#SCARCITY

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

flenserpostings

#art#drawing#character design#the flenser#chat pile#planning for burial#have a nice life#ragana#midwife#mamaleek#uboa#agriculture#wreck and reference#amulets#drowse#scarcity#bosse-de-nage#succumb#street sects

722 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are truly no new Dex fics to read, so I end up creating entire self-insert plotlines in my head every night as I drift off to sleep.

#famine#scarcity#tragedy#for REAL#benjamin poindexter#benjamin poindexter x reader#you know what#i'll be the hero here#daredevil#bullseye

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

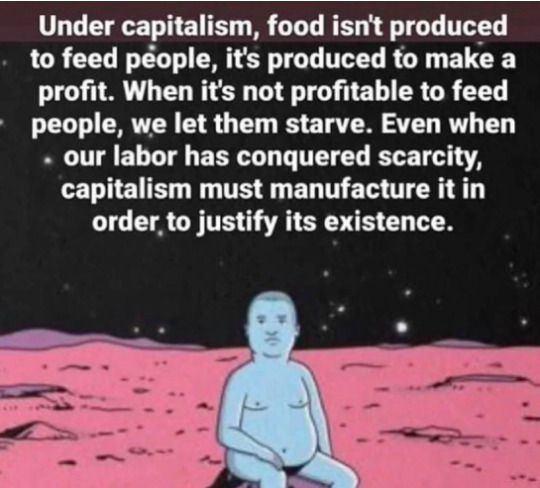

Degrowth scholarship notes that capitalist growth depends on the creation of artificial scarcity. Human needs can typically be satisfied either by means of relatively resource-efficient, non-commodified need satisfiers (for instance, public transit; food from a community kitchen), or by means of relatively scarce and resource-inefficient commodities (a privately owned car; a meal from a home-delivery service). Under capitalism, essential goods (housing, healthcare, transit, nutritious food, etc.) are commodified and access is mediated by prices that are often very high. To obtain the necessary income people are compelled to enter the capitalist labour market, working to produce things that may not be needed simply to access things that clearly are needed. Artificial scarcity of essential goods thus ensures a steady flow of labour for capitalist growth. It also creates growth dependencies: if productivity improvements (or recessions) lead to unemployment, people suffer loss of access to essential goods and growth is needed to create new jobs and resolve the social crisis. This dynamic explains why, despite capitalism's high levels of production and resource use, many basic needs remain unmet even in high-income countries. In this respect, capitalism is deeply inefficient and wasteful.

How to pay for saving the world: Modern Monetary Theory for a degrowth transition

