#The Duke of York and his second son were killed; and his heir was only 18; the King would soon be reclaimed from their grasp

Note

how do you think the Lancasters stood the best chance at winning the war?

Imo, if they'd won at Mortimer's Cross or Towton, the Yorkists would be finished.

A lot of the WotR depended on military victories, tbh. We tend to get distracted by fancy discussions like "Who had the best claim?"* or Propaganda Roulette 101, but the fact remains that it was ultimately military victories that sealed the deal and got rid of opposition**. Everything else was pretty wrapping on top of the already-won or to-be-won prize.

*The most useless debate of all

**The exception was Richard III's usurpation but that was a fairly unconventional and entirely unexpected usurpation, and in any case it was a military defeat that ended his reign.

#ask#wars of the roses#Remember that the Yorkists were on the brink of total defeat by the end of 1460#The Duke of York and his second son were killed; and his heir was only 18; the King would soon be reclaimed from their grasp#If they'd lost in 1461 their cause would most likely be over#A fairly analogous example would be the Battle of Bosworth - if Richard III had won Henry Tudor's cause would be finished#(and he'd probably be dead)#If the Lancastrians had seized London they'd have a huge advantage but might also encounter some difficulties#including a potential siege and hostility from the aldermen and public. But a military victory would seal the deal#Also I think I've mentioned in some tags before but imo it's clear that the Lancastrians stood a monumentally better chance at#consolidating their power/support/reputation if they won in 1461 rather than 1471#A 1471 military victory would result in victory but would also bring with it a whole host of other problems in terms of consolidation#(Among others: the inevitable head-on national clash between Yorkist and Lancastrian lords in terms of forfeited and restored estates#which had been postponed by Warwick but would undoubtedly take center stage once the royal family was properly established#and would almost definitely result in the eruption of widespread rivalries and resentment from the affected parties;#foreign and domestic policy with regards to the promised war with Burgundy which was very unpopular with the English patriciate; etc)#(That's not even getting into whether Warwick would survive or not and the equally complicated possibilities in either scenario#or George of Clarence: whether their victory would be before or after he switched sides and what that would mean for him)#There's also the obvious fact that Henry VI would still ultimately be King - and that can take VERY different routes depending#on the wider situation#In a completely alternate scenario if they had established themselves when Edward IV was still in exile he would be out of reach#which would over-complicate matters even further#(I'd be personally curious to know if they took any action against royal claims through the female line considering this was a HUGE#aspect of their gendered propaganda in the 1460s to try and delegitimize the Yorkist claim...Henry IV gave them an obvious precedent)#a 1471 victor would also be devastating on a personal level for everyone involved considering Henry's imprisonment and#Margaret and Edward's almost decade-long exile before it#It would be significantly more devastating for Edward IV's widow and four frighteningly young children - especially considering#that unlike Margaret or Anne Neville they lacked the active/direct connection of powerful foreign or national relatives#All in all - It's difficult to say but it's clear that a path forward in 1471 would be tremendously hard#A victory in 1461 would not only forever end the Yorkist challenge but would also ensure a far smoother aftermath for the Lancasters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabel of Castile, First Duchess of York

Isabel was the third of four children of King Pedro I, also known as Pedro the Cruel, who ruled the Crown of Castile from 1350. Her mother was the vivacious and intelligent Maria de Padilla, often described as Pedro's mistress. In 1361, when Isabel was only six, her mother died. The following year, Pedro declared that he and Maria had been lawfully married before he was forced to espouse his estranged French wife, Blanche of Bourbon, who was by then also dead, some said murdered by her husband. His claim of an earlier marriage was subsequently endorsed by the Cortes, thus legitimising Pedro's children by Maria. Pedro was killed by his illegitimate half-brother and deadly enemy Enrique of Trastámara in March 1369. Trastámara became King Enrique II of Castile.

Isabel accompanied her elder sister Constanza to England, and married Edmund of Langley, son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault, in 1472 at Wallingford, as part of a dynastic alliance in furtherance of the Plantagenet claim to the crown of Castile. Isabel was only 16 or 17 to Edmund’s 31, and brought him no lands or income or even the promise of such because her sister Constanza – who married Edmund’s elder brother John of Gaunt as his second wife – was their father’s heir. John and Constanza spent many years trying unsuccessfully to claim her late father’s throne from her illegitimate half-uncle Enrique of Trastamara, while Edmund and Isabel were required to give up any claims to the kingdom of Castile and were not compensated.

As a result of her marriage, Isabel became the first of a total of eleven women who became Duchess of York. She was appointed a Lady of the Garter in 1379. In their twenty years of marriage, the Duke and Duchess of York had three children:

Edward of Norwich, Duke of York

Constance

Richard of Conisburgh, Earl of Cambridge

Contemporary sources suggest that Edmund and Isabel were an ill-matched pair and their relationship was a rocky one, with Isabel accused of having an affair with John Holland, Duke of Exeter and half-brother to Richard II. The affair is believed to have started as early as 1374 and likely continued for a decade. As a result of her indiscretions, Isabel left behind a tarnished reputation. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham considered her to have somewhat loose morals.

John Holland has also been suggested as the real father of Isabel’s youngest son, Richard of Conisburgh, who was the grandfather of Edward IV and Richard III. The fact that his father Edmund of Langley and brother Edward, both, left him out of their wills has fuelled this theory. However, leaving a son out of your will was not entirely unusual, and Richard had died when his brother made his will.

Isabel of Castile died in December 1392 at the age of about 37 and was buried at Langley Priory in Hertfordshire. In her will, Isabel left items and gifts of money to close relatives by blood or marriage, and to numerous servants of hers, men and women. Isabel referred to Edmund of Langley as her "very honoured lord and husband of York", and left him all her horses, all her beds including the cushions, bedspreads, canopies and everything else that went with them, her best brooch, her best gold cup, and her "large primer". Isabel named King Richard II as her heir, requesting him to grant her younger son, Richard, an annuity of 500 marks. Isabel left nothing at all to her older sister Constanza, duchess of Lancaster, and failed even to mention her. Isabel doesn't forget John Holland in her will, at this time married to Elizabeth of Lancaster, John of Gaunt's daughter.

About 11 months later her widower married Joan Holland, niece of Isabel's supposed lover, John Holland. In another bizarre family twist, it was Joan’s brother, Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent, who had an affair – and an illegitimate daughter – with Constance of York, the daughter of Edmund and Isabel. In Edmund’s own will of 1400 he requested burial ‘near my beloved Isabele, formerly my consort.’ Despite Isabel of Castile's bad reputation and supposedly having been involved in a court scandal that humiliated her husband, Edmund seems to have felt great affection for her as demonstrated by his willingness to rest eternally with Isabel and not with his second wife.

Source:

#Isabel of Castile#Edmund of Langley#Duchess of York#Duke of York#women in history#english history#spanish history

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m currently listening to Anne Boleyn: 500 Years of Lies by Hayley Nolan on Audible, and I’m trying hard to like it because it has really good information discrediting some of the beliefs surrounding Anne; but I have to admit that it’s grating me to hear the author stating that the Tudors were “usurpers” and that they were preventing a “more rightful heir” from gaining the throne. I almost screamed in frustration when she blamed H8’s sociopathy on Margaret Beaufort and especially Henry VII, using that one source claiming that H7 once tried to kill H8 in a fit of rage as firm evidence of a miserable childhood (ignoring all evidence stating otherwise); because of course having an overprotective parent (which is all H7 was) is going to cause you to grow up with no conscience. Also is it true that H8 was given absolutely no training in monarchy and came to the throne completely uneducated in that regard, I find that incredibly hard to believe regarding H7.

Hello! First of all, there's so much to unpack here. I think we have to go step by step. A big disclaimer is that I have not read Nolan’s book, so I’m only considering what you told me here. Secondly, I will not be addressing any claims against Margaret Beaufort because, frankly, what did that woman ever do be accused of that — the same Margaret Beaufort who 'of marvayllous gentyleness she was unto all folks' , and who 'unkind she would be unto no creature'? Are we talking about the same Margaret? We know one of her old servants, Henry Parker, was talking about his 'godly mistress the Lady Margaret’ to her great-granddaughter Mary well into the mid-1500s, and we know the time Margaret reprimanded a dean in Christ's College for beating one of his pupils (crying ‘gently, gently!’). I don’t see how she could be considered the origin of anyone’s sociopathy, but I also dislike the term — antisocial personality disorder is a medical condition and I doubt we could ever diagnose Henry VIII with that or anyone else who died five hundred years ago for that matter. The rest of my answer is under the cut!

