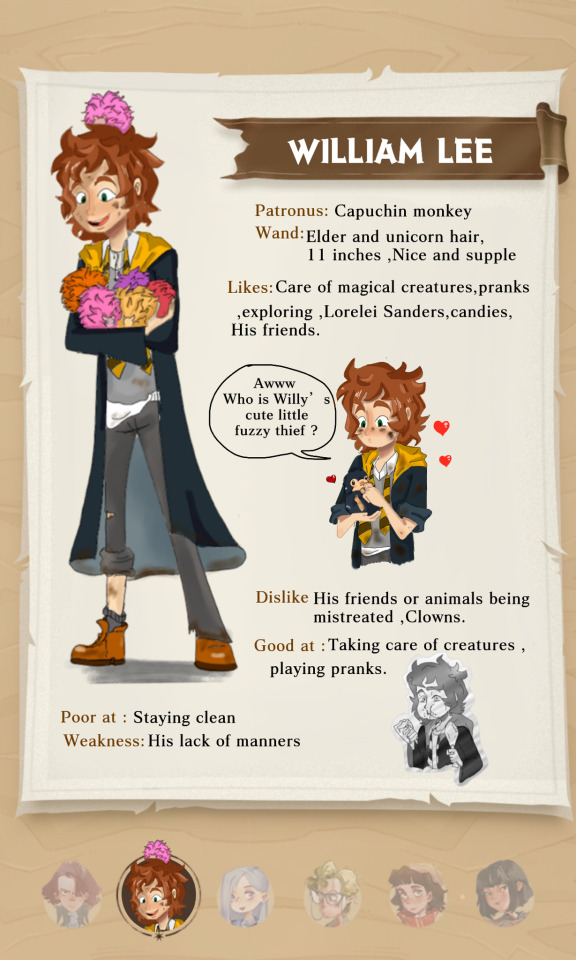

#William lee

Text

I basically don't have the energy for a full drawing so here's a The Family™ sketch collection

#I have historically been terrible at faces and expressions so mostly this is me working on that but also#m tired#amrev#I am absolutely not tagging all of these people so here are the greatest hits#alexander hamilton#john laurens#marquis de lafayette#benjamin tallmadge#william lee#I am entering my college student shitpost era#consider this a warning#art tag

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valentine-day 💌💖🌷💋

William Lee and Lorelei Sanders ( called WillLori XD idea of my friend @chirithy564 )

Isn't that warm and beautiful with watercolor?

#harry potter#oc#harry potter oc#hpoc#harry potter magic awakened#hpma oc#harrypotteroc#magic awakened#william lee#lorelei sanders#oc x oc#valentines day#harry potter ocs#hp ocs#my ocs

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

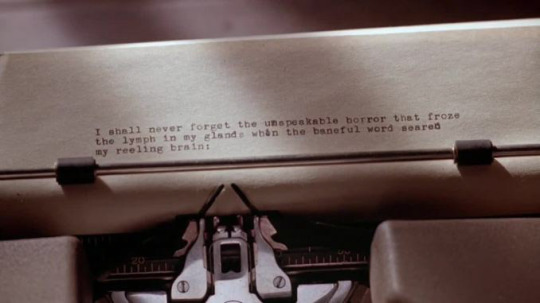

n a k e d l u n c h, 1991 🎬 dir. david cronenberg 'The Zone Takes Care of Its Own'

#film#naked lunch#naked lunch 1991#david cronenberg#peter weller#julian sands#Michael Zelniker#Nicholas Campbell#Robert A. Silverman #william lee#Yves Cloquet#Hank#Martin#Hans#The Zone Takes Care of Its Own

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite their modern reputation, the original Luddites were neither opposed to technology nor inept at using it. Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry. Nor was the technology they attacked particularly new. Moreover, the idea of smashing machines as a form of industrial protest did not begin or end with them. In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say they were good at branding.

