#Upper Cretaceous fossil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A LARGE IRIDESCENT AMMONITE Canada

The 14-inch Placenticeras costatum from the upper Cretaceous, Bearpaw formation (75-72 million years ago), showing strong iridescences of red, orange, green and the rare color of purple, displayed on natural shale matrix. Specimen: 14 x 115⁄8in. (35.6 x 30cm.). In matrix: 257⁄8 x 32 x 41⁄8in. (65.8 x 81.2 x 10.5cm.).

#A LARGE IRIDESCENT AMMONITE#alberta canada#upper Cretaceous#Bearpaw formation#Placenticeras costatum#ammonite#gemstone#fossil#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient artifacts#pretty#beauty#beautiful#color#colorful#nature

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

the oldest known ant fossils date back to around 100 million years ago in the mid cretaceous and became 'ecologically dominant' around 60 million years ago. the current world population of ants is estimated to be between 10^15 and 10^16. worker ants tend to live 1-3 years, queens up to 30 years, but drones only a few weeks.

so... if we arbitrarily assume on average an ant lives for a year for ease of calculation, and that the ant population has been on average the same for the last 60 million years (unlikely, but we could imagine this is the inflection point of a logistic curve), we could estimate the number of ants to have lived in that period as between 6E22 and 6E23.

the upper bound of that is actually pretty close to avogadro's number! so we can say that the number of ants to have ever lived is roughly one mole

329 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently found out a show I liked is 10 years old now so to not be the oldest thing on this blog I'm talking coelacanths for Wet Beast Wednesday. Coelacanths are rare fish famed for being living fossils. While that term is highly misleading, it is true that coelacanths are among the only remaining lobe-fined fish and were thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago before being rediscovered in modern times.

(image id: a wild coelacanth. It is a large, mostly grey fish with splotches of yellowish scales. Its fins are attached to fleshy lobes. It is seen from the side, facing the top right corner of the picture)

Coelacanth fossils had been known since the 1800s and they were believed to have gone extinct in the late Cretaceous period. That was until December 1938, when a museum curator named Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was informed of an unusual specimen that had been pulled in by local fishermen. After being unable to identify the fish, she contacted a friend, ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith, who told her to preserve the specimen until he could examine it. Upon examining it early next year, he realized it was indeed a coelacanth, confirming that they had survived, undetected, for 66 million years. Note that fishermen living in coelacanth territory were already aware of the fish before they were formally described by science. Coelacanths are among the most famous examples of a lazarus taxon. This term, in the context of ecology and conservation, means a species or population that is believed to have gone extinct but is later discovered to still be alive. While coelacanths are among the oldest living lazarus taxa, they aren't the oldest. They are beaten out by a genus of fly (100 million years old) and a type of mollusk (over 300 million years old).

(image: a coelacanth fossil. It is a dark brown imprint of a coelacanth on white rock. Its skeleton is visible in the imprint)

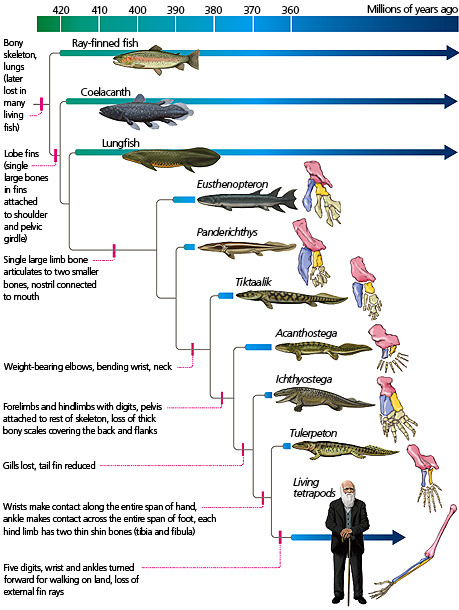

Coelacanths are one of only two surviving groups of lobe-finned fish along with the lungfishes. Lobe-finned fish are bony fish notable for their fins being attached to muscular lobes. By contrast, ray-finned fish (AKA pretty much every fish you've ever heard of that isn't a shark) have their fins attached directly to the body. That may not sound like a big difference, but it actually is. The lobes of lobe-finned fish eventually evolved into the first vertebrate limbs. That makes lobe-finned fish the ancestors of all reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, including you. In fact, you are more closely related to a coelacanth than a coelacanth is to a tuna. Coelacanths were thought to be the closest living link to tetrapods, but genetic testing has shown that lungfish are actually closer to the ancestor of tetrapods.

(image id: a scientific diagram depicting the taxonomic relationships of early lobe-finned fish showing their evolution to proto-tetrapods like Tiktaalik and Ichthyostega, to true tetrapods. Source)

There are two known living coelacanth species: the west Indian ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (L. menadoensis). Both are very large fish, capable of exceeding 2 m (6.6 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lbs). Their wikipedia page describes them as "plump", which seems a little judgmental to me. Their tails are unique, consisting of two lobes above and below the end of the tail, which has its own fin. Their scales are very hard and thick, acting like armor. The mouth is small, but a hinge in its skull, not found in any other animal, allows the mouth to open extremely wide for its size. In addition, they lack a maxilla (upper jawbone), instead using specialized tissue in its place. They lack backbones, instead having an oil-filled notochord that serve the same function. The presence of a notochord is the key characteristic of being a chordate, but most vertebrates only have one in embryo, after which it is replaced by a backbone. Instead of a swim bladder, coelacanths have a vestigial lung filled with fatty tissue that serves the same purpose. In addition to the lung, another fatty organ also helps control buoyancy. The fatty organ is large enough that it forced the kidneys to move backwards and fuse into one organ. Coelacanths have tiny brains. Only about 15% of the skull cavity is filled by the brain, the rest is filled with fat.

(image id: a coalacanth. It is similar to the one on the above image, but this one is blue in color and the head is seen more clearly, showing an open mouth and large eye)

One of the reasons it took so long for coelacanths to be rediscovered is their habitat. They prefer to live in deeper waters in the twilight zone, between 150 and 250 meters deep. They are also nocturnal and spend the day either in underwater caves or swimming down into deeper water. They typically stay in deeper water or caves during the day as colder water keeps their metabolism low and conserves energy. While they do not appear to be social animals, coelacanths are tolerant of each other's presence and the caves they stay in may be packed to the brim during the day. Coelacanths are all about conserving energy even when looking for food. They are drift feeders, moving slowly with the currents and eating whatever they come across. Their diet primarily consists of fish and squid. Not much is known about how they catch their prey, but they are capable of rapid bursts of speed that may be used to catch prey and is definitely used to escape predators. They are believed to be capable of electroreception, which is likely used to locate prey and avoid obstacles. Coelacanths swim differently than other fish. They use their lobe fins like limbs to stabilize their movements as they drift. This means that while coelacanths are slow, they are very maneuverable. Some have even been seen swimming upside-down or with their heads pointed down.