Well, now for the rest: I wouldn't say all of the Tudors were usurpers. Henry VII very much was one, as he did unseat England's king at the time of his invasion though that hardly makes him worse than other 15th-century English kings (as I've talked here, Henry IV was a usurper, Edward IV was a usurper, Richard III was a usurper — hell, William the Conqueror had been a usurper four centuries earlier). None of Henry VII's successors would have been usurpers, though (unless we should say every English king after William the Conqueror was a usurper, I guess?). Especially if you consider that they were also the natural successors of the Yorkist line via their descent from Edward IV's eldest daughter and heir, Elizabeth of York. I have no idea who Nolan could be referring to as the 'more rightful heir': the de la Poles, the descendants of Edward IV's sister? The Poles, the descendants of Edward IV's brother? Even if you go by Yorkist descent alone (which not everyone in England regarded as the most legitimate), who would have had a better claim in England than Henry VIII, the son of Edward IV's surviving heir and the son of England's most recent conqueror, Henry VII?

As for Henry VIII's miserable childhood, I don’t think there is evidence of that. We know Henry was well-educated; his father made sure to appoint tutors who taught him in the arts, classics, music, dancing, discourse, courtiership and theological disputation. We also know that Henry VII was personally involved with his sons' education, whilst his wife Elizabeth was involved with their daughters'. It is true that Henry VIII was not initially prepared for kingship but once his brother Arthur had died his father began preparing him for his future office. In July 1504 Prince Henry officially moved into his father's household where it seems Henry VII tutored him personally in some subjects. In August of that same year, the Duke of Estrada, a Spanish ambassador, wrote that 'Formerly the King did not like to take the Prince of Wales with him, in order not to interrupt his studies [...] But it is not only from love that the King takes the Prince with him; he wishes to improve him. Certainly there could be no better school in the world than the society of such a father as Henry VII. He is so wise and so attentive to everything; nothing escapes his attention'. So you can see that Henry VIII was assisted and had at least five years to prepare for the office of kingship, which is more than Henry VII himself ever had.

Lastly, it's clear that Henry VII loved his son. The same ambassador, Duke Estrada, also said in his dispatch: 'It is quite wonderful how much the King likes the Prince of Wales'. There are several entries in Henry VII's privy purse accounts describing items and stuff he bought to his younger son, always referring to him as 'My Lord Harry'. For all we know, Henry VII saw much more of his second son than he ever saw of Prince Arthur who lived in Ludlow, away from court. There is that anecdote about the time Henry VII knighted Prince Henry when he was only three years old: during the ceremony the king picked up his young son and placed him on a table for all to see — a gesture possibly made out of love, fondness, and/or delight in his youngest, though we can only speculate. Henry VII seems to have been determined not to expose his remaining son to danger in the same way that Arthur had been, and some of his more overprotective measures (like the setting of the Prince's apartments, accessible only by way of his own) can be understood as born out of paternal concern, all things considered. The rumours that the Calais garrison was not willing to crown Prince Henry in the event of his death were certainly of great concern to Henry VII.

To sum up, there is evidence that Henry VII did love and care for his son Henry. No doubt their relationship may have been strained at times thanks to Henry VII’s overprotective measures, but it’s also true the king let his son shine on many occasions in his place, denoting both affection and trust. Henry Pole's claim, made in 1538, that the king ‘had no affection nor fancy unto’ his heir should be seen in its proper context: one in which his brother, Reginal Pole, was involved in an ideological campaign against Henry VIII — the message was that not even Henry VIII's own father had loved him. I cannot say if Henry Pole actually said those words (anyone with more expertise please feel free to correct me) or if those were brought up as charges against him, but they do belong in the realm of (real or invented) seditious language. I tried to find the claim that Henry VII once tried to kill his son over a fit of rage in the dispatches sent by Fuensalida (allegedly the one who made that claim according to Hutchinson’s Young Henry), but the only thing I could find was something akin to court gossip, saying Henry VII treated everyone badly for a time (including his son) and spent three hours every night with his eyes closed but not sleeping...... which is??

(Here I should comment that Fuensalida not only disliked Henry VII but he was also several times denied access to the king and the Prince of Wales on account of what the English most likely considered to be his rude behaviour. He is also the one who said the Prince was kept closeted away like a girl, not realising that he was specifically denied access to the Prince — perhaps not without reason, seeing how Ferdinand had instructed him in winning the Prince over to their cause. Fuensalida was, of course, only serving the interests of his king, but his skills in diplomacy are somewhat unusual. Even Catherine of Aragon would later complain about Fuensalida’s behaviour).

In any case, I cannot speak about Nolan’s book as I have not read it but I wouldn’t be surprised if the author makes some unsubstantiated claims, considering the book was not peer-reviewed. That’s exactly how many pop history books work and why it’s hard to hold them to high standards. I hope this answer is not a big rambling mess, but really there were so many things to address, I didn’t even know where to begin. Thanks for the ask, anon! 🌹x

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every rebellions, plots, conspiracies, and seditions against Henry VII, by chronological order.

1485: Henry VII becomes king after his victory at Bosworth. Two hundred men from the Calais garrison flee to Flanders.

1486: attempted murder against Henry VII at York. The Stafford brothers rebel and take Worcester, while viscount Lovell rebels in Richmondshire. Eventually, the Stafford brothers are captured and one executed, while Lovell flees in Flanders to the court of Margaret of York, dowager duchess of Burgundy.

1487: Lambert Simmel's rebellion. A Yorkist conspiracy proclaims a commoner Lambert Simmel to be the escaped earl of Warwick from the Tower (Edward Plantagenet, nephew of Richard III and Edward IV). He is proclaimed 'Edward V' in Dublin by the Anglo-Irish aristocracy and joined by 2,000 german mercenaries led by viscount Lovell and his cousin John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln. With a mixed german-irish force, Landing in Lancashire enjoyed limited defection in northern England (mainly lord Bolton of Scrope, lord Bolton of Masham, and Sir Thomas Broughton). Their ~8,000 force is beaten at Stoke by a Tudor army led by the king and the earl of Oxford. Death of Lincoln and Lovell, Simmel is spared. Before the rebellion, Henry VII preemptively jails some key Yorkists, including his mother-in-law Elizabeth Woodville and his brother-in-law the Marquess of Dorset.

1489: Anti-tax rebellion in Yorkshire. The rebels led by Sir John Egremont murder the earl of Northumberland and take York before dissolving at the arrival of the royal army. Egremont flees to the court of Margaret of York.

1491: At Cork, a man proclaims that he is Richard of Shrewsbury, the disappeared second son of Edward IV. His true identity remains unknown. ‘Richard’ receives immediate support nonetheless from some Yorkists such as John Taylor, a former supporter of the duke of Clarence (Edward IV's brother).

1492: 'Richard' land in France, where he was welcomed by Charles VIII, who is at war with England. Henry VII retaliate by an invasion from Calais and sign the treaty of Etaples. Charles VIII agreed to stop supporting English rebels and give the Tudor king a pension.

1492: The peace treaty is unpopular in England, and 'Richard' is welcomed in Flanders by Margaret of York and Maximilian of Habsburg, ruler of the Burgundian estates. Maximilian is angered by the separate peace Henry VII made without consulting him. He recognizes him as the rightful king of England. The news of Richard's survival and reappearance began to be known in England and test the allegiance of Henry VII's subjects.

1493: Henry VII retaliate by imposing a blockade on the Netherlands. Counter-measures ensued, leading to an embargo from both parties, which lead to riots in London. 'Richard' assists at Maximilian's coronation as Holy Roman emperor and is promised support for his restoration. Scotland and Denmark recognize his legitimacy.

1494: Maurice Fitzgerald, earl of Desmond, revolts against the Tudors and leads a rebellion in Munster.

