#Julia Steinberg

Text

By: Julia Steinberg

Published: Jul 27, 2023

“California is America, only sooner” was an optimistic phrase once used to describe my home state. The Golden State promised a spirit of freedom, innovation, and experimentation that would spread across the nation. And at the heart of the state’s flourishing was a four-letter word: math.

Math made California prosper.

It’s most obvious in top universities like Stanford, Caltech, Berkeley, and UCLA. Those schools funneled great minds into California STEM enterprises like Silicon Valley, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and aeronautical engineering. Both the Central Valley and Hollywood—America’s main providers of food and fodder, respectively—rely upon engineering to mechanize production and optimize output.

All of this has made California’s GDP $3.6 trillion—making it the fifth largest economy in the world as of last year.

But now “California is America, only sooner” is a warning, and not just because of the exodus of people and jobs and the decay of our major cities, but because of the state’s abandonment of math—which is to say its abandonment of excellence and, in a way, reality itself.

Perhaps you’ve read the headlines about kooky San Francisco discarding algebra in the name of anti-racism. Now imagine that worldview adopted by the entire state.

On July 12, that’s what happened when California’s Board of Education, composed of eleven teachers, bureaucrats, professors—and a student—decided to approve the California Mathematics Framework.

Technically, the CMF is just a series of recommendations. As a practical matter, it’s the new reality. School districts and textbook manufacturers are already adapting to the new standards.

Here are some of them:

Most students won’t learn algebra until high school. In the past, when that was expected of middle schoolers, the CMF tells us, “success for many students was undermined.”

This means calculus will mostly be verboten, because students can’t take calculus “unless they have taken a high school algebra course or Mathematics I in middle school.”

“Detracking” (ending advanced courses) will be the law of the land until high school; students will be urged to “take the same rich mathematics courses in kindergarten through eighth grade.”

Lessons will foreground “equity” at the expense of teaching math basics like addition and subtraction. “Under the framework, the range of student backgrounds, learning differences, and perspectives, taken collectively, are seen as an instructional asset that can be used to launch and support all students in a deep and shared exploration of the same context and open task,” the CMF continues. It adds that “learning is not just a matter of gaining new knowledge—it is also about growth and identity development.”

Letter grades will be discouraged in favor of “standards-based assessments.” (It’s unclear what those are.)

Never mind that before California lowered its standards, the United States already ranked far behind the best-performing countries in math—places like Singapore, China, Estonia, and Slovenia. All those countries teach high school students calculus and, in some cases, more advanced linear algebra. (If we’re really in the midst of a cold war with China, we sure aren’t acting like it.)

The California Board of Education thinks the CMF is exactly what’s needed. That’s because the board has a fundamentally different approach to education—and it’s important that all Californians, indeed, all Americans, understand that.

The board’s overriding concern is not education or mathematical excellence, but minimizing racial inequity. Since a disproportionate number of white and Asian kids perform at the high end of the mathematics spectrum, and a disproportionate number of black and Latino children are at the bottom end, the board was left with two options: pull the bottom performers up, or push the top performers down. They did the easier thing.

In case anyone is wondering whether this works, whether it actually achieves greater racial equity, we need only look to San Francisco, which adopted CMF proposals like detracking before the CMF formally did.

“I want to be very clear on one fact that is based in our data: our current approach to math in SFUSD is not working,” San Francisco Unified School District Superintendent Matt Wayne said. “That is a tragedy, because we want to do right by our students. And we’re not meeting our goals around math. And particularly our students, especially black and brown students, are not benefiting from the current way we do math in the district.”

I emailed Jo Boaler, a Stanford education professor, one of the CMF’s authors, and a co-founder of youcubed, a center at Stanford that has pioneered ideas about equity and math education that figure prominently in the plan. I wanted to know what I was missing. What Matt Wayne was missing.

Boaler replied that she didn’t have much to say about the CMF and that she was a “small cog in the system that produced the framework.”

When I pressed her to see if she could offer any thoughts about the ideas behind the CMF—ideas she’s well versed in—she suggested I speak with “lead writer” Brian Lindaman, a math education professor at Chico State. Lindaman did not reply to my email.

Eventually, I did manage to speak with Kyndall Brown, the executive director of UCLA’s California Mathematics Project, which is charged with implementing the CMF.

I started by saying the CMF is clearly focused on racial inequity—noting, for example, that Chapter 2 is all about equity and that it’s shot through with mentions of racial “disparities” and “gaps” when it comes to “student outcomes.”

Brown, who, like other CMF supporters, believes those disparities are largely, if not entirely, the fault of racially or culturally insensitive teaching methods, replied simply: “Do you know how racist that sounds?”

When I asked him what, exactly, was racist about that, he replied: “What mathematicians of color did you learn about as a student? What female mathematicians did you learn about?” (He appeared to be alluding to medieval Arab contributions to the fields of algebra and number theory—which are fascinating and important when studying the history of ideas, but not obviously germane when teaching ninth graders about quadratic equations.)

The thing is, the CMF will exacerbate racial inequities. I went to a private school in Los Angeles filled with white and Asian students, and I know exactly how those kids—and definitely their parents—would react if they were told they could no longer take advanced math. They would enroll in rigorous programs outside school, like the Russian School of Mathematics, that would push them way beyond wherever their peers are. By the time college applications came along, the racial gap would be more like a yawning chasm.

I turned to Alan Schoenfeld, a Berkeley education professor who advised members of the Board of Education on the CMF, to see what he thought about this, and he said the same thing opponents of affirmative action have—that lower-performing students might perform better and develop greater confidence if they’re in a less rigorous environment. “Now some of them are going to turn out to enjoy mathematics, and they’re going to pursue mathematical careers,” Schoenfeld told me.

Ian Rowe, a CMF critic best known for founding several independent schools in the Bronx, said of the plan’s supporters: “They’ve embraced this ideology of oppressor-oppressed framework, where it’s assumed that black kids are these marginalized, oppressed human beings, and white kids are somehow the privileged oppressors. You see this all across the country, where expectations are being lowered in the name of equity by teachers and principals to somehow level the playing field.”

Let’s be clear: the CMF is racism pretending to be progressive, and all the fancy ed speak—about “frameworks” and “detracking” and “identity development”—can’t obscure as much. Indeed, the ideological gap is basically nonexistent between CMF supporters and reactionaries who once thought black and Latino kids were cognitively or culturally incapable of advanced mathematics.

We should be blaring this from the rooftops and on our social media feeds, over and over—lest we lose the California Dream, a.k.a. the American Dream, which once made this place so special.

==

Kids can't fail math if you don't teach it to them.

"Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes."

-- Rob Henderson

#Julia Steinberg#neoracism#woke racism#math#woke math#mathematics#corruption of education#luxury beliefs#time to homeschool#homeschool your kids#antiracism as religion#antiracism#equity#bigotry of low expectations#low expectations#religion is a mental illness

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyper-fixations of the month!

#silver jewelry#sofia steinberg#leeloo#fifth element#milla jovovich#black ballerina#taylor russell#julia garner#julia garner ozark#steve mcqueen#the thomas crown affair#moodboard#waif#coquette#waifspo#movie#tv#fashion#YSL#i am hyperfixating#June

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Speaking of France ...

Speaking of France …

You’re not supposed to begin a piece of writing with a question. Why not?

No idea, except that the “experts” seem to think that it’s an easy way out. “You can do better,” they say.

So what was my question? Oh yes.

Why is traditional French food so terribly unpopular at the moment?

Many authors and pundits have addressed that question in recent years, from Michael Steinberger’s Au Revoir to All…

View On WordPress

#clafoutis#Edward Behr#Eric Ripert#France#French cuisine#Haute Cuisine#Henri Soulé#James Hemings#Julia Child#Karen hess#Le Pavillon#Michael Steinberger#Michelin stars#Paul Freedman#The Virginia Housewife#Thomas Jefferson

0 notes

Text

I keep saying over and over "read Robin Wall Kimmerer, Julia Steinberger, and Kate Raworth." And then everyone's like "okay whatever." And everyone goes back to reading Dworkin and Simone de Beauvoir and whatnot.

That's fine I guess. But there's some important time sensitive information and knowledge tools that every woman needs. Put Robin Wall Kimmerer, Julia Steinberger, and Kate Raworth at the top of your reading list. Read through their work and make sure you understand it. And then you can go back to reading whatever it is you were reading before.

