#Rochereau

Text

Les couleurs de la ville.

Mur

#photographie urbaine#urban photography#couleurs urbaines#urban colors#décor urbain#urban decor#abstraction#figuration#mur#wall#minimalisme#minimalism#rue denfert-rochereau#croix rousse#69004#lyon#rhône#auvergne rhône alpes#france#photographers on tumblr#poltredlyon#osezlesgaleries#monlyon#onlylyon#igerslyon#lyonurb

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

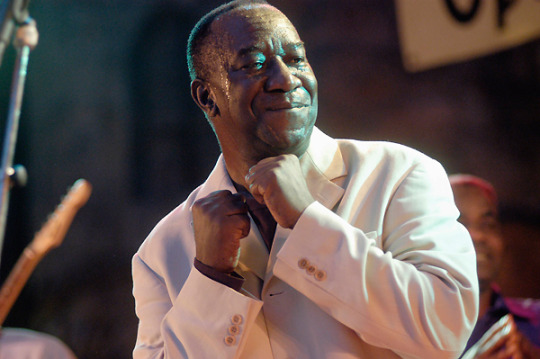

Tabu Ley Rochereau - late 60's, early 70's.

#Tabu Ley Rochereau#Rumba#Cha-Cha#African#Congo#Africa#World music#60s#1960s#70s#1970s#SoundCloud#music

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congolese singer, songwriter, and bandleader Tabu Ley Rochereau (November 13, 1940 - November 30, 2013)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

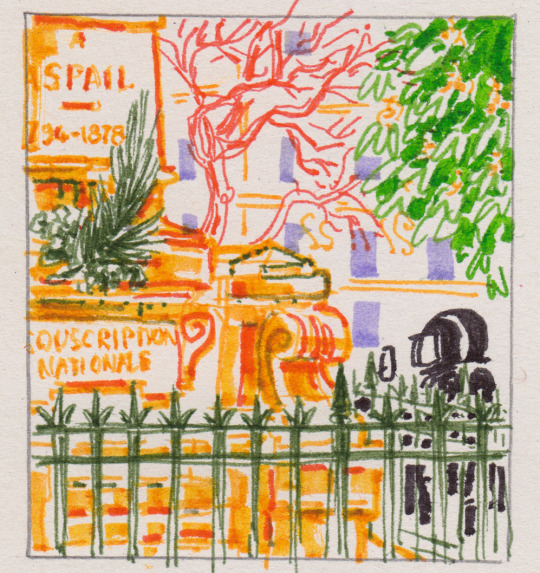

Piédestal du monument à Raspail, fondu en 1942, square Jacques-Antoine, place Denfert-Rochereau, Paris 14e – feutre, carnet n° 109, 26 avril 2016

#2016#piedestal#palme#souscription nationale#monument#raspail#grille#square jacques antoine#place denfert rochereau#paris#14e#moto#motard#casque#feutre#carnet 109

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The untouched bedroom of World War I soldier Hubert Rochereau. He died in an English field ambulance on April 26, 1918 a day after being wounded during fighting for the village of Loker in Flanders. He was 21 years old. His parents had no idea where he was buried until 1922 when his body was discovered in a British cemetery and repatriated to the graveyard at Bélâbre, France. They turned the room into a permanent memorial, leaving it largely as it had been the day he went off to war.

— BBC World News

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 notes

·

View notes

Audio

#music discovery#music#spotify link#spotify#music artists#steve monite#tabu ley rochereau#song#hafi deo#Hafi Deo - Nick The Record & Dan Tyler Re-Edit Dub#genres#afropop#highlife#rumba congolaise#soukous#world#Bourgeoiz Music Discovery#MORE MUSIC ON MY BLOG#from me

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Les couleurs de la ville.

Mur

Rue Denfert-Rochereau III

#photographie urbaine#urban photography#couleurs urbaines#urban colors#figuration#abstraction#mur#wall#minimalisme#minimalism#rue denfert rochereau#croix rousse#69004#lyon#rhône#auvergne rhône alpes#france#photographers on tumblr#poltredlyon#monlyon#onlylyon#igerslyon#lyonurb#brumpicts#frédéric brumby

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAMPIGNY EN ROCHEREAU - Vienne

Scoop : la photo volée du futur modèle électrique Honda

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congolese singer, songwriter, and bandleader Tabu Ley Rochereau (November 13, 1940 - November 30, 2013)

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your favorite random historical fact?

