#Kapuscinski

Text

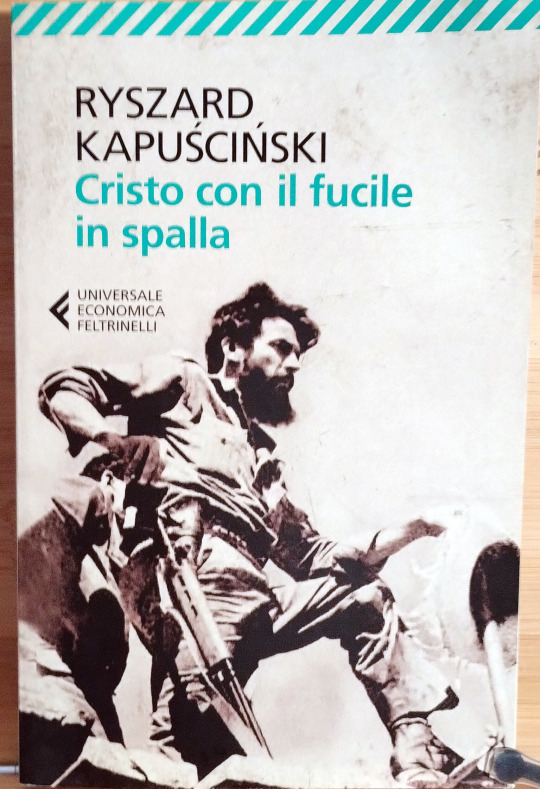

Ryszard Kapuscinski

CRISTO CON IL FUCILE IN SPALLA

2013 Feltrinelli

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nel 1975, dopo una lunga guerra di liberazione, l'Angola cessa di essere una colonia portoghese e conquista formalmente l'indipendenza. Ryszard Kapuscinski, che nella sua carriera di reporter aveva già seguito ben ventisette rivoluzioni, era lì anche questa volta. Intrappolato nell'assedio di Luanda, l'autore racconta, talvolta con tono umoristico, quello che accade in tempo di guerra in una "città chiusa", dalla quale tutti scappano come topi da una nave che affonda: prima i portoghesi con i loro beni e masserizie, poi i negozianti, la polizia, i tassisti, i barbieri, la nettezza urbana, e, infine, anche i cani. Attento in primo luogo agli esseri umani, l'autore fa rivivere con tratti affettuosi e vivaci le poche, umili e belle persone con cui aveva stretto amicizia e con le quali aveva condiviso i momenti di sconforto, privazione e paura: dona Cartagina, Diogene, il comandante Farrusco, il proiezionista dell'unico cinema rimasto in città. Infine, Carlotta, una donna giovane e bella cui Kapuscinski, per la prima volta in un suo libro, dedica un ritratto così commosso e delicato da farne un personaggio indimenticabile. La copertina del libro mostra una Carlotta orgogliosa e sorridente. . . . . . #ryszardkapuściński #kapuscinski #ancoraungiorno #libro #libri #libros #libreria #buch #livre #book #books #bookstagramitalia #bookstagram #consiglidilettura #librodaleggere #libroconsigliato #librodelgiorno #saggistica #nonfiction #angola #guerra #storia #colonialismo #africa #feltrinelli @feltrinelli_editore https://www.instagram.com/p/CmZUHILIevA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#ryszardkapuściński#kapuscinski#ancoraungiorno#libro#libri#libros#libreria#buch#livre#book#books#bookstagramitalia#bookstagram#consiglidilettura#librodaleggere#libroconsigliato#librodelgiorno#saggistica#nonfiction#angola#guerra#storia#colonialismo#africa#feltrinelli

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the heart of what Kapuściński was up to when writing The Emperor and several of his other remarkable works (his approach has been called Magical Journalism, a "non-fiction" sibling of Marquez's Magical Realism) is alluded to in this passage from a 2012 review of a book about the journalist in the Columbia Journalism Review: "Strict accuracy was not his paramount concern; when a friend who had been with him during riots in Dar es Salaam commented that he had misreported certain details, she says he shouted at her, 'You don't understand a thing! I'm not writing so the details add up --- the point is the essence of the matter.' Thus he left a long list of embellishments... to catalog. When Kapuściński wrote, for example, that fish in Lake Victoria became big after feeding on the corpses dumped there by Idi Amin, he was telling a good tale, but not one that was true."

1 note

·

View note

Text

"August 16, 2018

By Ryszard Kapuscinski

(An excerpt)

Herodotus — who lived 2,500 years ago and left us his “History” — was the first reporter. He is the father, master and forerunner of a genre –reportage. Where does reportage come from?