We need women to take power and lead. So we need women to understand how the future is going to work. Unsustainable male systems are collapsing all around us. Men want to fill post-collapse power vacuums with progressively more desperate, violent, and unsustainable systems. To prevent that from happening, women need to fill power vacuums with sustainable systems. And if you want to understand sustainable systems, you need to read Robin Wall Kimmerer, Julia Steinberger, and Kate Raworth.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

by Julia Steinberg

Within the first minute of scrolling under a search for “Zionism” on TikTok, I saw a “Zionism Explained” video with over 125,000 views. It said that Jews are forbidden by God to have their own state, completely ignoring the fact that the State of Israel is secular. “How did this start? Let’s go back to 1897,” the video instructs. But Jewish history in Israel started thousands of years ago, not in 1897.

When I searched “history” on TikTok, a woman with the “cute freckles and lashes” filter told me and over 80,000 viewers that, in “the biggest plot twist of the century,” Jews are using their ancestors’ “tragedy to justify and inflict another Holocaust.”

That explainer video is why, when I went to a pro-Palestine rally at Stanford on Wednesday and asked a fellow student what she meant when she chanted “from the river to the sea,” she said that, after admitting she wasn’t knowledgeable about the issue, Palestine must be free from the Tigris River (in Iraq) to the Black Sea (north of Turkey). This student, though she has no sense of geography, is actually chanting for the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea to no longer contain the state of Israel. It is an eliminationist slogan.

I saw a similar message at an off-campus café recently when I walked by a girl whose laptop bore a newly applied sticker with the words “By Any Means Necessary” stamped over an outline of Israel. It’s been less than three weeks since October 7 and already these glib stickers plugging genocide, aimed at my generation, are proliferating.

A new axis of evil—Big Tech, social media companies, and China—has taken the once-fringe position that Jews are undeserving of a homeland, and is now pushing the idea of their mass slaughter via shoddy animation and beautiful women hosting “explainer” videos. And it’s trickling down onto t-shirts and “cute” laptop stickers.

It’s cool to promote hate.

My Jewish parents, whose hearts break to hear about what I go through at college, did everything they could so that my brother and I would reject this simplistic, horrible way of thinking. But they can’t change that my little brother’s high school also teaches ideology with T-charts. I doubt his teachers or classmates care to understand that no T-chart can account for why he and his Jewish friends feel sick when they see slogans calling for their deaths.

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to address a problem that seems to arise repeatedly in public discussions about green growth and degrowth. Some prominent commentators seem to assume that the debate here is primarily about the question of technology, with green growth promoting technological solutions to the ecological crisis while degrowth promotes only economic and social solutions (and in the most egregious misrepresentations is cast as “anti-technology”). This narrative is inaccurate, and even a cursory review of the literature is enough to make this clear. In fact, degrowth scholarship embraces technological change and efficiency improvements, to the extent (crucially) that these are empirically feasible, ecologically coherent, and socially just. But it also recognizes that this alone will not be enough: economic and social transformations are also necessary, including a transition out of capitalism. The debate is therefore not primarily about technology, but about science, justice, and the structure of the economic system.

[...]

Ecological economists point out that when we scale back our assumptions about technological change to levels that are, to quote the physicist and ecological economist Julia Steinberger, “non-insane,” and when we reject the idea that growth in rich countries should be maintained at the expense of the Global South, it becomes clear that relying on technological change is not enough, in and of itself, to solve the ecological crisis. Yes, we need fast renewable energy deployment, efficiency improvements, and dissemination of advanced technology (induction stoves, efficient appliances, heat pumps, electric trains, and so on). But we also need high-income countries dramatically to reduce aggregate energy and material use, at a speed faster than what efficiency improvements alone could possibly hope to deliver. To achieve this, high-income countries need to abandon growth as an objective and actively scale down less necessary forms of production, to reduce excess energy and material use directly.

[...]

Degrowth does not call for all forms of production to be reduced. Rather, it calls for reducing ecologically destructive and socially less necessary forms of production, like sport utility vehicles, private jets, mansions, fast fashion, arms, industrial beef, cruises, commercial air travel, etc., while cutting advertising, extending product lifespans (banning planned obsolescence and introducing mandatory long-term warranties and rights to repair), and dramatically reducing the purchasing power of the rich. In other words, it targets forms of production that are organized mostly around capital accumulation and elite consumption. In the middle of an ecological emergency, should we be producing sport utility vehicles and mansions? Should we be diverting energy to support the obscene consumption and accumulation of the ruling class? No. That is an irrationality that only capitalism can love.

At the same time, degrowth scholarship insists on strong social policy to secure human needs and well-being, with universal public services, living wages, a public job guarantee, working time reduction, economic democracy, and radically reduced inequality. These measures abolish unemployment and economic insecurity and ensure the material conditions for a universal decent living—again, basic socialist principles. This scholarship calls for efficiency improvements, yes, but also a transition toward sufficiency, equity, and a democratic postcapitalist economy, where production is organized around well-being for all, as Peter Kropotkin famously put it, rather than around capital accumulation.

The virtue of this approach should be immediately clear to socialists. Socialism insists on grounding its analysis in the material reality of the world economy. It insists on science and justice. Yes, socialism embraces technology—and credibly promises to manage technology better than capitalism—but socialist visions of technology should be empirically grounded, ecologically coherent, and socially just. They should emphatically not rely on speculation or magical thinking, much less the perpetuation of colonial inequalities. Green growth visions fall foul of these core socialist values.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hell no we are not letting this OFMD finale distract from that THIS LETTER.

Had a signature from Taika Waititi. I understand the sensitivity here this issue with Taika being Jewish(and that’s not my place as someone that’s Not Jewish or in those regions to condemn him on that perspective’s behalf) but this letter is directly bastardizing the situation.

Now, when there is a major production from a major figure in this platform that did this, is when we can make the most impact. Remember our values, even when those values involve a show that is strengthening the LGBTQ community.

Because this letter tore down the strength of the movement in support of Gaza. There are going to be so many people that saw this letter and take it completely uncritically, unchallenged.

Standing up for our values means sacrificing our interests, holding accountable the things we enjoy.

And also. I don’t want to see ANYONE. Being fucking antisemitic or racist towards Taika here. That is never appropriate and absolutely inexcusable behavior. You should he ashamed if you think that’s okay even after Taika’s actions.

[Text of Letter]

October 23, 2023

Dear President Biden, We are heartened by Friday's release of the two American hostages, Judith Ranaan and her daughter Natalie Ranaan and by today's release of two Israelis, Nurit Cooper and

Yocheved Lifshitz, whose husbands remain in captivity. But our relief is tempered by our overwhelming concern that 220 innocent people,

including 30 children, remain captive by terrorists, threatened with torture and death.

They were taken by Hamas in the savage massacre of October 7, where over 1,400

Israelis were slaughtered - women raped, families burned alive, and infants beheaded. Thank you for your unshakable moral conviction, leadership, and support for the Jewish people, who have been terrorized by Hamas since the group's founding over 35 years ago, and for the Palestinians, who have also been terrorized, oppressed, and victimized

by Hamas for the last 17 years that the group has been governing Gaza. We all want the same thing: Freedom for Israelis and Palestinians to live side by side in peace. Freedom from the brutal violence spread by Hamas. And most urgently, in this

moment, freedom for the hostages. We urge everyone to not rest until all hostages are released. No hostage can be left behind. Whether American, Argentinian, Australian, Azerbaijani, Brazilian, British, Canadian, Chilean, Chinese, Danish, Dutch, Eritrean, Filipino, French, German, Indian, Israeli, Italian, Kazakh, Mexican, Panamanian, Paraguayan, Peruvian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, South African, Spanish, Sri Lankan, Thai, Ukrainian,

Uzbekistani or otherwise, we need to bring them home.

