#National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2023/09/17/fatigue-cfs-longcovid-mitochondria/

Here’s an article about Amanda Twinam’s search for answers to her problems with fatigue, a search that someday may lead to a fuller understanding of ME/CFS, similar diseases, and to treatments. For many of us, these ameliorations or cures will come too late for us to recover our health or for us to recover any semblance of the lives we should have had, but perhaps it will give all the young(er) people with ME, Long-Covid, etc., hope.

#ruth feiertag#chronic illness#myalgic encephalomyelitis#isolation#covid#pandemic#spoonie#washington post#Amanda Twinam#autoimmune diseases#mononucleosis#Paul Hwang#mitochondria#mitochondrial respiration#National Heart Lung and Blood Insititute#ME/CFS#WASF3#supercomplex#PNAS#Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

What happens when raindrops land on insects? | REUTERS

26 January 2024

—

Super slow-motion video seeks to help answer the question of just what happens when a raindrop lands on an insect.

In a study by researchers in Florida, the water strider, known for its unique way of moving on water, was filmed in slow motion while water droplets landed on it, in much the same way it would be bombarded during rainfall.

The researchers revealed specific features that help these insects survive heavy rainfall, such as their passive behaviour and the ability to resurface through swimming, in addition to their water repellent, super-hydrophobic nature.

"When striders are pushed into the water, we observe the formation of an air bubble around the body of the insect, which is attributed to the water repellent nature of its exoskeleton.

This air bubble prevents drowning. The water striders are also lightweight. The light weight of water striders allows for their passive transport along craters and jets," said Daren Watson, an Assistant Professor at Florida Polytechnic University and the lead author of the paper.

"Water striders are impervious to raindrop collision forces and submerged by collapsing craters," published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The also found that during droplet impact, water striders and plastics of similar size appear almost identical.

This could provide insights into how other floating debris - such as microplastics - might be transported beneath the water's surface during intense rainfall.

"Impact events onto floating microplastics comprised of multiple drops like we would experience during rainfall, which are also more probable at higher rainfall intensities, are more likely to render microplastics submerged, thus increasing their exposure beneath our water bodies.

We intend to build on our results to further explore the transport of microplastics found atop water bodies," Watson told Reuters.

#water strider#water droplets#slow motion#microplastics#Youtube#insect#Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)#Florida Polytechnic University

0 notes

Text

"the observed crime rates for undocumented immigrants were considerably lower than those for legal immigrants and native-born citizens."

#government#oligarchy#republicans#abuse of power#us politics#constitution#democrats#trump#conflict of interest

720 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chinese Scientists Are Leaving the United States! Here’s Why That Spells Bad News For Washington.

— By Christina Lu and Anusha Rathi | July 13, 2023 | Foreign Policy

A view of Building 10 on the campus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the United States on March 12, 2020. Maddie Meyer/Getty Images

Facing an increasingly suspicious research climate, a growing number of Chinese scientists are leaving the United States for positions abroad, the latest indicator of how worsening U.S.-China relations are complicating academic collaboration and could hamstring Washington’s tech ambitions.

Chinese scientists living in the United States have for decades contributed to research efforts driving developments in advanced technology and science. But a growing number of them may now be looking elsewhere for work, as deteriorating geopolitical relations fuel extra scrutiny of Chinese researchers and Beijing ramps up efforts to recruit and retain talent. Between 2010 and 2021, the number of Chinese scientists leaving the United States has steadily increased, according to new research published last month. If the trend continues, experts warn that the brain drain could deal a major blow to U.S. research efforts in the long run.

“It’s absolutely devastating,” said David Bier, the associate director of immigration studies at the Cato Institute. “So many of the researchers that the United States depends on in [the] advanced technology field are from China, or are foreign students, and this phenomenon is certainly going to negatively impact U.S. firms and U.S. research going forward.”

From semiconductor chips to artificial intelligence, technology has been at the forefront of U.S.-China competition, with both Washington and Beijing maneuvering to strangle each other’s sectors. Cooperation, even in key sectors like combating climate change, has been rare.

From 2010 to 2021, the number of scientists of Chinese descent who left the United States for another country has surged from 900 to 2,621, with scientists leaving at an expedited rate between 2018 and 2021, according to research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Nearly half of this group moved to China and Hong Kong in 2010, the study said, and a growing percentage of Chinese scientists have relocated to China over the years.

