772) - scanned from ISBN 4-3360-4187-3., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5510196

Japan's concept of a spirit or a soul is called a reikan (霊魂) that enters a holding place until they recieve a proper funeral and funerary rites so they can then join their ancestors. Those who are murdered, die of suicide, don't have a proper burial, or are consumed by revenge, love, jealousy, hatred, or sorrow, the reikan becomes a yuurei (幽霊 meaning faint or dim soul or spirit), which can interact with the physical world if they are fueled by strong enough emotion. These spirits remain until proper rites are performed for them or they are able to resolve their emotional issue. The yuurei tend to haunt only at the 'midtime of the hours of the Ox', which is 2:00-2:30am and tend to be bound to certain locations.

Another type of ghost, one who had stronger emotions and are capable to causing physical harm in the mortal world, is the onryou (怨霊) which means 'vengeful spirit' (alternately wrathful, hatred, resentful, ruthless, envious, dark, fallen, or downcast). There are three notable people who became onryou so revered that they became known as the Three Great Onryou of Japan (日本三大怨霊), Emperor Sutoku (July 7,1119-September 14,1164), Taira no Masakado (early 900s-March 25, 940), and Sugawara no Michizane (August 1, 845-March 26, 903) who reportedly caused a lot of death and destruction after their deaths because of the resentment and anger they died with. They were elevated to kami (gods) and a Shinto shrine in an effort to appease them.

India:

By Roboture - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18747046

In India, the Sanscrit word bhoota (भूत) usually referred a to the ghost of a deceased person. Exactly what they are, though, varies by region, community, and time period. They are usually seen as those who were too hung up on something that keeps them from moving on through to the next phase in existence, which also varies by tradition. The belief in bhootas is an important and deeply ingrained part of the culture of the Indian subcontinent

Bhootas avoid touching the earth because the earth is held to be either sacred or semi-sacred, have feet that face backwards, are able to shape-shift though they tend to be human shaped most of the time, cast no shadows, and speak with a 'nasal twang'. There are some bhoota that haunt houses, which then become 'bhoot bangalas' (bhoot bungalows), usually where they died or are emotionally attached to. Stories with bhootas in them tend to select the traits to create the most suspense. Bhootas are capable of haunting milk, to the point of seeking it out. If someone drinks that milk, they can become possessed, which is another frequently used trope in the stories.

To protect themselves, people could use water, iron, or steel at hand since bhoota fear these things, as well as the scent of brunt tumeric, the fibers of an herb called bhutkeshi (bhoota's hair), holy figures, and the sprinkling of dirt.

Kingdom of Israel and Judah and diaspora:

By Ephraim Moses Lilien (1874–1925) - Book of Job, appearing in Die Bucher Der Bibel, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19447366

In the Hebrew Bible, there is a type of ghost called the owb (אוֹב) that's mentioned a few places. It relates to both mediums, with their connection to the dead and necromancy, such as when King Saul consults with the Witch of Endor to summon the spirt of Samuel, the prophet. Other places, it relates to shades, the spirits of those in the underworld.

In Jewish mythology and folklore, there is another type of ghost, that called in Yiddish a dybbuk (דיבוק), which comes from the Hebrew verb dāḇaq (דָּבַק), which means 'to cling' or 'to adhere'. These spirits are believed able to possess someone and to be the soul of a dead person. This type of ghost is first written of in the 16th century. The mezuzah (מְזוּזָה a specially inscribed parchment kept at doorways) is supposed to protect against dybbuk, a well hung one actually preventing a dybbuk from forming.

Greece:

By Eumenides Painter - User:Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2007-07-21, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2453109

The ancient Greeks viewed ghosts 'as a vapor, gibbering and whining into the earth' as Homer wrote in the Odyssey and Iliad in the 8th century BCE. By the 5th century BCE, in classical Greece, ghost became something that could haunt people or places, for either good or ill, and were capable of interacting with the mortal world. They also performed ceremonies and sacrifices, including the pouring out of drinks, to make sure the spirits of the dead, which they viewed as shades, would not return to haunt their families. Shades (σκιά) were usually the spirit of the dead in the underworld and could be speak through oracles and could have divinity confirmed on them, like the Oracle of Ammon did to Hephastion, 'by far the dearest of all the king's friends' when Alexander the Great was 'inconsolable' after he died.

Rome:

By Henry Justice Ford - http://www.postershowcase.info/i1862812.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11733112

Ancient Romans saw ghosts as a method of revenge by way of a curse being written on pottery or lead placed in a grave. They believed that ghosts could haunt locations, such as when Pliny the Younger wrote around 50 CE about the Stoic Athenodorus (who lived 100 years earlier) renting a house in Athens that was haunted. He deliberately sat up writing late. He saw a ghost wrapped in chains, which he then followed outside until the ghost pointed out a particular site. Athenodorus excavated the location and found a skeleton bound in chains. Once the skeleton was buried properly, the haunting ended.

One of the first skeptics to write their lack of belief was Lucian of Samosata, who wrote in the 2nd century CE. He wrote about Democritus (who lived about three hundred years earlier) lived outside the city of Abdera in Thrace deliberately to prove that ghosts didn't exist, even in the face of practical jokes, such as the young men of the city dressing up in 'black robes with skull masks'.

Central America:

By Vassil - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17841631

Aztecs believed that after death the soul moved on to one of three places, Tlālōcān (a Paradise reigned over by the rain deity Tlāloc), Mictlān (where the dead travel with Xolotl through nine levels, passing several challenges) and the Sun. Fallen warriors and women who died in childbirth became hummingbirds.

The Maya believed in a pair of collective ancestors, the '(grand)fathers and (grand)mothers' which inhabited particular mountains where offerings were meant to be given.

The Purépecha believed that monarch butterflies symbolized the movements of the dead to their afterlife as they migrated to their winter habitat in what is now Michoacán, near where they lived. Theyalso had a story of the ghosts of a princess Mintzita and her fiancé go to a particular cemetary every Noche de Muertos as the Spanish called it. On that night, now, people float candles on Lake Pátzcuaro as well as others. Michoacán is even now called el alma de Mexicho (the soul of Mexico).

