#Romish

Text

#Romish#WPGMaps#MP3Juice#FreeMusic#MusicDownloads#MP3Download#MusicSite#OnlineMusic#MusicLovers#UserProfile

0 notes

Text

Fantasy notes design set based on ancient Roma features.

#ancient Roma#Roma#rzymskie#romish#design#concept#projekt#not circulated#nieobiegowy#fantazyjny#fancy#note#fantasy#banknote#banknot

0 notes

Text

The truth is, I had not so much principle of any kind as to be nice in point of religion, and I presently learned to speak favourably of the Romish Church; particularly, I told them I saw little but the prejudice of education in all the difference that were among Christians about religion, and if it had so happened that my father had been a Roman Catholic, I doubted not but I should have been as well pleased with their religion as my own.

Moll Flanders, the most religiously pragmatic tolerant woman of old timey literature!

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

sampled that guy's book (Disch's) and he's very much a "TV HAS ROTTED AMERICANS' MINDS AND WILL MAKE THEM INTO FASCISTS" type midwit boomer with very little to to say

so it's kind of funny how fanatically he keeps on jumping down to suck Gene Wolfe's dick just for writing an Guy With Sword book with good prose & unclear coherency

also apparently in the early 80s Wolfe's romishness wasn't known. so Disch thinks he's an Anglican.

Disch was published in New Worlds and very consciously belongs to the same group as Moorcock and Ballard (and I guess Brian Aldiss, who retained a very fannish appreciation for older sf) - who were quite polemically seeking to drive a wedge between New Wave sf and the stuff that came before it. I think Disch is more charitable than Moorcock was in 'Starship Stormtroopers' but the motivation is similar.

I would agree with his assessment (in the first chapter, which is all that I read, so we are both throwing half the facts at each other here) that the majority of sf is compensatory power fantasies written by and for lower and lower middle class machinists and technicians, and with his modifying statement that the resentments and power fantasies of the lower classes are not in themselves bad things, and his further modifying statement that when these resentments and desires remain unconscious they can be exploited by unscrupulous actors.

I would disagree with his decision to then seek new forms within sf entirely, or to seek to 'mature' the genre by hoping to attain credibility in the eyes of the Academy and become 'real literature'. Given I'm not an sf writer of the 70s, I have no motivation to create a break from what came before, and I don't think such a break is tenable in the US (in the UK, maybe) - most of the Golden Age authors became editors, publishers, teachers, encouragement to the subsequent US New Wave. There was a direct continuity in the field.

His extremely pessimistic and elitist take that Americans have become beholden to new cultural tech (as though each text has a definite, singular reading which not only can be found by readers but will necessarily be unconsciously absorbed by them with no breaks or slips or contestations) is unfortunately the source of much of what I enjoy about his fiction (particularly 334) - that detailed study of sociological changes '5 minutes into the future' using all the best techniques of 19th-century french realism and an inductive spooling out of the possibilities of current tech. I can't dismiss it off-hand.

It is also very funny to me when people who would cry horror at Robert Howard or Fritz Lieber or Jack Vance or whoever love Gene Wolfe because he makes Joyce references and so 'redeems' what is otherwise a fantastical sword-and-sorcery tale. Disch was raised Catholic and became an atheist so it's a shock he wasn't hyper-aware of Wolfe's Catholicism. He's not hiding it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elect of the Nine | Elu of the Nine

Morals and Dogma - Chapter IX

Part I

It wars against the passions that spring out of the bosom of a world of fine sentiments, a world of admirable sayings and foul practices, of good maxims and bad deeds; whose darker passions are not only restrained by custom and ceremony, but hidden even from itself by a veil of beautiful sentiments. This terrible solecism has existed in all ages. Romish sentimentalism has often covered infidelity and vice; Protestant straightness often lauds spirituality and faith, and neglects homely truth, candor, and generosity; and ultra-liberal Rationalistic refinement sometimes soars to heaven in its dreams, and wallows in the mire of earth in its deeds.

#freemasonry#freemasons#Albert Pike#masonic lodge#illustration#masons#masonic temple#Masonic Education#symbolism#esoteric#art#morals and dogma#occult#hermetic#sacred geometry#sacred texts

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babylon, The Seat of Satan, and Rome

Revelation 2:12-13 KJV

12 And to the angel of the church in Pergamos write; These things saith he which hath the sharp sword with two edges; 13 I know thy works, and where thou dwellest, even where Satan's seat is: and thou holdest fast my name, and hast not denied my faith, even in those days wherein Antipas was my faithful martyr, who was slain among you, where Satan dwelleth.

Babel, or Babylon, was built by Nimrod. Gen. 10:8-10. It was the seat of the first great Apostasy. Here the "Babylonian Cult" was invented. A system claiming to possess the highest wisdom and to reveal the divinest secrets. Before a member could be initiated he had to "confess" to the Priest. The Priest then had him in his power. This is the secret of the power of the Priests of the Roman Catholic Church today.

Once admitted into this order men were no longer Babylonians, Assyrians, or Egyptians, but members of a Mystical Brotherhood, over whom was placed a Pontiff or "High Priest," whose word was law. The city of Babylon continued to be the seat of Satan until the fall of the Babylonian and Medo-Persian Empires, when he shifted his Capital to Pergamos in Asia Minor, where it was in John's day. Rev. 2:12,13.

When Attains, the Pontiff and King of Pergamos, died in B. C. 133, he bequeathed the Headship of the "Babylonian Priesthood" to Rome. When the Etruscans came to Italy from Lydia (the region of Pergamos), they brought with them the Babylonian religion and rites. They set up a Pontiff who was head of the Priesthood. Later the Romans accepted this Pontiff as their civil ruler. Julius Caesar was made Pontiff of the Etruscan Order in B. C. 74. In B. C. 63 he was made "Supreme Pontiff" of the "Babylonian Order," thus becoming heir to the rights and titles of Attalus, Pontiff of Pergamos, who had made Rome his heir by will. Thus the first Roman Emperor became the Head of the "Babylonian Priesthood," and Rome the successor of Babylon. The Emperors of Rome continued to exercise the office of "Supreme Pontiff" until A. D. 376, when the Emperor Gratian, for Christian reasons, refused it. The Bishop of the Church at Rome, Damasus, was elected to the position. He had been Bishop 12 years, having been made Bishop in A. D. 366, through the influence of the monks of Mt. Carmel, a college of Babylonian religion originally founded by the priests of Jezebel. So in A. D. 378 the Head of the "Babylonian Order" became the Ruler of the "Roman Church." Thus Satan united Rome and Babylon In One Religious System.

Soon after Damasus was made "supreme Pontiff" the "rites" of Babylon began to come to the front. The worship of the Virgin Mary was set up in A. D. 381.

The Book Of Revelation Commentary by Clarence Larkin (1919 pgs. 151-152)

Larkin goes on to say on page 152...

All the outstanding festivals of the Roman Catholic Church are of Babylonian origin. Easter is not a Christian name. It means "Ishtar," one of the titles of the Baby- Ionian Queen of Heaven, whose worship by the Children of Israel was such an abomination in the sight of God. The decree for the observance of Easter and Lent was given in A. D. 519. The "Rosary" is of Pagan origin. There is no warrant in the Word of God for the use of the "Sign of the Cross." It had its origin in the mystic "Tau" of the Chaldeans and Egyptians. It came from the letter "T," the initial name of "Tammuz," and was used in the "Babylonian Mysteries" for the sarnie magic purposes as the Romish church now employs it. Celibacy, the Tonsure, and the Order of Monks and Nuns, have no warrant or authority from Scripture. The Nuns are nothing more than an imitation of the "Vestal Virgins" of Pagan Rome.

...and there is a lot more said but I want to go back to Damasus real quick. Not only was he the Pope from 366-384, and did all the above mentioned. He is also was the first to declare that Rome was started by Peter, thereby claiming Peter as the “founder” of the church (which is a complete lie and twist of scripture), and was the one that commissioned Jerome to “revise” the Latin translation of the Bible which became known as the Vulgate. To this day, NO ONE has seen the text that one man (Jerome) used to create the Vulgate.

