#Inca ritual

Text

By Erin Blakemore

October 25, 2023

More than 500 years ago, a 14-year-old girl was escorted up an Andean peak and sacrificed to Inca gods.

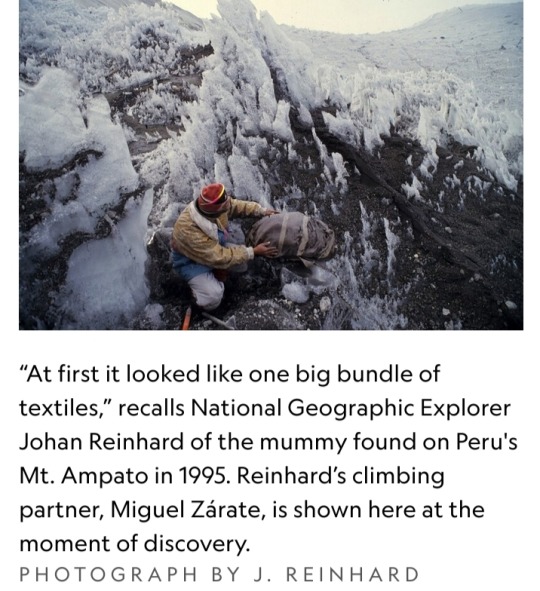

Buried on the mountain with a variety of offerings, the young woman’s body naturally mummified over time, preserving her hair, her fingernails, the colorful robes she wore on her last day.

But at some point across the centuries, her face became exposed to the elements, her features slowly vanishing over seasons of sunlight and snowfall.

Now, that long-lost face has been recovered thanks to painstaking archaeological analysis and forensic reconstruction.

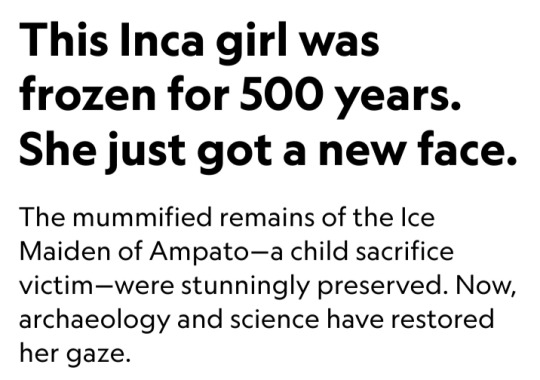

A striking 3-D bust of the young woman, known today as the Ice Maiden of Ampato, is the centerpiece of a new exhibit in Peru and part of an ongoing effort to understand the drama of human sacrifice practiced in the Andes half a millennium ago.

A sacrificial offering

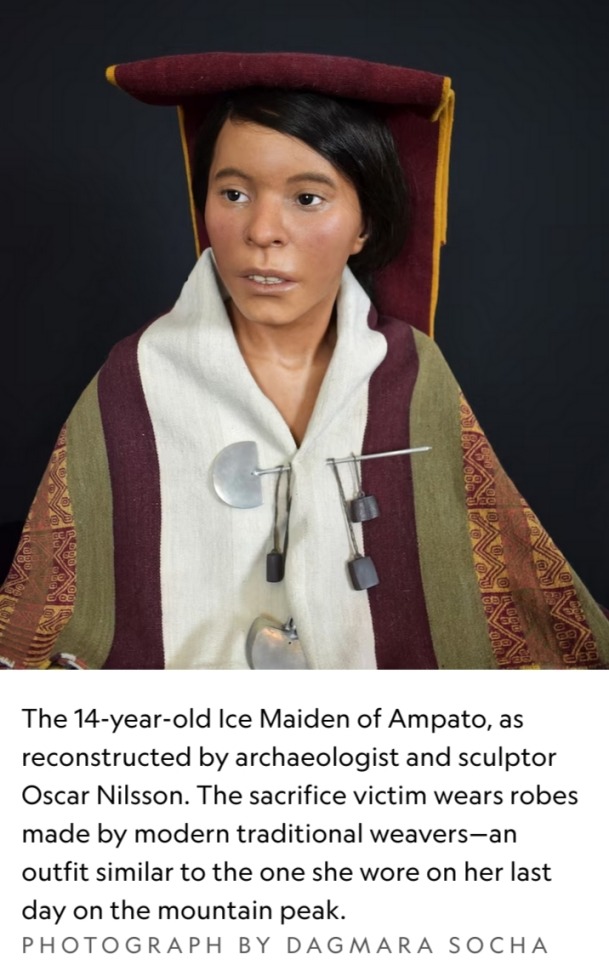

When National Geographic Explorer Johan Reinhard encountered the mummy, also known as Juanita, atop 21,000-foot Mount Ampato during a 1995 expedition, he knew he had discovered something spectacular.

“At first it looked like one big bundle of textiles,” Reinhard recalls. Then he saw the wizened face amid the folds of fabric.

Here was a young victim of the elusive Inca ritual known as capacocha.

Capacocha mostly involved the sacrifice of children and animals who were offered to the gods in response to natural disasters — to consolidate state power in far-flung provinces of the Inca Empire, or simply to please the deities.