#ghosts#ghost#ancient egypt#igbo#afterlife#akh#gidim#gui#guilao#reikan#yuurei#onryou#bhoota#owb#dybbuk#shades#ancestor worship#legendary creature

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Note

Hi so I’m an English major who, thanks to the atrocious American education system, has had very little interaction with other literature. Any suggestions for where to start? I tend towards the darker stuff, but I love classics.

here are some book recommendations for (mostly) non white authors:

freshwater by akwaeke emezi: a young nigerian woman named ada battles lifelong with various iterations of her own self, these multiple personalities shaped by deities rooted in Igbo cosmology and myth. a difficult read; personalities/POVs bleed into each other, introspection precedes plot and there is a TON of trigger warnings (dm for info). nevertheless, harrowing, powerful study of the long-standing politics of trauma, faith and sexuality.

running in the family by michael ondaantje: after a bizarre dream leaves him shaken, ondaantje decides to journey home to sri lanka on a quest to piece together long-buried stories about his family, especially his deceased father. this book is a fictionalized memoir; history and folklore often overlap, but it's good throughout, rooted in the bittersweet warmth of lost culture and nostalgia in 1970s sri lanka. 100/100: made me ugly laugh and then reduced me to tears.

susanna's seven husbands by ruskin bond: one simply doesn't read only one ruskin bond book; I don't ideally recommend one specific story. yet this is probably one of his darkest novellas yet, narrated by a north indian boy who grows up next door to a beautiful, enigmatic biracial heiress with a long line of dead husbands and a property brimming with mysteries. it's chock full of deadpan humour and really wtf moments written in the classic bond vein. don't watch the trash movie, the novella is a gem!

kitchen by banana yoshimoto: following her grandma's death, a japanese woman moves in with two unlikely friends. I never thought potted plants, phone booths and refrigerator lights would make me want to scream into my pillow for 1 hour but oh, well. cooking!! kitchens!! bowls of katsudon to warm your soulmate's hands!!!! urban loneliness!!! poignant look into intimacy and grief!!! accidentally falling in love!!! murakami wishes he could write like this!!! (research triggers though!)

china dolls by lisa see: see's books are all beautifully atmospheric portraits of chinese women and their experiences in different points of history. I recommend china dolls, which is about three young asian american women navigating the world of nightclubs in 30s/40s San francisco. twisted and complex female relationships, a nuanced look at the exoticisation and perilous lives of asian americans during WW2, and of course, compelling storytelling.

the neapolitan novels by elena ferrante: charts the life of two intelligent young girls, best friends lenu and lila, from childhood to adolescence to maturity, starting from 50s Italy, against the backdrop of their violent, eventful neighbourhood in naples. equal parts chaotic academia + bildungsroman. mixed feelings about this one because while I liked the concept and characters, the translation felt pretty mediocre to me and many turns of phrase were lost. also someone lied to me and said it's sapphic goldfinch, which, no, it's not :(

reading lolita in tehran by azar nafisi: gorgeous memoir about the author's time as an academic woman in 70s Iran: her fight against the regime, her expulsion from the uni, creating a secret girls-only book club at the height of the leftists/student led 1978-81 Iranian revolution etc. The book is divided into phases like lolita, austen etc where parallels are drawn between the themes in the western texts and the lives of the Iranian girls in the book club. can't recommend it enough.

the interpreter of maladies by jhumpa lahiri: from a couple trying to rekindle their marriage through a storytelling game to a little american boy's affectionate bond with his bengali babysitter, this really cutting and impactful collection of short stories deal mainly about the expatriate indian experience in US. jhumpa lahiri can keyboard smash and it would still create pulitzer prize winning prose.

bunny by mona awad: a young woman pursuing an MFA in creative writing, is inducted into the unsettling, seemingly saccharine world of a sugary cliqué called the bunnies. it's like a cocktail blend of moral ambiguity and voyeuristic opulence (the secret history) meets absolute feral campy horror (ahs coven), bitchy bratzy vibes + dark academia (literally what's not to love) and it gets well.....unhinged. someone on this site compared it to donna tartt and stephen king getting hammered and punching out a collab novel and tbh I agree :D

the kite runner by khaled hosseini: pretty sure everyone has already read this but idc. it's a story about afghanistan, a story about family and friendship, a story about loving and creating stories and flying kites and how sometimes history crawls out of muddy empty alleys to stick a knife into your back. I know not many people like hosseini on tumblr but honestly this novel just made such an impact on teen mimi, I can't not recommend it. heavy trigger warnings, dm for info.

sister outsider by audre lorde: if you are looking to begin with reading on intersectionality audre lorde is always a great place to start. this is a collection of essays, speeches and vignettes about lorde navigating her multiple coexisting and inextricably bound identities as a lesbian, a Black woman, an activist, a cancer survivor and a poet. this is a masterpiece of a collection, and I particularly adore the sections on the uses of anger and an open letter to mary daly.

love in the time of cholera by gabriel garcia marquez: so many people walk into this book expecting a genuine tender romance or something and that's why they get disappointed. my dude, it's ggm. this book is about the lush world of colombia in the late 18th century, the perils and ridicule of obsessive love, it's infused with magical realism and fascinatingly grotesque imagery and a rich array of flawed characters, but,, it's not your average slowburn coffeeshop romcom so like.?? idk why people misread it so!

I hope you'll find something to your liking from the handful I recommeded. additionally, please consult this list for non-western classics (it's pretty normcore; personally don't care for some of the picks under india but it's a good place to start with all the basics), this list for indigenous literature and this list for indian academia and classics.

#mimiwrites#book recs#book recommendations#bookblr#literature#books#dark academia#poc dark academia#chaotic academia#indian academia#india#asian literature#akwaeke emezi#audre lorde#elena ferrante#lisa see#ruskin bond#studyblr#history#culture#text#essays#long post //

3K notes

·

View notes

Link

This popped up as a recommendation to me and I gotta say, it is a really eye opening read. We often ascribe veganism as a “white rich kid” thing when it really is not. There are some things in here I don’t agree with (I don’t think there’s any real science behind “alkaline” diets), overall it’s a good message. It’s definitely true that calling things like dairy products a “dietary staple” is racist because lactose intolerance is pretty high in a majority of the world.