The Luddite disturbances started in circumstances at least superficially similar to our own. British working families at the start of the 19th century were enduring economic upheaval and widespread unemployment. A seemingly endless war against Napoleon’s France had brought “the hard pinch of poverty,” wrote Yorkshire historian Frank Peel, to homes “where it had hitherto been a stranger.” Food was scarce and rapidly becoming more costly. Then, on March 11, 1811, in Nottingham, a textile manufacturing center, British troops broke up a crowd of protesters demanding more work and better wages.

That night, angry workers smashed textile machinery in a nearby village. Similar attacks occurred nightly at first, then sporadically, and then in waves, eventually spreading across a 70-mile swath of northern England from Loughborough in the south to Wakefield in the north. Fearing a national movement, the government soon positioned thousands of soldiers to defend factories. Parliament passed a measure to make machine-breaking a capital offense.

But the Luddites were neither as organized nor as dangerous as authorities believed. They set some factories on fire, but mainly they confined themselves to breaking machines. In truth, they inflicted less violence than they encountered. In one of the bloodiest incidents, in April 1812, some 2,000 protesters mobbed a mill near Manchester. The owner ordered his men to fire into the crowd, killing at least 3 and wounding 18. Soldiers killed at least 5 more the next day.

Earlier that month, a crowd of about 150 protesters had exchanged gunfire with the defenders of a mill in Yorkshire, and two Luddites died. Soon, Luddites there retaliated by killing a mill owner, who in the thick of the protests had supposedly boasted that he would ride up to his britches in Luddite blood. Three Luddites were hanged for the murder; other courts, often under political pressure, sent many more to the gallows or to exile in Australia before the last such disturbance, in 1816.

One technology the Luddites commonly attacked was the stocking frame, a knitting machine first developed more than 200 years earlier by an Englishman named William Lee. Right from the start, concern that it would displace traditional hand-knitters had led Queen Elizabeth I to deny Lee a patent. Lee’s invention, with gradual improvements, helped the textile industry grow—and created many new jobs. But labor disputes caused sporadic outbreaks of violent resistance. Episodes of machine-breaking occurred in Britain from the 1760s onward, and in France during the 1789 revolution.

As the Industrial Revolution began, workers naturally worried about being displaced by increasingly efficient machines. But the Luddites themselves “were totally fine with machines,” says Kevin Binfield, editor of the 2004 collection Writings of the Luddites. They confined their attacks to manufacturers who used machines in what they called “a fraudulent and deceitful manner” to get around standard labor practices. “They just wanted machines that made high-quality goods,” says Binfield, “and they wanted these machines to be run by workers who had gone through an apprenticeship and got paid decent wages. Those were their only concerns.”

So if the Luddites weren’t attacking the technological foundations of industry, what made them so frightening to manufacturers? And what makes them so memorable even now? Credit on both counts goes largely to a phantom.

Ned Ludd, also known as Captain, General or even King Ludd, first turned up as part of a Nottingham protest in November 1811, and was soon on the move from one industrial center to the next. This elusive leader clearly inspired the protesters. And his apparent command of unseen armies, drilling by night, also spooked the forces of law and order. Government agents made finding him a consuming goal. In one case, a militiaman reported spotting the dreaded general with “a pike in his hand, like a serjeant’s halbert,” and a face that was a ghostly unnatural white.

In fact, no such person existed. Ludd was a fiction concocted from an incident that supposedly had taken place 22 years earlier in the city of Leicester. According to the story, a young apprentice named Ludd or Ludham was working at a stocking frame when a superior admonished him for knitting too loosely. Ordered to “square his needles,” the enraged apprentice instead grabbed a hammer and flattened the entire mechanism. The story eventually made its way to Nottingham, where protesters turned Ned Ludd into their symbolic leader.

The Luddites, as they soon became known, were dead serious about their protests. But they were also making fun, dispatching officious-sounding letters that began, “Whereas by the Charter”...and ended “Ned Lud’s Office, Sherwood Forest.” Invoking the sly banditry of Nottinghamshire’s own Robin Hood suited their sense of social justice. The taunting, world-turned-upside-down character of their protests also led them to march in women’s clothes as “General Ludd’s wives.”