(image: an underwater cave wilt multiple coelacanths residing in it. 5 are clearly visible, with the fins of others showing from offscreen)

Coelacanths are a vary race example of bony fish that give live birth. They are ovoviviparous, meaning the egg is retained and hatches inside the mother. Gestation can take between 2 and 5 years (estimates differ) and multiple offspring are born at a time. It is possible that females may only mate with a single male at a time, though this is not confirmed. Coelacanths can live over 100 years and do not reach full maturity until age 55. This very slow reproduction and maturation rate likely contributes to the rarity of the fish.

(image: a juvenile coelacanth. Its body shape is the same as those of adults, but with proportionately larger fins. There are green laser beams shining on it. These are used by submersibles to calculate the size of animals and objects)

Coelacanths are often described as living fossils. This term refers to species that are still similar to their ancient ancestors. The term is losing favor amongst biologists due to how misleading it can be. The term os often understood to mean that modern species are exactly the same as ancient ones. This is not the case. Living coelacanth are now known to be different than those who existed during the Cretaceous, let alone the older fossil species. Living fossils often live in very stable environments that result in low selective pressure, but they are still evolving, just slower.

(image: a coelacanth swimming next to a SCUBA diver)

Because of the rarity of coelacanths, it's hard to figure out what conservation needs they have. The IUCN currently classifies the west Indian ocean coelacanth as critically endangered (with an estimated population of less than 500) and the Indonesian coelacanth as vulnerable. Their main threat is bycatch, when they are caught in nets intended for other species. They aren't fished commercially as their meat is very unappetizing, but getting caught in nets is still very dangerous and their slow reproduction and maturation means that it is long and difficult to replace population losses. There is an international organization, the Coelacanth Conservation Council, dedicated to coelacanth conservation and preservation.

(image: a coelacanth facing the camera. The shape of its mouth makes it look as though it is smiling)

#wet beast wednesday#coelacanth#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#fish#fishblr#old man fish#lobe-finned fish#sarcopterygii

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Chondrichthyes - Chimaeriformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3, 4)

Our last order in Chondrichthyes is Chimaeriformes, commonly known as “Chimaeras”, and informally known as “ghost sharks”, “spookfish”, “rabbitfish”, or “rat fish” (not to be confused with the Actinopterygiian “rattails”.) Historically a much more diverse and abundant group, they now only comprise the living families Callorhinchidae (“plough-nosed chimaeras” or “elephantfish”), Chimaeridae (“short-nosed chimaeras”), and Rhinochimaeridae (“long-nosed chimaeras”).

Chimaeras are soft-bodied, with bulky heads and long, tapered tails. Their pectoral fins are large enough to generate lift at a relaxed forward momentum, similar to a kite, giving the chimaera the appearance of "flying" through the water. Their gill arches are condensed into a pouch-like bundle covered by an operculum with a single gill-opening in front of the pectoral fins, similar in appearance to Actinopterygiians. They lack spiracles. There are two dorsal fins: a large triangular first dorsal fin and a low rectangular or depressed second dorsal fin. For defense, some chimaeras have a venomous spine on the front edge of the dorsal fin. In many species, the bulbous snout is modified into an elongated sensory organ, capable of electroreception to find prey. Instead of many sharp, consistently-replaced teeth, chimaeras have just six large, permanent tooth-plates, which grow continuously throughout their entire life. These tooth-plates are arranged in three pairs, with one pair at the tip of the lower jaws and two pairs along the upper jaws. They together form a protruding, beak-like crushing and grinding mechanism, comparable to the incisor teeth of rodents and lagomorphs. Most living species are native to the deep sea, with some species inhabiting depths exceeding 2,000 m (6,600 ft) deep, though the few exceptions include the shallower-dwelling plough-nosed chimaeras (genus Callorhinchus) (image 2), the Rabbit Fish (Chimaera monstrosa), and the Spotted Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) (image 3).

Chimaeras have separate anal and urogenital openings, rather than a single cloaca. Like sharks and rays, male chimaeras utilize claspers for internal fertilization of females, but unlike sharks and rays, also have retractable sexual appendages known as tentacula to assist in mating. The frontal tentaculum, a bulbous rod which extends out of the forehead, is used to clutch the females' pectoral fins during mating. The prepelvic tentacula are serrated hooked plates normally hidden in pouches in front of the pelvic fins, and they anchor the male to the female. Their claspers are fused together by a cartilaginous sheathe before splitting into a pair of flattened lobes at their tip. Females lay their eggs within spindle-shaped, leathery egg cases which they deposit on the sea floor.

As the most ancient of the Chondrichthyans, Chimaeriformes are truly deserving of the moniker “living fossil”. They have been around since the Early Carboniferous, with the earliest known fossil species being Protochimaera, and split off from the sharks and rays during the Devonian. Modern chimaeras are known from the Early Jurassic, but fossil egg cases from the Late Triassic resembling those of rhinochimaerids and callorhinchids indicate that they had a global distribution earlier than this. Modern chimaeras reached their highest ecological diversity during the Middle Cretaceous. Recent studies indicate that chimaeras were likely a shallow-water group for most of their existence, and only fled to deeper waters in the aftermath of the K-Pg extinction event, adapting to the deep sea to survive.

Propaganda under the cut:

Some chimaera venom can cause pain, necrosis, hallucinations, and localized paralysis in humans. It is not deadly to humans, but has been known to kill Harbor Seals that injested Spotted Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei).

Spotted Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) have large, emerald green eyes, which are able to reflect light, similar to the eyes of a cat.

Chimaera teeth are unique among vertebrates, due to their mode of mineralization. Most of each plate is formed by relatively soft osteodentin, but the active edges are supplemented by a unique hypermineralized tissue called pleromin, rather than enamel. Pleromin is an extremely hard enamel-like tissue, arranged into sheets or beaded rods, but it is deposited by mesenchyme-derived cells similar to those that form bone. In addition, pleromin's hardness is due to the mineral whitlockite, which crystalizes within the teeth as the animal matures.