It has three sources, of which travel is the first. Not in the sense of a tourist trip or outing to get some rest. But travel as a hard, painstaking expedition of discovery that requires a decent preparation, careful planning and research in order to collect material out of talks, documents and your own observations on the spot. That’s just one of the methods Herodotus used to get to know the world. For years he would travel to the farthest corners of the world as the Greeks knew it. He went to Egypt and Libya, Persia and Babylon, the Black Sea and the Scythians of the north. In his times, the Earth was imagined to be a flat circle in the shape of a plate encircled by a great stream of water by the name of Oceanus. And it was Herodotus’ ambition to get to know that entire flat circle.

Herodotus, however, besides being the first reporter, was also the first globalist. Fully aware how many cultures there were on Earth, he was eager to get to know all of them. Why? The way he put it, you can learn your own culture best only by familiarizing yourself with others. For your culture will best reveal its depth, value and sense only when you find its mirror reflection in other cultures, as they shed the best and most penetrating light on your own.

(What did he accomplish with his comparative method of confrontation and mirror reflection? Well, Herodotus taught his countrymen modesty, tempered their self-conceit and hubris, the feeling of superiority and arrogance toward non-Greeks, toward all others. “You claim that the Greeks have created gods? Not at all. As a matter of fact, you’ve appropriated them from the Egyptians. You say your structures are magnificent? Yes, but the Persians have a far better system of communication and transportation.”

Thus Herodotus tried by means of his reportage to consolidate the most important message of Greek ethics: restraint, a sense of proportion and moderation.

Beside travel, another source of reportage is other people, those encountered on the road, and those we travel to meet in order to get them to convey their knowledge, tales and opinions to us. Here Herodotus turns out to be the master extraordinaire. Judging by what he writes, whom he meets and the way he talks to them, Herodotus comes across as a man open and full of good will toward others, making contact with strangers easily, curious about the world, investigative and hungry for knowledge. We can imagine the way he acted, talked, asked and listened. His attitude and bearing show what is essentially important to a reporter: respect for another man, his dignity and worth. He listens carefully to his heartbeat and the way thoughts cross his mind.

Herodotus notices the weakness of human memory, aware that his interlocutors relate different and often contradictory versions of the same event. Trying to be impartial and objective, he conscientiously leaves for us to decide about the most disparate variants and versions of the same story. Hence his reports are multidimensional, rich, vivid and palpable. Herodotus is a tireless reporter. He takes the trouble to go hundreds of miles by sea, on horseback or simply on foot only to hear another version of a past event. He wants to know, no matter the price he pays, and wants his knowledge be the most authentic, the closest to the truth. This conscientiousness sets a good example of the responsibility we assume, for all that we do.

The third source of reportage is the reporter’s homework: to read what has been written and endures in texts, inscriptions or graphic symbols on the topic a given reporter is working on. Herodotus also teaches us how to be investigative and careful. In his times, the amount of materials he could rely on was far smaller than that available today. So whatever he managed to collect was precious. He naturally was well read in Homer, Hesiod, poets and playwrights. He would decipher inscriptions on temples and town walls. Everything was important, potentially able to reveal a message or new meanings. By his own example Herodotus showed that a reporter should be a careful observer, sensitive to details seemingly insignificant and banal, which may turn out to be symbols or signs of worlds much more important, stretching farther out, and of higher order.

“All people have a natural tendency to acquire knowledge,” runs the sentence with which Aristotle, a little younger than Herodotus, begins his “Metaphysics,” adding that it is the eye that plays the most important role, because it perceives differences best. We also know the importance of the eye of the reporter, focused, penetrating, noticing what seems invisible, which may be the other face of a given phenomenon, often the most essential.

However, the snag is that to notice what is the most essential, you often have to be on the spot. And to get there, you have to take a trip, to travel. And out of those travels, his presence on the spot resulted in Herodotus’ great reportage about the world that we have been reading for 25 centuries.

Reportage is created out of what Aristotle called “tendency to acquire knowledge.” And in this human desire, a reporter’s passion meets the expectations of his readers, listeners and spectators. A reporter, driven by the “tendency to acquire knowledge,” tries to meet halfway the curiosity about the world of his readers, their own “tendency to acquire knowledge.”

And here is why good reportage is so popular in the contemporary world. The contemporary man, living in the world conjured up by the media of illusions and appearances, simulacra and fables, feeling instinctively that he is fed untruth, hypocrisy, falsehood, and virtual manipulation, seeks something that has the power of truth and reality, things authentic, that is.

I see that during my meetings with readers. When I tell about one of my reporter’s adventures, someone is likely to interrupt me with the question: “Is that authentic?” I assure the person that I have really been there. And then a wave of relief rolls across the audience and a friendly atmosphere sets in. Why, they’re taking part in something real, since someone who has witnessed the event is actually standing right in front of them.

What is a literary reportage, then? How to define and describe it? It’s not an easy matter, as we are living at the moment of “blurred genres,” a new species.

