#Pentameron

Text

Another old sketch for #orctober

Back then I wanted to draw the ogre from the first story of Basile‘s “Tale of Tales” in this pose:

“… where, at the entrance of a pumice cave, sitting on the root of a poplar tree, he found an ogre, and goodness gracious. Was he ugly! His head was larger than an Indian gourd, his forehead full of bumps, his eyebrows united, his eyes crooked, his nose flat, with nostrils like a forge, his mouth like an oven, from which protruded two tusks like unto a boar's ; a hairy breast had he, and arms like reels ; and bandy-legged was he, and flat-footed like a goose; briefly he was an hideous monster, frightful to behold, who would have made a Roland smile, and would have frightened a Scannarebecco ;”

-Giambattista Basile, “The Tale of Tales”, translation based on that of sir Richard Francis Burton

Allora volevo provare a disegnare in questa posizione con la descrizione dell‘orco nella prima fiaba de “Lo cunto de li cunti” di Basile:

“Colà, sulla radice di un pioppo, presso una grotta lavorata di pietra pomice, era seduto un orco: o mamma mia, quanto era brutto! Era nano e sconcio di corpo, aveva il capo più grosso d’una zucca d’india, la fronte bernoccoluta, le soprac- ciglia congiunte, gli occhi stravolti, il naso schiacciato, con due narici che parevano due chiaviche maestre; una bocca quanto un palmento, dalla quale uscivano due zanne che gli giungevano ai malleoli; il petto peloso, le braccia di aspo, le gambe piegate a vòlta, e i piedi larghi di papera. Insomma, pareva un diavolo, un parasacco, un brutto pezzente e una mal’ombra spiccicata, che avrebbe sbigottito un Orlando, atterrito uno Scannarebecco, e fatto cadere in deliquio il più abile schermitore.”

-Giambattista Basile, “Il Pentamerone ossia La Fiaba delle Fiabe”, traduzione di Benedetto Croce

Damals wollte ich versuchen, den Wilden Mann aus Basiles „Märchen der Märchen“ in dieser Position zu zeichnen:

„Hier sah er auf dem Stumpf einer Pappel neben einer Grotte aus Bimsstein einen wilden Mann sitzen. O steh mir bei, wie häßlich sah der aus! Er war ein ganz kleiner Knirps und nicht größer als ein Zwerg; er hatte aber einen Kopf, dicker als ein indischer Kürbis, eine blättrige Stirn, die Augenbrauen zusammengewachsen, verdrehte Augen, eine platte Nase mit zwei Nasenlöchern, die zwei Kloaken schienen, einen Mund so groß wie eine Kelter, aus welchem zwei Hauer hervorragten, die ihm bis an die Fußspitzen gingen, eine zottige Brust, Arme wie eine Garnwinde, Beine wie eine Bogenwölbung und Füße so flach wie die einer Gans; mit einem Wort, er schien ein Popanz, ein Teufel, ein häßliches Fratzengesicht und ein wahres Schreckgespenst, das selbst einen Roland hätte in Angst setzen, einem Achilles den Mut rauben und einen Bettelbruder abschrecken können.„

- Giambattista Basile, „Das Pentameron”, übersetzt von Felix Liebrecht

#orc#orco#ogre#uerco#fairy tales#folk tales#folklore#my artwork#my art#old art#sketch#sketchbook#pentamerone#tale of tales#lo cunto de li cunti#Il racconto dei racconti#Das Märchen der Märchen#Pentameron#wild man#wilder mann#october#orctober

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I have been reblogging and looking back at Sleeping Beauty stuff around the Internet, I realized the thing that is bothering me a bit... When it comes to the you know "original" format of Sleeping Beauty.

Everywhere on the Internet you have these posts and videos and whatnot about "The dark truth behind Sleeping Beauty" or "The Horrifying Origins of Sleeping Beauty!", and they all refer to the fact that in the "original" version of the tale, she got raped in her sleep. This is the "dark fact" everybody LOVES to spread around and talk about. Except... Except the version they refer to is Basile's "Sun, Moon and Thalia".

Why does that matter? I'll explain.

Everybody depicts "Sun, Moon and Thalia" as this sort of dark, horrifying tale of a grim and gruesome crime. They will have in their video a dark background, and creepy illustrations, and they will take an ominous horror movie voice and whatnot.

But there's a big problem with that. Basile's stories were all except serious. They were humoristic tales. Or more precisely, they were farcical stories. Farces. There's a reason its "twin compilation", Straparola's fairytale collection, is called "Facetious Nights". So the very idea of presenting these stories as if they were meant to be taken seriously is completely misreading the story's tone. Yes there was a rape - but if you extract this from the entire context and storytelling, you make this tale sound like something it is absolutely not.

"Sun, Moon and Thalia" is not meant to be a horror story. It was not meant to be read as "serious" story. It has nothing to do with either the Grimm or Perrault fairytales. The entirety of the "Pentamerone" is basically a folk-sex comedy. If such a thing can exist.

Every fairytale of the Pentamerone is opened by a small recap of the story announcing what it will be about - and already from the get-go the very two lines opening this recap give the humoristic nature of the tale away. "Thalia dies because of a splinter". I mean come on - the joke is obvious. A girl gets a splinter, she dies. And if this wasn't enough the rest of the sentence can be translated as following: "she is left in a room where the son of the king penetrates and makes her two children". The choice of the word "penetrate" is to highlight the pun in the original line where the prince entering Thalia's bedroom and the prince entering Thalia's body is resumed in one same verb.

For more breakdown of the jokes of the story, see below the cut:

As I said before from the get-go the "curse" is treated as a joke. You have this king that summons scholars to make his daughter's horoscope, right? And what does it say. "She is in great danger... BECAUSE OF A SPLINTER!". This is literaly the killer rabbit of the Monty Pythons.

In this story, what does the little old woman that offered the princess the spindle does, once the princess falls dead? (Because she is dead in this version, a magical death, but dead still). Does she warns everybody and cries for help as in Perrault's version? No! "She was quick to find back the stairs [from which she came in]" and she runs as fast away as she can without warning everybody, because she's not going to get into trouble because of some random girl that wanted to see how to spin.

The whole arrival of the prince is very, VERY unprincely and part of the joke. (Well it is a king here but I'm going to call him "prince" so as to not lose people). So he is hunting, right, and his hunting falcon enters the countryside building in which the king locked up his daughter's corpse. The prince wants to get back his bird, so he knocks - because he believes the house is inhabited. And since nobody answers and he REALLY wants his bird back, he fetches a ladder and is forced to climb up a window like a vulgar thief. And he is royalty, remember.

What is the prince's first interaction with the dead Thalia? Believing she is asleep, he starts talking to her. And since she doesn't answer he kind of shakes her around in trying to wake her up. And then suddenly, realizing she kind of looks good (an that she is visibly not alive anymore), he "does his little business" and promptly puts her back where he found her and leaves. Because he is, like most men in the Pentamerone a stupid horny dog without much morals that has the most sudden and bizarre bursts of sexual desire. Cause again the Pentamerone is a sex comedy.