Sincerely,

[Text of the names presented. This isn’t all of them, just the copy of this with Taika’s name on it)

Jessica Biel

Jessica Elbaum

Jessica Seinfeld

Jill Littman

Jimmy Carr

Jody Gerson

Joe Hipps

Joe Quinn

Joe Russo

Joe Tippett

Joel Fields

Joey King

John Landgraf

John Slattery

Jon Bernthal

Jon Glickman

Jon Hamm

Jon Harmon Feldman

Jon Liebman

Jon Watts

Jon Weinbach

Jonathan Baruch

Jonathan Groff

Jonathan Marc Sherman

Jonathan Ross

Jonathan Steinberg

Jonathan Tisch

Jonathan Tropper

Jordan Peele

Josh Brolin

Josh Charles

Josh Dallas

Josh Goldstine

Josh Greenstein

Josh Grode

Josh Singer

Judd Apatow

Judge Judy Sheindlin

Julia Fox

Julia Garner

Julia Lester

Julianna Margulies

Julie Greenwald

Julie Rudd

Julie Singer

Juliette Lewis

Jullian Morris

Justin Theroux

Justin Timberlake

KJ Steinberg

Karen Pollock

Karlie Kloss

Katy Perry

Kelley Lynch

Kevin Kane

Kevin Zegers

Kirsten Dunst

Kitao Sakurai

Kristen Schaal

Kristin Chenoweth

Lana Del Rey

Laura Benanti

Laura Dern

Laura Pradelska

Lauren Schuker Blum

Laurence Mark

Laurie David

Lea Michele

Lee Eisenberg

Leo Pearlman

Leslie Siebert

Liev Schreiber

Limor Gott

Lina Esco

Liz Garbus

Lizanne Rosenstein

Lizzie Tisch

Lorraine Schwartz

Lynn Harris

Lyor Cohen

Madonna

Mandana Dayani

Mara Buxbaum

Marc Webb

Marco Perego

Maria Dizzia

Mark Feuerstein

Mark Foster

Mark Scheinberg

Mark Shedletsky

Martin Short

Mary Elizabeth Winstead

Mary McCormack

Mathew Rosengart

Matt Geller

Matt Lucas

Matt Miller

Matthew Bronfman

Matthew Hiltzik

Matthew Weiner

Matti Leshem

Max Mutchnik

Maya Lasry

Meaghan Oppenheimer

Melissa Zukerman

Melissa rudderman

Michael Aloni

Michael Ellenberg

Michael Green

Michael Rapino

Neil Blair

Neil Druckmann

Neil Paris

Nicola Peltz

Nicole Avant

Nina Jacobson

Noa Kirel

Noa Tishby

Noah Oppenheim

Noah Schnapp

Noreena Hertz

Octavia Spencer

Odeya Rush

Olivia Wilde

Oran Zegman

Orlando Bloom

Pasha Kovalev

Pattie LuPone

Patty Jenkins

Paul Haas

Paul Pflug

Paul & Julie Rudd

Peter Baynham

Peter Traugott

Rachel Douglas

Rachel Riley

Rafi Marmor

Ram Bergman

Raphael Margulies

Rebecca Angelo

Rebecca Mall

Regina Spektor

Reinaldo Marcus Green

Rich Statter

Richard Jenkins

Richard Kind

Rick Hoffman

Rick Rosen

Rita Ora

Rob Rinder

Robert Newman

Roger Birnbaum

Roger Green

Rosie O’Donnell

Ross Duffer

Ryan Feldman

Sacha Baron Cohen

Sam Levinson

Sam Trammell

Sara Berman

Sara Foster

Sarah Baker

Sarah Bremner

Sarah Cooper

Sarah Paulson

Sarah Treem

Scott Braun

Scott Braun

Scott Neustadter

Scott Tenley

Sean Combs

Sean Levy

Seth Meyers

Seth Oster

Shannon Watts

Shari Redstone

Sharon Jackson

Sharon Stone

Shauna Perlman

Shawn Levy

Sheila Nevins

Shira Haas

Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Tikhman

Skylar Astin

Stacey Snider

Stephen Fry

Steve Agee

Steve Rifkind

Sting & Trudie Styler

Susanna Felleman

Susie Arons

Taika Waititi

Thomas Kail

Tiffany Haddish

Todd Lieberman

Todd Moscowitz

Todd Waldman

Tom Freston

Tom Werner

Tomer Capone

Tracy Ann Oberman

Trudie Styler

Tyler Henry

Tyler James Williams

Tyler Perry

Vanessa Bayer

Veronica Grazer

Veronica Smiley

Whitney Wolfe Herd

Will Ferrell

Will Graham

Yamanieka Saunders

Yariv Milchan

Ynon Kreiz

Zack Snyder

Zoe Saldana

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Olivia Rosane

Common Dreams

May 15, 2023

More than 1,000 scientists and academics in over 21 countries engaged in nonviolent protest last week under the banner of Scientist Rebellion to demand a just and equitable end to the fossil fuel era.

At least 19 of the participating scientists were arrested in actions linked to the group's "The Science Is Clear" campaign from May 7-13, organizers said at a Monday press conference. The group believes that researchers must move from informing to advocating in the wake of decades of fossil fuel industry disinformation about the climate crisis and the downplaying or ignoring of their warnings by governments and media organizations.

"It's urgent that scientists come out of their laboratories to counter the lies," Laurent Husson, a French geoscientist from ISTerre, said.

"Experts on tropical rainforests told me privately that they think the Amazon has already passed its tipping point. Let that sink in. The world needs to know."

Participating scientists in Africa, Australia, Europe, Latin America, and North America organized more than 30 discrete events during May's spate of actions. Scientific Rebellion is concerned that climate policy is not in line with official warnings like the final Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report of the decade, released earlier this year, which called for "rapid and deep and, in most cases, immediate" reductions in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 in its "Summary for Policymakers."

However, some scientist-activists say that what researchers discuss internally is even more alarming.

"I was just at a NASA team meeting for three days in D.C.," Peter Kalmus tweeted Wednesday. "The scientific findings are so fucked up. Experts on tropical rainforests told me privately that they think the Amazon has already passed its tipping point. Let that sink in. The world needs to know."

The Science Is Clear campaign had three clear demands: that governments rapidly decarbonize their infrastructure in coordination with citizens assemblies that would also address growing inequality, that the Global North both provide money to the Global South to help them pay for the inevitable loss and damage caused by the climate crisis and forgive their outstanding debt, and that ecosystems and the Indigenous people and local communities that depend on them be protected from extractive industries.

Local actions also had independent demands in line with these goals. For example, Rose Abramoff—a U.S.-based scientist and IPCC reviewer—helped disrupt a joint session of the Massachusetts Legislature Wednesday with the demands that Massachusetts ban all new fossil fuel infrastructure and fund a just transition to renewable energy. The activists, who also included members of Extinction Rebellion, occupied the House Gallery for six hours before they were arrested.

Abramoff said at the press conference that she joined Scientific Rebellion when the data turned up by her field work grew too alarming.

"This can't be my job to just calmly document destruction without doing anything to prevent it," she said.

She has now been arrested six times including Wednesday. And while she was fired from one job, she remains employed, housed, and healthy with a clean record.

"I think more scientists and other people with privilege should be taking these measures," she said.

Janine O'Keefe, an engineer and economist, said she was treated with much more respect by police when she protested in a lab coat compared with when she didn't, and was often not arrested at all.

"I implore you to find the courage to go against the silence," she said.

IPCC author Julia Steinberger also said she felt activism was part of a scientist's duty.

"It is us doing our jobs and holding our government to account on the commitments they have made to protect us."

"It is us doing our jobs and holding our government to account on the commitments they have made to protect us," Steinberger said.

Several other scientists risked arrest alongside allied activists in direct actions throughout the week. Three scientists were arrested for protesting Equinor in Norway. In Italy, police stopped activists before they could begin a protest at Turin Airport and arrested all of the would-be participants. In Denmark, five scientists were arrested at protests alongside more than 100 other activists, and in Portugal, scientists and allies managed to block the Porto de Sines—the main entry point for fossil fuels into the country—without any arrests being made.

In France, meanwhile, police arrested 18 activists including five scientists for blocking a bridge in the Port of Le Havre Friday, near where TotalEnergies is building a floating methane terminal for imported liquefied natural gas.

Tanakula, who helped organize marches and spoke to staff and students at her university, pointed out that Africa had only contributed less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions but was on the "frontline" of their impacts, such as extreme flooding May 5 that killed more than 400 people.

"We can't just be observers or do research. We need to engage people, and we need to act in the name of science," Tanakula said.