Working in the countries of the Third World, as a correspondent of a press agency for quite a long time, I had this unsatisfied feeling resulting from the paucity of the language of press information when confronting the rich, full-of-variety, colorful, often hard-to-define reality of those cultures, customs or beliefs. The everyday language of information that we use in the media is very poor, stereotypical and formulaic. For this reason huge areas of reality we deal with are beyond the sphere of description, which the formulaic message is unable to convey. So what is the way out of this cul-de-sac of unsatisfied feelings and frustration? I availed myself of the suggestion of such writers as Truman Capote, Norman Mailer and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, whose writing straddles the border of fiction and press chronicle. They introduced the term “New Journalism”, “nuevo periodismo.” By this term they meant the kind of writing in which authentic events, true stories and accidents are described with language containing the writer’s personal opinions and reactions and often fictional asides as added color; with the techniques and manners of fiction, that is. So this creative and enriched combination of two different manners and techniques of communicating and describing make up a literary reportage.

This has turned out to be a happy and seminal “blurring of genres,” especially in the light of the progress in science and technology, which has enriched and incredibly differentiated the picture of the world, ever more difficult to describe with language.

I saw it for myself writing “The Shadow of the Sun” (Afrikanishes Fieber). How to describe a jungle with the language of press information? This is downright impossible unless you reach for the treasury of belles-lettres, for its rich variety of expression. On the other hand, today, literature avails itself continuously of reportage production. Notice how many reporters are characters of fiction, how many descriptions are typically in the reporter’s vein among classically fictitious fragments and dialogues!

In this multicultural world, people from those other cultures demand that they be treated as equal, command the same respect and be in our good graces. It is a well-established given that there are no higher or lower cultures and what makes a difference is just the result of their specific geographical and historical conditions.

The problem is that we know little about other cultures, and rather than decent knowledge we are likely to make do with easy and false stereotypes. This is what Herodotus understood all too well. Better still, he knew that only mutual knowledge of each other makes understanding and connecting possible, as the only way to peace and harmony, cooperation and exchange. With this assumption in mind, a reporter takes a plunge into the hive of activity: travels, investigates, takes notes, explains why others behave differently from us and shows that those other ways of existence and understanding of the world have a logic of their own, are sensible and should be accepted rather than generate aggression and war.

So it’s plain to see what responsibility lies with our work, reportage. Plying our trade, we are not just men or women of writing pursuits, but also some kind of missionaries, translators and messengers. We do not translate from one text into another, but from one culture into another in order to make them mutually better understood and thereby closer."

From the site of the American travel writer and essayist Rolf Potts (https://rolfpotts.com/ ).

Ryszard Kapuściński (Polish: [ˈrɨʂart kapuɕˈt͡ɕij̃skʲi]i; 4 March 1932 – 23 January 2007) was a Polish journalist, photographer, poet and author (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryszard_Kapu%C5%9Bci%C5%84ski).th

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Oil creates the illusion of a completely changed life, life without work, life for free. ... The concept of oil expresses perfectly the eternal human dream of wealth achieved through lucky accident ... In this sense, oil is a fairy tale and like every fairy tale a bit of a lie.

Ryszard Kapuscinski

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

He looks like he got stung by a wasp!

He looks like a swollen potato.

#ANSWER#DAY 6#admiral-craymen#1580TH#Sick of u kindly donate a body like an Hourglass#it's ticking like a clock. It's a matter of fact#his Name is “Ryszard Kapuscinski” And he looks like a vaguely anime t-rex