While this number represents a small fraction of the Chinese scientists in the United States, the uptick reflects researchers’ growing concerns and broader apprehension amid a tense geopolitical climate. After surveying 1,304 Chinese American researchers, the report found that 89 percent of respondents wanted to contribute to U.S. science and technology leadership. Yet 72 percent also reported feeling unsafe as researchers in the United States, while 61 percent had previously considered seeking opportunities outside of the country.

“Scientists of Chinese descent in the United States now face higher incentives to leave the United States and lower incentives to apply for federal grants,” the report said. There are “general feelings of fear and anxiety that lead them to consider leaving the United States and/or stop applying for federal grants.”

The incentives to leave are twofold. Beijing has funneled resources into research and development programs and has long attempted to recruit scientists, even its own, from around the world. For one of its initiatives, the Thousand Talents Plan, Beijing harnessed at least 600 recruitment stations worldwide to acquire new talent. “China has been really trying to lure back scientists for a long time,” said Eric Fish, the author of China’s Millennials.

But this latest outflow of Chinese scientists accelerated in 2018, the same year that then-U.S. President Donald Trump unveiled the China Initiative, a controversial program that was aimed at countering IP theft—and cast a chill over researchers of Chinese descent and collaborations with Chinese institutions. In 2020, he also issued a proclamation denying visas for graduate students and researchers affiliated with Chinese universities associated with the military.

Although the Biden administration shut down the China Initiative, experts warn that its shadow still looms over Chinese scientists. More than one-third of respondents in the PNAS survey reported feeling unwelcome in the United States, while nearly two-thirds expressed concerns about research collaboration with China.

“There is this chilling effect that we’re still witnessing now, where there is a stigma attached to collaboration with China,” said Jenny Lee, a professor at the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona.

The challenges are emblematic of how the breakdown in U.S.-China relations has thrown universities into a geopolitical firestorm, particularly as some states’ lawmakers pressure them to sever ties with Chinese counterparts. On the U.S. side, interest in Mandarin language studies and study abroad has plummeted over the years, largely the result of worsening ties, Beijing’s growing repression, and the coronavirus pandemic. Today, while there are roughly 300,000 Chinese students in America, only 350 Americans studied in China in the most recent academic year. If interest continues to recede, experts warn of spillover effects that could hamper Washington’s understanding of Beijing.

“We’re losing a generation of people who are knowledgeable about China,” said Daniel Murphy, the former director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University. “I’m concerned that the United States is going about this issue in a way that excessively focuses on risks of the academic relationship, without due consideration for the benefits. And I think we see this in a whole host of arenas, and that it’s bipartisan.”

At the same time as a growing number of Chinese scientists exit the United States, new students appear to be facing higher barriers to entry as student visa denials and backlogs reach record high levels. According to a blog post by the Cato Institute, student visa denials peaked at about 35 percent in 2022—the highest rate recorded in two decades.

Student visa denial data is not available by nationality, but Bier, the Cato Institute expert who wrote the piece, said that there is a high degree of correlation between denial rates for B-visas, or tourist visas, and student visas. “Having reviewed the B-visa denials in China, it’s pretty clear that the Chinese overall visa denial rate has increased significantly over the last few years and is at a level now where it’s the highest it’s been in decades,” he said.

Just as some Chinese scientists are looking abroad, these challenges are pushing a growing number of international students to turn elsewhere for academic opportunities. Students are increasingly heading to countries like Canada, Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom, all of which are opening their doors to high-skilled workers and researchers. To attract more talent, the United Kingdom has issued “Global Talent” and “High Potential Individual” visas, which allow scholars from top universities to work there for 2-3 years and 1-5 years, respectively.

Universities are being impacted “by geopolitical tensions, by political agendas, and so it’s certainly inhibiting U.S. Universities’ ability to attract the best and brightest,” Lee said.

— Christina Lu is a Reporter at Foreign Policy. Anusha Rathi is an Editorial Fellow at Foreign Policy.