The Australian Ghostshark (Callorhinchus milii) is very popular with fish-and-chips restaurants in New Zealand and is sold as 'flake' or 'whitefish' in Australia.

The Striped Rabbitfish (Hydrolagus matallanasi) can see in total darkness and sense electromagnetic radiation (outside of the visible spectrum) emitted by other marine creatures due to exposed nerves on the sides of its body.

Some species of chimaerids are known to segregate by sex, with females congregating at greater depths than males.

Despite their deep sea habitat and reclusive nature, some chimaera species are still threatened by bycatch due to deep sea trawling for demersal shrimp and prawns. Even when released, most chimaeras do not survive the process of being quickly pulled up from the pressurized deep sea to shallower water.

#description a bit longer than usual because they’re so unlike all the other members of the class#animal polls#round 3#chondrichthyes

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Croc Paleontology Recap January 2025

The year has just begun and already we got a bunch of pretty neat new studies on fossil pseudosuchians so I'll just briefly go over them and unless I forget or end up procrastinating/getting too busy I'll hopefully be able to keep this going throughout the rest of the year.

Just to give you a brief overview, the highlights of this month include: salt glands in gavialoids, crocodilian predation on azhdarchids, diversifications and extinctions in thalattosuchians and a new species of aetoaur from India. Lets begin.

Evidence for salt glands in gavialoids

Starting off with something relating to the dispersal of gavialoids, we got "Evaluation of the endocranial anatomy of the early Paleogene north African gavialoid crocodylian Argochampsa krebsi and evolutionary implications for adaptation to salinity tolerance in marine crocodyliforms" by Pliggersdorfer, Burke and Mannion.

The title already gives a lot away, but the point was that Argochampsa, from the early Paleocene Ouled Abdoun Basin in Morocco, was examined for evidence of salt tolerance. Why? Because the dispersal of gavialoids remains weird. Both modern forms aren't especially keen on saltwater and are only known to consistently occur in freshwater (tho we have a recent example of an indian gharial caught in a fishing net off the coast of India), yet we have plenty of extinct gavialoids that either indicate that the group must have crossed oceans (see any "gryposuchine") or straight up lived at sea (also see some "gryposuchines").

Now, one such example might also be Argochampsa. Both because the Ouled Abdoul Basin famously preserves coastal deposits and because, at least following some phylogenies, Argochampsa might be closely related to the gharials of South America and today (others say its not even a gavialoid but lets ignore that for now). So all things considered one might expect marine habits from Argochampsa, yet so far no such adaptations could be identified. Well, Pliggersdorfer and co. analyzed a thus-far undescribed skull and actually managed to find something. Small depressions on the inside of the skull are suspiciously similar to ones seen in the extinct, fully marine metriorhynchoids, depressions that in the latter have been interpreted as having been left by salt glands. There is also some further evidence through the morphology of the inner ear.

This conclusion further extends to a handfull of other taxa, including the dyrosaurid Rhabdognathus and the recently named gavialoid Sutekhsuchus, and lends itself to the hypothesis that salt glands may have been ancestral to gavialoids, something I personally find unsurprising given their proximity to crocodyloids and their dispersal across the world (really if anything alligatoroids seem like the odd one out).

Fun fact, yours truly is featured in the paper in the form of two silhouettes.

Left: Argochampsa, illustrated by Seismic Shrimp/JW Right: Piscogavialis, perhaps the most famous marine gavialoid, illustrated by Joschua Knüppe

The brain of Paralligator

Second on our neat little list, the neuroanatomy of Paralligator, studied through CT scans and 3D modeling and published on in "Neurocranial anatomy of Paralligator (Neosuchia: Paralligatoridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Given that I am not great with brain things, I'll keep this one short.

Now for those unfamiliar, Paralligator is part of a somewhat strange clade known as the Paralligatoridae, which contrary to their name are nowhere near real alligators (tho some do look deceptively similar). Instead, they are much more basal members of Eusuchia.

Measurements of the olfactory bulbs, responsible for the sense of smell, indicate that in Paralligator this sense was similarily developed to allodaposuchids and crocodilians, as is the inner ear who's anatomy suggests a semi-aquatic lifestyle. Paralligator does however differ in possessing a mesothemoid, a bony septum in the olfactory region that is also seen in dyrosaurids, baurusuchids and dinosaurs, but not modern crocodiles.

Borealosuchus remains from Colorado

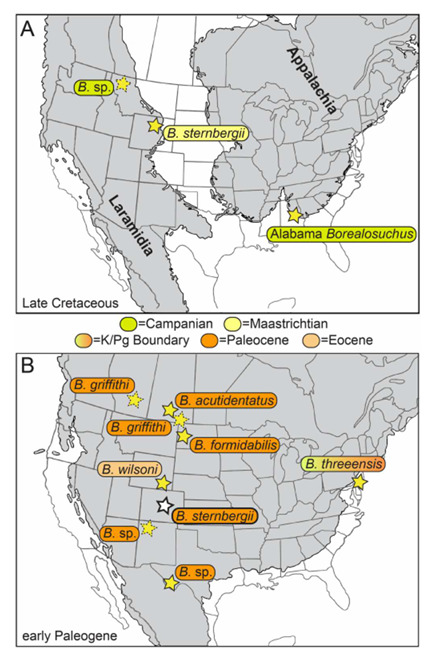

Tho seemingly unexciting, this study, "First record of Borealosuchus sternbergii from thelower Paleocene Denver Formation (lower Danian),Colorado (Denver Basin)" actually helps us fill a neat little gap in our previous knowledge on croc survival across the Cretaceous-Paleocene extinction.

Simply put, though America's croc record across the KPG is rather remarkable, showing both many survivors and some incredible diversification after the impact, Colorado is kind of a blind spot, despite its potential importance. Perhaps one of the best examples of a survivor concerns the genus Borealosuchus, which is both geographically and stratigraphically widespread. To put things into perspective, this genus occured as far north as Canada and as far south as Texas, first appearing in the Late Cretaceous and dying out in the Eocene.

This paper now described several skulls from the Corall Bluff's locality of the Denver Formation, earliest Paleocene, that can be attributed to Borealosuchus sternbergii, definitively extending its range beyond KPG (granted, there are tentatively referred Paleocene occurences elsewhere), making it one of the largest suvivors of the mass extinction, with adults growing up to 2.3 meter in length. The specimens from Colorado are smaller, in the 1.5 to 1.7 meter range, but they are also regarded as immature individuals and are therefore also regarded as usefull in illustrating how the animals changed as they grew into adulthood.