Revelation 18:4-5

4 And I heard another voice from heaven, saying, Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues.

5 For her sins have reached unto heaven, and God hath remembered her iniquities.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

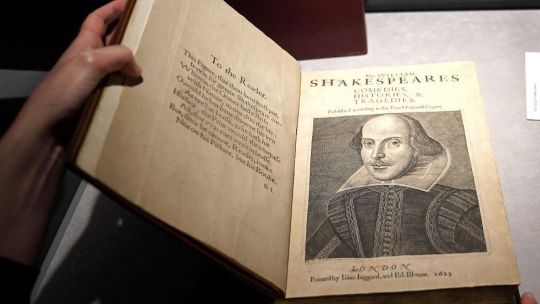

Anonymous asked: Going through your archive I loved your fantastic long posts on Shakespeare. As you know there is some debate on whether Shakespeare was either a Catholic or Protestant. Where do you stand on this issue?

The issue of Shakespeare’s religion, as you have pointed out, has been an issue that has long vexed both scholars and the educated layman. To be honest it is of little interest to me (beyond a playful parlour game) because it has never stopped me appreciating the greatness of his works.

Of course it would have mattered to Shakespeare. For in his lifetime, atheism was equated with immorality, and Catholicism in England was equated with treason. Queen Elizabeth I had executed Edward Arden, a relative of Shakespeare’s mother, for his supposed Catholic treachery. Religion was a matter of life or death; and Shakespeare, like everyone else, walked a precarious denominational line.

But if pushed I would say he was Protestant but with a Catholic imagination. I suppose this is what fence sitting looks like. But hear me out.

It’s possible to answer this seemingly simple question in lots of different ways. Like other English subjects who lived through the ongoing Reformation, Shakespeare was legally obliged to attend Church of England services. Officially, at least, he was a Protestant. But a number of scholars have argued that there is evidence that Shakespeare had connections through his family and school teachers with Roman Catholicism, a religion which, through the banning of its priests, had effectively become illegal in England. Even so, ancestral and even contemporary links with the faith that had been the country’s official religion as recently as 1558, would make Shakespeare typical of his time. And in any case, to search for a defining religious label is to miss some of what is most interesting about religion in early modern England, and more importantly, what is most interesting about Shakespeare.

Questions such as ‘was Shakespeare a Protestant or a Catholic?’ use terms that are too neat for the reality of post-Reformation England. The simple labels Catholic, Protestant, and Puritan paper over a complex way faith works in our lives. Even in less turbulent times, religion is a framework for belief; actual faith slips in and out of official doctrine. Religion establishes a set of principles about belief and practice, but individuals pick and choose which bits they listen to. I think that’s fair as someone who is a believing Anglican Christian I slip and fall in my faith all the time, but all one can do is ask for sincere forgiveness, get up, dust yourself off, and get on with your life. Until the next prat fall.

My point is that ‘Catholicism’ was an especially tricky category in this era to be definitive about. Under pressure of crippling fines and even execution, early modern Catholics maintained their faith in a variety of ways. Not every so-called papist supported the pope. The Roman Catholic Church of this era encompassed ‘recusants’ (who openly displayed their Catholicism by refusing to attend mandatory Church of England services) and ‘church papists’ (who conformed to the monarch’s protestant customs, but secretly practiced Catholicism). Some Catholics supported Elizabeth politically, looking to the pope only in spiritual matters; others plotted her overthrow.

Catholicism was in the eye of the beholder; other Protestants saw many elements of Elizabeth’s own Church as horrifyingly ‘Romish’, but to average Protestants those puritanical objections seemed hysterical. Some accepted the theology and politics of the reformation, but still harboured an emotional attachment to older traditions, like praying for the dead.

Furthermore, people have a habit of changing their minds over time, shifting their beliefs at different moments of their lives. Asking about the confessional allegiance of any early modern individual is a much more difficult – and interesting – enterprise than figuring out an either/or choice. Whatever Shakespeare’s personal faith was, he wrote plays that worked for audiences who had to feel their way through these dilemmas, audiences for whom Protestantism was the official state religion, but who experienced a far messier reality.

Playhouses provided spaces to explore these anxieties. Even though the direct representation of specific theological controversy was banned, Renaissance plays frequently featured elements of the Roman Catholic religion that had been practically outlawed in real life. Purgatorial ghosts and well-meaning friars still appeared on stage; star-crossed lovers framed their first kiss in terms of saintly intercession and statue veneration (Romeo and Juliet, 1.4.206-19); and various characters swore ‘by the mass’, ‘by the rood’, and ‘by’r lady’.

Shakespeare wrote over sixty years after Henry VIII set the Reformation in motion. By the 1590s, English friars, nuns and hermits belonged firmly to the past, and many writers used them like the formula ‘once upon a time’: to create a safely distant, fictional world. Even so, Catholic Europe and Jesuit missionaries were perceived by state authorities as a very present danger. Anti-Catholic propaganda demonised that faith as fundamentally deceitful; ‘papist’ piety was mere pretence, a cover for lechery, treachery, and sin.

Accordingly, some writers used Catholic settings as a shorthand for corruption (think of the decadent world of Webster’s Duchess of Malfi, with its murderous and lascivious Cardinal). So Catholicism could point in different fictional directions: it could benignly and nostalgically suggest an unreal past, in the manner of a fairytale; or, it could paint a threatening image of a more contemporary fraud.

But it’s striking that Shakespeare uses Catholic content rather differently from his contemporary dramatists, often embracing the contradictory connotations of, say, a friar, exploiting the figure’s nostalgic and threatening associations at the same time. This exploration of ambiguity seems to have been one way in which he thought through not only religious controversies, but also the very act of making fiction itself. A figure who works both like a fairytale and like a fraud tests out what is good and what is dangerous about literary illusion.

All’s Well that Ends Well is a case in point. This comedy tests fantasy ideals against real-life problems. Helen, the clever wench who miraculously cures a king and wins a husband of her own choosing, finds herself in love with a prince who isn’t so charming. But critics have never been too sure about whether Helen herself is a virtuous victim of her snobbish husband, or if she’s simply conniving and self-centred. By putting all of these possibilities in play Shakespeare invites us to interrogate the ideals that underpin romantic comedy: are the conventions we think of as happy endings really all that happy?

One way that Helen secures her own happy ending is by putting on a pilgrim’s habit which allows her to follow (and eventually catch) her runaway husband. But this costume, with its mixed Catholic associations, further complicates the character and the morality of the plot. While the Catholic Church regarded pilgrimage to holy places as “meritorious” (a way of piously working to the salvation that only Christ could enable), Reformers scoffed at the notion that one earthly place could be holier than another, dismissed as idolatrous the intercession of saints usually invoked at shrines, and abhorred the idea that Christ’s gift of salvation needed supplementing. Shakespeare hints both that Helen might be the hypocrite of anti-Catholic polemic, who uses a pious habit to conceal selfish intentions, and that she might be a prayerful woman, who would be justly rewarded with a happy ending.

Furthermore, the comedy also draws on more secular associations of ‘pilgrimage’, which run through the love poetry of the period figuring amorous devotion. We first learn of Helen’s pilgrimage in a letter that takes the form of the sonnet; at this point Helen is painted as something of a Petrarchan stalker, trekking her errant husband in the clothing of well-worn poetic metaphor. But Shakespeare unpicks other threads of meaning in the pilgrim costume too. In anti-Catholic fabliaux pilgrims used their religious journeys for decidedly smutty adventures. It’s probably no mistake that Helen uses her pilgrimage so that she can finally have sex. And again, there’s a question mark hanging over this behaviour. On the one hand her active desire for physical intimacy with her husband is legitimate and liberating, but on the other, she repeatedly removes her husband’s power of consent, most disturbingly in a bed-trick (a ‘wicked meaning in a lawful deed’). The comedy questions her sexual scruples.

Shakespeare exploits the various associations of the pilgrim in post-Reformation England. In Helen, papist and Catholic connotations are compounded: she is meritorious and devious, miraculous and cunning. The ‘happy ending’ of this play sees husband and wife reunited and apparently reconciled. But the ‘real’ wonder of this moment is provisional: ‘All yet seems well’ (my emphasis). The audience is very aware of the pragmatic tricks that Helen had to perform in order win this resolution. By drawing on the contradictory meanings of the pilgrim, Shakespeare creates a paradoxical character that engages his audience with the ethical dilemmas of fiction: when might the means justify the ends?

