#Roman Military & Warfare

Text

National Museums Scotland has just announced the extraordinary reconstruction of an 1,800-year-old Roman arm guard. The artifact has been described as “absolutely amazing.”

However, since its initial discovery within the Scottish Borders in 1906, the armor, shattered into over 100 pieces, languished in relative obscurity until experts meticulously reassembled it, much like a jigsaw puzzle.

This brass relic likely adorned a high-ranking Roman soldier, gleaming like gold on his arm. Currently on loan to the British Museum, you can find it at the upcoming exhibition "Legion: Life in the Roman Army" starting February 1, 2024!

#armor#Romans#Scottish Borders#Britannia#Scotland#Roman Military & Warfare#Roman Technology#ancient#history#ancient origins

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

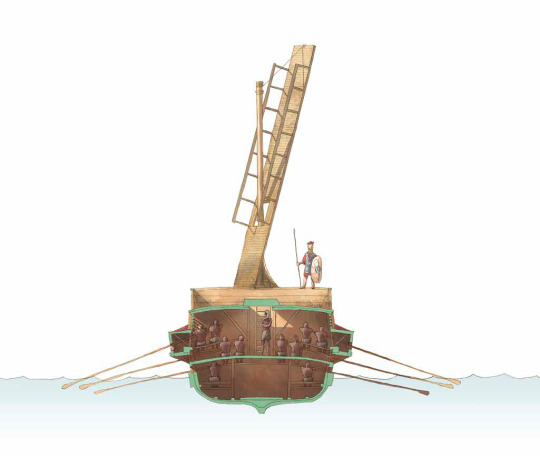

Crosscut of the quinquereme, the warship that was ubiquitous in ancient navies. It had a set of three oars on each side, handled by five rowers, hence the name.

Contrary to the popular image of slaves rowing these ships, the majority of the rowers were free albeit poor citizens as it required skill and experience.

This particular quinquereme is equipped with the so-called "Corvus", a boarding device invented and employed by Romans to great effect in the First Punic War.

(Image Source: Ancient Warfare Magazine)

#ancient rome#ancient world#ancient civilizations#ancient culture#ancient greece#punic wars#corvus#warship#ancient warfare#the roman republic#military technology#ancient military#ancient warship

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sassanian Military, at its peak, was one of the world’s most formidable. Under the command of the Ērān-Spahbad, the division of Ērānshahr’s armies was usually as follows:

1. Paygān: Light conscript infantry armed with wicker or leather shields and short spears. In times of struggle, conscripted farmers may have used agricultural tools such as pitchforks or sickles. Some conscripts came from far-flung provinces and brought their foreign military traditions with them, such as the Kurds, Anatolians, Armenians, and Arabs. The Daylamites, from the Caspian province of Daylam, were particularly famed for their prowess in hand-to-hand and close-quarters combat.

2. Foot Archers: Often conscripted, though instruction in archery required more training time, making these soldiers slightly more elite. For this reason, standing archers’ ranks were divided between Kamāndār-ī-Pāyahdag (conscripts) and Kamāndār-ī-Shahi (professionals or nobles)

3. Cavalry Archers (not pictured): Carrying over the tradition of their Arsacid predecessors, Sassanian armies often rode with a large contingent of light cavalry archers for their maneuverability and potential for ranged weakening of enemy forces. These archers would dress in lighter clothing than their heavy cavalry counterparts and were armed with the mighty composite bow, which could be drawn and fired quickly and while in motion.

4. Cataphracts: These heavily armored horsemen were the vanguard of every Sassanid force. Much of their ranks were comprised of elite warriors from the minor nobility, known as the Savaran. They donned full-body scale armor and full-coverage helmets, with their horses’ barding being of a similar construction. They carried many weapons, including the Kontos (an adapted version of the Greek Xyston), short and long swords, bludgeons such as maces and hammers, and even (according to one Roman source) a single-use crossbow that could discharge multiple arrows at medium range.

#history#persian history#persia#ancient persia#ancient rome#arms and armor#military history#roman history#classical history#middle east#iran#medieval warfare#medieval weapons

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hannibal is way overrated as a general. Sure he has good tactics but his strategy game was awful. Like you brought elephants? Can they siege Rome? I didn’t think so lol.

#siege warfare#hannibal barca#military history#history#carthage#punic wars#warfare#elephant#roman republic

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Romans versus “Barbarians”: A Military Comparison, Part Two

An Original Essay of Lucas Del Rio

Note: This is the second installment of an essay that will be four parts in total. The previous installment has already been posted on my blog. Each section chronologically covers the wars fought by the Romans in the events leading up to the dawn of the Middle Ages. A special focus is on how both the Romans and their adversaries, whom the former referred to the latter as “barbarians,” fought in terms of tactics and weaponry. In this segment of the essay, the focus will be on the Roman wars with the Carthaginians, Iberians, Macedonians, and Seleucids.

The Roman Republic was in a strong position once it had secured control over all of Italy. However, it was not yet at this point the dominant power in the Mediterranean, or even in the western Mediterranean. For several centuries prior to the Roman unification of Italy, the title of being the greatest Mediterranean realm had belonged to Carthage. Located in modern Tunisia, the city of Carthage was initially founded by Phoenicians. A culture that emerged in the Bronze Age, the Phoenicians were Canaanites in the Levant who spoke a Semitic language. Their early history is poorly documented, but at their peak, they were expert sailors and traders. Some Phoenicians traveled as far as the Atlantic. Folklore states that a Phoenician queen, whose name has been disputed, founded Carthage in 814 BC. If this is true, the city was founded sixty-one years before the Romans claimed that their own city was established. Some historians believe that the conquest of the Levant in 538 BC by Persian King Cyrus the Great caused many Phoenicians to settle elsewhere, including in Carthage.

Cyrus the Great was not the only conqueror whose actions led to an increase in the strength of Carthage while their ancestral homeland of Phoenicia declined. Later, in 332 BC, Alexander the Great seized the region from the Persians. Alexander ravaged Phoenicia, and those that were able to flee did so. In the years that followed, Carthage established vast trade routes, allowing it to grow and prosper as it sold dye, glass, and ivory throughout the Mediterranean. The Carthaginians had formed an empire by the 600s BC with colonies across North Africa. These endeavors led them to build a feared and formidable navy. They also developed a military, learning to vigorously utilize javelin throwing cavalry from their allies, the neighboring Numidians. Like many empires at the time, the Carthaginians employed chariots early on and would increasingly copy Greek and Macedonian phalanxes. During this point in history, there were still elephants in North Africa, and they trained these elephants for battle. Carthaginian war elephants were armored, had their tusks outfitted with sharp objects, and usually carried two soldiers.

The Carthaginian army included native Carthaginians, who occupied all leadership roles. However, the bulk of its forces were foreign mercenaries. These included Balearic slingers, both Celtic and Iberian swordsmen, Cretan archers, and Libyan warriors who fought with axes. Eventually, these soldiers would end up fighting the Romans, although the two cultures had not always been enemies. In fact, prior to the Punic Wars, their societies had been close trade partners who were generally on positive terms. At the time that the Romans had largely secured control of mainland Italy, the nearby island of Sicily was almost entirely Carthaginian territory. This may have allowed both empires to do business with one another, but the close proximity of the island and the peninsula began to spark tensions. Pyrrhus had remarked after his defeat in Italy by the Romans that war between Carthage and Rome war was inevitable.