This paper is especially well timed for those that follow @knuppitalism-with-ue 's Formation Stream series. As you might know, Corall Bluffs is to be drawn barely a week from now and this is a fantastic addition.

Left: Borealosuchus drawn by Atak_Draws Right: Distribution of Borealosuchus by Lessner, Petermann and Lyson 2025

Growth of a peirosaur

Our next paper for discussion is "Life history and growth dynamics of a peirosaurid crocodylomorph (Mesoeucrocodylia; Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina inferred from its bone histology" by Tamara G. Navarro and colleagues. This study conducted the first histology of peirosaurid limb bones, specifically of an indetermined taxon clading together with Uberabasuchus.

As a brief refresher, peirosaurids are a branch of medium to large sized Notosuchians that I personally think can be aptly described as appearing somewhat like scaly dogs or pigs with often robust, wedge-shaped heads and heavily armored bodies.

The results show that the animal had reached sexual maturity, yet was not yet fully grown. What's also noted is the exact growth dynamics of this animal. This is to say, the studied peirosaurid had overall slow growth with cycles of no growth whatsoever and two periods of increased growth, tho once put against other notosuchians the study deems the growth rates to be better described as "moderate". Pepesuchus meanwhile, belonging to the closely related itasuchids, was a fast grower. Extending things beyond their shared clade shows a virtual mish-mash of dynamics, with Araripesuchus buitreraensis displaying slow growth rates (yet Araripesuchus wegeneri having faster rates than the peirosaur), Iberosuchus showing slow rates, and Notosuchus displaying high growth rates (hell, theres even variation between individuals). A final point concerns the age of the individual, which is....contradictory. Based on the limb bones, the study estimates that the animal was at the very least 15 years old, but previous study of the osteoderms has yielded an estimated age of 18 years old. Ultimately, further study is needed, but it does clearly show how the histology of different parts of the skeleton varies.

Shown below, Uberabasuchus terrificus by Scott Reid

Predation on pterosaurs

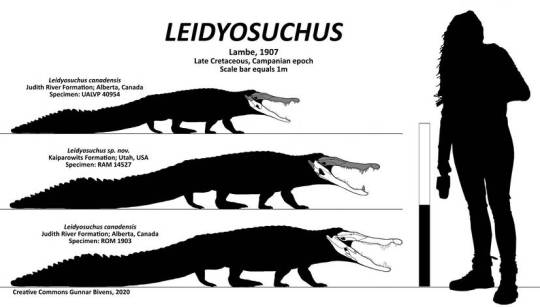

Here's a fun one, "A juvenile pterosaur vertebra with putative crocodilian bite from the Campanian of Alberta, Canada", once again with a name that tells you very much what you're in for.

Brown and colleagues report on the discovery of a juvenile specimen of the azhdarchid Cryodrakon from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada. The neck vertebra bears some conical bite marks, notably different from those of theropods, which generally have D-shaped or compressed tooth crosssections (sans spinosaurids, which aren't present). Champsosaurus is also ruled out due to its inferred feeding preferences, weak bite force and slender teeth. Mammals are potential candidates, but the team regards it as more likely that the trace maker was a crocodilian. Considering the fauna of the Dinosaur Park Formation, this would suggest the culprit was either Leidyosuchus, Albertochampsa or an animal described as "Stangerochampsa-like".

Now this is a very interesting, if not exactly unexpected interaction. On the one hand, having direct fossil evidence for this is a big deal, even if we don't know if the bite marks were left due to the pterosaur being actively hunted or if they were simply left when a lucky croc came across the carcass of an already deceased Cryodrakon. On the other hand, crocodiles and kin are notoriously opportunistic and broad in their diet, so one feeding on a pterosaur is something that seems like a no-brainer in principle, especially a relatively small individual with a wingspan of "only" 2 meters. This is further supported by the fact that crocodilian bite marks have also been reported from the Romanian pterosaur Eurazhdarcho.

Obvious difference in prey size and geography aside (and taxon names even within the chosen setting while we're on it), Prehistoric Planet really nailed the nailon the head with this one.

In the left corner, a juvenile Cryodrakton (art by Hank Sharpe). In the right corner, Leidyosuchus (art by Gunnar Bivens) LET THEM FIGHT (or scavenge)

Evolutionary trends and extinctions in Thalattosuchia

This one's a last minute entry, by which I mean this one got just published as I was about to wrap this whole thing up. "Analysing Thalattosuchia palaeobiodiversity through the prism of phylogenetic comparative methods" explores how the evolution and the extinctions of members of this group were shaped by both biotic and abiotic factors.

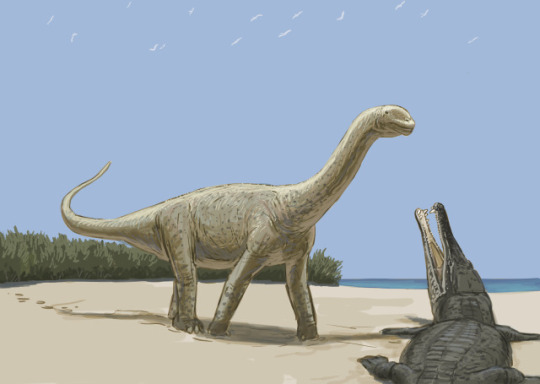

Given the shere breadth of this topic, a quick summary of thalattosuchia seems kinda in order. In short, thalattosuchians are a group of what are likely to be early crocodyliforms adapted to life at sea. They can be split into two groups, the teleosauroids, superficially gharial like animals that likely stuck to coastal waters, and the metriorhynchoids, open ocean animals with fluked tails, no body armor and paddle-like limbs. Both groups reached their greatest diversity in the late Jurassic, but managed to survive into the Cretaceous before disappearing entirely.

The study recaps that thalattosuchians first reach great diversity during the Toarcian, tho this is likely influenced by preservation bias thanks to Lagerstätten such as the Posidonia shale, and a later diversification takes place during the Bathonian. Regardless, the transition from the lower to middle Jurassic sees an increased trend in both thalattosuchian groups towards shorter snouts, which are associated with durophagy or hypercarnivory. This essentially gives rise to the teleosauroids of the Machimosaurinaei, which appear during the Bathonian and have blunt, robust teeth, as well as the metriorhynchoid Geosaurinae, which appeared at the same time and had ziphodont (serrated teeth). The reasons for this could be twofold. On the one hand, thalattosuchians were very abundant, so expanding into new nisches helped them coexist, with ecosystems preserving fish-eaters, hypercarnivores, durophages and more at the same time. More of an underlying factor could be a drop in ichthyosaur diversity, leaving plenty of open nisches for these crocs to fill.