In this play, as in others, Shakespeare calls on the ambiguous associations of Catholic figures, images and ideas, as a means of engaging his audience with the problems he frames. He seems to revel in the pleasures of slippery meaning. By flirting with stereotypes and sectarian expectations he makes his audience think more deeply about the difficulties of the plays and their own culture. Whatever Shakespeare’s personal religion was, the religion he put on stage was both playful and probing.

But it is an interesting question to speculate what William Shakespeare’s religious beliefs were. I’ve had several fascinating discussions with friends and even work colleagues (between them they have a few English lit PhDs under their belt) to get a better understanding of this question.

When Shakespeare died in 1616 at age 52, he was buried in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, which would have been an impossibility for a known atheist. Yet questions about his religion arose early, some 70 years after his death, when Richard Davies, an Anglican clergyman, wrote from local legend that the poet had “dyed a Papyst.”

The controversy continued. In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson considered Shakespeare a brilliant but irreverent poet. Consider the Bard’s lines: “Why, all the souls that were, were forfeit once/ And He that might the vantage best have took/ Found out the remedy.” So speaks the Franciscan novice Isabella to the cruel judge Angelo in Shakespeare’s black comedy ‘Measure for Measure’ (1604). Is the poetry here biblical or merely “universal” in its meaning?

A century later Samuel Taylor Coleridge found the Bard’s comedic forgiveness of the judge Angelo to be morally abhorrent. While literary critics believed Shakespeare too “fanciful” and “rustic” to be orthodox, many popular authors noted Shakespeare’s encyclopaedic use of the Bible.

One my Irish work colleagues who has an English Lit PhD pointed to other commentators who entered the fray. For example in 1899, the Rev. H. S. Bowden collected the evidence in The Religion of Shakespeare, using the work of Richard Simpson to compile his pro-Catholic compendium.

She also told me that it was not until G. Wilson Knight successfully argued in The Wheel of Fire (1930) for a Christian and biblical Shakespeare that this view was accepted by what might be called the ‘Shakespeare establishment.’ For the first time in over 200 years, the problem of how the poet of “fancy” could also be a serious, Bible-loving Christian was considered solved. Yet this Shakespeare was the Protestant Shakespeare of the British Empire, not the Catholic poet of Father Bowden.

The “Catholic Shakespeare” thesis entered mainstream English criticism with E. A. J. Honigmann’s book, Shakespeare: The Lost Years (1985). It demonstrated how a butcher’s son from Warwickshire triumphed in London through connections with an aristocratic Catholic family in Lancashire, without implying that the Bard had a continuing allegiance to Rome.

The full development of the Catholic thesis, however, came in the seminal work of Peter Milward S.J. - Shakespeare’s Religious Background (1973), with further work by Ian Wilson in 1993 with this publication of his book, Shakespeare: The Evidence, which meticulously researched Shakespeare’s literary and political ties to Catholic patrons and politics.

All fine and dandy but these books never settled the question once and for all.

The main problem with claiming that Shakespeare was a Catholic recusant is the historical record: He lived and died a member of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. Other close ties to the Reformed Church include his lodging with Huguenots when in London, and the marriage of his daughter Susanna to a Protestant doctor, John Hall, after she was fined for being a Catholic recusant. That record need not contradict what appears to be sympathy for Catholicism, clearly evident in his plays; but Shakespeare also tried to present an objective approach to Rome. For example, Franciscans are depicted for their honest vocations, although cardinals are notoriously portrayed as murderous cowards.

One possible explanation for this apparent inconsistency may lie in the fact that the English Reformation was still in progress during Shakespeare’s lifetime. England remained Catholic in spirit and practice long after 1534, with parts of Lancashire still practicing the “old faith” openly. It is possible that the post-Reformation Holy Trinity Church in Warwickshire was sufficiently traditional to allow a Catholic-sympathiser like Shakespeare to participate. If the Church of England authorities knew of the poet’s Stratford affiliation, then the fact that Shakespeare’s nonattendance at Puritan-leaning London parishes went unpunished could be explained.

Despite this, the Catholic recusancy thesis - that the plays have a pro-Catholic political subtext - has never received broad acceptance amongst scholars. And as for the general public, I don’t think they care. I wouldn’t take the question too seriously either, especially if it gets in the way of enjoying Shakespeare’s works in itself.

I would conclude that the most promising avenue for appreciating Shakespeare’s Catholicity lies not in biography but rather in the recognition of his Catholic imagination, readily discoverable in his plays. Through metaphor, the poet enlarges the sensibilities through an encounter with inspired meaning. Reformed theology had posited an irreparable break between the divine and the human, whereas the Catholic imagination seeks and finds the divine in broken humanity, bridging the gap between nature and grace.

One example should suffice. A reference to the passage “Why, all the souls…” from “Measure for Measure” demonstrates how a ‘Catholic’ imagination functions poetically. The speaker, Isabella, is a devout if initially self-righteous novice with the Poor Clares of Vienna. In her first meeting with the Puritan Angelo, she pleads for the life of her brother, who is under a death sentence for impregnating his girlfriend. Angelo argues that mercy is impossible because her brother “is a forfeit of the law.” In a Pauline argument, Isabella asserts that all were condemned by sin (Rom 3:23) until the Son of God sacrificed his equality with God to achieve salvation for the world (Rom 3:24-26).

But I wouldn’t push it too far. It can be archetypal or thematic or say something of the Christian world view of sin, fallen-ness, and forgiveness, and redemption, but it’s not in your face and it’s not explicitly obvious. At the end of the day Shakespeare was a genius story teller, not a theologian or ideologue, or anything else.

This brings me to my final point. Speaking for myself as a theatre lover in general, the answer we seek must be in the context of why we love drama and Shakespeare’s theatre especially. The theatre seeks to entertain, preparing the heart and mind for reflection, while the purpose of sermons is to preach and instruct. Drama is never a sermon. And this would apply to the portrayal of Shakespeare as a proselytising Protestant, papist renegade or atheist subversive. When ideology reduces a living drama to apologetics, voices of protest will inevitably be raised. This is something we forget today as woke ideology has infected modern entertainment across the board. The Wokists - artists as activists who relentlessly peel back the onion skin until nothing is left - have forgotten the first rule of drama as truth telling: tell a good story, don’t preach.

Thanks for your question.

#ask#question#shakespeare#william shakespeare#plays#literature#playwright#religion#christianity#catholcism#protestantism#morality#imagination#catholic imagination#beliefs#shakespeare's religious beliefs#elizabethan england#anti-woke#woke#theatre#drama#arts#society#culture#english

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Era of the Puritans (1559-1662, or thereabouts)

The English nation, under Henry VIII, having renounced the jurisdiction of Rome: The loss of such an important department of his spiritual kingdom exasperated the Roman pontiff almost to madness; but finding his power and influence unequal to the task of recovering his supremacy, he carefully watched every movement of the English government, in hopes that more auspicious circumstances might enable him to reclaim his scattered flock, and once more gather them together under the maternal wings of the Romish church. During the life of Henry he was not altogether without hope…

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

(To give a little context to this excerpt: Cary became a practicing Catholic as an adult and tried to secretly send two of her sons out of England so they could attend a seminary in Europe.)

On May 16, 1636, Elizabeth was brought before the King's Bench, the highest common law court in the kingdom. Despite being subjected to a harsh interrogation by the chief justice, Sir John Bramston, she remained unshakable. She even perjured herself by claiming she didn't know "what [had] become of her two sons" and had no idea "whether they be in England or out of England beyond the sea." Nine days later, she was summoned to the Star Chamber... There, under examination by a panel of fourteen men... she was accused of "sending over into foreign parts two of her sons, without license to be educated there (as is conceived) in the Romish religion."

