#archaeological analysis

Text

By Erin Blakemore

October 25, 2023

More than 500 years ago, a 14-year-old girl was escorted up an Andean peak and sacrificed to Inca gods.

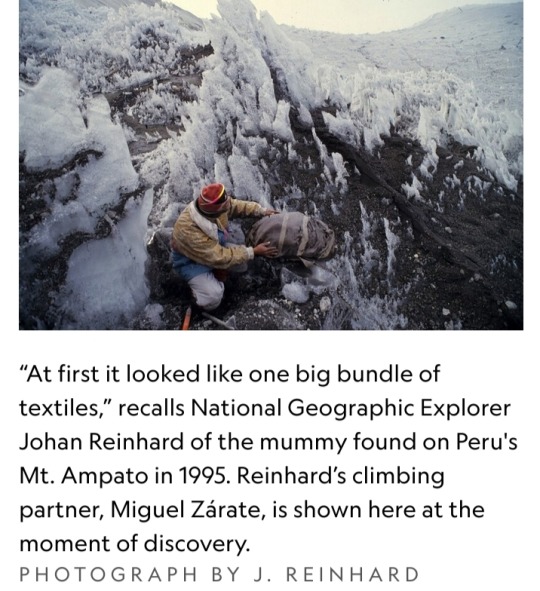

Buried on the mountain with a variety of offerings, the young woman’s body naturally mummified over time, preserving her hair, her fingernails, the colorful robes she wore on her last day.

But at some point across the centuries, her face became exposed to the elements, her features slowly vanishing over seasons of sunlight and snowfall.

Now, that long-lost face has been recovered thanks to painstaking archaeological analysis and forensic reconstruction.

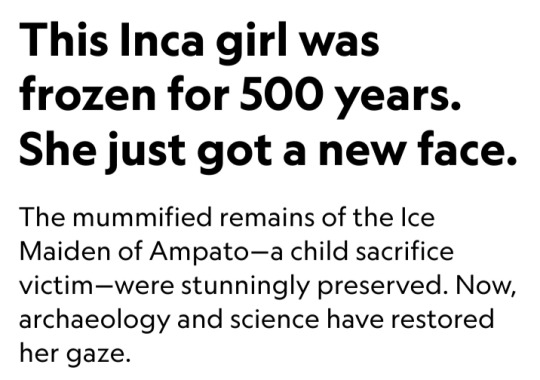

A striking 3-D bust of the young woman, known today as the Ice Maiden of Ampato, is the centerpiece of a new exhibit in Peru and part of an ongoing effort to understand the drama of human sacrifice practiced in the Andes half a millennium ago.

A sacrificial offering

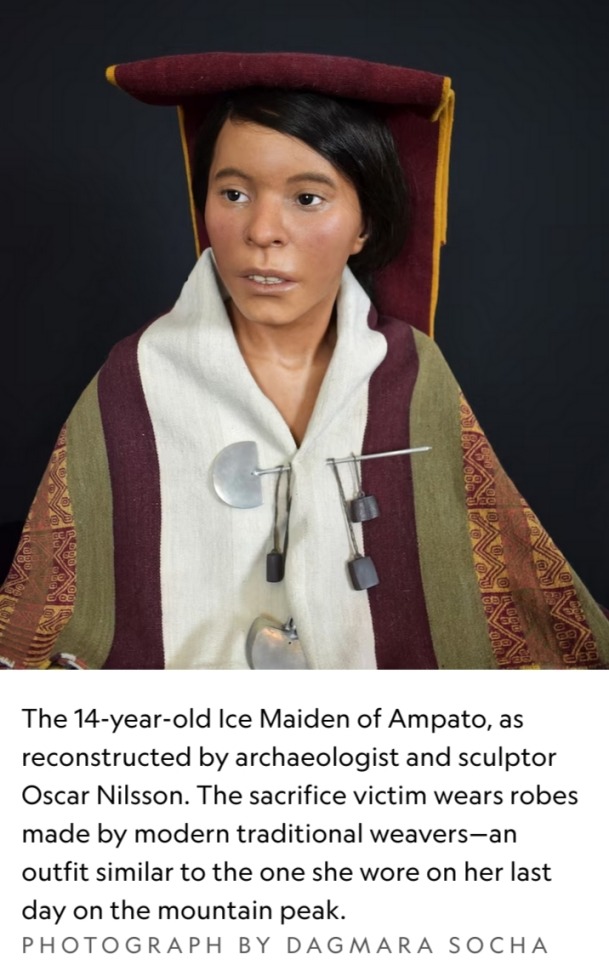

When National Geographic Explorer Johan Reinhard encountered the mummy, also known as Juanita, atop 21,000-foot Mount Ampato during a 1995 expedition, he knew he had discovered something spectacular.

“At first it looked like one big bundle of textiles,” Reinhard recalls. Then he saw the wizened face amid the folds of fabric.

Here was a young victim of the elusive Inca ritual known as capacocha.

Capacocha mostly involved the sacrifice of children and animals who were offered to the gods in response to natural disasters — to consolidate state power in far-flung provinces of the Inca Empire, or simply to please the deities.

The ritual played an important part in sustaining the Inca Empire. It would involve feasts and grand processions to accompany the children, who appear to have been chosen for their beauty and physical perfection.

Being selected for sacrifice, researchers believe, would have considered a deep honor by the child’s family and community.

Most of the information we have on capacocha, however, is second hand, notes Dagmara Socha, an archaeologist with the Center for Andean Studies at the University of Warsaw who studies the ritual and commissioned the facial reconstruction of the Ice Maiden of Ampato.

“No European colonist ever saw the ceremony,” she explains.

Despite gaps in the historical record, the high-altitude archaeological finds of more than a dozen Inca children on Ampato and other mountains point provide critical evidence for what happened during these rituals.

The means of sacrifice varied, perhaps due to customs related to specific gods. Some children were buried alive or strangled; others had their hearts removed.

The Ice Maiden’s life ended with a single blunt-force blow to the back of the skull.