The Punic Wars would not be the first time that Carthage had experienced a major military confrontation. Prior to the Punic Wars, the Carthaginians had to fight a Greek general named Agathocles. A former mercenary, it was actually with their help that Agathocles was able to establish his own military dictatorship. In 317 BC, he seized power in Syracuse, a colony of the Greek city-state of Corinth and the only major city on the island of Sicily other than Acragas not controlled by the Carthaginian Empire. Still not content, Agathocles invaded other cities on the island. While the Carthaginians managed to repel these attacks, Agathocles was able to escape with sixty ships before Syracuse could be captured. By doing so, he managed to bring fourteen thousand soldiers to Africa. At this time, Carthage was battling an uprising, plus its soldiers in Sicily were struggling to take Syracuse despite the absence of its leader. Agathocles was making impressive progress in conquering cities belonging to Carthage, but he went back to defend Syracuse once he realized his city was beginning to fall. He was forced to sign a peace treaty with the Carthaginians in 306 BC and agreed to give them their cities back, although he continued to conduct military campaigns elsewhere for the duration of his life.

Like the war that the Carthaginians were forced to fight against Agathocles, the starting battleground of the First Punic War would be in Sicily. It began as a proxy war, as the Romans became involved in a power struggle on the island concerning Carthage. Mercenaries known as the Mamertines previously had employment with the monarchy in Syracuse. After their work for the city had concluded, they chose to seize control of a different city known as Messina. In an attempt to avoid facing the wrath of Carthage, the Mamertines went to the Roman Senate to seek an alliance. Even though Carthage and Rome had not previously been adversaries, the Romans now saw an opportunity to expand into Sicily and in 264 BC sent soldiers. Before long, the two empires had entered a state of open warfare. Both sides knew the strengths of their opponent and thus tried to keep the combat that they excelled at. Carthage had the advantage of a highly formidable navy, whereas serious naval warfare was something that the Romans had never previously experienced. On the other hand, the Carthaginians, with their dependence on foreign mercenaries, lacked a land formation of their own that could compete with Roman warriors, who fought in legions.

The Carthaginian advantage at sea would not last long against the industrious Romans. Ships captured by the Romans were examined by Roman engineers, who learned how they could build their own. Unlike the Carthaginians, who sunk enemy ships with rams attached to their own, the Romans employed the tactic of boarding the Carthaginian ships with legionnaires. As the war went on, the Romans won battle after battle despite the brave efforts of Hamilcar Barca, a commander who is still celebrated in the field of military history. Because the situation in Sicily remained a stalemate, the Roman army invaded Africa directly in 256 BC. Carthage sought the help of a Spartan military commander by the name of Xanthippus, who helped repel the Roman onslaught, yet it was still not enough for Carthage to win the war. In 241 BC, the Carthaginians surrendered and were forced to give up Sicily, plus give the Romans tribute. However, despite this surrender, the Carthaginian Empire retained its sovereignty, as it had not yet been defeated.

Much of what happened in the years following the First Punic War were not kind to Carthage. As Sicily had been one of its most important trade destinations, funds were lacking to pay the mercenaries that composed much of the Carthaginian army. Between 240 and 237 BC, a conflict occurred known as “the Mercenary War” in which many of their mercenaries revolted. While Carthage managed to defeat the rebels, the Romans took advantage of the situation to seize Corsica and Sardinia, two other major islands in the Mediterranean. The sea had become dominated by the Romans, who were now an unmatched naval power. However, the Carthaginians were still trying to reestablish themselves as a major power. They decided to colonize the Iberian Peninsula, where they founded various settlements, including the city of Cartagena in 228 BC that still stands today. Hamilcar Barca, the aforementioned general, played an active role in Carthaginian military operations in Iberia. His son, Hannibal, and his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, followed in his footsteps.

Peace between the two cultures would not last. Hamilcar died in 228 BC, but both Hannibal and Hasdrubal would continue fighting for the empire they served. Silver mines captured in Iberia eased the strain on the Carthaginian economy that had been caused by the tribute owed to the Romans. The silver also allowed for the military to expand again. With Carthage resurgent, the empire would soon strike back. Rome, having recently defeated Celtic allies of Carthage to the north of Italy, were not worried about the possibility of another war. Hannibal led an army to seize a town in Iberia called Saguntum in 219 BC, which startled the Romans, as the Saguntines were their ally. However, while the move provoked Rome, nothing about this particular action by the Carthaginians was in violation of any diplomatic treaty between the two societies. If anything, the Romans had acted illegally by allying with these people, as the town was in a location that both sides agreed was to be reserved for the Carthaginians. Rome demanded that Carthage extradite Hannibal, which they did not. It was the start of the Second Punic War in 218 BC, in which the Romans would see plenty more of Hannibal.

Hannibal first gathered an army in Iberia, which included many Iberian mercenaries. Prior to his death, Hamilcar had been trying to build a more effective army for Carthage after the defeat in the First Punic War had largely been the result of a weak one. Due to the strong presence that the Carthaginians now had on the Iberian Peninsula, recruiting the locals for the new war would have been a logical choice. Most obviously, the region was fairly close to Italy, which Hannibal intended to invade. Additionally, the Iberians were fierce warriors who had mastered fighting as both infantry and cavalry. Like their Roman counterparts, Iberian infantry carried large shields, were heavily armored, and threw javelins at their enemies before charging. By the time of the Second Punic War, it had become clear that Roman legionnaires were some of the best melee infantry in the known world. However, the Iberians had some advantages in melee combat. Legionnaires were still generally armed with spears, and those that fought with swords still carried a now outdated variety long used in Greece. Years later, legionnaires started to be equipped with a type of sword that they called the “gladius hispanicus,” a weapon, based on the Iberian “falcata,” that would also famously become common in brawls between gladiators.

As previously stated, the Iberians were also very skilled at fighting on horseback. Like the Spanish cavalry that would later exist in the region many centuries later, the Iberians had a combination of both heavy and light cavalry. Whereas the heavy cavalry wielded both lances and their signature swords, the light cavalry threw javelins. Hannibal, of course, had a variety of soldiers in the army that he amassed to invade Italy, with ninety thousand infantry and twelve thousand cavalry. He also mustered forty war elephants. Carthaginian war elephants had previously been of the variety indigenous to North Africa, but it has been theorized that Hannibal acquired Asian elephants for his campaign against Rome. If this is true, the elephants were likely supplied by the Ptolemies, the dynasty that then ruled Egypt. The Ptolemies were on friendly terms with Carthage and had trade routes with the east.

The Second Punic War was arguably the greatest threat to Rome for centuries to come. Hannibal knew that he could not give Rome the chance to invade Africa, as it had done to win in the First Punic War. He therefore decided that his first move would be to march his troops directly from Iberia to Italy. In doing so, the army commanded by Hannibal had to cross over the Alps, which resulted in twenty thousand soldiers dying. It was probably especially disappointing to Hannibal that only one elephant survived the journey. However, this did not stop him. Rome expected his weakened army to be defeated quickly, but Hannibal proved to be a tactical genius and won countless battles. His army wandered and ravaged Italy until 203 BC. Like Pyrrhus years earlier, the main reason for his defeat was his inability to replenish fallen troops after major battles. Carthage did little to provide support to Hannibal, and he failed to find many allies among conquered Italians that he expected would want an opportunity to revolt.