Not only did Elizabeth refuse to cooperate with the court, but according to her daughters' detailed account, she brazenly challenged the legal basis of the judges' charge against her. Even if she had sent the boys to France, which in fact she hadn't yet done, she argued it would have been up to the officers at the port to check for their licenses to travel, but not up to her to obtain them. Irate, one of the lawyers asked whether "she meant to teach them law." She responded that they shouldn't fail to "remember what she made no question they knew before, and that she being a lawyer's daughter was not wholly ignorant of." Her hours spent as a child in Lawrence's courtroom--the closest thing to a legal education a woman could have--had paid off.

Ramie Targoff, Shakespeare's Sisters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Van Dyck, Archbishop William Laud, 1636, National Portrait Gallery, London

Even someone with a natural talent for sycophancy like van dyck could not make Laud look anything other than thin skinned and awkward. Despite this, you really should not underestimate this man, as too many did in his own lifetime.

William Laud (1573-1645) pronounced “lord” not “loud” (I learnt this the hard way) is probably the most important Archbishop of Canterbury of the period bar Thomas Cranmer from the previous century. Modern Anglicanism/Episcopalism is as much his vision as it is Cranmer’s.

He’s often associated with a movement called Arminianism which sought to reverse some Calvinist excesses such as the doctrine of predestination and a renewed emphasis on sacraments, liturgy and hierarchy. It, in Laud’s variant anyway, also emphasised royal power and was a theological basis for Charles’s vision of sacredotal kingship.

Laud’s strategy and vision was to return the Church in England back to its pre reformation status and wealth, albeit purged of “Romish” errors and puritan troublemaking. This was music to both Charles and George’s ears who were looking for allies and tools to shut down opposition and increase crown revenue.

Christopher Hill was on to something when he said that what Charles and Laud were doing was using the tools of the Catholic counter reformation to build an ostensibly Protestant autocratic monarchy boosted by a hierarchal authoritarian church; at the expense of the Calvinist aristocratic grandees, landowners, and merchant class who dominated the governance in the three kingdoms and their parliaments.

All this was part of a larger ideological programme of turning back the erosion of crown power and church wealth in both kingdoms, as well as the elimination of resistance theory and popular sovereignty as ideological alternatives to authoritarian monarchy and hirachical religion.

You don’t need to be a church historian or a theologian to see how grossly unrealistic and needlessly provocative this was. It all came to grief in Scotland where Laud and Charles’s hubristic ambitions met reality and their attempts to impose a revised liturgy for Scotland (really a copy and paste of the BCP) led to the Covenanter movement and the Scottish invasion of northern England, supported by treasonous lords like Warwick, Manchester, and Essex in England as a way to force Charles hand into recalling parliament. Soon Charles lost his authority, the country was engulfed in civil war. Laud was impeached, arrested, imprisoned on bogus charges of promoting “popery” and executed in 1645.

Laud was a thin skinned man who was often the subject of much criticism for his “low born” origins. Even Charles would later state that he was too indulgent of Laud’s “peevish humours” and that his obsession with ceremony and order was unnecessary. He often argued with others in council meetings and had a reputation for vindictiveness, as evidenced by the treatment of puritan pamphleteers like Burton, Bastwick, and Prynne, and the reliance on prerogative courts and church courts to enforce uniformity and punish dissent. This was summed up be Burton himself saying he’d been strangled by lawn sleeves and prynnes claim that the brand of SL was not “seditious libeller” but “stigmata laudis.”

Laud was out of place at the female dominated court of Charles I as he was deeply uncomfortable with women, and despite later claims, him and Henrietta could not stand each other. There is an old story that he was offered a Cardinal’s hat by pope Urban VIII but I’ve never seen any evidence for this and Laud also made a point of ostentatiously avoiding the Queen’s papal envoys and priests despite their best efforts to engage him.

He’s often believed to have aspired to in effect be a second Wolsey or an English Richelieu, there’s simply not enough evidence for these claims; besides lacking meaningful interest in foreign policy or military affairs, Laud did not have the self confidence, emotional discipline, or strategic vision for that kind of role, nor the appetite for it.

You would not guess that he had erotic dreams about George from this portrait (Laud was almost certainly gay - his own diary is the source of the dreams as well as sexual encounters with other men) and that he was a proud cat dad in an age of dog people (Richelieu was a cat dad too).

He also left the most withering judgement on Charles, before his execution in 1645, namely that he was “a mild and gracious Prince, that knows not how to be or be made great.” Ouch.

#george villiers#duke of buckingham#charles i#james i#henrietta maria#William laud#boring religious stuff#cat dad#everybody wants steenie#Christopher hill was wrong about a lot but he was right about the above#don’t mess with Presbyterians#red wouldn’t suit Laud either

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

trying to emphasize the Catholic Church as emanating from Rome (in the context of Jesuit missionaries, who were often under the thumb of the Portuguese empire) without sounding like a Prot crank when I say "the Church in Rome" or "the Romish Church"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the Term "Roman Catholic" | Origin, Usage, and Criticisms

Roman Catholic

The term "Roman Catholic" is often used in official documents to describe members of the Catholic Church, as a way of recognizing those who reject the authority of the Church. Some Anglicans view the Catholic Church as consisting of three main branches: Roman, Anglo, and Greek. However, this view has been shown to be incorrect. For more information on the term "Catholic", please refer to the articles on "church" and "Catholic".

Definition

The "Oxford English Dictionary" defines "Roman Catholic" as follows.

“The use of this composite term in place of the simple Roman, Romanist, or Romish; which had acquired an invidious sense, appears to have arisen in the early years of the seventeenth century. For conciliatory reasons it was employed in the negotiations connected with the Spanish Match (1618-1624) and appears in formal documents relating to this printed by Rushworth (I, 85-89). After that date it was generally adopted as a non-controversial term and has long been the recognized legal and official designation, though in ordinary use Catholic alone is very frequently employed. (New Oxford Dict., VIII, 766)”

Illustrative quotations follow. The earliest is from Edwin Sandys' "Europae Speculum" of 1605: "Some Roman Catholics won't say grace when a Protestant is present." Day's "Festivals" of 1615 contrasts "Roman Catholics" with "good, true Catholics.”

Origin of the Term

The Oxford Dictionary's account of the origin of the term "Roman Catholic" is not entirely satisfactory. The term is actually much older than believed, dating back to the 16th century when English Catholics under persecution defended the lawfulness of attending Protestant services. In response, Protestant divines, such as Father Persons and Robert Crowley, used the term "Roman Catholic" or "Romish Catholic" in their writings. They resented the Roman Catholic Church's claim to the term "Catholic" and insisted that the Reformers were the true Catholic Church. The term "Roman Catholic" originated from this Protestant view, and was used to qualify the term "Catholic" when referring to their opponents. Crowley even referred to his opponents as "Protestant Catholics.”

On the other hand the evidence seems to show that the Catholics of the reign of Elizabeth and James I were by no means willing to admit any other designation for themselves than the unqualified name Catholic. Father Southwell's "Humble Supplication to her Majesty" (1591), though criticized by some as over-adulatory in tone, always uses the simple word. What is more surprising, the same may be said of various addresses to the Crown drafted under the inspiration of the "Appellant" clergy, who were suspected by their opponents of subservience to the government and of minimizing in matters of dogma. This feature is very conspicuous, to take a single example, in "the Protestation of allegiance" drawn up by thirteen missioners, 31 Jan., 1603, in which they renounce all thought of "restoring the Catholic religion by the sword", profess their willingness "to persuade all Catholics to do the same" and conclude by declaring themselves ready on the one hand "to spend their blood in the defence of her Majesty" but on the other "rather to lose their lives than infringe the lawful authority of Christ's Catholic Church" (Tierney-Dodd, III, p. cxc). We find similar language used in Ireland in the negotiations carried on by Tyrone in behalf of his Catholic countrymen. Certain apparent exceptions to this uniformity of practice can be readily explained. To begin with we do find that Catholics not unfrequently use the inverted form of the name "Roman Catholic" and speak of the "Catholic Roman faith" or religion. An early example is to be found in a little controversial tract of 1575 called "a Notable Discourse" where we read for example that the heretics of old "preached that the Pope was Antichriste, shewing themselves verye eloquent in detracting and rayling against the Catholique Romane Church" (p. 64). But this was simply a translation of the phraseology common both in Latin and in the Romance languages "Ecclesia Catholica Romana," or in French "l'Église catholique romaine". It was felt that this inverted form contained no hint of the Protestant contention that the old religion was a spurious variety of true Catholicism or at best the Roman species of a wider genus. Again, when we find Father Persons (e.g. in his "Three Conversions," III, 408) using the term "Roman Catholic", the context shows that he is only adopting the name for the moment as conveniently embodying the contention of his adversaries.