They did not invent a machine to destroy technology, but they knew how to use one. In Yorkshire, they attacked frames with massive sledgehammers they called “Great Enoch,” after a local blacksmith who had manufactured both the hammers and many of the machines they intended to destroy. “Enoch made them,” they declared, “Enoch shall break them.”

This knack for expressing anger with style and even swagger gave their cause a personality. Luddism stuck in the collective memory because it seemed larger than life. And their timing was right, coming at the start of what the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle later called “a mechanical age.”

People of the time recognized all the astonishing new benefits the Industrial Revolution conferred, but they also worried, as Carlyle put it in 1829, that technology was causing a “mighty change” in their “modes of thought and feeling. Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand.” Over time, worry about that kind of change led people to transform the original Luddites into the heroic defenders of a pretechnological way of life. “The indignation of nineteenth-century producers,” the historian Edward Tenner has written, “has yielded to “the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers.”

The original Luddites lived in an era of “reassuringly clear-cut targets—machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer,” Loyola’s Jones writes in his 2006 book Against Technology, making them easy to romanticize. By contrast, our technology is as nebulous as “the cloud,” that Web-based limbo where our digital thoughts increasingly go to spend eternity. It’s as liquid as the chemical contaminants our infants suck down with their mothers’ milk and as ubiquitous as the genetically modified crops in our gas tanks and on our dinner plates. Technology is everywhere, knows all our thoughts and, in the words of the technology utopian Kevin Kelly, is even “a divine phenomenon that is a reflection of God.” Who are we to resist?

The original Luddites would answer that we are human. Getting past the myth and seeing their protest more clearly is a reminder that it’s possible to live well with technology—but only if we continually question the ways it shapes our lives. It’s about small things, like now and then cutting the cord, shutting down the smartphone and going out for a walk. But it needs to be about big things, too, like standing up against technologies that put money or convenience above other human values. If we don’t want to become, as Carlyle warned, “mechanical in head and in heart,” it may help, every now and then, to ask which of our modern machines General and Eliza Ludd would choose to break. And which they would use to break them.

#history#labour#employment#capitalism#exploitation#technology#textiles#folklore#industrial revolution#luddites#britain#england#ned ludd#william lee#thomas carlyle#elizabeth i#weaving#knitting#stocking frame