Rome would defeat Carthage in a similar manner that they won the first time. After Hasdrubal failed in an attempt to reinforce Hannibal, the Romans invaded Iberia and then Africa, conquering all of the Carthaginian Empire except for its capital city. Hannibal had arrived with his army, but it was too late. In 202 BC, Carthage was forced to agree to another humiliating peace treaty. From 149 to 146 BC, there would be a Third Punic War, which occurred when Rome was making various rather absurd demands. Perhaps the most bizarre of these was that the Romans wanted the Carthaginians to abandon their city and found a new one further away from the sea. Carthage had also declared war on the Numidians, which the Carthaginians were forbidden to do according to the prior peace treaty. This time, Carthage was very weak, and the Romans chose to raze the city once and for all.

During the lengthy span of time that the Roman Republic waged war against Carthage and its colonies, the world of classical antiquity saw other violent conflicts elsewhere. Several dynasties with roots in wars that had occurred decades before the Romans united Italy would be among the next barriers to Roman expansion. The story of these dynasties begins with Alexander the Great, the Macedonian conqueror who defeated the entirety of the Persian Empires. His death in 323 BC without an heir left the mighty realm that he had built without anyone to succeed him. Decades of violence they called “the Wars of the Diadochi” followed, with several former generals of Alexander carving out pieces of his domain. Even his homeland of Macedon was not spared. Macedon and its new line of rulers became known as “the Antigonid Dynasty,” even though Antigonus was killed in one of the wars. Philip V, who was one such ruler, went to war with the Romans in 215 BC in hopes that he could help Carthage contain the rising power of Rome.

Ten years after the start of the first of the Macedonian Wars, Rome made peace with Macedon. Unlike the Carthaginians, who had lost territory fighting the Romans, Philip V was able to gain some. However, further warfare between Macedon and Rome would favor the latter. The Macedonians began to militarily annex various Greek city-states in violation of the peace treaty, prompting a declaration of war by Rome in 200 BC. Rome brought elephants, which along with Roman legions, the Macedonian phalanxes were helpless against. By 196 BC, Rome had won, and the Romans assumed control of most of Greece. An additional two wars also ended in Macedonian defeats, with the ultimate result being full Roman control of the region. Another, more powerful successor state to the realm of Alexander the Great, known as “the Seleucid Dynasty,” also fell victim to Rome and its legions.

#ancient#ancient rome#ancient warfare#antiquity#civilization#classical antiquity#classical era#classical warfare#essay#history#legion#military history#punic wars#roman republic#rome#society#tactics#war#warfare#warriors

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Emperor's Sword' Book Review By Ron Fortier

New Post has been published on http://esonetwork.com/emperors-sword-book-review-by-ron-fortier/

'Emperor's Sword' Book Review By Ron Fortier

EMPEROR’S SWORD

The Imperial Assassin Book 1

By Alex Gough

Canelo US

358 pgs

Silus is a half-breed Roman scout comfortable in the wild northern terrain of Caledonia. One fateful mission ends with his murdering a regional chieftain. This reckless act in turn starts a chain of events that has dire consequences for the Empire. The retaliation for his rash act results in further barbarian raids and in one attack his wife and daughter are killed. Lost in a sea of grief and despair, Silus comes to the attention of Caracalla, one of the triumvirate rulers. Seeing potential in the scout, Caracalla has him assigned to the veteran spymaster Marcus Oclatinuis; the chief of an elite spy faction known as the Arcani. They are the assassins of the empire.

What follows is a truly memorable historical action-adventure filled with colorful characters and gut-wrenching battles as two different cultures vie for supremacy. The prize of their war was the island continent of what would one day be Great Britain. Gough’s history is impeccable and enriches his tale greatly. The characters come to life as does the savagery of the times. He brutally displays the insanity of war and the vagaries of the human experience both in its nobility and its depravity.

This is a remarkable book and only the first in a series. One we are eager to follow.

#Alex Gough#Alex Gough author review#Alex Gough book#Ancient Roman culture#Ancient Rome literature#Ancient warfare literature#book review#Book review discussion#Canelo US#Emperor's Sword#Emperor's Sword analysis#Emperor's Sword review#ESO Book Review#ESO Network#Fictional Roman battles#Historical fiction fandom#Historical fiction podcast#Historical fiction review#Historical novel analysis#Historical novel podcast#Military fiction critique#Roman Empire novel#Roman Empire storytelling#Roman history exploration#Roman legion adventure#Roman military tactics#Ron Fortier

0 notes

Text

“Pinning down rules of thumbs on how many officers an army needs (again, including both NCOs and commissioned officers), by contrast, is relevant but deceptive. Students (and occasionally scholars) can easily enough notice that the ratio of officers to soldiers (‘rankers’ we might say) has gone up steadily overtime since the early modern period, at the same time that armies to became capable of progressively more complex operations. The inference is easy to draw: a higher ratio of officers (that is, more officers) corresponds to a greater capability to execute complex plans.

And in the very broad strokes this seems to be true. The Spartans, our sources note (Thuc. 5.68; Xen. Lac. 11.4-5) had more organizational divisions commanded by more officers than other contemporary hoplite formations and seem also to have been able to maneuver a bit better than other hoplite formations, albeit still nowhere near what would be possible for later Roman or Macedonian armies.

It’s difficult to precisely parse out the organization (in part because Thucydides and Xenophon differ in some details), but Xenophon gives the mora as the large scale unit (estimated around 576 men; six of which made up the army), each of which had 29 officers (see chart below), so one officer for each 19 or so regular Spartiates.

As Xenophon notes, this greater degree of organization with many smaller units nested in larger units enabled the Spartans to perform maneuvers thought by the Greeks to be quite difficult to do. This is succeeding over a very low bar, since a hoplite phalanx was one of those formations which struggled to do much more than march forward in a line, but it still speaks to the importance of officers.

Fast Forward to the organization of the Macedonian army under Philip II and Alexander and by all indications the system has become more sophisticated, with an even greater number of officers. We don’t have a description of the detailed structure of Alexander’s army, but what we do have is a later description by a philosopher, Asclepiodotus, of an ‘ideal’ sarisa-phalanx for the later Hellenistic period. The basic unit, the syntagma, consisting of 256 men as he describes it has eighty various officers (many of which we would classify as NCOs, but again we’re not making those distinctions here). That’s now one officer for every 2.2 regular soldiers.

Those syntagma were then grouped into larger formations; under Alexander these were the taxeis, of which there were six. In later Hellenistic armies, particular parts of the phalanx are specified by their shields or commanders, but we often have limited visibility into the subdivisions of the phalanx. Again, it is worth warning that we cannot be sure the degree to which Asclepiodotus may have embellished this system, but it does seem to be accurate in the broad outlines at least.

And we know from Alexander’s campaigns and the subsequent wars of his successors that this was a much more flexible, reactive formation than any hoplite phalanx. Alexander is able to do things like refuse his left flank (to give himself more time to win on the right) and later Hellenistic phalanxes are able to do things like form square under combat conditions (App. Syr. 35), while often operating with attached light infantry and cavalry support. This was a clockwork mechanism substantially more complicated than anything the poleis of Greece had put together on land and it demanded a lot more officer accordingly.