Subsequently, during the transition from the Middle to Late Jurassic, there was another diversification event with both groups establishing new major clades, possibly associated with the warm temperatures of the Late Jurassic, before the diversity crashes with the onset of the Cretaceous. The authors note that this too might have been related to climate, with the Cretaceous survivors mostly being found in warmer waters.

Left: A Dakosaurus ambushing an ichthyosaur by Gabriel Ugueto Right: A large Machimosaurus rests on the beach as a sauropod approaches, art by Joschua Knüppe

and for the final study I wanna talk about

Kuttysuchus: A new Aetosaur from India

Now, by all accounts one might be surprised to see this just kinda thrown in at the end here rather than getting a dedicated post as I usually like to do with new forms. And truth be told, theres just not that much to say about "A New paratypothoracin aetosaur (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the Upper Triassic Dharmaram Formation of India and its biostratigraphic implications".

Kuttysuchus is our first pseudosuchian to be described this year and to get things out of the way, its not super exciting in terms of material. Like some other recently named aetosaurs, Kuttysuchus is based entirely on a handfull of osteoderms. And there's nothing wrong with that, after all osteoderms are rather distinctive for these animals. It does however mean that the information we can get from them is a bit limited and thus makes it hard to really put together something engaging.

More interesting than the anatomy then is the range and its relationship to other aetosaurs. The fossils are known from the Dharmaram Formation of India, which you might recall is also home to the recently named Venkatasuchus. Both Venkatasuchus and Kuttysuchus are members of the Paratypothoracini, tho the former is significantly more derived and the latter more basal.

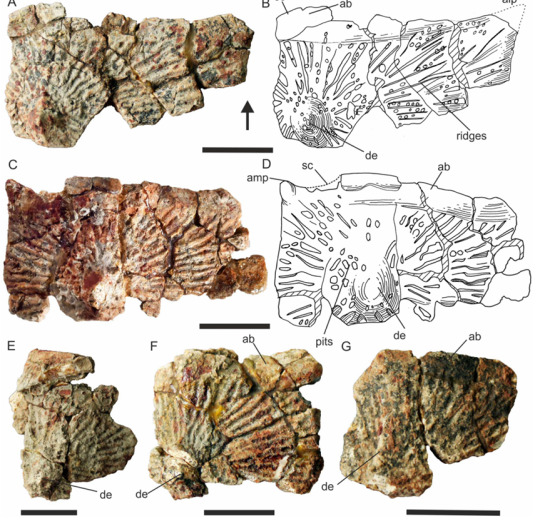

Fossil osteoderms of Kuttysuchus, all belonging to the central double row that stretches across the back.

I'll be entirely honest. This was a lot more work to type out than anticipated, but admittedly also fairly rewarding. Hopefully you dear reader found it equally interesting, and hey, congrats on making it to the end.

#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#croc#crocodile#long post#pseudosuchia#sutekhsuchus#argochampsa#peirosauridae#thalattosuchia#metriorhynchoidea#teleosauroidea#kuttysuchus#aetosauria#paralligator#leidyosuchus#cryodrakon#borealosuchus

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Navaornis hestiae Chiappe et al., 2024 (new genus and species)

(Type skull of Navaornis hestiae [scale bar = 10 mm], from Chiappe et al., 2024)

Meaning of name: Navaornis = [discoverer of the original fossil and the site where it was found] William Nava's bird [in Greek]; hestiae = for Hestia [Greek goddess of architecture]

Age: Late Cretaceous (Santonian–Campanian)

Where found: Adamantina Formation, São Paulo, Brazil

How much is known: A nearly complete skull. Some associated bones from the rest of the skeleton likely belong to the same individual. A partial braincase from the same locality probably comes from a different individual of the same species.

Notes: Navaornis was an enantiornithean, a group of bird-like, usually flight-capable dinosaurs from the Cretaceous. It is one of a handful of enantiornitheans known to have been toothless, giving its skull a superficial resemblance to those of modern birds. However, Navaornis was unlike modern birds (and more like typical non-bird dinosaurs) in the proportions of the bones making up its upper jaw and the lack of a mobile joint in its palate.

The skull of Navaornis is so well preserved that the overall shape and structure of its brain can be reconstructed, a first for an enantiornithean. Similar to birds today, its brain was arched so that its brainstem pointed somewhat downward instead of backward, and the main part of the brain devoted to cognition was relatively enlarged (though not to the same extent as in modern birds). On the other hand, its cerebellum (part of the brain involved in coordinating movement) was relatively small. An especially unusual feature of Navaornis was its greatly enlarged inner ear, the functional significance of which is unknown.

Reference: L.M. Chiappe, G. Navalón, A.G. Martinelli, I. de Souza Carvalho, R.M. Santucci, Y.-H. Wu, and D.J. Field. 2024. Cretaceous bird from Brazil informs the evolution of the avian skull and brain. Nature 635: 376–381. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08114-4

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS A WIP @a-dinosaur-a-day recently made this great text post that i put in the middle here. My idea when i saw the post was to use it for an embroidery piece and i am collecting some ideas here (and also wait for eir approval before going forth because obviously the quote is not mine) So my thoughts are: - quote in the middle, using either this font (easy to cross-stitch) or a different one, has yet to be determined. - dinosaur fossil amid Cretaceous (or from an earlier period) plants on upper half of the circle. i kind of would like to create a fading effect with the dead dino being both visibly fossilised, as in stylised bones, but also with its feathers being visible. will probably use satin stitch for all of this. - flying bird on bottom half (my mock-up shows a macaw but maybe i'll change that too). i have this vague concept of connecting their tails via a trail of loose feathers but since i am Like That i will do some research to what we know about early feathers first. - in order to close the circle, i am thinking about adding some contemporary plants that have a resemblance to ancient ferns etc. to the right half. not sure about that yet though. All in all, this is the most ambitious embroidery project i'll do as of now. my embroidery so far has all been premade pattern-based and mostly cross stitch, so this will be a learning curve. however, i am looking forward to doing this :)

279 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm back again for DINOSAUR FACT TIME!! Rules are the same as before!