Usage

In a passage from an examination in 1591 (see Cal. State Papers, Dom. Eliz., add., vol. XXXII, p. 322), a deponent was "persuaded to conform to the Roman Catholic faith." However, it's unclear if these are the exact words of the person in question or if they were said to please the examiners. The "Oxford Dictionary" suggests that "Roman Catholic" became the official label for English Papacy supporters during negotiations for the Spanish Match from 1618-24. The religion of the Spanish princess was often referred to as "Roman Catholic" in the various treaties and proposals for this match. Before this period, Catholics were commonly referred to as Papists or Recusants, and their religion was described as popish, Romanish, or Romanist in Acts of Parliament and proclamations. Even after "Roman Catholic" became the official term, it was still used condescendingly. Catholics began to use the term themselves to encourage a friendlier relationship with the authorities, as seen in the "Humble Remonstrance, Acknowledgement, Protestation and Petition of the Roman Catholic Clergy of Ireland" in 1661. The same practice was observed in Maryland. The wish to appease hostile opinions grew greater as Catholic Emancipation became a practical political issue, and by then, Catholics used the qualified term even in their domestic discussions. In 1794, the "Roman Catholic Meeting" was formed to counteract the unorthodox tendencies of the Cisalpine Club, with the approval of the vicars Apostolic. The Irish bishops referred to members of their own communion as "Roman Catholics" during a meeting in 1821. Even Charles Butler, a representative Catholic, used the term "roman-catholic" in his "Historical Memoirs.”

In the mid-19th century, a strong revival of Catholicism led many converts to insist that the name "Catholic" be used without qualification. However, the government refused to allow any changes to the official designation, and even on public occasions, addresses presented to the Sovereign had to use the term "Roman Catholic Archbishop and Bishops in England". Despite attempts to use alternative phrasing, such as "the Cardinal Archbishop and Bishops of the Catholic and Roman Church in England", these were not approved. In 1901, the requirements of the Home Secretary were complied with when the Catholic episcopate presented addresses using the term "Roman Catholics". Cardinal Vaughan explained that this term had two meanings: one that was repudiated and another that was accepted. The term "Roman" is not meant to restrict the Church to a particular species or section, but rather to emphasize its unity and its connection to the Roman See of St. Peter.

Criticisms

Representative Anglican Bishop Andrewes ridiculed the phrase "Ecclesia Catholica Romana" as a contradiction in terms. Catholics make no compromise in the matter of their name as it is the traditional name handed down to them from the time of St. Augustine. Anglicans' dog-in-the-manger policy is brought out in a correspondence on this subject in the London "Saturday Review" (Dec., 1908 to March, 1909).

Source

Catholic Encyclopedia (https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/13121a.htm)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the Gods and Goddesses of Greece were black | Gnostic Warrior By Moe Bedard

(By Sir Godfrey Higgins) – Osiris and his Bull were black; all the Gods and Goddesses of Greece were black: at least this was the case with Jupiter, Bacchus, Hercules, Apollo, Amnion.The Goddesses Venus, Isis, Hecati, Diana, Juno, Metis, Ceres, Cybile, are black. The Multimammia is black in the Campidoglio at Rome, and in Montfaucon, Antiquity explained.The Linghams in India, anointed with oil, are black: a black stone was adored in numbers of places in India.

It has already been observed that, in the galleries, we constantly see busts and statues of the Roman Emperors, made of two kinds of stone; the human part of the statue of black stone, the drapery white or coloured. When they are thus described, I suppose they are meant to be represented as priests of the sun; this was probably confined to the celebration of the Isiac or Egyptian ceremonies.

On the colour of the Gods of the ancients, and of the identity of them all with the God Sol, and with the Cristna of India, nothing more need be said. The reader has already seen the striking marks of similarity in the history of Cristna and the stories related of Jesus in the Romish and heretical books. He probably will not think that their effect is destroyed, as Mr. Maurice flatters himself, by the word Cristna in the Indian language signifying black, and the God being of that colour, when he is informed, of what Mr. Maurice was probably ignorant, that in all the Romish countries of Europe, in France, Italy, German, the God Christ, as well as his mother, are described in their old pictures and statues to be black.

The infant God in the arms of his black mother, his eyes and drapery white, is himself perfectly black. If the reader doubt my word, he may go to the cathedral at Moulins—to the famous chapel of the Virgin at Loretto—to the church of the Annunciata—the church of St. Lazaro, or the church of St. Stephen at Genoa—to St. Francisco at Pisa—to the church at Brixen, in the Tyrol, and to that at Padua—to the church of St. Theodore, at Munich, in the two last of which the whiteness of the eyes and teeth, and the studied redness of the lips, are very observable ;—to a church and to the cathedral at Augsburg, where are a black virgin and child as large as life:—to Rome, to the Borghese chapel Maria Maggiore—to the Pantheon—to a small chapel of St. Peter’s, on the right-hand side on entering, near the door; and, in fact, to almost innumerable other churches, in countries professing the Romish religion.

They are generally esteemed by the rabble with the most profound veneration. The toes are often white, the brown or black paint being kissed away by the devotees, and the white wood left. No doubt in many places, when the priests have new-painted the images, they have coloured the eyes, teeth, &c, in order that they might not shock the feelings of devotees by a too sudden change from black to white, and in order, at the same time, that they might furnish a decent pretence for their blackness, viz. that they are an imitation of bronze: but the number that are left with white teeth, &c, let out the secret.

When the circumstance has been named to the Romish priests, they have endeavoured to disguise the fact, by pretending that the child had become black by the smoke of the candles; but it was black where the smoke of a candle never came: and, besides, how came the candles not to blacken the white of the eyes, the teeth, and the shirt, and how came they to redden the lips? The mother is, the author believes, always black, when the child is. Their real blackness is not to be questioned for a moment.

If the author had wished to invent a circumstance to corroborate the assertion, that the Romish Christ of Europe is the Cristna of India, how could he have desired any thing more striking than the fact of the black Virgin and Child being so common in the Romish countries of Europe? A black virgin and child among the white Germans, Swiss, French, and Italians!!!

The Romish Cristna is black in India, black in Europe, and black he must remain—like the ancient Gods of Greece, as we have just seen. But, after all, what was he but their Jupiter, the second person of their Trimurti or Trinity, the Logos of Parmenides and Plato, an incarnation or emanation of the solar power?

I must now request my reader to turn back to the first chapter, and to reconsider what I have said respecting the two Ethiopias and the existence of a black nation in a very remote period. When he has done this, the circumstance of the black God of India being called Cristna, and the God of Italy, Christ, being also black, must appear worthy of deep consideration. Is it possible, that this coincidence can have been the effect of accident? In our endeavours to recover the lost science of former ages, it is necessary that we should avail ourselves of rays of light scattered in places the most remote, and that we should endeavour to re-collect them into a focus, so that, by this means, we may procure as strong a light as possible: collect as industriously as we may, our light will not be too strong.

I think I need say no more in answer to Mr. Maurice’s shouts of triumph over those whom he insultingly calls impious infidels, respecting the name of Cristna having the meaning of black.

I will now proceed to his other solemn considerations.

The second particular to which Mr. Maurice desires the attention of his reader, is in the following terms: “N, Let it, in the next place, be considered that Chreeshna, so far from being “the son of a virgin, is declared to have had a father and mother in the flesh, and to have been “the eighth child of Devaci and Vasudeva. How inconceivably different this from the sanctity “of the immaculate conception of Christ!”

I answer, that respecting their births they differ; but what has this to do with the points wherein they agree? No one ever said they agreed in every minute particular. Yet I think, with respect to their humanity, the agreement continues. I always understood that Jesus was held by the Romish and Protestant Churches to have become incarnate; that the word was made flesh.’2 That is, that Jesus was of the same kind of flesh, at least as his mother, and also as his brothers, Joses, James, &c.3 If he were not of the flesh of his mother, what was he before the umbilical cord was cut?