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

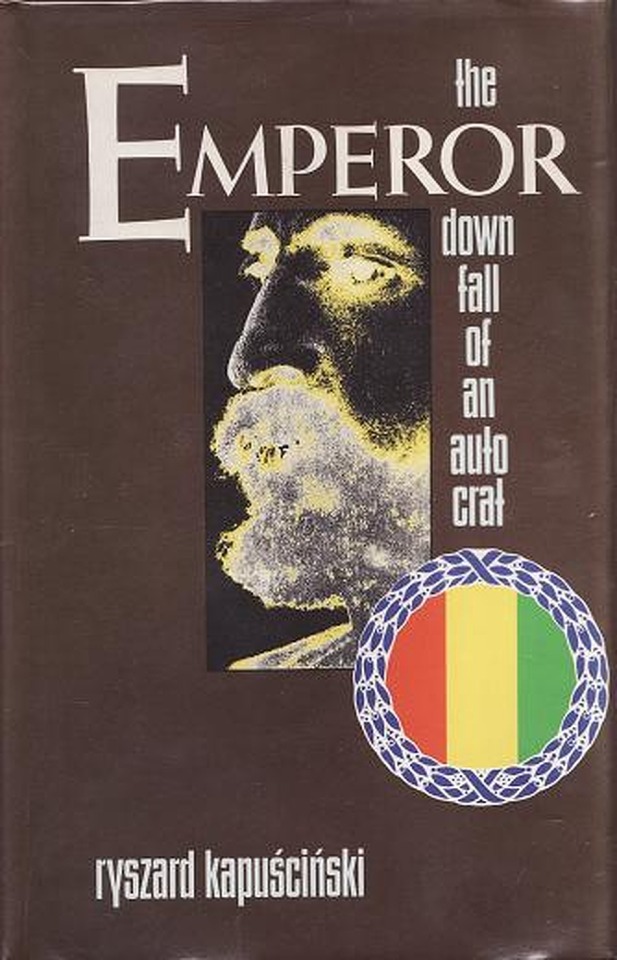

#Ryszard Kapuscinski#Angola#Raul De La Fuente#Damian Nenow#Animated Film#Operación Carlota#Cuban Revolution#Portuguese Colonization#António de Oliveira Salazar#African Liberation#photojournalism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resonancias

Resonancias #Opinión de Juan José Rodríguez en #LABRECHA

Leí El Emperador de Ryszard Kapuscinski hace algo más de cuarenta años. Me lo regaló Fernando Silva Nieto. Al paso del tiempo se convirtió en uno de los libros que más he regalado y que releo de vez en cuando. Hace algunas semanas salió a relucir en una conversación de amigos y me dieron ganas de volverlo a leer, tantas que tuve que comprarlo nuevamente pues mi viejo ejemplar no apareció por…

0 notes

Text

Guion Teatral

Otra vida en Ruanda

ACTO I

Escena primera

Dos monjas belgas y un periodista en un hospital pequeño y limpio.

PERIODISTA (Con humildad): Hermanas, muchas gracias por acogerme aquí en el hospital. Es mi primer viaje a Ruanda y justo llego en su independencia, en su capital Kigali.

MONJA 1: Es muy probable que aquí no haya ni un hotel. Aun así, siendo independiente Ruanda, Kigali sigue siendo un pueblo de mala muerte.

MONJA 2: La monarquía y el feudalismo han dejado de existir, y la casta tutsi ha perdido su poder. Ahora el gobierno lo conforma la casta hutu, liderada por el joven periodista Grégoire Kayibanda.

PERIODISTA (Con extrañeza): ¿Castas? ¿Tutsi? ¿Hutu? Yo he venido aquí a sacar toda la información que pueda sobre este país. ¿Me pueden explicar qué es todo esto?

MONJA 2 (Mirando con extraño): Para ser un periodista que viene acá, ya debería saber todo esto.

MONJA 1 (Da un suspiro antes de hablar): A diferencia de varios países africanos que son llanos y altiplanos, Ruanda, como ha notado, es un país montañoso, con tantas montañas que algunas alcanzan la altura de dos mil y tres mil metros, a veces hasta más altas. Por eso se le llama a veces el “Tíbet de África”, pero no solo por su rara geografía sino también por su sociedad.

MONJA 2: Normalmente los países africanos son multitribales por ley, a veces viven trescientas tribus en un solo país como en El Congo. Aquí no es así, solo hay una comunidad, los bayaruanda. Se dividen en 3 castas: los agricultores hutus, los jornaleros y criados twa, y los dueños de rebaños, los tutsis. Este sistema se formó siglos atrás, en el siglo XII.

MONJA 1: No, se formó en el siglo XV.

MONJA 2 (Con furia): No existen fuentes que prueben eso.

MONJA 1: Ni tampoco que prueben lo tuyo. Déjame, sigo. El caso es que el tutsi es el señor y el hutu su sirviente. Los hutus vivían de cultivar tierra y entregaban una parte de sus cosechas a los tutsis a cambio de protección y una vaca.

PERIODISTA (Asombrado): ¿Por qué saben tanto?

MONJA 2 (Seriamente): Vivir aquí te cambia la vida.

MONJA 1: Entonces, como decía, los tutsis en sí tenían el monopolio, igual que en el feudalismo. Lo que sí se sabe con pruebas es que a mediados del siglo XX ocurre un conflicto entre estas dos castas por territorio.

MONJA 2: Así es. Ruanda es pequeña y, como ya es costumbre en otros países africanos, la solución podría ser retirarse y ocupar otros territorios por sus largas extensiones. Aquí no hay cómo retroceder. A medida que crecen los rebaños y el poder tutsi, también aumenta la necesidad de más pastos. Estos pastos se pueden crear quitando tierra a los hutus, echándolos de sus campos. Para variar, los campos eran de mala calidad, entonces alguien tenía que irse o debía morir.

PERIODISTA: Es muy improbable que eso haya continuado así.

MONJA 1: Justo en ese momento crece el movimiento independentista. Los belgas que gobernaban Ruanda no estaban preparados para esto, y Bruselas, que apoyaba a los tutsis, cambia repentinamente y apoya a los hutus.