In search of the Ice Maiden

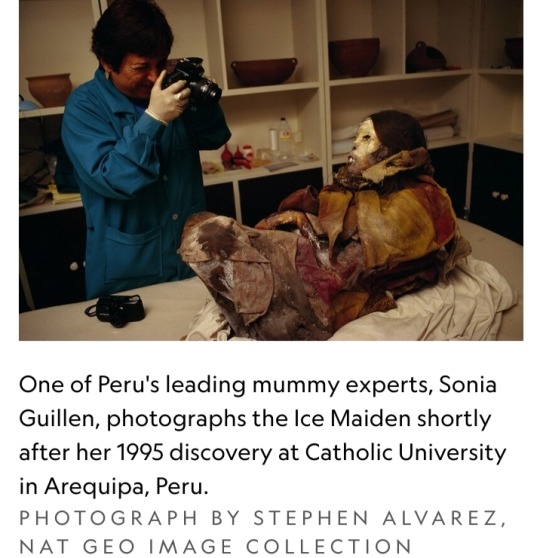

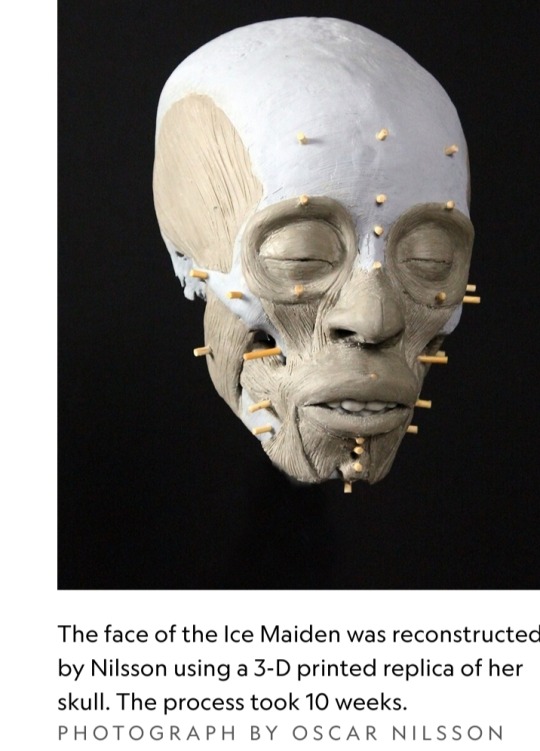

Oscar Nilsson knows that skull intimately: He spent months with a replica of it in his Stockholm studio, eventually fashioning a sculpture of the 14-old-girl that, glimpsed from afar, almost seems alive.

It’s a two-step process, says the Swedish archaeologist and sculptor.

First, Nilsson immerses himself in the world of his subject with an archaeologist’s eye for detail, digesting as much data as possible to understand what she might have looked like.

Even without a mummified face, he can extrapolate the likely depth of the facial tissue that once draped over those bones, using everything from CT scans to DNA analyses to information about diet and disease to make educated guesses about the individual’s face.

Then came the handiwork. Nilsson printed a 3-D replica of the Ice Maiden’s skull, plugging wooden pegs into its surface to guide the depth and placement of each hand-crafted, plasticine clay muscle.

Eerie eyes, masseter muscles, a nose, the delicate rope-like tissues that constitute a human face: each was added in turn.

After making a silicone mold of the bust, he added hundreds of individual hairs and pores in shades of brown and pink.

It took ten weeks.

Following the Inca Gods

The result, wrapped in robes woven by local women from Peru's Centro de Textiles Tradicionales, is the main attraction at “Capacocha: Following the Inca Gods” at the Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa, Peru through November 18.

The reconstruction will be displayed alongside the Ice Maiden’s mummy, accompanied by the stories of 15 other children selected for capacocha atop Ampato and other Andean peaks.

Their ages range from 3 to about 13. The mummies and skeletal remains of several are featured as 3-D models at the exhibition, which also showcases holographs of some of the sacred items buried alongside them.

These natural mummies offer scientists tantalizing clues about their last days.

When Socha and colleagues conducted toxicological and forensic analyses of the remains of a toddler and four six-to-seven-year-old victims featured in the exhibition, they found they were well cared for in the months before their sacrifice.

They were fed a steady diet of coca leaves, ayahuasca vine, and alcohol in the weeks before their deaths — not as much to intoxicate them as to keep them sedated and anxiety-free as the timeline hurtled toward their sacrifice.

“We were really surprised by the toxicology results,” says Socha.

“It wasn’t only a brutal sacrifice. The Inca also wanted the children to be in a good mood. It was important to them that they go happily to the gods.”

High altitude, psychogenic substances, the spectacular view, the knowledge the afterlife was near — all must have made for an astonishing ceremony, says Reinhard.

“The whole phenomenon must have been overpowering.”

During the last phase of his reconstruction, Nilsson spent hours contemplating and attempting to capture the young girl’s presence 500 years after her death.

The result is both unsettlingly realistic and jarringly personal.

“She was an individual,” the forensic reconstructionist says.

“She must have understood her life would end on the mountaintop in a couple of weeks. We can only hope that she believed in the afterworld herself.”

For Reinhard, finally seeing the face of the girl he carried down the mountain on his back decades ago brought the Ice Maiden’s story full circle.

“It brings her back to life,” he says. The reconstruction brings the focus as much to her culture and daily life as to her spectacular death.

But Nilsson never forgot the way the Ice Maiden died, even as he brought her to life through his reconstruction.

More than anything, he says, he wanted to capture a sense of being frozen — a nod not just to her icy, mummified future but to a girl teetering on the edge of eternity, though still very much alive.

“She knew she was supposed to smile, to express pride,” he says. “Proud to be chosen. But still very, very afraid.”

#Ice Maiden of Ampato#Inca Girl#archaeological analysis#forensic reconstruction#human sacrifice#Peru#3-D bust#Juanita#Johan Reinhard#Mount Ampato#National Geographic#National Geographic Explorer#expedition#1990s#20th century#capacocha#Inca ritual#Inca Empire#Dagmara Socha#facial reconstruction#archaeology#archaeologists#Oscar Nilsson#sculptor#Centro de Textiles Tradicionales#Capacocha: Following the Inca Gods#Museo Santuarios Andinos#natural mummies#culture#forensic reconstructionist

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

of Flanagan's chronical chronology mess-ups and all age inconsistencies it involves, I find Crowley and Halt's first meeting story the most hilarious

Crowley describing Halt as a intimidating dark man? Who's probably at least few years younger than Crowley.

And in this exact scene-

Halt: I hit your men with an arrow 😉😜

Morgarath: ... where

Halt: at the inn 😁

Morgarath: I asked about the body part

And at the time he chooses to call himself Halt Halt deliberately, as a joke.

He's eighteen (18), guys.

They are all talking to a runaway emo-aligned teenage short king prince and go "oh he's SO intimidating" while he drinks his coffee black and sweetened.