It does not appear from the histories, which we have yet obtained, that the immaculate conception. But though the Bull of Osiris was black, the Bull of Europa was white. The story states that Jupiter fell in love with a daughter of Agenor, king of Phoenicia, and Telephassa, and in order to obtain the object of his affections he changed himself into a white bull. After he had seduced the nymph to play with him and caress him in his pasture for some time, at last he persuaded her to mount him, when he fled with her to Crete, where he succeeded in his wishes, and by her he had Minos, Sarpcdon, and Rhadamunthus. Is it necessary for me to point out to the reader in this pretty allegory the peopling of Europe from Phoenicia, and the allusion in the colour of the Bull, viz. tchite, to the fair complexions of the Europeans? An ingenious explanation of this allegory may be seen in Drummond’s Origines, Vol. III. p. 84.* John, ch. i. ver. 14.

I look with perfect contempt on the ridiculous trash which has been put forth to shew that the brothers of Jesus, described in the Gospels, did not mean brothers, but cousins!

#Black Gods#Stolen Gods#All the Gods and Goddesses of Greece were black | Gnostic Warrior#greek lies#African Gods

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

it is my personal belief that the Church of England and the Church of Rome should make real efforts to achieve unity, and that this objective, though difficult, is possible, perhaps even in my lifetime.

Too often, a strategy of just 'acknowledging' our each other is employed. Representatives from each group will meet each other, perhaps pray together, 'acknowledge' our shared histories and then continuing as normal is employed. This is not productive enough.

Many Anglicans, especially our bishops, share doctrinal beliefs with the Romish Church. Even the usually quite Evangelical Archbishop Welby has visited the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham. Even the very evangelical Bishop of Oxford will don a cope and mitre for services.

Of course, our churches are by no means the same. We have customs and practices which cannot really be fit cleanly into the Latin Church. I suppose it would be better for the Church of England to become a 'sui iuris' church, which would mostly allow us to do our own thing, but put us in full communion with Rome.

But make no mistake - Anglicans must be Anglican. The solution is not a great conversion to the Latin church; that would abandon the ancient and stablished church of this country, and leave her empty. The ancient bishoprics must not be left vacant. Anglicans should not go and submit to the present Romish dioceses and bishops which have existed in England since 1852; rather the Anglican dioceses should be brought back into the fold themselves, making the C19 Romish dioceses redundant. So the diocese of Norwich must not be dissolved in favour of that or East Anglia, rather that of Norwich ought to be reconciled with Rome, so that the diocese of East Anglia becomes redundant.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Poor Claire (1856) by Elizabeth Gaskell, chapter 1

December 12th, 1747 - My life has been strangely bound up with extraordinary incidents, some of which occurred before I had any connection with the principal actors in them, or, indeed, before I even knew of their existence. I suppose, most old men are, like me, more given to looking back upon their own career with a kind of fond interest and affectionate remembrance than to watching the events - though these may have far more interest for the multitude - immediately passing before their eyes. If this should be the case with the generality of old people, how much more so with me! . . . If I am to enter upon that strange story connected with poor Lucy, I must begin a long way back. I myself only came to the knowledge of her family history after I knew her; but, to make the tale clear to any one else, I must arrange events in the order in which they occurred - not that in which I became acquainted with them.

There is a great old hall in the north-east of Lancashire, in a part they called the Trough of Bolland, adjoining that other district named Craven. Starkey Manor-house is rather like a number of rooms clustered round a grey, massive, old keep than a regularly-built hall. Indeed, I suppose that the house only consisted of a great tower in the centre, in the days when the Scots made their raids terrible as far south as this; and that after the Stuarts came in, and there was a little more security of property in those parts, the Starkeys of that time added the lower building, which runs, two storeys high, all round the base of the keep. There has been a grand garden laid out in my days, on the southern slope near the house; but when I first knew the place, the kitchen garden at the farm was the only piece of cultivated ground belonging to it. The deer used to come within sight of the drawing-room windows, and might have browsed quite close up to the house if they had not been too wild and shy. Starkey Manor-house itself stood on a projection or peninsula of high land, jutting out from the abrupt hills that form the sides of the Trough of Bolland. These hills were rocky and bleak enough towards their summit; lower down they were clothed with tangled copsewood and green depths of fern, out of which a grey giant of an ancient forest-tree would tower here and there, throwing up its ghastly white branches, as if in imprecation, to the sky. These trees, they told me, were the remnants of that forest which existed in the days of the Heptarchy, and were even then noted as landmarks. No wonder that their upper and more exposed branches were leafless, and that the dead bark had peeled away, from sapless old age.

Not far from the house there were a few cottages, apparently of the same date as the keep; probably built for some retainers of the family, who sought shelter - they and their families and their small flocks and herds - at the hands of their feudal lord. Some of them had pretty much fallen to decay. They were built in a strange fashion. Strong beams had been sunk firm in the ground at the requisite distance, and their other ends had been fastened together, two and two, so as to form the shape of one of those rounded waggon-headed gipsy-tents, only very much larger. The spaces between were filled with mud, stones, osiers, rubbish, mortar - anything to keep out the weather. The fires were made in the centre of these rude dwellings, a hole in the roof forming the only chimney. No Highland hut or Irish cabin could be of rougher construction.

The owner of this property at the beginning of the present century, was a Mr. Patrick Byrne Starkey. His family had kept to the old faith, and were staunch Roman Catholics, esteeming it even a sin to marry any one of Protestant descent, however willing he or she might have been to embrace the Romish religion. Mr. Patrick Starkey's father had been a follower of James the Second; and during the disastrous campaign of that monarch he had fallen in love with an Irish beauty, a Miss Byrne, as zealous for her religion and for the Stuarts as himself. He had returned to Ireland after his escape to France, and married her, bearing her back to the court at St. Germains. But some license, on the part of the disorderly gentlemen who surrounded King James in his exile, had insulted his beautiful wife, and disgusted him; so he removed from St. Germains to Antwerp, whence, in a few years' time, he quietly returned to Starkey Manor-house - some of his Lancashire neighbours having lent their good offices to reconcile him to the powers that were. He was as firm a Catholic as ever, and as staunch an advocate for the Stuarts and the divine rights of kings; but his religion almost amounted to asceticism, and the conduct of those with whom he had been brought in such close contact at St. Germains would little bear the inspection of a stern moralist. So he gave his allegiance where he could not give his esteem and learned to respect sincerely the upright and moral character of one whom he yet regarded as an usurper. King William's government had little need to fear such a one. So he returned, as I have said, with a sobered heart and impoverished fortunes, to his ancestral house, which had fallen sadly to ruin while the owner had been a courtier, a soldier, and an exile. The roads into the Trough of Bolland were little more than cart-ruts; indeed, the way up to the house lay along a ploughed field before you came to the deer-park. Madam, as the country-folk used to call Mrs. Starkey, rode on a pillion behind her husband, holding on to him with a light hand by his leather riding-belt. Little master (he that was afterwards Squire Patrick Byrne Starkey) was held on to his pony by a serving-man. A woman past middle age walked, with a firm and strong step, by the cart that held much of the baggage; and, high up on the mails and boxes, sat a girl of dazzling beauty, perched lightly on the topmost trunk, and swaying herself fearlessly to and fro, as the cart rocked and shook in the heavy roads of late autumn. The girl wore the Antwerp faille, or black Spanish mantle, over her head; and altogether her appearance was such that the old cottager, who described the procession to me many years after, said that all the country-folk took her for a foreigner. Some dogs, and the boy who held them in charge, made up the company. They rode silently along, looking with grave, serious eyes at the people, who came out of the scattered cottages to bow or curtsey to the real Squire, 'come back at last,' and gazed after the little procession with gaping wonder, not deadened by the sound of the foreign language in which the few necessary words that passed among them were spoken. One lad, called from his staring by the Squire to come and help about the cart, accompanied them to the Manor-house. He said that when the lady had descended from her pillion, the middle-aged woman whom I have described as walking while the others rode, stepped quickly forward; and, taking Madame Starkey (who was of a slight and delicate figure) in her arms, she lifted her over the threshold, and set her down in her husband's house, at the same time uttering a passionate and outlandish blessing. The Squire stood by, smiling gravely at first; but when the words of blessing were pronounced, he took off his fine feathered hat and bent his head. The girl with the black mantle stepped onward into the shadow of the dark hall, and kissed the lady's hand; and that was all the lad could tell to the group that gathered round him on his return, eager to hear everything, and to know how much the Squire had given him for his services.