In fact, in the story of "Sun, Moon and Thalia", the prince is MEANT to come off as quite stupid. He is stupid. First off he didn't get that Thalia was dead when he saw her. Then, as soon as he leaves the funeral-house, it is said he "forgot all about this adventure". Like literaly, he forgets all about it - and only suddenly remembers it randomly when Thalia wakes up. (The narration itself highlights the randomness of the events - the fact the prince remembers Thalia is random and for no reason, and in the same way there are two fairies that randomly appear out of nowhere to take care of the two babies and we are never explained anything about them - they even frighten poor awakened Thalia because she doesn't know who brings her magically food every day). When he sees back Thalia, he is all joyful and happy and he is like "Let's start a family! I'm a dad, woohoo!" ; and then the narration drops the bomb that nothing had foreshadowed: "Now, his wife was waiting for him back at the palace." The randomness of dropping the fact he has a wife is meant to be the joke, since we were led to believe he was a bachelor. But given the prince's tendency to forgetfulness it is very likely that he simply forgot he had a wife.

More of the prince's obvious stupidity and air-headedness. On one side how he betrays Thalia and her children's names to his wife - because he just can't stop repeating and singing their names out loud, day and night, even when eating or sleeping, due to how silly-happy he is. On the other, the reason why he is absent while his wife tortures Thalia: he got angry at a comment of hers, and because he was furious, he literaly had to go to ANOTHER LAND just to vent his anger. Literaly, he leaves his palace and moves to another of his domain just because he got pissy. And why did he get pissy? Because his wife kept ironically singing to him "Eat, because what you eat belongs to you" when she served him his "children" - and the stupid prince, unable to understand what she meant, literaly answers "Of course it belongs to me: I'm the bread-winner of the family, while you're doing nothing and bringing nothing to the house". [Which by the way, highlights the fact that in this couple, the wife is depicted as profiting off the king's wealth and power].

Speaking of the dinner around the fake "children": this meal is another sex joke. Because the two of them, the wife and husband, are "panting with desire" around the dishes, and keep singing stuff like "Oh that's good, oh that's good!" and "Come on, eat, come on eat!" making it all an erotic scene. A ridiculous, grotesque, perverse erotic scene around what one character believes to be a cannibalistic meal, while the other just very loudly appreciates good meat.

When the queen tries to have Thalia killed, Thalia tries to defend herself by the fact she didn't know of the queen's existence, and that any sexual thing that happened between her and the prince was in her sleep - which the queen of course does not believe because of how ridiculous it all seems. I mean you catch who you believe is your husband's lasting extra-marital mistress and what is her excuse? "Oh no you see, he made me my kids when I was asleep. Well kind of dead. I didn't know. No he did not wake me up. I didn't wake up either when the kids were born. I'm a really deep sleeper. And it was because of a splinter you see..." Literaly, imagine yourself in the place of the jealous queen hearing all that.

Thalia gains time on her execution by asking the permission to remove her clothes, and the queen accepts, but as a joke she accepts out of greed because she literaly wants to take back Thalia's dress and jewels for herself. And each time Thalia removes a piece of her clothes, she screams. She screams in hope of alerting the prince. But since the prince is far away, he doesn't hear until the very last scream. Meaning that Thalia literaly strips herself in front of the queen, while screaming every time she takes off a piece of clothing, to visibly no effect (which must leave the poor queen quite confused), and it is only when Thalia gets naked and pushes the final scream that the prince suddenly arrive. You can imagine Thalia going: "FINALLY! I've been screaming for hours now!" (especially when you consider how much pieces of clothing princesses wore at the time).

Literaly one of the threats the prince gives to his wife is "Get ready to go fatten up the broccolli". As a metaphor for being dead and buried underground. Tip-top manly threat. In fact the prince is here quite proficient in ridiculous poetic metaphors: when the cook reveals he saved his children, the prince says "Get ready to move out of the small kitchen of my castle to the vast kitchen of my heart."

And of course the final "moral" of the story is also part of the entire farcical joke that is this story. "People who are lucky receive good fortune, even in their sleep". You literaly have a girl who is randomly raped in her sleep and gives birth to children in her dead-sleep, and then is almost murdered by the rapist' wife... And THAT'S the moral of the story? If you take it all literaly, then you are a fool. Or at least Basile would have called you a fool.

Again, people tend to forget that when it comes to literary fairytales (but also a lot of folk-fairytales) there is a TONE that is important. It is the brothers Grimm and other collectors after them that imposed the idea that fairytales were meant to be read "seriously". A lot, LOT of fairytales were originally humoristic - even going into dark humor or sex comedy. And whenever you go by Straparola or Basile, you HAVE to look at them under the angle of a joke or humor, and search for the puns and caricatures and ridiculousness within these tales. Because these books were meant to be read as such. They are like Rabelais' Gargantua or Shakespeare's comedies. You can of course reinterpret them as "serious" tales... But it won't remove the fact the original was humoristic.

#sleeping beauty#dark fairytale#thalia the sun and the moon#sun moon and thalia#thalia sun and moon#basile#pentamerone#italian fairytales#fairytale history#humoristic fairytale#sex jokes#sexuality in fairytales

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A birthday gift I did for @ilpentamerone of a couple of some very in-love OC's together. I'm really pleased how this turned out, particularly the shading/colours.

(I take OC commissions, hmu if you're interested.)

#wiggy#wiggybe#ilpentamerone#pentamerone#original characters#oc's#romance#bed#bedsheets#romantic#couple#love#relationship#Charlie#foster#birthday gift

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

༻✦༺ Petrosinello ༻✦༺

A gay reimagining of "Petrosinella" (a Rapunzel's variant) featuring Emanuele Mariotti as Petrosinello (Rapunzel's counterpart), Alberto Malanchino as the Prince and Pierfrancesco Favino as the Ogre (Mother Gothel, basically).

✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧ :・゚✧:・゚

"Petrosinella" (Little Parsley) was written in Neapolitan by Giambattista Basile and he included it in his 1634 collection of fairy tales "The Tale of Tales." It is an Aarne–Thompson type 310 "the Maiden in the Tower" tale, as well as the earliest recorded variant of "Rapunzel." The Brothers Grimm's more famous version was published almost two centuries later, in 1812.

You can read an English translation of "Petrosinella" here.

✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧✧・゚: ✧・゚: :・゚✧:・゚✧ :・゚✧:・゚

Here you can find the whole list of my Gay Tales!