Food is political, and that is especially true for Black Americans. A lack of access to healthy food is a problem that disproportionately affects Black and Latino communities — a condition that the U.S. Department of Agriculture formally describes as a “food desert,” though the food justice activist Karen Washington prefers the more apt term “food apartheid” — which are defined in large part by the nearly century-long legacy of redlining.

Decades of U.S. agricultural policies that overwhelmingly favor meat, dairy, and corn have caused many Americans to load up on a diet rich in fatty, processed, and refined foods, but the ill effects of the standard American diet (appropriately also called the SAD diet) are heightened for racial and ethnic minorities. Systemic racism within the dietetics industry has kept Black dietitians out of the field — their number has fallen by nearly 20 percent over the last two decades — while the resulting Eurocentric view of diet and nutrition has severely constrained its approach to non-Western cuisines and cultures. Not only is there a lack of knowledge about the nutritional foundation of many traditional diets, but people from non-Western cultures are pushed toward Westernized views of health and wellness even though, for instance, people of color are generally less able to process dairy products.

What was really interesting for myself, was the division between reclaiming southern soul food as a part of culture to be proud of, versus rejecting it as a recognition that is a large factor in why issues like diabetes (and amputations from it), disproportionately affect black individuals, who have less access to preventative medicine. Obviously as a white person I have no say in this argument but it’s something I wasn’t aware of before reading this.

There’s a passage in Jenné Claiborne’s 2018 cookbook Sweet Potato Soul that beautifully captures the historical thread of plant-based eating in Black culture: When Claiborne was asked by friends if it’s difficult to be a vegan from Atlanta, she reminded them that “my great-grandparents from the South — and my ancestors from West Africa — ate mostly plant-based diets.”

Bryant Terry addresses this — along with the misconception that plant-based eating started with white hipsters, wealthy Goopsters, and animal-rights activists — in Afro-Vegan, where he writes that “for thousands of years, traditional West and Central African diets were predominantly vegetarian — centered around staple foods like millet, rice, field peas, okra, hot peppers, and yams.” Before captivity, as documented in detail in the culinary historian Michael Twitty’s searching volume on African-American foodways, The Cooking Gene, the West African communities of the Igbo and Mande cooked largely with grains, legumes, leafy greens, herbs, and onions. Meat was consumed sparingly, only during harvest time or as a seasoning for vegetables.

New Black Americans saw valuable nutrients stripped from their diet. Many plantation owners fed enslaved people little more than cornmeal and salt pork, the lowliest pieces of the hog, in an effort to save money. “Pigs were so easy to grow, and there were so many other parts that wealthy people discarded; that made it very easy for enslaved people to take those parts and come up with delicacies,” Opie told me over the phone. That paved the way for the dominance of pork — especially chitterlings, hog maws, and pig’s feet — in Southern cooking.

Really recommend anyone agriculturally minded read this, and consider to stop calling veganism a “white person” thing when we speak in western context. Anyone who followed this blog for more than a minute knows I’m not going to say everyone needs to become a vegan to fix the world, but goodness, the western diet is bullshit, people are dying, and black people who are able to empower themselves through veganism to reject another part of the system they’ve been born into is amazing.

Today, there are estimated to be more than a million Black vegetarians and vegans in the United States, with Black people representing the fastest-growing vegan demographic in the country.

711 notes

·

View notes

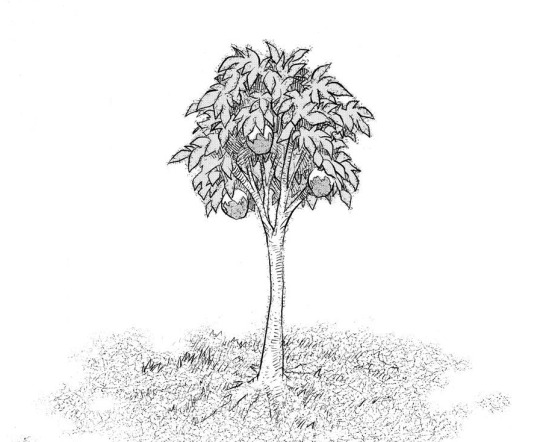

Photo

I’d like to add to the discussion on the origins of nsibidi that I believe nsibidi is part of a tradition of ideographic designs in the general area, for instance ùrì itself contains ideographic elements, there were ideographs used by masking societies and for divination, in Enuani, in the northern part of western Igboland, for instance, there are symbols recorded by colonial government anthropologist Northcote Thomas as ọgbọ obodo [in his orthography ǫbwǫ obodo], this was used for divination as far as I know and was drawn by women in Isele Mkpitime but it’s also possible that they could have been used for other purposes and are related to the yam marks [pictured] that was recorded by Northcote Thomas in 1914 in volume IV of his book on the Igbo people with symbols from Enuani towns which some have named the Aniocha script. I also think these systems of communication, uri, nsibidi, etc, are linked.

“Ǫbwọ obodo” from top-left counterclockwise, “8. Leopard. 7. Cross roads. 6. Mirror. 5. Nkpetime 4. Sun. [from top-right] 3. Ubido (tiger cat). 2. Moon. 1. Seat.”

They aren’t just similar in function, as noted I believe they are linked because they actually share very similar glyphs for similar concepts.

a. “ǫdigu (palm leaf)” Okpanam (Enuani/Aniocha) ‘yam mark’, Thomas (1914).

b. “261. A flower to place in the hair. On left breast of Egom, an Ikom woman.” nsibidi, Dayrell (1911).

c. “93. A tree with a bees' nest containing honey. The bees' nest is represented by the half circle on the right hand side of the tree.“ nsibidi, Dayrell (1911).

d. “122. The 'Nsibidi palm tree [...]” nsibidi, Dayrell (1911).

e. “269. The moon. On right breast of Adda, an Akparabong woman” nsibidi, Dayrell (1911).

f. “2. Moon.” ‘ǫbwǫ obodo’, Thomas (1914).

Nsibidi stands out in particular because it was spread out over a large and ethnolinguistically diverse area and institutionalised through the leopard men’s societies. So nsibidi represents only some of the graphic communication used in the area and presumably beyond which have unfortunately either been mostly forgotten or are near gone because of the colonial quagmire.