883 notes

·

View notes

Text

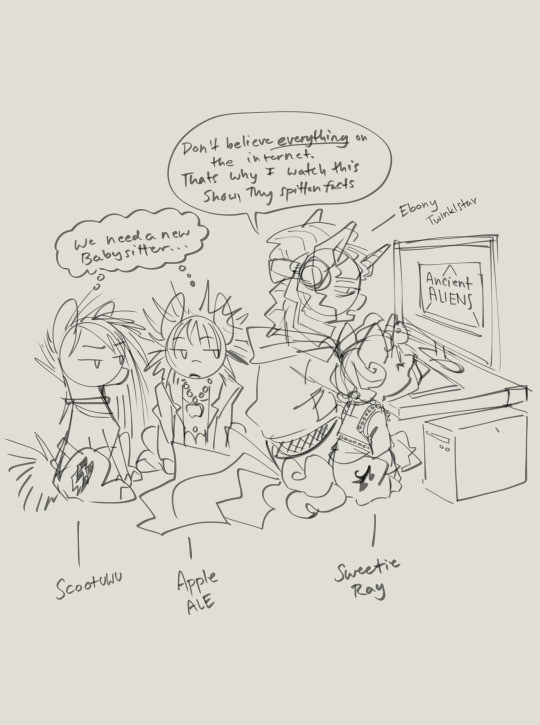

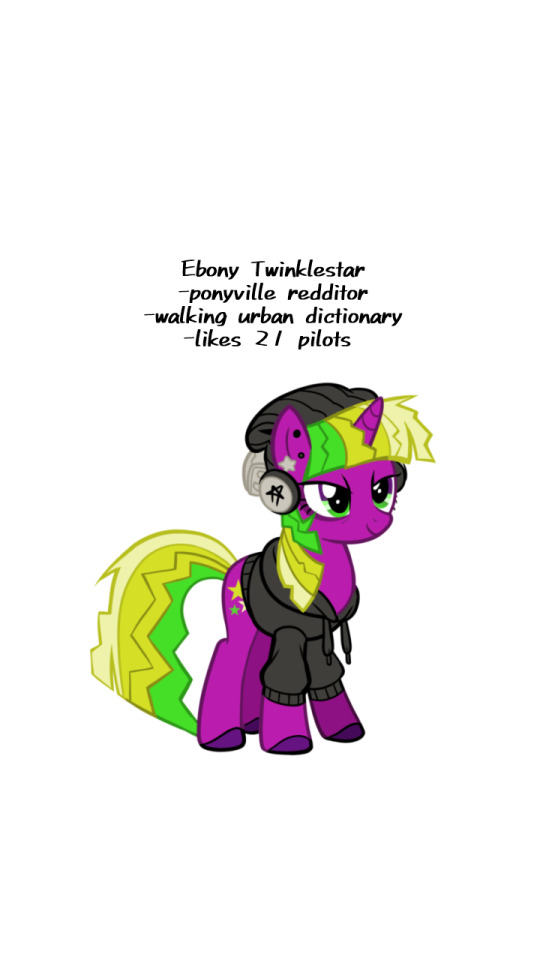

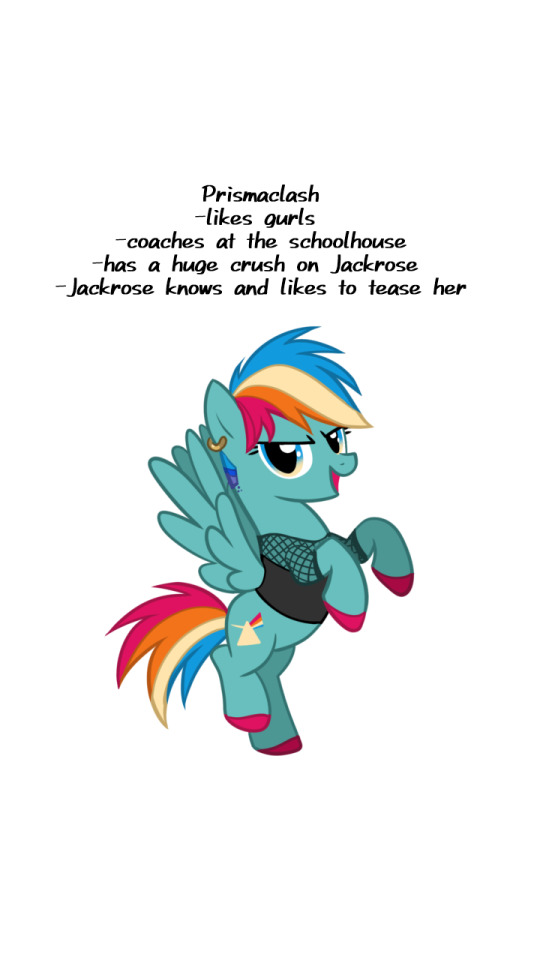

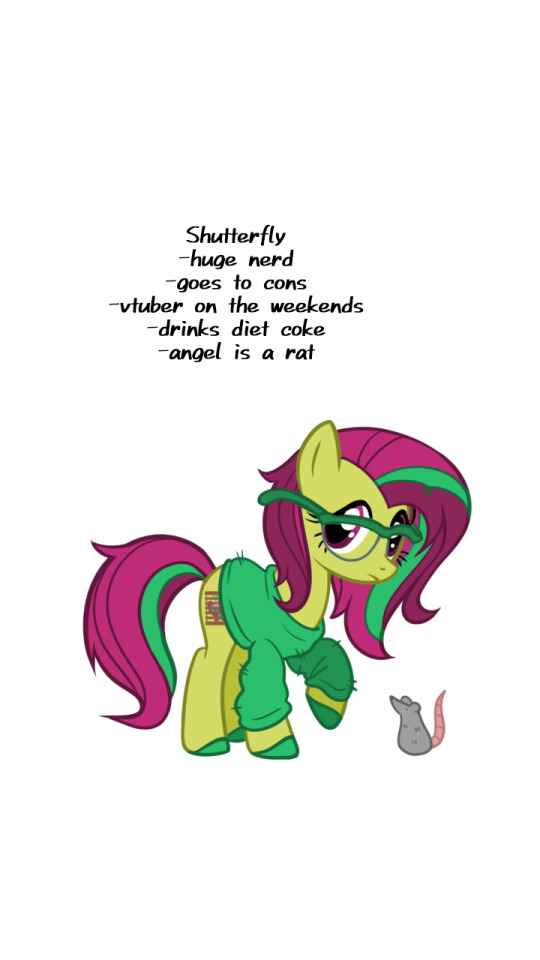

The alternative six 🎉

V description for each of them, I made these whilst congested so I might be cookin idk. (Alternative Cmc descriptions will come later)

#mlp#mlp au#twilight sparkle#rarity#applejack#pinkie pie#Flutter shy#rainbowdash#ebony twinklestar#rhinestone#scarcity#Jackrose#Shutter fly#Prismaclash#The alternative six

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good Morning!!! Trust The Science!!!

#morning#good morning#good morning message#good morning image#good morning man#the good morning man#the entire morning#gif#gm#tgmm#☀️🧙🏼♂️✌🏼#science#science school#sun#the sun#mr golden sun#scarcity#scarcity is a myth#con job#burn it down#burn it all down#doctor#arsonist#doctor patient confidentiality#patient

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