#rangers apprentice#halt o'carrick#crowley meratyn#lost stories flanagan#book analysis? does that count as an analysis?#it have been ages since ive read the series and oh god#im crying there are so many things about it i need to reconsider#im gonna make a way too long weapon analysis from archaeological pov :)

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twenty thousand years ago, someone dropped a deer-tooth pendant in a cave in southwestern Siberia, where it lay until archaeologists excavated it in 2019. Now, researchers have caught a glimpse of its last wearer. After years of effort, Elena Essel, a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (EVA), developed a way to extract DNA embedded in an artifact’s porous surface by sweat and skin cells. Her team’s analysis of the ornament, reported this week in Nature, shows it once adorned a woman whose ancestry lay far east of the cave.

“It’s the first time to my knowledge that we have a nondestructive way to extract DNA from Paleolithic artifacts,” says co-author Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University. The technique promises a window into how, and by whom, ancient ornaments and tools were used. Human DNA gleaned from their surfaces could offer “new insight into cultural practices and social structure in ancient populations,” says evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The EVA team found some of the ancient DNA came from wapiti, the species of elk whose tooth was used to make it. But some DNA was from a female modern human; its sequence revealed she was most closely related to people of the Maltinsko-buretskaya culture, known to have lived 2000 kilometers farther east near Lake Baikal—and who are among the ancestors of Siberians, Native Americans, and Bronze Age steppe herders. By comparing the DNA from both the woman and the elk with other ancient samples, the researchers dated the pendant to between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago.

The paper has come out just in time for a new field season, Essel says. She has a request for colleagues as they unearth new artifacts: “Please, please, please wear gloves and face masks if you want to look at the DNA of the people who were making these things and using them.”

In theory, such analyses are most promising for artefacts made from animal bones or teeth, not only because they are porous and thereby conducive to the penetration of body fluids (for example, sweat, blood or saliva) but also because they contain hydroxyapatite, which is known to adsorb DNA and reduce its degradation by hydrolysis and nuclease activity. Ancient bones and teeth may therefore function as a trap not only for DNA that is released within an organism during its lifetime and subsequent decomposition but also for exogenous DNA that enters the matrix post-mortem through microbial colonization or handling by humans.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06035-2

#elena essel#marie soressi#paleoanthropology#archaeology#dna analysis#wearer of adornment#identified by#25000 year old sweat#wild

336 notes

·

View notes

Note

you're reading homestuck? why would you do that to yourself?

it's a fairly culturally relevant piece of media at this point. i want to understand its impact and be able to have an informed perspective on it. also it apparently has some characters and narrative themes that i'd enjoy.

#honestly im really stoked to study something as broad in scope as homestuck because i love picking apart everything i read/watch/listen to#so this is like diving into a massive archaeological dig site for literary analysis#james reads homestuck

432 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Evil is My Good - Pyramids of Mars, 1975

There are some things, though not many, that the Doctor Who fandom seems to universally agree on. Everybody seems to agree that the Weeping Angels are a great, iconic monster. Everybody seems onboard with the notion that The Caves of Androzani is one of the best stories of all time. Everybody seems to agree that the Hinchcliffe era is one of the most consistently good runs in the whole show. You can probably see where I am going with this. Pyramids of Mars has been forever lauded as one of the all-time great Doctor Who stories, a shining example of a show that appealed to all ages at the peak of its powers.��

Like all consensus opinions, there is obviously a clear logic to this. Pyramids of Mars is incredibly memorable and influential. It was, after all, the third serial to be released on the VHS line and it topped the DWM poll for most anticipated DVD release in 2003. Even if it were not so formative and prominent in fan's minds (the amount of times it has been selected for re-release and repeat is remarkable) it would still be one of the most influential and groundbreaking stories of its time. It is hard to challenge the claim that Pyramids of Mars is the single most important story of the Hinchcliffe era. Not the best (there are at least four prior to this that could more readily stake that claim) but, in an aesthetic sense, the pilot episode for the Hinchcliffe era or, at least, the one where everything finally falls into place.

Prior to Pyramids of Mars, Doctor Who had functioned primarily based on the approach pioneered by Verity Lambert and David Whittaker back in the early 1960s. Their vision of Doctor Who was as a programme defined by juxtaposing aesthetics and the storytelling had developed to facilitate that by colliding genres and styles of storytelling. What debuts in Pyramids of Mars is, in hindsight, the inevitable next step which is positioning the established aesthetics and logic of Doctor Who alongside specific pulp genre stories. The difference is the distinction between the Doctor walking amongst a space opera or a western and disrupting their logics and aesthetics and the Doctor walking around within 1971’s Blood of the Mummy’s Tomb and being beholden to its logic and aesthetic.

In the 1990s, Steven Moffat infamously derided the Hinchcliffe era for comprising too largely of derivative pastiches and, while I ultimately agree with him, he is made to look a bit of a fool because of how much the approach does actually work. I like Pyramids of Mars. Of course I do. I'm a Doctor Who fan. This story is a blast to watch and it is the first in a really strong run of pulpy, gothic horror-pastiches that define the Hinchcliffe era in everybody's minds (I stress this is not the beginning of a run in terms of quality, just the start of an aesthetic period that also happens to be very good). This is a messy story but it is a very promising first showing. Pyramids of Mars proves that this model of Doctor Who can work and it lays the groundwork for better stories later down the track. after it to take this aesthetic and run into incredibly interesting places. So, as you have obviously concluded by now, this is not even close to my favourite of the Hinchcliffe era, let alone of all time.

Yes, the production of Pyramids of Mars is spectacular. Probably the single strongest aspect of the Hinchcliffe era is just how good the show was at working within its limitations. None of the stories under his watch look especially naff and Pyramids of Mars is especially luscious. The serial is dripping in tone and atmosphere and I could not begrudge anybody frequenting it for just the mood it puts you in. The sets for the house are great and effortlessly evoke that classic, hammer horror tone of an old, creepy house with creepy old dudes doing creepy *cult* (we can replace that word with *casually stereotypically racist*) stuff. The visual effects are also excellent with particular kudos to that chilling bit where Marcus gets shot. I could watch that one sequence forever.

This is not a script with a wealth of great material for the actors but there is no question that they are all exceptional. Paddy Russell even claimed as much herself, insisting upon finding strong actors to bolster material that she thought was lacking. Michael Sheard brings a lot to Laurence Scarman, the best part in the whole story from an acting perspective, but it is hard to look past Garbriel Woolf as Sutekh for the best guest performance in the serial. What a captivating voice and commanding presence. Tom Baker's performance is often praised for the seriousness and dread he brings to proceedings. He even has some particularly dark and alien moments such as his total detachment from the various deaths around him. In my opinion, however, I find his performance to be distant and disinterested, likely thanks to his frosty relationship with Russell. Luckily, it does serve this material well and offer an alienness to the role but he seems incredibly bored and pissed off every time he is onscreen.