From all I could gather, the Manor-house, at the time of the Squire's return, was in the most dilapidated state. The stout grey walls remained firm and entire; but the inner chambers had been used for all kinds of purposes. The great withdrawing-room had been a barn; the state tapestry-chamber had held wool, and so on. But, by-and-by, they were cleared out; and, if the Squire had no money to spend on new furniture, he and his wife had the knack of making the best of the old. He was no despicable joiner; she had a kind of grace in whatever she did, and imparted an air of elegant picturesqueness to whatever she touched. Besides, they had brought many rare things from the Continent; perhaps I should rather say, things that were rare in that part of England - carvings, and crosses, and beautiful pictures. And then, again, wood was plentiful in the Trough of Bolland, and great log-fires danced and glittered in all the dark, old rooms, and gave a look of home and comfort to everything. Why do I tell you all this? I have little to do with the Squire and Madame Starkey; and yet I dwell upon them, as if I were unwilling to come to the real people with whom my life was so strangely mixed up. Madam had been nursed in Ireland by the very woman who lifted her in her arms, and welcomed her to her husband's home in Lancashire. Excepting for the short period of her own married life, Bridget Fitzgerald had never left her nursling. Her marriage - to one above her in rank - had been unhappy. Her husband had died, and left her in even greater poverty than that in which she was when he had first met with her. She had one child, the beautiful daughter who came riding on the waggon-load of furniture that was brought to the Manor-house. Madame Starkey had taken her again into her service when she became a widow. She and her daughter had followed 'the mistress' in all her fortunes; they had lived at St. Germains and at Antwerp, and were now come to her home in Lancashire. As soon as Bridget had arrived there, the Squire gave her a cottage of her own, and took more pains in furnishing it for her than he did in anything else out of his own house. It was only nominally her residence. She was constantly up at the great house; indeed, it was but a short cut across the woods from her own home to the home of her nursling. Her daughter Mary, in like manner, moved from one house to the other at her own will. Madam loved both mother and child dearly. They had great influence over her and, through her, over her husband. Whatever Bridget or Mary willed was sure to come to pass. They were not disliked; for though wild and passionate, they were also generous by nature. But the other servants were afraid of them, as being in secret the ruling spirits of the household. The Squire had lost his interest in all secular things; Madam was gentle, affectionate, and yielding. Both husband and wife were tenderly attached to each other and to their boy; but they grew more and more to shun the trouble of decision on any point; and hence it was that Bridget could exert such despotic power. But, if every one else yielded to her 'magic of a superior mind,' her daughter not unfrequently rebelled. She and her mother were too much alike to agree. There were wild quarrels between them, and wilder reconciliations. There were times when, in the heat of passion, they could have stabbed each other. At all other times they both - Bridget especially - would have willingly laid down their lives for one another. Bridget's love for her child lay very deep - deeper than that daughter ever knew; or, I should think, she would never have wearied of home as she did, and prayed her mistress to obtain for her some situation - as waiting-maid beyond the seas, in that more cheerful continental life, among the scenes of which so many of her happiest years had been spent. She thought, as youth thinks, that life would last for ever, and that two or three years were but a small portion of it to pass away from her mother, whose only child she was. Bridget thought differently, but was too proud ever to show what she felt. If her child wished to leave her, why - she should go. But people said Bridget became ten years older in the course of two months at this time. She took it that Mary wanted to leave her. The truth was that Mary wanted for a time to leave the place, and to seek some change, and would thankfully have taken her mother with her.

Indeed, when Madame Starkey had gotten her a situation with some grand lady abroad, and the time drew near for her to go, it was Mary who clung to her mother with passionate embrace, and, with floods of tears, declared that she would never leave her; and it was Bridget who at last loosened her arms, and, grave and tearless herself, bade her keep her word, and go forth into the wide world. Sobbing aloud, and looking back continuously, Mary went away. Bridget was still as death, scarcely drawing her breath, or closing her stony eyes; till at last she turned back into her cottage, and heaved a ponderous old settle against the door. There she sat, motionless, over the grey ashes of her extinguished fire, deaf to Madam's sweet voice, as she begged leave to enter and comfort her nurse. Deaf, stony, and motionless, she sat for more than twenty hours; till, for the third time, Madam came across the snowy path from the great house carrying with her a young spaniel, which had been Mary's pet up at the hall, and which had not ceased all night long to seek for its absent mistress, and to whine and moan after her. With tears Madam told this story, through the closed door - tears excited by the terrible look of anguish, so steady, so immovable, so the same today as it was yesterday - on her nurse's face. The little creature in her arms began to utter its piteous cry, as it shivered with the cold. Bridget stirred; she moved - she listened. Again that long whine; she thought it was for her daughter; and what she had denied to her nursling and mistress she granted to the dumb creature that Mary had cherished. She opened the door, and took the dog from Madam's arms. Then Madam came in, and kissed and comforted the old woman, who took but little notice of her or anything. And, sending up Master Patrick to the hall for fire and food, the sweet young lady never left her nurse all that night. Next day the Squire himself came down, carrying a beautiful foreign picture - Our Lady of the Holy Heart, the Papists call it. It is a picture of the Virgin, her heart pierced with arrows, each arrow representing one of her great woes. That picture hung in Bridget's cottage when I first saw her; I have that picture now.

Years went on. Mary was still abroad. Bridget was still and stern, instead of active and passionate. The little dog, Mignon, was indeed her darling. I have heard that she talked to it continually; although, to most people, she was so silent. The Squire and Madam treated her with the greatest consideration, and well they might; for to them she was as devoted and faithful as ever. Mary wrote pretty often, and seemed satisfied with her life. But at length the letters ceased - I hardly know whether before or after a great and terrible sorrow came upon the house of the Starkeys. The Squire sickened of a putrid fever; and Madam caught it in nursing him, and died. You may be sure, Bridget let no other woman tend her but herself, and in the very arms that had received her at birth, that sweet young woman laid her head down, and gave up her breath. The Squire recovered, in a fashion. He was never strong - he had never the heart to smile again. He fasted and prayed more than ever; and people did say that he tried to cut off the entail, and leave all the property away to found a monastery abroad, of which he prayed that some day little Squire Patrick might be the reverend father. But he could not do this, for the strictness of the entail and the laws against the Papists. So he could only appoint gentlemen of his own faith as guardians to his son, with many charges about the lad's soul, and a few about the land, and the way it was to be held while he was a minor. Of course, Bridget was not forgotten. He sent for her as he lay on his death-bed, and asked her if she would rather have a sum down, or have a small annuity settled upon her. She said at once she would have a sum down; for she thought of her daughter, and how she could bequeath the money to her, whereas an annuity would have died with her. So the Squire left her her cottage for life, and a fair sum of money. And then he died, with as ready and willing a heart as, I suppose, any gentleman took out of this world with him. The young Squire was carried off by his guardians, and Bridget was left alone.

I have said that she had not heard from Mary for some time. In her last letter, she had told of travelling about with her mistress, who was the English wife of some great foreign officer, and had spoken of her chances of making a good marriage, without naming the gentleman's name, keeping it rather back as a pleasant surprise to her mother; his station and fortune being, as I had afterwards reason to know, far superior to anything she had a right to expect. Then came a long silence; and Madam was dead, and the Squire was dead; and Bridget's heart was gnawed by anxiety, and she knew not whom to ask for news of her child. She could not write, and the Squire had managed her communication with her daughter. She walked off to Hurst; and got a good priest there - one whom she had known at Antwerp - to write for her. But no answer came. It was like crying into the awful stillness of night.