The fact for today is: The Falcarius (meaning "sickle cutter"), is a theriznosaur that lived in the early Cretaceous and was discovered by fossil collector Lawrence Walker in Grand County, Utah. They were discovered in a mass fossil graveyard of sorts with hundreds of the species being clumped in a single area. Adults were usually 4-5 meters (13-16 feet) in length and weighed around 100kg (220 lbs). They held approximately 16 teeth in their upper jaw and 28 in the lower, which they used to consume a (supposedly according to their dental records in comparison to other species) mix of foliage, fruit, and some small lizards!!

I hope you enjoyed this installment of dinosaur fact time! :]

Oh this is so cool!!! I love therizinosaurus-es [therizinosauri?] a lot :3

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

An ammonite fossil of an Vascoceras tectiforme from the Upper Cretaceous deposits in Gombe, Nigeria. This species is also referred to as Paramammites tectiforme, though the validity of this genus is not clear.

#ammonite#cephalopod#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#vascoceras#paramammites#vascoceratidae#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#バスコセラス#パラマンミテス#バスコセラス科#アンモナイト#化石#古生物学

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spinosaurus, equipped with aquatic adaptations like crocodile-like jaws, webbed feet, has led some researchers to propose that it was predominantly an aquatic predator rather than a terrestrial one.

📹 : Julian Johnson-mortimer / Julian_johnson12345

—

Spinosaurus is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the Cenomanian to Upper Turonian stages of the Late Cretaceous period, about 99 to 93.5 million years ago.

The genus was first known from Egyptian remains discovered in 1912 and described by German palaeontologist Ernst Stromer in 1915.

The original remains were destroyed in World War II but additional material came to light in the early 21st century.

It is unclear whether one or two species are represented in the fossils reported in the scientific literature.

Spinosaurus, which was longer and heavier than Tyrannosaurus, is the largest known carnivorous dinosaur.

It possessed a skull 1.75 metres (roughly 6 feet) long, a body length of 14–18 metres (46–59 feet), and an estimated mass of 12,000–20,000 kg (13–22 tons).

#Spinosaurus#spinosaurid dinosaur#Late Cretaceous period#Ernst Stromer#carnivorous dinosaur#dinosaurs#paleontology#fossils

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

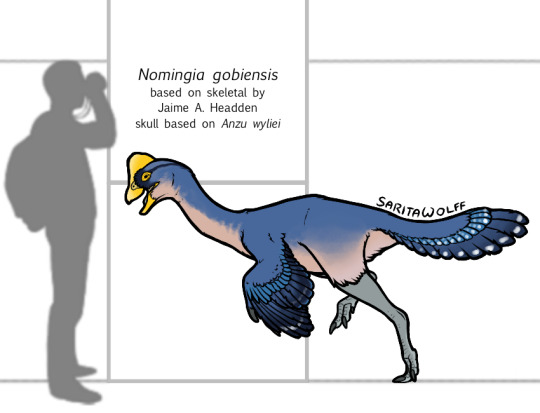

The gracile caenagnathids are notorious for fossilizing badly, and as such Nomingia gobiensis is only known from its spine, upper legs, and tail (which is honestly more than most other caenagnathids). However, its tail represents a significant discovery for oviraptorosaurs. Nomingia had five fused vertebrae at the tip of its tail, a structure similar to the pygostyle of birds, that would have supported a fan of tail feathers. When Nomingia was found in 1994 and described in 2000, this feature was thought to be unique to birds. And while we have evidence of tail fans in other oviraptorosaurs, pygostyles themselves are rare. It’s unknown why Nomingia would have needed this, as it was certainly too big for flying. Perhaps, like Khaan’s tail fan, it was used for display, and the structure would have allowed it to have a sturdier, larger, more “sexy” tail fan.

As of 2021, it has been suggested that Nomingia may actually be Elmisaurus, but further study is needed to confirm this. Since caenagnathid fossils tend to be so fragmentary, this may take some time.

Hailing from the Bügiin Tsav and Nemegt localities of Mongolia’s Late Cretaceous Nemegt Formation, Nomingia would have lived alongside Avimimus nemegtensis in this seasonally arid environment characterized by cliffs, shallow lakes, and patches of conifer forests. If not Elmisaurus itself, it would have lived alongside it as well as the oviraptorids Nemegtomaia in the Nemegt and Oksoso in the Bügiin Tsav. There were of course other dinosaurs here, including Therizinosaurus, the troodontid Tochisaurus, the tyrannosaur Bagaraatan, the sauropod Nemegtosaurus, the hadrosaur Barsboldia, and the pachycephalosaur Homalocephale in the Nemegt.

In the Bügiin Tsav, Nomingia would have lived alongside the troodontid Zanabazar, the dromaeosaur Adasaurus, the bird Brodavis, the ornithomimosaurs Anserimimus and Deinocheirus, and the alvarezsaur Mononykus.

It would have come across Gallimimus, the hadrosaur Saurolophus, the pachycephalosaur Prenocephale, and the tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus in both localities. Crocodylomorphs like Paralligator, fish like Harenaichthys, and turtles could be found in the freshwater lakes.

This art may be used for educational purposes, with credit, but please contact me first for permission before using my art. I would like to know where and how it is being used. If you don’t have something to add that was not already addressed in this caption, please do not repost this art. Thank you!

#Nomingia gobiensis#Nomingia#caenagnathid#oviraptorosaurs#theropods#saurishcians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Nemegt Formation#Late Cretaceous#Mongolia

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The newly-described species belongs to Ferussina, a small extinct genus of land snails known from the Paleogene period of Europe. The genus is currently classified in its own family, Ferussinidae, in the superfamily Cyclophoroidea. Named Ferussina petofiana, the new species lived during the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous epoch, some 72 million yeas ago. “Ferussina was until now recorded only from Paleogene (Middle Eocene to Upper Oligocene and maybe to Upper Miocene) deposits of Western Europe (France, Germany, Switzerland, northern Italy),” said Dr. Barna Páll-Gergely from the HUN-REN Centre for Agricultural Research and colleagues. “The new species is the oldest, as well as the easternmost representative of its genus.”