1495: an essential group of plotters is arrested. It consists of the king's own Chamberlain and the most powerful knight in England, Sir William Stanley (he was mighty in Cheshire and had £10,000 of reserve in cash at his castle of Holt). Lord Fitzwater (important Calais official and landowner in East-Anglia), Sir Simon Mountford (significant landowner in Warwickshire), William D'Aubeney, Thomas Cressener, Thomas Astwode, and Robert Ratcliff. They were mainly former supporters of Edward IV, and some had connections with duchess Cecily's household. Sir Robert Clifford, one of the plotters, betrayed the entire plot and was pardoned. Others were fined or executed, like Stanley.

'Richard' prepares to invade England by East-Anglia with a force of exiled and Flemish mercenaries. Stormy winds scattered his forces and made him land in Kent, and his force of 300 soldiers is beaten by the Earl of Oxford at his arrival at Deal. He flees and lands with the remainder of his troops in Ireland, where the revolted earl of Desmond joins him. Their combined forces fail to take Waterford. After this defeat, 'Richard' and his supporters arrive in Scotland.

1496: restoration of trade between The Netherlands and England, as Henry VII join the Holy League against France. The earl of Desmond also makes his peace with Henry VII. A Scottish army invades England as 'Richard' promised to give Berwick £50,000 to the Scottish king James IV. Little result ensues except for some small raidings.

1497: 'Richard' marries a cousin of the Scottish king, Catherine Gordon. As the king of Scotland makes a truce with England, he tries to land once again in Ireland with Sir James Ormond's support. However, Ormond's murder led to the failure of the uprising, and 'Richard' flee from Ireland with three ships.

Taxation for the Scottish war led to the Cornish rising. A blacksmith, Michael Joseph, leads the revolt with lord Audley and brings many gentrymen from Cornwall to rebellion. The rebellion extends to neighboring counties as the rebel take Exeter and march to London, virtually unopposed. A 25,000 royal army face some ~15,000 rebels at Blackheath, near London, and triumph. Once again, the earl of Oxford's vanguard is instrumental for the victory against the rebel.

'Richard' finally land in Cornwall, hoping to bolster his support with the Cornish's discontent. An uprising in his favor occurs (second Cornish rebellion), and his 8,000 men fail to take Exeter. His attempted fleeing after the encirclement of his forces by the Tudors led to his capture at Bealieu abbey.

'Richard' confess he is an impostor and a Flemish by the name of Perkin Warbeck. He and his wife are welcomed at court.

1498: 'Richard' tries to escape court and is captured and jailed in the Tower of London.

1499: A Cambridge scholar by the name of Ralph Wiford dreamt that he would become king if he claimed he was the earl of Warwick. His uprising in East Anglia failed, and he is executed.

Edmund de la Pole, earl of Suffolk and brother of the Earl of Lincoln (thus nephew of Richard III), leave England for Flanders after killing a commoner in London before agreeing to come back.

The French hand over many supporters of 'Richard' in France, including John Taylor. Many are executed, but Taylor's life is spared.

An attempted escape made by 'Richard' and his cousin Edward, earl of Warwick, fail, and they are both executed.

1500-1503: Henry VII lost his wife in childbirth and two sons (Arthur and Edmund). Dynastic fragility ensue as Henry VII have only one surviving male heir.

1501: Edmond de la Pole and his brother Richard flee for the Flanders. Henry VII promptly jail their brother, William, with Sir James Tyrell and Lor William Courtenay. Royal officials are sent in East Anglia to monitor the de la Pole affinity. Sir James Tyrell 'confess' before his death the murder of the Princes in the Tower for Richard III.

1504: 'treasonous' talks between Calais officials. They argue about who would be the successor for a declining Henry VII and hesitate between the duke of Buckingham and the Earl of Suffolk, omitting Henry VII's children.

1506: The Habsburgs deliver Edmund de la Pole to Henry VII, who jail him at the Tower of London. In exchange, Henry VII loan them immense sums of cash, such as £108,000 in April.

1509: Henry VII dies, leaving the crown to his adult heir, Henry VIII.

I might have missed some small, aborted plot, but there it is.

With this chronology, it's evident that the War of the Roses (or, more accurately, the war of the succession crisis of 1483) didn't end at Bosworth. Henry VII could have been overthrown in 1487 or the late 1490s. There is also a clear distinction between the rebellions of the 1480s and those of the 1490s. The plot following HenryVII's advent is mainly coming from RichardIII's basis of power. It's his men (Lincoln, Lovell, many northerners), his bases of support (the North and Ireland) who try to overthrow the first Tudor.

The plots of ''Perkin Warbeck'' known in historiography, were perilous for Henry VII. Most of his dynastical legitimacy comes from his marriage to Elizabeth of York. A true surviving son of Edward IV would nullify this and put into question the support of every former servant of the late Yorkist king. Hence, Henry VII tried to depict 'Richard' as an impostor and to demonstrate that the Princes of the Tower were dead. Still, he couldn't convince everyone and had to resort to force and the systematic use of a spy network.

Some of those plots might have been exaggerated. The 1504 Calais plot was undoubtedly not a carefully crafted conspiracy but more a manifestation of Henry VII's difficult succession. This chronology also doesn't show the dubious role that many magnates had during this period of unrest. The loyalty of Lord Abergavenny (dominant in Kent) was put into question, as was one of the earls of Derby in the 1490s and Lord Daubeney. Henry VII didn't have many magnates on whom he could truly count.

As you can see, Henry VII was never wholly free from dynastic uncertainty. At his death, Richard de la Pole was still free to push his claim if his brother Edmund died. Henry VIII himself was very wary of potential claimants toppling him. His execution of Edmund de la Pole in 1513 and the duke of Buckingham in 1521 are the best manifestations of this insecurity.

#henry vii of england#war of the roses#tudor era#Perkin Warbeck is named 'Richard'#we don't have definite proof of his identity#richard iii

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Court Archetypes: The Pretender

There are always those who want the throne. They carve it, they need the power it gives... or else somebody behind them wants them to do it. Pretenders add a threat to any throne as well as interesting subplots for your WIP.

The Successful

These were all pretenders in their times but they won their throne and kept it for a number of years.

Stephen I of England: Henry I had one son and a daughter. His son died in a shipwreck, leaving his daughter, Matilda or Maud to take the throne on his death. During this period, England's empire straddled the Channel. Matilda was in France when her father died and pregnant as well. In her absence, her cousin Stephen seized the throne. So ensued a bloody war for the throne which Matilda was winning at one point, entering her coronation but was chased away by Londoners. Matilda gave up the war on the terms that her son Henry would become King when Stephen died, which he did.

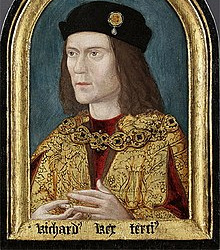

Richard III: I like Richard. He suffered from scoliosis, remained loyal to his brother and had a fairytale-like elopement with his wife. In 1483, Richard's brother died leaving a twelve year old heir. Richard had agreed to act as Regent but after putting off the prince's coronation for months, arresting the boys maternal uncle and half brother, executing his dead brother's best friend and imprisoning his brother in the tower with him, Richard seized the throne. There is murkiness about whether Richard had the boys killed. The boys did vanish but whether it was Richard or another power, we can never know for certain. Personally, I think Richard was acting in protection for the realm which would have been endanger from civil unrest, the commons resented the Queen's family and there were other pretenders. Richard was a tested battle commander and the strongest hope to keep the country stable. I think he had good intentions if he went the wrong way about it.

Edward IV: Edward was the son of another pretender, Richard of York. When Richard of York died at the hands of Margaret of Anjou along with his young son Edmund, Edward took up the mantle of kingship and ousted the House of Lancaster from the throne, installing the House of York.

The Exiles

Some royals were thrown out of their homeland by either a coup or another pretender. Sometimes they're the hero, other times they are not.

Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie): I have mixed feelings about this man. He doesn't deserve the grand legend attached to him nor the kindness history gilds him with. He was a drunken fool who led thousands to their death like his shithead father. But his claim is just. The only reason barring him from his throne is his religion. His story should have been a fairytale, the prince riding to reclaim his family throne. But he died a poor beggar, drinking and lamenting past glories.

Charles II: Charles II was exiled from England along with his mother and younger siblings after the monarchy was overthrown. Charles was technically a pretender while Oliver "Dickbreath" Cromwell ruled England. He shot his shot when Cromwell died and restored the monarchy.