One day, Bridget was missed by those neighbours who had been accustomed to mark her goings-out and comings-in. She had never been sociable with any of them; but the sight of her had become a part of their daily lives, and slow wonder arose in their minds, as morning after morning came, and her house-door remained closed, her window dead from any glitter, or light of fire within. At length, some one tried the door; it was locked. Two or three laid their heads together, before daring to look in through the blank unshuttered window. But, at last, they summoned up courage, and then saw that Bridget's absence from their little world was not the result of accident or death, but of premeditation. Such small articles of furniture as could be secured from the effects of time and damp by being packed up, were stowed away in boxes. The picture of the Madonna was taken down, and gone. In a word, Bridget had stolen away from her home, and left no trace whither she had departed. I knew afterwards, that she and her little dog had wandered off on a long search for her lost daughter. She was too illiterate to have faith in letters, even had she had the means of writing and sending many. But she had faith in her own strong love, and believed that her passionate instinct would guide her to her child. Besides, foreign travel was no new thing to her, and she could speak enough of French to explain the object of her journey, and had, moreover, the advantage of being, from her faith, a welcome object of charitable hospitality at many a distant convent. But the country people round Starkey Manor-house knew nothing of all this. They wondered what had become of her, in a torpid, lazy fashion, and then left off thinking of her altogether. Several years passed. Both Manor-house and the cottage were deserted. The young Squire lived far away under the direction of his guardians. There were inroads of wool and corn into the sitting-rooms of the Hall; and there was some low talk, from time to time, among the hinds and country people, whether it would not be as well to break into old Bridget's cottage, and save such of her goods as were left from the moth and rust which must be making sad havoc. But this idea was always quenched by the recollection of her strong character and passionate anger; and tales of her masterful spirit, and vehement force of will, were whispered about, till the very thought of offending her, by touching any article of hers, became invested with a kind of horror: and it was believed that, dead or alive, she would not fail to avenge it.

Suddenly she came home; with as little noise or note of preparation as she had departed. One day some one noticed a thin, blue curl of smoke ascending from her chimney. Her door stood open to the noon-day sun; and, ere many hours had elapsed, some one had seen an old travel-and-sorrow-stained woman, dipping her pitcher in the well, and said, that the dark, solemn eyes that looked up at him were more like Bridget Fitzgerald's than any one else's in this world; and yet, if it were she, she looked as if she had been scorched in the flames of hell, so brown, and scared, and fierce a creature did she seem. By-and-by many saw her; and those who met her eye once cared not to be caught looking at her again. She had got into the habit of perpetually talking to herself; nay, more, answering herself, and varying her tones according to the side she took at the moment. It was no wonder that those who dared to listen outside her door at night believed that she held converse with some spirit; in short, she was unconsciously earning for herself the dreadful reputation of a witch.

Her little dog, which had wandered half over the Continent with her, was her only companion; a dumb remembrancer of happier days. Once he was ill; and she carried him more than three miles to ask about his management from one who had been groom to the last Squire, and had then been noted for his skill in all diseases of animals. Whatever this man did, the dog recovered; and they who heard her thanks, intermingled with blessings (that were rather promises of good fortune than prayers), looked grave at his good luck when, next year, his ewes twinned, and his meadow-grass was heavy and thick.

Now it so happened that, about the year seventeen hundred and eleven, one of the guardians of the young squire, a certain Sir Philip Tempest, bethought him of the good shooting there must be on his ward's property; and in consequence he brought down four or five gentlemen, of his friends, to stay for a week or two at the hall. From all accounts, they roystered and spent pretty freely. I never heard any of their names but one, and that was Squire Gisborne's. He was hardly a middle-aged man then; he had been abroad; and there, I believe, he had known Sir Philip Tempest, and done him some service. He was a daring and dissolute fellow in those days: careless and fearless, and one who would rather be in a quarrel than out of it. He had his fits of ill-temper besides, when he would spare neither man nor beast. Otherwise, those who knew him well, used to say he had a good heart, when he was neither drunk, nor angry, nor in any way vexed. He had altered much when I came to know him.

One day, the gentlemen had all been out shooting, and with but little success, I believe; anyhow, Mr. Gisborne had none, and was in a black humour accordingly. He was coming home, having his gun loaded, sportsman-like, when little Mignon crossed his path, just as he turned out of the wood by Bridget's cottage. Partly for wantonness, partly to vent his spleen upon some living creature, Mr. Gisborne took his gun, and fired - he had better have never fired gun again, than aimed that unlucky shot: he hit Mignon, and at the creature's sudden cry, Bridget came out, and saw at a glance what had been done. She took Mignon up in her arms, and looked hard at the wound; the poor dog looked at her with his glazing eyes, and tried to wag his tail and lick her hand, all covered with blood. Mr. Gisborne spoke in a kind of sullen penitence:

'You should have kept the dog out of my way - a little poaching varmint.'

At this very moment, Mignon stretched out his legs, and stiffened in her arms - her lost Mary's dog, who had wandered and sorrowed with her for years. She walked right into Mr. Gisborne's path, and fixed his unwilling, sullen look, with her dark and terrible eye,

'Those never throve that did me harm,' said she. 'I'm alone in the world, and helpless: the more do the saints in the heaven hear my prayers. Hear me, ye blessed ones! hear me, while I ask for sorrow on this bad, cruel man. He has killed the only creature that loved me - the dumb beast that I loved. Bring down heavy sorrow on his head for it, O ye saints! He thought that I was helpless, because he saw me lonely and poor; but are not the armies of heaven for the like of me?'

'Come, come,' said he, half remorseful, but not one whit afraid, 'Here's a crown to buy thee another dog. Take it, and leave off cursing! I care none for thy threats.'

'Don't you?' said she, coming a step closer, and changing her imprecatory cry for a whisper which made the gamekeeper's lad, following Mr. Gisborne, creep all over. 'You shall live to see the creature you love best, and who alone loves you - ay, a human creature, but as innocent and fond as my poor, dead darling - you shall see this creature, for whom death would be too happy, become a terror and a loathing to all, for this blood's sake, Hear me, O holy saints, who never fail them that have no other help!'

She threw up her right hand, filled with poor Mignon's life-drops; they spirted, one or two of them, on his shooting dress - an ominous sight to the follower. But the master only laughed a little, forced, scornful laugh, and went on to the Hall. Before he got there, however, he took out a gold piece, and bade the boy carry it to the old woman on his return to the village. The lad was 'afeared', as he told me in after years; he came to the cottage, and hovered about, not daring to enter. He peeped through the window at last; and by the flickering wood-flame, he saw Bridget kneeling before the picture of Our Lady of the Holy Heart, with dead Mignon lying between her and the Madonna. She was praying wildly, as her outstretched arms betokened. The lad shrank away in redoubled terror; and contented himself with slipping the gold-piece under the ill-fitting door. The next day it was thrown out upon the midden; and there it lay, no one daring to touch it.

Meanwhile Mr. Gisborne, half curious, half uneasy, thought to lessen his uncomfortable feelings by asking Sir Philip who Bridget was? He could only describe her - he did not know her name. Sir Philip was equally at a loss. But an old servant of the Starkeys, who had resumed his livery at the Hall on this occasion - a scoundrel whom Bridget had saved from dismissal more than once during her palmy days - said:

'It will be the old witch, that his worship means. She needs a ducking, if ever a woman did, does that Bridget Fitzgerald.'

'Fitzgerald!' said both the gentlemen at once. But Sir Philip was the first to continue:

'I must have no talk of ducking her, Dickon. Why, she must be the very woman poor Starkey bade me have a care of; but when I came here last she was gone, no one knew where. I'll go and see her tomorrow. But mind you, sirrah, if any harm comes to her, or any more talk of her being a witch - I've a pack of hounds at home, who can follow the scent of a lying knave as well as ever they followed a dog-fox; so take care how you talk about ducking a faithful old servant of your dead master's.'

'Had she ever a daughter?' asked Mr. Gisborne, after a while.

'I don't know - yes! I've a notion she had: a kind of waiting-woman to Madame Starkey.'

'Please your worship,' said humbled Dickon. 'Mistress Bridget had a daughter - one Mistress Mary - who went abroad, and has never been heard of since; and folks do say that has crazed her mother.'

Mr. Gisborne shaded his eyes with his hand.