#Chinese Scientists 🇨🇳#United States 🇺🇸#Suspicious Research Climate#U.S.-China Relations#David Bier#Cato Institute#National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)#Federal Grants#U.S. President Donald Trump#Jenny Lee#University of Arizona#Daniel Murphy#Global Talent#High Potential Individual#Visas#Political Agendas#Geopolitical Tensions#Christina Lu

0 notes

Text

“I loathe that word ‘pristine.’ There have been no pristine systems on this planet for thousands of years,” says Kawika Winter, an Indigenous biocultural ecologist at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. “Humans and nature can co-exist, and both can thrive.” For example, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in April, a team of researchers from over a dozen institutions reported that humans have been reshaping at least three-quarters of the planet’s land for as long as 12,000 years. In fact, they found, many landscapes with high biodiversity considered to be “wild” today are more strongly linked to past human land use than to contemporary practices that emphasize leaving land untouched. This insight contradicts the idea that humans can only have a neutral or negative effect on the landscape. Anthropologists and other scholars have critiqued the idea of pristine wilderness for over half a century. Today new findings are driving a second wave of research into how humans have shaped the planet, propelled by increasingly powerful scientific techniques, as well as the compounding crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. The conclusions have added to ongoing debates in the conservation world—though not without controversy. In particular, many discussions hinge on whether Indigenous and preindustrial approaches to the natural world could contribute to a more sustainable future, if applied more widely.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

These structures on leaves are especially for beneficial mites to live in :)

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hassianycteris messelensis was an early bat that lived in what is now Germany during the mid-Eocene, about 47 million years ago.

It's generally considered to be very closely related to the common ancestry of modern bats – but a recent study suggests that the stem-bat evolutionary tree is actually quite a bit more complicated than previously thought.

It had a 35-40cm wingspan (~14"-16"), and thanks to the exceptional preservation of the Messel Pit fossil site we actually know some details about its external life appearance. One specimen preserves a soft-tissue impression of its ear shape, and fossilized melanosomes suggest that its fur was colored reddish-brown.

Its wing proportions indicate it was adapted to fly high and fast in open spaces, and its strong jaws and preserved gut contents show it mainly preyed on tough-shelled insects like beetles.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Colleary, Caitlin, et al. "Chemical, experimental, and morphological evidence for diagenetically altered melanin in exceptionally preserved fossils." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.41 (2015): 12592-12597. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1509831112

Habersetzer, Jörg, Gotthard Richter, and Gerhard Storch. "Paleoecology of early middle Eocene bats from Messel, FRG. Aspects of flight, feeding and echolocation." Historical Biology 8.1-4 (1994): 235-260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10292389409380479

Jones, Matthew F., K. Christopher Beard, and Nancy B. Simmons. "Phylogeny and systematics of early Paleogene bats." Journal of Mammalian Evolution 31.2 (2024): 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-024-09705-8

Wikipedia contributors. “Hassianycteris” Wikipedia, 23 Jan. 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hassianycteris

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#hassianycteris#hassianycterididae#chiroptera#bat#mammal#stem-bat#art#paleocolor

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two key protein structures in the body are being visualized for the first time, thanks in part to the latest technology in the University of Cincinnati's Center for Advanced Structural Biology—potentially opening the door for better designed therapeutics. The research of a trio of UC structural biologists was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Continue Reading.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

More lines of evidence that Microraptor-like dinosaurs could fly!

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.24584

https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2016-03245-001

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160412104810.htm

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/08/15/a-growing-share-of-us-husbands-and-wives-are-roughly-the-same-age/

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI-accelerated Nazca survey nearly doubles the number of known figurative geoglyphs and sheds light on their purpose

Jul 2024

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

While I one day hope to have a PNAS* paper, I will be content with currently having an LOL** paper in review.

*Proceedings of the National Academy of Science

**Limnology and Oceanography Letters

All my emails to my supervisor have the subject line "Manuscript edits LOL"

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

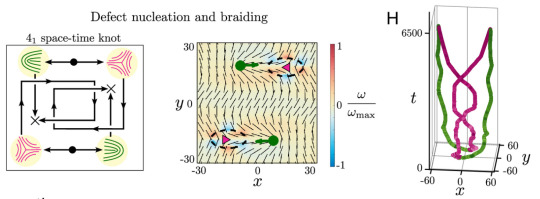

After 4 years of work, I've finally published my very first peer-reviewed theory paper: Design rules for controlling active topological defects

(and it's open access! :D)

I am sooo excited to finally be able to share this! I'll probably write some more in the future about what it was like to work on this project, but for now here's what I want to say about it:

I think this work is a beautiful example of how the long, meandering paths of curiosity-driven research can bring us in completely unexpected directions, yielding new ideas and technologies that might never have been found by problem- or profit-driven research.