Henry VII: Henry had no chance at throne. Born of a legitimized bastard line and a Welsh line, Henry was not the first person people thought of when considering heirs to the throne. During the mess of the Wars of the Roses, he got closer and closer to the throne which meant he was a threat to the Yorkist line. He escaped to Brittany and then to France, where he waited for his chance. His mother helped orchestrate his two invasions of England, his second being successful at Bosworth Field.

The False

Some Pretenders are not pretenders at all. Some Pretenders are charlatans or mad men or perhaps greedy fools. Some are even almost successful

Perkin Warbeck (Richard Plantagenet/ Richard IV?): Perkin Warbeck, the son of a Tournai boatman, invaded England in 1495 under the guise of Prince Richard Plantagenet, Prince no. 2 in the Tower. He went to Scotland to garner support, winning a wife from the Scottish King. He rode south toward London, the country divided in opinion over his legitimacy. Was he the lost Prince of York? Real or not, Warbeck was defeated. Henry VII chose to be merciful offering Warbeck a place a court which he accepted. But the plots kept swirling about the mysterious pretender. In order to secure an alliance with Spain, Henry was finally forced to kill the pretender. Was he really Prince Richard? Some historians say no, some say yes. As for me, I am open to the theory that he is but I rather liked to think that if Prince Richard did survive the Tower, that he found safety somewhere far away and forgot all about crowns and thrones. Of course, that's just wishful thinking....

Anna Andersen (Anastasia Romanov): In 1918, the Russian Tsar, Tsarina, Tsarevitch and four Grand Duchesses were executed by rebels. Once that terrible murder happened, rumours began to spread that one daughter had escaped when they were burying the bodies, helped away by a young scared soldier. The rumours allowed pretenders to come forward pretending to be the youngest daughter, Anastasia. The remaining Russian royals met with several promising ones but they all cons. In Germany in the 1920s, a young woman began claiming to be the Grand Duchess. A few members of the royal family met her and believed her along with her childhood friend, Gleb Botkin. There was some evidence, her signature was the same, she knew somethings about the Grand Duchess's childhood and had similar birth marks. By the time DNA testing came about, Anderson was dead. They tested her remains and it was clear that she was a pretender. I don't like Andersen but I think that she did believe in the lie, she was emotionally disturbed person with a history of mental illness.

Yemelyan Pugachev (Peter III of Russia): Pugachev was a Cossack who led a rebellion against Catherine the Great. He convinced a great number of Russian serfs that he was the dickweed Peter III, who had died months after his wife Catherine kicked him off the throne. She may or may not have known about the assassination plot against his life. Catherine's armies obliterated the rebellion and Pugachev was beheaded, drawn and quartered.

The Puppet

Some Pretenders are just innocents who troublemakers gather about in order to gain power. The puppet pretender is always a sympathetic figure in literature.

Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick: Edward was a simple-minded child whose great misfortune it was to be born into the House of York. The son of the Duke of Clarence, the brother to two of England's kings, he was named heir to the throne by his uncle Richard III when his own son died. Edward was imprisoned in the Tower when Henry VII came to power. But though Edward was likely incapable of ruling, Yorkist rebels kept rebelling in his name. In 1499, he was executed at the behest of the Anglo-Spanish treaty. He was a harmless man killed for a throne he likely didn't even realise was his by right. It is probably the one of the only events of history that I hate.

Lambert Simnel: Lambert Simnel was a pretender to the throne during the reign of Henry VII. He was a schoolboy who was placed at the head of a Yorkist rebellion for the resemblance between he and the Princes in the Tower. He was put forward as the Earl of Warwick, who people believed had escaped the Tower. When the rebellion was quashed, Henry VII was merciful and had the boy placed in the kitchens as a spit boy. Years later, he went on to become a royal falconer. Nothing else is known about his life.

Lady Jane Grey, Queen of England: Jane Grey was named Queen by her predecessor and cousin Edward VI. This was mainly due to her being Protestant as Edward VI was a Reformer. Jane had not wanted to be Queen, claiming that it was her Catholic cousin's throne not hers. In the name of faith, she was pressed to proclaim herself queen, in which the heralds had to explain who she was and how she could be queen. People had trouble with the claim for a few reasons: the succession had never included her only the king's two sisters, her mother who she drew her claim through was still alive meaning her mother was ahead of her by rights and nobody knew who she was. Jane's ascension had been a grand plot hatched by the Dukes of Suffolk and Northumberland. Northumberland wed Jane to his own son only months before. But Jane was no shrinking violet. In her nine days, she told her husband that he would never be king only a duke, she wrote her declarations signing herself as queen and ordered Northumberland to head her armies in place of her father. When Mary I ousted her from the throne, Jane was glad to give up the throne but not her Protestant faith. After failed rebellions to put Jane back in power, Mary I had no choice but to have her executed.

#court archetypes#Pretenders#Richard iii#stephen I#Anastasia romanov#lambert simnel#lady Jane Grey#writing advice writing resources#writer problems#writing resources writing reference#writing reference#writing resources#writing advice#fantasy#fantasy nobility#fantasy guide#writing guide#characters#fantasy characters#fantasy courts#history dump#archetypes#fantasy archetypes

763 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK. I've got to ask--Henry VI? I think you're the first person I've met who claims those as their favorite Shakespeare. I'll admit that I've read and seen a fair bit of Shakespeare, but I'm not familiar with them at all. What's the appeal? Why do you love them? Sell them to me. ;)

Oh boy, here we go :))))) (Thank you for giving me permission to scream - I also think I’m the only person I’ve ever met who has those as their favorite Shakespeare plays). Also, as we’ve talked opera - I think these plays could make a great Wagnerian style opera cycle.

First off, little disclaimer: I’m not a medievalist, so I can’t say that I’ve definitely got the best interpretation of the Wars of the Roses and the history that the H6 cycle covers. I know I do not - so you may read these plays and have totally different interpretations, and that’s great! This will kind of be how I came to love the plays and why they were (and still are) exciting for me to read.

I will admit, these plays are a bit of a minefield (as my Shakespeare professor said during a lecture on the histories and I don’t think I’ll ever forget that descriptor). Some of these scenes are not as well written, and many of them are almost irrelevant to telling a tight-knit story, so things get cut. Sometimes 1H6 is just cut entirely from productions, and I might venture to say that it is probably the least performed Shakespeare play. We get lines like “O, were mine eyeballs into bullets turn’d, / That I in a rage might shoot them at your faces” (1H6.4.4.79-80), which I might say is nearly on par with “a little touch of Harry in the night” from Henry V. But despite the unevenness, there is so much from these plays that are meaningful, heartbreaking, and that continue to fascinate me. There’s so much about power and leadership that we can learn from these plays - and perhaps that’s why I took an interest in 1990s British politics because there are actually some very interesting similarities happening - but also a lot we can learn about empathy, hope, and love.

These plays have a lot of fascinating key players - it would honestly be a privilege to play any of them - and most (if not all) of these key players have some claim to power, just in the family lines they were born into. And this conflict is one that’s been building up since Richard II. With the Wars of the Roses we have a man who is unwilling, and sometimes unable to lead because of various circumstances, some of which having to do with his mental health, which was generally poor, and some of which have to do with the various times he was dethroned, captured, etc. - and I say unable for lack of a better word. Essentially, politics in these plays are caving in, and at a very rapid pace. There’s a hole at the center of government and people are ambitious to fill it. We also have a lot of people who could potentially fill that role, people who on principle, have a lot of political enemies. The nobles in these plays are having to assure that they themselves are in power or that their ally is in power, otherwise it is their livelihood at stake.

We have Henry VI, who was made king at nine months old after the untimely death of his father, the famous Henry V, and basically has people swarming him since birth claiming that they’re working in his best interest. He’s a bit of a self-preservationist to start, but by the end we see a man completely transformed by the horrors of war and ruthless politics. I also think he might be the only Shakespeare character who gets his entire life played out on stage. We see him at every stage of his life, which makes his descent all the more bitter. (One cannot help but see the broken man he is at forty-nine and be forced to remember the spritely, kind boy he was at ten). He’s a man who clings closely to God in an environment where God seems to be absent. He desires peace, if nothing else, and he wants to achieve this by talking things through. He’s an excellent orator (one only needs to look at the “Ay Margaret; my heart is drown’d with grief” monologue from 2H6, but there are countless other examples), but there’s a point where even he realizes that his talking will achieve nothing, and his alternative is heartbreaking.