As with this whole season though, Elisabeth Sladen is at the height of her powers and effortlessly wrings buckets of charm out of scripts that, again, serve her terribly. Following season eleven, it feels like nobody working on the show has any interest or even a take on the Sarah Jane that we were introduced to. Everybody who has ever seen this serial praises the scene where the Doctor leaves the events of the story for 1980 at Sarah's request and rightly so because it is a phenomenal sequence and possibly the most effective way to demonstrate how awesomely powerful the villain is in the whole show’s history. It's so good, of course, that Russell T. Davies had the good sense to nick it wholesale for The Devil's Chord. Everything aesthetically about Pyramids of Mars works. This is a great story to just watch and let wash over you.

However, I think that this script is deeply flawed and definitely needed another pass before it could attain true GOAT status in my books. Perhaps that will seem unfair to those who will cry out in defence with the reminder that this story was another late rewrite from Robert Holmes when the original scripts, from one time writer Lewis Griefer, were deemed unworkable. It is somewhat miraculous that this story even got made at all. It’s difficult to say now how much of the finished serial can truly be credited to whom. Greifer, was approached by Holmes, a former colleague, while headhunting new talent. Knowing he had a keen interest in Egyptian mythology, Holmes allegedly pitched the combination of science-fiction and a mummy horror film to him. Greifer’s scripts would have been radically different including the proposed final appearance of UNIT and the Brigadier, a scheme to solve world hunger with plantations on the moon year culminated in the Doctor uniting with Horus and Iris to take on the crocodile looking Seth and stop his plan to replace the grain and destroy the moon. It is from here that the development of the serial becomes very collaborative. Holmes met with Greifer and suggested a number of scaled-back alterations that were more in-line with what Doctor Who was suited to in 1976 as well as taking on suggestions from outgoing producer Barry Letts.

Greifer revised his scripts further to what would be the basic plot of the television version, moving the detecting to Earth with an imprisoned Seth and his rocket-based plans, with the added addition of a fortune hunter seeking the world-saving rice in an ancient Egyptian tomb. Holmes remained unhappy with the scripts and, to make matters worse, Greifer fell ill after delivering a full script for the first episode only. Following his recovery, Greifer then promptly left the UK to take on a job her previously committed to leaving Holmes to do a page one rewrite with the consultation of director Paddy Russell based on what had already been put in motion. With all of this fraught pre-production in mind, I still think this story is an undercooked mess. The first episode is fantastic and I really love the third but there is so much padding in episodes two and four that really drag the whole thing down for me. The entire second episode is just spent cutting between Sutekh killing people and the Doctor setting up a plan to stop him that fails immediately: The foundations of this serial are really strong and it has some great dialogue, characters and moments but the whole thing fails to hold together for me especially in regards to pacing and the real lack of any interesting subtext to sink your teeth into. There is not much to love here that is not aesthetic.

But let's try and dig a little deeper anyway. Broadly speaking, mortality seems to be the theme that connects the various elements of the story. We are first introduced to the Doctor in what is probably my single favourite shot of him in the whole seven years he was in the show. We meet him alone, in silence and brooding in the TARDIS control room. Sarah enters in what will be a coincidentally appropriate Edwardian dress, our first indicator that this story is really all about aesthetics and flavour more than anything else, and we discover that the Doctor is in somewhat of a mid-life crisis, grappling with the uncomfortable realisation that his life is marching on and that he has no real purpose. This is a really well written and performed scene, one of the best the Doctor and Sarah ever had, and probably my favourite of the serial. While the original show on the whole is not know for deftness of characterisation and development, Pyramids of Mars proposes a potentially interesting starting place for the Doctor’s character which is simply to put him in a somewhat depressed mood and unhappy with the prospect of spending his remaining days at U.N.I.T.‘s beck and call. This a Doctor who has lost his sense of purpose and ambition. It is a great idea that could reveal a lot about the Doctor and challenge his character, as we later saw under Moffat's creative direction, but it never goes anywhere here. Pyramids of Mars is a serial about a villain who does have a defined purpose and ambition – to bring death to all of reality. Yet the person best poised to stop him is in a crisis himself about the prospect of that very thing arriving for him. The character-driven story of a wandering hero in a mid-life crisis versus the Lord of Death should simply write itself.

But it doesn't. The Doctor does not walk away from the end of this adventure with a renewed sense of self or really any semblance of change in the morose feelings he expresses in episode one. It would have been perfectly forgivable if his mid-life crisis was something that the production team set-up here and went on to develop over the season but that never happens either. The Doctor is more than happy to assist U.N.I.T. in the very next serial and yet once more before the season wraps up. The elements are all here to ie the themes and character beats together but it never really happens. For example, I would love to confidently read something deeper into the final visual of the house burning down. It is, after all, the Doctor’s defeat of Sutekh that starts the fire and we know from episode one that, later down the track, the manor is going to be rebuilt and repurposed as the U.N.I.T. headquarters.

The thematic implications of this are really nice. Sutekh wants to end everything, leaving "nothing but dust and darkness", but we all know that the manor's destruction is an ultimately necessary consequence to allow for something good to rise up from its ashes. Life always prevails and begins anew. This is a simple enough thematic beat that could have been teased out and made a lot stronger and it could even have been a clear indicator of some character resolution. With the Doctor inadvertently facilitating the conception of U.N.I.T., this whole image could represent his coming to terms with his place in the universe after combatting Sutekh and passionately redefining himself and coming to terms with a now mythic role as a defender of all life in the universe, a champion of change and renewal. It is something almost there in the script but not quite.

The use of Egyptian iconography in this story is very clever. We know that death was an incredibly important aspect of their culture. People's corpses were mummified to preserve them for the afterlife since death was very much believed not to be the end. There is some cool world-building in this story and I really like the idea that Egyptian culture is all founded upon the wars of the Osirans (Osiris being the Egyptian god of the dead and of fertility). Sutekh is directly mentioned as being the inspiration for Set, realised as well as one could expect in his final beastly form, and the whole premise of the story is hinging upon his previous eternal imprisonment at the hands of brother Horus. I love that the bringer of death is punished by having an eternally unlived life. I think that this context is intended to be paralleled with Marcus and Lawrence. The pair are brothers and, for most of the story, the former literally is Sutekh.