The ritual played an important part in sustaining the Inca Empire. It would involve feasts and grand processions to accompany the children, who appear to have been chosen for their beauty and physical perfection.

Being selected for sacrifice, researchers believe, would have considered a deep honor by the child’s family and community.

Most of the information we have on capacocha, however, is second hand, notes Dagmara Socha, an archaeologist with the Center for Andean Studies at the University of Warsaw who studies the ritual and commissioned the facial reconstruction of the Ice Maiden of Ampato.

“No European colonist ever saw the ceremony,” she explains.

Despite gaps in the historical record, the high-altitude archaeological finds of more than a dozen Inca children on Ampato and other mountains point provide critical evidence for what happened during these rituals.

The means of sacrifice varied, perhaps due to customs related to specific gods. Some children were buried alive or strangled; others had their hearts removed.

The Ice Maiden’s life ended with a single blunt-force blow to the back of the skull.

In search of the Ice Maiden

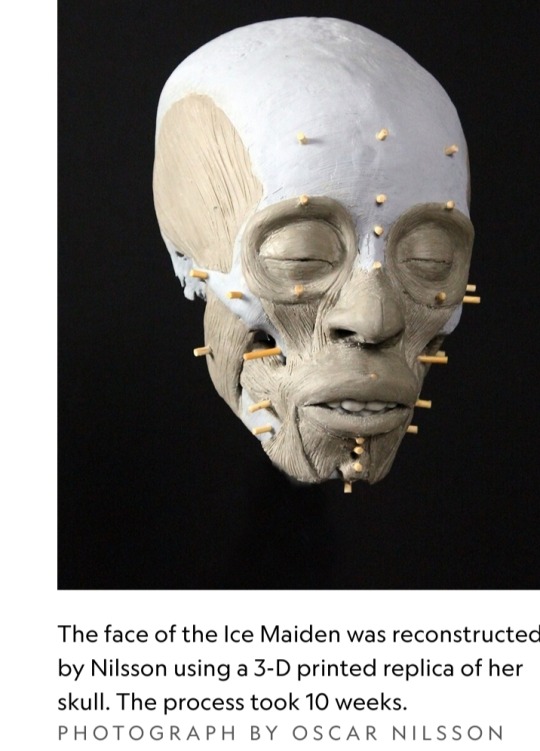

Oscar Nilsson knows that skull intimately: He spent months with a replica of it in his Stockholm studio, eventually fashioning a sculpture of the 14-old-girl that, glimpsed from afar, almost seems alive.

It’s a two-step process, says the Swedish archaeologist and sculptor.

First, Nilsson immerses himself in the world of his subject with an archaeologist’s eye for detail, digesting as much data as possible to understand what she might have looked like.

Even without a mummified face, he can extrapolate the likely depth of the facial tissue that once draped over those bones, using everything from CT scans to DNA analyses to information about diet and disease to make educated guesses about the individual’s face.

Then came the handiwork. Nilsson printed a 3-D replica of the Ice Maiden’s skull, plugging wooden pegs into its surface to guide the depth and placement of each hand-crafted, plasticine clay muscle.

Eerie eyes, masseter muscles, a nose, the delicate rope-like tissues that constitute a human face: each was added in turn.

After making a silicone mold of the bust, he added hundreds of individual hairs and pores in shades of brown and pink.

It took ten weeks.

Following the Inca Gods

The result, wrapped in robes woven by local women from Peru's Centro de Textiles Tradicionales, is the main attraction at “Capacocha: Following the Inca Gods” at the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa, Peru through November 18.

The reconstruction will be displayed alongside the Ice Maiden’s mummy, accompanied by the stories of 15 other children selected for capacocha atop Ampato and other Andean peaks.

Their ages range from 3 to about 13. The mummies and skeletal remains of several are featured as 3-D models at the exhibition, which also showcases holographs of some of the sacred items buried alongside them.

These natural mummies offer scientists tantalizing clues about their last days.

When Socha and colleagues conducted toxicological and forensic analyses of the remains of a toddler and four six-to-seven-year-old victims featured in the exhibition, they found they were well cared for in the months before their sacrifice.

They were fed a steady diet of coca leaves, ayahuasca vine, and alcohol in the weeks before their deaths — not as much to intoxicate them as to keep them sedated and anxiety-free as the timeline hurtled toward their sacrifice.

“We were really surprised by the toxicology results,” says Socha.

“It wasn’t only a brutal sacrifice. The Inca also wanted the children to be in a good mood. It was important to them that they go happily to the gods.”

High altitude, psychogenic substances, the spectacular view, the knowledge the afterlife was near — all must have made for an astonishing ceremony, says Reinhard.

“The whole phenomenon must have been overpowering.”

During the last phase of his reconstruction, Nilsson spent hours contemplating and attempting to capture the young girl’s presence 500 years after her death.

The result is both unsettlingly realistic and jarringly personal.

“She was an individual,” the forensic reconstructionist says.

“She must have understood her life would end on the mountaintop in a couple of weeks. We can only hope that she believed in the afterworld herself.”

For Reinhard, finally seeing the face of the girl he carried down the mountain on his back decades ago brought the Ice Maiden’s story full circle.

“It brings her back to life,” he says. The reconstruction brings the focus as much to her culture and daily life as to her spectacular death.