So it seems like we have a pretty clear pattern from most hoplites to Spartiates to Macedonians that ‘more officer’ means ‘more reactive and flexible formation.’ And indeed, some scholars have noted such. And then we get to the Romans.

There is little question that the Roman legion of the Middle Republic was a more flexible, reactive adaptable fighting formation than the Hellenistic phalanxes it faced. Our sources tell us as much (Plb. 18.31-32; Liv. 44.41.6) and that same conclusion emerges pretty clearly in both the battle narratives we have in our understanding of how the legion was expected to function in battle (discussed last time).

Even the basic mechanics of the legion’s fighting method – the three ranks engaging in sequence, forming and closing gaps as they do – appears well beyond the capabilities of the Hellenistic phalanx (and indeed this leads the latter to struggle and eventually fail to cope with the former). And while as a rule the Hellenistic phalanx maneuvers by taxeis, in the legion notionally the maniples could be independent maneuvering units as the fight shifted from hastati to principes to triarii; a much smaller unit of maneuver.

So we ought, by the theory, to have yet more officers still, right? And yet we don’t! The legion (or 4,200 or so excluding cavalry) is divided into thirty maniples, each split into two centuries. Each century was commanded by a centurion so that gives us sixty centurions; centurions were organized in seniority order, so they are not all peers but organized in a hierarchy.

Above this was the commander himself (holding imperium; a consul, praetor, proconsul or propraetor) along with a number of military tribunes (frequently junior aristocrats, typically six per legion these fellows could be delegated to command a legion in battle), the praefecti sociorum, Romans put in command of the allied units and the assigned quaestor who handled pay and finance but might also be asked to command in a pinch.

Below the centurions, we have attested in the imperial period the decani, each of whom commanded a contubernium or ‘tent group’ of six men. The contubernium but not the decanus is attested for the period of the Republic, but I tend to think that there must have been decani in the Republic too; as the commanders of six men they’d probably double as file-leaders since the standard Roman file was of six.

The legionary cavalry (just 300 per legion; the Romans liked to rely more on allied cavalry) were divided into ten turmae (of 30) each commanded by three decuriones (so that’s 30 decuriones total). That means for a standard double-legionary army (9,000 Romans, we’ll put the socii and their praefecti to the side) had 1 commander, 1 quaestor, 12 military tribunes, 60 decuriones, 120 centurions and perhaps 1,200 decani; 1,394 officers for 7,606 regular soldiers, a ratio of around 1 officer to every five and a half soldiers.

That is decidedly less than the Hellenistic phalanx and yet the Roman legion is, as noted, more flexible and response than the Hellenistic phalanx. There must be some key element we are missing here. And indeed, there is.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Commanding Pre-Modern Armies, Part IIIb: Officers.”

1 note

·

View note

Note

So happy you're back after all this time! I have a question, do you happen to know how people fought in ancient rome? Particularly gladiators and soldiers? Sorry if this isn't the blog for this question tho!

I think we've covered both of these questions independently over the years.

Gladiators were a performance sport. It was more about glorifying the Roman Empire and its victories, than a conventional fight. As a result, most Gladiators were armed with specific variant, “loadouts,” designed to cosplay as various enemies that The Empire had conquered, and they only fought against specific countering variants. Specifically, the variants would be matched in such a way that it would be difficult for either combatant to have a decisive advantage over the other, with an eye towards creating situations that would result in a lot of visible injuries, without serious harm to either participant.

In case it needs to be said, gladiators were a significant financial investment, and they weren't casually killed in the arena. The point was for visible injuries, and a bloody spectacle, not a slaughter. Sometimes someone would die, but having them die on the field wasn't the intention, and they generated a lot of money, and on the rare cases when they were killed, it was meant to be a climactic moment, not someone taking a blade to the gut and collapsing mid-fight.

Obviously, I'm barely scratching the surface here, because it gets a lot deeper, but the simple answer is that in the vast majority of cases, gladiators were armed with weapons that were designed to make seriously harming their foe difficult to impossible. Also, the gladiators were something that evolved and became more complicated over time. When they first started in the Republic, it was a much more stripped down structure with prisoners of war being given a sword and shield and forced to face off against one another.

As for the Roman Legions. I'm not sure I've ever seen a comprehensive description of their training techniques. The Testudo, (or Tortoise) is one of the more famous examples of their specific combat style. Legionaries would create a shield wall, and the soldiers behind the front line would raise their shields to cover the formation against attacks from above (usually arrow fire, or thrown spears.) While being able to strike with javelins. In practice, the formation had issues, including being vulnerable to siege fire, and mounted archers were able to easily flank the formation. It's a neat story, but the formation had serious limitations.

One thing we haven't talked about before (I think) was the Roman's use of biological warfare. During sieges, they would load (locally sourced, I assume) corpses onto catapults, and then launch them into the besieged city.

Beyond, the major thing about the Legions was the extremely disciplined and orderly combat formations, with a lot of attention paid to managing battlefield movement. It wasn't so much about exceptional individual performance, so much as their ability to operate as a unit. This isn't a particularly mind blowing concept today, but in an era when professional soldiers were the exception, or limited to the elite forces, it had slightly more impact.

Regarding the details of their training, I've never seen any of that come up. Now, granted, I've really tried to research that degree of Roman history. So, if you're asking, “how, exactly, did they swing the gladius?” I don't know, and I don't remember ever seeing anyone credibly claim they had that insight. As far as I know, the only surviving Roman training manual was De Re Militari, (there's around 200 surviving Latin copies) which is far more concerned with overall strategic planning and command. If you're trying to write Roman era military fiction, it's probably worth reading. So, I'm not sure this is exactly what you were looking for, but I do hope it helps.

-Starke

This blog is supported through Patreon. Patrons get access to new posts three days early, and direct access to us through Discord. If you’re already a Patron, thank you. If you’d like to support us, please consider becoming a Patron.

#writing reference#writing advice#writing tips#how to fight write#starke answers#roman empire#history

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posts about Ancient Greek History

Things I write to help process information and assemble my notes and thoughts for future reference.

This is an ongoing project. I will add more over time.

My focus is primarily the Arkhidamian (Archidamian) War with a particular emphasis on Sparta, but I'm currently widening my focus to include the First Peloponnesian War, the Messenian Wars, and the lives of Demosthenes (the General) and Thucydides (the Historian).

Sparta

Their Culture

Spartan scholars be like

Introduction and List of Chief Sources

Becoming a Spartan Citizen, Part One: The Agoge.

Becoming a Spartan Citizen, Part Two: The Phiditia & Contributions to the Mess

Food for Warriors.

Spartan Social Structure: Part One - The Helots || Rent? Contracts?

Spartan Social Structure: Part Two - The Perioikoi

Spartan Social Structure: Part Three - Spartan Women

Spartan Social Structure: Part Four - The Hypomeiones

Stalkers in the Night: The Krypteia || Primary Sources: Krypteia

The Horses of Lakedaimon

The Spartan Political Structure: Damos, Ephors, Gerontes, Kings.