Or, in another sense, it might be helpful to take the Doctor’s advice and consider Marcus as already dead. That plays nicely into the broader subtext we are reaching for here of exploring different relationships with death. Lawrence is in denial of his brother’s death since he sees him walking, talking and breathing. The Doctor thinks otherwise, confidently claiming Marcus to be dead already and no longer Lawrence’s brother now that his mind has been overtaken. We should note the Doctor and Sarah’s later scene too where she expresses a lot of sorrow over Lawrence’s death while the Doctor more or less just shrugs, if anything he comes off mildly annoyed, and refuses to deviate from the bigger priority of stopping Sutekh. It is a very memorable and somewhat disturbing scene, the likes of which the modern characterisation of the character never lends itself to. Even the Twelfth Doctor at his most callous was condemned by everybody around him and served his greater character growth. In the case of this moment, it is Sarah who is framed to be in the wrong for imparting human values upon the Doctor which is a potentially interesting notion but not a thread Holmes ever seems interested on pulling on again.

But I’ve digressed. There is potentially something very cool in the parallel between the four brothers but, again, the story is in dire need of another draft to really pull it to the fore. Lawrence is ultimately killed by his brother in quite a genuinely tragic moment since he is such a well performed and written character but the actual implications and significance of the scene beyond just the sheer shock value are ultimately lost on me. Marcus ends up never even knowing he did this, presumably, since he is killed the second he is freed from Sutekh. If Lawrence could be read as a parallel with Horus, or perhaps more closely of Osiris if we are considered the actual Osiris myth, what is this actually supposed to communicate? To depict for us that Sutekh would kill his own brother given the chance, as we know he did? That there is no humanity to appeal to with this villain? I am not sure of the intention but the scene, like this whole story, is almost fantastic.

And then there is the final episode. Every critic of this story before me has already torn this episode to pieces but I will just take it on briefly and note that the whole story just kind of falls apart at this point. The opening scenes with the Doctor and Sutekh are awesome but as soon as we actually get to the titular location, Holmes starts playing for time really hard. The first three episodes are already padded out to the max with extended woodland chases, an awkwardly large number of scenes where the Doctor and Sarah are simply walking to the poacher's shed and the entire character of the poacher himself in episode two who interacts with none of the main cast (save Marcus) and is just killed anyway. None of this blatant stretching of the script bends to breaking point thanks to how strong the production is at capturing the horror tone and aesthetic but the fourth episode is not so lucky. What we have here, for most of the episode, is an extended sequence of the Doctor and Sarah attempting an Egyptian themed escape room. This could have been compelling and some of the puzzles are kind of cool but the presentation is actually quite awful and the whole logic of this situation kind of escapes me. I suppose that Horus set these up to stop Sutekh’s followers from getting into the pyramid but does he just have the same voice as Sutekh? Is that what is going on?

It also does not help the story that this section is all shot on CSO and, aside from some great model work, looks incredibly cheap and bad. The serial takes a really shoddy nosedive but the biggest insult of this whole affair is simply that the whole episode is a colossal waste of time. The Doctor and Sarah accomplish nothing in going to the pyramid and just turn around to go back to the house to save the day with a totally different plan by the end anyway. Neither the characters nor the audience gain anything at all from the whole sequence.

Thus, this is the great conflict I have with Pyramids of Mars because I love watching it. I love the flavour of the story and the clear effort that everybody put in to make it the memorable, entertaining experience. For the most part, I am really sucked in by it. But it is not a masterpiece. In the end, there really isn't very much to say about it at all. This is a serial that feels like watching the tracks being laid when the train's already moving. It makes for a fun journey but the final destination is really shaky. Pyramids of Mars is exceptional in theory just leaves that little bit to be desired.

It is still a cracking story though. After all, this is mid-70s Who we’re talking about.

#doctor who#tv#analysis#behind the scenes#history#review#tom baker#4th doctor#classic who#fourth doctor#sarah jane smith#dw#sutekh#ruby sunday#fifteenth doctor#15th doctor#empire of death#legend of ruby sunday#the legend of ruby sunday#mrs flood#susan twist#pyramids#ancient egypt#archaeology