201 notes

·

View notes

Note

You’ve probably answered this before but I can’t track it down. But here goes nothing :

What languages can everyone speak/read/understand??? Listed in order of most fluent to least fluent? And what is everyone’s mother tongue/first language??

Thank you💛💛 I love everyone!

I did answer this before but my dumb ass couldn’t find the post so here it is again! First on the list is their mother tongue, followed by fluent to least fluent. Italics are situations where they don’t speak the language but understand to some extent say, the writing system or simple conversation.

AUTOBOTS

Optimus Prime: Kurmanji, English, Arabic, Urdu

Ultra Magnus: Hindi, English, Urdu

Ratchet: English, French, Yoruba

Jazz: English, Spanish, Mandarin, Arabic

Ironhide: English, Spanish

Prowl: Mandarin, Cantonese, English, Hakka, Uyghur, Igbo

Perceptor: Tamil, English

Wheeljack: English, Spanish

Hot Rod: English, Irish Gaeilge

WindBlade: Japanese, English, Korean

Chromia: English, Spanish

Ramhorn: Malay, English

Kup: Nepali, Hindi, English

Drift: Japanese, English

Blaster: Cantonese, English, Mandarin

Hound: Scots (Shetland dialect), English

Bumblebee: English

Mirage: Welsh, English, French

Nautica: Spanish, English

Sunstreaker/Sideswipe: Italian, English

Trailbreaker: Malay-Indonesian, English, Hakka

Nightbeat: English, Swahili, Arabic, Mandarin

Springer: English, Nepali, Mandarin

Swerve: English

Arcee: Hakka, Mandarin, English, Cantonese

Alpha Trion: French, English, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, Mandarin, Arabic, Hindi

Skids: Omniglot due to Outlier ability: Most European, Slavic and Middle-eastern and Chinese languages, Japanese, Malay/Indonesian. Currently learning others.

Roadbuster: Armenian, English

Ironfist: Russian, English

Broadside: Turkish, Arabic, English

Impactor: English, Arabic

Whirl: German, English

Swoop: Polish, English

DECEPTICONS

Megatron: English, Scottish Gaellic, Urdu

Shockwave: Urdu, English, Hindi

Starscream: Italian, English, Japanese

Skywarp: Arabic, English

Thundercracker: Spanish, English

Ravage: Spanish, English, Norwegian

Soundwave: English, Indonesian-Malay, Spanish, Norwegian, German, Mandarin

Laserbeak: Norwegian, English, Spanish

Buzzsaw: French, English

Glit: Korean, English

Barricade: English

Tarn: English, French, Urdu, Uzbek

Kaon: English, Irish Gaeilge

Nickel: Italian, English

Helex: Danish, English

Tesarus: Spanish, English

Vos: French, Arabic

NON-ALIGNED

Senator Proteus: English

Dai Atlas: Igbo, Japanese, English

Rung: Ultimate Omniglot

Terminus: English

Elita One: Russian, English

Trepan: English

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to the "The Lost Testament of the Ancestors of Adam" - Unearthing Heliopolis/Igbo Ukwu - The Celestial City of the Gods of Egypt and India, by Prof Catherine Acholonu, the location of ancient Egypt of mythology and Heliopolis, its capital, was in West Africa.

It demonstrates the West African origin of Egyptian culture and hieroglyphics and of Middle Eastern writing systems, as well as the West African heroes of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey; the West African Post-Atlantis civilization of Igbo Ukwu (a pre-historic, hill-top city in the forest) sponsored by the Egyptian god-men from Atlantis: Thoth, Isis and Osiris, who is also Rama of Dravidian Indians.

The Lost Testament provides undeniable evidence that the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata were records of wars between West African Nagas from Punt/Tilmun/Panchea/ Meluhha and Atlanteans before and after the Deluge (11,000 B.C.).

..............

Going by Biblical and historic calculations, the Creation of Adam and Eve happened around 6,000 years ago. While the oldest record of humans in the world has been traced to Africa and is recorded to be over 3.2 million years (Lucy, a 3.2 million-year old fossil skeleton of a human ancestor, was discovered in 1974 in Hadar, Ethiopia).

So it simply means that Africans are older than Adam and Eve (supposed Caucasians), and that the Igbo among many other African peoples are the ancestors of Adam and Eve.

~ Chuka Nduneseokwu, Editor-in-chief, Liberty Writers

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

An interview with Nigerian anarchist Sam Mbah

Interviewer: It’s my pleasure to introduce Sam Mbah, author of the groundbreaking book ‘African Anarchism’, a lawyer, a journalist, an activist. This interview is being recorded in Enugu, Nigeria, in March 2012. Sam, thank you very much for taking the time to do this interview. ---- Sam: It’s my pleasure Jeremy. ---- Interviewer: It’s been about 15 years since the publication of your book on the prospects of anarchism in Africa. What is there, if anything, that comes to mind that you would add to or change about the book, and the ideas that you presented in it? ---- Sam: Yeah, I want to look at the ideas that I would add, not really change. Ever since the publication of the book I have been collecting additional materials that I stumble upon in the course of my writings and research.

I think there is room for additions to the book, not really much to change, or subtract from the work. I think there is room for additions to the book, and this is something I have already started in the sense that in the Spanish edition that came out in 2000, I wrote an extensive foreword, wherein I tried to articulate some of the points we missed in the original book. I tried to look at more African societies that shared the same characteristics and features as the Igbo, the Tiv, the Efik, the Tallensi and the multiplicity of tribes and social groups that we have in Nigeria that I have already mentioned in the book. I also tried to explore other groups in other parts of the world especially Latin America, and I was able to draw some parallels between their social existence and systems of social organization, and the characteristics and features of anarchism, as I understand it.

Interviewer: For those of us who haven’t read the book recently, can you just recap a couple of things about what anarchism means to you and how is it connected to some of the intrinsic aspects of African culture?

