#Intel 8080

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Intel 8080, 50 Years and counting - Francis Bauer

VCF West XVIII

#vcfwxviii#vcf west xviii#vintage computer festival west xviii#commodorez goes to vcfwxviii#sol-20#intel 8080

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROM January 1978

Microprocessors from Motorola and Intel ride in harmony (although the Intel 8080 was more associated with the "S-100 bus" than the Motorola 6800, and anyway both of them were beginning to be displaced in the attention of many by the Zilog Z80 and MOS 6502) on the cover of this issue. Ted Nelson's column looked at "the computer screen," mentioning the certain capabilities of the Commodore PET, Radio Shack TRS-80, S-100 boards, and Compucolor, but not the Apple II. An article offering "A look at what's coming" in home computers described the PET, TRS-80, and Ohio Scientific Challenger, but not the Apple II. However, those who make a big point of the Apple II starting out very small might yet have to consider an article about computer graphics that did mention "the Apple machine," even if the author hadn't "had a chance to look at it that carefully."

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Casi se cumplen 50 años de la aparición de la Processor Technology SOL-20, hablemos de esta máquina.

Hoy hago una pausa en las efemérides, para hablar de la Processor Technology SOL-20, una máquina que cumple casi 50 años desde su aparición, y que fue eclipsada por la Trinidad 77 (Apple, Commodore y Radio Shack) y fue un verdadero parteaguas en la evolución de las computadoras personales. #retrocomputingmx #SOL20 #efemeridestecnologica

0 notes

Text

2025 has strong product number vibes. you get that right? like the intel 8080 and raspberry 2350?

#even stronger than 2040 imho#and everyone who doesnt understand is gettin gblocked#dont disrespect my number vibes#i will die for 1024

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

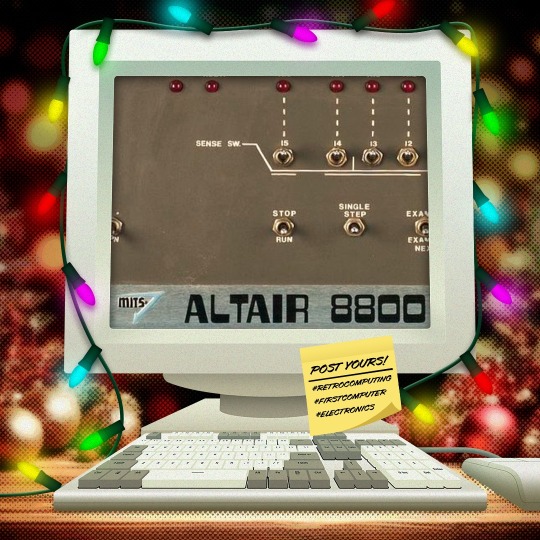

🎄💾🗓️ Day 7: Retrocomputing Advent Calendar - Altair 8800🎄💾🗓️

The Altair 8800 was one of the first commercially successful personal computers, introduced in 1975 by MITS, and also one of the most memorable devices in computing history. Powered by the Intel 8080 CPU, an 8-bit processor running at 2 MHz, and initially came with 256 bytes of RAM, expandable via its S-100 bus architecture. Users would mainly interact with the Altair through its front panel-mounted toggle switches for input and LEDs for output.

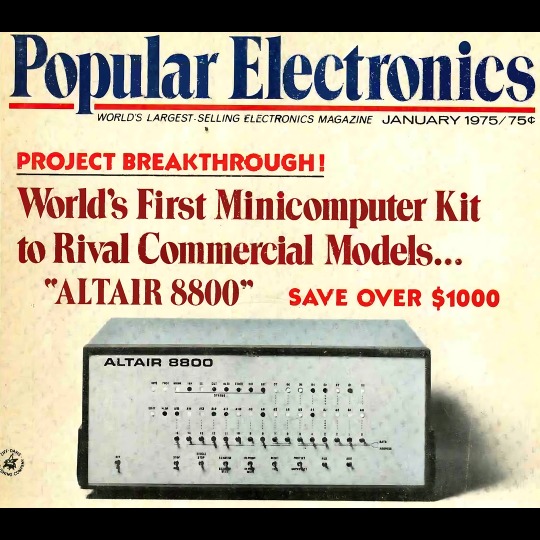

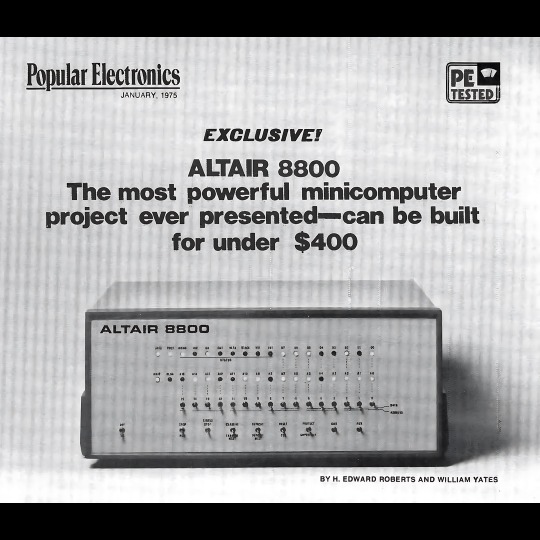

The Altair 8800 was popularized through a Popular Electronics magazine article, as a kit for hobbyists to build.

It was inexpensive and could be expanded, creating a following of enthusiasts that launched the personal computer market. Specifically, it motivated software development, such as Microsoft's first product, Altair BASIC.

The Altair moved from hobbyist kits to consumer-ready personal computers because of its modular design, reliance on the S-100 bus that eventually became an industry standard, and the rise of user groups like the Homebrew Computer Club.

Many of ya'll out there mentioned the Altair 8800, be sure to share your stories! And check out more history of the Altair on its Wikipedia page -

along with the National Museum of American History - Behring center -

Have first computer memories? Post’em up in the comments, or post yours on socialz’ and tag them #firstcomputer #retrocomputing – See you back here tomorrow!

#retrocomputing#altair8800#firstcomputer#electronics#vintagecomputing#computinghistory#8080processor#s100bus#microsoftbasic#homebrewcomputerclub#1975tech#personalcomputers#computerkits#ledswitches#technostalgia#oldschooltech#intel8080#computerscience#techenthusiasts#diycomputing#earlycomputers#computermemory#vintageelectronics#hobbycomputing#popularelectronics#techhistory#innovation#computermilestones#geekculture

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some of the coolest computer chips ever, in your opinion?