Spartan Men and their Hair || Examples of likely hairstyles

Felt Helmets

Rethinking the scale of Spartan mess and barrack buildings

Spartan Games

Ask: Did Homoioi Travel?

Military History

Background to the Third Messenian War

The Third Messenian War c. 464 BCE

The Battle of Tanagra c. 457 BCE

Maps (Mostly Related to Brasidas' Campaigns during the Arkhidamian War)

Sparta || Amphipolis 1 || Amphipolis 2 || Koryphasion (Pylos) & Sphakteria || Korinth/Nisaia || Brasidas' Campaign in Makedonia

Sparta in Pop Culture

A Cry of Frustration

Response to Anti-Spartan Sentiment

A Few Notes on God of War: Ragnarok (the Spartan Stuff)

Spartan Armour (this ain’t it)

Thinking About Spartans Thinking

A Distinction Between Sparta and Lakedaimon

Contracts? Rent?

Spartans and Their Aversion to Ranged Warfare?

Posts About Figures in the Arkhidamian War

Brasidas, Son of Tellis.

Probable Timeline of Brasidas' Life

Brasidas' Ossuary

Demosthenes, Son of Alkisthenes (The General):

As a Catalyst to the Battles of Spahkteria and Pylos?

A Few Notes

Alternative to Thucydides' Version of his Death

Thucydides, Son of Oloros (The Historian):

The Way Thucydides Thinks

A Few Notes

Posts about Polytheism and Mythology (Roman & Hellenic) :

Lakonian Royal Lineage (Mythological) || Sparta in the Catalogue of Ships || Helen, Kastor, Polydeukes

Chief Gods worshipped at Sparta (Not Ares!) || The Gods Worshipped at Sparta - further details.

Related Posts:

Roman and Hellenic Mythology: They are not the Same Thing

Mythology, the Gods and Gatekeeping: A Personal Take

Viewing History Through a Modern Lens

Graeco-Roman Art: A Cautionary Tale

#sparta#ancient sparta#ancient greece#lakedaimon#ancient history#greek history#spartan history#history posting#masterlist

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

More random Captive Prince thoughts, because I feel like being a sadist to all of my mutuals these books are living rent-free in my head right now. These ones are more about the plot and the worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding-wise, I loved the attention to detail, because as far as I could tell all the little details of how a medieval-ish army functions and how you would run it and what you would do with the horses and the supplies and the roads etc. etc. were pretty accurate. I mean, these books are by no means a treatise on warfare (in fact they can be delightfully pulpy, which I liked - I grew up on The Three Musketeers and the Scarlet Pimpernell and similar swashbuckling novels, and I got some of the same feelings here!), but there were details in there that most other authors don't bother to put in or inadvertently fuck up (I love ASOIAF to death but historically accurate it is not), and most of the military stuff seemed plausible enough as well, though again not described in too much detail so you can fill it in with your own assumptions or skim over if it's not something that particularly interests you. And I also loved the architectural details and could imagine everything quite well, but again, as I said previously, this may be because the author spent some time living near where I live so we've seen a lot of the same stuff probably.

Actually when I was first reading it and thinking it was going to be bad I was reading it exclusively for the architectural details lol, I was like yeah, yeah, they're all sucking each other off, but Damen please tell me again how you feel about the tiling?

What I also particularly liked is how the... scale of the conflict I guess? was refreshingly accurate for the "historical period".

The worldbuilding is a mashup of Ancient Greece and medieval France, but what it really felt like to me is a world where the Roman Empire never really consolidated to the extent that it did in our world and Italy went on into the middle ages (because these are decidedly feudal systems) with Cisalpine Gaul having the, well, Gallic culture, while the South had a Greek one. I may be thinking this because I live in Italy and so everything reminds me of Italy, but once I thought of it I couldn't unsee it.

I guess I gotta put in a cut somewhere and now's as good of a time as any?

But anyway, back to the scale of the conflict, the actual middle ages were filled with small and mid-sized countries, and petty local conflicts with family members turning onto each other over succession and stuff, and random small territories going back and forth (well, that's just Europe in general, always, TBH), and this is how it all felt like to me. Actual medieval history has a guy who started a rebellion because his brothers threw a pisspot at him and his father did nothing about it and he felt humiliated, and the war was secretly funded by his mother, so the combination of the small scale with a random local conflict that probably literally nobody cares about outside of the region we are in + everything being so intensely driven by interpersonal drama between insane people felt really authentic to me, like the kind of weird historical moment that would get turned into a funny Tumblr post. And of course the royals did a lot more sneaking around than was probably smart, but I can forgive that for the swashbuckling vibes and also because if Cleopatra could sneak into a palace in a carpet these guys can do whatever they want in my book.

Speaking of the petty interpersonal drama, I also liked the emphasis on how in this system personal reputation and the performance of kingship are king. Usually when you have a heavily political story it's much more based on the quid-pro-quo, "rational actor" kind of politics, but medieval politics also had a lot more going on in the cultural sense (and so do modern politics actually but at least pretending to be a "rational actor" IS the modern performance of leadership), and here you had people dealing political blows through meticulous management of their own and others' political reputations, which was fun to see, especially in combination with so many manipulative bastard characters. Like, how Laurent is manipulated into going to the border just because looking like a coward will lose him more political points than he can afford, and Damen's continued wearing of the slave cuff and instistence on not being served by slaves initially deals massive blows to his reputation, because these are cultures that value heroism, of one sort or another.

(And speaking of heroism, the emphasis on the physical activity-related activities that are the centerpiece of noble life in both countries were wonderful, especially since because both Ancient Greece and the European Middle Ages were really into that in their respective ways and it makes the mashup feel really well-done and coherent in how she tied it together.)

What's notable is a lack of any kind of religion, which felt particularly glaring during the whole Kingsmeet thing - in the real world there would likely be a belief in some kinda curse from the Gods or something similar to discourage the drawing of weapons, but since I'm not really religious and tend not to personally care about religion (while ofc recognizing its anthropological importance) I really didn't care and it didn't diminish my enjoyment of the series.

Still, I do have to say that the ending of the last book felt reeeeaally rushed, and that felt really glaring exactly because the rest of the series had such amazing detail work and excellent pacing and very gradual plot development.

I didn't get the part with the doctor and the letter (why didn't he say anything earlier? how would they verify the authenticity of the letter? Did anyone even have the time to READ the thing?) but I'm gonna be honest with you here, I read book 3 under a heavy fever and it was like 2 AM when I got to that part, so I'm not sure that I haven't missed something that makes it make more sense.

BUT even if that part makes sense, I feel like the Regent was dealt with far too quickly. Like in one paragraph he is in control of everything, in the next they've already beheaded him and that's it. I can imagine in my head that a lot of the nobles were probably already sick of him and took little convincing, that they were disapproving both of his meddling in foreign politics and of his likely grave breach of cultural rules via taking an aristo kid as a pet, or that he initially rationally seemed a better choice over Laurent until Laurent proved himself to be more competent and with a more competent ally, or they already had some hints about what happened that the audience didn't and the evidence confirmed what was inconclusive before.

