#Neo-Babylonian period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Iraqi museum discovers missing lines from the 'Epic of Gilgamesh'

It's not unusual for fantasy epics to endure for years. (Right, Game of Thrones fans?)

But even George R.R. Martin would be shocked to learn about century-and-a-half wait for a new chapter of the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the world's oldest written stories.

The Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraq has discovered 20 new lines to the ancient Babylonian poem, writes Ted Mills for Open Culture.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates back to 18th Century BC, was pieced together from fragments that tell the story of a Sumerian king who travels with a wild companion named Enkidu.

As Mills explains, scholars were well aware that new fragments of the poem could possibly turn up — modern readers are most familiar with a version discovered in Nineveh in 1853 and during the war in Iraq, as looters pillaged ancient sites.

The Sulaymaniah Museum acquired the tablet in 2011, as part of a collection purchased from a smuggler, according to Osama S.M. Amin at Ancient History Et Cetera.

"The collection was composed of 80-90 tablets of different shapes, contents and sizes.

All of the tablets were, to some degree, still covered with mud. Some were completely intact, while others were fragmented.

The precise location of their excavation is unknown, but it is likely that they were illegally unearthed from what is known today as the southern part of the Babel (Babylon) or Governorate, Iraq (Mesopotamia)."

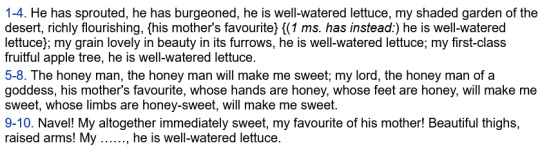

The tablet is three fragments joined together, dating back nearly 3,000 years to the Neo-Babylonian period.

An analysis by the University of London's Farouk Al-Rawi reveals more details from the poem's fifth chapter, according to Amin.

The new lines include descriptions of a journey into the "Cedar Forest," where Gilgamesh and Enkidu encounter monkeys, birds and insects, then kill a forest demigod named Humbaba.

In a paper for the American Schools of Oriental Research, Al-Rawi describes the significance of these details:

The previously available text made it clear that [Gilgamesh] and Enkidu knew, even before they killed Humbaba, that what they were doing would anger the cosmic forces that governed the world, chiefly the god Enlil.

Their reaction after the event is now tinged with a hint of guilty conscience, when Enkidu remarks ruefully that … "we have reduced the forest [to] a wasteland."

The museum's discovery casts new light on Humbaba, in particular, who had been depicted as a "barbarian ogre" in other tablets.

As Mills writes:

"Just like a good director’s cut, these extra scenes clear up some muddy character motivation and add an environmental moral to the tale."

#Epic of Gilgamesh#oldest written stories#Sulaymaniyah Museum#iraq#ancient Babylonian poem#poem#Sumerian king#Enkidu#tablet#Neo-Babylonian period#Gilgamesh#Cedar Forest#Humbaba#fantasy epic#Enlil

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

I must say within Assyriology, the people doing Neo-Babylonian really do have some of the coolest ressources. I was at first intimated by Parker and Dubberstein’s Babylonian Chronology (1946), but now I can’t stop converting dates from the Neo-Babylonian calendar into the Gregorian one.

I mean to be fair just having some types of documents that are consistently dated is insanely cool and helpful, but it becomes even more fun when it’s not the 4th Addaru in the 33rd year of Nebuchadnezzar II, but 1 March 571 BC. Like, suddenly, it’s so relatable and I’m like, I know a 1 March!

Also, you can convert dates up until 45/46 AD which by Assyriological standards is so late. The last dateable cuneiform text is from 79/80 AD, concurrent with the eruption of Vesuvius (cf. Hunger & de Jong 2014, “Almanac W22340a from Uruk”)!

And then you also get family names in the Neo-Babylonian period, at least for the upper classes, and boy is that helpful when every guy’s called something like Bēl-iddin or Nabû-šum-uṣur. And you have these amazing prosopographies like Kümmel’s Familie, Beruf und Amt im spätbabylonischen Uruk (1979) and Bongenaar’s The Neo-Babylonian Ebabbar Temple at Sippar (1997) to just look up what a specific person has been up to.

Also, the family trees. I love the family trees!

And then there’s also Jursa’s Neo-Babylonian Legal and Administrative Documents (2005) which just contains so much helpful information! All of these books just make me so happy and for all their citing unpublished texts that I as a poor student simply can’t lay my eyes on, these Neo-Babylonian people really got their reference works figured out.

0 notes

Photo

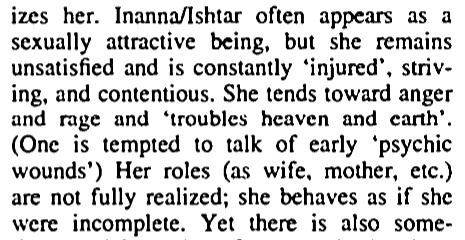

Cylinder seals are cylindrical objects carved in reverse (intaglio) in order to leave raised impressions when rolled into clay. Seals were generally used to mark ownership, and they could act as official identifiers, like a signature, for individuals and institutions. A seal’s owner rolled impressions in wet clay to secure property such as baskets, letters, jars, and even rooms and buildings. This clay sealing prevented tampering because it had to be broken in order to access a safeguarded item. Cylinder seals were often made of durable material, usually stone, and most were drilled lengthwise so they could be strung and worn. A seal’s material and the images inscribed on the seal itself could be protective. The artistry and design might be appreciated and considered decorative as well. Cylinder seals were produced in the Near East beginning in the fourth millennium BCE and date to every period through the end of the first millennium BCE.

-

Mesopotamia, 3000-2700 B.C.

Tools and Equipment; seals

Black marble

-

This seal illustrates a scene with the goddess Ishtar welcoming a devotee. A cuneiform inscription is incorporated into the scene.

Cylinder seals of the ancient Near East

Invented in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) about 3500 BC, cylinder seals were used as magical amulets, administrative tools, and jewellery. These small cylinders had a design carved in intaglio, and a hole through them, enabling them to be worn on string.

When these seals were rolled onto clay, a continuous impression was left of the design. Shown here are three such examples of these impressions, with the cylinder seal itself alongside the second example. The first example dates to 800-600 BC (Neo-Elamite), the second is the oldest at 3000-2700 BC, and the third, ca. 700 BC (Achaemenid).

The Walters provides the following description for the first example:

In the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Elam, to the east of Mesopotamia in Iran, experienced a brief period of prosperity during which it allied itself with Babylonia against Assyria. The seals produced in Elam during this period reflect themes derived from Mesopotamia, such as the lion hunt seen here; however, the strong modeling, the almost decorative patterning of the details, and the exaggerated posture of the lion characterize the local Elamite style.

Cylinder Seal with a Lion Hunt, courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore: 42.797.

Cylinder Seal, courtesy of the LACMA: M.71.73.11c.

Cylinder Seal with Ishtar Welcoming a Devotee, courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore: 42.782.

#history#art#art history#economics#trade#commerce#jewellery#languages#neo-elamite period#mesopotamia#elam#achaemenid empire#babylonia#neo-babylonian empire#neo-assyrian empire#iraq#iran#ishtar#cylinder seals#marble#cuneiform#cylinder seal ref

815 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others)

This article wasn’t really planned far in advance. It started as a response to a question I got a few weeks ago:

However, as I kept working on it, it became clear a simple ask response won’t do - the topic is just too extensive to cover this way. It became clear it has to be turned into an article comprehensively discussing all major aspects of the perception of Inanna’s gender, both in antiquity and in modern scholarship. In the process I’ve also incorporated what was originally meant as a pride month special back in 2023 (but never got off the ground) into it, as well as some quick notes on a 2024 pride month special that never came to be in its intended form, as I realized I would just be repeating what I already wrote on wikipedia.

To which degree can we speak of genuine fluidity or ambiguity of Inanna’s gender, and to which of gender non-conforming behavior? Which aspects of Inanna’s character these phenomena may or may not be related to? What is overestimated and what underestimated? What did Neo-Assyrian kings have in common with medieval European purveyors of Malleus Maleficarum? Is a beard always a type of facial hair? Why should you be wary of any source which calls gala “priests of Inanna”?

Answers to all of these questions - and much, much more (the whole piece is over 19k words long) - await under the cut.