#koth#king of the hill#bobby hill#watchmen#anti capitalist memes#funny#funny memes#memes#meme#dank memes#funny meme#dank#scarcity#post-scarcity

207 notes

·

View notes

Quote

a distinctive amount of a reasonable scarcity improves value greatly

Ernest Agyemang Yeboah, The Untapped Wonderer in You: Dare to Do the Undone

#quotes#Ernest Agyemang Yeboah#The Untapped Wonderer in You: Dare to Do the Undone#thepersonalwords#literature#life quotes#prose#lit#spilled ink#improvement#inspirational-quotes#life#love#motivational-quotes#purpose#purposelessness#scarcity#scarcity-mentality

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

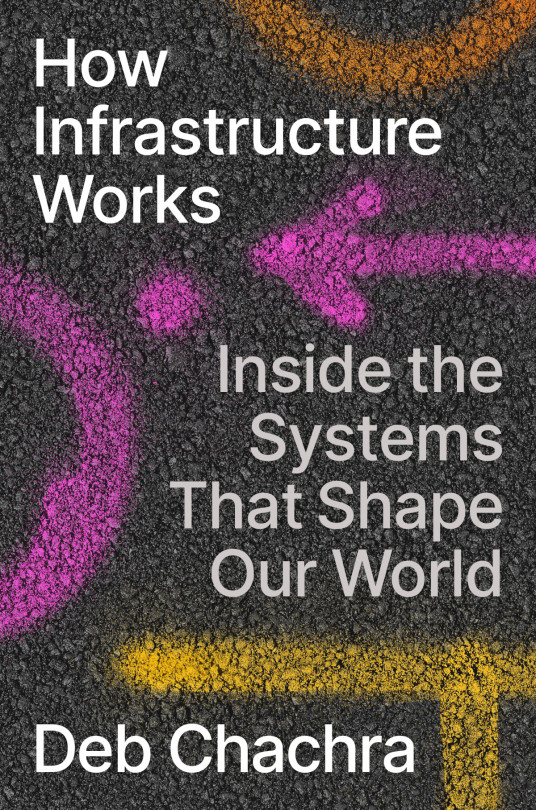

Deb Chachra's "How Infrastructure Works": Mutual aid, the built environment, the climate, and a future of comfort and abundance

This Thursday (Oct 19), I'm in Charleston, WV to give the 41st annual McCreight Lecture in the Humanities. And on Friday (Oct 20), I'm at Charleston's Taylor Books from 12h-14h.