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

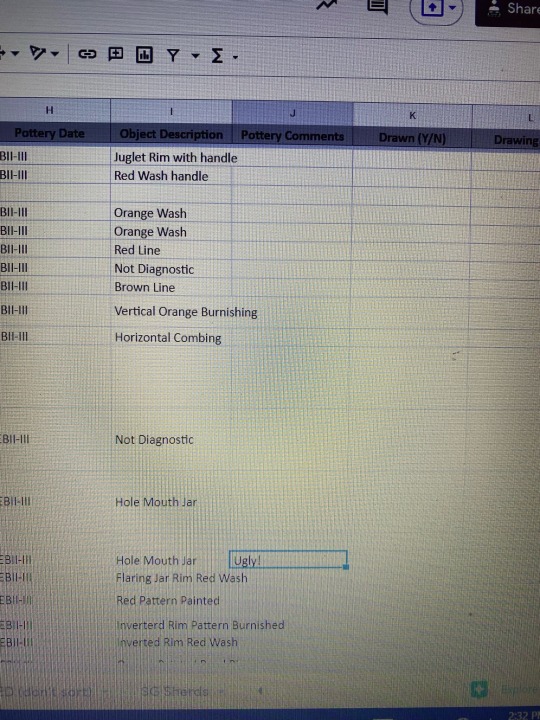

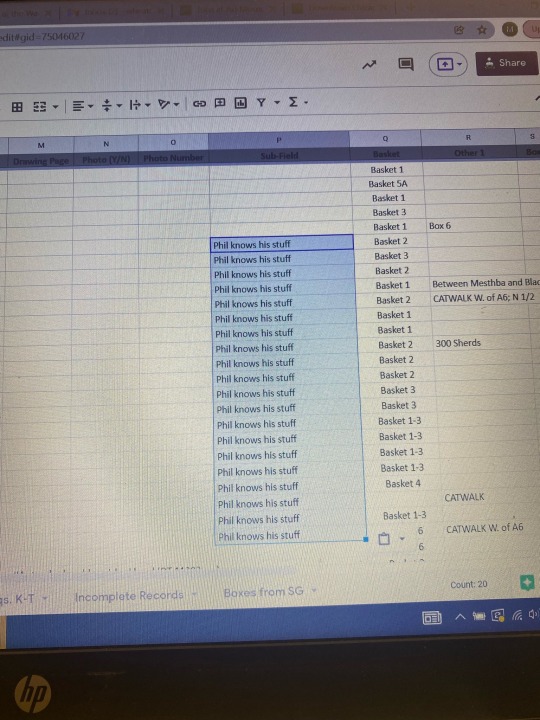

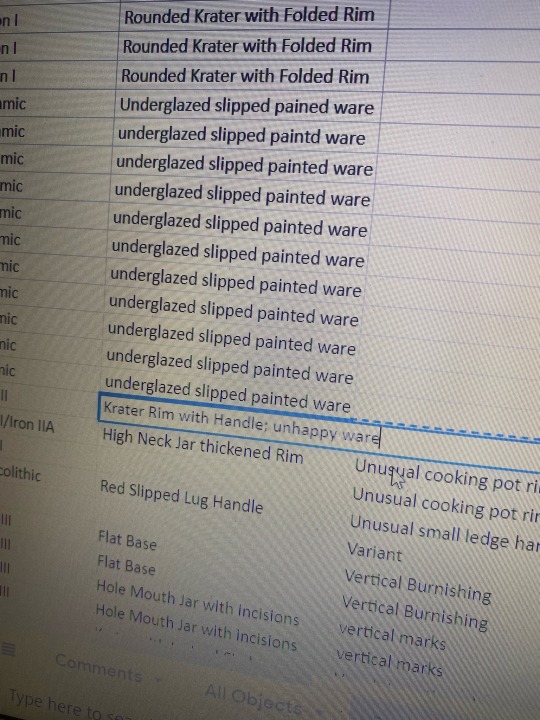

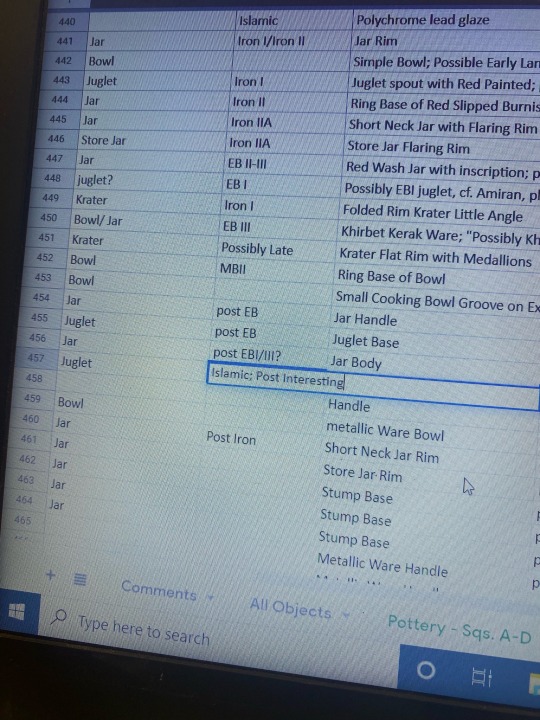

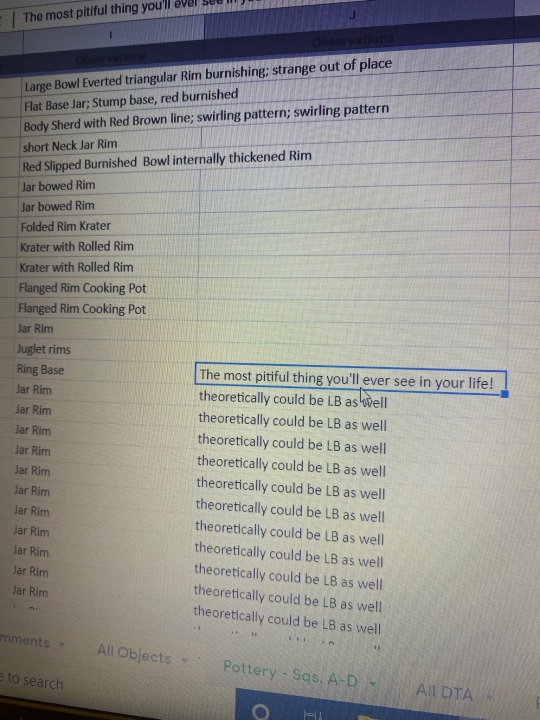

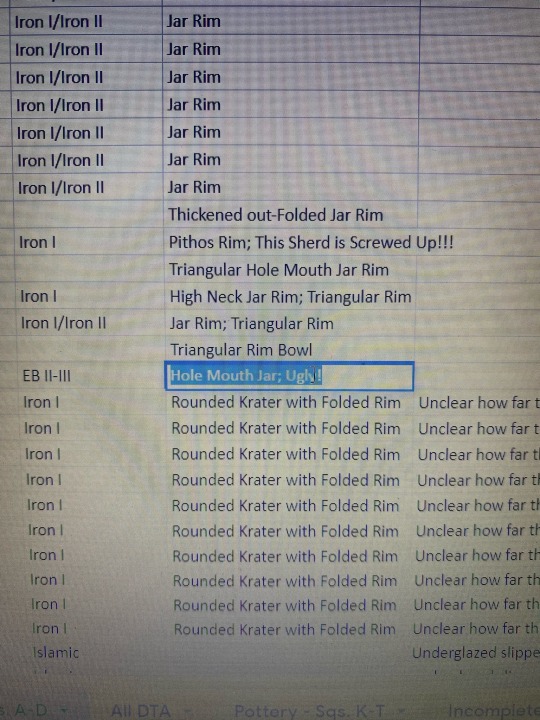

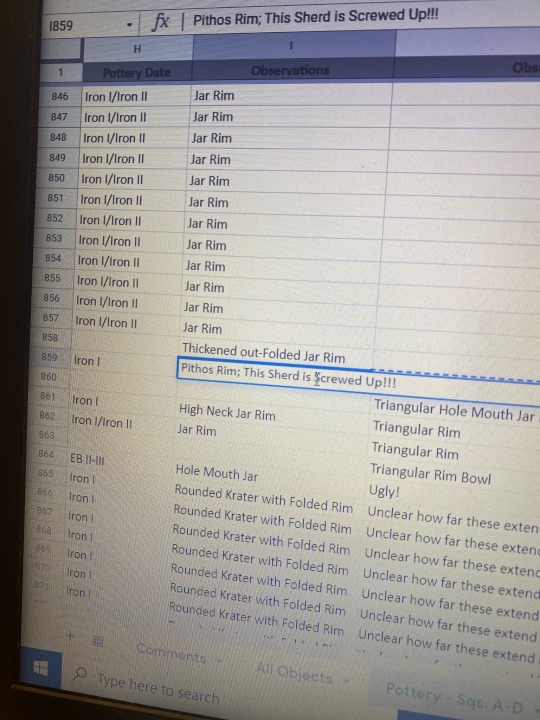

I work in an archaeology lab that has had many people come and go throughout the years.