But Nilsson never forgot the way the Ice Maiden died, even as he brought her to life through his reconstruction.

More than anything, he says, he wanted to capture a sense of being frozen — a nod not just to her icy, mummified future but to a girl teetering on the edge of eternity, though still very much alive.

“She knew she was supposed to smile, to express pride,” he says. “Proud to be chosen. But still very, very afraid.”

#Ice Maiden of Ampato#Inca Girl#archaeological analysis#forensic reconstruction#human sacrifice#Peru#3-D bust#Juanita#Johan Reinhard#Mount Ampato#National Geographic#National Geographic Explorer#expedition#1990s#20th century#capacocha#Inca ritual#Inca Empire#Dagmara Socha#facial reconstruction#archaeology#archaeologists#Oscar Nilsson#sculptor#Centro de Textiles Tradicionales#Capacocha: Following the Inca Gods#Museo Santuarios Andinos#natural mummies#culture#forensic reconstructionist

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los arqueólogos han encontrado 135 sitios antiguos en la cima de una colina, incluida una estructura circular que alguna vez se usó como un sitio sagrado para los antiguos cultos andinos para adorar al sol.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The power of the Ancients. #riseup #rise #inca #yerbamate #southamerica #ervamate #gaucho #sacred #blessings #tea #teatime #rituals #oldcountry https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn0Y0nAN5vB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#riseup#rise#inca#yerbamate#southamerica#ervamate#gaucho#sacred#blessings#tea#teatime#rituals#oldcountry

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Found thiz 💎 Gem &&& otherz awaiting the arrival of my other bookz 📚 from Amazon... #CantStopLearning✌🏾👋🏽🇲🇦 #donkilamamazon #CantTouchThisDonKilam #Million$$$WorthOfGame "Mythology of the American Nations"... #Godz #Heroes #Spirits #SacredPlaces #Rituals #AncientBeliefs #NorthAmericanIndian #Inuit #Aztec #Inca #Mayan #Nations #knowthyself #KnowMOORBeMOOR👣🇲🇦👑🏹🪶⚔🗡🛡👳🏾♀️⛰🕌🕍⛺⌛⏳🌠🌌🪐✨🗿⚱✌🏾🖐🏾 ... #Muurs #muchMoor2Life #muchmoorthanblack🇲🇦🇲🇦🇲🇦👈 (at Casablanca, Morocco) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm-EdNVOOGQkIQASzoyU4OFxPWvQHnNIr7S1BU0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#cantstoplearning✌🏾👋🏽🇲🇦#donkilamamazon#canttouchthisdonkilam#million#godz#heroes#spirits#sacredplaces#rituals#ancientbeliefs#northamericanindian#inuit#aztec#inca#mayan#nations#knowthyself#knowmoorbemoor👣🇲🇦👑🏹🪶⚔🗡🛡👳🏾♀️⛰🕌🕍⛺⌛⏳🌠🌌🪐✨🗿⚱✌🏾🖐🏾#muurs#muchmoor2life#muchmoorthanblack🇲🇦🇲🇦🇲🇦👈

1 note

·

View note

Text

500-year-old Snake Figure from Peru (Incan Empire), c. 1450-1532 CE: this fiber craft snake was made from cotton and camelid hair, and it has a total length of 86.4cm (about 34in)

This piece was crafted by shaping a cotton core into the basic form of a snake and then wrapping it in structural cords. Colorful threads were then used to create the surface pattern, producing a zig-zag design that covers most of the snake's body. Some of its facial features were also decorated with embroidery.

A double-braided rope is attached to the distal end of the snake's body, near the tip of its tail, and another rope is attached along the ventral side, where it forms a small loop just behind the snake's lower jaw. Similar features have been found in other serpentine figures from the same region/time period, suggesting that these objects may have been designed for a common purpose.

Very little is known about the original function and significance of these artifacts; they may have been created as decorative elements, costume elements, ceremonial props, toys, gifts, grave goods, or simply as pieces of artwork.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art argues that this figure might have been used as a prop during a particular Andean tradition:

In a ritual combat known as ayllar, snakes made of wool were used as projectiles. This effigy snake may have been worn around the neck—a powerful personal adornment of the paramount Inca and his allies—until it was needed as a weapon. The wearer would then grab the cord, swing the snake, and hurl it in the direction of the opponent. The heavy head would propel the figure forward. The simultaneous release of many would produce a scenario of “flying snakes” thrown at enemies.

The same custom is described in an account from a Spanish chronicler named Cristóbal de Albornoz, who referred to the tradition as "the game of the ayllus and the Amaru" ("El juego de los ayllus y el Amaru").

The image below depicts a very similar artifact from the same region/time period.

Why Indigenous Artifacts Should be Returned to Indigenous Communities.