Hmm. There are a lot of chips, and a lot of different things you could call a Computer Chip. Here's a few that come to mind as "interesting" or "important", or, if I can figure out what that means, "cool".

If your favourite chip is not on here honestly it probably deserves to be and I either forgot or I classified it more under "general IC's" instead of "computer chips" (e.g. 555, LM, 4000, 7000 series chips, those last three each capable of filling a book on their own). The 6502 is not here because I do not know much about the 6502, I was neither an Apple nor a BBC Micro type of kid. I am also not 70 years old so as much as I love the DEC Alphas, I have never so much as breathed on one.

Disclaimer for writing this mostly out of my head and/or ass at one in the morning, do not use any of this as a source in an argument without checking.

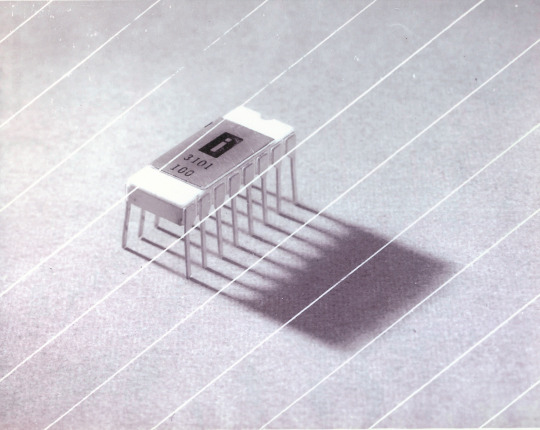

Intel 3101

So I mean, obvious shout, the Intel 3101, a 64-bit chip from 1969, and Intel's first ever product. You may look at that, and go, "wow, 64-bit computing in 1969? That's really early" and I will laugh heartily and say no, that's not 64-bit computing, that is 64 bits of SRAM memory.

This one is cool because it's cute. Look at that. This thing was completely hand-designed by engineers drawing the shapes of transistor gates on sheets of overhead transparency and exposing pieces of crudely spun silicon to light in a """"cleanroom"""" that would cause most modern fab equipment to swoon like a delicate Victorian lady. Semiconductor manufacturing was maturing at this point but a fab still had more in common with a darkroom for film development than with the mega expensive building sized machines we use today.

As that link above notes, these things were really rough and tumble, and designs were being updated on the scale of weeks as Intel learned, well, how to make chips at an industrial scale. They weren't the first company to do this, in the 60's you could run a chip fab out of a sufficiently well sealed garage, but they were busy building the background that would lead to the next sixty years.

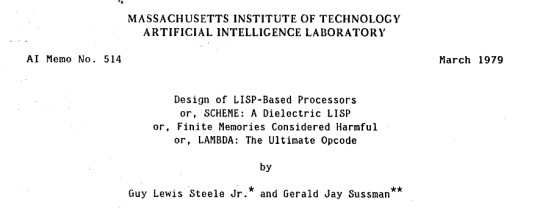

Lisp Chips

This is a family of utterly bullshit prototype processors that failed to be born in the whirlwind days of AI research in the 70's and 80's.

Lisps, a very old but exceedingly clever family of functional programming languages, were the language of choice for AI research at the time. Lisp compilers and interpreters had all sorts of tricks for compiling Lisp down to instructions, and also the hardware was frequently being built by the AI researchers themselves with explicit aims to run Lisp better.

The illogical conclusion of this was attempts to implement Lisp right in silicon, no translation layer.

Yeah, that is Sussman himself on this paper.

These never left labs, there have since been dozens of abortive attempts to make Lisp Chips happen because the idea is so extremely attractive to a certain kind of programmer, the most recent big one being a pile of weird designd aimed to run OpenGenera. I bet you there are no less than four members of r/lisp who have bought an Icestick FPGA in the past year with the explicit goal of writing their own Lisp Chip. It will fail, because this is a terrible idea, but damn if it isn't cool.

There were many more chips that bridged this gap, stuff designed by or for Symbolics (like the Ivory series of chips or the 3600) to go into their Lisp machines that exploited the up and coming fields of microcode optimization to improve Lisp performance, but sadly there are no known working true Lisp Chips in the wild.

Zilog Z80

Perhaps the most important chip that ever just kinda hung out. The Z80 was almost, almost the basis of The Future. The Z80 is bizzare. It is a software compatible clone of the Intel 8080, which is to say that it has the same instructions implemented in a completely different way.

This is, a strange choice, but it was the right one somehow because through the 80's and 90's practically every single piece of technology made in Japan contained at least one, maybe two Z80's even if there was no readily apparent reason why it should have one (or two). I will defer to Cathode Ray Dude here: What follows is a joke, but only barely

The Z80 is the basis of the MSX, the IBM PC of Japan, which was produced through a system of hardware and software licensing to third party manufacturers by Microsoft of Japan which was exactly as confusing as it sounds. The result is that the Z80, originally intended for embedded applications, ended up forming the basis of an entire alternate branch of the PC family tree.

It is important to note that the Z80 is boring. It is a normal-ass chip but it just so happens that it ended up being the focal point of like a dozen different industries all looking for a cheap, easy to program chip they could shove into Appliances.

Effectively everything that happened to the Intel 8080 happened to the Z80 and then some. Black market clones, reverse engineered Soviet compatibles, licensed second party manufacturers, hundreds of semi-compatible bastard half-sisters made by anyone with a fab, used in everything from toys to industrial machinery, still persisting to this day as an embedded processor that is probably powering something near you quietly and without much fuss. If you have one of those old TI-86 calculators, that's a Z80. Oh also a horrible hybrid Z80/8080 from Sharp powered the original Game Boy.

I was going to try and find a picture of a Z80 by just searching for it and look at this mess! There's so many of these things.

I mean the C/PM computers. The ZX Spectrum, I almost forgot that one! I can keep making this list go! So many bits of the Tech Explosion of the 80's and 90's are powered by the Z80. I was not joking when I said that you sometimes found more than one Z80 in a single computer because you might use one Z80 to run the computer and another Z80 to run a specialty peripheral like a video toaster or music synthesizer. Everyone imaginable has had their hand on the Z80 ball at some point in time or another. Z80 based devices probably launched several dozen hardware companies that persist to this day and I have no idea which ones because there were so goddamn many.