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

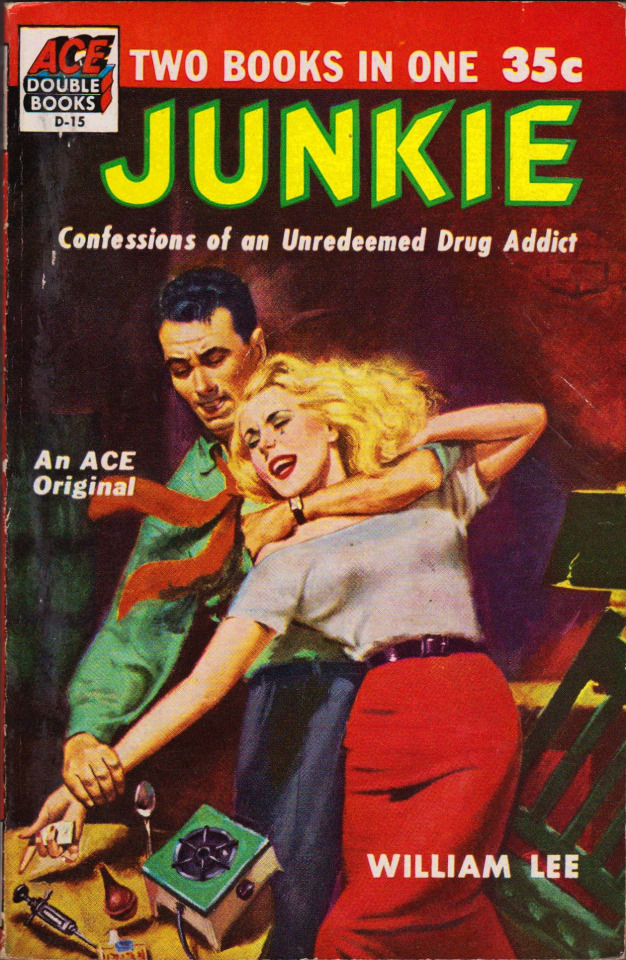

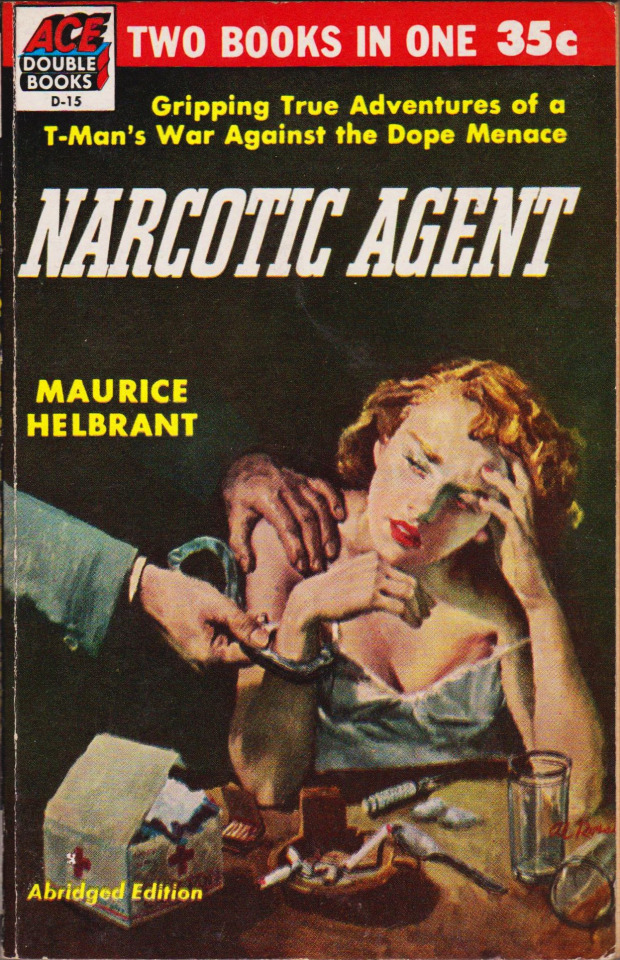

William S. Burroughs first book, published as a paperback original back to back with Narcotic Agent by Maurice Helbrant

#pulp#william s burroughs#narcotic agent#maurice helbrant#ace books#pulp cover#vintage paperbacks#william lee#pseudonym

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“For Nova Express is nothing if not an analysis of and tribute to the apocalyptic power of The Word.”

— Nova Express, William S. Burroughs

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Published in November 1985, though originally written in the early '50s, Burroughs' book centres on William Lee, a gay drug addict drifting from bar to bar in Mexico City, subsisting on GI benefits and paychecks from part-time jobs. “As Lee breaks down, the trademark Burroughsian voice emerges; a maniacal mix of self-lacerating humour and the Ugly American at his ugliest,” reads an official blurb. “A haunting tale of possession and exorcism, Queer is also a novel with a history of secrets.”

#growing realisation : yes excited about the movie#ReaLLy excited for the press tours#looking forward to learn from guadagnino dc + starkey about the story + characters#this haunting tale of possession + exorcism w/a history of secrets#big indie movie#queer#william burroughs#william lee#daniel craig#allerton#drew starkey#foxsoulcourt fires up her interview watching engine

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

E. GREENAWAY | WILLIAM LEE [ONE-SHOT]

character(s): elle greenaway, mentioned william lee, mentioned spencer reid

tags: episode: s0205 aftermath (criminal minds), character study, this is what rewatching criminal minds does to me, ptsd, implied past rape

summary: too bad she was a better killer than she was a profiler.

elle remembers a gunshot.