Engineering professor and materials scientist Deb Chachra's new book How Infrastructure Works is a hopeful, lyrical – even beautiful – hymn to the systems of mutual aid we embed in our material world, from sewers to roads to the power grid. It's a book that will make you see the world in a different way – forever:

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/612711/how-infrastructure-works-by-deb-chachra/

Chachra structures the book as a kind of travelogue, in which she visits power plants, sewers, water treatment plants and other "charismatic megaprojects," connecting these to science, history, and her own memoir. In so doing, she doesn't merely surface the normally invisible stuff that sustains us all, but also surfaces its normally invisible meaning.

Infrastructure isn't merely a way to deliver life's necessities – mobility, energy, sanitation, water, and so on – it's a shared way of delivering those necessities. It's not just that economies of scale and network effects don't merely make it more efficient and cheaper to provide these necessities to whole populations. It's also that the lack of these network and scale effects make it unimaginable that these necessities could be provided to all of us without being part of a collective, public project.

Think of the automobile versus public transit: if you want to live in a big, built up city, you need public transit. Once a city gets big enough, putting everyone who needs to go everywhere in a car becomes a Red Queen's Race. With that many cars on the road, you need more roads. More roads push everything farther apart. Once everything is farther apart, you need more cars.

Geometry hates cars. You can't bargain with geometry. You can't tunnel your way out of this. You can't solve it with VTOL sky-taxis. You can't fix it with self-driving cars whose car-to-car comms let them shave down their following distances. You need buses, subways and trams. You need transit. There's a reason that every plan to "disrupt" transportation ends up reinventing the bus:

https://stanforddaily.com/2018/04/09/when-silicon-valley-accidentally-reinvents-the-city-bus/

Even the cities we think of as motorists' paradises – such as LA – have vast, extensive transit systems. They suck – because they are designed for poor people – but without them, the city would go from traffic-blighted to traffic-destroyed.

The dream of declaring independence from society, of going "off-grid," of rejecting any system of mutual obligation and reliance isn't merely an infantile fantasy – it also doesn't scale, which is ironic, given how scale-obsessed its foremost proponents are in their other passions. Replicating sanitation, water, rubbish disposal, etc to create individual systems is wildly inefficient. Creating per-person communications systems makes no sense – by definition, communications involves at least two people.

So infrastructure, Chachra reminds us, is a form of mutual aid. It's a gift we give to ourselves, to each other, and to the people who come after us. Any rugged individualism is but a thin raft, floating on an ocean of mutual obligation, mutual aid, care and maintenance.

Infrastructure is vital and difficult. Its amortization schedule is so long that in most cases, it won't pay for itself until long after the politicians who shepherded it into being are out of office (or dead). Its duty cycle is so long that it can be easy to forget it even exists – especially since the only time most of us notice infrastructure is when it stops working.

This makes infrastructure precarious even at the best of times – hard to commit to, easy to neglect. But throw in the climate emergency and it all gets pretty gnarly. Whatever operating parameters we've designed into our infra, whatever maintenance regimes we've committed to for it, it's totally inadequate. We're living through a period where abnormal is normal, where hundred year storms come every six months, where the heat and cold and wet and dry are all off the charts.

It's not just that the climate emergency is straining our existing infrastructure – Chachra makes the obvious and important point that any answer to the climate emergency means building a lot of new infrastructure. We're going to need new systems for power, transportation, telecoms, water delivery, sanitation, health delivery, and emergency response. Lots of emergency response.

Chachra points out here that the history of big, transformative infra projects is…complicated. Yes, Bazalgette's London sewers were a breathtaking achievement (though they could have done a better job separating sewage from storm runoff), but the money to build them, and all the other megaprojects of Victorian England, came from looting India. Chachra's family is from India, though she was raised in my hometown of Toronto, and spent a lot of her childhood traveling to see family in Bhopal, and she has a keen appreciation of the way that those old timey Victorian engineers externalized their costs on brown people half a world away.

But if we can figure out how to deliver climate-ready infra, the possibilities are wild – and beautiful. Take energy: we've all heard that Americans use far more energy than most of their foreign cousins (Canadians and Norwegians are even more energy-hungry, thanks to their heating bills).