The Z80 eventually got super efficient due to process shrinks so it turns up in weird laptops and handhelds! Zilog and the Z80 persist to this day like some kind of crocodile beast, you can go to RS components and buy a brand new piece of Z80 silicon clocked at 20MHz. There's probably a couple in a car somewhere near you.

Pentium (P6 microarchitecture)

Yeah I am going to bring up the Hackers chip. The Pentium P6 series is currently remembered for being the chip that Acidburn geeks out over in Hackers (1995) instead of making out with her boyfriend, but it is actually noteworthy IMO for being one of the first mainstream chips to start pulling serious tricks on the system running it.

The P6 microarchitecture comes out swinging with like four or five tricks to get around the numerous problems with x86 and deploys them all at once. It has superscalar pipelining, it has a RISC microcode, it has branch prediction, it has a bunch of zany mathematical optimizations, none of these are new per se but this is the first time you're really seeing them all at once on a chip that was going into PC's.

Without these improvements it's possible Intel would have been beaten out by one of its competitors, maybe Power or SPARC or whatever you call the thing that runs on the Motorola 68k. Hell even MIPS could have beaten the ageing cancerous mistake that was x86. But by discovering the power of lying to the computer, Intel managed to speed up x86 by implementing it in a sensible instruction set in the background, allowing them to do all the same clever pipelining and optimization that was happening with RISC without having to give up their stranglehold on the desktop market. Without the P5 we live in a very, very different world from a computer hardware perspective.

From this falls many of the bizzare microcode execution bugs that plague modern computers, because when you're doing your optimization on the fly in chip with a second, smaller unix hidden inside your processor eventually you're not going to be cryptographically secure.

RISC is very clearly better for, most things. You can find papers stating this as far back as the 70's, when they start doing pipelining for the first time and are like "you know pipelining is a lot easier if you have a few small instructions instead of ten thousand massive ones.

x86 only persists to this day because Intel cemented their lead and they happened to use x86. True RISC cuts out the middleman of hyperoptimizing microcode on the chip, but if you can't do that because you've girlbossed too close to the sun as Intel had in the late 80's you have to do something.

The Future

This gets us to like the year 2000. I have more chips I find interesting or cool, although from here it's mostly microcontrollers in part because from here it gets pretty monotonous because Intel basically wins for a while. I might pick that up later. Also if this post gets any longer it'll be annoying to scroll past. Here is a sample from a post I have in my drafts since May:

I have some notes on the weirdo PowerPC stuff that shows up here it's mostly interesting because of where it goes, not what it is. A lot of it ends up in games consoles. Some of it goes into mainframes. There is some of it in space. Really got around, PowerPC did.

237 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat?

you got: intel 8080 (common)

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

So this is maybe a little older than your preferred tech age, but I kind of associate you with older computers because objectum. My dad told me once that his first computer was an Intel 8080 (my mother insists it was an Intel 8088) and I was wondering if you happened to know where I could find images of old tech (or specifically that computer)? I just want to know what my dad loved so much

He was apparently very proud of that computer. Mom said that his serial number was something like #30

i'm a little confused because i'm pretty sure that the intel 8080 (and 8088) is a microprocessor and not a computer? however i can indeed supply you with resources for looking for old computers.

blogs on tumblr (which post images of neat old tech): @/vizreef, @/dinosaurspen, @/odd-drive, @/legacydevice, @/mingos-commodoreblog, @/olivrea1908, @/yodaprod, @/chunkycomputers, @/desktopfriend, @/koneyscanlines,

websites: old computer museum (via the wayback machine), dave's old computers, steve's computer collection, and MCbx old computer collection

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Federico Faggin: Bridging Microprocessor Innovation and Quantum Consciousness

Federico Faggin, an Italian-American physicist, engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur, demonstrated an early interest in technology, which led him to earn a degree in physics. Faggin began his career at SGS-Fairchild in Italy, where he developed the first MOS metal-gate process technology. In 1968, he moved to the United States to work at Fairchild Semiconductor, where he created the MOS silicon gate technology. In 1970, Faggin joined Intel, where he led the development of the Intel 4004. He also contributed to the development of the Intel 8008 and 8080 microprocessors. In 1974, he co-founded Zilog, where he developed the Z80 microprocessor. Faggin later became involved in other ventures, including Synaptics, where he worked on touchpad technology. Faggin's deepening interest in consciousness began during his work with artificial neural networks at Synaptics. This interest led him to explore whether it is possible to create a conscious computer, ultimately steering him towards philosophical inquiries about the nature of consciousness and reality. In 2011, Faggin founded the Federico and Elvia Faggin Foundation to support research into consciousness. Faggin has developed a theory of consciousness that proposes that consciousness is a quantum phenomenon, distinct and unique to each individual. His theory is influenced by two quantum physics theorems: the no-cloning theorem, which states that a pure quantum state cannot be duplicated, and Holevo's theorem, which limits the measurable information from a quantum state to one classical bit per qubit. According to Faggin, consciousness is akin to a pure quantum state—private and only minimally knowable from the outside. Faggin's perspective suggests that consciousness is not tied to the physical body, allowing for the possibility of its existence beyond physical death. He views the body as being controlled by consciousness in a "top-down" manner. This theory aligns with an idealist model of reality, where consciousness is seen as the fundamental level, and the classical physical world is merely a set of symbols representing a deeper reality. His transition reflects a broader quest to reconcile technological advancements with the philosophical and spiritual dimensions of human existence.

Frederico Faggin: We are Conscious Quantum Fields, Beyond Space and Time (Dr. Bernard Beitman, Connecting with Coincidence, September 2024)

youtube

Monday, September 16, 2024

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come hanno fatto gli ingegneri a programmare il software o un sistema operativo prima che esistesse una tastiera?

Non avevano la tastiera ma avevano accesso diretto alla memoria, che è pure meglio. Programmavano in linguaggio macchina inserendo un byte dopo l'altro, tramite interruttori e pulsanti. La stessa soluzione dell'Altair 8800, il nonno dei microcomputer anni '80.

Quindi, a rigor di termini, non è corretto dire che non avessero tastiere: erano solo un po' diverse dalle nostre.

Le prime tastiere dei mainframe furono delle telescriventi, che si interfacciavano ai computer attraverso nastri perforati, e poi terminali video, come la famosa famiglia VT100 della Digital. Per avere delle "tastiere" nel senso che diciamo noi devi aspettare (ancora) i primi microcomputer su scheda, come l'amico 2000 che avevano una tastiera esadecimale a bordo.