But I feel like in a series that spends so much time detailing the shifting alliances between the characters and the public's opinion on everyone that matters? I really needed to be sold on it a bit more. Like I really needed some discussion over what to do with the Regent, I needed them to keep him in a cell for a while as they decided whether to kill him (and have the leads scared that the Regent will turn them over as Laurent often does to people), I needed them to consider the evidence just a little bit more, I needed some post mortem with the council members where they explain what was happening on their side of the things. It needed to be MUCH longer and more detailed.

Another thing I wondered at was why the Regent was so insistent to paint Laurent's collaborations with the Akielons as a bad thing when he was... also collaborating with the Akielons? Like he is foaming at the mouth calling them barbarians and accusing Laurent of sleeping with the prince-killer but it feels more like setup for Damen's big declaration of love than an actual political strategy because my brother in Christ, you are literally in the Akielon royal palace, in the middle of Akielos to which you ran after your nephew started a rebellion, with the Akielon king sitting next to you as your equal. Why do you think that you can convince your people that YOUR Vere-Akielos alliance is somehow more morally pure than Laurent's? This was also the right moment to pull out all the patricide allegations that seemed to be going around for Damen, but IIRC he didn't use that as much as he could if at all.

Since there were some Akielons in the room as well, I was also wondering WTF was Kastor doing as the Regent was shitting on his country and calling them barbarians and making it like allying with them is a grave transgression? Why was HE allowing this humiliation? It felt like a very unpolitical thing to do from a character whose strength was in his political acumen (obviously meaning the Regent, not Kastor) and the plot just let it slide by.

I feel like a lot of this is due to this being the first time that the story had to fit within the constraints of a traditional book? So it needed a decisive traditional climax and perhaps it was getting too long for a traditional format, or the author got a bit tired of it and wanted to wind it up now that she wasn't getting regular feedback as you do with serialized publishing, or she prioritized emotional impact over plot logic.

I don't know. I still think they're great books, and the conclusion was emotionally satisfying in the sense that the psychological and interpersonal threads were wrapped up impeccably, I just wanted more detail on the political side. It's still grabbed me like nothing else did for a long time, I can take a mid ending, half of my favourite series will never have one at all because the author wrote themselves into a corner and then died lol.

#captive prince#this one's a plot and worldbuilding analysis#I just have so many things to say I'm sorry ._.#they really scratched an itch#RIP to everyone who followed me for anything else (so basically everyone)

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 2,000-year-old Roman battlefield discovered in the Swiss Alps! Archaeologists have found a trove of artifacts, including a spectacular Roman dagger. This site marks a historic clash between Roman forces and the Suanetes tribe.

#battlefield#Switzerland#Roman Colonization & Expansion#Roman Empire#Roman Military & Warfare#ancient#history#ancient origins

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Women were included in the ranks of this fully mobilized society. Prokopios, aware, of course, of the legends of the Amazons whose origins he traces to the region of the Sabirs, reports that in the aftermath of "Hunnic" (i.e. Sabir) raids into Byzantine territory, the bodies of women warriors were found among the enemy dead. East Roman or Byzantine sources also knew of women rulers among the nomads. Malalas, among others, mentions the Sabir Queen Boa/Boarez/Boareks who ruled some 100,000 people and could field an army of 20,000. In 576 a Byzantine embassy to the Turks went through the territory of 'Akkayai; "which is the name of the woman who rules the Scythians there, having been appointed at that time by Anagai, chief of the tribe of the Utigurs." The involvement of women in governance (and hence in military affairs) was quite old in the steppe and was remarked on by the Classical Greek accounts of the Iranian Sarmatians. It was also much in evidence in the Cinggisid empire.

These traditions undoubtedly stemmed from the necessities of nomadic life in which the whole of society was mobilized. Ibn al-Faqih, embellishing on tales that probably went back to the Amazons of Herodotos, says of one of the Turkic towns that their "women fight well together with them," adding that the women were very dissolute and even raped the men. Less fanciful evidence is found in the Jiu Tangshu which, s.a. 835, reports that the Uygur Qagan presented the Tang emperor with "seven women archers skillful on horseback.” Anna Komnena tells of a Byzantine soldier who was unhorsed with an iron grapple and captured by one of the women defenders as he charged the circled wagons of the Pecenegs. Women warriors were known among the already Islamized Turkmen tribes of fifteenth century Anatolia and quite possibly among the Ottoman gazfs (cf. the Bacryan-z Rum "sisters of Rum")”.

Golden Peter B., “War and warfare in the pre-cinggissid steppes of Eurasia” in: Di Cosmo Nicola (ed.), War and warfare in Inner Asian History

#history#women in history#warrior women#warriors#Akkayai#6th century#historyedit#historyblr#central asia#scythians#sarmatians

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander

"Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander" by Paul Cartledge offers a detailed yet accessible exploration of the legendary figure's life and legacy. The author's expertise and engaging storytelling provide fresh insights into Alexander the Great's conquests and their historical significance. This book is recommended for scholars and general readers alike.

Alexander the Great's profound impact on Roman culture is undeniable, particularly when considering the fusion of Greco-Oriental influences during the Hellenistic era, which permeated Rome and, subsequently, Western Europe. His conquests paved the way for cultural diffusion and laid the groundwork for religious and imperial ideologies. His ideological legacies include figures like Pompey and Caesar. The territories Alexander the Great once controlled formed the foundation of Rome's eastern dominion, often considered the culturally and economically richer half of the empire.

However, understanding Alexander himself proves challenging due to conflicting ancient sources and continuous reinterpretations throughout history, often reflecting the agendas of interpreters.

In Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander, Paul Cartledge offers a captivating and comprehensive new examination of Alexander the Great. With his trademark storytelling prowess, Cartledge, chair of Cambridge University's Classics Department, guides readers through the life and conquests of Alexander with precise detail and an engaging narrative that balances discussion on Alexander's achievements with acknowledgment of places where we lack historical evidence.

Cartledge challenges prevailing notions about Alexander's motivations, particularly regarding Alexander's aim of spreading Hellenism. Cartledge argues that while Alexander was indeed attached to Hellenism, his driving force was personal glory and conquest. This nuanced perspective adds depth to our understanding of Alexander, presenting him as a complex figure driven by ambition and a thirst for success.

Central to Cartledge's exploration is Alexander's military genius. Through detailed chronicles of Alexander's battles with the Persians, Tyrians, and Babylonians, Cartledge highlights the young leader's strategic brilliance and innovative tactics. He demonstrates how Alexander's love of hunting served as a metaphor for his approach to warfare, as he adapted hunting strategies such as the surprise attack to achieve military success. This analysis sheds light on Alexander's mindset and sheds new light on his military achievements.

The book is enriched by many appendixes, including a glossary and an extensive bibliography, which enhance the reader's understanding and provide valuable resources for further exploration. Cartledge's skillful storytelling brings history to life, making the ancient world feel vivid and immediate. His vivid descriptions and storytelling make for an absorbing read that will appeal to both scholars and general readers alike.