Ooh idk if I have one specific favorite, but here are some cool ones: (ok so I ended up putting a lot 💀)

• The Marquis de Sade was possibly the judge in a lawsuit that Voltaire was involved in by virtue of his being the Lieutenant of Gex. There's a letter to Sade from the Marquis de Jaucourt where he says that V has told him that Sade is the judge, and Jaucourt doesn't give any details of the lawsuit but he's basically trying to act as a character witness for V. The letter is from June of 1770 and Sade went back to his army regiment in July, so idk if he actually did end up serving as the judge or what happened with the lawsuit.

• Following that one but I just wanted to split up the text block, V and Sade were actually related to each other. V's niece adopted Reine Philiberte, who married Villette, and Villette was cousins with Sade's wife. Villette was also maaaybe V's biological son but like no he wasn't lol. Small world ig

• Michael Dillon, the first trans man to get a phalloplasty (1946-ish, but it was multiple surgeries over a long time), was also the first Westerner to become a Tibetan monk. His monk name (?) was Jikava, which was the name of the Buddha's personal doctor, presumably because Dillon was also a doctor. He also performed SRS on Roberta Cowell, a trans woman who was a racecar driver and fighter pilot.

• The Dictionnaire Critique from 1787 says that the word "energy" is "very fashionable"; I've found one example in Robespierre's papers containing the phrase that someone was "going against the energy we're creating here". 1780s bitches 🤝 2000s bitches

• Rousseau being told that Candide was a response to a letter from him that V never answered and saying he wouldn't know bc he'd never read it. I hate Rousseau but. king shit right there.

• There was a rumor going around that the prostitutes who worked in the Luxembourg Gardens were planning to attack Villette, who also frequently hung out there, because he was stealing all their customers.

• The street with the main entrance to the Paris Catacombs, where a house collapsing led to the project being started to shore up the catacombs, was called the Rue d'Enfer, and no one knows the reason behind the name. Two main theories are that it was an execution place during Roman times, or that it could be "en fer" like something built out of iron. The city, thinking the name 'Road of Hell' wasn't very great (that fucking rocks as a road name), changed it to the Rue d'Enfert-Rochereau in 1878 after a colonel who'd been at the siege of Belfort.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monday 13 May 1 , 15 pm.

The streets are crowded, The response to the call for a 24-hour general strike has exceeded the wildest hopes of the trade unions. Despite the short notice Paris is paralysed. The strike was only decided 48 hours ago, after the ‘night of the barricades’. It is moreover ‘illegal’. The law of the land demands a five-day notice before an ‘official’ strike can be called. Too bad for legality. A solid phalanx of young people is walking up the Boulevard de Sébastopol, towards the Gare de I’Est. They are proceeding to the student rallying point for the giant demonstration called jointly by the unions, the students’ organization (UNEF) and the teachers’ associations (FEN and SNESup).

There is not a bus or car in sight. The streets of Paris today belong to the demonstrators. Thousands of them are already in the square in front of the station, Thousands more are moving in from every direction. The plan agreed by the sponsoring organizations is for the different categories to assemble separately and then to converge on the Place de Ia République, from where the march will proceed across Paris, via the Latin Quarter: to the Piace Denfert-Rochereau. We are already packed like sardines for as far as the eye can see, yet there is more than an hour to go before we are due to proceed. The sun has been shining all day, The girls are in summer dresses, the young men in shirt sleeves. A red flag is flying over the railway station. There are many red flags in the crowd and several black ones too.

A man suddenly appears carrying a suitcase full of duplicated leaflets. He belongs to some left ‘groupuscule’ or other. He opens his suitcase and distributes perhaps a dozen leaflets. But he doesn’t have to continue alone. There is an unquenchable thirst for information, ideas, literature, argument, polemic. The man just stands there as people surround him and press forward to get the leaflets. Dozens of demonstrators, without even reading the leaflet, help him distribute them. Some 6000 copies get out in a few minutes. AII seem to be assiduously read, People argue, laugh, joke. I witnessed such scenes again and again.