Let’s just say some of the things this random person put on this pottery analysis spreadsheet made me scream bloody murder…

What is unhappy ware?? 😭😭

#unhappy ware#lost in the archives#archival work#pottery#analysis#spreadsheets#indexing#the life of a lab tech#archaeology#records#Phil knows his stuff#ugly!#also I hate when people date pottery as “post-interesting

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

If this truly does pinpoint the land of Punt, it is such important news for Egyptology.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

S2.8 is now on YouTube!

Have you ever thought about how dinosaurs lived on a warm, swampy Earth and how we live on one that’s cold enough to keep pretty much the entirety of Greenland and Antarctica buried under kilometers-thick sheets of solid ice and wondered, hmm, how did we get from there to here? The short answer is that it took 50 million years of declining atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and dropping temperatures, not to mention building an ice sheet or two.

For the longer story of the last 50 million years of climate change, including some of the reasons why, catch this episode of our podcast with Dr De La Rocha! You’ll hear about plate tectonics and continental drift, silicate weathering, carbonate sedimentation, and the spectacular effects the growth of Earth’s ice sheets have had on Earth’s climate. There are also lessons here for where anthropogenic global warming is going and whether or not its effects have permanently disrupted the climate system. Fun fact: the total amount of climate change between 50 million years ago and now dwarfs what we’re driving by burning fossil fuels, and yet, what we’re doing is more terrifying, in that it’s unfolding millions of times faster.

Bonus content: If you want to see sketches and plots of the data discussed in this episode, you can do so at our website here!!

Nerd alert!! If you're interested in the primary scientific literature on the subject, these four papers are a great place to start:

Dutkiewicz et al (2019) Sequestration and subduction of deep-sea carbonate in the global ocean since the Early Cretaceous. Geology 47:91-94.

Müller et al (2022) Evolution of Earth’s plate tectonic conveyor belt. Nature 605:629–639.

Rae et al (2021) Atmospheric CO2 over the last 66 million years from marine archives. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 49:609-641.

Westerfeld et al (2020) An astronomically dated record of Earth’s climate and its predictability over the last 66 million years. Science 369: 1383–1387.

#carbonate sedimentation#silicate weathering#solarpunk#solarpunk podcast#Solarpunk Presents Podcast#Dr Christina De La Rocha#plate tectonics#deep time#climactic system#climate change over millions of years#biogeochemical cycles#biogeochemistry#geological analysis of climate change#carbon dating#global warming#earth sciences#history of climate change#archaeology of climate change#continental drift#what was the climate like for the dinosaurs#youtube#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

RI2 - Lingual View

Patreon

#studyblr#notes#my notes#anthropology#biological anthropology#bioanthropology#bioanthro#bioanth#bio-anthropology#human biology#human osteology#biology#bio#osteology#osteological analysis#skeletal system#forensics#forensic anthropology#human bones#bones#forensic science#science#bone analysis#human identification#bioarchaeology#bioarcheology#archaeology#archeology#biological science#life science

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

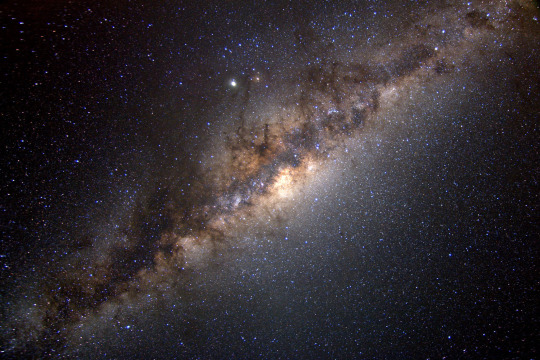

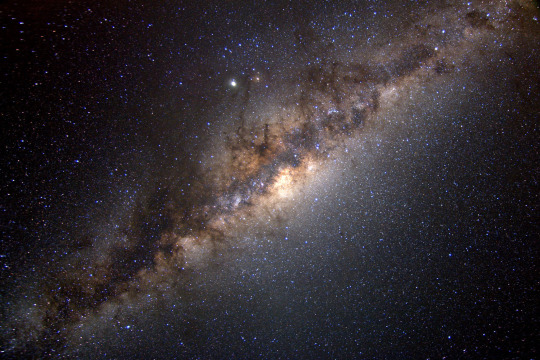

MIT researchers discover the universe’s oldest stars in our own galactic backyard

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/mit-researchers-discover-the-universes-oldest-stars-in-our-own-galactic-backyard/

MIT researchers discover the universe’s oldest stars in our own galactic backyard

MIT researchers, including several undergraduate students, have discovered three of the oldest stars in the universe, and they happen to live in our own galactic neighborhood.

The team spotted the stars in the Milky Way’s “halo” — the cloud of stars that envelopes the entire main galactic disk. Based on the team’s analysis, the three stars formed between 12 and 13 billion years ago, the time when the very first galaxies were taking shape.

The researchers have coined the stars “SASS,” for Small Accreted Stellar System stars, as they believe each star once belonged to its own small, primitive galaxy that was later absorbed by the larger but still growing Milky Way. Today, the three stars are all that are left of their respective galaxies. They circle the outskirts of the Milky Way, where the team suspects there may be more such ancient stellar survivors.

“These oldest stars should definitely be there, given what we know of galaxy formation,” says MIT professor of physics Anna Frebel. “They are part of our cosmic family tree. And we now have a new way to find them.”

As they uncover similar SASS stars, the researchers hope to use them as analogs of ultrafaint dwarf galaxies, which are thought to be some of the universe’s surviving first galaxies. Such galaxies are still intact today but are too distant and faint for astronomers to study in depth. As SASS stars may have once belonged to similarly primitive dwarf galaxies but are in the Milky Way and as such much closer, they could be an accessible key to understanding the evolution of ultrafaint dwarf galaxies.

“Now we can look for more analogs in the Milky Way, that are much brighter, and study their chemical evolution without having to chase these extremely faint stars,” Frebel says.

She and her colleagues have published their findings today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). The study’s co-authors are Mohammad Mardini, at Zarqa University, in Jordan; Hillary Andales ’23; and current MIT undergraduates Ananda Santos and Casey Fienberg.

Stellar frontier

The team’s discoveries grew out of a classroom concept. During the 2022 fall semester, Frebel launched a new course, 8.S30 (Observational Stellar Archaeology), in which students learned techniques for analyzing ancient stars and then applied those tools to stars that had never been studied before, to determine their origins.

“While most of our classes are taught from the ground up, this class immediately put us at the frontier of research in astrophysics,” Andales says.

The students worked from star data collected by Frebel over the years from the 6.5-meter Magellan-Clay telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory. She keeps hard copies of the data in a large binder in her office, which the students combed through to look for stars of interest.

In particular, they were searching ancient stars that formed soon after the Big Bang, which occurred 13.8 billion years ago. At this time, the universe was made mostly of hydrogen and helium and very low abundances of other chemical elements, such as strontium and barium. So, the students looked through Frebel’s binder for stars with spectra, or measurements of starlight, that indicated low abundances of strontium and barium.

Their search narrowed in on three stars that were originally observed by the Magellan telescope between 2013 and 2014. Astronomers never followed up on these particular stars to interpret their spectra and deduce their origins. They were, then, perfect candidates for the students in Frebel’s class.

The students learned how to characterize a star in order to prepare for the analysis of the spectra for each of the three stars. They were able to determine the chemical composition of each one with various stellar models. The intensity of a particular feature in the stellar spectrum, corresponding to a specific wavelength of light, corresponds to a particular abundance of a specific element.

After finalizing their analysis, the students were able to confidently conclude that the three stars did hold very low abundances of strontium, barium, and other elements such as iron, compared to their reference star — our own sun. In fact, one star contained less than 1/10,000 the amount of iron to helium compared to the sun today.

“It took a lot of hours staring at a computer, and a lot of debugging, frantically texting and emailing each other to figure this out,” Santos recalls. “It was a big learning curve, and a special experience.”

“On the run”

The stars’ low chemical abundance did hint that they originally formed 12 to 13 billion years ago. In fact, their low chemical signatures were similar to what astronomers had previously measured for some ancient, ultrafaint dwarf galaxies. Did the team’s stars originate in similar galaxies? And how did they come to be in the Milky Way?

On a hunch, the scientists checked out the stars’ orbital patterns and how they move across the sky. The three stars are in different locations throughout the Milky Way’s halo and are estimated to be about 30,000 light years from Earth. (For reference, the disk of the Milky Way spans 100,000 light years across.)

As they retraced each star’s motion about the galactic center using observations from the Gaia astrometric satellite, the team noticed a curious thing: Relative to most of the stars in the main disk, which move like cars on a racetrack, all three stars seemed to be going the wrong way. In astronomy, this is known as “retrograde motion” and is a tipoff that an object was once “accreted,” or drawn in from elsewhere.

“The only way you can have stars going the wrong way from the rest of the gang is if you threw them in the wrong way,” Frebel says.

The fact that these three stars were orbiting in completely different ways from the rest of the galactic disk and even the halo, combined with the fact that they held low chemical abundances, made a strong case that the stars were indeed ancient and once belonged to older, smaller dwarf galaxies that fell into the Milky Way at random angles and continued their stubborn trajectories billions of years later.

Frebel, curious as to whether retrograde motion was a feature of other ancient stars in the halo that astronomers previously analyzed, looked through the scientific literature and found 65 other stars, also with low strontium and barium abundances, that appeared to also be going against the galactic flow.

“Interestingly they’re all quite fast — hundreds of kilometers per second, going the wrong way,” Frebel says. “They’re on the run! We don’t know why that’s the case, but it was the piece to the puzzle that we needed, and that I didn’t quite anticipate when we started.”

The team is eager to search out other ancient SASS stars, and they now have a relatively simple recipe to do so: First, look for stars with low chemical abundances, and then track their orbital patterns for signs of retrograde motion. Of the more than 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, they anticipate that the method will turn up a small but significant number of the universe’s oldest stars.

Frebel plans to relaunch the class this fall, and looks back at that first course, and the three students who took their results through to publication, with admiration and gratitude.

“It’s been awesome to work with three women undergrads. That’s a first for me,” she says. “It’s really an example of the MIT way. We do. And whoever says, ‘I want to participate,’ they can do that, and good things happen.”

This research was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation.

#000#2022#Analysis#archaeology#Astronomy#Astrophysics#big bang#billion#Cars#chemical#chemical elements#chemistry#classes#Cloud#Composition#computer#course#data#Discoveries#dwarf#dwarf galaxies#earth#Evolution#Foundation#Gaia#galaxies#Galaxy#galaxy formation#helium#how

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🗿

#selfie#i got a new septum ring#i love it but it keeps twisting and this thing is fuckening wide so oof ouchy#i went to a cool talk on archaeological findings nd pollen analysis yesterday#pollen is insanely durable and can just last down in the depths of buried sediment of bogs#so cool how they KNOW this and USE it in conjunction with archaeology#Love it#yeah my eyes r red looking i was honeslty crying at QGIS crashing and losing all my FUCKING work

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

can i go back to my room with the rocks :( we never even finished putting them in boxes (ran out of the boxes)

#FORGOT THAT TO DO ANALYSIS OF ART. NEED RO KNOW LOCAL ART TROPES AND SYNBOLISM. IM FUCKED#gis archaeology…. just points on a map…… distribution analysis……… i want you…………………….#it’s not that i’m not interested in artifact analysis im just in way over my head and panicking that i’ll do it disrespectfully#or worse. accidentally plagiarizing

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

cave dirt post randomly got a bunch of notes yesterday so i feel i must update the masses: the dirt contains multitudes

#multitudes being an overwhelming amount of phytoliths#like. so many i don't even know where to begin w analysis#archaeology#lee becomes insufferable archaeologist arc

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I swear I'm not a bot

Posting something so the algo doesn't think I'm a fake person clicking on random stuff to train an AI.

Hi! I'm AJ and I write stuff, play video games, and work in tech. Anime and manga are my true loves beginning with Sailor Moon and going all the way through Monster, Fullmetal Alchemist (which is having A Moment right now), and even some the Netflix pandering stuff like Castlevania.

I wrote a fantasy novel about a girl cursed to live as a boy - not just ANY boy but the heir to the throne: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/152020268-witch-king-s-oath

I make TikToks for it because I'm learning hacks to help VR game developers market their Quest games.

Tumblr is VERY LIKELY to be my manhwa era. This is the only platform not run by a right wing nut job where I can find other Shutline, Saezuru Tori wa Habatakanai, and weird fan theories about Our Flag Means Death all in one place.

Glad to be here <3

#셔트라인#shutline#anime#manga#history#my writing#archaeology#fantasybooklover#fantasybooktok#fantasy books#vr games#oculus#saezuru tori wa habatakanai#saezuru spoilers#saezuru fandom#saezuru feels#saezuru analysis

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Should I write a NAGPRA compliance analysis of Supernatural season 1 episode 8 "Bugs"

3 notes

·

View notes