We have his wife, Queen Margaret, otherwise known as Margaret of Anjou, or the “she-wolf of France”. I advertise her as “if you like Lady Macbeth, you’ll love Margaret of Anjou”. Sometimes Shakespeare can portray her as wanting power for herself, but I genuinely think she wanted a good life for her husband and her child, otherwise the alternative is begging at her uncle’s feet for protection in France (her uncle was Charles VII of France) while separated from her husband, having her or a member of her immediate family be killed, or worse. I think it’s important to remember with Margaret that historically she came from a family where women took power if their husbands were unable to. Her assumption of power in these plays is something that’s natural to her, even if it’s not reflected very well in Shakespeare’s language. You also see some fantastically thrilling monologues from Margaret as well, especially her molehill speech (one of two molehill speeches in 3H6, totally different in nature - the other one is from a heartbroken and forlorn Henry after the Battle of Towton) - Margaret’s monologue has got the energy of a hungry cat holding a mouse by the tail.

Also Henry and Margaret have a fascinating relationship. Because they’re so different in how they resolve conflicts, they grow somewhat disenchanted with each other at times, and can actually be mean to one another, despite their love. My favorite scene might be at the start of 3H6, where Margaret has come in with their seven year old son, Edward, and starts berating Henry for giving the line of succession to the Yorkists. What strikes me there is that we have a little boy having to choose between staying with his mom, or going with his dad - it’s something very domestic, and I think the emotional accessibility of that scene is what makes it memorable. It’s not about politics for me at that moment, it’s about a boy having to choose between his very estranged parents. Here’s a little taste from 1.1. in 3H6 - lines 255-261:

QUEEN MARGARET: Come son, let’s away. / Our army is ready; come, we’ll after them.

KING HENRY: Stay, gentle Margaret, and hear me speak.

QUEEN MARGARET: Thou hast spoke too much already. Get thee gone.

KING HENRY: Gentle son Edward, thou wilt stay with me?

QUEEN MARGARET: Ay, to be murdered by his enemies.

We also have Richard, Duke of York, who is Henry’s cousin and leader of the Yorkist faction. If you’re at all familiar with 1990s British politics, as I have grown close to over the past month, York reminds me very much of Michael Heseltine (filthy rich and constantly vying for power) - and I would love to stage some kind of modern H6 cycle production just so I could make that connection. York’s father is one of the three traitors executed by Henry V at the start of H5, leaving him an orphan at four years old (historically). He is also Aumerle’s (from R2) nephew, and so when Aumerle dies at the Battle of Agincourt, little four year old Richard inherits both his father’s money and titles, and his uncle’s money and titles, making him the second richest nobleman in England behind the King. All this information is historical and doesn’t really show up in the play, but I think that kind of background would give a man some entitlement. He’s also next in line for the throne if something were to happen to Henry (until Henry has a son), so he feels it is his duty as heir to the throne to protect Henry (or in better words, he feels that he should be running the show) - Margaret feels that it is her duty to protect Henry as she is his wife and mother of Edward of Westminster, the Lancastrian heir, and so you can see where these two are going to disagree.

More fascinating are York’s sons, Edward, George, and Richard. Edward is this (for lack of better words) “hip” eighteen year old who comes and shreds things up at the Battle of Towton - becoming Edward IV in the process and chasing Henry off the throne. He is incredibly problematic, but I might venture to say that he’s the least problematic of the trio of York brothers. George of Clarence is (also for lack of better words) “a hot mess” and feels entitled to power, even though he may not readily give his motivations for it. I think he just wants it, and so he actually ends up switching sides mid-3H6 because he would actually be in a better position in government with those new allies. And finally, we have Richard of Gloucester (future Richard III), and in 3H6, you just get to see him sparkle. It puzzles me a bit how people can just jump into Richard III without getting any of the lead up that Shakespeare gave in the H6 cycle, and I think 3H6 is the perfect play to see that. I think it clears up a lot of his motivation, which Shakespeare didn’t get perfectly either, because there are some ableist things going on with these plays. He’s just as bloodthirsty, just as cynical, but in this play, he wins out the day.

These are just a few of the main characters. We’ve also got Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (known to history as “The Kingmaker”), who is this incredibly powerful nobleman who is wicked skilled in battle and seems to have a lot of luck in that area (until he doesn’t). We’ve got Clifford, who is just as bloodthirsty as Richard III (if not more so). We’ve also got Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester - Henry’s uncle and quite unpopular with his fellow noblemen, and Eleanor Cobham, his wife who gets caught in the act of witchcraft. (Talk to my lovely friend @nuingiliath if you want to hear about Humphrey or Eleanor). Joan of Arc also makes an appearance in 1H6, and often she’s the only reason that 1H6 gets performed.

There are so many ways to latch onto this cycle, and it can be for the huge arcs that these characters go on, or it can be for the very small reasons, like in the first scene of 3H6, like I mentioned earlier. It’s very much akin to Titus Andronicus in the language (I did a bit of research a while ago about the use of animal-focused language in Shakespeare’s plays, and the H6 cycle and Titus Andronicus lead the charts just in terms of frequency of people being referred to metaphorically as animals- they’re also chronological neighbors, all written very early in Shakespeare’s career). Also, these plays held a huge amount of weight at the time they were written - the effects of the Wars of the Roses were still pressing over the political climate of the 1590s.

I think these plays are great to read just in being able to contextualize the histories as a whole - you get to know how things fared after Henry V (spoiler: not well), and you also get the lead up to Richard III. The ghosts in Richard’s dream make sense after reading the H6 cycle - because those ghosts lived in the H6 cycle, and (spoiler: Richard wronged them in the H6 cycle). They were also the first of Shakespeare’s history plays, so you read subsequent histories plays that make subtle references to the H6 cycle, and I think you can take so much more out of the rest of the histories plays once you’ve read these.

I hope this was a little informative, and perhaps persuaded you to check them out!

Productions I recommend (you can click on the bold titles and it’ll take you to where you can access these productions):

Shakespeare’s Globe at Barnet (2013) // Graham Butler (Henry VI), Mary Doherty (Margaret of Anjou), Brendan O’Hea (Richard, Duke of York), Simon Harrison (Richard of Gloucester) - filmed at Barnet, location of the Battle of Barnet, where Warwick was killed in 1471.

ESC Production (1990) // Paul Brennen (Henry VI), June Watson (Margaret of Anjou), Barry Stanton (Richard, Duke of York), Andrew Jarvis (Richard of Gloucester) - a more modern production, one cast put together all seven major Plantagenet history plays (1H6 and 2H6 are combined into one play - a normal practice). Sometimes this footage can be a bit fuzzy, but I loved this production.

The Hollow Crown Season 2 // Tom Sturridge (Henry VI), Sophie Okonedo (Margaret of Anjou), Adrian Dunbar (Richard, Duke of York), Benedict Cumberbatch (Richard of Gloucester) - done in a film-like style, also with some pretty big name actors as you can see. Season 1 stars Ben Whishaw as Richard II, Jeremy Irons as Henry IV, Simon Russell Beale as Falstaff, and Tom Hiddleston as Hal/Henry V. (also available on iTunes)

RSC Wars of the Roses (1965) // David Warner (Henry VI), Peggy Ashcroft (Margaret of Anjou), Donald Sinden (Richard, Duke of York), Ian Holm (Richard of Gloucester) - black and white film, done in parts on YouTube.

BBC Henry VI Plays (1983) // Peter Benson (Henry VI), Julia Foster (Margaret of Anjou), Bernard Hill (Richard, Duke of York), Ron Cook (Richard of Gloucester) - features my favorite filmed performance of Edward IV (played by Brian Protheroe), and my favorite filmed performance of Warwick (played by Mark Wing-Davey).

Also if you ever get to see Rosa Joshi’s production of an all female H6 cycle... *like every time I see photos my immediate reaction is *heart eyes* I haven’t seen it yet, but my amazing friend and fellow Shakespearean @princess-of-france has - I’m sure she’d love to talk more about it sometime! I’ll leave a picture I found on the internet...