Sellers of revolutionary literature are doing well. An edict, signed by the organizers of the demonstration, that lathe only literature allowed would be that of the organizations sponsoring the demonstration” (see I’Humanité, 13 May 1968, page 5) is being enthusiastically flouted. This bureaucratic restriction (much criticised the previous evening when announced at Censier by the student delegates to the Co-ordinating Committee) obviously cannot be enforced in a crowd of this size. The revolution is bigger than any organization, more tolerant than any institution ‘representing’ the masses, more realistic than any edict of any Central Committee. Demonstrators have climbed onto walls, onto the roofs of bus stops, onto the railings in front of the station. Some have loud hailers and make short speeches. All the ‘politicos’ seem to be in one part or other of this crowd. I can see the banner of the Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionaire, portraits of Castro and Che Guevara, the banner of the FER, several banners of ‘Servir le Peuple’ (a Maoist group). and the banner of the UJCML (Union de Ia Jeunesse Communiste Marxiste-Léniniste), another Maoist tendency. There are also banners from many educational establishments now occupied by those who work there. Large groups of lichens (high school kids) mingle with the students as do many thousands of teachers. At about 2pm the student section sets off, singing the ‘Internationale’. We march 20–30 abreast, arms linked. There is a row of red flags in front of us, then a banner 50 feet wide carrying four simple words: ‘Etudiants, Enseignants, Travailleurs, Solidaires’. It is an impressive sight.

The whole Boulevard de Magenta is a solid seething mass of humanity. We can’t enter the Place de la République, already packed foil of demonstrators. One can’t even move along the pavements or through adjacent streets. Nothing but people, as far as the eye can see. As we proceed slowly down the Boulevard de Magenta, we notice on a third floor balcony, high on our right, an SFIO (Socialist Party) headquarters, The balcony is bedecked with a few decrepit-looking red flags and a banner proclaiming ‘Solidarity with the students’. A few elderly characters wave at us, somewhat self-consciously, Someone in the crowd starts chanting “O-pur-tu-nistes”. The slogan is taken up, rhythmically roared by thousands, to the discomfiture of those on the balcony who beat a hasty retreat, The people have not forgotten the use of the CRS against the striking miners in 1958 by ‘socialist’ Minister of the Interior Jules Moch, They remember the ‘socialist’ Prime Minister Guy Mollet and his role during the Algerian War. Mercilessly, the crowd shows its contempt for the discredited politicians now seeking to jump on the bandwagon. “Guy Mollet, au musée”, they shout, amid laughter. It is truly the end of an epoch. At about 3pm we at last reach the Place de Ia République, our point of departure, The crowd here is so dense that several people faint and have to be carried into neighbouring cafes, Here people are packed almost as tight as in the street, but can at least avoid being injured, The window of one café gives way under the pressure of the crowd outside, There is a genuine fear, in several pads of the crowd, of being crushed to death. The first union contingents fortunately begin to leave the square. There isn’t a policeman in sight. Although the demonstration has been announced as a joint one, the CGT leaders are still striving desperately to avoid a mixing-up, on the streets, of students and workers. In this they are moderately successful. By about 4.3Opm the students’ and teachers’ contingent, perhaps 80,000 strong, finally leaves the Place de Ia République, Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators have preceded it, hundreds of thousands follow it, but the ‘left’ contingent has been well and truly ‘bottled-in’. Several groups, understanding at last the CGT’S manoeuvre, break loose once we are out of the square. They take shod cuts via various side streets, at the double, and succeed in infiltrating groups of 100 or so into pads of the march ahead of them or behind them. The Stalinist stewards walking hand in hand an. hemming the march in on either side are powerless to prevent these sudden influxes. The student demonstrators scatter like fish in water as soon as they have entered a given contingent. The CGT marchers themselves are quite friendly and readily assimilate the newcomers, not quite sure what it’s ail about, The students’ appearances dress and speech does not enable them to be identified as readily as they would be in Britain.