The idea of providing every person on Earth with the energy abundance of an average Canadian is a horrifying prospect – provided that your energy generation is coupled to your carbon emissions. But there are lots of renewable sources of energy. For every single person on Earth to enjoy the same energy diet as a Canadian, we would have to capture a whopping four tenths of a percent of the solar radiation that reaches the Earth. Four tenths of a percent!

Of course, making solar – and wind, tidal, and geothermal – work will require a lot of stuff. We'll need panels and windmills and turbines to catch the energy, batteries to store it, and wires to transmit it. The material bill for all of this is astounding, and if all that material is to come out of the ground, it'll mean despoiling the environments and destroying the lives of the people who live near those extraction sites. Those are, of course and inevitably, poor and/or brown people.

But all those materials? They're also infra problems. We've spent millennia treating energy as scarce, despite the fact that fresh supplies of it arrive on Earth with every sunrise and every moonrise. Moreover, we've spent that same period treating materials as infinite despite the fact that we've got precisely one Earth's worth of stuff, and fresh supplies arrive sporadically, unpredictably, and in tiny quantities that usually burn up before they reach the ground.

Chachra proposes that we could – we must – treat material as scarce, and that one way to do this is to recognize that energy is not. We can trade energy for material, opting for more energy intensive manufacturing processes that make materials easier to recover when the good reaches its end of life. We can also opt for energy intensive material recovery processes. If we put our focus on designing objects that decompose gracefully back into the material stream, we can build the energy infrastructure to make energy truly abundant and truly clean.

This is a bold engineering vision, one that fuses Chachra's material science background, her work as an engineering educator, her activism as an anti-colonialist and feminist. The way she lays it out is just…breathtaking. Here, read an essay of hers that prefigures this book:

https://tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-75-resilience-abundance-decentralization

How Infrastructure Works is a worthy addition to the popular engineering books that have grappled with the climate emergency. The granddaddy of these is the late David MacKay's open access, brilliant, essential, Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air, a book that will forever change the way you think about energy:

https://memex.craphound.com/2009/04/08/sustainable-energy-without-the-hot-air-the-freakonomics-of-conservation-climate-and-energy/

The whole "Without the Hot Air" series is totally radical, brilliant, and beautiful. Start with the Sustainable Materials companion volume to understand why everything can be explained by studying, thinking about and changing the way we use concrete and aluminum:

https://memex.craphound.com/2011/11/17/sustainable-materials-indispensable-impartial-popular-engineering-book-on-the-future-of-our-built-and-made-world/

And then get much closer to home – your kitchen, to be precise – with the Food and Climate Change volume:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/01/06/methane-diet/#3kg-per-day

Reading Chachra's book, I kept thinking about Saul Griffith's amazing Electrify, a shovel-ready book about how we can effect the transition to a fully electrified America:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/12/09/practical-visionary/#popular-engineering

Chachra's How Infrastructure Works makes a great companion volume to Electrify, a kind of inspirational march to play accompaniment on Griffith's nuts-and-bolts journey. It's a lyrical, visionary book, charting a bold course through the climate emergency, to a world of care, maintenance, comfort and abundance.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/10/17/care-work/#charismatic-megaprojects

My next novel is The Lost Cause, a hopeful novel of the climate emergency. Amazon won't sell the audiobook, so I made my own and I'm pre-selling it on Kickstarter!

#pluralistic#books#reviews#deb chachra#debcha#engineering#infrastructure#free energy#material science#abundance#scarcity#mutual aid#maintenance#99 percent invisible#colonialism#gift guide

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#my art#sketchbook#gori cuddly carnage#gori#erika#spamelle#bugbo#jax#the amazing digital circus#fraggle rock#wembley fraggle#mokey fraggle#scarcity#addisons#angel hare#angel gabby#gobo fraggle#zooble

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is just my interpretation so here goes:

"Punk" as a suffix is inherently about anti-establishment. Therefore:

Cyberpunk -> Mega-corporations control the media and hoard resources and anyone not consuming mindlessly is a threat

Desertpunk -> Water is hoarded by either petty warlords or mega-corporations and the hero is often someone fighting or existing outside the system. Mad Max comes to mind but Tank Girl also. Basically, any setting where drinking water is treated as crude oil and all the conflict that entails.

