#The Dutch East India Company and the Birth of Stock Trading

Text

The Birth of Modern Finance: A Glimpse into the Amsterdam Stock Exchange of 1602

Written by Delvin

The world of finance as we know it today has its roots in the establishment of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in 1602. As the first official stock exchange in the world, it played a pivotal role in shaping the global economy and revolutionizing the way investments were made. In this blog post, we will delve into the fascinating history of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, its early…

View On WordPress

#dailyprompt#Financial#Financial Literacy#knowledge#Modern Finance#Money Fun Facts#Personal Finance#The Amsterdam Stock Exchange#The Amsterdam Stock Exchange: A Historic Milestone in Finance#The Birth of Modern Finance: A Glimpse into the Amsterdam Stock Exchange of 1602#The Dutch East India Company and the Birth of Stock Trading#The Exchange Building and Trading Mechanisms#The Impact of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange

1 note

·

View note

Text

"From Trading Floors to Digital Markets: The Evolving Journey of Stock Markets"

Stock markets have become the lifeblood of the global economy, serving as the backbone for capital formation, wealth creation, and the facilitation of corporate growth. Their history is a fascinating journey through time, reflecting the evolution of finance, business, and technology. This article delves into the rich history of stock markets, tracing their origins, development, and the significant events that have shaped them into the complex systems we know today.

Origins and Early Development

The concept of trading shares of companies can be traced back to the late Middle Ages in Europe, but the establishment of the first official stock exchange is credited to the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, founded in 1602. This was facilitated by the Dutch East India Company, the first company to issue bonds and shares of stock to the general public. It marked the birth of the modern stock market, providing a centralized trading venue for investors to buy and sell shares.

The Evolution of Stock Exchanges

Following the establishment of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, other countries soon recognized the benefits of having a centralized trading platform. The London Stock Exchange (LSE) was founded in 1801, providing a formal structure to the already existing trading activities in London. Across the Atlantic, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), established in 1792, began with 24 stockbrokers signing the Buttonwood Agreement, named after the buttonwood tree they met under. These early stock exchanges set the stage for the global network of stock markets that facilitate the trading of billions of dollars daily.

The Industrial Revolution and Expansion

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant turning point in stock market history. The unprecedented economic growth and technological advancements led to the proliferation of companies seeking capital to expand their operations. This period saw a surge in the number of companies listed on stock exchanges and a diversification of the types of securities traded. Railroads, in particular, were among the first industries to extensively use stock markets for capital raising, demonstrating the vital role of stock markets in supporting industrial and economic expansion.

Crashes and Regulations

The history of stock markets is also punctuated by periods of speculative bubbles and crashes, leading to significant financial losses and economic downturns. The South Sea Bubble of 1720 and the Wall Street Crash of 1929 are among the most notorious market crashes. The latter precipitated the Great Depression, leading to widespread unemployment and economic hardship. These events highlighted the need for regulation to protect investors and maintain market integrity. In response, governments and regulatory bodies introduced a series of measures, including the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 in the United States, establishing rules for the issuance and trading of stocks.

Technological Innovations

The advent of technology has dramatically transformed stock markets. The introduction of telegraphy in the 19th century, followed by the telephone, revolutionized communication and trading speed. However, it was the emergence of electronic trading in the late 20th century that truly reshaped the stock market landscape. The NASDAQ, founded in 1971, was the world's first electronic stock market, facilitating faster and more efficient trading. Today, high-frequency trading and algorithmic trading dominate the markets, utilizing sophisticated algorithms and ultra-fast data networks.

Globalization and the Future

The globalization of financial markets in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has interconnected stock markets like never before. Cross-border investments and multinational listings have become commonplace, with investors and companies benefiting from global capital flows. The rise of emerging markets, particularly in Asia, has introduced new dynamics into the global stock market ecosystem.

As we look to the future, the stock market is set to undergo further transformations with the integration of blockchain technology, the expansion of sustainable and responsible investing, and the continual evolution of regulatory frameworks to address the challenges of a digital economy.

Conclusion

The history of stock markets is a testament to human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of economic growth and prosperity. From the humble beginnings of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange to the sophisticated global network of today, stock markets have evolved to become indispensable to the world economy. As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, the lessons learned from the past will undoubtedly shape the future trajectory of stock markets, ensuring their continued relevance and resilience in the face of change.

0 notes

Text

Treat Your S(h)elf: The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company (2019)

It was not the British government that began seizing great chunks of India in the mid-eighteenth century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by a violent, utterly ruthless and intermittently mentally unstable corporate predator – Clive.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise Of The East India Company

“One of the very first Indian words to enter the English language was the Hindustani slang for plunder: loot. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this word was rarely heard outside the plains of north India until the late eighteenth century, when it became a common term across Britain.”

With these words, populist historian William Dalrymple, introduces his latest book The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. It is a perfect companion piece to his previous book ‘The Last Mughal’ which I have also read avidly. I’m a big fan of William Dalrymple’s writings as I’ve followed his literary output closely.

And this review is harder to be objective when you actually know the author and like him and his family personally. Born a Scot he was schooled at Ampleforth and Cambridge before he wrote his first much lauded travel book (In Xanadu 1989) just after graduation about his trek through Iran and South Asia. Other highly regarded books followed on such subjects as Byzantium and Afghanistan but mostly about his central love, Delhi. He has won many literary awards for his writings and other honours. He slowly turned to writing histories and co-founding the Jaipur Literary Festival (one of the best I’ve ever been to). He has been living on and off outside Delhi on a farmhouse rasing his children and goats with his artist wife, Olivia. It’s delightfully charming.

Whatever he writes he never disappoints. This latest tome I enjoyed immensely even if I disagreed with some of his conclusions.

Dalrymple recounts the remarkable rise of the East India Company from its founding in 1599 to 1803 when it commanded an army twice the size of the British Army and ruled over the Indian subcontinent. Dalrymple targets the British East India Company for its questionable activities over two centuries in India. In the process, he unmasks a passel of crude, extravagant, feckless, greedy, reprobate rascals - the so-called indigenous rulers over whom the Company trampled to conquer India.

None of this is news to me as I’m already familiar with British imperial history but also speaking more personally. Like many other British families we had strong links to the British Empire, especially India, the jewel in its crown. Those links went all the way back to the East India Company. Typically the second or third sons of the landed gentry or others from the rising bourgeois classes with little financial prospects or advancement would seek their fortune overseas and the East India Company was the ticket to their success - or so they thought.

The East India Company tends to get swept under the carpet and instead everyone focuses on the British Empire. But the birth of British colonialism wasn’t engineered in the halls of Whitehall or the Foreign Office but by what Dalrymple calls, “handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London”. There wasn’t any grand design to speak of, just the pursuit of profit. And it was this that opened a Pandora’s Box that defined the following two centuries of British imperialism of India and the rise of its colonial empire.

The 18th-century triumph and then fall of the Company, and its role in founding what became Queen Victoria’s Indian empire is an astonishing story, which has been recounted in books including The Honourable Company by John Keay (1991) and The Corporation that Changed the World by Nick Robins (2006). It is well-trodden territory but Dalrymple, a historian and author who lives in India and has written widely about the Mughal empire, brings to it erudition, deep insight and an entertaining style.

He also takes a different and topical twist on the question how did a joint stock company founded in Elizabethan England come to replace the glorious Mughal Empire of India, ruling that great land for a hundred years? The answer lies mainly in the title of the book. The Anarchy refers not to the period of British rule but to the period before that time. Dalrymple mentions his title is drawn from a remark attributed to Fakir Khair ud-Din Illahabadi, whose Book of Admonition provided the author with the source material and who said of the 18th century “the once peaceful realm of India became the abode of Anarchy.” But Dalrymple goes further and tells the story as a warning from history on the perils of corporate power. The American edition sports the provocative subtitle, “The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire” (compared with the neutral British subtitle, “The Relentless Rise of the East India Company”). However I think the story Dalrymple really tells is also of how government power corrupts commercial enterprise.

It’s an amazing story and Dalrymple tells it with verve and style drawing, as in his previous books, on underused Indian, Persian and French sources. Dalrymple has a wonderful eye for detail e.g. After the Company’s charter is approved in 1600 the merchant adventures scout for ships to undertake the India voyage: “They have been to Deptford to ‘view severall shippes,’ one of which, the May Flowre, was later famous for a voyage heading in the opposite direction”.

What a Game of Thrones styled tv series it would make, and what a tragedy it unfolded in reality. A preface begins with the foundation of the Company by “Customer Smythe” in 1599, who already had experience trading with the Levant. Certain merchants were little better than pirates and the British lagged behind the Dutch, the Portuguese, the French and even the Spanish in their global aspirations. It was with envious eyes that they saw how Spain had so effectively despoiled Central America. The book fast-forwards to 1756, with successive chapters, and a degree of flexibility in chronology, taking the reader up to 1799. What was supposed to be a few trading posts in India and an import/export agreement became, within a century, a geopolitical force in its own right with its own standing army larger than the British Army.

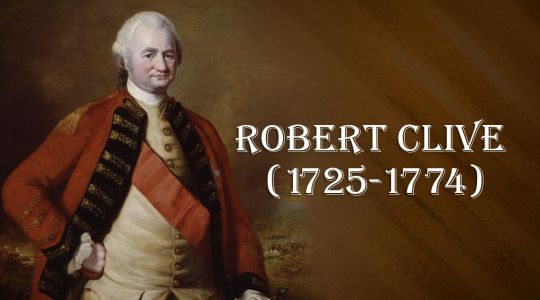

It is a story of Machiavels from both Britain and India, of pitched battles, vying factions, the use of technology in warfare, strange moments of mutual respect, parliamentary impeachment featuring two of the greatest orators of the day (Edmund Burke and Richard Sheridan), blindings, rapes, psychopaths on both sides, unimaginable wealth, avarice, plunder, famine and worse. It is, in particular – because of the feuding groups loyal to the Mughals, the Marathas, the Rohilla Afghans, the so-called “bankers of the world” the Jagat Seths, and local tribal warlords – a kind of Game Of Thrones with pepper, silk and saltpetre. And that is even before we get to the British, characters such as Robert Clive “of India”, victor at the Battle of Plassey and subsequent suicide; the problematic figure of the cultured Warren Hastings, the whistle-blower who became an unfair scapegoat for Company atrocities; and Richard Wellesley, older brother to the more famous Arthur who became the Duke of Wellington. Co-ordinating such a vast canvas requires a deft hand, and Dalrymple manages this (although the list of dramatis personae is useful). There is even a French mercenary who is described as a “pastry cook, pyrotechnic and poltroon”.

When the Red Dragon slipped anchor at Woolwich early in 1601 to exploit the new royal charter granted to the East India Company, the venture started inauspiciously. The ship lay becalmed off Dover for two months before reaching the Indonesian sultanate of Aceh and seizing pepper, cinnamon and cloves from a passing Portuguese vessel. The Company was a strange beast from the start “a joint stock company founded by a motley bunch of explorers and adventurers to trade the world’s riches. This was partly driven by Protestant England’s break with largely Catholic continental Europe. Isolated from their baffled neighbours, the English were forced to scour the globe for new markets and commercial openings further afield. This they did with piratical enthusiasm” William Dalrymple writes. From these Brexit-like roots, it grew into an enterprise that has never been replicated “a business with its own army that conquered swaths of India, seizing minerals, jewels and the wealth of Mughal emperors. This was mercenary globalisation, practised by what the philosopher Edmund Burke called “a state in the guise of a merchant””.

The East India Company’s charter began with an original sin - Elizabeth I granted the company a perpetual monopoly on trade with the East Indies. With its monopoly giving it enhanced access to credit and vast wealth from Indian trade, it’s no surprise that the company grew to control an eighth of all Britain’s imports by the 1750s. Yet it was still primarily a trading company, with some military capacity to defend its factories. That changed thanks to a well-known problem in institutional economics - opportunism by a company agent, in this case Robert Clive of India, who in time became the richest self-made man in the world in time.

Like many start-ups, it had to pivot in its early days, giving up on competing with the entrenched Dutch East India Company in the Spice Islands, and instead specialising in cotton and calico from India. It was an accidental strategy, but it introduced early officials including Sir Thomas Roe to “a world of almost unimaginable splendour” in India, run by the cultured Mughals.

The Nawab of Bengal called the English “a company of base, quarrelling people and foul dealers”, and one local had it that “they live like Englishmen and die like rotten sheep”. But the Company had on its side the adaptiveness and energy of capitalism. It also had a force of 260,000, which was decisive when it stopped negotiating with the Mughals and went to war. After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, “the English gentlemen took off their hats to clap the defeated Shuja ud-Daula, before reinstalling him as a tame ruler, backed by the Company’s Indian troops, and paying it a huge subsidy. “We have at last arrived at that critical Conjuncture, which I have long foreseen” wrote Robert Clive, the “curt, withdrawn and socially awkward young accountant” whose risk-taking and aggression secured crucial military victories for the Company. It was a high point for “the most opulent company in the world,” as Robert Clive described it.

So how was a humble group of British merchants able to take over one of the great empires of history? Under Aurangzeb, the fanatic and ruthless Mughal emperor (1658-1707), the empire grew to its largest geographic extent but only because of decades of continuous warfare and attendant taxing, pillaging, famine, misery and mass death. It was a classic case of the eventual fall of a great power through military over-extension.

At Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, a power struggle ensued but none could command. “Mughal succession disputes and a string of weak and powerless emperors exacerbated the sense of imperial crisis: three emperors were murdered (one was, in addition, first blinded with a hot needle); the mother of one ruler was strangled and the father of another forced off a precipice on his elephant. In the worst year of all, 1719, four different Emperors occupied the Peacock Throne in rapid succession. According to the Mughal historian Khair ud-Din Illahabadi … ‘Disorder and corruption no longer sought to hide themselves and the once peaceful realm of India became a lair of Anarchy’”.

Seeing the chaos at the top, local rulers stopped paying tribute and tried to establish their own power bases. The result was more warfare and a decline in trade as banditry made it unsafe to travel. The Empire appeared ripe to fall. “Delhi in 1737 had around 2 million inhabitants. Larger than London and Paris combined, it was still the most prosperous and magnificent city between Ottoman Istanbul and Imperial Edo (Tokyo). As the Empire fell apart around it, it hung like an overripe mango, huge and inviting, yet clearly in decay, ready to fall and disintegrate”.

In 1739 the mango was plucked by the Persian warlord Nader Shah. Using the latest military technology, horse-mounted cannon, Shah devastated a much larger force of Mughal troops and “managed to capture the Emperor himself by the simple ruse of inviting him to dinner, then refusing to let him leave.” In Delhi, Nader Shah massacred a hundred thousand people and then, after 57 days of pillaging and plundering, left with two hundred years’ worth of Mughal treasure carried on “700 elephants, 4,000 camels and 12,000 horses carrying wagons all laden with gold, silver and precious stones”.

At this time, the East India Company would have probably preferred a stable India but through a series of unforeseen events it gained in relative power as the rest of India crumbled. With the decline of the Mughals, the biggest military power in India was the Marathas and they attacked Bengal, the richest Indian province, looting, plundering, raping and killing as many as 400,000 civilians. Fearing the Maratha hordes, Bengalis fled to the only safe area in the region, the company stronghold in Calcutta. “What was a nightmare for Bengal turned out to be a major opportunity for the Company. Against artillery and cities defended by the trained musketeers of the European powers, the Maratha cavalry was ineffective. Calcutta in particular was protected by a deep defensive ditch especially dug by the Company to keep the Maratha cavalry at bay, and displaced Bengalis now poured over it into the town that they believed offered better protection than any other in the region, more than tripling the size of Calcutta in a decade. … But it was not just the protection of a fortification that was the attraction. Already Calcutta had become a haven of private enterprise, drawing in not just Bengali textile merchants and moneylenders, but also Parsis, Gujaratis and Marwari entrepreneurs and business houses who found it a safe and sheltered environment in which to make their fortunes”. In an early example of what might be called a “charter city,”

English commercial law also attracted entrepreneurs to Calcutta. The “city’s legal system and the availability of a framework of English commercial law and formal commercial contracts, enforceable by the state, all contributed to making it increasingly the destination of choice for merchants and bankers from across Asia”.

The Company benefited by another unforeseen circumstance, Siraj ud-Daula, the Nawab (ruler) of Bengal, was a psychotic rapist who got his kicks from sinking ferry boats in the Ganges and watching the travelers drown. Siraj was uniformly hated by everyone who knew him. “Not one of the many sources for the period — Persian, Bengali, Mughal, French, Dutch or English — has a good word to say about Siraj”. Despite his flaws, Siraj might have stayed in power had he not made the fatal mistake of striking his banker. The Jagat Seth bankers took their revenge when Siraj ud-Daula came into conflict with the Company under Robert Clive. Conspiring with Clive, the Seths arranged for the Nawab’s general to abandon him and thus the Battle of Plassey was won and the stage set for the East India Company.

In typical fashion, Dalrymple devotes half a dozen pages to the Company’s defeat at Pollidur in 1780 by Haider Ali and his son, Tipu, but a few paragraphs to its significance (Haider could have expelled the Company from much of southern India but failed to pursue his advantage). The reader is not spared the gory details.

“Such as were saved from immediate death,” reads a quote from a British survivor about his fellow troops, “were so crowded together…several were in a state of suffocation, while others from the weight of the dead bodies that had fallen upon them were fixed to the spot and therefore at the mercy of the enemy…Some were trampled under the feet of elephants, camels, and horses. Those who were stripped of their clothing lay exposed to the scorching sun, without water and died a lingering and miserable death, becoming prey to ravenous wild animals.”

Many further battles and adventures would ensue before the British were firmly ensconced by 1803 but the general outline of the story remained the same. The EIC prospered due to a combination of luck, disarray among the Company’s rivals and good financing.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam, for example, had been forced to flee Delhi leaving it to be ruled by a succession of Persian, Afghani and Maratha warlords. But after wandering across eastern India for many years, he regathered his army, retook Delhi and almost restored Mughal power. At a key moment, however, he invited into the Red Fort with open arms his “adopted” son, Ghulam Qadir. Ghulam was the actual son of Zabita Khan who had been defeated by Shah Alam sixteen years earlier. Ghulam, at that time a young boy, had been taken hostage by Shah Alam and raised like a son, albeit a son whom Alam probably used as a catamite. Expecting gratitude, Shah Alam instead found Ghulam driven mad. Ghulam Qadir, a psychopath, ordered a minion to blind Shah Alam: “With his Afghan knife….Qandahari Khan first cut one of Shah Alam’s eyes out of its socket; then, the other eye was wrenched out…Shah Alam flopped on the ground like a chicken with its neck cut.” Ghulam took over the Red Fort and after cutting out the eyes of the Mughal emperor, immediately calling for a painter to immortalise the event.

A few pages on, Ghulam Qadir gets his just dessert. Captured by an ally of the emperor, he is hung in a cage, his ears, nose, tongue, and upper lip cut off, his eyes scooped out, then his hands cut off, followed by his genitals and head. Dalrymple out-grosses himself with the description of Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Afghan invader of India, dying of leprosy with “maggots….dropping from the upper part of his putrefying nose into his mouth and food as he ate.”

By 1803, the Company’s army had defeated the Maratha gunners and their French officers, installed Shah Alam as a puppet back on his imitation Peacock Throne in Delhi, and the Company ruled all of India virtually.

Indeed as late as 1803, the Marathas too might have defeated the British but rivalry between Tukoji Holkar and Daulat Rao Scindia prevented an alliance. “Here Wellesley’s masterstroke was to send Holkar a captured letter from Scindia in which the latter plotted with Peshwa Baji Rao to overthrow Holkar … ‘After the war is over, we shall both wreak our full vengeance upon him.’ … After receiving this, Holkar, who had just made the first two days march towards Scindia, turned back and firmly declined to join the coalition”.

For Dalrymple the crucial point was the unsanctioned actions of Robert Clive and the bullying of Shah Alam in the rise of the East India Company.

The Jagat Seths then bribed the company men to attack Siraj. Clive, with an eye for personal gain, was happy attack Siraj at the behest of the Jagat Seths even if the company directors had no part in this. They “consistently abhorred ambitious plans of conquest,” he notes. Clive’s defeat of Siraj at Plassey and the subsequent chain of events that led to Shah Alam giving tax-raising powers to the company in 1765 may be history’s most egregious example of the principal-agent problem.

Thus, the East India Company acquired by accident the ultimate economic rent — a secure, unearned income stream. Company cronies initially thwarted attempts at oversight in London, but a government bailout in 1772 following the Bengal Famine and the collapse of Ayr Bank confirmed the crown’s interest in the company, which had now become Too Big to Fail. Adam Smith called the company’s twin roles of trader and sovereign a “strange absurdity” in Book IV of The Wealth of Nations (unfortunately, Smith’s long condemnatory discussion of the company receives only a cursory reference from Dalrymple).

As part of the bailout, Parliament passed the Tea Act to help the company dump its unsold products on the American colonies by giving it the monopoly on legal tea there (Americans drank mostly smuggled Dutch tea). This, of course, led to the Boston Tea Party and the American Revolution.

By 1784, Parliament had set up an oversight board that increasingly dictated the company’s political affairs. The attempted impeachment of Governor-General Warren Hastings by the House of Lords in 1788 confirmed that the company was no longer its own master. By that stage, the company was an arm of the state. Dalrymple’s coverage of the subsequent racist policies of Lord Cornwallis and the military adventures of Richard Wellesley make for compelling reading, but they are not examples of unfettered corporate power.

Overlaid on top of luck and disorder, was the simple fact that the Company paid its bills. Indeed, the Company paid its sepoys (Indian troops) considerably more than did any of its rivals and it paid them on time. It was able to do so because Indian bankers and moneylenders trusted the Company. “In the end it was this access to unlimited reserves of credit, partly through stable flows of land revenues, and partly through collaboration of Indian moneylenders and financiers, that in this period finally gave the Company its edge over their Indian rivals. It was no longer superior European military technology, nor powers of administration that made the difference. It was the ability to mobilise and transfer massive financial resources that enabled the Company to put the largest and best-trained army in the eastern world into the field”.

Dalrymple pretty much loses interest once the Company gains full control. “This book does not aim to provide a complete history of the East India Company,” he writes. He skips past one mention of Hong Kong, which the East India Company seized after the opium wars in China. A few sentences record the 1857 uprising of Indian soldiers that led to the British government taking India from the Company and establishing the Raj that lasted until Indian independence in 1947.

The author makes passing reference to the fact that the struggle for American independence was underway for much of the period about which he writes. He notes that It was British East India Company tea that patriots dumped into Boston harbor in 1773. American colonists were so grateful that the Mysore sultans tied up British forces that might have been deployed in America, they named a warship the Hyder Ali. Lord Cornwallis provides a connection, having surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown in 1781, an event confirming American independence, and turning up in 1786 in India as governor-general, taking Tipu Sultan’s surrender in 1792.

That reference raises an interesting side question that may someday deserve closer examination - Why were American colonists successful in driving off their British overlords. At the same time, Indian aristocracy and the masses over whom they ruled were unable to rid themselves of the British East India Company and the British Raj for another century?

No heroes emerge from Dalrymple’s expansive account that is rich, even overwhelming in detail. He covers two centuries but focuses on the period between 1765 and 1803 when the Company was transformed from a commercial operation to military and totalitarian — to use an appropriate term derived from Sanskrit - juggernaut. Among the multitude of characters involved in this sordid story are a few British names familiar in general history, Robert Clive of India, Warren Hastings, Lord Cornwallis, and Colonel Arthur Wellesley, who was better known long after he departed India as the Duke of Wellington. None - with the exception of Hastings - escape the scathing indictment of Dalrymple’s pen.

At the core of the story we meet Robert Clive, an emblematic character who from being a juvenile delinquent and suicidal lunatic rose to rule India, eventually killing himself in the aftermath of a corruption scandal. In particular Robert Clive comes in for much criticism by Dalrymple. After putting down one rebellion, Clive managed to send back £232 million, of which he personally received £22m. There was a rumour that, on his return to England, his wife’s pet ferret wore a necklace of jewels worth £2,500. Contrast that with the horrors of the 1769 famine: farmers selling their tools, rivers so full of corpses that the fish were inedible, one administrator seeing 40 dead bodies within 20 yards of his home, even cannibalism, all while the Company was stockpiling rice. Some Indian weavers even chopped off their own thumbs to avoid being forced to work and pay the exorbitant taxes that would be imposed on them. The Great Bengal famine of 1770 had already led to unease in London at its methods. “We have murdered, deposed, plundered, usurped,” wrote the Whig politician Horace Walpole. “I stand astonished by my own moderation,” Clive protested, after outrage intensified when the Company had to be bailed out by the British government in 1772. Clive took his own life in disgrace.

Warren Hastings, whom Dalrymple portrays as the more sensitive and sympathetic Company man, was first made governor general of India for 12 years and later endured seven years of impeachment for corruption before acquittal. Hastings showed “deep respect” for India and Indians, writes, Dalrymple, as opposed to most other Europeans in India to suck out as much as possible of the subcontinent’s resources and wealth. “In truth, I love India a little more than my own country,” wrote Hastings, who spoke good Bengali and Urdu, as well as fluent Persian. “(Edmund) Burke had defended Robert Clive (first Governor General of Bengal) against parliamentary enquiry, and so helped exonerate someone who genuinely was a ruthlessly unprincipled plunderer. Now he directed his skills of oratory against Warren Hastings (who was finally impeached), a man who, by virtue of his position, was certainly the symbol of an entire system of mercantile oppression in India, but who had personally done much to begin the process of regulating and reforming the Company, and who had probably done more than any other Company official to rein in the worst excesses of its rule,” Dalrymple writes. At his public impeachment hearing in 1788, Burke thundered: “We have brought before you…..one in whom all the frauds, all the peculation, all the violence, all the tyranny in India are embodied.’ They got the wrong man but, by the time he was cleared in 1795, the British state was steadily absorbing the Company, denouncing its methods but retaining many of its assets.

Dalrymple has a soft spot for a couple of Indian locals. “The British consistently portrayed Tipu as a savage and fanatical barbarian,” Dalrymple writes, “but he was in truth a connoisseur and an intellectual…” Of course, Tipu, Dalrymple confesses a bit later, had rebels’ “arms, legs, ears, and noses cut off before being hanged” as well as forcibly circumcising captives and converting them to Islam.

Emperor Shah Alam (1728-1806) is contemporary for much of the time Dalrymple covers. “His was…a life marked by kindness, decency, integrity and learning at a time when such qualities were in short supply…he…managed to keep the Mughul flame alive through the worst of the Great Anarchy….” Dalrymple portrays a most intriguing figure in Emperor Shah Alam, a man attracted to mysticism and yet as prepared as his contemporaries to double-deal; someone who endures exile and torture and who outlives, albeit in a melancholy fashion, his enemies. Despite his lack of wealth, troops or political power, the very nature of his being emperor still, it seems, inspired affection.

Part of Dalrymple’s excellence is in the use of Indian sources – he takes numerous quotes from Ghulam Hussain Khan, acclaimed by Dalrymple as “brilliant,” who threads the story as an 18th-century historian on his untranslated works, Seir Mutaqherin (Review of Modern Times). Dalrymple has used a trove of company documents in Britain and India as well as Persian-language histories, much of which he shares in English translation with the reader. However he does this a bit too often and portions of his account can seem more assembled than written.

These pages are also brimming with anecdotes retold with Dalrymple’s distinctive delight in the piquant, equivoque and gory: we have historical moments when “it seemed as if it were raining blood, for the drains were streaming with it” (quoted from a report c1740 regarding events that preceded Nadir Shah’s infamous looting of the peacock throne) as well as duels between Company officials so busy with their in-fighting that it’s a miracle they could perform their work at all; there’s also homosexuality, homophobia, sexual torture, castrations, cannibalism, brothels and gonorrhoea.

The principal protagonists of the “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident are both, naturally, certified pervs: Siraj ud-Daula is a “serial bisexual rapist” while his opponent Governor Drake is having an “affair with his sister”. And one particular Mughal governor liked to throw tax defaulters in pits of rotting shit (“the stench was so offensive, that it almost suffocated anyone who came near it”). All this gives one a rough idea of what historically important people were up to according to Dalrymple. But all things considered, Dalrymple’s research is solid and heavily annotated.

However entertaining and widely researched using unused Urdu and Persian sources, Dalrymple’s overall approach doesn’t tell us very much about the general tendency in eighteenth-century imperial activity, and particularly that of the British, that we didn’t already know. And other things he downplays or neglects. Thus, the East India Company was one of a series of ‘national’ East India companies, including those of France, the Netherlands and Sweden. Moreover, for Britain, there was the Hudson Bay Company, the Royal African Company, and the chartered companies involved in North America, as well, for example, as the Bank of England. Delegated authority in this form or shared state/private activities were a major part of governance. To assume from the modern perspective of state authority that this was necessarily inadequate is misleading as well as teleological. Indeed, Dalrymple offers no real evidence for his view. Was Portuguese India, where the state had a larger role, ‘better’?

Secondly, let us look at India as a whole. There is an established scholarly debate to which Dalrymple makes no ground breaking contribution. This debate focuses on the question of whether, after the death in 1707 of the mighty Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707), the focus should be on decline and chaos or, instead, on the development of a tier of powers within the sub-continent, for example Hyderabad. In the latter perspective, the East India Company (EIC) emerges as one and, eventually, the most successful of the successor powers. That raises questions of comparative efficiency and how the EIC succeeded in the Indian military labour market, this helping in defeating the Marathas in the 1800s.

An Indian power, the EIC was also a ‘foreign’ one; although foreignness should not be understood in modern terms. As a ‘foreign’ one, the EIC was not alone among the successful players, and was not even particularly successful, other than against marginal players, until the 1760s. Compared to Nadir Shah of Persia in the late 1730s (on whom Michael Axworthy is well worth reading), or the Afghans from the late 1750s (on whom Jos Gommans is best), the EIC was limited on land. This was part of a longstanding pattern, encompassing indeed, to a degree, the Mughals. Dalrymple fails to address this comparative context adequately.

Dalrymple seems particularly incensed at “corporate violence” and in a (mercifully short) final chapter alludes to Exxon and the United Fruit Company. Indeed Dalrymple has a pitch ” that globalisation is rooted here, albeit that “the world’s largest corporations…..are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company.”

It is an interesting question to ask: How might the actions of these corporate raiders have differed from those of a state? It’s not clear, for example, that the EIC was any worse than the average Indian ruler and surely these stationary bandits were better than roving bandits like Nader Shah. The EIC may have looted India but economic historian Tirthankar Roy explains that: “Much of the money that Clive and his henchmen looted from India came from the treasury of the nawab. The Indian princes, ‘walking jeweler’s shops’ as an American merchant called them, spent more money on pearls and diamonds than on infrastructural developments or welfare measures for the poor. If the Company transferred taxpayers’ money from the pockets of an Indian nobleman to its own pockets, the transfer might have bankrupted pearl merchants and reduced the number of people in the harem, but would make little difference to the ordinary Indian.”

Moreover, although it began as a private-firm, the EIC became so regulated by Parliament that Hejeebu (2016) concludes, “After 1773, little of the Company’s commercial ethos survived in India.” Certainly, by the time the brothers Wellesley were making their final push for territorial acquisition, the company directors back in London were pulling out their hair and begging for fewer expensive wars and more trading profits.

So also for eighteenth-century Asia as a whole. Dalrymple has it in for the form of capitalism the EIC represents; but it was less destructive than the Manchu conquest of Xinjiang in the 1750s, or, indeed, the Afghan destruction of Safavid rule in Persia in the early 1720s. Such comparative points would have been offered Dalrymple the opportunity to deploy scholarship and judgment, and, indeed, raise interesting questions about the conceptualisation and methodologies of cross-cultural and diachronic comparison.

Focusing anew on India, the extent to which the Mughal achievement in subjugating the Deccan was itself transient might be underlined, and, alongside consideration, of the Maratha-Mughal struggle in the late seventeenth century, that provides another perspective on subsequent developments. The extent to which Bengal, for example, did not know much peace prior to the EIC is worthy of consideration. It also helps explain why so many local interests found it appropriate, as well as convenient, to ally with the EIC. It brought a degree of protection for the regional economy and offered defence against Maratha, Afghan, and other, attacks and/or exactions. The terms of entry into a British-led global economy were less unwelcome than later nationalist writers might suggest. Dalrymple himself cites Trotsky, who was no guide to the period. To turn to other specifics is only to underline these points.

After Warren Hastings’ impeachment which in effect brought to an end the era when “almost all of India south of [Delhi] was…..effectively ruled by a handful of businessmen from a boardroom in the City of London.” It is hard to find a simple lesson, beyond Dalrymple’s point that talk of Britain having conquered India ‘disguises a much more sinister reality’.

One of the great advantages non-fiction has over fiction is that you cannot make it up, and in the case of the East India Company, you cannot make it up to an extent that beggars belief. William Dalrymple has been for some years one of the most eloquent and assiduous chroniclers of Indian history. With this new work, he sounds a minatory note. The East India Company may be history, but it has warnings for the future. It was “the first great multinational corporation, and the first to run amok”. Wryly, he writes that at least Walmart doesn’t own a fleet of nuclear submarines and Facebook doesn’t have regiments of infantry.

Yet Facebook and Uber does indeed have the potential power to usurp national authority - Facebook can sway elections through its monopoly on how people consume their news for instance. But they do not seize physical territory as Dalrymple states. Even an oil company with private guards in a war-torn country does not compare these days. This doesn’t exonerate corporations though. I know from personal experience of working in the corporate world that it attracts its fair share of psychopaths and cold blooded operators obsessed with the bottom lines of their balance sheets and the worship of the fortunes of their share prices and the lengths they go to would indeed come close to or cross over moral and legal lines. Perhaps the moral is to keep a stern eye on ‘corporate influence, with its fatal blend of power, money and unaccountability’. Clive reflected after Buxar, ‘We must indeed become Nabobs ourselves in Fact if not in Name…..We must go forward, for to retract is impossible.’ That was the nature of the beast.

Speaking of being beastly, some readers may disagree with the more radical views presented in taking apart the imperialist project and showed it for what it was - not about civilising savages, but about brutally exploiting civilised humans by treating them as savages. I think that’s partly true but not the whole story as Dalrymple will freely concede himself. Imperial history is a charged subject and they defy lazy Manichean conclusions of good guys and bad guys.

Dalrymple’s book is an excellent example of popular history - engaging, entertaining, readable, and informative. However, I honestly think he should have stuck to the history and not tried to draw out a trustbusting parallel with today’s big companies. Where the parallels exist, they are to do with cronyism, rent-seeking, and bailouts, all of which are primarily sins of government.

The Anarchy remains though a page-turning history of the rise of the East India Company with plenty of raw material to enjoy and to think about. To my mind the title ‘The Anarchy’ is brilliantly and appositely chosen. There are in fact two anarchies here; the anarchy of the competing regimes in India, and the anarchy – literally, without leaders or rules – of the East India Company itself, a corporation that put itself above law. The dangers of power without governance are depicted in an exemplary fashion. Dalrymple has done a great service in not just writing an eminently readable history of 18th century India, but in reflecting on how so much of it serves as a warning for our own time when chaos runs amok from those seeking to be above the law.

#treat your s(h)elf#books#review#reading#bookgasm#book review#history#east india company#william dalrymple#the anrchy#britain#colonialism#imperialism#british history#india#personal

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Company Men

Sir Howard Deighton Carr is a man with a heavy burden. He has been called to the stage to enact his part in the great drama of Destiny and defend the balance sheet of England.

This does not overly concern a man like Sir Howard, who has a way with destiny, since being a person of quality well used to such society, he has the advantage.

For destiny has erred. She has shown her petticoats

_____________________________________

Having completed the requisite education for a man of his position and status and having sought and gained the attachment of Gertrude at his mother’s urging, sir Howard joined the Company at the age of 25 and was sent as a Captain in the fourth to the land of the Hindus to earn his spurs in the wars that were then raging in that land.

He did not care for it.

The weather was abominable, the society worse and the food intolerable, on this as with a great variety of other matters – he concurred with the Duke.

He need not have concerned himself for he did not stay long. Within a remarkable short time of arriving Sir Howard proved himself to be an able enough soldier and an highly skilled expert administrator. He moved from battlefield to accounting house with ease and a degree of agreeableness that was not unremarked upon, and swiftly found himself noticed by the correct people for his character, his judgement and his cunning. As night follows day the orbits of the cosmos had aligned and placed Sir Howard in his proper sphere, as Deputy Director of the East India Company. The Company alas, had her misfortunes and Sir Howard, as the coming man, had been looked to as her saviour and champion.

For the Company, bastion of English commerce and trade had found herself in a rather delicate position.

She had never been truly solvent and the loss of the colonies, though there can be no rebukes aimed at Sir Howard on that score, left a hole in her balance sheet, that as a run in a stocking, must somehow be filled.

These are complex matters of state, but Sir Howard will attempt to simplify them for our understanding.

Some half century hence the Company, a true, solid English affair found that she had been cruelly handled by Dutch brigands – the details are not important suffice to say that the Dutch brigands in a most ungentlemanly manner were making plain to undermine the monopoly bestowed on said Company some years before. This left said Company in the unfortunate position of having spent a great deal of her fortune on Tea she could not sell.

Appealing as only a misfortunate can she turned to Parliament, as her St George to slay the dragon and valiant Parliament, accordingly answered the call. We shall not dwell on the particulars for they are painful still. In brief Parliament, in an unusual display of rational thinking suggested a transaction which would be of benefit to all.

For Parliament in the form of state affairs had at its disposal a ready supply of grateful consumers who would be only too willing to assist the Company with her indelicate affairs and promptly made arrangements by which, said Company would act as supply and grateful consumer would act as purchaser, for a very modest fee and a nominal levy, thereby alleviating the Company from its difficulties and removing the spectre of insolvency.

All would have proceeded excellently as planned were it not for an impertinent bunch of upstart radicals who, with no thought for the company’s position or the delicacies of a lady, determined that were they to agree to the levy they should likewise be consulted in Parliament’s affairs.