Scientific Rebellion doesn't just focus on the climate crisis. The Science Is Clear webpage notes that human activity has overshot six of nine planetary boundaries that sustain life on Earth, and that—beyond just the fossil fuel industry—the entire current economic system is to blame.

"The underlying cause of this existential crisis is our growth-based economic system," Matthias Schmelzer, a postdoctoral researcher at the Friedrich-Schiller University in Jena, Germany, said in the press conference.

"The underlying cause of this existential crisis is our growth-based economic system."

More than 1,100 scientists and academics have signed a letter urging both public and private institutions to pursue degrowth—a planned and democratic realignment of the goal of the global economy from increasing gross domestic product to ensuring well-being within planetary boundaries.

Members of Scientific Rebellion expressed optimism that direct action could help push through the changes it seeks. Abramoff pointed to Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport, which banned private jets months after activists blocked them from taking off. She also argued that two major pieces of U.S. climate legislation—the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan infrastructure law—would not have passed without grassroots pressure.

"I feel that we have so much power," Abramoff said, "and we just have to be brave enough to use it."

Read more.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

full list of biden letter 2:

Aaron Bay-Schuck

Aaron Sorkin

Adam & Jackie Sandler

Adam Goodman

Adam Levine

Alan Grubman

Alex Aja

Alex Edelman

Alexandra Shiva

Ali Wentworth

Alison Statter

Allan Loeb

Alona Tal

Amy Chozick

Amy Pascal

Amy Schumer

Amy Sherman Palladino

Andrew Singer

Andy Cohen

Angela Robinson

Anthony Russo

Antonio Campos

Ari Dayan

Ari Greenburg

Arik Kneller

Aron Coleite

Ashley Levinson

Asif Satchu

Aubrey Plaza

Barbara Hershey

Barry Diller

Barry Levinson

Barry Rosenstein

Beau Flynn

Behati Prinsloo

Bella Thorne

Ben Stiller

Ben Turner

Ben Winston

Ben Younger

Billy Crystal

Blair Kohan

Bob Odenkirk

Bobbi Brown

Bobby Kotick

Brad Falchuk

Brad Slater

Bradley Cooper

Bradley Fischer

Brett Gelman

Brian Grazer

Bridget Everett

Brooke Shields

Bruna Papandrea

Cameron Curtis

Casey Neistat

Cazzie David

Charles Roven

Chelsea Handler

Chloe Fineman

Chris Fischer

Chris Jericho

Chris Rock

Christian Carino

Cindi Berger

Claire Coffee

Colleen Camp

Constance Wu

Courteney Cox

Craig Silverstein

Dame Maureen Lipman

Dan Aloni

Dan Rosenweig

Dana Goldberg

Dana Klein

Daniel Palladino

Danielle Bernstein

Danny Cohen

Danny Strong

Daphne Kastner

David Alan Grier

David Baddiel

David Bernad

David Chang

David Ellison

David Geffen

David Gilmour &

David Goodman

David Joseph

David Kohan

David Lowery

David Oyelowo

David Schwimmer

Dawn Porter

Dean Cain

Deborah Lee Furness

Deborah Snyder

Debra Messing

Diane Von Furstenberg

Donny Deutsch

Doug Liman

Douglas Chabbott

Eddy Kitsis

Edgar Ramirez

Eli Roth

Elisabeth Shue

Elizabeth Himelstein

Embeth Davidtz

Emma Seligman

Emmanuelle Chriqui

Eric Andre

Erik Feig

Erin Foster

Eugene Levy

Evan Jonigkeit

Evan Winiker

Ewan McGregor

Francis Benhamou

Francis Lawrence

Fred Raskin

Gabe Turner

Gail Berman

Gal Gadot

Gary Barber

Gene Stupinski

Genevieve Angelson

Gideon Raff

Gina Gershon

Grant Singer

Greg Berlanti

Guy Nattiv

Guy Oseary

Gwyneth Paltrow

Hannah Fidell

Hannah Graf

Harlan Coben

Harold Brown

Harvey Keitel

Henrietta Conrad

Henry Winkler

Holland Taylor

Howard Gordon

Iain Morris

Imran Ahmed

Inbar Lavi

Isla Fisher

Jack Black

Jackie Sandler

Jake Graf

Jake Kasdan

James Brolin

James Corden

Jamie Ray Newman

Jaron Varsano

Jason Biggs & Jenny Mollen Biggs

Jason Blum

Jason Fuchs

Jason Reitman

Jason Segel

Jason Sudeikis

JD Lifshitz

Jeff Goldblum

Jeff Rake

Jen Joel

Jeremy Piven

Jerry Seinfeld

Jesse Itzler

Jesse Plemons

Jesse Sisgold

Jessica Biel

Jessica Elbaum

Jessica Seinfeld

Jill Littman

Jimmy Carr

Jody Gerson

Joe Hipps

Joe Quinn

Joe Russo

Joe Tippett

Joel Fields

Joey King

John Landgraf

John Slattery

Jon Bernthal

Jon Glickman

Jon Hamm

Jon Liebman

Jonathan Baruch

Jonathan Groff

Jonathan Marc Sherman

Jonathan Ross

Jonathan Steinberg

Jonathan Tisch

Jonathan Tropper

Jordan Peele

Josh Brolin

Josh Charles

Josh Goldstine

Josh Greenstein

Josh Grode

Judd Apatow

Judge Judy Sheindlin

Julia Garner

Julia Lester

Julianna Margulies

Julie Greenwald

Julie Rudd

Juliette Lewis

Justin Theroux

Justin Timberlake

Karen Pollock

Karlie Kloss

Katy Perry

Kelley Lynch

Kevin Kane

Kevin Zegers

Kirsten Dunst

Kitao Sakurai

KJ Steinberg

Kristen Schaal

Kristin Chenoweth

Lana Del Rey

Laura Dern

Laura Pradelska

Lauren Schuker Blum

Laurence Mark

Laurie David

Lea Michele

Lee Eisenberg

Leo Pearlman

Leslie Siebert

Liev Schreiber

Limor Gott

Lina Esco

Liz Garbus

Lizanne Rosenstein

Lizzie Tisch

Lorraine Schwartz

Lynn Harris

Lyor Cohen

Madonna

Mandana Dayani

Mara Buxbaum

Marc Webb

Marco Perego

Maria Dizzia

Mark Feuerstein

Mark Foster

Mark Scheinberg

Mark Shedletsky

Martin Short

Mary Elizabeth Winstead

Mathew Rosengart

Matt Lucas

Matt Miller

Matthew Bronfman

Matthew Hiltzik

Matthew Weiner

Matti Leshem

Max Mutchnik

Maya Lasry

Meaghan Oppenheimer

Melissa Zukerman

Michael Aloni

Michael Ellenberg

Michael Green

Michael Rapino

Michael Rappaport

Michael Weber

Michelle Williams

Mike Medavoy

Mila Kunis

Mimi Leder

Modi Wiczyk

Molly Shannon

Nancy Josephson

Natasha Leggero

Neil Blair

Neil Druckmann

Nicola Peltz

Nicole Avant

Nina Jacobson

Noa Kirel

Noa Tishby

Noah Oppenheim

Noah Schnapp

Noreena Hertz

Odeya Rush

Olivia Wilde

Oran Zegman

Orlando Bloom

Pasha Kovalev

Pattie LuPone

Paul & Julie Rudd

Paul Haas

Paul Pflug

Peter Traugott

Polly Sampson

Rachel Riley

Rafi Marmor

Ram Bergman

Raphael Margulies

Rebecca Angelo

Rebecca Mall

Regina Spektor

Reinaldo Marcus Green

Rich Statter

Richard Jenkins

Richard Kind

Rick Hoffman

Rick Rosen

Rita Ora

Rob Rinder

Robert Newman

Roger Birnbaum

Roger Green

Rosie O’Donnell

Ross Duffer

Ryan Feldman

Sacha Baron Cohen

Sam Levinson

Sam Trammell

Sara Foster

Sarah Baker

Sarah Bremner

Sarah Cooper

Sarah Paulson

Sarah Treem

Scott Braun

Scott Braun

Scott Neustadter

Scott Tenley

Sean Combs

Seth Meyers

Seth Oster

Shannon Watts

Shari Redstone

Sharon Jackson

Sharon Stone

Shauna Perlman

Shawn Levy

Sheila Nevins

Shira Haas

Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Tikhman

Skylar Astin

Stacey Snider

Stephen Fry

Steve Agee

Steve Rifkind

Sting & Trudie Styler

Susanna Felleman

Susie Arons

Taika Waititi

Thomas Kail

Tiffany Haddish

Todd Lieberman

Todd Moscowitz

Todd Waldman

Tom Freston

Tom Werner

Tomer Capone

Tracy Ann Oberman

Trudie Styler

Tyler James Williams

Tyler Perry

Vanessa Bayer

Veronica Grazer

Veronica Smiley

Whitney Wolfe Herd

Will Ferrell

Will Graham

Yamanieka Saunders

Yariv Milchan

Ynon Kreiz

Zack Snyder

Zoe Saldana

Zoey Deutch

Zosia Mamet

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ninth International Degrowth Conference, held in August this year in Zagreb, Croatia, opens with a provocation. Keynote speaker Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, the newly elected vice chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), has two requests to make of the audience. The first is to figure out how to coordinate with governments of all stripes, since the climate crisis requires global unity.

The second? “Maybe consider a different word.”

It’s about as close to blasphemy as this niche, academic, and politically radical conference can get.

To a rising minority of European leftists, the term “degrowth” is proving an attraction rather than a turnoff. The protean climate movement that exists under its banner is gaining momentum among academics, youth activists, and, increasingly, policymakers across the continent.

The European Parliament hosted its second (and terminologically defanged) Beyond Growth Conference just this past May, this time with unprecedented buy-in from elected officials; as organizer and European Parliament member Philippe Lamberts (of the Belgian Greens) told the Financial Times, the “big shots” are now “playing ball.”

Those in Zagreb frame the Brussels push as “extraordinary” and “major,” with the parliament building “filled to the brim” by a new swell of activists, nongovernmental organizations, academics, and elected officials totaling some 7,000 strong. Julia Steinberger, a longtime researcher of the social and economic impacts of climate change at the University of Lausanne, adds: “And they were young.”

This energy carries over to the degrowth circuit proper, which multiple veterans tell me has long outgrown its humble beginnings. At a watershed, self-organized gathering in Leipzig, Germany in 2014, ragtag participants made their own meals. This year’s conference, by contrast, is co-sponsored by the city of Zagreb, attended by the mayor and representatives of the IPCC, and professionally catered with vegan canapés.

With its deepest roots in direct democracy and anti-capitalism, the degrowth movement is bent on challenging the central tenet of postwar economics: that further increases in GDP—strongly correlated with increases in carbon emissions—translate to further advances in social and individual well-being.

The implications of the critique extend far beyond the usual calls for countries to reach net-zero emissions targets. To degrowthers, the climate crisis is a social problem, and addressing it will require no less than reengineering the entire global, socioeconomic order, especially in the wealthy global north.

Why the sudden interest in this radical program? Why Europe, and why now?

Perhaps the answer should be obvious: Late August 2023, when the Zagreb event convenes, caps off the hottest global summer ever recorded. The defining characteristic of degrowth’s latest influx of followers, as the movement’s major figures will stress to me again and again over the next four days, is youth—which is to say, a heightened vulnerability to the future effects of climate change.

The status quo has left these young supporters disillusioned and alarmed. And no wonder. When, during her keynote address, Ürge-Vorsatz draws up a heat map showing the proportion of the Earth that will become unsuitable for human life by 2070 under business-as-usual projections, no one bats an eye; it’s data that this particular audience has seen before.

The suggestion to “find a better word,” however, is met with an affronted laugh. For Europe’s young people, degrowth isn’t just a utopian slogan, but an intentionally provocative, environmental necessity—and an existing reality.

Parallel to these radical calls to abandon economic growth as a policy goal, many economists have observed that capitalism in developed countries is already slowing down, seemingly of its own accord, and very much against the mainstream political will. The trend is called (in a manner that hardly satisfies Ürge-Vorsatz’s invitation to find a more appealing term) “secular stagnation,” and it predicts that in highly developed economies, a near future of stagnant growth is more or less inevitable.

This slowdown in the year-over-year growth of GDP per capita is detectible in wealthy industrialized countries such as Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, according to economists such as Dietrich Vollrath, whose book Fully Grown describes this phenomenon.

The deceleration is accompanied by a rise in inequality, which contributes to increased polarization on both the left and the right. Poorly managed energy transitions and climate-induced disasters are poised to exacerbate the trend. So are declining fertility rates, which lead to a lopsided age distribution in the workforce, putting further strain on welfare systems. While it is tempting to ascribe the decline in birth rates primarily to the rising cost of having children in rich countries, in the EU, generous benefits to parents (Hungary, for example, recently waived personal income tax for mothers under 30, among other pro-family measures) have failed to turn the tide. At a certain point, wealthy societies in advanced stages of modern capitalism no longer want to grow.

As a consequence, for the first time since the mid-20th-century, young people from the world’s richest nations, such as those gathered here in Zagreb, cannot expect to be better off than their parents.

The anxious backdrop is enough to make one wonder whether the uptick of interest in degrowth isn’t, in fact, just another symptom of a lack of economic growth in Europe, coupled with impending environmental degradation. It brings into focus a bigger historical picture, one of wealthy countries around the world struggling to manage ecological decline and rising domestic discontent when the usual remedy—rapid growth—may be as economically impossible as it is environmentally dubious.

If such degrowth is inevitable, degrowthers ask—if for a very different set of reasons—how can it best be managed?

And is it possible for Europe to greet it with anything other than anxiety and despair?

On the opening night of the International Degrowth Conference, at a reception held in the lobby of the Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, at least two surveys of the 680 registered participants are going around, gathering demographics in the name of ongoing academic research. The shoe-leather approach provides a good estimate: A quick turn though the crowd proves the attendees to be overwhelmingly white, youthful, and fit.

And yet, considerable diversity exists within that apparent uniformity. Degrowth is a big tent, one that attracts graduate students, activists, Marxists, feminists, decolonizationists, and in more recent years, elected politicians, all of them disillusioned with the promises of “green growth” inscribed in the EU Green Deal, or in the United States’ growth-oriented Inflation Reduction Act. It could be described as an academic field, an intellectual crossroads, a political movement—or better yet, given its versatile nature, as a cultural one.

The term decroissance first emerged in France during the resource debates of the 1970s, when the Club of Rome published its famous 1972 report, The Limits to Growth, which is still one of the most controversial and bestselling environmental books of all time. That study argued that exploding global population and resource use would exceed the Earth’s carrying capacity within one generation, resulting in a precipitous decline in welfare.

Strongly influenced by a natural scientist’s understanding of the conservation of energy (as opposed to an economist’s understanding of abstract and theoretically limitless variables, such as demand), the report popularized the enduring idea that there is no infinite growth on a finite planet. Kenneth Boulding, author of the essay “The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth,” echoed the concept in congressional testimony delivered during a discussion of the global ecological situation in 1973: “Anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.”

Predicting the future is a risky business. The Club of Rome report was—and still is—ridiculed by mainstream analysts, who pointed to the fact that the next generation became, au contraire, ever richer and more populous. Others rightly questioned the report’s tendency to stoke the West’s racist fears of population growth in the global south. From a purely ecological view, however, research from natural scientists continues to suggest that the 1972 study got more right than wrong; ecologists warn that we have now exceeded four of nine planetary boundaries that define a habitable planet.

Today’s iteration of degrowth, translated from the French, disavows these earlier debates’ Malthusian focus on population growth, instead shifting the emphasis to per capita consumption. This time, the culprit is decadence in the global north.

Embracing the ethos of anti-consumerism, anti-advertising, and decolonization, the idea of reorienting rich economies away from the hegemonic pursuit of GDP growth gained purchase in France and Southern Europe following the 2008-09 financial crisis—which was seen as yet another consequence of the reckless pursuit of growth—and the austerity measures that it drew into its wake.

Vincent Liegey, a French thinker, author, and organizer who was active in those earliest years of the degrowth movement, tells me that these days, degrowth might be best understood as a “tool,” one used “to question dominant paradigms and address 21st-century problems with [the idea of] well-being.”

There’s an academic flair to the accrual of terms and definitions in the conversations that I have over the next four days: “conviviality,” “frugal abundance,” and “well-being” are favored. (A primer from one of the movement’s foremost thinkers, George Kallis, bears the title Degrowth: Vocabulary for a New Era.) Marxism is more than ambient. But so are appeals for direct democracy and municipalism, as well as serious engagement from NGOs and members of the European Parliament.

It can be difficult to keep track of where the ideological accent lies. In their book The Future Is Degrowth, Matthias Schmelzer, Aaron Vansintjan, and Andrea Vetter helpfully break the movement down into different “currents,” of which there are two dominant schools: green-liberal economic reform, which relies on familiar tools (such as market mechanisms, taxation and regulation) to bring growth and institutions into accord with planetary boundaries; and “socialism without growth,” which focuses more on fundamental changes to distribution and ownership (and which distinguishes itself from the Marxist productivism practiced in Soviet Russia or Maoist China).

Natural scientists, too, supply working definitions. One of the most common (and politically neutral-sounding) goals repeated in Zagreb harkens back to a widely circulated 2020 Nature Communications paper titled “Scientists’ Warning on Affluence”: Drawing on economist Giorgos Kallis’s definition, the paper’s authors argue that degrowth aims for an “equitable downscaling of throughput (that is the energy and resource flows through an economy, strongly coupled to GDP), with a concomitant securing of well-being.”

“There’s always been an activist and an academic part of the movement,” the aforementioned Steinberger, a co-author of that paper, tells me. Though both factions have historically lacked traction with the broader public, 2023 may be the year this marginal status starts to change. Degrowth has made “giant steps forward” in “how we can articulate these ideas and how we can make them popular,” Steinberger says, pointing to the May conference in Brussels as an example.

Ürge-Vorsatz likewise welcomes the new momentum as a “really exciting development,” one further linked to recent degrowth-adjacent legislation such as a draft directive proposed in the European Parliament that would ban “planned obsolescence” and increase the durability of consumer goods.

There are further signs of momentum. The sixth IPCC assessment report, published last year, made its first mention of degrowth, citing the literature’s “key insight” that “pursuing climate goals … requires holistic thinking including on how to measure well-being,” and name-checking the movement’s “serious consideration of the notion of ecological limits.”

The writing of Japanese philosopher Kohei Saito, a rising international star (and also in attendance in Zagreb), has become a surprise hit in Japan and around the globe, with his 2020 book Capital in the Anthropocene grossing more than 500,000 copies; the week of the conference, he was profiled in the New York Times for his philosophy of “degrowth communism,” while a German translation had just appeared on the Der Spiegel bestseller list.

And it’s a kind of “cultural victory,” Liegey says, that policy magazines such as the Economist and the Financial Times, not to mention the present publication, have also begun to engage—even if only to debunk degrowth as a brewing economic disaster.

Pressed to explain the surge in interest, however, it’s notable that many organizers and researchers didn’t cite concrete proposals from degrowth’s own economic agenda, but rather the ruins of the old, postwar paradigm.

They cited record-breaking temperatures that have risen quite literally off the charts. They cited the pandemic, an experiment in rapid social transformation that has broadened the public imagination for what is possible in a narrow time frame. They cited, above all, the energy of the younger generation of activists heralding from Ende Gelände, Extinction Rebellion, Fridays for Future, and the many youth and graduate students who are getting involved in degrowth itself.

One such newcomer, here in Zagreb as a volunteer, tells me that she discovered degrowth after becoming disillusioned with green growth narratives and party politics in her native France. “I’m not sure how much is propaganda,” she says with a laugh, gesturing toward the cacophony of workshops and academic presentations taking place simultaneously in the conference center (the usual purpose of which, I’m told, is to host weddings; at least three can take place here at once). But she admits that she finds it “inspiring to see so many people working on solutions” after more mainstream channels left her pessimistic.

She is not the only person attracted to Europe’s degrowth movement by a combination of pessimism about the current conditions of the world and the promise of political solutions to quell that anxiety. But degrowth also raises the question of just how real these solutions are meant to be—or whether managing pessimism is the primary draw.

Asked to explain why the movement continues to enjoy more support in Europe as compared to other parts of the industrialized world, degrowthers point to the continent’s long tradition of leftist organizing and greater cultural openness to restraining the excesses of capitalism.

“There’s more freedom in Europe to question mainstream economics and the growth paradigm,” says Steinberger, who received her Ph.D. in physics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It’s not that it’s comfortable,” she adds, “but it’s at least … nobody’s going to [be] fired for it. It doesn’t generate the same sort of kneejerk revulsion.”

Saito, who studied in both the United States and Europe before returning to his native Tokyo, where he is now a professor of philosophy at Tokyo University, echoes the claim: “I think in some sense, EU countries already regulate this system of capitalism, creating other space for other things, for noncommercial activities. And that’s already half-degrowth.”

But there is, potentially, a broader cultural backdrop to the increased interest, especially among the young. Gwendoline Delbos-Corfield, a member of the European Parliament representing France (and the Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance parties), tells me that the youth she speaks with are notably pessimistic. “Girls tell me we shouldn’t be having children because it harms the planet,” she says.

Youthful (and hyperbolic) critiques of the status quo are hardly novel to European politics. But the current attitude feels distinct from the student protests that swept the continent in the 1960s: “I feel there is more despair,” Delbos-Corfield adds.

There’s always been an anti-materialist, anti-capitalist bent among green revolutionaries in the West, but degrowth should also be understood as separate from the back-to-the-land or hippie spiritualism that marked the environmentalism of the 1970s. The main drivers on display in Zagreb are economic and environmental anxiety as the world slips into very real ecological and civic unrest.

“They have a lot of access to depressive information,” Liegey says of the young people he sees joining and reshaping the movement, “and no way of acting on it.” Ürge-Vorsatz echoes his assessment. “If you just look at climate [policy] in Europe,” she says, “then I think we should be very positive because Europe has been doing great things.” On that front, there’s reason for optimism. But as for the broader political landscape, she notes that it often seems as if Europe is entering “into an era of crisis after crisis after crisis” that will require an updated political vision: “The only way we can actually manage crisis is to think for the long term.”

Charges of pessimism, alongside demands for continued economic development in the global south, are arguably where critics gain the most traction against degrowth. Self-described “techno-optimist” thinkers such as Andrew McAfee and Steven Pinker have more or less self-consciously pitted themselves against it. Regarding climate goals, these thinkers call for more growth, not less, and especially for the so-called decoupling of that growth from increased material resource use. Their self-described optimism stems from the fact that this decoupling is already taking place; they reckon it can be accelerated through new technologies and judicious policy.

It’s worth noting that across this very fraught and contested spectrum of opinions—from techno-optimism and green growth to degrowth—everyone agrees on one thing: In order to avoid the very worst of possible climate futures, the material and carbon throughput of the economy must be drastically reduced. The attitude in which they go about achieving that reduction, however, could not be more different.

There is indeed evidence that relative decoupling has been underway since the mid-20th century, but so far only partially, and only in rich countries—and then only after an enormous intensification of resource use. Early evidence of dematerialization from midcentury peaks in countries such as the United States, furthermore, does not yet extend to powerhouses such as India or China.

It is also hotly debated whether this partial trend properly accounts for rich countries’ offshoring of material-intensive manufacturing, or for the so-called rebound effect, whereby more efficient and “dematerialized” production of goods and services translates directly into increased consumption, immediately canceling out ecological gains. Degrowthers, for their part, argue that the absolute decoupling is an outright fairy tale—one as dangerous as its proponents accuse degrowth of being.

Whether decoupling amounts to magical thinking or not, given current data, one would have to be very optimistic indeed to believe that decoupling scenarios alone will bring economic activity into accord with planetary boundaries and tipping points. The lack of evidence for an immediate silver bullet brings us back to the multitrillion-dollar question: If an economic deceleration is inevitable, are our options really delusion versus despair?

It’s no mystery why we fear economic slowdowns. Crumbling state finances, recessions, and economic transitions are enormously painful and disruptive, especially for those in the lowest income brackets. Juicing growth numbers as a means of alleviating economic pain and discontent, however, is increasingly looking like a holdover from an era when politicians could promise that rapidly rising tides lift all boats.

In today’s world—when global inequality is reaching prewar levels—it perhaps makes sense to lay at least equal focus on the redistribution of wealth accumulated in the 20th century, precisely with an eye toward insulating society’s most vulnerable from economic and environmental shocks that are increasingly intertwined. This makes even more sense if we consider that in the rich world, the previous century’s boom-time growth rates might be the result of nonlinear, irreproducible events, such as women entering the workforce, globalization, the financialization of government debt, and the use of imperialist force.

Perhaps, as techno-optimists predict, artificial intelligence will lead to yet another gain in productivity, yielding a 20th-century-style spike in growth. (Though this comes with the potential cost of AI turning on its human makers, which would hardly be conducive to economic flourishing.) For now, the shifting composition of developed economies calls for a correspondingly historic shift in policy focus.

“A fundamental difference between natural science theories and social science theories is that natural science theories, if valid, hold for all times and places,” former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wrote in a opinion for the International Monetary Fund published in 2020, “In contrast, the relevance of economic theories depends on context.” He continued: “I am increasingly convinced that current macroeconomic theories … may be unsuited to current economic reality and so provide misguided policy prescriptions.” The same could be true of chasing after GDP growth.

In that case, one might imagine that it would be the task of the degrowth movement to persuade the broader public of the point. And yet, if the idea of doing more with less has a branding problem—which is to say, a political problem—it’s not a problem that anyone in the degrowth movement seems immediately positioned to solve. Almost no one I speak to in Zagreb is inclined to “consider a better word.”

The issue of language and popular appeal hovers over the conference. On a smoke break, a local Croatian volunteer, a mother of two with a marketing background, voices concern over how the scholars gathered here plan on communicating degrowth to a larger audience. She tells me that her school-aged children recently came home announcing they no longer want to shop at secondhand stores. “It feels very different to degrow when it’s a necessity versus a choice,” she says.

During lunch, over plates of (vegan) lentil Bolognese, another volunteer, a Zagreb native in her 20s and a member of a local all-female eco-collective, shares impressions from her own visits to the academic sessions, many of which are open to the public. She’s come directly from a presentation about a hypothetical “ecofeminist city,” where she, too, wondered about vocabulary and broader appeal. “The girls in my eco-village, the ones [the presenters] should be speaking for,” she says, “I don’t think they would have the education to understand. I wondered, ‘Who is your audience?’”

Consulting the abstract for the ecofeminist city in question, the authors’ proposals indeed seem less than tangible or concrete: References include “configuration of spatial and temporary infrastructures” and “feminist time politics.”

The volunteer’s question—“Who is your audience?”—is a fair one, especially since parts of the movement really do hold the potential for popular interest.

After all, the primary aim of degrowth, Saito explains, is to carve a space “outside of capitalism,” whose market logic has colonized too much of our social and economic decision-making, but also outside of traditional socialism or Marxist productivism, whose ecological record in Maoist China and Soviet Russia proved just as devastating.

Though I’ve been wondering whether it’s the word “communism” or “degrowth” that poses the greater threat to the movement going mainstream, the more I ask, the more it seems that to degrowthers such as Saito, “communism” means something much closer to municipalism and an expansion of the welfare state (financed, presumably, through a mechanism that rejects both imperialism and economic growth) than it does to classical economic planning.

“I call it commonification,” Saito says of his own updating of Marxist principles for a climate-distressed era. “Make it common; make it common wealth. A society based on that kind of commonification of our basic needs, which shouldn’t be left to the market logic.” Every thinker I speak with is committed to democracy and rejects the one-party state. Saito easily sees room for market mechanisms: “Of course you should be able to buy an apple or an orange on the market. But does that apple need to come from Africa?” There is a commitment to an expansion of social services such as universal health care, education, public transport, and housing, with additional discussion of reduced work weeks and job guarantees; people use less energy and fewer resources when they buy and work less.

Saito himself doesn’t mind if others “use a different term” than degrowth “as long as they’re willing to think outside of capitalism.” But he notes that using provocative language often serves an important purpose; degrowth was coined precisely to be unmarketable, with its founders anticipating the greenwashing that has befallen the likes of terms such as “sustainability,” “green growth,” and “carbon footprint.”

The persistent use of radical terms, Saito further argues, can pave the way for progress. “Ten years ago,” he says, “in America, you couldn’t say the word ‘socialism.’ Today the taboo has been lifted, with politicians like Bernie Sanders and AOC [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez].”

On the other hand, one could just as easily argue that the normalization of former taboos is simply a sign of greater polarization and discontentment with capitalism; taboos are being lifted just as quickly on right.

In this tense political environment, should the degrowth movement continue in its usual role of leftist activists and academics, or has the time come to think more like politicians—in other words, people who have to compromise?

On this point, the movement seems divided.

It’s clear, however, which faction is ascendent. On a concluding panel, activist and scholar Julia Steinberger, who wields considerable influence on social media, recaps the need to liaise between the public and centers of political power. “Science tells us we need to degrow,” she says, “but this means nothing to politicians unless we can also help them translate this to the public.”

She describes presenting data to elected officials, only to have them respond that their hands are tied unless they are also given a way to sell the implications: “And we said, ‘We thought that was your job and the journalists’ job.’ And they said, ‘No, we can’t do it, and the journalists aren’t doing it, so I guess it’s your job.’”

Natural allies for the movement, not to mention connections to more mainstream economics, do exist. If degrowth plays its cards right, its proponents might not have to do the job alone.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Christopher F. Rufo

Published: Apr 29, 2024

Stanford University, its campus lined with redwoods and eucalyptus trees, has long been known as a hub for innovation and entrepreneurship. But in recent years, another ideological force has taken root: “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” a euphemism for left-wing racialism. DEI, in fact, has conquered Stanford.

I have obtained exclusive analysis from inside Stanford outlining the incredible size and scope of the university’s DEI bureaucracy. According to this analysis, Stanford employs at least 177 full-time DEI bureaucrats, spread throughout the university’s various divisions and departments.

Stanford’s DEI mandate is the same as those of other universities: advance the principles of left-wing racialism, hire faculty and admit students according to identity, and suppress dissent on campus under the guise of fostering a “culture of inclusion” and “protected identity harm reporting.”

Julia Steinberg, an undergraduate and journalist at the Stanford Review, believes that DEI is a “black box” system of rewards and punishments for enforcing ideological adherence. “I’ve observed as students are reported by their peers for constitutionally protected speech,” and professors are denounced and accused of discrimination by other students “for the crime of not being PC enough in their research or in class,” she says. “Who fits or doesn’t fit into the DEI caste system determines a student or professor’s summary judgement.”

DEI’s growth at Stanford has been fast. In 2021, the Heritage Foundation counted 80 DEI officials at the university. That number has more than doubled since then.

Sophie Fujiwara, a recent graduate, explains that DEI has become “unavoidable” for students, with “mandatory classes” and “university-spon.sored activities.” Left-wing students increasingly believed that this wasn’t enough. Following the George Floyd revolution of 2020, these students “demanded more initiatives and funding from the university for DEI-related subjects.”

Stanford’s DEI initiatives are not limited to humanities departments or race and gender studies. The highest concentration is in Stanford’s medical school, which has at least 46 diversity officials. A central DEI administration is led by chief DEI officer Joyce Sackey, with sub-departments throughout the medical school. Pediatrics, biosciences, and other specialties all have their own commissars embedded in the structure.

In the sciences, DEI policies have advocated explicit race and sex discrimination in pursuit of “diversity.” The physics department, for example, has committed to a DEI plan with a mandate to “increase the diversity of the physics faculty,” which, in practice, means reducing the number of white and Asian men. Administrators are told to boost the representation of “underrepresented groups,” or “URGs,” through a variety of discriminatory programs and filters.

Ivan Marinovic, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, says that DEI programs have had a disastrous impact on campus. He describes DEI as a “Trojan horse ideology” that undermines “equality before the law, freedom of expression, and due process.”

Given Stanford’s current trajectory, DEI will likely keep growing. At each step, it will degrade the quality of scholarship and academic rigor. The question is whether dissenters—professors, students, and alumni who reject the ideological capture of the university—will have enough power to dislodge more than 100 full-time bureaucrats. Stanford’s new president, Richard Saller, was hired in part to moderate ideological influence on campus. But according to sources familiar with Saller in his previous role as dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences, he probably lacks the strength to push back against DEI.

The fight ahead will be tough. As it has been before, Stanford may once again serve as a leading indicator of where American higher education is going.