Zeus is basically Tyr: on names and cognates

The meaning of a theonym - the proper name of a deity - can provide quite a lot of information about its bearer. Therefore, I felt obliged to start this article with inquiries pertaining to Inanna’s name - or rather names. I will not repeat how the two names - Inanna and Ishtar - came to be used interchangeably; this was covered on this blog enough times, most recently here. Through the article, I will consistently refer to the main discussed deity as Inanna for the ease of reading, but I’d appreciate it if you read the linked explanation for the name situation before moving forward with this one.

Sumerian had no grammatical gender, and nouns were divided broadly into two categories, “humans, deities and adjacent abstract terms” and “everything else” (Ilona Zsolnay, Analyzing Constructs: A Selection of Perils, Pitfalls, and Progressions in Interrogating Ancient Near Eastern Gender, p. 462; Piotr Michalowski, On Language, Gender, Sex, and Style in the Sumerian Language, p. 211). This doesn’t mean deities (let alone humans) were perceived as genderless, though. Furthermore, the lack of grammatical masculine or feminine gender did not mean that specific words could not be coded as masculine or feminine (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471; one of my favorite examples are the two etymologically unrelated words for female and male friends, respectively malag and guli).

While occasionally doubts are expressed regarding the meaning of Inanna’s name, most authors today accept that it can be interpreted as derived from the genitive construct nin-an-ak - “lady of heaven” (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 104). The title nin is effectively gender neutral (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 6) - it occurs in names of male deities (Ningirsu, Ninurta, Ninazu, Ninagal, Nindara, Ningublaga...), female ones (Ninisina, Ninkarrak, Ninlil, Nineigara, Ninmug…), deities whose gender shifted or varied from place to place or from period to period (Ninsikila, Ninshubur, Ninsianna…) and deities whose gender cannot be established due to scarcity of evidence (mostly Early Dynastic oddities whose names cannot even be properly transcribed). However, we can be sure that Inanna’s name was regarded as feminine based on its Emesal form, Gašananna (Timothy D. Leonard, Ištar in Ḫatti: The Disambiguation of Šavoška and Associated Deities in Hittite Scribal Practice, p. 36).

The matter is a bit more complex when it comes to the Akkadian name Ishtar. In contrast with Sumerian, Akkadian, which belongs to the eastern branch of the family of Semitic languages, had two grammatical genders, masculine and feminine, though the gender of nouns wasn’t necessarily reflected in verbal forms, suffixes and so on (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 472-473). In contrast with the name Inanna, the etymology of the Akkadian moniker is less clear. The root has been identified, ˤṯtr, but its meaning is a subject of a heated debate (Aren M. Wilson-Wright, Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation of a Goddess in the Late Bronze Age, p. 22-23; the book is based on the author’s doctoral dissertation, which can be read here). Based on evidence from the languages from the Ethiopian branch of the Semitic family, which offer (distant) cognates, Wilson-Wright suggests it might have originally been an ordinary feminine (but not marked with an expected suffix) noun meaning “star” which then developed into a theonym in multiple languages (Athtart…, p. 21) She tentatively suggests that it might have referred to a specific celestial body (perhaps Venus) due to the existence of a more generic term for “star” in most Semitic languages, which must have developed very early (p. 24). Thus the emergence of Ishtar would essentially parallel the emergence of Shamash, whose name is in origin the ordinary noun for the sun (p. 25). This seems like an elegant solution, but as pointed out by other researchers some of the arguments employed might be shaky, so it’s best to remain cautious about quoting Wilson-Wright’s conclusions as fact, even if they are more sound than some of the older, largely forgotten, proposals (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 40-41).

In addition to uncertainties pertaining to the meaning of the root ˤṯtr, it’s also unclear why the name Ishtar starts with an i in Akkadian, considering cognate names of deities from other cultures fairly consistently start with an a. The early Akkadian form Eštar isn’t a mystery - it reflects a broader pattern of phonetic shifts in this language, and as such requires no separate inquiry, but the subsequent shift from e to i is almost unparalleled. Wilson-Wright suggests that it might have been the result of contamination with Inanna, which seems quite compelling to me given that by the second millennium BCE the names had already been interchangeable for centuries (Athtart…, p. 18).

As for grammatical gender, in Akkadian (as well as in the only other language from the East Semitic branch, Eblaite), the theonym Ishtar lacks a feminine suffix but consistently functions as grammatically feminine nonetheless. I got a somewhat confusing ask recently, which I assume was the result of misinterpretation of this information as applying to the gender of the bearer of the name as opposed to just grammatical gender of the name itself:

Occasional confusion might stem from the fact that in the languages from the West Semitic family (like ex. Ugaritic or Phoenician) there’s no universal pattern - in some of them the situation looks like in Akkadian, in some cognates without the feminine suffix refer to a male deity, furthermore goddesses with names which are cognate but have a feminine suffix (-t; ex. Ugaritic Ashtart) added are attested (Athtart…, p. 16).

In Akkadian a form with a -t suffix (ištart) doesn’t appear as a theonym, only as the generic word, “goddess” - and it seems to have a distinct etymology, with the -t as a leftover from plural ištarātu (Athtart…, p. 18). The oldest instances of a derivative of the theonym Ishtar being used as an ordinary noun, dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), spell it as ištarum, without such a suffix (Goddess in Context…, p. 80). As a side note, it’s worth pointing out that both obsolete vintage translations and dubious sources, chiefly online, are essentially unaware of the existence of any version of this noun, which leads to propagation of incorrect claims about equation of deities (Goddesses in Context…, p. 82).

It has been argued that a further form with the -t suffix, “Ishtarat”, might appear in Early Dynastic texts from Mari, but this might actually be a misreading. This has been originally suggested by Manfred Krebernik all the way back in 1984. He concluded the name seems to actually be ba-sùr-ra-at (Baśśurat; something like “announcer of good news”; Zur Lesung einiger frühdynastischer Inschriften aus Mari, p. 165). Other researchers recently resurrected this proposal (Gianni Marchesi and Nicolo Marchetti, Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, p. 228; accepted by Dominique Charpin in a review of their work as well). I feel it’s important to point out that nothing really suggested that the alleged “Ishtarat” had much to do with Ishtar (or Ashtart, for that matter) in the first place. The closest thing to any theological information in the two brief inscriptions she appears in is that she is listed alongside the personified river ordeal, Id, in one of them. Marchesi and Marchetti suggest they form a couple (Royal Statuary…, p. 228); in absence of other evidence I feel caution is necessary. I’m generally wary of asserting deities who appear together once in an oath, greeting or dedicatory formula are necessarily a couple when there is no supplementary evidence. Steve A. Wiggins illustrated this issue well when he rhetorically asked if we should treat Christian saints the same way, which would lead to quite thrilling conclusions in cases like the numerous churches named jointly after St. Andrew and St. George and so on (A Reassessment of Asherah With Further Considerations of the Goddess, p. 101).

Even without Ishtarat, the Mariote evidence remains quite significant for the current topic, though. There’s a handful of third millennium attestations of a deity sometimes referred to as “male Ishtar” (logographically INANNA.NITA; there’s no ambiguity thanks to the second logogram) in modern publications - mostly from Mari. The problem is that this is most likely a forerunner of Ugaritic Attar, as opposed to a male form of the deity of Uruk/Zabalam/Akkad/you get the idea (Mark S. Smith, The God Athtar in the Ancient Near East and His Place in KTU 1.6 I, esp. p. 629; note that the deity with the epithet Sarbat is, as far as I know, generally identified as female though).

Ultimately there is no strong evidence for Attar being associated with Inanna (his Mesopotamian counterpart in the trilingual list from Ugarit is Lugal-Marada) or even with Ashtart (Smith tentatively proposes the two were associated - The God Athtar.., p. 631 - but more recently in ‛Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts he ruled it out, p. 36-37) so he’s not relevant at all to this topic. Cognate name =/= related deity, least you want to argue Zeus is actually Tyr; the similarly firmly male South Arabian ˤAṯtar is even less relevant (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 13). Smith goes as far as speculating the male cognates might have been a secondary development, which would render them even more irrelevant to this discussion (‛Athtart in Late…, p. 35).

There are also three Old Akkadian names which might refer to a masculine deity based on the form of the other element (Eštar-damqa, “E. is good”, Eštar-muti “E. is my husband”, and Eštar-pāliq, “E. is a harp”), but they’re an outlier and according to Wilson-Wright might be irrelevant for the discussion of the gender of Ishtar and instead refer to a deity with a cognate name from outside Mesopotamia (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 22).