The main student contingent proceeds as a compact body. Now that we are past the bottleneck of the Place de la République the pace is quite rapid. The student group nevertheless takes at least half an hour to pass a given point. The slogans of the students contrast strikingly with those of the CGT. The students shout “Le Pouvoir aux Ouvriers” (All Power to the Workers); “Le Pouvoir est dens Ia rue” (Power lies in the street)’,”‘Libérez nos camarades”. COT members shout “Pompidou, démission” (Pompidou, resign). The students chant “de Gaulle, assassin”, or ‘ICRS-SS”. The CGT: (‘Des soul, pas de matraques” (money, not police clubs) or “Défense du pouvoir d’achat” (Defend our purchasing power) The students say “Non à l’Université de classe”. The CGT and the Stalinist students, grouped around the banner of their paper Claret reply “Université Démocratique”. Deep political differences lie behind the differences of emphasis. some slogans are taken up by everyone, slogans such as “Dix ens, c’est assez” ,“A bas I’Etat policier”, or “Bon anniversaire, mon Général”. Whole groups mournfully intone a well-known refrain: “Adieu, de Gaulle”. They wave their handkerchiefs, to the great merriment of the bystanders. As the main student contingent crosses the Pont St Michel to enter the Latin Quarter it suddenly stops, in silent tribute to its wounded. All thoughts are for a moment switched to those lying in hospital, their sight in danger through too much tear gas or their skulls or ribs fractured by the truncheons of the CRS. The sudden, angry silence of this noisiest pad of the demonstration conveys a deep impression of strength and resolution. One senses massive accounts yet to be settled.

At the top of the Boulevard St Michel I drop out of the march, climb onto a parapet lining the Luxembourg Gardens, and just watch. l remain there for two hours as row after row of demonstrators marches past, 30 or more abreast, a human tidal wave of fantastic, inconceivable size, How many are they? 600,000? 800,000? A million? 1 ,500,000? No-one can really number them. The first of the demonstrators reached the final dispersal point hours before the last ranks had left the Place de Ia République, at 7pm. There were banners of every kind: union banners, student banners, political banners, non-political banners, recordist banners, revolutionary banners, banners of the ‘Mouvement contra -Armement Atomique’, banners of various Conseils de Parents d’Elèves, banners of every conceivable size and shape, proclaiming a common abhorrence at what had happened and a common will to struggle on. Some banners were notedly applauded, such as the one saying ‘Libérons’information’(let’s have a free news service) carried by a group of employees from the ORTF. Some banners indulged in vivid symbolism, such as the gruesome one carried by a group of artists, depicting human hands. heads and eyes, each with its price tag, on display on the hooks and trays of a butcher’s shop. Endlessly they filed past, There were whole sections of hospital personnel, in white coats, some carrying posters saying ‘Où sent les dispartls des hopitatlx?’ (where are the missing injured?). Every factory, every major workplace seemed to be represented, There Were numerous groups of, railwaymen, postmen, printers, Metro personnel, metal workers, airport workers, market men, electricians, lawyers, supermen, bank employees, building workers, glass and chemical workers, waiters, municipal employees: painters and decorators, gas workers, shop girls, insurance clerks, road sweepers, film studio operators, busmen, teachers, Sharkers from the new plastic industries, row upon row upon row of them, the flesh and blood of modern capitalist society, an unending macs, a power that could sweep everything before it, if it but decided to do so, My thoughts went to those who say that the workers are only interested in football, in the ‘tiercé’ (horse-betting), in watching the telly and that the working class , in their annual ‘conges’ (holidays), cannot see beyond the problems of its everyday life. It was so palpably untrue. I also thought of those who say that only a narrow and rotten leadership lies between the masses and the total transformation of society. It was equally untrue. Today the working class is becoming conscious of its strength. Will it decide, tomorrow, to use it?

I rejoin the march and we proceed towards Dented Rochereau. We pass several statues, sedate gentlemen now bedecked with red flags or carrying slogans such as ‘Libérez nos camarades’. As we pass a hospital silence again descends on the endless crowd. Someone starts whistling the ‘lnternationale’, Others take it up. Like a breeze rustling over an enormous field of corn, the whistled tune ripples out in all directions. From the windows of the hospital some nurses wave at us.