#fairy tales#gay fairy tales#gay tales#petrosinello#petrosinella#giambattista basile#the tale of tales#lo cunto de li cunti#pentamerone#rapunzel#brothers grimm#emanuele mariotti#alberto malanchino#alberto boubakar malanchino#pierfrancesco favino#moodboard#aesthetics

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

having an absolutely normal day at work where I’m “supervising” aka getting paid more money than usual to sit in the back and exchange giddy infodumps about fairytales, opera, and overlooked 90s female fantasy authors with my older sister

#me#sister story#I should be doing homework but I’m thinking about il Pentamerone and the love for three oranges again

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warwick Goble Lacquer Box

#this sent me down the rabbit hole of researching what a lacquer box is#super interesting craft#I would love to own one someday#warwick goble lacquer box#finds#ebay#Rita riding on Dolphin Storie Pentamerone#fantasy art#fantasy lacquer box#vintage art

0 notes

Text

(a cura di) Antonella Castello

L'ALTRA META' DELLE FIABE

2016 ABEditore

1 note

·

View note

Photo

SELEUSS - L’amour des Trois Oranges

JANUARY 9TH, 2023, SEATTLE, WASHINGTON

We are delighted to announce that our L’amour des Trois Oranges (The Love for 3 Oranges) Chocolate Truffle has been granted the Superior Taste Award with 2-Stars by the International Taste Institute in Brussels for 2023.

The Love for Three Oranges:

Our interpretation of Sergei Prokofiev’s opera; L’amour des Trois Oranges, based on the Italian fairytale by Giambattista Basile in the Pentamerone (Rapunzel, Cinderella...). Made with Clementine, Bergamot and Tangerine, along with organic cream, our favorite honeys and a 53% REGINA™ dark milk chocolate. This batch is enrobed in our MORETTA™ dark chocolate at 76%+ and topped with either granulated Lemon peels, Lemon Ginger Honey Crystals, or occasionally a foot of Chocolate Pailletés Fins.

#seleuss#chocolates#seleusschocolates#theloveforthreeoranges#sergeiprokofiev#lamourdestroisoranges#giambattista basile#pentamerone#chocolatetruffles#seattle#seattlechocolateshop#bestchocolatesinseattle#seattlesbestchocolates#citronmella

1 note

·

View note

Text

7 - L'orco italiano di Basile

7 – L’orco italiano di Basile

youtube

View On WordPress

#amazon#blog#fabrizio valenza#fantasy#Giambattista Basile#Lo cunto de li cunti#orco#Pentamerone#Youtube