Sam: OK, I pointed out in the book right away that anarchism as an ideology, as a corpus of ideology, and as a social movement, is removed to Africa. That was a point I made very explicitly at the outset of the book. But anarchism as a form of social organization, as a basis of organizing societies – that is not remote to us. It is an integral part of our existence as a people. I referred to the communal system of social organization that existed and still exists in different parts of Africa, where people live their lives within communities and saw themselves as integral parts of communities, and which contributed immensely to the survival of their communities as a unit. I pointed to aspects of solidarity, aspects of social cohesion and harmony that existed in so many communal societies in Africa and tried to draw linkages with the precepts of anarchism, including mutual aid, including autonomous development of small units, and a system that is not based on a monetization of the means and forces of production in society. So, I look back and I feel, like I pointed out earlier, these are things that if we carry on additional research it would throw more light on how these societies were able to survive. But again, with the advent of colonialism and the incorporation African economies and societies into the global capitalist orbit, some of these things of changed. We’ve started having a rich class, we’ve started having a class of political rulers who lord it over and above every other person. We’ve started having a society that is highly militarized where the the State and those who control the State share the monopoly of instruments of violence and are keen to deploy it against the ordinary people. That’s their business.

Interviewer: In the last few years we’ve definitely seen an increase in authoritarian rule in many parts of the world, and austerity measures, in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks in the States and the global financial crisis, more recently. How do you see those issues, and how have they affected Africa, and the struggle here?

Sam: When I wrote African Anarchism with my friend, we wrote against the backdrop of three decades of military rule, nearly four decades of military rule, in Nigeria. Military rule was a form of government that believed in over-centralization of powers, and dictatorship, as it were, and it was a strand that evolved from capitalism. So while the Nigerian society and much of Africa was under the grip of military rule and military authoritarianism, today we have a nominal civilian administration, a nominal civilian democracy. Some people have called it rule democracy, some people have called it dysfunctional democracy, all kinds of names, seeking to capture the fact that this is far from democracy. And for me it is an extension of military rule. This is actually a phase of military rule. Because if you look at democracy in Nigeria, and the rest of Africa, those who are shaping the course and future of these democracies are predominantly ex-military rulers, and their apologists and collaborators within the civilian class.

So, looking at the global stage, capitalism is in crisis. At any rate, capitalism cannot exist really without crisis. Crisis is the health of capitalism. This crisis is what many philosophers, from Marx to Hegel to Lenin to Kropotkin to Emma Goldman, and more currently Noam Chomsky have spoken extensively about: the tendency for crisis on the part of capitalism. So, between the coming of ‘African Anarchism’ and today, we have seen 911, the so-called ‘war on terror’, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, today we’re faced with a major global economic crisis that is reminiscent of the great depression of the 1930s. And there is no absolute guarantee that, even if the global economy emerges from this crisis, it will not relapse into another, because the tendency towards crisis is an integral part of capitalism. For us, here, these historical developments have had a serious impact on our society, our economy, our government.

If we begin from the 911 incident, today the world is under the grip of terror and counter-terrorism as well. Here in Nigeria in the past one year, the country has commonly experienced bombings, explosives, we are seeing everyday increasingly everyday there is a bomb set off in one place. And how does the Nigerian State react? It reacts with more force, and in the process of using more force it creates collateral damages and casualties all over the place. So we are not immune from the ravages of terrorism and the ‘war on terrorism’ which the West embarked upon, after 911. Our country is well under the grip of terror. And it is ironical that any moment there is a bomb that explodes somewhere, the government shouts, ‘this is terrorism! this is terrorism!’ But the hard line tendencies of government and the agencies of the State which use undue force and undue violence in resolving issues that would otherwise have been resolved without any loss of life – these are glossed over and seen as being normal. But any moment a bomb is set off anywhere, the government counters that this is terrorism. I would say that government, the State, in Africa, is the greatest source of terror. The State in Africa is the greatest source of terrorism. I think that the society would be a lot better, the day the State ceases from acting and deploying its agencies as instruments of terror against the ordinary population, and the common people.

So, the global economic crisis, the global capitalist crisis, has impacted negatively on African economies, including Nigeria – because we are part and parcel of the global capitalist system, albeit we are unequal partners in the global capitalist exchange. Our economy is dependent on commodities. Our economy is a mono-crop one. Anything that happens to oil is bound to have a crisis effect on us. And that is one of the reasons why you saw Nigerians and the Nigerian State in a stand-off at the beginning of this year [2012], over phantom subsidies which the government said it wanted to remove, and which people protested.

Interviewer: Could you explain a bit more about the fuel-tax subsidy for those who aren’t familiar with how it works in Nigeria?

Sam: OK. The fuel tax, or what the Nigerian government calls the ‘fuel subsidy’, assumes that the government is subsidizing the cost of fuel for the citizenry. That the Nigerian people are not paying a realistic value for fuel in the country. But the counter-argument is that we are an oil-producing country, and there is no reason why the cost of fuel should be based on the global or international market. We have refineries, we have about four refineries that collectively have a refining capacity of about 500,000 barrels per day. But you find that in the past twenty years these refineries have not functioned. They have not functioned because of corruption. They have not functioned because the powers that be in the country are not interested in these refineries functioning. The only reason why these refineries are not functioning is because there is corruption and a lot of people in government, in the military and in the bureaucracy, are benefitting from the wholesale importation of refined petroleum product. Nigeria is about the only OPEC country that imports 100% of its refined petroleum needs.

Interviewer: So at the beginning of this year [2012]…

Sam: So the ordinary people in Nigeria are saying, if our refineries were working, and they refined our crude, the government should be able to say at what cost this crude, these products are refined. And based on the cost of refining you can now set a price. That insofar as you have not been able to make the refineries functional, and you are fixing the cost of petroleum products on the basis of what it is in the international markets, you are making a grave mistake. Because the cost of living in Nigeria is different from the cost of living in United States. So the government says, ‘We pay so much to the importers of petroleum products as subsidy’ – that means the difference between the cost of importation and the selling price of the refined product. But you find out that even those who have been in government, even ministers of petroleum products, came out to say that much of what you pay as subsidy is based on corrupt documentation, which the government does not investigate, which the government does not in any way try to clarify, which involves senior officials of the organs and agencies that are supposed to regulate the petroleum industry. They are the ones who are paying these huge sums to themselves and to their companies. Let me illustrate the concept of the oil subsidy by one reference. The Nigerian government allows a multiplicity of traders to bring in petroleum products. They buy refined petroleum products from a multiplicity of international traders, when in fact the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation – the NPC – which is our national oil company, can enter into purchase agreements with refineries that exist abroad, and get these refined products directly from refineries. Instead, they prefer to go through middle men, who get the refined products from refineries, and sell them to NPC at exorbitant rates.