There’s also a possible isolated piece of evidence for a masculine deity with a cognate name in Ebla. Eblaite texts fairly consistently indicate that Inanna’s local counterpart Ašdar was a female deity. In addition to the equivalence between them attested in a lexical list, her main epithet, Labutu (“lioness”) indicates she was a feminine figure. However, Alfonso Archi argues that in a single case the name seems to indicate a god, as they are followed by an otherwise unattested “spouse” (DAM-sù), Datinu (Išḫara and Aštar at Ebla: Some Definitions, p. 16). The logic behind this is unclear to me and no subsequent publications offer any explanations so far. It might be worth noting that the Eblaite pantheon seemingly was able to accommodate two sun deities, one male and one female, so perhaps this is a similar situation.

It should also be noted that the femininity of Ishtar despite the lack of a feminine suffix in her name is not entirely unparalleled - in addition to Ebla, in areas like the Middle Euphrates deities with cognate names without the -t suffix might not necessarily be masculine, even when they start with a- and not i- like in Akkadian. In some cases the matter cannot be solved at all - there is no evidence regarding the gender of Aštar of the Stars (aš-tar MUL) from Emar, for instance. Meanwhile Aštar of Ḫaši and Aštar-ṣarbat (“poplar Aštar”) from the same site are evidently feminine (Athtart. The Transmission and Transformation…, p. 106). At least in the last case that’s because the name actually goes back to the Akkadian form, though (p. 85).

To sum up: despite some minor uncertainties pertaining to the Akkadian name, there’s no strong reason to suspect that any greater degree of ambiguity is built into either Inanna or Ishtar - at least as far as the names alone go. The latter was even seen as sufficiently feminine coded to serve as the basis for a generic designation of goddesses.

Obviously, there is more to a deity than just the sum of the meanings of their names. For this reason, to properly evaluate what was up with Inanna’s gender it will be necessary to look into her three main roles: these of a war deity, personification of Venus and love deity.

Masculinity, heroism and maledictory genderbening: the warlike Inanna

An Old Babylonian plaque depicting armed Inanna (wikimedia commons)

Martial first, marital second?

War and other related affairs will be the first sphere of Inanna’s activity I’ll look into, since it feels like it’s the one least acknowledged online and in various questionable publications. Ilona Zsolnay points out that this even extends to serious scholarship to a degree, and that as a result her military side is arguably understudied (Ištar, Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions, p. 389). The oldest direct evidence for the warlike role of Inanna are Early Dynastic theophoric names such as Inanna-ursag, “Inanna is a warrior”. Further examples are provided by a variety of both Sumerian and Akkadian sources from across the second half of the third millennium BCE. This means it’s actually slightly older than the first evidence for an association with love and eroticism, which can only be dated with certainty to the Old Akkadian period when it is directly mentioned for the first time, specifically in love incantations (Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Inanna and Ishtar in the Babylonian World, p. 336).

Deities associated with combat were anything but uncommon in Mesopotamia. There was no singular war god - Ninurta, Nergal, Zababa, Ilaba, Tishpak and an entire host of other figures, some recognized all across the region, some limited to one specific area or even just a single city, shared a warlike disposition. Naturally, the details could vary - Ninurta was essentially an avenger restoring order disturbed by supernatural threats, Nergal was a war god because he was associated with just about anything pertaining to inflicting death, and so on.

All the examples I’ve listed are male, but similar roles are also attested for multiple goddesses, not just Inanna. Those include closely related deities like Annunitum or Belet-ekallim, most of her foreign counterparts, the astral deity Ninisanna (more on this figure later), but also firmly independent examples like Ninisina and the Middle Euphrates slash Ugaritic Anat (Ilona Zsolnay, Do Divine Structures of Gender Mirror Mortal Structures of Gender?, p. 114).

The god list An = Anum preserves a whole series of epithets affirming Inanna’s warlike character - Ninugnim, “lady of the army”; Ninšenšena, “lady of battle”; Ninmea, “lady of combat”; Ninintena, “lady of warriorhood” (tablet IV, lines 20-23; Wilfred G. Lambert and Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p.162). It is also well represented in literary texts. She is a “destroyer of lands” (kurgulgul) in Ninmesharra, for instance (Markham J. Geller, The Free Library Inanna Prism Reconsidered, p. 93).

At least some of the terms employed to describe Inanna in other literary compositions were strongly masculine-coded, if not outright masculine. The poem Agušaya characterizes her as possessing “manliness” (zikrūtu) and “heroism” (eṭlūtu; this word can also refer to youthful masculinity, see Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471) and calls her a “hero” (qurādu). Another example, a hymn dated to the reign of Third Dynasty of Ur or First Dynasty of Isin opens with an incredibly memorable line - “O returning manly hero, Inanna the lady (...)” (or, to follow Thorkild Jacobsen’s older translation, which involves some gap filling - “O you Amazon, queen—from days of yore, paladin, hero, soldier”; The Free Library… p. 93).

A little bit of context is necessary here: while “heroism” might seem neutral to at least some modern readers, in ancient Mesopotamia it was seen as a masculine trait (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 392-393). It’s worth noting that eṭlūtum, which you’ve seen translated as “heroism” above can be translated in other context as “youthful masculinity” (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471). On the other hand, while zikrūtu is derived from zikāru, “male”, it might refer both straightforwardly to masculinity and more abstractly to heroism (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 397).

However, the same hymn which calls Inanna a “manly hero” refers to her with a variety of feminine titles like nugig. There’s even an Emesal gašan (“lady”) in there, you really can’t get much more feminine than that (The Free Library… p. 89). On top of that, about a half of the composition is a fairly standard Dumuzi romance routine (The Free Library… p. 90-91; more on what that entails later, for now it will suffice to say that not gender nonconformity).

This is a recurring pattern, arguably - Agušaya, where masculine traits are attributed to Inanna over and over again, still firmly refers to her as a feminine figure (“daughter”, “goddess”, “queen”, “princess”, “mistress”, “lioness” and so on; Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: an Anthology of Akkadian Literature, p. 160 and passim). In other words, the assignment of a clearly masculine sphere of activity and titles related to it doesn’t really mean Inanna is not presented as feminine in the same compositions.

How to explain this phenomenon? In Mesopotamian thought both femininity and masculinity were understood as me, ie. divinely ordained principles regulating the functioning of the cosmos. In modern terms, these labels as they were used in literary texts arguably had more to do with gender and gender roles than strictly speaking with biological sex (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 391-392). Ilona Zsolnay on this basis concludes that Inanna, while demonstrably regarded as a feminine figure, took on a masculine role in military context (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 401). This is hardly an uncommon view in scholarship (The Free Library…, p. 93; On Language…, p. 243).

In other words, it can be argued that when the lyrical voice in Agušaya declares that “there is a certain hero, she is unique” (i-ba-aš-ši iš-ta-ta qú-ra-du; Before the Muses…, p. 98) the unique quality is, essentially, that Inanna fulfills a strongly masculine coded role - that of a “hero”, understood as a youthful, aggressive masculine figure - despite being female.

It should be noted that the ideal image of a person characterized by youthful masculinity went beyond just warfare, or abstract heroic adventures, though. The Song of the Hoe indicates that willingness to perform manual work in the fields was yet another aspect of it (Ilona Zsolnay, Gender and Sexuality: Ancient Near East, p. 277). This, as far as I know, was never attributed to Inanna.

Furthermore, the sort of youthful, aggressive masculinity we’re talking about here was regarded as something fleeting and temporary for the most part (at least when it came to humans; deities are obviously a very different story), and a very different image of male gender roles emerges from texts such as Instruction of Shuruppak, which extol a peaceful, reserved demeanor and the ability to provide for one’s family as masculine virtues instead (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 277-278). It might be worth pointing out that Sumerian outright uses two different terms to designate “youthful” (namguruš) and “senior” (namabba) masculinity (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 275); the general term for masculinity, namnitah, is incredibly rare in comparison (Gender and Sexuality…, p. 276-277).

It needs to be pointed out that a further Sumerian term sometimes translated as “manliness” - šul, which occurs for example in the hymn mentioned above - might actually be gender neutral; in addition to being used to describe mortal young men and Inanna, it was also applied as an epithet to the goddess Bau, who demonstrably was not regarded as a masculine figure; she didn’t even share Inanna’s warlike character (Analyzing Constructs…, p. 471). Perhaps the original nuance simply escapes us - could it be that šul was not strictly speaking masculinity, but some more abstract quality which was simply more commonly associated with men?