0 notes

Text

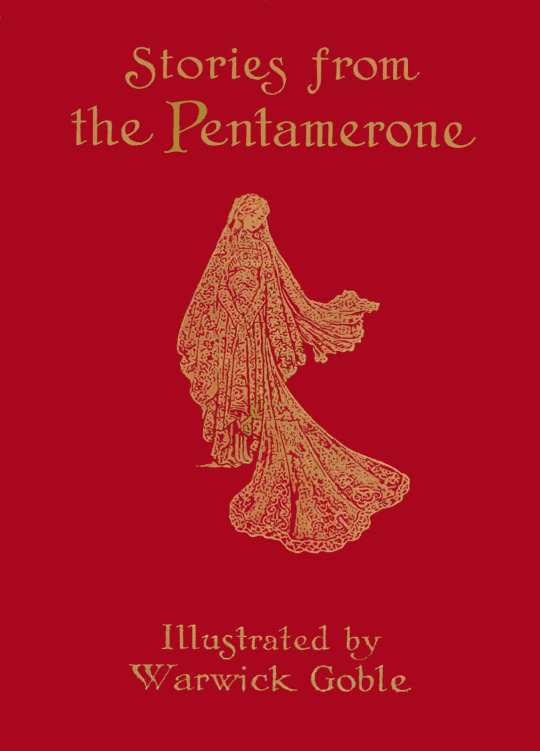

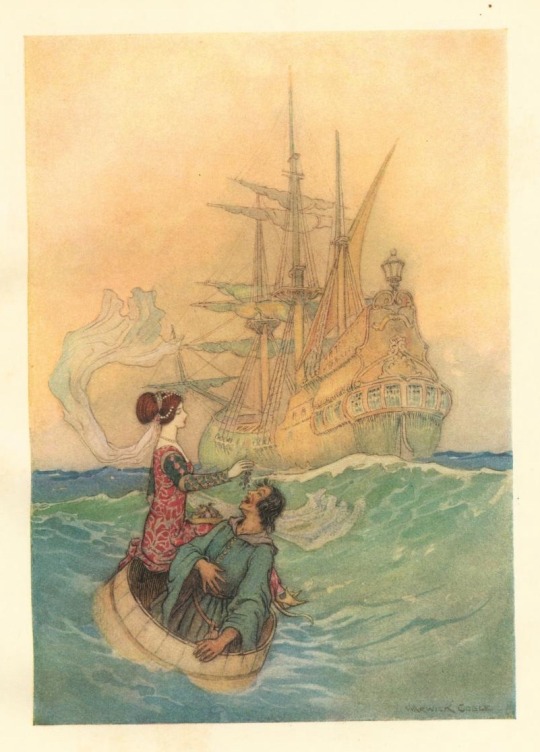

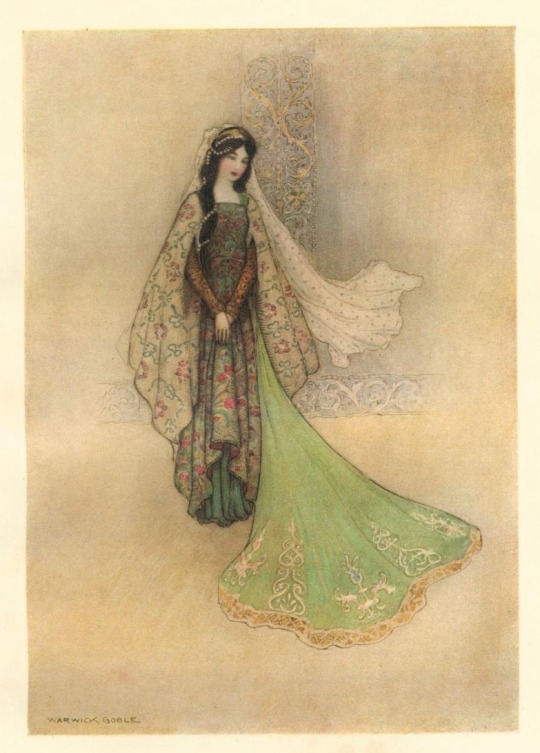

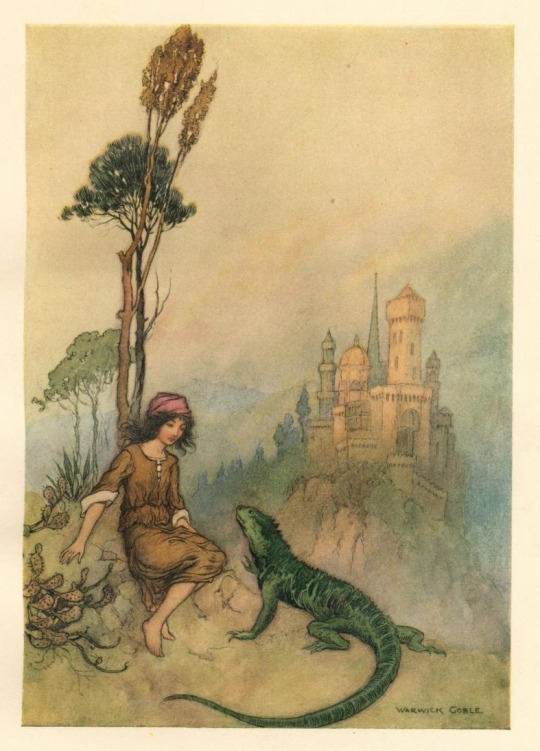

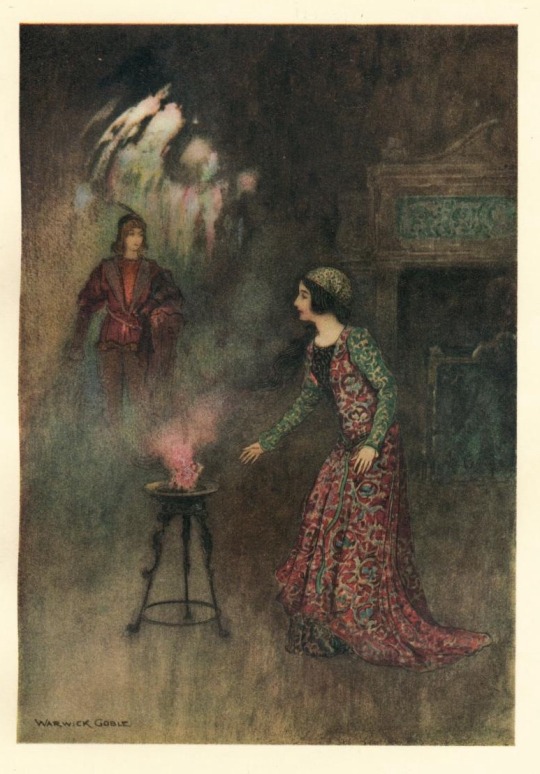

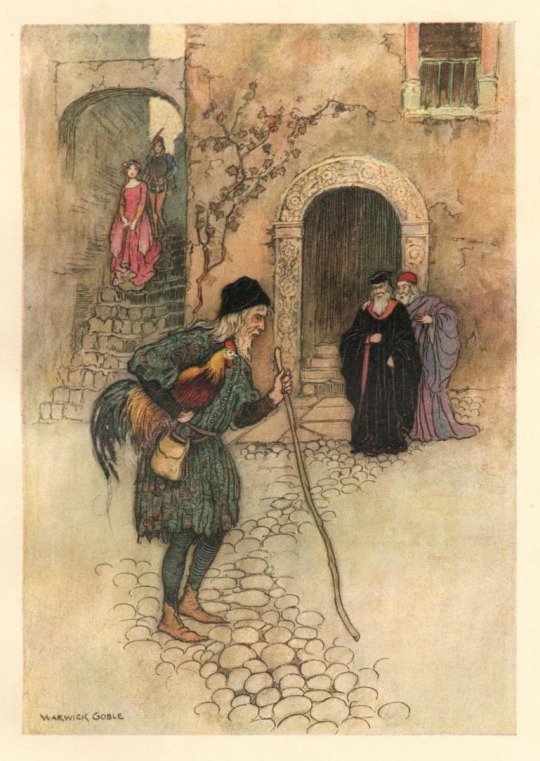

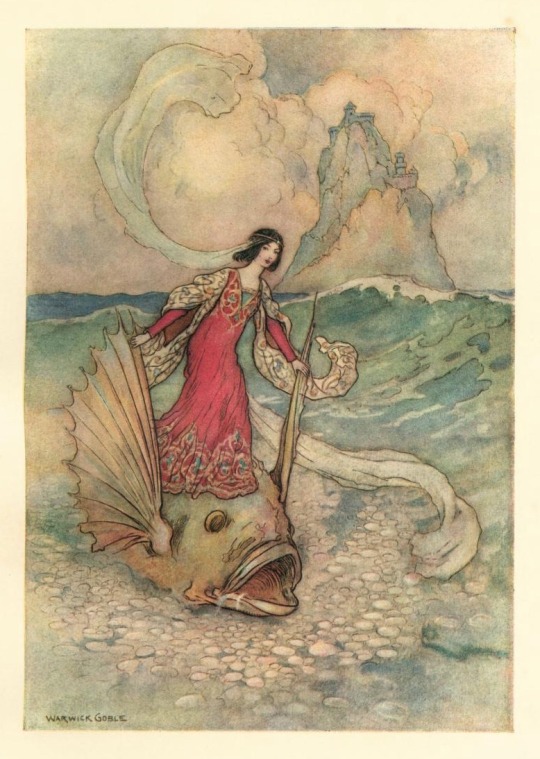

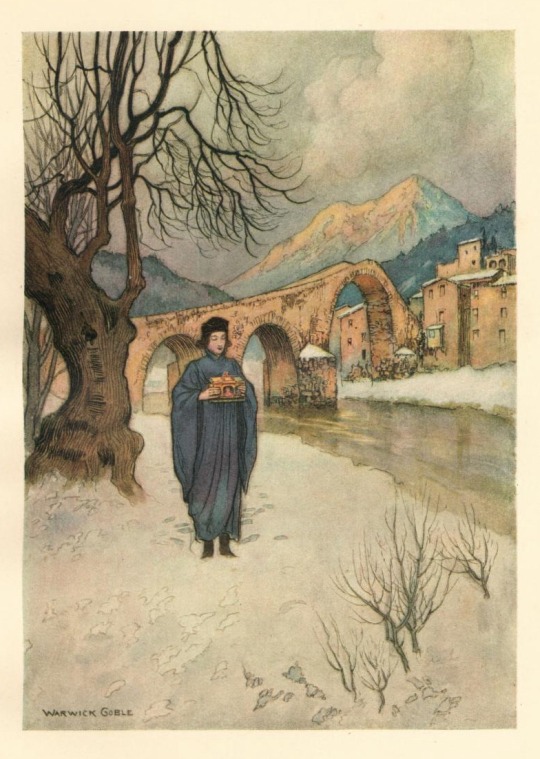

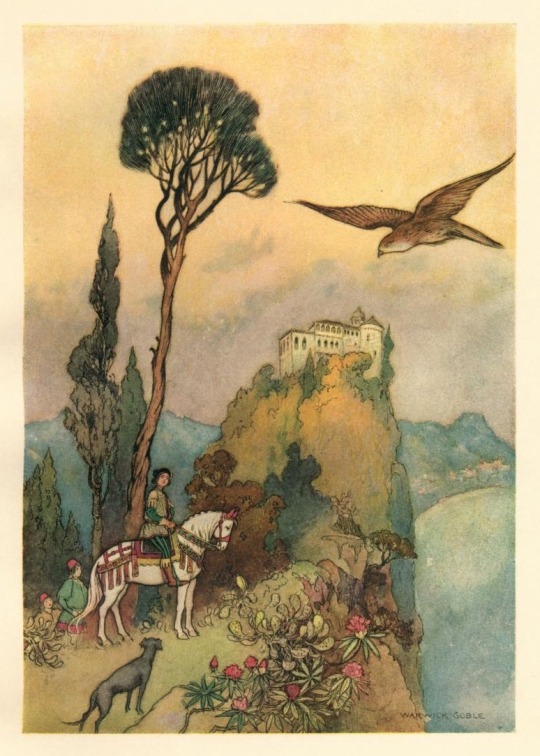

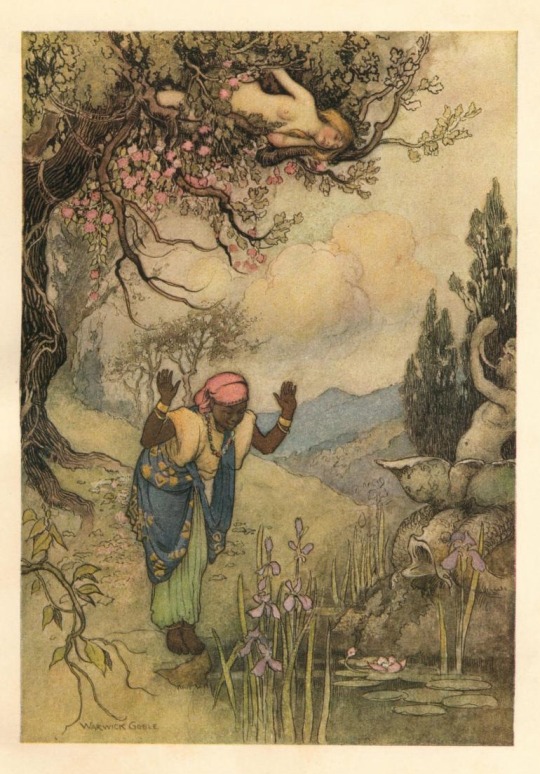

Illustrations from The Pentamerone by Warwick Goble (1911)

#warwick goble#art#illustration#golden age of illustration#1910s#1910s art#vintage art#vintage illustration#vintage#english artist#british artist#books#book illustration#fairy tale#fairy tales#fairytale art#classic art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

STORIES FROM THE PENTAMERONE by Giambattista Basile (1575-1632) (New York/London: Macmillan, 1911). Translated by John Edward Taylor (1847). Dozens of illustrations by Warwick Goble.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#warwick goble#folk tales#italian folklore

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

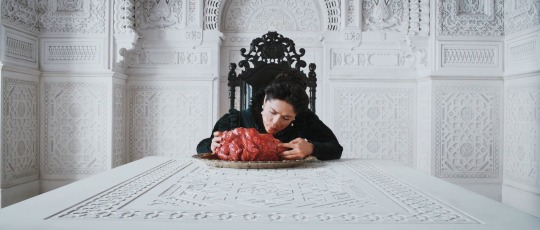

The Tale of Tale movie analysis (1)

It has been a long time since I did a fairytale movie analysis, and for this month I want to take a look at a movie that has been asked of me before, a long time ago: "Tale of Tales".

For those of you who do not know about this movie, "Tale of Tales" is a 2015 movie, a "European production" (it is an Italian movie, but it received help and collaboration from France and England, hence the "European" etiquette) that is to this day (and to my knowledge) the only movie that adapts Basile's Pentamerone, the titular "Tale of Tales".

The Pentamerone being one of the two foundational works when it comes to literary fairytales, and one of the two great books of classical Italian literary fairytales alongside Straparole's Facetious Nights. Basile's book is very famous for containing some of the earlier literary records of fairytale types such as Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty, The Girl Without Hands, and more.

The book contains a total of fifty stories, and of course the movie couldn't adapt them all, so it was decided to only adapt three in total. The three chosen are usually considered emblematic stories of the Pentamerone - but they were also selected because they do not echo the more well known Grimm stories. The three selected were, The Flea, The Enchanted Doe, and The Flayed Old Lady - all taken from the first part of the book.

Note that this movie was greatly acclaimed for its extensive use of practical special effects - and there is one thing you cannot deny this movie, it looks absolutely incredible. There is a great effort on the visuals ranging from selected architecture and landscape to careful costume crafting and delightful monsters on screen.

Before going into the analysis of each of the fairytales of the movie, I wanted to point out a few things covering the entirety of the movie. Three details to be exact.

Matteo Garrone, when doing this movie, didn't just randomly selected three stories that were to his fancy. He chose three specific stories that he then tied together with cohesive themes and motifs. The first of which, the most prominent, being "obsession". Each segment is about presenting the obsessions of specific characters, and the bad outcomes of it.

The other shared motif between the three fairytales is "the ages of a woman". Despite the movie having as much male as female characters, Garrone explained very clearly that this movie was about the women, not the men, and that each fairytale represented one of the traditional three "ages of woman". "The Flea" becomes the Maiden story, focusing on the young princess ; "The Enchanted Doe" becomes the Mother story, with an exploration of the character of the queen, while "The Flayed Old Lady" is of course the Crone tale.