PERIODISTA: Entonces Ruanda estalla en 1959 y los hutus se rebelan contra sus amos. Los degollaban y rompían el cráneo con machetes, azadas y lanzas, quemaban sus aldeas, mataban al ganado y comían tanta carne como quisieran. Algunos tutsis huyen al Congo, Uganda, Burundi y Tanganica. Ahora el poder es de los hutus y Ruanda recupera la independencia.

MONJA 2 (Extrañada): ¿Cómo lo sabe?

MONJA 1 (Extrañada): Se supone que no sabía de esto.

PERIODISTA: Sé algunas de las cosas que me han dicho. Otras no las sabía, pero ¿qué podía hacer yo? Necesito toda la información posible.

Escena segunda

Entra un tutsi desesperado y herido

TUTSI (Entra y cuando ve al periodista se abalanza sobre él, pero sus fuerzas no son suficientes y cae al piso, grita con lágrimas): Tú, ¿apoyas a los hutus verdad? Yo vengaré a mi pueblo, ya lo verás.

MONJA 1 (Con espanto): ¡Qué está pasando! ¡Dios mío!

PERIODISTA (Retrocediendo): Creo que está confundido. Yo no apoyo a nadie y no se de qué me está hablando.

TUTSI (Con pena): Entonces, ayúdame. No sabes lo que he hecho para venir aquí, con la esperanza de encontrar algún hermano y me entero de que todos están muertos.

PERIODISTA: Usted no parece ser de aquí. Dígame, ¿qué pasó?

MONJA 2 (Lo ayuda a levantarse): Está muy herido, hermana, trae las vendas.

TUTSI (Hablando con dificultad): Así es. Yo era tan solo un joven cuando ocurrió la masacre. Mis padres fallecieron y yo tuve que vivir viajando desde las fronteras de Ruanda con tutsis que apenas tenían para ellos mismos. Hace unos años, invadimos Ruanda para recuperar el territorio desde la frontera de Burundi, pero esta vez fue diferente. El ejército Hutu nos detuvo y como recompensa masacró a más de veinte mil de mis hermanos, descuartizados por sus machetes. Todos los que alguna vez llamé familia ya no están. Yo logré escapar y vine aquí para ver si algún tutsi me ayudaba, pero no he encontrado nada.

PERIODISTA (Con un sentimiento de culpa): Hay cosas de mí que me hacen sentir tan culpable por esto y no sé cómo enmendarlas. Esta puede ser mi oportunidad para resolverlas. Ahora me puedes llamar hermano mío. No soy tutsi y poco he sufrido de lo que tú has sufrido, pero estoy dispuesto a dar mi vida por tu pueblo.

ACTO II

PERSONAJES

Tutsi

Periodista

Soldado tutsi

Soldado tutsi 2

Escena primera

En un cuartel militar, sentados los personajes en un círculo hablando, transcurren 15 años.

SOLDADO TUTSI: Periodista, la vida aquí no es fácil. Has demostrado que estás con nosotros día a día. Nosotros nos esforzamos con un objetivo en mente, hacemos reuniones secretas aquí. La mayoría de este ejército son tutsis que buscan venganza por la humillación de sus familias.

PERIODISTA: ¿Cómo terminaron aquí?

TUTSI: Este es el cuartel militar de Uganda. La vida en los campamentos de las fronteras es pobre y muy desesperante. Cada vez crecen nuevas generaciones, y los jóvenes como yo quieren actuar y luchar por un objetivo que, por supuesto, es la devolución de los territorios de nuestros antepasados. Estamos en Uganda ya que abandonar un campo de refugiados es prohibido por las autoridades locales. Aquí no rige esa ley.

SOLDADO TUTSI: ¿Has oído del clan Akazu y de Habyarimana en todo esto?

PERIODISTA: No he oído aún, me faltan aprender muchas cosas. La vida en el cuartel es limitante a diferencia de mi vida como periodista.

SOLDADO TUTSI: El Akazu es un círculo íntimo de poderosos hutus. La esposa de Habyarimana, Agathe, y sus hermanos controlan gran parte del poder político y militar en Ruanda. Su influencia es enorme y su principal objetivo ha sido mantener el control hutu a cualquier costo.

TUTSI: Habyarimana llegó al poder hace unos años en un golpe de estado que él mismo creó y se volvió presidente en el 73. Provenía de un clan muy extremista y rápidamente derrocó al clan moderado del antiguo presidente. Ya introdujo un solo partido político donde tienes que pertenecer desde tu nacimiento. Si criticas, te mandarán a la cárcel o a la muerte.

SOLDADO TUTSI (Con rabia): Es por eso que debemos hacer algo ya para pararlos. Por ahora somos muy débiles y no podemos hacer nada contra ellos, pero pronto podremos. Nuestro ejército crece rápidamente y debemos salir antes de que Uganda sospeche algo.