Overall, Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander is a masterful biography that offers fresh insights into the life and legacy of one of history's most iconic figures. With its diligent research, engaging narrative, and nuanced analysis, this book is sure to become a definitive work on Alexander the Great for years to come. Whether the audience is a seasoned scholar or a casual reader with an interest in ancient Greece, this book is a must-read.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Romans versus “Barbarians”: A Military Comparison, Part One

An original essay of Lucas Del Rio

Note: I continue in this essay with the Roman theme that explores the origins of the Middle Ages. This time, I compare and contrast Roman tactics and weaponry with some of those that they deemed barbarians and fought wars against. The word “barbarian” is sometimes used, which is only because that is who they were from the Roman standpoint. Keeping this in context, it is not meant as a judgement from my own standpoint. This essay, which will be in four parts, covers relevant wars in an order chronological with Roman history. Part one examines the transition in the Roman army from the Greek phalanx to the early legions in the wars they fought in Italy with the Etruscans, Latins, Samnites, and the Greek colonies. Next week, part two shall deal with the Roman wars with the Carthaginians, Macedonians, Iberians, and Seleucids. After that, part three will cover their wars against the Armenians, Gauls, Britons, and Parthians. Finally, the wars discussed in part four will be those opposing the Germans, Dacians, Sarmatians, and Vandals.

Few empires can rival that of the Romans, but this is not to say that they had no worthy adversaries. It took centuries of wars of aggression against many different cultures for them to create such a massive and powerful realm. Later, their clout would diminish after centuries of defensive wars. The Romans, therefore, were strong enough to conquer what would then become their vast territories, plus continue to hold on to them for an impressive amount of time. Meanwhile, their opponents held off Roman expansion, and while many of them were ultimately subjugated, there were also cultures that were never defeated by the might of Rome. Many years in the future, foreign invaders proved that Romans were not the only successful conquerors around. Like the Greeks, the Romans considered other societies to be uncivilized and referred to them as “barbarians.” Romans had their own specialized ways of fighting that they refined over the centuries, hence their many military successes. Each culture that they battled also fought in manners that they had invented in earlier wars before fighting the Romans. Every war, consequently, was not just between the Roman and “barbarian” armies themselves but also their methods of combat.

As the city of Rome is located in what is now Italy, the first Romans naturally fought their first wars and made their first conquests on the Italian peninsula. Prior to being united by the Romans, Italy was made up of many independent city-states with as many as ten different cultures. In central Italy, where Rome is located, this culture was the Etruscans. The Etruscans are believed to have existed in Italy for a very long time before Rome was even founded. DNA evidence shows that the region was first settled around 6000 BC, when Europe was still in the Stone Age. While the Etruscans were not the first Italians, their ancestors may have migrated from the Steppes. These ancestors, known as the Villanovan culture, were forming by 1100 BC as the Iron Age was beginning. Initially living only in small villages scattered across central Italy, they began to build large cities as they organized into Etruscan society over the course of several centuries. Such cities prospered as they formed trade routes across the Mediterranean Sea with the Carthaginians, Greeks, and others.

There were several stories in antiquity as to how the city of Rome was founded, although the Romans maintained that the year was 753 BC. According to the Romans, their society began as a kingdom, with a series of four kings reigning from 753 to 616 BC. Under the last of these kings, Ancus Marcius, Rome began its military expansion. Following his death, however, the Tarquin dynasty, which was ethnically Etruscan, took over leadership of the city. Various characteristics of Roman civilization did in fact originate with the Etruscans. Perhaps most importantly, the Romans adopted many aspects of Etruscan architecture. Also significant was the Etruscan alphabet, which the Etruscans had adopted from the Greeks and the Greeks from the Phoenicians. Roman religion, often assumed to have only had Greek influence, had roots with the Etruscans as well. Comparatively trivial yet still culturally iconic, it was the Etruscans who wore the first togas. Three different Etruscan kings would rule Rome, but despite the impact that they would have on the Romans, it was the Etruscans who would be their first major adversary.

When the Etruscans ruled the city of Rome, different Etruscan kings controlled at least twenty others. Alliances between these city-states were constantly shifting, as they periodically warred with one another. It might seem peculiar today, but Etruscan warriors were largely aristocrats who personally bought the items such as armor, shields, and weapons that they would need in order to fight. However, peasants were still levied for purposes other than combat. Kings of the city-states also would employ mercenaries that came from places such as Carthage and Greece. In addition to having these Greek mercenaries in their armies, the primary military formation used by Etruscan armies was the Greek phalanx. Possibly originating among the ancient Middle Eastern culture known as the Sumerians and also spreading to the Egyptians, the phalanx became a staple of warfare in Greece and neighboring Macedon. Even more so than Etruria, Greece was composed of a myriad of city-states that sporadically fought wars. The Greek phalanx was eight rows of warrior infantry known as hoplites, who were armored and carried a pike, a round shield, and a sword. A wall of pikes and shields was difficult for enemies to attack without taking heavy losses, and once the battle had become a conventional melee fight, the hoplites used their swords.

Armies in Etruria evolved as the centuries passed. The Etruscans had always preferred to fight as infantry, but the chariots they had sometimes previously employed were replaced by cavalry. Like the Romans, chariots had become strictly for ceremonial purposes. More significant was the change in the prevalence of hoplite phalanxes. After having been customary on Etruscan battlefields since as far back as the 700s BC, the 400s BC saw the formation decline in the region. For a time, the Etruscans tried to counter phalanxes, which did have the genuine problem of inflexibility, by sending waves of warriors brandishing axes into the weaker ends of the formation. While the Etruscans and their styles of fighting changed, there were also major changes occurring in one of their cities. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was the final Etruscan king to rule the city of Rome, and supposedly he was also the most domineering over its citizens. According to Roman folklore, this king was ousted by his oppressed subjects. Historians today have generally concluded, however, that Tarquinius Superbus was deposed by invaders who then lost control of Rome.

Whatever the reason for the change, the Kingdom of Rome was transformed by the Roman Republic in 509 BC. The government began as an aristocracy despite its Republican name, for government positions were reserved for nobles called patricians. After 494 BC, a revolt of the commoners, known in Roman society as plebeians, established a system of voting rights for all free men. They may have achieved a degree of freedom, theoretically at least, although now the city wished to fight in order to expand their own domain. Part of the reason for this was because Rome, many years before becoming a major power, needed a buffer zone against Gallic and other raiders. During the wars that Rome fought against the Etruscans, the Roman army was still in its infancy. Like their Etruscan rivals, the Romans relied much more on infantry than on cavalry. Furthermore, these infantry largely fought as phalanxes, and soldiers in Roman phalanxes carried a spear known as the hasta. As Rome fought the Etruscans, they proved victorious, razing Veii, an Etruscan powerhouse, in 396 BC. It would still be many years before Rome took full control of Etruria, but the fortunes of the Etruscans would gradually decline as the Romans assumed more and more power.

Despite being the first, the Etruscans were only one of several cultures in Italy that the Romans had to vanquish in order to unite the peninsula. The weakening of Etruscan civilization resulted in a deteriorating economic situation for neighboring Latium as well, in fact, as for Rome. Power in central Italy fell into confusion for several decades, but the Romans eventually proved resurgent. Rome began to fight and conquer surrounding tribes, so the Latin League, in an attempt to eliminate the threat that the city posed, declared war in 340 BC. Like the Etruscans, the Latins could not withstand the strength of their Roman foes. By 338 BC, Rome was victorious. In less than a century after the establishment of the Roman Republic, the Romans had become quite the force to be reckoned with. Further south in Italy, a series of three wars with the Samnites also ended in 290 BC with a triumphant Rome.