But much more importantly for us to understand this movie: Matteo Garrone did one very heavy and important change compared to the original material. The tone. The tone is radically different. Basile's original book, just like Straparole's fairytales, worked by the specific nature of these Italian literary fairytales of the time: they were grotesque farces, and vulgar jokes. In my last post about the Pentamerone I compared these stories to a Brandon Rogers video, because Basile's stories, despite being the ancestors of the Grimm or Perrault fairytales, are nothing like the modern fairytales we are today. They are sex stories filled with caricatures, they are gruesome, gory stories filled with morally-gray characters, they are one huge dark joke filled with poop and farts and vulgar allusions. They are much closer to medieval tales and to the tone of a Reynard the Fox story or some Rabelais books than any other fairytales we know today. But Garrone decided to apply a principle that you can see explored in series such as "Horace and Pete" or "Kevin can fuck himself". Take a sitcom, remove the laugh-track, you have a tragedy. Garrone's movie is still as grotesque as the original stories - but now the jokes are put aside, the most vulgar parts removed, the sex and the gore examined for what it is under a realistic eye. This "realistic", and "non-comical" treatment of the stories make this world of grotesque caricatures and senseless violence and depraved debauchery one not of marvels and fairies, but one of tragedies, of abuse, of horror. But, tragedies with magic, abuse with beauty, horror with happy and hopeful endings - because they stay fairytales after all, no matter how dark they are. Mean, cruel, sad fairytales, but fairytales nonetheless.

[Trivia: The fact that Basile's work was a very rude, crude and vulgar piece of sex-and-violence that can only be compared to Rabelais meeting Punch & Judy, is something many people in the English-speaking world completely missed because the first real popular and widespread translations of the text in English, in the... I think it was the 19th century or maybe a bit earlier ; but these versions were heavily censored. Trying to make the story more like a Perrault or d'Aulnoy tale, they removed many sex references, remove all the poop jokes, and even cut off some stories deemed too vulgar ot gruesome, so that for a very long time people thought they were supposed to be... regular fairytales. This is especially relevant with "Thalia, the Sun and the Moon", Basile's "Sleeping Beauty" variant. Many people point out that the girl in this story gets raped by the prince and that this shows how the fairytale of Sleeping Beauty was built on a glorification of rape, because it is treated as ormal or as some romance. But... no. This rape is treated as a rape and the prince is very clearly a lustful asshole who is taking advantage of the girl - because it is a dark sex-tale. Princes in the Pentamerone are almost all lustful rapists, violent murderers or complete helpless idiots, because the Pentamerone does not work on a "prince charming" logic. Take "The Golden Root" - the handsome, kind, gentle, good prince that seems to fit the bill of the Prince Charming... is part of a family of ogres, and ends up murdering in rage his intended fiancée just to be married to the heroine of the tale. And that's something that many people missed for a very long time - the prince charming archetype is from the French tales of the 17th and 18th century, not before.]