In any case, it’s hard to argue that Inanna really encompasses the entire concept of masculinity as the Mesopotamians understood it. At the same time, it is impossible to deny that she was portrayed as responsible for - and enthusiastically engaged in - spheres of activity which were seen as firmly masculine, and could accordingly be described with terms associated with them. Therefore, it would be more than suitable to describe her as gender nonconforming - at least when she was specifically portrayed as warlike.

Perhaps Dennis Pardee was onto something when he completely sincerely described Anat, who despite being firmly a female figure similarly engaged in masculine pursuits (not only war, but also hunting) as a “tomboy goddess” (Ritual and Cult at Ugarit, p. 274).

These observations only remain firmly correct as long as we assume that gender roles are a concept fully applicable to deities, of course - I’ll explore in more detail later whether this was necessarily true.

Royal curses and legal loopholes

A different side of Inanna as a war deity which nonetheless still has a lot to do with the topic of this article comes to the fore in curse formulas from royal inscriptions. Their contents are not quite as straightforward as imploring her to personally intervene on the battlefield. Rather, she was supposed to make the enemy unable to partake in warfare properly (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 390). Investigating how this process was imagined will shed additional light on how the Mesopotamians viewed masculinity, and especially the intersection between masculinity and military affairs.

The formulas under discussion start to appear in the second half of the second millennium BCE, with the earliest example identified in an inscription of the Middle Assyrian king Tukultī-Ninurta I (Gina Konstantopoulos, My Men Have Become Women, and My Women Men: Gender, Identity, and Cursing in Mesopotamia, p. 363). He implored the goddess to punish his enemies by turning them into women (zikrūssu sinnisāniš) - or rather, by turning their masculinity into femininity, or at the very least some sort of non-masculine quality. The first option was the conventional translation for a while, but sinništu would be used instead of the much more uncommon sinnišānu if it was that straightforward. Interpreting it as “femininity” would parallel the use of zikrūti, “masculinity”, in place of zikaru, “man”.

There are two further possible alternatives, which I find less plausible myself, but which nonetheless need to be discussed. One is that sinnišānu designated a specific class of women. Furthermore, there is also some evidence - lexical list entry from ḪAR.GUD, to be specific - that sinnisānu might have been a synonym of assinnu, a type of undeniably AMAB, but possibly gender nonconforming, cultic performer (in older literature erroneously translated as “eunuch” despite lack of evidence; the second most beloved vintage baseless translation for any cultic terms after “sacred prostitute”, an invention of Herodotus), in which case the curse would involve something like “changing his masculinity in the manner of a sinnisānu” (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 394-396). However, Zsolnay herself subsequently published a detailed study of the assinnu, The Misconstrued Role of the assinnu in Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy, which casts her earlier proposal into doubt, as the perception of the assinnu as a figure lacking conventional masculinity might be erroneous. I’ll return to this point later. For now, it will suffice to say that on grammatical grounds and due to parallels in other similar maledictions, “masculinity into femininity” seems to be the most straightforward to me in this case.

The “genderbending” tends to be mentioned alongside the destruction of one’s weapons (My Men Have…, p. 363). This is not accidental - martial prowess, “heroism” and even the ability to bear weapons were quintessential masculine qualities; a man deprived of his masculinity would inevitably be unable to possess them. The masculine coding of weaponry was so strong that an erection could be metaphorically compared to drawing a bow (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 395).

Zsolnay points out the reversal of gender in curses is also coupled with other reversals: Inanna is also supposed to “establish” (liškun) the defeat (abikti) of the target of the curses - a future king who fails to uphold his duties - which constitutes a reversal of an idiom common in royal inscriptions celebrating victory (abikti iškun). The potential monarch will also be unable to face the enemy as a result of her intervention - yet again a reversal of a mainstay of royal declarations. The majesty and heroism of a king were supposed to scare enemies, who would inevitably prostrate themselves when faced by him on the battlefield (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 396-397).

It is safe to say the goal of invoking Inanna in the discussed formulas was to render the target powerless. (Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 396; My Men Have…, p. 366). Furthermore, they evoke a fear widespread in cuneiform sources, that of the loss of potency, which sometimes took forms akin to Koro syndrome or the infamous penis theft passages from Malleus Maleficarum (My Men Have…, p. 367). It is worth noting that male impotence could specifically be described as being “like a woman” (kīma sinništi/GIM SAL; Ištar, Goddess of War…, p. 395).

Gina Konstantopoulos argues that references to Inanna “genderbening” others occur in a different context in a variety of literary texts, for example in the Epic of Erra, where they’re only meant to highlight the extent of her supernatural ability. She also suggests that more general references to swapping left and right sides around, for example in Enki and the World Order, are further examples, as they “echo(...) the language of birth incantations” which ritually assigned the gender role to a child (My Men Have…, p. 368). She also sees the passage from the Epic of Gilgamesh describing the fates of various individuals who crossed her path and ended up transformed into animals as a result as a more distant parallel of the curse formulas (My Men Have…, p. 369). However, it needs to be pointed out this sort of shapeshifting is almost unparalleled in Mesopotamian literature (Frans Wiggermann, Hybrid creatures A. Philological. In Mesopotamia, p. 237), and none of the few examples involve a change of gender. The fact that the "genderbending" passages generally reflect a fear of loss of agency (especially on the battlefield) or potency, and by extension of independence tied to masculine gender roles, explains why they virtually never describe the opposite scenario, a mortal woman being placed in a masculine role through supernatural means as punishment (My Men Have…, p. 370). It might be worth pointing out that a long sequence of seemingly contradictory duties involving reversals is also ascribed to Inanna in a particularly complex Old Babylonian hymn (Michael P. Streck, Nathan Wasserman, The Man is Like a Woman, the Maiden is a Young Man. A new edition of Ištar-Louvre (Tab. I-II), p. 2-3). It also contains a rare case of bestowing masculine qualities upon women: “the man is like a woman, the maiden is like a young man” (zikrum sinništeš ardatu eṭel; The Man is Like…, p. 5). However, the context is not identical to the “genderbening” curses. The text is agreed to describe a performance during a specific festival. Other passages explicitly refer to crossdressing and rituals themed around reversal (šubalkutma šipru, "behavior is turned upside down"; The Man is Like…, p. 6). Furthermore, grammatical forms of verbs do not indicate a full reversal of gender (The Man is Like…, p. 31). Overall, I agree with Timothy D. Leonard’s cautious remark that in this context only religiously motivated temporary reversal of gender roles occurs, and we cannot use the passage to make far reaching conclusions about the participants’ identity (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 298).

It’s important to bear in mind that a performance involving crossdressing won’t necessarily involve people who are otherwise gender nonconforming, and it doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the sexuality of the performer. While I typically avoid bringing up parallels from other cultures and time periods as evidence, I feel like this is illustrated quite well by the case of shirabyōshi, a type of female performer popular in Japan roughly from the second half of the Heian period to the late Kamakura period.

A 20th century depiction of a shirabyōshi (wikimedia commons)

They performed essentially in male formal wear, and with swords at their waists; their performance was outright called a “male dance” (Roberta Strippoli, Dancer, Nun, Ghost, Goddess. The Legend of Giō and Hotoke in Japanese Literature, Theater, Visual Arts, and Cultural Heritage, p. 28). Genpei jōsuiki nonetheless states that famous shirabyōshi were essentially the Japanese answer to the most famous historical Chinese beauties like Wang Zhaojun or Yang Guifei (Dancer, Nun…, p. 27-28). In other words, while the shirabyōshi crossdressed, they were simultaneously held to be paragons of femininity.

Putting crossdressing aside, it’s worth noting women taking masculine roles are additionally attested in legal context in ancient Mesopotamia, though only in an incredibly specific scenario. A man who lacked male heirs could essentially legally declare his daughter a son, so that she would be able to have the privileges as a man would with regards to inheritance. For example, in a text from Emar a certain mr. Aḫu-ṭāb formally made his daughter Alnašuwa his heir due to having no other descendants, and explained that as a result she will have to be “both male and female” (NITA ù MUNUS) - effectively both a son and a daughter - to keep the process legitimate. Once Alnašuwa got married, her newfound status as a son of her father was legally transferred to her husband, though. Evidently no supernatural powers were involved at any stage, only an uncommon, but fully legitimate, legal procedure (My Men Have…, p. 370-372). It should be noted that when male by proxy, Alnašuwa was explicitly not expected to perform any military roles - her father only placed such an exception on potential grandsons (My Men Have…, p. 370). Therefore, the temporary masculine role she was granted was arguably not the same as the sort of masculinity curses were supposed to take away, or the sort Inanna could claim for herself to a degree.