At various intersections we pass traffic lights which by some strange inertia still seem to be working. Red and green alternate, at fixed intervals, meaning as little as bourgeois education, as work in modern society, as the lives of those walking past. The reality of today, for a few hours, has submerged all of yesterday’s patterns. The part of the march in which l find myself is now rapidly approaching what the organizers have decided should be the dispersal point. The CGT is desperately keen that its hundreds of thousands of supposers should disperse quietly, It fears them, when they are together. It wants them nameless atoms again, scattered to the four corners of Paris, powerless in the context of their individual preoccupations. The COT sees itself as the only possible link between them, as the divinely ordained vehicle for the expression of their collective viii. The ‘Mouvement du 22 Mars’, on the other hand, had issued a call to the students and workers, asking them to stick together and to proceed to the lawns of the Champ de Mars (at the foot of the Eiffel Tower) for a massive collective discussion on the experiences of the day and on the problems that lie ahead.

At this stage I sample for the first time what a ‘service d’ordre’ composed of Stalinist stewards really means. AII day, the stewards have obviously been anticipating this particular moment. They are very tense, clearly expecting ‘trouble’. Above all else they fear what they call ‘débordement’, ie being outflanked on the left. For the last half-mile of the march five or six solid rows of them line up on either side of the demonstrators. Arms linked, they form a massive sheath around the marchers. CGT officials address the bottled-up demonstrators through two powerful loudspeakers mounted on vans, instructing them to disperse quietly via the Boulevard Arago, ie to proceed in precisely the opposite direction to the one leading to the Champ de Mars. Other exits from the Place Denfert Rochereau are blocked by lines of stewards linking arms On occasions like this, l am told, the Communist Party calls up thousands of its members from the Paris area. It also summons members from mites around, bringing them up by the coachload from places as far away as Rennes, Orleans, Sens, Lille and Limoges. The municipalities under Communist Party control provide further hundreds of these ‘stewards’ not necessarily Party members, but people dependent on the goodwill of the Party for their jobs and future. Ever since its heyday of participation in the government (1945–47) the Party has had this kind of mass base in the Paris suburbs. It has invariably used it in circumstances like today. On this demonstration there must be at least 10,000 such stewards, possibly twice that number. The exhortations of the stewards meet with a variable response. Whether they are successful in getting particular groups to disperse via the Boulevard Arago depends of course on the composition of the groups. Most of those which the students have not succeeded in infiltrating obey, although even here some of the younger militants protest: “We are a million in the streets. Why should we go home?” Other groups hesitate, vacillate, start arguing. Student speakers climb on walls and shout: “‘AII those who want to return to the telly, turn down the Boulevard Arago. Those who are for joint worker-student discussions and for developing the struggle, turn down the Boulevard Raspail and proceed to the Champ de Mars”. Those protesting against the dispersion orders are immediately jumped on by the stewards, denounced as ‘provocateurs’ and often man-handled. I saw several comrades of the ‘Mouvement du 22 Mars’ physically assaulted, their portable loud hailers from their hands and their leaflets torn from them and thrown to the ground. In some sections there seemed to be dozens, in others hundreds, in others thousands of ‘provocateurs’. A number of minor punch-ups take piece as the stewards are swept aside by these particular contingents. Heated arguments break out, the demonstrators denouncing the Stalinists as ‘cops’ and as ‘the last rampart of the bourgeoisie’.

A respect for facts compels me to admit that most contingents followed the orders of the trade union bureaucrats. The repeated slanders by the CGT and Communist Party leaders had had their effect. The students were “trouble-makers” “adventurers” “dubious elements”. Their proposed action would only lead to a massive intervention by the CRS’ (who had kept well out of sight throughout the whole of the afternoon). “This was just a demonstration, not a prelude to revolutions” Playing ruthlessly on the most backward sections of the crowd, and physically assaulting the more advanced sections, the apparatchiks of the CGT succeeded in getting the bulk of the demonstrators to disperse, often under protest. Thousands went to the Champ de Mars, But hundreds of thousands went home. The Stalinists won the day, but the arguments started will surely reverberate down the months to come.