Il "sistema operativo" dell'Amico 2000 era un semplice monitor in linguaggio macchina, cioè un programma che ti dava modo di scrivere i tuoi programmi in linguaggio macchina, eseguirli e farli terminare cristianamente. Qualcosa di simile al DEBUG di MS-DOS, ma più primitivo.

L'evoluzione successiva la conosciamo tutti,

l'Intel 8086 è un microprocessore a 16 bit progettato dalla Intel nel 1978, che diede origine all'architettura x86. È basato sull'8080 e sull'8085 (è compatibile con l'assembly dell'8080), con un insieme di registri simili, ma a 16 bit.

Buon lavoro a tutti!

0 notes

Text

The Journey of Pixel Games: From Simple Dots to Timeless Art

New Post has been published on https://www.luxcrato.com/technology/the-journey-of-pixel-games/

The Journey of Pixel Games: From Simple Dots to Timeless Art

Table of Contents

Toggle

Introduction: The Birth of Pixelated Dreams

The Dawn of Pixels: 1970s and Early Arcade Era

The Golden Age: 1980s and the Rise of Home Consoles

The 16-Bit Revolution: 1990s and Pixel Art Mastery

The Decline and Nostalgia: Late 1990s to Early 2000s

The Indie Resurgence: 2010s and Pixel Art Renaissance

Modern Pixels: 2020s and Beyond

Why Pixels Endure

Introduction: The Birth of Pixelated Dreams

Imagine a flickering screen in a hushed room, alive with glowing squares—jumpy, rough-edged, and brimming with potential. That’s where video games took root, cradled by pixels. Those tiny specks of light weren’t just a tech quirk; they sparked a revolution. From the 1970s’ basic blips to the indie brilliance lighting up 2025, pixel games have twirled through decades, evolving from a necessity into an enduring art form. Why do they stick around? Pixels carry nostalgia, creativity, and a quiet defiance of modern tech’s gloss. This is their story—a blend of history, personal memory, and a salute to their unstoppable march forward. Let’s dive in.

The Dawn of Pixels: 1970s and Early Arcade Era

The 1970s were gaming’s wild west, where pixels blazed trails in a digital void. Pong (1972) started it all—two white paddles and a square ball bouncing across a black screen. Atari’s creation was barebones, but it captivated anyone who watched. With hardware so frail it could barely hum, developers leaned on pixels, each dot a precious spark in a sea of limits. Then Space Invaders (1978) stormed arcades, its blocky alien fleet creeping down screens worldwide. Tomohiro Nishikado wrestled an Intel 8080 chip to birth those invaders in crisp 2-bit glory—black and white, no grays allowed. It wasn’t much, but it worked. Kids didn’t see pixels; they saw galactic battles. This was the dawn of pixel games, where every square hinted at bigger things ahead.

The Golden Age: 1980s and the Rise of Home Consoles

The 1980s turned pixels into playgrounds, and what a ride it was. Pac-Man (1980) chomped in—a yellow circle gobbling dots in a neon maze, its 8-bit ghosts dripping with charm. Namco made pixels sing, proving they could hold personality. But the real shift came with home consoles, pulling arcade thrills into living rooms. Take the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES)—a small gray box that rewrote the game. Super Mario Bros. (1985) burst forth, its plumber hero leaping across the Mushroom Kingdom’s pixel plains. Shigeru Miyamoto spun 8-bit tiles into gold—green pipes, golden coins, and spiky foes, all glowing within a 256-color cap. For some, it hit close to home. Picture a kid in the late ‘80s—call him a dreamer—plugging in his NES, eyes wide with joy. “This is amazing,” he thought, gripping the controller like a magic wand. No online play, no networks—just pure, unfiltered fun. Hours vanished chasing Bowser, and those blocky graphics felt top-notch. “Who’d ever need more?” he wondered, oblivious to the online worlds yet to come.

The Legend of Zelda (1986) sealed the deal, weaving epic tales with tiny sprites. Sega’s Master System spiced up the rivalry, but for many, the NES reigned supreme—a pixelated crown in a golden age where every dot pulsed with life.

The 16-Bit Revolution: 1990s and Pixel Art Mastery

The 1990s cranked things up—pixels got sharper, bolder, and downright gorgeous. The leap to 16-bit, powered by the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo (SNES), was a game-changer. Sonic the Hedgehog (1991) dashed in, his blue spikes a blur of smooth motion. Sega’s palette—bursting with thousands of colors—made backgrounds hum and sprites strut. That dreamer from the ‘80s? He saw the Genesis and gasped. “Nintendo’s ancient now,” he declared, watching Sonic’s speedy antics. The NES, once a wonder, looked like a dusty fossil next to Sega’s 16-bit shine. Super Mario World (1990) fought back for Nintendo, with Yoshi prancing through prehistoric pixelscapes, but Sega’s flair had stolen the show.

Games like Final Fantasy VI (1994) and Chrono Trigger (1995) pushed further—Kefka’s mad grin and Crono’s windswept hair proving pixels could tug at the soul. This was pixel art’s peak, a shining moment before 3D crashed in.

The Decline and Nostalgia: Late 1990s to Early 2000s

Then came the polygon wave. The late ‘90s swapped sprites for 3D models, with the PlayStation and Nintendo 64 leading the charge. Super Mario 64 (1996) turned Mario into a bouncy polygon puppet, while The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) draped Hyrule in 3D splendor. Pixels? They seemed old-fashioned, a sweet memory as developers chased lifelike textures. But that dreamer—now a teen—saw something wilder. Enter the PC era and the 3dfx Voodoo graphics card, a beast that yanked games into a new realm. “This isn’t gaming,” he thought, stunned, “it’s like living a movie.” Titles like Quake and Tomb Raider gleamed with 3D realism, polygons so crisp they felt alive. Pixels slipped to the sidelines, but nostalgia brewed. By the early 2000s, emulators revived NES classics, and retro collections sold fast. The decline wasn’t an end—it was a pause, with pixels dreaming of their return.