Sources & More Info:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Snake Ornament

Serpent Symbology: Representations of Snakes in Art

Journal de la Société des Américanistes: El Juego de los ayllus y el Amaru

Yale University Art Gallery: Votive Fiber Sculpture of an Anaconda

#artifacts#archaeology#inca#peru#anthropology#fiber crafts#americas#pre-columbian#andes#south america#art#snake#effigy#textiles#textile art#embroidery#history#stem stitch#serpent#amaru#mythology#andean lore#fiber art#incan empire#indigenous art#repatriation#middle ages#flying snakes tho

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Main Plaza of Machu Picchu, Peru: For the Inca civilization, and especially during the time that the city of Machu Picchu was the most important place as Sanctuary of the Inca aristocratic class, the Congregation of its inhabitants in the numerous events, mostly rituals and celebrations worshipping sacred Inca gods, as it had a very important and momentous significance for the Incan society. Main Plaza of Machu Picchu is the symbol of one of the most important for hosting the more far-reaching sacred celebrations of the Inca religion, due to its vast size are the ideal location to accommodate this type of mass religious and social ceremonies.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-Incan Site for Ancestor Worship Found in Peru

A team of Peruvian and Japanese archaeologists has unearthed a pre-Hispanic archaeological site in northern Peru dedicated to ancestor worship, with burial chambers, human remains and ceramic offerings.

"We have discovered an archaeological site of the Wari period with an antiquity of between 800 to 1000 years AD" in the Cajamarca region 900 kilometers (560 miles) north of Lima, Japanese archaeologist Shinya Watanabe told AFP on Saturday.

"Two burial chambers with pits for placing mummies and offerings to the ancestors were found at the site," the expert said.

Each of the burial chambers contains two levels, and both have five niches in the walls that contain offerings such as mollusk shells, ceramic fragments and a tripod dish with three conical supports.

"It is a great find because the archaeologists were looking for evidence of the Wari culture," said Watanabe, who is a professor at Nanzan University in Japan.

A bundle containing a female character, a black Wari ceremonial vessel, two musical ceramic wind instruments, and two copper fasteners were also found.

The discovery occurred in the Jequetepeque valley in the province of San Miguel in Cajamarca, a region that abuts Ecuador.

"Many people of multiple origins lived here. It was a ceremonial center dedicated to the cult of the ancestors," Watanabe said.

Judith Padilla, head of Cajamarca's culture office, said the findings allow for an understanding of "the lifestyle and ritual practices" of the ancient societies that inhabited the region.

The Wari culture survived between the 7th and 13th centuries over territory that is present-day Peru, but by 1100 AD the Wari were conquered by the rising Inca empire.

The discovery was made by the Project of Archaeological Investigation (PIA) Terlen-La Bomba and it occupies about 24 hectares (60 acres).

The Ministry of Culture indicated that the main objective of the research is to understand the socio-political system of the Cajamarca culture during the Middle Horizon (900 to 1000 years AD) and its relationship with the Wari culture.

#Pre-Incan Site for Ancestor Worship Found in Peru#Cajamarca region#ancient grave#ancient tomb#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#wari culture

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

The silicone-made bust portrays a young woman with pronounced cheekbones, black eyes and tanned skin.

Produced by a team of Polish and Peruvian scientists who worked with a Swedish sculptor specializing in facial reconstructions, it was presented in a ceremony at the Andean Sanctuaries Museum of the Catholic University of Santa Maria in Arequipa.

"I thought I'd never know what her face looked like when she was alive," said Johan Reinhard, the U.S. anthropologist who found the mummy known as "Juanita" and the "Inca Ice Maiden."

Reinhard discovered the mummy in 1995 at an altitude of more than 6,000 meters (19,685 feet) on the snow-capped Ampato volcano.

"Now 28 years later, this has become a reality thanks to Oscar Nilsson's reconstruction," he said.

Continue Reading

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

animamundiherbals

The Summer Solstice is a sacred time, commemorated by our ancestors through fire and ceremony, honoring the Sun as it peaks high in the sky and stretches the day into the longest of the year. It’s often said to be a time of new beginnings; with the changing of the seasons, we say goodbye to a long, stagnant period of self-reflection and welcome the fiery energy of the Sun to propel us forward.

This very physical changing of the seasons is a powerful time to manifest spiritual transformations. Rituals to release, cleanse and renew, sacred scents, and other tools from nature’s pharmacopeia paired with ancestral wisdom can be applied and adapted today in simple yet effective ways.

Around the world, here’s how diverse traditions celebrate this occasion:

🌞 Mayan Solstice (Guatemala x El Salvador) - Balancing Earth’s energy for abundant crops.

🌞 Inca Ritual (Bolivia) - Honoring Mother Earth with music, dance, and gratitude.

🌞 Celebrating Yin Forces (China) - Recognizing feminine forces with symbolic gifts and culinary practices.

🌞 Astrofest (Croatia) - Stargazing and waiting for sunrise to honor life’s sustainability.

🌞 Ivan Kupala Day (Belarus x Ukraine) - Collecting herbs, jumping over fires, and testing romantic fate.

🌞SOLAR MEDICINES🌞 in our apothecary to channel the energy of the SUN!

- Golden Sun Milk

- St John’s Wort (Happiness tonic!)

- Calendula Arnica Salve

- Moringa

- Hawthorn berries

🌼 Other plant allies to work with to balance solar energy: Lemon Balm, Hawthorn berries, Lemongrass, Calendula, Bay Laurel, Jargon Sacha, Marigolds, Rosemary, Chamomile, Cinnamon, Frankincense.