We started this project because we were interested in the fundamental physics of active topological defects; we wanted to understand and develop a theory to explain their effective properties, interactions, and collective behaviors when they're hosted by a material whose activity is not constant throughout space and time.

Along the way, we accidentally stumbled into a completely new technique for controlling the flow of active 2D nematic fluids, by using symmetry principles to design activity patterns that can induce self-propulsion or rotation of defect cores. This ended up being such a big deal that we made it the focus of the paper, for a few reasons:

Topological defects represent a natural way to have discrete information in a continuous medium, so if we wanted to make a soft material capable of doing logical operations like a computer, controlling active defects might be a really good way of putting that together.

There have also been a number of biological systems that have been shown to have the symmetries of active nematics, with experiments showing that topological defects might play important roles in biological processes, like morphogenesis or cell extrusion in epithelia. If we could control these defects, we'd have unprecedented control over the biological processes themselves.

Right now the technique has only been demonstrated in simulations, but there are a number of experimental groups who are working on the kinds of materials that we might be able to try this in, so hopefully I'll get to see experimental verification someday soon!

#physics#soft matter#materials science#science#academia#mathematics#topology#biology#biotechnology#tech#publishing#196

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big news for hagfish fans!!

references

Bardack, D. (1991). First Fossil Hagfish (Myxinoidea): A Record from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois. Science, 254(5032), 701–703. https://doi.org/10.1126/SCIENCE.254.5032.701

Fernholm, B., & Mincarone, M. M. (2023). A new species of the hagfish genus Eptatretus (Myxinidae) from the Bahamas, western North Atlantic. Journal of Fish Biology, 102(4), 962–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/JFB.15343

Fudge, D. S., Levy, N., Chiu, S., & Gosline, J. M. (2005). Composition, morphology and mechanics of hagfish slime. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208(24), 4613–4625. https://doi.org/10.1242/JEB.01963

Hirasawa, T., Oisi, Y., & Kuratani, S. (2016). Palaeospondylus as a primitive hagfish. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-016-0057-0

Miyashita, T., Coates, M. I., Farrar, R., Larson, P., Manning, P. L., Wogelius, R. A., Edwards, N. P., Anné, J., Bergmann, U., Richard Palmer, A., & Currie, P. J. (2019). Hagfish from the Cretaceous Tethys Sea and a reconciliation of the morphological-molecular conflict in early vertebrate phylogeny. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(6), 2146–2151. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1814794116/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL

Parasramka, V. (2023). Manufacturing synthetic Hagfish slime skeins using embedded 3D printing. https://hdl.handle.net/2142/120467

Siu, R. (2023). Additive manufacturing methods for fabricating synthetic Hagfish skeins. https://hdl.handle.net/2142/120593

Zintzen, V., Roberts, C. D., Anderson, M. J., Stewart, A. L., Struthers, C. D., & Harvey, E. S. (2011). Hagfish predatory behaviour and slime defence mechanism. Scientific Reports 2011 1:1, 1(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00131

#will be reposting this on hagfish birthday#hagfish#eddie infodumps#eddie in the ocean#marine biology

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Split Reaction

Two people with the same condition might respond very differently to the same treatment. It’s a source of huge frustration for patients and doctors alike, so researchers are investigating why anti-VEGF therapies, which can improve vision in patients with the eye condition neovascular age-related macular degeneration by reducing the overproduction of VEGF protein, work in some patients but not others. A team compared protein levels in the eye fluid of patients undergoing treatment and found that the drugs can inadvertently trigger overproduction of another protein that may worsen the condition. When a factor (called HIF-1α, red in the mouse eye section pictured) that typically boosts this other culprit was blocked, both proteins were better managed and the conventional treatments worked better in animal models, raising hopes for more effective treatments for all.

Written by Anthony Lewis

Image from work by Deepti Sharma and colleagues

Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Image originally published with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), November 2024

You can also follow BPoD on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook

22 notes

·

View notes