Escena segunda

Entra Soldado tutsi 2 y se sienta con ellos

SOLDADO TUTSI 2 (Se sienta cansado y pone su arma al lado suyo): Hace algún tiempo yo tenía padres, hermanos, tenía familia. Jamás pensé perderlo todo tan rápido. Ahora ya las piernas no me funcionan.

(Pausa y respira con dificultad)

SOLDADO TUTSI 2: Recuerdo los días en que jugábamos en los campos, fingíamos ser hutus y jugábamos a la cosecha con ellos. Pero todo eso se acabó tan pronto. Vi a mi familia ser matada, uno por uno. Intenté vengarlos, pero no pude. Ahora me apena saber que no podré hacerlo

(Hace una pausa)

SOLDADO TUTSI 2: Aunque mi cuerpo esté fallando, mi deseo de justicia sigue dentro de mí. No puedo caminar, pero puedo soñar. Y sueño que algún día unos niños puedan ver el mundo como yo lo vi de niño.

(Tose)

SOLDADO TUTSI 2: No voy a llegar a la batalla final. Por favor, lo que hagan que sea por aquellos que hemos perdido y por los que aún están sufriendo. Yo aquí acabo, pero su lucha comienza. Luchen por la libertad.

(Todos se quedan en silencio durante un momento y un soldado recoge el cuerpo y se lo lleva)

PERIODISTA: Muchos luchan por orgullo y no por justicia. Él lo hacía por las dos.

ACTO III

PERSONAJES:

Tutsi

Periodista

Soldado Joven

Escena Primera:

En un territorio montañoso, transcurren otros 15 años.

TUTSI: ¿Qué haces?

PERIODISTA: Escribo en la bitácora lo sucedido: La noche del 30 de septiembre de 1990, salimos de los cuarteles del ejército ugandés y de los campamentos fronterizos. En la madrugada, entramos en territorio de Ruanda. Habyarimana tiene un ejército débil y desmoralizado; podemos llegar a la capital en uno o dos días.

TUTSI: Si extrañas tu vida como periodista, ¿por qué decidiste venir?

SOLDADO JOVEN (Los interrumpe): Me he enterado de que soldados franceses han caído en la capital, Kigali.

PERIODISTA: No podemos enfrentarnos a ellos; nos expulsarían inmediatamente. Hay que quedarse aquí y aguantar como podamos.

TUTSI: Es verdad. Anda a informar a los otros no nos dejaremos de los hutus y tutsis traicioneros.

Escena segunda:

En un territorio montañoso, transcurren 3 años.

PERIODISTA: Has oído, van a hacer firmar a Habyarimana un acuerdo con el Frente Nacional de Ruanda y nosotros, los guerrilleros, vamos a ser parte del gobierno.

TUTSI: Eso significa que el clan Akazu perdería su poder y ellos no están dispuestos a eso. Hace varios años me contaron que el clan Akazu tenía una "solución final", pero no entendí hasta ahora. El Frente es la "solución final", van a empezar una guerra y es una gran oportunidad para nosotros para recuperar territorio.

PERIODISTA (Escucha la radio junto a Tutsi): ¿Has oído? Han derribado con un misil el avión del presidente Habyiramana. Es nuestra oportunidad.

(Los dos corren a la batalla)

(Soliloquio del Periodista)

PERIODISTA (Mirando al público): Hoy es el día en que enmendo mis errores con este pueblo. Seguramente ya lo he hecho, pero me he vuelto parte de este pueblo y, a su vez no, esta singular comunidad tan únicos. Todos corren con machetes y lanzas, yo llevo un arma de fuego. ¿Por qué tiene que haber tanta guerra aquí? Tutsis o hutus, ninguno es mejor que otro. Yo lo he aprendido después de ser un periodista que alentaba el levantamiento hutu y ahora al tutsi. Puede ser muy hipócrita de mi parte. Pero en este momento, veo que el verdadero conflicto no está en la entre estos pueblos, sino en la falta de compasión. No se trata de quién tiene la razón, sino de cómo aprender a vivir. Hoy ya es muy tarde, me enfrento a mis propias decisiones, a mis propios errores. Pero también me enfrento a la realidad: que la guerra no es la respuesta, que la violencia solo causa más violencia. Y aunque ya sea demasiado tarde para mí, espero que esta sea la última de las guerras. Porque hasta que no haya una gran masacre los dueños del dolor no pararan.

FIN

0 notes

Text

Graduation

Have you ever performed on stage or given a speech?

When I finished my degree in Journalism, my classmates asked me if I wanted to give a speech in our certification day.

And due to I like to write so much. I wrote a beautiful speech about our first day in college until our graduation day.

So I put all my emphasis and I finished my text with a great end:

“and rememember that: one journalist…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Saturday morning vibes. What are you currently reading?