Also tagging @suits-of-woe because we could cry about these plays all day.

#thank you for this!#i'm not putting it under a cut because my tumblr has been weird with that function lately#so instead i will tag it#long post#henry vi#h6 cycle#shakespeare#shakespeare's histories#the histories#1H6#2H6#3H6#also friends add on!#we have a neat little histories fandom on here#add the reasons h6 is a lovely thing and should be advertised more#i'd love to hear your thoughts#this is very general#i love the character of henry vi in particular#but all of them are fascinating#also there's a point in 2H6 where henry is so overcome with shock and grief that he just faints#like same but poor bby#that's my favorite moment in the whole cycle actually#there's some switch that goes off in him after that#i just love these plays ahhh#theatre#shakespeare discussion#the wars of the roses#vera-dauriac

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

House of Valois & of Habsburg: Mary, The Duchess of Burgundy

Mary was born as the only child of Charles the Bold, The Duke of Burgundy, and his second wife Isabella of Bourbon. Although celebrated lavishly, neither her grandfather nor her father took part in her christening. Her godparents were her paternal grandmother Infanta Isabella of Portugal and King Louis XI. of France, at the time still The Dauphin of France.

For the first six years of her life, she lived with her parents. But when her father became The Governor of Holland, he moved with his wife but without his daughter there. Mary was sent to Ghent to prevent further riots of the citizens there. She was raised bilingual in French and Flemish but always prevered French. Mary received a formal education befitting that of a princess but was never prepared to rule as her parents still hoped for a male heir. This hope ended when Isabella of Bourbon died in 1465. The marriage of Charles and Margaret of York, which happened in 1468, resulted in no further children, keeping Mary as the sole heir.

Margaret, who was only eleven years older than Mary, became one of young woman’s most trusted advisors and friends. Their relationship was described as sisterly. Margaret also taught her stepdaughter the English language.

In 1467, Mary’s grandfather died and her father became The Duke of Burgundy. The 10-year-old Mary was his only living child and became his heir presumptive. Because of that and the wealth the House of Burgundy controlled, she was an interesting marriage candidate. Already five years prior a marriage between the future king of Aragon, Ferdinand II, and her was proposed. Charles, The Duke of Berry - the younger brother of Mary’s godfather King Louis XI of France - approached her as well as Nicholas, The Duke of Lorraine, who was killed in battle in 1473.

The question of a husband would reappear when Mary succeeded her father at the age of only twenty. Her godfather seized the opportunity of a defenseless Mary and invaded great parts of her country. Louis XI presented himself as a patron saint for Mary and demanded of her to marry his only seven-year-old son and heir Charles. Mary also felt pressure from within her country. Only a month after her accession, she had to grant the Great Privilege to her citizens. It included that she had no right to declare war, make peace, or raise taxes without the consent of the provinces and towns and only to employ native residents in official posts.

Mary’s only chance for regaining control was to marry and she did. Archduke Maximilian of Austria, The Holy Roman Emperor’s only son and heir. With their marriage on August 19th, 1477, he became the co-ruler of Burgundy. The couple had three children of whom the two oldest survived into adulthood: Philip the Handsome and Archduchess Margaret of Austria. Philip would later become the first Habsburg king of Castile through his marriage to Queen Joanna “the Mad” of Castile. He was the founder of the Spanish branch of the House of Habsburg. Margaret would marry twice, first becoming The Princess of Asturias and second The Countess of Savoy. Later, she was made the governess of the Habsburg Netherlands by her father after her brother’s death.

Mary of Burgundy died on March 7th, 1482, at the age of only 25 due to injuries she suffered after falling from her horse during a falcon hunt. With her death, her inheritance went to the House of Habsburg through her son Philip. This would lead to a brewing conflict between France and Spain in the following 200 years. If she had not died young, she would have gone on to become Holy Roman Empress through her husband Maximilian I.

// Christa Théret as Mary of Burgundy in Maximilian - Das Spiel von Macht und Liebe

#perioddramaedit#period drama#mary of burgundy#historyedit#historic women#15th century#european history#1400s#house of habsburg#house of valois-burgundy#maximilian - das spiel von macht und liebe#female rulers#austrian history#royal women of austria#House of Valois

541 notes

·

View notes

Text

14th King of Portugal (5th of the Aviz Dynasty): King Manuel I of Portugal, “The Fortunate)

Reign: 25 October 1495 – 13 December 1521

Acclamation: 27 October 1495

Predecessor: João II

Manuel I (31 May 1469 in Alcochete – 13 December 1521 in Lisbon ), the Fortunate (o Venturoso, o Afortunado), King of Portugal, was the son of Fernando, Duke of Viseu,

by his wife, the Infanta Beatriz of Portugal.

His name is associated with a period of Portuguese history distinguished by significant achievements both in political affairs and in the arts. In spite of Portugal's small size and population in comparison to the great European land powers of France, Italy and even Spain, the classical Portuguese Armada was the largest in the world at the time. During Manuel's reign Portugal was able to acquire an overseas empire of vast proportions, the first in world history to reach global dimensions. The landmark symbol of the period was the Portuguese discovery of Brazil and South America in April 1500.

Manuel's mother was the granddaughter of King João I of Portugal,

whereas his father was the second surviving son of King Duarte of Portugal

and the younger brother of King Afonso V of Portugal.

In 1495, Manuel succeeded his first cousin, King João II of Portugal, who was also his brother-in-law, as husband to Manuel's sister, Leonor of Viseu.

Manuel grew up amidst conspiracies of the Portuguese upper nobility against King João II. He was aware of many people being killed and exiled. His older brother Diogo, Duke of Viseu, was stabbed to death in 1484 by the king himself.

Manuel thus would have had every reason to worry when he received a royal order in 1493 to present himself to the king, but his fears were groundless: João II wanted to name him heir to the throne after the death of his son Prince Afonso and the failed attempts to legitimize Jorge, Duke of Coimbra, his illegitimate son. As a result of this stroke of luck, Manuel was nicknamed the Fortunate, and succeeded on João's death in 1495.

Imperial Growth

Manuel would prove a worthy successor to his cousin João II for his support of Portuguese exploration of the Atlantic Ocean and development of Portuguese commerce. During his reign, the following achievements were realized:

1498 – The discovery of a maritime route to India by Vasco da Gama

1500 – The discovery of Brazil by Pedro Álvares Cabral.

1501 – The discovery of Labrador by Gaspar

and Miguel Corte-Real.

1505 – The appointment of Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of India

1503–1515 – The establishment of monopolies on maritime trade routes to the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf by Afonso de Albuquerque, an admiral, for the benefit of Portugal.

The capture of Malacca in modern-day Malaysia in 1511 was the result of a plan by Manuel I to thwart the Muslim trade in the Indian Ocean by capturing Aden, blocking trade through Alexandria, capturing Ormuz to block trade through the Persian Gulf and Beirut, and capturing Malacca to control trade with China.

All these events made Portugal wealthy from foreign trade as it formally established a vast overseas empire. Manuel used the wealth to build a number of royal buildings (in the "Manueline" style) and to attract scientists and artists to his court. Commercial treaties and diplomatic alliances were forged with Ming dynasty of China and the Persian Safavid dynasty. Pope Leo X

received a monumental embassy from Portugal during his reign designed to draw attention to Portugal's newly acquired riches to all of Europe.

Manueline Ordinations

In Manuel's reign, royal absolutism was the method of government. The Portuguese Cortes (the assembly of the kingdom) met only three times during his reign, always in Lisbon, the king's seat. He reformed the courts of justice and the municipal charters with the crown, modernizing taxes and the concepts of tributes and rights. During his reign, the laws in force in the kingdom of Portugal were recodified with the publication of the Manueline Ordinations.

Religious policy

Manuel was a very religious man and invested a large amount of Portuguese income to send missionaries to the new colonies, among them Francisco Álvares, and sponsor the construction of religious buildings, such as the Monastery of Jerónimos.

Manuel also endeavoured to promote another crusade against the Turks.