Interviewer: So what happened at the beginning of the year [2012]?

Sam: At the beginning of the year the government wanted to supposedly deregulate the downstream sector of the oil industry. And labour and civil society groups protested, and resisted such a move. In the event, a two week strike was called. During those two weeks, the people stayed away from work, the people protested in the streets of Lagos, Kaduna, Port Harcourt, Kano, Ibadan, in different parts of the country. And because the government sensed the resolve of ordinary Nigerians to resist these arbitrary increases, the government backed down somewhat, by bringing down the over 100% increase in prices of petroleum products to about 30%. And of course the labor movement practically sold out, because the civil society and the mass of the population were prepared to go on with the protest and refuse the pay the 30% increase, but labor sold out, and that is where we are today.

I would say, it is an unfinished struggle. My sense is that the government still intends to achieve its objective which is 100% increase in the price of petroleum products. But if there is anybody in government who is still thinking, who is still moved by any sense of objectivity, they would have seen that the resolve of Nigerians to resist these arbitrary increases based on false analysis of what subsidy constitutes, is something they cannot wish away. The people are also mobilizing. Just as the government is devising other strategies through which it will increase the price of petroleum through the back door, the people are reviewing the last encounter and trying to find out what other ways they can employ that advance their cause.

Interviewer: In that massive and very inspiring mobilization, there were elements of reflection of some of the global movements we’ve seen recently, some part of the protest was called ‘Occupy Nigeria’. We’ve seen the explosion of the Occupy movement and the Arab Spring, what do you think of those?

Sam: Yeah, yeah, the Occupy movement in parts of America and Europe has really inspired a lot of people in Nigeria. The resolve and the courage that has been demonstrated by the Occupy movement in different parts of America and European capitals, is a pointer to the endless possibilities that abound if people decide to struggle. The Arab Spring on its part, has been a most refreshing experience for those of us in Africa. Actually, I’ve had conversations with my friends and I try to point out the fact that the Arab Spring should have been happening in sub-Saharan Africa, rather than in the Arab world, in North Africa, because the abject conditions of living in Africa [are much worse than] the relatively advanced standards of living in most of the Arab countries and even our neighbors in North Africa. So the Arab spring should have been happening in sub-Saharan Africa. That is my sense. But why is it not happening? It is because we have not been able to turn our anger into resolve, we have not been able to build the requisite social consciousness, to be able to instigate and sustain such a struggle.

But based on what happened in Nigeria recently, I have no doubt that people are beginning to draw lessons from what is happening in the Arab world. And asking themselves some searching questions – if it can happen in the Arab world, why not us? If people who are living in better social conditions can elect to fight, to struggle, to protest in the streets, for days and months on end, how about us who cannot even find light. Light in Nigeria is a luxury. Our economy is a generator-set economy. [The State electricity grid functions very poorly; the rich use private electricity generators.] You virtually provide your own water, you provide your own security. Nothing works here. Unlike if you were to go to Libya. I’ve not been, but I’ve read stories about Libya, Egypt, Tunisia. These are better organised societies, where social amenities and public utilities function. But here we are in sub-Saharan Africa where nothing works. So, I can say without any fear of contradiction that the protests in Nigeria in January, were an offshoot of the Occupy movement in America and Europe, as well as an offshoot of the Arab Spring. So, I don’t know whether our protests have gotten to the point where we can call it a ‘Nigerian Spring’, but I guess that the Nigerian Spring will still come.

…

Interviewer: Sam, climate change is a major threat to Nigerians, as it is to everyone else on the planet. What are some of the specific environmental issues here, and what sort of consciousness is there of climate justice, and sustainable development?

Sam: I’ll answer your question from two perspectives. Let me answer it with the general perspective and then I’ll come to the more personal perspective. The threat of climate change is real. We, in this part of the world, are not immune from the threats of climate change. If we take a look around us, the humidity levels are rising. In recent times, where I live (I live in a small bungalow of three rooms), if there is no light [no electricity, no fan], I can hardly sleep. My children can hardly sleep, except during the rainy season, it becomes a lot more manageable during the rainy season. Because what makes it even worse is that our light, our electricity situation, is in fits and pieces. I’ve found that in the past three or four years, between the months of March and April, before the rains start all over again, I am sweating like I have never sweated in all my life. I am seeing increasing levels of temperature that I did not see while I was growing up, and even in the 80s and 90s. Over the past five years, one has had to live with very sweltering temperatures. And the sources of this are not far-fetched.

If you look around, the forests that used to exist… If I go to my village, there used to be very deep forests, where little children would even find it very difficult to enter. Today most of these forests are no more. The little trees and mini forests that exist are being logged on a daily basis, and there is no form of check on logging. If you go to the villages, logging is taking place at very ridiculous levels. There is no agency of government in this part of the country that is doing anything to regulate it, to curtail it, to minimize it. So trees are being cut as never before and nobody is doing anything to replace these trees. The forest cover is increasingly going down and in our own part of the country where the population density is probably the highest in Africa outside the Niger Delta, we find that human activity is impacting seriously and negatively on the environment. People are building uncontrollably, roads are being built, bushes are being burnt. There is deforestation on a massive scale. And one of the consequences of deforestation in our part of the country is erosion, of soil, gullies, even roads in some places have been cut in two. Then of course the streams and rivers and rivulets that used to contain a lot of aquatic life are today drying up. There’s a stream that lies about 200 metres from my country home in the village. When I was growing up I never saw it dry up. But in the past ten years, if the rains fail to fall between February, March, and April, times when the stream dries up.

Interviewer: And how are people thinking about that, because people want to see development, but how can that be justified with sustainability?