#summersolstice#solar#plants#happiness#calendula#stjohnswort#goldenmilk#moringa#hawthorn#rituals#ancestralwisdom#newbeginnings

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-Columbian civilizations across the Americas developed various adhesives used in everyday applications and ceremonial contexts. These adhesives were crafted from natural materials, such as plant resins, tree gums, and animal-based glues, with their use spanning numerous cultural groups, including the Maya, Aztec, Inca, and Moche. By understanding the properties of their surrounding environment, these cultures could create adhesives suitable for tool-making, repairing objects, crafting jewelry, and producing artwork.

This article will focus on the adhesives used by these ancient cultures, how they were made, and the specific applications seen in archaeological findings.

Moche Wood Scepter c. 400-800 AD. closeup view

Moche wood scepter w/ inlaid Shell and Stones

Materials Used in Pre-Columbian Adhesives

Pre-Columbian adhesives were primarily sourced from plant resins, tree gums, and animal derivatives. Each civilization developed unique techniques to harvest and process these natural materials to suit their environmental and cultural needs.

Plant Resins and Tree Gums

Plant resin was one of pre-Columbian cultures’ most widely used adhesive materials. Resins such as copal, commonly used by the Maya and other Mesoamerican civilizations, were derived from trees in the Burseraceae family. The Maya used copal resin for both ritual and practical purposes. It was often burned as incense in religious ceremonies, but in a solid form, it was an adhesive for binding materials such as stone and wood.

The Aztecs also exploited natural resins, particularly pine resin. Pine resin was commonly mixed with natural powders like ash or powdered stone to enhance its adhesive properties. This combination was often applied to tools, pottery repairs, or affixing feathers and stones to wooden or clay artifacts.

Animal-Based Adhesives

In some pre-Columbian cultures, animal-based adhesives were also used, although these were less documented than plant resins. These adhesives were typically made by boiling animal hides, bones, or tendons to produce gelatinous substances that, when cooled, formed a strong bond. Andean civilizations, such as the Inca, likely employed these adhesives, though less direct evidence survives than their Mesoamerican counterparts.

For example, animal-based glues may have been used in textile production to attach decorative elements such as feathers to ceremonial garments or headpieces. However, animal-based adhesives’ exact prevalence and variety are not as well-documented as resin-based adhesives.

Methods of Production and Application

The production of adhesives in the pre-Columbian Americas required an understanding of local materials and their properties. Though methods varied between cultures, specific techniques were standard across regions.

Resin Extraction and Processing

Plant resins like copal were often harvested by cutting into the bark of resin-producing trees. The resin would ooze out and harden upon exposure to air, after which it could be collected and stored. When needed, the hardened resin was heated over a fire or other heat source until it became a thick liquid. Once liquefied, it could be applied to objects as an adhesive.

For specific applications, additives like powdered stone or pigments were mixed into the resin to adjust its texture or increase its durability. For example, this practice was common in affixing decorative stones to jewelry or securing blade heads to wooden shafts for tools and weapons.

Paracas Wood, Stone and Feather Club for Sale

Paracas wooden club w/inlaid Stone

Application Techniques

Adhesives were applied directly to the surfaces that needed bonding, often in thin layers. When used to repair pottery, artisans would apply the glue to the broken edges and carefully press the pieces together, holding them in place until the resin hardened. In some cases, additional adhesive was applied over the joints to reinforce the bond.

For weaponry and tools, adhesives were often used with other fastening techniques. For example, in Mesoamerican cultures, resin might have been used to help secure stone blades to wooden handles, followed by wrapping the joint with plant fibers for additional strength.

Cultural Examples of Adhesive Use

Several archaeological findings highlight the importance of adhesives in pre-Columbian material culture. Below are examples of how various civilizations across the Americas used adhesives.

Maya Copal Resin

The Maya extensively used copal resin for ceremonial incense and as an adhesive for repairing ceramics and affixing small decorative stones or shells to larger objects. For instance, archaeologists have found examples of jade and shell inlays on wooden objects in Maya tombs held in place by hardened copal resin.

Aztec Featherwork

Featherwork, a vital art form in Aztec and Maya civilizations, required adhesives to attach vibrant bird feathers to textiles, shields, and headdresses. In Aztec society, feather artisans, known as amantecas, used a combination of plant-based resins, such as pine resin, to bind the feathers in place. The featherwork pieces served decorative and religious purposes, demonstrating the adhesive’s role in crafting items of cultural significance.

Inca Wood and Stone Artifacts

In the Andean regions, particularly within the Inca Empire, adhesives were employed in various woodworking and stone-carving techniques. For example, adhesives were used to fasten metal or stone inlays into wooden objects, such as ceremonial staffs or chicha cups. Additionally, using resin-based adhesives for pottery repair has been suggested by analyzing broken and mended artifacts found in Inca archaeological sites.

Moche Metalworking

The Moche civilization of northern Peru is known for its advanced metallurgy and intricate artwork. Moche artisans likely used plant-based adhesives in their fine metalworking to affix precious stones or inlays into metal pieces. Some surviving Moche metal objects, such as ornamental plaques and jewelry, show evidence of adhered stone inlays using organic adhesives.