The Indie Resurgence: 2010s and Pixel Art Renaissance

That return hit hard in the 2010s, when indie developers grabbed the pixel torch and ran wild. Minecraft (2011) exploded—not 2D, but a blocky 3D love letter to low-res vibes. Markus Persson’s creation proved pixels (or cubes) could still rule, raking in billions and sparking a creative surge. Fez (2012) twisted pixel art into mind-bending brilliance, its retro shell hiding genius.The renaissance peaked with Stardew Valley (2016), a 16-bit farming dream dripping with soul. Eric Barone poured years into every swaying crop and shy villager, crafting intimacy AAA titles often missed. Celeste (2018) followed, its pixel peaks mirroring real struggles—simple visuals, seismic depth. Why the comeback? Pixels hit the heart—nostalgia, sure, but also raw honesty. Big-budget games chased photorealism, but indies wielded pixels like poets, proving less could be more.

Modern Pixels: 2020s and Beyond

Now, in 2025, pixels are a stunning paradox—retro roots with modern punch. Hollow Knight (2017) lingers as a gothic gem, its sprites weaving haunting tales. Dead Cells (2018) blends pixel gore with fluid combat, evolving yearly like a living thing. Tech’s soared—dynamic lighting, particle effects—but the pixel spirit beats strong.The dreamer, now grown, marvels at the leap from 3dfx Voodoo to today’s graphics cards. “Back then, 3D felt real,” he recalls, “but now VR drops you inside the screen.” Games like Tetris Effect: Connected (2020) fuse pixels with virtual reality, turning falling blocks into a cosmic dance.

Indies push wilder—ray-traced pixel art, AI-spun retro worlds. Imagine VR goggles plunging you into a blocky Mario kingdom or algorithms crafting pixel epics on the fly. Pixels aren’t relics; they’re shape-shifters, blending past and future with ease.

Why Pixels Endure

From Pong’s lone dot to Celeste’s jagged cliffs, pixel games have traced a winding, joyful path. They grew from tech’s frail roots, bloomed into art, faded under 3D’s shadow, then roared back with indie fire. For that dreamer of the ‘80s, they were a gateway—Nintendo’s 8-bit wonders, Sega’s 16-bit flair, Voodoo’s 3D leap, and now VR’s bold frontier. Pixels endure because they’re true—every square a story, every limit a spark. In 2025, they bridge yesterday’s joys with tomorrow’s dreams, proving beauty needs no polygons—just heart.So, dust off an NES cartridge, fire up an emulator, or grab an indie pixel gem. The journey of pixel games isn’t over—it’s a tale still unfolding, and you’re part of it.

0 notes

Text

People's Computer Company September 1975

This issue included more design notes for Tiny BASIC and a look at the official Altair BASIC from MITS (programmed by Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Monte Davidoff). It acknowledged the appearance of BYTE, but was a bit suspicious of Wayne Green's magazine relying on money from advertisers ("a strong incentive not to knock an advertiser's product.") There were also looks at a film about the construction of a geodesic dome and an "Energy Primer."

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long post! Beware!

Well, let me tell you the story the most important piece of software that nobody really knows about. The Basic Input Output System is a piece of software that comes bundled with the hardware. The first ones were burned [1] into Read Only Memory chips. At boot, the CPU has a specific memory address that it just starts running. The BIOS is that program that it runs.

Basically, as the name suggests, it’s a fairly simple program and it sets up the bridge between the OS and the hardware. Meaning that it sets up the equivalent of a mailbox for all the things to communicate with each other.

This means that you can write a single Operating System and so long as it can speak BIOS, it can run on the dozens of Intel 8080 computers on the market in the early 80s.

Which brings us to the author: Gary Kildall. Gary wrote BIOS for his product CP/M (Control Program for Microcomputers - a term that made sense at the time). CP/M was an OS for the growing home computer market. Computers like the Commodore 64, Apple II, even the first home computer the Altair 88 all booted into BASIC which was a simple programming language. But all these versions were different. If you booted into a program that only dealt with managing files (these didn’t even have directories aka folders ) and launching programs, it would be a lot easier.[2]

For this reason, IBM wanted to buy CP/M. They approached Microsoft as the broker for the deal and for … reasons [3] … they ended up hiring MS to write a clone of it instead. This became PC DOS [4] and the reason Bill Gates was the richest man in the world for a long time.

The BIOS was the thing that stood between the hardware and the software. So if anyone wanted to run DOS on a generic PC clone, they would need a BIOS for that clone. But software is copyrighted, so the few companies that just copied the available code from IBM got sued into oblivion. Until a plucky company called Compaq came up with the “clean room” method. 1 team would read the code and write what it does and a second team would write fresh code based on those specs. This was upheld in court when Big Blue tried to take them down.

At the time IBM and Apple controlled their hardware ecosystem and set the price of access to computing. But freeing the BIOS turned the technology inferior intel based PC into an open platform, which lead to cheaper competitors and the reason that the PC is so dominant.

Modern computers have replaced the BIOS with the Extended Firmware Interface (EFI). People still call it BIOS because few understand what it ever did, but BIOS is dead. Long live BIOS

Footnotes:

[1] Programmable ROM chips are a grid diodes, which let current run in one direction. If you apply enough heat, it will literally burn out the diode so current can’t run in any direction. Apply test voltage on an unburned bit you get that voltage back, a 1. Otherwise the current is blocked and you get a 0. Flash Memory is a distant ancestor of this technology.

[2] remember that this was all done before the home computers could display graphics without dipping into the machine language (Assembly Language- which is different for every type of processor). Thus you typed lines of commands as your interface, a Command Line Interface.

[3] obviously the reasons vary depending on the storyteller, for some Kildall was hardheaded and wanted to retain ownership, for others, there was a miscommunication.

[4] the deal allowed MS to sell their own version of it, MS DOS. This will come up in a sec.

this can't be true can it

99K notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

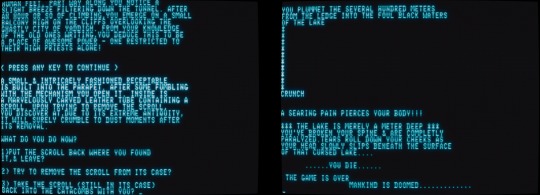

PC Horror Games in 1979

youtube

By the 1970’s, the horror game genre spanned across all major platforms, from 2 generations of home consoles to arcades to desktop and mainframe computers. Commercial general-purpose digital computers that can store programs and games for them had been around since at least the early 1950’s. The 60’s advertised compact and affordable minicomputers, and, in the 1970’s, surged in popularity in what is referred to as “the microcomputer revolution” after a 1968 breakthrough resulted in things becoming even tinier and soon more affordable. Alongside them, commercial video games (which had arguably also been on the market since, at least, the 1950’s) had finally become mainstream, which is a phrase that almost gives me PTSD with how annoying people used to be about it, but by the 1970's, video games were mainstream entertainment, so large that within just 3 more years, they would be considered bigger than Hollywood and pop music COMBINED! You can imagine, by the 70’s, home computers were already made with developers in mind. For the average Joe simply wanting to play horror games in the 1970’s, consoles being streamlined home and portable personal computers made for that purpose would be the way to go, which is probably why so many did, and that history is often celebrated, but I’m curious about the landscape of the desktop PCs. I’d like to take a look at this microcomputer revolution from the perspective of its horror games.