Oceanpunk -> Not quite the opposite of Desertpunk. Instead of arid deserts, it's vast swathes of ocean with little islands (floating or stationary). An authoritarian regime controls or wishes to control the waters and its inhabitants. Land can be a resource or ancient technology from the "old world" can drive the conflict. One Piece, Waterworld, Flapjack, any setting where boats are used frequently as transportation and the setting. I wanna see more submarines in this genre.

Scavengepunk -> The oil's been used up and global war has rendered progress & production stagnant. People scavenge junk to meet their needs but this junk is very much a finite resource. The regime either hoards what they scavenge or forbid the scavenging of certain goods, fearing it could upset the power balance. People who can actually manufacture or invent new tech might be persecuted cuz being able to build your own stuff instead of scavenging just disrupts the status quo. These types of stories usually have 1 of 2 MacGuffins: the main hero restarts some dangerous old-world tech or invents something powerful. Mortal Engines is technically scavengepunk and steampunk combined.

#dystopia#scavengepunk#oceanpunk#steampunk#punkpunk#desertpunk#mad max#anti establishment#post apocalyptic#oc#Mortal Engines#mortal engines#flapjack#tank girl#lori petty#tank girl comic#comics#mad max fury road#postapocalypse#scarcity#post scarcity#waterworld#one piece#cyberpunk#cyberpunk aesthetic#cyberpunk 2077#island#the misadventures of flapjack#dystopian films

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

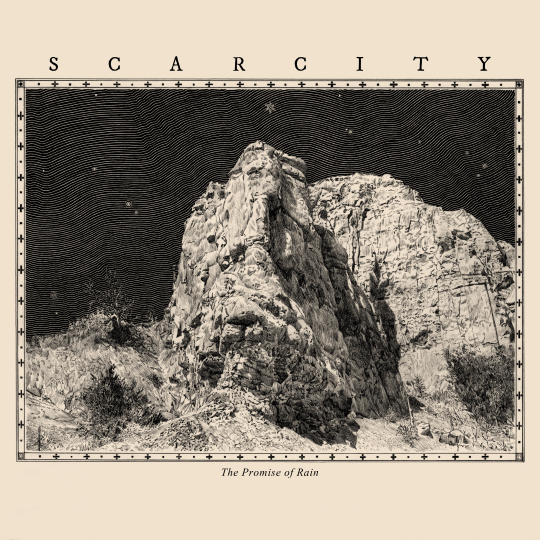

Cover artwork for the new Scarcity record, The Promise of Rain

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions (Historical Conflicts)

Historical Conflicts Worldbuilding Questions:

What is the biggest present conflict in this world, and what are its origins?

What are the major historical conflicts in the world and how did they shape present-day borders, beliefs, opinions and prejudices?

Who are the world’s peacemakers and what role do they play?

Who are the world’s worst agitators in stirring up conflict and why do they instigate it (e.g., territory disputes, resource competition, etc.)?

Where is the next conflict most likely to flare up and why?

Where is most peaceful, freest from conflict?

When past conflicts resolved to peaceful agreement, what prompted resolution?

When have war or other conflicts led to major cultural or social changes, and how?

Why do conflicts persist or change in this world?

Why do individuals or different groups in this world engage in conflict or remain pacifists?

❯ ❯ ❯ Read other writing masterposts in this series: Worldbuilding Questions for Deeper Settings

#writeblr#worldbuilding#fiction writing#writing advice#writing tips#novel writing#writing#conflict#territorial disputes#scarcity#fwq#historical conflict#present day conflict#peace agreement#armistice#now novel

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human needs can typically be satisfied either by means of relatively resource-efficient, non-commodified need satisfiers (for instance, public transit; food from a community kitchen), or by means of relatively scarce and resource-inefficient commodities (a privately owned car; a home-delivery meal). Under capitalism, commons and public goods are commodified and an artificial scarcity is imposed to ensure that these goods can be profitable when sold. In order to obtain the income to access these goods, people are obliged to compete with one another in the labour market to generate production for capital. Put differently, people are forced to produce many things that no one needs, in order to access things that everyone actually does need. Artificial scarcity is, in this way, the engine of perpetual growth. This dynamic explains why, despite the extraordinary productive capacity of capitalism – and despite extraordinarily high levels of aggregate resource use – much of the human population is nonetheless unable to meet basic needs. When it comes to meeting human needs, capitalism is deeply inefficient and wasteful.