she'd gone in blindly, thinking of RULES and fingers and blood. there was no way what had happened could've been prevented, she knew this as well as any fact. she was already unraveling - it had only been a matter of time.

i want you to think about this job, what you've been through, what you're capable of, hotch had said.

he had had no idea just what, exactly, that implied.

she didn't regret it, when she'd pulled the trigger. didn't regret it later, didn't regret the aftermath.

the only thing she could truly say she regretted was not saying goodbye to spencer. she thought he understood, in a way. there was a certain sort of sadness, with him, and she thought she was the same way. like they could both turn into the people they hunt, given time.

too bad she was a better killer than she was a profiler.

there was always a recurring dream. it got really bad about a week after the accident, and then went away for a while, just to come back, in intervals.

an empty corridor where a little girl sits. she's playing jack, by herself, and all the lights are off and the only reason elle can see is because of a red light that sits on the roof, pulsing to the beat of her heart. RULES is written on the wall, blood still dripping.

the little girl looks up and tilts her head to the side, and then, all of a sudden, she isn't a little girl in anymore; she's a monster. she's twice the size she was and her hands are covered in blood and her mishappen legs are bruised and cut. her arms are bent unnaturally and when looks at her, she snarls.

if elle cared, she'd say there was a metaphor in all that. like her subconscious was trying to tell her something, like naybe she was girl turned monster. of she cared.

too bad she doesn't.

there are things nobody knows about her. seeing her mother's dead, crushed body, under the weight of three cars, for example, or seeing her father's closed eyes in a coffin through blurry vision, imagining them open, lifeless and dead. going to college in her home state, going to a party thinking it'd be good for her to get out and socialize.

some cases hit close to home, everyone who's every worked in the bau knows that, but william lee had dug up memories she'd left behind long ago, reminded her of more than just a gunshot and blood.

not everybody can handle this job.

maybe, if elle had been better. if she'd been good. if she hadn't seen too much at a young age and clutched it so close to her chest, it hurt. if william lee had never been there to hand her a shovel and urge her to dig her own grave.

ironic.

when elle left, she never intended to come back, even if she could. maybe she'll travel the world, if she survives. maybe she'll have a mundane life where she meets a man she doesn't truly love or a woman who only fulfills the serial aspect in her life. maybe she'll learn to love and to grow and to make herself better.

but she probably won't survive.

she wonders if anyone will remember her. obviously, the agents who live will - another thing she wonders is how many of them will still be there by the end. she's willing to be two, at most; spencer and someone, she's sure. - maybe they'll even tell her story, but. she wants more than that, if she's being honest.

she just doesn't know what more implies.

#criminal minds#elle greenaway#spencer reid#william lee#criminal minds: writing#derek morgan#aaron hotchner#emily prentiss#jason gideon#david rossi#aaron hotch hotchner#jennifer jareau

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

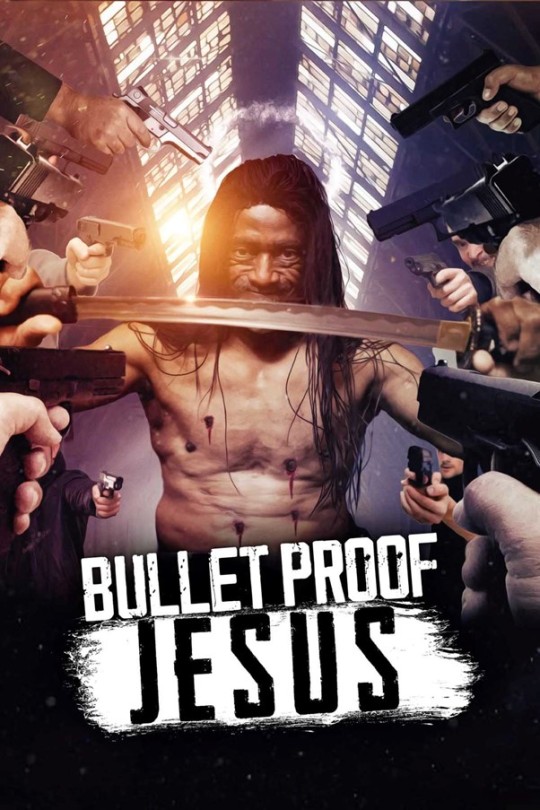

Bullet Proof Jesus (Director’s Cut) arrives this March

BayView Entertainment have released the action horror Bullet Proof Jesus (Director’s Cut), which is now available to rent/buy on Amazon Prime Video in the UK and USA.