Microsoft

This “revolution” is often attributed as starting in the early 1970's, where Lakeside high school students Paul Allen and Bill Gates commonly sought access to computers, even being banned from seemingly more than one place like Computer Center Corporation, where they exploited a bug to get additional free computer time. They would form the Lakeside Programmers Club to make money working with computers, including for the center that banned them! After high school, they’d go to different colleges, and Paul Allen would drop out to become a programmer for Honeywell. A week before Christmas of 1974, a new issue of Popular Electronics would drop, showcasing a new player in the microcomputer game, the Altair 8800, using the new Intel 8080, whose predecessor, Paul and Bill, worked with in their younger years. Inspired to start his own software company, he would contact the computer maker about software and convince Bill Gates to drop out of Harvard and join him in making an interpreter for BASIC programming language to run on it, forming Microsoft. Paul flew out to deliver what they made and showcased it by playing some version of the 1969 game Lunar Lander.

Kadath- 1979 July 15 – Altair 8800

The 8800 would become a popular PC to the point of being credited as the start of desktops leap in popularity during the 1970s, which is what people refer to as the “revolution” as opposed to the 1968 breakthrough itself, and, on July 15th of 1979, a horror game would be written for it. A fan fiction set in the world of the works of famous Rhode Island author, Howard Philips Lovecraft. Kadath tells the story of said world Yaddith being in danger of the return of a precursor civilization, whom a stone tablet you find on an archaeological dig prophesies will return when the stars align correctly. You have set out to find the eye of Kadath, a gem thought to be powerful enough to destroy the gateway from which they would enter, which you plan to do by cracking open the eye to unleash its power. Kadath framed its writing seriously and had content I found more visceral than previous games of its genre. Despite infamous typos, I found it well written, though it’s not my taste in horror. Gameplay, however, I found to be an improvement through its use of multiple-choice actions instead of making the player figure out what to type. Depending on how you feel about text adventures, you might find this to be a downgrade, or if you find figuring out what to type in a text adventure a horror in itself, you might see it as a relief. This game would also not remain exclusive to the 8800 and be brought to future home desktops.

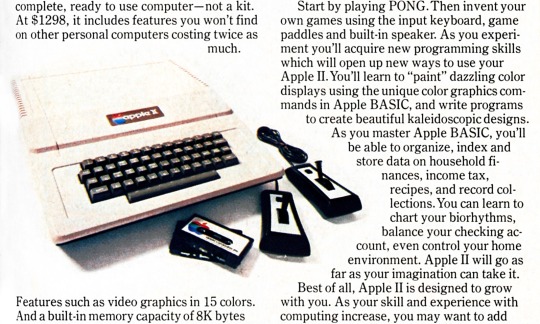

Apple

When a now famous hacker by the name of Steve Wozniak was working at Hewlett-Packard, his friend told him he should meet a high school student by the name of Steve Jobs who likes electronics and playing pranks. At the time, Wozniak was inspired by an article in Esquire magazine about blue boxes that emulated the sounds phones make to connect people, therefore allowing you to hack free calls. He wanted to make his own, and Jobs wanted to sell it. Selling them for $150 each, splitting the profits—this would be the dynamic people remember of “the 2 Steves”: Woz knows how to make the tech and Jobs knows how to sell it. What I always remember though is how Jobs believed his vegetarian diet ensured he wouldn’t produce body odor and thus he wouldn’t have to shower, which his coworkers at Atari didn’t seem to agree with, causing them to quickly put him on the night shift, which didn’t exist, meaning he’d come into the building when everyone was gone and be able to bring Wozniak in to get things done. His boss, Nolan Bushnel, was aware but didn’t really care because, as he put it, he got “two Steves for the price of one" He did offer Wozniak at least one bonus, but through Jobs, who hid it from him. Woz would eventually make a computer for his homebrew computer club, and after his workplace was uninterested in buying it from him, Jobs would convince him they should start their own company and sell it themselves. After this 1976 referred to as the Apple 1 would find good success, the Apple II the following year would become sought after by aspiring video game developers as a desktop made for making video games. It shipped with an interpreter made with hobbyists and game devs in mind that allowed users to immediately write software without additional stuff needed.

Akalabeth: World of Doom – 1979-1980 – eventually Apple II

Now dawn your thinking beard for this one. A question I’ve pondered is the Venn diagram of considering something in the stereotypical old European fantasy setting and something being considered a horror game because there are a lot of games like 1979’s Dungeon of Death which are considered to be horror games that I never would have thought of as horror games. I’m curious what percentage of people consider which of these to be horror games from that first-person dungeon crawler Puyo spawned off from to Baldur’s Gate or Untold Legends. There’s no wrong answer to me. I just notice it’s a far higher percentage than I thought. I bring all this up because one of the people to make games for the Apple II was soon to be famed Ultima creator Richard Garriott, just 2 years before Ultima. It apparently started as a high school project he made on a school computer, which was one of 28 fantasy games he made in high school before getting his hands on an Apple II and making the more fleshed-out version, Akalabeth: World of Doom, and I can see how its cover sets a tone that carries over into the first-person dungeon crawler featuring hooded figures and the general tension of running into danger while exploring, especially in a first-person game. Picture Zelda 2, where there’s a top-down overworld and sidescrolling dungeons. This is like that where there’s a top-down world to explore with towns and mountains while dungeons are explored in first person, which was inspired by the 1978 game Escape. The worlds are randomly generated, asking you for a world seed so you can always get the same world if you use the same seed, technically meaning you can collaborate with other players by sharing knowledge as you learn specific worlds. The game takes place in the aftermath of British, the bearer of white light, having driven off the dark lord, Mondain, who spread evil to the land. Now, arguably, you don’t have to, but the game recommends you search for the castle of Lord British, who will task you with slaying various monsters located in these dungeons that are remnants of the dark lord. Apparently Richard Garriott was working at ComputerLand at the time, which was a computer store chain in the 1970’s, and showed the game to his boss, who told him they should sell it in the store! He had his mother draw a logo to sell the game in Ziploc bags, which is the version of packaging I like to see, but it eventually got the attention of California Pacific, who contacted him, wanting to publish it professionally.