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

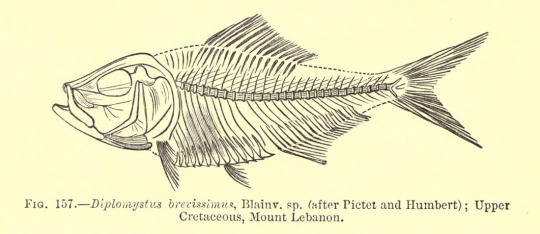

Upper Cretaceous fossil fishes from A Guide to the Fossil Reptiles and Fishes in the Department of Geology and Paleontology in the British Museum (Natural History), 1896.

Rhinellus fercatus has since been recombined as Ichthyotringa furcata, per paleobiodb.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 3 - Reptilia - Phaethontiformes

(Sources - 1, 2, 3)

Our next order is Phaethontiformes, commonly known as “tropicbirds”. This is a small order, containing one living family, Phaethontidae, and three species within one genus: Phaethon.

Tropicbirds have predominantly white plumage with long, slender tail streamers which can be up to twice their body length. All four of their toes are connected with webbing. Their legs are small and weak, located far back on their body, making walking impossible, so they can only move on land by shuffling. Their bills are large, powerful and slightly downcurved. Tropicbirds frequently catch their prey by hovering and then plunge-diving, typically only into the surface-layer of the water. They eat mostly fish, especially flying fish (family Exocoetidae), and occasionally squid. Flying fish are usually caught in the air. They live on the open ocean, nesting on remote, rocky cliffs, or on offshore islands.

Tropicbirds are usually solitary or live in pairs in breeding colonies. Within breeding colonies, they engage in spectacular courtship displays. For several minutes, groups of 2–20 birds simultaneously and repeatedly fly around one another in large, vertical circles, while swinging their tail streamers from side to side. If the female likes the presentation of a male, she will join his flight display, and the pair will split off from the group to do a courtship display together. The pair will mate in the male’s prospective nest-site, usually a hole or crevice on the bare ground. The female will lay one white egg, which is spotted brown. Both parents incubate the egg, but mostly the female, while the male brings food to feed her. The chick will stay alone in the nest while both parents search for food, and they will feed the chick twice every three days until fledging, about 12–13 weeks after hatching. The parents will stop visiting the chick after it has fledged, and the chick will leave the nest on its own.

Tropicbirds are in the clade Eurypygimorphae, along with Eurypygiformes (“kagus” and “Sunbittern”). Tropicbirds were a very early branch of this clade, with well-preserved fossils known from the Early Paleocene. One waterbird, Novacaesareala hungerfordi, dates to the Late Cretaceous. If it is a tropicbird, that could put the origin of this order before the K-Pg extinction. Modern tropicbirds evolved in the Early Eocene.

(source)

Propaganda under the cut:

One of the Red-billed Tropicbirds’ (Phaethon aethereus) (image 1 and gif) aerial courtship displays involve a prospective pair gliding together, with one bird around 30 cm (12 in) above the other. The upper bird bends its wings down and the lower lifts its up, so they are almost touching. The two descend to about 6 meters (20 ft) above the sea before breaking off.

The ancient Chamorro People of the Mariana Islands called the White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus) (image 3) utak or itak, and believed that when it screamed over a house it meant that someone would soon die or that an unmarried girl was pregnant. Its call would kill anyone who didn't believe in it.

The Red-billed Tropicbird, a bird not native to Bermuda, was displayed in error on the $50 Bermudian dollar and was replaced in 2012 by the White-tailed Tropicbird, the tropicbird that can be found in Bermuda.

The Red-tailed Tropicbird’s (Phaethon rubricauda) (image 2) red tail streamers were highly prized by the Maori. The Ngāpuhi tribe of the Northland Region would look for and collect them off dead or stray birds blown ashore after easterly gales, trading them for greenstone with tribes from the south.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

High in Coahuila, Mexico, a newly uncovered dinosaur sporting unusually extended forelimbs has been declared a “Mexican dragon.” Scientists say this bizarre species, some 73 million years old, offers further proof of Mexican dinosaurs’ remarkable but under-appreciated diversity.

Surprising New Find In Mexico

Mexico has emerged as a hotbed for unexpected dinosaur discoveries. The most recent addition to the roster is Mexidracon longimanus, dubbed by researchers as the “long-handed Mexican dragon.” It belongs to the ornithomimid or “ostrich-mimic” group, a clan of theropods famed for toothless beaks and slender, fast-running forms.

The first clue that Mexidracon wasn’t just another ostrich mimic? It’s unbelievably elongated metacarpals. The dinosaur’s slim palm bones made its hands exceed the length of its upper arms, which points to unique ways it found food. The forelimbs resembled present-day tree sloths, leading scientists to think it used such extended arms to collect plants for eating. Alternatively, some propose that this dino’s multi-jointed grasp might have been perfect for fishing in muddy waters, a scenario that fits the sedimentary environment brimming with oysters and other marine fauna.

Paleo-enthusiasts know that most of Mexico’s dinosaur finds date only to the 21st century. The roster includes horned ceratopsians, duck-billed hadrosaurs, and imposing tyrannosaurs. Each new genus emphasizes that the region’s Late Cretaceous habitats produced specialized lineages distinct from their northern counterparts in the U.S. or Canada. Such differences could point to partial geographic isolation that led to separate evolutionary paths.

The surface details also support the idea that Coahuila had pockets of rich biodiversity, possibly including wetlands or estuary-like ecosystems. That might explain why Mexidracon bones come from strata associated with watery deposits. If it inhabited marshy edges, those long arms may have assisted in rummaging through reeds or capturing small aquatic prey. Fragments from the same site reveal an environment dense with shellfish—an indicator that these dinosaurs likely contended with brackish shallows and migrating fish.

Odd And Extinct: Ornithomimid Lore

Ornithomimids—literally “bird mimics”—constitute a family of lightly built, bipedal dinosaurs with ostrich-like proportions, minus the feathers. Fossil impressions from Canada confirm that many sported a feathery coat, though whether that extended to flamboyant plumage remains unclear. Typically, these creatures possessed toothless beaks and were reputedly omnivorous, feeding on everything from leaves to small invertebrates. Unlike T. rex or raptors, they would not have been top predators. Instead, they roamed the land for fruit, seeds, insects, or maybe smaller reptiles, employing agility and speed to elude carnivores.