This was not to be borne.

The radicals then, lacking the Christian gratitude and manners of an Englishman proceeded to inform his majesty that he was no longer welcome in said colonies. Leaving said Company bereft of consolation and succour and in need regrettably, of safekeeping.

As has been said, the particulars are not important, but as Sir Howard takes his place on the stage the Company once again dear reader, finds itself in need of a protector and this time Parliament may not be quite so forthcoming.

But all is not lost, for Sir Howard, Knight of the realm, graduate of Harrow and Cambridge, scion of England, has applied his vast and angular mind to the problem and may have hit on a solution.

And like those distant ancestors who crossed into England with the Duke of Normandy – Sir Harold’s role now is to Conquer.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Of the Deputy Directors many responsibilities perhaps the most intransigent are those connected to Company policy, and in particular the need to press home the advantage already secured in a number of very promising locations in the East Indies. Some months past while the Deputy Director had been pondering on a most inexplicable problem, in an unexpected stroke of luck, a solution had presented itself to him as a revelation of divine wisdom.

Perusing, as was his practice in the mornings, the geological surveys of the various outposts under his command he had noticed attached to those from the East Indies a peculiarity contained in the report from that insufferable gentleman the Governor General of Kangalhi.

The oaf had included, quite by chance, a most valuable titbit, though he knew not its value, with regards to a local tribal chieftain and most impudent fellow who had assumed the manners of a gentleman and had denied the Company access! – one thinks of Boston and shudders.

This news had occasioned the Deputy to spring into action and immediately make further enquiries through various agents and networks whereby the upshot appeared that the tribal chieftain’s son and heir was himself gravely ill and in need of immediate medical treatment if he were to succeed his father and sit on the throne.

Although, as it appears, the child had been ailing from birth, it had recently been discovered that his suffering was as a result of a slow heart. Quite how this news had been discovered is anybody’s guess but the infant had in fact suffered from a number of symptoms for many years including fainting, dizziness, fatigue and tired so easily that at all times he was accompanied by one of his father’s men who would carry him to and fro.

When the Deputy director, enthroned in his leather-bound armchair behind his mahogany desk received the wondrous news he did not, as a lesser man might, engage in any theatrical displays of excessive enjoyment, he merely placed his palms on the desk, pushed back his well-oiled seat and smiled. For perhaps the first time of his recalling, since his dear mama had left him at the gates of Harrow as a child, the Deputy Director was truly happy.

For as luck would have it he and his dear wife Gertrude had attended a most tedious dinner some nights before when across from him and to the left of the hostess a wearisome gentleman of foreign extraction had proceeded to stupefy the company with a description of the new science from Germany. Perhaps unaware of the little regard those present had for his lecture the gentleman insisted on completing his soliloquy and although his mind was on other things, the information found its way into the Deputy’s cranium and waited there patiently, until it could be useful.

The science in question was the Crystalline process, whereby a substance extracted from a simple plant could be bent and twisted through a series of vials into an entirely separate thing through the manipulation of temperatures and the like, a breakthrough apparently, in both medicine and chemistry.

Having assessed and understood his advantage the Deputy rose from his chair and made haste to Lord Allam, the Director, and thus having unburdened his mind and received that excellent gentlemen’s full authority he summoned his man.

_______________________________________________________________

Major General Forester, who appreciated confidences, possessed little music in his soul, excepting that for his wife Prudence and his poor departed son Charles, and this had provided him with a singularity of purpose and peculiar rationality of mind which the Company now had need of.

He has been summoned by the Deputy Director to a discreet clandestine location in Pimlico, for a pre-arranged luncheon appointment of grave importance. This being one of a series of very fine luncheons by which the Major General and the Deputy Director are engaged in a series of mental gymnastics which might if handled correctly, prove most satisfactory.

“So, we’re agreed?”

“will it work?”

“Why shouldn’t it?........ worked with the Nazim”

For like a Camel through the eye of a needle, Sir Howard, the lancet of England, had found a way in.

________________________________________________________________

Little Billy Splicer, known to all but his mother as little billy was a child of unnatural talents, which had not yet had time to bloom.

In general, the boy was, by nature, slow to anger and quick to forgive, and for this reason alone his uncle had taken him back into his employ each time he had dismissed little Billy, who could be a bit rambunctious and had during his short vocation caused more than one diner to spill the aspic or drop the salt. And though his uncle could be a harsh man, on each occasion when he had been called to judge the prisoner at the bar, Uncle William, for whom little billy had been named, looked into the eyes of the sweet moon-faced boy and saw the visage of his dear departed, though not forgotten, sister for whose sake he had taken the boy. And quite unexpectedly, as in the way of things, young billy was paroled.

Billy had rewarded the kindness by developing into a performer of some little renown, for early in his employment he had noticed, when the restaurant was packed to bursting and others were busy at their tasks, three red-coated gentlemen enter when only two had been expected. Young William, who would later grace the stage at one of the future Prince of Wales’ favourite hunting grounds, being at heart, one of nature's natural pleasers, balanced chair and plate and bottle and gingerly made his way to the addition.

With all the natural magic of a conjurer in a masquerade, he made to appear in a flourish, the necessary comforts for the better settlement of the diners. Having entertained the company so, he received his first applause, for people who had witnessed his display made free to use the word marvel. Billy’s then natural shyness, which he would later lose, brushed off such unsought acclaim and dismissed the glory with a coy, “well, them’s fighting boys”.

This day however, young Billy’s countenance was decidedly fixed and he was fit to bursting, for two gentleman, whom he had seen once before, he could swear to it, sat at the best corner table with a full view of little Billy’s theatrics and had made no attempt to notice him or consider themselves pleased by his efforts.

When he had cleared the plates for the chops little Billy’s concerns grew for not only had the gentlemen shown Billy no acknowledgement, they had neither of them touched the fish and the Oysters had barely been troubled. Though little Billy had not had the benefit of Sir Howard’s education, although his dear ma had ensured he knew his letters, he understood this pretty plainly: people rarely visit restaurants to go hungry.

And so little Billy with small learning and great wisdom turned to uncle William and whispered under his breath:

“them’s conspirators”.

Alas, uncle William, whose main preoccupation at this time was ensuring the Jellies successfully slid from their moulds had little time for more of Billy’s japes.

“I’m telling you uncle, them’s conspirators. they are!”

“leave off, billy I’m busy”

“you ain’t too busy to know them’s conspirators”

“how can they be conspirators? them’s quality”

“so – quality can conspire can’t it?”

“nar, not toffs not when they’ve got those fine houses to live in – why’d they wanna go conspiring when they can just go home?”

Little Billy’s uncle, was Billy believed, a little too trusting of people on occasions. But little Billy ever watchful, lest it might enter the head of a patron to cheat his uncle and run off without covering the fare, resolved to take matters into his own hand and decided that he might just watch the gentleman more closely from now on, as he later conjectured “ ‘ncase they was conspirators and we gets in bovver with the magistrate, cause we never said nov’fing”

As matters transpired it was just as well that little Billy’s uncle William was more the forgiving type, for little Billy, more sage than savoury, had the tiger by the tail. The gentlemen were indeed conspirators, but it was hardly a matter for the magistrate.

___________________________________________________________________

The arrangements had been in place for some time.

Carr had, of course, already shared the geological studies and other notices with his companion with whom he had been actively engaged in a machination of some magnitude for almost three months. They had marvelled at the potential salt petre and iron ore reports each one showing that at the border of Kuru Par and Kul there were a considerable number of very fine mineral deposits of which salt pertre and iron ore appeared to be the most prolific. The Major General, when he had read the reports, had made liberty to exclaim “good lord, with that much salt petre we could have blown the French to Warsaw and been home for lunch!” The Major General had of course attended the Duchess’ ball the night before the battle and he had taken it as a personal affront to his dignity that the Corsican tinker could so trouble himself to bother the King’s Guard, saw at that moment the flag of st George flying over Versailles.