Luminous beards and genderfluid planets: the astral Inanna (and her peers)

A standard Mesopotamian depiction of the planet Venus (Dilbat) on a late Kassite boundary stone (wikimedia commons)

Male in the morning, female in the evening (or the other way round)?

While the inquiry into Inanna’s military aspect revealed a fair amount of evidence for gender nonconformity, it would be disingenuous on my part to end the article on just that. A slightly different phenomenon is documented with regards to her astral side - or perhaps with regards to the astral side of multiple deities, to be more precise.

To begin with, in Mesopotamian astrology Venus (Dilbat) was one of the two astral bodies which were described as possessing two genders, the other being Mercury (Erica Reiner, Astral Magic in Babylonia, p. 6; interestingly, it doesn’t seem any deity associated with Mercury acquired this characteristic unless you want to count a possible late case from outside Mesopotamia). The primary sources indicate that this reflected the fact Venus is both the morning star and the evening star, though there was no agreement between ancient astronomers which one of them was feminine and which masculine (Ulla Koch-Westenholz, Mesopotamian Astrology. An Introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian Celestial Divination, p. 40). We even have a case of a single astrologer, a certain Nabû-ahhe-eriba, alternating between both options in his personal letters (p. 126). It needs to be pointed out that while some interest in stars and planets might already be attested in Early Dynastic sources, its scope was evidently quite limited and astrology didn’t develop yet (Mesopotamian Astrology…, p. 32). No astrological texts predate the Old Babylonian period, and most of the early ones are preoccupied with the moon (p. 36-37), though the earliest evidence for astrological interest in Venus are roughly contemporary with them (p. 40). Astronomical observations of this planet were certainly already conducted for divinatory purposes during the reign of Ammisaduqa, and by the seventh century BCE experts were well familiar with its cycle and made predictions on this basis (p. 126).

Inanna’s association with Venus predates the dawn of astrology by well over a millennium. It likely goes back all the way up to the Uruk period - if not earlier, but that sort of speculation is moot because you can’t talk about Mesopotamian theology with no textual sources, and these are fundamentally not something available before the advent of writing. The earliest evidence are archaic administrative texts which separately record offerings for Inanna hud, “Inanna the morning” and Inanna sig, “Inanna the evening” (Inanna and Ishtar…, p. 334-335). However, it is impossible to tell if this was already reflected in any sort of ambiguity or fluidity of gender. It also needs to be noted the archaic text records two more epithets, Inanna NUN, possibly “princely Inanna” (p. 334; this is actually the single oldest one) and Inanna KUR, possibly a forerunner of later title ninkurkurra, “lady of the lands” (p. 335). Therefore, Inanna was arguably already more than just a deity associated with Venus.

It’s up for debate to which degree an astral body was seen as identical with the corresponding deity in later periods (Spencer J. Allen, The Splintered Divine. A Study of Ištar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East, p. 41-42). There is evidence that Inanna and the planet Venus could be viewed as separate, similarly to how the moon observed in the sky could be treated as distinct from the moon god Sin (p. 40). The most commonly cited piece of evidence is that astrological texts fairly consistently employ the name Dilbat to refer to the planet instead of Inanna’s name or one of the logograms used to represent it, like the numeral 15 (p. 42).

Regardless of these concerns, one specific tidbit pertaining to astrological comments on Venus is held as particularly important for possible ambiguity or fluidity of Inanna’s gender, and even lead to arguments that masculine depictions might be out there: the planet can be described as bearded (Astral Magic…, p. 6). Omens attesting this are most notably listed in the compendium Iqqur īpuš (Erica Reiner, David Pingree, Babylonian Planetary Omens vol. 3, p. 10-11). it should be noted that the planet is referred to only as Dilbat in this context (see ex. Babylonian Planetary…, p. 105 for an example). I’m only aware of two texts where this feature is transferred to the corresponding deity: the syncretic hymn to Nanaya and Ashurbanipal’s hymn to Ishtar of Nineveh. Is the beard really a beard, though? Not necessarily, as it turns out.

The passage from the hymn of Ashurbanipal has been recently discussed by Takayoshi M. Oshima and Alison Acker Gruseke (She Walks in Beauty: an Iconographic Study of the Goddess in a Nimbus, p. 62-63). They point out that ultimately there are no certain iconographic representations of bearded Ishtar. There are a few proposed ones on cylinder seals but this is a minority position relying on doubtful exegesis of every strand of hair in sight; no example has anything resembling the “classic” Mesopotamian beard. I’ll return to this problem in a bit.

In any case, the authors of the aforementioned paper argue the key to interpreting the passage is the fact that the reference to the beard (or rather beards in the plural) occurs in an enumeration of strictly astral, luminous characteristics, like being “clothed in brilliance” (namrīrī ḫalāpu). Furthermore, they identify a parallel in the Great Hymn to Shamash: the rays of the sun are described as “beards” (ziqnāt), and occur in parallel with “splendor” (šalummatu) and “lights” (namrīrū). Therefore, they assume the “beard” might be a metaphorical term for a ray of light, rather than facial hair. This would match actually attested depictions - in the first millennium BCE, especially in Assyria, images of a goddess surrounded by rays of light or a large halo of sorts are very common.

A goddess surrounded by a halo on a Neo-Assyrian seal (wikimedia commons)

Perhaps most importantly, this interpretation is also confirmed by the astronomical texts which kickstarted the discussion. The phrase ziqna zaqānu, “to have a beard”, is explained multiple times as reflection of an unusual luminosity when applied to Venus. The authors additionally argue that it is possible the use of the term “beard” was originally tied to the triangular portions of the emblems of Inanna and her twin (which indeed represent the luminosity of Venus and the sun) to explain why a plurality of “beards” is relatively common in the discussed descriptions (p. 64).

As I said before, the second example is a hymn to Nanaya. It’s easily one of my favorite works of Mesopotamian literature, and a few years ago it kickstarted my interest in its “protagonist”, but tragically most of it is completely irrelevant to this article. The gist of it is fairly simple: the entire composition is written in first person, and in each strophe Nanaya claims the prerogatives of another deity before reasserting herself: “still I am Nanaya” (Goddesses in Context…, p. 116-117). The “borrowed” attributes vary from abstract cosmic powers to breast size. The deities they are linked with range from the most major members of the pantheon (Inanna, Gula, Ishara, Bau…) through spouses of major deities (Shala, Damkina…) to obscure oddities (Manzat, the personified rainbow); there’s even one who’s otherwise entirely unknown, Šuluḫḫītum (for a full table see Erica Reiner’s A Sumero-Akkadian Hymn of Nanâ, p. 232).

As expected, the strophe relevant to the current topic is the one focused on Inanna, in which Nanaya proudly exclaims “I have a beard (ziqna zaqānu) in Babylon”, in between claiming to have “heavy breasts in Daduni” (Reiner notes this is not actually an attested attribute of Inanna, and suggests the line might be a pun on the name of the city mentioned in it, Daduni, and the word dādu) and appropriating Inanna’s family tree for herself (A Sumero-Akkadian…, p. 233).

A possible late depiction of Nanaya (wikimedia commons)

It needs to be stressed that Nanaya’s gender shows no signs of ambiguity anywhere; quite the opposite, she was the “quintessence of womanhood“ (Olga Drewnowska-Rymarz, Mesopotamian Goddess Nanāja, p. 156). I would argue the most notable case of something along the lines of gender nonconformity in a source focused on her occurs in the sole known example of a love poem starring her and her sparsely attested Old Babylonian spouse Muati.

Muati is asked to intercede with Nanaya on behalf of a petitioner (Before the Muses…, p. 160), which usually was the role performed of the wife of a major male deity (or by Ninshubur in Inanna’s case; Goddesses in Context…, p. 273). Sadly, despite recently surveying most publications mentioning Muati I haven’t found any substantial discussion of this unique passage, and I’m not aware of any parallels involving other couples where the wife was a more important deity than the husband (like Ninisina and Pabilsag).

A further issue for the beard passage is that Nanaya had no connection to Venus to speak of - she could be described as luminous, but she was only compared to the sun, the moon, and unspecified stars (Mesopotamian Goddess Nanāja, p. 153-155).

Given that the hymn most likely dates to the early first millennium BCE (Goddesses in Context…, p. 116), yet another problem for the older interpretation is that the city of Babylon at this point in time is probably the single worst place for seeking any sort of gender ambiguity when it comes to Inanna.

