#Jornada del Muerto

Text

It’s one thing standing in line to watch the blockbuster film “Oppenheimer.” It’s another thing entirely queueing up in a remote desert to experience the location of the film’s most pivotal scene.

But if you’re a fan of atomic history and can swing central New Mexico this October, your pilgrimage through the Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Journey) will be so worth the effort.

Saturday, October 21, presents a rare opportunity to visit not just one but two scientifically significant and movie-famous destinations on the same day – each occupying opposite ends of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Trinity Site is the national historic landmark that’s home to mankind’s first nuclear blast on July 16, 1945, where plutonium gamma rays lit up the night sky. It hosts only two open house events each year.

And while you’re in the area, an extraordinary bonus is a second, free-of-charge open house aimed specifically at Trinity Site adventurers who are willing to drive another 100 miles to take in a second mind-bending experience.

It’s the Very Large Array Radio Observatory (VLA), which was dramatized in the 1997 alien-life movie “Contact.” The VLA telescope can spread wider than New York City, able to capture the whispers of distant radio waves as they undulate across our cosmos.

Rare access to Trinity Site

Trinity Site opens only two Saturdays a year. Once in April, and lucky for “Oppenheimer” enthusiasts, again in October.

The exact dates are announced in advance each year by the US Army.

The site is a secure military installation within the forbidding White Sands Missile Range, where live weapons are regularly tested. The terrain is high desert plateau, dotted with creosote brush and not much else.

In our everyday crush of crowds, traffic and strip malls, the Land of Enchantment’s sheer miles of open landscape and soul-nourishing cobalt vistas inspire. Buzz Aldrin’s impression of the moon’s surface parallels Trinity Site, a “magnificent desolation.”

When J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” led his Manhattan Project team to Trinity, it wasn’t just for the isolation. He had history with New Mexico, attending summer boys’ camps during his youth. Because of the popularity of the movie “Oppenheimer,” a surge of visitors is expected on October 21.

The open house event, hosted by the US Army, is free but limited to the first 5,000 guests, on a first-come, first-served basis.

How to get there

From Albuquerque International Sunport airport, your best bet is a rental car for the two-hour drive south. It’s easy to get disoriented while navigating, so stick to the Army’s directions, as GPS instructions can be wonky. Take screen photos of the route mapped on your phone – as you may lose cell service – and have an actual roadmap as backup.

Aim to arrive at Trinity’s Stallion Gate before 8 a.m., when the gate opens. There will already be a line. Be early, and you’ll still have plenty of time for the day’s second adventure. Army officials will check your ID at the gate, and from there it’s a 17-mile (27-kilometer) drive to a parking lot located a quarter-mile walk from the reason you came – Ground Zero.

Trinity Site’s atmosphere during an open house is reminiscent of a small-town carnival from a bygone era. Vendors selling souvenir trinkets. Kids in strollers. Dogs wagging tails. Porta Potties. That’s until you notice the pop-up tent displaying Geiger counters. And another with radioactive Trinitite, the mysterious green-glass rock that rained down from the bomb’s blast.

Ominous fence signs remind guests that it’s against the law to remove any pieces of Trinitite they spy on the ground because ingested fragments retain enough radioactivity to be dangerous.

The famed 1918 McDonald adobe ranch house, where the bomb’s critical plutonium core was assembled in the master bedroom, survived the shock wave two miles away mostly intact. Buses shuttle visitors back and forth free of charge from the Trinity parking lot to the McDonald house.

Venture in farther to stand next to a life-size replica of Fat Man, the nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945.

Visitors can pose for photos inside Jumbo, the 216-ton steel cylinder scientists contemplated detonating the bomb – nicknamed the Gadget – within to contain its plutonium core if the full detonation failed.

Experiencing Ground Zero

The moment arrives to approach Ground Zero, marked simply by a black stone obelisk that’s 12 feet (3.66 meters) high.

Step back in time to the pre-dawn of July 16, 1945. Glance north, west and south where Oppenheimer’s team hunkered down in three bunkers, five miles away. You stand where the course of humanity shifted. Where the boundaries of physics and possibility stretched.

Picture the 100-foot-high steel tower that stood where the obelisk stands now. A few feet away only nubs of the tower remain, the bulk annihilated in the blast.

See in your mind the mattresses hauled in and stacked high to cushion the fall should the chains snap as they winched the heavy Gadget high into the air. And young scientists rotated throughout the night babysitting the bomb as crackles of lightning threatened to strike.

Oppenheimer wrote the poem “Crossing” two decades before Trinity. His words contained the prophetic passage, “…in the dry hills down by the river, half withered, we had the hot winds against us.” He could not have imagined the heat to come.

Now close your eyes.

Ignore what you do see to imagine the history you cannot see.

The storms over the mountains. New Mexico Gov. John Dempsey is at home asleep, oblivious to when the blast will occur. Finally, the mists of rain clear. The countdown to fission begins. There’s a sense of dread, however remote, that Earth’s atmosphere might ignite in a cataclysmic chain reaction.

And finally, the detonation.