The Jews in Portugal

His relationship with the Portuguese Jews started out well. At the outset of his reign, he released all the Jews who had been made captive during the reign of João II. Unfortunately for the Jews, he decided that he wanted to marry Infanta Isabel of Aragon,

then heiress of the future united crown of Spain (and widow of his nephew Prince Afonso). Her parents Fernando and Isabel had expelled the Jews in 1492 and would never marry their daughter to the king of a country that still tolerated their presence. In the marriage contract, Manuel I agreed to persecute the Jews of Portugal.

In December 1496, it was decreed that all Jews either convert to Christianity or leave the country without their children. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the king. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who tried to use coercion and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country.

This period of time technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as "New Christians", and they were given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith would be allowed; this was later extended to end in 1534.

During the course of the Lisbon massacre of 1506, people invaded the Jewish Quarter and murdered thousands of accused Jews; the leaders of the riot were executed by Manuel.

Isabel died in childbirth in 1498, thus putting a damper on Portuguese ambitions to rule in Spain, which various rulers had harbored since the reign of King Fernando I (1367–1383).

Manuel and Isabel's young son Miguel

was for a period the heir apparent of Castile and Aragon, but his death in 1500 at the age of two years ended these ambitions.

Manuel's next wife, Maria of Aragon,

was his first wife's younger sister. Two of their sons later became kings of Portugal. Maria died in 1517 but the two sisters were survived by an older sister, Joana of Castile, who was born in 1479 and had married the Archduke Philip (Maximilian I's son) and had a son, Charles V who would eventually inherit Spain and the Habsburg possessions.

Manuel I was awarded the Golden Rose by Pope Julius II in 1506 and by Pope Leo X in 1514. Manuel I became the first individual to receive more than one Golden Rose after Emperor Sigismund von Luxembourg.

Manuel died of unknown causes on December 13 of 1521 at age 52. The Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon houses Manuel's and Maria’s tombs. His son João succeeded him as king.

Negotiations for a marriage between Manuel and Elizabeth of York

in 1485 were halted by the death of Richard III of England.

He went on to marry three times. His first wife was Isabel of Aragon, princess of Spain and widow of the previous Prince of Portugal Afonso. Next, he married another princess of Spain, Maria of Aragon (his first wife's sister), and then Leonor of Austria,

a niece of his first two wives, who married Francis I of France

after Manuel's death.

By Isabella of Aragon (2 October 1470 – 28 August 1498; married in 1497)

Miguel da Paz, Prince of Portugal (23 August 1498 - 19 July 1500) 1 year 10 months - Prince of Portugal, Prince of Asturias and heir to the crowns of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon.

By Maria of Aragon (19 June 1482 – 7 March 1517; married in 1500)

João, Prince of Portugal (7 June 1502 - 11 June 1557), 55 years - Succeeded the throne as João III, King of Portugal.

Infanta Isabel (24 October 1503 - 1 May 1539), 35 years - Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Infanta Beatriz (31 December 1504 - 8 January 1538), 33 years - Duchess of Savoy by marriage to Charles III, Duke of Savoy.

Infante Luís (3 March 1506 - 27 November 1555), 49 years - Duke of Beja. Unmarried but had illegitimate descendants, one of them being António, Prior of Crato, a claimant of the throne of Portugal in 1580; see: Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Infante Fernando (5 June 1507 - 7 November 1534), 27 years - Duke of Guarda. Married Guiomar Coutinho, 5th Countess of Marialva and 3rd Countess of Loulé (died 1534). No surviving issue.

Infante Afonso (23 April 1509 - 21 April 1540) 30 years - Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church

Infante Henrique (31 January 1512 - 31 January 1580), 68 years - Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who succeeded his grandnephew, King Sebastião (Manuel I's great-grandson), as Cardinal Henrique, King of Portugal. His death triggered the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Infanta Maria (3 February 1513) Died immediately after birth.

Infante Duarte (7 October 1515 - 20 September 1540), 24 years - Duke of Guimarães and great-grandfather of João IV of Portugal. Married Isabel of Bragança, daughter of Jaime, Duke of Bragança.

Infante António (9 September 1516) - Died immediately after birth.

By Leonor of Austria (15 November 1498 – 25 February 1558; married in 1518)

Infante Carlos (18 February 1520 - 14 April 1521), 1 year 1 month

Infanta Maria (18 June 1521 - 10 October 1577) 56 years - Unmarried

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On the 2nd of October 1452, Cecily Neville gave birth to her youngest son at Fortheringhay Castle. Years after his death, Tudor chroniclers wrote fantastical tales about his birth. More said that she was in “much doe in her travail” and that he was born with a full set of hair and crooked teeth. There is no actual record of the birth and the chronicler of the Neville family, Rous, wrote that he was healthy and he “liveth yet”. The reason why he said this was because Cecily became pregnant again three years after and gave birth to a girl who died that same year. Also, infant mortality was high so the fact he survived was something to take into account.

At the age of seven, Richard was exposed to the realities of war. It is written that she was “despoiled” of her goods, and while this could mean rape, it could also mean that they looted her house. The latter was still a big humiliation, to see her possessions being taken by common men and soldiers.

Cecily went to the city of Coventry where Parliament was held (a parliament that became known as “Parliament of Devils”) and submitted herself to royal mercy. But at this point, tensions were too high and it was clear that only one victor could emerge from this conflict.

“Without her husband by her side, Cecily had little choice but to submit to the rule of Henry VI and was placed in the custody of her sister Anne at Tonbridge Castle in Kent.” (Licence)

Anne was the Duchess of Buckingham through her marriage to John Stafford and as such, a staunch Lancastrian. Initially Cecily took her sons with her, but in the end she decided to send them away to Burgundy.

Sarah Gristwood in her biography notes that the “comparative lenience with which Cecily was treated was the result of her friendship with Queen Marguerite” yet she also notes what the chroniclers at the time said, that she was kept “full straight with many a rebuke” from her sister. “The future prominence of Cecily’s son” Gristwood points out, referring to her eldest, Edward the Earl of March “had never looked more unlikely.”

In 1460 however, the Yorkists scored a major victory when they took control of the capital and forced Henry VI to recognize the Duke of York as his heir. Cecily was sent for and the couple were not only Duke and Duchess of York anymore, but by right they were Prince and Princess of Wales. But things took a turn for the worse on that December when Marguerite’s troops took them by surprise at Sandal Castle and killed everyone, including Cecily’s brother, nephew, and her second son Edmund, the Earl of Rutland.

It wasn’t until 1461, when Richard’s oldest brother became King, that the family finally felt secure. Edward IV made Dukes of him and George. Richard was awarded the title of Duke of Gloucester. And then the rest –as they say- is history when he decided to marry a Lancastrian widow over Warwick’s proposal with Bona of Savoy. This split the Yorkist house in two ending with his cousin Warwick’s death in the battle of Barnet, the destruction of the Lancastrian, and seven years later the execution of his brother George. And then Edward died (possibly as a result of a cold, although Mancini said it was because of his “vices”) and the crown was free for the taking. It is very possible that Richard didn’t intend to take the crown at first like later Tudor version depict, but rather like his father, gain control of his nephew since he believed he was more suited to do so then the boy’s maternal relatives who were very hated with the nobility. But as the Queen locked herself in sanctuary, and then fearing repercussion from her relatives and allies, he executed her brother and his brother’s allies; he realized things had gone too far. And once again, like his father he was going to make a move that changed the history of the dynasty.

He and his wife, Anne Neville were crowned on July of that year, with their only son Edward of Middleham invested as Prince of Wales later that autumn in the North.

Although the Lancastrian royal line was wiped out, one scion remained and even though some considered his mother’s line a bastard line, many still saw him as the heir to the Lancastrian cause, and Edwardian Yorkists who were not too happy with Richard’s rule fled to Brittany to join him in his exile. The youth’s name was Henry Tudor, and like Richard, he had been privy to the horrors of war at a young age.

Richard ruled for over two years. And to this day, he is the hot topic of almost every conversation regarding the wars of the roses. Was he a good or bad king? Or was he a victim of circumstance?

It is easier to say as one historian once said in an interview, that he was neither. On one front we have him doing great things for the country such as improving the law courts and allowing more common people to have representation, and he was very loved in the North; on the other hand we also have him be as ruthless as any king could be in this era, and executing as many as he saw fit to keep his power.