#books#booklr#bookblogger#book photography#book photo#meet the reader#nonfiction#travel writing#nobody leaves#ryszard kapuscinski

1 note

·

View note

Note

What books have you been reading since your last update?

I don't remember what I shared with my last update, so apologies if I repeat anything, but these are some of the books I've read over the past couple months:

•An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s by Doris Kearns Goodwin (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

I'm actually still reading this new book by the legendary Doris Kearns Goodwin, so I still have a couple of chapters to go, but I can definitely recommend it. This is undoubtedly the most personal book that DKG has ever written, and it's a fascinating story.

•Charging a Tyrant: The Arraignment of Saddam Hussein by Greg Slavonic (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Life: My Story Through History by Pope Francis with Fabio Marchese Ragona (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•George VI and Elizabeth: The Marriage That Saved the Monarchy by Sally Bedell Smith (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Byron: A Life in Ten Letters by Andrew Stauffer (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat by Ryszard Kapuscinski

•Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism by Jeffrey Toobin (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•The Making of a Leader: The Formative Years of George C. Marshall by Josiah Bunting III (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Year of the Three Kaisers: Bismarck and the German Succession, 1887-88 by J. Alden Nichols

•God Is Ever New: Meditations on Life, Love, and Freedom by Pope Benedict XVI (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Paul VI: The Divided Pope by Yves Chiron (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Buffalo Bill and the Mormons by Brent M. Rogers (BOOK | KINDLE)

•The Great Abolitionist: Charles Sumner and the Fight for a More Perfect Union by Stephen Puleo (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Macho Man: The Untamed, Unbelievable Life of Randy Savage by Jon Finkel (BOOK | KINDLE)

•Business Is About to Pick Up!: 50 Years of Wrestling in 50 Unforgettable Calls by Jim Ross with Paul O'Brien (BOOK | KINDLE | AUDIO)

•Zanzibar Was a Country: Exile and Citizenship Between East Africa and the Gulf by Nathaniel Mathews (BOOK | KINDLE)

#Books#Reading List#Book Suggestions#My Reading List#Book Recommendations#Recommended Reading#What I've Been Reading#An Unfinished Love Story#Doris Kearns Goodwin#Simon & Schuster#An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s#Charging a Tyrant: The Arraignment of Saddam Hussein#Saddam Hussein#Life: My Story Through History#Pope Francis#Biographies#Papal Biographies#George VI and Elizabeth: The Marriage That Saved a Monarchy#Sally Bedell Smith#King George Vi#Byron: A Life in Ten Letters#Andrew Stauffer#The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat#Haile Selassie#Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism#Jeffrey Toobin#Timothy McVeigh#Oklahoma City Bombing#The Making of a Leader: The Formative Years of George C. Marshall#General Marshall

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

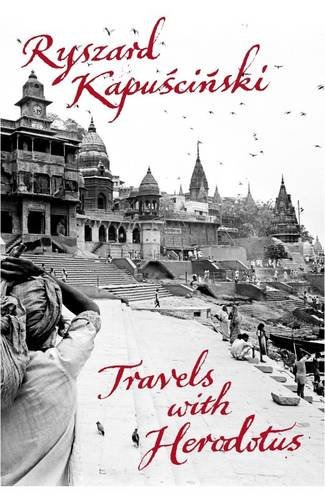

Travels with Herodotus

“ The Observer Ryszard Kapuściński

Review

Lessons of the Histories

In Travels with Herodotus, the late, great Polish writer Ryszard Kapuscinski weaves epic stories into his own reportage to stunning effect, says Stephen Smith

Stephen Smith

Sun 17 Jun 2007 00.41 BST

Travels with Herodotus

by Ryszard Kapuscinski

Allen Lane £20, pp275

With Agatha Christie, you know you're off and running when the first stiff turns up in the library, harbinger of a terrible body count. In the case of Ian McEwan, it's a hint of transgressive how's-your-father. Aficionados of Ryszard Kapuscinski, the late grandmaster of reportage, know to hug themselves in anticipation when the following conditions obtain: our man is the last European left in a sweltering hellhole, a wretched government is on its last legs and about to give way to packs of marauding goons and all contact with the outside world has been lost. This was the scene of the Polish writer and journalist's gripping Another Day of Life (1975). He was the only foreign correspondent in the Angolan capital, Luanda, as the Portuguese colonialists fled and rival militias closed in on the abandoned city. In his suffocating hotel, Kapuscinski sweats and frets, a Kafka of the tropics. If the book had been any more tightly wound, it would have turned back into wood pulp in your trembling fingers.

Open Kapuscinski's Imperium (1994), an account of his travels through the collapsing Soviet Union, and you may well be met with a passage like this one, describing the airport at Yerevan in Armenia as 'hundreds, thousands of people' awake to another day of waiting in vain for a seat on a plane, any plane. 'How long have they been sleeping here? Well, some not so long; this is only their first night. And those over there, the crumpled up, unshaven, unkempt ones? Those - a week. And those others one cannot even get closer to because they stink so terribly? Those - a month.'