In later years when matters were more settled and the Major General and his dear wife Prudence, companion of his heart whose own mind was so wonderfully attuned to his own, were at leisure in their palatial bungalow, the official summer residence overlooking Lake Victoria, he would allow himself to be gently mocked by that sweet lady for his naivety. For he had not in that moment known what riches awaited them.

They had agreed, as conspirators do, to conduct their affairs apart from other business and at all costs not to involve the Director. There were of course more immediate matters to attend to, that oaf Harcourt, some pilfering, reports of drunkenness, concerns that some of the men might be taking off their peri wigs and redcoats of England and putting on the fez and the silk gown of Islam.

When Sir Howard reeled off the list of the Governor General's misdeeds his companion showed little concern, unlike Sir Howard, Forester was a General born, and in younger days had tramped the field with his men and on at least one occasion shared their bread. He understood that men far from home and away from the comfort of their wives and a stabilizing christian influence, could, if not properly drilled, fall into bad habits.

Then there was the company’s own business to see to and the company had made it clear that men who were taking to setting up their own concerns and trading on the company’s name whilst in uniform were in breach of Company policy, which fine tapestry of policy, Sir Howard, himself, had woven.

But these were not the abstract geometrical problems that had occupied the Chevalier’s existence for a major part of his tenure at the company and when he had shared his mind, as he rarely did with that excellent fellow the Major General at a house party last summer the Major General took an earthier view and reduce the equation down to a simple question, “I mean it’s obvious isn’t it?.....................How do you move a donkey?”

Like a dreamscape then, the answer unfolded in front of him, future member of both houses, like a five-fold path or a walk to Glory.

Since then, Sir Howard had sought desperately any ways in which the Company could be friendly to the Raja in a personal capacity, without success. So when that oaf, Harcourt the Governor General of Kangalhi, had let it slip that the Maharajah's baby boy was desperately ill, Sir Howard’s efficient lizard brain sprang into action.

For it was now possible, Sir Howard knew through his dear lady Gertrude, who suffered from the same ailments and conditions as the baby prince, to provide, if not a cure then relief to the sufferers, all thanks to a new treatment recently discovered in Germany, where Gertrude herself was at this very time taking the cure. Sir Howard’s analytically little mind, then surmised that if it were possible for the Company to arrange a similar solution to the immutable Indian chief’s benefit, well the immutable Indian chief, might be a little bit grateful and well-disposed to discuss terms.

His only concern was the Chemistry.

#my writing#creative writing#history#fictional history#india#new writing#new writing project#books#bookslr#booksblr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

In Game:

Woodes Rogers was an English privateer, the first royal governor of the Bahamas, and a member of the West Indies rite of the Templar Order, although he was eventually expelled for trading slaves.

In July of 1715, Woodes was with a handful of other Templars in Havana, expecting the arrival of Duncan Walpole, an Assassin traitor, who was to deliver a blood vial of a Sage, and maps of Assassin encampments throughout the West Indies. They were met instead with the pirate, Edward Kenway, who had killed Walpole and took his identity in a hope to gain the reward himself.

Woodes introduced Edward to Julien du Casse, a French arms dealer and a fellow Templar, and the Grand Master and governor, Laureano de Torres y Ayala. The four of them discussed how they would locate a First Civilization site known as the Observatory.

The Templars and Edward headed down to the docks to collect Bartholomew Roberts, a Sage who could lead them to the Observatory, and managed to fend off an assassin ambush. Afterward, Woodes returned to England in hopes of becoming a governor.

In 1718, Woodes returned to the Caribbean, having been appointed the governor of the Bahamas, to enforce British rule in Nassau. He offered pardon to the pirate leaders residing there, including Edward Thatch, Benjamin Hornigold, and Charles Vane, as well as ordering a blockade of Nassau by the Royal Navy, although Hornigold was the only one to accept the pardon. However, Edward Kenway and Charles Vane managed to escape Nassau after killing Woodes’ military associate, Commodore Peter Chamberlaine, who had intended to disregard Woodes' orders and sink every pirate vessel docked at Nassau.

Shortly after his affairs in Nassau, Woodes visited the Caicos Islands to deal with remaining pirates who had turned down the King's pardon. With a British war fleet under his command, he encountered two French pirates, who had just recovered an artifact known as the Fragment of Eden and, upon seeing Woodes' war fleet appear on the horizon, they decided to split up. In response to this, Woodes sent six of his vessels to attack. However, the pirates sank all ships, delaying the fleet to give his friend time to flee.

In 1719, Woodes was sent back to England by Torres, assigned to collect blood samples from members of the British Parliament, for eventual use when the Templars discovered the Observatory's location.

In 1721, Woodes accompanied Torres to Jamaica to interrogate Edward Kenway after his betrayal by Bartholomew Roberts and capture by British forces. As the men observed the sentencing of Mary Read and Anne Bonny, Woodes and Torres made what Edward perceived as veiled threats towards his estranged wife, Catherine Scott Kenway.

The Templars offered Edward a reprieve from imprisonment and likely execution in exchange for helping to lead them to the Observatory, with Torres warning Edward that Woodes could only block the British from executing him for a certain time. However, Edward was freed by the Assassins before the Templars could acquire the information they wanted from him.

Edward returned to Kingston later on that year, impersonating an Italian diplomat, Ruggiero Ferraro, to get into a party with the intent of confronting Woodes and killing him. Edward confronted him about the Templars' plans for the Observatory and demanded information regarding the Sage's location, to stop the pirate misusing that power. Woodes, amused that Edward would help the Assassins after they had tried to kill him, informed him of Roberts having been sighted on Príncipe, before supposedly succumbing to his wounds.

However, Woodes survived and returned to England, though he continued to trade slaves, which lead to his eventual expulsion from the Templar Order.

In Real Life:

Woodes Rogers was an English sea captain and privateer and, later on, the first Royal Governor of the Bahamas.

He was born around 1679 the eldest son and heir to Woods Rogers, a successful merchant captain. Woodes spent much of his childhood in Poole, England, where he likely attended the local school. His father, who owned shares in many ships, was often away for most of the year with the Newfoundland fishing fleet, leaving his son behind. His father would occasionally deal in human cargo as well.

Sometime between 1690 and 1696, Captain Rogers moved his family to Bristol, and in November of 1697, Woodes Rogers was apprenticed to Bristol mariner John Yeamans, so that he could learn how to be a sailor. At around age 18, Woodes was somewhat old to be starting a seven-year apprenticeship, on average. Nevertheless, he completed his apprenticeship around November 1704.

The following January after his apprenticeship was over, Woodes married Sarah Whetstone, daughter of Rear Admiral Sir William Whetstone, who was a neighbor and close family friend. Woodes became a freeman of Bristol because of his marriage into the prominent Whetstone family. In 1706, Captain Rogers died at sea, leaving his ships and business to his son Woodes. Between 1706 and the end of 1708, Woodes and Sarah Rogers had a son and two daughters.

Woodes owned four ships that were given letters of marque, which gave permission for them to attack and capture enemy ships that belonged to the French or Spanish. One of his ships, the Whetstone Galley, was captured on its way to Africa to capture slaves. Partly in response to this loss, Woodes lobbied his fellow merchants to fund an ambitious privateering

circumnavigation mission to raid Spanish shipping in the Pacific Ocean. He was placed in charge of two frigates, the Duke and the Duchess, both of which departed from Bristol on August 1st, 1708.

(Image source)

Woodes encountered many problems along the way. Forty people in his crew were deserted or were dismissed, and he spent a month in Ireland recruiting replacements and having the vessels prepared for sea. Many crew members were Dutch, Danish, or other foreigners. Some of the crew mutinied after Woodes refused to let them plunder a neutral Swedish vessel. When the mutiny was put down, he had the leader flogged, put in irons, and sent to England aboard another ship. The less culpable mutineers were given lighter punishments, such as reduced rations. They also had gone more south than they had intended, at their lowest point closer to the yet-to-be-discovered Antarctica than South America. However, of all of the problems that Woodes and his crew dealt with, he did have enough forethought to stock a large supply of limes to ward off scurvy, a practice that was not universally accepted at the time.

In 1709, the expedition captured and looted a number of small vessels, and launched an attack on the town of Guayaquil, today located in Ecuador. When Rogers attempted to negotiate with the governor, the townsfolk secreted their valuables. Woodes was able to get a modest ransom for the town, but some crew members were so dissatisfied that they dug up the recently dead hoping to find items of value. This led to sickness on board ship, of which six men died. The expedition lost contact with one of the captured ships, which was under the command of Simon Hatley. The other vessels searched for Hatley's ship, but to no avail—Hatley and his men were captured by the Spanish.

The crew of the vessels became increasingly discontented, and Rogers and his officers feared another mutiny. This tension was dispelled by the expedition's capture of a rich prize off the coast of Mexico: the Spanish vessel Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño. Woodes sustained a wound to the face in the battle from a Spanish musket ball; from then on, when painted or drawn, Woodes tended to be portrayed in profile to hide the disfigurement.

(Image source)

Upon his return to the British Isles, Woodes encountered financial problems on his return. Sir William Whetstone had died, and Woodes had failed to recoup his business losses through privateering. Thus, he was forced to sell his Bristol home to support his family. He was successfully sued by a group of over 200 of his crew, who stated that they had not received their fair share of the expedition profits. The profits from the book he published about his voyage were not enough to overcome these setbacks, and he was forced into bankruptcy. His wife gave birth to their fourth child a year after his return—a boy who died in infancy—and Woodes and Sarah Rogers soon permanently separated.

He decided that the best way to overcome his financial troubles would be to lead another expedition, this time against pirates. In 1713, Woodes led an expedition to purchase slaves in Madagascar and take them to the Dutch East Indies, this time with the permission of the British East India Company. However, Woodes' secondary purpose was to gather details on the pirates of Madagascar, hoping to either destroy or reform them, and colonize Madagascar on a future trip. Woodes collected information regarding pirates and their vessels near the island. Finding that a large number of the pirates had gone native, he persuaded many of them to sign a petition to Queen Anne asking her for clemency. While his expedition was profitable, when it returned to London in 1715, the British East India Company vetoed the idea of a colonial expedition to Madagascar, believing a colony was a greater threat to its monopoly than a few pirates. As such, Woodes turned his sights from Madagascar to the West Indies.

On January 5th, 1718, a proclamation was issued announcing clemency for all piratical offenses, provided that those seeking what became known as the "King's Pardon" surrendered not later than 5 September 1718. Colonial governors and deputy governors were authorized to grant the pardon. Woodes was officially appointed "Captain General and Governor in Chief" by King George I on January 6th, 1718. He was granted seven ships, 100 soldiers, 130 colonists, and supplies ranging from food for the expedition members and ships' crews to religious pamphlets to give to the pirates, whom Woodes believed would respond to spiritual or religious teachings.

The expedition arrived in the West Indies on July 22nd, 1718, surprising and trapping a ship that was captained by the pirate Charles Vane. After negotiations failed, Vane used a captured French vessel as a fireship in an attempt to ram the naval vessels. The attempt failed, but the naval vessels were forced out of the west end of Nassau’s harbor, giving Vane's crew an opportunity to raid the town and secure the best local pilot. Vane and his men then escaped in a small sloop via the harbor's narrow east entrance. The pirates had evaded the trap, but Nassau and New Providence Island were taken by Woodes.

Less than a month after Woodes had gained control of the island, Vane sent a letter to him threatening to retake the island with Edward Teach (better known as Blackbeard). There was also the constant threat of an invasion from Spain. He took out lots of loans trying to protect and fortify the island.

Woodes’ strategy was ultimately successful, ending the pirate republic and dispersing the remaining pirate gangs across the world with most of them ending up picked off, one by one. Nonetheless, he was fired from his

governorship in 1722 and wound up in prison for personal loans he took out to protect the colony from invasion. His reputation was restored after the publication of A General History of the Pyrates (1724), ultimately resulting in compensation from the crown and, in 1728, his restoration to the governorship of the Bahamas. He died in Nassau on July 15th, 1732.

Sources:

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/colonial/america-west-indies/vol30/pp359-381

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/4125577/Diaries-of-swashbuckling-hero-who-rescued-Robinson-Crusoe-unearthed.html

http://www.republicofpirates.net/Rogers.html

http://www.thepirateking.com/bios/rogers_woodes.htm

https://www.amazon.com/Crusoes-captain-Woodes-colonial-governor/dp/B0007IXYLC

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stock market guide

New Post has been published on http://moneymag.site/stock-market-guide/

Stock market guide

Stock market is an inquisitive place for many. It is because the place has given birth to many millionaires and is also responsible for turning millionaires to locals. Thus the bulls and bears have always been charismatic. Now millions of people invest in the stock market to make good money. The aura of the place is such that it is swarming with people any hour of the day and any season of the year. But only few know that how the stock market came into existence or what actually are its origins.

A short encounter with the past

The oldest stock certificate was issued in favor of a Dutch company in 1606. The purpose of this company was to benefit from the spice trade between India and the Far East. During the 18th and the 19th centuries the trade of spices drifted to England when Napoleon reigned over the place. With the development of United States of America as a colony to British and Alexander Hamilton (the first US secretary of the Treasury) flourished the American Stock Exchange. Hamilton played a crucial role in encouraging the trading in the Wall Street and Broad Street in New York. The New York Stock and Exchange Board now popularly known as the New York Stock Exchange was organized by the traders of New York in 1817 when trade and commerce bloomed there.

A precise survey of the Western stock market

The Wall Street- a place where the whole of 18th century trade and commerce took place, Wall Street is a recognized place across the globe. The street was termed as Wall Street since it ran alongside a wall that was taken as the northern boundary of New Amsterdam in 17th century.

The Wall Street is known for the J.P. Morgan’s million dollar merger that created US Steel Corporation, the ruinous crisis that resulted in Great Depression and the “Black Monday” of 1987.

The NYSE or the New York Stock Exchange is perhaps the foremost and so the oldest stock exchange in United States that is believed to be born in 1792. The significant aspects related to NYSE include the Buttonwood Agreement when 24 stockbrokers and traders of New York signed this accord and established the New York Stock Exchange and Securities Board which is now recognized as the NYSE; the considerable swings that the NYSE saw during the 20th and 21st century; the hitting of the 100 and later even 1000 mark by the Dow around 1971 and the mark of 10,000 that the Dow scaled in 1999.

NASDAQ is the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Questions. It is an apparent or virtual stock market where all trading is done through the electronic media. NASDAQ, the global and the largest electronic stock market today was first established in 1971 in United States at the time when computers were not as developed as they are today and it was very difficult to compute. The main exchange of NASDAQ is in United Sates while its branches can be found in Canada and Japan and it is also linked to markets of Hong Kong and Europe. NASDAQ functions by purchasing and selling the over- the- counter or OTC stocks.

AMEX-was discovered in 1842. The putative father of the institution is Edward Mc Cormick (the commissioner of SEC) who endowed it with its current name. It started its journey as the New York Curb Exchange and its name is factual. The AMEX in contrast to the NYSE operates with the small and more dynamic companies some of which even make it to the NYSE board.

0 notes

Text

Good stuff in 2016