Man’s first nuclear genie shatters its bottle, unleashing the ferocity of the atom, with an explosion 10,000 times hotter than our sun. Thirty-seven minutes later, the wounded sky brightens again, to the dawn of man’s first atomic sunrise.

Reflect on the glaring omission that while the area surrounding Trinity was remote, it was not unpopulated.

Civilians termed “downwinders,” subjected to radioactive fallout fluttering down from the sky, were assured that the flash and fury some saw and heard was an ammunition explosion at nearby Alamogordo Air Base. After atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month, they realized the stark truth.

Jim Eckles, an Army historian who oversaw decades of Trinity open house events, shared the site’s significance: “The ‘Oppenheimer’ movie resurrected concerns we’ve lost sight of. That thousands of nuclear warhead missiles are still out there, able to launch. We need clever intelligent people to deal with the sequence that began at Trinity.”...'

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

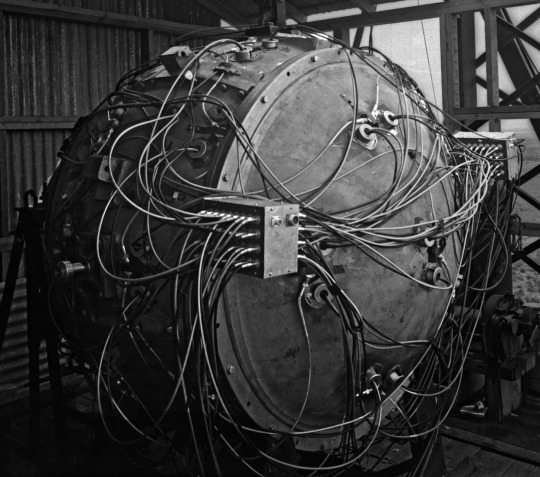

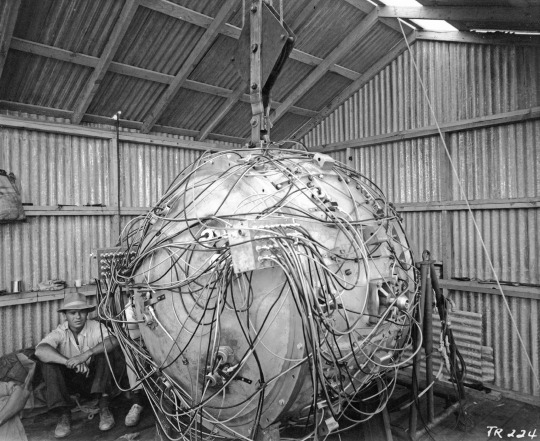

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

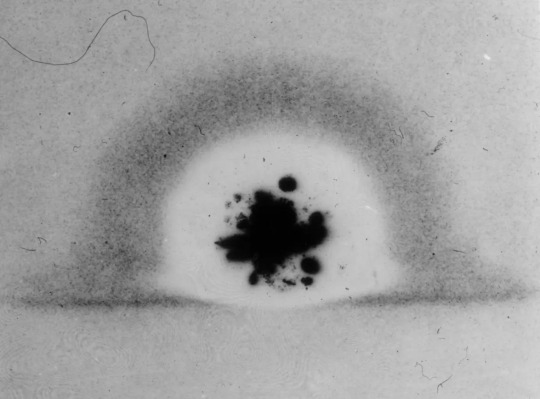

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

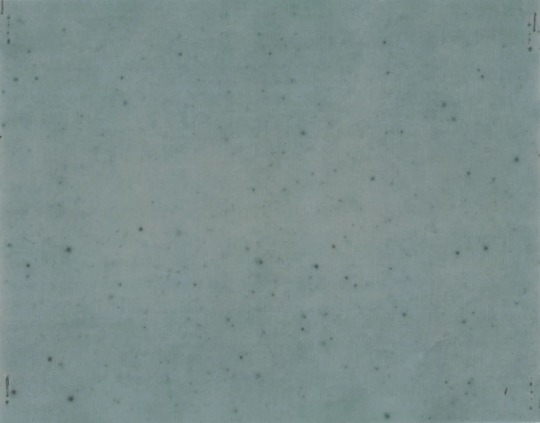

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

en un futuro en chimera au:

Charlie se encontraba sentada frente a la televisión.

Charlie: las cartas de los "fanaticos" de Adam hoy fueron menos, espero que eso signifique dejaran de enviarlas en algun momento.

TV: inicio genérico de noticias

Katy: soy Katy killjoy

Tom: y yo tom t....

Katy: aquien le importas tom! Comenzamos la jornada comunicando que los premios bestboob an comenzado.

Tom: si los premios sobre las 2 mejores cosas del cine, televisión fotografía, cielos 2 cosas que yo mataría por tocar.

Katy le lanza un café caliente a tom

Katy: estas bastante caliente tom.

Tom: Ahhhhhhhhhhh!!!!

katy: entre los participantes a ganar tenemos a Susana banana, Lola toys, y el favorito de todos Adam el primer hombre.

Katy: es increíble como varios videos tomados por celular pudieron romper la Internet y estar entre los favoritos de las páginas porno por meses. Vaya que todos son unos degenerados jaja.

Charlie ya no escucha

Charlie: bueno eso solo significa que el correo aumentará, que podría ser peor.

Katy: ahora mostraremos en vivo que piensan los pervertidos sobre este concurso.

Imp reportero: y bien señor que opina sobre los bestboob.

Sinner babosa: bueno como todo un conocedor del tema y un estudioso del cuerpo femenino....

El pecador es apartado bruscamente por lucifer.

Lucifer: como su rey exijo que se reconozca quien tiene las mejores tetas de todo el infierno y es....

Charlie: Papá noooo!!! Ahora si que podría ser peor.

Una voz suena detrás de Charlie.

Michael: El esta muerto.

||🔱🪹 Chimera! Adam AU 🪹🔱||

Tom: ¡El ganador de las BestBoobs! ¡Adam, el primer hombre! ¡Quien parece que no sabe que carajo está pasando!

Michael está entre un "estoy feliz y enojado" y también está entre causar un genocidio que puede incluir a varios hellborns sin importarle un carajo el tratado.

Adán solo está ahí para disfrutar del caos.

#hazbin hotel#hazbin hotel fandom#hazbin hotel adam#hazbin adam#adam hazbin hotel#hazbin hotel au#hazbin lucifer#hazbin hotel lucifer#adamsapple#lucifer hazbin hotel#lucifer x adam#adam x lucifer#michael hazbin hotel#hazbin hotel michael#adam x michael#michael x adam#guitarhero#guitarduck#Chimera!Adam AU🪹

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Estos hechos, que sacuden la conciencia del mundo civilizado, no son sin embargo los que mayores sufrimientos han traído al pueblo argentino ni las peores violaciones de los derechos humanos en que ustedes incurren. En la política económica de ese gobierno debe buscarse no sólo la explicación de sus crímenes sino una atrocidad mayor que castiga a millones de seres humanos con la miseria planificada.

En un año han reducido ustedes el salario real de los trabajadores al

40%, disminuido su participación en el ingreso nacional al 30%, elevado de 6 a 18 horas la jornada de labor que necesita un obrero para pagar la canasta familiar , resucitando así formas de trabajo forzado que no persisten ni en los últimos reductos coloniales.

Congelando salarios a culatazos mientras los precios suben en las puntas de las bayonetas, aboliendo toda forma de reclamación colectiva, prohibiendo asambleas y comisioncs internas, alargando horarios, elevando la desocupación al récord del 9% prometiendo aumentarla con 300.000 nuevos despidos, han retrotraído las relaciones de producción a los comienzos de la era industrial, y cuando los trabajadores han querido protestar los han calificados de subversivos, secuestrando cuerpos enteros de delegados que en algunos casos aparecieron muertos, y en otros no aparecieron.

Los resultados de esa política han sido fulminantes. En este primer año de gobierno el consumo de alimentos ha disminuido el 40%, el de ropa más del 50%, el de medicinas ha desaparecido prácticamente en las capas populares. Ya hay zonas del Gran Buenos Aires donde la mortalidad infantil supera el 30%, cifra que nos iguala con Rhodesia, Dahomey o las Guayanas; enfermedades como la diarrea estival, las parasitosis y hasta la rabia en que las cifras trepan hacia marcas mundiales o las superan. Como si esas fueran metas deseadas y buscadas, han reducido ustedes el presupuesto de la salud pública a menos de un tercio de los gastos militares, suprimiendo hasta los hospitales gratuitos mientras centenares

de médicos, profesionales y técnicos se suman al éxodo provocado por el terror, los bajos sueldos o la "racionalización".

Fragmento de la Carta Abierta a la Junta Militar de Rodolfo Walsh, 24 de marzo de 1977. Vale la pena leerla por lo escalofriante de su actualidad. El neoliberalismo, liberalismo o anarcoliberalismo o como sea quiera llamarse este horror, siempre se impuso por la fuerza, siempre produjo dolor.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Quien Está Leyéndome/To the One Who Is Reading Me

Eres invulnerable. ¿No te han dado

los números que rigen tu destino

certidumbre de polvo? ¿No es acaso

tu irreversible tiempo el de aquel río

en cuyo espejo Heráclito vio el símbolo

de su fugacidad? Te espera el mármol

que no leerás. En él ya están escritos

la fecha, la ciudad y el epitafio.

Sueños del tiempo son también los otros,

no firme bronce ni acendrado oro;

el universo es, como tú, Proteo.

Sombra, irás a la sombra que te aguarda

fatal en el confín de tu jornada;

piensa que de algún modo ya estás muerto.

You are invulnerable. Didn’t they deliver

(those forces that control your destiny)

the certainty of dust? Couldn’t it be

your irreversible time is that river

in whose bright mirror Heraclitus read

his brevity? A marble slab is saved

for you, one you won’t read, already graved

with city, epitaph, dates of the dead.

And other men are also dreams of time,

not hardened bronze, purified gold. They’re dust

like you; the universe is Proteus.

Shadow, you’ll travel to what waits ahead,

the fatal shadow waiting at the rim.

Know this: in some way you’re already dead.

Jorge Luis Borges

In El Otro, El Mismo, 1964

trans. Tony Barnstone

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tracklist:

The Requiem

The Radiance

Burning In The Skies

Empty Spaces

When They Come For Me

Robot Boy

Jornada Del Muerto

Waiting For The End

Blackout

Wretches And Kings

Wisdom, Justice, And Love

Iridescent

Fallout

The Catalyst

The Messenger

Spotify | YouTube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: linkin park#language: english#language: japanese#decade: 2010s#Art Rock#Pop Rock#Electronic#Alternative Rock#Ambient#Industrial Hip Hop#Hip Hop#Rap Rock#Post-Industrial#Experimental Hip Hop

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Año nuevo en el mal

Con Enriqueta llevamos tres años juntos; como todos los pololos después de tanto tiempo, nos detestamos con juvenil entusiasmo. Cada semana nos mandamos a la chucha y humillamos en público; de vez en cuando, muertos de curados, nos pegamos sus buenos coscachos para el deleite de familiares y conocidos. ¿Y por qué chucha seguimos juntos? Porque nos amamorsh demasiadorsh y nadie puede comprender los pequeños inconvenientes domésticos, magulladuras, ojos en tinta y TECs abiertos causados por quererse tanto.

Un buen día -hastiados de la rutina de poca cacha y mucho charchazo- decidimos que sería una estupenda idea pasar el Año Nuevo en Valparaíso. Tomaditos de la mano, contemplaríamos en vivo el espectáculo pirotécnico que cada 1 de enero deleita al pueblo enfiestado a través de la señal de UCV Televisión.

Acompañados de dos de sus amiguetes, partimos ese 31 de diciembre a las 5 PM hacia el litoral; llenos de esperanza, nos prometemos una jornada inolvidable. El taco para el peaje de Lo Prado, empero, comienza a la altura de Matucana: Enriqueta, algo irritada, me culpa hasta del calentamiento global. “Hueón reculiao, ¿cómo se te ocurre partir tan tarde, maricón reconchetumare hijo de la gran perra”, me explica frente al respetable. Yo manejo nomás. Tras cuatro horas de agradable viaje llegamos al puerto; aunque los ánimos están algo caldeados, pongo mi mejor cara de imbécil y pago con alegría las cinco lucas que nos cobra un joven emprendedor para no hacernos bolsa el auto.

Partimos entonces a buscar un mirador desde el cual disfrutar de los fuegos artificiales. Enriqueta, siempre sedienta, saca un par de botellas de piscola hecha en casa que procede a empinarse al seco sin siquiera convidar. Como resulta fácil de adivinar, la inmunda ciudad transpira gente y encontrar un puto sitio vacío es misión imposible. Caminamos como los hueones por todos los cerros de basura y el borde costero mientras mi amorcito luce una cara cada vez más cercana a la del Chacal de Nahueltoro antes de pitearse a toda su familia. Tiemblo anticipando una tragedia.

Entonces, de milagro, diviso en lontananza un huequito al lado del mar. “¡Te dije que íbamos a pasarlo la raja!”, le grito triunfal tras acomodar nuestros culos en la piedra minutos antes del inicio del show. Cuando estalla el primer petardo, abrazo conmovido a la compañera de mis días, quien refleja en sus ojos algo que podríamos denominar cariño embrutecido.

Veinte segundos más tarde, sin embargo, sucede lo inevitable: desde los cerros baja la catarata de aguas servidas que cae el mar justo debajo nuestro, pues estamos sentados sobre el desagüe una matriz de alcantarillado (lo que explica la total ausencia de parroquianos alrededor nuestro). Y así, mojaditos y bien pasados a caca, pasamos el resto de la noche insultándonos y sacándonos cresta y media.

#chilegram#cuentos#escritos#frases#chile tumblr#chilensis#tumblr chilenito#tumblr chilensis#chilean#andateala.com#distemper#archivo#chile#santiago de chile#valpo#valparaiso

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᴀɢᴏꜱᴛᴏ, ᴍᴀʀᴛᴇꜱ

Mirar tus costas, por este catalejo triste de vidrios rotos, me hace tan mal. Ya puedo decir que tengo el vicio del que acaricia los filos de las lanzas, del que solo ve enemigos en los reflejos, del que cree que sirve de algo ignorar las horas que pasan.

No tengo tiempo de escribir ahora. No puedo arruinar más noches. Dejo estas últimas palabras: mirar lejanas tus costas hiere.

La luz de tus astros ya formó otras constelaciones. El astrónomo que interpreta los signos de mi historia ya me ha dicho que te has muerto y que yo también, y que se agotó el tiempo de hacer los cantos, los ritos y las sepulturas. Que ahora ya tengo el aura del cuerpo putrefacto. Que no aceptar la muerte e irme a los infiernos fue digno en las primeras jornadas, pero que ahora esto que soy y que paseo ya se parece demasiado al hartazgo, al vicio y a la molestia. Pero no quiero morir, y no sé qué es morir. Yo creí aceptar la muerte, hubo dos noches que se le parecieron tanto.

Pero en algo fallé. Hubo ciertas cosas que no pude sepultar. No sé qué esperanza tan triste, tan abominable, tan mínima, tan triste guardo. Tengo que entender definitivamente, antes de que sigan pasando las horas, antes de que los astros sigan danzando y yo siga perdiendo sus cruces, sus cifras y sus textos mirando hacia adentro como el que busca en el pozo lo que no está, tengo que entender, quiero decir, que nunca vas a volver. Que los planetas se alejan para no volver. Que pierden el calor para no recuperarlo. Que nada viaja más rápido que la luz salvo el olvido. Que no sirve correr en dirección contraria a mis órbitas solo para buscar las tuyas, que ya ni sé leer -ya se cifran en otras lenguas, ya no sé resolver sus ecuaciones-. El espacio que nos aleja se expande con los minutos, y sé que a vos te da paz y que a mí me hiere como la rotura desangra los vasos que alguna vez estuvieron llenos.

Pero no puedo perder más tiempo y más horas de sueño en fabricarme estas tragedias. Estas mentiras que hago para desaguar presuntas inundaciones que solo yo veo. Estas interpretaciones interminables y dañinas que no me sirven para nada, solo para repetirme: ʜᴀꜱ ᴍᴜᴇʀᴛᴏ ʏ ᴇʀᴇꜱ ɪɴꜰᴇʟɪᴢ.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early in the morning of July 16, 1945, before the sun had risen over the northern edge of New Mexico’s Jornada Del Muerto desert, a new light—blindingly bright, hellacious, blasting a seam in the fabric of the known physical universe—appeared. The Trinity nuclear test, overseen by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, had filled the predawn sky with fire, announcing the viability of the first proper nuclear weapon and the inauguration of the Atomic Era. According to Frank Oppenheimer, brother of the “Father of the Bomb,” Robert’s response to the test’s success was plain, even a bit curt: “I guess it worked.”

With time, a legend befitting the near-mythic occasion grew. Oppenheimer himself would later attest that the explosion brought to mind a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, the ancient Hindu scripture: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.” Later, toward the end of his life, Oppenheimer plucked another passage from the Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Christopher Nolan’s epic, blockbuster biopic Oppenheimer prints the legend. As Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) gazes out over a black sky set aflame, he hears his own voice in his head: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The line also appears earlier in the film, as a younger “Oppie” woos the sultry communist moll Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh). She pulls a copy of the Bhagavad Gita from her lover’s bookshelf. He tells her he’s been learning how to read Sanskrit. She challenges him to translate a random passage on the spot. Sure enough: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” (That the line comes in a postcoital revery—a state of bliss the French call la petite mort, “the little death”—and amid a longer conversation about the new science of Freudian psychoanalysis—is about as close to a joke as Oppenheimer gets.)

As framed by Nolan, who also wrote the screenplay, Oppenheimer's cursory knowledge of Sanskrit, and Hindu religious tradition, is little more than another of his many eccentricities. After all, this is a guy who took the “Trinity” name from a John Donne poem; who brags about reading all three volumes of Marx’s Das Kapital (in the original German, natch); and, according to Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s biography, American Prometheus, once taught himself Dutch to impress a girl. But Oppenheimer’s interest in Sanskrit, and the Gita, was more than just another idle hobby or party trick.

In American Prometheus, credited as the basis for Oppenheimer, Bird and Sherwin depict Oppenheimer as more seriously committed to this ancient text and the moral universe it conjures. They develop a resonant image, largely ignored in Nolan’s film. Yes, it’s got the quote. But little of the meaning behind it—a meaning that illuminates Oppenheimer’s own conception of the universe, of his place in it, and of his ethics, such as they were.

Composed sometime in the first millennium, the Bhagavad Gita (or “Song of God”) takes the form of a poetic dialog between a warrior-prince named Arjuna and his charioteer, the Hindu deity Krishna, in unassuming human form. On the cusp of a momentous battle, Arjuna refuses to engage in combat, renouncing the thought of “slaughtering my kin in war.” Throughout their lengthy back-and-forth (unfolding over some 700 stanzas), Krishna attempts to ease the prince’s moral dilemma by attuning him to the grander design of the universe, in which all living creatures are compelled to obey dharma, roughly translated as “virtue.” As a warrior, in a war, Krishna maintains that it is Arjuna’s dharma to serve, and fight; just as it is the sun’s dharma to shine and water’s dharma to slake the thirsty.

In the poem’s ostensible climax, Krishna reveals himself as Vishnu, Hinduism’s many-armed (and many-eyed and many-mouthed) supreme divinity; fearsome and magnificent, a “god of gods.” Arjuna, in an instant, comprehends the true nature of Vishnu and of the universe. It is a vast infinity, without beginning and end, in a constant process of destruction and rebirth. In such a mind-boggling, many-faced universe (a “multiverse,” in the contemporary blockbuster parlance), the ethics of an individual hardly matter, as this grand design repeats in accordance with its own cosmic dharma. Humbled and convinced, Arjuna takes up his bow.

As recounted in American Prometheus, the story had a significant impact on Oppenheimer. He called it “the most beautiful philosophical song existing in any known tongue.” He praised his Sanskrit teacher for renewing his “feeling for the place of ethics.” He even christened his Chrysler Garuda, after the Hindu bird-deity who carries the Lord Vishnu. (That Oppenheimer seems to identify not with the morally conflicted Arjuna but with the Lord Vishnu himself may say something about his own sense of self-importance.)

“The Gita,” Bird and Sherwin write, “seemed to provide precisely the right philosophy.” Its prizing of dharma, and duty as a form of virtue, gave Oppenheimer’s anguished mind a form of calm. With its notion of both creation and destruction as divine acts, the Gita offered Oppenheimer a frame of making sense of (and, later, justifying) his own actions. It’s a key motivation in the life of a great scientist and theoretician, whose work was marshaled toward death. And it’s precisely the sort of idea Nolan rarely lets seep into his movies.

Nolan’s films—from the thriller Memento and his Batman trilogy to the sci-fi opera Interstellar and the time-reversal blockbuster Tenet—are ordered around puzzles and problem-solving. He establishes a dilemma, provides the “rules,” and then sets about solving that dilemma. For all his sci-fi high-mindedness, he allows very little room for questions of faith or belief. Nolan's cosmos is more like a complicated puzzle box. He has popularized a kind of sapio-cinema, which makes a virtue of intelligence without being itself highly intellectual.

At their best, his movies are genuinely clever in conceit and construct. The one-upping stage magicians of The Prestige, who go mad trying to best one another, are distinctly Nolanish figures. The tripartite structure of Dunkirk—which weaves together plot lines that unfold across distinct periods of time—is likewise inspired. At their worst, Nolan’s films collapse into ponderousness and pretension. The barely scrutable reality-distortion mechanics of Inception, Interstellar, and Tenet smack of hooey.

Oppenheimer seems similarly obsessed with problem-solving. First, Nolan sets up some challenges for himself. Such as: how to depict a subatomic fission reaction at Imax scale or, for that matter, how to make a biopic about a theoretical physicist as a broadly entertaining summer blockbuster. Then he sets to work. To his credit, Oppenheimer unfolds breathlessly and succeeds making dusty-seeming classroom conversations and chatty closed-door depositions play like the stuff of a taut, crowd-pleasing thriller. The cinematography, at both a subatomic and megaton scale, is also genuinely impressive. But Nolan misses the deeper metaphysics undergirding the drama.

The movie depicts Murphy’s Oppenheimer more as a methodical scientist. Oppenheimer, the man, was a deep and radical thinker whose mind was grounded by the mystical, the metaphysical, and the esoteric. A film like Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life shows that it is possible to depict these sort of higher-minded ideas at the grand, blockbuster scale, but it’s almost as if they don’t even occur to Nolan. One might, charitably, claim that his film’s time-jumping structure reflects the Gita’s notion of time itself as nonlinear. But Nolan’s reshuffling of the story’s chronology seems more born of a showman’s instinct to save his big bang for a climax.

When the bomb does go off, and its torrents of fire fill the gigantic Imax screen, there’s no sense that the Lord Vishnu, the mighty one, is being revealed in that “radiance of a thousand suns.” It’s just a big explosion. Nolan is ultimately a journeyman technician, and he maps that personality onto Oppenheimer. Reacting to the horrific, militarily unjustifiable bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima (which are never depicted on-screen), Murphy’s Oppenheimer calls them “technically successful.”

Judged against the life of its subject, Oppenheimer can feel like a bit of let down. It fails to comprehend the woolier, yet more substantial, worldview that animated Oppie’s life, work, and own moral torment. Weighed against Nolan’s own, more purely practical, ambitions, perhaps the best that can be said of Oppenheimer is that—to paraphrase the physicist’s actual reported comments, uttered at his moment of ascension to the status of godlike world-destroyer—it works. Successful, if only technically.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Escucha el calor

Estoy sentado en mi estudio, con la persiana a medio bajar, escuchando el calor; el intenso calor del resistero en esta jornada del 25 de julio —día de Santiago Apóstol— en Madrid.

Entre sesión y sesión de escucha fumo algún cigarrillo, bebo té, leo cuentos de Maupassant en una edición de obras completas del francés, para kindle, en clásica traducción inglesa.

El mundo está parado. Suena el reloj de pared —mi «reloj de pájaros»— en la suave penumbra. Se está muy bien. Tanto es así que la inercia del reposo, físico y mental, me adormece bajo un manto de sutil y lánguida pereza y se me hace cuesta arriba redactar estas líneas. Son típicos párrafos de escritura canicular, engarzados en esos característicos tiempos muertos de desfibrada inacción que el mucho calor engendra. El verano es tiempo de aburrimiento; de una especie de esplín baudelaireano a la inversa (no se me ocurre ningún verso ni pasaje de Baudelaire ambientado en horas tórridas, aunque es posible que me falle la memoria).

Todo late, sin embargo, bajo la superficie del oído y de la propia piel. Un estremecimiento de posibilidades bulle a muy lento fuego en el fondo de la olla de la mente. Más tarde, cuando haya caído el crepúsculo y descienda su frescor sobre la tierra, subiré la persiana, airearé el despacho, y veré qué puedo hacer con los lentos posos aún calientes de este día, tan señalado por su fecha, de lasitud y aparente intrascendencia.

ROGER WOLFE · Julio de 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#linkin park#music#rap rock#nu metal#chester bennington#mike shinoda#hybrid theory#meteora#minutes to midnight#a thousand suns#living things#the hunting party#interlude

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atomic Secrets: The Scientists Who Built The Atom Bomb 💣

Science and the military converged under a cloak of secrecy at Los Alamos National Laboratory. As part of the Manhattan Project, Los Alamos — both its very existence and the work that went on there — was hidden from Americans during World War II.

Many of the thousands of scientists on the project were not officially aware of what they were working on. Though they were not permitted to talk to anyone about their work, including each other, by 1945 some had figured out that they were in fact building an atomic bomb.

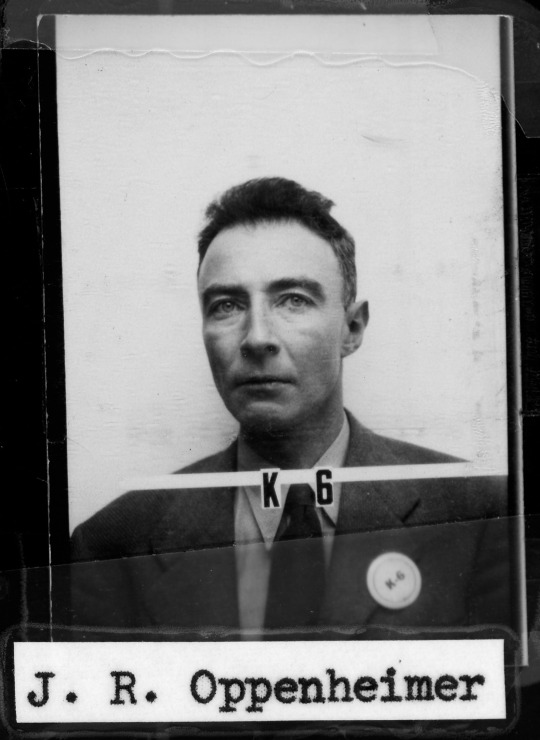

In 1943 J. Robert Oppenheimer was named the director of the Bomb Project at Los Alamos, a self-contained area protected -- and completely controlled -- by the U.S. Army. Special driver's licenses had no names on them, just ID numbers. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Robert Oppenheimer's wife Kitty was not above scrutiny. All who were affiliated with the project -- and their spouses -- were thoroughly screened and had a security file with the FBI. Credit: Courtesy of the F.B.I.

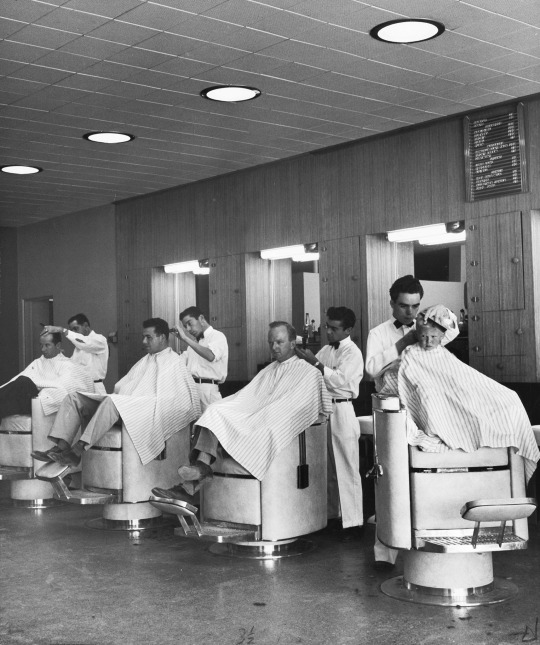

Less than a year after Oppenheimer proposed using the remote desert site for the laboratory, Los Alamos was already home to a thousand scientists, engineers, support staff… and their families. By the end of the war the population was over 6,000, and the compound included amenities like this barber shop. Credit: Time Life/Getty Images

Atomic Bomb Project employees having lunch at Los Alamos. Though food was often in scant supply, residents made the best of life in their isolated community by putting on plays and organizing Saturday night square dances. Some singles’ parties in the dormitories reportedly served a brew of lab alcohol and grapefruit juice, cooled with dry ice out of a 32-gallon GI can. Credit: Copyright Bettmann/CORBIS

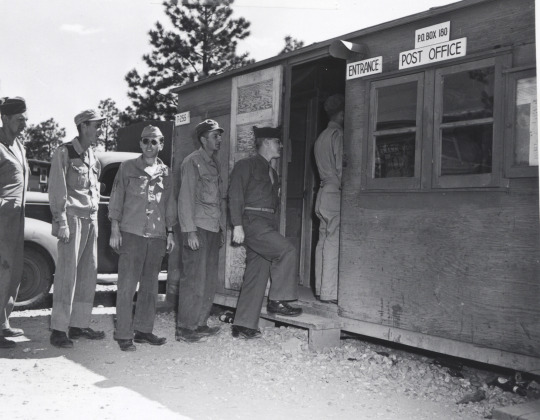

Completely self-contained, the Los Alamos facility did not officially exist in its early years except as a post office box. Scientists’ families were mostly kept in the dark about the nature of the project, learning the truth only after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Credited with inventing the cyclotron, University of California-Berkeley physicist Ernest Lawrence (squatting, center) looks on as Robert Oppenheimer points out something on the 184” particle accelerator. Harvard University supplied the cyclotron that was used to develop the atomic bomb. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

The Trinity bomb was the first atomic bomb ever tested. It was detonated in the Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Walk) Desert, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. The test was a resounding success. The United States would drop similar bombs on Japan just three weeks later. Credit: Courtesy of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives

Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves inspect the melted remnants of the 100-foot steel tower that held the Trinity bomb. Ensuring that the testing of a bomb with unknown strength would remain completely secret, the government chose a location that was so remote they had to import their water from over 150 miles away. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves stand in front of a map of Japan, just five days before the bombing of Hiroshima. Credit: Copyright CORBIS

Though there was no evidence that Oppenheimer had betrayed his country in any way, several officials called his loyalty into question in the Cold War environment of 1954. After being subjected to months of hearings, “the most famous physicist in the world” eventually lost his government security clearance. Credit: Reprinted courtesy of TIME Magazine

#Atomic Secrets#Scientists#Atomic Bomb#American 🇺🇸 Experience#NOVA | PBS#Los Alamos National Laboratory#Manhattan Project#World War II#J. Robert Oppenheimer#Katherine Oppenheimer#New Mexico#Hiroshima | Nagasaki#University of California-Berkeley#Harvard University#Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Walk) Desert 🐪#Alamogordo New Mexico#General Leslie Groves#Japan 🇯🇵#TIME Magazine

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

And that was the grief that dazzled: knowing there are things that should destroy us that don't destroy us.

- Carrie Fountain, from "Jornada del Muerto," Burn Lake

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Album Review: A Thousand Suns- Linkin Park

Release Date:

September 13 2010

Tracklist:

The Requiem

The Radiance

Burning in the Skies

Empty Spaces

When They Come For Me

Robot Boy

Jornada Del Muerto

Waiting for the End

Blackout

Wretches and Kings

Wisdom, Justice, and Love

Iridescent

Fallout

The Catalyst

The Messenger

Favorite Track:

The Catalyst

Least favorite track:

When they come for me

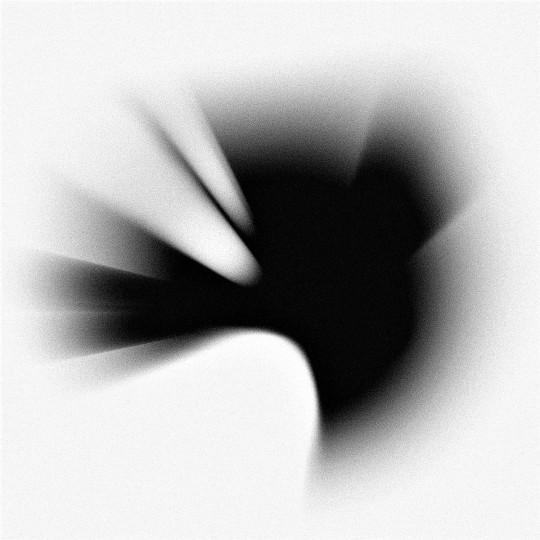

Album art opinions:

The album cover is an abstract depiction of the earth exploding with nuclear power, and if tilted 90 degrees to the left, looks vaguely like a skull. This is all very fitting, as this is a concept album about fear, annihilation, and specifically, nuclear war. The title of the album, "a thousand suns" is in reference to the first nuclear bombs being described to be "as bright as a thousand suns"

Color: 3/10

Recognizability: 1/10

Vibes: 5/10

Total: 3/10

Music opinions/notes:

As a concept album, it is very well made, there are several interludes inbetween songs to help transition from one Track to the next, but several handle that transition on their own. This does make the album a relatively easy listen, as there's no jarring changes between tracks, however this is not always for the benefit of the album. Because of the calmer tone of the record and the tracks bleeding so seamlessly between one another, it's hard to pick a standout track. The whole album feels like it's one big song, and considering it is the longest record in Linkin Park's discography, makes the whole project blur together into a dragging near 50 minute long ordeal.

Mix: 8/10

Lyrics: 6/10

Instruments: 7/10

Vibes: 5/10

Total: 6/10

Total Score: 4/10

2 notes

·

View notes