How to pay for saving the world: Modern Monetary Theory for a degrowth transition

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

s'more

#digital art#mlp#The alternative six#The alternative Cmc#Mlp alternative au#Prismaclash#Scootuwu#Scarcity#Countess tourmaline coronet#Apple ale#Sweetie ray

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christian Paz at Vox:

The first few weeks of Donald Trump’s second presidency have put Democrats in a frustrating bind. He’s thrown so much at them (and at the nation), that they’re having serious trouble figuring out what to respond to — let alone how. He’s signed dozens of executive orders; attempted serious power grabs and overhauls of the government; and signed controversial legislation. And in the process, he’s further divided his opposition, as the Democrats undergo an identity crisis that ramped up after Kamala Harris’s loss.

Immigration policy is a prime example of this struggle: Long before Harris became their nominee, the party was debating just how much to adjust to both Trump’s anti-immigrant campaign promises and to the American public’s general shift away from openness to immigration. Now that he’s in office, Democrats aren’t really lined up to resist every one of the president’s anti-immigrant moves — and some are even backing some of his stances. The party is now divided into roughly three camps: those in the Senate and House willing to back Trump on certain tough-on-immigration measures, like the recently passed Laken Riley Act; those who see their constituents supporting some of his positions but are torn over how to vote; and those progressives who are committed to resisting his every move on immigration. Today’s public opinion is one main contributor for the divide: Americans are still largely in favor of more restrictionist immigration policy. Democratic losses in November are another contributor, particularly in areas with large immigrant or nonwhite populations. But lawmakers are also confronting longer-standing historical dynamics that have divided the working class and immigrants before. Newer and undocumented immigrants can appear to pose both economic competition and threats to existing senses of identity for immigrants who have already resided in the US, or to those who have assimilated and raised new generations. Combined with a resurgent Republican Party that has capitalized on some of these feelings, these facts might be complicating the Democratic response to Trump now.

Working class and immigrant divides aren’t new

On the campaign trail last year, Trump and various other Republican politicians repeated a specific line of reasoning when making a pitch to nonwhite voters: The “border invasion” that Joe Biden and Harris were supposedly responsible for was “crushing the jobs and wages” of Black, Latino, and union workers. Trump called it “economic warfare.” This line of reasoning — that immigrants are taking away economic opportunities from those already in the US — has historically been a source of tension for both native-born Americans, and older immigrants. Much of the economics behind this has been challenged by economists, but the politics are still effective. The main claim here is that an influx in cheaper low-skilled laborers not only pushes down the cost of goods but negatively impacts preexisting American workers by lowering their wages as well. The evidence for this actually happening, however, is thin: Immigrants also create demand, by buying new items and using new services, therefore creating more jobs. Still, the idea remains popular.

Even as far back as the civil rights era, this thinking created divisions among left-wing activist movements trying to secure better labor conditions and legal protections. Take the case of the most iconic figure of the Latino labor movement, César Chávez, himself of Mexican descent. As his movement to secure better conditions for farmworkers faced challenges from nonunion, immigrant workers who could help corporate bosses break or alleviate the pressures of labor strikes, his efforts on immigration took a more radical turn. Chávez’s United Farm Workers even launched an “Illegals Campaign” in the 1970s — an attempt to rally public opposition to immigration and get government officials to crack down on illegal crossings. The UFW even subsidized vigilante patrol efforts along the southern border to try to enforce immigration restrictions when they thought the government wasn’t doing enough, and Chávez publicly accused the federal agency in charge of the border and immigration at the time of abdicating their duty to arrest undocumented immigrants who crossed the border.

Of course, Chávez’s views were nuanced — and primarily rooted in the goal of creating and strengthening a union that could represent and advocate for farmworkers and laborers left out of the labor movements earlier in the 19th and 20th centuries. But they are great examples of the deep roots that economic and identity status threats have in complicating the views of working-class and nonwhite people in the not-too-distant past. This specific opinion has stuck around. Gallup polling since the early 1990s has found that for most of the last 30 years, Americans have tended to hold the opinion that immigration “mostly hurts” the economy by “driving wages down for many Americans.” And swings in immigration sentiment tend to align with how Americans feel about the state and health of the national economy: When economic opportunity feels scarce, as during the post-pandemic inflationary period, Americans tend to pull back from more generous feelings around both legal and illegal immigration.