Travels with Herodotus, which has been published in English following Kapuscinski's death earlier this year, will not disappoint his admirers. We are with the indefatigable reporter in Congo in 1960. 'There is no functioning radio station, no government. I am trying to get out of here - but how? The closest airport is closed. The roads (now in the rainy season) are swamped, the ship that once plied the River Congo has long ceased to do so.' Bliss! You know that by the time you finish Travels with Herodotus, you'll be shaking your own gnawed fingernails from its pages. Once again we have before us the strangely cheering image of the lonely news agency man from eastern Europe endlessly chastising himself for the gaps in his knowledge rather than giving himself credit for what he has learnt the hard way. As before, the roving reporter is bowed down beneath his own bodyweight in books, including the Histories of Herodotus, the ancient Greek who opened the young Kapuscinski's eyes to the world. The great traveller of antiquity, he says, was 'someone who always had many questions and was ready to wander thousands of kilometres to find an answer to any one of them'. Kapuscinski could be writing about himself, of course.

A much-travelled journeyman who came to book-writing in mid-career, Kapuscinski also invites comparison with fellow Pole Joseph Conrad and mention of the author of The Secret Agent leads us to the ticklish issue of Kapuscinski the spy. He was named as a former communist operative after his death. He had allegedly collaborated with the party in Poland in return for the rare licence he enjoyed to travel to the outside world - 'to cross the border', as he puts it. To which one can only say that if it is true, a 'deal' of this kind is what one would expect the authorities to have insisted on. What matters is how Kapuscinski observed his side of the bargain, and that was to publish The Emperor (1978). Ostensibly an account of Haile Selassie's court in Ethiopia and its hysterical feudalism, it was read in his native Poland as a mordant if samizdat commentary on matters closer to home.

Frankly, anyone who was paying attention will know the reporter's dispatches were the flimsiest cover for his 'product', as the spymasters call it. What was encrypted in them was Kapuscinski's humanity. Somehow, he crosses Ethiopia with a local driver who knows only two English expressions: 'Problem' and 'No problem'. How do the pair communicate? Kapuscinski relies on the 'tradecraft' of his own extraordinary empathy. 'Everything speaks; the expression of the face and eyes, the gestures of the hand and movements of the body ... dozens of other transmitters, amplifiers and mufflers which together make up an individual being.'

It may seem perverse to recommend Travels with Herodotus for the beach. But if you haven't encountered Kapuscinski before, you'll be pleasantly surprised by how much satisfaction, as well as salience, there is to be found in this perfect discomfort read.

· Stephen Smith is the culture correspondent of BBC Newsnight

Three to read

Reportage

Imperium by Ryszard Kapuscinski

The journalist's personal portrait of the life and death of the USSR, 1939 to 1991.

Dispatches by Michael Herr

Frontline reports from the madness and mayhem of the Vietnam War.

All the Wrong Places by James Fenton

Powerful examination of South East Asian politics, from the fall of Saigon to the Philippines under Marcos.”

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/jun/17/travel.travelbooks

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Pledge your LOYALTY 🎄 and don't be scared it had to be the VICTIM of a horrendous, mind-warping Crime? is his name is “Ryszard Kapuscinski” and he looks like a vaguely anime T-Rex

#QUOTE#DAY 20#Apparently his name is “Ryszard Kapuscinski” and he looks like a toothpick going Through his eyes see what he knows.

0 notes

Text

“Il primo gesto di ogni vero viaggio ha qualcosa di lento. Non credete a chi si mostra deciso, privo di dubbi e incertezze. Nasconde sensazioni incomprensibili e contraddittorie. Lui stesso non vuole crederci: ha sognato e desiderato per mesi questo momento e ora come è possibile che non voglia più partire? E’ qualcosa di inspiegabile. Nasconde, dietro il sorriso, una stanchezza improvvisa, un indefinibile senso di solitudine. Nella sua testa stanno passando, come cavalli a galoppo, mille sagge ragioni che suggeriscono di non andare. La partenza è un momento di fine e di inizio. E’ necessario, credetemi, trovare coraggio. Occorre coraggio nel cancellare ogni dubbio e affrontare quel ‘momento di fare spazio al proprio sogno-bisogno’. E ne occorre tanto per sciogliere gli ormeggi e mollare la cima che ci tiene legati alla banchina. ‘Fa’ salpare il tuo sogno, ficcaci dentro la tua scarpa’, dice il poeta romeno Paul Celan. Non sempre è facile.”

Andrea Semplici, In viaggio con Kapuscinski. Dialogo sull’arte di partire

47 notes

·

View notes