During these wars, the Roman army continued to innovate. While the exact dates of the military reorganization are unclear, historians believe that the Romans abandoned the phalanx sometime in the 300s BC in favor of one of the mightiest military formations of the ancient world. This formation was the legion. Some scholars in classical antiquity claimed that the Roman army was always organized into legions since the days of the kings, but this notion is not supported by historical evidence. If Livy, one of the most renowned historians from Ancient Rome, is to be believed, then the Roman Republic began using legions in 362 BC. Much more complex than a phalanx, the legion was a highly sophisticated arrangement of different forms of both infantry and cavalry. Soldiers that fought in legions were known as legionnaires. Part of the organization in early legions had to do with experience, as the youngest legionnaires fought at the front of the legion. In early legions, soldiers were armed only with a shield and a spear, plus two of a type of javelin called a pilum.

Roman culture is widely known to have been greatly influenced by its Greek counterpart, but this did not mean that the Romans regarded the Greeks as friends. Long before the Romans invaded Greece itself, they were already having to fight the Greeks. For centuries, the city-states of Greece had been establishing colonies across the Mediterranean, including in Italy. One such colony, which historians believe to have been Spartan, was Tarentum. There are conflicting accounts from antiquity as to exactly how Rome and Tarentum went to war, but it appears, at least according to Roman historians, to have originated in a dispute over Roman trade vessels seized by the Tarentines. Knowing the strength of their foe, the Tarentines found support in other Greeks who had settled in Italy as well as Pyrrhus, the king of the Greek region of Epirus. Pyrrhus, who was related to Alexander the Great, amassed an army full of veteran mercenaries and in 280 BC faced off against the Romans at the Battle of Heraclea. In this battle, the Roman army was able to take advantage of flexibility of the still relatively new legion, which was now starting to prove its superiority over phalanxes. The older formation seemed slow and cumbersome, not to mention vulnerable to flank attacks, compared to the deadly mobility of legions.

Another strength possessed by the Roman army at the Battle of Heraclea was sheer size. The Greek forces led by Pyrrhus numbered twenty-six thousand compared to forty thousand soldiers of Rome. Despite the advantages that the Romans had in both numbers and military sophistication, it was the Greek general who managed to achieve a victory. He managed to bring twenty war elephants to Italy for the purpose of battling the Romans, who panicked at the sight of animals that they had never fought. However, the number of soldiers and their officers that Pyrrhus lost in the battle, possibly fifteen percent of his army, was devastating. Furthermore, his ability to replenish his forces was miniscule compared to that of the Romans, whose republic by this point controlled most of the Italian peninsula. Pyrrhus foolishly expected a Roman surrender, but he did not receive one. In the battles that followed, the Romans refined techniques of using fire to frighten his elephants. By 275 BC, the Roman Republic had won the war, and Pyrrhus managed to flee Italy. Rome may have now united the peninsula that was their homeland, although their ambition had by now grown to want to expand much further.

#ancient#ancient rome#antiquity#battles#bc#civilization#classical antiquity#classical era#conflict#essay#history#italy#military history#roman republic#rome#society#tactics#war#warfare#warriors

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.” —Ephesians 6:12 (NIV)

“Winning the Battle Inside of You” by Rick Warren:

“You may not realize it, but you’re in a battle. You may not wear a military uniform, and you may not dodge physical bullets.

But you’re in a battle—an invisible one. It’s called spiritual warfare. You’ll be in the battle from the moment you’re born until the moment you die.

The Bible tells us that you have three mortal enemies out to destroy your life and everything God wants to do through it:

The world: the dominant value system around us

The flesh: the old nature within you

The Devil: a real being that’s out to “steal and kill and destroy” (John 10:10 NIV) along with his demonic minions

The victory for the battle you’re in won’t come through bullets or tactics. The Bible teaches us that, “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12 NIV).

In this battle, all that matters is Jesus. He has to be the general of your life, the one in charge of the battle plan. You may be a believer, but that’s not enough for this war within you. Jesus has to be your Lord, too.

Many people believe in Jesus. But to find victory over the world, the flesh, and the Devil, Jesus has to be more than just someone you believe in.

Romans 7:24-25 says, “What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!” (NIV)

The answer to the all-consuming battle you’re in isn’t a self-help seminar, a new book, or a conference. It’s Jesus. Make him your boss. Paul, who wrote the book of Romans, makes it clear he can’t win the battle on his own. His only hope is “Jesus Christ our Lord.”

And that’s your only hope, too. Jesus, the Lord, who will deliver you.”

#ephesians 6:12#god loves you#bible verses#bible truths#bible scriptures#bible quotes#bible study#studying the bible#the word of god#christian devotionals#daily devotions#bible#christian blog#god#belief in god#faith in god#jesus#belief in jesus#faith in jesus#christian prayer#christian life#christian living#christian faith#christian inspiration#christian encouragement#christian motivation#christianity#christian quotes#rick warren#keep the faith

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Types of 'Gods'

The concept of gods varies across different cultures, mythologies, and belief systems.

Here are some broad categories or types of gods that can be found in various religious and mythological traditions:

Creator Gods: Creator gods are often associated with the creation of the world or universe. They are believed to have brought existence into being and may hold significant power and authority. Examples include Brahma in Hinduism, Atum in Egyptian mythology, and Elohim in certain interpretations of the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Mother Goddesses: Mother goddesses represent fertility, nurturing, and the life-giving aspects of the divine feminine. They are associated with creation, birth, and the cycles of nature. Examples include Isis in Egyptian mythology, Demeter in Greek mythology, and Gaia in ancient Greek cosmogony.

Sky Gods: Sky gods are associated with the heavens, celestial bodies, and the realm of the sky. They often possess powers related to weather, lightning, or cosmic order. Examples include Zeus in Greek mythology, Thor in Norse mythology, and Indra in Hinduism.

War Gods: War gods are associated with warfare, battles, and military prowess. They often embody strength, courage, and strategic abilities. Examples include Ares in Greek mythology, Mars in Roman mythology, and Huitzilopochtli in Aztec mythology.

Wisdom Gods: Wisdom gods are associated with intellect, knowledge, and spiritual insight. They are often revered as divine teachers or possessors of divine wisdom. Examples include Athena in Greek mythology, Thoth in Egyptian mythology, and Saraswati in Hinduism.

Trickster Gods: Trickster gods are mischievous and often unpredictable figures who challenge conventions and bring about change or disruption. They may embody chaos, humor, or transformation. Examples include Loki in Norse mythology, Hermes in Greek mythology, and Anansi in West African folklore.

Love and Beauty Gods: Love and beauty gods embody qualities of love, romance, beauty, and desire. They are often associated with fertility, attraction, and the pursuit of aesthetic pleasure. Examples include Aphrodite in Greek mythology, Venus in Roman mythology, and Freyja in Norse mythology.

These categories are not exhaustive, and there are countless other types of gods and divine beings found in different belief systems. The characteristics and roles of gods can vary greatly, reflecting the unique cultural and religious contexts in which they are worshipped.

{This post is just for educational reasons}

#types of gods#gods#witchblr#witchcore#witchcraft#witchlife#white witch#beginner witch#witch tips#grimoire#spirituality#book of shadows

127 notes

·

View notes