At about 8pm an episode took place which changed the temper of the last sections of the march, now approaching the dispersal point. A police van suddenly came up one of the streets leading Into the Place Denfert Rochereau. It must have strayed from its intended route, or perhaps its driver had assumed that the demonstrators had already dispersed. Seeing the crowd ahead the two uniformed gendarmes in the front seat panicked. Unable to reverse in time in order to retreat, the driver decided that his life hinged on forcing a passage through the thinnest section of the crowd. The vehicle accelerated: hurling itself into the demonstrators at about 50 mikes an hour. People scattered wildly in alt directions. Several people were knocked down and two were seriously injured. Many more narrowly’ escaped, The van was finally surrounded. One of the policemen in the front seat was dragged out and repeatedly punched by the infuriated crowd, determined to lynch him. He was finally rescuers in the nick of time, by the stewards. They more or less carried him, semi-conscious, down a side street where he was passed horizontally, like a battered blood sausage, through an open ground floor window.

To do this, the stewards had had to engage in a running fight with several hundred very angry marchers. The crowd then started rocking the stranded police van. The remaining policeman drew his revolver and fired. People ducked. By a miracle no-one was hit. A hundred yards away the bullet made a hole, about three feet above ground level, in a window of ‘Le Belfort’, a big café at 297 Boulevard Raspail. The stewards again rushed to the rescue, forming a barrier between the crowd and the police van, which was allowed to escape down a side street, driven by the policeman who had fired at the crowd.

Hundreds of demonstrators then thronged round the hole in the window of the cafe. Press photographers were summoned, arrived, duly took their close-ups — none of which, of course, were ever published, (Two days later l’Humanité carried a few lines about the episode, at the bottom of a column on page 5.) One effect of the episode is that several thousand more demonstrators decided not to disperse. They turned and marched down towards the Champ de Mars, shouting “lls ont tiré à Denfert” (they’ve shot at us at Denfert). If the incident had taken place an hour earlier, the evening of 13 May might have had a very different complexion.

#May Day#labor#solidarity#anarchism#history#france#paris#french politics#resistance#autonomy#revolution#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#anarchy#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economics#anarchy works

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Catacombs of Paris are an extensive network of underground ossuaries that hold the remains of more than six million people. They are located in the city of Paris, France, and are a significant historical and cultural site. Here are some key points about the Catacombs:

Origins: The catacombs were created in the late 18th century as a solution to the city's overflowing cemeteries. The decision to move the remains to the underground quarries was made in 1786 due to health concerns related to the overcrowded cemeteries.

Quarries: The tunnels and caverns that make up the catacombs were originally part of limestone quarries dating back to Roman times. These quarries were later repurposed to house the bones of the deceased.

Transfer of Remains: The transfer of bones from various Parisian cemeteries began in 1786 and continued into the 19th century. The remains were moved at night in a ceremonial procession and deposited in the catacombs.

Layout: The catacombs stretch over 200 miles beneath Paris, although only a small portion is open to the public. The section open to visitors is about 1.5 kilometers (approximately 1 mile) long and is located 20 meters (65 feet) below the streets of Paris.

Tourist Attraction: The catacombs were opened to the public in the early 19th century. Today, they are a popular tourist attraction, drawing visitors from around the world who are fascinated by the macabre and historical aspects of the site.

Unique Features: The catacombs are known for their neatly arranged bones and skulls, which form walls and decorative patterns. There are also inscriptions and plaques throughout the catacombs that provide information about the original cemeteries and the transfer process.

Access: The official entrance to the catacombs is located at 1 Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, near the Denfert-Rochereau metro station. Due to the narrow and confined spaces, visitors should be prepared for a dark and potentially eerie experience.

Preservation: The catacombs are carefully maintained to preserve the historical integrity of the site. Visitors are advised to respect the rules and refrain from touching the bones or taking souvenirs.

The Catacombs of Paris offer a unique glimpse into the city's history and the ways in which it has dealt with the practical and spiritual concerns of death and burial.

3 notes

·

View notes