After the end of the Kassite period, Babylon became the epicenter of Marduk-centric theological ventures which famously culminated in the composition of Enuma Elish. What is less well known is that as a part of the same process, attempts were made to essentially fuse Bēlet-Bābili (“lady of Babylon”) - the main (but not only) local form of Inanna, regarded as distinct from Inanna of Uruk (the “default” Inanna) - with Zarpanitu (The Pantheon…, p. 75-76). Zarpanitu was effectively the definition of an indistinct spouse of another deity - there’s not much to say about her character other than that she was Marduk’s wife (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92-93). Accordingly, it is hard to imagine that the contemporary “lady of Babylon” would be portrayed as bearded.

During the reign of Nabu-shuma-ishkun in the eighth century BCE an attempt to extend the new dogma to Inanna of Uruk was made, though this was evidently considered too much for contemporary audiences. Multiple sources display varying degrees of opposition to replacement of Inanna in the Eanna by a goddess who didn’t belong there, presumably either Zarpanitu or at the very least Bēlet-Bābili after “Zarpanituification” so severe she no longer bore a sufficient resemblance to her Urukuean colleague (The Pantheon…, p. 76-77). Inanna of Uruk was restored during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, who curiously affirmed that her temple was temporarily turned into the sanctuary of an “inappropriate goddess” (The Pantheon…, p. 131). However, the Marduk-centric ventures left a lasting negative impression in Uruk nonetheless, and in the long run lead to quite extreme reactions, culminating in the establishment of an active cult of Anu for the first time, but that’s another story (I might consider covering it in detail if there’s interest).

To go back to the hymn to Nanaya one last time, it’s interesting to note that a single copy seems to substitute ziqna zaqānu for zik-ra-[...], possibly a leftover of zikrāku, “manly”. Takayoshi M. Oshima and Alison Acker Gruseke presume this is only a scribal mistake, since this heavily damaged exemplar is rife with typos in general (She Walks…, p. 63), though I’m curious if perhaps a reference to the military character of Inanna herself or Annunitum was meant. This would line up with evidence from Babylon to a certain degree, since through the first millennium BCE Annunitum was worshiped there in her own temple (Goddesses in Context…, p. 105-106). However, in the light of what is known about this unique variant, it’s best to assume that it is indeed a typo and the hymn simply refers to luminosity.

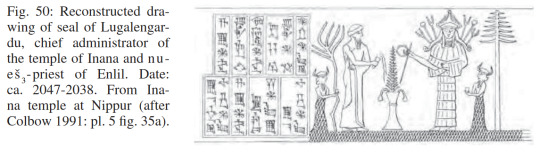

While no textual sources earlier (or later, for that matter) than the two hymns discussed above attribute a beard to Inanna (Zainab Bahrani, Women of Babylon. Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia, p. 182), the most commonly cited example of a seal with a supposedly bearded depiction is considerably earlier (Ur III, so roughly 2100 BCE, long before any references to “bearded Venus”). It comes from the Umma area judging from the name and title of its owner, a certain Lu-Igalima, a lumaḫ priest of Ninibgal (“lady of the [temple] Ibgal”, ie. Inanna’s temple in Umma). However, Julia M. Asher-Greve points out that the beard is likely to be a strand of hair, since contemporary parallels supporting this interpretation are available, for example a seal of a priest of Inanna from Nippur, Lugalengardu. Furthermore, she notes that the seal cutter was seemingly inexperienced, since the detail is all around dodgy, for example Inanna’s foot seems to be merged with the head of the lion she stands on (Goddesses in Context…, p. 208). Looking at the two images side by side, I think this is a compelling argument, since the beard doesn’t really look like, well, a typical Mesopotamian beard, while the hairdo on the Nippur seal is indeed similar:

Both images are screencaps from Goddesses in Context, p. 403; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

While I think the beard-critical arguments are sound, this is not the only possible kind of depiction of Inanna argued to reflect the fluidity of gender attributed to the planet Venus.

Paul-Alain Beaulieu notes that an inscription of Nebuchadnezzar with a dedication to Inanna of Uruk she might be called both the lamassu, ie. “protective goddess”, of Uruk and šēdu, ie. “protective genius”, of Eanna; the latter is an invariably masculine term. However, it is not entirely clear if the lamassu and šēdu invoked here are both really a partially masculine Ishtar, since there’s a degree of ambiguity involved in the concept of protective deity or deities of a temple - while there’s evidence for outright identification with the main deity of a given house of worship, they could also be separate, though closely related, and Beaulieu ultimately remains uncertain which option is more plausible here (The Pantheon…, p. 137-138). He also points out that there’s some late evidence for apotropaic figures with two faces, male and female, which were supposed to represent a šēdu+lamassu pair, but rules out the possibility that these have anything to do with Ishtar, since two faces are virtually never her attribute (The Pantheon…, p. 137). There is a single possible exception from this rule, but it’s an outlier so puzzling it’s hard to count it. A single Neo-Assyrian text from Nineveh (KAR 307) describes Ishtar of Nineveh (there is a reason why I abstain from using the name Inanna here, as you’ll see later) as four-eyed, which Beaulieu suggests might mean the deity had a male face and a female face. The same source also states that Ishtar of Nineveh is Tiamat and has “upper parts of Bel” and “lower parts of Ninlil”, though (The Pantheon…, p. 137), so it’s probably best not to think of it too much - Tiamat is demonstrably not a figure of much importance in general, let alone in the context of Inanna-centric considerations.

The same text has been interpreted differently by Wilfred G. Lambert. He concludes that it’s ultimately probably an esoteric Enuma Elish commentary and that it might have been cobbled together by a scribe from snippers of unrelated, contradictory sources (Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 245). If correct, this would disprove Beaulieu’s proposal, since the four eyes would simply reflect the description of Marduk (Bel) in EE (tablet I, line 55: “Four were his eyes, four his ears”). I lean towards Lambert’s interpretation myself; the reference to Tiamat is the strongest argument, outside EE and derived commentaries she was basically a non-entity. I’ll go back to the topic of Ishtar of Nineveh later, though - there is a slim possibility that two faces might really be meant, though this would take us further away from Inanna, all the way up to ancient Anatolia.

As a final curiosity it’s worth pointing out that while this is entirely unrelated to the discussed matter, KAR 307 is also the same text which (in)famously states Tiamat has the form of a dromedary. As odd as that sounds, it’s much easier to explain when you realize that the Akkadian term for this animal, when broken down to individual logograms, could be interpreted as “donkey of the sea” - and Tiamat’s name was derived from the ordinary Akkadian word “sea” (Babylonian Creation…, p. 246).

The Red Lady of Heaven, my king

While both the bearded and two faced Inannas are likely to be mirages, this doesn’t mean the dual gender of Venus was not reflected in the world of gods. The result was a bit more complex than the existence of a male Inanna, though.

In addition to being Inanna’s astral attribute, Venus simultaneously could be personified under the name Ninsianna. Ninsianna could be treated as a title of Inanna - this is attested for example in a hymn from the reign of Iddin-Dagan of Isin - but unless explicitly stated, should be treated as a separate deity. This is evident especially in sources from Larsa, where the two were worshiped entirely separately from each other (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92).

Ninsianna’s name can be literally translated as “red lady of heaven” (Goddesses in Context…, p. 86), though as I already explained earlier, nin is actually gender neutral - “red lord of heaven” is theoretically equally valid. And, as a matter of fact, it is necessary to employ the latter translation in some cases - an inscription of Rim-Sin I refers to Ninsianna with the firmly masculine title lugal, “king” (Wolfgang Heimpel, Ninsiana, p. 488).

It seems safe to say that in Ninsianna’s case we’re essentially dealing with a deity who truly was like Venus. Timothy D. Leonard stresses that while frequently employed in past scholarship, the labels “hermaphroditic” and “androgynous” do not describe the phenomenon accurately. What the sources actually present is a deity who switches between a male form and a female one (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 226). In other words, if we are to apply a contemporary label, it seems optimal to say Ninsianna was perceived as genderfluid.

Interestingly, though, it seems that Ninsianna’s gender varied by location as well (Goddesses in Context…, p. 92). The worship of feminine Ninsianna is attested for example in Nippur (Goddesses in Context…, p. 101) and Uruk (Goddesses in Context…, p. 126), masculine - in Sippar-Amnanum, Girsu and Ur (Ninsiana, p. 488-489). No study I went through speculated what the reasons behind this situation might have been. Was Ninsianna’s gender locally viewed as less flexible than the discussed theological texts indicate? Were specific sanctuaries dedicated only to a specific aspect of this deity - only the “morning” Ninsianna or “evening” Ninsianna? For the time being these questions must remain unanswered in most cases.