But “Mexidracon longimanus” sets itself apart with its uncommonly proportioned arms. The name “longimanus,” meaning “long-handed,” is apt, given that the palm alone outmatches the entire upper arm in length. Similar but less exaggerated builds in other ornithomimids prompted evolutionary debates: Did they rummage in trees or drag branches down to munch leaves? Could they have had a partial wading lifestyle, snapping up small fish? Despite theories, paleontologists seldom find direct evidence of feeding from fossilized intestines or last meals. Claws can hold clues: If robust or hooked, they might have aided in gleaning fruits or hooking small creatures.

To complicate matters, some have compared these elongated limbs to the arms of modern-day sloths—an apt analogy if the dinosaur’s joints and claws were adapted for snagging overhead vegetation or water prey. This radical shape diverges from the simpler designs in older or more typical “ostrich mimics,” suggesting unique ecological roles in the watery environment. Paleontologists think specialized foraging might have made Mexidracon a partial outlier among its broader group.

Seventy-Three Million Years Ago: Coahuila’s Cretaceous Scene

Geologically, the strata that entombed Mexidracon date to around 73 million years old, firmly placing it in the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. At that time, vast shallow seas covered North America, leaving silt and sandy deposits brimming with marine creatures. Coahuila’s fossil trove, primarily discovered in the last two decades, has yielded an impressive variety of dinosaurs. These finds might eventually rival those in U.S. or Canadian badlands, rewriting the typical narrative that big, showy dinosaur species only roamed further north.

The presence of big hadrosaurs in Coahuila, plus local tyrannosaurids, suggests robust ecosystems, complete with migratory herbivores and apex predators. That Mexidracon thrived in watery margins is unsurprising, given how many dinosaur bones in Mexico are in brackish or nearshore contexts. The environment also explains the shell accumulations, leading to speculation that Mexidracon scavenged from tidepools or devoured tiny marine organisms on the muddy banks.

Such adaptability speaks volumes about how these creatures lived. They weren’t solely farmland roamers or pure forest dwellers: They were opportunists, taking advantage of coastal edges to feed on aquatic or semi-aquatic resources. That’s a far cry from how we often imagine “ostrich mimic” dinosaurs as land-lubbers. If more skeletons of this species or similar forms come to light, paleontologists can refine theories about how they hunted or gathered food.

Future Of Mexican Dino Discoveries

Morphological oddities like enormous metacarpals invite more profound evolutionary questions. Why are these elongated arms in a group typically known for quickness and minimal weaponry? Did the dinosaur face competition from other herbivores, prompting it to exploit resources in the treetops or shallow waters? Or was it a specialized fisher? Paleo-art and speculation are sure to flourish. Imaginative reconstructions already feature a small, lithe dinosaur wading in an estuary, arms extended like multi-pronged spears to snatch unsuspecting fish—be it romantic or purely hypothetical- underscores how morphological adaptation shapes survival strategies.

Beyond Mexidracon, the region’s trove includes some horned dinosaurs akin to Triceratops, crested hadrosaurs resembling the likes of Parasaurolophus, and fearsome predatory lineages, plus distinctly local forms that never ventured north. Each discovery cements the notion of a partial “Mexican province” in Late Cretaceous times, cut off enough from northern neighbors to evolve distinct species. That perspective redefines how we see North American dinosaur biogeography.

Looking ahead, paleontologists hope for more complete skeletons or, ideally, a well-preserved skull for Mexidracon. A more finished blueprint might confirm if its muzzle shape or crest variation (if any) influenced its feeding. The impetus rests on local field teams: Each year, advanced mapping, high-resolution imaging, and improved excavation methods uncover once-hidden remains in the region’s chalky rock layers.

Mexico is forging its identity as a cradle of improbable and specialized species. If the “Mexican dragon” stirs enough curiosity, it might become a local icon, spurring further hunts for the next big find.

While “Mexidracon” evokes dramatic imagery of a scaly beast, it’s grounded in credible scientific data. Those who imagine flamboyant sails or spines might be disappointed; the real appeal is the dinosaur’s improbable arms. Yet the richly varied environment it inhabited and the abiding puzzle of how it used those limbs keep the find in the public eye. Combined with Mexico’s rising star in paleontology, the “long-handed Mexican dragon” seems set to fascinate dinosaur enthusiasts and casual observers for years to come.

Ultimately, Mexidracon helps bridge a gap: modern knowledge about large, fast-living ostrich mimics in North America rarely touched on the possibility of watery habitats, specialized arms, or little-known southern lineages. By unveiling what might be a genuinely one-of-a-kind adaptation, Mexico reminds us that dinosaur evolution is more complex and varied than previous narratives suggested. At 73 million years old, the “long-handed Mexican dragon” reaffirms that entire corners of dinosaur history lie waiting in the rocky countryside—and that each surprising clue can broaden our horizons about life in Earth’s distant past.

#🇲🇽#mexico#animal#dinosaur#Coahuila#AOM#mexicdracon#Mexidracon longimanus#long-handed Mexican dragon#paleontology#usa#united states#canada#ornithomimid#ostrich-mimic#Late Cretaceous#shellfish#insect#reptile

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Koleken inakayali Pol et al., 2024 (new genus and species)

(Maxillae [bones in the upper jaw] of Koleken inakayali [scale bar = 5 cm], from Pol et al., 2024)

Meaning of name: Koleken = from clay and water [in Teushen, referring to the fact that the original fossil was found in claystone]; inakayali = for Inakayal [one of the last chiefs of Tehuelches]

Age: Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian)

Where found: La Colonia Formation, Chubut, Argentina

How much is known: Partial skeleton of one individual including parts of the skull, spine, and hindlimbs.

Notes: Koleken was an abelisaurid ceratosaur, making it a close relative of genera like Carnotaurus and Aucasaurus. In fact, it is known from the same rock formation as Carnotaurus, so the two may have lived alongside one another. Like other abelisaurids, Koleken had rough patches on the top and sides of its skull that may have corresponded to a keratin covering in life, though unlike Carnotaurus, it did not have prominent horns on the top of its head.

Based on microscopic examination of its bone structure, the type specimen of Koleken was not fully grown when it died, which raises the possibility that it represents a juvenile individual of Carnotaurus. However, the describers of Koleken consider the two more likely to be distinct species, because they differ in details of the skull, vertebrae, and hindlimbs that are unlikely to have changed so dramatically during growth.

Reference: Pol, D., M.A. Baiano, D. Černý, F.E. Novas, I.A. Cerda, and M. Pittman. 2024. A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the end Cretaceous of Patagonia and evolutionary rates among the Ceratosauria. Cladistics advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/cla.12583

84 notes

·

View notes