The rumors of him poisoning his wife are of course exaggerated, he probably loved her but as King he had to think of the future of his dynasty. When their son died in 1484 and she became sick with grief (dying the following year), he was looking for someone else to marry. He publicly denied that he wanted to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York and while he could have contemplated that (at one point), it seems highly unlikely that he would have done that in the end. His intentions in the summer of 1485 reflect that, when he was negotiating for a joint marriage for himself and his niece (Elizabeth) to a Portuguese Princess and Duke.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The beginning of an AU historical fiction about a legitimate daughter of King Charles II of England and Queen Catherine of Braganza, Princess Catherine ‘Kitty’ Stuart.

Today, I am sixteen.

When I was born, in the sweltering summer of 1663, it nearly killed my mother. She barely remembers, of course, I suppose she slipped in and out of this world as I was prized out of her and the memory lives in a haze. But even she, weary as she was, could not keep from asking the question that had hung in the heated atmosphere of her chamber in the preceding hours. Nay, the question had been on every courtiers’ lips since they saw that my mama was big with me a few months earlier. It found its way into every nook and cranny of the palace until it nearly drove my father out of his wits with worry and my mother into floods of tears as she felt her grip on what was expected of her in this new, alien land, loosen.

Will it live?

Then, suddenly, like the crack in the sky on earth’s first day, a cry. A yell.

‘The child lives, your Majesty!’

More wailing. My mother registered it, like a light in the mist, and continued on, anxiously.

‘A son? Um príncipe?’

A brief silence. Held breaths and anxious glances punctuated it.

‘Tis a perfectly healthy girl, your Majesty. Uma princesa!’

Now, my mother is ashamed to own that, at this, she let out one, single sob. In this sob, there was her oft-strangled desire to go home, back to Portugal, to her family. To leave this bleak, wet, heretic kingdom where she was barely trusted and had to look her husband’s concubine in the eye as she dressed her for dinner and chapel. And her only saving grace, in all this, was her ability to bear children, male heirs and prove herself a worthy investment, an obedient daughter, a good queen, and an accomplished woman. That whore, Castlemaine, would never again have had the gall to utter more than ‘Yea’ or ‘Nay’ in her presence had I been a boy, a prince. Alas, it was not to be. I am a girl. God’s will be done.

My father, my glorious father, did not hold the same reservations as mama.

‘Catherine, you clever, brilliant, beautiful creature! You brave, sweet girl!’ he had said, through tears of relief and joy, when he was finally allowed in to see us both, my mother and I.

‘It is a girl, your Majesty. I beg you would not pretend happiness.’

‘Happy? Catherine, I am more than that! I am quite paralysed with the joy of it. And I am relieved that you are well, too.’

Mama has oft told me since that when he reached across the silken covers to kiss her forehead, her sadness began to ebb. Perhaps, she had thought, it was not so bad. We all lived to see another day, after all. She had been holding me in her arms all the while but now she suddenly felt me, realised my weight, understood my shape, and noticed a tiny but fierce heartbeat.

‘She is a very beautiful baby’ she said, finally, looking at me properly now and feeling a pull from all directions, to embrace everything she loved, even in this cold little heretic backwater.

‘She is the prettiest lady in the kingdom. Only a little prettier than her sweet mother, I daresay.’

‘You are not sad that she is a girl? You would not prefer a son, sir?’

‘My dearest queen, she is born of you and I and increases my happiness by the minute. If she were a son, I should feel the same.’

My mother was charmed. This man, this king, was a strange, benevolent man, she thought, and she liked him all the better for it.

‘I suppose she is a princess.’

‘Yes, indeed.’ Papa was scooping me up in his own arms now, for the first time, though he had needed no encouragement to love me.

‘Princess Catherine Henrietta Mary Stuart of England!’ he declared, in his magnificent voice, all full of richness.

‘And Scotland, Ireland and France, Charles.’ My uncle, Jamie, the Duke of York, had arrived by now and was in the door way, trying to scowl, but apparently, as hard as it is to believe, even he found the joy infectious.

‘Details, Jamie. No matter, for she is so beautiful that she should be queen of the whole world, I will wager! Oh, my darling princess, how your father loves thee!’

And so, with that, I was set out on my way. To grow daily in the glorious shadow of my father, King Charles Stuart of England (and Scotland, Ireland and France!), the second of that name, loved intensely by him and my mother, Queen Catherine, who was once a princess of the Most Serene House of Braganza. I am their only legitimate child, a female heir in a world where women are not much listened to. There are always mutterings, most especially amongst the French members of my family and my cousin, King Louis of France, that a son is still preferable. I have the education of a prince, the shooting skills of a country squire, the music skills of a maestro, a little slew of feminine charms but lacking any real womanly beauty, and the wit of a libertine. But, perhaps, after all, they are right. Perhaps a prince would be best.

But today, I do not care. Because today, I am sixteen. And England, the centre of my universe, toasts to my good health and long life.

#my writing#we are gonna pop the biggest bottles if I actually carry on with this#I'm literally nicking maids of honour from anne hyde and young queen anne and queen Mary ii for Kitty lmao#TBH I've had the kitty stuart au for years#I have her husband and stuff already planned out#history

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victims of the Childbed - Anne de Mortimer

Anne was the firstborn of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and Alianor Holland. The Mortimer family held a large amount of land in Ireland, so Anne and her three younger siblings were born at the family estate in Westmeath. The Mortimer children came from a long and twisted line of royal connections. Through her mother Alianor, Anne was descended from both Henry III and Edward I. It was her father Roger who boasted the all-important link to Edward III, for his maternal grandfather was Lionel of Antwerp, Edward’s second surviving son. As such, Roger was the heir apparent to childless King Richard II according to the laws of primogeniture. But in 1398 when Roger was killed fighting the Irish at Kells, his claim passed to his eldest son, Anne’s brother Edmund.

The lives of Anne and her siblings became much more difficult following the death of their father and the overthrow of Richard II in 1399. Richard was deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, who took the throne as Henry IV. Because of the strength of their claims (which were arguably stronger than his own), the Mortimer children were potential threats to Henry’s power. As a preventative measure, Anne’s brothers Edmund and Roger were imprisoned in Berkhamstead Castle but well treated. Meanwhile, Anne and her baby sister Eleanor were left with their mother. Disaster struck again in 1405 when Alianor died, leaving fifteen-year-old Anne and ten-year-old Eleanor quite alone. They lived in a relatively impoverished state for members of the extended royal family. The king was not kindly disposed towards the Mortimer family and gave Anne an annual sum of just £50 for maintenance. This probably also had the effect of devaluing her as a bride.

At sixteen it must have seemed that marriage or religious life were the only ways out of Anne’s situation. She had no dowry and only a small royal allowance, which would make it difficult to find a match in her own class. However, in May of 1406 she married Richard of Conisburgh. Richard was a grandson of Edward III through his father Edmund, Duke of York. Thus, the marriage of Anne and Richard joined two strong claims to the English throne. It is unclear why the marriage even took place, as neither party gained anything. Richard was another “poor” royal relation like Anne. They also married without the consent of family or the king and did not get the consent of the Pope until two years later. (The romantic in me wants to believe it was a love match.) Nevertheless, Anne’s marriage laid the foundation stones for what would be known as the House of York.

Anne and Richard’s first child, Isabel of York, was born in 1409. Around a year later Anne gave birth to a son, Henry, who died in infancy. On September 21, 1411 Anne gave birth to a second boy. She did not live long after, probably dying the following day at the age of twenty. Her son was named Richard after his father. Four years after Anne’s death, her husband was involved in the Southampton Plot to depose Henry V and place Anne’s brother Edmund on the throne. He was caught and subsequently beheaded. At the age of four, little Richard of York inherited his father’s titles and would later succeed his paternal uncle as Duke of York. Richard’s leading role in the early days of the Wars of the Roses has become legendary. Through him, Anne is the grandmother of Edward IV and Richard III, and is an ancestor of all English monarchs after Henry VII.

#I made her chubby because she's Edward IV's grandma#so I have decreed that Elizabeth of York took after her great-grandmother hold your applause#didn't give her a whole lot of adornment bc I don't think she was particularly well off#so this is her 'best dress'#Anne de Mortimer#Plantagenet#house of York#medieval#Richard of York#victims of the childbed#art#my art

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo