#Soviet project

Text

Love the contrast between the Americans’ “Apollo” and the Soviets’ “Sputnik.” You got the Americans naming their rocket after a Greek god trying to communicate the grandness and importance of this rocket. And you got the Soviets naming their rocket “fellow traveler.” Like a friend you go on an adventure with together. This rocket is our little friend lol

#i think its cute#they took the mars rover approach#humanizing the space craft making it cute making us (me) project emotions onto it#the soviets also used imagery of laika in propaganda a lot#which is pretty fucked up imo#but if i grew up in the soviet union that shit wouldve definetly worked on me lmao#the narrative of a heroic little dog going to space and being honored by the whole country#as cruely wrong as it is its very appealing#the soviets knew what they were doing man they didnt reveal how laika really died until like. the 2000s#bc they knew people really cared about that dog#they liked the narrative around her

81K notes

·

View notes

Text

tbh I should have realized that I wasn't an anarchist anymore in 2019 when I stopped answering "how will X work under socialism" by basically going "idk lol we'll find out when we get there" and started giving examples of how things work in Cuba and Vietnam today.

#i still have more quotes from Soviet Democracy i want to post when i get the time#i spent so long giving the US anticommunist narrative the benefit of the doubt#and thereby wasted so much time avoiding overly “tankie” sources#i really didn't want to think that they could have just blatantly lied and fabricated such horrific slander towards the communists#but i should have realized that of course they could#if they had no qualms about murdering children in korea and vietnam#why would they have any qualms about projecting their own brutality onto their enemies?

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

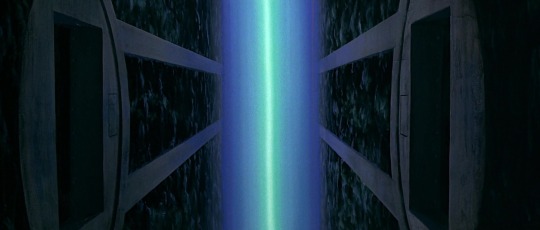

"A view of the Soyuz 19 spacecraft as seen from the Apollo CSM flying the Apollo Soyuz Test Project.'

Date: July 19, 1975

NASA ID: AST-1-056

#Soyuz 19#Soyuz 7K-TM#No.75#Soyuz-U#Rocket#Soviet Space Program#Apollo–Soyuz#Apollo Soyuz Test Project#ASTP#CSM-111#NASA#Apollo Program#Apollo Applications Program#July#1975#my post

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

cant believe I just saw someone very strongly imply that it was a bad thing Finland wasn't absorbed into the Soviet Union

#these people are a joke#theyre all about liberation and decolonisation when it comes to the west#but then they talk about “invading soviet land” like russia in its many forms isnt one of the longest imperial projects in modern history#also whats up with tankies being super into cutesy anime girls

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

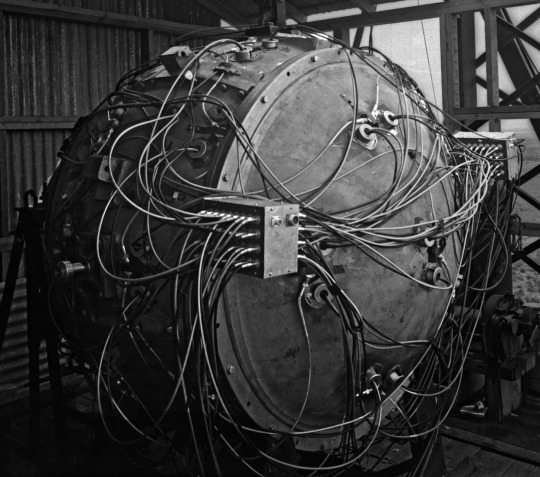

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

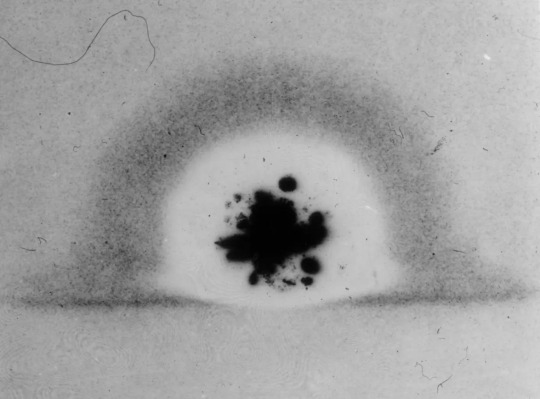

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970, Joseph Sargent)

Also known as: The Forbin Project

3/21/24

#Colossus: The Forbin Project#The Forbin Project#Eric Braeden#Susan Clark#Gordon Pinsent#William Schallert#James Hong#Georg Stanford Brown#Willard Sage#Alex Rodine#70s#science fiction#thriller#satire#computers#artificial intelligence#world domination#tech#cold war#Soviet Union#arms race#scientists#tyranny#dystopia#suspense#nuclear#espionage#surveillance#political

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gene Hackman as Valery Michailov talking to Mario in Andrey's Siberian hideout, GONCHAROV (1973) dir. Martin Scorsese

#goncharov#martin scorsese#gene hackman#valery michailov#i was gonna gif the whole scene where he plans to kill goncharov for sleeping with katya but mario talks him out of it#(actually i think that valery only agreed because he has a soft spot for mario but that was maybe just me projecting)#but i have this assignment for school so i don't have the time#maybe later#unreality tw#(ooc:) i wanted to photoshop michael corleone into the fortress of solitude scene but my photoshop skills are not that good#so it looks fake af#but i've already photoshopped the soviet pin on lex luthor so i'll share that#my gifs

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feeling discouraged, so here's a short, unfinished Godos piece that will never be realised. Nikolai's attempting (read: failing) to write his first draft of a play (an adaptation of Dead Souls, Part 2). Fyodor was going to cheer him up and inspire him, somehow, but I don't have any clue how, so this is all I could get out of that idea. (I do at least like how it turned out, though, unfinished as it is.)

---

The words on the page taunted Nikolai like so many Sufi dervishes. They blurred, swirled into characters half-formed, who jumped and jeered just out of Nikolai’s sight. ‘Find us,’ they seemed to say. ‘Come and see our beautiful lives! And then depict us, reveal us to everyone, that we may truly exist.’ They beckoned him to find them, invited him to view their marvelous exploits, to laugh along with their absurd adventures—and then just as he reached to meet them, they slipped away, laughing. Unendingly they tortured him with scenes just beyond grasp, a perfect story hidden in the periphery of a dense fog.

Nikolai groaned, leaned back, and pressed his palms against his eyes. It was a perfect picture of agony, well-practiced and endlessly rehearsed. ‘Yet all the acting in the world won’t save a lacking script,’ he thought. ‘Ah, why can’t you just write yourselves? Hop along, I’ll even guide the quill, so long as you do something, anything, oh please…’ His entreaties, of course, prompted naught but more formless tittering. Nikolai sighed, and contemplated how effective bashing his scull against the door-jam would be at shaking something loose.

“Is something the matter?” an irritatingly calm Fyodor asked from behind him. Nikolai swung around in his chair, resting his arms on the back, and stared pointedly at his relaxed friend who lounged so serenely on the green recliner, a book nestled under his folded palms. The question itself was preemptive, a set-up, a frivolous first line of a three-line script which always arrived at the same conclusion. Nikolai recognised the offer for friendly—and perhaps even needed—advice, but took it no less bitterly. He smiled mirthlessly. Nevertheless, he played his part.

“Whatever gave you that impression? Was it the willful suicide of the last of my creative expression? Or perhaps you hear them laughing too?”

“Your characters won’t work with you?” (Here, the second phrase, to be replied with…)

“Oh, far beyond that. They won’t speak to me at all! I’m being shunned.”

“I see.” Fyodor concluded and stood, pulling the curtain on their impromptu play. Nikolai watched him go, mildly curious which remedy Fyodor would prescribe this time. “I need to visit the theatre,” he said finally. “Would you like to join me?”

Nikolai laughed flatly. “For what? The stage doesn’t—and I say this from great experience—do anything for one’s imagination. If anything, it’s worse, because you see everything that has been and none of what could be! Can you imagine that? I know, I know, you’re ‘not that way artistically inclined,’ but imagine for a moment that the sentences of your computer codes were jumping and jaunting about in front of your very eyes, and so to fix it, you decided to stare at someone else's pages. Well? Would that help you very much?”

“Most likely it wouldn’t.” Fyodor smiled. “But we won’t be going to the stage. I need to stop by the costuming department. Misha talked one of the women there into parting with an unused costume design for Verenka, but couldn’t pick it up himself.”

“And you just so happen to be free?”

“No,” Fyodor said, a bit dejected. “But I couldn’t stand to stare at my colleagues’ ‘pages’. As you say, it won’t do any good.” He sighed wearily. “Some fresh air and new scenery, tea, something else to think about… I need them greatly. And some company would be nice, too.”

Nikolai stood without ceremony (a shame, yes, but recall his lack of inspiration and forgive him), stretched, and said flatly, “Well then, what are we waiting for?”

---

As it turned out, Nikolai was quite quick to regret those words. A lovely stroll down the uncharacteristically sun-touched streets of St. Petersburg wound down into a bustling cafe.

---

Surprisingly, all went well at the theatre. The lady was quite nice, expressing her condolences and well-wishes for the ‘poor young woman’, and waved them on their way. Pattern safely secured, the two stopped by the next-door cafe, ‘The Stray Dog’, (home to aspiring and established artists alike), for a spot of tea. And thence all collapsed.

#writing#bsd#bsd fyodor#bsd nikolai#godos#fyolai#the projection is strong with this one#I wanted to try a story more from Nikolai's perspective#adding his way of viewing the world into the prose#because usually I do a more third-person omniscient style and Дом в котором inspired me#the Fyodor really wasn't Fyodoring in this one though...#by the way: 'The Stray Dog' isn't just a BSD reference#it's an actual cafe that was frequented by a lot of prominent silver age Soviet artists#and still exists today I believe after having been shut down for a while#it also happens to share a building with Mikhailovsky theatre. which is near-ish to the apartment they're in right now#(their apartment being on Grazhdanskaya street)#also to ramble a bit about Fyodor and Nikolai's living situation#they share a one-room apartment. which is why Fyodor was reading in the same room#Fyodor works on his laptop in the kitchen but prefers to read in the bedroom#Nikolai's writing desk is also in the bed/living room so it's often that he's writing/rehearsing while Fyodor's reading#which personally sounds like a living hell but they both grew up sharing rooms with siblings so ig they're already used to it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

i lowkey am obsessed w perfume even tho i dont wear it that much i just love to collect it. therefore i try to convince my bf it's as cool as i think it is by yapping . my most recent attempt is by combining perfume w our joint obsession (soviet art history) via red moscow

#a poem i worked with for a project a while ago was abt red moscow and its mockery re:parashas#therefore. this counts as something i need beyond my own interest#from me#did u all know about my soviet art history obsession. or is that new#it's been a few years haha i would explain more but it's very traceable to me irl bc i've done too much publicly with it#but like mutuals if u want anything hmu

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

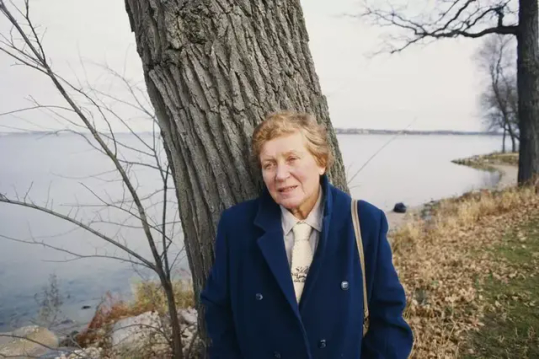

November 22: On this day in 2011, Svetlana Alliluyeva died at the age of 85.

She was born on the 28th of February 1926. Her father was Joseph Stalin, and her mother was Nadezhda Alliluyeva, Stalin's second wife (after Kato Svanidze). She has an older brother named Vasily, and an older half-brother from Stalin's first marriage, named Yakov. Yakov was neglected by Stalin when he was captured by the Nazi soldiers during WWII.

Everything went downhill for Stalin's family life in 1932. Around the early morning of November 9, Nadezhda shot herself with a pistol given to her by her brother, Pavel Alliluyev. This was because she and Stalin had a fight during a party in the Voroshilovs' residence. She was humiliated by Stalin at the table. He called out to her, "Hey you! Why are you not drinking? Have a drink!" to which she responded, "My name is not hey!" and exited. The last person to see her and walk with her was Polina Zhemchuzhina, Vyacheslav Molotov's wife.

Suicide was considered an act of treason in the Soviet Union, so her cause of death was faked. Everyone was told that Nadezhda died of appendicitis. Everyone was fooled, even Svetlana was told about this up until she learned the truth when she was a teenager.

Svetlana was a daddy's girl up until that moment. She attended his funeral in 1953, however.

In 1967, she decided to defect to the United States of America, as well as living a life there. Take note that this was during the Cold War, so the tensions between the USA and the USSR were high.

She lived in the USA as Lana Peters, and she was survived by her daughter Olga Peters, through her marriage with Wesley Peters, as well as her children in the Soviet Union from her previous marriages.

She has written books; her memoirs are entitled "Twenty Letters to a Friend," and "Only One Year."

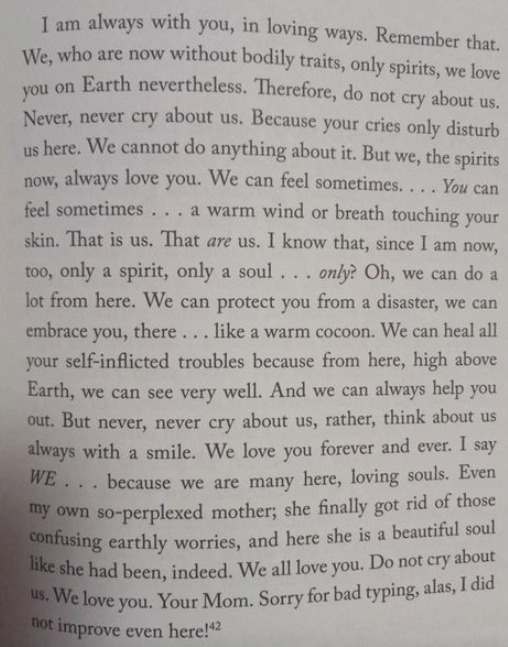

This is Svetlana's last letter to her daughter, Olga:

#svetlana alliluyeva#soviet union#ussr#soviet history#history#stalin era#i have waited for so long to post about her#finishing sullivan's stalin's daughter made me cry bc svetlana feels like a friend already#as for nadya i made a literary piece in her memory for a project and i hope i am able to share it with you all!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preview of what I've been working on in ceramics class 🚀🌟

#just one of several projects i've been doing but this is by far my favorite work#photo journal#vesti arts#ceramics#WIP#space exploration#cosmonauts#voskhod 2#soviet space program#ussr

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

also i need to make a research project this year and i kinda don't know what topic to choose but i think im gonna explore "arctic exploration done by russia before 1917" or something like that. i would love to make a project about british arctic exploration BUT it would not be that relevant i think

#bernie's existence#bernie's high school drama#i dont want to do arctic in Soviet time because I HATE everything Soviet#when i think about most Soviet things i physically want to vomit#(dont tell this to my best friend#she would eat me alive for that)#i hateee making projects because im lazy#i hate doing anything at all to be honest

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturn Apollo Program

"This artist's concept depicts the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), the first international docking of the U.S.'s Apollo spacecraft and the U.S.S.R.'s Soyuz spacecraft in space. The objective of the ASTP mission was to provide the basis for a standardized international system for docking of marned spacecraft. The Soyuz spacecraft, with Cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov aboard, was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome near Tyuratam in the Kazakh, Soviet Socialist Republic, at 8:20 a.m. (EDT) on July 15, 1975. The Apollo spacecraft, with Astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Donald Slayton aboard, was launched from Launch Complex 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida, at 3:50 p.m. (EDT) on July 15, 1975. The Primary objectives of the ASTP were achieved. They performed spacecraft rendezvous, docking and undocking, conducted intervehicular crew transfer, and demonstrated the interaction of U.S. and U.S.S.R. control centers and spacecraft crews. The mission marked the last use of a Saturn launch vehicle. The Marshall Space Flight Center was responsible for development and sustaining engineering of the Saturn IB launch vehicle during the mission."

Date: 1974

NASA ID: 9401759

#Apollo–Soyuz#Apollo Soyuz Test Project#ASTP#Apollo CSM Block II#CSM-111#Docking Module#Rocket#Apollo Program#Apollo Application Program#Soyuz 19#Soyuz 7K-TM#No.75#Soyuz-U#Soviet Space Program#artwork#July#1975#my post

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of my favourite quotes from the article i'm trying to get published is from a ukrainian who lived through the german occupation: he's talking about the local collaborator who administered their village during that time and describes him as "a man devoid of principles, but also of any particular wickedness." because like. that just sums it up a lot of the time, doesn't it?

#history#it's our old friend the banality of evil#as someone who studies totalitarianism it's my greatest shame that i haven't actually read eichmann in jerusalem but i'll get around to it#quote is from the harvard project on the soviet social system vol. 7 case 81 sequence 3-4#that website is such a nightmare to navigate but the transcripts are super interesting#even though they're from the 50s before there were really any oral history best practices#second favourite quote is from this ossetian talking about how there were lots of ossetians in government (there weren't)#and he's like “i say so not because i'm an ossetian but because it's true 😊”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

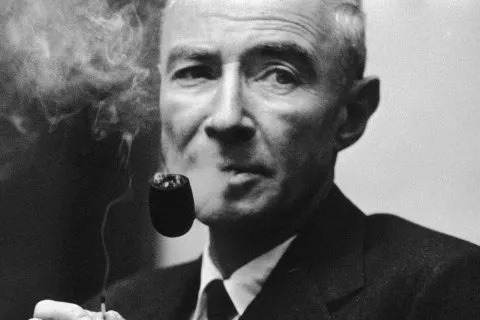

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday 1 September Mixtape 363 “Forest Waterfall”

2023-09-01

Morning Retro Space Synth Downtempo Electronica

Wednesdays, Fridays & Sundays.

Support the artists and labels.

Don't forget to tip so future shows can bloom.

Binaural Space-Entering the Forest 00:32

Kosmischer Läufer-Der Hörraum 01:00

THE SOVIET SPACE DOG PROJECT-Sergey Korolev's Sleepless Night 02:20

Paul Ellis-The Space Elevator´s Last Ride 09:32

The New Honey Shade-Time Reversal Through The Crystal 12:00

Concretism-The Sum Of The Angles 15:08

Andrew Hartshorn-A Voyage To Beta Cancri 18:56

Pabellón Sintético-Farnsworth house 22:08

Panamint Manse-Turquoise 27:28

Majeure-True Polar Wander 30:33

Korb-Ancient Technology 34:19

Julien Rachedi-La grotte de l'Astyanax 36:23

John Louis Kluck-Virtuality 38:46

Donny Benét-Waterfall (Love Scene) 42:30

#Binaural Space#Kosmischer Läufer#THE SOVIET SPACE DOG PROJECT#Heimat Der Katastrophe#Paul Ellis#Cyclical Dreams#The New Honey Shade#Handstitched*#Concretism#Castles in Space Subscription Library#Castles In Space#Andrew Hartshorn#Pabellón Sintético#Panamint Manse#Woodford Halse#Majeure#Korb#DREAMLORD RECORDINGS#Julien Rachedi#ERR REC#John Louis Kluck#Kahvi Collective#Donny Benét#Remote Control

3 notes

·

View notes