There’s a single case where the preference for feminine Ninsianna was probably influenced by an unparalleled haphazard theological innovation, though - in Isin in the early second millennium BCE the local dynasty lost control over Uruk, and as a result access to royal legitimacy granted symbolically by Inanna. To remedy that, the tutelary goddess of their capital was furnished with similar qualifications through a leap of logic relying on one hand on the close association between Inanna and Ninsianna, and on the other on the phonetic (but not etymological) similarity between the names of Ninisina and Ninsianna (Goddesses in Context…, p. 86). As far as I know, this did not influence the perception of Ninisina’s gender in any shape or form, though.

An interesting extension of the phenomenon of Ninsianna’s gender is this deity’s association with an even more enigmatic figure, Kabta. Only two things can be established about Kabta with certainty: that they were an astral deity, and that they were associated in some way with Ninsianna; even their gender is uncertain (Wilfred G. Lambert, Kabta, p. 284).

It might be worth pointing out that as a result Kabta and Ninsianna seem to constitute the first case of a Mesopotamian deity of variable (Ninsianna) or uncertain (Kabta) gender being referred to with a neutral pronoun in an Assyriological publication - Ryan D. Winters’ commentary on their entries in a variety of god lists employs a singular they (An = Anum…, p. 34):

Wilfred G. Lambert argued that the two were spouses (Kabta, p. 284). More recently the same point has been made by Winters based on Kabta’s placement after Ninsianna in An = Anum, and directly before Dumuzi in an Old Babylonian forerunner of this list (An = Anum…, p. 22). However, I feel obliged to point out that An = Anum, which fairly consistently identifies spouses as such, does not actually specify the nature of the connection between the two. Once the enumeration of Ninsianna’s names finishes, the list simply switches to Kabta’s (An = Anum…, p. 170).

In another god list, which is rather uncreatively referred to as “shorter An = Anum” due to sharing the first line with its more famous “relative” but lacking its sheer scope, names of Kabta are listed among designations for Inanna’s astral forms, which would have interesting implications for the nature of the supposed relationship between them and Ninsianna (An = Anum…, p. 34). Furthermore, as noted by Jeremiah Peterson, both of them, as well as Kabta’s alternate name Maḫdianna and a further astral deity, Timua, are also glossed as Ištar kakkabi - in this case according to him likely a generic moniker “goddess of the star” as opposed to “Ishtar of the star” - in a variety of lexical lists (God Lists from Old Babylonian Nippur, p. 58).

In the light of the somewhat confusing evidence summarized above, further inquiries into both Kabta’s character and the nature of the connection between them and Ninsianna are definitely necessary. Assuming that they were spouses, how did theologians who adhered to this view deal with them also being treated as two manifestations of one being instead (I suppose you could easily put a romantic spin on that, to be fair)? Did Kabta’s gender change alongside Ninsianna’s, or perhaps following a different scheme, or was this a characteristic they lacked? Unless new sources emerge, this sadly must remain the domain of speculation.

Ninsianna’s fluid gender also has to be taken into account while discussing one further deity, Pinikir. The discovery of a fragmentary god list in Emar made it possible to establish the latter was regarded as the Hurrian equivalent of the former (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 224; note that there seems to be a typo here, the list is identified as An = Anum but it’s actually the Weidner god list). This deity similarly was understood as a personification of Venus (Piotr Taracha, Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia, p. 99) and was in a certain capacity associated with Inanna - however, as it will become evident pretty quickly these weren’t the only analogies with Ninsianna.

Despite appearing in Emar in Hurrian context, Pinikir actually originated to the east of Mesopotamia, in Elam (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 223). Her name cannot yet be fully explained due to imperfect understanding of Elamite, but it is clear that the suffix -kir is feminine and means “goddess” (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 237; cf. the not particularly creatively named Kiririsha, “great goddess”). Sources from Anatolia recognize Pinikir as an Elamite deity, though direct transfer from one end of the “cuneiform world” to the other is unlikely (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 236). Most likely, Hurrians received Pinikir through Mesopotamian intermediaries in the late third or early second millennium BCE, and later introduced this deity further west (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 237). We know Mesopotamians were aware of her thanks to the god list Anšar = Anum, where the name occurs among what may or may not be an enumeration of deities regarded as Inanna’s foreign counterparts (An = Anum…, p. 36). For the time being it is not possible to track this process directly, though - it’s all educated guesswork.

While as far as I am aware none of the few Elamite sources dealing with Pinikir provide much theological information about her, and none hint at her gender being anything but feminine, Hurro-Hittite texts from Anatolia indicate that at least in this context, like Ninsianna in Mesopotamia, she came to be seen as a genderfluid deity, sometimes counted among gods, sometimes among goddesses (Gary Beckman, The Goddess Pirinkir and her Ritual from Ḫattuša (CTH 644), p. 25). Firmly feminine Pinikir occurs in a ritual text (KUB 34.102) which refers to her in Hurrian as Allai-Pinikir, “lady Pinikir”; interestingly this is the only case where she is provided with an epithet in any Anatolian source (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 211). However, there are examples of ritual texts where Pinikir is listed among male deities (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 229). He is also depicted in the procession of gods in the famous Yazilikaya sanctuary in a rather striking attire:

I know, I know, the state of preservation leaves much to be desired (wikimedia commons) This isn’t just any masculine clothing - the outfit is only shared with two other figures depicted in this sanctuary, the sun god Shimige and the Hittite king (The Goddess Pirinkir…, p. 25-26):

Shimige (left; wikimedia commons) and the king (right; also wikimedia commons)

Piotr Taracha argues that it reflects the attire worn by the Hittite king when he fulfilled his religious duties (Religions of…, p. 89); Pinikir’s isn’t identical - it’s only knee length, like the more standard masculine garments - but the skullcap is pretty clearly the same. He is also winged, which is a trait only shared with the moon god and one more figure (more on them in a bit), and likely reflects celestial associations (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 211). All the same traits are also preserved on a small figurine of Pinikir from the collection of the MET:

A much better preserved masculine Pinikir (MET)

It’s therefore probably safe to say that the male form had a fairly consistent iconography, which furthermore was patterned on what probably was an archetypal image of masculinity to Hurro-Hittite audiences. The king, whose appearance is reflected in Pinikir’s iconography, was, after all, supposed to be not just any man, but rather the foremost example of idealized masculinity (Mary R. Bachvarova, Wisdom of Former Days: The Manly Hittite King and Foolish Kumarbi, Father of the Gods, p. 83-84).

Since we started this section with beards, we may as well end with them - I feel obliged to point out that no matter how clearly described as masculine, neither Ninsianna nor Pinikir were ever described (let alone depicted) as bearded.

It is difficult for me to estimate to which degree the information about the genderfluidity of Ninsianna and Pinikir can be used to elucidate in which way the association with Venus influenced the perception of Inanna’s gender. However, it seems safe to say the focus on secondary physical characteristics made some authors miss the forest for the trees. I’ll leave it as an open question whether Inanna could be interpreted similarly to her even more Venusian peers, but I’m fairly sure that a metaphorical beard is unlikely to have anything to do with the answer.

Excursus: “the masculinity and femininity of Shaushka”, or when an Ishtar is not Ishtar

Bringing up the masculine Pinikir, and the matter of possible genderfluidity of deities in Mesopotamia and nearby areas, makes it necessary to also discuss Shaushka. The two of them appear mere two lines apart in Anšar = Anum (An = Anum…, p. 36), though they were not closely associated with each other - rather, they were both deities associated with Inanna who happened to belong to the same cultural milieu.

Mx. Worldwide: the transmission of Shaushka across the cuneiform world

Shaushka was originally the tutelary deity of Nineveh, but the attestations span almost the entire “cuneiform world” - from Nineveh in the north to Lagash in the south, from Hattusa in the west, through Ugarit and various inland Syrian cities all the way up to Arrapha in the east. There are simply too many of them to cover everything here.

The oldest known reference to Shaushka (which doubles as the first reference to the city of Nineveh) occurs in a text from the Ur III period. It’s not very thrilling - it’s only an administrative text mentioning the offering of a sheep made on behalf of the king of the Ur III state (Gary Beckman, Ištar of Nineveh Reconsidered, p. 1). The earliest sources render the name as Shausha; the infix -k- which only starts to appear consistently later on is presumed to be an honorific, or less plausibly a diminutive (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 55-56). Either way, it is agreed it can be translated simply as “the great one” (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 56) - a pretty apt description of its bearer.

Ur III attestations of Shaushka are sparse otherwise: a textile offering in Umma (possibly a garment for a statue), a handful of theophoric names like Ur-Shausha and Geme-Shausha in Lagash, and that’s basically it (Tonia Sharlach, Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court, p. 106). Still, it’s probably safe to say it’s one of the examples of a broader pattern of interest in Hurrian religion evident in the courtly documents from this period, and in the appointment of a number of Hurrian diviners to relatively prestigious positions. Whether such experts might have influenced the introduction of Shaushka and other Hurrian deities who entered lower Mesopotamia roughly at the same time (for example Allani from Zimudar or Shuwala from Mardaman) remains an open question (Foreign Influences…, p. 111-114).

A degree of equivalence between Shaushka and Inanna was already recognized in the early second millennium BCE, as evidenced by a tablet from the northern site of Shusharra dated to the reign of Shamshi-Adad which records an offering made to “Ishtar of Nineveh” (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 58). However, it might have happened as early as half a millennium earlier, during the Sargonic period - Gary Beckman suggests the identification between the two might have initially occurred simply due to the importance assigned to Inanna by rulers of the Akkadian Empire (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 2).

Furthermore, a number of later Mesopotamian lexical lists label Shaushka as “Ishtar of Subartu” - a common designation for the core Hurrian areas (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 2). Meanwhile, Hurrians and cultures influenced by them used the name Ishtar as a logogram to represent Shaushka (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 46). Furthermore, they placed Shaushka in Uruk in an adaptation of the Epic of Gilgamesh (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 125). One is forced to wonder if perhaps from the Hurrian interpreter’s perspective Inanna was some sort of foreign Shaushka ersatz, not the other way around.

Despite Shaushka’s origin in the Hurrien milieu of northernmost part of Mesopotamia, the bulk of attestations actually come from Hittite Anatolia (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 2). Kizzuwatna, a kingdom in southeastern Anatolia, was the middleman in this transmission (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 95). The earliest evidence for Hittite reception of Shaushka is an oracle text from either the late fifteenth or early fourteenth century BCE (Ištar in Ḫatti, p. 84). However, save for the capital, Hattusa, no major cities were ever identified as cult centers of this deity, and they were seemingly worshiped largely within the southern and eastern periphery of the Hittite empire (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 94). Most of the ritual texts Shaushka appears in accordingly appear to have Kizzuwatnean, or at least broadly Hurrian, background (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 87).

Is non-astral genderfluidity possible, or what’s up with Shaushka’s gender?

Probably the most fascinating aspect of Shaushka’s character is the apparent coexistence of a female and a male form of this deity. The best known example of this phenomenon are the Yazilikaya reliefs, where a masculine form, with unique attributes including a robe leaving one leg exposed and wings, marches with the gods (with the handmaidens Ninatta and Kulitta - more on them later - in tow) while a caption accompanying a damaged relief indicates a feminine one was originally depicted in the procession of identically depicted goddesses (The Splintered Divine…, p. 75).

Masculine Shaushka (right) accompanied by Ninatta and Kulitta (wikimedia commons)

A restoration of the procession of goddesses, including feminine Shaushka (wikimedia commons)

A number of epithets applied to Shaushka were similarly explicitly feminine, for instance Hurrian “lady of Nineveh” (allai Ninuwawa) and Hittite “woman of that which is repeatedly spoken” (taršikantaš MUNUS-aš), implicity something like “woman of incantations” (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 5); magic was apparently understood as a particular competence of this deity (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 6). There is even a singular case of an incantation being explicitly attributed to Shaushka (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 98).

Literary texts, chiefly myths from the so-called Kumarbi cycle, generally portray Shaushka as feminine too, and more as a love deity (to be precise, as something along the lines of a heroic equivalent of a femme fatale) rather than as a warlike one (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 85). Mary R. Bachvarova tentatively suggests that a reference to possibly masculine Shaushka might be present in the first of its parts, Song of Going Forth (also known as Song of Kumarbi), which mentions a deity of uncertain gender designated by the logogram KA.ZAL, “powerful”, which she argues has the same meaning as Shaushka’s name (Wisdom of Former…; p. 95 for the text itself, p. 106 for commentary). However, I’m not aware of any subsequent studies adopting this view.

Regardless of the contents of the literary texts available to us presently, Shaushka is explicitly counted among male deities in CTH 712. The enumeration in this ritual text also includes the “femininity and masculinity” of this deity. The male form of Pinikir is there too, though without a separate entry dedicated to any of his attributes or characteristics (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 219). Another example might be less direct: two descriptions of depictions of Shaushka use the terms “helmeted” (kurutawant), which referred to headwear worn by gods, as opposed to “veiled” (ḫupitawant), which referred to the typical headwear of goddesses. This lines up with the relief of masculine Shaushka from Yazilikaya (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 300).

A detail I haven’t seen brought up in any discussion of Shaushka’s gender which I personally think might be relevant to this topic is that their name occurs as a theophoric element both in feminine and masculine Hurrian theophoric names, which is otherwise entirely unheard of. Hurrians evidently were more rigid than Mesopotamians when it comes to theophoric elements in given names, as goddesses occur only in names of women and gods in names of men (Gernot Wilhelm, Name, Namengebung D. Bei den Hurritern, p. 125).

Interestingly, Hittite sources pertaining to Shaushka offer a parallel to the “genderbending” curse formulas as well (My Men Have…, p. 363-364; note they are actually slightly earlier than the Assyrian examples). In a few cases, including a prayer and military oaths, this deity is implored to deprive foreign adversaries of the Hittite empire of their masculinity and courage, to take away their weapons, and to make them dress like women (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 90).

How did this aspect of Shaushka’s character develop? I’d assume that in contrast with Ninsianna and Pinikir, the influence of astronomical ideas about Venus can probably be ruled out. Beckman stresses that at least in Anatolian context Shaushka was evidently not an astral deity (Ištar of Nineveh…, p. 7). Timothy D. Leonard argues that the wings, which only the male form possesses, likely reflect a celestial role, but he doesn’t explore the point further (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 211). However, he notes that only Pinikir is explicitly identified with Venus in Hurro-Hittite sources, and presumably fulfilled the role of personification of this astral body alone (p. 225).

Leonard argues that it cannot be established with certainty whether Shaushka was perceived as capable of taking both male and female forms, as existing simultaneously as a male and female deity (with two bodies, presumably), or if they should be regarded as androgynous. However, he notes that there is no evidence for the recognition of any sort of nonbinary identity in known Hittite sources - so at least implicitly, he assumes the gender of both of the forms would need to be binary (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 298).

It needs to be noted that the validity of applying the label “androgynous” to Shaushka has already been questioned all the way back in 1980(!) - in the first detailed study of Shaushka’s character and cult ever published, Ilse Wegner argued that in both visual arts and literary texts they are presented either as feminine or masculine, but never is their gender ambiguous (Gestalt und Kult der Ištar-Šawuška in Kleinasien, p. 47). Frans Wiggermann argues that KAR 307, which I already discussed and which describes a single figure with both masculine and feminine traits, might be related to depictions of Shaushka (Mischwesen A…, p. 237; thus I suppose the text would deal with an Ishtar, not with Inanna slash Ishtar herself) but this would quit obviously at best constitute a late exception which could be attributed to very vague familiarity with the deity.

In addition to the options discussed by Leonard, a further interpretation present in scholarship is possibility is that Shaushka might have been seen primarily as a goddess, but performed a male role in specific context, to be precise when portrayed as a warlike deity (Ištar in Ḫatti…, p. 301) - in other words, that we are dealing with a similar phenomenon as in the case of Inanna. For instance, Wegner assumed Shaushka was essentially female, and the masculine portrayals merely reflect adoption of masculine-coded character traits and attributes as opposed to actual transformation into a male figure (p. 47-48). Gary Beckman similarly suggests that Shaushka was a goddess, and that the male form, which he likewise considers to be a military aspect, was interpreted as crossdressing, as opposed to an actual shift in gender (Shawushka, p. 1). Leonard accepts the possibility that the male form might reflect the fact that warfare was seen as an exclusively masculine pursuit in Anatolia, though since there are multiple sources where goddesses whose gender never shifted in any way appear on the battlefield he stresses it’s not impossible such gender norms did not necessarily apply to deities (Ištar in Ḫatti, p. 299-300).