[ Via: https://archive.today/WSzFI ]

==

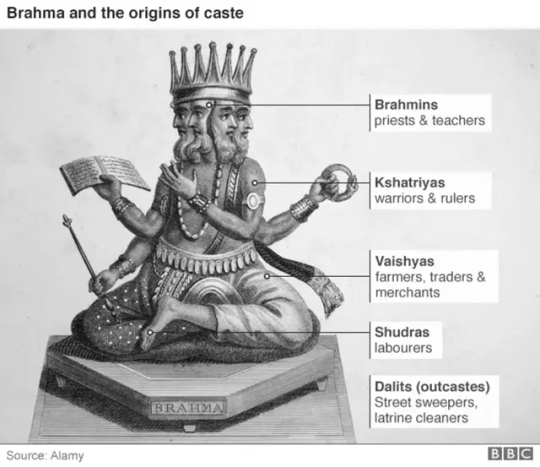

I've never thought about it that way before, but it really is a caste system, with the straight white males as the Dalits/untouchables, and the trans, black, disabled lesbian being the Brahmins.

#Christopher F. Rufo#Christopher Rufo#Stanford University#DEI#diversity#equity#inclusion#diversity equity and inclusion#DEI bureaucracy#DEI must die#racial discrimination#authoritarianism#woke authoritarianism#academic corruption#corruption of education#higher education#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

There has been a push within the industry to get advertising to shift towards more sustainable products, for example electric vehicles rather than combustion engine cars, or plant-based foods as opposed to beef. This is seen by the industry as one of the critical ways they can have an impact, and such shifts do deliver reductions in emissions. But Wise worries that simply replacing emissions-intensive consumption with a lower-emissions version isn’t enough to decarbonise the economy.

And while a handful of agencies are looking to sell greener options, the actions of the industry as a whole seem to show a resistance to considering such things as their responsibility. The transportation sector, identified as probably the most significant area of consumption for the top 10% by Julia Steinberger, a professor of ecological economics at the University of Lausanne and the author of a 2020 paper on the topic, is a good example. “The categories of consumption that the wealthiest people overconsume or overspend on and that constitute the big difference in their emissions is really flying longer distances, and driving bigger cars longer distances, so transportation is really the big one,” Steinberger said.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supporters of #NoHostageLeftBehind Open Letter to Joe Biden - Part 2/2

Gabe Turner

Gail Berman

Gary Barber

Genevieve Angelson

Gideon Raff

Grant Singer

Greg Berlanti

Guy Nattiv

Hannah Fidell

Hannah Graf

Harlan Coben

Harold Brown

Henrietta Conrad

Howard Gordon

Iain Morris

Imran Ahmed

Inbar Lavi

Jackie Sandler

Jake Graf

Jake Kasdan

Jamie Ray Newman

Jaron Varsano

Jason Fuchs

Jason Biggs & Jenny Mollen Biggs

Jason Segel

JD Lifshitz

Jeff Rake

Jen Joel

Jeremy Piven

Jesse Itzler

Jesse Sisgold

Jill Littman

Jody Gerson

Joe Hipps

Joe Quinn

Joe Russo

Joe Tippett

Joel Fields

John Landgraf

Jon Bernthal

Jon Glickman

Jon Liebman

Jonathan Baruch

Jonathan Groff

Jonathan Tropper

Jonathan Marc Sherman

Jonathan Steinberg

Jonathan Tisch

Josh Goldstine

Josh Greenstein

Josh Grode

Julia Lester

Julie Greenwald

Karen Pollock

Kelley Lynch

Kevin Kane

Kevin Zegers

Kitao Sakurai

KJ Steinberg

Laura Pradelska

Lauren Schuker Blum

Laurence Mark

Laurie David

Lee Eisenberg

Leslie Siebert

Leo Pearlman

Limor Gott

Lina Esco

Liz Garbus

Lizanne Rosenstein

Lizzie Tisch

Lorraine Schwartz

Lynn Harris

Lyor Cohen

Mandana Dayani

Maria Dizzia

Mara Buxbaum

Marc Webb

Marco Perego

Mark Feuerstein

Mark Shedletsky

Mark Scheinberg

Mathew Rosengart

Matt Lucas

Matt Miller

Matthew Bronfman

Matthew Hiltzik

Matti Leshem

Dame Maureen Lipman

Max Mutchnik

Maya Lasry

Meaghan Oppenheimer

Melissa Zukerman

Michael Ellenberg

Michael Aloni

Michael Green

Michael Rapino

Michael Weber

Mike Medavoy

Mimi Leder

Modi Wiczyk

Nancy Josephson

Natasha Leggero

Neil Blair

Neil Druckmann

Nicole Avant

Nina Jacobson

Noa Kirel

Noah Oppenheim

Noreena Hertz

Odeya Rush

Oran Zegman

Pasha Kovalev

Paul Haas

Paul Pflug

Peter Traugott

Rachel Riley

Rafi Marmor

Ram Bergman

Raphael Margulies

Rebecca Angelo

Rebecca Mall

Reinaldo Marcus Green

Rich Statter

Richard Kind

Rick Hoffman

Rick Rosen

Robert Newman

Rob Rinder

Roger Birnbaum

Roger Green

Rosie O'Donnell

Ryan Feldman

Sam Trammell

Sarah Baker

Sarah Bremner

Sarah Treem

Scott Tenley

Seth Oster

Scott Braun

Scott Neustadter

Shannon Watts

Shari Redstone

Sharon Jackson

Shauna Perlman

Shawn Levy

Sheila Nevins

Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Tikhman

Skylar Astin

Stacey Snider

Stephen Fry

Steve Agee

Steve Rifkind

Susanna Felleman

Susie Arons

Todd Lieberman

Todd Moscowitz

Todd Waldman

Tom Freston

Tom Werner

Tomer Capone

Tracy Ann Oberman

Trudie Styler

Tyler James Williams

Vanessa Bayer

Veronica Grazer

Veronica Smiley

Whitney Wolfe Herd

Will Graham

Yamanieka Saunders

Yariv Milchan

Ynon Kreiz

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t understand why the movie Can You Ever Forgive Me isn’t talked about more among lesbians.

It’s truly wonderful.

Melissa McCarthy plays Lee, an unashamedly misanthropic lesbian who hates kids and despises most people. There is an exchange between Lee and Jack, a gay man played by Richard E. Grant, that made me laugh out loud.

Lee: You’re friends with… Julia something

Jack: Steinberg!

- Yeah

- She’s not an agent anymore. She died.

- She did? Jesus, that’s young

- Maybe she didn’t die. Maybe she just moved back to the suburbs. I always confuse those two… no, that’s right: she got married and had twins.

- Better to have died

- Indeed!

Could you really wish for better writing?

Sure, Lee isn't hot and there is no hot makeout scenes. It isn't that type of lesbian film. I like movies with hot lesbian sex scenes, let's be clear. But the movie makes it very clear that both Lee and Jack are homosexuals. There is no ambiguity there. Lee is obviously a difficult person to be around but I really liked her personally.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's behind the sharp rise in U.S. antisemitism

Tearing down posters of kidnapped Israeli children. Death threats sent to Jewish schools and students. Swastikas spray painted in public spaces.

U.S. antisemitism is at near-historic levels, according to FBI director Christopher Wray.

WBUR is a nonprofit news organization. Our coverage relies on your financial support. If you value articles like the one you're reading right now, give today.

"A group that makes up 2.4%, roughly, of the American population, that same population accounts for something like 60% of all religious-based hate crimes," Wray said.

But are the acts antisemitic, anti-Zionist, or anti-Israel? The distinctions are blurred.

Today, On Point: The deep historical and intellectual undercurrents driving the sharp rise in antisemitism in America.

LISTEN 47:30 https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2023/11/03/whats-behind-the-sharp-rise-in-u-s-antisemitism

Guests Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. Author of a recent Los Angeles Times op-ed called “Nothing has prepared me for the antisemitism I see on college campuses now.”

Julia Steinberg, junior at Stanford University, where she’s studying comparative literature. She writes for The Stanford Review, the school’s conservative paper. Intern at The Free Press.

Simon Sebag Montefiore, British historian. His latest book is “The World: A Family History of Humanity." He’s also written a history of the Middle East called “Jerusalem: The Biography.”

Related:

1 note

·

View note

Text