Bullet Proof Jesus (Director’s Cut)will arrive on AVOD Digital Platforms worldwide on 30th March 2024 and is available to pre-order on Blu-ray (Region Free) in the USA ahead of its 27th February 2024 release.

Jesus must lead the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The “Abbott Elementary” Cast Answers Burning Questions | IMDb

#abbott elementary#dailyabbottelementary#abbottelementaryedit#percy jackson#sheryl lee ralph#tyler james williams#byaurore#userallisyn#nessa007#userbbelcher#usersugar#userhugh#tuserlou#usersavana#userlolo#usermorgan#usergiu#usersaoirse#userzo#usereena#i'm sorry this is killing me 😭

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Aabria: lair action

Jasper: oh, it's okay

Aabria: huh?

Jasper: it's okay, you don't have to do that

Aabria: I don't have to?

[Brennan laughing]

Izzy: we're good

Siobhan: no, thank you

Aabria: that threw me off so fucking much.

Brennan: the authority of, I was like, like that, whatever that was made me be like [imitating a ear piece call]: Aabria, Jasper says no on that

Aabria: yeah yeah, oh I'm so, can you tell him I'm so sorry--

Erika: it's the accent

Aabria: yeah, fucking British accent cinders authority

Jasper: came from such a deep sense of fear. That was where I was coming from

Siobhan! Yes, exactly, the accent. It comes from a deep sense of fear

Brennan: I've never seen someone who's being faced with death and ruin with a voice of like [calmly]: I'm gonna send this back to the kitchen because this was not very good

#aabria iyengar#dimension 20#burrow's end#ep 10 evolution and revolution#brennan lee mulligan#siobhan thompson#rashawn scott#jasper william cartwright#erika ishii#isabella roland#phoebe's aim of irradiating the earth. yikes!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

#jasper william cartwright#brennnan lee mulligan#aabriya iyengar#d20edit#dimension 20#dimension20edit#mygifs#adventuring party#d20 spoilers#burrows end#burrows end spoilers#dfjskfh nothing more terrifying actually#burrowsendedit#d20

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Like i promised

William Lee ( Moona and Barnaby ) profil with @amoexii template

Also Liam Whitlock-Kim ( @chirithy564 oc ) best friend

I really love my monkey boy 😍❤️😊 look how cute he si with Magical creatures

#harry potter magic awakened#hogwarts#hpoc#harry potter oc#harry potter#magic awakened#hpma oc#harry potter magic awakened oc#magic awakened mc#hp magic awakened#William lee#oc#niffler

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

n a k e d l u n c h, 1991 🎬 dir. david cronenberg 'Tom and Joan Frost'

#film#naked lunch#naked lunch 1991#david cronenberg#peter weller#judy davis#ian holm#william lee#joan frost#Tom Frost#Tom and Joan Frost

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endless Burrow's End

#siobhan thompson#brennan lee mulligan#aabria iyengar#Jasper William Cartwright#erika ishii#dropoutedit#dimension20edit#d20edit#burrow’s end#burrowsendedit#myedit#dimension 20#d20#d20 spoilers#burrow’s end spoilers#dropout#endless burrow’s end

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

*Tylers reaction sums it up

#im tyler#his reaction sums it up#emmys#so proud of her#her speech was chefs kiss also#abbott elementary#quinta brunson#tyler james williams#sheryl lee ralph#her kids#barbara howard#gregory eddie#janine teagues#gifs#gifset#gif

23K notes

·

View notes