Democrats also face the challenge of anti-immigrant immigrants

What makes this era of immigration politics perhaps a bit more complicated on top of those existing economic reasons is the added concerns over fairness and orderliness that many nonwhite Americans, and even immigrants from previous generations, feel. US Rep. Juan Vargas, a progressive Democrat who represents San Diego and the part of California that borders Mexico, told me that there’s a sense among some of his constituents that recent immigrants, both legal and not, are cutting the line. This feeling about newcomers not paying their dues is, again, a longstanding sentiment among immigrant groups across American history, but it appears updated for the post-pandemic era. While older immigrants feel they have worked hard and waited their turn, they feel newer ones have taken advantage of the asylum system, or gone through less of a struggle than they have. Vargas told me about a conversation he had with a constituent in his district who told him she disagrees with his stance on immigration policy, even though she once “came across illegally too” and lived in the US for 15 years without documentation. “I started talking to her, and she said, ‘You know, these new immigrants, they get everything. They get here and they get everything. We didn’t get anything, and so I think they should all be deported,’” Vargas said. “I said, ‘Oh, so, because you were given a chance, you don’t think other people should get that same chance?’ She goes, ‘Well, it’s different.’ … Really, in what way? How is it different? … And she didn’t have a very good answer.” Some immigration researchers describe this as part of a “law-and-order” mindset: folding border enforcement and immigration crackdowns with a renewed desire by the public for tough-on-crime policies in the post-pandemic era.

[...] These views help explain why there’s a vocal group of Democrats, including Latino Democrats, willing to work with Trump and Republicans specifically on immigration reforms that take a tough-on-crime approach, like the Laken Riley Act, which expedites deportation for undocumented immigrants charged with certain crimes. Some 46 House Democrats and 12 Senate Democrats ended up voting for the Laken Riley Act, including perhaps the most vocal pro-enforcement Latino Democrat, Sen. Ruben Gallego of Arizona. He argued that the bill represented where the Latino mainstream is now on immigration. “People are worried about border security, but they also want some sane pathway to immigration reform. That’s who I represent. I really represent the middle view of Arizona, which is largely working class and Latino,” Gallego said after the vote. Even some Democrats in solid blue areas of the country agree, to an extent. Democratic Rep. Sylvester Turner, who represents Houston and was an outspoken supporter of immigrant rights during Trump’s first presidency, told me that his constituents back tougher immigration policies, particularly when it comes to undocumented immigrants charged with violent crimes. He himself didn’t vote for the Laken Riley Act because he disagreed with the bill’s application to those merely charged or accused of a crime (as opposed to those convicted), but he said that he feels the public’s mandate to support other kinds of proposals.

[...] They’ll fight back against Trump when he tries to undue birthright citizenship, for example, but they won’t necessarily criticize the continued construction of a border wall with Mexico, or increased deportations. They’ll point out that deportation flights using military aircraft are mostly for show, while standard ICE-chartered planes can do the job for less. Many supported the bipartisan border bill that Biden tried to pass a little less than a year ago, for example, and would theoretically support it again.

[...] And they see room to defend DREAMers, DACA recipients, and those who have benefitted from asylum protections, like temporary protected status, because they see moral value in it, and political value as well: many of those categories of immigrants are popular with Republicans, and polling backs up these nuances.

Vox has a good story on how immigrants who have been here for a long time and those assimilated are opposed to a new arrival of immigrants, and that is hurting the Democratic Party.

#Immigration#Donald Trump#Democratic Party#César Chávez#Scarcity#United Farm Workers#Kamala Harris#2024 Presidential Election#2024 Elections#Laken Riley Act#Economy#US Citizenship#Immigration Reform#Border Security#Border Crisis#US/Mexico Border#Mass Deportations#DREAMers#DACA#TPS#Birthright Citizenship

7 notes

·

View notes