Commodore

Back in 1975, electronics company Commodore was beginning to run into a concerning situation when, to compete with the lowering prices of calculators, Texas Instruments entered the market themselves, antiquating those they sold chipsets to like Commodore. Realizing the calculator game was over for them, they would attempt to jump onto the hype of the desktop side of the microcomputer revolution and look to the Apple II to sell. They considered Steve Jobs offer too expensive and decided to make their own computer! The Commodore PET was named after the 1975 Pet Rock craze for their goal of making a pet computer. Despite being sighted as releasing in January of 1977, this seems to only be the date of a Consumer Electronics Show appearance it made after it’s 1976 announcement, but perhaps people could start placing orders at this point. Whenever orders could start being placed, they’d be sent out in late ‘77, starting with developers and magazines in October like Byte, who would later be credited with referring to it as part of their famous trinity of 1977 desktops alongside the Apple II and Tandy-RadioShack Z-80. While all 3 of these computers licensed Microsoft BASIC, having one video game run across all of them did not seem so basic. Ports for games can be years apart, sometimes changing game content and even names like the Commodore version of Kadath, Eye of Kadath, seemingly being far more abridged. I’ve seen some people prefer the more condensed Eye of Kadath, and there can be a strength to the short and sweet format.

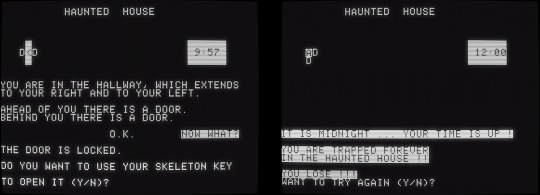

Haunted House – 1979 – Apple II

A common name for a game which wants you to escape said Haunted House by midnight but it’s full of so much danger that you may find yourself trying new things across multiple playthroughs with your eye also on the clock ticking down on the clock ticking down to midnight assuring runs don’t last too long even if you avoid the densely packed danger. It encourages a form of running the game in short, sweet, trial and error attempts to make it easier to approach and just try again on a different day with short play sessions alleviating a bit of concern for how much time you have to set aside. Its writing style is brief, expecting to be repeated instead of approaching writing more like a horror novel as Kadath does.

There is also what I find to be a middle ground to these 2 writing styles in a series that has stood the test of time as fondly looked upon desktop games of the era.

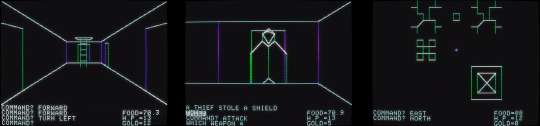

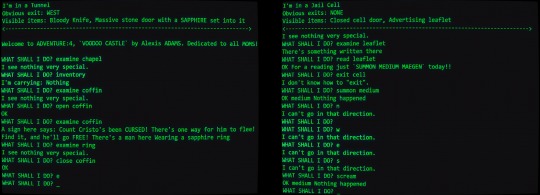

Voodoo Castle – 1979 – Commodore PET, Exidy Sorcerer, TRS-80

Scott Adams had been making computer games since the 1960’s and, as early as 1975, was working on home computers. In ‘78, he would make a game called Adventureland that would find success, and the following year, he and his wife Alexis would found Adventure International, continuing to make these games. Number 4 in the series would be Voodoo Castle, dedicated to all moms and solely credited to Alexis Adams, though Scott, as early as 1981, saying they both worked on it, contrasting with Alexis’s wording in a ‘98 email, has led to a mini-drama over proper credit. The game itself is about you attempting to rescue Count Cristo from the slumber result of the voodoo curse his enemies hexed him with. You begin in a room with Cristo laying in a casket. From here you can explore the residence, which I assume to be the count's, as you can run into a maid who doesn’t seem to fear you as an intruder, leading me to believe you are someone who knows the count looking for something in his spooky dwelling to break the curse. This game is not too tense, but there is the fear of comically being your own undoing, like trying to experiment with the lab chemicals and they blow up in your face or simply examining an open cell in the dungeon and the door closes behind you, accidentally trapping yourself! I can see the appeal of having a simple spooky-themed puzzler like this but was truly surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Something that always stuck in my mind is Tim Schafer remarking how Sandover Village in the first Jak feels like a real town where people live, which creates an effect of dreaming or thinking about wanting to go back and hang out there when you’re not playing the game. It made me realize the deliberateness of making a world capable of building a relationship akin to a hometown with the player as opposed to just being a setting you happen to develop nostalgia for after playing a lot of the game. After only my first time playing Voodoo Castle, I’ve been having that feeling Schafer was talking about, thinking about seeing into the chapel from the room to the south or how I imagined it because I played the text-only version of the game with the environments leaving that positive of an impression on me, but I think what really makes this game work for me is that the word limit for typing a sentence is 2 words. I can’t tell you how intimidated I am by text adventure games, but simplifying it to that makes it very approachable, at least to start off with and explore around without being immediately scared off.

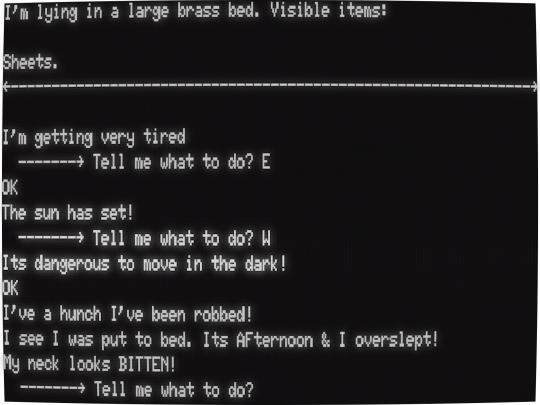

The Count – 1979 - Commodore PET, Exidy Sorcerer, TRS-80

The next game number in the advertised Adventure International series would have you on the other side of a count with you attempting to defeat Count Dracula. After awaking in a bed in Transylvania, you must survive days trying to remain un-hunted by Dracula to hunt him yourself. This game of predator vs. predator felt very tense to me. There can be a spy vs. spy tension of trying to sleep in fear that he’ll get you over night, you being robbed, or even Dracula finding out what you plan to use against him. A 1981 review for this game in Space Gamer magazine mentions using a tent stake as a weapon, but it’s far from as simple as running at the supernatural being. It’s a puzzle game with the added element of having this supernatural wumpus somewhere in the castle, outsmarting you to make you his prey in an instant as you try to do the same back. I may not like puzzle games, but this is a cool idea.