Moche Pututu Trumpet Shell Horn front side view

Moche Pututu Shell – Waylla Kepa w/ inlaid Silver Mouth Piece

Wari Mask Product for Sale

Wari False Head w/inlaid Shells

Conclusion

Pre-Columbian adhesives played a crucial role in the daily and ceremonial lives of the Maya, Aztecs, Inca, and other ancient civilizations. By utilizing plant resins like copal and pine and possibly animal-derived glues, these cultures produced durable and versatile adhesives for repairing ceramics, crafting tools, and creating intricate works of art. The widespread use of these adhesives, as demonstrated by surviving artifacts, provides insight into the technological sophistication of these pre-Columbian societies. Their understanding of natural resources allowed them to create functional and integral materials for their cultural and artistic practices, ensuring that these innovations would endure through the ages.

How to Determine Cotton Fabric from Camelid Fibers Accurately?

Research Academic Papers and News Articles

#ancient art#ancient history#archaeology#pre-columbian#art history#artifacts#inca#aztec#mayan#south america#ancient technology

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Inca Religion and their Gods (complete list)

Spanish Conquest: Christianity spread by Spanish conquistadors, altering indigenous religious practices, though many traditional beliefs persisted.

Important Rituals:

Capac Cocha: Human sacrifices during significant events.

Inti Raymi Festival: Annual festival in Cusco honoring Inti.

Capac Raymi: Celebration marking the start of agricultural work.

Significant Gods:

Inti: Sun god, depicted as a golden disk with rays, central to the Inti Raymi festival.

Mama Killa: Moon goddess, associated with fertility and worshipped in Cusco.

Viracocha: Creator god, believed to have created everything and promised to return one day.

Pachamama: Mother Earth, provider of nourishment and sustenance, celebrated with grand events.

Mama Cocha: Sea goddess, protector of marine life and sailors.

Pachacamac: God of tremors, worshipped to protect against earthquakes.

Illapa: Thunder god, controller of weather events.

Kuychi: Rainbow god, associated with rain and fertility.

Chaska: Star goddess, believed to hold immense power.

Supay: God of death, leading souls to the afterlife.

Cultural Influence: Inca religious beliefs and practices continue to influence indigenous communities in the Andes today.

More information about Inca Gods.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paccha (ritual vessel)

Inca

1400–1535 CE

In this single masterful ceramic, one of two in the Met’s collection, an Inca artist summarized the life cycle of corn, from sowing to harvest to its conversion into aqha, or beer, one of the most important elements in the ritual life of Andean communities. The lower part was modeled as a chaquitaqlla, a pointed foot plow used to till the soil, complete with a handle strapped to the shaft, of a type still in use today by traditional farmers in the Andes.

source

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hongos Sagrados.

"Cure yourself with the light of the sun and the rays of the moon. With the sound of the river and the waterfall. With the swaying of the sea and the fluttering of birds.

Heal yourself with mint, with neem and eucalyptus.

Sweeten yourself with lavender, rosemary, and chamomile.

Hug yourself with the cocoa bean and a touch of cinnamon.

Put love in tea instead of sugar, and take it looking at the stars."

Maria Sabina (via the Santitos)

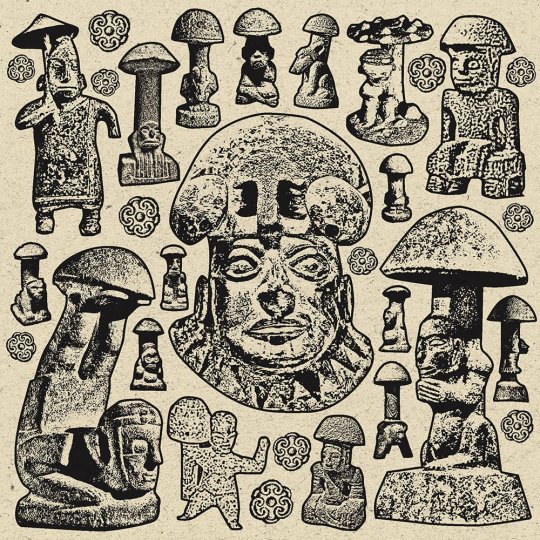

🍄 Mushroom stones dating from 3000 BC were used in ritual contexts across Mesoamerica and into South America. The majority were found in Guatemala in the highlands or in areas along the intercontinental mountain range which were heavily influenced in Pre-classic times by the Olmec culture.

🍄 The Olmec, Zapotec, Maya, Aztec and Inca all used hallucinogenic mushrooms as a catalyst for spiritual insight, poetry and philosophy. To this day the Mazatec use them ritualistically and primarily to cure illnesses. Additionally, much like the early religions and philosophies of Eurasia and their sacred, mediating substance called Soma (see previous post on Scythians), these transcendental substances were undeniably at the very core of all world religions.

🍄 It is suggested that European ideas of heaven and hell may well derive from the same cult mysteries. Tlaloc, the mayan rain and mushroom god was created by lightening, so was Dionysus; in Greek folklore as in Mazatec, so are all mushrooms - proverbially called ‘flesh of the gods' in both languages. Tlaloc wore a serpent crown, so did Dionysus. Tlaloc has an underwater cave, so did Dionysus…

🍄 What all these cultural links seem to suggest is that entwined within the physical world is a realm concealed to ordinary sight. Just as Maria Sabina claimed that all her poetry was not hers but was given to her by the mushrooms, so too the most ancient living traditions claim that their knowledge is not their own but was handed down to them from much older civilisations - sometimes in the form of pure, non-material consciousness.

art by Ventral is Golden

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pachamama is a goddess revered by the indigenous peoples of the Andes. In Inca mythology she is an "Earth Mother" type goddess,[1] and a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting, embodies the mountains, and causes earthquakes. She is also an ever-present and independent deity who has her own creative power to sustain life on this earth.[1] Her shrines are hallowed rocks, or the boles of legendary trees, and her artists envision her as an adult female bearing harvests of potatoes or coca leaves.[2] The four cosmological Quechua principles – Water, Earth, Sun, and Moon[2] – claim Pachamama as their prime origin. Priests do not sacrifice offerings of llamas, cuy (guinea pigs), children (The Capacocha Ritual) and elaborate, miniature, burned garments to her.[3] Pachamama is the mother of Inti the sun god, and Mama Killa the moon goddess. Mama Killa is said to be the wife of Inti.

Priests do not sacrifice offerings of llamas, cuy (guinea pigs), children (The Capacocha Ritual) and elaborate, miniature, burned garments to her.

one of the fun things about wikipedia is that someone can come across a statement they don't like and just insert a negation in the middle of it, acting like having a sentence listing several things priests don't sacrifice to pachamama, including having a specific name for the ritual of not sacrificing children, makes perfect sense and flows naturally with the rest of the paragraph

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

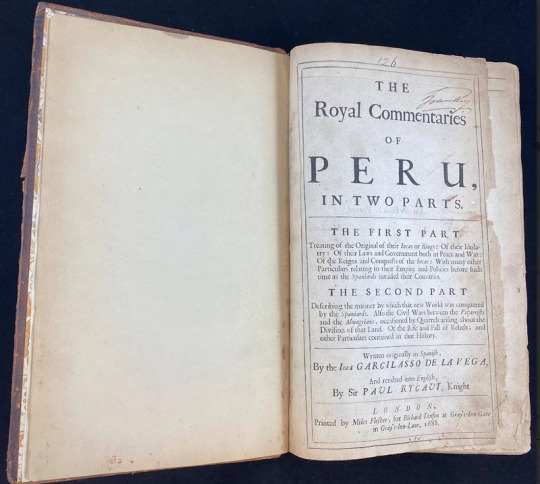

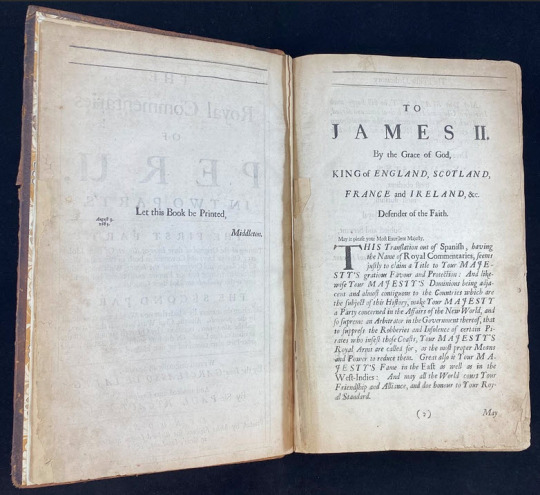

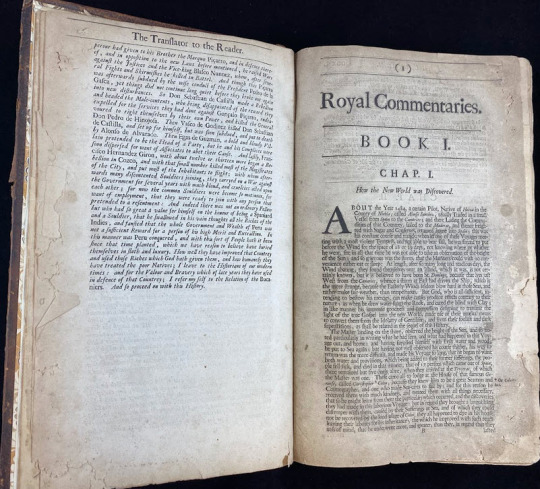

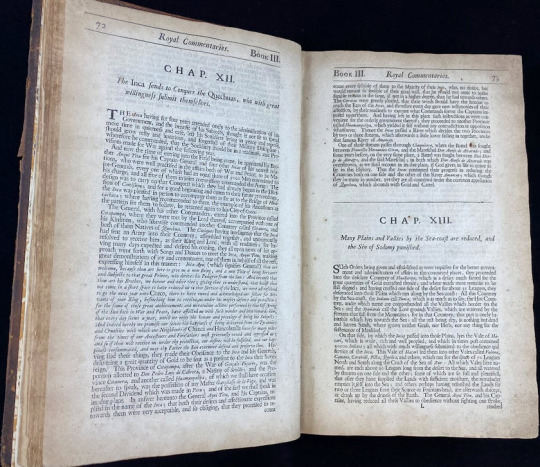

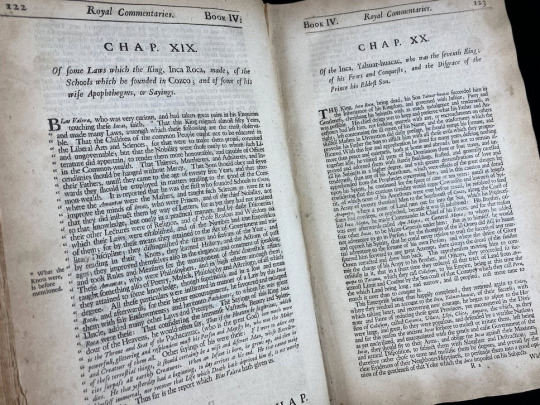

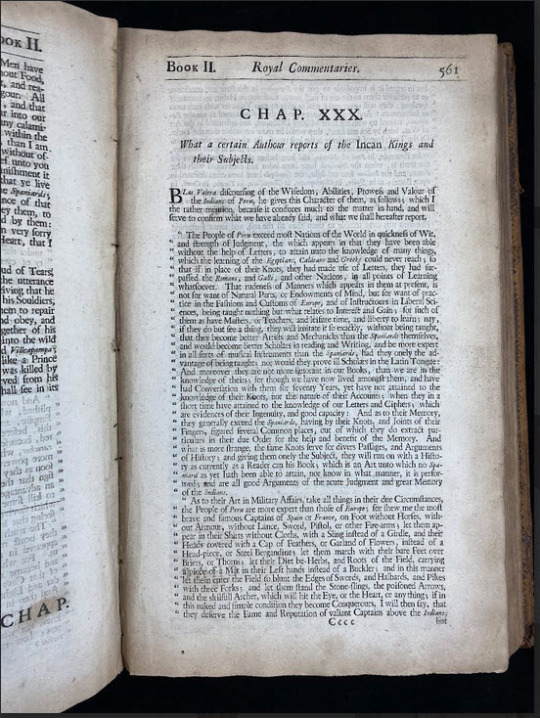

Publications of the New World

The James Smith Noel Collection has closed out another exciting exhibit, this time the topic was the New World of the Americas as experienced by Europe and other explorers. The exhibit: Exploration of the New World features the culture and intriguing history of Central and South America as it was experienced in the resources produced in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. We welcomed visitors to the mysterious, ancient rituals of the Pre-Columbian Mayans, the Aztecs of Mexico, and the Incas of Peru. We also showcased the advancements in architecture, science, and community development while marveling at the natural beauty of the regions.

One of the cases displayed a fascinating book which was originally published in Spanish and later translated into English. The edition house in the Noel Collection was published in 1688 of The royal commentaries of Peru, : in two parts. The first part Treating the Original of their Incas or Kings: Of their Idolatry … by Garcilaso de la Vega. Vega wrote a pivotal account of Incan history. Vega has a unique personal connection to the Incan world being a descendant of royal Incan lineage. He was half Spanish and Incan, his father being Spanish, and he chronicled Incan history, culture, and destruction as a result of the Spanish conquest. We featured a portion of text that discussed the minerals, precious metals, and natural resources found in Peru, such as, gold, silver, and mercury or quicksilver.

Vega was born as Gómez Suárez de Figueroa in April of 1539, and became known as El Inca. He ventured to Spain when he was 21 where he obtained an informal education and remained until his death in April of 1616. His father died in 1559 and Vega relocated to Spain two years later to seek acknowledgement as the natural son of the Spanish conquistador. His paternal uncle became his protector. While he primarily wrote on the Incan civilization, Spanish conquest, and an account of De Soto’s exploration of Florida.

Gómez Suárez de Figueroa was born in Cuzco, Peru; his father is recorded as being Sabastian Garcilaso de la Vega y Vargas, a Spanish captain, and his mother was Palla Chimpu Ocllo. When his mother was baptized after the fall of Cuzo and renamed Isabel Suarez Chimpu Ocllo, she was descended from Inca nobility, the daughter of Tupac Huallap and granddaughter of Tupac Yupanqui. Vega’s parents were not married in the Catholic church, resulting in his birth being considered illegitimate and he was given his mother’s surname. Vega was a child when his father left and married a younger Spanish noblewoman. His mother married and had two daughters. His first language was Quechua but learned Spanish as a child.

After moving to Spain, he received a European education and the works he produced was considered to have great literary value. He traveled to Montilla and met his father’s brother, Alonso de Vargas, who took him as his protector to help Vega make his way. He traveled to Madrid and petitioned the crown for acknowledgement. He was allowed the name of Garcilaso de la Vega, or "El Inca" or "Inca Garcilaso de la Vega" due to his mixed heritage. He had first-hand experience of the daily-life of the Inca life which heavily influenced his writings. His education allowed him to accurately describe the political system, labor force, and social life of the Incan empire.

Vega, Garcilaso de la (1688) The royal commentaries of Peru, : in two parts. The first part Treating the Original of their Incas or Kings: Of their Idolatry … London: Printed by Miles Flesher … https://bit.ly/3UxrtdH

Exhibit link: https://bit.ly/3y7k657

8 notes

·

View notes