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm making my way through the "Donkeyskin" section of Cinderella Tales from Around the World, starting with the versions from Greece, Albania, and Italy.

*In most of these variants, the condition for the father-king's remarriage is either that his bride's finger must fit the late queen's wedding ring or that her foot must fit the queen's shoe. One day, either not knowing about the promise or just not suspecting how far her father will take it, the princess puts on the ring or the shoe and finds that it fits, so her father resolves to marry her.

**As I mentioned in my last post, however, some versions don't have her father want to marry her. In one version, her father is just extremely protective and never lets her leave the castle, so she runs away out of longing for freedom. (Although this is from Andrew Lang's The Grey Fairy Book, so Lang most likely bowdlerized it.) In another, her father betroths her to a rich young man who is really the Devil in disguise, which her fairy governess realizes and alerts her to, but which her father won't believe.

*In different Donkeyskin tales throughout the world, it varies whether the heroine comes up with her gown requests and her disguise by herself or is advised by someone else. These Mediterranean versions tend to give her an advisor: usually her nurse or governess who's secretly a fairy or a good witch, but sometimes a male magician instead, or even the Pope.

*The theme of the three gowns in these variants tends to be this: one gown that looks like the heavens with the sun, the moon, and all the stars on it, one that looks like the sea with all the fishes on it, and one that looks like the earth with every type of flower on it. Several Mediterranean versions of Cinderella also uses this theme for the heroine's gowns.

**Also as in Mediterranean Cinderellas, the heroine sometimes throws coins or jewels behind her when she leaves each ball to distract the prince's servants and prevent them from stopping her.

*Several Italian versions are titled Maria Wood. In some of them, she just wears a wooden dress like the Norwegian Kari Woodencloak. But in others, more interestingly, she encases herself in a full-body suit made of wood, with joints so she can move her limbs, which makes her look like an old woman. Sometimes she sings a funny little rhyme about being "made of wood" when she first introduces herself to the prince or king. This suit also miraculously has room to store her three gowns inside it.

**In other versions, though, she disguises herself in animal skins – e.g. pigskin, rabbit skins, or wolf skin. Sometimes, instead of just passing as a human dressed in skins, she actually masquerades as an animal – a bear, or a horse – although it varies whether she pretends to be an ordinary, non-sapiant animal who stays in the palace yard or a talking animal who works as a scullery maid.

**Giambattista Basile's Il Pentamerone includes a variant, The She-Bear, where the heroine turns herself into a bear by putting a piece of magic wood (given to her by a wise old woman) into her mouth. After she flees, the prince finds her in the forest, and she becomes his pet. The truth is finally revealed when the bear kisses the sick prince, and as she does so, the piece of wood accidentally falls from her lips.

**In another version, called Zuccaccia ("Ugly Gourd"), she disguises herself in a dress covered with strips of dried pumpkin.

**In yet another version, called Pellicotto ("Ugly Skin"), a fairy helps the heroine by magically coating her entire body and face with fur. Then the heroine further disguises herself by putting on male clothes and finds work as the prince's stable-boy. I suspect that "Sapsorrow" from Jim Henson's The Storyteller was partly inspired by this version, since Sapsorrow is likewise completely covered with fur and wears men's breeches in her magical disguise as "the Scraggletag."

*In some versions, she doesn't wear strange clothing or go to work as a servant at all. Instead, she requests a gift of two giant hollow candlesticks or a candelabrum from her father. Then she hides inside one of the candlesticks/the candelabrum, which a servant takes to another kingdom and sells to the prince. Every night when the prince has gone out or is asleep, she emerges and either eats some of his food or tidies his room. This mystifies the prince until he finally spies on the room at night, discovers her, and falls in love. Some similar variants have her hide in a simple wooden chest instead of a candlestick/candelabrum.

*Sometimes she hides her beautiful gowns in a chest, sometimes in three nutshells, or sometimes she has a magic wand with which she makes them appear when she needs them.

*The majority of these versions – and probably the majority from every country, though we'll see if it's true or not – have the prince or king mistreat the disguised heroine. Traditionally, before each of the three balls, she asks to be allowed to go, but he refuses and hits her with an object (often a boot, a shovel, and tongs, though they vary). Then at the ball, when he asks the "beautiful princess" where she comes from, she replies that she's from the land of "Boot," "Shovel," and "Tongs," or whatever the objects were. @adarkrainbow and I have already discussed this recurring theme and how to understand it. In the past, both male-on-female and master-on-servant abuse were more often played for laughs. In this case, assuming that the oral storytellers were mostly commoners, it's arguably social satire at the prince/king's expense (i.e. "Ha ha! Those royals and nobles treat us like dirt, but if we had clothes like theirs they might fall madly in love with us!"), and the princess's trick at the ball can be seen as revenge, sending him on wild goose chases in search of the lands of "Boot," "Shovel," etc. Still, by modern standards, it's not comfortable seeing the heroine treated this way by her future husband.

**Some versions omit this theme, however, and have the prince treat her kindly and see her as a funny little friend. In a few, instead of refusing when she asks to go the three balls, he invites her to the balls, but she pretends to refuse. Zuccaccia is one of these variants: though it keeps the running gag of the prince hitting her with objects, it reimagines them as just light, playful raps amid sibling-like banter.

**One other version has the prince just verbally insult her, and at the balls, when he asks for her name, she replies with the names he called her earlier: "My name is Mud-Scraper," "My name is Blockhead," etc. In yet another, she hits him with the objects each time he refuses to take her to the ball.

*In some versions, at the third ball, the prince/king slips a ring onto the princess's finger, which she later drops into the bread, cake, or soup she sends to him when he becomes sick with love. In others, after the third ball, she sends him food over the course of three days, and each time she drops a golden trinket that she brought from home into the food. Either way, he asks to see the person who made the food, and either she comes undisguised in her beautiful gown, or else he rips off her disguise and reveals the gown underneath it. Or, in a simpler alternative, she asks to take the food to his sickroom herself, and she does so wearing her beautiful gown.

*On her website, though not in this book itself, Heidi Ann Heiner notes that in many Donkeyskin tales (e.g. Perrault's), the father-king gets less blame than he deserves for his incestuous desire and is easily forgiven in the end. That isn't the case in many Italian versions, though: he's clearly portrayed as a villain.

**In several variants, the king is carried away by the Devil as soon as his daughter runs away. In one, he actually sells his soul to the Devil in exchange for the three otherworldly gowns his daughter demands from him, which leads to the Devil claiming his due after the wedding doesn't take place.

**Several other versions follow the heroine's marriage by having the father seek revenge for her refusal to marry him. In an especially grisly literary version, Doralice, the king comes to his daughter's new home in disguise, murders her two children, and then frames her for the crime. For this her husband has her buried up to her chin in the ground to be slowly eaten by worms. But her childhood nurse finally reveals the whole truth to the young king, so Doralice is saved, while her wicked father is tortured to death. In a similar but milder variant, The Deer, the king uses magic to turn his daughter into (of course) a deer; but eventually she meets her husband again during a hunt in the woods and provokes him to shoot her, which breaks the spell. In yet another, the king tries to throw his daughter into a cauldron of boiling oil, only to get caught just in time and be thrown in himself.

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#donkeyskin#fairy tale#variations#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#greece#albania#italy#tw: incest#tw: abuse#tw: violence#tw: murder

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fantasy read-list: B-2

Part B: The First Classical Fantasy

2) On the other side, a century of France...

As I said in my previous post, for this section I will limit myself to two geographical areas: on one side the British Isles (especially England/Scotland), and now France. More specifically, the France of fairytales!

Maybe you didn’t know, but the genre of fairy tales, and the very name “fairy tale” was invented by the French! Now, it is true that fairytales existed long before that as oral tales spread from generations to generations, and it is also true that fairy tales had entered literature and been written down before the French started to write down their own... But the fairytale genre as we know it today, and the specific name “fairy tale”, “conte de fées”, is a purely French AND literary invention.

# If we really want to go back to the very roots of fairy tales in literature, the oldest fairytale text we have still today, it would be a specific segment of Apuleius’ The Golden Ass (or The Metamorphoses depending on your favorite title). In it, you find the Tale of Psyche and Cupid, and this story, which got MASSIVELY popular during the Renaissance, is actually the “original” fairytale. In it you will find all sorts of very common fairytale tropes and elements (the hidden husband one must not see, the wicked stepmother imposing three impossible tasks, the bride wandering in search of her missing husband and asking inanimate elements given a voice...), as well as the traditional fairytale context (an old woman telling the story to a younger audience to carry a specific message). In fact, all French fairytale authors recognized Psyche and Cupid as an influence and inspiration for their own tales, often making references to it, or including it among the “fairytales” of their time.

# The French invented the genre and baptized it, but the Italian started writing the tales and began the new fashion! The first true corpus, the first literary block of fairytales, is actually dating from the 16th century Italy. Two authors, Straparola and Basile, inspired by the structure, genre and enormous success of Boccace’s Decameron, published two anthologies respectively titled, Piacevoli Notti (The Facetious Nights) and the Pentamerone, or The Tale of Tales. These books were anthologies of what we would call today fairytales, stories of metamorphosed princes, and fairies, and ogres, and magical animals, and bizarre transformations, and curses needing to be broken, and damsels needing to be rescued... In fact, these books contain the “literary ancestors” and the “literary prototypes” of some of the very famous fairytales we know today. The ancestors of Sleeping Beauty (The Sun, the Moon and Thalia), Cinderella (Cenerentola), Snow-White (Lo cuorvo/The Raven), Rapunzel (Petrosinella) or Puss in Boots (Costantino Fortunato, Cagliuso)...

However be warned: these books were intended to be licentious, rude and saucy. They were not meant to be refined and delicate tales - far from it! Scatological jokes are found everywhere, many of the tales are sexual in nature, there’s a lot of very gory and bloody moments... It was basically a series sex-blood-and-poop supernatural comedies where most of the characters were grotesque caricatures or laughable beings. We are far, far away from the Disney fairytales...

# The big success and admiration caused by the Italian works prompted however the French to try their hand at the genre. They took inspiration from these stories, as well as from the actual oral fairytales that were told and spread in France itself, and turned them into literary works meant to entertain the salons and the courts. This was the birth of the French fairytale, at the end of the 17th century - and the birth of the fairytale itself, since the name “fairy tale” was invented to designate the work of these authors.

The greatest author of French fairytale is, of course, Charles Perrault with his Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passé (Stories or Tales of the Past), mistakenly referred to by everyone today as Les Contes de Ma Mère L’Oie (Mother Goose Fairytales - no relationship to the Mother Goose of nursery rhymes). Charles Perrault is today the only name remembered by the general public and audience when it comes to fairytales. He is THE face of fairytales in France and part of the “trio of fairytale names” alongside Grimm and Andersen. He wrote some of the most famous fairytales: Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, Cinderella... He also wrote fairytales that are considered today classics of French culture, even though they are not as well known internationally: Donkey Skin, Diamonds and Toads or Little Thumbling. The first Disney fairytale movies (Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella) were based on his stories!

But another name should seat alongside his. If Charles Perrault was the father of fairytales, madame d’Aulnoy was their mother. She was for centuries just as famous and recognized as Charles Perrault - when Tchaikovsky made his “Sleeping Beauty” ballet, he made heavy references to both Perrault and d’Aulnoy - only to be completely ignored and erased by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for all sorts of reasons (including the fact she was a woman). But Madame d’Aulnoy had stories translated all the way to Russia and India, and she wrote twice more fairytales as Perrault, and she was the author of the very first chronological French fairytale! (L’Ile de la Félicité, The Island of Felicity). Her fairytales were compiled in Les Contes des Fées (The Tales of Fairies), and Contes Nouveaux, ou Les Fées à la mode (New Tales, or Fairies in fashion) - and while for quite some times madame d’Aulnoy fell into obscurity, many of her tales are still known somehow and stayed classics that people could not attribute a name to. The White Doe (an incorrect translation of “The Doe in the Wood), The White Cat, The Blue Bird, The Sheep, Cunning Cinders, The Orange-Tree and the Bee, The Yellow Dwarf, The Story of Pretty Goldilocks (an incorrect translation of “Beauty with Golden Hair”), Green Serpent...

A similar warning should be held as with the Italian fairytales - because the French fairytales aren’t exactly as you would imagine. These fairytales were very literary - far away from the short, lacking, simplified folklore-like tales a la Grimm. They were pieces of literature meant to be read as entertainment for aristocrats and bourgeois, in literary salons. As a result, these pieces were heavily influenced (and heavily referenced) things such as the Greco-Roman poems, or the medieval Arthuriana tales, and the most shocking and vulgar sexual and scatological elements of the Italian fairytales were removed (the violence and bloody part sometimes also). But it doesn’t mean these stories were the innocent tales we know today either... These fairytales were aimed at adults, and written by adults - which means, beyond all the cultural references, there are a lot of wordplays, social critics, courtly caricatures and hidden messages between the lines. The sexual elements might not be overtly present for example, but they are here, and can be found for those that pay attention. These stories have “morals” at the end, but if you pay attention to the tale and read carefully, you realize these morals either do not make any sense or are inadequated to the tales they come with - and that’s because fairy tales were deeply subversive and humoristic tales. People today forgot that these fairytales were meant to be read, re-read, analyzed and dissected by those that spend their days reading and discussing about it - things are never so simple...

# While Perrault and d’Aulnoy are the two giants of French fairytales, and the ones embodying the genre by themselves, they were but part of a wider circle of fairytale authors who together built the genre at the end of the 17th century. But unfortunately most of them fell into obscurity... Perrault for example had a series of back-and-forth coworks with a friend named Catherine Bernard and his niece mademoiselle Lhéritier, both fairytale authors too. In fact, the “game” of their “discussion through their work” can be seen in a series of three fairytales that they wrote together, each author varying on a given story and referencing each-other in the process: Catherine Bernard wrote Riquet à la houppe (Riquet with the Tuft), Charles Perrault wrote his own Riquet à la houppe in return, and mademoiselle Lhéritier formed a third variation with the story Ricdin-Ricdon. Other fairytale authors of the time include madame de Murat/comtesse de Murat, mademoiselle de La Force, or Louise de Bossigny/comtesse d’Auneuil. Yes, the fairytale scene was dominated by women, since the fairytale as a genre we perceived as “feminine” in nature. There were however a few men in it too, alongside Perrault, such as the knight de Mailly with his Les Illustres Fées (Illustrious Fairies) or Jean de Préchac with his Contes moins contes que les autres (Fairy tales less fairy than others).

A handful of these fairytales not written by either Perrault or d’Aulnoy ended up translated in English by Andrew Lang, who included them in his famous Fairy Books. For example, The Wizard King, Alphege or the Green Monkey, Fairer-than-a-Fairy (The Yellow Fairy Book) or The Story of the Queen of the Flowery Isles (The Grey Fairy Book).

# These people were however only the first wave, the first generation of what would become a “century of fairytales” in France. After this first wave, the publication of a new work at the beginning of the 18th century shook French literature: Antoine Galland translation+rewriting of The One Thousand and One Nights, also known later as The Arabian Nights. This work created a new wave and passion in France for “Arabian-flavored fairytales”. Everybody knows the Arabian Nights today, thanks to the everlasting success of some of its pieces (Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Sinbad the Sailor, The Tale of Scheherazade...), but less people know that after its publication in France tons of other books were published, either translating-rewriting actual Arabian folktales, or completely inventing Arabian-flavors fairytales to ride on the new fashion. Pétis de la Croix published Les Milles et Un Jours, Contes Persans, “The One Thousand and One Days, Persian tales” to rival Galland’s own book. Jean-Paul Bignon wrote a book called Les Aventures d’Abdalla (The Adventures of Abdalla), and Jacques Cazotte a fairytale called La Patte de Chat (The Cat’s Paw). I could go on to list a lot of works, but to show you the “One Thousand and One” mania - after the success of 1001 Nights and 1001 Days, a man called Thomas-Simon Gueulette came to bank on the phenomenon, and wrote, among other things, The One Thousand and One Hours, Peruvian tales and The One Thousand and One Quarter-of-Hours, Tartar Tales.

# Then came what could be considered either the second or third “wave” or “generation” of fairytales. It is technically the third since it follows the original wave (Perrault and d’Aulnoy times, end of the 17th) and the Arabian wave (begining of the 18th). But it can also be counted as the second generation, since it was the decision in the mid 18th century to rewrite French fairytales a la Perrault and d’Aulnoy, rejecting the whole Arabian wave that had fallen over literature. So, technically the “return” of French fairytales.

The most defining and famous story to come of this generation was, Beauty and the Beast. The version most well-known today, due to being the shortest, most simplified and most recent, was the one written by Mme Leprince de Beaumont, in her Magasin des Enfants. Beaumont’s Magasin des Enfants was heavily praised and a great best-seller at the time because she was the one who had the idea of making fairytales 1- for children and 2- educational, with ACTUAL morals in them, and not fake or subversive morals like before. If people think fairytales are sweet stories for children, it is partially her fault, as she began the creation of what we would call today “children literature”. However Leprince de Beaumont did not invent the Beauty and the Beast fairytale - in truth she rewrote a previous literary version, much longer and more complex, written by madame de Villeneuve in her book La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins (The Young American Girl and the sea tales). Madame de Villeneuve was another fairy-tale author of this “fairytale renewal”. Other names I could mention are the comtesse de Ségur, who wrote a set of fairytales that were translated in English as Old French Fairytales (she was also a defender of fairytales being made into educational stories for children), and mademoiselle de Lubert, who went the opposite road and rather tried to recreate subversive, comical, bizarre fairytales in the style of madame d’Aulnoy - writing tales such as Princess Camion, Bear Skin, Prince Glacé et Princesse Etincelante (Prince Frozen and Princess Shining), Blancherose (Whiterose)...

Similarly to what I described before, a lot of these fairytales ended up in Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books. Prince Hyacinth and the Dear Little Princess, Prince Darling (The Blue Fairy Book), Rosanella, The Fairy Gifts (The Green Fairy Book)...

# The “century of fairy tales” in France ended up with the publication of one specific book - or rather a set of books. Le Cabinet des Fées, by Charles-Joseph Meyer. As we reached the end of the 18th century, Meyer noticed that fairy tales had fallen out of fashion. None were written anymore, nobody was interested in them, nothing was reprinted, and a lot of fairytales (and their authors) were starting to fall into oblivion. Meyer, who was a massive fan of fairytales, hated that, and decided to preserve the fairytale genre by collecting ALL of the literary fairytales of France in one big anthology. It took him four years of publication, from 1785 to 1789, but in a total of forty-one books he managed to collect and compile the greatest collection of French literary fairytales that was ever known - even saving from destruction a handful of anonymous fairytales we wouldn’t know existed today if it wasn’t for his work. In a paradoxical way, while this ultimate collection did save the fairytale genre from disappearing, it also marked the end of the “century of fairytales”, as it set in stone what had been done before and marked in the history of literature the fairytale genre as “closed off”. All the French fairytales were here to be read, and there was nothing more to add.

Ironically, Le Cabinet des Fées itself was only reprinted and republished a handful of times, due to how big it was. The latest reprints are from the 19th century if I recall correctly - and after that, there was a time where Le Cabinet was nowhere to be found except in antique shops and private collections. It is only in very recent time (the late 2010s) that France rediscovered the century of fairytales and that new reprints came out - on one side you have cut-down and shortened versions of Le Cabinet published for everybody to read, and on the other you have extended, annotated, full reprints of Le Cabinet with additional tales Meyer missed that are sold for professional critics, teachers, students and historians of literature. But the existence of Le Cabinet, and Meyer’s great efforts to collect as much fairytales as possible, would go on to inspire other men in later centuries, inciting them to collect on their own fairytales... Men such as the brothers Grimm.

#fantasy literature#fantasy read-list#fantasy reading list#fairy tales#fairytales#history of fairy tales#french literature#the one thousand and one nights#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#italian fairy tales#the century of fairytales#evolution of fairytales

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tale of Tales (Il racconto dei racconti, 2015)

Directed by Matteo Garrone

Written by Matteo Garrone, Ugo Chiti, Edoardo Albinati and Massimo Gaudioso

Based on Pentamerone, written by Giambattista Basile

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

read any good books lately?

Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone (also known as The Tale of Tales), which is a delightfully playful and unabashedly lewd XVII century collection of Neapolitan fairy tales

3 notes

·

View notes