Sam: The ordinary people do not have an accurate consciousness of what is happening. They are blaming evil forces, unseen hands and all kinds of metaphysical objects for these happenings and these developments. And it is actually up to the government to educate the people about the negative consequences of deforestation, of unbalanced utilization of resources, about the benefits of a planned, sustainable development – both for the individual and for the society at large. But the government is not doing much in this area. There is actually a dearth of public enlightenment and conscientization on the principle issues.

And you find also that in our villages, the lands that used to be fertile are not producing as much food, as much crops, as they used to. These are the consequences of climate change.

Yes, at the level of the elite, of the enlightened few, there is a realization that yes, something is wrong. But at the level of ordinary people, there is no conscientization, no effort to enable them to understand that it is in their interests to ensure that they protect their environment.

Interviewer: You mentioned the Niger Delta. That is one area in Nigeria where the struggle over environment and oil has been particularly acute, with massive oil spills but also militant activity which has had a real impact on oil production and trying to reclaim some of the wealth from oil for people. What are your views on the activities of militants in the Niger Delta?

Sam: The activities of militants should not be viewed in isolation. The activities of militants is consequent upon the exploitative tendencies of oil companies operating in the Niger Delta, who are not adhering to international best practices that they continue to observe elsewhere around the world. In Nigeria, because they are complicit with the Nigerian state and the government, they carry on as they wish. They carry on as if tomorrow does not exist. They carry on because there is nobody to call them to order, to hold them to account. So the emergence of the militant groups in the Niger Delta is consequent upon the exploitative practices and tendencies, and the absolute lack of care for the environment in the exploration, drilling and production of most of the oil companies operating in the Niger Delta.

So, if viewed against this background, the militant groups are responding to a clear and present threat to the existence of communities in the Niger Delta. When we were growing up, we grew up to learn that most of the villages, tribes and social groups in the Niger Delta were essentially fishermen. But with the constant oil spills, despoliation of the environment, the denudation of the fauna and the aquatic life of the Niger Delta, much of the fishing industry has disappeared. Much of the farming and agricultural activities taking place there have also disappeared.

So, when you have robbed a people of their environment, how, in good conscience, do you expect them to survive? To continue to exist as a people. You see, our people have a saying that nature has placed at the disposal of every group a means of survival. I’ll give you an example. In the south-east, in Igboland for instance, our people survive mostly on our land. We survive on our palm trees, our people make palm oil, our people farm, this is the basic means of subsistence. If you go to the North, they do not have palm trees. They survive on other firms of agriculture, like planting onions, planting yams, and also pastoral existence. If you go to Niger Delta, the basic means of subsistence is fishing, and some forms of agriculture and farming too. So if we agree that nature has placed at the disposal of every group some forms of sustenance, we are witnessing a situation where the means of sustenance of much of the Niger Delta has been taken away. Through the activities of oil companies who are not minded on any form of corporate social responsibility.

So, that is the context in which I view the militancy that sprung up in the Niger Delta from the late 1990s till today. Yes, most of the militant groups engage in all forms of criminality and banditry as well, which do not in any way serve the interests of ordinary Niger Deltans. And that is condemnable, but it does not in any way vitiate the original sin that pushed them into further sin.

Interviewer: Yes. Speaking of sin, Nigeria is quite a religious society. Religion is very deeply ingrained here. And often it takes quite conservative, sometimes violent forms. What are your thoughts on religion in Nigeria and what it means for anarchism and organising more broadly?

Sam: I’ll say that religion and religious practices have entered a new phase in Nigeria. Before the advent of colonialism, our people were mostly African religionists, who worship our small gods – gods of thunder, gods of river, and such other gods. With the coming of colonialism, the two main global religions – Islam and Christianity – became a predominant force in the lives of Nigerians.

The rivalry and competition between the two religions has tended to play down the fact that not all Nigerians are Christians or Muslims. Even in the North-central, you are talking about pagan tribes and different forms of African religion that take place in those places. But today Nigeria is profiled and stereotyped as a Christian South and a Muslim North. Yet if you go to the North you find a lot of non-adherents to Islam, you come to the South as well you find a lot of non-adherents to Christianity.

But I would say that in the past 20-30 years the singular influence of Christianity and Islam has been considerably negative on the society in the sense that both religions have become sources of manipulation, political manipulation of ordinary people. When you hear that there is a religious riot in the North, a religious riot in the East, when you go down and examine the issues, they are not basically religious. Politicians are using religion to manipulate the ordinary people into fighting for the political positions and beliefs of the elite.

Religion has become an instrument of manipulation, exploitation, deceit, and large-scale blindfolding of ordinary people in Nigeria. It is one of the elements militating against social consciousness and the development of the working class, as a class, in Nigeria. The development of a class of the dispossessed, the oppressed, the marginalized, who feel and share common interests and are keen to fight for those common interests. Religion is thrown in as a wedge, as a source of conflict among ordinary people. Like Karl Marx said, religion becomes the opium of society. Every little thing is covered, is given a religious coloration, when it is actually not. It is a tremendous setback to the development of social consciousness in Nigeria and the rest of Africa as a whole.

Interviewer: Yes. You’ve already touched on it, but those religious divisions are often related to (but not solely related to) ethnic divisions, and race, and gender as dividing people from each other. What are your thoughts about that?

Sam: Well the problem we have is not really race as such, it is about religion, it is about ethnicity. Much of religion in Nigeria and Africa is geographical. You find that religion tends to conform to certain ethnic boundaries. When you hear about a Fulani, you imagine a Muslim. When you hear about an Igboman, you imagine a Catholic Christian. When you talk about the man from the middle belt of Nigeria, you’re talking about an evangelical Christian. So, much of our religious differences have become geographical in nature, in the sense that certain ethnic boundaries are coherent also with certain religions. The people have been made to see these differences as permanent features of life, not things you can overcome. The truth is that before the commodification of exchange and the means of sustenance in our society, before the monetization of the economy, people related with one another, and did not mind about religious differences. Everybody believed your religion ought to be a personal issue to you. But with the politicization of religion, the way we are seeing it today, social differences have been magnified by politicians, who use it to manipulate and control the mass of the population.

Interviewer: And what about gender? Is there a change in the struggle for women’s liberation?

Sam: The struggle for women’s liberation in Nigeria and the rest of Africa has come a long way. In the sense that, our society, which is patriarchal in nature, emphasises the role of the man. In many African societies, as I tried to point out in my book, the role of women is diminished, reduced to almost to footnotes. But the truth is that even in traditional African societies, if I use the tradtional Igbo society as an example, the role of the women is critical, is central to the creation of balance and social harmony. But most of the time it is underplayed.

Interviewer: You’re talking about the role women play as leaders?

Sam: Yes. You might not believe it, but let me tell you something – one of the less obvious manifestations of African society. In traditional African societies, in traditional Igbo society, for example, a woman who is unable to give birth for the husband, assuming the husband dies, and the woman is faced with the reality of not continuing the lineage at her own death, it was common for women who find themselves in this situation, to marry another woman. So when Africans say lesbianism, or women marrying women, or men marrying men, is not traditional to us, any clear-headed political analyst, anthropologist or sociologist in this part of the world, would know in Igbo society it was common for women to marry women, when faced with that situation in the absence of their husband, and be seen as the wife of the older woman. Maybe the older woman might also bring a man who sleeps with the younger woman and begins to raise offspring for the memory of the late husband.

The traditional African society would not achieve balance and harmony without the role of the women. Their role was critical to the resolution of disputes. In Igbo resolution of land disputes, family disputes, and intractable social issues, the views of women, especially those who were seen as women who have made some achievement materially was continually sought by the men folk in traditional African societies.

Moving away from traditional African society to the present day, education has been the critical force in the liberation of women. Women go to school, in Igboland today there are more women in school than men. Because the men go off to do business, trading activities. Increasingly, in many primary and secondary schools the number of female pupils outnumbers the males. Many families have realized that if you train women, you train a nation, if you train a man, in some cases, you are just training an individual.

The importance of women in our society is continually being reasserted. The courts of law have played some role in trying to liberate women from being the underlings of society. In Igboland in the past, women could not inherit the estate of their fathers, even if they were the only children of their parents. There is now a court document that says a man can make a will and devolve his estate among his male and female children equally. In cases where the man did not have male issues, he can devolve his estate among his female children.

So we’ve recognized some advance. There is virtually no course in university where you do not find some women folk – medicine, engineering, geology, computer science, not just the humanities and arts. Women are everywhere, even in the military. But I would say still, given the fact that our society is 50% male, 50% female, there is still a lot room for improvement for women. It is an ongoing struggle. It is not something that is likely going to end. The momentum we have have achieved is such that the future looks very very bright indeed for women’s liberation and gender equality in our society.

…

Interviewer: Sam, you played a very important role in the ‘Awareness League’, which was a Nigerian anarchist organization that flourished in the 1990s. Can you tell us a bit about how it grew and how it declined?

Sam: It’s a little nostalgic for me these days, talking about the Awareness League, because the Awareness League was a romantic idea. When we entered the universities in the early 80s, what we encountered was socialist groups, socialist teaching, Marxist teaching especially. And we became attracted to Marxism, in the sense that it preached the coming of a new dawn in society, and by extension, the African continent. We were really enthralled by the perspectives of Marxism, and the abiding, thorough critique of capitalism that Marx and Marxist literature embodied. It did not take much time before we defined ourselves as Marxists on campus, and this continued until we left the universities. When I was leaving university I wrote a thesis in my final year on the political economy of Nigeria’s external debt crisis then, and in the thesis, it might interest you to know, I employed the Marxist framework, as my tool of analysis. Where Marx was talking about the economy as providing the axis around which the further movement in society revolved, whether it was politics, or culture. I also talked about the tendency of capitalism towards crisis. These were ideas that enthralled us. Also the ideas of revolution. Marx said that the history of all hitherto existing societies has been the history of class struggle, and talked about the revolution being the midwife of a new society, giving birth to a new one.

Usually in Nigeria, after your graduation from university, you are obliged to take part in a mandatory one year service. So I was posted to the old Oyo state with its capital at Ibadan, for the mandatory one year national service. It was there that I met a couple of socialist-minded young men like myself, and we started organising and talking about Marxism, socialism, leftist resistance. We identified ourselves essentially as a leftist organization. In the course of that, some of us started subscribing to ‘The Torch’ newspaper, published in New York. It was there we started gleaning for the first time, the initial ideas of anarchism. That was how, gradually, when we finished our national service, some of us who were living in the south-east, started thinking about an enduring platform. Because socialism even then was entering a serious crisis. The crisis of the Soviet empire was brewing. It was not long thereafter that communism collapsed in Europe. And it was in the midst of this crisis that we started increasingly vacilating towards anarchism. Subsequently, Awareness League was born, and the rest is history.

The Awareness League first of all, derived its lifeblood from the resistance against military rule in Nigeria. The continuation of military rule acted as a spore. It was one of the inclusions that continued to give oxygen to our existence then as Awareness League. It is on record that between the late 1980s and the late 1990s, Nigeria witnessed the toughest anti-military struggle. Awareness League joined forces with other anti-military groups in resisting military rule in Nigeria. It was in the process of coming into touch with a lot of anarcho-syndicalist groups around the world, in Europe and America , that I and my friend decided to intellectualise the the subject of anarchism by producing a book, which you very well know.

The struggle against military rule ended with the coming of civilian rule in 1999. I would say that the antagonism of not only the Awareness League but all the civil society, community-based groups, and leftist organizations in the country, virtually evaporated. Because the military was a uniting factor, I would say, in the sense that every person – whether you were anarchist, Marxist, leftist, socialist – saw in the military a common enemy to be resisted, to be opposed, to be overthrown if possible. With the coming of civilian government, we did not have that kind of common enemy any longer. Because some of the groups, some individuals from these groups, now started gravitating towards bourgeois politics. But let me say that for the most part, the problem was not individuals gravitating towards bourgeois politics, it was really that the civil society groups, the leftist groups and organizations, were not prepared for the consequences of [civilian] rule. We did not analyze in a serious sense what would be the consequences of the end of military rule and the coming of civilian rule, in the place of the military. We took it for granted that it would be business as usual. But as it happened, the end of military rule singularly signaled the end of most of these community-based, civil-society-based groups. Most of these groups, including the Awareness League, fragmented.