Adventure International opened my mind to text adventures

I used to be too intimidated by the fear of obtuseness to play these kind of games, and, while I may still prefer an action list like Kadath, the illusion of seemingly infinite possibility of just being asked “What do you want to do?” with a text box, including the satisfaction of being surprised when something you type as a joke works, is not lost on me. Simpler games, of course, make it more approachable, and I can imagine the bang for your buck of thinking about a way to progress in the game and coming back to it for a long time, trying to make progress without losing interest in the novelty of doing it on your versatile machine that you want to play with.

0 notes

Note

Hello. So what's the deal with computer chips? Let's say, for example, that I wanted to build a brand new Sega Genesis. Ignoring firmware and software, what's stopping me from dissecting their proprietary chips and reverse-engineering them to make new ones? It's just electric connections and such inside, isn't it? If I match the pin ins and outs, shouldn't it be easy? So why don't people do it?

The answer is that people totally used to do this, there's several examples of chips being cloned and used to build compatible third-party hardware, the most famous two examples being famiclones/NESclones and Intel 808X clones.

AMD is now a major processor manufacturer, but they took off in the 70's by reverse-engineering Intel's 8080 processor. Eventually they were called in to officially produce additional 8086 chips under license to meet burgeoning demand for IBM PC's, but that was almost a decade later if I remember correctly.

There were a ton of other 808X clones, like the Soviet-made pin-compatible K1810VM86. Almost anyone with a chip fab was cloning Intel chips back in the 80's, a lot of it was in the grey area of reverse engineering the chips.

Companies kept cloning Intel processors well into the 386 days, but eventually the processors got too complicated to easily clone, and so only companies who licensed designs could make them, slowly reducing the field down to Intel, AMD, and Via, who still exist! Via's CPU division currently works on the Zhaoxin x86_64 processors as part of the ongoing attempts to homebrew a Chinese-only x86 processor.

I wrote about NES clones a while ago, in less detail, so here's that if you want to read it:

Early famiclones worked by essentially reverse-engineering or otherwise cloning the individual chips inside an NES/famicom, and just reconstructing a compatible device from there. Those usually lacked any of the DRM lockout chips built into the original NES, and were often very deeply strange, with integrated clones of official peripherals like the keyboard and mouse simply hardwired directly into the system.

These were sold all over the world, but mostly in developing economies or behind the Iron Curtain where official Nintendo stuff was harder to find. I had a Golden China brand Famiclone growing up, which was a common famiclone brand around South Africa.

Eventually the cost of chip fabbing came down and all those individual chips from the NES were crammed onto one cheap piece of silicon and mass produced for pennies each, the NES-on-a-chip. With this you could turn anything into an NES, and now you could buy a handheld console that ran pirated NES game for twenty dollars in a corner store. In 2002. Lots of edutainment mini-PC's for children were powered by these, although now those are losing out to Linux (and now Android) powered tablets a la Leapfrog.

Nintendo's patents on their hardware designs expired throughout the early 2000's and so now the hardware design was legally above board, even if the pirated games weren't. You can still find companies making systems that rely on these NES chips, and there are still software houses specializing in novel NES games.

Why doesn't this really happen anymore? Well, mostly CPU's and their accoutrements are too complicated. Companies still regularly clone their competitors simpler chips all the time, and I actually don't know if Genesis clones exist, it's only a Motorola 68000k, but absolutely no one is cloning a modern Intel or AMD processor.

The die of a Motorola 68000 (1979)

A classic Intel 8080 is basically the kind of chip you learn about in entry level electrical engineering, a box with logic gates that may be complicated, but pretty straightforwardly fetches things from memory, decodes, executes, and stores. A modern processor is a magic pinball machine that does things backwards and out of order if it'll get you even a little speedup, as Mickens puts it in The Slow Winter:

I think that it used to be fun to be a hardware architect. Anything that you invented would be amazing, and the laws of physics were actively trying to help you succeed. Your friend would say, “I wish that we could predict branches more accurately,” and you’d think, “maybe we can leverage three bits of state per branch to implement a simple saturating counter,” and you’d laugh and declare that such a stupid scheme would never work, but then you’d test it and it would be 94% accurate, and the branches would wake up the next morning and read their newspapers and the headlines would say OUR WORLD HAS BEEN SET ON FIRE. You’d give your buddy a high-five and go celebrate at the bar, and then you’d think, “I wonder if we can make branch predictors even more accurate,” and the next day you’d start XOR’ing the branch’s PC address with a shift register containing the branch’s recent branching history, because in those days, you could XOR anything with anything and get something useful, and you test the new branch predictor, and now you’re up to 96% accuracy, and the branches call you on the phone and say OK, WE GET IT, YOU DO NOT LIKE BRANCHES, but the phone call goes to your voicemail because you’re too busy driving the speed boats and wearing the monocles that you purchased after your promotion at work. You go to work hung-over, and you realize that, during a drunken conference call, you told your boss that your processor has 32 registers when it only has 8, but then you realize THAT YOU CAN TOTALLY LIE ABOUT THE NUMBER OF PHYSICAL REGISTERS, and you invent a crazy hardware mapping scheme from virtual registers to physical ones, and at this point, you start seducing the spouses of the compiler team, because it’s pretty clear that compilers are a thing of the past, and the next generation of processors will run English-level pseudocode directly.

Die shot of a Ryzen 5 2600 core complex (2019)

Nowadays to meet performance parity you can't just be pin-compatible and run at the right frequency, you have to really do a ton of internal logical optimization that is extremely opaque to the reverse engineer. As mentioned, Via is making the Zhaoxin stuff, they are licensed, they have access to all the documentation needed to make an x86_64 processor, and their performance is still barely half of what Intel and AMD can do.

Companies still frequently clone each others simpler chips, charge controllers, sensor filters, etc. but the big stuff is just too complicated.

182 notes

·

View notes